Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 84

October 8, 2024

Having the Last Word

IT WAS 1982 OR thereabouts. After attempting to be a landlord for several years, I decided it wasn’t for me. I sold the house and the four-family apartment building I’d been managing.

The final task in closing out this adventure would come at tax time. Keeping the books was the one aspect of being a landlord that I didn’t mind. I understood how accumulated appreciation would be recaptured and how capital gains tax would affect that year’s taxes.

Off to Sam the CPA I went, with my carefully prepared handwritten ledger of debits and credits. After a few anxious weeks, I finally received a call from Nancy, Sam’s administrative person. Great. My taxes were finished and ready for pick up.

Whoa, my balance due was $1,000 more than I’d calculated. In 1982, that was a formidable amount of money. As I reviewed the return, however, I realized Sam had made an error. My crude number-crunching turned out to be correct. This was the moment I learned an inconvenient truth about the tax prep business.

Most CPAs are up to their eyebrows in tax returns more complex than the Form 1040. The preparation of simple individual tax returns is often completed by an assistant or less experienced seasonal worker, whose work often isn’t even reviewed by the CPA.

What the heck? I was paying for Sam the CPA to do my taxes, not his secretary. That’s when I decided that I didn’t have to pay someone to screw up my taxes when I could mess them up myself for free. Twenty years later, Dan’s Tax Prep was born. But that’s not what I’m here to talk about today.

We last updated our wills seven years ago, after Chris and I got married. Marriage introduced new complexity to our estate plan, especially regarding beneficiaries. The attorney we hired interviewed us to understand our intentions and to offer suggestions.

One of our ideas was to file a transfer-on-death affidavit with the county to keep the house out of the probate court. Our attorney thought that naming two unrelated families—mine and Chris’s—on the affidavit could lead to differences of opinion when the time came to sell the house.

On the one hand, that made sense to us. On the other hand, it went against our desire to avoid probate. Still, we decided to take the counselor’s advice and not file the affidavit.

When we received a draft of our new wills for review, they were riddled with typographical errors affecting our names, address and other contact information. The meat of the wills was fine, which led me to a couple of conclusions.

First, a careless employee using a boilerplate software program prepared the documents. Second, it was never reviewed by the attorney. Sound familiar?

We recently moved into a new home. I brought up the idea of revisiting the transfer-on-death affidavit. Chris suggested that we file the affidavit naming only my daughters as the beneficiaries, thus avoiding the problem of unrelated parties fighting over the house’s sale.

Keeping in mind the lackluster job done by the attorney seven years earlier, and the fact that I’m pretty darned good at filling out forms, I researched the process involved with filing an affidavit. It didn’t look difficult. I purchased WillMaker software, which includes the transfer-on-death real estate affidavit tailored to Ohio.

I simply followed the prompts in the program. I had to make a trip to the county recorder to obtain a copy of my deed, along with a reference to the prior deed on the property. With the finished affidavit in hand, I made another trip to the county where it was reviewed and filed.

Now, all of our financial accounts and the house will pass to our beneficiaries via payable-on-death or transfer-on-death affidavits. All that’s really disposed of by our wills is the stuff inside our home. I suspect some of our stuff will be taken by the kids and some donated to those in need. I have every reason to believe that this will be accomplished without conflict and without the need to involve the probate court.

With the filing of the affidavit, however, the house will not pass via our wills. This means that our wills need to be updated again. Since there’s not much in the wills, I’m taking a stab at them as well.

I’m using the WillMaker program to complete our updated wills. I carefully compared the new wills with the old ones, and found all of the elements of each to be in agreement. The software allowed us to divide the property into unequal shares, to name each grandkid in case their mother has passed, and to name a custodian for any minor children.

In addition to documents like health care directives and powers of attorney, the software also has a template for letters to survivors. I’m enjoying writing mine. My hope is to leave ‘em laughing.

I probably wouldn’t have attempted this project if the software didn’t come with a money-back guarantee, but it seems to work well. I do have the added advantage of having a son-in-law who worked as an estate attorney in Ohio before taking a job with his alma mater in Indiana. He’ll grade my homework.

How did the review by my son-in-law work out? He caught a glaring error that could have affected my well-laid plans. When my oldest daughter married 22 years ago, she kept the name Smith. After 22 years, and with everyone referring to her by her husband’s surname, that little factoid was so far back in my mind that I never thought about it.

I've corrected our wills. I'll also need to fix the error on our account beneficiary designations, as well as the real-estate affidavit I filed with the county. Everything else was in order. But it illustrates the importance of having a professional examine your will and similar documents.

For 30 years, Dan Smith was a driver-salesman and local union representative, before building a successful income-tax practice in Toledo, Ohio. He retired in 2022. Dan has two beautiful daughters, two loving sons-in-law and seven grandchildren. He and Chris, the love of his life, have been together for two great decades and counting. Check out Dan's earlier articles.

For 30 years, Dan Smith was a driver-salesman and local union representative, before building a successful income-tax practice in Toledo, Ohio. He retired in 2022. Dan has two beautiful daughters, two loving sons-in-law and seven grandchildren. He and Chris, the love of his life, have been together for two great decades and counting. Check out Dan's earlier articles.

The post Having the Last Word appeared first on HumbleDollar.

In Love With Bonds

WHEN I WAS GROWING up, I’d receive Series E savings bonds as birthday gifts from my parents. It was the start of many to come. My parents had great respect for savings bonds and, as I got older, I came to hold them in high regard as well.

Savings bonds never offered the highest interest rate. At a defense plant where I worked, a guy in the accounting department questioned my bond buying. He noted that savings bonds paid less interest than the certificates of deposit then available. I just shrugged my shoulders.

I know why I kept buying the bonds. They were something I was familiar with since childhood, plus it was an easy way to invest. When I began working full-time, I purchased savings bonds through payroll deduction. The deductions were automatic, so the money was gone before I could spend it.

In 1976, when I got married for the first time, the guests—who were our college friends—all gave us savings bonds. When I signed up for the U.S. Coast Guard’s Officer Candidate School in 1978, we were able to buy bonds through payroll deduction. I did.

When my current wife and I got married in 1987, once again our friends gave us savings bonds. And I continued buying them through payroll deduction for many more years. That ended when my employer introduced a 401(k) savings plan, and I switched my payroll deductions to buying mutual funds through the 401(k) instead.

But I held onto the savings bonds I’d acquired. They continued to earn interest for 30 years, and I typically only cashed them in when they matured.

On top of that, my mother kept buying savings bonds for my brother and me, as well as for her grandkids and great-grandkids. When my mother gave me all of my bonds, I stored them in a safe-deposit box at the bank until they matured.

In 2004, I converted some of my Series E bonds to HH bonds. These had a maturity of only 20 years, but—if you converted—it postponed the tax bill on matured Series E bonds for those two decades. HH bonds paid 1.5% in annual interest for 20 years. Coming into 2024, I still owned those HH bonds, which all finally mature this year.

When Series I bonds were introduced, I was hesitant. I was used to earning a fixed rate on my savings bonds. I bonds were different, offering a fixed rate and a variable rate. The variable rate reflects inflation, while the fixed rate represents the gain over and above inflation. I purchased Series I bonds rather than EE bonds when the fixed rate on I bonds was at least 1%.

My love affair with savings bonds has mostly come to a close. Buying a financial instrument with a 30-year maturity seems silly at my age.

Still, I continue to own many savings bonds. I hold them as dry powder should I ever need money. They’ve never been the vehicle that more sophisticated investors use. Yet, when banks were paying close to 0% interest after 2008’s Great Financial Crisis, my Series E bonds were still paying 4%. It made me feel good that this stodgy relic from the past was outshining other savings options.

The post In Love With Bonds appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 6, 2024

Underwater Overseas

IS IT WORTH OWNING international stocks? There’s far from universal agreement. The traditional argument for investing outside the U.S. is straightforward: diversification—since domestic and international stocks don’t move in lockstep, and sometimes diverge significantly.

At the same time, however, international stocks have lagged behind their U.S. counterparts for so many years that it’s been trying the patience of even the most tenacious investors. Domestic stocks have outpaced international stocks in eight of the past 10 years. On average, over that period, the U.S. market has returned 12.3% a year, while the most commonly referenced index of international stocks has delivered 4.6% annually. On a cumulative basis, domestic stocks have more than tripled, gaining a cumulative 219%, while international stocks have gained just 57%.

That’s enough to make any reasonable person question the value of investing outside the U.S. Though the long-term data indicate a benefit to diversifying, we need to be cautious in using the past as a guide to the future. The economist John Maynard Keynes commented that, “In the long run, we are all dead.”

So why, in the face of recent data, would anyone stick with international stocks? Below are five reasons I still recommend international holdings.

1. Performance. Despite Keynes’s quip about the long run, the reality is that you don’t have to go back too far to find periods when international stocks were doing quite well. Most notably, in the years after the dot-com market crash in 2000, international stocks held up much better. If you’d been in retirement at the time and relying on your portfolio for monthly withdrawals, that would have been a great benefit.

One challenge in assessing international stocks—which contributes to the debate around them—is that historical data on markets outside the U.S. is limited. Reliable figures on U.S. shares go back to 1926. But data on international markets go back, in most cases, no more than 50 years. But in the data we have, there’s a clear pattern of U.S. and international stocks taking turns as the better performer. On a chart, their relative results look a bit like a sine wave, oscillating back and forth. International stocks saw periods of outperformance in the mid-1970s, the mid-80s and the mid-90s.

2. Valuation. While valuation metrics such as price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios aren’t entirely predictive of future returns, there’s something of a relationship. When markets are expensive, future returns tend to be lower. Owing to years of relative underperformance, that’s now an argument in favor of international markets.

The P/E of the S&P 500 today is 21, while the comparable figure for the EAFE (Europe, Australasia and Far East) index of developed international markets stands at just 14. Emerging markets are even cheaper, at 12. Some are quick to point out that domestic stocks deserve higher valuations, owing to the preponderance of fast-growing technology companies here. I agree with that. Nonetheless, the valuation gap between U.S. and international stocks has grown. Thus, international markets, on a relative basis, are historically cheap. That may present an opportunity.

3. Exposure to value. What’s been driving the U.S. market higher in recent years? For the most part, it’s the handful of technology stocks now known as the Magnificent Seven: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla. Together with one more—Broadcom—technology stocks hold eight of the top 10 slots in the S&P 500, accounting for more than 30% of the total value of the index.

By contrast, what are the largest companies outside the U.S.? Only half are technology companies. The other five of the top 10 international stocks include four pharmaceutical companies and a food manufacturer.

Through one lens, you might view this as a strength of the U.S. market and a point of weakness for markets outside the U.S. But as I noted a few weeks back, growth stocks like the Magnificent Seven don’t always outperform. Value stocks, on the other hand, are distinctly less exciting, but they’ve demonstrated stronger performance than their staid appearance might lead investors to believe. And since value stocks like food and pharmaceutical companies dominate international markets, that gives international stocks a value tilt.

For that reason, adding international stocks to a portfolio can help better balance the mix between growth and value. To be sure, growth stocks like the Magnificent Seven have delivered impressive performance in recent years. But as the standard investment disclaimer states, past performance does not guarantee future results.

4. Defense. As I noted earlier, the top stocks in the S&P 500 account for a disproportionate share of the overall index. The top 10 total more than 35%. When these stocks are doing well, that’s a benefit. But should one of them run into trouble, the top-heavy nature of the U.S. market presents a risk.

By contrast, when you invest outside the U.S., concentration is less of a concern. That’s for two reasons. First, most international markets don’t have any companies on the same enormous scale as the largest firms in the U.S. Second, because most international indexes contain stocks from multiple markets, that helps to limit the weighting of any one company. In a total international markets fund, for example, the top 10 stocks account for just 10% of the total.

5. Currency diversification. International stocks can help diversify a portfolio along another dimension: currency. I wouldn’t recommend buying currencies as a standalone investment, because of their volatility and lack of intrinsic value. But as an added benefit of owning international stocks, currency diversification can provide an additional, potentially helpful source of diversification.

If you want to include international stocks, what’s the right percentage? As I often do, I recommend a “center lane” approach. Today, international markets account for about 40% of the global stock market’s total value. But there’s no rule that says your portfolio must also hold 40%. Personally, I recommend 20%. Why? For starters, if you live in the U.S. and your bills are in dollars, that’s a good reason to hold most of your investments in dollars.

Indeed, there are reasons you might tilt your portfolio toward the U.S. market even if you live outside the U.S. Jack Bogle, the late founder of Vanguard Group, held 100% of his personal portfolio in domestic stocks. Among the reasons he cited: The U.S. has “the most innovative economy, the most productive economy, the most technologically advanced economy and the most diverse economy.”

It’s an important point. While other countries have produced successful companies, the U.S. is unique in the number and size of the companies it’s produced. For that reason, I wouldn’t hesitate to hold the lion’s share of your portfolio in domestic stocks—but there are also good reasons to look beyond our borders.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Underwater Overseas appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 4, 2024

Turned Upside Down

FOUR MONTHS AGO, I was told I might have just a year to live. It’s been a whirlwind ever since.

I’ve been inundated with messages from acquaintances and readers, gone to countless medical appointments, my diagnosis has received a surprising amount of media attention, I’ve been hustling to organize my financial affairs, and Elaine and I have taken two trips.

Where do things stand today? Here’s what’s been going on.

Medical update. After three radiation treatments to zap the 10 cancerous lesions on my brain and an intense opening round of infusion sessions, I’ve now settled into an every-three-week chemotherapy and immunotherapy program.

I typically feel a little rough for the four or five days after each chemo session, and then things improve. There’s a fairly predictable series of side-effects, including insomnia, nausea, constipation, acne, cracking of the skin on my fingertips, hair thinning, mouth sores and feet swelling. I find the side-effects are eased by exercising every day and downing countless glasses of water, though—thanks to all that water—it also means I regularly feel like a four-year-old who suddenly screams, “I got to go.”

Is the treatment working? So far, so good. Two months ago, a brain MRI and abdomen scan showed the cancer has, for now, stopped spreading. I’m slated for another abdomen scan on Monday, and another brain MRI in early November. This happy state of affairs will eventually end, and I’ll need another treatment plan if I’m to keep my cancer at bay. Still, it seems I’ll get more than the year that was initially predicted.

Health insurance. In late May, over a 14-hour stretch starting Sunday lunchtime, I went from a local hospital system’s urgent care clinic to its emergency room to the intensive care unit. What was all this costing? Would my insurance cover it? I believe we should all strive to be smart consumers of medical services. But the truth is, these are not questions I could have got answered at the time, even if I’d thought to ask them.

Indeed, when I did start asking about insurance coverage, nobody seemed to know. Instead, I fell back on the assumption that my costs would likely be capped by my policy’s $5,800 annual out-of-pocket maximum. But I wasn’t 100% sure.

What if my hospitalization, along with the various tests and procedures, needed insurance pre-approval? What if one of the doctors who treated me was out of network? As it happens, all has been fine.

Still, I look at the insurance company’s explanations of benefits (EOB) and shake my head. For instance, there’s the 26-page EOB statement from June 12 for a $80,513.60 hospital bill. My health insurer deemed $15,024.65 to be allowable, with $2,552.63 owed by me and $12,472.02 paid by the insurer. Was I charged the right amount? Count me among the clueless.

Clearing out. I’ve been slowly working through a handful of boxes housing old tax returns, letters, financial statements, photos, mementos and more.

Along the way, I’ve tossed a bunch of letters from when I was in college. Glancing through those letters, I’m not sure I would have liked my 19-year-old self. I come across as self-absorbed and pretentious, and I’m glad my kids will no longer get the chance to see that side of my younger self. Want to present a carefully curated version of who you were to future generations? Maybe it’s time to clean out the basement.

In sorting through all this stuff, I have two guiding assumptions. First, if I leave behind too many personal papers, there's a risk my family will give them a quick glance and then trash the lot. This is a case where less is more.

Second, if I don’t throw out unneeded financial documents, my family will assume they’re important. Ditto for personal possessions. If I don’t toss the stuff I don’t care about, there’s a risk my family will imagine these items had some value to me, sentimental or otherwise. Again, less is most definitely more.

As I plow through the boxes, I’ve been making snap decisions, but I doubt I’m being too hasty. Between 2011 and 2020, I moved four times. Each time, I shed a fair number of possessions. The good news: There’s nothing I’ve regretted throwing out, and I'm confident that’ll also be true this time around.

Tripping. Last year, before my diagnosis, Elaine and I started compiling a travel wish list—the Shetland Islands, an Alaska cruise, the Amalfi Coast, the Galapagos Islands, that sort of thing. All this daydreaming went out the window with my diagnosis.

What trips could we realistically take in the time I have remaining—trips that, ideally, wouldn’t be too taxing and, if necessary, could be cancelled at short notice? Before my diagnosis, we had three vacations booked. But none fit with my chemo schedule, plus I was concerned not to spend more than a week at a time away from home and hence away from my doctors.

The upshot: So far, Elaine and I have taken a weeklong trip to Ireland that had previously been scheduled for 12 days, and had a long weekend away with my two children and their families. We’re about to fly to Paris. We’ve also changed the dates for a previously scheduled London trip, swapped from an 11-day Caribbean cruise to a shorter one, and started making arrangements for a second trip to Ireland. There are more trips I’d like to take, including visiting my beloved Hope Cove, but that hinges on my health.

Two minds. When I first heard my diagnosis, I quickly made peace with my fate. It may not have been what I wanted, but it came with certainty—and we humans like certainty.

Today, I find myself more torn. On the one hand, I know the next brain MRI, or body scan, or blood test may show I’m starting to lose my battle with cancer. On the other hand, there’s a good chance I’ll be healthy enough to travel through at least late spring 2025, and I’m excited about the trips we’re planning. That excitement is putting a dent in my stoicism. Should I accept the finality of my diagnosis or allow myself to dream about a future that likely won't happen? I find I’m struggling to do both.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post Turned Upside Down appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 3, 2024

Misplaced Trust

WHEN I WAS A YOUNG adult, my parents sat me down and explained that I might at some point inherit money from my grandfather’s trust, which had also helped put me through college. My grandfather passed away in 1984, and his wife—my father’s stepmother—became the trust’s beneficiary.

My father was an only child. The trust stipulated that, if his stepmother died before him, he would receive two-thirds of the trust, while my two siblings and I would share the other third. But my father died relatively young, predeceasing his stepmother. This meant that, when my father’s stepmother—my step-grandmother—died, my siblings and I would each receive a third of the trust, instead of the one-ninth we would have gotten if my father had still been alive.

My step-grandmother passed in January 2005, and we began receiving information from the bank that was administering the trust. Our individual portions were delivered in cash, stocks and bonds, which were transferred into my Charles Schwab account. In addition, we each inherited shares in a golf course in Canton, Ohio. It wasn’t so much money that we could quit our jobs, but enough that it could make some things easier.

At the time we received this windfall, I was age 44. I was married with two daughters, then 16 and 11. My husband and I were gainfully employed. He was an attorney for a state agency, while I was a university professor. We made enough money to live comfortably but not lavishly in Northern California, but we had little money saved for retirement or for our kids’ college. Neither of us, though we were well-educated professionals, knew much about managing money.

Doug Texter wrote last year about the purposeful way he handled a family inheritance. Unlike Doug, when we got the inheritance, we weren’t prepared to deal with it wisely. Though we did a few things well, we made some mistakes, too.

No regrets. Our older daughter was a junior in high school when we received the inheritance. She was a brilliant student, and it was great to tell her that she could apply to whatever schools she aspired to and not worry about the cost.

As it turned out, she ended up going to the University of California at Berkeley, not a private school, but it still wasn’t cheap. Even in 2006, when she started college, we were probably spending $25,000 a year on tuition, room, board and other expenses. But we have no regrets about allowing her to pursue her degree without taking on debt.

We also took a couple of great trips in 2008—a first vacation to Europe for my husband and me to celebrate our 25th anniversary, and a family trip to New Zealand when I was invited to speak at a couple of academic conferences in Auckland. Though I leveraged points and miles for the Europe trip and got some of my expenses paid for the Auckland trip, being able to supplement those sources with my inheritance allowed us to make some special memories.

One of the first things we did when we got the trust money was to buy our older daughter a car, for which we paid cash. While buying new cars isn’t always a great financial decision, in this case it turned out well: Today, she’s still driving that 2005 Mazda3 hatchback. When our younger daughter turned 16 in 2010, we bought her a car, as well. We also made some needed updates to our home, investments that paid off years later when we sold that home at a substantial profit.

Finally, because we had extra money to backfill our household budget, my husband and I began fully funding our retirement accounts every year. At that point, as state employees, we both had access to 403(b) and 457 accounts. Being able to max out those retirement vehicles saved us a lot in income taxes, and it was great to jumpstart our retirement savings.

Wish I had a mulligan. Because of my ignorance, I wasn’t smart when tapping the trust for money. I didn’t like dealing with all the individual stocks and the bond funds, so I rolled everything into Vanguard Group’s low-fee mutual funds. I’d started reading Money magazine, so at least I knew to do that much.

But I didn’t look to minimize taxes when selling the stocks. To this day, I still don’t know whether it was a dumb idea to divest myself of those stocks, some of which were blue chips. Then, when the 2008-09 recession hit, I was selling the mutual funds at greatly reduced values to pay college bills and fund our retirement accounts. I’m certain I didn’t handle any of this very well.

The other dumb thing I did was to sell the golf course shares. I didn’t like owning them. I had to pay taxes on them every year, and they added cumbersome paperwork. When our younger daughter started college, I felt I needed more cash, so I arranged to sell the shares. My brother had sold his shares right away, too, and we both lived to regret it. I got about $40,000 for the shares, money which was helpful in the moment. But a few years later, the golf course was sold to a developer. My sister, who had held onto her shares, got about $200,000 for her stake.

If I had it to do over, the first thing I’d do is march into a financial planner’s office and get advice about how to handle the windfall. I’m certain I could have been much smarter about the whole thing. I’m kind of embarrassed when I think about it now.

Dana Ferris and her husband live in Davis, California. She’s a professor in the writing program at the University of California, Davis, and is the author or co-author of

nine books

on teaching writing and reading to second language learners. Dana is a huge baseball fan and writes a

weekly column

for a San Francisco Giants fan blog under the nom de plume DrLefty. When not working, she also loves cooking, traveling and working out. Follow Dana on X @LeftyDana and on Threads, and check out her earlier articles.

Dana Ferris and her husband live in Davis, California. She’s a professor in the writing program at the University of California, Davis, and is the author or co-author of

nine books

on teaching writing and reading to second language learners. Dana is a huge baseball fan and writes a

weekly column

for a San Francisco Giants fan blog under the nom de plume DrLefty. When not working, she also loves cooking, traveling and working out. Follow Dana on X @LeftyDana and on Threads, and check out her earlier articles.The post Misplaced Trust appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 2, 2024

Luxury on Rails

I LOVE TO TRAVEL—and it runs in the family. My parents were avid travelers, with my father receiving a generous travel allowance from his work every four years.

In addition, my father always managed his time and budget for numerous other trips. After his passing, my brother and I took turns maintaining the travel tradition with our mom, until plans were disrupted by the pandemic.

After retiring this year, I eagerly anticipated visiting my mother in India and taking her on a grand tour. I’d considered several options, ranging from an African safari to a leisurely tour of Vietnam. I called my mother to finalize our plans.

To my surprise, she wasn’t as enthusiastic as I’d hoped. In her late 70s, she was uncertain about traveling overseas because of her chronic back pain and lack of confidence in her strength. I was disappointed but didn’t give up. I continued searching for suitable options that might work for her.

I vaguely recalled hearing about luxurious train tours of India that were popular with foreign tourists. It dawned on me that, while my mother had been to most of India’s tourist spots, she might be interested in a fresh and unique experience. With renewed hope, I opened my laptop to research luxury train travel in India.

My search revealed several such trains that attract affluent retirees from around the world. These tours cater to people with mobility challenges, or to those who might feel uneasy traveling in India on their own.

Just like a small-group luxury cruise, these trains provide a hassle-free, all-inclusive experience with a focus on safety, care and comfort. A common theme across these different trains was a hefty price tag, quite steep by Indian standards.

My mother was intrigued and seemed open to the idea, particularly because she loved traveling by train. Adding to the allure, my aunt—who I’ve written about in a previous article—was able to join us. Without further hesitation, I made a reservation before they could change their minds.

A train named Deccan Odyssey looked promising, but I struggled to find reliable contact information due to changes in ownership after the pandemic. I took a chance and reached out to the most intuitively named website. It turned out to be one of the tour’s few authorized agents.

Soon, a real person contacted me with a price quote. Since we were three passengers, I opted for the pricier suite, rather than a regular cabin for two. The cost—even with a low-season discount—was steep enough to give me pause, but I overcame my reluctance, figuring that money is only valuable when used to fulfill deeply personal goals, such as sharing a once-in-a-lifetime experience with people closest to my heart.

Everything was arranged in time and, on a pleasant March afternoon, we departed from Kolkata and headed to New Delhi, the starting point of our tour. Sadly, the train tour itself got off to a rough start.

We arrived at the designated train station in New Delhi at 5 p.m. as instructed, only to find that the train was delayed due to an emergency. The company tried to make the wait more bearable by providing refreshments and live entertainment to the passengers.

The train eventually arrived after 10 p.m., and the staff promptly assisted all passengers with boarding. Inside, the train was absolutely stunning, like a miniature five-star hotel on wheels. A personal butler and an attendant guided us to our suite and gave us an overview of the amenities.

Our suite featured a bedroom with a twin bed, another room with a sofa bed and writing desk, and two ensuite bathrooms with showers. The rooms had panoramic windows, blackout curtains, beautiful decor and fresh flowers. It was beyond anything we’d imagined.

It was time for dinner, so we headed to the onboard restaurant through a series of plush, carpeted corridors and elegantly decorated coaches. The restaurant’s impeccable service and gourmet menu could rival any fine-dining experience in an upscale hotel.

We enjoyed our sumptuous dinner and headed back to our suite. The tour manager soon came by to introduce herself and offer another sincere apology for the unexpected delay. “We’ll make up for the inconvenience,” she said.

We all slept soundly that night, thanks not only to the long and tiring wait, but also to the soothing, rhythmic motion of the train. The next morning, as we gazed at the tranquil landscape outside our windows, someone knocked at the door. It was our butler with morning tea and the attendant to make our beds.

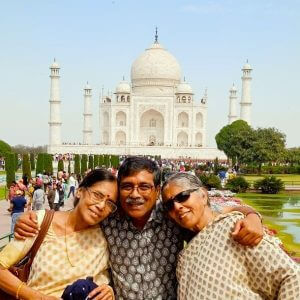

We reached Agra, the city of the Taj. Stepping off the train onto the carpeted platform reserved for us, we were greeted with fresh garlands and a tilaka on our foreheads. A small troupe of artists danced to the folk tunes of the shehnai and dhol, transforming the platform into a ceremonial stage.

Our private guide led us to our SUV for the daylong city tour. Our first destination was the Taj Mahal. Although my mother and aunt had seen it before, it was my first time visiting. The site was very crowded. Only after we got inside could I see why it’s called one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Our private guide led us to our SUV for the daylong city tour. Our first destination was the Taj Mahal. Although my mother and aunt had seen it before, it was my first time visiting. The site was very crowded. Only after we got inside could I see why it’s called one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

We had a fabulous lunch at a posh restaurant. My mother, feeling a bit worn out, suggested that we stick to the less strenuous sights in the afternoon. After our sightseeing, the car dropped us at the train station entrance, where our butler and a security guard were waiting to walk us back to the train. The dinner that evening featured local specialties.

The next day, we reached Sawai Madhopur, the gateway to the Ranthambore National Park. At the station, we experienced another welcoming ceremony, this time reflecting the culture of the state of Rajasthan. We then boarded a safari vehicle and entered the tiger reserve, where we saw an abundance of birds and animals. We were also fortunate to spot a tiger up close, though only for a short while.

The next few days flew by as we traveled across four states in a week. Each morning, we arrived at a new place, relished the grand reception and set out for our excursions. We toured the Pink City of Jaipur and drove up to the Amer Fort, marveled at the exquisite crystal collections at the City Palace of Udaipur, and enjoyed a vibrant cultural performance inside the majestic Laxmi Vilas Palace of Vadodara.

Our next destination was to visit the Ellora Caves near the city of Aurangabad. Despite the scorching sun, the wheelchair services allowed my mother and my aunt to comfortably admire the great Kailasa Temple, a remarkable monolithic rock-cut structure renowned for its intricate carvings and grand architecture.

Just as we were getting accustomed to its luxury and extravagance, our train reached its final destination of Mumbai, where another treat awaited me. Smith and Sabya, two dear friends who live in Mumbai, visited us at our hotel. We strolled down Marine Drive, savored street food, and laughed and chatted just like old times. That evening—and the entire train trip—has become one of my most treasured memories.

Sanjib Saha retired early from software engineering to dedicate more time to family and friends, pursue personal development and assist others as a money wellness mentor. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is the president and co-founder of Dollar Mentor, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization offering free investment and financial education. Follow his nonprofit on LinkedIn, and check out Sanjib's earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha retired early from software engineering to dedicate more time to family and friends, pursue personal development and assist others as a money wellness mentor. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is the president and co-founder of Dollar Mentor, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization offering free investment and financial education. Follow his nonprofit on LinkedIn, and check out Sanjib's earlier articles.The post Luxury on Rails appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 1, 2024

Don’t Build Without It

YEARS AGO, I SAW a Looney Tunes cartoon starring Daffy Duck and Elmer Fudd. As always, good old Elmer was trying to kill a duck for dinner, only to be outsmarted by the much cleverer Daffy.

In this particular episode, Daffy is playing a game of catch with his duck friends outside Elmer’s house. An overthrown ball crashes through a window. Elmer comes out and says, “Who broke that glass? Someone is going to pay for that.” The ducks all bump into each other in their efforts to run away.

Elmer gets outfoxed, of course, but you don’t have to be a patsy like him when it comes to home repairs or remodeling. Imagine you’ve hired a contractor to work on your house. What happens if the contractor breaks a window or, worse still, drops a load of roofing shingles onto your new car?

You may have done your due diligence in selecting a contractor by getting a recommendation from your neighbor, obtaining numerous quotes and reviewing the contractor’s Better Business Bureau ratings, so you might assume that your contractor will replace the broken glass or pay for your car’s bodywork.

But instead, you may get the runaround. Maybe the contractor is broke. He may keep making promises without undertaking the repairs. He might even abandon your job without warning.

To keep from getting fleeced, request a certificate of insurance from the contractor before he steps foot on your property. This one-page document typically tells you if the contractor or his subcontractor has three insurance policies in force: a general liability policy, a worker’s compensation policy and a commercial auto policy.

What do these three policies cover? First, the general liability policy will cover any damage the contractor does to your property, such as a broken window or dented car.

Second, the worker’s compensation policy covers his workers if they get injured on the job. Worker’s compensation is no-fault, meaning no matter how or why the worker was injured, the policy will pay the employee while he’s laid up.

Third, the commercial auto policy is similar to the general liability policy, except it covers injuries or damage caused by his vehicles on your property. Say a worker plows through your garage door. A commercial auto policy should cover your loss.

If the contractor can’t provide a certificate of insurance, be cautious. You might be working with a small-time operator who you know and trust—or someone who’s fly-by-night. It all might work out fine. But if it doesn’t, it’s potentially your loss.

While these three policies are essential safeguards, there are two more insurance coverages you might want for big projects. If you’re making major renovations to your house, you might confirm that the contractor has a builder’s risk policy in force.

A builder’s risk policy insures against damage to buildings that are under construction. It can cover losses caused by fire, hail, windstorms, vandalism or theft, among other perils. Coverage continues during construction and ends when the job is done.

If you have a very large project, you probably should ask for a contractor performance bond. This policy, which is secured by the contractor, would make you whole should the contractor not complete the work spelled out in your contract. The bond would pay you for the unfinished portion of the promised work if you’re named on the performance bond.

Surprises happen so often in construction that mishaps seem more like certainties. Insurance won’t solve the runaway problem of cost overruns. But it can help protect against damage to your home, your car, a worker’s health and your finances.

The Urge to Splurge

"MONEY PIT" USUALLY refers to an old home that needs constant repair. But the term can also apply to anything on which we spend endless money.

For instance, in my teenage years, I saw guys use every paycheck they got to buy something new for their car. It might be a new piece of chrome, a stylish set of wheels or a new stereo. It seemed like there was never an end to the spending. After a while, they’d enter their tricked-out cars in auto shows, where they’d be admired by other guys who also spent too much on their cars.

There are two types of people in this world: savers and spenders. You either find a reason not to spend money—which means you save it—or you find any reason in the world to spend it.

For many people, their home is the chief reason to spend. This is the classic money pit. They serially remodel the kitchen, bathrooms, basement and garage. Outside, they can always justify building an extension, a deck, a swimming pool, a cabana or even a new shed to store all the stuff they buy for home maintenance. The possibilities are endless.

Some improvements are justified, of course. If some house-related spending allows you to lead a better life, I’m all for it. Years ago, my wife’s family added an above-ground pool to their house on Long Island, New York. It gave her cousins from New York City a good reason to visit during the hot summer months. Their house became a gathering place for the extended family, and provided my wife with many happy childhood memories.

Run a business out of your house? Creating a home office is a worthwhile expense—but redecorating that office every year seems excessive. For the spenders of this world, though, such expenditures are easily justified.

What about the other person living in the house? Does he or she feel the money is well spent—or wasted? Could it have been better used for the kids' college education or to fatten the family’s retirement savings?

Money can be spent or saved. Spending all of it or, worse still, borrowing to spend, inevitably leads to money problems. My advice: Unless the money is being used for the betterment of all involved, try to steer clear of money pits of any kind.

David Gartland was born and raised on Long Island, New York, and has lived in central New Jersey since 1987. He earned a bachelor’s degree in math from the State University of New York at Cortland and holds various professional insurance designations. Dave’s property and casualty insurance career with different companies lasted 42 years. He’s been married 36 years, and has a son with special needs. Dave has identified three areas of interest that he focuses on to enjoy retirement: exploring, learning and accomplishing. Pursuing any one of these leads to contentment. Check out Dave's earlier articles.

David Gartland was born and raised on Long Island, New York, and has lived in central New Jersey since 1987. He earned a bachelor’s degree in math from the State University of New York at Cortland and holds various professional insurance designations. Dave’s property and casualty insurance career with different companies lasted 42 years. He’s been married 36 years, and has a son with special needs. Dave has identified three areas of interest that he focuses on to enjoy retirement: exploring, learning and accomplishing. Pursuing any one of these leads to contentment. Check out Dave's earlier articles.The post Don’t Build Without It appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 30, 2024

Ranking Colleges

I'VE TAUGHT BEHAVIORAL economics, which holds that even our most important decisions are influenced by unrecognized biases. For my students, there’s no better example than the choice of where they went to college.

Although the cost is enormous, the decision of where to go hinges on the smallest things. A teenager who says, “I want to be close to my boyfriend,” will zero in on a nearby college, even if her high school romance is fading. The opposite impulse—to go far away—led my brother from New Jersey to attend college in Los Angeles.

After my children toured colleges, we didn’t hear anything about the number of students who go on to get graduate degrees or the percentage of students who graduate in four years. Instead, we heard about the elegant ballet flats the tour guide had worn, or how cool it would be to attend a city school.

When faced with a difficult decision, people tend to ask themselves an easier question and answer that one instead. We usually don’t notice this substitution and later tell ourselves that we considered our options carefully.

Because America is full of great colleges, little harm is done by such decision-making shortcuts—until the bill comes due. Those who borrowed to attend their dream school can find themselves drowning in debt, unable to pay both their student loans and their rent.

When I enrolled at the University of Rochester in 1974, it cost $4,000 a year. Tuition, room and board now exceed $80,000. Wages have risen at a far slower pace than the 20-fold increase in college costs. Many students realize too late that the central question at the heart of their college decision is, “Can I afford this given the salary I’ll earn afterward?”

That’s a hard question to answer, especially for 18-year-olds. That’s why parents of college-bound seniors may want to consult The Wall Street Journal’s 2025 college rankings published this month. It gives extra weight to financial outcomes, particularly how much a school “boosts a student’s salary beyond what they would be expected to earn regardless of which college they attended.”

Viewed through this return-on-investment lens, some unfamiliar names rose to the top. Business- and technology-focused schools like Babson, Claremont McKenna, Georgia Institute of Technology and Davidson all broke into the top 10 colleges in the nation. Bentley University, Lehigh University, San Jose State and Virginia Tech landed in the top 20.

That’s quite different from the U.S. News & World Report rankings, issued this September for the 40th year. By now, many schools have gamed the U.S. News rating systems to raise their standing. No less of an authority than U.S. Education Secretary Miguel A. Cardona said, “It's time to stop worshiping at the false altar of U.S. News & World Report. It's time to focus on what truly matters: delivering value and upward mobility.”

The Journal seems to be trying to do that. Still, it’s wise to view any ranking system with skepticism. The Journal’s algorithm does produce some head-scratching results. The college where I taught, St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, is ranked No. 42 nationally, ahead of Duke (No. 45) and Dartmouth (No. 57). St. Joe’s may be benefitting from the extra credit given to schools that create upward social mobility, helping students to rise above where they started in life.

The Journal estimated that St. Joe’s added $51,405 per year to a typical graduate’s salary and cost $31,894 a year after scholarships and discounts. At this rate, St. Joe grads would need an average of just two years and five months to repay their student loans, according to the Journal, provided they used only the extra pay that their degree added to their wages.

Compare this to Savannah College of Art and Design, No. 431 in the Journal’s rankings. Savannah added $17,274 a year to the average graduate’s salary but cost $44,790 a year to attend. It would take Savannah grads 10 years and four months, on average, to pay off their student loans using only the extra pay conferred by their arts degree, according to the Journal’s calculation.

What should we make of the Journal’s ranking? Is St. Joe’s really a better school than Duke? Certainly not in basketball. The Journal’s system is still on its shakeout tour, I suspect. That said, a contrary view—even when flawed—can open the eyes of high school seniors to a wider array of colleges.

When making a difficult decision, behavioral economists advise us to place one hand on the data. Seeing how others have fared when making a similar choice can disrupt our tendency to make snap decisions.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman said data can provide us with “the outside view.” In this case, the outside view might disrupt the tendency to fall in love with a college based only on the campus tour. Kahneman called that kind of decision-making “the inside view,” and wrote that it’s based on WYSIATI—what you see is all there is.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.The post Ranking Colleges appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 29, 2024

Retiring Smarter

A RECENTLY RELEASED book titled How to Retire is a goldmine for those in or near retirement. For the book, Christine Benz—Morningstar’s director of personal finance and retirement planning—conducted interviews with 20 experts, covering every aspect of retirement.

The result is a valuable field guide for those tackling life after work. Below are seven insights I found particularly useful.

1. Social connections. When we think about retirement planning, most of us tend to think first about the numbers. “Do I have enough? Am I on track?” These are certainly important questions. But one of the book’s experts, Michael Finke, points out that they’re just part of the equation. Finke argues that it’s equally important to be investing in social connections during our working years. That’s because isolation—unfortunately—can be a reality for some retirees after leaving the workplace’s built-in social network.

Where retirees choose to live is also critical. Finke cites research that found that folks tend to be happier living in their own homes—but only for a time. “Once they hit their 80s,” he says, “people who live in apartments are actually happier.” Everyone is different, of course. The key lesson: Retirement planning requires more than just making the numbers work. We also need to plan how and where we’ll spend our time.

2. Retirement styles. I recall meeting with a couple who were on the cusp of retirement. When it came to the question of investment strategy, the husband was quick to respond: “Let’s go with 100% stocks.” They could afford the risk, he argued.

His wife countered that they should go with 100% bonds, reasoning that they didn’t need to take any risk. While they were able to find a middle ground, this highlighted a reality of retirement planning: There’s more than one right way to build a plan—and people differ on the best approach.

Some like managing their own portfolio and are comfortable with market risk. Others, meanwhile, would prefer the guaranteed income offered by an annuity and don’t mind the limitations they impose. To help retirees better understand their personal preferences, researcher Wade Pfau has developed an assessment he calls “Retirement Income Style Awareness.” The idea is to help couples like the one I described understand both the range of options, as well as their own preferences, before they set out to make a plan.

3. Safe withdrawals. You’ve most likely heard of the “4% rule.” Based on research by advisor William Bengen, this is a guideline for setting a sustainable withdrawal rate from a portfolio. It’s intended to minimize the chance a retiree would run out of money.

But researcher Jonathan Guyton notes that the 4% “rule” was never intended as a rule. Because it was designed to be a “set it and forget it” strategy, it’s overly conservative, he says. “It’s designed to work even if you get a worst-case scenario” in the market. But since worst-case scenarios occur only in a minority of time periods, most retirees should be able to spend more than 4%.

That’s why Guyton recommends an alternative to the static 4% approach. His “guardrails” strategy allows retirees to adjust their spending from year to year as the market rises and falls. The bottom line: The 4% rule can be useful for a back-of-the-envelope reading on retirement readiness, but it’s not a complete answer.

4. Believing the numbers. Author Morgan Housel has observed that compound interest—a powerful force in finance—doesn’t lend itself to easy computation. If you have to calculate, “eight plus eight plus eight plus eight,” Housel says, the math isn’t difficult. But if we had to compute “eight times eight times eight times eight,” he says, “your head's going to explode.” The math, in other words, isn’t intuitive.

This has always presented a challenge in financial planning, but author JL Collins provides a further insight. Compounding “is like a hockey stick,” he says. “It goes along slowly and then spikes.” That’s a good thing, of course, but it does present a pitfall. Collins describes a discussion with a woman who, like many people in recent years, had benefited from the market’s hockey-stick-like growth. She had a problem, though: Even though she could see the numbers, “she couldn’t quite believe them.”

It’s an interesting dynamic and fairly common. After decades of saving, plus strong market gains, many people have a hard time shifting gears from saving to spending. That’s why I recommend sketching out long-term projections that include various stress tests.

5. When to stop playing the game. William Bernstein, author of The Four Pillars of Investing, coined this well-known personal finance motto: “If you’ve won the game, quit playing.” If you’ve achieved financial independence, in other words, don’t unnecessarily jeopardize it. Instead, invest conservatively.

But Bernstein explains that this advice was intended only for “the median retiree.” Someone with more substantial savings can certainly take more risk. Folks with modest 2% or 3% withdrawal rates, he says, “are not drawing down enough of their assets to get into trouble.” It’s an important point. As a retiree’s asset base grows, the range of suitable asset allocation choices broadens. The advice to “quit playing” is important—but only in some cases.

6. Understanding history. A theme that runs through many of the interviews in this book is the importance of studying history. Bernstein, for example, explains why stocks tend to be a good hedge against inflation. He cites the Weimar Republic during the interwar era in Germany: “When prices increased there by a factor of one trillion, you actually were able to earn a positive real return.”

Elsewhere, Bernstein notes a little-discussed risk in owning an annuity: the risk that the insurer might fail. “I don’t think anyone should soft-pedal that,” he says, citing the 1991 failure of Executive Life Insurance as an example. It left policyholders with more than $4 billion in losses.

7. Setting an allocation. You may be familiar with the “bucket” approach to asset allocation. With this strategy, the size of a retiree’s bond portfolio is set in proportion to his or her withdrawal needs. Suppose a couple requires $100,000 per year from their portfolio. They might set aside $500,000 or $700,000 in bonds—enough to weather a five- or seven-year downturn in stocks. The remainder of the portfolio could then be invested in stocks, and the result would be a simple stock-and-bond portfolio.

But as Christine Benz points out, we shouldn’t overlook the value of cash. She recommends a separate cash bucket containing one or two years’ worth of expenses. Why hold cash, especially with rates falling? Benz points to 2022, when both stocks and bonds declined: “A retiree with cash on hand could have used those funds to provide spending money.” Holding cash, in other words, might feel inefficient, but it can serve an important role.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Retiring Smarter appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 27, 2024

My Spending Rules

HERE'S A FINANCIAL topic on which I claim scant expertise: spending. Still, I’ve belatedly been getting a lot of practice.

Over the past four years, I’ve spent more freely than at any time in my life. While part of it might be explained by post-pandemic splurging, mostly it’s because I finally convinced myself that I had more than enough saved for retirement. Added to that has been my recent cancer diagnosis, which has prompted Elaine and me to take our spending to a whole new level, as we attempt to cram a retirement’s worth of travel into the limited time I have left.

I can’t claim to be entirely comfortable with all of this. To counter my unease, I fall back on seven rules that—I hope—will make my spending less impulsive and more thoughtful.

1. The dollars that bring the greatest happiness are those we don’t spend. If we don’t have enough set aside in a bank or investment account to feel financially secure, we’ll suffer ongoing money stress, and the stuff we buy likely won’t come close to compensating. How much do we need to feel safe? The sum will differ for each of us. For me, today’s amount is considerably larger than it was when I was in my 20s and 30s, and more oblivious to risk.

2. Lower fixed costs mean fewer financial worries. Want to stress less about money? The two key steps, I believe, are not only keeping at least a little money in cash investments, but also holding down fixed living costs such as mortgage or rent, utilities, insurance premiums, property taxes and so on. The lower these costs relative to our income, the more financial breathing room we’ll have.

3. Don’t spend under the influence. We might think we’re independent thinkers who make clear-eyed purchase decisions based on our own unique personal preferences. The reality: Our consumption choices are often heavily influenced by corporate marketing, what our friends purchase and how our parents spent when we were growing up.

For instance, my father loved to eat out, and I think I’ve long been influenced by his behavior. Indeed, in the four years since I moved to Philadelphia, Elaine and I have tried many of the city’s finest restaurants. But now, I’m wondering whether I’m suffering from restaurant fatigue—because I’m just as happy when we sit in the park, eat a takeout salad and surreptitiously drink a bottle of wine.

4. Ponder pleasure per dollar spent. Just as our inexpensive dinners in the park deliver as much happiness as pricey restaurant meals, the pleasure from other small purchases is often disproportionately large relative to the price tag.

For example, while I continue to be wowed by the six-figure remodeling project we undertook last year, I can’t claim that the happiness I’ve received has been proportional to the cost. Yes, the cumulative pleasure might be 1,000 times greater than that from a takeout pizza—but, let’s face it, the pizza would only cost $20.

5. Looking forward. I like to book our vacations far in advance. Why? With the help of the internet, I enjoy researching countless possible trips and, along the way, I get to take all kinds of wonderful vacations in my head. And once we settle on a destination, there’s the chance for months of eager anticipation, which is often almost as much fun as the trip itself.

6. A gradually rising standard of living is a great pleasure. For our December flight to London for my son’s wedding, I booked us seats in premium economy—a marked improvement over regular economy, where I tend to sleep fitfully and arrive feeling wretched. Premium economy is the small luxury I’ve allowed myself in recent years for overnight flights to Europe. After all those decades in economy, it feels like a huge improvement.

After I booked our London tickets, I noticed on the British Airways website that I could upgrade us to a flatbed for $1,064 apiece. My younger self would have considered that an unthinkable extravagance. My older self jumped at the chance. Okay, maybe not jumped. But my dithering over the decision probably only lasted 10 minutes.

7. Giving can be as satisfying as spending. Given my diagnosis, I could spend with reckless abandon—and I certainly shouldn’t be fretting over a $1,064 flatbed. But every dollar I spend is a dollar that won’t go to Elaine and my two kids, and that’s more important to me than my own comfort. Whether it’s family, friends or charity, there’s great pleasure in being generous with our time and money—a pleasure that outweighs and outlasts anything I can imagine buying.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on X @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post My Spending Rules appeared first on HumbleDollar.