Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 5

November 15, 2025

When to walk away

I'm sure we could swap stories about working particularly hard at some point in our life. Feeling exhausted, worn out, temperamental and not performing at our best. In an ideal world we would avoid such stresses and strains, but in reality going "above and beyond" seems to be part of securing some financial stability, raising a family, buying a house, funding retirement, or whatever your financial goals might be.

But a recent local news article got me thinking about where each of us draws the line and says "enough".

ABC News (Australia) reports that Miwah Van, a senior executive, is suing Woolworths for discrimination and adverse action. Woolworths is one of our two large supermarket chains. Ms Van has reported suffering from a suspected stroke, temporary blindness and being hospitalised 5 times. A diagnosis of breast cancer and subsequent treatment from her employer also raised claims of bullying.

After reading the article, I remain unsure of where any fault might lay. Senior executive roles obviously require a very strong personal commitment, including long hours, high stress levels and a need to shoulder a lot of responsibility. But maybe Woolworths' demands were excessive, putting way too much on Ms Van's plate. Honestly, I don't know.

What I do know is that if I was in Ms Van's position, once my health was noticeably suffering, I would have been out of there. I'm sure that Ms Van was compensated handsomely in a senior role with one of our largest companies. But what value is a large salary if the situation sends you to hospital with a stroke?

After persisting at Woolworths whilst her health deteriorated, she is now bringing legal action that will no doubt take many months, if not years. That legal action will be stressful. The whole ordeal will be turned over again and again. I can't imagine that any of that will help Ms Van's health. If her action is successful, she will walk away with a sum of money. But at what cost?

I'm sure there is an argument for Ms Van to remain in her role to the bitter end, to bring legal action against her employer and hold them to account. Part of me admires her tenacity to grit her teeth and persist.

But for me personally, my "enough" is a long way from Ms Van's. I'll take my health over a job.

The post When to walk away appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Dealing with Financial Affairs for Someone Else…..

This is a thought exercise…

Suppose you are the son or daughter of a reasonably tech competent older person. They have asked you to step in to act on their behalf should they be unable to do so on their own. The would name you as primary on their Durable Power of Attorney. You have agreed and are in the process of trying to understand how your parent deals with their finances now.

In your research you have discovered the following information:

1) Your parent uses a variety of tech equipment to deal with finances. This equipment includes a Windows 11 PC, an Apple IPhone, and an Apple IPad.

2) These devices all have a PW manager installed. The PW manager automatically synchronizes data across all devices.

3) The IPhone uses facial recognition in addition to a numerical access code. The IPad uses fingerprint data for access in addition to a numerical access code. The Windows PC only uses a numerical access code.

4) The parent has 2 bank accounts, 5 credit card accounts of which only 2 are really used, and 4 brokerage accounts (1 broker).

5) There is a bill pay service at one of the banks which is used to pay any bills which are not set up to be paid automatically via direct debits, or credit card debits. The credit cars are auto pay through the bill pay service.

6) The parent uses Quicken to record all financial transactions for all accounts and has done so for 25 years.

7) Most bills are delivered via your parent’s primary email address. Exceptions are property taxes and HOA fees and a cell phone bill.

8) The parent does their own taxes using TurboTax desktop and stores all the returns and data in Dropbox.

You quickly determine that you need to have both the phone and the PC as a minimum if you are to step into your parent’s shoes financially. BUT, even if you have the devices, there are some catch-22 issues; you cannot satisfy the existing biometric requirements. So, you need the numerical access codes for all devices. You also need the PW manager’s PW, because on the phone and IPad, the alternate to using the PW is biometric. The PC uses the same numeric code for access to the PW manager as to the device. So, you think you can just use the PC and skip the phone. Unfortunately, the primary brokerage/bank access requires use of an authentication APP which resides only on the phone. Dropbox access, like many other providers, uses 2factor authentication through text messages to the IPhone. Fortunately, the IPhone allows addition of a second face/fingerprint for access, provided you have the parent present to show their face as authentication for adding another face. This might be hard to do unless done before need arose.

Because you live in another state, you think that you should setup email access to the parent’s primary email address so that you can see bills that arrive by email. You quickly find out that Gmail requires a passcode which comes from the parent's phone for you to sign into the email account. Boy, you think, nothing about this is easy!

Thought exercises are useful because they help us realize that everything in the modern world is much more complicated than we realize. There is obviously more involved in effectively setting up someone to act on your behalf than just naming them in a legal document. And this exercise didn’t cover things like the need to communicate your investment philosophy, budget, financial goals, things that you might have begun, like a home improvement. It just dealt with what you would have to do from a tech point of view to allow another person to act for you. I am writing this because I just spent the last 3 days with one of my sons trying to figure out what he would need to really do this for me. Your own tech situation will be different from mine; different gear etc.

The post Dealing with Financial Affairs for Someone Else….. appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 14, 2025

Private Equity Traps

After some restoration work, the pair succeeded in having it authenticated as a work of Leonardo da Vinci. Since then, the painting has changed hands a number of times, most recently for $450 million. In that last sale, it became the highest-dollar art transaction ever.

Prior to its sale back in 2005, the painting had been hanging in the Baton Rouge home of a fellow named Basil Hendry. His family put it up for sale when he died, having no idea that the dilapidated work was a da Vinci. If they’ve been following the news since, I imagine they aren’t too pleased.

For most people, these kinds of things aren’t everyday concerns. But it does highlight an issue which is worth our attention, and that’s the challenge posed by appearances. In the case of the Salvator Mundi, the painting ended up being worth much more than it initially appeared. But when it comes to our personal finances, there’s the opposite risk: that things often appear more valuable than they are.

That’s for a few reasons. For starters, there’s the marketing concept known as value-based pricing. The idea is that consumers generally associate value with price. In other words, if a product carries a higher price, we tend to interpret that as a signal of quality. Price serves as a shortcut of sorts in making consumer choices.

There’s a well-known story, in fact, about the eyeglass chain Warby Parker. The group that founded the company met while they were students at the Wharton School. The founders had determined that they could sell glasses profitably for just $45, but they figured they’d ask their marketing professor, Jagmohan Raju, for advice. After looking at the numbers, Raju didn’t disagree that they could make a profit at $49 but nonetheless suggested they price them at $99.

Why? Raju felt that consumers might worry about the quality of Warby Parker’s product if the price were too low. “There are many companies selling cheap eyeglasses. Anyone can go on the Internet and buy two pairs for $99. But there is a perception among customers that the quality is not as good.” So Warby Parker went with $99 and has been very successful.

In many cases, it’s a useful mental shortcut for consumers to associate price with value. But when it comes to investing, it can work against us. The late Jack Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, summed it up best: “In investing, you get what you don’t pay for.” Price, in other words, is not a good signal of value. According to the data, it’s the opposite. Higher-priced investments have delivered worse performance, not better.

Investors know this, but still, it’s a challenge to sidestep high-priced funds. Why is that?

Author William Bernstein quotes the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, who wryly commented, “The world of finance hails the invention of the wheel over and over again, often in a slightly more unstable version.”

Wall Street, in other words, is very good at marketing. As consumers, we know what to expect from high-priced investments, but the industry is always finding new ways to convince us it can somehow defy the odds.

Which of Wall Street’s “innovations” should concern us most today? In my view, it’s a category known as private equity.

Private equity refers to investments in businesses that aren’t publicly traded. The pitch here is simple: Due to the growth of big tech companies such as Apple, Google and Nvidia, public markets have become very top-heavy. Today, more than 40% of the S&P 500 is riding on just 10 stocks. Historically, this has been much lower—between 20% and 30%. To detractors, this concentration means that public markets carry significant risk. For that reason, they see private equity, which is less top-heavy, as a good alternative.

Promoters of private equity also point to the fact that the number of public companies has fallen in recent years. For a variety of reasons, more companies are choosing to stay private. As a result, public markets are narrower than they were in the past.

I don’t deny either of these points. The question, though, is whether private equity is necessarily the right answer. In my view, there are quite a few other, simpler and better alternatives. There are mid- and small-cap funds, value funds and international funds—all of which allow investors to diversify beyond the big-tech exposure in the S&P 500 without venturing into private equity.

Why don’t I recommend private equity? I see five potential issues.

First, the government requires far less regulatory oversight of private funds. In contrast, especially with big mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, there is daily visibility into their holdings. That leaves much less room for mischief.

Private funds are almost universally more expensive than simple, publicly-traded index funds. Worse yet, because of the labyrinthine nature of some funds, it can be difficult to even know what the fees are.

Private funds also tend to be less diversified. That’s because the process of investing in private companies is complicated, requiring due diligence, negotiations and extensive documentation. All of this is time-consuming and expensive, so private fund managers don’t have time to make a large number of investments. Thus, these funds end up not being very diversified.

Private funds like to hold themselves out as being lower risk because the share prices of private companies don’t bounce around as much as the stock prices of public companies. That’s a clever argument but a little disingenuous. Unlike publicly-traded mutual funds, which are priced every day—and exchange-traded funds, which are priced throughout the day—private funds are often priced only on a quarterly basis. So their prices only appear less volatile. But that doesn’t mean they’re actually less risky.

The final concern with private funds stems from a combination of illiquidity and complexity. This year, a number of universities have had budgetary issues, and as a result, they’ve been scrambling to raise cash. Schools are big holders of private funds, but selling them hasn’t been easy. Because these funds aren’t tradeable on stock exchanges, the only offramp is through what’s known as the “secondary” market, where transparency is more limited. This added complexity doesn’t necessarily make these funds more risky—but it does make it much harder for investors to distinguish between a da Vinci and something that might just look like one.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on X @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Private Equity Traps appeared first on HumbleDollar.

IRS 2026 Updates

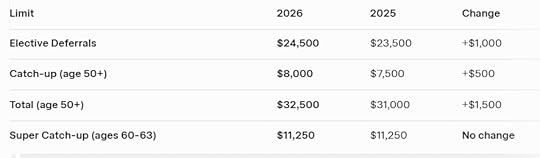

401(k), 403(b), and Most 457 Plans:

For 2026, the 401(k)/403(b)/457(b) amount you can contribute is increasing from $23,500 to $24,500. If you are in a 24% marginal tax rate, that’s an additional $240 of federal taxes you can defer. If you are over age 50, the catch-up contributions are also increasing by $500, which is a small increase.

Defined Contribution Plans, §415(c)

The annual total contribution limit is increasing to $72,000 (up from $70,000).

This means that your employee contributions + employer contributions + after-tax contributions cannot exceed $72,000 in 2026.

Many people only have employee + employer contributions, but if you are self-employed with a Solo 401(k) or working for a big Fortune 500 tech company, you may have the option of making after-tax contributions. The strategy is called the “Mega Backdoor Roth,” which allows you to contribute thousands extra into your Roth 401(k)/Roth IRA.

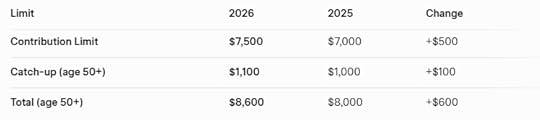

IRAs (Traditional & Roth)

For 2026, the Roth/Traditional IRA limits are increasing by $500 to $7,500.

Note that the Roth IRA income limits to contribute are also increasing in 2026. Direct Roth IRA contributions aren’t allowed if your modified adjusted gross income is over $168,000 (single) or $252,000 (married filing jointly).

However, you can still use the "Backdoor Roth" strategy to get around these income limits by doing a non-deductible IRA contribution that gets converted into a Roth. Just make sure you are aware of the pro-rata rule.

Other Adjustments

Earlier in the month, IRS released more details on other key adjustments for 2026:

1. Standard deduction

Married filing jointly: $32,200 (from $31,500)

Single: $16,100 (from $15,750)

Heads of households: $24,150

Note that the OBBBA also increased the standard deduction from $15,000 to $15,750 for 2025.

2. Estate tax exclusion

The estate tax exclusion is increasing from $13,990,000 in 2025 to $15,000,000 in 2026 due to OBBBA changes.

3. HSA

In 2026, you can contribute up to $4,400 if you are covered by a high-deductible health plan just for yourself, or $8,750 if you have coverage for your family to HSA.

4. Tax Brackets

All tax bracket limits are increasing by ~4%. Here are the 2026 brackets:

12% for incomes over $12,400 (over $24,800 for married couples filing jointly)

22% for incomes over $50,400 (over $100,800 for married couples filing jointly)

24% for incomes over $105,700 (over $211,400 for married couples filing jointly)

32% for incomes over $201,775 (over $403,550 for married couples filing jointly)

35% for incomes over $256,225 (over $512,450 for married couples filing jointly)

37% for incomes over $640,600 (over $768,700 for married couples)

5. QCD

The QCD limit (age 70½+) is also increasing to $111,000 (from $108,000), which is the maximum charitable gift from an IRA that can be excluded from your income.

So overall, most of the deductions or limits are increasing by 3–4% on average.

Take advantage of these limits and maximize your tax-efficient retirement savings!

Bogdan Sheremeta is a licensed CPA based in Illinois with experience at Deloitte and a Fortune 200 multinational.

Bogdan Sheremeta is a licensed CPA based in Illinois with experience at Deloitte and a Fortune 200 multinational.The post IRS 2026 Updates appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Something fishy about financial security

Have I got a job for you.

As a boy I was into tropical fish. I had several tanks, I raised fish and tried to sell them - anything to make money. At one point I had eight large tanks of fish.

At 13 I wangled my way into a job after school and Saturday at a pet store for $5.00 a week and the occasional free fish.

After all these years I finally learned the money in tropical fish is not in the fish, but in taking care of them. So, if you are looking for a post-retirement gig or just a part-time job, I have the job for you.

Yesterday I was in a doctor’s waiting room fascinated with a 55 gallon tank of fish. While there, a guy arrives and starts cleaning the tank. We chatted - about fish - and I finally asked what it cost for the tank maintenance service. I visit here every two weeks or so he said. This cleaning will be $350. I silently gulped. I have been lobbying Connie to have a tank of fish with no luck, but I thought if I had it maintained I could make a deal. But $350 a pop? I don’t think so.

Further discussion revealed his fee was $150 the first hour plus $2.00 a minute thereafter - more for a salt water tank. My mind drifted to those fish tanks I cleaned for $5.00 a week, admittedly in 1956, still only $59.16 in 2025. Back then it was about equal to $0.30 an hour- not as good as my next summer job in the town library at $0.75 an hour- the minimum wage was $1.00 in 1960.

As I said, (almost) anything to make money. I worked in the base library the first time I was in the army too.

One of the reasons I spent nine years in school at night to get degrees was that I couldn’t afford to stop. For several years my VA education benefits exceeded the tuition cost because the VA benefits were based on family size so each child brought more tax-free income.

Today two of our sons work part-time jobs to make ends meet. One started a home improvement business-he is quite good at it, last week a customer gave him a $1,000 tip. He also collects scrap metal which can be lucrative, especially discarded copper pipes and wires, not what you might expect for someone with a masters degree, but I must have set some type of example.

The other son gets up very early to drive a school bus for needed income. He sells real estate by day - no sales, no pay.

You do what you have to do, not for luxuries, but for present and future necessities.

What triggered this post was an article that claimed to list what is necessary to live a good life. The travel item of $6,000 a year for a family caught my eye and made me think of how many people set their priorities.

Whether it be cleaning up after fish, pleasing demanding homeowners or shuttling loud schoolchildren, you do what is necessary to meet your financial needs and goals. That’s the way I see it anyway.

The post Something fishy about financial security appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 13, 2025

Mutual fund tax distribution season is approaching.

I SOLD A MUTUAL FUND in my taxable account that was up an average 6% a year over the past 10 years—and ended up with a tax loss. That’s right, I took a loss on this international fund, even though it had returned 6% a year. How does that happen?

Suppose you bought one share of a mutual fund for $12 on Jan. 3. Over the course of the year, the fund’s investments fare well. On Nov. 15, the fund’s shares are worth $14. The manager sells the fund’s winners at a profit. The fund’s shares are still worth $14, but now—instead of the winning stocks—the fund has the cash from selling those investments.

On Nov. 30, the manager declares a $4 capital-gains distribution, payable on Dec. 1. On Dec. 2, the fund’s shares are now worth $10 and you have a check for $4. All told, you still have $14. If you sell the fund on Dec. 2, you’ll realize $10, less than your $12 purchase price. You’ll take a loss of $2, even though your pretax wealth has increased by $2.

All is good—until tax time. That’s when you’ll report the $4 capital-gains distribution that’ll be shown on Form 1099-DIV. The manager reports that the distribution includes $2 in short-term gains and $2 in long-term gains. How can you receive long-term gains when you only owned the fund for 11 months? Whether they’re long-term or short-term gains will be based on when the fund bought the stocks that it sold.

Meanwhile, you will take a $2 loss for selling the fund, which you bought for $12 and sold for $10. Netting all this out, you pay tax on a long-term gain of $2. In effect, your tax bill as a fund shareholder depends not only on the fund manager’s actions, but also on your decision to sell the fund.

IRS rules require mutual funds to distribute 95% of their net income and realized capital gains each year. Funds are pass-through structures for tax purposes. A mutual fund itself doesn’t pay any taxes. Instead, gains and dividends flow through to the fund’s shareholders.

When I started saving 30 years ago, I found dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs) to be a simple and efficient means to amass shares of individual stocks, including by reinvesting dividends. DRIPs offered low costs and the ability to buy a fraction of a share. Similarly, mutual funds allowed me to reinvest dividends and capital gains with no minimums.

Since then, the cost of investing has dropped and I’ve become more tax sensitive, leading me to invest more in index funds. They have lower turnover, meaning they’re slower to sell their winners, plus they have other methods of reducing their capital-gains distributions.

What do you do if you have a capital gain on a fund that you’d like to sell because it isn’t tax-efficient? First, check that you really have a taxable gain with the fund, by making sure you’re calculating your cost basis correctly. That cost basis would include both your investments in the fund and any distributions that you reinvested in additional fund shares. Funds and brokers have only been required to keep track of an investor’s cost basis since 2010. Their reported number may be different from your actual cost basis.

Next, stop reinvesting fund distributions. Instead, direct those distributions to a more tax-efficient fund.

What if you really want active management? Ideally, you’d invest with the active manager through your IRA. What if you’re considering buying an actively managed fund in your taxable account? Look at the fund’s embedded gains. These are the unrealized gains that will be realized if the manager sells. A fund’s annual report will include information on unrealized gains. Compare these unrealized gains to the fund’s total assets to see how significant they are.

A final tip: If you’re purchasing index mutual funds in your taxable account, look to invest in a fund that has a companion exchange-traded fund—a so-called dual-share-class fund. These funds tend to be especially tax-efficient. Vanguard Group owned a patent on this structure that recently expired, so other managers are now creating dual-class funds, including Morgan Stanley and Fidelity Investments.

Matt Halperin, CFA, is the founder of

Act2 Financial

, an app that helps seniors avoid financial fraud. For 30 years, he worked as a portfolio manager and risk manager at large U.S. money managers. Matt currently serves on the investment committee of two endowments. He has a BA and MBA from the University of Chicago, and resides outside of Boston.

Matt Halperin, CFA, is the founder of

Act2 Financial

, an app that helps seniors avoid financial fraud. For 30 years, he worked as a portfolio manager and risk manager at large U.S. money managers. Matt currently serves on the investment committee of two endowments. He has a BA and MBA from the University of Chicago, and resides outside of Boston.The post Mutual fund tax distribution season is approaching. appeared first on HumbleDollar.

IRS Adds New Reporting Code for Charitable IRA Gifts

Until now, however, QCDs came with a thorny reporting headache. They were reported on IRS Form 1099-R as a regular distribution from an IRA, with no indication that the amount was a QCD.

Effective 2025, an IRA custodian may enter Code Y in Box 7 of Form 1099-R to show that the amount represents a QCD. Code Y is paired with another distribution code to provide more detail:

Code 7 for a QCD from a noninherited (normal distribution) IRA.

Code 4 for a QCD from an inherited IRA.

Code K for a QCD involving traditional IRA assets without a readily available fair market value. Colloquially referred to as “self-directed IRAs.”

Here is the web address for the article:

The post IRS Adds New Reporting Code for Charitable IRA Gifts appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Certainty addiction in financial decision-making

In my short time in this forum, I've noticed that we spend considerable time discussing both commendable and questionable decisions—our own and others'. Exploring these decisions humbly and methodically can be quite helpful. Models of behavior are one of the fundamental ways we learn ethics and good decision-making, and I've certainly gained wisdom from the stories many of you have shared.

This past Tuesday, while driving to CrossFit, I listened to a stimulating conversation on "The Rational Reminder Podcast" with Ted Cadsby, a former executive at CIBC, a Canadian financial firm (Episode 382). The podcast began with a discussion of the power of index fund investing but then shifted toward human nature and how our evolutionary development has created "design flaws" that affect our lives and investment decisions. What worked so well for us when we roamed the savannah doesn't serve us as well in modern life.

While Cadsby works in finance, he majored in philosophy and has spent considerable time explaining how insights from the field of human cognition relate to finance and investing. (As a lifelong advocate of the liberal arts, I'm particularly drawn to stories of humanities majors who apply their insights to fields that, at first glance, seem far removed from the humanities.)

In this podcast and in his book, "Hard to be Human,"Cadsby identifies five cognitive "design flaws" that, while sometimes helpful, also lead us to make errors in logical analysis:

Greedy reductionism - our tendency to oversimplify complex ideas and systemsCertainty addiction - our tendency to crave the feeling of "knowing something" even when we're wrongEmotional hostage-taking - our tendency to overreact emotionally and then ruminate obsessively over issuesCompeting selves - our tendency to collapse our competing identities into one unified selfMisguided search for meaning - our tendency to overestimate the belief that we have inherent meaning and purpose in lifeCertainty Addiction in Focus

Let's review one of these design flaws more closely.

Certainty addiction is the tendency to derive more pleasure from the feeling of "knowing" something in a conversation or argument than from actually checking our facts or entertaining the possibility that we might be wrong (which does not feel so great). Our pleasure comes not from actually knowing or understanding something, but from the belief that we know or understand it.

While certainty addiction may serve us well when confronted by a rattlesnake in the forest, it's less helpful in determining how best to invest in the stock and bond markets. I suppose this is why indexing is so powerful—you don't have to know precisely where stock value is headed because you've bought the whole sector or market.

That said, I've met so many advisors who "know" how to best invest, and they all offer different, even contradictory advice. I now see that they're rewarded emotionally for "knowing," despite the fact that they don't really know. In that feedback loop, they become addicted to the certainty of their own advice. (Having taught in academia for most of my career, I would say we academics are quite prone to certaintly addiction.)

This raises important questions: How can we recognize certainty addiction in others? Perhaps more importantly, how can we best avoid certainty addiction in ourselves when it comes to financial decisions?

The post Certainty addiction in financial decision-making appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Retirement Conversations with my Joints

I've decided my outer extremities have made the giant leap to sentience. I think it's a distributed system. Over the last nearly sixty years, my only internal monologue was the one happening between my ears. Thankfully it's always been a single voice and not a baker's dozen whispering peculiar thoughts.

Retirement seems to have been the breakthrough point. I'll be sitting in a quiet room, minding my own business, when the rebellious parts of my anatomy decide to join the party.

I'll be wondering to myself if a nice chicken sandwich would be the salvation to my hunger pangs and my left shoulder will make an alarmingly loud crack in agreement. I must admit I was in full agreement. Last week I fluffed an easy backhand slice during a game of doubles tennis, not only did my partner complain, but my wrist decided to interject with a few sharp clicks in support of that view.

I'd obviously heard the saying "listen to your body," but quite frankly, I never imagined this is what they were on about. Deciding to move on from the park bench I was resting on after a run, my left knee decided in a strange crunchy, grinding voice to pipe up and firmly express the opinion that another ten minutes sitting on my butt would be an excellent idea. Thankfully said butt decided not to join the conversation.

My most recent skirmish with the sentient extremities occurred this morning as I laced up my most comfortable pair of walking shoes. I had chosen the old leather pair, sturdy and well-worn, for a long trudge down to the market. Before I could even tie the bow, my right ankle began a rapid, dry ticking noise, like a tiny, angry clock. "Not those again," it hissed, not quite a crack, more a series of insistent snaps. "We both know you should have thrown those relics out a year ago. They offer the lateral support of a damp sponge and they smell faintly of regret." My left ankle joined in with a lower, mournful groan. "The sneakers, please. The new ones with the gel cushion. Have some compassion for your foundational infrastructure. We are barely holding the line against gravity as it is." I sighed, untying the laces.

But the most demanding of all was my neck. As I simply tilted my head to read the tiny print on the shoe tongue, it let out a long, resonant creak that clearly articulated a single, non-negotiable directive: it demanded a very hot shower, immediately. Just like that, my washing schedule is no longer my own.

And now, even the simple pleasure of reading is under review. My finger joints have become utterly insistent that they no longer want to hold heavy paperback books. "Technology has moved on," they declared in a chorus of stiff, grating pops. They now demand I switch to a nice, light Kindle, and have made it clear that they're going to keep going on about it, one crack and cramp at a time. They are not only talking to me, but threatening pain for non-compliance. My body is now a collective of highly articulate, highly demanding tyrants.

So this is retirement: plenty of free time, no alarm clock, and absolute autonomy, except I'm now governed by a coalition of creaking joints who've formed a very vocal union seeking better working conditions. At least they can't fire me, though I suspect they're planning on a vote of no confidence.

The post Retirement Conversations with my Joints appeared first on HumbleDollar.

November 12, 2025

THE REAL RETURN ON DELAYING SOCIAL SECURITY

EVERY FEW MONTHS, I come across yet another article claiming that delaying Social Security is like earning an 8% guaranteed return. It’s a comforting phrase—clean, simple, and easy to repeat. Unfortunately, it isn’t true.

Yes, the Social Security Administration awards an 8% delayed retirement credit for each year you postpone benefits beyond full retirement age. But that 8% is simple interest, not compound. And no matter how attractive the credit looks on the surface, it ignores an uncomfortable fact: You’re giving up three full years of monthly checks to earn it.

When we account for the actual cash flows—what we give up and what we get back—the real return looks very different.

A REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE

Take someone born in 1960 or later. Their full retirement age is 67. If they delay benefits to age 70, here’s what happens:

They skip 36 monthly payments.They earn 24% more in monthly benefits for the rest of their life.Suppose the age-67 benefit is $1,000 a month. Delaying means turning down $36,000 over three years (36 × $1,000). At age 70, the monthly benefit jumps to $1,240—a $240 increase.

So what’s the rate of return on the $36,000 “investment” needed to earn an extra $240 a month for life?

This is where the math tells a much quieter story than the 8% billboard slogan.

THE TRUE RATE OF RETURN

Using a basic internal rate of return (IRR) calculation—treating the skipped payments as an upfront cost and the extra income as a lifetime annuity—the result comes out to:

Approximately 5.3% to 5.5% per year, inflation-adjusted.

That’s the conclusion reached by:

The Social Security Administration (~5.3%)Mike Piper’s Open Social Security calculator (~5.25%)Research from Kitces, Wade Pfau, and Bogleheads contributors (5.0%–5.6%)My own spreadsheet calculation (5.48%)Why isn’t it 8%?

Because:

The 8% credit is simple, not compound.You give up three years of payments upfront.The boosted benefit doesn’t start until age 70.Mortality matters—you might not live long enough to enjoy the higher payments.Add these factors together and the real return shrinks by roughly 2.5 to 3 percentage points.

Still good? Yes. But not magical.

THE BREAK-EVEN AGE

Another way to look at the decision: When do you come out ahead?

If you live past 83 or 84, delaying benefits to 70 produces more total dollars.If you die before 83, claiming at 67 would have put more money in your pocket.Those ages assume today’s average life expectancy—about 84 for men and 87 for women once you’ve already reached 67.

In other words, for someone in average or better health, delaying remains a solid deal. But the real advantage depends on living long enough to enjoy it.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR RETIREES

The truth sits somewhere between the headlines:

No, delaying doesn’t earn 8%.The real return—roughly 5.3%—is still quite respectable, especially in a world where “risk-free” real returns hover close to zero.The decision to delay should still factor in health, longevity expectations, cash-flow needs, spousal benefits, and tax planning. But at least the math is clear: the famous 8% credit overstates the true economic return by a meaningful margin.

BOTTOM LINE

Delaying Social Security from 67 to 70 offers a real return closer to 5.3%, not 8%. That’s still a strong, inflation-adjusted, government-backed payout—but it isn’t the free lunch it’s often advertised to be.

Like most things in retirement planning, the best decision depends less on slogans and more on understanding the numbers.

Note: AI helped me with the math.

The post THE REAL RETURN ON DELAYING SOCIAL SECURITY appeared first on HumbleDollar.