Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 360

June 20, 2019

A Fine Example

MY MOTHER is 95 years old and in fairly good shape for her age. Yes, she repeats herself quite often. When she does, I tend to let it go in one ear and out the other.

When she talks about my father, however, I listen very closely. One day, as I was backing the car out of the garage, she looked at all the cabinets my father built and said for the umpteenth time, ���Sam was a smart man. Look at all the things he designed and built.���

My father was one of the wisest men I���ve ever known. He was a machinist by trade. But he was very knowledgeable about life in general, including personal finance. I still remember something he said to me when I was young:��“It’s not how much money you make that���s important. It’s what you do with your money that���s important.”

One day, I asked my father when would be a good time to invest some extra money I received from my employer. He answered ���yesterday������a reminder of the importance of investing early.

He never tried to time the stock market or game the system in other ways. He was a meat-and-potatoes kind of investor. Just invest your money in a low-cost diversified fund and watch it grow. Today, my mother is still living off the money that her and my father invested. Isn���t that proof that you don���t have to reinvent the wheel when it comes to investing?

Not only did I learn the basic principles about investing from my father, but also he instilled in me a work ethic that propelled me through my life.��When I was a teenager, I used to watch him get up early to go to work and come home late in the evening. He sometimes did this six days a week. He and my mother also managed a 36-unit apartment building that required a lot of his time.

I used to say to myself, ���How does this man work so hard?��� Then, one summer during high school, I found myself working 50-plus hours a week at my father���s employer. Before I knew it, I was working six days a week, just like him.

That hard work continued throughout my career. It opened doors for me and earned me numerous promotions. One day, I was sitting in the office of my future boss. He was looking at my resume. He said, ���I see you have an MBA. What really impresses me is not so much that you have an MBA, but you earned it while working fulltime. That tells me a lot about your character. That took a lot of commitment and hard work.���

The comment says less about me and more about the type of person my father was: He was a hard-working, blue-collar worker who wasn���t afraid to get his hands dirty���and that was the example I strove to emulate. With the money he earned, he was able to build an investment portfolio that would provide a comfortable retirement for him and his wife. His financial success was built on three simple principles: Work hard, save and invest in low-cost, diversified funds.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Building Wealth,��Not My Priority��and��Power of Two.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Building Wealth,��Not My Priority��and��Power of Two.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

Do you enjoy the articles by Dennis and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post A Fine Example appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 19, 2019

Fast Forward

HOLDING��DOWN living expenses is one part of the equation in achieving financial independence. But the other part is diligently and consistently saving and investing money.

On that score, my husband Jim and I enjoyed four ���lucky breaks��� that accelerated our push for financial independence. Together, they helped catapult us into early retirement in just 15 years.

1. The Great Recession may have caused much short-term financial harm, but it also offered a great long-term opportunity.

When the stock market crashed, we continued to max out our 401(k) and 403(b) plans, as well as contributing to 529 plans for our two boys��� college costs. We put these various accounts 100% into stock mutual funds, taking advantage of the lower share prices. In 2017, as we prepared to retire, I moved some money out of stocks and into bonds. I was stunned by how much we had earned.

2. During the Great Recession, I mentally prepared for the possibility that one of us would get laid off���most likely me, because I worked for a bank. That never happened. Both of us kept our jobs.

Still, we strove to live as though we had just one income. When I got a raise or Jim earned extra from teaching summer school, we saved the money. We didn���t starve ourselves or skip family vacations. But we also didn���t pony up for a new car or new bathroom or new kitchen.

3. One of our sons received a full scholarship to one of the top public universities in Texas. That made college far less of a financial burden���and, as a result, both our boys were able to graduate from university with no debt. In fact, we even had some money left over in a 529 account. We owed taxes on the account���s earnings, but we were able to withdraw the original contributions with no tax cost.

4. While visiting an estate sale, we discovered a townhouse for sale next door. It was our good fortune to see the realtor putting up the sign. Our boys had just moved into university dorms, so there was no need for us to keep our current house.

We decided to take advantage of the hot Dallas real estate market by selling the house and buying the smaller townhome. That allowed us to pay off our mortgage earlier than planned.

While our four lucky breaks helped us achieve financial independence that much earlier, I suspect we would have got there soon enough. It all comes down to the same basic strategy: You need to save diligently, while minimizing unnecessary expenses, by always focusing on the difference between needs and wants. Just as money compounds in the stock market, the benefit of living beneath your means also compounds over time���and, with surprising speed, you can get your reward.

Last year, at age 53, Jiab Wasserman left her job as a financial analyst at a large bank. She’s now semi-retired. Her previous articles include Living for Less,��Courting Success��and��

Buen Camino

.

��Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Granada, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement���as well as about their experience relocating to another country���at��

YourThirdLife.com

.

Last year, at age 53, Jiab Wasserman left her job as a financial analyst at a large bank. She’s now semi-retired. Her previous articles include Living for Less,��Courting Success��and��

Buen Camino

.

��Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Granada, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement���as well as about their experience relocating to another country���at��

YourThirdLife.com

.

Do you enjoy articles by Jiab and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Fast Forward appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 18, 2019

Prime of Life

I WAS 51-years-old when I ate prime rib for the first time. As it turned out, it was a life-changing moment. It might be difficult to believe eating a choice cut of beef could lead to an altered understanding of financial priorities, but it did.

I grew up in a fairly typical 1970s middle class family. Hamburger Helper, tuna casserole and peanut butter sandwiches made up the bulk of my diet. Our family rarely ate out and, when we did, it was almost always at McDonald���s. When I was a teenager, I got to pick where I wanted to dine on my birthday and usually opted for the local all-you-can-eat buffet. Having unlimited access to fried chicken, baked beans and soft serve ice cream seemed like gourmet dining to me.

I think it���s safe to say I didn���t develop a sophisticated palate as a child.

When I was in college, money was tight and my roommate and I subsisted almost entirely on Top Ramen and grilled cheese sandwiches, with the occasional splurge on a frozen pizza. When I graduated and married, my cooking skills were, not surprisingly, fairly limited. Tacos and spaghetti were the two main dishes I knew how to make. I slowly taught myself how to cook more elaborate meals, but ground beef and chicken were almost always the main ingredients of any meal I prepared.

When I divorced and began living on my own, my self-imposed frugality heavily influenced my meal plans. I started eating more fresh fruits and vegetables. But as a financial tradeoff, I would often forgo meat. I saw food as an expense that, while necessary, could be controlled by simply opting for low-cost ingredients. My frugal mindset didn���t necessarily carry over to all the members of my household. My corgi often ate food that cost more per pound than my meals.

In short, I viewed food as a necessity and not something to be enjoyed.

When I remarried, I discovered a new side of food. My husband rarely compares prices on grocery items and instead chooses to buy whatever he knows he likes. He enjoys savoring a good meal and wouldn���t consider skimping on it for the sake of saving a few pennies. When he suggested cooking a prime rib for Christmas dinner last year, I agreed, even though I didn���t know what a prime rib was���or the cost.

When we went to the local supermarket to get the roast, my husband spoke directly to the meat department manager and described exactly what cut he wanted. A few minutes later, as we were walking to the register, I snuck a peek at the price tag and was surprised at how reasonably priced the roast was. What I hadn���t realized, until we paid at the register, was that I���d misread the label, mistaking a ���7��� for a ���2.��� Our Christmas 2018 dinner was $75, not $25. My thoughts quickly turned south as I realized there had been times in my life when I hadn���t spent $75 on an entire week���s worth of food, much less a single item.

On Christmas day, my Mom joined us and we dined on one of the finest meals I���d ever had. My husband cooked the roast to perfection and I, for once, allowed myself to indulge in the pleasure of food. I���d probably never consumed as much protein in one sitting as I did that evening, but every bite was worth it.

As I grow older, I find myself reflecting more on life���s priorities. I���m realizing how quickly time passes and how fragile life is. I���m learning that the occasional indulgence���be it food, travel or crossing off a bucket-list item���helps keep life interesting. These days, my husband and I plan a ���prime rib night��� once a month. I consider it money well spent.

Kristine Hayes’s previous articles include School’s Out,��Six Year Later��and��State of Change. Kristine��enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their three dogs.

Kristine Hayes’s previous articles include School’s Out,��Six Year Later��and��State of Change. Kristine��enjoys competitive pistol shooting and hanging out with her husband and their three dogs.

Do you enjoy articles by Kristine and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a��donation.

The post Prime of Life appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 17, 2019

Human Factor

MY BIGGEST initial mistake as a financial planner: underestimating the power of emotions. My office is located near top universities such as Harvard, MIT and Boston University. I assumed my well-educated clients, many with strong quantitative backgrounds, were simply looking to me for additional analytical insights.

Instead, my clients proved to be as human as everybody else. One top academic statistician, who claimed to be frugal and cautious, shared with me an annuity policy he purchased from a close friend at his church. Because my client had a trusting relationship with this person, he didn���t bother going through the insurance prospectus.

If he had read the annuity���s fine print, my client would have noticed it included a large upfront commission. When I presented this information when we next met, it was unclear who he was more annoyed at, his salesman friend for not being transparent about the commission���or me for pointing it out.

Over time, I learned that, what may appear to be clearcut from a financial planning perspective, can be more nuanced once you factor in emotions. I had a brilliant academic insist on depleting his retirement account to purchase land, thereby protecting the panoramic view from his patio, which he loved. My risk-reward analysis favored keeping his retirement account in place. This academic praised my retirement analysis and told me that, as his advisor, he did indeed expect to hear about the downside of spending his retirement funds. Yet he still went ahead and purchased the land. A decade later, my client remains content with his choice.

The psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman won a Nobel prize for demonstrating how our cognitive judgments are influenced by innate biases. For example, he showed that we feel our economic losses much more deeply than our gains. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, he demonstrates that important decisions require more deliberate thinking.

Along those lines, I���ve learned to appreciate that clients may be more prone to ill-advised thinking after major market losses���and I take that into account when determining their asset allocation. For instance, if clients are inclined to worry about money but they tell me that they���re comfortable investing 50% to 60% of their portfolio in stocks, I���ll recommend the 50% allocation. Later, when they want to sell part of their stock position during a market decline, I remind them what they had earlier suggested���and how we positioned their portfolio at the conservative end of what they wanted.

My lesson from more than a decade as a financial planner: It���s my job to slow things down and understand a client���s situation holistically.��Planning should be guided by the numbers. But good advising also requires that I truly understand the client���s mindset when presenting the ���right course of action.���

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles were Why Wait and��Help Yourself. Rand

��has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles were Why Wait and��Help Yourself. Rand

��has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Human Factor appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 16, 2019

Math vs. Emotion

YOU���VE NO DOUBT heard this before: Asset allocation is the single most important investment decision. If you have the right mix of stocks, bonds, cash and maybe real estate, you sharply increase your chances of success.��

But how do you pick the right mix? There are rules of thumb based on age, there���s a statistical approach called Modern Portfolio Theory, there are risk tolerance questionnaires and there are cash flow-based approaches. Each delivers a different answer���because each emphasizes different factors.

What if the answers differ dramatically? It’s not uncommon for a strictly mathematical analysis to result in an asset allocation of 100% stocks. Meanwhile, if that same person were to fill out a more qualitative risk questionnaire, the result might be far more conservative.

What should you do if the math says one thing but your stomach says another? Should math trump emotion���or the other way around? As you wrestle with this question, here are five considerations:

1. All math involves assumptions.��If the math says your portfolio can afford maximum risk, ask yourself what assumptions underlie that calculation. In particular, what assumptions are being made about the stock market? If you look back at U.S. stock market history, downturns generally result in losses of 20% to 50% and last two to four years. But notice that I said�����generally.��� During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the market dropped more than 80% and didn’t fully recover for more than a decade.

2. Just because something hasn’t happened recently���or hasn’t happened here���doesn’t mean it can’t happen.��To be sure, the Great Depression was a long time ago, and the stock market now has systems in place to help prevent a crash of similar proportions. But you shouldn’t write off the 1929 crash as ancient history.

Consider Japan. In 1989, it was on top of the world. Its economy and stock market were soaring. But over the subsequent two decades, the Japanese market declined more than 80%. Even today, nearly 30 years later, the Nikkei index stands almost 50% below its peak���a sober reminder that unexpected things can happen.

3. Your needs might change.��Suppose you do the math and determine that your asset allocation is robust, because you have five years of spending money set aside in bonds and cash. In theory, that would carry you through a typical market downturn (though not the Great Depression). But what if something happened���a health issue, for example���and your expenses increased? These kinds of things are impossible to predict, but I think it makes sense to allow for the unexpected when structuring your finances.

4. You might not know your true tolerance for risk.��If you haven’t lived through a 50% market downturn like the U.S. market experienced in 2000-02 and 2007-09, you might not have an appreciation for what it’s like. More to the point, you may not know how you���ll react. If you haven’t yet lived through a true bear market, when all the news is relentlessly bad, you might want a more moderate asset allocation than the math suggests.

5. It might be unnecessary.��One day last summer, I found myself speeding through upstate New York. I had to get to a meeting. But when I looked at the clock, I realized I had plenty of time. I was racing for no reason and risking an expensive run-in with the New York State Police, so I immediately slowed down. If you’ve built up substantial savings, you may be in the same position���taking lots of stock market risk when it’s no longer necessary. If you have the risk dial set to 10, ask yourself whether you’re swinging for the fences, even though you’ve already won the game.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Don’t Bank on It,��Danger Ahead��and��Know Doubt

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Don’t Bank on It,��Danger Ahead��and��Know Doubt

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Do you enjoy the articles by Adam and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Math vs. Emotion appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 15, 2019

Developing Story

I���M A FAN of emerging stock markets���for two key reasons. But I also have qualms���for two key reasons.

Readers frequently write to me about emerging markets, and those messages usually coincide with periods of stomach-churning volatility, which is what we���ve witnessed recently: MSCI���s emerging markets index tumbled 15% in 2018 and was up just 4% in 2019���s first five months���after being up as much as 14% earlier this year. But as I tell my nervous correspondents, I view emerging markets as a permanent part of my portfolio and I fully expect them to be great long-term performers.

The No. 1 reason for my optimism: demographics. As of 2020, developed nations will have three people of working age for every person age 65 and up, according to United Nations figures. By contrast, in the developing world, there will be 7.7 working-age people for every senior���a far more favorable dependency ratio and a key reason emerging markets will enjoy faster economic growth over the next few decades. Developing economies have young, large, fast-growing working-age populations, plus they don���t have the financial burden of supporting substantial numbers of retirees.

The other reason for optimism: valuations. Even though emerging markets should grow more rapidly than the developed world in the years ahead, their stock markets are far��cheaper. Depending on the measure you look at���price/earnings ratios, Shiller P/E, price to cash flow, and so on���emerging stock markets are 20% to 35% cheaper than developed markets.

But offsetting these two key advantages are two major worries. First, investors in emerging markets may see their claim on the economy���s profits constantly diluted. This dilution can occur in two ways. First, publicly traded companies may issue new shares to finance their growth, so existing shareholders own an ever-smaller percentage of these companies. Second, even if an emerging economy is growing rapidly, the fastest growth may be among private companies. These companies may eventually come public���but, at that juncture, their fastest growth may be behind them.

One startling statistic from a recent Financial Analysts Journal��article: Over the two decades through 2017, China���s real per capita GDP grew 8.2% a year���but its stock market���s real return was just 0.7%. Because of dilution, there���s often scant connection between a country���s economic growth and its stock market���s performance.

That brings me to my second major worry: Property rights aren���t as firmly established in emerging economies as they are in the U.S. and other developed nations. In the past, I���ve always figured that most developing countries would think long and hard before seizing the assets of foreign investors, because they would face the wrath of the developed world.

But my confidence on that score has waned somewhat and, once again, it relates to China. MSCI���one of the leading creators of market indexes���recently increased the allocation to China in its emerging markets index. Because of that decision by MSCI, and similar decisions by other index designers, many index funds now have around 30% of their holdings allocated to China. I see that as a cause for concern.

Why? If there���s one emerging economy that���s big enough to push back against foreign pressure, it���s China. We���ve seen that during the current dispute with the U.S. over tariffs. Don���t get me wrong: I have no reason to think China will abrogate the rights of foreign shareholders. But if it did, I doubt the U.S. could bully China into backing down.

What���s the solution? I���m not sure there���s a good one, except to keep the above issues in mind when settling on your allocation to emerging markets. I continue to believe that emerging stock markets hold out the possibility of fabulous long-run returns. But high expected returns come with high risk���and, in the case of emerging markets, that risk goes way beyond market volatility.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��@ClementsMoney��and on Facebook.��His most recent articles include Where It Goes,��Down the Drain��and��Great Debates. Jonathan’s��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��@ClementsMoney��and on Facebook.��His most recent articles include Where It Goes,��Down the Drain��and��Great Debates. Jonathan’s��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Developing Story appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 14, 2019

Building Wealth

I���VE BEEN READING about how people aren���t saving enough money, and how almost half of all Americans carry a balance on their credit cards. Looking to be more financially prudent? Here are 10 pointers on how to build wealth and gain financial security over your lifetime:

1. Save���for a reason. Saving money is the key to building a substantial portfolio. One secret to being a good saver: Have something worthwhile to save for. It might be homeownership or early financial independence.

Whatever it is, write it down and post it where you can see it every day. That constant reminder will keep you on the right track���and help you get in the habit of saving money.

2. Invest in stocks. This is another crucial component of building wealth. My advice: Buy broad-based U.S. and international stock index funds. You���ll capture the stock market���s results at low cost, and that���s proven to be a winning strategy over the long haul.

3. Attend an affordable college. Education debt is a problem for many young Americans. You need to find a quality college that won���t leave you in too big a financial hole. According to research from the College Board, it takes an average 12 years to recoup the cost of a bachelor���s degree.

In other words, by then, you typically have earned enough to recover the cost of the college degree, plus the lost income from the time you were out of the workforce while studying. Use that 12 years as a guideline in choosing a college. Will it take you far longer to recoup your costs? You may want to find a less expensive college.

4. Invest early. Take advantage of compounding by investing as much as possible at a young age. If you do this, you won���t have to save as much to meet your financial goals.

What about the need to build up an emergency fund that���ll cover six months of living expenses? You might fund a Roth IRA���and have it do double duty, both acting as an emergency fund and starting you on long-term investing. You can withdraw your contributions from a Roth at any time for any reason, with no taxes or penalties owed, provided you don���t touch the account���s investment earnings.

5. Automate your investing. Take advantage of the tax-favored savings programs available to you, such as an IRA, Roth IRA and 401(k). Put your savings on autopilot by having your contributions deducted directly from your paycheck or bank account. This is a painless and efficient way to build wealth.

6. Manage your debt load. Many people in their 30s will face critical lifestyle choices that can affect their ability to save money. You might be contemplating buying your first home or purchasing a luxury car. The associated expenses can last for years and even decades.

You need to make sure you can afford these lifestyle decisions. Make sure your total monthly debt payments are 36% or less of your total gross monthly income. Remember, people who are successful in building wealth live well below their means.

7. Don���t look at your portfolio. With any luck, by your 40s, you���re starting to accumulate some serious money. Try not to check your investment performance too frequently. Many investors end up trailing the market because they make too many emotional changes to their portfolio.

8. Play catch-up. Once you turn age 50, the IRS allows you to make additional contributions to your retirement accounts. You can invest an extra $6,000 each year in your 401(k) plan, for a total of $25,000 in 2019. You can also contribute an additional $1,000 a year to your IRA, for a total of $7,000. This is an excellent way to increase your savings rate.

9. Trim taxes. In your 60s, you need to take a closer look at how taxes will affect your retirement income���and especially withdrawals from IRAs and other tax-favored accounts. If you���re in a low tax bracket, this may be the time to convert part of your traditional retirement accounts to a Roth, thereby reducing the taxes you owe once you start required minimum distributions at age 70�� .

10. Delay Social Security. If you���re in good health and can afford to wait, you should defer Social Security until age 70. For instance, if your full Social Security retirement age is 66 and you delay getting your monthly benefit until age 70, it���ll be 32% larger.��A bigger Social Security benefit is the best inflation-adjusted annuity you can buy. It would also help protect you in your later years, when you might be running through your other money.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Not My Priority,��Power of Two��and��California Dreamin’.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Not My Priority,��Power of Two��and��California Dreamin’.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept�� donations, ��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in�� Amazon ‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Building Wealth appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 13, 2019

Missing the Point

IN EARLY MAY, I wrote about 16 ways that people��waste money on everything from tattoos to shoes to children���s toys. That blog was subsequently posted on MarketWatch,��where it collected more than 700 comments, most positive, but many not so much.

I was called out of touch, accused of having an entitlement mentality, talking down to people, privileged and more. I had clearly touched a nerve. Some commenters went into great detail about how difficult their lives were and how there was no money to waste. Others said they worked hard and deserved a vacation. I never said not to take a vacation, just not to go into debt while doing so. Is that unreasonable? One woman took me to task, claiming her children deserved toys. I had noted that U.S. parents, on average, spend $6,500 on toys during a child���s upbringing. Doesn���t that seem even a little excessive?

In short, detailing the ways money is wasted got people���s attention. But many seemed to miss the point���that it���s crucial to live within your means, and that necessitates spending prudently, so you have some savings for financial emergencies and long-term goals.

It���s now clear to me that the way people look at money varies greatly among generations. One commenter said I had a lot of nerve telling people how to spend their money. Hey, I don���t want to dictate how anybody uses his or her money���but I do believe you need to find a way to spend less than your entire paycheck.

In any case, I doubt many millennials would be happy following my example. I���m cheap. But I���m also patient, which means that, at age 75, I���ve reached every financial goal I set when I was 18. Seriously, it���s in my high school yearbook.

The way I see it, younger generations don���t have the same patience. One survey found millennials expected to receive a raise within one year of being on the job. A friend who does hiring for a large financial institution says many of the prospects give off the impression that they���re doing the company a favor by applying for a job, even if they���re just out of college.

Financial prudence isn���t just for the wealthy. In fact, they���re the ones who need it least. And yet my biggest critics seemed to be of average means. They were struggling financially but failed to make the connection between their struggles and their spending. If you can���t convince folks that spending on little things like tattoos, designer coffee and toys all add up, there may be little hope for changing their ways. That raises an important question for society: If we have younger generations who see today���s spending as their top priority, who will support them during their retirement years���or will the whole notion of retirement disappear by necessity?

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include An Old Man’s Gripes,��Money Pit��and��Crying Poverty.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Richard Quinn blogs at QuinnsCommentary.com. Before retiring in 2010, Dick was a compensation and benefits executive. His previous articles include An Old Man’s Gripes,��Money Pit��and��Crying Poverty.��Follow Dick on Twitter��@QuinnsComments.

Do you enjoy��reading the articles by Dick and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a��donation.

The post Missing the Point appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 12, 2019

Living for Less

JIM AND I��GOT married 16 years ago in our modest home. We spent just $500 and only invited immediate family members. Back then, we didn���t have any clue where life would take us. Neither of us planned to retire early, let alone retire abroad.

Still, how we got married was a sign of how we wanted to live���in a financially prudent manner. We set out to keep our living costs under control, and that set us on a path to financial independence, culminating with our retirement last year. In particular, we focused on four key expenses:

1. Debt.��I���ve always disliked being in debt. When we merged our finances, Jim came with credit card debt, while I had an auto loan. We realized it would take many years to pay off the mortgage on the home��we just bought together. We could, however, reduce our other debts.

Since credit cards were the most expensive debt, we aggressively tackled those first. We both had excellent credit scores, so we opened credit card accounts that offered an introductory 0% promo rate, using either my name or Jim���s. We���d transfer old, interest-accruing balances to the new cards and then���before the 0% promo rate ended���transfer the balances again to new cards that offered 0% promo rates. During this time, we lived frugally and managed to pay off the credit cards within a few years. We were also able to pay off my auto loan in two years.

After that, our only debt was the mortgage. We sent in at least one extra payment per year. Based on my calculation, we were on track to pay off the mortgage in 22 years.

2. Transportation.��For most people, their biggest expense���after housing���is their car or cars. Living in Dallas, a city with poor public transportation, we both needed good, reliable cars. We realized early on, however, that we didn���t need the latest model with the flashy gadgets.

For Jim to drive to work and for a general family car, we bought a used Toyota Scion, a small hatchback car with 131,000 miles on it, paying cash. It was big enough to carry most everything, from groceries to camping gear to all the boys��� sports equipment.

Sure, there were occasions we wished we had a big SUV, like many people do in Dallas, especially when we had to strap a 10-foot pole vault to the side of the car to get to competitions. But such occasions were few, and the rare inconveniences were worth it, because we had extra money for other adventures.

3. Cell phones. These have become a necessity for most of us, me included. But why did I need the cell phone? I didn���t use it heavily to do business. I just needed a good reliable phone to keep in touch with family and friends on three continents. With that in mind, I always bought older models, spending less than $300 on each.

When a new model came out, I would ask if I really needed the new features it offered. When the iPhone 6 rolled out, just as I needed to get a new phone because my iPhone 3 was dead, I decided to buy a used iPhone 5s. Today, Jim and I still use the iPhone 5s we each bought many years ago.

A costly phone is a one-time overpayment. But the plan you subscribe to can be an ongoing waste of money. By buying unlocked cell phones for cash, we had the flexibility to change cell plans as often as we liked, because we weren���t locked into a contract.

One of my friends told me she spends over $200 a month on an unlimited cell phone plan for a family of four, which is not��uncommon��in the U.S. This begs the question: Why do you need an unlimited plan? I treat the cell phone like any other utility, such as water, gas or electricity. I would not pay two-to-three times my actual usage per month for ���unlimited��� use of electricity. I pay only for what I consume. Unlimited usage can cost a lot��in the long term, so it���s important to know what you truly need. How many minutes do you actually use for phone calls a month? How many texts do you send and how much data do you need each month?

Another key to saving on cell phones is to use mobile virtual network operators, or��MVNOs. The big networks, like AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile and Sprint, own their own towers. But the smaller ones���the MVNOs���buy service from these big guys in bulk, reselling to consumers at low prices.

Depending on rates and promotions, I would switch our cell phone service among MVNOs, signing up with companies like Mint Mobile, Consumer Cellular, Red Pocket, Ting and Pure TalkUSA. Our last year living in Dallas, we paid $15 a month per line with one of the MVNOs.

4. Utilities.��These can add up, especially if you live in an older home, like we did. I would shop for the best monthly electricity rate���something that���s easy to do in Texas. Using sites like��Compare Power or Power to Choose, I could enter my actual usage and then compare rates.

Last year, at age 53, Jiab Wasserman left her job as a financial analyst at a large bank. She’s now semi-retired. Her previous articles include��Courting Success,��

Buen Camino

��and��

Takes Skill

.

��Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Granada, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement���as well as about their experience relocating to another country���at��

YourThirdLife.com

.

Last year, at age 53, Jiab Wasserman left her job as a financial analyst at a large bank. She’s now semi-retired. Her previous articles include��Courting Success,��

Buen Camino

��and��

Takes Skill

.

��Jiab and her husband Jim, who also writes for HumbleDollar, currently live in Granada, Spain. They blog about downshifting, personal finance and other aspects of retirement���as well as about their experience relocating to another country���at��

YourThirdLife.com

.

Do you enjoy articles by Jiab and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Living for Less appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 11, 2019

Father Knew Best

DAD GAVE ME $1,000 in the mid-1980s on condition I start an IRA and make my own annual contributions, which I did at least some of the time. He recommended doing business with Vanguard Group, which was headquartered near my hometown of Wayne, Pennsylvania.

I can remember reading about the STAR fund, Windsor II, Wellington, Wellesley, the gold and precious metals fund, and the very highly regarded health care and energy funds. I recall the wonderful letters that Vanguard founder Jack Bogle wrote to introduce each annual report.

I invested back then in the STAR Fund and Windsor II, but eventually switched to other funds���probably the sector funds. I was always drawn to investing in something ���real��� like gold and oil. And I began to think the STAR fund���perhaps one of the earliest asset allocation funds���was some kind of odd mishmash.

As the years went by, I was all over the place, moving my IRA to different companies and raiding it (like a fool) at times of financial need. I dabbled in gold and natural gas ETFs and Jim Rogers���s International Commodity Index-Agriculture ETN. (Heck with you, Jim.)

Most critically, I was heavy on the stocks of Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and even Lehman Brothers until the bitter end during the Great Financial Crisis. And yes, despite knowing better���much better���I sold Goldman and Morgan Stanley near the bottom and didn���t catch the eventual recovery.

Recently, I had an idea to write an article titled, ���The trouble with financial advice.��� I wanted to critique the unequivocal asset allocation recommendations of an acclaimed 2005 book. That got me thinking back to the historical performance of simple balanced funds, and how investors who didn���t listen to the author would have fared in some typical fund company offerings.

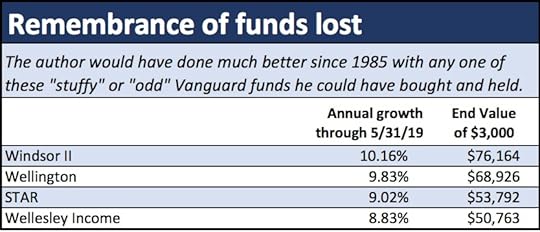

Finally, I looked back to 1985 to see what my results in the STAR and Windsor II funds would have been if I had stopped thinking and just let them ride. The results are sobering: The STAR fund delivered a compound annual growth rate of 9% from Dec. 31, 1985, through May 31 of this year. An initial investment of $3,000 would have become nearly $54,000.

Windsor II���despite a performance shortfall in the 2010s and the departure of longtime manager James Barrow in 2015���grew at a 10.2% annual rate, which would have turned $3,000 into more than $76,000. Wellington, even with its hefty 40% in bonds, grew at 9.8%, for a terminal value of nearly $69,000.

And the Wellesley Income Fund, with about 60% in bonds, would have turned $3,000 into nearly $51,000. Wellesley? Another stuffy Vanguard fund named after the Duke of Wellington? Pfshaw! That���s for grandmothers with antique furniture and a coat of arms.

If only I had acted like my grandmother���who lived on Windsor Avenue in Philadelphia���and invested regularly in one of these funds and held on. If I had virtually ignored the late 1990s boom (when those funds seemed especially old and gray) and the financial crisis, I might be a millionaire by now, or darn close.

I���m embarrassed to say that, to the detriment of my retirement and my children���s ability to pay for college, I am nowhere close to such a fortune. But I am not far from retirement age.

I used to blame Dad for not having more money invested in stocks after he sold his business in the early 1980s, as the great bull market began. How much money could the family have had?

But now, I have only myself to blame.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart

.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart

.

Do you enjoy articles by Bill and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Father Knew Best appeared first on HumbleDollar.