Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 353

September 3, 2019

Life Support

A NEIGHBOR complained to me that his car insurance rates soared after a fender bender. I assumed that he or his wife were involved. But it turned out he was referring to his daughter���s accident. Even though she was 27 years old and had a good paying job, he continued to assume financial responsibility for her car. Is this smart parenting���or does it stymie our children���s transformation into well-rounded adults?

When my friends and I graduated college, most of us had to pay our own bills. But it seems today���s timeline for parental responsibility is being extended by huge student debt, high housing costs and disparity in job opportunities, as well as a trend toward greater parental involvement in our children���s lives.

Studies show that, when young people are starting out, they report high levels of economic stress, especially those with sizable student loans or who are living in communities with exorbitant housing costs. On top of this, nearly half of today���s young adults reportedly face downward mobility, relative to where their parents stand. Understandably, both parents and their offspring find this hard to accept.

Perhaps parents, as well as their adult children, need to modify their expectations. Indeed, this could be a great chance for young adults to develop self-confidence by working through some difficult economic tradeoffs, such as saving money by opting for a less-than-perfect living arrangement or by forgoing an expensive health club.

One option for parents is more targeted financial assistance, with the goal of helping children launch themselves into the adult world.��For example, helping to pay for a smart phone may seem like a luxury, but it���s an essential tool when job hunting.

How much support the parents provide should also vary with the family���s situation. Continuing to pay the bills of adult children can prevent parents from saving for their own retirement. A Bankrate study found that more than half of parents said that assisting their children cut into their own retirement savings. Even if parents can afford to cover living expenses, all this ongoing financial assistance may hamper their children���s development.

How can we best handle all these competing demands? Here are five strategies:

1. Plan. Parents should review their own financial needs. Many people underestimate how much retirement costs. Parents must balance this top priority with their desire to provide family assistance.

2. Discuss. Parents should talk with their adult children about the kids��� finances and plans. Find out what help would be most useful for your 20-something. Provide guidance about budgeting and saving.

3. Target assistance. Offer funds that help young adults gain future independence. Some examples: Assist with housing. Help with college debt. Buy a laptop computer. Pay for health insurance. Buy a car if it���s needed to commute to work.

4. Develop a timeline. Work with your child to decide when to start shifting bill-paying responsibility. Abrupt shifts are difficult to handle for all parties and could come across as a punishment.

5. Provide emotional support. We live in a competitive society. Young adults face numerous financial pressures. Steady reassurance and acceptance by parents can lay a foundation for future resiliency.

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles include Monthly Affliction,��Self-Sabotage��and��Human Factor. Rand

��has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Rand Spero is president of Street Smart Financial, a fee-only financial planning firm in Lexington, Massachusetts. His previous articles include Monthly Affliction,��Self-Sabotage��and��Human Factor. Rand

��has taught personal finance and strategic planning at the Tufts University Osher Institute, Northeastern University’s Graduate School of Management and Massachusetts General Hospital.

Do you enjoy articles by Rand and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Life Support appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 2, 2019

August’s Hits

LAST MONTH saw the second-highest number of page views in HumbleDollar’s 32-month history. Among the new articles published in August, here are the seven that were most widely read:

As the Years Go By

Improving With Age

Not My Guru

Double Checking

Never Mind

Room to Disagree

Think Bigger

Meanwhile, the two most popular newsletters were Whither Vanguard and No Worries. ��But last month’s biggest surprise was Terms of the Trade, a piece by Jim Wasserman devoted to key concepts in the emerging field of media literacy. It appeared in July and, I felt, didn’t get the audience it deserved. That changed in August: Jim’s article was the second most-visited page last month, after the homepage.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Just Asking,��Pay It Down��and Saving Ourselves

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include Just Asking,��Pay It Down��and Saving Ourselves

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post August’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

September 1, 2019

Adding Value

NIKOLA TESLA was a brilliant inventor, with nearly 300 patents to his name. He also had some unique habits. Among them: Every night, before he sat down for dinner, he would ask his waiter for a stack of 18 napkins. He would then use them to carefully wipe down his silverware. Even at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, where Tesla lived for decades and where the silverware was presumably clean, Tesla insisted on this time-consuming process before every meal.

The first napkin, and perhaps the second, might have ensured a somewhat cleaner set of utensils���and it probably gave Tesla, who had contracted a debilitating infection as a child, additional peace of mind. That���s what economists would call��positive��marginal utility. It served some use. But beyond that, it���s hard to imagine that all that additional cleaning and scrubbing contributed much. It just took time. That���s called��negative��marginal utility. It consumed time without adding any value.

When it comes to managing your finances, I suggest looking at things through this same lens. The financial world, unlike more scientific fields, is full of uncertainty. In many situations, additional effort won���t get you any closer to a better answer���just as wiping down the silverware for the 18th time won���t make it any cleaner.

This notion strikes many folks as counterintuitive. When we were children, we were taught to work hard���and indeed, in most endeavors, additional effort does��yield a better result. But in the world of finance, it’s more nuanced.

Historically, when people talked about personal finance, they focused primarily on investment-related questions���which way the market was going, which stocks were hot and so forth. For years, these kinds of questions received the lion���s share of attention from both experts and everyday Americans. But research has shown that time spent on these questions often isn���t time well-spent.��Stock picking,��market timing��and��economic analysis��rarely yield positive returns. What���s worse, these activities also tend to leave investors with higher investment costs and��bigger tax bills.

Don���t get me wrong: A well-constructed portfolio is certainly important and certainly worth your time and effort. I would just be careful not to give your portfolio��too much��attention���especially at the expense of other important financial questions. Below are six topics that I see as a much better use of your time:

Tax planning.��The rules are the rules. But are you doing everything you can to minimize your tax bill within those rules?

Debt management.��Are you managing all of your obligations with an eye to cost, tax-efficiency and peace of mind���especially with the tax rule changes that went into effect last year?

Goal planning.��Are you on track for your own retirement? What about your children���s college��education? If not, how could you get on track?

Estate planning.��If the federal estate tax exemption reverted to its old, lower limit, would this be a problem?

Risk management.��Do you have sufficient disability, life and umbrella liability insurance? Following this decade���s long bull market and the big boost it may have given to your net worth, is it possible that you have too much life and disability insurance���and too little umbrella coverage?

Career management.��In my work as a financial planner, I���ve noticed something surprising: Some employers���even those that appear similar on the surface���offer benefits that can result in vastly different total compensation. This may take the form of supplemental retirement plans, profit sharing programs or equity grants. Result: Some people end up with total compensation that can be 50% or 100% higher���for exactly the same work. Since these incremental dollars are more likely to be saved, the impact on your wealth could be dramatic. This, I think, is something that is underappreciated���and worth paying attention to as you manage your career.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Three Risks,��Room to Disagree��and��Never Mind

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous articles��include Three Risks,��Room to Disagree��and��Never Mind

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

The post Adding Value appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 31, 2019

Just Asking

IT���S THE LABOR DAY weekend, which is hardly the time for a nerdy article on the finer points of personal finance. Instead, I���ll leave you to spend the weekend pondering 11 great unanswered financial questions:

Who does more financial damage, stockbrokers or life insurance agents?

Is taking Social Security early and then assuming you���ll make double-digit gains by investing the money a brilliant strategy���or utterly delusional?

Is a home the best investment you���ll ever make or a money-sucking pile of bricks?

Should you dump that wretched cash-value life insurance policy you were persuaded to buy seven years ago���or hang on in the hope you���ll die young, so you turn a profit?

Does money buy happiness���or don���t you have time to answer, because you���re trying to figure out how to pay the credit card bill?

Are those who try to beat the market ignorant of the evidence or absurdly overconfident about their own abilities?

Are children priceless? Or is that the grandparents talking?

Should you buy long-term-care insurance and trust that the insurance company won���t jack up the premiums on you���or is this another rerun of Charlie Brown, Lucy and the football?

Are index funds truly a threat to the smooth-functioning of the financial markets, or is somebody trying to sell you an overpriced, underperforming actively managed fund?

Is budgeting a sign of financial rectitude���or a last, desperate stab at respectability by those who are financially foolish?

Are everyday investors as stupid as Wall Street claims���or are folks on Wall Street just rude and cravenly self-serving?

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include No Worries,��Pay It Down��and��Saving Ourselves

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter��

@ClementsMoney

��and on

Facebook

.��His most recent articles include No Worries,��Pay It Down��and��Saving Ourselves

. Jonathan’s

��latest books:��From Here to��Financial��Happiness��and How to Think About Money.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Just Asking appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 30, 2019

Quiet Heroism

MY FATHER-IN-LAW��Jim was born in January 1927, the sixth of eight children, to an Irish-American couple in Philadelphia. During the Second World War, his three older brothers were in the armed services. That meant that Jim, barely age 16, had to quit high school and enter the work world, so he could earn an adult���s wage. His salary must have been critical to the family���s economic stability.

Jim���s brother Bill was killed in an accident at sea during ship maintenance in 1944, two months before the D-Day invasion. You can find Bill���s name engraved on one of the plaques in New York City���s Battery Park. But I recently came across a different sort of memorial���a document that tells my father-in-law���s wartime story and the quiet heroism he exhibited.

What document? I discovered Jim���s 1943 federal tax return. Yellowed and old, it���s beautifully handwritten by one of his sisters. His 1040 shows he worked as a truck driver for four different companies and earned $1,705. That would equal some $25,500 in today���s dollars. I hate to think how many hours of work it took.

The 1040 shows Normal Tax at a 6% rate on taxable income. (Taxable income was total income minus a $500 personal exemption, a $157 earned income credit and some deductions.) There was also the Surtax, which was about 9% of total income. Then there was a Victory Tax of 5% on total income, less a $624 exemption. His total tax bill was $235.96, for an effective tax rate of 13.8%. In 2019, the equivalent $25,500 income would have a federal tax bill of $1,402, for a 5.5% effective tax rate.

Jim filed his tax return in March 1944, a few months after he turned 17. A year later, after his 18th��birthday, he enlisted in the Army and served as a buck sergeant in the occupation army in Germany. He was honorably discharged in November 1946.

Like so many in his generation, Jim came home to restart civilian life. He returned to truck driving, married a pretty Italian-American nurse, raised five children and had 11 grandkids. I remember most days he rose at 3 a.m. to get on the road to avoid traffic. His normal work week was 60 hours. A loyal Teamster, Jim drove a truck until 1992, when he retired. He passed away in July 2009. I���ve never met a person who valued family as much as Jim or worked harder to keep the family bonds strong. For more than 35 years, and for so many reasons, I was proud to know Jim and to be his son-in-law. But finding his 1943 tax return, and understanding the quiet heroism behind it, only makes me prouder.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous article for HumbleDollar was Think Bigger. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Richard Connor is��

a semi-retired aerospace engineer with a keen interest in finance.

Rick enjoys a wide variety of other interests, including chasing grandkids, space, sports, travel, winemaking and reading. His previous article for HumbleDollar was Think Bigger. Follow Rick on Twitter��@RConnor609.

Do enjoy articles by Rick and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Quiet Heroism appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 29, 2019

Cost of Living

I TUTOR MY 10-year-old niece once a week in math and science. After the study sessions, we often talk about other things���mostly kid stuff. Recently, her treasured piggybank got a nice boost on her birthday and we discussed what she might do with the money.

That���s when my niece asked, ���How much money will I need when I grow up?��� I guess she was trying to figure out if she did indeed have to study hard and get a job���or whether her current savings would be enough. I laughed and told her that she would definitely need to work, just like the rest of us, because she���d need much more money than her piggybank held.

Still, in retrospect, I think her seemingly innocent question can be a good starting point for introducing teenagers and young adults to the topics of money and careers. As children grow, they generally develop a sense for why money is important���but there���s no easy way for them to gauge how much they need.

A ballpark estimate can give them perspective and help them to double-check whether a career path will meet their financial needs. It can also force them to learn more about basics of smart money decisions. When I started my career, I knew I needed to work hard, earn a decent wage, avoid overspending and save regularly. But beyond those abstract notions, there was no concrete, holistic target in my mind. A rough roadmap���even one with a large margin of error���would���ve helped me to plan and organize my financial life better.

It isn���t too hard to come up with a ballpark estimate. Let���s ignore inflation and instead think about everything in today���s dollars. Let���s also assume a hypothetical couple who start a household at age 30, work for 30 years, raise two kids, retire at 60 and then live another 30 years. Their cumulative lifetime expenses might include the following major items:

Cost of a house. These days, newly constructed homes cost somewhat more than $300,000. Existing homes tend to be less expensive.

Cost of eight cars. Let���s assume both partners have a car, and that each car costs $25,000 and lasts 15 years, for a lifetime total of $200,000.

Annual household expenses for 60 years. The typical household spends around $60,000 a year. Keep in mind that a third of this goes toward housing, plus an additional chunk toward car purchases, so we might reduce this figure to $40,000, or $2.4 million over 60 years.

Cost of two college educations, which we might estimate at $100,000 per kid. If you favor private colleges, you might increase this to $200,000 or more.

Lifetime health care and long-term-care costs. Let���s put that at $300,000.

Once the lifetime lump sum is determined, it���s easy to calculate the required average household annual income: You just divide the lump sum by the number of working years. This annual income represents income after federal and state income taxes, plus payroll taxes during the couple���s working years. You might increase the after-tax sum by 25% to arrive at the required pretax annual household income.

Using the above methodology and the national median household numbers cited above, the lifetime lump sum comes to about $4.25 million in today���s dollar. Over a 30-year working life, that amounts to roughly $70,000 per year per spouse or partner. What are the lessons from this exercise that you might discuss with your kids?

A lot of money is needed over a household���s lifetime. Even the median U.S. standard of living demands a sizable household income.

Everyday expenses���that $40,000 a year���are the biggest driver of lifetime spending. It���s important to avoid overspending and keep recurring expenses in check.

At least a bachelor���s degree is almost essential to affording the lifetime expenses we���re discussing.

Even with a bachelor���s, much depends on career choice.

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investment and financial planning, he’s passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances.��Earlier this year, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate.��

A software engineer by profession, Sanjib Saha is transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investment and financial planning, he’s passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances.��Earlier this year, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate.��

Do you enjoy articles by Sanjib and HumbleDollar’s other contributors? Please support our work with a donation.

The post Cost of Living appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 27, 2019

After You

I HAD AN AUNT who did everything for her husband. She paid the bills, invested their money and oversaw the family budget, plus she did all the household chores.

They both liked this arrangement. It worked for them. But as they grew older, people were concerned about what would happen to Uncle Bob if he outlived my aunt. He depended on her for everything. How could he take care of himself?

My uncle could not operate a washing machine, let alone manage his own finances. Friends had visions of him sitting in his house with no electricity or gas to power his lights and appliances, because he didn���t know enough to pay the utility bills. As it turns out, this never came to pass: My uncle died first.

You might imagine Uncle Bob was an extreme case of helplessness. But there are many Americans who struggle to manage the family���s financial affairs after the death of a spouse. Want to make it easier for your spouse or significant other to take over? Try these 16 steps:

Automate. Have all recurring bills paid automatically. That way, there���ll be no missed payments and all essential services will continue.

Emergency fund. Have a cash emergency fund that���ll cover six months of living expenses. If you���re the primary breadwinner, this would provide your spouse with much needed money for the initial months after your death.

Term life insurance. This offers low-cost financial protection. It���s especially important if you have children still at home.

Fixed costs. If your spouse suddenly has to cope without your income, low fixed monthly expenses will make it easier to meet the family���s financial obligations.

Consolidate. Combine your financial holdings at one or two financial institutions. This will make it easier for your spouse or significant other to locate and manage your assets.

Simplify. Construct an investment portfolio that requires little maintenance���by sticking with a few broad market index funds. Two benefits: There���s no need to make sell decisions on individual stocks and no risk of underperforming the market.

Financial advisor. Hire an advisor to manage your investments. This person could also provide guidance on broader personal finance issues���and assist your spouse in handling the family���s finances, should you die first.

Family. Inform your adult children or other trusted individuals about your finances, so they could then better help your surviving spouse.

Passwords. Tell your spouse where to find the usernames and passwords for all financial websites.

Documents. Make sure insurance policies, deeds, tax returns and all other important financial papers are stored in a safe and easily located place.

Beneficiaries. Review and update all beneficiary designations on retirement accounts and life insurance policies.

Trust and will. Consider having a revocable living trust drawn up, so all assets pass quickly and easily to your significant other after your death. This can also save money by avoiding probate.

Advanced directives. Have in place powers of attorney for health care and financial decisions. These will allow someone to oversee your affairs if you become incapacitated.

Pension. Choose a survivor option for your pension, so payments to your spouse continue after your death.

Social Security. Make sure your spouse qualifies for survivor benefits. You must typically be at least age 60 and married for nine months. Contact the Social Security Administration for further information.

Funeral. Have a conversation with your spouse about what sort of funeral you want. This will avoid overspending at a time when money may be tight.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Improving With Age, Summer School and��.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA. A self-described “humble investor,” he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. His previous articles include Improving With Age, Summer School and��.

��Follow Dennis on Twitter��@DMFrie.

Do you enjoy the articles by Dennis and HumbleDollar’s other writers? Please support our work with a�� donation .

The post After You appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Not My Guru

A LOT OF INVESTORS have spent a lot of time, hope and energy trying to emulate guru portfolios. I���m no different.

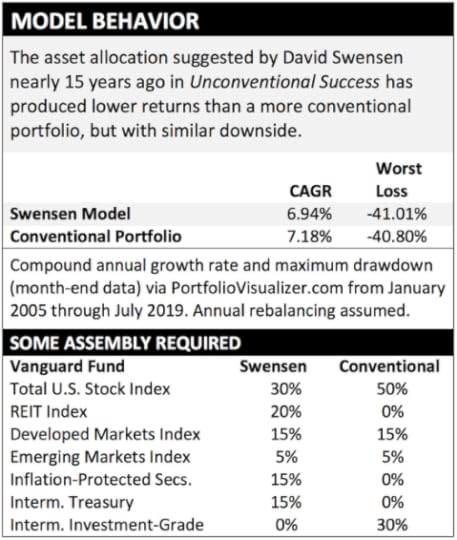

When I read Unconventional Success by Yale University’s chief investment officer,��David Swensen, I felt like The Truth was being revealed. Here was the wisdom of the country’s top endowment manager with, at the time of publication, a benchmark-crushing 20-year record of 16.1% a year. This wasn���t an attention-seeking fund manager or TV host, but a man who didn���t need or even want my investment dollars. He presented his book as a public service.

Swensen was not offering beat-the-market schemes. He advised that ordinary investors use low-cost index funds, such as those run by Vanguard Group, to capture the returns of what he called the six core asset classes.

Note that Swensen���s endowment portfolio doesn���t resemble the model he put forth for ordinary investors in Unconventional Success. Swensen argues that, with greater resources and market clout, institutional investors such as himself can beat the indexes with active management and heavy use of alternative investments. Recently, alas, that hasn���t been the case: According to the latest data available, the Yale University endowment trailed the S&P 500 by a large margin from mid-2008 to mid-2018, reports��Morningstar.

But what about the portfolio that Swensen suggested for everyday investors in Unconventional Success? Since the book���s publication nearly 15 years ago, variations of the Swensen model have been tracked on various websites. Today, it can be found on Portfolio Visualizer (two variations are preset as ���Lazy Portfolios��� in the “backtest portfolio” function), MarketWatch, Portfolio Charts and Bogleheads. Swensen���s portfolio relies on three key rules:

Shun corporate and asset-backed bonds in favor of a fixed-income allocation that is half U.S. Treasurys (15% of the overall portfolio) and half Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, often called TIPS (another 15%).

Avoid putting more than 50% in any one asset class, including stocks, which are divvied up so that 30% of the portfolio is in a U.S. total market index fund, 15% in developed foreign markets and 5% in emerging markets.

Think of real estate investment trusts (REITs) as its own asset class���one distinct from stocks but offering equity-like returns (20% of the portfolio).

The Great Financial Crisis might seem tailor-made to illustrate the benefits of Swensen���s portfolio, with its low-correlated assets. Instead, it���s where the Swensen model disappointed the most. With credit freezing up, REITs got hammered even worse than the overall U.S. stock market. And with deflation fears ascendant, TIPS fell almost as hard as the typical fund comprised mostly of corporate and asset-backed bonds.

To benchmark the Swensen model, I backtested it against a more conventional portfolio. The benchmark I created still uses stock index funds and has the same foreign-stock allocation. But where the Swensen model has 30% U.S. stock market index and 20% REITs, my more conventional portfolio has all 50% in the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund. And instead of 15% in Treasurys and 15% in TIPS, I put 30% in the Vanguard Intermediate-Term Investment Grade Fund. I used the Vanguard Intermediate-Term Treasury Fund in my Swensen model because he didn���t specify a duration in the book.

Treasurys, of course, did their job during the financial crisis, rising as stocks fell. But as a result of the poor performance of TIPS and REITs, the Swensen model lost as much as my conventional alternative from the 2007 peak to the 2009 low. Over the past 15 years, it has also exhibited slightly more volatility���as measured by standard deviation���and downside deviation, based on monthly data from the Portfolio Visualizer site.

I still consider Unconventional Success��essential reading for investors who want to make informed asset allocation decisions. Swensen���s discourses on ���core��� and ���non-core��� asset classes are highly instructive, even if his outright rejection of asset-backed, investment-grade corporate and high-yield bonds seems overwrought.

Looking at the last 15 years, the Swensen model���s relatively light exposure to foreign stocks looks smart. He had foreign stocks at 20% of the overall portfolio and 29% of the stock portion. Some asset allocators say U.S. investors should own foreign stocks in proportion to their weight in global stock indexes, which today means having almost half your stock portfolio invested abroad. Swensen, however, wasn���t predicting that foreign stocks would lag. In fact, he said the expected returns of U.S. and foreign stocks were identical. Rather, he felt investors needn���t take on more foreign currency risk.

Undoubtedly, there will be market environments where the Swensen model outperforms, and perhaps such a period is upon us. Excesses are evident in the corporate bond market, making it vulnerable to a selloff, and future inflation could surprise on the upside, finally rewarding TIPS investors. REITs, meanwhile, have handily beaten the overall U.S. stock market since the financial crisis.

The lesson here isn���t that David Swensen is or was wrong. So what is the moral of the story? Conventional wisdom isn���t always mistaken and it���s folly to slavishly imitate the master investors. Instead, we need to master our own worst impulses���one of which is to rejigger our portfolios every time the gurus speak.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill’s previous articles for HumbleDollar were China Syndrome,��Before the Fall��and��No A for Effort. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart

.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. Bill’s previous articles for HumbleDollar were China Syndrome,��Before the Fall��and��No A for Effort. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart

.

HumbleDollar makes money in three ways: We accept��donations,��run advertisements served up by Google AdSense and participate in��Amazon‘s Associates Program, an affiliate marketing program. If you click on this site’s Amazon links and purchase books or other merchandise, you don’t pay anything extra, but we make a little money.

The post Not My Guru appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 26, 2019

When Brokers Fail

A RECENT ARTICLE by HumbleDollar���s fearless editor got me thinking about the potential risk of having most or all of my investments with a single brokerage firm or fund company. What happens if the company collapses? I was surprised at how little I knew about these matters after investing for nearly 30 years.

The Securities Investor Protection Act of 1970 was passed by Congress in response to some turbulence in the markets that caused a number of brokerage firms to fail. The law created the nonprofit Securities Investor Protection Corp., or SIPC. The SEC requires effectively all U.S. brokerage firms to be members. SIPC has the narrowly-defined task of assuring the return of investors��� securities and cash in the event of a member firm���s closure or bankruptcy. It does not protect against market losses.

If you invest with an SIPC member broker, and��that broker is liquidated by SIPC, and��some of your assets come up missing, SIPC will restore the missing assets from your account up to $500,000, unless it���s cash investments, in which case coverage is capped at $250,000. This coverage applies after any assets are recovered during the company���s liquidation, so potentially you���ll be made whole, even if you have far more than $500,000 at a brokerage firm that fails.

The liquidation process involves the appointment of a trustee for the broker, who tries to quickly determine the status of customer assets. If the assets are properly accounted for, the trustee may simply transfer the assets to another broker, after which customer control of the assets resumes.

SIPC coverage of multiple accounts with a single owner is determined by what is called “separate capacity,” so total coverage may exceed the $500,000 threshold. A detailed explanation of capacity can be found here.

In theory, the need for SIPC coverage is vanishingly small, because the SEC forbids the comingling of broker assets and investor assets. Thus, even if a broker goes���ahem���broke, investor assets should remain in trust. Only when the failing firm has caused a loss of investor assets is SIPC protection invoked. If your losses exceed the coverage offered by SIPC, there may be additional coverage through a private insurer, assuming the broker had elected to purchase it.

Historically, it���s very rare for losses to exceed the coverage limit. But in 2018, SIPC was still cleaning up the carnage involved with names like Lehman and Madoff. Still, most cases are settled within three months. You aren���t covered for market losses that occur while things are being sorted out.

How can you minimize the risk of loss stemming from your broker���s financial condition? Six action items come to mind:

Determine your broker���s membership in SIPC here. Use caution, as some well-known investment firms hold assets in distinct business entities. For example, assets held with Vanguard Brokerage Services are protected by SIPC, but funds held by The Vanguard Group, Inc. are not.

Make sure you���re receiving transaction confirmations and statements regularly. Review them for accuracy. The sooner you respond to a mistake, the easier it is to fix. This might seem like it hardly needs to be said. But I���for one���am guilty of throwing most correspondence into a pile or folder, without ever reviewing it.

If you find a suspected error in any related correspondence, immediately notify your brokerage firm in writing. If you fail to do this, your SIPC protection may be limited.

Similarly, notify your brokerage firm in writing if you do not receive an expected statement or confirmation.

Keep copies of all correspondence with your brokerage firm. You���ll need to provide reasonable proof of your loss during liquidation.

Pray to all that is holy that you never need any of the preceding information.

When not paddling, biking or shooting, Phil Dawson provides technical services for a global auto manufacturer. He, his sweetheart Donna and their four extraordinary daughters live in and around Jarrettsville, Maryland.��His previous articles include Financially Fit,��Fighting for Peace��and��Taking Care

.��You can contact Phil via

LinkedIn

.

When not paddling, biking or shooting, Phil Dawson provides technical services for a global auto manufacturer. He, his sweetheart Donna and their four extraordinary daughters live in and around Jarrettsville, Maryland.��His previous articles include Financially Fit,��Fighting for Peace��and��Taking Care

.��You can contact Phil via

LinkedIn

.

The post When Brokers Fail appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 25, 2019

Three Risks

ON DEC. 17, 2002, Harry Markopolos walked out of his Boston office wearing an oversized trench coat and a pair of white cotton gloves. His destination: the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.��

A quiet figure, Markopolos worked as the chief investment officer at a small firm that specialized in trading stock options. He had heard about a New York-based competitor that was apparently doing similar work, but with much greater success. Following his boss���s recommendation, Markopolos tried one day to replicate his competitor���s strategy. But when he did, a funny thing happened. He realized that he couldn���t���not because he wasn���t capable, but because it simply wasn’t possible.

As Markopolos tells the story, it was just five minutes before he began to suspect something fishy about the New York firm���s numbers. By the end of day, with just a little more work, he was sure of it. So sure, in fact, that Markopolos decided to alert the authorities.

Markopolos prepared a detailed written report. His objective that December day: to hand deliver it, anonymously, to the New York State Attorney General, who happened to be speaking at the Kennedy Library.

Markopolos���s analysis was dense, packed with math. But the bottom line was clear: It was mathematically impossible for the New York firm to be doing what it claimed to be doing. If that was the case, the only alternative was that the firm���Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities���was a giant fraud, running the world���s largest Ponzi scheme.

In Markopolos���s words, he ���gift wrapped” the Madoff case for the government. In addition to the New York Attorney General, Markopolos also contacted the SEC. Yet none of these regulators took any action. Madoff was able to continue his fraud for another six years before it finally unraveled.

Markopolos was recently in the news again���this time with fraud accusations against General Electric. On a newly launched��website, Markopolos argues that, ���GE Is Headed Toward Bankruptcy.���

Economist Elroy Dimson once defined risk this way: ���More things can happen than will happen.��� The world is an uncertain place. Some things are easy to predict, but most aren���t. Sometimes, there are warning signs���such as Markopolos���s repeated attempts to get regulators��� attention. But sometimes���maybe most of the time���there are no warning signs at all.

Moreover, even when there are signs, they���re never easy to interpret. Consider GE. When Markopolos published his report, the stock dropped more than 10%. But the next day, it made up most of that lost ground. What should we make of that? Are we ignoring Markopolos again at our peril? Or is it possible that he���s wrong this time? The investment world can be a confusing place���and often only makes sense when we look back months or even years later.

So how can you protect yourself? Financial risk, in my view, fits into three categories. If you���re feeling rattled by recent events, I���d recommend taking your portfolio and ���auditing��� it for all three risks:

1. Overall market risk.��Since 1997, the U.S. stock market has doubled in value twice, quadrupled in value once and gotten cut in half twice. Where it goes next, no one can say. Fortunately, the solution to this risk is relatively easy: appropriate asset allocation.

2. Individual investment risk.��Sometimes, you can spot a risky investment from a mile away, but it’s rarely that easy. Investments are more like Rorschach tests. For any given investment, you could highlight the risks or you could highlight the opportunities, depending on whether you���re predisposed to like the investment or not.

Consider Tesla. Its CEO is a genius, often compared to Thomas Edison. But he���s also demonstrated erratic��behavior��and been in trouble with��regulators.

Sometimes, new risks materialize out of the blue, as they did with GE. Fortunately, the solution to this risk is also straightforward: diversification. Keep your bets small so you can���t lose too much the next time Harry Markopolos puts on his trench coat and white gloves.

3. Fraud risk.��The last category of risk might seem like the hardest to protect against. But in my view, it���s the easiest. For the bulk of your investments, avoid anything that looks esoteric and steer clear of private investment funds. Invest only in things that are straightforward and that have publicly listed, easily ascertained prices. And be sure your assets are held by a large, well-known custodian���a firm like Fidelity Investments or Charles Schwab. This was the huge��red flag��with Madoff���and you didn���t need a degree in advanced mathematics to see it.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous pieces��include Room to Disagree,��Never Mind��and Double Checking

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

Adam M. Grossman���s previous pieces��include Room to Disagree,��Never Mind��and Double Checking

. Adam is the founder of��

Mayport Wealth Management

, a fixed-fee financial planning firm in Boston. He���s an advocate of evidence-based investing and is on a mission to lower the cost of investment advice for consumers. Follow Adam on Twitter��

@AdamMGrossman

.

The post Three Risks appeared first on HumbleDollar.