Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 199

July 19, 2022

Finally in Charge

I WAS A CAREFREE��girl who grew up on a farm in Washington state. There never seemed to be any money worries. I had the freedom to roam 2,000 acres on my motorbike. The woods were my sanctuary. My father had a plane and landing strip in the field next to our house. I was the baby of the family and he was very generous with me. My mother was hard working and believed everything should be earned. She taught me about gardening and about being frugal and resourceful.

I was naturally industrious. In third grade, I was reprimanded for selling plastic molded creepy crawlers, along with fun flowers I���d made, to my fellow schoolmates. I babysat and sold greeting cards around the neighborhood, and started working in a card shop as soon as I could drive.

My education was funded by my parents, but I helped out by working in a bakery while at college. I had my nursing degree by the time I turned age 21. I didn���t know if I���d like nursing, but I figured I could start making money and then map my life out from there. I have always loved the art of negotiation. While in college, I talked my parents into funding a trip to Hawaii. I was able to pay them back quickly because, while home for the summer, I worked at the local hospital.

Surrendering control. When I was age 14, my dangerously rebellious 15-year-old sister had a religious conversion and turned her life around overnight. This seemed so miraculous that I immediately joined the same extremely conservative Christian group, believing it was God���s only true way. It changed my thinking in every way. I no longer trusted my intuition or felt I had a choice, but instead submitted to external authorities, taking guidance from them.

After graduation, I married an unemployed laborer who appeared to convert to my faith. I believed that it was shallow to consider his wild history or employment status to be a red flag. ���My love and my job will save him,��� I told myself. ��Often, it isn���t until many years later that we clearly see the underlying motivations for the choices we make, as well as the folly of our reasoning.

Together, we made financial mistakes such as buying whole-life insurance from my husband���s friend, including policies for the kids, and paying large fees at brokerage firms. We also, against my will, helped support my husband���s parents. His father had a gambling problem, as well as a penchant for various get-rich real estate schemes.

We ended up buying numerous properties from my father-in-law, first 10 acres, then another 10, then their home. We rented out their house, while they moved into a mobile home on our property. Subsequently, we moved into my in-laws��� house and rented out ours, and my in-laws moved in with us. We built several more homes for them and helped support them until they died.

All this led to many real estate deals. My husband had the vision and knowledge. I controlled the budget. I made sure we lived beneath our means and insisted we pay off our bills as rapidly as possible. I was working two jobs. Sometimes, my whole paycheck would go to support my in-laws. I was determined that we would be financially responsible, never finding ourselves dependent on others. We subdivided the land we owned and sold the various parcels. We were able to come out ahead, even after numerous legal disputes.

Along the way, I was furious to learn about the high cost of mortgage borrowing���not something I���d been exposed to growing up. I negotiated with my parents once again, asking to borrow from them. In return, I offered them a higher interest rate than they were getting on their Treasury notes but less than the double-digit rates we were paying on our two home loans. We refinanced with them and thereafter paid extra on the loan every month. By the time I was age 40, we were completely debt-free.

At around age 50, I came to my senses and realized I���d been submitting myself to something that was not, as I had believed, the absolute truth. I had a choice. This meant leaving behind the support network that the church had offered. A few years later, in 2010, my husband and I divorced.

Feeling emotionally insecure, I worked obsessively for a few years, not knowing what to do with an empty nest and no husband. From the divorce settlement, I received two properties, which I sold. One was a development we had started. The other was a condo. In both cases, the parties decided they didn���t need to follow through on the contract they���d signed. I had to hire legal help to get paid.

In 2013, I met the man of my dreams���it is possible���and we quickly married. We were both clear on what we wanted and didn���t want in a relationship. He had three daughters. I had three sons. We both had similar histories. At one point, we had even worked at the same hospital, but we never met. I bought a house, he and his youngest daughter moved in, and we both rented our previous homes. As much as I had reined in my spending when I got divorced, he wanted to live large. We���ve compromised, negotiating what���s most important to each of us.

Expensive advice. In 2016, we were wooed by a financial planner, who promised to help us coordinate our retirement and tax planning. We transferred $1 million from our brokerage accounts to his firm. In the past, I���d been frustrated with financial advisors telling me to get advice from a CPA, while the CPA told me to get advice from my financial planner. This new planner���s holistic approach was appealing.

I read the book he���d written, and asked him many questions and got satisfactory answers. But he blatantly lied. The planner appealed to our desire for safety, outlining how we could retire immediately with an attractive income. But we ended up with a majority of our money in illiquid, non-publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs), with the rest in a deferred annuity and mutual funds with very high fees.

I liked the idea of the non-publicly traded REITs. I thought it would be great to have rental properties that delivered income every month, without the hassles of being a landlord, so I was okay with the illiquidity, as long as the investments were producing income. But at this juncture, the REITs have mostly stopped paying income and their values are down. The income was not a 6% to 8% return, as projected, and the payments seem to have come at the expense of our principal.

The planner soon told us that the fiduciary laws were changing, which required him to charge a 1.5% annual management fee, over and above the mutual fund fees. By then, I was on to him. I moved the mutual funds to another brokerage firm. I also sued. We���ve recovered only a fraction of what we invested. The REIT money is tied up indefinitely, still incurring fees. I kept the annuity. It���s with a reputable company, but I probably wouldn���t make the same choice again.

��I shudder to think of all the others who staked their retirement on his advice and didn���t have a backup plan. Many filed grievances against him. He got off by retiring. The securities firm he worked with took the hit.

Because of all these experiences, I���m now highly suspicious of authority figures. I no longer passively assume others have my best interest at heart. Instead, I���ve tried to educate myself on financial matters���and negotiate better terms when I can.

Testing retirement. In 2017, my husband and I took off most of the year to travel and play. I was pleasantly surprised by how much we saved in federal income taxes during that year and that, even as we spent, our net worth didn���t go down. It gave us a taste for retirement. Now, we often travel internationally, while working far less than before.

We���ve also been preparing our finances for the day when we no longer have any earned income. I love mentoring younger nurses, both in nursing and in the basics of finance, and I plan to continue doing so for as long as I enjoy it. I also continue to contribute the maximum allowed to my 403(b) account. A few years ago, my employer started offering a Roth option in the 403(b). I now direct my income there first, with the goal of maximizing my contributions each year, while living off the savings in our taxable account. I no longer contribute to my traditional IRA. I would rather pay the tax now than worry about what my tax bill might be when I have to start taking required minimum distributions.

In recent years, a big challenge for my husband and me has been health insurance. We no longer work enough to qualify for employer-sponsored care. I turned age 65 last year, so I now have Medicare coverage. But my husband, who is younger, is getting by for a few more years with an inexpensive health share program. It���s a catastrophic coverage plan with a high deductible, which can work well, provided you���re healthy. We could limit our income and qualify for government tax subsidies. But if we did that, I couldn���t continue with my aggressive annual Roth conversions. Our plan is to keep our income just below the IRMAA limits that would raise my Medicare premiums.

Over the past few years, I���ve been studying investing and preparing for retirement, and I find it relaxing. I have various people I go to for advice, while maintaining my need to make final decisions on my own and with an eye to keeping things simple. I���ve always had a fairly high tolerance for risk. But now, with recent market losses, I���m trying to navigate this last stretch in the workforce. We���re switching our investment focus more toward portfolio preservation than growth.

I realize I���ve been lucky in countless ways. We���ve set aside five years of income in certificates of deposit and Treasury bills, all held in our taxable account, which we can access as desired. At age 70, we���ll claim Social Security and start annuity payments, which will be supplemented by our IRA funds and what remains in our taxable account. We hope to have money left over for our children. But our first priority is to make sure we can take care of ourselves, even if we live to a ripe old age.

My husband and I often reflect on a paraphrased quote from the Italian movie, The Great Beauty, ���There came a time in life where I stopped doing what I don���t want to do.��� Although it was profitable to be landlords, it was also hugely stressful. We don���t want to be landlords anymore and we don���t want more lawsuits. During COVID-19, to get nonpaying tenants out of our last rental property, we downsized and moved into the property ourselves. It���s a low-maintenance, minimal expense oasis for us, one that serves as a home base between adventures. We have a huge garden, water barrels and a greenhouse, and soon we���ll add chickens, so we can be more self-sufficient. We share the produce with neighbors, who help maintain things when we���re gone.

As I write this, I���m on a plane home from Paris. I smile, feeling I���ve finally found a good balance between enjoying the now and planning for the future.

Marla McCune is a registered nurse with a career spanning 45 years. She also loves journaling and outdoor activities, including swimming, photography and gardening.

Marla McCune is a registered nurse with a career spanning 45 years. She also loves journaling and outdoor activities, including swimming, photography and gardening.

The post Finally in Charge appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Keep the Faith

INDEXING IS A GREAT strategy���and yet there���s also a constant temptation to stray.

When stocks soar, so does our self-confidence, as we attribute our investment gains to our own brilliance. At such times, there���s a risk that even hardcore indexers will start dabbling in individual stocks, actively managed funds, cryptocurrencies and goodness knows what else. Meanwhile, amid market slumps, index funds suffer just as much as the market averages, and some indexers may look to sidestep the pain���by "temporarily" abandoning their funds.

Tempted to give up on or lighten up on��broad market index funds? Let���s not forget the virtues of what we already own. Here are six reasons to stay the course:

1. Less time. Other than adding new savings and rebalancing occasionally, a portfolio of broad market index funds involves very little upkeep. That frees up time to focus on improving other areas of our financial life, including reducing taxes, minimizing borrowing costs, planning our estate, getting the right insurance and spending thoughtfully. These are all areas where a little effort can deliver big benefits.

2. Less worry. Sure, with an index-fund portfolio, we���re at the mercy of the financial markets. But at least we don���t have to worry about whether the investments we pick will underperform the market averages. Index funds offer relative certainty: Whatever the markets deliver, we indexers know that���s what we���ll get.

3. Tax efficiency.��Pursuing active investment strategies in a regular taxable account often leads to big tax bills. That isn���t something indexers need to worry about, because broad market index funds have tiny portfolio turnover, which means they���re slow to realize capital gains. Because of the way shares are created and redeemed, exchange-traded index funds can be especially tax-efficient.

4. Lower costs. Investors collectively earn the markets��� results���before investment expenses. After costs, they inevitably earn less.

Index funds get their edge by mimicking the market averages while minimizing costs. What about active investors? Whether they���re picking individual stocks or buying actively managed funds, the odds are they���ll end up��lagging behind the market averages, thanks to the higher costs they incur.

5. Winners included. Almost every year, the market averages are skewed higher���or prevented from falling even more steeply���by a minority of stocks with huge gains. If we try to pick the big winners, we���ll most likely fail. If we buy broad market index funds, we���re guaranteed to own them.

6. Free ride. The financial talking heads���who are almost always proponents of active management���will claim that index funds are distorting market prices or are dangerously overweighted in certain stocks. But the fact is, if we own market-capitalization-weighted index funds, we own exactly the same stocks that active investors collectively own in exactly the same proportions.

The only difference: We didn���t waste time and money trying to figure out which stocks were the best value. Plenty of others remain happy to do so, and we thank them for sacrificing their time and money to keep the markets��efficient.

The post Keep the Faith appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Penniless at Last

IN AN EARLIER ARTICLE, I noted that my savings journey began in 1960 with a couple of jars of pennies that I started collecting at age five. I was following family ancestor Ben Franklin���s maxim that ���a penny saved is a penny earned.���

One of my uncles also had an interest in coin collecting. He and I began to actively search through countless penny rolls to find pennies with dates that we didn���t have. We bought Whitman��coin albums and organized our pennies by date from the earliest Lincoln head pennies from 1909 up through the 1960s.

We expanded our collection to include sets of Buffalo and Jefferson nickels, Mercury and Roosevelt dimes, and Washington silver quarters, plus any older coin we happened upon. Occasionally, we found Indian head pennies, Liberty nickels, Barber dimes or Walking Liberty quarters still in circulation. These dimes and quarters contained 90% silver through 1964, so they had a recognized commodity value.

Our coin-collecting hobby lasted for eight years. During those eight years, we amassed five nearly complete Lincoln penny sets, missing only the rare 1909 penny minted in San Francisco with the initials V.B.D. for its engraver. One of these pennies in fine condition can cost more than $1,000.

We had jars of old duplicate pennies as well. We assembled a couple of complete sets of Jefferson nickels and Roosevelt dimes. Our most valuable collection was the three nearly complete sets of Mercury dimes, lacking only a rare 1916 10-cent piece minted in Denver. We accumulated plenty of duplicate year silver coins as well.

My uncle passed away in 1968 due to complications from polio, and my interests shifted. That���s when my coin collection went into hibernation, stored in various basements untouched for 50 years.

I have no interest in pursuing this hobby today, and neither do my kids. To clean up my estate, as I suggested in another article and on this blog site, I started to sell my coin collection a couple of years ago.

Monetizing a haphazard coin collection is not a simple process. The coins have different values to different buyers. The Lincoln pennies and Mercury dimes had more value sold as a set to collectors. My bulk coins frequently didn���t have much numismatic premium over their silver or copper melt value.

I sold the rarer loose coins at a premium over the web. The remaining bulk coins went to a local coin dealer at commodity values. Bulk coins are heavy, making them too expensive to ship to anyone willing to pay a slight premium.

These coin sales took me several years to complete. How did I do over my 55-year holding period? Okay, but not great.

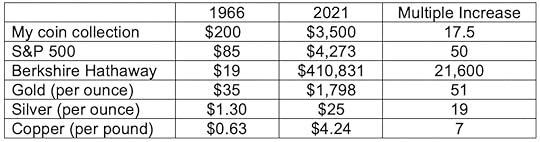

After tons of work, plus some costs, I ended up grossing about $3,500. I don���t know exactly how much my uncle and I spent buying these coins back in the 1960s. We acquired the vast majority of the coins for their original face value. I���m guessing the whole collection cost $200 and certainly not more than $300, because we couldn���t afford much at the time.

At best, this translates to a total gain of 17.5 times the original investment. That���s roughly equivalent to the appreciation of silver since 1966. I made far more from the silver coins than I did from the nickels or copper pennies.

By comparison, the S&P 500 and gold prices have risen 50-fold over the same period. Berkshire Hathaway stock appreciated more than 21,000 times.

One clear takeaway: Only collect things for personal enjoyment rather than as an investment. Another is that the sale of a long-term collection can be annoyingly time-consuming. You can see this for yourself by watching the TV show American Pickers. They regularly demonstrate how hard it can be to monetize collections, even when the collections have solid value.

John��Yeigh��is an author, speaker, coach, youth sports advocate and businessman with more than 30 years of publishing experience in the sports, finance and scientific fields. His book "Win the Youth Sports Game" was published in 2021. John retired in 2017 from the oil industry, where he negotiated financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. Check out his earlier articles.

John��Yeigh��is an author, speaker, coach, youth sports advocate and businessman with more than 30 years of publishing experience in the sports, finance and scientific fields. His book "Win the Youth Sports Game" was published in 2021. John retired in 2017 from the oil industry, where he negotiated financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. Check out his earlier articles.The post Penniless at Last appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 18, 2022

Tail Wagging

A POPULAR REFRAIN is that we shouldn���t let the tax tail wag the investment dog. I struggle with this one.

Currently, 87% of our stock portfolio is in broad-based, low-cost index mutual funds, with the other 13% in individual stocks. I prefer the index funds���and yet I continue to hold the individual stocks because I don���t want to pay the taxes on our gains.

About 6.7% of our total stock portfolio, equal to half our money in individual stocks, is in my former employer���s shares, which I received as part of my compensation. Over the years, I���ve worked diligently to keep our holdings below 10%.

Our next largest individual holding is Target Corp., at about 2.8%. When my wife picked me up from work on Oct. 19, 1987, all of the news was about the stock market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had crashed 22.6%. On the drive home, I asked my wife what she thought we should do. She promptly replied, ���Buy Dayton Hudson.���

Dayton Hudson was our local department store. Its major division was its Target discount stores. Being a young couple, we shopped at Target, so the next day I bought 100 shares of Dayton Hudson. The department stores are long gone, but Target lives on.

Between our initial purchase and reinvested dividends, our cost basis is now $13.80 a share. Yesterday's closing price was $149.36 (symbol: TGT), almost an 11-fold increase. Although I���d like to unload the stock and put the money in an index fund, the thought of paying the taxes���even at the long-term capital gains rate���has kept us from selling.

Our third largest holding is McDonald���s, representing about 2.5% of our portfolio. In late 1981, I bought a single share of McDonald���s and enrolled in its dividend reinvestment plan. That gave me the ability not only to reinvest the dividends in additional shares, but also to send McDonald���s money to buy more stock. For many years, I purchased $50 of McDonald���s stock every quarter. As my salary grew, the amount I invested also grew, eventually reaching $150 a quarter. Our cost basis today is the equivalent of $51.80 a share. Yesterday's close was $252.42 (MCD), almost a fivefold increase. Again, I have a hard time selling the shares and paying the long-term capital gains taxes.

We own three other individual stocks, each less than 1% of our assets, but each showing nice gains. So, what am I doing?

I sold some of my employer���s shares that were showing a loss. I also sold all of our Novartis stock, which had ���only��� doubled in price. The loss offset the gains, so the trades didn���t increase our tax bill. I���ll use the proceeds from the sales to buy more of our index funds.��That���s a small step toward eliminating the individual stocks in our portfolio.

I���m not sure that I���ll ever sell the Target and McDonald���s shares, and trigger long-term capital gains taxes. My plan right now is to die holding them, and let my children inherit them at a stepped-up basis. They can then sell them and invest the proceeds in a well-diversified portfolio.

The post Tail Wagging appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Grateful Debt

THE AGE-OLD DEBATE about not borrowing to buy depreciating assets came up again in a recent HumbleDollar article. Despite being a big proponent of debt-free living, I could relate to the story of borrowing to buy a car. In fact, I���m guilty of having gone deeply into debt in my younger days to feed my passion for music���and I don���t regret it.

I grew up listening to Indian music of various genres, but it wasn���t until my college days that I came to really appreciate the sound quality and texture of music. Our dorm had a high-fidelity stereo, plus a decent collection of vinyl records and audio cassettes. I���d spend hours in the common room, listening to classic rock or favorite Bollywood��film scores.

My newfound love of music, alas, came to an end after I left college and moved back home to Kolkata. We had a portable radio and cassette player in our house, but it didn���t satisfy my craving for quality sound. My life felt so incomplete without a good audio system that I decided to buy one once my paychecks started coming in.

I grabbed a coworker named Natesh, who shared my love for music, and we visited an upscale audio showroom near our office. Luckily, the store stocked a nearly identical sound system to the one in my dorm.

It was a top-of-the-line modular audio system named Uranus 2 by Sonodyne, one of the most innovative stereo makers in India. I instantly fell in love with the set and wanted to take it home.

There was just one small problem. I couldn���t afford it.

In the late 1980s, premium audio products weren���t cheap in India. The model I wanted would cost almost a year of my take-home pay. That helped explain why the salesperson didn���t take us youngsters to be serious buyers when we browsed the audio store.

Watching our reaction to the price tag, he politely suggested other, more affordable brands. I wasn���t interested. After all, what���s the point of grinding through years of schooling if I couldn���t afford a music player of my liking?

The next day, I was sharing my disappointment with my other coworkers. Natesh pulled me aside for a quick chat. Apparently, he���d been saving for a couple of years but didn���t have any immediate spending goal. He wanted to lend me the money, interest-free, so I could buy the stereo.

I was surprised by his unbelievable generosity, but his reasoning was simple. He���d be genuinely happy if his savings could make a difference to a close friend. In our early 20s, mutual trust and support between friends was a given. I gladly took him up on his offer.

A day or two later, we proudly walked back into the showroom with crisp 100-rupee notes, which Natesh had withdrawn from his bank earlier that morning. We hurriedly purchased the stereo and loaded up the boxes in a cab. Natesh accompanied me home to help set it up. My small room soon filled with the sound of Pink Floyd, and my goosebumps came back.

That music system remained my most prized possession till the day I left India for overseas work. I not only enjoyed waking up to the songs of the Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel, but I also felt joyful whenever my music buddies dropped by to listen to our favorite songs together. I started dubbing song collections on blank cassettes to give away as gifts.

My parents, on the other hand, weren���t exactly thrilled with my purchase. The set was bulky and loud���clearly a misfit in our modest two-bedroom apartment in a middle-class neighborhood. My dad, who was only used to mono sound, suggested that I get rid of one of the speakers to declutter my room. My mom reminded me of the perils of extravagant and irresponsible spending. Extravagant? Without a doubt. Irresponsible? I���m not so sure.

To be clear, behind all my excitement, I was feeling slightly guilty. I wondered if I���d been too selfish in buying something that no one else in my family seemed to enjoy. My parents took pride in living within their means. Borrowing money for lifestyle improvement was, in our family, seen as almost immoral. My purchase felt like I had committed financial infidelity.

But was it really such a sin? I had no debt or serious financial obligations. As a 22-year-old living in his parents��� home, my only immediate financial goal was to save money for an inverter��power generator to deal with the frequent electricity blackouts. Since Natesh, my godsend lender, said he didn���t need his money back anytime soon, I could save up to buy the generator in a few months, as I'd originally planned, and��have the sound system as well.��It came down to a choice between buying the stereo system now with borrowed money versus waiting for a couple of years and saving up the cash. Thanks to a steady income and the offer of an interest-free loan, I chose to borrow money to buy the sound system.

A surprise awaited me later that year. Employees of our company were overdue for a pay increase, but it was stuck in bureaucratic red tape. After a long wait, the powers that be approved our pay hike with retroactive effect. I received a nice salary bump, plus a lump sum bonus to cover the arrears. I paid Natesh off much sooner than I���d expected. Life took us to different parts of the world and we lost touch, but I���m forever indebted for his unconditional generosity and friendship.

Fast forward 33 years. I can now easily afford a premium home audio system, thanks to the declining price of electronics and my improved financial condition. But I don���t feel the same urge anymore. It isn���t because I lost my passion for music. Rather, it���s because my hearing has degraded over the years.

Hi-fi music isn���t quite the same through hearing aids. I miss the joy of listening to crisp, quality music so much that I���m glad I indulged myself long ago���and violated the personal finance mantra about never going into debt to buy a depreciating asset.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is��passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is��passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.The post Grateful Debt appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 17, 2022

Downgrade This

THE RESEARCH TEAM at Bank of America put out a pair of seemingly contradictory investment notes last week. On the bullish side, the folks there pointed to extremely cheap valuations in the small-cap space. But a few days later, the economics department rocked Wall Street with a bearish forecast calling for five consecutive quarters of negative real U.S. GDP growth.

I chuckled at the sequencing: It's often said the stock market leads the economy by about six months, give or take. Perhaps that���s no better seen than in these two research pieces. Consider that stocks���big and small, domestic and foreign���are all down bigtime so far in 2022, and yet it���s only now that we begin to hear economic downgrades from Wall Street research outfits, along with analysts lowering their year-end stock price targets.

Rarely is it the case that the professional analysts at large research firms accurately get ahead of major market moves. To me, these pessimistic outlooks should make investors more sanguine about stocks. Maybe downbeat prognostications from the pros are just what���s needed to set up the next bull market. We already see incredibly sour sentiment from investors, corporate executives, small business owners and consumers. Low valuations, analyst downgrades and general despondency are characteristics of buying opportunities, not a time to hide out in cash.

It's hard not to be upbeat about the future���assuming you have a time horizon that stretches beyond the next few months. History tells us that returns are, on average, robust after a dismal six-month stretch like we���ve just endured, according to data gathered by Charlie Bilello. While everyone else shudders when they peek at their account balances, now might be the time to ramp up your monthly contributions to your low-cost stock index funds.

The post Downgrade This appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Nine Key Questions

I RECEIVED A CALL last week from a college student who���d started a successful business. His school, he said, didn���t offer any practical courses in personal finance, so he asked my advice on investing.

We walked through nine key questions. I would offer the same advice to investors of any age.

1. Why should I expect stocks to go up?��One way to answer this question would be to invoke the oft-quoted phrase that ���history doesn���t repeat itself but it often rhymes.��� Stocks have delivered roughly 10% returns per year since reliable recordkeeping began in the 1920s. You could extrapolate that long-term average into the future. But that still wouldn't address��why��we should expect stock prices to rise.

To answer that question, the best resource is��Stocks for the Long Run��by University of Pennsylvania finance professor Jeremy Siegel. The book includes a useful mix of market history and finance theory. If I were teaching an investments 101 class, this is the book I���d use.

Notably, Siegel was able to piece together market data going all the way back to 1802. His finding: Market returns in the 1800s weren���t all that different from our more recent experience. He goes on to explain why returns have been so consistent over time. The short version: Stock prices tend to follow corporate profits. This, of course, isn���t true every day. But over long periods, share prices do tend to mirror corporate earnings.

2. Should investors have confidence that profits will continue to grow?��I think so���because the same economic principles that applied in 1800 and 1900 still apply today. Companies are always working to develop new products, to expand the market for those products and to manufacture them more efficiently. Taken together, these three factors are the universal drivers of economic growth, and thus of stock prices.

3. Why is active management destined to underperform?��In recent years, investors have been moving money from actively managed mutual funds���that is, funds run by traditional stock-pickers���to index funds, which for the most part simply buy and hold a particular list of investments. That shift has been driven by a growing body of data showing that active managers, on average, underperform. But why is that? Is it because stock-pickers aren���t good at what they do?

In some cases, that���s the explanation. But there���s a more fundamental reason: cost. Actively managed funds are, on average, much more expensive than their passively managed peers. Of course, active managers will argue that cost isn���t the most important thing. Instead, they'll argue that the only thing that matters is bottom-line performance. Indeed, if an active manager is able to beat his benchmark by more than his fee, then an investor in that fund would come out ahead.

That sounds logical. But William Sharpe, a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics, dismantled that argument in a��1991 essay��titled ���The Arithmetic of Active Management.��� The essay is short, which is good because it usually requires reading a few times to understand what Sharpe is saying. But once you follow the logic, I think you���ll agree that Sharpe���s argument really is airtight. Active management is an uphill battle, at best.

4. What evidence is there that Sharpe is right about active management?��Twice a year, S&P Dow Jones Indices compiles a study called��SPIVA, short for S&P Index vs. Active. The study compares the performance of U.S. actively managed funds in various categories to their respective benchmarks. The results confirm exactly what Sharpe postulated. For example, over the 10 years through year-end 2021, just 17% of large-cap stock funds were able to beat the S&P 500. The results are similar in other categories.

5. If the only issue is cost, can���t individuals managing their own money beat the market?��There���s some logic to this. But unfortunately, cost isn���t the only factor. It turns out that picking winning stocks is very difficult.

Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, both professors at the University of California, have been studying this for decades. In 2000, they published ���Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth,��� which examined the connection between trading frequency and performance. In 2007, they published ���All That Glitters,��� which looked at the trap presented by popular stocks. More recently, they���ve examined the��Robinhood��phenomenon and studied some of the��paradoxes��exhibited by the trading results of individual investors.

6. Lots of people have made money in obvious winners like Apple, Amazon and Google. Doesn���t that contradict Barber and Odean���s research?��A paper titled ���Selling Fast and Buying Slow,��� published last year, helps explain the apparent contradiction. Professional investors actually do a pretty good job of spotting winners. The problem is on the other end. When it comes to selling, investors do a poor job���so poor, in fact, that it offsets the advantage gained by their timely purchases.

7. What about people like��Warren Buffett,��Seth Klarman��and��James Simons?��There���s no denying their success. Indeed, all of the data I���ve cited here should be taken with this caveat: This is what the data say, on average, about most people, most of the time. There are always exceptions.

8. If actively managed funds underperform and I shouldn���t pick stocks myself, what about private investment funds instead?��Major universities and pension funds often invest in private equity funds and hedge funds. That might lead an investor to conclude that these funds are the way to go, especially if traditional mutual funds have such a poor track record. But this turns out to be a dubious idea, for two reasons.

First, according to a��study��by McKinsey, there���s wide dispersion in the performance of private funds���much wider than among publicly traded funds. This means that it���s especially important to choose the very best from among the universe of private funds. But that presents a problem. If you or I were a billion-dollar endowment, the best funds would be happy to have us. But these funds aren���t interested in everyday investors. They���re not even interested in everyday millionaires. Andy Rachleff, a founder of Benchmark Capital, explained this, in colorful terms, in an��interview��a while back.

The second reason private funds are a problem: Because they���re more lightly regulated, private funds are fertile ground for unscrupulous operators. Everyone knows about Bernie Madoff���s misdeeds, but he���s hardly the only one. There was��Jan Lewan, the ���king of polka.��� There was��Elliot Smerling, who specialized in forgery. And there was��Marcos Tamayo, the airport baggage handler. The list is long.

And those are just the more notable cases. According to the��SEC, fee billing issues are widespread. In a speech, an SEC examiner had this to say: ���When we have examined how fees and expenses are handled by advisors to private equity funds, we have identified what we believe are violations of law or material weaknesses in controls over 50% of the time.��� Private funds are a minefield.

9. What about other alternative investments?��So far this year, both stocks and bonds have declined, so you might wonder about alternatives to these standard portfolio building blocks. Gold, for example, has declined just 7% in 2022, much better than the 20% decline in the S&P 500. Indeed, a��recent report��by the research firm Morningstar indicates that certain types of alternative strategies have fared well over time, delivering low���or even negative���correlations with stocks.

Trouble is, these relationships aren���t stable. In 2018, when the market dropped 20% toward the end of the year,��Morningstar��found that alternative investments were of little help. On top of that, correlation isn���t the only metric that matters. Cash has a theoretically attractive zero correlation with stocks. But its return is terrible. If you���re considering alternative investments, you need to consider both their diversification benefit��and��the potential contribution to returns. On that score, the data aren���t compelling.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.The post Nine Key Questions appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 16, 2022

You Don���t Have Mail

MY NEW ROUTINE is walking directly from the mailbox to our recycling container to deposit most, if not all, of that day���s mail. For years, I���ve been steadily reducing the amount of mail I send and receive. After reading Jonathan Clements���s experience with check washing, I���m looking to take this even further.

I remember when mail was important. My wife talks of growing up in Cleveland where, during the Christmas season, mail actually arrived twice a day. Now, our street randomly fails to get its daily mail delivery, presumably due to staffing shortages.

Every day in our neighborhood, UPS, FedEx and Amazon are making deliveries, sometimes more than once. I���m also diligent in watching my email because that���s where I get my utility and credit card bills, personal correspondence, ads from stores or restaurants I patronize, and notifications that new content has been added to sites such as Barron's or HumbleDollar. Meanwhile, very little of importance comes in the U.S. mail. Remember handwritten letters? I suspect the Smithsonian is working up a display.

We���ve heard for years that the post office runs annual deficits in the billions of dollars. It raises rates occasionally. Still, compared to inflation, the increase over the past few decades in the price of a first-class stamp seems like a bargain���unless you compare it to free instant delivery of email anywhere in the world.

A way to address the operating deficit would be to change residential mail delivery to three days per week. Half the homes get mail Monday, Wednesday and Friday, while the other half get it Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday. Would anyone notice?

This wouldn���t cut expenses in half because presumably commercial businesses would still need to get their mail six days a week. Or would they be okay with five? Are there any businesses dependent on Saturday delivery?

This plan might be a disadvantage for the M-W-F group because so many holidays fall on a Monday. What if you run a home-based business? Maybe daily mail delivery is important���but I suspect your business already has problems if it���s dependent on the post office. I thought about people who get their medications delivered by mail, but they already manage without Sunday and holiday delivery. Does anyone squawk when new federal holidays are added and mail no longer turns up on that day?

A business that cuts services to survive is in a bad spot, because further service reductions push even more customers away. But with the post office, it seems that ship has sailed. Customers and businesses have found alternatives. All day long, I watch UPS, FedEx and Amazon drive up and down my street. And then I check my email.

The post You Don���t Have Mail appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 15, 2022

Making It

Fletcher may have lacked military acumen, but he compensated with ingenuity and resilience learned growing up in rural Appalachia. In fall 1918, he and a million fellow American soldiers pulled off in a few months what the French had been unable to accomplish in four years. At a cost of more than 26,000 U.S. lives, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive dislodged the German soldiers from their trenches, helping to bring an end to a terrible war.

I���ll let Fletcher tell you about it in his own words. They���re preserved in a book,��Around Home in Unicoi County��by William W. Helton, that chronicles the history of our Tennessee town: ���On the morning of November 11, 1918, a bunch of us soldiers had taken a load of ammunition to the front, and when we got there it was just before 11:00, and in a few minutes, it suddenly got quiet, and the word spread fast that it was all over. What a change���the thunder of war one minute, then quiet as a tomb the next. It was like that until that night, when you could hear firing here and there in celebration. We slept on the ground that night, and although everything was quiet for the first time in four years, they set a guard. But we slept well that night, and were thankful���even the ground felt good.���

I���ll let Fletcher tell you about it in his own words. They���re preserved in a book,��Around Home in Unicoi County��by William W. Helton, that chronicles the history of our Tennessee town: ���On the morning of November 11, 1918, a bunch of us soldiers had taken a load of ammunition to the front, and when we got there it was just before 11:00, and in a few minutes, it suddenly got quiet, and the word spread fast that it was all over. What a change���the thunder of war one minute, then quiet as a tomb the next. It was like that until that night, when you could hear firing here and there in celebration. We slept on the ground that night, and although everything was quiet for the first time in four years, they set a guard. But we slept well that night, and were thankful���even the ground felt good.���A decade after making it back to Erwin, in the Appalachian Mountains of northeast Tennessee, Fletcher and his wife Lottie found themselves raising their three kids during the Great Depression. My dad smiles as he recalls listening to his Gramps spin yarns on the front porch: ���Whenever he talked about the Depression, he would always say, ���We got along just fine. We always had a roof over our heads and food on the table���.���

In 1924, Congress passed a bill to compensate World War I veterans for the income they lost while serving. The only problem was, the first payment wasn���t slated to happen until 1945���21 years later. In 1932, thousands of frustrated veterans and their families converged on Washington, D.C., in peaceful protest, urging lawmakers to deliver the aid right away. Eventually, in 1936, they succeeded in getting the stipends paid in full, and the momentum they created led to legislation that would become known as the G.I. Bill.

My great-grandfather received $800, which he used to buy several acres. The land meant opportunities to improve his family���s life. He grew fruits and vegetables, raised livestock, built a barn and cellar, and rented his cane mill for neighbors to make their sorghum molasses. Years later, my grandparents built their house on the land, which is where my dad and his sister grew up. Later, my parents built their house there, too. That���s where my brother and I grew up. My grandparents and parents still live in those same homes today.

Fletcher didn���t just set a path for our family with his land purchase. He also had a 38-year career as a carman with the��Clinchfield Railroad, which had brought its headquarters to Erwin at the start of the 20th century. His son���my grandfather���studied accounting at Steed College in nearby Johnson City and then made it his career, also working for the Clinchfield Railroad. In fact, all of my great-grandfathers and grandfathers worked for the Clinchfield. Only my maternal grandfather���Pap���didn���t retire from there. Instead, he left the railroad to serve with the Air Force in Korea. Upon his return, he attended college thanks to the G.I. Bill, and then went on to a career as a teacher, principal and superintendent with Unicoi County Schools. My mom and dad followed in his footsteps, my mom primarily as an eighth-grade science teacher and my dad as an elementary school principal.

My parents worked their entire careers for the same employer, one that had a strong defined benefit retirement plan. They had watched their parents show similar loyalty and be rewarded with a financially comfortable retirement. When your pension is overseen by the U.S. Railroad Retirement Board or the Tennessee Consolidated Retirement System, you don���t have to worry much about retirement. That���s probably why my family didn���t talk much about investing or the financial markets.

Tennessee Orange.��As a kid, I didn���t think about money much, either. All I wanted to do was play sports���basketball and baseball, to be specific. I was a child of the 1990s, so I wanted to be like Michael Jordan or Ken Griffey, Jr. I believed with everything in me that I could do something great in sports.

I performed well enough in high school basketball and baseball to earn some local recognition, but I received zero college offers. My pride was wounded. Watching my dream die, I felt acute pain. Had I failed? In 2004, going into my senior year, I accepted that this would be it���my last year playing sports. Resolutely putting that dream behind me was like dowsing my face with ice-cold water. It was the first time I ever gave much serious thought to what I wanted to do with my life after high school. Until then, I had only entertained thoughts of continuing my athletic career for as long as possible.

I needed a new vision for my life. A few years earlier, I had decided to follow Jesus, and I remember thinking hard then about what that really meant. I intended to pay attention to what Jesus said. I read in the Bible where he said, ���Life is not defined by what you have, even when you have a lot.��� I also read, ���For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.��� I filed these ideas away.

I visited a few colleges that would���ve gladly charged me a fortune, but I decided they weren���t for me. Instead, I opted to attend the University of Tennessee (UT) in Knoxville���a place where I felt at home, could cheer on my beloved Vols and would have no shortage of opportunities to explore.

The summer before college, I read a biography of Howard Schultz, the founder of Starbucks. That sparked my interest in business and finance. Then I picked up business book No. 2 of my life,��Personal Finance for Dummies��by Eric Tyson. I figured there was no better place for a complete novice to start. I skimmed through several chapters, was intrigued and decided I wanted to learn more. At college orientation, I found out that I could start school as a business major with an undecided concentration. I thought that would be perfect.

Preparing to move to campus, I thought about how I could meet new people at UT. I wanted to find others who also sought to follow Jesus, so I looked into various campus Christian groups. I noticed that the Baptist Collegiate Ministry had some fun welcome week activities, so I decided to participate. My future wife Sarah did, too. Neither one of us even went to a Baptist church at the time. By December, we knew we wanted to marry.

As Sarah and I became close, she told me how her life had been shaped by losing her dad suddenly when she was age 12. He���d had a brain aneurysm while on a business trip. I got to know Sarah���s mom���a first-grade teacher. She easily connected with my parents, and it felt like we had always known each other. I also got to know her older brother, and I began to see how admirably he stepped into managing the family���s financial responsibilities. I was only 18 years old, but I had already found the woman I would spend my life with. We had dreams of raising a family together. As clearly as I could see that vivid shade of orange all over the UT campus, I could see that my actions every day���even at age 18���would directly impact the future of my family.

In my sophomore year, I decided to study accounting and finance. I was excited about the opportunity to increase my personal finance knowledge. I was no doubt influenced by the legacy of my accountant grandfather, as well as stories of Sarah���s dad, who had been the director of audit for the University of Tennessee.

I remember sitting in one of the old brick buildings up on the Hill at UT for my first day of finance 101. I couldn���t tell the teacher from the students. He was a young guy, casually dressed. He began the first lecture by telling his story. In the late 1990s, he had been part of a fast-rising Silicon Valley technology startup. Many of his friends had cashed out their stock options at the right time and were now multi-millionaires. He held on too long. The company went bust���along with his stock options���and that led him to return to school to pursue a doctorate in finance.

As I processed his story, I thought to myself, ���How could he have seen that coming? I doubt that his tech friends were that much more financially savvy than him. It seems like there was a lot of luck involved. There has to be a better way.���

Later that semester, I studied how a mutual fund provides diversification, and I was introduced to the concepts of asset allocation and correlation. In my next finance class, I gawked at the professor���s illustrations of compounding returns. I began to realize that I could build financial success on a foundation of discipline���a firmer foundation than either luck or purported skill.

Falling into place.��On June 20, 2009, Sarah and I were married in the church sanctuary that her dad had been instrumental in building as a leader in the church. We both began master���s degree programs at UT���Sarah in nutrition science and me in accounting with a tax concentration. During the recruiting season that fall, I secured a job with a boutique Knoxville CPA firm called Burkhart & Co. that provided tax compliance, financial planning and consulting services. I would start the fall after I graduated.

In one of my tax courses, we delved into the mechanics of IRA taxation, including the difference between traditional and Roth accounts. Our professor illustrated how compounding returns look even better when they���re tax-free. I took notice. I opened a Roth IRA at the Edward Jones office of a family friend. The active funds he suggested were the first investments I���d ever bought. Sarah already had a Roth IRA there, and she added to hers. We began investing regularly at clearance prices���this was right after the stock market bottomed in 2009.

Sarah and I both left school with a master���s degree and no debt. Over school breaks, I had already knocked out two sections of the CPA exam. Before I started my job, I passed the third and fourth parts.

Not long after the real estate bubble burst, we bought our first house in Knoxville, using some funds that Sarah had received from her dad���s estate as our down payment. Our realtor told us it was the best deal he had ever seen. With our two incomes, the payment was manageable. A few years later, we jumped at the chance to refinance to a 15-year mortgage at 3% interest. We realized that we were benefiting from good circumstances and timing, but we didn���t chalk it up to luck. Instead, we were thankful to God. We believed what David said in the 23rd Psalm: ���The Lord is my shepherd; I have all that I need.��� We knew we were reaping what had been sown by several generations of our families���working hard, fighting to keep their marriages strong, and investing in a better life for their kids.

Not everybody had the kind of opportunities we had and we wanted to do something about it, so we chose to sponsor a seven-year-old boy in Tanzania through��Compassion International, a charity that connects donors with children in poverty. We started giving $38 every month to help finance his local Compassion program, which functioned through a church that was already serving the community. We wanted to help Stanley have the same things we cherished in our own upbringing���a close-knit support system focused on his spiritual formation, character development and education.

Meanwhile, at church, we took counseling classes for a year and then started serving in the peer counseling ministry, which allowed us to help others in the local community. The director of counseling became a trusted friend. Before switching careers, he had also been a CPA. He and his wife had two boys���one with special needs. He implored us to save as much as possible during our two-income-no-kids years. We listened.

At work, Burkhart & Co.���s founder and president, Renda Burkhart, quickly became a mentor to me. I remember sitting in her office as she explained how index funds work. She enthusiastically recommended Jack Bogle���s��The��Little Book of Common Sense Investing. I devoured it. Sarah and I built a sturdy financial foundation with a Roth IRA for each of us, a qualified retirement savings plan through each of our employers, a health savings account and a taxable brokerage account. We consolidated our accounts at Vanguard Group, where we favored index funds and put an emphasis on low fees for the active portion of our portfolio.

Not like we planned.��When the time came to have kids, we assumed there would be no issues. It wasn���t long before we discovered how naive we were. We tried to conceive for more than a year but couldn���t, so we were overjoyed when we found out early in 2013 that Sarah was pregnant. A few weeks later���when I was buried with work during the spring tax season���I got a call from Sarah in the middle of the workday. I ducked into the library to take it. I can still recall the wall of books I stared at, while she told me through tears that we���d lost our baby. Only our parents had known that we were pregnant���or even trying���so we told very few people about our loss. For the next three months, I was consumed by the demands of tax season. That, in part, meant Sarah and I didn���t really have the chance to grieve together.

Around that same time, I started leading client relationships at the firm. I wanted a more thorough and confident knowledge of estate planning and investing, so I enrolled in the University of Georgia���s executive education program to prepare for the Certified Financial Planner (CFP) exam.

After the miscarriage, we were unable to conceive for another year. Then, in spring 2014, we found out that we had another baby on the way. Learning of this pregnancy was again a joy, but it was far from a relief. Instead, it was the start of a long season of agonizing anxiety for Sarah. At work, my responsibilities continued to grow. The fall tax season arrived and again brought long hours for months on end. On top of that, I had a November CFP exam date looming.

It all became too much for me. I suffered from my own intense anxiety and fear. I felt like I was letting everyone down. I didn���t have enough to give to satisfy the demands of work. I was falling behind in my CFP exam preparation. But more than anything, I was fiercely determined to support Sarah with more of my time and presence. I was angry and bitter that work had prevented me from being more supportive after Sarah���s miscarriage. I stumbled along but ended up passing the CFP exam in November. Our daughter Lydia arrived five days later.

It took some time, but I eventually swallowed my pride and asked for help. I learned to accept that I didn���t have what it takes to carry all these burdens on my own. I stopped doing peer counseling for a season and, instead, learned how to be on the receiving end. A lot of people showed me a lot of grace in those days.

Hunting for treasure.��At Burkhart & Co., we all benefited from Renda���s stellar reputation in the Knoxville community, which attracted an impressive clientele. I developed a specialty working with high-net-worth families, including helping with their trusts and estates. Working with these families was a fascinating opportunity to study people who���by all objective measures���had made it. It didn���t take me long to understand that ���making it�����didn���t stop people from having to wrestle with money and other issues. Several of my clients were living my childhood dream as professional athletes or as Division I college coaches. Those with first-generation wealth struggled to discern who their real friends were, when to share their newfound financial surplus and when to put up healthy boundaries. As the generational wealth passed further down the family tree, kids had trouble with entitlement and finding value in work. With possessions came worries and burdens. Relationship strife usually followed close behind.

At the dawn of another spring tax season, Sarah and I got the good news that we were expecting for the third time. Soon after, we suffered our second miscarriage. We were heartbroken, but I had learned from my past mistakes. Even though it was the busiest time of the year, I canceled all my client meetings and worked from home for a week, so I could grieve with Sarah and Lydia. We received an outpouring of love and support from friends and family. We were both weary, but we still longed to add to our family. This time, we didn���t have to wait another year. Within a few months, we celebrated the news of our fourth child. Eliza arrived the next February.

Each time we lost a baby or celebrated a birth, we sponsored another child through Compassion International in honor of the miracle of their life. We now have eight children, from all over the world, in our extended family. We���ve exchanged hundreds of letters where we share our lives and learn about each other���s cultures. We send birthday and Christmas gifts every year. We pray for them and they pray for us. We love involving our two girls in all of this. Our Compassion friends have money concerns of their own. The kids��� parents often can���t find consistent work, and their families do without much of what we consider to be basic necessities. The kids usually spend their birthday money on shoes for themselves or on rice and beans for their family. Rarely, if ever, do they get to buy a toy.

As I���ve gotten to know both many high-net-worth families and those who are used to doing without, I have observed something that surprised me: We are all more alike than I ever would���ve thought. We all have to make the same fundamental decision. Sure, we come at it from different perspectives and different parts of the wealth spectrum. But we all have to decide: What do we ultimately treasure? What we treasure will, in time, determine who we become.

The view from here.��This morning, as I write this, I sit on the front porch of my parents��� house, taking in the view of the mountains and the fields below, where my grandparents��� house sits. I worry about my 93-year-old Paw���s failing health and mind. I worry about Grandmaw and Dad as they take care of him. I am thankful for the visit we had this weekend���four generations enjoying this moment together.

As I reflect on my money journey thus far, I notice that two contrasting mindsets have regularly guided my decisions. Sometimes, a long-term view has led me to make current sacrifices for a future payoff. Other times, I have chosen slower progress toward a long-term goal in favor of the moment. The hard part has been knowing��when��to take which approach. There���s usually no fanfare alerting me that it���s time to perk up and focus on this important choice.

I constantly have to remind myself that it���s the mundane days that really are the substance of my life. And it���s for those days that I���m especially in need of some wise and practical advice. I find it in the words of longtime University of Southern California philosophy professor, Dallas Willard. He wrote in��Renovation of the Heart in Daily Practice: Experiments in Spiritual Transformation��that, "At the beginning of my day, I commit my day to the Lord's care���. Then I meet everything that happens as sent, or at least permitted, by God. I meet it resting in the hand of his care. I no longer have to manage the weather, airplanes, and people." To that list, I might add the financial markets and the status of my retirement nest egg.

When I start my day with Willard���s exercise, I find I���m more likely to live that day as though I treasure what I say I do. I treasure Jesus. My apprenticeship to him leads me to value people���my family, my neighbors���over possessions and accomplishments. Sarah and I have been in agreement for some time about what we treasure, but that hasn���t confined our money journey to a predictable path���far from it. For a season, we pursued our financial goals at a rapid pace. As circumstances changed, we chose to let go of some promising financial opportunities to free up space for other priorities.

That led to a career change for us both.��I left the public accounting profession to put better boundaries on my career���s demands. Now I get to put my expertise to good use at one of Knoxville���s largest employers���and have the freedom to do freelance writing, too.��Meanwhile,��Sarah took a part-time teacher's assistant position that gives her the ideal schedule and invaluable connectedness at Lydia's school. We prefer a lifestyle of measured frugality. It affords us the ability to continue progressing toward tomorrow���s financial goals���albeit at a slower pace���while still enjoying today���s profound gift of unhurried presence.

This year, Lydia played in a basketball league for the first time, and I got to coach the team. Being in the gym again had me reminiscing about my glory days. I have to admit: I���m a little embarrassed about how one-track minded I used to be about playing sports, without ever thinking seriously about whether it was worth it. I wonder, where did I think ���doing something great in sports�����was going to get me? Back then, I failed to recognize that no matter how far I went, eventually it would end���and life would go on.

���Making it�����is an illusion. I have already accomplished some meaningful financial goals and some are within reach, but I still have a long way to go to reach many others. When I achieve them, life will go on. I���ll make new goals then. But whether it���s then or now, I want my life to emanate the same qualities: thankfulness, contentment, discipline, diligence and charity.

Matt Christopher White is a CPA and CFP�� who writes about money and apprenticeship to Jesus. He's the author of ���How to Love Money: Four Paradoxes that Breathe Life into Your Finances,��� available at MattChristopherWhite.com. Matt is equally comfortable talking about Luke 6:43, Section 643 of the Internal Revenue Code and the 6-4-3 double play. There���s no place he���d rather be than with Sarah and their two girls, Lydia and Eliza, at their home in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. Follow Matt on Twitter @WriteMattWhite and check out his earlier articles.

Matt Christopher White is a CPA and CFP�� who writes about money and apprenticeship to Jesus. He's the author of ���How to Love Money: Four Paradoxes that Breathe Life into Your Finances,��� available at MattChristopherWhite.com. Matt is equally comfortable talking about Luke 6:43, Section 643 of the Internal Revenue Code and the 6-4-3 double play. There���s no place he���d rather be than with Sarah and their two girls, Lydia and Eliza, at their home in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. Follow Matt on Twitter @WriteMattWhite and check out his earlier articles.The post Making It appeared first on HumbleDollar.

How Are We Doing?

FRANKLY, I DIDN���T KNOW how wise or prudent our investments are, so I decided to take a closer look.

Turns out my wife and I are fairly well diversified, but is it the right mix? Our investment goals are preservation of capital, generating income and modest growth. To achieve these goals, we have a mix of money market funds, dividend-paying individual stocks, and bond and stock mutual funds���mostly stock-index funds. The stock funds include large-cap and small-cap, and a bit of international as well.

In our brokerage account, two utility stocks account for 40% of the total balance, stock mutual funds 13%, municipal bond funds 44% and money market funds 3%. Meanwhile, my rollover IRA���which is my old 401(k)���is invested 67% in stock mutual funds, 23% bond funds and 10% money market funds.

Overall, that means we���re 23% in individual stocks, 37% stock funds, 34% bond funds and 6% money market funds. Currently, all capital gains and income are reinvested. We can turn any and all of those automatic reinvestments on or off at any time. Dividends are paid quarterly, tax-free interest monthly and capital gains generally annually.

Clearly, we could have done better during the recent bull market���but the higher stock allocation would have meant we���d have done much worse in this year���s downturn. Based on our goals, I���ve been told that we should take a longer-term view and be more aggressive. Yeah, I���m not feeling aggressive.

Given that we live off my pension and our Social Security income, our primary goals are to leave a legacy for our children and to withdraw from investment earnings should we need additional income���or, if I die first, should my wife need additional survivor income.

Do we have the right mix for maximum return? Probably not. Do we have the right mix to meet our goals while minimizing stress? I think so. I hope so.

The post How Are We Doing? appeared first on HumbleDollar.