Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 194

August 13, 2022

Mounting Costs

INFLATION CROPS UP in almost every conversation I have with friends and acquaintances. Everyone���s getting squeezed by higher prices. Folks complain not only about where prices are today, but also about how quickly they rose.

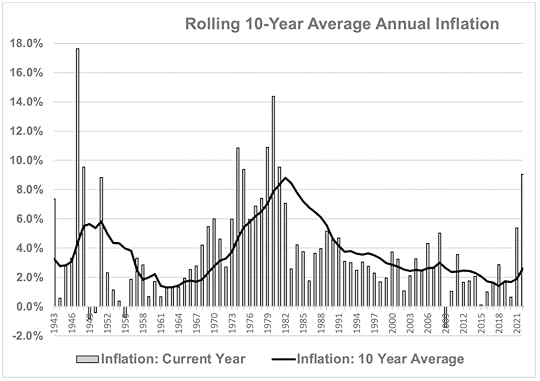

Prices today seem shocking compared to last year or the year before that. But how do they compare to prices from 10 years ago? To find out, I calculated the average annual inflation rate over trailing 10-year periods using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). The chart below shows the rolling 10-year average annual inflation rate for the past 80 years.

Lately, 12-month CPI-U has been running around 9%. But if we extend the time horizon back 10 years, to mid-2012, the recent spike barely registers, with the average annual increase for the past decade coming in at just 2.6%. From this longer-term perspective, inflation looks deceptively mild.

Going back 10 more years, the average annual price increase for the 10 years through mid-2012 was 2.5%, almost identical to the most recent 10-year stretch. Does anyone remember a ruckus being made about price increases in 2012 similar to the one being raised today?

��My point: A sudden surge in inflation causes panic, but the insidious effect of slow and steady inflation gets little attention. When I pointed this out to a friend, he wasn���t impressed. It seems he would���ve preferred steady, annual price increases of 2.6%, instead of the low inflation we���ve enjoyed for much of the past decade followed by a sudden spike.

I wasn���t so sure. Why not? Let���s assume my friend���s annual spending as of mid-2012 was $10,000 a year and his yearly expenses went up in lockstep with CPI-U. His total expenses from July 2012 to June 2022 would amount to $110,267. But if, instead, he got his wish of steady 2.6% annual inflation starting from 2012, his spending over the 10 years would have been $115,405���almost 5% more.

Why the difference? Remember, each year���s inflation builds on past price increases, so���if you must have inflation���it���s less damage if you have low inflation early on and higher inflation later.

For proof, let���s run history backward. I���ve taken the actual inflation numbers from the past 10 years but reversed their order, assuming that the annual inflation rate was 9.1% in 2013, 5.4% in 2014, 0.6% in 2015 and so on, ending at 1.8% in June 2022.

In this backward universe, my friend���s cumulative expenses for the 10 years would climb to $120,569. That���s 9% more than before. The reason: The inflation spike came at the start of the 10-year period rather than at the end.

This experiment demonstrates sequence-of-inflation risk. High inflation at the start of a period is more costly to us because higher prices stick around, even if inflation subsequently settles down. In other words, prices reach a permanently higher plateau after a spike and then continue climbing from there.

This sequence-of-inflation risk is particularly dangerous for folks who are in the early years of retirement or who are planning to retire shortly. The risk has similarities to sequence-of-return risk���the double-whammy of suffering investment losses early in retirement while also withdrawing from a portfolio���but it���s harder to counteract.

If the market drops in the initial years of retirement, retirees can dodge the bear market by living off their stable investments, instead of selling stocks at lower prices. No lasting harm is done to the retirement portfolio if we can weather the entire bear market���which might last several years���in this manner. When the market rebounds, the effect of the earlier price drop disappears as if nothing happened.

Sadly, it���s not so simple with sequence-of-inflation risk. Retirees can���t simply stop spending when inflation runs high. Moreover, the elevated prices from a high inflationary period stick around even when inflation eventually tapers down. The result is significantly higher withdrawals over the course of retirement.

What, then, would be a good strategy to handle sequence-of-inflation risk? First, stocks are a great inflation hedge over the long run. Some experts suggest that, even in retirement, allocating a minimum 50% of total investable assets to stocks might work well to fight unexpected inflation.

Second, for cash and bond investments, there are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS, but they come with a catch. When we buy TIPS, the expected inflation rate is already priced in. That means we���re insured against additional unexpected inflation from there. But it might be too late to invest in TIPS if the breakeven inflation rate���the difference in yields between a regular Treasury bond and its inflation-protected counterpart���is already high. If inflation turns down over the holding period, the high price paid for the inflation protection would be wasted.

The breakeven inflation rate for both��five-year and 10-year Treasurys spiked above 3% in recent months, but has come down since. As we���ve seen, that peak is a bit higher than the long-term inflation rate in recent decades.

Most of my non-stock investments are in a short-duration TIPS fund, but I���m thinking of replacing it with a ladder of individual TIPS bonds, each maturing in a different year. Inflation���s bite on my finances will eventually weaken once I start receiving Social Security benefits, with their annual inflation adjustment. But until then, my TIPS ladder should provide some relief.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is��passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is��passionate about raising financial literacy and��enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.The post Mounting Costs appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 12, 2022

What They Believed

I MOVED FROM LONDON to New York in 1986. For the next three-plus years, I worked as a lowly reporter (read: fact checker) and then staff writer at Forbes magazine, before I was hired away by The Wall Street Journal. During those three years, I set out to educate myself on U.S.-style personal finance.

Forbes was a great place to do that. The magazine’s Greenwich Village offices had a well-stocked library of financial books and company reports, plus all kinds of periodicals circulating through the editorial department. Equally important, the pace of work was slow enough that there was time to take it all in. Other reporters would quip that working at Forbes was as good as getting an MBA, and I think they might have been right.

What did I learn at Forbes? I got a handle not just on personal finance basics, but also on prevailing attitudes toward managing money. Here are six financial opinions that were then widespread—but have since fallen by the wayside:

1. Plenty of active managers beat the market, and it’s easy to identify them ahead of time.

By the late 1980s, there were already numerous studies that undercut this belief—including one published as long ago as 1932—and yet it was still widely embraced. Indeed, it wasn't until the early 2000s that a broad swath of the investing public started abandoning actively managed funds in favor of index-mutual funds and especially exchange-traded index funds.

It's been a wise move, as evidenced by S&P Dow Jones Indices’ ongoing study of actively managed funds. For instance, among the nine U.S. style boxes, the best performing actively managed funds over the past 20 years have been large-cap value funds—and, even in that category, an astonishing 83% of funds have failed to beat the category’s benchmark index.

2. Financial advisors’ role is to help investors buy products.

That product might be a stock, a mutual fund or a variable annuity. The advisor’s role was to call occasionally with investment ideas and—if you bit—he or she would get a commission.

What about the conflict of interest—the distinct possibility that the advice was driven less by your financial needs and more by the advisor’s hunger for another commission? What about looking at your overall portfolio and pondering whether your investments collectively made sense? What about other financial issues, like estate planning, taxes, when to claim Social Security, insurance and—perhaps most important—figuring out whether you’re saving enough to meet your goals? Put it this way: There’s a reason commission-charging brokers have become dinosaurs and fee-only financial planners have seen their business boom.

3. Some investments are worth paying up for.

How about a mutual fund with an 8.5% load? Or a variable annuity with total annual expenses equal to 3% or more of assets? Or a hedge fund that takes 2% of clients' assets each year and 20% of all gains? Back in the late 1980s, such costs were considered acceptable by many. In fact, I remember brokers arguing that load funds were inherently superior to no-load funds, that they generated better returns and that the load created an incentive for the fund manager to outperform the market. I kid you not.

A digression: During the 1990s, I wrote about the inferior results earned by load fund investors. Within days, a delegation of Merrill Lynch executives was dispatched to the Journal’s offices to complain bitterly about my story and to share data that purportedly debunked it. As the meeting ended and we were filing out of the conference room, Paul Steiger—then the Journal’s managing editor—gave me a surreptitious smile and whispered, “They didn’t lay a glove on you.”

Today, few investors are nonchalant about costs—and, indeed, rock-bottom fees have become a major selling point for fund companies and brokerage firms. That doesn’t mean costs are no longer something we need to worry about. Yes, horrendously high commissions and expense ratios are less common. But investors still face less obvious costs, such as the bid-ask spread on individual stocks and bonds, high fees for separately managed accounts and miserably low yields on the cash accounts offered by many financial firms.

4. Stocks don’t stay at elevated valuations for long.

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, many investors, scarred by the U.S. stock market’s wretched returns between 1966 and 1982, fretted as price-earnings ratios climbed and fully expected the market’s multiple to fall back to its long-run historical average. But instead, in the three decades that have followed, there have been few moments when stocks have been objectively cheap.

There are all kinds of reasons for this, including lower interest rates making stocks more attractive, falling investment costs, a growing appetite for risk, and a market dominated by technology stocks that look expensive based on standard market yardsticks. The upshot: Relatively rich valuations don’t necessarily foretell lousy performance in the months and years ahead.

5. The dream is to retire early to a life of endless leisure.

Early retirement, of course, is still the goal for many folks. But what’s changed is our conception of what constitutes a good retirement. Today, many retirees believe that, to have a fulfilling retirement, they need to engage in activities that bring a sense of purpose to their final decades.

I’m certainly in that camp—in part because I saw how my father handled his own retirement. He retired in his mid-50s and, a few years later, moved to Key West, Florida, where he knew almost nobody. Key West might seem like paradise to some, and I imagine that’s where my father thought he was headed. But instead, I fear his final 15 years were somewhat lonely and aimless, and that he wasn’t all that happy.

6. Social Security should be claimed as soon as you retire.

I didn’t spend much time studying Social Security until the late 1990s—which, by itself, tells you how little discussion there was of Social Security claiming strategies at the time. Indeed, when I finally started digging into the topic, I can still recall the dearth of available information.

Today, by contrast, the question of whether to delay Social Security, and thereby ensure both a larger benefit during your lifetime and a potentially larger survivor benefit for your spouse, is considered perhaps the most important decision facing retirees. But in the late 1990s, it was barely debated, and instead the prevailing assumption was that you should claim as soon as you quit the workforce. Want to make a more considered decision? A great place to start is the calculator built by Mike Piper of ObliviousInvestor.com.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post What They Believed appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Chips With Everything

I EXPERIENCED a traumatic event recently: 24 hours without an iPhone. When I left the house, I felt out of touch, incommunicado. What if someone needed me or I needed them? What if I missed the latest Tweet? It was horrible.

My iPhone X was just about kaput, with a cracked screen and a weak battery. On a trip to the mall, I walked into an AT&T store “just to look.” I ended up with an iPhone 13 Pro, gold-colored no less, with a clear cover so everyone can see it’s gold. To what purpose, I have no idea.

In any case, I traded in the old model and my cost for the iPhone 13 was $27.70 a month for 36 months. But it gets better. I also received a billing credit—the salesman said it was some sort of special deal—which brought the net to $13.33 per month, so the total cost was $479.88. When I bought my old iPhone X, I paid $1,000 cash.

Switching your data from an old to a new device is easy. You just set the two next to each other and they do it for you. That’s what happened—except the new phone couldn’t recognize my telephone number. That meant no texting, no calling in or out. We’re talking utter isolation. I tried everything recommended on various websites. Nothing worked. My wife knew I wouldn’t be worth living with until I was again part of the real world, so the next morning we were at the AT&T store when it opened.

After several failed attempts to fix the phone, the technician decided the problem was a defective SIM card, whatever that is. A tiny piece of I don’t know what had disrupted my world.

I’ve come to realize that the most important word in our language is “chip.” Our entire lives are controlled by chips, everything from cars to robotic surgery to your phone’s selfie EKG app. Technology gives new meaning to having a chip on your shoulder. The array of things we can do with our smart phones is truly amazing—and being a phone is the least of its functions.

My love affair with phones goes back to the 1964 World’s Fair when AT&T displayed its new video phone. Imagine that, seeing the person you were talking to. But it turned out few people wanted to see the folks they were calling and the video phone was a flop. Good thing nobody told Steve Jobs.

Communication has changed dramatically. We’ve gone from it taking months to get a message across the pond to milliseconds—-with video no less. I recently butt-dialed a friend in England and woke him at 1 a.m., but at least the call was free using WhatsApp.

What about the ability to communicate without actually seeing or speaking with a person? Is that good? In some ways, I think it is. Still, receiving a birthday greeting via text message is surely different. But at least it’s cheaper than the $6.95 greeting card I refuse to buy.

The post Chips With Everything appeared first on HumbleDollar.

A Narrow Escape

I ENVY THOSE WHO can remain patient and calm in almost any situation. Thanks to my neurotic personality, I find it hard to wait for an outcome over which I have little control. This year, I narrowly escaped that sort of agonizing experience. What happened? We found ourselves selling our home during 2022’s suddenly cooling real estate market.

I was surprised last year when the red-hot property market pushed our modest home past the $1 million mark. With prices so high, we decided to sell our paid-off house and move to one that offered more space and privacy. The place we settled on as our next home was a 50-year-old house in dire need of repairs and a facelift. We wanted to remodel it before moving in—and before selling the house we currently lived in.

The remodeling started last summer at a sluggish pace. It was great not to live in a house that’s being remodeled, but it also made it harder for us to monitor progress and deal with contractors. The work dragged on, thanks to supply issues, contractor delays and COVID.

I pretended to stay patient.

My anxiety started rising as whispers about a possible cooling of the housing market grew louder. After all, we had to sell the old house after we moved into the new one. If it didn’t sell within a reasonable time and at a reasonable price, it would mess up our financial plans. I neither fancied being a landlord nor wanted to leave a large chunk of our assets locked up in real estate.

As mortgage rates ticked higher, we revised our plan. Instead of waiting for the remodeling to be wrapped up, we decided to move in by early spring. We called up a moving company and set a date in March. We hired another contractor to expedite the remaining work. Feeling pressured, our general contractor added more workers to compensate for the delays. Both my wife and I started supervising the crew after work and on weekends to make sure the place was livable by the time we moved in.

The house we lived in also needed work, including painting the interior, replacing the kitchen sink, polishing the hardwood floors and deep cleaning. An inspection arranged by our real-estate agent, Rana, who quickly became a dependable friend, revealed more things to fix. We lined up new contractors so the work could start immediately after we moved out.

Meanwhile, the remodeling of our new home picked up steam. On an auspicious day in February, we did Griha Pravesh, a Hindu ritual to bless our new home. We moved in on the scheduled date, but instead of relaxing and enjoying the new place, we had to turn our attention to selling the one we’d just left behind.

Things didn’t go smoothly. The contractor quit on short notice. The substitute contractor almost ruined the hardwood floors. A few interior doors that were removed for painting got damaged. We found a large stain on the living room carpet that had previously been hidden under furniture. The empty house looked a complete mess—and nowhere near ready to be put on the market.

My blood pressure shot up, with a further assist from rising mortgage rates and thoughts of a housing market slump. My wife stepped in to take over.

When we moved out, we thought prepping the old house for sale would take a few days. Instead, it took more than four weeks to refinish the hardwood floors, install a new carpet, repair doors and deep-clean the house. A second inspection indicated the place was ready to list. All we needed to do was finalize the asking price. I kept it simple.

Two of our neighbors had sold their homes the summer before, and those houses were almost identical to ours. I averaged their sale prices and adjusted it based on the subsequent change in the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller home price index for our metropolitan area. The resulting number was 15% below the online estimates from Zillow and Redfin, but I chose to stick with the lower price. The house went on the market on April 28.

Only seven other houses in our city were on the market that week. Homes were selling almost overnight just a few weeks earlier. We had a decent number of visitors, but it took a week to get the first offer. It was from a young couple with a small kid, just like us when we bought the house in 2006. We accepted their offer right away.

A week or two later, I went back on Zillow to see how many of the other seven houses were still on the market. It was partly out of curiosity—and partly to gauge the market in case our pending sale fell through and we needed to re-list. I was shocked to see the change. I found that not only were some of the seven houses still on the market, but also there were dozens of new listings, including another neighbor’s house that was identical to ours.

As the market landscape swiftly changed, my anxiety rose, too. What if the appraisal came up short, or the loan got rejected, or the buyers bailed out? The earnest money wouldn’t compensate for the stress of having to go through the whole process all over again.

Rana sensed my worry and did what you’d expect from a thoughtful friend and experienced realtor. He kept in touch with me throughout the closing process to report progress. Finally, the wait was over. The closing happened on schedule, ending my agony.

As I write this, the neighbor’s house has been on the market for more than 60 days, despite three rounds of price cuts. I couldn’t have taken that stress. I feel lucky we made our narrow escape.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.The post A Narrow Escape appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 11, 2022

Eyeing the Cake

I JUST REACHED my full Social Security retirement age of 66 and four months. Funny, I don’t feel a bit older. Still, I am now entitled to 100% of the benefit that I’ve earned since I started working.

Conventional wisdom says to delay filing. Each month that I wait will add 2/3rds of 1% to my eventual benefit. That adds up to a risk-free 8% a year. If I were to wait until I turn 70, I’d get the maximum possible payment under the rules of the game.

Only 3% of Social Security beneficiaries wait until age 70—and I now know why. My wife and I have been savers all our lives. But today, we’re subtracting from our accounts, and it feels unnatural. The bear market hasn’t helped. On top of that, I feel inflation’s drag whenever I wheel a cart around the grocery store or gas up the car.

I didn’t have any trouble waiting from age 62, when I first became eligible to receive benefits, until now. I was working most of that time. But now that I’m largely retired, it feels like there’s a rich chocolate cake waiting for me in the kitchen. It’s been on my mind.

Everyone says you can’t get a risk-free 8% return anywhere else. On the other hand, if I file for benefits now, I stand to enjoy the largest cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) in 40 years. If inflation continues to run hot, it could be more than 10%.

To be sure, that COLA will also boost my eventual monthly check, whenever I choose to claim it. I have a hefty benefit increase coming, whether I file for Social Security right away or delay. In the interest of willpower, I’ve chosen to think of my choice as a layer cake. Each year I wait, I’ll be getting an extra layer equal to 8% plus the rate of inflation.

In other words, if I delay one year, I might get an 18% raise. Two years might deliver—who knows?—perhaps a cumulative gain of more than 30%.

If I can just wait it out.

The post Eyeing the Cake appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Less Is Better

I CONTINUE TO LOOK for ways to simplify my life. At age 71, I want fewer things to deal with and to worry about. To that end, here are five steps that my wife and I are taking:

1. Consolidating finances. I mentioned in an article last year that my wife and I have consolidated our investments at Vanguard Group, while our savings and checking accounts are at a local credit union.

I���d also like to trim the number of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) we have at Vanguard. We currently have six. I���d like to reduce that number to three. I believe it would further simplify our finances without sacrificing performance. I envision a low-cost, highly diversified portfolio consisting of these ETFs:

Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (symbol: VT)

Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF (BND)

Vanguard Short-Term Inflation-Protected Securities ETF (VTIP)

Currently, a personal financial advisor from Vanguard is managing our investments. I���ll have to fire her because she���d never approve of a portfolio without a total international bond index holding.

What about making our portfolio even simpler by owning just one fund, such as Vanguard Target Retirement Income Fund (VTINX)? Even though it���s a fund of funds, I feel uncomfortable putting all our money in just one fund because of the lack of flexibility.

For instance, if I needed to withdraw money from my investments in a bear market, I���d probably want the money to come from my short-term bond holdings. When you own a target date fund, you don���t have that option.

I���ll wait until my portfolio rebounds from this bear market to make any changes.

2. Consolidating medical records. This year, I switched medical providers. I chose the University of California-Irvine (UCI) as my primary provider. It can give me all the medical services I need.

My previous provider would sometimes refer me to specialists who weren't within the same medical group. As a result, all my medical records weren���t available in one, easily retrievable location.

Now, all of my doctors��� notes, tests, medications and vaccination records are located on UCI���s medical website. This increased transparency can help prevent duplicate tests and prescriptions, while providing me with better overall health care.

3. Owning fewer automobiles. After my wife and I retired, we realized owning a second car wasn���t a necessity. We rarely needed two cars. When we did, one of us could have easily used a ride-sharing service.

Our 2007 Honda Fit is unreliable. Instead of replacing it, we���re going to give it a go with one car. Not only will we avoid purchasing another vehicle, but also we���ll save on insurance, registration and maintenance costs. In addition, there���ll be time savings because we won���t have a second car that needs to be gassed up or taken to be serviced.

4. Using less water. I���m debating today whether I should take a shower or wash my car. I shouldn���t do both. I live in California, where we're living under an extreme drought. The state has asked residents to voluntarily reduce water usage by 15%. In some parts of California, there are restrictions on outdoor watering.

Where we live, there are no mandatory restrictions. But my wife and I are careful not to waste water. For instance, when we���re cleaning the floors or doing other household chores, we pour the excess water on our plants. We also don���t let the water run when brushing our teeth or showering.

We could easily afford to pay a penalty and use as much water as we desire. But we don���t see it as a money issue. It���s not about what we can afford���it���s about doing what���s right.

5. Taking shorter trips. My wife and I recently came home from a five-week trip to the U.K. Although we had fun, it was too long. We were exhausted when we got back. Maybe driving on the left-hand side of those winding, narrow streets had something to do with it. I know my wife was uncomfortable watching me navigate those roads.

After returning home, I told her we aren't spring chickens anymore. It might be wise to limit our overseas trips to no more than three weeks to reduce the chances of getting caught abroad with a medical disorder. Although we could purchase insurance for medical care outside the U.S., it���s always best to be close to your own doctors in case of an emergency.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. Check out his earlier��articles��and follow him on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. Check out his earlier��articles��and follow him on Twitter @DMFrie.The post Less Is Better appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 10, 2022

Don’t Sweat It

BEING MECHANICAL and unemotional is a poor way to live life. But when investing, it just might make you richer.

Through this year’s stock market turbulence, I’ve been even keeled. My reaction to the plunging bond market has been more agitated, as I wrote about here and here. The fact is, while I’m convinced the stock market will rebound, I don’t have the same belief in bonds.

Armed with my faith in stocks, I’ve adopted a mechanical approach to investing, primarily using stock index funds. No more trying to outsmart the next guy. I don’t have to time everything exactly right or worry about where shares will bottom. I have an allocation target for stocks as a percent of my total portfolio, along with preset trigger points at which I intend to buy more during substantial market dips.

Pretty much all I need to know during a downdraft is, how far is the market from its peak?

Sure, I subscribe to The New York Times, Morningstar and even Barron’s. I take advantage of the office subscription to The Wall Street Journal. I’ve got a wicked FinTwit feed of great financial journalists and pundits. And, of course, I read HumbleDollar.

Still, as I make stock market decisions, it’s amazing all the things I don’t have to read. By avoiding overconsumption of financial news and advice, I keep my emotions in check and insulate myself from the temptation to put too much stock in predictions that seem persuasive in the moment.

I don’t need to know how long bear markets have lasted historically, or their average decline, though I’m grateful to those who produce such information. I also don’t need to know what the market expects from future Federal Reserve interest rate moves. I don’t even need to know whether inflation has peaked or whether market participants believe inflation has peaked.

For instance, on Aug. 2, I learned from my Twitter feed that Credit Suisse says “war is inflationary” and the federal funds rate is headed as high as 6%, while Bank of America says virtually the opposite, forecasting that 10-year bond yields are headed back down toward 2%. Both predictions potentially have big implications for stocks, but are pretty much worthless for making investment decisions.

What am I to do with suggestions that the dollar will supposedly soar inexorably, particularly against the yen, except perhaps wish I could afford another overseas trip? To change my approach on the proposition that the dollar will continue rising—for instance, by selling a Japan fund that I invested in last year—would be speculative. The good news: The fund is actually holding up relatively well in 2022.

I do admit to an interest in which market segments and asset classes appear inexpensive compared to others. One of the few market bets I’m making is on small-cap value stocks, where I have a modest tilt both in the U.S. and overseas, including in Japan.

But these days, I hunker down when the stock market is falling. I try to limit my intake of bad news—and there has been so much this year—so it’s easier to be patient and stay the course.

All I need is the aforementioned faith that company shares are almost certain to continue outpacing all other asset classes—as well as inflation—over the long term, as they have for centuries.

Having that conviction, I follow a pre-established plan to buy the dips at set thresholds as the market stair-steps down. Substantial correction? Put more in. Deeper slide? Buy. Bear market? Don’t sweat it. Trim one of my Treasury funds and buy again.

All of which I’ve done this year. Younger me would have been obsessed with buying at the very bottom. But such a pursuit is vain and exhausting—and success could only come from dumb luck. My more stoic approach to market swoons should prove rewarding enough in the long run.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart and check out his earlier articles.

The post Don’t Sweat It appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Don���t Sweat It

BEING MECHANICAL and unemotional is a poor way to live life. But when investing, it just might make you richer.

Through this year���s stock market turbulence, I���ve been even keeled. My reaction to the plunging bond market has been more agitated, as I wrote about here and here. The fact is, while I���m convinced the stock market will rebound, I don���t have the same belief in bonds.

Armed with my faith in stocks, I���ve adopted a mechanical approach to investing, primarily using stock index funds. No more trying to outsmart the next guy. I don���t have to time everything exactly right or worry about where shares will bottom. I have an allocation target for stocks as a percent of my total portfolio, along with preset trigger points at which I intend to buy more during substantial market dips.

Pretty much all I need to know during a downdraft is, how far is the market from its peak?

Sure, I subscribe to The New York Times, Morningstar and even Barron���s. I take advantage of the office subscription to The Wall Street Journal. I���ve got a wicked FinTwit feed of great financial journalists and pundits. And, of course, I read HumbleDollar.

Still, as I make stock market decisions, it���s amazing all the things I don���t have to read. By avoiding overconsumption of financial news and advice, I keep my emotions in check and insulate myself from the temptation to put too much stock in predictions that seem persuasive in the moment.

I don���t need to know how long bear markets have lasted historically, or their average decline, though I���m grateful to those who produce such information. I also don���t need to know what the market expects from future Federal Reserve interest rate moves. I don���t even need to know whether inflation has peaked or whether market participants believe inflation has peaked.

For instance, on Aug. 2, I learned from my Twitter feed that Credit Suisse says ���war is inflationary��� and the federal funds rate is headed as high as 6%, while Bank of America says virtually the opposite, forecasting that 10-year bond yields are headed back down toward 2%. Both predictions potentially have big implications for stocks, but are pretty much worthless for making investment decisions.

What am I to do with suggestions that the dollar will supposedly soar inexorably, particularly against the yen, except perhaps wish I could afford another overseas trip? To change my approach on the proposition that the dollar will continue rising���for instance, by selling a Japan fund that I invested in last year���would be speculative. The good news: The fund is actually holding up relatively well in 2022.

I do admit to an interest in which market segments and asset classes appear inexpensive compared to others. One of the few market bets I���m making is on small-cap value stocks, where I have a modest tilt both in the U.S. and overseas, including in Japan.

But these days, I hunker down when the stock market is falling. I try to limit my intake of bad news���and there has been so much this year���so it���s easier to be patient and stay the course.

All I need is the aforementioned faith that company shares are almost certain to continue outpacing all other asset classes���as well as inflation���over the long term, as they have for centuries.

Having that conviction, I follow a pre-established plan to buy the dips at set thresholds as the market stair-steps down. Substantial correction? Put more in. Deeper slide? Buy. Bear market? Don���t sweat it. Trim one of my Treasury funds and buy again.

All of which I���ve done this year. Younger me would have been obsessed with buying at the very bottom. But such a pursuit is vain and exhausting���and success could only come from dumb luck. My more stoic approach to market swoons should prove rewarding enough in the long run.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart��and check out his earlier articles.

William Ehart is a journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. In his spare time, he enjoys writing for beginning and intermediate investors on why they should invest and how simple it can be, despite all the financial noise. Follow Bill on Twitter @BillEhart��and check out his earlier articles.

The post Don���t Sweat It appeared first on HumbleDollar.

August 9, 2022

We All Want an A

The reality: While my exercise habits are excellent, my eating habits leave something to be desired. But I'm not anxious to discuss this reality with my doctor, hence my pre-checkup regimen. I don't want a lecture. Instead, I just want the doctor to tell me everything is fine.

That brings me to the response to HumbleDollar's Two-Minute Checkup, which was launched earlier this month. From��the emails I've received and from the comments I've read, both on this site and elsewhere, many folks found the feedback they got from the calculator helpful. But not everybody liked their results.

The Two-Minute Checkup is designed to analyze a user's financial life based on minimal information���the sort of stuff each of us typically knows off the top of our head. Based on no more than nine inputs, the calculator offers suggestions on 10 financial topics.��I like to think the Two-Minute Checkup is unique, but the financial logic underpinning it is pretty conventional. You can get more details��here.

If the calculator's logic isn't the problem, what is?��After sifting through the comments and emails, it seems many of the calculator's critics are bothered that they can't input the value of their Social Security, their pension and their home. That, in turn, is driving two key sets of complaints:

Some folks still in the workforce aren't happy with the gauge of their financial fitness and with the suggested retirement savings rate.

Some retirees aren't happy with the calculator's spending feedback.

Needless to say, some of the complaints are valid. But they also say a lot about human nature.

For those in the workforce, the Checkup gauges their financial fitness by looking at whether they're on track to save 12 times their annual salary or wages by age 65. If their portfolio is that large, it should be able to sustain retirement withdrawals equal to half of their old salary.

But amassing 12 times income is a tough target to hit, and most folks don't have anywhere near that much saved by the time they retire. In fact, according to a 2015 study by the National Institute on Retirement Security, 60% of those close to retirement age have a net worth equal to less than four times their income. Moreover, the study's authors describe their definition of net worth as "generous," in part because it includes home equity.

Why doesn't the Two-Minute Checkup ask about home equity? For starters, it's a number folks may not know off the top of their head and, even if they think they do, there's a good chance their estimate is wrong. More important, a home isn't easily turned into a retirement income stream. Many retirees are reluctant to downsize or take out a reverse mortgage and, even if they take those steps, they'll only be able to spend a portion of their home equity. Yet, from the comments and emails I've received, it seems some users would like their home equity to count toward their financial fitness���because it would make their finances look better.

What about pension income? Even if workers are entitled to a pension, they may be uncertain how much they'll ultimately receive because they're still accruing pension credits, so this is another number they won't know off the top of their head.��Still, if you're eligible for a pension, you'll be in better shape than the financial fitness gauge suggests, and that caveat is built into the feedback that the calculator delivers.

What if you're retired? At that point, you will indeed know how much your pension pays, as well as how much you're receiving from Social Security. Suppose you're a retiree age 51 or older with $350,000 in your financial accounts. Here's the spending feedback that the calculator would give you:

Based on your total savings, you should probably limit this year's total portfolio withdrawal to between $14,000 and $17,500. If you have other income from, say, an annuity, part-time work, a pension, rental properties or Social Security, that could provide additional spending money.

This is when I really started scratching my head. If folks are receiving a pension or Social Security, they know how much they're getting from these two sources. But it seems some retirees still want to input that information into the Two-Minute Checkup, so it's then repeated back to them. Obviously, the calculator wouldn't be telling them anything they didn't already know. So why do they want this information included? Yes, it would make the calculator's feedback more comprehensive. But I suspect it would also make some retirees feel better about their finances���because their retirement savings are on the skimpy side.

I'm not interested in unnecessarily feeding folks' financial worries. Far from it. That, in part, is why��I'm paying close attention to user comments, with an eye to improving the Two-Minute Checkup. I'd like to find some way to incorporate information on Social Security and pension income��without getting away from the calculator's original objective, which is to provide feedback across a user's entire financial life based on minimal input.

But while I don't want folks to feel badly about their finances, I also don't want the calculator to give them false reassurance. Yes, your home may be valuable, but it typically shouldn't count as part of your retirement savings. Yes, Social Security is a wonderful income stream, but it isn't enough for a comfortable retirement. Yes, receiving a pension is great. But if you don't have a pension or your pension isn't all that generous, aiming to save 12 times income is a worthy goal.

My hunch: The users who like the Two-Minute Checkup are being told they're in good financial shape, while some of those who are unhappy with the calculator don't like their results. I get it. Nobody likes critical feedback. We all hate those annual employee reviews. We don't like it when our spouse comments on our driving. Like me when I go for my annual physical, we just want to be told everything is fine.

But if we're to improve, we need to keep an open mind.��Haven't yet tried the Checkup? Give it a whirl���but don't expect to get an A.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.The post We All Want an A appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Don’t Be Like Joe

I HAD SOME GOOD bosses and some bad ones over my 35-year career. The worst was Joe. He tried to intimidate you. I once overheard him tell another manager that he likes to ride his employees and dig his spurs into them.

What was so terrible about Joe? It wasn���t that he was tough on employees. It was that he was unfair. You incurred his wrath whether you deserved it or not.

I remember the first time I attended a meeting held by Joe. He started shouting at another employee. He stopped for a second to catch his breath, and then turned to me, pointed his finger and said, ���I���m going to get to you next.��� It was Joe���s way of using fear to try to get the maximum effort out of his employees.

Luckily, I was in my 40s when Joe was my boss. By that time, I was a seasoned employee who wasn���t easily intimidated. I���d also been contributing to the pension plan for almost 20 years. I wasn���t about to throw that away and quit because of Joe���s outbursts.

After Joe retired, there was a major reorganization within the company. Kevin was now my boss. He was one of the best managers I ever worked for. He was the antithesis of Joe. He showed you respect and treated you fairly. In return, employees gave their best effort. I never heard anyone say a bad word about Kevin. That���s how much he was liked by his employees.

Although I didn���t report directly to him, he took an interest in everyone under his leadership. One day, Kevin pulled me aside in the factory. He said, ���I appreciate the outstanding work you���ve done for us. I���m also embarrassed at what we���re paying you. You���re underpaid for what you're doing. I'm going to fix that.���

What was so remarkable about that conversation: I���d never complained or asked for more money, but it didn't matter. Kevin supported all his employees. He was there for you.

I had no idea what my coworkers were making. Kevin was in a better position to know whether I deserved more compensation. He gave me a promotion and an 18% pay raise. Two months later, we had our annual review. I was given another generous raise. Within a short period, I was making almost 25% more money.

When the boss I reported to informed me of my new salary, he asked if I was going to buy a new car. At the time, I drove a late model Toyota Camry. But I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the money. Save it. I continued to max out my 401(k) plan contributions. When I reached age 50, I added regular catchup contributions. I also increased my contributions to my taxable Vanguard Group account.

When I look back, the person who had the biggest impact on my financial security was my manager, Kevin. That���s why it���s important to not only find the right job, but also the right boss.

The post Don’t Be Like Joe appeared first on HumbleDollar.