Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 183

October 18, 2022

Puppy Love

SIX YEARS AGO, I made one of the worst investments of my life.

I got a dog.

Ignoring the age-old advice to never invest in anything that eats, I signed up for a purebred German shorthair pointer puppy. I thereby locked myself into an indefinite stream of future cash outflows in the form of dog food, treats, supplies, annual checkups, vaccinations, flea and tick treatments, heartworm pills, procedures and other expenses required for keeping man���s best friend healthy and happy.

What can I say? We all have our moments of irrational exuberance. For the record, I���m also a holder of AT&T, a stock that I bought for its attractive dividend yield but which, alas, has proven to be a classic value trap.

As for the dog, well, I spend a fair bit of time on my own and, as I got older, I wanted a companion that would match my active lifestyle. A neighbor was planning to breed her beautiful, sable-coated dog. I���d never had a pointer before and thought I���d try one.

My life, and my pocketbook, have never been the same.

Now, let me just say that I love my Cassie dearly and I wouldn���t give her up for the world. She���s sweet, smart, funny and loyal. She and I are stuck together like white on rice, and our bond only grows with each passing day.

That doesn���t hide the fact that this dog is expensive, not to mention exhausting. Just feeding her costs me about $20 a week���all that energy of hers burns calories, after all. I knew going into the transaction that pointers were high-strung. But like that AT&T stock, you don���t really know what you���re getting into until you have it in your hand.

I don���t think I���ve sat down for more than an hour at a time since I brought Cassie home. When I���m not taking her for walks���or more precisely, when Cassie isn���t taking��me��for a walk���I���m cleaning up the trail of destruction left behind by my 65-pound canine tornado.

Zoomies are the worst. Watch out as the Cassie Express bounces from room to room, knocking over lamps and potted plants and anything else that���s in the way. Owning a purebred sporting dog is like having a thoroughbred horse in your house.

If you hear galloping, you stand back and hope you don���t get run over. Cats, squirrels and doorbells put her into a frenzy. Recently, I replaced a front screen door that she busted through when the Amazon Prime truck came by to make a delivery. The poor guy was terrified. But once outside, Cassie just wanted to give him kisses.

Even worse than the mishaps are all the medical emergencies that come with owning a high-energy dog. Like the time Cassie caught her ear on brambles while chasing bunnies through a briar patch and came back to the house bloodier than a pirate on the losing end of a mutiny.

A dog���s ear, I discovered that day, is filled with tiny blood vessels which, if severed, bleed like a sieve. The vet had to knock poor Cassie out to stitch her up, all of which resulted in a $350 hit to my pocketbook.

These surprise bills weren���t so bad when I was working. But for an��early retiree��living on a fixed income, they can break the best-planned budget. And it never ends, that���s the thing.

Every day, when you wake up, the bills and responsibilities lie in front of you: the feedings, the walks, cleaning her paws when she comes inside so she doesn���t dirty up the house, wiping up her drool after she drinks from the water bowl. Some days, you just want a break, but the only break comes when you go on vacation. Then you have to kennel her and that���s not cheap. Figure on paying at least $400, including tips, for that week of freedom.

I found myself mulling all this over one evening last week while taking Cassie out for her 18th walk that day. I was in a bad mood because it was hot outside and the last thing I wanted to be doing was sweating up another shirt while Cassie pulled me around the neighborhood. Despite spending hundreds of dollars on training, I still haven���t broken her of the habit of pulling on her leash.

Why do people do things like this, I wondered. Why do otherwise rational people commit themselves to taking care of living creatures that suck up their precious time and money?

We do it for the companionship, yes���for the love and richness that a pet adds to our lives. But man, does it cost us in both money and time. I suppose the same could be said about having kids. According to��recent research, it costs upward of $300,000 these days to raise a kid, not including college. At least the kid eventually goes off on his own and sends birthday cards���well, maybe. A dog is constant work and expense until death do us part.

Back at the house after the walk, Cassie took a long drink from her water dish and collapsed onto the floor in a panting pile of dog. I felt bad for grouching at her during the walk and got down on the floor next to her.

She squirmed and pawed at me for a few minutes before finally settling. Music was playing in the background. I stroked Cassie���s silky ears and rubbed her belly while telling her what a good girl she is. She just looked back at me with those piercing amber eyes that said���you���re my person, Dad, and always will be.

Yeah, it���s worth it, I thought. Every penny.

Now, as for that AT&T stock���.

James Kerr led global communications, public relations and social media for a number of Fortune 500 technology firms before leaving the corporate world to pursue his passion for writing and storytelling. His debut book, ���The Long Walk Home: How I Lost My Job as a Corporate Remora Fish and Rediscovered My Life���s Purpose,��� was published in 2022 by Blydyn Square Books. Jim blogs at PeaceableMan.com. Follow him on Twitter @JamesBKerr and check out his previous articles.

James Kerr led global communications, public relations and social media for a number of Fortune 500 technology firms before leaving the corporate world to pursue his passion for writing and storytelling. His debut book, ���The Long Walk Home: How I Lost My Job as a Corporate Remora Fish and Rediscovered My Life���s Purpose,��� was published in 2022 by Blydyn Square Books. Jim blogs at PeaceableMan.com. Follow him on Twitter @JamesBKerr and check out his previous articles.The post Puppy Love appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 17, 2022

Make More Money

STEVE MARTIN HAD a joke on “how to become a millionaire” during his 1970s stand-up routine. “First,” he would say with a mock-serious glare at the audience, “get a million dollars.”

There are piles of books written about how to invest your money. Far fewer explain how to make money in the first place. To balance the scales, I’ll offer this suggestion: If you’re still working, this would be a great time to interview for a new job. You might be surprised at how much money employers are offering.

I made three moves in six years when I was a cub reporter in the 1980s. I went from $6,700 a year to $30,000. I know, that’s not exactly a king’s ransom, but that’s why I changed jobs so often. I could have advanced, step by step, at any one place. Not every industry works this way, but there’s a tradition in journalism of working your way up from the boonies before settling into a “forever” job in the big city. But instead, I took the elevator up—in pay and responsibilities.

This is one of those rare times where there seem to be job opportunities in every corner of the economy. There’s barely more than one unemployed worker for every two job openings. Job vacancies, as a percent of all positions open and filled, were close to a 20-year high at 6.2% in August, while the unemployment rate was at a 50-year low of 3.5% in September, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Just as with Springsteen tickets, labor costs can jump unexpectedly high when demand outstrips supply. The typical job changer was rewarded with 9.7% higher pay—after accounting for inflation—according to a 2022 study by the Pew Research Center. By contrast, workers who stayed put saw their pay shrink by 1.7% in real terms over the same period, April 2021 to March 2022.

These days, hiring managers must fling cash—plus promises of remote work—at potential hires in a do-or-die competition for labor. Many restaurants and stores have closed their doors because they can’t hire enough workers.

And the labor shortage isn’t just in retail and restaurants. This August, there were almost 1.9 million open positions in professional and business services, 1.9 million in education and health services, and 347,000 in finance and insurance, says the Bureau of Labor Statistics. These are the sorts of jobs that could pay a mortgage.

I even saw ads for newspaper reporters this summer—the white rhino of job openings. One was to work the cop beat on weekend nights in Lewiston, Maine. I didn’t apply. A few weeks of that could give me PTSD, though also great stories to tell at cocktail parties.

Like peak housing, no one can say how long peak labor might last. Perhaps not long if the Federal Reserve gets its way and succeeds in driving up unemployment next year. I know the Fed is supposed to take away the punchbowl when the party gets going, but putting people out of work seems cold. I don’t wish Jerome Powell luck with it.

Of course, switching jobs is a big decision and there are real risks. The No. 1 risk is that you won’t like the new place. There’s also the risk that, if the economy tips into a recession, the last hired will be the first fired. On top of that, you’ll lose all your work buddies at the current job, and start as the new kid somewhere else. Maybe it’s no wonder that many workers who have good jobs with generous benefits prefer to stay put.

Still, if you’re just starting out—or don’t like your current job—this might be the time to test the waters. A higher rate of pay tends to persist, year after year, throughout a career. It might not make you a millionaire, but maybe you could afford Springsteen tickets. Here’s hoping.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.

Greg Spears is HumbleDollar's deputy editor. Earlier in his career, he worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger’s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, Greg spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. Greg is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder. Check out his earlier articles.The post Make More Money appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 16, 2022

Almost Done

LAST WEEK’S INFLATION report did the bulls no favors. The latest reading on the Consumer Price Index showed a larger-than-expected September rise, mostly due to housing data, which tend to respond slowly to higher interest rates. Then came Friday’s University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey, which showed an unexpected jump in inflation expectations over the next year and next five years. Result: Bond yields climbed and stocks finished the week lower.

But there’s also good news: Among economists, expectations for 2023 inflation look nothing like what we’ve endured over the past year. Goldman Sachs, for instance, expects both headline CPI and the core rate—which removes the volatile food and energy components—to be under 3% for the 12 months through December 2023. Analysts at Bank of America forecast full-year CPI of 2.2% for 2024.

Meanwhile, it’s likely the Federal Reserve will be almost through its rate-hike cycle in less than two months. Following the Dec. 14 meeting, the Fed’s policy rate should be near 4.6%, based on market pricing, with a peak rate near 5% expected in next year’s second quarter.

Indeed, by the middle of 2023, there could be mounting job losses as the economy stumbles amid much tighter borrowing conditions. Bank of America forecasts a rising unemployment rate and upward of 200,000 jobs lost per month in next year’s second quarter. Other research firms, while perhaps not predicting a recession, are at least lowering their S&P 500 earnings outlook.

Given a steep deterioration in economic activity and corporate profits, the Fed might be forced to put an end to its rate increases. While much depends on what’s happening to CPI, if the economy does indeed slow sharply over the coming quarters, the Fed may even have to cut rates a little late next year. But don’t expect any hint of that dovish turn since the very words used by the Fed are part of its rate policy.

The upshot: The headwind of rising interest rates will soon be over and, for stock investors who are patient just a little longer, better days are likely at hand. It’s a good reminder that stocks have historically been a good way to combat inflation.

The post Almost Done appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Hold Opinions Loosely

Judging by his track record, this approach seems to work. Even in his 90s, Buffett believes there���s always more to learn and that more knowledge will lead to better investment results.

At the same time, investors often invoke expressions that suggest otherwise: No one has a crystal ball. No one can see around corners. Be careful of unknown unknowns. In other words, all the reading in the world can���t help you predict the future.

Author and retired investor Nassim Nicholas Taleb has written several books on this topic. His view: Investment markets may be��somewhat��predictable. But the most important events���what he calls ���black swans������are entirely unpredictable, and they can be devastating. Even when we think we���re seeing repeatable patterns in investment markets, Taleb says we���re really just being ���fooled by randomness.���

Taleb uses the analogy of a billiards table: When a player, even a novice, hits the first ball, he can be pretty sure which way it���s going to go. A skilled player might be able to control what will happen when the first ball hits the second. But beyond that, it���s anyone���s guess. Things are just too random. Taleb sees the economy and investment markets the same way. Because there are so many variables at play, it���s nearly impossible to know how things will turn out.

I��noted��last week, for example, that Tesla���s success in the electric vehicle market can be attributed to a number of factors that were unpredictable. Perhaps most significant: Toyota���the largest car maker in the world���has been skeptical of electric vehicles and, as a result, has chosen to stay largely on the sidelines. That was a decision no one could have predicted. In fact, it���s the��opposite��of what many expected. And yet, it���s added immeasurably to Tesla���s market value.

If it���s difficult to know where any one company is going, it���s even more difficult to know where the overall economy is headed. We���ve seen this in living color over the past few years. At least five events couldn���t possibly have been predicted, no matter how much research an investor had done.

First was the initial emergence of COVID-19. While the risk of a global pandemic was generally understood by experts, no one knew that it would occur in 2020 or what its effects would be. Indeed, there had been coronaviruses before, but none had spun out of control like this one.

As we know now, the government���s response, in the form of stimulus payments and other programs, led to an inflation spike. Many foresaw this, but I don���t think anyone could have predicted how the Federal Reserve would respond.

Throughout 2021, as inflation climbed, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell assured investors that it was ���transitory.��� Because of that, Powell and his colleagues at the Fed declined to take action. It wasn���t until November of last year that Powell��acknowledged��that perhaps inflation wasn���t going to be transitory. ���It���s probably a good time to retire that word,��� he said. That was the second unexpected event.

The third event: After denying that inflation was a problem, Fed officials did an abrupt about-face and began hiking rates in��dramatic��fashion.

The fourth event: Russia���s February invasion of Ukraine. Because Russia is a major energy exporter, and because Ukraine is a key grain producer, commodity prices spiked, contributing to an inflation rate that was already climbing.

The fifth and final unexpected event: China���s stubborn pursuit of a ���zero COVID��� policy. By continually shutting down major cities���and their factories���China���s autocrats have further contributed to rising prices by prolonging product shortages.

To be sure, the past few years have been unique,��but they aren���t unusual. The reality is, unexpected events occur all the time. As investors, what should we make of this? On the one hand, knowledge and expertise must count for something. It���s hard to imagine Warren Buffett is wasting his time when he sits and reads 500 pages a week. At the same time, no amount of research would have helped any investor���no matter how skilled or experienced���to predict these events.

So far, I���ve been talking only about predictions. But a particularly depressing data point calls into question even the facts we think we know. In the early 2010s, scientists discovered that the results from a surprisingly large number of research studies couldn���t be replicated. This has been found in��diverse fields, from psychology to medicine to economics. In some fields, fewer than a quarter of studies can be reproduced���to the point that this phenomenon is now known as the ���replication crisis.���

Where does this leave us as investors? I have a few suggestions. First and maybe most important, see investment markets for what they are. Economics is not a science in the same way that chemistry or physics is. That���s because, as Taleb explains, there are simply too many variables at play.

But that doesn���t make investment research worthless. It just means we need to adopt the right posture when looking at investment data. We can���t view market-related information��as definitive. Instead, we need to see it only as a point of reference. Because of that, we should view the future in terms of ranges and probabilities���not absolutes.

In economics, there���s no such thing as an E=mc2��type formula. But there are approximations. For instance, the relationship between interest rates and bonds, as I��discussed��recently, is fairly reliable. It���s worth reading and learning, as long as it���s done with the understanding that this information can help us make educated guesses,��not guaranteed predictions.

How can you put this philosophy into practice?��Unless there���s a clear and present danger, try to avoid making big changes all at once.��Thinking of changing your asset allocation, paying down debt or starting a new business? See if there���s a way you can implement these decisions in half-steps. Similarly, investors should always be looking for ways to hedge, to diversify or to split the difference on big decisions. That can be invaluable if things turn out differently than expected.

A related point: Because investment markets are so unpredictable, it���s important to develop a plan that���s flexible���one that will work whether the stock market is up or down. That can help you stick with��your��plan throughout market cycles, through good news and bad.

It���s a balance, though. Yes, you want to stay consistent with your investment plan, but you don���t want to be overly wedded to it. There���s a point where consistency can cross over into stubbornness.

Aesop talked about the difference between a giant oak tree and a lowly reed. While the tree is bigger, the reed is more flexible. This gives the reed an advantage during storms: It can bend, while the oak, because it's��rigid, might simply break. How can you apply this kind of flexibility to your finances? There���s the expression that one should ���hold opinions loosely.��� I see this as a helpful idea. If we aren���t too adamant with our opinions, it���s much easier to avoid cognitive dissonance when we���re exposed to contrary opinions.

A final thought: I don���t know what Warren Buffett reads, but my guess is��he casts a wide net. Because investment markets are influenced by such diverse factors, I recommend this same approach. Look at news and data the way you might look at puzzle pieces on a table. At first, it���s hard to see the big picture. But the more pieces we collect���and the more time we spend thinking about how things might fit together���the better informed we���ll be as investors. No investment puzzle will ever fit together perfectly, but that���s okay. After all, even Warren Buffett���at age 92���is��at his desk every day working on these puzzles.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.The post Hold Opinions Loosely appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 15, 2022

Hooray for Inflation?

IF YOU���RE AN OWNER of financial assets, inflation doesn���t offer much reason to cheer. Lost 16% on your bonds this year? Once you factor in inflation, the hit to your bond portfolio���s real, inflation-adjusted value would be more than 20%.

By contrast, if you���re a borrower, inflation is a bonanza. Suppose you owe $2,000 every month to the mortgage company on your fixed-rate loan. As inflation climbs, your mortgage payment stays the same���but, if your income rises with inflation, it's now a whole lot easier to make that monthly payment.

That raises an intriguing question: Who���s the biggest beneficiary of this year���s inflation? According to the Federal Reserve, households have $18.6 trillion of debt, businesses have $19.5 trillion, and federal, state and local governments have almost $29.6 trillion.

Before you declare, ���Of course, the government is the big winner,��� recall that this $29.6 trillion debt is owed by all of us collectively. In other words, your Treasury bonds may be worth less because of inflation, but your share of government debt has also fallen in inflation-adjusted terms.

In fact, after factoring in the 5.9% inflation we���ve seen in 2022���s first nine months, the federal government���s $26.3 trillion debt has effectively shrunk by some $1.5 trillion���more than was added by the $946 billion annual budget deficit. But that silver lining may soon lose its luster: With Treasury yields on the rise, the federal government will be paying significantly more to service its massive debt.

Household and business debt are also now less burdensome in inflation-adjusted terms, a bonus for profligate consumers and those with mortgages, and also a potential help to corporations and their shareholders. Still, since the 2008-09 Great Recession, even as the federal government has gone on a borrowing binge, households and corporations have been relatively debt averse, so inflation isn���t as big a benefit as it might have been.

So, should we cheer for inflation? Absolutely not. It���s a disruption to the economy, a hit to consumers and a tax on savers. But make no mistake: There are some winners. With no debt and a fair amount of financial assets, I���alas���am not among them.

The post Hooray for Inflation? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 14, 2022

My Investment Sin

I'LL CONCEDE IT'S HARD to justify—but I don’t believe it’s 100% unjustifiable. At issue: my strategy of overweighting stocks during big market declines. I did so in 2007-09 and early 2020, and I’m doing so today.

“Market timer,” cry the critics. That, in financial circles, ranks as pretty much the nastiest insult you can hurl, even worse than calling someone an "annuity salesman."

Today, if I ignore the money I’ve set aside for a big home remodeling project, my Vanguard Group account is at 86% stocks, above my 80% target. I started the year at 78%. Since then, I’ve been regularly moving money from my short-term bond funds to my stock funds, so I've not merely offset 2022’s fall in share prices, but also driven my stock holdings six percentage points above my target.

All that money has gone into total stock market index funds. I've also converted $80,000 of my traditional IRA to my Roth, effectively increasing my stock exposure when calculated on an after-tax basis. Even as I try to make the most of 2022's stock market slump, I can't say I'm thrilled about my losses. But I also know I won't be tapping my portfolio for income for at least a few more years. How can I justify this sort of active asset allocation? Let me offer three contentions.

This isn’t market timing. I’m not making a big all-or-nothing bet based on a market forecast, but rather responding to what the market has already done. Of course, I hope—and indeed fully expect—that the broad stock market will eventually recover its losses and go on to notch new all-time highs. But I have no idea when that’ll happen. That's why I haven’t made some big onetime shift from bonds to stocks, which is what a market-timer would do. Instead, I just keep buying more as share prices fall, and that’s how I’ve ended up overweighted in stocks.

I’d argue this is similar to rebalancing, but a tad more aggressive. When we rebalance, we also react to what the financial markets have done, moving money into parts of our portfolio that have become underweighted relative to our targets. I’m just taking this a step further, not just getting stocks back to my portfolio’s target stock percentage, but opting for an overweighted position to take advantage of the steep decline.

Markets overshoot. In academic circles, this is a point of some debate. If financial markets are efficient, stock and bond prices should always reflect underlying value.

I believe financial markets are indeed reasonably efficient. It’s why most active money managers fail to beat their benchmark index, and it’s why market forecasters show no more prescience than folks guessing heads or tails on a coin flip.

Still, every so often, large numbers of investors seem to fall victim to collective hysteria—can anyone say "meme stocks"?—and share prices become unmoored from their intrinsic value. This appears to happen during major market declines, when fear runs rampant, and that’s why I’m willing to overweight stocks.

Market returns revert to the mean. In academic circles, this is also a point of some debate. If stock and bond prices follow a random walk, what happens next year should be unrelated to what’s happening this year. In other words, if stocks fall 25% this year, that makes no difference to the odds of whether they’ll fall 25% next year, and the year after that, and the year after that.

I think this is nonsense. Yes, what happens to stocks on Monday tells you nothing about what will happen to share prices on Tuesday. But if share prices fall for years on end while corporate earnings keep growing, eventually stocks will become an unbelievably compelling value. What if, instead of growing, corporate earnings shrink year after year? In that case, something disastrous is happening in the world—and, frankly, it won’t matter what you own.

To be clear, I’m not betting on reversion to the mean by any individual stock, or market sector, or even country. Instead, I’m betting on reversion to the mean by the global stock market. Indeed, my portfolio's single biggest holding is Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund (symbol: VTWAX). What if I was less diversified? I suspect I’d also be less inclined to buy at times like this.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post My Investment Sin appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Runner’s High

I'VE RECENTLY BEEN reading and listening to health experts who study the brain chemical known as dopamine. I’m no health expert and I don’t claim any specialized knowledge on the subject, but I’ve learned dopamine is widely considered to be the “pleasure chemical.”

Think about the feeling in between bites of chocolate cake, when we know just how good that next bite is going to be. As we anticipate our reward, our dopamine spikes, and then eventually regresses toward normal.

There’s an endless number of actions that can stimulate dopamine spikes in our brains. Most are around pleasure or the avoidance of pain. Indeed, in the developed world, access to dopamine stimulants is abundant. Some would say it’s obscene. At any time, we can have almost any food we want. At any time, we can have an endless supply of any drug of choice. At any time, we can watch our favorite movie or show. At any time, we can buy anything we want—even things we can’t truly afford.

Never in human history has it been so easy to obtain short-term pleasure and so easy to avoid pain. Hot? Turn up the A/C. Cold? Turn up the heat. Need something? Buy it. Bored? Go on YouTube, Netflix or Hulu.

Just because we can obtain pleasure and avoid pain at will, should we? There’s an interesting idea that I’ve latched onto—one that’s critical to long-term happiness: We should earn our dopamine.

This idea is best demonstrated by the rising popularity of ultra-marathons, cold showers, perilous mountain hikes and long bicycle rides. These undertakings are not pleasurable. They are painful much of the time. People are looking for a way to pursue difficulty intentionally.

Why would someone choose pain and suffering? Why not kick your feet up and watch a movie instead of going for a run? It’s not that these people love pain. Rather, it’s that they love the way dopamine feels. All these difficulties release rushes of dopamine. The difference in these dopamine spikes, versus, say, scrolling through your social media feed, is that these rushes are long-lasting.

A spike in dopamine from your iPhone is typically brief. Too many short spikes and you’re left with a crash. If you’ve ever spent too long on your phone and then realized it, you know this feeling. You’re not even sure why you kept scrolling.

With arduous tasks like an ultra-marathon, our dopamine increases last, sometimes for hours. This is the feeling you get after jumping in cold water, finishing a demanding project or completing a tough workout.

All these efforts release a sustained level of dopamine that’s not followed by a crash. You find clarity. You find peace. You find bliss. Isn’t that what we’re all pursuing?

The post Runner’s High appeared first on HumbleDollar.

That First Step

I WAS IN NEW YORK visiting my sister a few weeks ago when I saw a sign that read "Delay = Denial." For me, that simple yet profound statement immediately struck a chord.

The sign was referring to climate change. Yet I could see how this plays out in other areas of my life. I began asking myself, what causes us to delay or deny the obvious?

I reached one clear conclusion: complexity. The things we tend to delay the longest are the things we believe to be too complicated. The earth is the most complicated system in our lives, so it makes sense that we pause when we think of something as overwhelming as climate change. It���s much easier to deny it���s happening and to delay doing anything about it.

I see this occurring in other areas of our life. Think of the last time you ordered furniture from Ikea. If you���re like me, you probably set that big cardboard box in a corner of the house for a couple of weeks, denying its very existence until you���re about to have guests. We all want the finished product but sometimes getting there just feels too complicated, so we deny and delay.

When I first wanted to get my finances in order, everything felt complicated. It seemed impossible to deal with all the issues involved. Just think of the questions we have to grapple with:

How do I budget?

What are my savings goals?

Do I have enough to buy a house?

Is my debt bad or good?

How long will it take to pay for my house?

How do I save for retirement?

Can I save for retirement?

What investment accounts do I need to open?

How do I pay my student loans?

Do I have the right insurance?

Once we have some experience with money, none of these questions seems overly complicated or hard to answer. But for anyone just starting out, each question feels like a mountain with a summit that can���t be seen from the ground.

Along with the steep climb, we have to master all these fancy financial terms like mortgage, amortization, HSA, 401(k), IRA, Roth, APY, APR, premiums, liability, fiduciary, credit, net worth and so on. This compounds the problem. Not only do I not know what to do, but also I can���t even have an intelligent conversation with someone who might help because I don���t understand the language. It all feels impossible.

Result? I would just check out. I would tell myself, "I don't have time to handle all these things, and it���s not that bad anyway. I���m young and I have plenty of time. Next weekend, for sure, I���ll work on my budget. I���ll finally set up that savings emergency thing."

The thought of doing any of it was too overwhelming, so I denied there was an issue. That led me to never actually doing anything���until we had personal finance classes at church. We used Dave Ramsey���s Financial Peace University course. It provided a framework to process the various financial questions I had. It brought everything down to the basics. It removed the noise and allowed me to narrow my scope, focusing only on the most important things.

Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money, explains why this approach works so well: ���If you���re going to act on a problem that is monstrously complex and uncertain, the stripped-down, rules-of-thumb response is not only good enough. It can be superior to tripping over yourself in pursuit of something that appears marginally more accurate���. [S]imple ideas are not dumbed-down ideas. They are often complex solutions gift wrapped for you in a way that makes their application practical and sustainable.���

We gain confidence when we know exactly where to begin. It allows us to take control and make plans. That���s why something like HumbleDollar���s Two-Minute Checkup is such a great tool. It gives you confidence.

The next time you���re faced with a complex and uncertain decision, your best bet is not to run a bunch of Monte Carlo simulations. It���s probably better to use a simple rule of thumb and then take action.

And the next time you talk to folks who are just getting started, try to remove the complex words and tactics. Give them a simple rule of thumb that they can put into action immediately. I know that helped me a ton.

Kelechi Iwuaba is an engineer, a Nigerian-American and a self-taught finance nerd who lives in Atlanta. He loves talking about all things finance to anyone willing to listen. In his free time, Kelechi creates finance videos, records the ���Rambling Mind��� podcast and writes a blog. He loves volunteering at his local church and playing soccer at every opportunity. Follow him on Twitter @KelechIwuaba. Kelechi's��previous article was Once Upon a Dime.

Kelechi Iwuaba is an engineer, a Nigerian-American and a self-taught finance nerd who lives in Atlanta. He loves talking about all things finance to anyone willing to listen. In his free time, Kelechi creates finance videos, records the ���Rambling Mind��� podcast and writes a blog. He loves volunteering at his local church and playing soccer at every opportunity. Follow him on Twitter @KelechIwuaba. Kelechi's��previous article was Once Upon a Dime.

The post That First Step appeared first on HumbleDollar.

October 13, 2022

Taking It Slow

IT���S A QUESTION FOR the ages���or perhaps the aged. Since the day the first pension was promised, someone has wanted to know the answer. If you look hard enough, I���m sure it���s referenced in the Bible.

I���m writing this article not to help you answer the question, but to help me answer it. You see, my old employer, Exxon Mobil, has offered me a ���onetime lump-sum opportunity.���

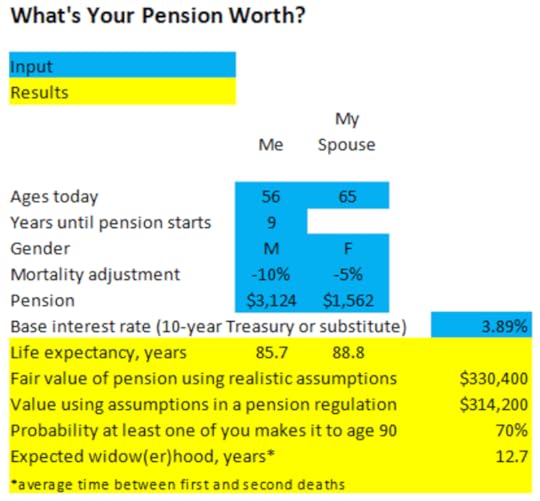

I have the option to take a single lump-sum payment of $335,641.85 starting Nov. 1, 2022, or a joint life annuity payment of $3,124 a month starting March 2031, with my wife receiving 50% of that sum if I predecease her. I���m age 56, my wife is 65 and we don���t have children.

When I retired a few years ago, Exxon Mobil didn���t give me the lump-sum option because I wasn���t yet age 55. This didn���t prevent me from thinking about it, not least because that���s all my older colleagues wanted to talk about. Every one of them, when they retired, claimed to have taken the lump sum. Most of them mentioned how historically low interest rates had made the lump-sum option a ���no-brainer.���

Still, the New Yorker in me always wondered, ���Why would Exxon Mobil give retirees such a great deal?���

To be honest, my cynicism might have been due less to the location of my birth and more to William Baldwin, a Forbes columnist. He wrote an article in January 2016 that mentioned that, ���If a lump sum is offered (as it is for roughly half of pensions), it is more likely than not a rotten deal.��� While federal law requires the offer to be fair, some employers use bond rates and mortality tables that may not necessarily be annuitant friendly.

Baldwin offered a calculator that cut through all the numbers and computed a ���fair value.��� It also allowed me to vary the inputs, so I could better understand what it all meant and avoid the black box syndrome. A few years ago, when my wife was offered the option of a lump-sum payment by her former employer that seemed a little light, the calculator only confirmed our suspicions.

When I used the calculator to analyze my ���lump-sum opportunity,��� it returned the following results:

With Exxon offering me $335,641.85, above the $330,400 fair value computed by the calculator, it appears the offer is a little more than fair.

Still, after reading what HumbleDollar��had to say on the matter, I decided to take a look at the issue from another angle. I contacted a number of brokers, asking for monthly income quotes for a 50% joint-and-survivor annuity that commenced on my 65th birthday, assuming I made a single payment of $335,641. This, of course, is what Exxon Mobil is offering me.

Even though I knew the exact annuity I wanted to buy, the process was quite complex, filled with terms like guarantee type, period certain, QLAC, return of premium and so on. Both ImmediateAnnuities.com and Schwab quoted some $3,000 a month, with $1,500 a month going to my wife, assuming I die first. The upshot: The Exxon Mobil annuity is superior to these annuities, to the tune of more than $100 a month.

Meanwhile, I was drawn to two other benefits offered by an annuity: longevity insurance and stupidity insurance.�� If I live until I���m 99, as my mother did, the annuity option would work out quite well and, if I don���t, I won���t be shortchanging my nonexistent offspring.

On top of that, while I currently think of myself as a fairly savvy investor���though the less said about certain investments, the better���who knows how savvy I���ll be a few decades from now? I find the idea of $3,124 coming in every month, no matter how many Tokyo Weather Futures I purchase, to be quite reassuring.

I have another week to make a decision. But I think I���ll go with the Exxon Mobil annuity.

Michael Flack blogs at��AfterActionReport.info. He���s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.

Michael Flack blogs at��AfterActionReport.info. He���s a former naval officer and 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry. Now retired, Mike enjoys traveling, blogging and spreadsheets. Check out his earlier articles.The post Taking It Slow appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Too Close for Comfort

WHEN I STARTED investing, I never thought much about risk, partly because I didn���t recognize that there were any.

The investor questionnaires always placed me in the aggressive category. Even though I never ventured much beyond mutual funds, all were pure stock funds, except for a small position in a balanced fund that I briefly owned. I didn���t know much, but I had learned that stocks most likely meant growth over the long haul, and that���s what I wanted.

Around age 50, I added some bond funds, but they were less than 10% of my total holdings. A few years later, on the advice of a fee-only financial planner, I moved more money into bonds, but my heart wasn���t in it. My allocation to bonds remained at less than 20%. Still, I thought I should take the advice I���d paid for.

I had read about risk tolerance, and of the danger that investors find out too late that they weren���t as brave as they imagined. I understood that panic selling after a large market drop would be devastating to retirement savings, but I couldn���t relate. I had experienced a few declines since I started investing in 1998 and, while not fun, I never considered selling. Even so, I mentally filed the information away, knowing I had been humbled by hubris before.

Sure enough, the early 2020 pandemic crash brought a new attitude. My head and my hands executed what I had learned were the right moves. I bought stocks, but I was also stung by my losses. This may have been compounded by the turmoil in my health care job.��The seed of a new emotion was planted, but it barely had a chance to germinate because the market came roaring back.

The rapid recovery and upward march of stocks after the 2020 crash was exciting. Checking my account balance was fun. But it also got me to look more closely at my retirement plan. I was five or six years from retirement. As my last year of work approached, I had planned to move gradually from stocks to short-term bonds and cash. I wanted to wind up with about five years of spending money that was protected from a stock market drop.

But then that unfamiliar emotion, which had cropped up in early 2020, began growing again. It felt like my time horizon had suddenly shortened. After years of being a distant goal, it seemed like retirement was upon me. As the market rose through 2020 and into 2021, so did my uneasiness.

There were other considerations, too. I liked my work, but I had begun yearning to spend at least some time on other pursuits. Also, my wife and I both had mothers over age 90 living semi-independently at home. I could envision a need to commit more time to them. On top of that, my wife had a brother in assisted living who already required more time than we could really afford to give.

The upshot of all this rumination: My wife and I decided to move some of our future retirement spending money out of stocks immediately, rather than doing it gradually as my planned retirement age approached.��Even so, 70% of our portfolio is still invested in stocks. We aren���t ready to fully retire. As long as things remain calm on the home front, our plan is to keep working and buying more stocks. But we wanted enough flexibility to handle an unexpected change in income over the next few years.

I can���t claim that our decision was purely logical. But taking some risk out of our portfolio took some tension out of our lives.

Did we make the right move at the right time? Looking back through the sunshine, I can see that stocks continued to grow after we sold���even after factoring in this year���s decline���and we missed out on some of that growth. We couldn���t have predicted that at the time, as we peered through the fog into the future. But I can tell you that today I���m glad we took some money off the table.

Ed Marsh is a physical therapist who lives and works in a small community near Atlanta. He likes to spend time with��his church, with his family and in his garden thinking about retirement. His favorite question to��ask a��young��person is, "Are you saving for retirement?" Check out Ed's earlier articles.

Ed Marsh is a physical therapist who lives and works in a small community near Atlanta. He likes to spend time with��his church, with his family and in his garden thinking about retirement. His favorite question to��ask a��young��person is, "Are you saving for retirement?" Check out Ed's earlier articles.

The post Too Close for Comfort appeared first on HumbleDollar.