Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 150

April 18, 2023

Getting Old

I COULD BE KIND TO my home and say it has rustic charm, but that would be pretentious. The truth is, it’s an old house, built in 1930 by my maternal grandparents. It sits on a remnant of the farm my family once owned. It’s a place I love, and where I’d like to grow old, and therein lies the challenge.

More than 20 years ago, my father and I extensively renovated the house inside and out. Within the house, every surface was replaced or refinished. My wife gets credit for a share of the painting. We gave it air conditioning to tame the hot, Georgia summers and a furnace to take some of the chill out of winter. The house is still old and drafty, however. Warmth from the wood heater in the fireplace, fed by trees that I cut on the property, draws the family near when nights are frigid.

Though the inside of the house is mostly neat, I can’t say the same for the surrounding property. The rambling yard is decidedly weedy, divided by haphazard beds of old-fashioned bulbs and flowering shrubs lovingly planted by my grandmother, supplemented by annual additions from my wife and me. On three sides, it’s difficult to tell where the yard ends and the surrounding small woodland begins.

Out back, the old smokehouse, which once held hams and bacon, is now home to a clutter of tools and is in obvious need of repair. The dilapidated barn is beyond repair, and is waiting to be put out of its misery.

Wildlife wanders about when Lottie the Labrador retriever is asleep on the porch. This year, on St. Patrick’s Day morning, after letting Lottie out of her kennel, a familiar sound rang out from near the vegetable garden. From our porch, my wife and I observed a wild turkey strut and gobble, until Lottie also spied him and ended the day’s birdwatching.

Since I must take responsibility for the somewhat disheveled landscape, I’ll also claim credit for the order within the productive garden. The vegetable beds are neat, with only a few weeds. The berry bushes are tidy and well mulched. This area within the deer-proof fence is my sanctuary, where for a brief time my mind is at ease, thinking only of soil-building and crop rotations, or calculating the days until I pick the season’s first ripe tomato.

If my words hold a hint of sentimentality, it’s because I can’t hide my feelings when I describe my home. Living within the old structures and roaming the grounds are old and cherished memories from summers spent with my grandparents, along with many more memories built while residing here with my wife and daughter.

The trouble is, old houses weren’t designed with old people in mind. Steps are hard to go up and dangerous to get down. Bathrooms can hold a boatload of hazards, from a layout that’s difficult to navigate to slippery surfaces waiting to encourage a fall. If doorways are too narrow, they can be barriers to walkers and wheelchairs when the time comes for a little mobility assistance. Even before that eventuality, replacing light bulbs and smoke alarm batteries might require a younger helping hand. For me, maintaining my rambling yard and warm fireplace will eventually be impossible.

As physical therapists, my wife and I are under no illusions about the effect of time on aging bodies. Since older patients make up a steady slice of my caseload, I’m frequently either helping them manage their current lifestyle challenges, or counseling them to prepare for those that are on the way. Like it or not, when it comes to living independently in our home environment, we are all on a downward trajectory.

Armed with that cheerful thought, what can my wife and I do to extend the time we’re able to live in the home we love? This has been a casual topic between us for a number of years, but is lately inching toward the preliminary planning stage. For starters, handrails added to the entry steps will increase safety when coming and going. Later, a wheelchair ramp may be a necessity. Fortunately, our house is just one level. But if there were stairs to a second story, a stair lift might have been needed to maintain accessibility to that part of the house.

In the bathroom, we’ll replace our present shower and tub combo with a shower that can accommodate a seat, and later a shower wheelchair, with plenty of grab bars for steady maneuvering. We already have a tall toilet, but strategically placing grab bars nearby will further ease the rise from sitting to standing.

Our house was built with wide doorways, so no modification is necessary if a wheelchair is needed. It’s also already well-lit, which helps older eyes find the safest path, and we can add lever-type door handles that are kind to arthritic hands. Eliminating all of our throw rugs is a safety practice we can employ to prevent falls.

The wood heater was a hand-me-down gift from a friendly, older stranger at the local hardware store. Unlike me, its function is unchanged after 20 years, with only a new blower motor needed to keep it going. I’ll replace it with a gas heater, and have a line run from the tank that currently supplies the furnace. Maybe I can pass along the current wood heater to another energetic homeowner.

I don’t yet have a clear solution for the gardens. But instead of expanding the vegetable and flower beds, I’ve begun reducing their size and hence their required maintenance. I’m also making plans for either repairing or demolishing the old outbuildings, while I’m still able. My wife encourages me to pay to have this done, but it’s painful to pry the dollars from my frugal fingers for a job I can still do myself.

The modifications needed to keep us in our home are still some years away—or maybe not. The future has a way of rushing in before we’re ready. But like 18th century Scottish poet Robert Burns’s “tim’rous beastie,” I’ve laid my best plans, and hope nothing turns me out of my house until I’m ready to leave.

Ed Marsh is a physical therapist who lives and works in a small community near Atlanta. He likes to spend time with his church, with his family and in his garden thinking about retirement. His favorite question to ask a young person is, "Are you saving for retirement?" Check out Ed's earlier articles.

Ed Marsh is a physical therapist who lives and works in a small community near Atlanta. He likes to spend time with his church, with his family and in his garden thinking about retirement. His favorite question to ask a young person is, "Are you saving for retirement?" Check out Ed's earlier articles.

The post Getting Old appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Planning My Exit

WE HAVE A MEDICAL profession apparently wedded to the notion that quantity trumps quality. That’s why, although I have no problem with being dead, I have serious concerns about the process of becoming dead. I have no wish to linger for months attached to tubes, or to disappear for years into the mists of dementia.

I have few childhood memories, and I wouldn’t swear to the accuracy of those I have. Still, one from my teens has remained with me. It was the last time I saw my maternal grandmother, then in her mid-90s and confined to a hospital bed. I remember her begging me to help her end her life. It's possible she only meant for me to help her get out of the hospital. But either way, I was as helpless as she. My mother, on the other hand, died in her sleep in her own bed, after declaring on her 90th birthday that she was ready to go. I can only hope for the latter death. The steps I can take to avoid the former may not work, but I have to try.

First, I have appointed a health care power of attorney. The friend who agreed to serve understands and agrees with my views on end-of-life care. She will, I am sure, say “no”—loudly and persistently—if required. Second, I have a living will, also known as an advance medical directive, that specifies what treatment I do and don’t want in certain circumstances.

My lawyer prepared both documents, along with a financial power of attorney, when I updated my will. I have copies, the folks appointed in my powers of attorneys have copies, and my lawyer has copies, plus they’re stored online with Docubank. I carry Docubank's card in my wallet. In addition, my medical records include contact information for my health care power of attorney. These documents are state-specific. If you’re a snowbird, you probably need two sets. If you’re living on the road, you should talk to your lawyer. Don’t have a lawyer? You could choose to do-it-yourself.

Third, I have a DNR—a “do not resuscitate” order—which states that efforts at cardio-pulmonary resuscitation should not be initiated. Again, this is state-specific. Mine, bright orange, carries the seal of the State of North Carolina, along with my doctor's signature. I have one in my handbag, one in my car and one in my apartment.

Whether the DNR would be honored is, sadly, not clear. If you’re taken to a Catholic hospital, possibly not. If you’re in the operating room, possibly not. The nurse who was about to put me to sleep before eye surgery informed me, rather self-righteously, that a DNR carried no weight there. This completely baffled me. Dying on the operating table is the epitome of a good death. Why mess it up when my wishes are clear?

These precautions are for unexpected events—a car accident, a stroke. What about a disease promising a slow death? What about Parkinson’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, dementia? The medical profession usually won’t help you. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in just 10 states, plus Washington, D.C. You have to be within six months of death, make multiple requests and be able to administer the dose yourself.

Meanwhile, the do-it-yourself methods are unattractive. I could emulate the Romans and slit my wrists, but that seems unfair to the person who finds me. I could visit Mexico in search of pharmaceuticals, if I knew which ones to ask for. Katie Englehart explores some of the options in The Inevitable.

If I have one of those diagnoses, I hope I’ll be able to take a one-way trip to Switzerland, where the right to die is not limited to citizens. It’s not an easy road, requiring multiple interviews and much paperwork, but it is certain. Amy Bloom chronicled the journey she took with her husband, after he was diagnosed with dementia, in her book In Love.

You may find this topic morbid or distasteful. But isn't it better to think about it ahead of time, when there’s no urgency? You may say “let nature take its course,” but we have made that so difficult. Pneumonia used to be called “the old man's friend,” but now we cure it with antibiotics. Death will not stay his hand because we pretend he doesn’t exist, and is likely to be less frightening if we acknowledge him. Articles on this topic draw anguished comments from people who watched helplessly as their loved ones died badly. Do what you can to avoid that fate.

Kathy Wilhelm, who comments on HumbleDollar as

mytimetotravel, is a former software engineer. She took early retirement so she could travel extensively. Born and educated in England, Kathy has lived in North Carolina since 1975. Her previous article was Continuing Care.

Kathy Wilhelm, who comments on HumbleDollar as

mytimetotravel, is a former software engineer. She took early retirement so she could travel extensively. Born and educated in England, Kathy has lived in North Carolina since 1975. Her previous article was Continuing Care.

The post Planning My Exit appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 17, 2023

That 28,000,000% Tax

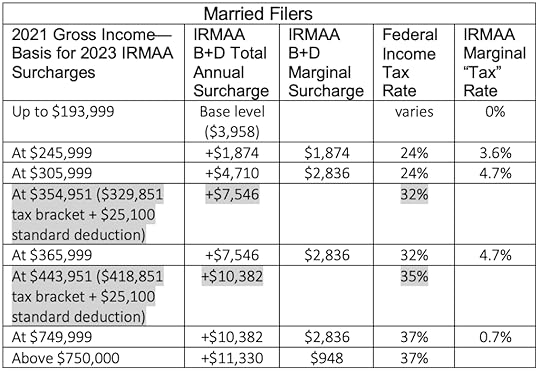

IF YOU’RE IN YOUR 60s or older and making sizable Roth conversions, it isn’t just income taxes that you need to worry about. You may also trigger much higher Medicare Part B and Part D premiums.

We’re talking here about those Medicare surcharges known as IRMAA, short for income-related monthly adjustment amount. These surcharges are over and above 2023’s standard $1,979 per person Medicare premium, and they’re based on income from two years earlier.

IRMAA’s cost impact is usually discussed in terms of monthly per-person dollar amounts. But to give readers a better handle on the true cost, I’ve converted IRMAA’s 2023 surcharges into something more akin to marginal income-tax rates.

IRMAA surcharges might amount to around 1% or 2% of total income. But that’s the average rate. What I’m focused on here is the marginal rate. As you’ll see in the tables below, I’ve calculated “tax-percentage equivalent” IRMAA costs for both single and married taxpayers. These show that the marginal IRMAA surcharges are a minimum 3% to 5% of the additional income involved—but that assumes you’re near the top of each IRMAA income bracket.

Suppose you’re single and your 2021 modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) placed you at the top of the first 2023 IRMAA bracket, which is $97,000 to $123,000. You’d pay a surcharge of $937 in 2023. That surcharge is equal to 3.6% of the total dollar bracket amount above $97,000. Put another way, this 3.6% rate assumes your income was just shy of $123,000.

What if your income was below the bracket maximums? The marginal surcharge “tax” rate will be even higher than 3% to 5%—and it could be vastly higher. How come? IRMAA is a so-called cliff penalty, meaning the full surcharge for any bracket is levied as soon as your income crosses that bracket’s threshold income. In other words, IRMAA surcharges for each income bracket behave totally unlike regular income taxes, where the same marginal tax rate applies to each dollar within that income-tax bracket.

The tables also highlight two federal income-tax thresholds, which are shaded in grey. For instance, the 2021 income-tax brackets included a sharp jump in marginal tax rate from 24% to 32% for single filers with taxable income of $164,926 and above, and for joint filers at $329,851 and above. In the tables, these income thresholds are adjusted for the standard deduction, so they’re comparable to the IRMAA thresholds. Keeping an eye on such federal income-tax thresholds can be as important as managing your IRMAA brackets.

Considering Roth conversions and worried about IRMAA? Here are seven insights that my wife and I have gleamed:

The tables show a strong incentive to undertake Roth conversions before age 63. Once you reach 63, any Roth conversions could potentially affect the Medicare premiums levied two years later, when you turn age 65. With the benefit of hindsight, my wife and I should probably have done bigger conversions prior to age 63.

We manage our income, including planned Roth conversions, to put us toward the top of our IRMAA income bracket, so the marginal surcharges are in the 3% to 5% range.

Whether you’re converting to a Roth or not, there’s a huge incentive to keep your income from breaching the next IRMAA income threshold. In fact, IRMAA surcharges at the beginning of brackets may be the country’s most punitive incremental tax, which—for a married couple—I calculate to be some 28,000,000% on that first penny.

IRMAA brackets two years from now aren’t known precisely because the thresholds are inflation-adjusted. Still, early projections are available. We manage our income to get within $4,000 to $5,000 of the projected bracket ceiling, thus leaving some margin for error.

When required minimum distributions kick in, we’ll potentially find we’re still in IRMAA surcharge territory. Still, today’s conversions should help, because subsequent investment growth from today’s Roth conversions will never trigger IRMAA.

Federal income-tax brackets are also worth watching, especially those at 2023 taxable incomes of $182,100 for single filers and $364,200 for married filers. These trigger the eight-percentage-point jump to the 32% income-tax rate. In recent years, the income levels where tax rates jump have often been close to one of the IRMAA bracket ceilings.

IRMAA surcharges are a single-year cost. But the Roth conversions that trigger that cost will result in decades of tax-free growth for us and our heirs, and that growth should help us recoup today’s IRMAA costs.

John Yeigh is an author, speaker, coach, youth sports advocate and businessman with more than 30 years of publishing experience in the sports, finance and scientific fields. His book "Win the Youth Sports Game" was published in 2021. John retired in 2017 from the oil industry, where he negotiated financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. Check out his earlier articles.

John Yeigh is an author, speaker, coach, youth sports advocate and businessman with more than 30 years of publishing experience in the sports, finance and scientific fields. His book "Win the Youth Sports Game" was published in 2021. John retired in 2017 from the oil industry, where he negotiated financial details for multi-billion-dollar international projects. Check out his earlier articles.The post That 28,000,000% Tax appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 16, 2023

Be Like the Smiths

The results have run counter to intuition: Employees who are offered unlimited vacation end up time off than those working for companies with traditional vacation policies. Why? A common explanation is that people struggle when they lack clear guidelines.

In this case, it appears that—in the absence of a defined policy—employees are doing what seems safest. By taking less time off than they could, they’re trying to protect their professional reputations. They want to be seen as hard workers. By contrast, when employees are told that they have, say, 15 days off, they’ll tend to take all 15 days off. In short, people do better with structure.

This idea applies in nearly every domain. I recall taking a family vacation to a destination where both food and lodging were included for one flat rate. The result: Without the usual mealtime structure, I found myself with a stomachache and a desire never to go back.

This same dynamic applies to our personal finances. Limits can be helpful. Counterintuitive as it might seem, if you have a surplus in your budget—or assets that exceed your foreseeable needs—budgeting can be tricky. “Can I afford this?” If the answer to that question is “yes” in virtually every case—or every reasonable case—it’s harder to know how to set boundaries.

For better or worse, financial decision-making is more straightforward for those with limited means. A new iPhone, for example, is either affordable or it’s not. But if you can easily afford a new phone or a new car or maybe even a new home, it’s harder to know how to establish limits. This might sound like “a good problem to have.” But in reality, it applies to many retirees, who have ready access to their life’s savings.

How do folks handle this situation? Among those who have achieved financial independence, people tend to fall into one of three categories.

The first look something like the Vanderbilt family. In the 1890s, the Vanderbilts were the wealthiest family in America. With that fortune, they built the Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, the largest of the Newport mansions, with 30 bedrooms just for staff. In North Carolina, they constructed the Biltmore Estate, which—at nearly 180,000 square feet—is still the largest home in the U.S. And, of course, they endowed Vanderbilt University. The unhappy result, however, was that the family’s fortune dwindled in a surprisingly short period of time.

The second group couldn’t be more different from the Vanderbilts. They look something like Ronald Read. A resident of Brattleboro, Vermont, Read spent most of his career as a gas station attendant. But when he died in 2014, he left an estate of nearly $8 million, owing mostly to his frugality. When he drove into town, for example, he would park a few blocks away from his favorite coffee shop to avoid parking meters. When the buttons fell off his jacket, he used a safety pin to hold it closed. His appearance, in fact, was such that a fellow restaurant patron once paid the tab for his meal, believing he was destitute. In short, Read took frugality to an extreme—far beyond what was necessary.

What about the third group? We might call them the Smiths—because they don’t look too different from their neighbors. They’re not obvious over-spenders, but they’re not overly frugal, either. You might see them in a Mercedes, but they’re just as likely to drive a Honda Accord. You might see them at a country club, but you might also find them enjoying a public golf course. They’re the traditional “millionaires next door.” Sometimes, only their accountants know they’re wealthy. In short, families like the Smiths know how to achieve financial balance.

In my career, I’ve interacted with folks from all three groups. As you might guess, those in the Smiths’ category are invariably the happiest. While it might seem like common sense not to spend too much or too little, it can be tricky to achieve this balance. But there are some strategies that can help.

If you’re in your working years, I recommend the “pay yourself first” approach to spending. First, determine how much you need to save to meet your goals, and then set up a mechanism to save this amount automatically. The easiest way is via payroll deductions into a 401(k) or similar retirement plan.

Alternatively, or in addition, you could set up automatic transfers from your checking account to a brokerage account. Finally, you could ask your human resources department to split your paycheck, so part of it goes into your checking account and part into a separate savings account. However you structure it, the idea is to set aside your required savings first. You then have the freedom to spend what’s left in whatever ways you wish.

If you’re in retirement, you can follow a similar approach, just in reverse. Whether you follow the 4% rule or another approach to spending, the key is to set up a structured plan for portfolio withdrawals. Suppose you calculated that you can safely withdraw $5,000 a month from your portfolio. You would then set up automated transfers from your brokerage account to your checking account. I recommend scheduling these transfers for the first of every month. You could then freely spend that sum each month.

How would required minimum distributions (RMDs) fit into this framework? For some, RMDs meet only part of their annual spending requirements. But for others, RMDs exceed their spending needs. That’s why I don’t suggest distributing your RMDs directly to your checking account. Instead, have your RMDs transferred from your retirement accounts to your taxable brokerage account. From your brokerage account, you can then arrange a steady monthly cash flow to your checking account, making it easier to stay on track.

Once a structure like this is in place, I suggest reviewing it about once a year and adjusting your savings or withdrawal rates accordingly. This, I believe, is the secret to being as happy as the Smiths.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Be Like the Smiths appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 14, 2023

What’s Your Answer?

COMMENTS FROM READERS are one of HumbleDollar’s greatest strengths. Just finished perusing an article? If you don’t scan the comments posted below, you’re often missing out on some savvy financial insights and eye-opening personal stories.

With an eye to tapping into this strength, I launched the Voices section two years ago. My hope: The questions—now 133 in total—would offer a way to organize readers’ collective wisdom and become a go-to resource for those seeking help on a particular financial topic.

To be honest, the Voices questions haven’t garnered as much reader participation as I’d hoped. Still, I find the answers fascinating and, fingers crossed, perhaps the section will eventually catch fire with readers. Meanwhile, here—in order—are the nine questions that have so far generated the most responses:

1. What’s the best financial book you’ve ever read? Among the 45 comments, there’s a wide array of books and authors listed. But perhaps the most mentioned are The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas Stanley and William Danko, John Bogle’s books, Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street and William Bernstein’s books.

Incidentally, Bill has a new edition of The Four Pillars of Investing coming out in July. I had the privilege of writing the foreword. Bill also contributed an essay to My Money Journey, the HumbleDollar book that’ll be published later this month.

2. What percentage of a stock portfolio should be invested abroad? This has long been a raging debate among investors, and the responses reflect that, with folks suggesting foreign-stock allocations ranging from 0% to 50%. After strong U.S. stock returns over the past decade, maybe it isn't surprising that many folks are content to have no money invested abroad. But if foreign markets have the edge in the decade ahead, will they feel differently? I, for one, would be happier. As I’ve mentioned before, my single biggest fund holding is Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund (symbol: VTWAX), which has 41% allocated to foreign markets.

3. What’s your favorite financial quote? This question generated a slew of entertaining and thought-provoking responses. Among those offered, my favorite—given today’s inflation—originated with comedian Henny Youngman: “Americans are getting stronger. Twenty years ago, it took two people to carry $10 worth of groceries. Today, a five-year-old can do it.”

4. What costs are you most loath to pay? While some readers cited significant costs—financial advisory fees, car repairs, insurance premiums—it seems it’s small expenses that rankle the most, especially those unexpected fees that get tacked on to things like car rental costs, cable bills, concert tickets and hotel bills.

5. When does it make sense to buy the extended warranty, if ever? A majority of readers advised against ever paying for the warranty. Still, there were a few intriguing exceptions, notably phones and laptops bought for children.

6. What stock would you happily hold for the next 10 years? The enthusiasm for Apple and Berkshire Hathaway isn’t terribly surprising. Instead, I’d give kudos to the folks who mentioned Waste Management. As one reader wrote, “Everyone has trash. It’s Amazon proof. It has multiple moats. Pays a dividend. Essentially recession proof.”

7. What aspect of the tax code do you hate the most? So far, there have been 26 responses to this question and—amazingly—there’s almost no overlap among the answers. If folks can find so many different things to hate, doesn’t that tell us that the U.S. tax code is indeed an abomination?

8. What’s your No. 1 goal for retirement? The most amusing answer: “To become a major actuarial loss for my employer’s pension fund and enjoy every minute of it.” That, of course, was posted by the inimitable Dick Quinn.

9. What are the smartest financial moves you’ve ever made? Many folks wrote about their good savings habits. But I was also struck by the number of answers that mentioned homeownership. Maybe that reflects the nature of real estate: It’s a big, undiversified bet and—when it works out—it often works out very well.

Meanwhile, with just three responses, the least answered question is this one: What should you look for when buying a home? The three answers are all helpful. But come on, people, I’ve got to imagine there’s more to be said on this topic.

What Voices questions would you like to see asked? That, too, is among the 133 questions. You can post your suggestions here. Not sure how to comment? Check out this page.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post What’s Your Answer? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

It Also Has Wheels

WE'VE OWNED OUR NEW 2023 Toyota Highlander Hybrid for six weeks. The technology and features are breath-taking. Until now, both of our vehicles were 18 years old. I feel like Rip Van Winkle, waking up in a time I do not recognize.

Here are some of the bells and whistles on our new SUV, and my evaluation of their usefulness. Please forgive me if some of this information isn’t accurate; I’m still learning about these features.

Automatic parking brake engagement and automatic headlight dimming. Every time we put the vehicle in park, it automatically activates the parking brake. At night, the headlights automatically dim if there’s oncoming traffic or if we’re following another vehicle. Both of these are useful but unnecessary. I know how to set the parking brake; I know how to dim the lights.

Blind spot monitor. This is one feature I really like. A yellow icon appears on our outside left or right mirror if there’s a vehicle in our blind spot on that side. When passing another vehicle, it confirms that I have gone far enough around the other vehicle to pull safely back to the right lane.

Cross-traffic alert. When I’m backing out of a driveway or out of a parking spot, there is both a visual and audible alarm if a vehicle or person is approaching. Nice, but not necessary.

Driving position memory. This feature automatically adjusts the driver’s seat and outside rearview mirrors to suit your preferences. Because of the chip shortage, we were given only one key. A second key will be sent to us at some indefinite future time. When my wife and I each have our own key, the driver’s seat and outside rearview mirrors will automatically go to the positions last used by the driver with that key. This seems like it’ll be useful.

Dynamic radar cruise control. As with any cruise control system, this keeps the vehicle at the desired speed. But the “dynamic radar” portion of this system automatically slows us down as we approach another vehicle. My complaint: It slows us down too soon. My daughter told me I should be able to adjust this distance. As soon as I activate my turn signal to move over to pass the slower vehicle, the speed picks up nicely. My plan: Set cruise control to 100 miles per hour and the vehicle will automatically adjust to the speed of traffic. My wife does not agree.

Eco Score. A few days ago, I must have hit the wrong button. The dashboard display behind the steering wheel now displays my Eco Score. My Eco Score has ranged from 30 to 80. There are blue and green bars that fluctuate. It also has display areas for starting, cruising and stopping. I don’t know what any of this means. Perhaps I am a terrible person because I don’t care about my Eco Score, but this seems entirely useless. I need to find out how to change the display back to something useful.

Keyless starting. We start the car by simply pushing a button on the dashboard. The key needs to be close by. This feature would be more impressive if I could leave the key in my pocket—but that doesn’t happen. Every time I leave the car, I pull out the key to lock it, and every time I approach the car, I pull out the key to unlock it.

Lane tracking assist. When there are white or yellow lines on the road, this is supposed to help keep me in my lane. If I get too close to either side of my lane, it gives my steering wheel a “gentle nudge” to keep the vehicle in the lane. If I begin to cross a white or yellow line, it emits three beeps. This feature turns off when I activate the turn signal.

Does it really keep me in my lane? I knew of only one way to find the answer: Take my hands completely off the steering wheel. So, of course, that’s what I did. It performed admirably. But after about 10 seconds, a message appeared telling me to put my hands on the steering wheel. Overall, I find these gentle nudges to be annoying. The steering wheel is constantly moving back and forth in my hands.

Outside mirror defogger. When we turn on the rear window defogger, the outside rearview mirror defoggers also activate. This should eventually clear snow, or perhaps even ice, off the outside mirrors. We park in a garage and rarely have fog or snow on our outside mirrors, but this could be useful at times.

Rearview camera. Is this feature now ubiquitous on new vehicles? I have found this helpful, especially when backing into a parking spot.

Remote vehicle starting. A few weeks ago, I received an email from Toyota reminding me that if I download its app, I can use it to start the car from my living room. This will allow me to warm up or cool down the interior before I get in. The small print says my vehicle will wirelessly transmit my location, driving and vehicle health data to Toyota “for internal research and data analysis.” Thanks, but I’ll pass.

Three driving modes. Instead of “normal” mode, I can select either “sport” or “eco.” I’m not sure what these other modes do for me. I asked the salesperson and he really had no idea. I would guess that, like me, nearly all owners of vehicles with this feature always use “normal.”

Warning messages. Once, when I started the vehicle, a message appeared, “Caution. Roads May Be Icy.” When it’s below freezing and there has been precipitation during the night, I know the roads may be icy. Apparently, others find it helpful to be reminded of that. I have no idea what other nuggets of wisdom the car may want to impart to me at some future time.

Meanwhile, I can easily think of three features that I’d like to have on our new vehicle.

CD player. I don’t want to download songs using Bluetooth. I already have collections of songs I would like to hear. They’re called CDs. My brother tells me that for $30 I can buy a portable CD player and plug it into our vehicle.

Intuitively obvious buttons. The function of the myriad buttons and choices is not at all clear. I had to consult the owners’ manual to turn on the heater. Enough said.

Mid-dash display returns to last setting. Every time I turn on the vehicle, the display between the two front passengers brings up some bizarre, meaningless display. I wish it would automatically revert to the last place I had it set.

With our new vehicle, we took our 19-year-old granddaughter and my 95-year-old mother on a road trip to Colorado’s Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park. The latter has perhaps 100 miles of roads and there’s nary a guard rail in sight. Frequently, the shoulder is only a few feet wide and going off the edge means tumbling hundreds of feet to a certain death. Yet there are almost no traffic fatalities because people know their lives depend on being alert.

Many of the features on our new vehicle enable or even encourage inattentive driving. I wonder what would happen if we outlawed all of these features, and by edict also removed all airbags and seat belts. Is it possible the number of accidents would go down because people would know that if they were in an accident, they would likely die? I would be in favor of this except I know careless drivers would kill not just themselves, but also many innocent people.

Our new vehicle cost $47,210, including tax and registration. My wife and I are frugal. We are also careful drivers. If Toyota offered the same vehicle—but with none of the above features—for $10,000 less, that’s the model we would have chosen.

Larry Sayler is the only person with a Wharton MBA who also graduated from Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Clown College. Earlier in his career, he served as CFO for three manufacturing and service organizations. For 16 years before his retirement, Larry taught accounting at a small Christian college in the Midwest. His brother Kenyon also writes for HumbleDollar. Check out Larry's earlier articles.

Larry Sayler is the only person with a Wharton MBA who also graduated from Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s Clown College. Earlier in his career, he served as CFO for three manufacturing and service organizations. For 16 years before his retirement, Larry taught accounting at a small Christian college in the Midwest. His brother Kenyon also writes for HumbleDollar. Check out Larry's earlier articles.The post It Also Has Wheels appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Don’t Go Away

EMBARRASSED BY YOUR impulse to try the “sell in May and go away” gambit? Don’t be. You’re in good company. Selling stocks in the spring and returning in autumn was a favorite pastime of London financiers and bankers, who abandoned the steamy city for cooler vacation destinations. They resumed stock trading around St. Leger’s, the day of the last leg of English horse racing’s Triple Crown.

The tendency of global stock markets to rise less in the six months from May to October, compared to the year’s other six months, gained traction in the U.S. after articles about this seasonal anomaly appeared in The Wall Street Journal and the Stock Trader’s Almanac in the mid-1980s. In the ensuing years, the reliability and usefulness of the strategy have been subjected to much scrutiny.

Stock market gains from May through October have averaged some 2%, compared with 8% from November through April. From 1970 to 1998, the spring-summer span underperformed the fall-winter span in 36 of 37 developed and emerging markets. What about the U.S.? Since 1945, the S&P 500 has finished with a gain 77% of the time during the November-to-April period and 67% in the remaining half-year.

But the difference between the more and less desirable six months may be narrowing. In the 10 years ending in 2020, the Memorial Day to Labor Day stretch added almost 4% to annual results. The growth of the internet has been cited as a reason the summer doldrums may disappear. A whole new wave of folks can now invest while sipping a margarita on the veranda of their summer beach house. Alternatively, the improvement from 2% to 4% during the weaker six months could just be a function of the market’s bullish cast over the past decade.

Early on, some market observers recommended switching to cash or Treasury bills for the late spring and summer. But Treasurys and money market funds have struggled to notch a 2% annual gain in recent years. Even now, yields on those cash investments only equal the 4% achieved by the market during the seasonally weaker May-October period—and, of course, we’re talking about a 4% annual yield, which would only be worth 2% over six months. To be sure, T-bills are safer than stocks, but short-term volatility is—or should be—pretty irrelevant to long-term investors.

So far, we’ve seen little reason for the long-term index fund holder to bail out for the dog days of summer. But I did come across an intriguing switching strategy proposed by investment strategist Sam Stovall, often acknowledged as the dean of sector investing. Citing evidence that defensive sectors perform better in the May-October time frame, he suggests rotating into health care in the spring and then back into the broad market in the fall.

I checked how the strategy would have worked during 2021’s 29% market gain and 2022’s 18% loss. In 2021, from around Memorial Day to Labor Day, prices of Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (symbol: VOO) increased 11%, while Vanguard Health Care ETF (VHT) rose 9%, meaning the Stovall strategy fell short. But it was a different story last year. In 2022’s spring-summer stretch, Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF fell 6%, while the Health Care ETF advanced more than 2%. That means that, for the two years combined, Vanguard S&P 500 gained about 5%, while Vanguard Health Care picked up 11%.

Still, two years is a woefully insufficient sample and, indeed, the bump in health stocks could be just a random blip. Moreover, folks trading in taxable accounts should keep in mind that any gains could be taxed at short-term capital gains rates. The bottom line: For all but the most intrepid, I see no reason to ditch your broad market index funds when you decamp for your summer mansion.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

The post Don’t Go Away appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 13, 2023

Who Do You Trust?

MORE THAN 92,000 people over age 60 reported losses to fraud totaling $1.7 billion in 2021, according to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center. That represented a 74% increase in losses from the year before.

With the population of older Americans growing, the need to protect this vulnerable population is more critical than ever. Enter the concept of a trusted contact.

The trusted contact has its origin in a Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) rule issued in March 2020. It urged registered investment advisors to ask clients to name someone the advisor can contact in case of suspicious activity. If you’ve opened a new investment account lately, you’ve probably been asked for a trusted contact.

FINRA defines the role this way: “A trusted contact is an individual authorized by an investor to be contacted by their financial firm in limited circumstances, such as concerns about activity in the investor’s account or if the firm has been unable to reach the investor after numerous attempts.”

Who might be named? It’s most often a family member, but it can also be an attorney, accountant or another reliable third party. Whoever it is, the intent is the same—to provide “another layer of security on the account and puts the financial firm in a better position to help keep the account safe," in the words of FINRA CEO Robert Cook.

Financial industry veteran Ron Long said the trusted contact concept arose from numerous experiences in which advisors had clients who were requesting funds from their accounts to pay for obvious financial scams. "Scammers often rely on victims succumbing to pressure to act fast and to avoid discussing the money disbursement with anyone," said Long, a principal at Long Life Consulting of Seattle, who was previously the head of Aging Client Services at Wells Fargo.

"When an advisor is able to involve a trusted family member, often a son or daughter, they are able to speak with that loved one and successfully break the trance which the bad guy has over their parent,” Long said. “In other instances, the trusted contact acts as an 'in case of emergency' resource where an advisor observes signs of diminished capacity or has difficulty contacting an elder client."

While the concept of a trusted contact is a step in the right direction, it’s not a substitute for a more comprehensive approach to safeguarding elders and their money. For one thing, the circumstances under which a financial firm is authorized to contact the trusted contact are limited, and don’t cover all the possible scenarios in which elder fraud might occur.

As demographics shift, and the demands on clients and their advisors expand, we need to evolve our approach to prevent elder fraud. This is especially important given the increasing rates of cognitive impairment among older Americans. Here are five steps the public and financial professionals can take to defend those most vulnerable.

Add a trusted contact on financial accounts.

More professionals should have training on the warning signs of fraudulent activity, such as a senior making an unusually large withdrawal at the bank.

Financial professionals must overcome their hesitation and be willing to raise questions even in uncertain situations. The need for frank, open dialogue between a professional and the trusted contact is critical.

Education and communication are the keys to helping clients, friends and loved ones. Ask parents or older relatives if they have named a trusted contact. If they haven’t, consider volunteering for the role.

Stay in contact with your elderly family members and friends. Simple questions and social interaction are sometimes enough to prevent or uncover an attempted fraud.

As scammers become more sophisticated—and technologies have become ever more convincing—the responsibility falls on all of us to stay vigilant. The financial industry must take additional strides to better protect those at risk.

“In most instances, a client will never need an advisor to use the trusted contact,” Long said. “But like insurance, it is better to have the trusted contact and not need it than to need the trusted contact and not have it.”

D. Casey Snyder, CFP®, is a senior vice president of the Sedoric Group of Steward Partners, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In addition to his family, the passions that pull him away from his desk include cooking, gardening and mountain biking.

D. Casey Snyder, CFP®, is a senior vice president of the Sedoric Group of Steward Partners, a financial advisory firm in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In addition to his family, the passions that pull him away from his desk include cooking, gardening and mountain biking.

The post Who Do You Trust? appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Saved by Compounding

IF I MADE A LIST of all the dumb things investors do, I likely committed them all. I chased performance, sold stocks in a bear market, invested in things I didn’t understand—you get the picture.

Yet, despite the numerous setbacks I suffered before I matured as an investor, I was able to retire comfortably. How was that possible? My conclusion: compound growth. Indeed, I believe compounding is a surer way to wealth than picking market-beating investments. That belief originated with, and was reinforced by, Warren Buffett.

The book Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules, written by Jeremy Miller, details lessons to be learned from Buffett’s annual letters to Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholders. The book’s second chapter is devoted to compounding. Here are three highlights from that chapter:

1. “The power of compounded interest is unmatched by any other factor in the production of wealth through investment,” says Buffett. “Compounding over a life-long investment program is your best strategy, bar none.”

The words “bar none” jumped out at me. Here is one of the world’s most astute investors saying that compounding trumps stock picking when it comes to building wealth over the long-term. That was an eye opener.

One of Warren Buffett’s favorite long-term holdings is Coca-Cola. He started purchasing shares in 1988. Today, it’s the fourth largest holding in Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio. According to Buffett, “The cash dividend we received from Coke in 1994 was $75 million. By 2022, the dividend had increased to $704 million. Growth occurred every year, just as certain as birthdays. All Charlie and I were required to do was cash Coke’s quarterly dividend checks.”

I’ve owned Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund (symbol: VTSAX) in my taxable account since 1998, and have reinvested distributions and purchased additional shares over the years. In 2022, this one investment yielded more than $13,000 in dividends. In the future, if I request that Vanguard direct those distributions to my money market fund, I’ll enjoy a nice boost to my retirement income courtesy of the U.S. stock market—and at the lower tax rate for qualified dividends.

When I think about my history with this fund, I realize that what was most important was the steady accumulation of dividend-paying shares, not a rising share price. Long-term investors might consider tracking the number of shares they own rather than the dollar value of their investment. An exponentially growing number of dividend-paying shares is what compounding looks like.

2. “Compounding derives its power from its parabolic nature; the longer it goes, the more impactful it becomes,” Buffett has written. “However, it does take significant amounts of time to build sufficient scale.”

We’ve all seen those graphs, with their upwardly sloping curves, that are used to illustrate compound growth. These graphs have three noteworthy characteristics. First, early returns have a modest impact and the power of compounding isn’t readily apparent. I often wonder if some people look at these early returns, conclude that compounding doesn’t work and then turn their attention to other investment strategies.

Second, the timeline in many of the graphs extends to 30 years or more. Patience is a virtue. Due to increased longevity, many recent retirees likely have two or three decades ahead of them. When trying to overcome the effects of inflation, compound growth can be as important to retirees as it is to younger investors.

Third, compound growth from reinvested dividends happens automatically and doesn’t require you to do anything. Compare this to the effort needed to choose individual stocks or do your own taxes.

3. “Small fractional changes in the compound rate produces hugely different outcomes over long periods,” notes Buffett. “Fees, taxes, and other forms of slippage can add up to have an enormous cumulative impact. While 1-2% a year in such costs seems minor when isolated to a given year, the power of compounding turns something that looks minor into something colossal.”

Consider an investor over a 30-year period earning a 5% average annual return after expenses, versus a pre-cost 7%. Missing out on those two percentage points yields a final result that’s half what it could have been.

Buffett states that, “Fees and taxes… have been crushing the long-term investment performance of most Americans.” He advises us to, “Avoid fees and taxes to the fullest extent practical.”

That’s why investing in low-cost, broad-based index funds is so appealing. But such investments must be bought and held. The more you trade, the more likely you’ll disrupt compounding and need to start over again, losing precious time.

Shlomo Benartzi, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, coined the term “exponential-growth bias” to describe people who are unaware of the effects of compound interest. He hypothesizes that such people think their savings grow linearly, not exponentially, and thus underestimate the benefits of long-term investing. Those with a linear mindset may conclude that it’s relatively easy to make up for lost time, and decide to postpone saving in favor of other, more immediate needs. But ask those trying to make up for lost time, and they’ll tell you that it’s far from easy.

Keep in mind that compound growth has a dark side. Inflation, the enemy of all investors, also increases exponentially. Each year’s inflation rate builds on last year’s rate. Aside from excessive debt, inflation is probably the biggest obstacle to wealth creation that investors face. We can use all the help we can get to earn positive real returns.

When trying to build wealth, compound growth is one of the few winds at our back. I’d like to see it emphasized far more frequently than it is currently. Too often, investment discussions seem skewed toward beating the market—and that’s a shame.

Philip Stein, currently retired, was a public health microbiologist and later a computer programmer in the aerospace industry. He maintains that he’s worked with bugs, in one form or another, his entire career. Phil and his wife Jeanne live in Las Vegas.

Philip Stein, currently retired, was a public health microbiologist and later a computer programmer in the aerospace industry. He maintains that he’s worked with bugs, in one form or another, his entire career. Phil and his wife Jeanne live in Las Vegas.

The post Saved by Compounding appeared first on HumbleDollar.

April 11, 2023

Stock Therapy

PUBLIC SPEAKING WAS my nemesis throughout my academic career. Though I found it frightening, I’d always been able to tough my way through the lectures and avoid a full-blown anxiety attack. Then, during a theories of psychotherapy seminar for psychiatry residents, the panic broke through.

Though only my first diagnosable episode, it portended an affliction far more sinister. It was a premorbid symptom of an underlying depression that would topple my career, derail my investment ambitions, and plunge me into an early and unplanned retirement.

As 1984 unfolded, I was at the top of my game. I had just married Alberta, the woman I still love. I was granted tenure as a psychologist at a leading medical school at age 39. As director of psychiatric research, I had published more than 100 scientific articles and served as an associate editor of a prestigious psychology journal. An abundant personal and professional future seemed assured.

But I was too young and immature to imagine how a cacophony of unlikely events could unravel a person’s life. In the spring, Alberta’s mother committed suicide. Then, in September, my sister was murdered by a serial killer, her decomposed body discovered in a dumpster. Years later, as a patient, I would make the connection between my sister’s suffocation and my gasp for air while teaching.

My world became even more menacing a few months later. After learning of deadly assaults on a third-year-medical student and a pulmonologist in hospital bathrooms, I became afraid to enter public restrooms. By then, I realized that something ominous and powerful had taken hold. The depression exposed by that first seminar anxiety attack lasted for two decades, the heart of my adult life. I never returned to work. I crumpled as if shot from behind.

Recovery was agonizingly slow. I was hospitalized with suicidal thoughts. Alberta was told my symptoms were resistant to treatment. Psychoanalytic therapy promoted my self-awareness, while cognitive therapy gave me tools to combat my negativity. But they were not cures. I was prescribed countless antidepressants and endured harrowing side effects until, miraculously, one hit.

Reentry into the fabric of everyday life went surprisingly well, except for my social reengagement. I felt shame about my long battle with depression and experienced the stigma surrounding mental illness that’s still pervasive, even among health professionals.

Far wiser and more empathetic, thanks to my own experience, I opened a psychology practice rather than return to research. Some years later, I realized a lifelong dream of becoming an independent investment advisor affiliated with a large discount broker. More important, I’ve been enjoying a meaningful retirement that includes contributing to HumbleDollar.

Here are six strategies that helped me stagger through the darkness and emerge a healthier person. Perhaps they offer a roadmap for you or for a loved one blindsided by mental illness or other health catastrophe. But first and foremost, get professional help in the form of psychotherapy or medication, and preferably both.

1. Accept reality. Unfairly or not, you’ve been targeted. As my son Ryan likes to say, “It is what it is.” You will have a career, friends and retirement, though it may not be how you envisioned it. Some bitterness and denial are understandable, but you need to get beyond them to restore good mental health.

2. Have a purpose. Everyone needs to find meaning, all the more so if you wake up with the world looking bleak. It doesn’t have to be something heavy like deepening your spirituality. It could be volunteering for a charity or supporting a political candidate. For me, it meant preparing Alberta to manage our investments in the event I did not regain full functioning. I tried my best under the circumstances to do the financial coaching and make the necessary arrangements.

3. Mine your favorite activities. By now, hobbies have likely become your loyal allies, and you can turn to them for sustenance and replenishment. Like to read, go to the theater, exercise at the gym, putter in the garden? Do it.

Once a sideline, the stock market became the lifeboat that transported me across all those failed treatments and dwindling hopes. With hours to spare, I became a voracious reader of investment classics like Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor and Peter Lynch’s One Up on Wall Street. Saturday mornings were a special treat. I would bound out of bed and ride my bike to Tower Books to pick up the new edition of Barron’s. I often walked to the library to devour the latest update to the daunting Value Line Mutual Fund Survey like it was a John Grisham thriller. I had my analyst, I had my Prozac—and I had stock therapy.

4. Fight off the doldrums. Emphasize more complex activities that get your mind off all that pessimism. Routine tasks like household chores are useful in keeping busy, but they’re so automatic that they aren’t as effective in replacing the disturbing thoughts. Like to walk but can’t shake the blues? Don’t forget your headset. In my case, there’s nothing like classic rock and roll while I’m rummaging through the mail.

5. Dump the downers. You’re a skilled handyman and notice a tile has fallen from the roof, a sure sign of trouble brewing. You’ve repaired the roof before but dread the thought of another go-round. Ditch the problem for now. The fact is, you’re compromised and the roof probably has three more years of wear on it anyway.

I felt I needed rental properties to diversify from the stock market, but I loathed the responsibilities and nuisances. In my condition, I couldn’t muster the energy or will to perform critical tasks like renting a vacant unit and, besides, I was hapless as a do-it-yourself handyman. Overcoming longstanding anxieties about delegating authority and piling on additional expenses, I hired a property manager. It was a home run and a lesson in trust. Debbi has been a godsend for almost 40 years.

6. Seek out emotional support. In this respect, I was blessed. I have a devoted family that accepted I had a severe depression, as well as several close friends who witnessed my fall. This last strategy is crucial. Whether family member or friend, find at least one intimate relationship with someone you can be totally yourself with, a person you can count on to “be there” for you. If you feel the need to be “on” or would be afraid to go down into your emotional abyss with the person, he or she isn’t the right one.

That’s the gist of how I groped from personal tragedy to renewal. It’s hardly a precise formula, but perhaps it’s a rough roadmap for people struck by a random catastrophe in financial matters, health or otherwise. I’m thankful for another go at life, but under no illusion that a single bout guarantees a future free pass. I stand vigilant yet humble, ever aware of how fleeting the good times can be.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

The post Stock Therapy appeared first on HumbleDollar.