Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 139

July 4, 2023

Free to Give

I WAS RAISED IN a small town in Iowa. My mother died of breast cancer when I was two years old. My father struggled to cope with her death, but he paid the bills and made sure my basic needs were met. Indeed, when I look back, my upbringing seems pretty normal.

I survived high school, but had no clue what I was going to do with my life. One day, my father decided to give me a nudge. He said, “You’re going to have to find another place to live before the year is out.” My jaw dropped and panic set in. Within a month, I signed up for the U.S. Army.

It was my chance to fly, but it was also my chance to stumble and quite possibly fall on my face. I was scared, plain and simple. I was entering a world where money was earned, spent and sometimes saved by people who looked a lot like me. Except there was a problem: I knew nothing about money and how to manage it.

My journey was just getting started, but I was winging it. Because of my lack of financial education, I made many mistakes. My intentions were good, but the results were bad. That continued for many years.

After completing my army training at Fort McClellan, Alabama, I was sent to my first duty station, serving as a military policeman. This was my first opportunity to handle money. I spent plenty, saved what was left, and basically just did what most of my buddies were doing, so it all felt very normal. The money decisions I was making were being influenced by marketing, comparison, materialism and some good old-fashioned ignorance.

Then one day, a supervisor told me I should consider investing my money. I agreed and off we went to a “free” dinner. She introduced me to a sharp-looking fellow, and he said he would “help” me. Within no time, I was an investor in a high-cost mutual fund. Then, I was ushered over to another gentleman. This insurance agent quickly signed me up for a whole-life policy.

By spring 1986, my paycheck had gotten bigger, and that meant it was time to buy a better car. That’s the American way, right? As I stepped onto the new car lot, the salesman flew over to greet me. He asked me what I could afford on a monthly basis. Soon, I was the owner of a brand-new car.

The Army decided to send me to Germany in 1989. What does a young man do when he has free time on his hands? I could have spent my time at the local bars, chasing pretty girls and enjoying German beer, but I chose a different option. I chose to read. This was a decision that truly changed my life.

One day, one of my buddies stopped me and asked if I was investing in the stock market. I stuck my chest out and said “yes.” He asked if I could teach him how to do this investing “stuff.” I agreed to his request. The evening came, and my friend was full of questions. Sadly, I had no answers. I was still financially dumb.

Getting educated. The next day, I headed to the local bookstore. What was I looking for? I didn’t know, but I had to start somewhere. I found a book, Wealth Without Risk by Charles Givens. I picked it up, ruffled through it, said “what the hell” and paid the lady at the counter $20. This was the beginning that would change my life.

I took that book home and read it. What did I learn? Givens, it turns out, would be the target of dozens of lawsuits. Still, his book taught me that I could be my own financial advisor. Yes, little old me, the kid from Iowa without much of an education. If my financial life was to improve, then I had to improve and that meant educating myself.

After finishing that book, I picked up another one, and then another and then another. Slowly, I was starting to connect the dots. After a few months, it was time to take action. I began by putting together a net worth statement.

I’d never heard of a net worth statement before I started reading about finance, but I now knew I needed one. What did I find out when I completed it? I was 25 years old and broke. Financial illiteracy got me here and, if I was ever going to get out of this situation, I had to change my ways. I did.

My next big decision dealt with my broker, who had sold me the expensive mutual fund. I walked into his office and politely told him to redeem my shares in the fund that made him more money than me. The life insurance agent was next. I told him to cancel the whole-life policy that I didn’t need.

After that was debt. I cut out unnecessary spending, and paid off my car loan and credit card debt. This was a big moment in my life, not just my finances. My mindset was changing quickly. As best I could, I tried to do what was smart. I ramped up my savings rate and focused on stock index funds. There were times I was saving more than 30% of my paycheck and in some years 50%.

Financial freedom. Fast forward to age 45. That was the year I left one world and entered another. I had reached financial freedom, thanks to years of diligent saving coupled with the pension I earned after 26 years in the Army. Financial literacy, followed by action, took me to a place where I no longer needed to work. This became a turning point in my life.

I’m not sure I even understood what the term financial freedom meant. I just kind of realized that I could let go of the urge to make more money and begin doing other things with my time. This is when I started focusing more on something bigger.

I read Your Money or Your Life by Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin. I started to realize there was more to this issue than just money and spreadsheets. The book taught me about the importance of enough and the fulfillment curve, and how it all worked. It also taught me the importance of giving.

About five years prior, I had found $100 on the ground and, instead of banking it as I usually did, I gave it to a woman who had her house broken into. The thief had stolen Christmas presents from under her tree. It was sad, so I dropped by and gave her the $100. She cried and so did I. That changed me.

That moment came rushing back to me as I read Your Money or Your Life. I had found the missing piece of this journey. It was in giving back that I found my soul, and the meaning and purpose in my life. It was time to pay it forward.

A few years later, I would learn about Joseph Campbell and “the hero’s journey.” I found it fascinating how we could lead a well-lived life by following our bliss. I committed to following my bliss as I circled back to help others, so they too could be the hero of their own journey.

Financial happiness. I went back to school and picked up a bachelor’s degree from the University of Northern Iowa, focusing on understanding people and their emotions around this thing called money. While I was there, I decided to start helping young people with their finances.

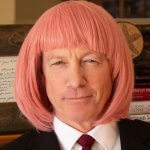

I wrote four books, attempting to help people better understand the connection between their finances and a purpose-driven life. These books were my way of helping others see a world that I didn’t know existed prior to my true beginning. In the process, I became “the crazy man in the pink wig.”

Where did that come from? One day, I put on my three-year-old great niece’s pink wig to make her laugh. It worked. Her mom took my picture and I made it my Facebook profile page. Soon, people were calling me that crazy guy in the pink wig. The proverbial light bulb went on: It was my future identity.

I had been leading a “crazy” life for a long time—rejecting materialism, and the debt and stress that goes with it, saving a good chunk of my money, investing in index funds and basically charting my own course. To many people, I appeared crazy. To me, I was the least crazy person in the room.

I now had a visual image that folks couldn’t forget. I encourage people to be as crazy as I am. To wear the pink wig—metaphorically or literally—is to be willing to be your own person, think for yourself and, ultimately, live the life you were meant to live instead of one that others have selected for you.

All the while, I began consuming books at an accelerated rate. I starting learning from the right teachers: Warren Buffett, John Bogle, Burton Malkiel, Charles Ellis, William Bernstein, Jane Bryant Quinn, Rick Ferri, David Swensen, Daniel Solin and a guy by the name of Jonathan Clements.

Through some self-reflection, I realized I had learned something that went far beyond finances. I learned about how to find meaning in my life, and that involved giving. I designed my future life around helping others with the talents I’d acquired, and that was made possible by the financial freedom I’d achieved.

I’m now approaching 60 and have spent the past 14 years helping individuals and organizations improve their financial situation. I do it for free because I can and because it feels so very good to help others. My next venture: I’ve decided to start The Giving Solution, so I can further spread this message of helping others.

The Giving Solution is an opportunity to help folks who have little to no money, those who are relegated to the end of the line when receiving financial help. We’ll have a list of “givers,” including dieticians, doctors, lawyers, mechanics, disability experts, therapists, dentists, teachers and clergy, who are ready and willing to help others for free. The organization officially kicks off in January 2024. Crazy? I don’t think so. TheGivingSolution.org website is currently being built, so stay tuned.

Mike Finley is the

author

of four books: Financial Happine$$, What Color Is the Sky, Graduation! and Now What? You can learn more at

CrazyManPinkWig.com

. Mike provides free financial classes, presentations and one-on-one counseling to individuals and organizations throughout the world. Follow him on Twitter @CrazyManPinkWig.

Mike Finley is the

author

of four books: Financial Happine$$, What Color Is the Sky, Graduation! and Now What? You can learn more at

CrazyManPinkWig.com

. Mike provides free financial classes, presentations and one-on-one counseling to individuals and organizations throughout the world. Follow him on Twitter @CrazyManPinkWig.The post Free to Give appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Learned on the Job

IT'S A COMMON BELIEF that a young person’s first job is important because it teaches life lessons about work and the value of money. There’s a reason this belief is so common: It’s largely true.

Still, letting a young person loose in the world to learn lessons isn’t as straightforward as you might think. I learned the following seven lessons from my first job—some useful, some decidedly less so.

Lesson No. 1: Avoid Celery

My first job was picking strawberries. I thought this was a real job because it lasted for the whole season—several weeks—on a real farm. I was 10 years old.

Early each morning, an old school bus owned by the farm drove through town stopping at certain locations to pick up whichever kids wanted to work. The bus would take us to the fields. We’d get paid at the end of the day, and the bus would drive us back to where we were picked up.

I’d get up a little before 6 a.m. and make myself lunch: a sandwich, an apple, a piece of cheese, orange Tang in a thermos—just like the astronauts—and, because my mother said I had to, some sort of vegetable, such as a carrot or celery stick. Then I’d walk the eight blocks to the country store where my bus stop was.

Work lesson No. 1: I really didn’t like eating celery. The kids often traded food at lunch, but nobody liked celery. It was a worthless bartering item. After I stopped picking strawberries, it was another 40 years before I ate any more celery. When I did, it tasted pretty good. The celery lesson was a bum steer.

Lesson No. 2: Who Makes the Rules

By the second half of my first day, I did learn something about work. We picked strawberries into wooden containers called flats. When you filled the flat, you took it to the scales at the edge of the field. If your flat weighed enough, your pay card got punched. If it didn’t, you had to go back to your row and pick more berries to fill it.

I noticed right away that if your flat was heavier than the minimum, they didn’t let you take some berries out and put them in your next flat. Variations in the weight of your flat didn’t count unless they counted against you.

Work lesson No. 2: In jobs, the guy writing the checks makes the rules.

Lesson No. 3: Class Struggle

It took two years before I started pondering the fact that not all of my grade-school classmates picked strawberries. The people in my town seemed uniformly similar to me until then. But in truth, there were economic class differences. Yet even after I realized that some kids spent the summers swimming at the country club and others worked picking strawberries, I didn’t think much about it. I liked some country club kids and didn’t like others, and the same for the kids who picked strawberries. Not only that, some of the kids picking strawberries were from families with country club memberships.

Work lesson No. 3: I saw no consistent correlation between a person’s character and how much money their family had. That was a useful life lesson.

Lesson No. 4: Managing Managers

Looking back on it, I’m pretty sure that the farm was picking up kids to work mostly as a public service, giving every kid in town who wanted it the chance to work. They were building character through the economic miracle of child labor. If you had asked me if I thought my character was being improved as I inched my way down a row of strawberries on my hands and knees, picking clean as the beating sun turned the dirt to dust, I probably would have just laughed at you.

One day, I noticed the foreman looking over my row. The foreman tended to check anyone further along in their row than other kids to make sure the fast kid was picking cleanly. When he reached me, I was sitting in the dirt, eating my sandwich, even though it was only 10:30 a.m.

“What are you doing?” he said. A good sign: If he found spots I hadn’t picked well, he would have said that first.

“I got hungry, so I’m eating,” I said. I held out my punch card. “I’ve already picked more than the day’s quota. I’ll pick some more, soon as I’m done eating.”

He tilted his head, pondering this. “Okay.” He walked off to check someone else’s row.

Work lesson No. 4: Do your work faster and better than other people, and eventually management leaves you alone.

Lessons Nos. 5 and 6: Seeing and Believing

A couple of years into strawberry picking, I noticed that Susan Dooley also picked strawberries each summer. She was in my grade. Seeing her pick strawberries, while also sometimes surreptitiously eating one, caused me to suspect for the first time that “girl germs,” a widely believed-in and much-feared phenomenon amongst my male peers, was not real.

I was shocked by this thought, because everyone knew about girl germs. But then Susan Dooley would eat another strawberry and the whole idea of girl germs suddenly seemed stupid.

Work lessons Nos. 5 and 6: You don’t have to believe in an idea just because someone else does, and you don’t have to keep believing what you believe if sufficient evidence tells you you’re wrong.

Lesson No. 7: The Road to Riches

At the end of the day, the farm’s family matriarch set up a card table at the edge of the field with a cash box on it. We’d file by and give her our punch cards, and she’d pay us in cash.

When I was dropped off at the country store after work, I’d go in and spend some of my earnings. Many kids spent much of their money, but I had a system. I’d spend whatever change was left above the last half dollar. If I made $9.70, I’d spend 20 cents, saving the $9.50. If my spare change one day wasn’t enough to get what I wanted, I’d add it to the next day’s spare change and spend it then.

The good comic books—Spiderman, Fantastic Four, The Hulk, The Silver Surfer—cost 15 or 25 cents, depending on the issue size. Big Hunk candy bars cost five cents. At the end of each season, I put all of the money I’d saved in a savings account. I was saving for college.

When I went off to college, I decided to sell the comic books. To my surprise, by then they were worth about twice as much as all the money I’d saved from three seasons of picking strawberries plus the interest earned on those savings.

Work lesson No. 7—the most rigorously data-based lesson from my first job—was: Saving money doesn’t pay. Comic books are the true road to riches. This was likely not the lesson my parents were hoping I’d learn from my first job. But fortunately, unlike the “avoid celery” lesson, I didn’t wait 40 years to unlearn the “saving money doesn’t pay” lesson.

David Johnson retired in 2021 from editing hunting and fishing magazines. He spends his time reading, cooking, gardening, fishing, freelancing and hanging out with his family in Oregon. Check out David's earlier articles.

David Johnson retired in 2021 from editing hunting and fishing magazines. He spends his time reading, cooking, gardening, fishing, freelancing and hanging out with his family in Oregon. Check out David's earlier articles.The post Learned on the Job appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 3, 2023

Mastering Retirement

Guaranteed income is reliable income that isn’t affected by changes in the stock and bond market, and it includes pensions, Social Security and income annuities.

If you’re fortunate enough to have a pension, there might be choices regarding survivor benefits and whether you want to accept a lump sum instead of regular monthly payments. Retirees usually have just one chance to get these decisions right, and choosing poorly can have lifelong implications. Take it slowly, and involve your spouse and financial advisor in these decisions.

Similarly, claiming Social Security is usually only done once, though there is a 12-month window to redo your decision, providing you pay back every cent of benefits received. A bad choice—say, claiming too early—can crimp income for life. Unlike a pension, however, Social Security survivor benefit rights can’t be waived and there’s no lump-sum withdrawal option.

A third source of guaranteed income is annuities. There are many options to choose from, but most HumbleDollar readers say “no” to all because so many annuities are accompanied by high fees and commissions. Still, if you want to boost your guaranteed income, an immediate-fixed annuity could be worth investigating.

Medical expense planning necessitates understanding health savings accounts (HSAs), Medicare and long-term care insurance. In the years before retirement, it might be possible to accumulate significant money in an HSA for your retirement medical expenses. In 2024, for example, a couple age 55 and older could together save $10,300 if they enroll in a high-deductible insurance plan.

Medicare, which typically provides health insurance starting the month you turn 65, has many options and parts to understand. When to sign up and which plans to choose are only “simple and easy” if you do your homework.

Long-term-care insurance has become expensive, as insurance companies abandon the business or jack up their premiums after underestimating the amount and duration of claims. More folks would likely insure for long-term-care expenses if these policies weren’t so expensive.

Tax-free accounts allow workers to amass a nest egg and then use 100% of the money saved to cover their retirement expenses. But instead, many workers favor tax-deferred accounts, thereby postponing taxes until withdrawal, in a bet their tax rate will be lower in retirement.

That may not always be a winning strategy. Thanks to required minimum distributions and potentially higher tax rates after 2025, it could pay to have more money in tax-free retirement accounts. The three tax-free accounts available are HSAs, Roths and cash-value life insurance.

HSAs are doubly tax-advantaged, offering a tax deduction for contributions and tax-free withdrawals when the money’s spent on medical expenses. Roth accounts are excellent for those still working, even though savers must forgo the current year's income-tax deduction. Early in retirement, when taxable income is often low, it can be wise to convert a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA so that the money and its potential earnings won’t be subject to taxation again.

A third tax-free account is the cash value in a life insurance policy. If you have a whole-life policy, it might be possible to borrow against the cash value and spend the money without paying taxes. Of course, whole-life premiums are a whole lot higher than those for term insurance, so you could pay a high price for its tax advantages.

Asset allocation refers to how we divide our investment money among key investment categories like cash, fixed income and stocks. Having ready cash in retirement is helpful so you don’t have to sell investments at a loss during a market downturn. With savings accounts paying 4% and more, cash is currently a more attractive option than it’s been in a decade.

Fixed-income investments include certificates of deposit, bonds and bond funds. They serve two purposes: Their prices are usually more stable than stocks and they provide an extra dollop of current income. Just remember, bonds and bond funds lose value when interest rates rise, as we saw in 2022.

Stocks provide the potential for growth, income from dividends and the capital for major purchases like a new car. Just don’t get too myopic about them. Too many investors make stocks their sole focus, when cash and fixed income deserve their money and attention as well.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.The post Mastering Retirement appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Aging Well

LIKE MANY IMMIGRANTS living in the U.S., I regularly return to my hometown to visit family and friends. My trips to Kolkata are usually short and jam-packed, seeing not just contemporaries, but also the older generation, including aunts and uncles, my parents’ friends and my friends’ parents.

My two recent visits—one last fall and the other this spring—were no exception, but I had mixed feelings this time. Most of the older generation are now in their 70s and early 80s, and two of them had passed away since my last pre-pandemic visit. I was happy to be able to catch up with the rest. But I was also saddened and surprised to find that, since my last visit, a few didn’t seem to be doing well emotionally, as if they’re struggling to find meaning in life.

On the surface, health problems and mobility issues are to blame, but that alone doesn’t explain such a change within a few short years. With most of their family members or adult children living elsewhere, these folks have no one to lean on for day-to-day support. They resist getting professional in-home senior care services or moving to retirement communities. This mental block is cultural and emotional, not financial.

Meanwhile, the rest of my older acquaintances seem to be having a great time in their golden years. They, too, face health and mobility issues, but these don’t appear to affect their positive outlook on life.

The best example is my maternal aunt—my mother’s younger sister—whom I call Mashi. Despite dealing with several family tragedies within the past year, including losing her husband of 50 years after a long period of ill-health, Mashi remains upbeat and full of energy. If you were to guess her age based on appearance and activities, you’d probably be off by at least 10 years.

What’s the secret to the higher life satisfaction of these older folks? I’m not sure about the others, but for Mashi, I can think of six factors:

1. Keeping busy with a purpose. I’ve never seen Mashi sitting idle and wondering what to do with her spare time. Words like sedentary and lazy don’t exist in her dictionary. Even at this age, she still feels responsible for the smooth running and upkeep of her household, which includes her younger son and his family, who live with her.

Mashi’s younger son—my cousin—is a doctor, his wife also has a career, and they have a four-year-old son who started kindergarten last year. Both my cousin and his wife assist with the household’s upkeep as best they can, and there’s also domestic help for certain chores. Still, Mashi is deeply involved with the remaining day-to-day work. It’s almost as if the household would cease to function if she were away for even a short time.

2. Nurturing relationships. Mashi makes a big effort to stay connected with all of her family and close friends—the quality I admire most about her. Her daily routine includes spending a few hours with her grandson, chitchatting with neighbors, talking to her older son’s family—they live abroad—and catching up with my mother over the phone. She’s also regularly in touch with her late husband’s extended family and friends. She rarely misses social gatherings, be it a puja celebration with in-laws, birthdays or special events of friends and acquaintances.

3. Healthy eating. Mashi has resisted today’s lifestyle of junk food and frequent dining out. To be sure, she’s curious about food and doesn’t mind other cuisines for a change. But her staple meals involve homemade food with fresh vegetables, legumes and grains, plenty of fish and occasionally eggs or meat. She loves to make traditional Bengali dishes with seasonal vegetables. Whenever I visit her, I enjoy tasting what she’s making that day.

4. Regular physical exercise. No, Mashi doesn’t go to a health club, swimming pool or any fitness center. Instead, she gets her physical exercise simply by choosing to walk whenever she needs to go anywhere within a one-mile radius. She finds one excuse or another every day to get out of the house for a brisk walk.

Often, the trip involves getting fresh vegetables and groceries from the neighborhood bazaars, picking up monthly provisions from convenience stores, buying a gift for an upcoming family event, or paying a visit to her in-laws who live close by. Even the pandemic lockdown didn’t change her walking habit.

5. Personal time. Despite a busy daily life, Mashi sets aside time to relax. Her favorite hobby is gardening. Living in a congested city, she doesn’t have the luxury of a backyard garden. Instead, she uses her home’s two terraces to grow a variety of plants in pots of various sizes. The small terrace on the second floor doesn’t get much sunlight, and the one on the fourth floor has no shade. She regularly moves pots between the terraces, prunes and weeds them, and treats the soil with tea leaves. According to her, looking after her plants is the most relaxing part of her day.

6. Financial security. Mashi doesn’t come across as wealthy, but she’s financially comfortable, thanks to a lifetime pension, retirement savings left by my late uncle and a decent-sized house. Both her sons are capable of offering financial support, but I doubt she’d ever need or ask for help. She can afford to spend beyond her regular expenses without worrying about outliving her money.

Mashi is in her 70s, but—given that she’s hardly changed since her early 60s—I have a feeling that she’ll be the same in her 80s, too.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.

Sanjib Saha is a software engineer by profession, but he's now transitioning to early retirement. Self-taught in investments, he passed the Series 65 licensing exam as a non-industry candidate. Sanjib is passionate about raising financial literacy and enjoys helping others with their finances. Check out his earlier articles.The post Aging Well appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 2, 2023

Money Shame

AFTER PENNY READ about lower stock market valuations abroad, she bought an exchange-traded index fund focused on European shares. She showed the article to her friend Peter, who purchased the same fund. But the next day, a large French bank reported difficulty meeting customer withdrawals, stoking fear of a bank run.

The U.S. stock market was down slightly, but European shares got clobbered. Penny was disappointed but believed the government would take steps to ease the crisis and vowed to stay invested. Peter was more worried and sold out, berating himself for his inability to manage money.

What’s going on here? Why the difference? Penny grew up in a family where money wasn’t a source of conflict, and that made her feel confident about handling her finances. In Peter’s home, money was a source of friction between a frugal mother and a wasteful father. He emerged from adolescence unsure how to deal with money.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman discovered the phenomenon of loss aversion, which holds that the pain of losing is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of winning. People with backgrounds similar to Peter’s may be even more sensitive to financial missteps, often leading them to pass up opportunities for monetary gain. Peter suffers from a syndrome I’ve come to call money shame.

In my family, money served both as a source of pride and as possible protection from religious persecution. Its importance was magnified by a well-intentioned but overbearing father whose deft money management left me feeling I’d never measure up. I’ve dealt with my money humiliation in professional training and personal therapy, and believe I’ve gained valuable insight into its negative impact on my investing habits, including how I handle my real estate investments.

All landlords grapple with the dilemma of whether, when and how much to raise rents. Increases compensate for many of the troublesome aspects of real estate ownership. Besides capital appreciation, the investor’s ultimate goal is to maximize net income and maintain a steady cash flow. In times of high inflation like now, raising rents is necessary to offset the greater cost of repairs and maintenance. Tenants whose rent payments are chronically late, who constantly complain or who have damaged the unit become prime candidates for an increase.

But a rent increase can also backfire. Some tenants think an increase is an invitation to make more requests of their landlord. The bigger danger is losing a good renter who’s on a tight budget. Departure of a responsible tenant is almost always an unwelcome development and can be a fiasco. The landlord must deal with any issues the outgoing renter was willing to overlook and prime the property for a new occupant.

Often overlooked is the loss of rent for, say, two months to allow time for the ongoing work and the search for a new tenant. By the time you factor in the property manager’s finder fee, you’re not dealing with chump change anymore. To be sure, the bump in rent for an incoming tenant is usually higher than for a continuing one. But what’s a 10% increase on a $1,000 rent when new carpet or paint can easily run $3,000?

Because of the risk of losing a cooperative renter, I rarely raise rent more than 6%, barely enough to keep pace with today’s inflation. What else, beyond the rational fear of forcing out a pleasant renter, might influence my conservative rental policy? I’d like to think my restraint is rooted in part in the empathy modeled by my mother and grandmother. What budget item will the single working mother have to forgo to make room for that rent increase? Yes, concern for others is definitely part of it.

But there may be another factor at work. Perhaps I keep my rent increases small to avoid the painful self-criticism I’d experience if a reasonable renter vacates and sets in motion the money mayhem of re-renting. Am I so anxious to avoid the sense that I’m failing as an investor that it prevents me from maximizing my rental income? Consistent with Kahneman’s notion of loss aversion, I’m face-to-face with the consequences of my need to avoid the money humiliation I experienced as a teenager.

You certainly don’t have to own real estate directly to be familiar with the discomfort of money shame. Suppose you’re a long-term buy-and-hold investor in broad market index funds, but you expect the Federal Reserve will soon cut interest rates. You yield to the temptation to make a sector bet on beaten-down real estate investment trusts. Instead, a surprise increase in the Consumer Price Index results in another hike, battering your real estate fund.

How is your mood affected? Are you awash in self-reproach? How long do you ruminate over the reversal of fortune? Your answers to these and similar questions will tell you how susceptible you are to the money humiliation syndrome.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

Steve Abramowitz is a psychologist in Sacramento, California. Earlier in his career, Steve was a university professor, including serving as research director for the psychiatry department at the University of California, Davis. He also ran his own investment advisory firm. Check out Steve's earlier articles.

The post Money Shame appeared first on HumbleDollar.

He Got Us to Diversify

THOSE WHO LIVE VERY long lives sometimes face an unfair irony: The accomplishments of even towering figures can lose their luster over time—not because they’re proven wrong, but because the ideas they developed become so widely accepted that we forget they were once innovations. The investment world lost one such towering figure last week: the economist Harry Markowitz, who was age 95.

Markowitz first came to prominence in the early 1950s, when his PhD thesis, titled “Portfolio Selection,” offered an entirely new approach to investing. Prior to Markowitz, what constituted investment theory would have fit on an index card. For years, in fact, the only framework available to investors was the “prudent man” rule, which had its roots in an 1830 court ruling. At issue in that case was the management of a trust which had been established for the benefit of Harvard College and Massachusetts General Hospital. Over time, the two institutions became unhappy with the trust’s performance and sued the trustee, arguing that he had been negligent.

The trustee prevailed, however. “All that can be required of a trustee,” the court wrote, “is to observe how men of prudence, discretion and intelligence manage their own affairs.” In other words, investment markets inherently carry risk. All an investor can do, therefore, is to exercise judgment in choosing investments.

This became known as the prudent man rule. Despite being highly subjective, it was the lens through which investments were evaluated for more than 100 years, until the economist John Burr Williams suggested a better way. In his 1937 book, The Theory of Investment Value, Williams developed the concept now known as intrinsic value. Williams introduced the idea with this poem:

A cow for her milk,

A hen for her eggs,

And a stock, by heck,

For her dividends

An orchard for fruit

Bees for their honey,

And stocks, besides,

For their dividends.

In other words, “a stock is worth only what you can get out of it.” And for that reason, share prices should reflect the profits of the underlying companies. While this might seem like an obvious concept today, Williams was the first to see it. This new quantitative approach to choosing investments offered a big step forward from the prudent man rule, which wasn’t quantitative at all.

Williams’s work in the 1930s led directly to Markowitz’s in the 1950s. As Markowitz described it, when he later received the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics, “The basic concepts of portfolio theory came to me one afternoon in the library while reading John Burr Williams’s Theory of Investment Value.”

Markowitz agreed with Williams’s approach to valuing individual investments. It was far better than the old prudent man approach. But Markowitz still saw it as incomplete. The shortcoming: While it’s important to evaluate individual investments, it’s equally important—if not more so—to consider how a collection of investments will work together in a portfolio. Markowitz was the first, in other words, to show investors how to effectively diversify a portfolio.

In his 1959 book, Portfolio Selection, adapted from his thesis, Markowitz provided this example: “A portfolio with sixty different railway securities, for example, would not be as well diversified as the same size portfolio with some railroad, some public utility, mining, various sorts of manufacturing, etc. The reason is that it is generally more likely for firms within the same industry to do poorly at the same time than for firms in dissimilar industries.”

As noted above, today this might seem obvious. But before Markowitz, it had never occurred to anyone. And it wasn’t just a casual observation. Portfolio Selection runs more than 300 pages and is dense with formulas. In it, Markowitz provided a framework for building optimal portfolios—those that offered either the maximum possible return for a given level of risk, or the least possible risk for a given level of return. Markowitz called these portfolios “efficient,” and presented them visually in a diagram he called the efficient frontier.

In the decades since Markowitz developed the efficient frontier, no one has challenged his math, the concept still stands and it’s a mainstay of finance 101 courses everywhere. His theories have received some criticism, though. In particular, many argue that the statistic Markowitz chose to measure risk—the standard deviation of an investment—isn’t valid.

Standard deviation, also known as volatility, is the degree to which a stock’s price tends to move in a relatively straight line or to bounce around. Consider the stock of a company like Procter & Gamble. P&G’s business is relatively stable, and thus its stock price is quite steady compared to the overall market. Now, let’s compare that to Amazon.com’s stock. Reflecting the business that it’s in and its growth rate, Amazon’s share price acts more like a roller coaster. From a mathematical perspective, Amazon’s stock has been far more volatile. But which would you have wanted to own?

Over the past 10 years, P&G’s stock has gained 154%—not bad. But Amazon’s shares have soared nearly 830%, reflecting its enormous profit growth. Through the lens of modern portfolio theory, however, we would deem Amazon’s stock very risky simply because it’s bounced around so much. Many see this conclusion as nonsensical. While Amazon may be an extreme example, it illustrates why volatility is a controversial idea.

While I agree that it’s difficult to distill risk down to a single number, this criticism is also a little unfair. That’s because, in his 1959 book, Markowitz explained why he chose volatility as a risk yardstick: “...for conservative investors, a loss of 2L dollars is more than twice as bad as a loss of L dollars.” Investors, in other words, are human. We really dislike losses. The uncertainty of a volatile stock can be upsetting, and the reality is that stocks like Amazon don’t only go up.

We saw this just last year. In 2022, when the S&P 500 dropped 19%, Amazon’s shares lost more than 50%, while P&G’s shares dropped less than 5%. It’s not hard to see why Markowitz saw volatility as being a reasonable proxy for risk. He was acknowledging that investors have emotions. In his book about risk, Against the Gods, Peter Bernstein notes that more volatile stocks have been more prone to permanent loss, so there’s both an emotional and a quantitative justification for that metric.

Over the years, others have tried to develop alternative risk measures. But as I discussed earlier this year, there is no single perfect measure. Each provides a different perspective. I find it helpful to consider different risk measures as a mosaic, allowing investors to form a more complete picture. It’s to Markowitz’s credit that he was the first to use any quantitative measure at all in attempting to assess risk. While volatility isn’t perfect, it’s certainly more rigorous than the old prudent man standard.

Putting aside this question, Markowitz’s lasting contribution is that he taught investors how to think about diversification, and few people debate that.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post He Got Us to Diversify appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 30, 2023

Look Inside

AS WE MANAGE OUR financial life, we’re compelled to cope with heaps of uncertainty—which way the stock and bond markets will head, what financial misfortunes will strike, how long we’ll live and so much more.

But there are also ways we can exert a measure of control: spend thoughtfully, save diligently, keep a close eye on risk, hold down investment costs and manage our annual tax bill. To this list, I’d add one other key way to reclaim the advantage: have a good handle on who we are.

To that end, below are nine questions I believe we should all try to answer for ourselves. As you’ll see, the questions often probe the same issues but from different angles.

1. What does money mean to you? There are all kinds of possible answers: security, control, freedom, power. If you have a good grasp on your overriding financial motivation—and not just specific goals like retiring early or amassing $1 million—you’re likely to better understand why you make the decisions you do.

2. Are you more concerned with getting rich or not being poor? This is less an either-or answer and more about figuring out how much weight you put on each. Even if your overwhelming desire is to grow wealthy or avoid poverty, that doesn’t mean that wish should always guide your behavior. Instead, you should ask whether your intense focus is leaving you open to financial peril, such as carrying too little insurance because you’re so oblivious to risk or investing too conservatively because you’re so concerned about losses.

3. What’s your investment risk tolerance? This is obviously related to the prior question. The big problem: Risk tolerance isn’t stable, instead rising and falling with the financial markets. Still, this is a great time to ponder the issue, while 2022’s stock and bond market slump are fresh in our memories. In reaction to last year’s plunging markets, did you sell, sit tight or buy more?

Your behavior is likely the best indicator of your true risk tolerance, and it should guide your mix of stocks and conservative investments in the years ahead, even if recovering markets tempt you to take more risk. My suggestion: Think of your portfolio as two parts, one offering downside protection and the other giving you upside potential. How much safe money do you need so you feel comfortable with that portion of your portfolio that’s at risk of steep short-term losses?

4. What’s your personality type? Psychologists have identified five key personality traits: extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism and openness to experiences. We all have these traits in varying degrees.

Where do you stand? Fortunately, there are free online quizzes available where you can get the answer—and knowing the results may help to improve your money management. For instance, a 2023 study found that personality was useful in explaining folks’ willingness to invest in stocks, while a 2022 study uncovered a link between personality and those who are self-made millionaires.

For a different, more specifically financial lens on the same issue, check out the money scripts developed by Ted and Brad Klontz. As you do, think about how your past—especially the way you were raised—influences your behavior today. Just as many HumbleDollar readers likely score high on “conscientiousness” in the personality tests, I suspect many will identify as “money vigilant” among the four money scripts.

5. What behavioral mistakes do you make? When psychologists look at personality and behavior, they tend to take a bottom-up approach, focusing on the individual and his or her unique characteristics. By contrast, economists tend to be top-down, often analyzing large data sets as they look for commonalities that explain the behavior of a wide swath of the population.

For instance, economists have identified a slew of biases that influence our financial behavior. Which behavioral finance pitfalls do you fall into? You might peruse Greg Spears’s .

The same top-down view comes into play when economists look at happiness: They’re less focused on what makes any one individual happy or unhappy, and instead try to identify common factors that influence the life satisfaction of a large portion of the population. You can read about some of those factors in this article. Ask yourself: Are your actions hurting your happiness?

6. What are your bad habits? We all have weaknesses as well as strengths. That’s just the way humans are. Are your weaknesses—perhaps spending too much, eating or drinking too much, failing to exercise—threatening your future? If so, you should look for ways to combat your weaknesses by developing better habits. That’s not easy to do. But both Rick Connor and Dana Ferris recently offered some intriguing suggestions.

7. What do you value? Rather than simply articulate what you think you care about most, examine the way you use money, especially your discretionary spending. How do you divvy up those spare dollars among savings, purchasing possessions, buying experiences, giving to family and donating to charity?

Let's say you save heavily. That suggests a concern with financial security. Meanwhile, if you devote hefty sums to buying experiences, that might indicate a greater curiosity about the world, and perhaps a desire to spend more time with others.

8. What gives your life purpose? What will give it purpose in the future? This can provide the motivation to make financial sacrifices today. It’s also an important issue as we approach retirement and ponder how we’ll use our remaining time. Mike Drak recently wrote about the Japanese notion of ikigai and how you can use it to identify your life’s purpose.

9. If you had five years to live, what would you change about your life? This is one of three questions posed by George Kinder, a founder of the life planning movement. I find it a powerful question because it forces us to consider whether we’re devoting our time to the things that matter most to us—which, if you’re like me, would include friends, family and pastimes you’re passionate about.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier articles.The post Look Inside appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June’s Hits

When should you retire? Dennis Friedman lists nine financial factors to consider.

Tempted to act on the latest stock market forecast? No matter how alarming or authoritative the prediction, your best bet is to tune it out, says Adam Grossman.

If you're about to buy some shiny bauble, "think about past purchases of nice-to-have things," advises Dick Quinn. "Do you even know where they are? Keep in mind your kids won’t want them when you’re gone."

To simplify his financial life, Mike Zaccardi closed a slew of financial accounts and consolidated almost everything at one brokerage firm. That resulted in six key benefits—plus a $700 new account bonus.

"Never did we foresee a retirement of cleaning houses, making beds and doing laundry for up to 16 guests a week," says John Yeigh. "Our duties include restocking firewood, repairing what breaks and occasionally rescuing tenants on the water."

How did Dana Ferris bring order to her finances, while also losing 60 pounds? She credits building better habits—with a big assist from automation.

If you want to protect yourself from cybercrime, take three relatively simple steps, says David Powell.

"Our net worth climbed and climbed," writes Ken Begley. "But in the process, we fought over money more and more because saving became an obsession for me."

Two years ago, Rick Connor and his wife moved to the house where they planned to spend their retirement. Now, they're wondering, should they move again?

"Renee came to me in sixth grade and asked, 'Daddy, when I go to college, you’ll pay for it, won’t you?'" recounts Ken Begley. "I looked into my daughter’s beautiful brown eyes and said, 'No, we won’t.'"

Meanwhile, our two most popular Wednesday newsletters were Brian White's Closing the Door and Kathy Wilhelm's Better Things to Do, and the two best-read Saturday newsletters were Ask Before Quitting and Begging to Differ, both written by me.

The post June’s Hits appeared first on HumbleDollar.

Why I Retired

IT TOOK FIVE FALSE starts to write this column. Each time, I’d inundate readers with information. So, here’s a sixth try.

Have you ever seen those questions to financial advisors on the internet that say, “I have [insert dollar amount]. Can I retire?”

How the heck could the advisor give a reasonable response? To answer the question, it takes more than simply knowing how much you have in the bank. You need a lot of personal and financial information to make the decision to retire. Much of it has to do with personality and family situation.

Let me tell you how I decided to retire at 60. Retiring at that age wasn’t my plan. But I came to the decision that it was for the best. Here’s why.

I’ve generally had at least two or three jobs for most of my working life. I’m not a workaholic. But you do what you have to do when you have a good wife and five kids.

My wife Cindy and I have contributed to 401(k)s and IRAs for decades. She stayed at home to raise our kids for 12 years and she’s nine years younger than me. She works at a local bank as a teller. Cindy plans to work until age 59.

Our ace in the hole for retirement has been my pension from 43 years of active and primarily reserve military duty. The pension started at age 60, increases each year with inflation, is larger than my future Social Security check and includes a family medical insurance plan through Tricare. We have no debt and we had two children in college at the time I retired. Both were covered by scholarships then and both are now employed.

My last civilian job was working as an accountant for a company that printed magazines. Well, paper and ink had a good 2,000-year run, but that has been rapidly ending with the invention of the internet. The company had been dying a slow, painful death. That’s just the way it was.

Many jobs were done away with over the years. But that was not the case with me. I watched folks above and below me get pink slips. Then their work would fall on my desk. I seemed to have had two important attributes: I could get the job done and I was a bargain. I never got paid overtime because I was salaried, and yet I did endless overtime.

All the overtime and stress at a company that appeared to be on the road to bankruptcy was affecting my health, with high blood pressure and other medical problems. But I just couldn’t seem to pull the trigger and retire. The plan was to bank my military retirement checks and work until at least age 65.

Then one Sunday, which was routine for me, I was at the plant and a supervisor I knew came by my desk. We got to talking about retirement. I mentioned that I could retire if I wanted to. I had run the figures once, and then had a financial advisor see if he agreed. He did.

My friend looked at me in astonishment and said, “Ken, why are you here on a Sunday if you can retire? This isn’t a dress rehearsal for life. This is it. You don’t get a second chance.”

He was right. If you enjoy what you’re doing, then by all means continue to work. It will probably extend your life a lot more than retiring. But if you have the means to retire and you really don’t like what you’re doing, it’s time to go. The extra money you make might not pay for the medical bills that could result from your decision to stay. You only have a limited number of years in what I call your “life bank.” Don’t spend most of this bank account doing something you don’t want to do.

Retirement worked for us. Our marriage got stronger by bringing down our family stress level. I do all the housecleaning, laundry, dishes, mowing, grocery shopping and 1,000 other little tasks around the house. Cindy trusts me with everything but cooking. Smart girl. All Cindy has to do is commute two miles to work and come home in the evening. Also, we eat out a lot. Smart boy.

Sometimes, retirement is the best answer.

Ken Begley has worked for the IRS and as an accountant, a college director of student financial aid and a newspaper columnist, and he also spent 42 years on active and reserve service with the U.S. Navy and Army. Now retired, Ken likes to spend his time with his family, especially his grandchildren, and as a volunteer with Kentucky's Marion County Veterans Honor Guard performing last rites at military funerals, including more than 350 during the past three years. Check out Ken's earlier articles.

Ken Begley has worked for the IRS and as an accountant, a college director of student financial aid and a newspaper columnist, and he also spent 42 years on active and reserve service with the U.S. Navy and Army. Now retired, Ken likes to spend his time with his family, especially his grandchildren, and as a volunteer with Kentucky's Marion County Veterans Honor Guard performing last rites at military funerals, including more than 350 during the past three years. Check out Ken's earlier articles.

The post Why I Retired appeared first on HumbleDollar.

June 29, 2023

Not So Rewarding

WE TRAVEL A LOT, so I try to read up on new places, new deals and what to watch out for. This year, I’ve made two new discoveries—not pleasant ones.

I admit it, I love hotel points. I know I’ve paid for those points, but seeing a “free” hotel bill makes me feel good.

Hotels started their rewards programs when I was traveling for business. I signed up right away. In fact, my rewards account number with one hotel chain starts with 000. My employer at the time let us keep the points we accumulated. Between the hotels and the airlines, my husband and I had some great trips.

We generally have our vacations planned out at least a year in advance. Now, I’m learning that—when you’re using points—planning ahead can have unintended consequences.

Taylor Swift performed in Philadelphia in May. A woman from another part of the country had reserved a room four months before the night of the concert using points from a hotel loyalty program. A month before the event, she received an email from the hotel informing her that it was canceling her room reservation due to “system availability.”

How can a hotel cancel a guaranteed reservation, especially one made so far in advance? If you prepaid for a room, the hotel is under contract to honor it. But it seems a confirmed reservation made with points doesn’t carry the same legal obligation. The Pennsylvania lodging laws were written in the 1950s, before points existed, so the hotel was able to cancel her reservation.

It seems obvious what happened here. Once the concert was announced, the hotel knew it could make much more from the room. You can read an account of the incident here. After the situation received some publicity, the hotel backtracked and reinstated the reservation.

That isn’t the only item that recently caught my attention. Whether you pay in points or not, check your bill before leaving the hotel. The Wall Street Journal reported on an incident at an Arizona resort. A man received an email receipt that included a $10 bellman gratuity, a $22 credit card processing fee and a $3 daily maid gratuity—all this after he’d left the maid a generous cash tip.

The post Not So Rewarding appeared first on HumbleDollar.