Jason Micheli's Blog, page 91

March 7, 2022

The House (of the Lord) Always Wins

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I was sitting in the waiting room at my oncologist’s office, an imposing volume of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics on my lap, waiting for what my medical team euphemistically calls maintenance chemo.

On almost every visit, I’m the youngest person in the waiting room— a point of irritation which I often express to the Lord with less than sanctified language.

But on this day, an Indian family was sitting across from me, a middle-aged husband and wife.

Their daughter, no higher than my elbow, snuggled in between them.

The little girl’s eyes looked hollow with exhaustion, her once tan skin almost translucent, and her dark hair already nearly as thin as mine.

As the mother brushed the girl’s hair with her hand and whispered assurance into her daughter’s ear, I noticed a silver cross hung from her neck and lay draped against her blouse.

For her part, the girl calmly looked at the glossy pictures of far away places in a wrinkled back issue of a travel magazine.

When a nurse with a clipboard called the family’s last name, they stood up and gathered their things.

“Good luck,” I said to them.

I’d only meant by it a show of camaraderie, like we’ve all been drafted as teammates for a sport none of us wants to play.

“Luck?” the girl’s mother said like she hadn’t heard me right.

I nodded and gestured to the infusion lab, “Good luck.”

The mother shook her head with a look.

It was just shy of disdain— surprise, I’d say.

She glanced at the book on my lap and then looked at me, as if wondering why anyone would read such a book— Church Dogmatics— if they were not a believer.

“Good luck,” I said again, thinking maybe their English was the problem.

This time the girl’s father shook his head.

“We’re Christian,” he explained, as though he was unpacking a lesson as elementary as the Golden Rule, “We don’t believe in luck.”

And with his arm around his little girl, rendered rail thin by life-saving poison, they walked into the infusion lab as though from another world.

I should’ve known better than to speak of luck.

When I was a chaplain at Trenton State Prison, every Friday I made the pastoral rounds to those in solitary confinement. Don’t let the Shawshank stories mislead you. For the most part, the men in solitary were the most unpleasant, unrepentant lot you could imagine. All claimed to be innocent. All stretched the edges of my Christian mercy, and all were surely that way before they were isolated for all but an hour a day.

On one of my first shifts, after I got buzzed through the double lock-up doors, I presented my identification badge to the officer in charge, Officer Baltimore, and he began to sign me into the register. Officer Baltimore was built like a linebacker. The only thing bigger than his torso was his smile. I introduced myself. He called me reverend. Come to think of it, he may be the first person ever to address me by my office. At the time, the title made me uncomfortable and so, feeling awkward, I tried to change the subject.

“Not very lucky are you, getting this assignment?”

“Lucky?” he said, surprised, “You know, reverend. Surely, you know? Chance has got nothing to do with it. There’s a reason I’m here. I don’t know it, YET, but there’s a reason I’m here.”

We were within arm’s reach of one another but it was like we were worlds apart.

Harvard geologist Stephen Jay Gould argues that you can look to two different pieces of art in Florence, Italy to grasp our two, often overlapping, sometimes colliding, worlds, the world of the Bible and the world after the scientific revolution. Gould writes:

“Scene one: A painting by the 15th century artist, Michelino, hangs in the great cathedral of Santa Maria Del Fiore. It shows the entire universe on a single canvas, the earth occupies the center, symbolized by Florence. At Dante's right, the souls of the damned move downwards to the inferno, while those to be saved slowly mount the spiral of purgatory. The seven semi-circles at the top are the seven planets of Ptolemy's earth-centered system.

For scene two: Take a short walk to the Franciscan Church of Santa Croce, and find the tomb of Galileo. The face of the statue of Galileo looks upward toward his now expanded heaven. Galileo holds a telescope in his right hand, and in his left hand, he holds a small insignificant sphere.

Earth.

In just two centuries, the Earth had been displaced from centrality to the peripheral status of a little hunk of stone suspended in the midst of inconceivable empty vastness.”

The same year Galileo died, Robert Boyle, a wealthy student touring Europe, read Galileo's Dialogue Concerning Two Chief World Systems. In reading it, Boyle fully accepted Galileo's heliocentric worldview— our world is not the center of the universe.

Later, when Boyle wrote his famous Disposition about Final Causes of Natural Things, Boyle ridiculed people who still believe God would create something so vast as the universe and something so huge as the sun simply to glorify himself by means of this inconsequential place called Earth.

As a result, Boyle developed a mechanistic view of the universe; that is, the universe is not the sustained handiwork of the Almighty but a great, impersonal, clanking machine, grinding away without recourse to purpose or meaning or direction.

Tellingly, Boyle’s Disposition didn’t do away with God outright. He instead took the Holy One of Israel, smoothed out all his primitive rough patches, and turned him into the god that most Americans with a bachelor’s degree now believe, a kind of divine Steve Jobs who did such a good job in building the universe that he’s now relocated to some celestial Key West. He’d love it if you called from time to time and he hopes to see you one day on the sandy beaches of the great by-and-by but, otherwise, he’s retired.

This is the officially sanctioned and rigorously enforced assumption of the world in which we live and it even encroaches into our theological speech. For example, Rabbi Harold Kushner in his regrettably still popular book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People (FYI: “No one is good but God,” said Rabbi Jesus), is adamant that there is no agency behind the unfortunate events that befall us in our lives. When bad things happen to sinners, it could be caused by other sinners or it might be a simple twist of luck, a glitch in the matrix, or your turn through the gears of this “inconceivable empty vastness.”

What it most definitely is not, Kushner insists, is God.

We modern people have moved from the simplistic realization that not everything that happens in the world happens because God willed it to the even narrower and more dogmatic assertion that God will not and cannot do anything.

I remember as a young pastor—

Betty, a curmudgeonly matriarch in my congregation, suffered a prolonged stay at the University Hospital in Charlottesville due to leukemia. Several times a week for several weeks I drove the forty minutes or so to visit her and at the end of each visit I’d take her hand and pray. And, of course, I prayed the types of prayers that mainline liberal pastors are implicitly taught to pray. I prayed for God to guide the hands and minds of her doctors and nurses. I prayed for the Spirit of God to give her comfort and peace and patience. I prayed for her family to exercise constancy in the face of the decisions thrust upon them.

I remember one evening I was about to launch into just such a prayer when Betty’s needle poked hand clenched my own so hard she left fingernail marks and she gruffed at me in her best altar guild growl, “You drove all this way over the mountain to pray another limp, namby-pamby prayer? Pastor, if you’re not going to pray for the Lord to heal me then get the hell out of here.”

It was a more profound lesson than anything I learned in seminary.

A lesson rendered more powerful when, against the doctors’s forecast, she was healed.

Rabbi Kushner’s book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, is not intelligible in a world with a purposeful, intervening, directing God, but that book remains a bestseller with many imitations right behind it. Is it any wonder then that so many Christians act as though Christianity is little more than our continuing the movement begun by the dead Jesus? We’ve swallowed the worldview handed to us and accepted it on its own terms. We may not be walking around with a telescope in one hand and a hunk of rock in other, but we’ve all largely— if quietly and subconsciously— accepted the premise that if the sun is at the center of the universe then God is not on the scene.

Philosophers today call it the immanent frame; we’re enclosed by the material universe and there is nothing— no one— outside of it.

We must not pussyfoot around the issue.

This is our problem with the Bible.

In the modern world, people think events like suffering or tragedy make belief in God difficult if not problematic. But in the world of the Bible, God claims those very occurrences as occasions for his glory.

“As for you,” Joseph says to the brothers who betrayed him and left him for dead, “you meant evil against me, but God meant it unto good, to bring to pass, as it is this day, to save many people.” Bad things befall Joseph not simply because Joseph is the victim of another’s sin. What happens to Joseph is not chance or happenstance. It’s not simply his turn through the gears of the machine set in motion long ago by the Divine Clock Maker.

It’s not luck.

It’s a different word altogether.

It’s providence.

Providence:

The conviction that by God, despite appearances to the contrary, our world is moving somewhere toward some good, great End, predetermined in the mind of God, though never fully known to us.

Quite obviously, it’s easy to watch the irrational murder and mayhem unfold in Ukraine and wonder if there is any good reason behind anything. And yet, the God who will one day bring history to an end in Jesus Christ is a God who is in control of history. Behind it all, the Bible promises, is not the whim of luck or fate or happenstance. Behind it all is God.

God’s providence.

On Friday I celebrated a service of death and resurrection for Jane Jones and during the funeral we prayed the twenty-third psalm, a text so familiar to us that we neglect to notice how it in no way contradicts what Joseph says to his brothers. The Lord is my shepherd, declares the psalm, who makes and keeps and guides and leads and protects. The Shepherd of Psalm 23 is the subject of all the verbs. Such a Shepherd is the God Robert Boyle believed he had banished, the God who guides.

In Isaiah 45.1-7, the Lord leaves us no room for believing in luck.

It’s a breathtaking account of God’s providence. So much so, it’s hard to imagine a more absolute formula than verse seven, “I form light and create darkness, I make weal and create woe; I the Lord do all things.” Here in Isaiah, what’s left unsaid is that the exiles in Babylon have just taken offense at the Lord’s news that he will use Cyrus— pagan, gentile, ungodly, idol-worshipping Cyrus— as his anointed messiah to redeem the Israelites from captivity.

Taking umbrage with their offense, the Lord responds by claiming sovereignty over everything, all of history. That Yahweh is the Lord of history is precisely what distinguishes him from all the barren deities of the pagans. A god who is the god of agriculture alone, for example, or a god who is the god of fertility only, are by definition not gods over the whole of history. And this context is key to interpreting the verse; otherwise, you’ll end up thinking God creates evil when instead God is claiming final responsibility for everything.

You see, here in Isaiah—

It’s not so much that everything happens for a reason— that still relies upon Robert Boyle’s mechanistic view of the universe. It’s that God’s sovereignty is big enough to include everything— what we do and what God does— and take it up towards the great, good End that the mind of God elected from before all of creation. It’s not simply that all events have one ultimate cause. It’s that God is at work so that all events work towards one ultimate destiny. God’s not speaking of himself as some kind of puppeteer. God’s speaking of his providence, the unseen but majestic hand of God moving and interjecting in history, guiding everything like a Shepherd bound and determined for all he has made to dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

Christians don’t believe in luck because, well, would you want to bet against a God so graciously determined?

The House— the House of the Lord— always wins.

Now, to assert that God in his God’s good providence is at work in the world is not to suggest that the work of God in the world is easy to identify. St. Augustine says that the work of God in our midst is most often a matter of hindsight. As Augustine says, sometimes when you look at your life, it's like looking at chicken tracks in the mud of a chicken yard, these little chicken tracks going this way and that way. It gives no evidence of an agency at work. It just appears messy and chaotic. But through the eyes of faith, gazing back from the perspective of hindsight, says Augustine, you can start to see that the tracks were headed, slowly but steadily towards an End.

You can discern a purpose at work.

Not luck or chance or happenstance.

But the opposite: Providence.

A friend of mine is an Episcopal priest in Texas.

A year ago she lost both her parents in a car accident.

In an essay from this summer she writes,

“Several weeks after the death of both of my parents, I found a photograph I had never seen before. Of course, as the 38-year-old sudden guardian of generations of family photographs, I have stumbled across quite a few of those. But this one was of me.

It was taken by my younger brother. I can tell because the image was taken from a lower angle and is fuzzy. My parents and I are unloading the car in the drop-off section of the Medgar Evers Airport in Jackson, Mississippi. I was to board a plane to head across the country for my first year of college…and I am clutching my childhood teddy bear, a panda I call Matilda.

It was jarring to see my beloved Matilda in the photograph. When I was a child, the Memphis Zoo had a panda bear exhibit, and my grandmother bought me my very own to take home. At four years old, I loved the song “Waltzing Matilda,” and so my most comforting childhood object was born. It was not surprising to me that I took her to college. What unhinged me now was that she had been the first object I looked for in my parents’ home after their death. And I have found myself comforted by her all over again. After thirteen years of marriage, my husband has adjusted to me suddenly bringing a stuffed animal into our marriage bed.

But the photograph was most revealing for what was not there but had also been there all along.

Namely, that even then, God knew about the death of my parents.

People get very anxious when we talk about the will of God in the face of our suffering. We are happy to include God in all of the moments in our lives that have been wonderful or redemptive….But somehow, when it comes to tragedy, we like to say that random things happen for no reason at all.

I am less interested in having a debate about whether or not it was God’s will that my parents would both die in a car accident. Even the phrase “God’s will” can sound like a kind of legal document. So for a moment, let me put the phrase “God’s will” to the side and instead offer this: I believe that God cannot be surprised.

When I see that photo of me from almost exactly twenty years ago, I think to myself that even then God knew, and even then God was preparing us for what was to come.

People mean well when they say that God is uninvolved in the terrible things that happen. But people meaning well does not mean people are well. We all desire for things to fit neatly into the narratives of our own creation, and our spiritual and mental health hugely influence the way those narratives play out. All this is to say, I do not need bad theology when my life is at its worse. It might make the false theologian feel better, but it will make me feel abandoned. When we suggest that God is surprised by the bad things that happen in our lives, then we offer suffering people a creator who has no plan, and no capacity to respond when the bottom falls out. Basically, God becomes me in the photograph. Standing there, gripping a teddy bear, terrified.

When we declare that God is only involved in the good things that happen, we take away divine action in our lives at every level. When we follow such a biblically baseless claim to its natural end, we find a God who does not know what will happen from one moment to the next, a Risen Lord who is somehow taken unawares by the weight of sin that was placed on His shoulders.

In the complicated and surprising work of grieving two beautiful lives, God has made His face to shine upon me. I know this to be absolutely true. God knew this was coming. God has not been surprised.”

Nevertheless!

It is impossible to sit back and watch the heartbreaking, outraging images on our screens and rest content that one day we’ll be able to say, “God was not surprised.”

I’m sorry St. Augustine, but it’s not enough to hear that one day we might look back at the chicken tracks all over our newspapers and discern, as though through a glass dimly, God working all things together for good.

In this complicated life of grief and sin, we don’t want the promise that one day we will learn where God was.

We want to know where God is.

Right now. We want to know with such certainty it’s as good as a promise.

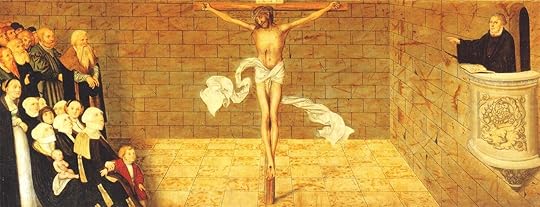

About our text today, Martin Luther says, “To seek God apart from Jesus Christ— that is the Devil.” He means that if we search out the invisible work of the unseen God in our world, if we try to puzzle out God’s providence, we’ll drive ourselves to despair or to insanity. In the here and now, in the midst and mess of all our chicken tracks, we hold fast to where God has promised to be at work.

And God makes that promise in verse twenty-three of this chapter, “By myself I have promised; from my mouth has gone out in righteousness a word that shall not return to me in vain…”

A word, the Lord promises to Isaiah, that one day will bend the knee of every nation and loosen the tongue of every stubborn sinner in praise.

It’s a little word.

A single set of unassuming chicken tracks slowly but inexorably moving forward through the scrum of struggle and suffering of “this present evil age.”

It’s a little word, no more impressive than a stuffed panda.

That word: Your sins are forgiven. The word of grace.

Chances are—

We’ll drive ourselves crazy trying to riddle the invisible doings of the unseen God in a world where all the other evidence would suggest is without God.

Instead, in the here and now, we should seek out God where God has promised to be found: clothed in the Gospel word (“for you”) and as obvious and visible as water, wine, and bread.

So come to the table.

There’s nothing lucky about it.

The odds are even better than flipping a coin.

He has promised that every time, in our present world, this is where you can find him at work.

In you and for you and, then, (possibly) through you.

March 4, 2022

You ARE the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Having pastored for over two decades, I’d wager the number representing the deaths for which I’ve been present hovers at least in the three figures. Most of those vigils were kept for old folks who died in ordinary ways. Many of the leave takings, though, were grim in the circumstances, fraught in the family dynamics, or tragic in the timeliness. Still (and maybe this sounds fucked up for a pastor— or, a human— to say), nothing wrecks me like petting a best friend as she adds her number to life’s near 100% death expectancy.

We said goodbye to Sydney today, an Australian Shepherd named not for the city down under but for the character played by Jennifer Garner.

If you’re an Alias nerd, our surviving dog is named Vaughn. The next surely will be named Sloan or Franny. The silliness of her name and the depth of our feelings for her feels about on par with every other death I’ve stewarded. In dog years Sydney was addled enough to launch an invasion into Ukraine. Truthfully though, she was always crazy and was only ever good according to the standard we all quietly and graciously agreed to set for her (Okay, fine, you can sleep on the bed but not on my feet). But when it comes to man’s best and ever present friend, I think we’re on dangerous ground as soon as we start to use the language of good.

I have thought often, especially so today, about the cliche I’ve spied printed across bumper stickers, in GIFs, and on the pet-themed sweatshirts of the people at the dog parks, “Be the person your dog thinks you are.” How this is a prosperity-pitch is as mystifying to me as the mantra I’ve read scrolled across the screen at the dermatologist’s office (advertising plastic surgery), “Feel as perfect on the outside as you do on the inside.” In the latter cause, the pitch-line provoked me to say, out loud in the waiting room, “If their goal is for me to appear on the outside how I normally feel about myself on the inside, then I’m already as ugly as I need to be.” In the case of the former, the person my dog thinks me to be is not the stuff of aspiration.

My dog knows better than me that my ideal self self doesn’t actually exist; in fact, my dog knows better than me that my actual self isn’t all that far removed from her, drinking from the toilet so vociferously you’d think she was anxious about being forced to share the water.

It’s but an indication of our addiction to what the theologian Gerhard Forde calls “the glory story” that we conscript the creatures who know us best into a schema that tempts us into pretending we’re better people than our canine friends know us to be.

Whoever came up with the canine-flavored, self-help slogan Be the person your dog thinks you are was either dangerously self-deluded or the owner of the world’s dumbest dog, possibly both.

You’re an open book to your dog to a degree you are with few others.

Sydney knew my propensity to fall asleep in the leather reading chair, Cheeto crumbs all over me, only to wake in the middle of the night with the important book I’d meant to read unopened next to me and my thumb on my phone in mid-Twitter scroll. Sydney knew those times when my son, who was little at the time, threw up on the floor and I reacted slowly so as to let her eat it up rather than me having to clean it up. Sydney was there to overhear the irritated mutters one of us in the house exchanged about another, the not very Christian comments I’d make while checking work email, or every four-lettered rage I inveighed against her while she took forever to do her business in the snow or the many times she would irrationally bolt out the door and run straightaway into the neighborhood pool. Sydney surely remembered the time I left her out in the rain, forgetting she was outside, while I wasted two hours of my life going down a rabbit hole of Wikipedia pages about 1980’s professional wrestling.

She heard every fight and false boast and broken promise.Yet every day, as though she possessed some divine amnesia or imputed to us a goodness we have not accomplished, she was there on the sofa to put her head on my lap or to lie against us on the bed.

Much like the One from whom no secret is hidden, Sydney knew exactly who I am yet loved me without condition.

Rather than the glory story lie, Be the person your dog thinks you are, the truth makes the parting sad, Your dog loves the person they know you truly to be.

March 3, 2022

If the Devil Showed Up, I’d have said, “Yes”

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Several years ago now, after the pre-scans of my body and pre-hydrations and pre- medications, around 1:30 a.m. my nurse on the cancer ward started my first six-hour IV drip of Rituxan, a poison normally considered safe only for Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) patients who are “young and fit.”

“‘Young and fit’ minus the, you know, stage 4/5 cancer all over my body,” I muttered to my mom, who was riding shotgun with me that first night.

Not knowing what to anticipate from the Rituxan, I lay there in bed that first night, clutching the sheets in the quiet. Nothing.

I was fine. I couldn’t feel or notice a thing.

By 2 a.m., I was smiling in the dark. At myself. Thinking to myself, Paul Simon’s got it all wrong. The darkness isn’t silent; it’s filled with sound of my awesomeness.

“Who are these sissies,” I wondered to mother, “who complained about how hard chemo is on the body?”

I’m like the Charles Bronson of chemo. I’m like Jules from the lymphoma outtakes of Pulp Fiction. I’m a mushroom-cloud-laying mofo. I’m like the Taken 1, 2, and 3 Liam Neeson of chemo- “weaponry”; I have a very particular set of skills, and kicking cancer’s ass is one of them.

I seriously thought that to myself.

And then BAM. At 3 a.m., ninety minutes in, with no warning at all, I went from zero to sixty in one second flat. My whole body started to convulse, violently, head to toe, shaking my bed and every machine attached to it, splitting open my stomach incision and making my insides feel like they were now my outsides. It was like an epileptic seizure—but one that started not in my brain, but in this dry-ice cold deep down inside my bone marrow.

It was 3 a.m., chemo battle number one, and what did the Charles Bronson of cancer do?

That’s right, he shouted—not really shouted, because the words wouldn’t really come out of his quaking mouth—gurgled for his mommy, who was snoring on the pullout bed in his room. My mom fetched the nurse, who upon entering, blithely responded with “Oh, yes, that’s one of the reactions to the Rituxan,” as she started layering a dozen warmed blankets on me to zero effect.

Reaction? Hives from bad Cabernet is a reaction. A rash from a bug bite is a reaction.

Except actually, I wasn’t thinking. At all. I couldn’t think past the pain the convulsions had erupted all over me. I couldn’t have made heads or tails of a Two and a Half Men episode or a Sarah Palin speech, so bone-wracking was the pain. It was blinding, consuming. A first for me.

It lasted about an hour.

And if you had offered me in any of those sixty minutes anything to make it stop, to take it away, to turn back time—to any of my worst precancer moments—then, damn the torpedoes, I would’ve taken you up on it.

No.

That’s not true.

I love my life. I cherish my wife. And I’m gunning to see my little guys grow up.

I would’ve stuck it out for them, no matter what you offered me.

But, brass tacks confession time: If you told me then the next 150 days would be exactly like that hour and if you could promise me to make it all go away, then I wouldn’t say yes because of the reasons immediately cited above. I don’t think, but

I’d be tempted. And that means I could have said say yes.

A couple of days before I started chemo, my church marked the beginning of Lent by marking their foreheads with ashen crosses, recalling their mortality with the words “From dust you came, and to dust you shall return,” and reading the story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness.

Whenever we picture Jesus tempted by the devil in the wilderness, we usually imagine it in unsubtle comic book lines and hues, with a bad guy readily identifiable as “Satan” and three temptations to which Jesus readily gives the correct answers as though he’s been raised by a Galilean Tiger Mom.

The evangelists tell the story with such Hollywood haste that they effectively turn Jesus of Nazareth into a spiritual prodigy who doesn’t scratch his head over the best way forward.

But not only is such convictional clarity not temptation, it dilutes Jesus into someone less than fully human. It makes Jesus not as human as you or me. I know the Gospels say Jesus was tempted by the devil in the desert, and I believe it. I just think those temptations came to Jesus in exactly the same sorts of unseen, uncertain, ambiguous—human—ways they come to us.

I mean, it’s a no-brainer if you’re posed questions by a guy with horns and a pitchfork. The right answers are obvious; that’s not temptation. Which is to say, I take it as an article of faith that it was a real, live possibility for Jesus to have answered otherwise when the tempter proffered his questions in the desert. Just take another look; the brevity of the stories aside, Jesus spends forty days tackling just three queries. That’s a baker’s dozen days per temptation. There’s more to the story than the story.

We tend to think of faith as something unchanging and immovable, which we can turn to when times get tough or tempting. “He is our Rock,” the praise song repeats ad nauseam. Faith is our North Star, our inner compass, our firm foundation.

But I don’t think so, not since that first night of chemo.

If Jesus is at least as human as you or me, then one of the things Jesus takes on in the incarnation is the contingency of life—not knowing what will drop with the next shoe, what crappy news is a day away, or what will be the best way to deal with it. If Jesus is at least as human as you or me, then his humanity is shot through with the very uncertainty that so often makes our lives seem like a crapshoot. And that means faith isn’t like a rock or a firm, immovable foundation. It means faith is as ever changing as everything else in our lives.

Faith entails change because it’s faith that unfolds in the world God has given us. Faith requires change even, for faith depends upon the always-changing life in which it is lived. In the same way that love and marriage and children and a career change you—and thus your faith—so do pain and dread and fear and despair and temptation change you—and thus your faith.

What makes temptation in the face of faith real is the real possibility of losing the faith you had. The real possibility of failing at your faith or—here’s what you discover is truly scary—finding that your faith fails you when you most need it.

If there’s a silver lining there (and cancer has made me a seeker of silver linings), it’s that “faith is strongest,” as poet Christian Wiman posits, “where the possibility of doubt is greatest.”

“One day down,” I told my mom the next morning, “149 or so more to go.”

I didn’t add how that was nearly four times longer than Jesus was stuck in his own wilderness.

From: Cancer is Funny

March 2, 2022

God Doesn’t Give a Damn

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Every year, every Ash Wednesday, Christians verbally flagellate themselves with King David’s hyperbolic guilt and indulgent self-loathing: “My sin is ever before me…Against you, you alone God, have I sinned…Indeed, I was born guilty, a sinner since my mother conceived me.”

Every year, every Ash Wednesday, the Church drags us through a liturgy that, no BS, derives, from the ceremonies for the reconciliation of grave sinners, like torturers and rapists and conquistadors. And then every year, every Ash Wednesday, the Church invites people forward to receive ashes to remember that from dust— by God’s grace— you came but to Death— by your sin— you deserve to go.

If you’re one of those people who think that when we do good God will reward us, if you’re one of those people think that when we do evil, when we sin, God will punish us, if you’re one of those people then maybe it’s the Church’s fault. I mean, it’s freaking strange that Christians of all people should think this way about God, think that God doles out what we sinners deserve but maybe it’s our fault. Maybe we’ve let the sackcloth and ash mislead you.

Sure, it’s not really odd that other people should think of God this way, think of God rewarding us when we do good and punishing us when we sin. It’s probably the most common way of thinking of God.

Freud was dead-on right.

For most people God is just a great projection out onto the sky of our own interior. Our own feelings. Especially the guilty ones.

But if that’s who God is, rewarding us when we’re faithful and punishing us when we’re sinful, then I don’t believe in Him. And neither should you. God, Jesus preaches again and again, isn’t like that all.

Just take everyone’s favorite parable. The prodigal son goes off to a distant country, far off from his father, and goes on a Tinder binge. Only after he’s penniless does the prodigal see himself for what he is, “I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.”

Here’s a question for Ash Wednesday:

Where did the son get the idea that his father would ever treat his children like hired hands?

Where did he ever get the idea that his father gave his children what they deserved?

Notice how the prodigal son’s sin— his sin— alters his whole relationship with his father.

Alters how he sees his father. Instead of seeing himself as his father’s beloved son, the prodigal sees himself as one who gets the wages he’s earned. Instead of seeing his father as someone who loves without condition, he now sees his father as someone who doles out to his children what they deserve.

His father is NOT someone who doles out what his children deserve— that isn’t who his father is. That is what the son’s sin has done to how he sees his father. His father hasn’t changed. His sin has changed how he sees his father.

Luke repeats it twice.

The prodigal son’s sin is something that changes God into a wage-master, into a judge, into a father who doles out what his children deserve.Sin turns God into exactly who Freud said God was: the projection of our feelings of guilt. Sin turns God into the projection of our shame so that we no longer see the real God at all.

God isn’t a proper name, don’t forget. It’s an answer. Fundamentally, ‘God’ is the answer we give to the question ‘Why is there something instead of nothing?’ a question to which there is never any other answer but grace.

But instead, according to Jesus in Luke 15, our sin turns God into an accuser, a wage master, a judge who weighs our deeds and damns us. When we put forth confession and put on ash, it’s crucial that we stop and notice how so much of our Christian speech and thought is in fact a kind of Satan worship. It’s worship of an Accuser. Which can never be motived by love or joy. Maybe instead of confessing on Ash Wednesday we should lament, lament how, for many of us, because of our sin, the only glimpse of God we ever see is how God looks from Hell. That’s what Christians means by damnation— it’s self-imposed exile.

To be damned is to be fixed forever in this illusion about God. It’s to be so stuck on justifying your self, so shut-eyed towards your sins that you end up seeing our Father as your Auditor in Heaven.

The real God isn’t a kind of Satan, an accuser, weighing your sin to dole out the wages you deserve. The real Father is like this father. And this father, Jesus says, his heart towards his son is no different on the day his son forsakes him than on the day his son returns home to him.

The real God doesn’t mete out reward or punishment according to our merit. Freud was right— that god is a caricature drawn by sin. Our Father in Heaven is like this father, Jesus says, always helplessly and hopelessly loving. God is like a father whose love without condition. Because God— pay attention now— is without change. God, by definition is immutable. God doesn’t change. Therefore, if God does not change, your sin cannot not change God’s attitude towards you.

Your sin does not change God’s attitude about you.

What sin does— it changes your attitude about God.

Sin blinds us, distorts our vision, so that the Father we see is a punitive paymaster, an angry judge, a kind of satan.

Sin matters enormously…to sinners who are ever anxious about settling our accounts and balancing the scales.

Sin matters enormously to sinners, but it doesn’t matter at all to God.

God doesn’t change. Your sin cannot change God.

God, literally, does not give a damn about our sin. It’s we who give the damns. We wish our father dead. We hate our brother. We give the damns.And then we justify ourselves for having done it.Until finally all we can see is a Hell’s eye view of God.

God doesn’t give a damn about your sin. Rather, it’s because of your sin that you see God as damning. God doesn’t mete out what you deserve. Rather, because that’s the currency you pay others, you see God as a merit-weighing, sin- auditing, wage-master. God doesn’t mete out the punishment you deserve. If you think that then you’ve lost the plot. God responds to the crosses we build with empty tombs.

There’s nothing you can do to make the Father love you more and there’s nothing you have done to make the Father love you less.

Your sin doesn’t do anything to God, but it can distort everything about you. It can ruin your eyes even, to the point you don’t recognize your own Father anymore.

Don’t be fooled today into thinking that if you have contrition, if you confess your sins, if you bear your ashes with the proper penitence then God will come and forgive you, that God will be moved by your heartfelt apology, that God will change his mind about you and forgive you. Not at all. God never changes his mind about you. Because God doesn’t change. No, what God does do— over and again, as long as it takes— God changes your mind about him.If you’re sorry for your sin, that’s why.

If you’re contrite over your sin, that’s why. If you want to be forgiven of your sin, that’s why.It’s the unchanging God, at work, in you, repenting you.

You are not forgiven because you confess your sin. You confess your sin, see yourself for what you are, because you are already forgiven. Forgiveness is not the product of something we do to change God. Forgiveness is the product in us of what God does to change us. God’s forgiveness always precedes our confession and contrition. That’s why when you come forward for a smear of ashes, you are not coming forward in order to have your sins forgiven. You’re coming forward to celebrate that your sins are forgiven.

Which means—

These ashes on Ash Wednesday are not a sign that we are the people who have changed how God views us.The ashes are the sign that we are the people whose vision God has changed.

Sure, these ashes are black and gritty and oily but you should bear them as though you are wearing the finest robe and gaudiest ring, as though someone has kicked on the turntable and set out the flatware and linens, killed the fattest calf, and invited you to get drunk out of your mind because you once were blind but finally you see.

See that the God you thought was an angry judge. An auditor. An accuser.

He’s just a Dad on a porch.

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 28, 2022

The Virtue of War

After blogging for tens years I’ve moved to this space. So, I’m starting from scratch (again). Do me a solid and subscribe!

The theologian Stanley Hauerwas often refers to the poster he hung on his door at Duke Divinity School for many years. From the Mennonite Central Committee, the poster showed an anguished embrace in a war zone and read, “A Modest Proposal for Peace: Let the Christians of the World Agree That They Will Not Kill Each Other.” It’s hard to argue with the conviction that fellow followers of the Prince of Peace should practice reconciliation with one another and ought refrain from taking up arms against each other. The way of Jesus is not the way of Mars; the empty tomb testifies conclusively that the grain of the universe runs with those who bear crosses and not with those who build them. Nevertheless, it’s also equally difficult to construe Russia’s unprovoked invasion into Ukraine as anything other than a Christian war in that the aggressors and their victims are all largely baptized believers.

What then is the witness Christians owe their Lord when fellow Christians have determined to wreak havoc against them?

In critiquing the Cold War realism of Reinhold Niebuhr, Stanley Hauerwas notes that his objection to the just war tradition is not to the conditions of the Church’s just theory per se but that too often Christians in America have used them to justify any military action undertaken by America thereby revealing that the true loyalty of Christians in America is not to Christ but to America. If you find that to be a hyperbolic statement I dare you to move the flag from your church’s sanctuary. Try it this Sunday and see how church people react. No war fought by America, Hauerwas argues— and it is an arguable assertion— has been a just war under the parameters of the just war tradition.

Perhaps because it’s been too easy for Christians in America to critique America (on pacifist grounds) or unthinkingly to baptize every American call to arms (see: Evangelicals), it’s halting to witness in real time Christians waging a just war in the face of an altogether unrighteous invasion of their home.

Just may be the wrong word for what we’re seeing play out in Ukraine, for what Christian just war theory and Christian nonviolence share in common is the presumption that war is always in every case and situation a moral evil, and I don’t know evil is a coherent way to characterize Ukrainian civilians boldly defending their homes and their democracy.

Only the most monstrous sort of Pharisee could look at the photographs of elderly women climbing out from the rubble of their Russian bombed homes, or the just-graduated-from-college teachers holding rifles against oncoming tanks, and judge that the resistance in Ukraine is somehow in league with rather than against evil or conclude that the God who once heard the cries of his people now demands they acquiesce as mobile crematoriums drive into their cities.

The war in Ukraine— again, a war waged by Christians against Christians— is disorienting for it reveals the extent to which war is a neutral instrument capable of being used towards moral or immoral ends. War may be— has been shown to be this past week by Ukrainian Christians— an act of caritas. As my former teacher, David Bentley Hart writes, commenting on the book, The Virtue of War:

“American Christian ethics treat the Christian pacifism of the sort one associates with, say, John Howard Yoder, and the “Christian realism” of Reinhold Niebuhr and his disciples as the only available options for Christian moralists.

And yet pacifism and realism are mere inversions of one another, inasmuch as they share more or less the same view of what warfare is. Both accept the premise that war is by its nature evil, while only peace is an unqualified good. The pacifist may believe that peace (understood simply as the absence of strife) is best achieved by refusing to participate in war, and the realist that peace (understood as a secure and just social order) is best achieved by answering violence with violence, but both then accept that the Christian never has any choice in times of war but to collaborate with evil: He must either allow the violence of an aggressor to prevail or employ inherently wicked methods to assure that it does not.

The bracingly unsentimental argument is that war in fact is not intrinsically evil, however tragic it may be…when it is waged on behalf of justice and by just means, it is a positive good, a work of virtue, and an act of charity.

Simply said, for Christians, to go to war should never be a tragic choice of the lesser of two evils, for we are forbidden as Christians to do evil at all.

Rather, if we go to war, it is out of a militant commitment to the peace of God’s Kingdom, and when we fight, we fight as agents of divine justice in the earth. And that may frequently be cause for sorrow, but should never be cause for contrition.

In Augustine and Thomas one finds a cogent account—though one, no doubt, somewhat scandalous to modern ears—of justifiable violence as a work of charity. For Augustine, certainly, love occasionally demands violence, such that the failure to use violence is also a failure of love (which is a sin). For Thomas, it is precisely because all human loves must be ordered within the love of God—who is infinite goodness—and governed by the virtue of charity that war may become inevitable for a Christian people: For an unjust peace is not pleasing to God, and the love of any earthly order must conform itself first to the love of divine justice.

It is one thing to turn the other cheek against insult and casual abuse, or even to accept martyrdom, but another thing altogether to permit oneself simply to be murdered to no good end. To love charitably—selflessly—requires that love of self be ordered towards the love of God; to do this, one must learn to love oneself under the rule of justice, and to fail to do so is no less a sin than refusing to defend one’s neighbor. Indeed, defending oneself against unjust violence is one of the few times that one can most assuredly subsume self-love under the law of charity, without egoism or spite intruding at all.

If we go forth to fight for God’s justice, we do so as citizens of a Kingdom not of this world, one that can make use of the post-Christian state, but that cannot share its purposes. To the world, this may appear to mean that we go forth only as individuals, driven each merely by the passion of his faith. Perhaps so. And perhaps it is then also the case that, really, we must learn again how to speak not only of just war, but of chivalry.”

- excerpted from In the Aftermath: Provocations and Laments

February 27, 2022

The Sacrifice of War

After blogging for ten years, I’ve moved to this space. So, I’m starting all over. From scratch. Again. Do me a solid and subscribe!

My Grandpa went to Drexel in Philadelphia for college, an opportunity made possible by the GI Bill. My Grandpa was part of what Tom Brokaw called the greatest generation, a description that embarrassed him. My Grandpa fought in the Pacific in World War II. He only spoke about it to me once, in fact. So rare was it that the memory has always stuck with me. I was in Middle School and, after my Grandma moved into a nursing home, my Grandpa moved out of their big, brick Georgian and into a condo. The moves rearranged all the familiar furniture and knick-knacks. Thus, hanging on the wall in the new condo was something I’d never seen before. A medal.

“How’d you get that?” I asked him, pointing to the medal.

He waved it off, not saying anything. I just stood there, waiting for more of an explanation behind the medal. But none was coming. So I asked him, what it was like, being in the war. And I remember, he looked at me like you do when you want to warn a little kid away from touching a hot stove and he said, “What was it like? Scary as hell.” “Scary because you thought you might die?” stupid, Middle School-aged me asked. “No,” he said, “scary because I thought I might have to kill.”

In his study of men in battle in the Second World War, General SLA Marshall observed that out of every hundred men along a line of fire, during battle, less than a fifth of them would take part by actually firing their weapons at another human being. The majority would do everything they could (short of betray their comrades) to refrain from killing. This led General Marshall to conclude:

“The average, healthy individual has such an inner and usually unrealized resistance to killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is at all possible to turn away from that responsibility.“

General Marshall’s observation is not, I think, a psychological insight— at least, it’s not only a psychological insight. It is, I believe, a theological one. I believe it’s a theological insight that we hear confirmed in the creed and the scriptures that inform them.

Many assume that the ultimate sacrifice we ask of soldiers is the sacrifice of their lives, and, obviously, that is a great and grave matter. But I think the argument of scripture and General Marshall’s study invites us to see it differently. The Book of Genesis tells us that each of us are made in the image of God. Then Colossians expands on that claim by asserting what the prologue of John’s Gospel announces; namely, Jesus is the image of the invisible God. Therefore, we are made in Jesus’s image. Christ, the Second Adam who nonetheless breathed the breath of life into the first Adam, is the blueprint according to whom we’ve been created. And Jesus would rather die than kill. And so would we.

If creed and canon are correct, if we’re made in the image of the Prince of Peace, then the ultimate sacrifice offered by those who take up arms is not the giving of their lives, it’s forsaking their innate, God-given Christ-like unwillingness to kill.

To do so is wound as deep as the incarnation, for, apart from the restoration made possible by the absolution of Christ, what’s lost in the taking of another’s life is the fullness of humanity.

Understood theologically, the one who takes life is the one who loses their humanity.

Like you, over the past few days I’ve looked at the heartrending photos on Twitter and in the news of young school teachers in Ukraine holding weapons in their arms as awkwardly as a teenager with a learner’s permit. The costs of Putin’s unprovoked invasion are clear: the flare of rockets against a night sky; the domes of church altars reduced to rubble. Soon casualties will be counted up in numbers of a hundred, or a thousand, or more, but each life lost will be mourned as a single digit of infinite value by those who loved them.

But if the Gospel is true, there’s a greater cost to those victims of the war and a still greater crime committed against them than simply an unhinged, unwarranted invasion.

By forcing Ukrainians, civilians— school teachers and pastors and young mothers— to take up arms, the would be usurpers force them to make a sacrifice more significant even of their lives. They’re robbing them of their share of the imago dei.

Putin is wreaking not simply a wound to their homeland but to their souls.

To which the only sacred response is, “God, damn him.”

But to curse is not to make sense.

The only way Christians make sense of Sin and Death is by pointing to the promise of Resurrection; specifically, the promise that the Risen One will return to this cruel world and make all things new. If there’s one certainty at this point in the conflict it’s that this week we’ve received concrete photographic examples of what we mean when we profess, “He will come again to rectify the quick and the dead.”

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

February 25, 2022

If the Law (“Thou shalt not kill”) is not absolute, the Gospel’s absolution is not perfect

After ten years of blogging, I’m moving to this space. So I’m starting from scratch (again). Do a fella a solid and subscribe.

Look, I’m a smart guy, but I’m no expert in geo-politics so I won’t pretend to be one today; however, I do know theology and scripture as it relates to questions of war and witness.

So here goes:

My friend and mentor, theologian Stanley Hauerwas, posits often that Christians oppose war not because Christians believe non-violence is an effective strategy to rid the world of war but rather because Christians believe that through the cross of Jesus Christ war has been abolished.

The crucifixion is the sacrifice to end all sacrifices, says scripture; therefore, in a world of war, Christians believe they are the people whom God has put into the world to bear witness to the Son’s abolition of all violence.

The cry of Mary’s son against God’s silence, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?!” is also at once God’s thunderous “Nein!” to all our attempts to make history come out right in the end.

God does not intend the community of the cross to make the world a better place. The (non-violent) community of the cross is the better place God has created in the world.

While I agree wholeheartedly with Stanley’s position, the rhetoric with which he argues is too often in the register of the Law; that is, Hauerwas insists that in light of the cross this is how Christians ought to live. Not only, I suspect, does such speech burden Christians with guilt and shame over how far they fall short given the vicissitudes of the places and professions in which Christians find themselves, it ironically fails (by ostensibly establishing a new one) to do justice to the Law. In other words, what we need is a grace-centered understanding of war.

A full-throated understanding of grace lands Christians in essentially the same place as Hauerwas but does so, I think, by taking the Law with more and utmost seriousness. Ever since Augustine— and especially Aquinas— the default position of Christians, living with the burdens of Christendom, has been just war theory; that is, Christians can endorse limited wars provided they’re prosecuted under specific conditions. Wars must be defensive rather than offensive, innocent lives must not be attacked, damage should be debilitating but not total. Given the reality of original sin and the fact that it’s evenly distributed across all human hearts, it’s dubious that any war deemed a just war by the Church has ever abided by just war conditions. Lincoln, for example, understood explicitly that by endorsing Grant’s total war strategy he was relinquishing any connection to the Church’s tradition of just war.

The problem with the just war tradition, however, is that by endorsing the idea that war is acceptable in some situations— what philosophers call casuistry— it concedes that the Law (“Thou shalt not kill”) is not universal, absolute in every instance. But if the Law is not unflinching in its demand, at all times and in all places, if sometimes the Law does not accuse us, then Christ’s sacrifice in our stead for our failures to live according to the Law is not, in some cases necessary.

In other words, if killing is just in this case, then this is an instance where you do not need a vicarious, atoning savior.

Christ did not need to die for you for this sin under the Law nor did he need to fulfill the Law for you with his life of perfect faithfulness.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Exceptions to the Law, which scripture insists is good, holy, and righteous, undo the atonement by softening the demands of the Law.

As Paul Zahl writes, the Law “cannot be muted to suit conflicting goods.” Sinners will always only apply the Law on a case-by case basis that amounts to little more than another form of self-justification.

In some ways, the gospel of grace requires we reason backwards to the Law. Because the gospel bears the glad tidings that the cross of Christ for sinners is full, final, perfect, and once for all— a past work that redounds through the present and into the future— then the command, “Thou shalt not kill,” must be absolute and unyielding in every instance.

If grace is true, then the Christian response to war is not to mute the Law’s accusation in this particular situation. It’s to turn to our Savior and confess, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

February 23, 2022

No One’s Better at Doubt and Despair than Pastors

After ten years of blogging, I’ve moved here. So I’m starting from scratch. Again. Do me a solid and subscribe.

Save Marilynne Robinson’s Rev. Ames in Gilead or the Rev. Mclean in A River Runs Through It, the clergymen of literature skew heavy towards the phony, contemptible, and intellectually incurious. Indeed they’re a not insignificant reason that the words preach and sermon have become synonymous with a finger-wagging, hypocritical harangue. For every Elder Zosima there’s at least ten Elmer Gantry’s. The vicars of Jane Austen’s Victorian novels typically evidence little boldness and even more paltry theological wit. And what’s most often lacking among the modern day ministers in the work of John Updike or Flannery O’Connor is belief itself. Faith is their fiction.

It’s easy to assume, I suppose, that faith and doubt are part of a pastor’s professional portfolio, doctrines which we’re schooled to parse impersonally.

Doubt is something the duly ordained and pensioned pastor knows only from hindsight or from a detached third party distance, many imagine, while faith is the tool of our trade, as unexamined a part of our professional life as a mechanic’s wrench or a doctor’s stethoscope.

Like all assumptions, this one was pulled straight out of someone’s @#$.

Whenever I run up against this conjecture, I think immediately of the day, not too long ago, when my congregation was slammed with the news of three deaths in the space of twenty-four hours. The size of the congregation and its place in the community meant the total number of funerals we performed that year totaled roughly half the average attendance on a Sunday morning. This did not even include the burials and graveside services we provided for folks from the larger community.

Every week that year one of the pastors on staff was accompanying the dead with stubborn alleluias.

The day I always recall whenever an unbeliever posits that a pastor’s belief is easy and unexamined— one of the three deaths that day was sudden and unexpected. One was not. The third one was but wasn’t (you know the kind) but sadder still for the loose ends which remained and stood a good chance of overwhelming the survivors.

In a lot of ways ministry is a dismal trade.

The prologue to the Gospel of John announces the advent of the incarnation with the news that the darkness does not overcome the light.

The devil is in the details; notice, John doesn’t say the darkness disappears.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

For both proximity and frequency, I tend to think clergy have more occasions than most to wrestle with faith and doubt. Not less. What is a singularly painful but mercifully infrequent moment in most families lives is, for us, part of punching the clock. If we had one.

Only the most unreflective, unfeeling fool would be able to strap on a collar or stole and stare into the void over and over and not wonder if there’s really anything there on the other side.

And only such a fool would not weep on the inside for the gift of faith that comes back from the other side even if nothing more definitive than that ever does.

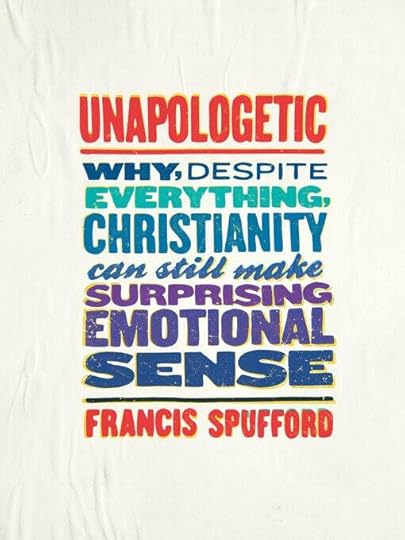

In Unapologetic, Francis Spufford writes:

“Lots of atheists seem to be certain, recently that this (doubt in the face of suffering) ought not to be a problem for believers, because— curl of lip— we all believe we’re going to be whisked away to a magic kingdom in the sky instead. Facing the prospect of annihilation squarely is the exclusive achievement of-preen- the unbeliever.

But I don’t know many actual Christians who feel this way, or anything like it. Death’s reality is a given of human experience, for anyone old enough to have shaken off adolescent delusions of immortality. There it is, the black water, not to be cancelled by declarations, by storytelling of any kind.

Whatever sense belief makes of death, it has to incorporate its self-evident reality, not deny it.

And again, in my experience, belief makes the problem harder, not easier.

Because there death is, real for us as it is for everyone else, and yet (as with every outrage of the cruel world) we also have to fit it with the intermittently felt, constantly transmitted assurance that we are loved.

I don’t mean to suggest all believers are in a state of continual anguish about this, but it is a very rare believer who has not had to come to a reckoning with the contradiction involved.”

On the one hand, the cruel world— the world made cruel by seeing it as created— and on the other hand, the sensation of being cherished by its Creator.

When it comes the holy yet dismal trade that is at least one-third of ministry, I say:

What he said.

While literature portrays pastors as grifters and buffoons, popular piety too often over-corrects and caroms off reality, treating pastors as heroes of faith and experts at spiritual intuition. I think if there’s anything heroic about ministry, it’s that we keep stepping close to the cruel void that most only face a few times in their lives. If there’s anything remarkable about pastors, it’s that they so step and, most of the time, come away yet having been gifted some small measure of faith.

February 22, 2022

The Obligation to Worship

After ten years of blogging, I’ve moved to this space. Do me a solid and subscribe (especially you, mom)

A few years ago a parishioner stormed out of the sanctuary at the end of the early service, shook his head ruefully like he’d just discovered he was wearing a poopy shoe, and announced to me, “I did NOT care for that last song.”

Bless your heart, I thought. I then flexed my pastoral muscles and replied— in love:

“Isn’t that interesting? You’ve somehow been led to believe that song was for you.”

Tish Harrison Warren, a priest in the Anglican Church of North America, published an op-ed in the New York Times a couple of weeks ago in which she advocated a cessation of online worship services. Judging from the reaction her article provoked on Christian Twitter you would think Warren had murdered kittens or insisted that Ted Lasso is a bad television show. What the pandemic made a necessity, she writes, has now become too easy a way for people to avoid getting up at an inconvenient hour, dressing in uncomfortable clothes, and tolerating chitchat with people whose opinions irritate the hell out of you.

Illness and death were not the only detriments covid-19 brought to us in 2020. In the Church, one of those losses was embodied, incarnate worship with other believers, to say nothing of the friendship, encouragement, and hope such a community provides. The Church commits a grave error, Warren suggests, when it acts as though worship is an activity so easily disembodied and relocated to the ether of the internet. Incidentally, I think she’s correct when she suggests many Christians are reluctant to gather again in-person because of those other Christians who never stopped gathering in-person, even at the height of the pandemic. Online versus in-person is but another way of distinguishing Red and Blue. While I think a blanket termination of live streaming is an excessive measure and while I know firsthand that online worship can offer the gospel for people who hear only law in their own congregations, Warren’s larger argument is not without merit.

If nothing else, Warren’s op-ed raises an important, implicit question, “Who is worship for?”

Now that the urgency of a pandemic recedes, online versus in-person worship have evolved into categories of personal preference— we tend to speak of the two options the way we once (or still) talk about genres of music, styles of service, and dress code. I enjoy being able to worship in my pajamas is the equivalent to I only want to sing traditional hymns. Whether we’re arguing about the ability of the Spirit to make us a mystical body over Zoom or how the pipe organ is the only instrumentation endorsed by the Holy One, we’re speaking in terms of personal preference.

But worship is not for us.

What we get out of worship is not a good in which God seems very interested.

We’ve wandered far from scripture indeed if we’ve forgotten that worship is an act we give to God. As we pray at the table, our worship is a sacrifice. Instead of goats and grains, we offer God our praise and thanksgiving. We do so not because the latest Hillsong will give us a spiritual high to help us through the week. We do so because God wants us to do it. This is what the Roman Catholic Church, in particular, gets very right. We do have an obligation to worship the Lord.

We worship God because God wants to be worshipped. It’s not even hyperbolic to suggest this is the primary theme of the Bible.

God wants to be glorified. In fact, on special occasions the worship God desires is prodigally ridiculous, requesting in 2 Chronicles the sacrifice of 22,000 oxen and 120,000 sheep.

It’s become almost a cliche to identify God as the one who liberates his people who were captive in Egypt. Seldom do we stop to chew on the nasty truth that God wastes little time in sending those same people into exile under the boot of a different pharaoh for failing to worship him. “Yet you did not call upon me, O Jacob,” the word of the Lord says to Isaiah, “but you have been weary of me, O Israel! You have not brought me your sheep for burnt offerings, or honored me with sacrifices.” We make a mistake when we dismiss the sacrifices in the Old Testament as antiquated. The sacrificial system of the Old Testament prefigured the cross of Christ, who said, “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

Whether we’re talking about the fruit offering of Cain or the self-offering of Jesus, in the Bible the purpose of worship is the same. As the Lord says to Isaiah in the next verse, “I, I am he, who blots out your transgressions for my own sake, and I will not remember your sins.”

God wants us to worship him because God wants us to know him as the gracious God who has almighty amnesia when it comes to our sins and transgressions.

God desires our worship because God wants us to have that experience of knowing that we’re known completely by the One from whom no secret is hidden and, in spite of all that is to be found in us, loved. Every Sunday is a journey home from a far country, where we’ve incurred enough mistakes and regrets to skew our perception of our Father as a taskmaster. “Perhaps my father will hire me on as one his servants…” the son says only to be surprised by the old man running down the driveway with wet eyes and open arms.

Worship is a weekly recapitulation of the parable of the prodigal father.

It’s fatted calf killing kind of celebration.

Can the Holy Spirit connect you to a body of believers through the click of a mouse? Sure, but what kind of party is that?

You also have the obligation to subscribe.

February 21, 2022

The Descent into Moralism

Hey! After a decade of blogging, I’m moving to this space. Do me a solid and subscribe!

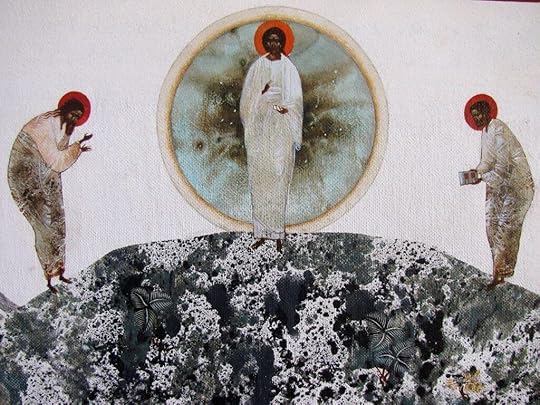

The pivot between epiphany and lent is always turns on the transfiguration where the disciples behold Jesus, alongside Moses and Elijah, aflame with the glory of God but, like the burning bush, not consumed by it.

If you’ve endured more than a handful of sermons, then chances are you already know how the preaching from this point on the mountaintop is supposed to go. Preachers point the finger at Peter and chalk this episode up as yet another example of Peter getting Jesus all wrong. It’s not about the mountaintop experience; it’s about rolling up our sleeves and serving serve the least, the lost, and the left behind.

The way down the mountain is almost always a descent into moralism.

About how faith is about going back down into the valley of life to do the things upper middle class Christians aren’t embarrassed to affirm in front of their pagan co-workers.

Go back down the mountaintop, back into “real life,” and do like Christ.

Except—

If Peter is wrong, if this is nothing more than another example of how obtuse Peter is, then when Peter professes “Master, it is good for us to be here. Let us make three tabernacles, one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah” why doesn’t Jesus correct him?

Why doesn’t Jesus rebuff Peter and say: ‘No, it is good for us to go back down the mountain to serve the least, the lost, and the lonely?’If Peter’s suggestion that they rest there is such a grave temptation, then why doesn’t Jesus exhort him like he does just before this scene and say: ‘Get behind me, Satan?’

This is the only instance in any of the Gospels where Jesus doesn’t respond at all to something that someone has said to him.

What would Peter make of the fact that so many preachers make Peter the subject of the sermon? Peter would know that he should not be the subject of our sermons. Peter would know that the takeaway from the Transfiguration is not what we must go down and do for God. The takeaway from the transfiguration is what God is about to go down and do for us. For ALL of us. Once for ALL. The Transfiguration— it is a preview of the Gospel.

Luke spells it out for you.

Just before this scene, Jesus tells the disciples that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, be rejected by the super-pious holiness enforcers, and get crucified by an angry crowd taking the only democratic vote in scripture (“We want Barabbas!”)

Next scene, today’s scene:

Moses and Elijah, the giver of the Law and the prophet of the Law, are there on this mountaintop “speaking with Jesus about his departure which he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem.”

Accomplish.

Luke doesn’t say Jesus was about to experience something unfortunate or unintended in Jerusalem. He says accomplish.

It’s vogue among preachers today to downplay the crucifixion, but when you read the Gospels straight through you discover that not only does Jesus talk about his death all the time, he speaks of it as a necessity. He speaks of it as a mission he will accomplish. Luke says here that Jesus speaks of his crucifixion as a departure that he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem. And the Greek word Luke uses for departure? Any guesses? Exodus. They’re talking about the exodus he will accomplish in Jerusalem. From the Pharaoh of Sin and Death.

In the David story, the glory of God is what spilled forth from the ark of the Law and struck an innocent bystanding boy named Uzzah dead. At the transfiguration, Elijah and Moses appeared to them on the mountaintop in glory, Luke tells us. The glory of God transfigured Christ, Luke tells us. And Peter and James and John beheld the glory, Luke tells us.

Notice what Luke doesn’t tell us— they lived.

They’re like Harry Potter. They’re the boys who lived.

Peter and James and John— sinners all, Peter maybe most of all— beheld the unmediated glory of God in the flesh and they did not receive the wage their sins had earned them. They were not struck dead. That’s why they walk away dead silent. They were dumbfounded by this preview of the grace of God where another’s death will do for undeserving sinners.

As much as we argue in the Church about what lifestyles are compatible with Christian teaching, it’s straightforward Christian teaching that we’re all incompatible with Christian teaching.

We have all sinned and fallen short. But Christ is the end of the Law. God judges not a one of us according to us. God judges every one of us on account of Christ’s cross and according to his righteousness. Such that, now, by grace alone— not by what you do or who you are— by grace alone— now, like those three disciples on the mountaintop today, you and I (though sinners we are and sinners we always will remain) We can sleep easy before the glory of God.

That the disciples live to go back down the mountain is a preview of the glad tidings that we are are justified not by our behavior, not by our belief, not by our good-deed-doing but by grace alone.

That’s the Gospel.

Everything else— every single other thing we can say—is the Law not the Gospel.

For freedom from the Law, Christ has set us free, scripture says. That’s the other takeaway from the transfiguration. Jesus appears there with Moses and Elijah, the giver of the Law and the prophet of the Law, because the Law— with all of its demands for holiness, all of its expectations of a lifestyle compatibile with its commands— the Law ends in Jesus Christ. Full stop. Moses and Elijah appear there in glory but their glory fades.

The true glory of God is the Christ who delivers grace.

Christianity is either all grace (what God has done for you) or it’s all works (what you must do for God). Grace and Works are mutually exclusive possibilities. This is the insight of the Protestant Reformation. If it’s not all of the former, it is all of the latter no matter the lip service you might pay to grace. Any attempt to balance or blend grace with works destroys the very notion of grace. It muddles the Gospel with the Law. It creates a kind of Glawspel, which is exactly the sort of toxic religion that’s killing the Church. Everything that is not the Gospel of grace is the Law.

As soon as you make Christianity about the Law, you become a debtor to every single one of its demands.

And thus far, only one guy has been able to clear that bar.

Whenever you make Christianity about the Law, about living a life compatible with the commandments, you become a debter to every single one of its demands.

This is why this is the only place in all of scripture that Jesus doesn’t reply.

Peter is right.

It is good for us to be here.

It is good for us to see that the Law, according to which not one of us measures up, ends in the glory of his grace; so that, the Law is fulfilled in us not through our pious deeds or holy living but through faith alone.

Faith alone in the Gospel of grace is what reckons to you the credit of a lifestyle compatible with Christian teaching.

That’s not just good news.

That’s the good news.

Because the Church is the only place in the world— at least, it should be— where we can lay down all our burdens of what we ought to do but don’t and what we oughtn’t do but did— the Church is the only place where we can lay those burdens down and rest in his grace.

Peter is right.

Until we learn to lay down the Law and go cold turkey from commandment-keeping and holiness-enforcing, until we learn to rest in Grace, every journey back down the mountain will be a descent that leaves the Gospel behind.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers