Jason Micheli's Blog, page 90

March 30, 2022

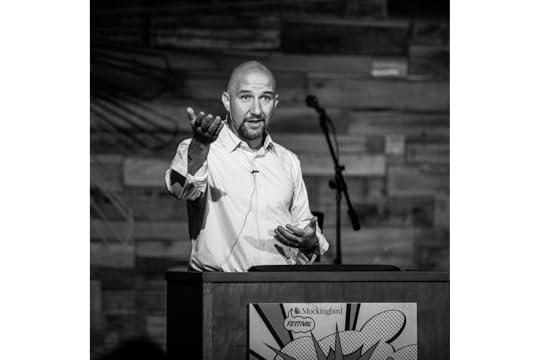

He Came Preaching the Pardon of God

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

We’re in the twilight of Lent, a time every year when Christians— preachers especially— wrestle in earnest with the question at the heart of the Church’s faith, “Why was Jesus Christ crucified?”

The Apostle Paul says we all have the Law tattooed on our hearts. We just can’t help ourselves. We’re hard-wired to think in terms of merit and demerit, earning and deserving, cause and effect. It’s not surprising, therefore, that just as we’re hard-wired to want a preacher to exhort us in Jesus’s name, we also want a preacher to explain to us the reason for his death. The language of the Law is not imprecise. Any account, on God’s side of the ledger, that necessitates the crucifixion— God’s honor, for example— makes the Law almighty over the God who has told us he is slow to anger, rich in mercy, and abounding in steadfast love. Even if you’ve never been to seminary, you know what the Church has termed (with an appropriate amount of hedging) “atonement theories.”

Jesus paid it all, the hymn sings. In Christ alone, “the wrath of God was satisfied” a contemporary song summaries the old, old story. At least the roadside signs and Christian kitsch are more honest about the transactional nature of these theories, reducing the Gospel story to a math equation, “1 cross + 3 nails = 4given.” Stanley Hauerwas often quips about Easter, “If you had an explanation for the resurrection, you should worship that explanation not Jesus Christ.” Likewise, if there’s an eternal law which requires Jesus to solve the roadside equation, then we should worship that all-determinative law rather than Jesus or the other members of the Trinity. Luther called such explanations of the crucifixion “covering the cross with roses,” for they hide the brute and immediate fact that Jesus dies on the cross because we killed him.

Perhaps more critically, “theories” of atonement that make the cross a legal necessity on the way to divine pardon ignore the clear testimony of the evangelists in the Gospels.

Jesus doesn’t die so that God can forgive us.Jesus comes proclaiming the forgiveness of God.Christ preaches the pardon of God from the very start of the Gospel— hell, this is why we killed him!

In a justly famous sermon, “Jesus Died for You,” the theologian Gerhard Forde quickly summarizes the various atonement motifs at work in the history of the Church. He considers especially the most prominent theme in Christian interpretation, Substitution. Hewing close to his text, Forde says:

“All we need to do is to look carefully at what actually happened…“God didn’t have to be paid to forgive, but announced forgiveness through Jesus to begin with. But that is when the trouble starts. For we would not have it… we don’t need elaborate theories or doctrines of the atonement to see why his death is for us. We lay hands on him and put him to death. And he does not stop us.”

In other words, Jesus dies for us not in the sense of a divinely necessary transaction that somehow actualizes an eternal, unchanging attribute of God. Jesus dies for us in two important and indicting ways. Jesus dies because of us— by our hands. Jesus dies for us; that is, Jesus allows us to kill him for that is the only way in which we will receive him. Forde’s sermon echoes the very first Christian sermon, Peter’s preaching on Pentecost. This God whom we killed, Peter preaches, God gave him back to us, raising him from the grave. The preaching of Peter, who could probably still smell the charcoal fire around which he thrice denied Jesus, will not allow us to lay the blame for Jesus’ death elsewhere than our own hands.

Christ’s death and resurrection triumph over Sin, Death, and the Devil, then, because those are the Powers which conscripted us in to the original of all sins, the rejection of the pardoning God.

The explanation for the death of the incarnate God by the most ungodly of means is simple. The explanation is not eternal but it is every bit as mysterious. The reason for the death of Jesus is that, in him, God came preaching the unconditional forgiveness of sins for sinners who do not deserve it, and we killed him for it. He bears our sins in his body— actually. “The liberals in the Church are right,” Forde writes, “God is love; God is merciful. They just do not see that this is why we must kill him.” Forgiveness, full and free, with no strings attached is just as dangerous and criminal as robbery or murder or sedition. It cannot be allowed. It shatters all order, offends all morality, and smashes every system of justice.

In his work, Atonement as Actual Event, Forde offers a grisly analogy to clarify the meaning of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. Imagine, Forde writes:

The answer to the question “Why was Jesus crucified?” is Jesus. He is his own explanation.

“A child is playing in the street. A truck is bearing down on the child— maybe the driver is simply a bad driver, maybe the driver is a reckless driver, maybe the driver is drunk. Suddenly a man throws himself in the path of the truck, saves the child, but is himself killed in the process…

It would be all too easy to identify ourselves with the more or less innocent child playing in the street and to look on the sacrifice as a sacrifice that averts our death. To make the analogy work properly, however, we must say that we are not the child playing in the street. We are the driver of the truck. If anything, the child playing in the street is our neighbor— maybe a neighbor so close they live in the same house as us or share the same bed with us. The child in the story is not us. We are the driver of the truck.

Suddenly, there is the someone who throws himself in our unheeding way and is crushed against the front of our machine…

Jesus is the one splattered against the grill of your truck who comes back to you to say, “Shalom!””

He is the one in whom God did God to us. He did God’s mercy and forgiveness to us. He bore relentless witness to it; therefore, he had to die. And not just die, we thought, his reckless message had to be hammered into oblivion.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 29, 2022

We are the Nard God’s Purchased at Great Cost

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

This coming Sunday’s lectionary Gospel is Luke’s version of Mary anointing Jesus at Bethany. Here’s a reaction Bishop Will Willimon wrote to my sermon on the text for the Journal for Preachers.

Virtue Signal

John 12.1-8

Thousands of us preachers receive encouragement from Jason Micheli’s podcast, Crackers and Grape Juice. Here’s my commentary on one of Jason’s Christ the King sermons. Take this as two preachers thinking together about the challenges of doing politics in the pulpit with Jesus.

Will Willimon

For God’s sake, don’t lie.

Admit it. You think Judas is right.

You know that you’re not supposed to identify with Judas the traitor, the villain. Judas is the Judas, the bastard who turns around right after today’s text to rat out Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, which according to the prophet Zechariah was about a day’s wage. A day’s wage.

But be honest. If you saw a line item in our church operating budget for nard you’d be PO’d too. Nard was a perfume from the Himalayas. 300 denarii is what Judas guesses it would go for on the open market. 300 denarii was the rough equivalent to $45,000.00.

You think Judas is right on the money about the money. Considering the cost of nard, it would be better to rub Jesus down with some $5.99 Old Spice and give the remaining $44,990.00 for do-gooding.

And doing good is what it’s about, right?

Way to go, Jason. Lure them into the sermon by claiming their secret sympathy with Judas. Treat ‘em rough.

After all, Matthew’s account of this anointing occurs right after Jesus lays down every liberal Methodist’s favorite parable— clothing the naked, giving drink to the thirsty, feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, and visiting the prisoner. So who blames Judas for wanting to be reckoned a sheep rather than goat?

Matthew 25, favorite text (they think) of all Methodist do-gooders. Nice juxtaposition between Matthew and John. Move them from a text they think they know to consideration of a text they probably don’t know, allowing scripture to interpret scripture.

If we’re honest, it’s hard for us to see what Judas got wrong. Christians ought to be on the side of the poor. The world sees our inability to live up to Christ’s teachings about the poor and judges us accordingly. Isn’t Judas’ the better strategy for the Church to survive in a pagan nation like America? After all, Americans may not believe that Jesus is Lord but they at least believe we ought to help the poor. Serving the poor is a way for us as Christians to win friends and influence people.

Interesting link with the American church’s insecurity about our status in the culture. Why does the mainline church “helps the poor”? Because it’s the last socially acceptable thing the church has left to do.

In first century Israel, “poor” was a political category. The poor weren’t lazy or left behind. The poor were the oppressed. Read your Old Testament. The poor were poor because they were oppressed. If you don’t understand the relationship between poverty and oppression you won’t understand Palm Sunday when the “Messiah” turns out to be Jesus.

Judas isn’t simply suggesting that this down payment’s worth of perfume should’ve been shared with the poor; he’s arguing that it’d be better spent on the cause. The money should have been used to free the poor, liberate the oppressed. Judas’s point is not just about charity. It’s about justice. After all, he’s named for Israel’s most famous armed revolutionary.

“Why was this nard not sold for almost fifty grand and the money given to the Democratic National Committee?”

“Why was this perfume not sold and the money donated to Make Israel Great Again?” “What a waste! Don’t you people know your Micah 6.8?! The change we could work with that much cash!”

Politics! You make an adept connection – concisely, without a lot of academic throat-clearing – between our notions of “poor” and “politics,” “charity” and “justice.” You’re taking a risk in your association of Judas, and his particular brand of betrayal, with the DNC and MIGA. No risk = boring sermon. Now your sermon is beginning to move toward Christ the King with your reference to Palm Sunday. I bet the congregation, who knows you well, expects that you are on your way to a Micheli move: “Jesus Christ is Lord; Caesar is not.”

Which puts Judas (and thus, puts us) in the same camp as Caiphas.

In the text just before today’s, John tells us that a crowd of Jews, having witnessed Jesus speak Lazarus forth from the dead, began “believing into Jesus.”

Some of these bystanders tattled on Jesus to the Pharisees and the Pharisees went to the chief priests and the chief priests went and tattled to the Chief Priest, Caiphas.

Caiphas, who in a few short chapters will be outing himself with the words, “We have no King but Caesar.”

“If we let him go on like this,” Caiphas worries, “everyone will believe into him, and the Romans will come and destroy our nation.”

Sit with that for a second—

When the chief religious leaders of God’s people hear about Jesus’ power over the Power of Death, their immediate worry is not religious. It’s political.

Like we do, Caiphus had been towing the God and Country line, but as soon as the Living God shows up our true colors come out. When Caiphas hears Christ can raise the dead, two things worry him: Currency. And country.

Jesus is hiding out here in Bethany because just after Jesus produces Lazarus alive from the tomb, Caiphas plots to kill Jesus. Why? Because Caiphas worries that Christ’s power over the Power of Death will upset the political arrangement of the powers-that-be.

This section of the sermon is requires fancy hermeneutical footwork. You’ve introduced another figure, Caiphas, reminding us of his infamous, “We have no king but Caesar.” It’s doubtful that your listeners know much about Caiphas. You are also adding to your sermon’s complexity with your assertion of a linkage between the “power of Death”and politics. The political significance of resurrection is a powerful point to make on Christ the King, but it’s a complicated theological thought. I very much like your reminder of Lazarus and the way that his resuscitation leads Jesus’s critics to murderous thoughts based on their deadly politics. Still, I wonder if you risk losing them at this point. You seem aware of these possible pitfalls with your words, “Sit with that for a second.” Nice signal: folks, we are about to take a dive into the deep end of the pool.

Don’t forget:

This is the same Caiphas who on Good Friday will condemn Jesus to a cross while pledging to Pontius Pilate what no Jew should ever say: “We have no King but Caesar.”

Messiah, King and Caesar all name the same word. Caiphas is saying, “We have no Messiah but the King you call Caesar.”

“Forty-five grand! We could’ve donated that money to MoveOn.org— think of the justice work we could do.” Judas says.

“Power over Death? Death makes our economy of scarcity possible and gives us authority over the people possible. Resurrection, will ruin the nation.” Says Caiphas.

You see— Judas and Caiphas’ failure is not faithlessness.

Their failure is a failure of political imagination.

Use a phrase like “a failure of the political imagination,” watch their eyes glaze over. You’ve got your work cut out for you keeping them on board. Yet I see that’s exactly what you intend to do in the rest of the sermon. By setting a (at first glance) offensive text next to the text you’re exploring, then by giving us some specific instances of the politics of resurrection at work, you are doing all you can to keep your listeners with you on this journey.

In order to see their failure as a failure of political imagination, however, we must first admit our embarrassment about what Jesus says to Judas: “You’ll always have the poor with you; you don’t always have me.”

Try that verse out on a woke, Bernie supporter. What Jesus says to Judas seems to legitimate the non-Christian critique of apathetic, pie-in-the-sky Christianity .

But please note: The one who said “You’ll always have the poor with you; you don’t always have me” is himself poor.

Jesus is poor. Jesus is oppressed.

And very soon, Jesus will be the naked, parched, the stranger shunned, the prisoner abandoned by all but his mother and a single disciple. Surrounded by goats, they’ll be the only sheep at his side for the Last Judgement that is his Cross.

This is why Caiphus plots to kill him.

We think Judas is right, but we miss how right Caiphas really is.

Jesus is a threat to our politics, the end of the world as we know it.

Mary upends our categories of helping the poor and the oppressed by her extravagance toward a poor person (who also happens to be the incarnate God). Jesus praises her for doing a good and joyful thing that shall always be remembered.

Judas has got his mind stuck in the grave— he still thinks that change-making comes in terms of charity and campaign contributions, but Mary’s response to Jesus’ power over the Power of Death is to shower two-thirds of our entire mission budget on a solitary poor man living on borrowed time. Judas lacks Mary’s imagination.

I love your interpretative imagination at work. “Poor” is not a sociological, economic category; poor is what God did to be among us as the Christ. We shall worship and serve God as the kenotic, impoverished Jesus or not at all.

Jesus does not imply that we should be resigned to the way of the world. On the contrary, we will always have the poor with us because the Church, the Body of Christ, is put in the world so that the world may know, by the sacrament of the resurrection, how the poor and the prisoner, the naked and the shunned, are to be celebrated.

The Church is the People of God in the world who know that we can afford to love the poor with lavishment because Christ is a gift that can never be used up. So of course we’ll always have the poor with us. Because the Church is the Body of him who is poor. We will always have the poor with us because the Body of Christ is for them.

“Leave her alone,” the poor man said to Judas, “she bought it [all $45K!] for me.”

Jesus praises Mary because Mary understands that Jesus makes a different politics possible. She-and-her-nard constitutes the different politics which God has made possible in the world in Jesus.

As Bonhoeffer said, “The church is the way the risen Christ has chosen to take up room in the world.” Thanks for the reminder of the lavishness of God in action in the Body of Christ.

Karl Barth wrote: “Whenever Christians use a construction like Christianity and politics they open the door to every devil.”

Barth pointed out that when the devil tempts Christ in the wilderness by offering him the governments of this world the implication is that the governments of this world are the devil’s to give. Barth was one of the few German Christians to stand up against Hitler’s Nazi regime.

As soon as the church begins to ponder how its Christianity can be helpful to politics, Barth argued, such a church might have great sincerity and zeal, and good works of charity, but it will be a church that’s failed to understand that the church is the peculiar way God has chosen to love and redeem the world.

Thanks for invoking Barth, though again, I’m unsure that your listeners will appreciate the revolutionary impact of Barth’s warning against conjunctions. You are making me evaluate my own preaching. Am I demanding too little work from my listeners? How I love the way you take your listeners seriously. You engage deadly serious matters in a playful, beguiling way, and you don’t waste our time with cliché and cant. Kudos for preaching a deeply “political” sermon without saying, “Since God is either dead or retired, let us go forth to defeat racism, sexism, ageism, classism. It’s up to us to do right or right won’t be done.”

God has chosen not the House or the Senate. Neither POTUS or SCOTUS not bills, billboards, or hashtags. But his People. The Church.

The Body of Christ, sent by the Spirit, is God’s virtue signal; that is to say, the Church doesn’t have a politics the Church is a politics.

What do I mean by “the church is a politics”?

Now the sermon touches down upon the Body of Christ otherwise known as Annandale UMC. Nice.

Yesterday afternoon we celebrated a Service of Death and Resurrection for a man in the community, Gordon.

Gordon was a Vietnam vet. The cancer that killed him likely came from Agent Orange that killed others. A couple of days before he died, he called me to his bedside. In addition to wanting to profess that Jesus is Lord and give to Christ what remained of his life, Gordon also wanted to confess his sins.

“I want to confess,” he told me staring at the ceiling, “what I had to do in the war— it was necessary, but it was still sin.”

Think about it—

He was dying. Time was a precious, valuable commodity to him. Time was a gift, and Gordon wanted to give it, to lavish it— some would say waste it— by giving his confession to Christ.

In a culture that ships our soldiers off to do what is necessary and then, when they return home, we insist that they not tell us about what we’ve asked them to do, Gordon’s confession— what the Church calls the care of souls— that’s a politics.

“Say something political on Christ the King, church.” Church says, “Church.” You and I will never be able to get Stanley Hauerwas out of our sermons, thank God.

It’s how God has chosen to care for the world.

During the funeral service, Gordon’s son spoke candidly about his often difficult sometimes estranged relationship with his father. In a culture of sentimentality and pretense, the sort of truth-telling that this sanctuary makes possible— that’s politics.

Later this afternoon, a group from church will go up to Sleepy Hollow Nursing Home to worship with elderly residents who may not be able to hear it or comprehend it. In a culture like ours that is determined to get out of life alive— a culture that worships at the altar of youth and achievement— the old are cloistered away and cast-off.

It’s a simple thing some of you will do at Sleepy Hollow. But make no mistake, it’s a politics.

Bring it home. All politics is local. Well done.

The way God has chosen to heal the world is the Church— that’s what we forget whenever we argue about the Church and Politics. The politics of Christians ought to be unintelligible if God has not raised Jesus Christ from the dead.

We’re the nard that God has purchased at great cost to lavish Christ upon the dying world.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 24, 2022

Two Ways to Go to Hell

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

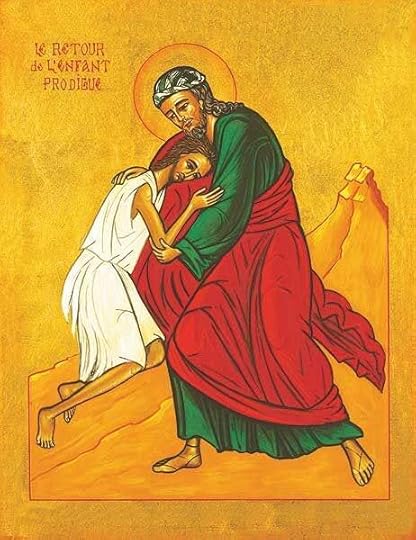

The lectionary Gospel passage this coming Sunday is everyone’s favorite parable. The Parable of the Prodigal Son. Or, is it better understood as the Parable of the Prodigal Father? For that matter, which of the father’s two sons is truly the lost boy?

If you read Luke 15 closely, it’s the party that sets him off. Whatever resentments the older brother was harboring, whatever anger lay buried inside him already, it’s the singing and the dancing and the feasting and the rejoicing that send him over the edge. Why shouldn’t it?

Ancient Judaism had clear guidelines for the return of a penitent.

Ancient Judaism was clear about how to handle a prodigal’s homecoming. There was nothing ambiguous in Ancient Judaism about how to treat someone who’d abandoned and disgraced his family.

It was called a kezazah ritual, a cutting off ritual.

Just as they would have done when the prodigal left for the far country, when he returned home members of his community and members of his family would have filled a barrel with parched corn and nuts. And then in front of everyone, including the children- to teach them an example- they would smash the barrel and declare ‘This disgrace is cut-off from us.”

Having returned home, thus would begin his shame and his penance. So you see, by all means, let the prodigal return, but to bread and water not to fatted calf.

By all means, let him come back, but dress him in sackcloth not in a new robe. Sure, let him come back, but make him wear ashes not a new ring. By all means let the prodigal return, but in tears not in merriment, with his head hung down not with his spirits lifted up. Bring him to his knees before you bring him home. It’s the party that sets him off.

Here’s the thing.

The elder brother— he’s absolutely right.

Everyone calls this the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Everyone always has, but Jesus doesn’t steer this story so you’ll be confronted by the younger brother. Jesus leaves this story deliberately hanging…

With the elder brother standing outside the celebration, refusing to join in, refusing to swallow his pride, choosing to be right rather than rejoice with the Father.

The prodigal’s sin is obvious. We don’t need a warning story to teach us that it’s wrong to wish our father dead and burn through his fortune on DraftKings. At least, most of us don’t need that kind of warning.

The other brother’s sin is harder to spot, but it’s also closer to home. And Jesus wants us to know that it’s just as treacherous.

I’ve done enough pre-marital, marital, and divorce counseling to know. I’ve planned enough funerals. I’ve led enough small groups and Bible studies to know.

Just about every one of you could tell a story...

about outstanding grievances

about someone who if you saw their name on the invite list you’d say “no thanks” and turn back the other way

about someone who hurt you

or broke something in your life

or took something from you that can never be given back.

Every one of you could give this parable your own details and cast it with the characters in your own life and stage it around your own dining room table. Every one of you could tell a story about a relationship that was left to flounder or half-heal because contrition is still past due.

And I’m sure you’re a good person. You’re probably right in most cases.

I’m sure you have your reasons and your justification. I won’t argue with that. But you should know. You should know what Jesus wants you to know.

There’s two ways to go to hell.

Sure there’s the obvious way.

But refusing to celebrate what fills the Father with joy

Wanting to charge someone for the same grace that was freely given to you

Begrudging another mercy when it was offered to you

Wishing justice for someone when you received pardon

Well, you can be good and you can be right and you can be justified, you can be

religious, and you can have all the right reasons.

And still be every bit as wayward as a prodigal.

And just as far from Home.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 21, 2022

X Marks More Than One Spot

Arguably the most important Easter scripture speaks not of the women running from the tomb in terror or Mary mistaking the naked Christ, newly delivered from the dead, for the Gardener. “By this Gospel you are saved,” the Apostle Paul writes, “for what I received I passed on as of chief importance: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures.” And Paul continues for thirty more verses without once bothering to mention a new hewn tomb or a stone rolled to the side or an angel of the Lord sitting on an image of Caesar. “If Christ has not been raised,” Paul argues, “our preaching is in vain and your faith is a waste of time…for if Christ has not been raised we are all liars and you are still in your sins.”

The oldest sustained Easter account comes not from Matthew, Mark, Luke or John but from St. Paul, and what St. Paul gives us isn’t a story with angels and an empty tomb. He gives us an argument that the grave really is empty. He marshals evidence that Jesus Christ IN FACT has been raised from the dead.

Christ was buried, Paul reminds them. As Paul puts it in the Book of Acts, “these things didn’t happen in a corner.” In other words, Christ’s empty tomb first was proclaimed to the very people— Paul names over five hundred of them— who had seen him die and who could have gone to his grave with a wheel-barrow and brought back for themselves his nail-scarred bones (had they been there).

For my part, I’ve long felt the strongest argument for the veracity of the Bible’s Easter Gospel is that Jesus of Nazareth was only one of hundreds of thousands crucified by the Roman Empire all of whose names are lost to us.

Hell, the Gospel texts themselves make no bones about disguising the fact that Jesus isn’t even the only person crucified by Rome on Good Friday. The Christ called Caesar crucified thousands upon thousands across the empire— it’s how he kept Pax in the Romana, yet out of all those scores of people who were nailed to a tree we know only the name of Mary’s Son.

Take these two facts together, and I am convinced that we would not know the name of Jesus Christ had God not raised him from the dead. Having visited Jerusalem the last three days and visited the holy sites, I still believe this is the strongest case for the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead.

Before I left for Israel a friend, Todd Brewer, wished me luck on my pilgrimage and said to me, “The Holy Land is a wonderful reminder how Christianity is a crazy, strange religion.” I didn’t know what he meant exactly until the final third of our journey brought us to the City of Peace founded by the King whose name means peace, Schlomo or Solomon. Two days ago we visited the Garden Tomb where Jesus’s body was laid on a stone resting table in a niche cut of the rock in what today looks like an English garden. A massive olive or grape press is nearby and, just down the path, a rock face whose indentions resemble the eye sockets and nose bridge of a skull.

Jesus, the Gospels tell us, was taken to a place called the skull and there they crucified him.

The place of the skull is on the side of what was once a road. Caesar preferred his electric chairs on thoroughfares since deterrence was his objective not justice. Almost fittingly, today the place of the skull sits in a bus parking lot with a shawarma restaurant on one side and the minaret of a mosque on the other side. Perhaps because of the minaret, the entrance to the Garden Tomb was guarded by two car loads of Israeli police who looked no older than my sophomore son.

The Garden Tomb was a moving and holy place, even to this tamed cynic.

Yesterday we visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The name of the church is a misnomer as it houses four different churches. Thanks to the archeological acumen of the Byzantine Queen Helena, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is the site of— get ready for it— Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. Amidst a dizzying array of icons and frescoes, lanterns and censors, the Holy Sepulchre enshrines the remains of the cross, a rock stained with Christ’s blood, and pieces of the rock that the angel of the Lord drop-kicked open.

The Holy Land is an ancient time machine built with both old and living stones.

You can’t spend but a moment here without being confronted with the awkward fact that Christianity, like Judaism before it, is an embarrassingly historical faith.

Take Buddhism, for example. The truth or utility of Buddhism does not ultimately depend upon whether or not the Buddha ever sat under the Bodhi tree. The same is true of pagan myths (and most versions of progressive Christianity for that matter). But, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15, if Christ has not been raised from the dead— in history— then we are the most pathetic people in the world. We’re false witnesses. Liars even. Worse, we violate the first commandment as a first principle, worshipping someone other than Yahweh as Lord. You don’t have to believe it, but you owe it to the first Christians to take their testimony or leave it. They didn’t believe the resurrection message was a metaphor or a myth. They didn’t think Easter was really about timeless truths. They thought it was true. That it actually happened. In history. At Jerusalem. Under Pontius Pilate. During the reign of Caesar Augustus. On the Sunday morning after the Passover when he died between noon and 3 in 33AD. Around tea time, as Monty Python’s Life of Brian puts it. Christianity is not a worldview. Christianity is not a philosophy. It’s not a social program or a political agenda. It’s not advice or a way of life or helpful lessons for your kids. Christianity is not a tradition of teachings or a set of spiritual practices. It is not even a morality.

The Gospel is news.

It’s an announcement of an event that has happened outside of you, in history, that bears implications for you.

But an announcement is not an attestation.

Sitting next to the Garden of Gethsemane, the Church of All Nations, according to Catholic teaching, is the site of Mary’s bodily ascension into heaven. Just across the street, however, near the city wall, in a Greek Orthodox graveyard is the tomb of Mary, who did not ascent into heaven but awaits the return of the Son like all the rest of his brothers and sisters.

In Israel, X sometimes marks more than one spot.The City of David is replete with these inconsistent, often contradictory memorials, and, Todd’s right, somehow this is exactly how it should be for Christianity. While the Holy Land confronts you with the Gospel’s unabashed, inconvenient claim to historicity, it also elides any possibility for you to receive the glad tidings with any kind of self-generated confidence or evidence-derived certainty.

The promise of the Gospel is that, in Christ, you were born again on a Friday afternoon in 32 AD, on a hill, a few minutes walk beyond the Temple Mount. It happened. In history. But we can’t tell you where exactly. Jesus says he can make even the stones cry out, but, in the meantime, none of the available rocks can prove our message beyond a shadow of a doubt.

In a city dominated by Catholic and Orthodox churches, I departed today, smiling, that Christianity’s imperfect and elusive historical record here is an unwitting witness to the wisdom of the Protestant Reformation.

Protestantism doesn’t have the impressive cathedrals here in the Holy Land. We don’t have any relics or sites worth the gas money. There are no exquisitely details mosaics from the Reformation period here. What we do have is the unavoidable, abiding takeaway that, at the end of the day, the historicity of Christianity notwithstanding, there is nevertheless no way to receive the Gospel on any other basis but faith alone.

We can mark the spots on the pilgrim’s maps with X’s, but the Gospel is the same here as anywhere else. Ultimately, all we can do is trust. All we can do is what Adam and Eve would not do— take God at his word.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 19, 2022

“I am counted with them that go down into the pit”

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

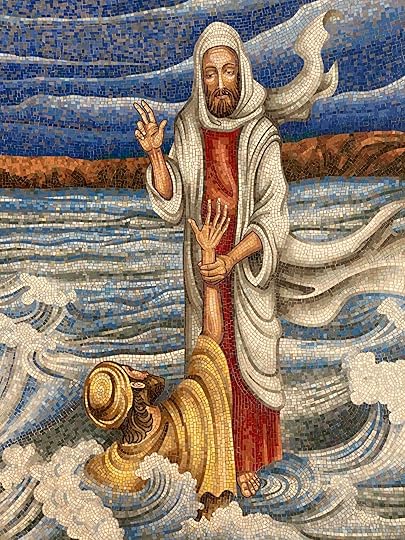

On an almost sheer hillside, the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu stands on the eastern slope of Mt. Zion. A golden rooster rises from the domed steeple. Indeed roosters’s crows can be heard all over the adjacent city of David. “Gallicantu” means “cock’s crow” in Latin, and the church pays homage to Christ’s prophesy that Peter would deny him three times “before the cock crows.” It’s here that Peter— the first one to name Christ rightly (“You are the Messiah!”)— warms himself by a charcoal fire, too cowardly to admit he’s even heard of Jesus of Nazareth and too cold to care that his own Galilean accent gives him away.

Jesus? Jesus of Nazareth? Never heard of him.

“I do not know the man.”

x3

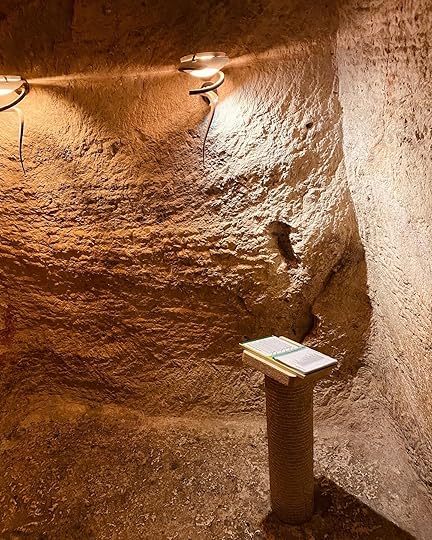

Peter’s threefold denial of Jesus is recorded in all four Gospel accounts of the Passion, and the evangelists report that the scene of Peter’s betrayal is the courtyard of the high priest Caiaphas. Thus, it’s not surprising the Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu, on its lower levels, contains both a guardroom and a prisoner’s cell hewn out of bedrock. Much like diplomatic offices today, in Jesus’s day, the position of high priest was less a religious role and more a political position purchased at a great price. The high priest functioned as the local municipal officer, not unlike a mayor, so it’s not surprising that Caiphas’s palace would contain a jail cell. The guardroom at St. Peter in Gallicantu contains wall fixtures to attach prisoners’ chains. Holes in the stone pillars would have been used to fasten a prisoner’s hands and feet when he was flogged. Bowls carved in the floor are believed to have contained salt and vinegar, either to aggravate the pain or to disinfect the wounds. The prisoner’s cell at Gallincantu not only offers an arresting insight into where Christ spent the night before he was crucified, it also conveys— in a way that an abstract, visualized crucifixion never could— the abject and utter hopelessness that must have enveloped Christ in those final hours. The only access to the bottle-necked jail cell at Gallicantu is through a shaft cut in the bedrock above. Having been beaten and flogged, Jesus would have been bound and then lowered through the hole in the rock by means of a rope harness.

From the floor of the pit to the top of the hole is twenty-five feet. Plus, the prisoner is bound. Once Jesus is down there, inside the pit, there’s no way out. There’s no hope. There is no one.

Standing in the pit today at Gallicantu, I was overwhelmed by the sensation of loneliness that surely accompanied Christ to the cross. While his friend Peter is above ground, just outside the palace walls, Jesus may as well be dead already, hidden like diamond deep in the dirt. If not earlier, Christ’s cry of forsakenness surely started here.

Today, a simple, spare lectern with a spiral bound notebook rests on the floor of the pit. The notebook contains Psalm 88 transcribed in hundreds of languages, from Armenian to Ukrainian. To an extant that will make you second-guess your functional atheism, Psalm 88 seems to refer to Christ as he languished in a dark stone hole. Christ alone in the pit seems to have been on the mind of God long before God was in Christ.

Psalm 88 reads:

“O lord God of my salvation, I have cried day and night before thee:

Let my prayer come before thee: incline thine ear unto my cry;

For my soul is full of troubles: and my life draweth nigh unto the grave.

I am counted with them that go down into the pit: I am as a man that hath no strength:

Free among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, whom thou rememberest no more: and they are cut off from thy hand.

Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit, in darkness, in the deeps.

Thy wrath lieth hard upon me, and thou hast afflicted me with all thy waves.

Thou hast put away mine acquaintance far from me; thou hast made me an abomination unto them: I am shut up, and I cannot come forth.

Mine eye mourneth by reason of affliction: Lord, I have called daily upon thee, I have stretched out my hands unto thee.

Wilt thou shew wonders to the dead? shall the dead arise and praise thee? Selah.

Shall thy lovingkindness be declared in the grave? or thy faithfulness in destruction?

Shall thy wonders be known in the dark? and thy righteousness in the land of forgetfulness?

But unto thee have I cried, O Lord; and in the morning shall my prayer prevent thee.

Lord, why castest thou off my soul? why hidest thou thy face from me?

I am afflicted and ready to die from my youth up: while I suffer thy terrors I am distracted.

Thy fierce wrath goeth over me; thy terrors have cut me off.

They came round about me daily like water; they compassed me about together.

Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness. “

When I was a student at Princeton, I took a class on the Death of Jesus. Our professor, Dr. Donald Juel, began the first session of the course with the obvious question, “Why did Jesus have to die?” You don’t even need to be a Christian to know many of the answers that popped up from those who raised their hands. Down through the centuries, the theologians have called such explanations to Dr. Joel’s question, “atonement theories.”

Jesus dies to pay our debt of sin, some explain.

Jesus defeats the power of Death and Sin, others answer.

Jesus is the Second Adam.

Jesus is our Passover.

Jesus is our Ultimate Scapegoat.

Say theologians.

In one sense, the eerie and unmistakable manner in which Psalm 88 prophetically foreshadows the pit in which the Man of Sorrows is imprisoned lends credence to the argument that the cross of Christ is a work of divine necessity. As Caiphas’s crooked cops lower the beaten Jesus down into the bedrock hole clearly, we could conclude, some predetermined plan of the Father for the preexistent Son is clicking into gear.And yet—The unyielding silence of the hewn out hole, the sheer solitariness of the pit beneath the palace, demand, I believe, a more mundane and everyday explanation.

It’s perhaps a more threatening explanation too.

Jesus dies because we killed him.

The theologian Gerhard Forde writes that conspicuously missing from the way most Christians speak of the crucifixion is the brute fact that we killed him. We’ve so pushed the cross into the realm of theory, anchored it to divine necessity (what Forde calls “covering the cross with roses”) that we forget the cross was an event, in actual history, as real as any story in the newspapers, the end result of a basically simple story: In Christ, God came preaching the unconditional forgiveness of sins for sinners who do not deserve it, and we killed him for it. Jesus is the one in whom God did God to us. He did God’s mercy and forgiveness to us. He bore relentless witness to it; therefore, he had to die. And not just die, his reckless message had to be hammered into oblivion.

Well, first we beat him and then dumped him in a hole in the basement while we figured out how to justify it ex post facto.

I stood this morning in the cold, dark pit at the bottom of the chief priest’s palace, and I thought that, actually, perhaps the best “explanation” for the death of Jesus is that Jesus died because the very best of society— church and state, soldiers and citizens— simply agreed with Caiphas.

“We have no king but Caesar!” the chief priest insists to Pontius Pilate.

We conveniently forget—

Judaism was a shining light in the ancient world, offering not only a visible testimony to God who made the heavens and the earth but a way of life that promised order and stability and well-being of the neighbor. And in a world threatened by anarchy and barbarism, the Roman empire brought peace and unity to a frightening and chaotic world. The people who did away with Jesus— Pilate and his soldiers, the chief priests and the Passover pilgrims gathered in Jerusalem— they were all from the best of society not the worst. And they were all doing what they were appointed to do. What they thought they had to do. What they thought was necessary for the public good.

The chief priests’s reasoning (It’s better for one man to die than for all to die…”) is not only a perfectly rational position it’s the best explanation for how Jesus spent his last night in a cold, dark hole as quiet as hell.

Theologians give explanations and theories:

Jesus had to die in order for God to be gracious.

Jesus had to die in order for God to forgive us of our sin.

Jesus had to die to pay a debt we owed but could not pay ourselves.

I’m not arguing that such theories are wrong or unhelpful or contrary to scripture. Many of them are quite helpful in illuminating the crucifixion. But as I listened to Psalm 88 echo underneath what was once Caiphas’s palace, I couldn’t shake the conviction that they are not the best explanation for why Christ was forsaken in the pit. The best explanation for Jesus, like Joseph, being dumped in a hole in the earth and left for dead is the bitter news that this is the only possible conclusion to God taking flesh and coming among us. In Christ God gets close, and we respond by pushing him as far away from us possible, first in a hole hewn in bedrock and later pushed out of the world on a tree.

The theologians attempt to give us answers for the crucifixion.

But the Passion stories themselves leave us to wonder, simply, if this is the best we can do?

The theologians explain.

The Passion stories leave us to wonder if the only possible result of God-with-us—God with people like us— is us dumping God in a hole like so much rubbish, a pit where God-with-us is made all alone.

The horrific silence of Christ’s hole should chasten us who are quick to find good news in an even more brutal experience.

I left the pit under Caiphas’s palace today thinking, “Isn’t it ironic? The only person who can touch us and heal us and forgive us and make us whole was dumped in a basement hole, forsaken, and left for dead.”

What’s true of his garden tomb is true of his hole in the bedrock, but I think it took the latter today to help me realize the former: our only hope in this world is that God will not leave him there.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 18, 2022

Monsters at the Manger

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

As you enter and leave the Orthodox Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth, you can’t help but see— you’re encountered by— a large fresco on the ceiling illustrating the Slaughter of the Innocents. Joseph carries baby Jesus, like an emergency go-bag thrown over the shoulders as an invading army’s artillery gets too close for comfort. In the bottom right hand corner of the scene— soldiers with blood orange swords kill children on a jealous tyrant’s orders. It’s a reminder of the cost that comes with Mary’s “Let it be with me according to thy word.”

Every Feast of the Incarnation I make a point to begin my sermon by reassuring folks that, no matter how disarrayed their life is generally or their Christmas Eve particularly, there is a place at the manger for them. It’s all too easy for those who crowd into church on Christmas to conclude that the bedlam in their lives somehow disqualifies them from befriending the Holy Family. This is a judgment that is as odd as it is commonplace. At least according to the scriptures, the first Christmas was no less clamorous and chaotic for Mary and Joseph than it is today for the brothers and sisters of their child.

Despite what we sing on Christmas Eve, it was not a silent night. According to the Gospel of Matthew, sometime after the shepherds returned to their flocks and the magi found a different route home, after Mary and Joseph wrapped him in bands of cloth and laid him in a trough, all the other mothers and fathers of sons in and around Bethlehem lay their babies in their cribs and tuck their toddlers into bed.

And while they sing them a lullaby or tell them a Bible story or kiss them goodnight on the forehead, they hear:

The sound of boots stamping down the dusty roads

The sound of doors being knocked on and kicked down

The scraping sound of metal on metal as swords are unsheathed

The chaotic sounds of orders being shouted

And fathers being shoved aside

And mothers gasping

And babies being taken.

Mary and Joseph sneak away across the border with no money to their name. Luke’s nativity tells us about the angels who sing, “Glory to God in the highest heaven.” But Matthew tells us those same skies fill with the cries of mothers and fathers as their sons are silenced forever.

The Gospel of Matthew tells the Christmas story with the steely-eyed recognition that this world often resists our stubborn sentimentality and is frequently and shockingly horrible. It’s a world where despots plot and evil flourishes and the innocent are victims. It’s a world where the poor are powerless and the powerful do whatever they please and long suffered injustices fester. The unease many churchgoers feel on Christmas Eve is but a distant, thin ripple downstream from the bedlam that marks God’s arrival into the world at Bethlehem.

As Fleming Rutledge puts it, Christ is born with monsters at his manger.

Which makes it both totally fitting and appallingly poignant that the bedlam and heartbreak of his birthplace abides.

Today, the minaret of a mosque stands opposite Nativity Square, seemingly unmoved or unimpressed by the Gospel’s claim that the crèche a block away is the cradle of creation. A busy street laced with street lights and crosswalks snakes past the Church of the Nativity. The honking horns of cars caught in traffic and the whistles of policemen at intersections interrupt the solemn prayers of the pilgrims who all bow in humility as they enter through the short church doorway. Crossing over from Israel into the Palestinian Territory and the West Bank, I had to go through a security checkpoint to reach Bethlehem. Graffiti, both righteously angry and winsomely prophetic, covers the West Bank Barrier and stands as an omnipresent backdrop to the gilded leaf altar of the Orthodox Church of the Nativity. Today, the city of Christ’s birth is guarded not by heavenly host but by Palestinian police controlled by the Israeli military. Due to the confusing apartheid-like system of classifying Palestinian Muslims and Christians, only some of the residents of the Holy Family’s city can leave it for the City of David. As a consequence, young men loiter the streets around the site of Christ’s birth with nothing to do, no dreams to entertain or hopes to harbor— unemployment in the West Bank exceeds the worst of the American Depression in the 1930’s. Even the staff at the hotel here in Bethlehem, good jobs to be sure, make less than $700 a month.

Visiting the place of Christ’s birth for the first time, I can’t shake the suspicion that we often drape the Christmas story in sentimentality for self-serving reasons and that the gloss with which we redact the text has victims more serious than the visitors who feel slightly uncomfortable in our pews. Those who can most identify with the way King Herod thrusts innocents into the gears of geopolitics are precisely those who live in Bethlehem today— a city that remains Christian— caught in the quagmire of the Israeli-Palestinian “conflict.”

At the same time, I can’t avoid the truth that it’s Christians in America who are least likely to identify with the Christians in Palestine.

They can see themselves in Matthew’s frighteningly everyday story while we celebrate it with warm candle glow and tender lullabies. It turns out that, two millennia later, paying homage to the place of his birth is no less complicated than was the occasion of his birth. And honestly, sitting here in the Hotel Saint Gabriel in the West Bank, the situation in Bethlehem feels every bit as hopeless as it must have the day Herod’s soldiers rolled through with their blood orange swords. And then— the silence that ensued.

This surprising, disquieting equivalence between the bedlam of Bethlehem then and now left me yesterday longing for the Church of the Nativity to offer me more. More than a short door that necessitates a work of humility. More than a crèche stone rubbed smooth by the adoring hands of pilgrims. More than a dizzying array of colorful icons and paramount covered walls.

I needed a word.I needed a promise.The Church of the Nativity needs, I concluded, a preacher.

And it doesn’t need to be someone in a collar or robe. It doesn’t need anyone swinging a chain and censor or a standing astride a pulpit. A guy with a sandwich board and megaphone on the street corner would do.

As much as ever, the place of Christ’s birth needs the promise declared at his birth— the promise that the Light yet shines in the darkness and the darkness has not and does not and WILL NOT overcome it.

The promise just has to be true.

Because we, with our alleged free will, have not come up with any solutions.

And as for me, I’ve got nothing.

For me, faith only ever feels like a gift.

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 16, 2022

The Scandal of Particularity

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In her book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard observes, “That Christ’s incarnation occurred improbably, ridiculously, at such-and-such a time, into such-and-such a place, is referred to—with great sincerity even among believers—as “the scandal of particularity.” Well, the “scandal of particularity” is the only world that I, in particular, know. What use has eternity for light? We’re all up to our necks in this particular scandal.” The Monty Python film, Life of Brian, makes the same wry point about particularity by noting that the crucifixion took place on Good Friday at Golgotha “around tea time.”

Most of us assume that that which is most universal is most true.

From general principles, we can apply the truth to individual cases. The particular here below is but an instantiation of an overarching truth established above and beyond the specific. For example, God is Absolute Good, we reason and then find that prior principle of goodness embodied in the person of Jesus. It’s precisely because we assume, by default, that truth works top down, from the universal to the specific, that, ever since God heard the cries of a particular people in captivity and shortly thereafter promised to them that they and they alone would be his chosen people, the world has responded to Israel’s profession of faith with persecution and charges of elementariness. The pagan world met the glad and audacious tidings of the gospel with the very same ridicule. As Dillard notes, theologians call the principle that goes against the grain of our natural reasoning, moving from the concrete to the universal, “the scandal of particularity.”

The medieval theologian Duns Scotus attempted to lend the scandal of particularity some philosophical legitimacy, asserting that God only created particulars and individuals, a quality he named “thisness” (haecceity). Thisness grounds truth in the concrete and the specific. You can’t really love universals, Scotus argued. It’s hard to love concepts, forces, or ideas. Ideology, it turns out, is just the ego wrapping itself around such abstractions. Nevertheless, even the philosophical cosmetic surgery worked by the “Subtle Doctor” can’t erase the offense of the incarnation.

You don’t get more specific or more salacious than the claim that the Maker of Heaven and Earth, Goodness Itself, the unseen, underlying Principle that makes even 1+1 = 2, took up residence in the womb of a particular Jewish girl named Mary in a certain place called Nazareth in a specific region named Galilee.

God then lived briefly, died violently, and rose unexpectedly. Even worse, this God has elected not only a particular people out of all the world, he has elected to make himself known to the world not through a means available to all but through the witness and proclamation of an imperfect few.

The scandal of particularity is the challenge every (honest or self-aware) preacher faces when preparing a sermon for Christmas Eve, “And the Word became [this] flesh and took up residence among [them].” The scandal of particularity is served up, front and center at the table, as obvious and unavoidable as the bread and the wine, “When we turned away, and our love failed, your love remained steadfast. You delivered us from captivity, made covenant to be our sovereign God, and spoke to us through your prophets…” The we in the Great Thanksgiving refer to us only secondarily. It refers primarily to the particular people called the Jews. Whenever a believer or inquisitor wonders how it is that he or she can be incorporated into God’s saving work if that salvific work comes by way of Christ’s own unique body, they are grappling with the scandal of particularity.

As a preacher, I’ve been working with, apologizing for, or generally avoiding the scandal of particularity for two plus decades. It’s always easier, after all, to treat Jesus as the exemplification of a principle we knew or believed before we met Jesus— what better way to avoid picking up a cross and following him.

All this time I thought I understood the scandal of the scandal of particularity—How odd of God to choose the Jews?

How dare God aim at saving all by starting only with some?

How can the infinite become finite?

Yesterday I visited Capernaum, and I realized just how much of the particulars of the scandal had passed me.

Capernaum is on the Sea of Galilee, a short walk from where Jesus delivered his Sermon on the Mount— that we even know these particulars with certainty is chilling. According to the Gospels, Jesus makes Capernaum his base of operations after his initial sermon in his hometown of Nazareth meets with something worse than, “That was interesting, pastor.” They drive Jesus from the synagogue and attempt to throw him off the cliff. So Jesus escapes by a hair and moves on to Capernaum. In Methodism we call this “itinerancy.” Outside of the Passion, most of the stories you associate with Jesus take place in Capernaum.

Jesus teaching in the synagogue: Capernaum.

Jesus healing Peter’s mother-in-law in her home: Capernaum.

Jesus healing the Centurion’s daughter: Capernaum.

Jesus healing the woman with the issue of blood: Capernaum.

Jesus healing the poor bastard whose friends lowered him through the insulation of the roof: Capernaum.

Jesus healing the man with the whithered hand: Capernaum.

The leper at the steps: Capernaum.

The whole “fishers of men” bit: Capernaum.

The charcoal fire by which the Risen Jesus reenacts the scene of Peter’s denial and forgives him thrice: Capernaum.

As someone who works with these texts for a living, I of course knew the setting these stories all share. It wasn’t until I was standing in Capernaum yesterday, however, staring down into the actual remains of Peter’s inheritance, that I realized how incredibly proximate every part of Capernaum was to every other part and how close Capernaum itself was to every other part of Jesus’s pre-Jerusalem ministry. When Jesus departs to go to the “other side” into Gentile territory, for example, he travels no more than a distance I could swim. The “town” of Capernaum occupies a square footage not much bigger than the real estate owned by my local church. The Gospels report that after teaching in the synagogue, Jesus went to the home of Peter’s old lady. I didn’t realize until this week that that trip probably took Jesus fifteen seconds. Likewise, Peter’s mother-in-law probably could’ve smelled the leper begging on the steps of the synagogue so close was her home to the Father’s house. The roof a cripple’s friends dug to get to Jesus is no further from the disciples’s fishing dock than first base is to third.

What the maps in the back of your Bible can’t convey, what the Jesus movies sure as shit don’t make clear, is that the bulk of Jesus’s ministry takes place in a space smaller than a planned community in the suburbs.

Thus, the scandal of particularity is even more scandalous, the canvas of God’s saving work is even smaller than Mary’s womb. Jesus preached and enacted the Kingdom among people who knew him and whom he knew. The cramped dimensions of Capernaum are such that there’s no way Jesus did not recognize the man with the withered hand or know the name of the man lowered threw the dry wall on a stretcher.

Even more scandalous—

When these folks reject Jesus, as they all ultimately do, they’re not rejecting a type of Kingdom preacher, a general instantiation of messiah, the latest iteration of a universal God principle.

They’re rejecting Jesus.

They’re abandoning the guy who lives fourteen feet over there. They’re turning away from the one whom they knew and who knew them. The scandal of particularity— I’ve learned only by virtue of being here— applies not simply to the way in which God took particular flesh but the way in which flesh rejected the particular God with whom they’d taken up residence.

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 15, 2022

The Lay of the (Holy) Land

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

When he was a child, every Palm Sunday Karl Barth would rush to the window of his family’s church and press his face against the glass in order to spy a glimpse of Jesus trotting down the streets of Basel, Switzerland atop a donkey, cloaks and palm leaves laid on the path before him and shouts of “Hosanna” hanging in the air. The stories of the Gospel so captured the future theologian that he heard them as present-tense announcements of news. The narrative illuminated the land around him as though the two were necessary for a proper proclamation. Similarly, Christians have long referred to the Holy Land as an interpretative companion to the Gospel, the place of Jesus’s preaching of the Kingdom as a necessary hermeneutic to a right apprehension of it.

I’ve always felt reluctant to travel to Israel. As a preacher, I’ve been wary of Christian kitsch and tourist tchotchke ruining the scenes the evangelists in my mind’s eye. If you can hardly travel anywhere in Virginia without a convenience store or Cracker Barrel hawking a three-cornered hat, I figured, Israel must be replete with Jesus Junk and Lego editions of Heroes of the Torah.

I was wrong.

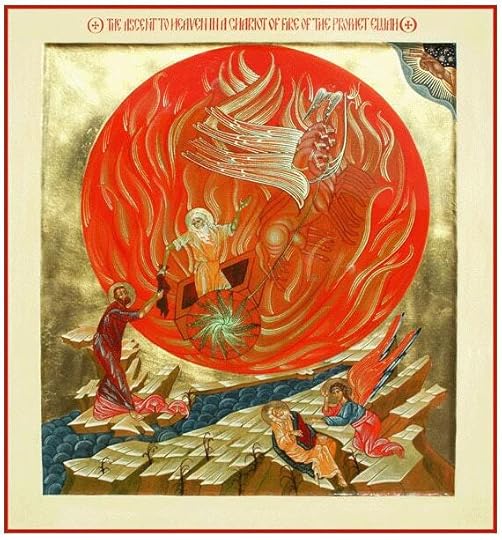

Thus far, I’ve seen very few trinkets and, only three days into my journey, I’ve quickly realized what the Church Fathers meant by calling the Holy Land the Fifth Gospel. For example, I stood on the grounds of the little church that sits at the top of Mount Carmel. In case you’ve forgotten your Sunday School, Mount Carmel is the site where King Ahab summons the prophet Elijah as well as the 450 prophets of Baal. It’s like a Top Chef Finalist Competition but with higher stakes. King Ahab’s men butcher some bulls and bring out fire wood for the showdown between the barren deities of Canaan and the God who heard his people’s cries and raised them from captivity in Egypt.

The contest is simple.

“The God who answers by fire,” Elijah declares, “that god is God.” The hundreds of false prophets— be warned: I’m sure they were sincere in their false piety— pray to their barren deities from morning to noon with the sorts of loud cries and outsized affectations you might see on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. Nada. So after lunch, Elijah has his seminary interns pour four jars of water all over the wood of his altars dedicated to Yahweh. For added measure, Elijah has them pour water a second time and then a third. Finally, Elijah doesn’t so much as raising his voice. He prays, simply, “O Lord, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, let it be known this day that you are God in Israel, and that I am your servant, and that I have done all these things at your word. Answer me, O Lord, answer me, that this people may know that you, O Lord, are God, and that you have turned their hearts back.” And fire falls from the sky and consumes the entirety of Elijah’s offering.

A feature of the story we’ve successfully excised from our Sunday School memories is that, having defeated the prophets of Baal without raising a finger, Elijah drags them one-by-one down the mount to the Kishon wadi where he takes up the sword and lops off their heads.

I’ve preached this text several times over the course of twenty some years. It is to preachers what a Gary Clark Jr. tune is to guitarists. It’s a big, thick text to better yourself as a preacher precisely by failing to master it. But I lacked the young Barth’s felt connection to the land as a necessary hermeneutical lens.

It never occurred to me until now that Mount Carmel, the wadi Kishon, and the prophet who takes up the sword with the vengeance of the Lord upon him all take place straightaway across the valley from the gentle, rounded slopes of Mount Tabor.

It’s barely a cross-country run from the one mountain to the other mountain, each plainly visible to the other even on a cloudy day.

Mount Tabor is also known as the Mount of Transfiguration. It’s the place where Jesus, like the Burning Bush before him, is afire with the glory of God but not consumed by it. Elijah and Moses, representing the Prophets and the Law, appear alongside the beautified Son as the Father doubles down on his baptismal declaration, “This is my beloved Son— listen to him!” Preachers often chide Peter because he responds to the transfiguration by wanting to preserve the epiphany and remain on the mountaintop, “Let us make three booths, one for each of you, and abide here with you.” The hackneyed preacher’s trope suggests that Peter, who’d foolishly attempted to defy gravity on the lake, once again fails to understand. The life of a follower of Jesus is back down in the valley, Peter, with our sleeves rolled up to serve a creation still groaning in labor pains.

Yesterday I stood on top of Mt. Carmel and looked down at the wadi that winds its way from the site of Elijah’s slaughter to the Mount of Transfiguration and I thought that perhaps Peter understood far better than we preachers give him credit.

Perhaps Peter understood that in this Jesus of Nazareth God’s People finally had a prophet better than Elijah.

It’s only after being here and seeing the joggable distance between Mt. Carmel and Mt. Tabor that I understood the snatch of conversation Jesus exchanges with James and John, whom Jesus calls “sons of thunder.” They’re on their way to Jerusalem by way of a village of Samaritans, traditional enemies of the Jews. When the Samaritans, as expected, do not welcome Jesus into their homes, the sons of thunder ask, “Lord, do You want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?’”

Elijah had done it.

Why don’t you do it and be done with them, Jesus?

“Jesus turned and rebuked James and John, and said, “You do not know what kind of spirit you are of; for the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

The sons of thunder didn’t yet know what the one whom Jesus calls the rock had already intuited by looking across the valley at Elijah’s mountain and the wadi that once had run red with blood and hearing the Father insist that Jesus— NOT Elijah— was the prophet to be heeded.

Stanley Hauerwas says we cannot know the Kingdom unless our eyes are opened to see it. Being here, I think Stanley’s point applies to the land as much as it pertains to any spiritual perception.

The particular geography of Jesus’s of ministry makes unavoidable the lesson his cross and empty tomb make universal.

More than a prophet, Jesus does not take up the sword. He suffers it.

As a crucified Christ, Jesus does not call down on sinners the fire of God’s wrath. He’s consumed by it.

As God in the flesh, Jesus does not destroy his enemies. While they were yet his enemies, Christ dies for the ungodly.

It’s the message of the cross, sure. It’s the Gospel in nuce, no doubt. But, long before he gets to Jerusalem, it’s a lesson woven into the lay of the land. Peter was right on Mount Tabor. In Christ, we have been given not a prophet who abides by our sense of justice. We have been given a still greater One in whom it is good and right for us to abide.

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

March 13, 2022

The Shocking Freedom of “Faith Alone”

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In Lent, it’s helpful to remember the good news that there’s NOTHING you have to do. Here's theologian Gerhard Forde on the shocking freedom of the message of justification through faith alone:

Stick with it and sail into the storm with all guns blazing. 'We have to do something, don't we?' NO! In fact that is no longer the question. Now the question becomes, 'What are you going to do now that you don't have to do anything?' [Protestant] theology based is not interested in 'something'; it is after everything.

A pastor friend related an interesting reaction from a teenager to [this notion]. . . . It seemed to tell him he could do anything he wanted to do! Now what is one supposed to say to that? The most immediate reaction, I suppose, would be to jump in on the defensive and thunder, 'No! No! No!--of course not, you can't do whatever you want to do!'

But think for a moment. Perhaps then the whole battle would be lost. One must sail into the storm. Should one not rather say 'Son, you are right. You got the message. The Holy Spirit is starting to get to you.'

But is that not dangerous? . . . Is it not 'cheap grace'? No, it's not cheap, it's free! 'Cheap grace,' you see, is not improved by making it expensive. . . . It's free. Now free grace is dangerous, no doubt about it. . . . We might not survive such free grace. It might ruin us. But Jesus told us that long ago: 'To him who has, more will be given, but from him who has not, even that will be taken away.'

There is indeed a danger.

--G. Forde, Justification by Faith: A Matter of Death and Life (Fortress 1982), 33-34; italics original

March 11, 2022

The [Victims of War] You will Always have with You

(Ivanka Demchuck: Transfiguration)

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Around the start of Russia’s invasion, I purchased an icon from an artist in Ukraine. After she apologized to me for any delays that might arise in delivery, I emailed back to her, “It’s horrible what’s happening to your country…” She replied, “We have hope!”

How can you have hope in a hopeless situation? I thought.

Among the theological virtues— faith, hope, and love, the apostle Paul declares that only love ultimately abides. Love alone lasts eternally because by “love” Paul has in mind Christ Jesus, who is without beginning or end. Faith is impermanent, for one day we will know by sight what we now can merely trust. And hope is a posture which is necessary only so long as the world awaits its rectification according to the purposes and promise of God.

Hope measures the distance between the now and the not yet.Hope is only intelligible amidst hopelessness.

Christian hope, therefore, is far from being the psychological crutch Freud imagined it. The pie-in-the-sky escapism Marx ridiculed is also not Christian hope. The otherworldliness of Christian hope is unintelligible apart from a frank assessment of this world. Hope is not the refusal of reality but the recognition of the difference between what is and what ought to be.

If hope requires both these poles, let’s call them the “present evil age” and the coming Kingdom, then focusing only on the former or the latter, says St. Augustine, will yield the opposite of hope.

Despair.

I thought of Augustine on Monday.

Shortly after seeing the horrific photograph in the New York Times of the Ukrainian mother and her two children killed by mortars as they tried to flee across a bridge, I was planning worship and thumbing through my Bible when I stumbled across a scene at the edge of the Passion. Mary anoints Jesus with perfume. Judas sees the price tag still on the bottle. Mary’s lavished roughly $45,000 worth of nard on the same Jesus who didn’t have a single coin in his pocket when the begrudgers asked him about paying taxes. Judas explodes, rightly we think— if we’re honest, that a whole hell of a lot of poor folks could’ve been fed with such a sum.

But Jesus surprises.

He offends Judas with his pessimistic reply, “The poor you will always have with you. You will not always have me.”

The offense abides.

Try hearing Jesus say something equivalent, The war wounded you will always have with you. You will not always have me.

The philosopher Charles Taylor notes that modernity constructed a very different moral universe from the one in which Judas or Jesus of Nazareth lived. Without the conviction of a world to come— and with it, God’s coming justice— modernity focused on this world and create an “extraordinary moral culture,” one with ever-higher demands for concern for all other humans. Mass media, the interconnectedness of the World Wide Web, and social media have only exacerbated modernity’s effects, leading us to feel genuinely concerned about and responsible for all sorts of people near and far. While we’re not necessarily better people than our forebears, our perceived moral obligation is wider than it’s ever been in human history.

And this is largely good. You should give a righteous shit about that family in the Times photograph. Our sense of moral obligation, however, is complicated by another construction of modernity; namely, the (often unexamined) assumption that suffering is an accidental fact about human life, not inevitable, but able to be eliminated or fixed. Charles Matthewes argues in the Republic of Grace that modernity’s moral revolution:

“is at once its strength and tragic flaw. It encourages in us awesome moral energies, but ties those energies to the conviction our exertions will one day be rewarded with the elimination of suffering and evil…if we root our moral energies in the conviction that they can be eliminated, the inevitable discovery that they cannot results in endless vexation and, perhaps, a deepening resentment of and cynicism about those very moral energies.”

Augustine, who knew firsthand the stubborn reality of war, understood that our compassion for this world could only be sustained by the promise of a better world to come.

We need hope.

While modernity can construct an extraordinary moral culture, that moral culture cannot sustain itself without a transcendent hope. And our moral culture cannot create that hope. By definition, it must come from outside us.

We need hope from beyond what Charles Taylor calls the immanent frame. We need God. Otherwise, says Augustine, we’ll attempt to gild our moral endeavors into an idol, a world without war or racism, for example, or a world without suffering. Such an idol will only leave us exhausted from our endeavors, self-righteous towards those who are not so engaged, or disillusioned that the need never ends.

Hope— Christian hope— hope that measures the distance between the now and the not yet invites us to serve our neighbors, near and far, by relieving us of the illusion that, if we but try hard enough, one day we will not have the poor with us.

Thus our hope is also a kind of mercy, acknowledging that “not yet” means “not ever” in this mean time until Christ comes back. We’re free, in other words, of the burden of being God. We can instead care for his creatures as fellow (finite) creatures of God.

Sadly, we will always have the poor and the wounded with us. But one day, Christ will come again to set all things right. So in the meantime we do what we can.

I have exciting news to share: You can now read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack app for iPhone.

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the appWith the app, you’ll have a dedicated Inbox for my Substack and any others you subscribe to. New posts will never get lost in your email filters, or stuck in spam. Longer posts will never cut-off by your email app. Comments and rich media will all work seamlessly. Overall, it’s a big upgrade to the reading experience.

The Substack app is currently available for iOS. If you don’t have an Apple device, you can join the Android waitlist here.

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers