The Lay of the (Holy) Land

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

When he was a child, every Palm Sunday Karl Barth would rush to the window of his family’s church and press his face against the glass in order to spy a glimpse of Jesus trotting down the streets of Basel, Switzerland atop a donkey, cloaks and palm leaves laid on the path before him and shouts of “Hosanna” hanging in the air. The stories of the Gospel so captured the future theologian that he heard them as present-tense announcements of news. The narrative illuminated the land around him as though the two were necessary for a proper proclamation. Similarly, Christians have long referred to the Holy Land as an interpretative companion to the Gospel, the place of Jesus’s preaching of the Kingdom as a necessary hermeneutic to a right apprehension of it.

I’ve always felt reluctant to travel to Israel. As a preacher, I’ve been wary of Christian kitsch and tourist tchotchke ruining the scenes the evangelists in my mind’s eye. If you can hardly travel anywhere in Virginia without a convenience store or Cracker Barrel hawking a three-cornered hat, I figured, Israel must be replete with Jesus Junk and Lego editions of Heroes of the Torah.

I was wrong.

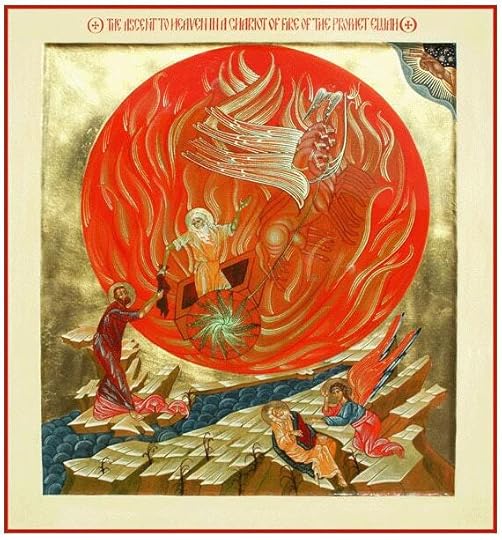

Thus far, I’ve seen very few trinkets and, only three days into my journey, I’ve quickly realized what the Church Fathers meant by calling the Holy Land the Fifth Gospel. For example, I stood on the grounds of the little church that sits at the top of Mount Carmel. In case you’ve forgotten your Sunday School, Mount Carmel is the site where King Ahab summons the prophet Elijah as well as the 450 prophets of Baal. It’s like a Top Chef Finalist Competition but with higher stakes. King Ahab’s men butcher some bulls and bring out fire wood for the showdown between the barren deities of Canaan and the God who heard his people’s cries and raised them from captivity in Egypt.

The contest is simple.

“The God who answers by fire,” Elijah declares, “that god is God.” The hundreds of false prophets— be warned: I’m sure they were sincere in their false piety— pray to their barren deities from morning to noon with the sorts of loud cries and outsized affectations you might see on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. Nada. So after lunch, Elijah has his seminary interns pour four jars of water all over the wood of his altars dedicated to Yahweh. For added measure, Elijah has them pour water a second time and then a third. Finally, Elijah doesn’t so much as raising his voice. He prays, simply, “O Lord, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, let it be known this day that you are God in Israel, and that I am your servant, and that I have done all these things at your word. Answer me, O Lord, answer me, that this people may know that you, O Lord, are God, and that you have turned their hearts back.” And fire falls from the sky and consumes the entirety of Elijah’s offering.

A feature of the story we’ve successfully excised from our Sunday School memories is that, having defeated the prophets of Baal without raising a finger, Elijah drags them one-by-one down the mount to the Kishon wadi where he takes up the sword and lops off their heads.

I’ve preached this text several times over the course of twenty some years. It is to preachers what a Gary Clark Jr. tune is to guitarists. It’s a big, thick text to better yourself as a preacher precisely by failing to master it. But I lacked the young Barth’s felt connection to the land as a necessary hermeneutical lens.

It never occurred to me until now that Mount Carmel, the wadi Kishon, and the prophet who takes up the sword with the vengeance of the Lord upon him all take place straightaway across the valley from the gentle, rounded slopes of Mount Tabor.

It’s barely a cross-country run from the one mountain to the other mountain, each plainly visible to the other even on a cloudy day.

Mount Tabor is also known as the Mount of Transfiguration. It’s the place where Jesus, like the Burning Bush before him, is afire with the glory of God but not consumed by it. Elijah and Moses, representing the Prophets and the Law, appear alongside the beautified Son as the Father doubles down on his baptismal declaration, “This is my beloved Son— listen to him!” Preachers often chide Peter because he responds to the transfiguration by wanting to preserve the epiphany and remain on the mountaintop, “Let us make three booths, one for each of you, and abide here with you.” The hackneyed preacher’s trope suggests that Peter, who’d foolishly attempted to defy gravity on the lake, once again fails to understand. The life of a follower of Jesus is back down in the valley, Peter, with our sleeves rolled up to serve a creation still groaning in labor pains.

Yesterday I stood on top of Mt. Carmel and looked down at the wadi that winds its way from the site of Elijah’s slaughter to the Mount of Transfiguration and I thought that perhaps Peter understood far better than we preachers give him credit.

Perhaps Peter understood that in this Jesus of Nazareth God’s People finally had a prophet better than Elijah.

It’s only after being here and seeing the joggable distance between Mt. Carmel and Mt. Tabor that I understood the snatch of conversation Jesus exchanges with James and John, whom Jesus calls “sons of thunder.” They’re on their way to Jerusalem by way of a village of Samaritans, traditional enemies of the Jews. When the Samaritans, as expected, do not welcome Jesus into their homes, the sons of thunder ask, “Lord, do You want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?’”

Elijah had done it.

Why don’t you do it and be done with them, Jesus?

“Jesus turned and rebuked James and John, and said, “You do not know what kind of spirit you are of; for the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”

Share Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli

The sons of thunder didn’t yet know what the one whom Jesus calls the rock had already intuited by looking across the valley at Elijah’s mountain and the wadi that once had run red with blood and hearing the Father insist that Jesus— NOT Elijah— was the prophet to be heeded.

Stanley Hauerwas says we cannot know the Kingdom unless our eyes are opened to see it. Being here, I think Stanley’s point applies to the land as much as it pertains to any spiritual perception.

The particular geography of Jesus’s of ministry makes unavoidable the lesson his cross and empty tomb make universal.

More than a prophet, Jesus does not take up the sword. He suffers it.

As a crucified Christ, Jesus does not call down on sinners the fire of God’s wrath. He’s consumed by it.

As God in the flesh, Jesus does not destroy his enemies. While they were yet his enemies, Christ dies for the ungodly.

It’s the message of the cross, sure. It’s the Gospel in nuce, no doubt. But, long before he gets to Jerusalem, it’s a lesson woven into the lay of the land. Peter was right on Mount Tabor. In Christ, we have been given not a prophet who abides by our sense of justice. We have been given a still greater One in whom it is good and right for us to abide.

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Read Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli in the new Substack appNow available for iOSGet the app

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers