If the Devil Showed Up, I’d have said, “Yes”

Thanks for reading Tamed Cynic by Jason Micheli ! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

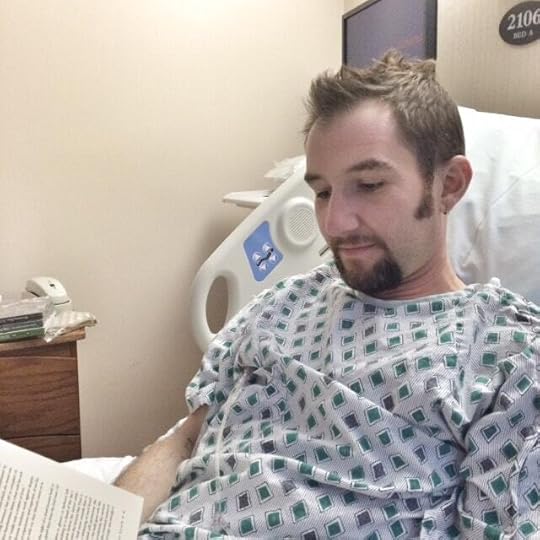

Several years ago now, after the pre-scans of my body and pre-hydrations and pre- medications, around 1:30 a.m. my nurse on the cancer ward started my first six-hour IV drip of Rituxan, a poison normally considered safe only for Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) patients who are “young and fit.”

“‘Young and fit’ minus the, you know, stage 4/5 cancer all over my body,” I muttered to my mom, who was riding shotgun with me that first night.

Not knowing what to anticipate from the Rituxan, I lay there in bed that first night, clutching the sheets in the quiet. Nothing.

I was fine. I couldn’t feel or notice a thing.

By 2 a.m., I was smiling in the dark. At myself. Thinking to myself, Paul Simon’s got it all wrong. The darkness isn’t silent; it’s filled with sound of my awesomeness.

“Who are these sissies,” I wondered to mother, “who complained about how hard chemo is on the body?”

I’m like the Charles Bronson of chemo. I’m like Jules from the lymphoma outtakes of Pulp Fiction. I’m a mushroom-cloud-laying mofo. I’m like the Taken 1, 2, and 3 Liam Neeson of chemo- “weaponry”; I have a very particular set of skills, and kicking cancer’s ass is one of them.

I seriously thought that to myself.

And then BAM. At 3 a.m., ninety minutes in, with no warning at all, I went from zero to sixty in one second flat. My whole body started to convulse, violently, head to toe, shaking my bed and every machine attached to it, splitting open my stomach incision and making my insides feel like they were now my outsides. It was like an epileptic seizure—but one that started not in my brain, but in this dry-ice cold deep down inside my bone marrow.

It was 3 a.m., chemo battle number one, and what did the Charles Bronson of cancer do?

That’s right, he shouted—not really shouted, because the words wouldn’t really come out of his quaking mouth—gurgled for his mommy, who was snoring on the pullout bed in his room. My mom fetched the nurse, who upon entering, blithely responded with “Oh, yes, that’s one of the reactions to the Rituxan,” as she started layering a dozen warmed blankets on me to zero effect.

Reaction? Hives from bad Cabernet is a reaction. A rash from a bug bite is a reaction.

Except actually, I wasn’t thinking. At all. I couldn’t think past the pain the convulsions had erupted all over me. I couldn’t have made heads or tails of a Two and a Half Men episode or a Sarah Palin speech, so bone-wracking was the pain. It was blinding, consuming. A first for me.

It lasted about an hour.

And if you had offered me in any of those sixty minutes anything to make it stop, to take it away, to turn back time—to any of my worst precancer moments—then, damn the torpedoes, I would’ve taken you up on it.

No.

That’s not true.

I love my life. I cherish my wife. And I’m gunning to see my little guys grow up.

I would’ve stuck it out for them, no matter what you offered me.

But, brass tacks confession time: If you told me then the next 150 days would be exactly like that hour and if you could promise me to make it all go away, then I wouldn’t say yes because of the reasons immediately cited above. I don’t think, but

I’d be tempted. And that means I could have said say yes.

A couple of days before I started chemo, my church marked the beginning of Lent by marking their foreheads with ashen crosses, recalling their mortality with the words “From dust you came, and to dust you shall return,” and reading the story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness.

Whenever we picture Jesus tempted by the devil in the wilderness, we usually imagine it in unsubtle comic book lines and hues, with a bad guy readily identifiable as “Satan” and three temptations to which Jesus readily gives the correct answers as though he’s been raised by a Galilean Tiger Mom.

The evangelists tell the story with such Hollywood haste that they effectively turn Jesus of Nazareth into a spiritual prodigy who doesn’t scratch his head over the best way forward.

But not only is such convictional clarity not temptation, it dilutes Jesus into someone less than fully human. It makes Jesus not as human as you or me. I know the Gospels say Jesus was tempted by the devil in the desert, and I believe it. I just think those temptations came to Jesus in exactly the same sorts of unseen, uncertain, ambiguous—human—ways they come to us.

I mean, it’s a no-brainer if you’re posed questions by a guy with horns and a pitchfork. The right answers are obvious; that’s not temptation. Which is to say, I take it as an article of faith that it was a real, live possibility for Jesus to have answered otherwise when the tempter proffered his questions in the desert. Just take another look; the brevity of the stories aside, Jesus spends forty days tackling just three queries. That’s a baker’s dozen days per temptation. There’s more to the story than the story.

We tend to think of faith as something unchanging and immovable, which we can turn to when times get tough or tempting. “He is our Rock,” the praise song repeats ad nauseam. Faith is our North Star, our inner compass, our firm foundation.

But I don’t think so, not since that first night of chemo.

If Jesus is at least as human as you or me, then one of the things Jesus takes on in the incarnation is the contingency of life—not knowing what will drop with the next shoe, what crappy news is a day away, or what will be the best way to deal with it. If Jesus is at least as human as you or me, then his humanity is shot through with the very uncertainty that so often makes our lives seem like a crapshoot. And that means faith isn’t like a rock or a firm, immovable foundation. It means faith is as ever changing as everything else in our lives.

Faith entails change because it’s faith that unfolds in the world God has given us. Faith requires change even, for faith depends upon the always-changing life in which it is lived. In the same way that love and marriage and children and a career change you—and thus your faith—so do pain and dread and fear and despair and temptation change you—and thus your faith.

What makes temptation in the face of faith real is the real possibility of losing the faith you had. The real possibility of failing at your faith or—here’s what you discover is truly scary—finding that your faith fails you when you most need it.

If there’s a silver lining there (and cancer has made me a seeker of silver linings), it’s that “faith is strongest,” as poet Christian Wiman posits, “where the possibility of doubt is greatest.”

“One day down,” I told my mom the next morning, “149 or so more to go.”

I didn’t add how that was nearly four times longer than Jesus was stuck in his own wilderness.

From: Cancer is Funny

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers