Jason Micheli's Blog, page 144

March 22, 2017

God Did Not Kill Jesus Because God is Trinity

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

You can find all the previous posts here.

III. The Son

30. Does Trinity Mean We Worship 3 Gods?

Yes.

If you think of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as ‘persons’ of the Trinity.

But the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit are not persons; they are relations.

A “person” is an independent, individual subject. Neither the Son nor the Spirit are independent from the Father. None of the three are discrete subjects so as to be individualized from one another. Each of the three is unintelligible apart from the relationship we call Trinity.

The Son is the self-conception of the Father. The Holy Spirit is the delight the Father takes in relationship with the Son. Recall, the Father does not have a relationship with the Son nor vice versa. Rather they ARE relationship.

Not only do we not worship 3 Gods, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit possess only 1 single, unified will.

In other words, Trinity helps us read correctly the story of incarnation, cross, and resurrection as the outworking of the single, unified will of God; that is, Trinity prevents us from ever supposing the Father’s and the Son’s wills are posed against one another in the Son’s sacrifice upon the cross. We call God Trinity to remember the Father did not demand another’s death nor did the Son offer his life to anyone else in our stead. Only because God is Trinity, because Father, Son, and Spirit are relations not persons, can we profess the Judged is none other than the Judge.

Father, Son, and Spirit do not differ in any way. In each case, what they are is God and at no point in their internal life or their external work are they anything but fully God. The Father has no attributes or features the Son lacks; the Spirit has no attributes or features the Father lacks.

Because they are relations not persons, they have a single will:

Whatever we say of the Son is true of the Father.

Whatever we say of the Father is true of the Son.

And whatever we say of the Spirit is true of both.

“For I have come down from heaven to do my Father’s will.” – John 6.38

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 21, 2017

My Lazarus Perspective etc.

Book tour pimping continues apace.

Book tour pimping continues apace.

Recently, I was on NPR’s Things Not Seen with David Dault. Check out the interview here.

Also, I was on the Christian Humanist Podcast. Check that one out here.

I’ll be at the Virginia Festival of the Book this weekend in Charlottesville and preaching at Wesley Memorial UMC there on Sunday am. Be there.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 20, 2017

Lent 4A- Stanley Hauerwas: Bedroom Oils & Hipster Jesus

This episode of Strangely Warmed closes out our lectionary conversation with Stan the Man.

This episode of Strangely Warmed closes out our lectionary conversation with Stan the Man.

Taylor and I riff on oils and anointing, fixed-gear bikes, and Jesus praying Psalm 23 (‘prepares a table before me in the presence of my enemies’) during Holy Week. Stan reads to us from one of his sermons on this week’s lectionary texts and clearly enjoys his own jokes!

Eric Hall will join us next week to close out Lent, Tony Jones will dish with us on Holy Week, and we have Brian Zahnd teed up for Eastertide.

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 17, 2017

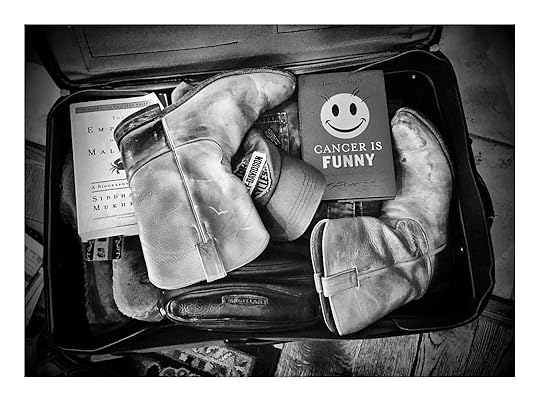

Englewood Review of Books: Cancer is Funny

Here’s Alex Joyner’s review of my book in the Englewood Review of Books:

Here’s Alex Joyner’s review of my book in the Englewood Review of Books:

Most of what Jason Micheli has to tell you about cancer, you don’t want to know. The title of his new book, Cancer is Funny: Keeping Faith in Stage-Serious Cancer, may hint at optimistic self-help with some humorous anecdotes laced throughout, but cancer is not ‘ha-ha’ funny. Micheli is glad to tell you, in harrowing detail, that “cancer f@#$ing sucks.” (ix) This book is as raw as the sores running down his esophagus in mid-stage chemo. Yeah, there’s a lot here you don’t want to know, but it’s a story told by one of the most honest and profane pastors you’ll ever meet and along the way he spins out the heart of a battle-tested theology that is clear-eyed, unsentimental, and fully alive. Plus, too, he’s funny.

I can only imagine the debates that Micheli, a United Methodist pastor in northern Virginia, had with his editors in getting this book to press. Despite the striking cover art (a smiley face sporting chemo hair on a bright red background), the prospect of selling a book about cancer, especially one that refuses to sugar-coat anything, must have been daunting. Micheli’s edgy writing style certainly swims in the zeitgeist of his 30-something generation, but then again, most of them are not facing the rare, aggressive cancer that Micheli faced, (mantle cell lymphoma – a type that usually affects much older men). A tale like this has to be carried along on the vitality and voice of its author and we certainly get to meet such a voice in this book.

A few years ago, Barbara Ehrenreich used her own journey through cancer as a lens for her book, Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking is Undermining America. Ehrenreich shares Micheli’s disdain for the Hallmark language and easy positivity we throw at cancer. She wrote, “Breast cancer…did not make me prettier or stronger, more feminine or spiritual. What it gave me, if you want to call this a ‘gift’, was a very personal, agonising encounter with an ideological force in American culture that I had not been aware of before – one that encourages us to deny reality, submit cheerfully to misfortune and blame only ourselves for our fate.”

Micheli chafes at this force, too, but he has a different vocabulary for understanding it—one that is shaped by his own theological journey with the likes of Karl Barth, David Bentley Hart, and Stanley Hauerwas. Through it all, he is placing his own suffering within a thorough-going Christological framework. In doing this he pushes back against the notions that God is only visibly present when cancer is being combatted and defeated. “As Stanley Hauerwas points out, the assumption behind what theologians call theodicy is that God’s primary attribute is power… implicit in this assumption is another one: because humans were made in God’s image, power primarily defines us as well.… Christians, however, believe God’s primary attribute is suffering love, not power–-passio, not potens.”(162)

In a better world, these insights should be the thing that brings people to this book. Micheli uncorks some great laugh lines. (One of my favorites: “Whenever we picture Jesus tempted by the devil in the wilderness, we usually imagine it in unsubtle comic book lines and hues, with a bad guy readily identifiable as ‘Satan’ and three temptations to which Jesus readily gives the correct answers as though he’s been raised by a Galilean Tiger Mom.”(65)) But it is the way that his theological formation illuminates his suffering (and vice-versa) that give this book enduring value. When he says, “They then both bent me in impossible positions as though I were a yoga instructor or Anthony Weiner on the phone”(7), I think/hope that the Weiner reference will be incomprehensible a few years down the road. But when he writes, “Cancer doesn’t lead you to ask, ‘Why me, God?’ Cancer leads you to wonder why God, whom we call Light, can’t seem to enter or act in our world without casting shadows”(88), well, then I think we’re on to something that will last.

The humanity of Micheli’s writing also shines through here. He is the father of two young children and his relationship with them and his wife is handled with a good, light touch. The poignant moments, and there are many, are not cheap.

Some readers, especially those who are used to the tame and tidy spirituality of much popular Christian writing, will be surprised by Micheli’s unvarnished profanity and his willingness to bare his carnal thoughts in these pages along with his poisoned, prodded body. I’ll admit that I flinched for him at points, wondering if he needed to be that confessional. But good memoirists know that a concern for appearances is deadly to the form.

Micheli is a spiritual heir to Mary Karr, whose The Liar’s Club is the seminal memoir of this era. In Karr’s The Art of Memoir, she talks about the hard work that memoirists must do in order to maintain an authentic voice. “For most, knowing the truth matters more than how they come off telling it.” And this means digging down beneath the pretty.

Micheli has a poetic gear, and it comes through in this book. But he values the rawness he has experienced. His rationale for sharing it comes late in the book and it, like all of the book, is grounded in his theology: “Thinking our holy obligation is to give God the glory, do we, in fact, rob God of glory, hugging tightly to the first draft of our testimony and offering up instead sanitized, sterilized, red-penned spiritualized jargon that intersects only tangentially with our real lives, because–-we think–-God’s not up to the challenge of our pain or unholy emotions?” (192)

This is a searing book. The cumulative effect of reading it through is, perhaps, like rounds of chemo, drawing us deeper into the pain. But we do get a glimpse of the joy Micheli holds onto. Not ‘ha ha’ joy. But life for sure. It’s a journey worth taking with him.

——–

Alex Joyner is an author and United Methodist pastor on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. He is the author, most recently, of A Space for Peace in the Holy Land: Listening to Modern Israel & Palestine [Englewood Review, 2014]. He blogs at AlexJoyner.com.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 16, 2017

Episode 84 – Daniel Kirk: A Man Attested by God

Is Jesus the Son of Man who comes from God as only God can come from God? Or Jesus is merely a man attested by God?

Is Jesus the Son of Man who comes from God as only God can come from God? Or Jesus is merely a man attested by God?

“Identification with God is not tantamount to identification as God”

So argues New Testament scholar Daniel Kirk argues in his new book A Man Attested by God: The Human Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels. Identification with God, Daniel argues, is not tantamount to identification as God.

We talked with Daniel a few months ago and the audio got lost in the thicket of files to be edited. Here it is. Enjoy.

Coming up, we’ve got conversations for you with David Bentley Hart, Richard Rohr as well as Robert Jenson. And don’t forget to check out our lectionary-based offshoot of the podcast. We’re calling it Strangely Warmed.

Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

We’re breaking the 1K individual downloaders per episode mark.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website.

If you’re getting this by email, here’s the permanent link to the episode.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 14, 2017

If We’re Justified By Faith, Then Isn’t Faith a Work?

I noticed the upcoming lectionary epistle for this Sunday is Romans 5.1-11 which begins thus:

I noticed the upcoming lectionary epistle for this Sunday is Romans 5.1-11 which begins thus:

“Therefore, since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God…”

The question is- or should be- by whose faith are we justified? Ours? Or Christ’s? By faith here in Romans 5 is an echo of an earlier theme Paul picks up from Romans 3:

“Therefore by the deeds of the law no flesh will be justified in His sight, for by the law is the knowledge of sin. But now the righteousness of God apart from the law is revealed, being witnessed by the Law and the Prophets, even the righteousness of God, through faith in Jesus Christ, to all and on all who believe. For there is no difference; for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” Romans 3:20-23.

Sometimes a preposition can make all the difference.

I remember my first theology course as a freshman undergraduate, Elements of Christian Thought, with Euene Rogers. I’d just become a Christian as a Junior in High School and was only beginning to become acquainted with the actual content of our faith. The topic one week was Justification & Salvation, and I remember another student asking the TA:

‘If Christians believe we’re justified by faith in Christ, then what about people like me who don’t have faith, who’d maybe like to have faith but can’t seem to find it?

Is it our fault then if we’re not saved? Why faith is essential why is it so hard?

That seems like a pretty limited God.’

It hit me then and still does as a very good question. Not only does it make essential something that is sincerely elusive for many people, it also turns faith into a kind of work- the very opposite of Paul’s point- in that we’re saved by our ability to believe.

Justification by (our) faith (in) Christ turns faith into the very thing Paul railed against: our work.

That is, religion

The irony of the historic Faith vs. Works, Gospel vs. Law debate among Christians, however, is that the very idea of justification coming through faith in Christ is premised on a bad translation of scripture.

Almost everywhere, other than the King James, that is written in English it is a wrong translation. In Greek, the actual wording is that we’re justified “through the faith OF Jesus Christ.”

Grammar Lesson:

It is a possessive or genitive phrase. Now a genitive means that this phrase can be interpreted as either subjective or objective. In other words, it is like the phrase, the Love of God. That is either our love for God, or the love that God has. In one case it is objective (love for God), in the other subjective (God is the subject) and it describes the love that belongs to God, or God’s love.

In Greek, the faith of Jesus Christ is also a subjective genitive, but has been interpreted as an objective in almost every translation.

Why is this important?

Because it is not our faith in Jesus which justifies us, but the faith of Jesus Christ in us which justifies us.

Faith isn’t a work.

Isn’t our work at least.

The faith that saves us and justifies us is the obedience of Christ.

In other words, it is his faith at work in us and in our hearts which produces righteousness and the God kind of life. This explains why faith is a gift and why we are saved through faith by grace and not as a work of our own. It is not our faith which justifies, but the faith of Jesus given to us, which resides in us.

The good news is, it isn’t my faith that matters. It is the faith OF Jesus Christ given to me, that when God regards you or me God isn’t measuring our feeble attempts at faithfulness. In other words, when God looks upon us God chooses not to see us but to see Jesus.

Follow @cmsvoteup

Wrath Reconsidered: Christianity Isn’t Just About Forgiveness

This upcoming Sunday’s lectionary passage from Romans 5 includes verse 9:

This upcoming Sunday’s lectionary passage from Romans 5 includes verse 9:

“Much more surely then, now that we have been justified by his blood, will we be saved through him from the wrath of God.”

Like many upper middle class mainline Protestants, which is to say white Christians, I’ve long taken issue with the concept of divine wrath, believing it to conflict with the God whose most determinative attribute is Goodness itself. Whenever I’ve pondered the possibility of God’s anger I’ve invariably thought about it directed at me. I’m no saint, sure, but I’m no great sinner either. The notion that God’s wrath could be fixed upon me made God seem loathsome to me, a god not God.

We commonly suppose that Christianity is primarily about forgiveness. Jesus, after all, told his disciples they were to forgive upwards of 490 times. From the cross Jesus petitioned for the Father’s forgiveness towards us who knew exactly what we were doing. Forgiveness is cemented into the prayer Jesus taught his disciples.

Nonetheless, to reduce the message of Christianity to forgiveness is to ignore what scripture claims transpires upon the cross.

The cross is more properly about God working justice.

The most fulsome meaning of ‘righteousness,’ Fleming Rutledge reminds readers in The Crucifixion, is ‘justice’ understood not only as a noun but as an active, reality-making verb. Though righteousness often sounds to us as a vague spiritual attribute, the original meaning couldn’t be more this-worldly. Justice, don’t forget, is the subject of Isaiah’s foreshadowings of the coming Messiah. Justice is the dominant theme in Mary’s magnificat and justice is the word Jesus chooses to preach for his first sermon in Nazareth.

To mute Christianity into a message about forgiveness is to sever Jesus’ cross from the Old Testament prophets who first anticipated and longed for an apocalyptic invasion from their God.

And it ’s to suggest that on the cross Jesus works something other than how both his mother and he construed his purpose.

Rather than forgiveness, we see on the cross God’s wrath poured out against Sin with a capital S and the upon the systems (Paul would say the Powers) created by Sin. On the correspondence between Sin as injustice and God’s wrath, consider Isaiah’s initial chapter:

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the Lord; I have had enough of burnt-offerings… bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity. Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doing from before my eyes; cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow…

Therefore says the Sovereign, the Lord of hosts, the Mighty One of Israel: Ah, I will pour out my wrath on my enemies, and avenge myself on my foes! I will turn my hand against you…

Christianly speaking, forgiveness is a vapid, meaningless concept apart from justice. The cross is a sign that something in the world is terribly wrong and needs to be put right. The Sin-responsible injustice of the world requires rectification.

Only God can right what’s wrong, and the cross is how God chooses to do it. God pours out himself into Jesus and then, on the cross, God pours out his wrath against Jesus and, in doing so, upon the Sin that unjustly nailed him there.

Summarizing the prophets’ word of divine wrath in light of the cross, Rutledge writes:

‘ Because justice is such a central part of God’s nature, he has declared enmity against every form of injustice. His wrath will come upon those who have exploited the poor and weak; he will not permit his purpose to be subverted.’

Despite the queasiness God’s wrath invokes among mainline and liberal Protestants, it has been a source of hope and empowerment to the oppressed peoples of the world.

The wrath of God is not an artifactual belief to be embarrassed over, it is the always timely good news that the outrage we feel over the world’s injustice is ‘first of all outrage in the heart of God,’ which means wrath is not a contradiction of God’s goodness but is the steadfast outworking of it.

The biblical picture of God’s anger is different from the caricature of a petulant, arbitrary god so often conjured when divine wrath is considered in the abstract. ‘The wrath of God,’ Rutledge writes, ‘is not an emotion that flares up from time to time, as though God had temper tantrums; it is a way of describing his absolute enmity against all wrong and his coming to set matters right.’ Put so and understood rightly, it’s actually the non-angry god who appears morally distasteful, for ‘a non-indignant God would be an accomplice in injustice, deception, and violence.’

Maybe, I can’t help but wonder, we prefer that god, the one who is a passive accomplice to injustice, because, on some subconscious level, that is what we know ourselves to be.

Accomplices to injustice.

Perhaps that is what is truly threatening to so many of us about a wrathful God; we know that the bible’s ire is fixed not so much on the hands-on oppressors as it is against the indifference of the masses.

As Rutledge points out:

’ ,,,in the bible, the idolatry and negligence of groups en masse receive most of the attention, from Amos’ withering depiction of rich suburban housewives (Amos 4.1) to Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem (Luke 13.34) to James’ rebuke of an insensitive local congregation (James 2.2-8).

As Brett Dennen puts it in his song, ‘Ain’t No Reason,’ slavery is stitched into every fiber of our clothes. We’re implicated in the world’s injustice even if we like to think ourselves not guilty of it. Rutledge believes this explains why so much of popular Christianity in America projects a distorted view of reality; by that, she means sentimental. Our escapist mentality protects us not just from the unendurable aspects of life in the world but also from the burden of any responsibility for them.

Such sentimentality, however popular and apparently harmless, has its victims. I’m convinced we risk something precious when we jettison God’s wrath from our Christianity. We risk losing our own outrage.

Fleming Rutledge’s The Crucifixion might’ve convinced all on its own:

‘ If, when we see an injustice, our blood does not boil at some point, we have not yet understood the depths of God. It depends on what outrages us. To be outraged on behalf of oneself or one’s own group alone is to be human, but it is not to participate in Christ.

To be outraged and to take action on behalf of the voiceless and oppressed, however, is to do the work of God.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 13, 2017

Lent 3A – Stanley Hauerwas: “He Told Me Everything About Me”

Why would we not go to Duke just to talk with Stanley Hauerwas? Even though Stanley doesn’t know what a podcast is, he welcomed us to his 3rd floor office for a candid sitdown.

Why would we not go to Duke just to talk with Stanley Hauerwas? Even though Stanley doesn’t know what a podcast is, he welcomed us to his 3rd floor office for a candid sitdown.

Not only did Dr. Hauerwas give us books from his vast collection, he even offered us some his classic Hauerwas humor. In this conversation, Stanley reflects on the Gospel lection for the third Sunday of Lent, Jesus’ quenching conversation with the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s Well.

The texts for Lent 3 are:

Exodus 17:1-7

Psalm 95

Romans 5:1-11

John 4:5-42

Stanley Hauerwas will be back for the next few week’s of Lent, Eric Hall will join us to close out Lent, Tony Jones will dish with us on Holy Week, and we have Brian Zahnd teed up for Eastertide.

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 10, 2017

Episode 84: Ched Myers – Binding the Strong Man

Boom.

All the more reason for you to check out our latest guest. Ched Myers’ commentary on the Gospel of Mark, Binding the Strong Man, is one of the most influential books I read in seminary.

Crackers and Grape Juice got to interview Ched Myers to discuss what solidarity and resistance look like in the age of Trump and social media.

Ched is an activist theologian, biblical scholar, popular educator, author, organizer and advocate who has for 35 years been challenging and supporting Christians to engage in peace and justice work and radical discipleship.

Ched is an activist theologian, biblical scholar, popular educator, author, organizer and advocate who has for 35 years been challenging and supporting Christians to engage in peace and justice work and radical discipleship.

Coming up, we’ve got conversations for you with David Bentley Hart, Richard Rohr as well as Robert Jenson. And don’t forget to check out our lectionary-based offshoot of the podcast. We’re calling it Strangely Warmed.

Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

We’re breaking the 1K individual downloaders per episode mark.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website.

If you’re getting this by email, here’s the permanent link to the episode.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 9, 2017

Covert Christians

I take an attribute of strong preaching to be the ability to take a cliche or convention and upend it. Here, my Jedi Master, Robert Dykstra, takes John 3 and counterintuitively makes Nicodemus the hero of the story. In a world of 3.16 eyeblack and politically compromised evangelicals, this is a fresh word from this Sunday’s lectionary Gospel:

A Sermon Preached at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church

New York, New York

Sunday, May 28, 2006

by Robert Dykstra

John 3:1-10, John 19:38-42

I thought her invitation a bit presumptuous, a bit out of place, though it was benign enough as invitations go. It was an altar call, really, and I havenít anything much against altar calls, though I donít ever remember issuing one myself as a preacher, perhaps for fear of a lack of any response. But this particular altar call seemed a bit unusual, a little presumptuous, a little out of place.

The place was Miller Chapel on the Princeton Seminary campus, back in my days as a student there. Her invitation came at one of the seminaryís brief weekday morning worship services. The preacher on that particular day was a guest minister from outside the seminary community, a distinguished and eloquent African-American woman ñ I canít even remember her name now. But what I do remember is that at the end of her lively and powerful sermon ñ the way of African American sermons and far more compelling than our usual white-boy-student-sermon fare ñ this preacher issued an altar call to those of us in the congregation. She asked those who wished to commit their lives to Christ to come forward into the chancel for a prayer.

Well, I found this invitation a little odd, a little out of place, a little presumptuous of her. No one can enroll as a student or be hired on as a faculty member at Princeton Seminary without claiming to be a Christian, though I canít fully guarantee that Jesus himself would claim us all as such. You have to say youíre a Christian to get admitted to Princeton Seminary, so whatís up with this preacher issuing an altar call at a place like this, in a place like Miller Chapel?

I thought to myself, No one is going to go forward to commit their lives to Jesus at Princeton Seminary.

I was dead wrong, of course. Of the perhaps hundred or so students and faculty in the chapel that day, a huge throng of worshipers made their way to the front of the sanctuary. In fact, when the procession ended, I looked around and noticed that there were maybe only four or five of us still seated in our pews. The preacher herself looked out on us pathetic holdouts and noticed it, too. So she said straight to our faces, ìYou folks still sitting out there might as well come on up here, too.î

Now it was I, of course, who was feeling a little presumptuous, or, at least, a little conspicuous. Who did I think I was to imagine that I didnít need to commit my life to Jesus, especially when everyone else in that room seemed to think that they themselves did? No matter that, as far as I knew, Iíd been committed to Jesus as long as I could remember. I recall as a boy still in my booster seat asking my parents how God could be everywhere if we couldnít see God ñ asking questions like that and loving how they would reply: God was inside us, they might say; or God is Spirit, they might say.

I remember as a sixth-grader on the cusp of adolescence attending a Presbyterian summer church camp ñ my first time away from home alone for a whole week, a time full of excitement ñ loving every minute, falling in love perhaps for the first time not only with another camper, but fully, knowingly, with Jesus, feeling him in my heart, openly committing my life to him, praying to him, singing songs to him.

As a high school boy I was allowed to become the church organist of our little congregation, and I took this responsibility very seriously, practicing hymns from the same green hymn book you use here at Fifth Avenue, sometimes late into the night all alone in the darkened sanctuary, a room tiny by this sanctuaryís standard but that seemed voluminous to me at that age ñ alone in the dark, the little light on the organ the only one burning. And I felt warm and secure and so at home in the quiet darkness of Godís house. And I still feel that way today, perhaps most at home of any place I could be in a sanctuary like this, especially if all alone in it, especially at night with one light burning.

So in chapel as a seminary student that day, I felt Iíd been committed to Jesus for a long time. But I knew what I had to do, so at the preacherís bidding to us holdouts still in the pews, I slunk up out of my seat, feeling a bit chastised, and made my way with the other four or so of my less-than-devout comrades to pray with everyone else there in the chancel. But I knew by then that I was a little more reluctant to be born again this time after having been born so many times before.

*******

Thereís a part of me that admires the courage of a preacherís altar call to seminarians. Thereís something exactly right about that invitation. But I think itís also true that, as Iíve grown older, Iíve grown even more uneasy than I was as a student in chapel that day with the kind of public declarations of Christian faith that have grown increasingly familiar and have become not a little divisive in our churches and in our nation today. I get nervous about all those Christians who borrow the ìborn againî language from this very passage in John 3 ñ the chapter of the Bible that contains its most comforting verse, ìFor God so loved the world that he gave his only Son…î ñ but Christians who wear that ìborn againî language as a badge of honor, who use this language to fashion a kind of litmus test or entrance exam into Christian faith, into true discipleship, use it therefore as an instrument of exclusion rather than of grace. Thereís part of me that wishes I had resisted the preacherís second invitation that day to the four of us still remaining in our pews, wishes I had stayed put and prayed by myself there where I was sitting. That would have been more the Christian I now want to be.

I think Iím a born-again Christian going increasingly undercover, becoming increasingly private, increasingly stealthy about my faith. Iím becoming more like Nicodemus, a man who knows that thereís great power and great risk in meeting Jesus, a man who does not take lightly such an encounter with him, who knows thereís a lot at stake. I think Iím someone who now prefers to talk with Jesus in the dark of night, in the middle of the night, as when a boy in that empty church sanctuary with just one lamp burning.

*******

Nicodemusí story, of course, moves in just the opposite direction. His moves from meeting Jesus first in the dark ñ Nick at Night ñ to, by the end of Jesusí life, embracing Jesusí body in broad daylight. You see, Nicodemus shows up several times in Johnís gospel, each time appearing more bold, more public, more decisive about following Jesus, about being seen as his disciple, as if Jesusí lesson that first night about his needing to be born again, born from above, really took hold in his life, really sank in. If my story begins with a public love for Jesus in the daylight to increasingly private encounters with him at night, Nicodemusí story moves from a shadowy encounter with Jesus at night to a powerful declaration of his love for him in the light of day. It is Nicodemus, after all, a Pharisee and leader of the Jews, a member of the Sanhedrin, the elite Jewish ruling council just 70 members strong, the council that proved finally to be Jesusí undoing, his death ñ this Nicodemus is the man who, with the help of his friend Joseph of Arimathea and at great personal risk, embalms Jesusí body after his death, and he offers this painful and tender declaration of love, this intimate final gift to his friend, no longer under cover of darkness.

*******

The nationís most famous undertaker, Thomas Lynch, lives in Milford, Michigan, a small town just north of Detroit, where he buries his friends and neighbors for a living. He also writes amazing books, the reason heís now our nationís most famous undertaker. In his book The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, Lynch tells of preparing the body of his dead friend, Milo Hornsby:

Last Monday morning Milo Hornsby died. Mrs. Hornsby called at 2 a.m. to say that Milo had expired and would I take care of it, as if his condition were like any other that could be renewed or somehow improved upon. At 2 a.m., yanked from my REM sleep, I am thinking, put a quarter into Milo and call me in the morning. But Milo is dead. In a moment, in a twinkling, Milo has slipped irretrievably out of our reach, beyond Mrs. Hornsby and the children, beyond the women at the laundromat he owned, beyond his comrades at the Legion Hall, the Grand Master of the Masonic Lodge, his pastor at First Baptist, beyond the mailman, zoning board, town council, Chamber of Commerce; beyond us all, and any treachery or any kindness we had in mind for him.

Milo is dead….

[In the hospital where he died,] Milo is downstairs, between SHIPPING & RECEIVING and LAUNDRY ROOM, in a stainless-steel drawer, wrapped in white plastic top to toe….

I sign for him and get him out of there….

Back at the funeral home, upstairs in the embalming room, behind a door marked PRIVATE, Milo Hornsby is floating on a porcelain table under florescent lights. Unwrapped, outstretched, Milo is beginning to look a little more like himself ñ eyes wide open, mouth agape, returning to our gravity. I shave him, close his eyes, his mouth. We call this setting the features. These are the features ñ eyes and mouth ñ that will never look the way they would have looked in life when they were always opening, closing, focusing, signaling, telling us something. In death, what they tell us is that they will not be doing anything anymore. The last detail to be managed is Miloís hands ñ one folded over the other, over the umbilicus, in an attitude of ease, of repose, of retirement.

They will not be doing anything anymore, either.

I wash his hands before positioning them [Thomas Lynch, The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, 9-11].

*******

Thatís what Nicodemus will end up doing, though in the light of day, for Jesus. Setting his features. Washing his hands.

Maybe thatís the direction of faith that Jesus prefers, from darkness to light, from stealthy discipleship to public declarations of born-again faith. Maybe thatís what Jesus wants, itís probably what this story in John chapter three is trying to suggest.

But the more that contemporary American Christians insist that everyone become born again and insist too that we all sign on to a prescribed and unyielding roster of accompanying social and political doctrines; the more, so to speak, that weíre pressured to come up to the front of the chapel: the more I want to seek out Jesus in private, at night, undercover, like the early Nicodemus.

The more they press us to become daylight Christians, bumper-sticker Christians, card-carrying, banner-waving Christians, the more I appreciate those stealthy Christians whom I have known and increasingly want to emulate along the way: Christians who are not always so sure of their status before God, seekers who find their encounters with Jesus to be a risky business, who go about their faith without ostentation and perhaps also without complete assurance, in secret, in darkness, undercover, uncertain. The more that born-again Christians fill the airwaves with their certitudes and self-assurance, the more I want to be that Christian with just one lamp burning in the middle of the night.

ìThe wind blows where it chooses,î Jesus tells Nicodemus there in the darkness, ìand you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.î The wind blows where it chooses. God blows where God chooses. We do not control God any more than the wind.

Your being born, my being born, though we can be reasonably sure that we were once born, was not in your or my control, is not something we can take much credit for having done. We had very little to say about our being born the first time, and we would do well to have very little to say now about our being born again, born from above.

It happened once, yes, your birth; it happens sometimes, yes, being born again. But itís not something to spend much time talking about, not if you want to retain any friends. Itís not something in which to take pride or boast. You didnít have that much to do with it. No, better instead just to get on with the business of living, of loving, of serving, of worshiping, of picking up your friends at 2 a.m. and doing for them what needs to be done, however painful or dismal the task. Quiet Christians, steady Christians, stealthy Christians, modest, unassuming, grateful, lunar Christians. Have you known any Christians like that in your life?

*******

A few years ago, as a promising young theology professor at Notre Dame in her early forties, Catherine LaCugna was told by her doctors ìthat there was nothing more that they could do for her and that cancer would kill her within a few months.î At receiving this terrible news, her friend Kathleen Norris writes, LaCugna ìdid not run away to nurse her wounds but continued teaching. She told only a few close friends that she was near death, and she went on living the life she had chosen. She was able to teach until a few days before she died.î

Reflecting on her friendís life and death, Norris says:

I can scarcely imagine what it meant to her students when they found out what she had done, when they considered that they and the dry, underappreciated work of systematic theology that they had been engaged in together meant so much to her. Now, whenever I recite the prayer that ends the churchís liturgical day, ìMay the Lord grant us a peaceful night, and a perfect death,î it is her death that I think of. A perfect death, fully acknowledged and fully realized, offered for others. (Kathleen Norris, ìPerfection,î Christian Century, February 18, 1998: 180).

I think of Norrisí words and of LaCugnaís death from time to time, for they capture the kind of Christian I want to be ñ quiet, steady, faithful, courageous, but, oh, so aware that time is short, the stakes high, the questions we pose to Jesus in the dead of night so very important, with so much hanging in the balance.

Darkness. Risk. Courage. Faithfulness. A stealth Christian. Thatís the kind that, more and more, Iíd like to be.

*******

Remember Thomas Lynch taking care of his friend, Milo Hornsby? Lynch says:

When my wife moved out some years ago, the children stayed here, as did the dirty laundry. It was big news in a small town. There was the gossip and the goodwill that places like this are famous for. And while there was plenty of talk, no one knew exactly what to say to me. They felt helpless, I suppose. So they brought casseroles and beef stews, took the kids out to the movies or canoeing, brought their younger sisters around to visit me. What Milo did was send his laundry van around twice a week for two months, until I found a housekeeper. Milo would pick up five loads in the morning and return them by lunchtime, fresh and folded. I never asked him to do this. I hardly knew him. I had never been in his home or his laundromat. His wife had never known my wife. His children were too old to play with my children.

After my housekeeper was installed, I went to thank Milo and pay the bill. The invoices detailed the number of loads, the washers and the dryers, detergent, bleaches, fabric softeners. I think the total came to sixty dollars. When I asked Milo what the charges were for pick-up and delivery, for stacking and folding and sorting by size, for saving my life and the lives of my children, for keeping us in clean clothes and towels and bed linen, ìNever mind thatî is what Milo said. ìOne hand washes the other,î [is what Milo said].

I place Miloís right hand over his left hand, then try the other way. Then back again. Then I decide that it doesnít matter. One hand washes the other either way [Lynch, 11].

*******

One hand washes the other. Thereís Nicodemus at the end of Johnís gospel washing the hand that once washed his, embalming Jesus.

Nicodemus is not filling the airwaves with endless chatter about his having been born again, though he may well have been thus born. Heís just risking his life, his status, his reputation in this last, quiet, heroic act of love for his friend.

Heís not talking about his birth. Heís living his life. Heís giving his life to the one who so loved the world, to the one who gave his life for him.

Will you?

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers