Jason Micheli's Blog, page 143

April 10, 2017

The Transfiguration

Here’s my sermon from Palm-Passion Sunday on Matthew 26.36-46, Jesus in the Garden in Gethsemane.

Every year during Passover week Jerusalem would be filled with approximately 200,000 Jewish pilgrims. Nearly all of them, like Jesus and his friends and family, would’ve been poor.

Throughout that holy week, these hundreds of thousands of pilgrims would gather at table and temple and they would remember.

They would remember how they’d once suffered bondage under another empire, and how God had heard their outrage and sent someone to save them.

They would remember how God had promised them: “I will be your God and you will be my People.” Always.

They would remember how with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm God had delivered them from a Caesar called Pharaoh.

Passover was a political powder keg so every year Pontius Pilate would do his damnedest to keep Passover in the past tense.

Every year at the beginning of Passover week Pilate would journey from his seaport home in the west to Jerusalem, escorted by a military triumph, a shock-and-awe storm-trooping parade of horses and chariots and troops armed to the teeth and prisoners bound hand and foot and all of it led by imperial banners that dared as much as declared “Caesar is Lord.”

———————————

So when Jesus, at the beginning of that same week, rides into Jerusalem from the opposite direction there could be no mistaking what to expect next.

Deliverance from enemies. Defeat of them. Freedom. Exodus from slavery.

How could there be any mistaking, any confusing, when Jesus chooses to ride into town- on a donkey, exactly the way the prophet Zechariah had foretold that Israel’s King would return to them, triumphant and victorious, before he crushes their enemies.

There could be no mistaking what to expect next.

That’s why they shout ‘Hosanna! Save us!’ and wave palm branches as they do every year for the festival of Sukkoth, another holy day when they recalled their exodus from Egypt and prayed for God to send them a Messiah.

The only reason to shout Hosanna during Passover instead of Sukkoth is if you believed that the Messiah for whom you have prayed has arrived.

There could no mistaking what to expect next.

That’s why they welcome him with the words “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Israel” the very words with which God’s People welcomed Solomon to the Temple.

The same words Israel sang upon Solomon’s enthronement. Solomon, David’s son. Solomon, the King.

There could be no mistake, no confusion, about what to expect next.

Not when he lights the match and tells his followers to give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar (i.e., absolutely nothing).

Not when he cracks a whip and turns over the Temple’s tables as though he’s dedicating it anew just as David’s son had done.

Not when he takes bread and wine and with them makes himself the New Moses.

And not when he gets up from the Exodus table, and leads his followers to, of all places, the Mount of Olives.

The Mount of Olives was ground zero. The front line.

The Mount of Olives was the place where the prophet Zechariah had promised that God’s Messiah would initiate a victory of God’s People over the enemy that bound them.

From the parody of Pilate’s parade to the palm leaves, from the prophesied donkey to the shouts of hosanna, from Solomon’s welcome to the exodus table to the Mount of Olives every one in Jerusalem knew what to expect. There could be no mistaking all the signs.

They knew how God was going to use him.

He would be David to Rome’s Goliath.

He would face down a Pharaoh named Pilate, deliver the message that the Lord has heard the cries of his People and thus says he: “Let my People go.”

As though standing in the Red Sea bed, he would watch Pilate and Herod and all the rest swallowed up in and drowned by God’s righteousness. God’s justice.

They knew how God was going to use him.

———————————

And when he invites Peter, James, and John, the same three who’d gone with him to the top of Mt. Horeb where they beheld him transfigured into glory, to go with him to the top of the Mount of Olives they probably expect a similar sight.

To see him transfigured again.

To see him charged with God’s glory.

To see him armed with it.

Armed for the final and decisive battle.

The battle that every sign and scripture from that holy week has led them to expect.

Except-

There on the top of the Mount of Olives Jesus doesn’t look at all as he had on top of that other mountain.

Then, his face had shone like the sun. Now, it’s twisted into agony.

Then, they’d seen him dazzling white with splendor. Now, he’s distraught with doubt and dread.

Then, on top of that other mountain, Moses and the prophet Elijah had appeared on either side of him. Now, on this mountaintop, he’s alone, utterly, already forsaken, alone except for what the prophet Isaiah called the ‘cup of wrath’ that’s before him.

Then, God’s voice had torn through the sky with certainty “This is my Beloved Son in whom I am well-pleased.” Now, God doesn’t speak. At all.

So much so that Karl Barth says Jesus’ prayer in the Garden doesn’t even count as prayer because it’s not a dialogue with God. It’s a one way conversation. Because it’s not just that God doesn’t speak or answer back, God’s entirely absent from him, as dark and silent to him as the whale’s belly was to Jonah.

There, on the Mount of Olives, Peter, James, and John with their half-drunk eyes- they see him transfigured again.

This would be Messiah who’d spoken bravely about carrying a cross transfigured to the point where he’s weak in the knees and terrified.

This would be Moses who’d stoically taken exodus bread and talked of his body being broken transfigured so that now he’s begging God to make it only a symbolic gesture.

This would be King who can probably still smell the hosanna palm leaves transfigured until he’s pleading for a Kingdom to come by any other means.

Peter and the sons of Zebedee, they see him transfigured a second time. From the Teacher who’d taught them to pray “Thy will be done…” to this slumped over shadow of his former self who knows the Father’s will not at all.

He’d boldly predicted his betrayal and crucifixion and now he’s telling them he’s “deeply grieved and agitated.”

Or, as the Greek inelegantly lays it out there, he tells them he’s “depressed and confused” such that what Jesus tells them in verse 38 is really “Remain here with me and stay awake, for I am so depressed I could die.”

And then he can only manage a few steps before he throws himself down on the ground, and the word Matthew uses there in verse 39, ekthembeistai, it means to shudder in horror, stricken and helpless.

He is, in every literal sense of the Greek, scared out of his mind. Or as the Book of Hebrews describes Jesus here, crying out frantically with great tears.

He is here exactly as Delacroix painted him: flat in the dirt, almost writhing, stretching out his arms, anguish in his eyes, his hands open in a desperate gesture of pleading.

God’s incarnate Son twisted into a golem of doubt and despair.

Transfigured.

As though he’s gone from God’s own righteousness in the flesh to God’s rejection of it.

———————————

Peter, James, and John, the other disciples there on the Mount of Olives, any of the other pilgrims in Jerusalem that holy week- they’re not mistaken about what should come next. They weren’t wrong to shout “Hosanna!”

They’re all correct about what to expect next. The donkey, the palm leaves, the Passover- it all points to it, they’re right. They’re all right to expect a battle.

A final, once for all, battle.

They’re just wrong about the enemy.

The enemy isn’t Pilate or Herod but the One Paul calls The Enemy.

The Pharaoh to whom we’re all- the entire human race- enslaved isn’t Caesar but Sin. Not your little s sins but Sin with a capital S, whom the New Testament calls the Ruler of this World, the Power behind all the Pharaohs and Pilates and Putins.

They’re all correct about what to expect, but their enemies are all propped up by a bigger one.

A battle is what the Gospel wants you to see in Gethsemane. The Gospel wants you to see God initiating a final confrontation with Satan, the Enemy, the Powers, Sin, Death with a capital D- the New Testament uses all those terms interchangeably, take your pick. But a battle is what you’re supposed to see.

Jesus says so himself: “Keep praying,” he tells the three disciples in the garden, “not to enter peiramos.”

The time of trial.

That’s not a generic word for any trial or hardship. That’s the New Testament’s word for the final apocalyptic battle between God and the Power of Sin.

The Gospels want you to see in the dark of Gethsemane the beginning of the battle anticipated by all those hosannas and palm branches.

But it’s not a battle that Jesus wages.

Jesus becomes its wages.

That is, the battle is waged in him.

Upon him.

From here on out, from Gethsemane to Golgotha, the will of God and the will of Satan coincide in him.

That’s why they’re both- God and Satan- absent from him here in the garden.

Here in the garden he can longer hear God the Father in prayer.

And here in the garden he lacks what even in the wilderness he had- the comfort of a clear and identifiable adversary.

Here in the garden, they’re both absent from him because they’re both set upon him. Their wills have converged on him. They’ve intersected in him.

He can’t see or hear them now because he’s the acted upon object of them.

He is forsaken- by both God and Satan.

They’ve taken their leave of him to work their wills upon him.

Just as we confess that in Christ’s flesh is the perfect union, both fully divine and fully human; here in the garden we also confess that in him there is another union, a hideous union, of wills:

The will of Sin to reject God forever by crucifying Jesus.

The will of God to reject Sin forever by crucifying Jesus.

That’s the shuddering revulsion that overwhelms Jesus in Gethsemane.

The cross isn’t a shock.

But this is: the realization breaking over him that the will of God will be done as the will of Satan is done.

In him, upon him,‘thy will be done’ will be done for both of them, God and Satan, on Earth as in Heaven and in Hell.

But that’s what Jesus freely assents to here in the garden.

He accepts that he will be the concrete and complete event of God’s rejection of Sin.

He agrees to be made vulnerable to the Power of Sin and God’s judgment of it.

He consents to absorb the worse that we can do, as slaves to Sin.

And he consents to absorb the worst that God can do- the worst that God will ever do.

As Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians 5: “For our sake, God made him to be Sin who knew no sin.”

That’s what he accepts in getting up off the ground in Gethsemane.

And only he could accept it. Only he who was without sin- who was not enslaved by it- only he could freely choose, freely choose, to become it.

To be transfigured into Sin.

———————————

Thursday morning one of Aldersgate’s college students texted me a photo from the Washington Post along with a link to an article.

It was a photo of a little child, maybe 2 or 3 years old.

A boy or a girl, I don’t know- I couldn’t tell from the thick curly hair and red cheeks and a drab olive blanket covered up any pink or blue hued clue the child’s clothes might’ve given me.

From the child’s bright black eyes it looked like the child might be smiling, but you couldn’t be sure because a respirator was masking the child’s face where a smile might go.

Gloved grown-up hands rested on the child’s shoulders.

It wasn’t until I read the whole story that I realized those bright black eyes were empty.

Dead.

“World Health Organization says Syria Chemical Attack Likely Involved Nerve Agent” ran the headline texted to me. And under the headline, under the hyperlink, the student texted me a question: “What do Christians say about this.”

And in the second line of text: a question mark.

Followed by an exclamation point.

What do Christians say?!

———————————

What do Christians say?

Looking into the vacant eyes of a nerve-gassed toddler?

What do we say?

Something trite about God’s love?

Maybe because we’ve turned God’s love into a cliche, maybe because we’ve so sentimentalized what the Church conveys in proclaiming “God loves you” but many people assume that Christians are naive about the dark reality of sin in the world.

But we’re a People who hang a torture device on an altar wall- we’re not naive. We’re not naive about the cruelties of which we’re capable. Nor are we naive about the dreadful seriousness God deals with those cruelties.

What do Christians say?

I don’t know that we have anything more to say than what we hear God say in Gethsemane.

No.

No.

The dread, final, righteous, wrath-filled “No” God speaks to Sin.

And, yes.

Yes.

The nevertheless “Yes” God speaks to his enslaved sinful creatures.

The “Yes” God in Christ speaks to drinking the cup of wrath to its last drops.

That word ‘wrath’ gets confused in Church.

Sure, we’re all sinners in the hands of a wrathful God but scripture doesn’t mean it the way you hear it. God’s wrath doesn’t mean God is petulant and petty, raging at sinful creatures like you and me, reacting to our every infraction.

God, by definition, doesn’t react.

God’s wrath means that God never changes, that in Jesus Christ God has always been determined to reject the Power of Sin that binds his creatures as slaves.

So much so that God is dead set, literally over his dead body, dead set on killing it.

Killing Sin.

To set his people free from that Pharaoh. Once. For all.

——————————

St. Paul says that in Christ God emptied himself, taking the form of a servant.

Here in Gethsemane, Christ empties himself even of that.

He empties himself completely, pours all of himself out such that Martin Luther says when Jesus gets up off the ground in Gethsemane there’s nothing left of Jesus.

There’s nothing left of his humanity.

He’s an empty vessel; so that, when he drinks the cup the Father will not not move from him, when he drinks the cup of wrath, he fills himself completely with our sinfulness.

From Gethsemane to Golgotha, that’s all there is of him.

He drinks the cup until he’s filled and running over.

You see, Jesus isn’t just a stand-in for a sinner like you or me. He isn’t just a substitute for another. He doesn’t become a sinner or any sinner. He becomes the greatest and the gravest of sinners.

It isn’t that Jesus dies an innocent among thieves. He dies as the worst sinner among them. The worst thief, the worst adulterer, the worst liar, the worst wife beater, the worst child abuser, the worst murderer, the worst war criminal.

Jesus swallows all of it. Drinks all of it down and, in doing so, draws into himself the full force of humanity’s hatred for God.

He becomes our hatred for God.

He becomes our evil.

He becomes all of our injustice.

He becomes Sin.

So that upon the Cross he does not epitomize or announce the Kingdom of God in any way.

He is the concentrated reality of everything that stands against it.

He is every Pilate and Pharaoh. He is every Herod and Hitler and Assad.

He is every Caesar and every Judas.

Every racist, every civilian casualty, every act of terror, and every chemical bomb.

All our greed. All our violence.

He is every ungodly act and every ungodly person.

He becomes all of it.

He becomes Sin.

So that God can forsake it.

Forsake it.

For our sake.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 7, 2017

Episode 88: Scot McKnight – The Hum of Angels

For Episode 88, Kenneth Tanner and Morgan Guyton checked in with podcast favorite Scot McKnight. Topics covered include a little ribbing on me, politics, and Scot’s latest books, “Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture after Genetic Science” and “The Hum of Angels: Listening for the Messengers of God Around Us”.

For Episode 88, Kenneth Tanner and Morgan Guyton checked in with podcast favorite Scot McKnight. Topics covered include a little ribbing on me, politics, and Scot’s latest books, “Adam and the Genome: Reading Scripture after Genetic Science” and “The Hum of Angels: Listening for the Messengers of God Around Us”.Next week – Martin Doblmeier of Journey Films. Followed by Robert Jenson and Rod Dreher of Benedict Option fame. Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

We’re breaking the 1K individual downloaders per episode mark.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website.

If you’re getting this by email, here’s the link.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 3, 2017

Lent 6A- Eric Hall: Jesus Wept (Again)

In addition to b-boxing and singing “The King of Glory Comes” and discussing the all-important theological question “Will my dog lick his nuts in the eschaton?” the guys talk Palm/Passion Sunday lections with theology professor Eric Hall of Carroll College and the author of the Home-brewed Christianity Guide to God.

In addition to b-boxing and singing “The King of Glory Comes” and discussing the all-important theological question “Will my dog lick his nuts in the eschaton?” the guys talk Palm/Passion Sunday lections with theology professor Eric Hall of Carroll College and the author of the Home-brewed Christianity Guide to God.

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 31, 2017

The Fitch Option: David Fitch’s Faithful Presence

Here’s a review I wrote for my friend David Fitch’s new book Faithful Presence.

Here’s a review I wrote for my friend David Fitch’s new book Faithful Presence.

On Ash Wednesday I suffered my monthly battery of labs and oncological consultation in advance of my day of maintenance chemo. During the consult, after feeling me up for lumps and red flags, my doctor flipped over a baby blue hued box of latex gloves and illustrated the standard deviation of years until relapse for my particular flavor of incurable cancer. I wrote a book called Cancer is Funny but it didn’t feel very funny looking at the bell curve of the time I’ve likely got until I make good on the promise that begins every Lenten season: ‘To dust you shall return.”

Leaving my oncologist’s office, I drove to the hospital to visit a parishioner. He’s about my age with a boy about my boy’s age. He got cancer a bit before I did. He thought he was in the clear and now it doesn’t look like it will end well. The palliative care doctor was speaking with him when I stepped through the clear, sliding ICU door. After the doctor left our first bits of conversation were interrupted by a social worker bringing with her dissonant grin a workbook, a fill-in-the-blank sort that he can use to insure that his boy knows who his dad was. We were interrupted again only moments after she left by the chaplain, dressed like an old school undertaker, offering ashes to us without explanation. It was easier for both of us to nod our heads and receive the gritty, oily shadow of a cross. “Remember,” he whispered, “to dust you came and to dust you shall return.”

As if the truth that none of us is getting out of life alive wasn’t already palpably felt between us.

The chaplain stepped over the tubes draped off the bed and left as quickly as he’d come. I sat next to the bed. I know from both from my training as a pastor and my experience as a patient, my job was neither to fix his feelings of despair nor to protect God from them. It certainly wasn’t to dump on to him the baggage I’d brought from my doctor’s office.

My job, I knew, as both a Christian and a clergyman, wasn’t to do anything for him, to bring to him my preconceived agenda but, simply, to be with him.

I listened. I touched and embraced him. I met his eyes and accepted the tears welling in my own. Mostly, I sat and kept the silence as though we were adoring the host.

I was present to him, with him, buoyed in the confidence that in this discipline of being present with him, naked and afraid- certainly one of whom Jesus calls the least among us, Christ was with us too, present in an almost tangible way that augers a permanent presence God will perfect in the fullness of time.

Here’s a question for the clergy types out there and, even, for ordinary non-pensioned Christians:

The confidence I have in the practice of being present in a hospital room, the trust I have that through the practice of presence Christ is present, why does it not extend to the other disciplines Jesus has given us?

Why is it that in the hospital room I’m content to be present, faithfully, and trust Jesus to show, yet everywhere else in my ministry I run (until I drop) on the unexamined assumption that it’s up to me to change my parishioners’ lives and then, with them, to change the world?

I trust Jesus not to be AWOL in the cancer ward but otherwise I typically operate as if God is the object of a curriculum program (for which I’m always scrambling to find the latest, shiniest product in the Cokesbury catalog) rather than the active agent in the world who calls us to participate with him and to do so not through the latest thematic teaching series but through the concrete practices he gave to us. It’s an assumption that in trying to conform people to Christ leaves them consumers instead and leaves me exhausted.

Taking his title from the coda of James Davidson Hunter’s significant book To Change the World, in Faithful Presence David Fitch unpacks the communal Christian disciplines by which God changes the world.

The grammar of that sentence is key to understanding Fitch’s work and how it connects with his preceding book Prodigal Christianity.

Whereas Fitch worries that James Davidson Hunter’s faithful presence proposal too easily becomes a prescription for individuals embodying the faith in the hopes of transforming culture, thereby underwriting the privatization and loneliness of the culture, Fitch notes how Hunter also misses, as perhaps a sociologist must, that we are not the active agents of mission.

In Faithful Presence, Fitch makes explicit that God is the subject of Christian speech; mission and transformation- they’re what God does.

Faithful presence then names a set of practices of the community but, more foundational, it names a participation in what the Living God is doing antecedent to us. Continuing the premise of Prodigal Christianity, where God the Son forsakes his inheritance to venture out into the Far Country that we call the sinful world in order to return all that belongs to the Father back to the Father, Fitch exposes the anthropological assumptions lurking behind how we conceive of the practices of the Church. They are not our means to God, for, in good Barthian fashion, scripture does not narrate our journey to God but God’s relentless journey to us. Nor do the practices simply equip us to engage in mission as though the mission was our mission. Rather the practices of the Church are the means God in Christ has given to us to locate God at work in the world and to join with God in what God is doing in the world. As Fitch writes, the practice of faithful presence is only intelligible because “God is present in the world and God uses a People faithful to his presence to make himself concrete.” God’s presence in the world, Fitch adds, cannot be apprehended generally or without mediation.

Only God can reveal God.

Therefore, we require the disciplines Jesus gave us.

Fitch’s emphasis on the disciplines echoes a bit with James KA Smith’s You Are What You Love. in that both authors lament the degree to which God in the Enlightenment got relegated to an idea or a belief in the individual’s head. Smith attempts a recovery of the practices of the faith because our formation comes through habituation not information. While Fitch would no doubt concur with Smith about the Enlightenment’s reductionism of discipleship to belief, the practices for Fitch are not merely habits to form us in our faith. They are the promised locations in which Christ is present with us and through which Christ changes the world. As Fitch notes, the Great Commission itself not only promises that Christ will be present to his people (“I am with you always”) the charge to make disciples of all nations assumes disciplines by which will be present to form disciples. The disciplines, as Fitch identifies them, bear resonances with the Catholic sacraments:

The Discipline of the Lord’s Table

The Discipline of Reconciliation

The Discipline of Proclaiming the Gospel

The Discipline of Being with the ‘Least of These’

The Discipline of Being with Children

The Discipline of the Fivefold Gifting

The Discipline of Kingdom Prayer

If Faithful Presence stopped there it would be a helpful theological corrective to how we treat the disciplines, reminding us they’re vessels of God’s activity not our mediums to God, but it would not enliven Christian imagination to broaden what we mean by engaging in God’s mission.

The unique contribution Fitch makes in Faithful Presence is arguing that each of these disciplines given to us by Christ have three interrelated and complimentary manifestations in the social spaces of our lives.

Precisely because God is the active agent of mission, on the move in the world, these disciplines should likewise force us to be on the move in a dynamic that avoids the familiar Sunday to Monday, in here-out there connection that bedevils Christians. Fitch denotes these spaces by illustrating three circles: a closed circle. a dotted circle, and a semi-circle. The closed circles represents the social space of the church. The dotted circle is an extension of the church, our friends and neighbors; like the closed circle, committed Christians still comprise the dotted circle but the dots show how this social space makes room for strangers and seekers too. The semi-circle meanwhile is what we might refer to as a third space where Christians go into the world, into their community, as a guest.

In the case of the Eucharist, for example, the closed circle is obviously the celebration of the sacrament during gathered worship.Because God is on the move, the presence of Christ in the sacramental table extends into the community so that, in the dotted circle, a Christian leader hosts friends, committed and curious, at a table in their home and, over food and wine, they pray together, make themselves vulnerable to one another, discern God’s word, and submit aspects of their lives to the lordship of Christ. Finally, in the semi-circle, the mutual vulnerability at table gets extended out into the community where the Christian is not the host but risks being the guest of neighbors and unbelievers. As Christ is present at the ornate lacquered table in the sanctuary, Christ is present at this ‘profane’ table too, at work to nurture all that is the Father’s back to him.

I taught a PDF version of Faithful Presence to a group of local pastors at Wesley Seminary last summer for a two week course on mission.

The way Fitch extends the disciplines across these social spaces to show how and where the church can engage in God’s mission shifted the entire paradigm for their thinking.

In my own United Methodist tradition, ‘mission’ has gotten redefined as good (social justice) work someone else does, be it the denominational apparatus or the credentialed missionaries funded by it. Not only does this demote our denominational connection to a funding relationship, it disempowers local churches from discerning where God is at work in their local communities. Rather than three increasingly widened circles through which we extend presence, it assumes only two closed circles, the local church celebrating the sacraments and the global church doing good works. Its an arrangement that encourages maintenance mode ministry, which in a post-Christian culture necessarily leads to exhaustion. What’s more, it leaves pastors ill-equipped to extend the disciplines into their homes and community.

Every pair of eyes in the classroom popped open as they begin to revision their ministry, asking what it would be like for them to gather neighbors and community members around the dotted circle of their table, trusting that Christ will be there to call people over time into submission to him. The possibilities multiplied for them as they applied these three social spaces to the other disciplines in Fitch’s book. And, it should be noted, these local pastors all served small congregations. The conventional way of construing mission had only disempowered and discouraged them that churches their size could not meaningfully do mission. They could neither send lots of money to the denomination nor could they execute expensive, volunteer-heavy mission projects for the less fortunate.

In the same way the limitations of a small canvas can provoke the most creative art, Fitch’s explication of these particular disciplines extended across the ordinary social spaces of their lives exploded imaginative possibilities for their ministries.

As much as Christ is present in and through a funded missionary in Cambodia, they realized, Christ is present when they sit with someone like me in the hospital room. If God is the active agent of mission and not us, then it’s silly to distinguish between ‘real’ mission and ordinary practices like breaking bread and forgiving sin.

As a preacher, I think Faithful Presence is worth the read just for the theological framework. Our Christian speech needs reminding always that God is the agent not us.

As a pastor, I believe Faithful Presence is exactly the sort of manual that maintenance modeled mainline churches need in order to learn how to engage with Christ in their post-Christian contexts. In many ways, Faithful Presence is the handbook for how resident aliens live. It offers the praxis Stanley Hauerwas’ sequel to Resident Aliens never quite managed to flesh out.

As a closet Anabaptist, however, I’m left with a question.

I’d like to see Fitch engage how Faithful Presence interacts with John Nugent’s equally good book Endangered Gospel: How Fixing the World is Killing the Church. While agreeing with Fitch that God is prodigally at work in the world, my reading of Nugent makes me wonder if Fitch has made the Church too instrumental and not a good and an end in and of itself; that is, is the Church the means through which God is changing the world or, as Nugent argues, is the Church the change, the better place, God has already made in the world?

While I hope to see future engagement between Fitch’s and Nugent’s complementary work, I suspect Fitch’s Faithful Presence is a needed companion to another book in everyone’s queue at present, Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option.

Dreher sees Western culture as lost and, in the wake of the Obergefell decision, antithetical to it. In the light of this development, Dreher recommends Christians imitate the witness of St. Benedict of Nursia, retreating into disciplined enclaves of like-minded, like-valued Christians in order to weather a new dark age.

Despite my sympathies for Dreher’s proposal, I think the Benedict Option may be a curious option to commend to Christians in this moment because, in fact, St. Benedict was not retreating from culture. Rather, he was also safeguarding the best contributions of elite and secular culture during the dark ages. Benedict helped change the world not simply by retreating from it, as Dreher suggests, but by preserving the best contributions of culture-makers. St. Benedict, then, corroborates James Davidson Hunter’s thesis that culture is changed only from the top down, from the culture-makers outward to the culture-consumers.

I believe Fitch’s Faithful Presence offers a middle way between the concerns of Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option about Christians now living as strangers in a strange land, on the one hand, and Hunter’s argument, on the other, about how cultures undergo transformation through its culture makers. In particular, Fitch’s 3 Circles of faithful presence provide Christians with a more balanced rhythm of gathering in disciplined, intentional community with other Christians, for the sort of formation and preservation Dreher seeks, but also venturing out into networks of friendships and neighborhoods to join in what God is already doing among them.

What Fitch helps us remember, even Dreher, is that discipleship is not only about practices, which can be preserved and practiced apart from culture, it is as much about participation too.

With God.

It all comes back to God’s agency.

The agency of God is perhaps the fatal flaw in Dreher’s book for he forgets, or neglects to make clear, that God is active in the world (a world Dreher would characterize as ‘lost’ to the Church) apart from the Church and God is waiting for the Church, who are God’s sent People, to join him in his work.

Because so many now are discussing the latter book, I cannot recommend the former with heartier enthusiasm.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 30, 2017

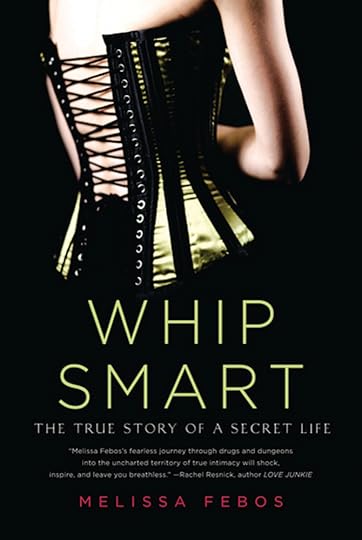

Episode 87- Melissa Febos: The Eucharist is Erotic

When the other guys on the podcast posse found out Jason’s guest, Melissa Febos, had written a memoir about her time as a dominatrix in NYC, they all got gun shy.

When the other guys on the podcast posse found out Jason’s guest, Melissa Febos, had written a memoir about her time as a dominatrix in NYC, they all got gun shy.

Their loss. I’m grateful to consider Melissa an (e) friend now.

Not gonna lie- and you can give us your feedback- but I think this conversation with Melissa is the best we’ve had yet on the podcast, ranging from writing, bodies as objects and bodies as sacraments, Woody Allen, grace, shame, mercy, and the eucharist as an erotic act.

Melissa Febos is the author of the acclaimed Whip Smart and the new memoir Abandon Me.

Her work has been widely anthologized and appears in publications including Tin House, Granta, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Glamour, Guernica, Post Road, Salon, The New York Times, Hunger Mountain, Portland Review, Dissent, The Chronicle of Higher Education Review, Bitch Magazine, Poets & Writers, The Rumpus, Drunken Boat, and Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving and Leaving New York.

Her work has been widely anthologized and appears in publications including Tin House, Granta, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Glamour, Guernica, Post Road, Salon, The New York Times, Hunger Mountain, Portland Review, Dissent, The Chronicle of Higher Education Review, Bitch Magazine, Poets & Writers, The Rumpus, Drunken Boat, and Goodbye to All That: Writers on Loving and Leaving New York.

She has been featured on NPR’s Fresh Air, CNN, Anderson Cooper Live, and elsewhere. Her essays have twice received special mention from the Best American Essays anthology and have won prizes from Prairie Schooner, Story Quarterly, and The Center for Women Writers. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, Virginia Center for Creative Arts, Vermont Studio Center, The Barbara Deming Memorial Fund, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and The MacDowell Colony.

The recipient of an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, she is currently Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Monmouth University.

Next week – Scot McKnight talks to us about angels. Week after – Martin Doblmeier of Journey Films. Followed by Robert Jenson and Rod Dreher of Benedict Option fame. Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

We’re breaking the 1K individual downloaders per episode mark.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website.

If you’re getting this by email, here’s the link.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 28, 2017

Lent 5A- Eric Hall: Rage as a Cry of Faith

In this week’s installment of Strangely Warmed we talk about the Lent 5 lections with Eric Hall, Professor of Theology at Carroll College and the author of the Home-brewed Christianity Guide to God.

In this week’s installment of Strangely Warmed we talk about the Lent 5 lections with Eric Hall, Professor of Theology at Carroll College and the author of the Home-brewed Christianity Guide to God.

In this episode we talk about Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of the dry bones, Psalm 130’s cry of despair and rage, and Jesus groaning in anger and disturbed in the spirit before the grave of Lazarus.

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 27, 2017

Meet Cute at the Well

Here’s my Lenten sermon on John 4.

Here’s my Lenten sermon on John 4.

After nearly 15 years of ministry, God finally saw fit to give me a snow day last week. I was as stoked as my fifth grader this week that the Almighty looked down upon my sweatshop-labor-lot and threw me a bone.

And gave me a snow day.

Like many of you, I’m certain, I spent the snow day in my boxers binge-watching Netflix, working my through my Netflix queue. In case you don’t know, queue is the word you use for line if you spend most of your time in drawstring pants eating ice cream and hot pockets.

I spent the day working my way through my Netflix queue until I got to a show I’d saved a month ago but then had forgotten was in my line up. I mean, my queue.

You all probably watched the show weeks ago when it premiered on Netflix, Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special.

I know our organist, Liz Miller, watched it 3 times in 1 night, and Dennis who just started another of his sabbaticals is probably watching it right now.

I’m probably the last person to have watched Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special. But just in case Karli hasn’t seen it… here’s the premise. Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special begins with Christmas.

It turns out- St. Nick’s little indentured servants made too many toys this year. Supply outpaced demand. Santa’s stuck with more inventory than nice or naughty kids.

So, to get rid of this overage emergency, like Leia to Obi Wan, Santa turns to his only hope.

That’s right, Michael Bolton.

Even if you haven’t seen it, you’ve already guessed what comes next in the story. You can anticipate what comes next. Because this is Michael Bolton we’re talking about! The man who combines the skullet hairstyle of Kenny G with a voice that’s practically an audible erogenous zone.

In the story, as soon as Santa calls upon the Soul Provider to provide the North Pole with emergency help, you know how the story will unfold.

Sure, the character Mike Bolton in Office Space calls Michael Bolton a “no talent ass clown” but we know that’s not true.

Michael Bolton’s 1,000 thread-count bedroom voice has scored 9 #1 Billboard hits. His 1991 album Time, Love, and Tenderness won a Grammy as did his cover of Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman.”

I know firsthand from my experience as a teenage lifeguard in the 1990’s- nothing got my friend’s moms to flirt with shirtless me faster than Michael Bolton’s single “Love is a Wonderful Thing” in rotation over the PA system.

Michael Bolton is like strawberries and champagne, raw oysters and bitter chocolate. He’s like lace and rose petals on silk sheets. He’s an aphrodisiac.

Michael Bolton can arouse the female species the way block grants and entitlement cuts get Paul Ryan horny.

But I digress.

My point is-

In Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special, as soon as Santa calls upon Michael Bolton you know what to expect.

You know Santa is going to call upon Michael Bolton to host a Valentine’s Day Special on TV that will inspire couples all over the world to make sweet love and conceive 100,000 new babies; thereby, solving Santa’s elf- induced extra inventory problem.

I mean, how cliched is that? You’ve seen that story arc a million times before, right?!

As soon as Santa calls upon Michael Bolton you know how the story will unfold because Michael Bolton’s bedroom baritone is so cliched it’s a storytelling convention.

It’s a trope.

A type. An archetype.

Admit it. We see story types like Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special all the time.

So we know what comes next.

It’s like how in every romantic comedy, unless he’s in a coma, Bill Pullman will get dumped by his fiance for a stranger she meets on the Empire State Building. And maybe, that’s only in Sleepless in Seattle but you know it feels like every romantic comedy you’ve ever seen.

Just like you know in every romantic comedy, at some point, a heartbroken girl will be comforted by her emotionally intelligent gay friend. It’s a storytelling convention. It’s never a dumb gay friend.

It’s never a gay friend who always says the absolute wrong thing. It’s always a sensitive, empathetic gay friend. Every time.

It’s like how in every disaster movie there are politicians who ignore and even deny the dire warnings coming from the consensus of the scientific community- not that that would ever happen in real life, it’s a type, a cliche.

A storytelling convention.

Like, how in every outdoorsy adventure movie you know it’s going to be the sidekick of color who gets eaten by the bear first.

It’s a storytelling convention.

Like opposites attract, like beauty on the inside.

Like, obviously, the gawky middle school friend you didn’t appreciate will grow up to be smoking hot (see: 13 Going on 30).

Like Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special.

They’re all rely upon cliches. Tropes. Archetypes.

Without scenery or spoken word these storytelling conventions advance the plot. They hint and foreshadow what’s to come.

Next.

The first time farm-boy Wesley says to Buttercup “As you wish” you know how it’s going to end. And because you know how it will end, you know Wesley the farm boy is not dead. You know he’s really the Dread Pirate Roberts.

And even when he’s mostly dead you know he’s not gonna die because you know that’s not how true love

stories

go.

And when John tells you that Jesus meets a woman at a well, all the stories of scripture, all the Old Testament reruns, they all lead you to expect…a wedding.

—————————

Just as surely as you know how its going to go as soon as Billy Crystal ride shares his way back to NY with Meg Ryan, all the storytelling conventions of scripture tell you what to expect when John tells you that Jesus meets a woman at a well.

Abraham’s son, Isaac, he went to a foreign land and there at a well he met a woman who was filling her jar.

And guess what Isaac said to her? “May I have some water from your jar?” And Rebekah said to him, “Yes, and I’ll draw water for you camels too.”

And just like that, before you know it, they’re getting married.

Their son, Jacob, he went east to a foreign land, and in the middle of a field surrounded by sheep he comes to a large, stone well. And there approaching the well, Jacob sees a shepherdess, coming to water her sheep, Rachel.

And this time Jacob doesn’t ask the woman for water, he goes directly to her father and asks to marry her. And before you know, well after laboring for her father for 7 years, they’re getting married.

When Moses fled Pharaoh of Egypt, he goes to a foreign land and sits down by a well. And there, says the Book of Exodus, a priest of Midian comes to the well with his 7 daughters and their flock of sheep.

A group of shepherds gather at the well too and they start to harass the priest’s daughters. Moses steps in to defend them and quicker than ‘You had me at hello” Moses is getting married to one of the priest’s daughters, Zipporah.

Ditto King Saul. Ditto the lovers in the Song of Songs. And on and on.

It’s a type scene, a cliche, a contrivance, a storytelling convention.

Isaac, Jacob, Moses and all the rest- they all meet their prospective wives at wells in a foreign land.

Meeting at a well in a foreign land- in scripture it’s like match.com or the Central Perk. You’ve seen this story before.

A man comes to a foreign land and there he finds a maiden at a well. He asks her for a drink. She obliges and more so, and then, faster than Faye Dunaway falls for Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor, the maiden runs back to get her people to witness and bless their union.

That’s how the story always goes.

———————-

So when John tells you that Jesus goes to a foreign country, Samaria, and meets a woman at a well and asks her for a drink-

You might as well cue up the jazz flute baby-making music because all the scenes of scripture have prepared you for what to expect.

Meeting a woman at a well- it’s as reliable a clue as when Jim first talks to Pam at the front desk of Dunder Mifflin. You know they’re going to get married!

And, by the way, don’t forget the first miracle, sign, Jesus performs in John’s Gospel in chapter 2 is in Cana where Jesus is a wedding guest. And how, right before this passage, in John 3, Jesus refers to himself, cryptically so, as the bridegroom. And now here in chapter 4 he’s in a foreign land, at a well, asking a woman for a drink of water.

So, if this scene is as cliched as Michael Bolton’s sex appeal, if a man meeting a maiden at a well is as contrived a storytelling convention as the sensitive gay friend, if what John wants to cue up is a wedding, then why doesn’t Jesus follow the script?

I mean, it’s not hard. It’s like swiping right on Tinder.

In scripture all you have to do is ask a girl at a well for a drink of water and someone’s practically already shouting mazel tov.

If that’s what John has cued up for us, then why does Jesus go from asking for a drink of water to talking about Living Water?

And why does this woman, who according to the convention is supposed to be a maiden, instead seem to have more baggage than Princess Vivian in Pretty Woman?

The answer? Is in the numbers.

———————-

The thing about storytelling conventions- every song uses more than one.

In every comic book movie, it’s not just that the superhero gets orphaned in front of his eyes as a kid, it’s that you know you’re going to find out later the bad guy had something to do with his parents’ murder.

The thing about storytelling conventions- every story uses more than one. In Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special, the story doesn’t just turn on Michael Bolton’s siren call sex appeal. That would be too simple of a story. The story would just be Michael Bolton helping Santa fill the world with more babies with his bedroom voice. That would be ridiculous.

No, even Michael Bolton’s Big Sexy Valentine’s Day Special requires another storytelling convention to advance the story; in this case, a villain, the owner of a no questions asked money back guarantee mattress company, who vows to kill Michael Bolton after he’s deluged with calls from customers wanting their money back because Michael Bolton has inspired them to reach such bed-destroying heights of ecstasy they want their money back.

The thing about storytelling conventions every story uses more than one. Even the Gospel of John.

Here in John 4, it’s not just the well scene and it’s the numbers.

You need both conventions, the well and the numbers, to mine the meaning of this story.

———————-

Numbers in scripture always convey meaning.

Jesus dies at the 6th hour.

12 disciples. 12 tribes of Israel.

Joshua marched around Jericho 7 times on the 7th day.

The menorah has 7 candlesticks.

And God completed creation and rested on the 7th day.

In scripture, numbers always convey meaning. It’s a storytelling convention. And in scripture, the number 7 always connotes completeness. Perfection. Fulfillment.

And if the number 7 conveys completeness, the number 6 is 7’s ugly opposite, a blemish. The number 6 is painful reminder of coming up short, of imperfection, of incompleteness.

So when John tells you this woman has had 5 husbands and she’s shacked up with 1 more (6) and now she’s meeting a 7th suitor at a well, he’s not simply telling you she has baggage. He’s giving you a clue that the tension in this story is between incompleteness and completeness.

The numbers are the other storytelling convention and the most important number to know in this story isn’t even explicit in the story.

John just expects you, the audience, to know it.

The number 3.

3- that’s the number of husbands a woman was allowed under the Jewish Law.

3- that’s it. Not 5. Not 6-ish.

3.

And it’s true Samaritans weren’t Jews, but- you can tell just from her conversation with Jesus- the Pentateuch was their scripture. The shared the same bible. They followed the Torah too.

She’s only allowed under the Law 3 husbands.

So what’s up with John telling us that she’s had 5, 6-ish, husbands?

——————————

This is where this hackneyed courtship scene from scripture becomes like a Jane Austen movie where everything turns on language and word play and misunderstanding.

The word husband in Hebrew, ba’al, means literally lord. It’s the same word Hebrew uses for a pagan deity. She’s had 5 ba’lim and now a sort of 6th.

She’s had 5 gods, 5 idols, and now a sort of 6th.

So often preachers want to make this story about Jesus crossing boundaries, gender and ethnic, to show hospitality to this unclean outsider, or they want to make it about Jesus showing grace to this woman with a profligate past.

The problems with preaching this passage that way-

On the one hand, Jesus is in Samaria not the other way around. If anyone here is crossing ethnic and gender boundaries to show hospitality to an outsider, it’s her.

On the other hand, this passage might be about grace and no doubt she’s a sinner but the ba’lim they’re talking about aren’t husbands. They’re idols.

It’s right there in scripture, in 2 Kings 17, where it describes the Assyrian invasion of Israel and how the Assyrians brought with them to Samaria from 5 different Assyrian cities their 5 different gods, 5 different idols, 5 ba’lim, husbands.

Her baggage is different than Princess Vivian in Pretty Woman. She hasn’t broken the 6th commandment. She’s broken the first.

She’s not an adulteress. She’s an idolatress.

So who’s this 6-ish husband?

This is where John 4 is like a western or a war movie. You have to know the geography to follow the story.

John expects you to know that near Sychar Herod the Great had turned the capital city of Samaria into a Roman city and named it after Caesar and filled the city with thousands of Roman colonists, settlers with whom the Samaritans did not intermarry as they had with the Assyrians.

Hence Jesus’ line “…and the one you have now is not your husband.” He’s not looking into her heart. What Jesus knows about her is what every Jew knew about her. People.

You see, it’s another storytelling convention.

This woman- she’s a stand in. A symbol.

She represents all of her people.

It’s a different kind of wedding scene because they’re not talking about her checkered past. They’re talking about her people’s worshiping 5 false gods and now they’re under the thumb of Caesar who required his subjects to worship him as a god, as a ba’al.

That’s why she calls him a prophet.

Prophets don’t look into sinners’ hearts for their secrets.

Prophets call out people’s idolatry.

That’s why their conversation so quickly turns to worship. If they’re talking about husbands husbands then it sounds like she’s changing the subject. But if they’re talking about husbands, ba’lim, as in gods, then worship is the next logical topic.

Because the Samaritans believed the presence of the true God was found atop Mt. Gerizim and the Jews believed the presence of the true God was found in the Temple in Jerusalem.

They’re talking about God.

The presence of God. Where God is to be found in spirit and truth.

Not the 5 false gods who can’t nourish, can’t quench but can give only stale water as though out of a cracked cistern, not Caesar who presumed to be a god and humiliated his subjects and forced them to tote water like slaves, but the true and living God who can give light and life like an ever flowing stream, like Living Water.

And that’s why this seventh suitor, this Mr. Perfect who embodies Michael Bolton’s first chart topping hit “How am I Supposed to Live Without You,” this would-be husband who promises to complete her like Rene does for Jerry Maguire.

He turns to her at the well.

Jesus turns to her at the well and he says to her the very same thing God said to Moses at the Burning Bush. Exactly what God said when he first revealed his name to his People. What God first said when he vowed to be their ba’al.

“I am” Jesus says to her. I am who I am. I will be who I will be.

He’s all that is.

Ego eimi.

“I am.”

And then she drops her bucket, the symbol of how her previous 5 husbands have left her parched and wanting- because they’re not real. She drops her bucket, the symbol of her 6th husband’s subjugation and abuse.

She drops her bucket.

And then she continues the storytelling convention by running off to fetch her people to witness and bless a union.

———————-

Except-

No one fetches the chuppah. No one shouts mazel tov. No one kills the fatted calf and kicks on the Michael Bolton music.

John continues the storytelling convention of the wedding at the well. She runs off to fetch her people to witness and bless a union just like all the women of scripture before her have done. Come and see, she says.

But then, there’s no wedding, no marriage, no exchange of vows.

It’s like John chooses right here to use another storytelling convention.

A cliffhanger. A season-ending ambiguity.

To Be Continued…

Because, remember, it’s a convention.

She’s just a stand-in, a symbol. She represents her people. All people.

Including, you.

The union is supposed to be with you.

You’re the one- because of you he can’t keep his mind on nothing else. He’d trade everything- power and divinity, his life- for the good he finds in you.

Sure, you’re bad. Sure, you’re a sinner. But his love for you is such…he can’t see it.

I doubt he’d ever turn his back on his best friend, but to him- you can deny him, betray him, run away from him; you can mock him, spit upon him, hang him out to dry on a cross- you can do no wrong.

He’d give up everything for you. Empty himself. Put on flesh. Take the form of a slave. Sleep out in the rain. He’d give you everything he’s got, even his life.

He’d come back from the grave just to hold onto your precious love.

And sure, I’m just cheesily quoting “When a Man Loves a Woman” right now, but the point couldn’t be more serious.

Of all the other suitors in the world, of all the idols vying for your love and affection, he’s the seventh. He’s the light to your darkness, the shepherd to little lamb you.

He’s your Mr. Darcy. The Alvy to your Annie Hall. The Tracy to your Hepburn.

Only he can complete you.

John stops the storytelling convention right here.

There’s no chuppah, no DJ, no mazel to.

There’s no exchange of vows.

Because John’s waiting for you to say “I do.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 24, 2017

Isn’t Trinity an Invention of the Church?

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

You can find all the previous posts here.

Finally, I’m now done with Part III. I hope to get all this to video format sometime in the coming year as well.

III. The Son

31. Is Trinity an Extra-Biblical Invention of the Church?

It’s true the doctrine of the Trinity is not delineated in scripture, but then, ironically, neither is the doctrine of sola scriptura so why choose the unimaginative option?

Trinity is not an invention of the Church imposed upon scripture. Rather, it is the only possible grammar by which the Church can speak of God given the witness of scripture and the testimony of the saints and apostles that Jesus is the Son; that is, Jesus is God.

For example, we’re told by John the man-who-had-been-blind worships Jesus. The man-who-had-been-blind is a good synagogue-going Jew. As such, he knows he can only worship God. But he worships Jesus who has healed him. If Jesus now can be worshipped as God, how is this revelation disclosed to the man-who-had-been-blind if not through the advocacy of the witness, the Holy Spirit, whom Jesus promised would proceed him as he has proceeded from the Father?

Trinity is not a coy and arbitrary invention of the Church imposed upon scripture for if it were we would be the worst of all possible sinners, idolators.Trinity is instead the only possible manner of speaking of God given what we, like he man-who-had-been-blind, have learned: Jesus is Lord. The man-who-had-been-blind learns this of Jesus and then worships Jesus. Very often we are blind only in other ways learn this of Jesus only by worshipping Jesus.

“Jesus heard that they had driven him out, and when he found him, he said, ‘Do you believe in the Son of Man?’ He answered, ‘And who is he, sir? Tell me, so that I may believe in him.’ Jesus said to him, ‘You have seen him, and the one speaking with you is he.’ He said, ‘Lord,* I believe.’ And he worshipped him.”

– John 9

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 23, 2017

Episode 86: Addison Hodges Hart – Winsome to the World

Alternate Title: “Beard Envy”

Alternate Title: “Beard Envy”

Jason enjoyed a wide-ranging conversation with Addison Hodges Hart, the elder brother of David Bentley Hart- who was his student- and the author of the great books Strangers and Pilgrims and Taking Jesus at his Word. Not only does Addison sound just like DBH, he speaks at length of the contemplative life, how to rethink the faith in a post-Christian culture, and the ins and outs of how he leads bible study for the curious and unchurched.

Takeaway from this episode: Addison thinks Christians need to learn how to become winsome to the world again.

Also, since you’ve bugged us about the queue…Next week – Melissa Febos Week after – Martin Doblmeier of Journey Films. Followed by Scot X. McKnight, Robert Jenson, and multiple parts with David Bentley Hart. Oh, and Rod Dreher of Benedict Option fame. Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

We’re breaking the 1K individual downloaders per episode mark.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website.

If you’re getting this by email, here’s the permanent link to the episode.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 22, 2017

God Did Not Kill Jesus Because God is Trinity

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

I’ve been working on writing a catechism, a distillation of the faith into concise questions and answers with brief supporting scriptures that could be the starting point for a conversation. The reason being I’m convinced its important for the Church to inoculate our young people with a healthy dose of catechesis before we ship them off to college, just enough so that when they first hear about Nietzsche or really study Darwin they won’t freak out and presume that what the Church taught them in 6th grade confirmation is the only wisdom the Church has to offer.

You can find all the previous posts here.

III. The Son

30. Does Trinity Mean We Worship 3 Gods?

Yes.

If you think of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as ‘persons’ of the Trinity.

But the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit are not persons; they are relations.

A “person” is an independent, individual subject. Neither the Son nor the Spirit are independent from the Father. None of the three are discrete subjects so as to be individualized from one another. Each of the three is unintelligible apart from the relationship we call Trinity.

The Son is the self-conception of the Father. The Holy Spirit is the delight the Father takes in relationship with the Son. Recall, the Father does not have a relationship with the Son nor vice versa. Rather they ARE relationship.

Not only do we not worship 3 Gods, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit possess only 1 single, unified will.

In other words, Trinity helps us read correctly the story of incarnation, cross, and resurrection as the outworking of the single, unified will of God; that is, Trinity prevents us from ever supposing the Father’s and the Son’s wills are posed against one another in the Son’s sacrifice upon the cross. We call God Trinity to remember the Father did not demand another’s death nor did the Son offer his life to anyone else in our stead. Only because God is Trinity, because Father, Son, and Spirit are relations not persons, can we profess the Judged is none other than the Judge.

Father, Son, and Spirit do not differ in any way. In each case, what they are is God and at no point in their internal life or their external work are they anything but fully God. The Father has no attributes or features the Son lacks; the Spirit has no attributes or features the Father lacks.

Because they are relations not persons, they have a single will:

Whatever we say of the Son is true of the Father.

Whatever we say of the Father is true of the Son.

And whatever we say of the Spirit is true of both.

“For I have come down from heaven to do my Father’s will.” – John 6.38

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers