Jason Micheli's Blog, page 141

May 2, 2017

Easter 4A – Brian Zahnd: Liturgy is Neither Alive Nor Dead

It’s either true or false.

This week we look at the scripture readings for the fourth Sunday in Eastertide, inviting Brian Zahnd back with us for the conversation. Brian is the pastor at Word of Life Church in Missouri and the author of Water to Wine, Beauty Will Save the World, and the forthcoming Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God.

This week’s lections include: Acts 2:42-47, Psalm 23, 1 Peter 2:19-25, John 10:1-10.

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

Follow @cmsvoteup

May 1, 2017

The Risen Substitute

Here’s my sermon on John 20.19-31 that I preached at my friend Todd Littleton‘s church in Oklahoma City. It was the first time I preached in a Baptist Church, somewhere an angel must’ve gotten his wings.

Here’s my sermon on John 20.19-31 that I preached at my friend Todd Littleton‘s church in Oklahoma City. It was the first time I preached in a Baptist Church, somewhere an angel must’ve gotten his wings.

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book.”

Uh………………………………………………………………………………….

What’s that about?

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book!?!?!?!?

Did John’s first draft come back to him marked up with red ink?

Did John have a word limit?

Should our response to scripture reading be: “This is most of the Word of God for the People of God. Thanks be to God”?

Think about it.

John believes he’s telling you the most important thing that’s ever been told- about the most important person who’s ever been and the most important cosmic event that’s ever happened.

Why would John leave anything out?

If the whole point of the Gospels is to convince beyond a shadow of a doubt that Jesus Christ is Lord…

if the whole point of the Gospels is to prove to us that the world responded to God’s love made flesh by crucifying him but that God vindicated him by raising him from the dead…

if the whole point of the Gospels is to explain to us why he came and why he died and why God raised him from the dead and what that means for us today…Then why would John not include every detail?

Why would John not submit every possible piece of evidence?

If the whole point of the Gospel is to convince us, then shouldn’t John’s Gospel be Stephen King long not Ernest Hemingway brief?

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book.”

Of course, the operative phrase there is ‘…in the presence of his first disciples.’

Because we weren’t there.

We weren’t there like John was.

We weren’t there like Peter was.

We weren’t there like Matthew or Andrew or Mary Magdalene.

We didn’t get to see with our own eyes the things Jesus did.

We didn’t get to sit at Jesus’ feet and listen to him with our own ears.

Jesus didn’t wash our feet.

I realize that just because you come to church doesn’t mean you don’t harbor serious doubts about God to say nothing of God raising a crucified, Galilean Jew from from the dead.

I also realize that the Easter season is an occasion when the every-Sunday sort of Christians think they need to hide their doubts.

And usually we hide our doubts by acting as though others shouldn’t have any doubts of their own.

As my muse, Stanley Hauerwas puts it:

“We try to assure ourselves that we really believe what we say we believe by convincing those who do not believe what we believe that they really believe what we believe once what we believe is properly explained.”

Got that?

He means:

Easter is an occasion for doubt as much as it is an occasion for faith.

So why don’t we just admit it?

This whole believing business would be a lot easier if we weren’t 2,000 plus years removed from his resurrection.

This whole having faith thing would be a lot easier if we had just been there ourselves.

———————-

But then again-

Thomas was there.

With Jesus.

Every step of the way.

With his own two eyes, Thomas saw Jesus feed 5,000 with just a few loaves and a couple of fish.

When Jesus raised Lazarus, called him out of his tomb, stinking and 3 days dead, Thomas was there.

And Thomas was there to hear for himself when Jesus told Martha, the grief-stricken sister of Lazarus:

“I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, yet shall they live.”

But all the first-hand evidence, all the eyewitness proof, all the personal experience wasn’t enough to convince Thomas.

Because on Easter night, after the women have run from the tomb terrified to tell the disciples that he is risen, the disciples run, terrified, and hide.

They hide behind locked doors and the Risen Christ comes and stands among them- just as he’d predicted he would- and says “Peace be with you.”

But Thomas wasn’t there.

The Gospel doesn’t give even an inkling of where Thomas was.

It just says “Thomas was not there with them when Jesus came.”

‘Seeing is believing’ we say, but three years of seeing for himself, of hearing for himself, of being right there with him- it wasn’t enough to convince Thomas that Jesus really was who he claimed he was.

Afterwards when the disciples tell Thomas what had happened, Thomas doesn’t respond by saying: All ten of you saw him? Alright, that’s good enough for me.

No.

Thomas insists.

The shame of the cross was to great for him to believe God would redeem it.

Resurrect it.

I will not believe unless, he says.

Unless I see his hands and his feet.

Unless I can grab hold of him and touch his wounds.

Unless I can see for myself what Rome did to him.

I need proof. I need facts. I need evidence before I will believe.

————————

This past fallI I was at the gym exercising this remarkable specimen of a body.

My head was covered in a bandana. I was wearing running shorts and a ratty old t-shirt and sneakers and looked, I thought, unrecognizable from the robed reverend I play up here on Sundays.

I was grunting and sweating and half-watching/half-listening to Luke Cage when a man, not a lot older than me, came up, tapped me on the shoulder and asked: ‘Don’t I know you?’

I told him I didn’t think so.

Maybe it was my voice that placed me.

He told me he’d met me at a funeral service- the funeral my church did a boy named Joshua in October, a little immigrant boy with brain cancer from my boy’s elementary school.

I put the weight in my hand down on the floor, wiped the sweat off on my shirt, and shook his hand.

And I suppose it was the mention of the boy’s name, his memory sneaking up on me like that, but neither one of us spoke for a few moments. We just stood there in the middle of the gym looking past each other, and probably we looked strange to anyone else might be looking at us.

‘I couldn’t do what you do’ he said, shaking his head like an insurance adjustor.

I assumed he meant funerals, couldn’t do funerals, couldn’t do funerals like that boy’s funeral.

‘Couldn’t do what?’ I asked.

‘Believe’ he said, ‘as much as I’d like to have faith I just can’t. I have too many doubts and questions.’

Thinking especially of the boy, I replied: ‘What the hell makes you think I don’t have any doubts?’

‘I guess I’m just someone who needs proof’ he said.

———————-

The first Easter wasn’t just a day.

The Risen Jesus hung around for 50 days, teaching and appearing to over 500 people.

7 days after the first Easter Day, Jesus appears again in that same locked room as before and Jesus says ‘Peace be with you.’

And this time, this time Thomas is there.

Jesus offers Thomas his body: ‘Put your finger here and see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it in my side. Do not doubt but believe.’

And Thomas reaches out to Jesus’ body.

And Thomas touches Jesus.

And Thomas grabs at the wounds of Jesus.

He grasps Jesus’ wounded feet.

He holds his hands against the holes.

Puts his hand on Jesus’ pierced side to see the proof for himself…

Actually…no.

He doesn’t.

That’s the thing-

We assume that Thomas touches Jesus’ wounds. Artists have always depicted Thomas reaching out and touching the evidence with his own hands.

Duccio drew it that way.

Caravaggio illustrated it that way.

Peter Paul Rubens painted it that way.

Artists have always shown Thomas sticking his fingers in the proof he requires in order to believe.

And that’s how we paint it in our own imaginations.

Yet, read it again, it’s not there.

The Gospel gives us no indication that Thomas actually touches the wounds in Jesus’ hands.

John never says that Thomas peeked into Jesus’ side. The Bible never says Thomas actually touches him.

No.

That’s got to be important, right?

I mean, the one thing Thomas says he needs in order to believe is the one thing John doesn’t bother to mention. What Thomas insists he needs to see is the one thing John doesn’t give you the reader to see.

Instead John tells us that Jesus offers himself to Thomas and then the next thing we are told is that Thomas confesses: ‘My Lord and my God!”

Which- pay attention– is the first time in John’s Gospel that anyone finally and fully and CORRECTLY identifies Jesus as the same Lord who made Heaven and Earth.

“Doubting” Thomas manages to make the climatic confession of faith in the Gospel.

After so many stories about the blind receiving sight and those with sight stubbornly remaining blind to who Jesus is, “Doubting” Thomas is the first person to see that the Jesus before him is the God who made him.

And “Doubting” Thomas makes that confession of faith without the one thing he insists he needs before he can muster up faith.

———————-

St. Athanasius says that Christ, as our Great High Priest, not only mediates the things of God to man but Christ also mediates the things of man to God.

Including- especially- faith.

We think of faith as something we have, something we do. We think of belief as something we will, mustering it up in us in spite of us, despite our doubts. Believing is our activity, we think. Our act.

But-

If we think of faith as something we do or possess, as an autonomous act within us, we’re not speaking of faith as scripture speaks of it.

In scripture, faith- our faith- is made possible only through the agency of God: “Lord, help my unbelief” the father in Mark’s Gospel must beg Jesus, as we all must beg.

Jesus doesn’t just put on our flesh and live the life we live. He puts on the belief, lives the faith and trust in God we owe God as creatures of God.

Jesus doesn’t just stand in our place when it comes to our sin.

He stands in our place when it comes to faith too.

What holds Good Friday and Easter together, what makes cross and resurrection inseparable, is that Jesus never stops being a substitute for us, in our place, on our behalf.

The Risen Christ remains, even here and now, every bit a substitute for us as the Crucified Christ.

Our faith, our belief, is made possible by him.

It’s his work not ours, and like a parent’s hand grasping a little child’s, our faith, such as it is, is enfolded within his perfect faith; so that, in him, enclosed within his faith, our faith is mediated to God the Father.

That’s what the New Testament means by calling Christ ‘the author and the finisher of our faith.” The faith we possess is the work of the Son within us not our own, but the faith by which the Father measures us is the Son’s not our own.

———————-

So often preachers make the point of this passage a kind of permission for us to have our doubts, that its okay we’re all like Doubting Thomas, that “doubt is a part of faith” goes the cliche.

But John would not have you see here simply Gospel approval for your doubts. This is the freaking climax of the Jesus story where someone finally and fully and correctly calls upon Jesus as his Lord and his God.

“…but its okay to have your doubts too.”

What kind of crappy whimper of an ending is that?! That’s not the takeaway John intends Thomas to leave with you. No. John wants you to see Jesus, the Risen Lord.

The same God who created from nothing.

The same God who called Israel- who had been no people- to be his People.

The same God who, Paul says, calls into existence the things that do not exist.

John wants you see the Risen Christ bringing into existence in Thomas, who had insisted unless I can touch his hands and feet for myself, a faith that can confess Christ as Lord and God.

Doubts are okay, sure.

I’ve got plenty of doubts and, I’ll bet, I’ve got more reasons to doubt than you do.

Sure, you’ve got doubts. Big deal. That’s not very interesting.

If faith is Christ’s work in us then doubt is just our natural human disposition, like Adam and Eve wondering in the Garden “Did God really say?”

Thomas’ doubt is not what John would have see.

What John would have us see:

Is that Thomas’ faith-

It’s the work of the Risen Christ.

———————-

The Good News is NOT that you are saved by faith.

Think about it: that puts all the onus on you.

It makes faith just another work. Your work.

It empties the cross of its saving significance and it makes his substitution in your place partial. Imperfect because its incomplete with out your faith.

The Good News is NOT that you are saved by faith.

The Good News is that you are saved by faith by grace.

By the gifting of God.

By the agency of God.

By the mediating activity of the Risen Christ.

Who is every bit as present to us now as those 10 disciples hiding behind locked doors.

You are saved by faith through the gracious work of the Risen Christ, who can compel you- against your natural disposition to doubt- to call upon him as your Lord and your God.

Such that whatever has brought you here

Whatever of the Gospel you are able to trust and believe

Whatever Word from the Lord you can hear in this sermon

Whether your faith is as meager as a mustard seed

Or as mighty as a mountainside

Your faith is NOT

YOUR doing.

It is a miracle. Grace. An act of the Risen Christ.

In you and upon you and through you.

And it makes you- even you!

It makes you exactly what Thomas insisted he required.

It makes you proof that he is risen. He is risen indeed.

You.

You’re why John ends his Gospel the way he does.

You’re the reason John doesn’t need to write down everything Jesus did among those disciples.

Because Jesus is neither dead nor disappeared from this world.

He’s alive and still doing work among his disciples.

And for proof you need look no further than your own faith, your own ability to call him your Lord and your God.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 30, 2017

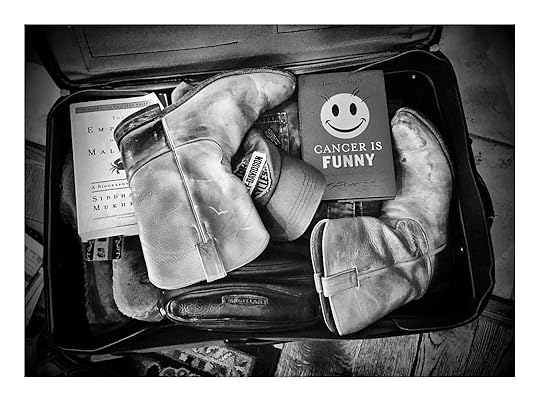

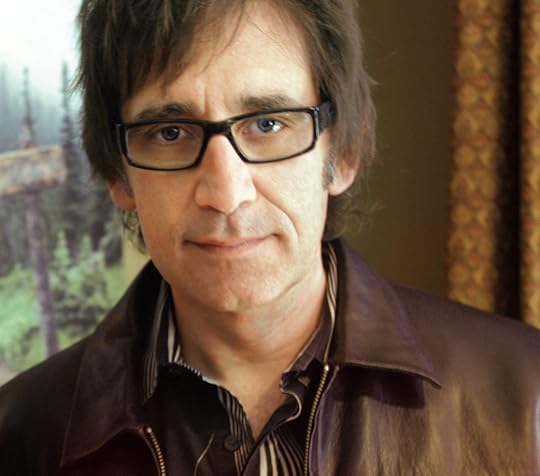

Christian Century Review: Laughing at What’s Not Funny

The Christian Century this week posted their review of my book, Cancer is Funny, and I’m so relieved it’s an enthusiastic one. I’ve read CC since I entered seminary and this review means a lot to me. Plus, I think the reviewer did a good job of reading me.

The reviewer is Deanna A. Thompson who teaches religion at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, and is the author of Hoping for More: Having Cancer, Talking Faith, and Accepting Graceand The Virtual Body of Christ in a Suffering World.

This book arrived at my doorstep the day after a friend of mine died of pancreatic cancer—the third friend in six months to die of the disease. What a laugh, that cancer.

My husband winced involuntarily when he caught a glimpse of the title printed in multicolored letters just below a big smiley face emoji with its hair falling out. In our ninth year of communally living with my very own version of stage-serious, incurable cancer, it felt more than a little sacrilegious to have this emoji and thatsentiment adorning my bedside table.

This may help explain why, when I cracked open Cancer Is Funny, I wasn’t smiling.

Less than three pages in, I came to the heading “Cancer F@#$ing Sucks” and considered not hating the book. A few sentences later, the author, a thirtysomething pastor, husband, and father of two young sons, admits, “When I first found out I had stage-serious cancer, I thought my family and I had laughed for the last time.” With that, Jason Micheli starts to gain my trust.

I’m still in the introduction when I meet up with Micheli’s reflections on how in the hell cancer might be funny. Pitching his defense at skeptical readers like myself, he rehearses all the things he doesn’t mean. He’s not referring to the “ha-ha” register we use to avoid telling hard truths, nor to the humor that masks shame or insecurities. “No, when I say cancer is funny,” Micheli writes, “I mean that your pretense falls away, right away with your pubic hair.”

Something—surely not a laugh—catches in my throat.

Micheli then turns to the kind of funny he is talking about. He invokes ancient categories and sages who say that comedy is tragedy combined with the luxury of time. He is keenly aware that for all too many cancer patients, there’s no such thing as the luxury of time. Which means there’s little opportunity to laugh while in the throes of cancer.

Even so, Micheli invites us to consider that when you’re living with stage-serious cancer, time may also condense, and laughter may become possible in ways it wasn’t before: “Who you are and who you’ve been and who you might (not) be are always ever before you, and as crowded as that sounds, it creates room for laughter. For when you don’t know if tomorrow will come, there’s no need to save face for it.”

So laugh he does. And despite my personal vendetta against cancer—or perhaps because of it—I find myself laughing along with him. Out loud. Until tears stream down my smiling face.

The pastor with cancer talks about how his journey requires more of him than he could have expected, including trading in his collar for a pair of parishioner’s shoes. He’s forced into the role of patient, that very sick guy in the hospital in need of visiting, that young man in the prime of life asking existential questions about God’s relationship to a very lousy diagnosis.

Micheli has a remarkable ability to capture the everydayness of life in the “crucible of cancer.” His attention to the tastes (of chemically charged vomit) and the sounds (of the drill going in his backside for a bone marrow biopsy) alongside the emotional upheaval paints the most compelling portrait of life eviscerated by cancer I’ve ever read.

What’s more, Micheli’s is the most vivid accounting I’ve seen of how having cancer impacts a man’s—or, more accurately, this man’s—sense of himself as a man. We’ve gotten to the part of the review where I tell you that Micheli is very practiced at humor involving the male anatomy. He gives readers ample opportunity to appreciate his own estimate of his virility and his in-shape precancer body.

While there may have been more than enough male swagger in these pages for my taste, it sets readers up to feel as gut-punched as Micheli does when, with a knit cap covering his bald head, cheeks flushed with “chemo glow,” and muscles atrophying from four rounds of chemo, he is mistaken for a woman when ordering a pink sangria for his wife at a concert he’s psyched himself up to attend with his family. He’s embarrassed “not only to be mistaken for a woman, but to be taken, as I surely must’ve been, for a homely one. Was I, I wondered in those languid seconds, even masculine-looking enough to pass as a butch woman? And did reflecting on such questions, I pondered, make me vain?”

He doesn’t leave it there. We’re right with him as his “anxiety turned to dread” and “dread to panic” as he’s called out for being “neutered” of his former self. Micheli’s wonderment at how none of the getting-through-cancer brochures prepared him for how cancer would “mess with my sense of myself as a man,” exposing a lacuna in resources aimed at helping those of us with cancer grapple with what we’ll lose. But without falling for the “cancer’s worth it because it’s made me a better person” trope, he knows these experiences have changed him; “without feeling embarrassed,” he writes, “I can now cry.”

That Micheli draws readers deeply and firmly into the “parishioner’s shoes” of life with cancer illustrates not just his pastoral heart but also his theology. The heart of the gospel message is not that God became human, he writes, but that God became Jesus. He’s not interested in theologies that counsel comfort because God shared in some generic thing called “human experience,” just as he’s not interested in a generic experience of having cancer. For all of us whose lives are shaped by the conviction that God became incarnate in a first-century Jew, it’s “the distinctive, particular ways we apply his unique story to our own” that link us.

The part of Jesus’ story that Micheli is drawn to amid life with cancer is Jesus’ death. Cancer handed him lots of opportunities to remember that in baptism we are ushered not just into the life of Christ but also into his death. The unique particularities of each of our sufferings with cancer “are ways we live out, live up to, our baptism.”

Life with cancer also heightens Micheli’s conviction that grace isn’t just an undeserved gift, but “a gift you didn’t know you needed until you received it.” Cancer is funny, Micheli insists, in the way it has helped him see what the church actually is: a group of people living into their baptisms, dispensing grace to real people facing their own non-generic crucibles, like their collarless pastor in a parishioner’s shoes.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 28, 2017

I Yet Not I

Peter, for whom words were always a stumbling block, preaches his first sermon in Acts 2 to a crowd of pilgrims gathered in Jerusalem for Shavu’ot. Having remembered their deliverance fifty days prior at Passover, on Shavu’ot Jews like Peter gathered again in Jerusalem to remember their receiving of the Torah from God on Mt. Sinai.

That the lectionary assigns this text for the third Sunday of Eastertide and pairs it with the Emmaus road revelation is a telling reminder that more is to be seen here than, as is customarily preached, the arrival of the Holy Spirit (as though the Spirit previously has been a deadbeat member of the Godhead).

Don’t forget-

Luke has already told us the Holy Spirit overshadowed Mary, alighted upon Zechariah, Elizabeth, and Simeon, compelled Christ’s first sermon, and baptized Jesus in his vicarious repentance.

Never mind the activity of the Holy Spirit throughout the Old Testament.

What Luke would have us see in Acts 2 is not the arrival of a heretofore absent Holy Spirit. The Spirit was never absent neither from Israel nor the disciples. The Holy Spirit was as present and active among the People of Israel before this Shavu’ot as the Holy Spirit is present and active among the People called Church after it.

Too often by relegating Peter’s rookie sermon to Pentecost preachers make the point of this passage Peter’s ability to preach as a product of the Holy Spirit’s arrival and, in doing so, we ignore the actual content of Peter’s preaching: the Risen Christ who is always not only the content of our proclamation but the active agent of our proclamation.

Christians joke that the Holy Spirit is the forgotten member of the Trinity but I actually think it’s Jesus. We teach Jesus’ teachings and we pray to Jesus and we preach his cross and resurrection but we neglect the ongoing agency of the Risen Christ both in the post-Easter scriptures and in our own world.

The story Luke tells in Acts 2 is no different than the story Luke tells of the encounter on the Emmaus road.

They’re both narratives about the Risen Christ making himself known to his disciples.

In the latter, the Risen Christ makes himself known in the breaking of the bread. In the former, the Risen Christ makes himself known in the proclamation of Peter. The two disciples on the way to Emmaus do not perceive Jesus on their own nor do they deduce his presence among them; likewise, Peter does not persuade his listeners to repent and be baptized nor do his listeners draw on their own any conclusions from their hearing.

The Risen Christ makes himself known in Peter’s proclamation and calls them himself to repent and be baptized, adding 3,000 to their number.

Numbers, as Brian Zahnd told me, are always important in the Bible.

The number 3,000 here in Acts 2 is another reminder that not only are we to read this passage in light of the resurrection we’re also to read it in terms of Shavu’ot.

The first Shavu’ot, as told in Exodus 32, ended with Moses and the sons of Levi taking up the sword and killing- brother, friend, and neighbor- 3,000 of the Israelites.

Why?

Because while Moses was on Mt. Sinai receiving the Torah from God- the Torah which begins “Thou shalt have no other gods before me- the Israelites were busy down below making God into, if not their own, a cow’s image. Seeing them worshipping the golden calf, Moses orders the Levites to kill the idolaters.

3,000 were substracted from God’s People that first Shavu’ot.

So when Luke reports that 3,000 were added to the disciples on Shavu’ot, as a result of the proclamation of the Gospel, we’re to see more than the Holy Spirit’s arrival, more even than a crowd compelled by Peter’s preaching to repent.

We’re to see the Risen Christ overcoming- for us, in our place- our natural proclivity to idolatry.

We typically think of conversion as something we do. Hearing a sermon such as the one Peter delivers in Acts 2, we “make a decision” for Christ, we think.

It’s true the Gospel tells us to repent and believe, to take up our cross and follow, and it’s true that this ‘decision’ is something no one else can do for us. No one else, that is, except Jesus.

If we do not allow Jesus to be a substitute for us even in our repenting and believing then, as Thomas Torrance argues, we make his atoning substitution for us something that is partial and not total, which finally empties the cross of its saving significance.

“Jesus,” says Torrance, “constitutes in himself the very substance of our conversion, so that we must think of him as taking our place even in our acts of repentance and personal decision, for without him all so-called repentance and conversion are empty.”

What holds Good Friday and Easter together, what makes cross and resurrection inseparable, is that Jesus never stops being a substitute for us, in our place, on our behalf.

The Risen Christ remains, even here and now, every bit a substitute for us as the Crucified Christ.

Jesus acts in our place in the whole range of our life lived before God. Says Torrance:

“He has believed for you, fulfilled your human response to God, even made your personal decision for you, so that he acknowledges you before God as one who has already responded to God in him, who has already believed in God through him, and whose personal decision is already implicated in Christ’s self-offering to the Father.”

Those 3,000 added on Shavu’ot are no different than the 3,000 on the first Shavu’ot. By themselves and their own faithfulness, Peter’s audience is every bit as prone to fashion and worship a golden calf.

The only difference is that the 3,000 in Acts are now in Christ. The Risen Christ is their substitute, his repentance and believing and faithfulness standing in for and empowering their own.

In him and through him, they are able to repent and believe and be baptized.

“When we say ‘I believe’ or ‘I have faith’ or ‘I repent’ we must correct ourselves and add ‘not I but Christ in me.’ That is the message of the vicarious humanity of Jesus Christ on which the Gospel tells me I may rely: that Jesus Christ in me believes in my place and at the same time takes up my poor faltering and stumbling faith into his own invariant faithfulness.”

What see in the Shavu’ot in Acts 2 is God overcoming our idolatry in the first Shavu’ot through the ongoing substitution of the Risen Christ in our place.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 27, 2017

Episode 91- Christy Thomas: It’s Time to Pull the Plug on the UMC

With the denomination seemingly on the precipice over sexuality and creaking under the weight of institutional decline, we talked with Christy Thomas about her recent article “It’s Time to Pull the Plug on the UMC.”

With the denomination seemingly on the precipice over sexuality and creaking under the weight of institutional decline, we talked with Christy Thomas about her recent article “It’s Time to Pull the Plug on the UMC.”

Christy is a writer and retired United Methodist Elder. She blogs at the Thoughtful Pastor. She writes the weekly religion column (Ask the Thoughtful Pastor) for the Denton Record-Chronicle newspaper. She also does film reviews, opinion pieces, and has completed one book (An Ordinary Death) with others in the works.

Next up: conversations with man Stanley Hauerwas says is the best theologian in America, Robert Jenson, and Rod Dreher of Benedict Option fame as well as Carol Howard Merritt about her new book.

Stay tuned and thanks to all of you for your support and feedback. We want this to be as strong an offering as we can make it so give us your thoughts.

You can download the episode and subscribe to future ones in the iTunes store here

Do Your Part!

With weekly and monthly downloads, we’ve cracked the top 5-6% of all podcasts online.

Help us reach more people: Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’ll make it more likely more strangers and pilgrims will happen upon our meager podcast. ‘Like’ our Facebook Page too. You can find it here.

Oh, wait, you can find everything and ‘like’ everything via our website. If you’re getting this by email, here’s the link. to this episode.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 26, 2017

Worry Over “The Future of the Church” is Pre-Emmaus Speech

St. Luke tells of Jesus encountering a woman possessed by a spirit. She has been bent over, unable to stand up straight, crippled for 18 years. At least, bent-over and crippled is how her neighbors see her and, presumably, Jesus’ disciples. But at the end of the story in Luke 13, after the exorcism slash healing, Jesus proclaims her to be a “daughter of Abraham.”

The point isn’t so much Jesus healing her as it Jesus teaching his listeners how properly to see her. She was a beautiful daughter of Abraham even before Jesus freed her of the spirit. Such is the entire Gospel.

It’s about learning to see.

Despite having been told that Christ is risen, the two disciples on the way to Emmaus speak of Jesus (to the stranger who is Jesus) in the past tense: “We had hoped he was the one to redeem Israel.” Having been crucified, Jesus now belongs to past history.

In the moment their eyes are opened to him- and the passive voice is key, Jesus is the agent of the revelation and Jesus remains ever thus- they don’t simply see that it’s Jesus there among them. They see that Jesus does not belong to the past, or rather they see that the past history of the historical Jesus has invaded their present, that the Jesus of this Gospel of Luke is the same yesterday, today, and forever.

Resurrection means that what is past now isn’t Jesus.

What is past is their lives lived apart from him.

In Luke’s Emmaus story, it’s not- as it’s so often interpreted from pulpits and altars- that the breaking of the bread opens their eyes or that the breaking of the eucharistic bread, magically or mechanistically, can open ours. It’s that Jesus, who is not dead, chooses that particular moment on the way to Emmaus to reveal his presence to them and that Jesus can freely choose still to reveal (or choose not to reveal) his presence to us.

The point of Luke’s story, which Karl Barth said was a lens through which the entire Gospel should be seen, is that these two Emmaus bound disciples do not deduce Jesus’ presence among them. They do not perceive it through their own agency. Jesus, risen and alive, is not only the head of the Church. He is its acting subject.

Disciples are not, in the evangelical parlance, those who’ve come to know Jesus.

Disciples are those to whom Jesus has made himself known.

As obvious a point as this may appear to you and as clear a takeaway as it is in Luke’s Gospel, post-cancer I’ve been convicted (I freaking NEVER use that word) by the extent to which my preaching, prayer, and pastoral ministry treats Jesus in the very manner those two Emmaus bound disciples do, as belonging to the past– distant in history and disappeared now to sit at the right hand of the Father.

Sure, every Eastertide I proclaim his resurrection and I’m even willing to posture apologetically to assert the historical plausibility of his resurrection; nonetheless, I treat his resurrection primarily as an event in the past and his ascension as his departure from earth to heaven, forgetting his Gospel-ending Easter promise: “Lo, I am with you always to the end of the age.”

I shouldn’t need to point out how such forgetting conveniently makes our Christianity no different than functional atheism, for it allows us to live in this world as if Jesus isn’t really, here and now, the Lord of it.

I’ve seen Jesus the same way the disciples see that bent-over woman such that those two Emmaus-bound disciples might as well have never sat down at table with the Risen Christ because I- we- still usually render him they way they did before supper. We study the Gospels as texts of what Jesus did, what Jesus taught, what Jesus said rather than proclaiming that Jesus, being very much not dead, still speaks and teaches and DOES.

To take one important example, we think of faith as something we do. Belief is our possession, we think. Faith is our activity of which we’re the acting subjects. We make a decision for Christ. We invite him into our hearts. But if Jesus is alive, if he reveals himself and open eyes on the way to Emmaus, if he confronts us behind our locked doors and summons out of us, despite our doubts, confessions like ‘My Lord and my God” then our faith is the act of the Risen Christ upon us. What Jesus does on the road to Emmaus is what Jesus only ever does still.

We don’t invite Jesus into our hearts.

The Risen Christ invades our hearts.

To take another important example, we think of the Church in such a way that effectively conjugates Jesus in the past tense the same way these Emmaus-bound disciples do.

This week in my little stream of the Church, the UMC, a Judicial Council is meeting to adjudicate the election last year of a gay bishop. How the UMC is structured just like the U.S. government and we think sexuality is our primary problem is a mystery to me, but my point is:

The UMC is fraught right now with speech about the “future of the Church” that in itself betrays a lack of resurrection faith.

Books like Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option portend ominously the demise of Christianity in the West while denominations ratchet up the pressure on pastors to play hero and arrest sobering statistical trends.

As my former teacher Beverly Gaventa says:

“We act as if the Christian faith itself were on life support and it’s our job to find ways of resurrecting it.

We act as if pollsters [behind the Pew Survey on Religion] were in charge of the world rather than simply being in charge of a few questions.”

The Church isn’t our work or creation. It is the means through which the Risen Christ works and creates.

To the extent we ‘see’ him to as he is, risen and alive and acting still, the Church- in some form or another-will always have a way forward.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 25, 2017

Easter 3A – Brian Zahnd: Fishing for Men- The Dating App

In this installment of our lectionary podcast, we talk about Lazarus’ death breath and whether Jesus needed Mentos before he rose from the dead and breathed onto his disciples. We also ponder essential questions like ‘Would Jesus have netted himself better disciples had he used Tinder?’ We also talk about the bible and how to preach it.

In this installment of our lectionary podcast, we talk about Lazarus’ death breath and whether Jesus needed Mentos before he rose from the dead and breathed onto his disciples. We also ponder essential questions like ‘Would Jesus have netted himself better disciples had he used Tinder?’ We also talk about the bible and how to preach it.

Our guest again is Brian Zahnd, pastor of Word of Life Church and author of Water to Wine. This week’s lections include: Acts 2:14a, 36-41, Psalm 116:1-4, 12-19, 1 Peter 1:17-23, Luke 24:13-35

All of it is introduced by the soulful tunes of my friend Clay Mottley.

You can subscribe to Strangely Warmed in iTunes.

You can find it on our website here.

Help us reach more people:

Give us 4 Stars and a good review there in the iTunes store.

It’s not hard and it makes all the difference.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 24, 2017

Becca Stevens: Love Heals

Becca Stevens was our guest preacher this Sunday to preach on John 20.19-31.

Becca is an Episcopal priest at Vanderbilt Chapel in Nashville, Tennessee, author of Snake Oil and many other books, and, most importantly, she is the founder of Thistle Farms, the largest social enterprise in the U.S. run by survivors of sex trafficking.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 22, 2017

Cancer is Funny (and Cheap)!

First-

In case you missed it, here’s a recent interview I did about my book for Progressive Spirit Radio and here’s the interview I did for the Drew Marshall Show.

Second-

Until April 30, you can get the e-book of Cancer is Funny for only…

$3.99.Since you, dear reader, have probably already bought the book why not use this incredibly cheap ass offer to gift the e-version to someone you know?

Here’s the link.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 21, 2017

The Resurrection is a Sacrament Not a Miracle

Christ is Risen. He is Risen indeed!

Christ is Risen. He is Risen indeed!

And indeed (sorry NT Wright) it’s not with ambiguity. As the Gospel lectionary for the Sunday after Easter Sunday makes clear, Jesus’ disciples doubted his resurrection even as they worshipped him. Thomas insisted even for more proof.

The late Dominican philosopher, Herbert McCabe reads the Easter stories as they are, straight up, in the Gospels- not as full-throated victory shouts but as qualified, murky signs of something more to come.

Jesus’ resurrection, says McCabe, belongs better to that category the Church calls sacraments:

“The cross does not show us some temporary weakness of God that is cancelled out by the resurrection.

It says something permanent about God:

not that God eternally suffers but that the eternal power of God is love; and this as expressed in history must be suffering.The cross, then, is an ambiguous symbol of weakness and triumph and it is just as important to see the ambiguity in the resurrection.

If the cross is not straightforward failure, neither is the resurrection straightforward triumph.

The victory of the resurrection is not unambiguous; this is brought out clearly in the stories of the appearances of the risen Christ.The pure triumph of the resurrection belongs to the Last Day, when we shall all share in Christ’s resurrection. That will not, in any sense, be an event in history but rather the end of history. It could no more be an event enclosed by history than the creation could be an event enclosed by time.

Perhaps we could think of Christ’s resurrection and ours as the resurrection, the victory of love over death, seen either in history (that is Christ’s resurrection) or beyond history (that is the general resurrection).

‘Your brother’ said Jesus to Martha ‘will rise again. Martha said ‘I know he will rise again on the last day.’ Jesus said ‘I am the resurrection…’

Christ’s resurrection from the tomb then would be just what the resurrection of humanity, the final consummation of human history, looks like when projected within history itself, just as the cross is what God’s creative love looks like when projected within history itself.

Christ’s resurrection is the sacrament of the last times.

Just as with the change in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, the resurrection can have a date within history without being an event enclosed by history, without being a part of the flow of change that constitutes our time.The resurrection from the tomb then is ambiguous in that it is both a presence and an absence of Christ. The resurrection surely does not mean Jesus walked out of the tomb as though nothing had happened.

On the contrary, he is more present, more bodily present, than that; but he is, nevertheless, locally or physically absent in a way that he was not before.

It is important in the Thomas story that Thomas does not in fact touch Jesus but reaches into his bodily presence by faith.

It is important in the Mary Magdalene story that Mary does not at first recognize Jesus.

Here is a resurrected, bodily presence not too tenuous but too intense to be accommodated within our common experience.So then Christ’s resurrected presence to us through the sacraments still remains a kind of absence: ‘…we proclaim his death until he comes again.’

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers