Jason Micheli's Blog, page 107

March 20, 2019

It’s Not about Sexuality: The UMC is Incompatible with the Mission of the Local Church So Make Apportionments Voluntary

On the final afternoon of the United Methodist Special General Conference in St. Louis, the Traditional Plan having just secured passage with a comfortable majority of votes, I watched from up above in the press box, as a group of pastors and lay delegates gathered through the scrum to the center of the conference floor.

On the final afternoon of the United Methodist Special General Conference in St. Louis, the Traditional Plan having just secured passage with a comfortable majority of votes, I watched from up above in the press box, as a group of pastors and lay delegates gathered through the scrum to the center of the conference floor.

They fell on their knees and wept, praying in protest and lament.

Only an arm’s distance away from them, another group of pastors and lay people sang and danced and clapped their hands in celebration.

It reminded me of how scripture reports the dedication of the Second Temple in the Old Testament. Some of the exiles, having returned home to a razed nation, celebrated the new temple. Others, scripture notes, knew this new temple was a bullshit knockoff and wept. Of course the chief difference between the Book of Ezra and General Conference is that in the former’s case the disparity in emotions was not produced by one party doing willful damage to the other party.

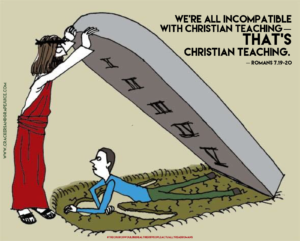

If you want to talk about what’s incompatible with Christianity, it’s that image I saw from high up top in the press box in the former home of the St. Louis Rams— this doesn’t mean, however, that it’s incompatible with United Methodism as we’ve selected to order the life of our institution.

The fallout from General Conference obscures a basic fact of organizations and leadership.

That is, every system gets exactly the results it is designed to produce.

That the decision-making mechanism known as General Conference produced such an acrimonious, callous, and (for the life of the local church) disruptive result should not be viewed as an aberation but as the expected outcome of the system as we United Methodists have arranged it since 1968.

What’s lamentable, in my view, is that the passage of the Traditional Plan has now tricked many centrist and liberal Methodists into believing that what ails United Methodism now is our denomination’s position on human sexuality.

Finally, at long last, Methodists on the left and the right poles are unaminous. Just as conservatives have long attributed Methodism’s decline to its liberal social agenda, now liberal and even moderate Methodists think our chief problem is that our denomination has the wrong stand on sexuality. An enormous amount, if not most, of our energy as centrist and liberal Methodists will now be channeled into correcting that stand rather than addressing the system which produced such a destructive, adversarial 50/50 vote.

Those who believe that all would be well in United Methodism had the One Church Plan or the Simple Plan passed are living in a fantasy.

To be sure, the passage of the Traditional Plan has given many local churches like my own little choice but to articulate an open and inclusive position towards those LGBTQ Christians in our congregations and communities, yet what’s even more regrettable in my view is that the United Methodist Church long has victimized LGBTQ Christians (and is now scapegoating conservative African Christians) to the end of ignoring the larger illness that ails us as a denomination. A shrinking tribe finds more issues over which to fight, and United Methodism has been in decline since its inception. We’d be unwise to assume that’s anomaly. Again, it’s leadership 101. Every system gets the results it’s designed to achieve.

The problem in United Methodism is not sexuality but the structure of United Methodism itself.

In nearly 20 years I have served a variety of congregations in Virginia and New Jersey, large and small, rural and metro, blue and red. In none of those settings has human sexuality been an issue. In all of those settings, the congregations, in fits and starts, showed the ability to negotiate with grace the inclusion and welcome of the LGBTQ folks in their midst. As I’ve told my present congregation, despite its marketing posture the Traditional Plan is inherently not conservative in that it has now foisted a top-down, one-size-fits-all solution to a problem most localities were finding ways to solve on their own as congregations.

This is ironic given that the first Methodists to push back on the disempowering, upside-down structure of the UMC were American conservatives in the 1990s.

The damage done by the Traditional Plan is but the clearest and most recent evidence, I believe, that the structure of the United Methodist Church is designed to serve the structure of the United Methodist Church and not the people of the United Methodist Church.

The structure of the United Methodist Church itself is incompatible with the mission of the Church to proclaim the Gospel in word, wine, bread, and deed.

And this is not a new or novel observation (though the nature of an appointive, itinerant system makes clergy and congregants reticent to voice it). The famed Methodist theologian, Albert Outler, the dude who literally coined the term “Wesleyan Quadrilateral,” argued as early as 1968:

the structure of the newly united UMC would arrest the growth of the Methodist movement, dissipate its evangelical power, create an isolated bureaucracy, and alienate and disempower local congregations.

As Will Willimon paraphrases Outler’s prophetic caution:

“Starting in 1968, distrust of the local congregation was sewn into the ethos of the denomination by the Book of Discipline.”

This distrust of the local congregation transformed what had been a Wesleyan movement into a United Methodist institution and flipped connectionalism on its head. Where connectionalism once named the very practical ways congregations pursued our common Gospel mission, now it names our organizational identity (“UMCOR does great stuff!”). As a consequence, fidelity to the organization is how we define what it means to be a faithful United Methodist; such that, pledging allegiance to itinerancy is required for ordination candidates but clear, compelling Gospel proclamation is incidental. The new structure of the UMC, Outler argued, replaced the local congregation as the primary unit of the Methodist movement. Beginning in 1968, the latent governing assumption of the UMC was that the General Church, with its bloated bureaucracy and agencies, was the “real” church whose work the local congregations were responsible to fund. This assumption was echoed doubly by the way in which the UMC then replicated the General Church structure in redundant forms at the Annual Conference and District levels. It’s seen in a detail as innocuous seeming as the red and green ink in which congregations are marked out in the conference magazine according to the level of its apportionment payments.

The General Conference decision in St. Louis is symptomatic of a larger, older illness; namely, that the structure of the United Methodist Church is not designed nor has it ever been designed to serve the people of the local church.

And now that structure has done damage to the people of the local church in ways that continue to unwind in our communties.

As many United Methodist pastors and parishioners are now discerning ways to be inclusive of LGBTQ families, just as many should be discussing how to turn the structure itself on its head and make the UMC more compatible with the mission and ministry of the local church.

One such way forward— make apportionments voluntary.

Starve the beast.

General Conference cost the UMC approximately $4,000,000.00. Next year’s 2020 GC will cost at least double that amount— why should faithful United Methodists continue to contribute to an organizational system that so clearly does not have the best interests of their local congregations in mind? Even the “good” mission and service work done by the larger UMC is work that many local congregations have no hands-on, organic relationship with other than as a donor— that donor relationship is how the General Board of Global Mission wants the relationship. And that’s the problem. In every congregation in which I’ve served, the mission and service work that parishioners are most impacted by and about which they are most passionate are the local service projects and the mission work they themselves have selected to engage hands-on. Even the more meritorious work of the larger denomination (mission) is not immune from Albert Outler’s original critique that it comes at the expense of the local church’s empowerment and fruitfulness.

The quickest way for local churches to do something about a structure that is not designed with them in mind is to stop paying for that structure.

Despite how it will be received, this is not to commit a Wesleyan heresy.

Apportionments only began in the Methodist Church in 1918 (curiously, around the same time the income tax was instituted) as John Wesley’s movement was beginning to mirror corporate America with its aspirations of becoming a national bureaucracy.

Funded by apportionments, institutional creep followed until what had been voluntary became mandatory 62 years later when the 1980 Book of Discipline removed the right of local churches to vote upon the apportionments levied on them.

Today, in my current appointment— as in my previous appointment— apportionments total nearly 1/4 of the church’s operating budget.

Just a matter of practicality—General Conference has now created a PR problem for many churches in their localties that apportionment dollars would be better spent addressing. Here in my neck of the woods, $250K can undo a lot of PR damage.

Will Willimon says the dominant ethos of the Book of Discipline since 1968 is “You can’t trust local congregations” and that the involuntary nature of apportionments is the best example of that assumption. After GC2019 in St. Louis, in which the leaders of the UMC went into a destructive, 50/50 vote that no competent pastor would even allow to happen in his or her congregation, it’s pretty clear (indeed maybe it’s the only assertion liberal and conservative Methodists could agree upon) that “you can’t trust the General Church.”

If mandatory apportionments were the mechanism which reflected the former ethos, perhaps voluntary apportionments are the mechanism to assert the current reality of the United Methodist Church.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 18, 2019

Micro-Aggression

This is a while ago now—

I’d made a promise to Ali to take steps to save money. We’d talked about cutting costs, stopping the silly spending, and making an effort to be thrifty.

“Are you on board?” she’d asked me.

With this tongue, yours truly— a pastor, this professional Christian— said “I do.”

As part of our mutual cost-cutting vow, Ali and I made the decision to liberate ourselves from the People’s Republic of Verizon.

We decided to cut the cord and get rid of our cable so that, we would get zero channels on our television. Between Netflix and Tom Brady going to the Super Bowl every year what difference television does it make?

You can imagine how popular our decision was with our children (not).

Even though our boys still claim to hate us and curse the day I sealed our FIOS receiver in its box and shipped it back to Weimar Verizon, Ali and I think it was a good and even necessary decision.

For one, we thought it was ridiculous to keep paying the mortgage payment that is the People’s Republic of Verizon’s bill— I mean, do they think we live in aiport terminals with inflated prices like that?

For another, we didn’t want out kids exposed to a constant stream of advertisements that train them to want and want and want and want and want. We didn’t want them inundated with promise after promise after promise that this or that could solve all their problems.

Of course, if you asked my wife why we got rid of our cable, she wouldn’t mention any of those reasons. No, she’d tell you it was because her husband—me—is a complete sucker for informercials.

A pushover, she’d say. An easy mark. And it’s true.

Make me a promise about giving me the power to unlock the better me inside me and I’m all yours faster than you can say shipping and handling not included.

If I was surfing the channels and I heard the words “set it and forget it” fuggedaboutit, I was hooked, convinced I absolutely needed to be able to rotisserie 6 chickens at one time.

If I was flipping channels and came across the informercial for the Forearm Max, I’d spend the next 2 hours shamefully amazed that I’ve made it this far in my life with forearms as pathetic and emasculating as mine.

If I saw the commercial for the Shake Weight, my first thought was never “that seems to simulate something that violates the Book of Leviticus, something my grandmother said would make me go blind.”

No, my first thought was always “that looks like something I need. That will solve all my problems.”

So we got rid of our cable, but that hardly solves my condition. There are advertisements and advice and promised solutions everywhere.

A couple of years ago, near Valentine’s Day, Gabriel and I went to Whole Foods to get some fish.

At that point, having cut the cord, I’d been on the infomercial wagon for 18 months, 2 weeks and 3 days. But guess what I discovered they were doing back by the seafood section?

Uh huh, a product demonstration.

And— truth be told— I thought about my promise to Ali. And I’d meant it, I’d really meant it.

The person doing the demonstration was a woman in her 20’s or 30’s.

For some inexplicable, yet very effective, reason she was wearing a black evening dress that reminded me of the one worn by Angelina Jolie in Mr and Mrs Smith, which, let’s just say, got me to thinking of myself as Brad Pritt in some extended, unrated director’s cut scenes

“Hey, let’s stick around and watch this” I said to Gabriel, who smacked his forehead with here-we-go-again embarrassment.

In addition to the slinky dress, the demonstrator was wearing a Madonna mic which pumped her bedroom voice through speakers, which beckoned all the men in the store to obey her siren call.

The product she was demonstrating that day was the Vitamix.

Have you seen one? Do you own one?

If you haven’t or don’t: the Vitamix is the blender-equivalent of that new yacht recently purchased by Dan Synder.

Angelina pulled the Vitamix out of its box like a jeweler at Tiffany’s. And then in her sleepy, kitten voice she went into her schtick:

“The Vitamix is a high-powered blending machine for your home or your office. It’s redefining what a blender can do. The Vitamix will solve all your blending problems.

With this 1 product, you won’t need any of those other tools and appliances taking up so much space in your kitchen.”

And as she spoke, I wasn’t thinking: “Who needs a high-powered blender for their office? Why does a blender need redefining? It’s just a blender.”

No, I was thinking…

“This could solve all my blending problems. If I have this, I won’t need anything else.”

I looked to my side. Gabriel was transfixed too.

The first part of her demo she showed off the Vitamix’s many juicing and blending capabilities. But then to display the diversity of the product’s features, she asked the crowd: “Who enjoys pesto?”

And like a brown-nosing boy, desperate to impress the teacher, the teacher he has a crush on, I raised my hand and spoke up: ‘“I do. I am Italian after all.”

And she smiled at me— only at at me— and she said: “I’ve always had a thing for Italians.”

Aheh.

“I went to Princeton,” I blurted out like we were speed-dating and the clock was about to sound.

“Can you cook?” she asked me. And I nodded my head, like Fonzi, too cool for words.

“Even better” she purred.

And then she pretended to be speaking to the entire crowd even though I knew now she only cared about me.

“Have you ever noticed how the pesto you buy in the store never looks fresh? It’s dark and its oily.”

And all of us men, like mosquitos headed stubbornly towards the light that will be their demise, we nodded like Stepford Husbands.

“But when you try to make pesto at home (and she held up her hands like this was a problem worthy of declaring a national emergency) food processors and traditional blenders just won’t do will they they?”

And then she looked my way, like I was a plant in the audience.

Hypnotized, I said: “No, they won’t do” even though I’ve been making pesto since I was 10 years old and I can’t say I’ve ever had a problem.

She licked some of the pesto off her spoon as though it were a lollypop or a popsicle or a Carl’s Jr commercial, and and then she said in her come-hither voice:

“I’m not married (sigh) but if I was…this is what I’d want…for Valentine’s Day.”

I drove my new Vitamix home that afternoon.

It was like I couldn’t help myself— like I was bound and determined to do the one thing I wanted not to do.

[image error]

This fall Apple CEO Tim Cook took the stage in Cupertino to hawk the latest generation of Apple’s wearable technology.

The series 4 Apple Watch was itself not really new or a noticeable upgrade over its precessors.

What was new, what was distinct, was its promise in the sales pitch:

“It’s all new. For a better you.”

The unveiling commercial at the showcase continued with the promise:

“There is a better you in you.”

There’s a better you in you and with this product you will have the freedom and power to unlock it.

The new Apple Watch is but an overt example of the same promise pitched to us three-thousand times a day.

St. Paul says in his Letter to the Romans that the Law (what we ought to do, who we ought to be) is written not just on tablets of stone but on every single human heart, believer and unbeliever alike.

Therefore, we’re hardwired to want to do and improve.

You’re hard-wired to want to be a better you and to build a better world.

Because the Law is written on your heart, you’re hard-wired to be a sucker for the promise of progress.

You’re hard-wired by the Law on the your heart to be a sucker for the promise of a better you inside you.

And so it’s not surprising that is the very same promise dangled in front of us three-thousand times a day. From our TV screens to our Facebook feeds, from our watches to our smartphone notifications, you and I are exposed to over three-thousand advertisements a day.

Three-thousand per day.

Every last single one of them relies upon the Law written on your heart.

Three-thousand times a day— the same simple, seductive formula. They identify a problem— maybe a problem you didn’t know you had until they told you you had that problem. Then they make you a promise: With this product, you can solve your problem (and maybe all your problems) and unlock the better you inside you.

Three-thousand times a day we’re promised what the Law on our hearts deceives us to believe.

There’s a better you in you.

What’s my point?

There’s a better you inside of you— very often, it’s the pitch Christians make too.

Just invite Jesus into your heart, and you’ll unlock the happier you inside of you.Your marriage will be healed. Your kids will stay the straight and narrow. You’ll feel fulfilled.

Worship, pray, serve, give— and you can unlock the Jesus-version of you inside of you, the you who’s patient and kind and utters nary an angry word.

With just three easy installments of faith in Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, you’ll live like Jesus, turning the other cheek, forgiving seventy-times-seven, you’ll never commit adultery in your heart and the log in your eye— shazaam, never to return.

Not only has my Apple Watch not liberated the better me inside me, it can’t even reliably distinguish between me sitting down and me standing up.

It failed to wake me up on time this morning, and whenever I ask Siri to play Ryan Adams music (which I won’t be doing anymore) it always plays Summer of ‘69 instead.

Likewise, what the Church often promises about faith being the key to unlock the better you inside you— to the buyer beware.

————————

Here’s the lie behind all those promises we’re pitched.

Here’s the lie the Law, written on our hearts, deceives us to believe.

Here’s the lie— the you inside you is not better.

In fact, as Jesus teaches again and again, the problem out there in the world is what comes from inside of you.

The answer to what’s wrong in the world… is you, Jesus says.

As the Book of Common Prayer puts it: “…there is no health in us.”

That’s why, St. Paul tells us today, our justification comes completely by Grace, entirely apart from the Law— because we have nothing to contribute to our salvation save our sin.

The you inside you is not better.

You’re not basically a good person who just requires a little bit of help from your friend Jesus so that you can unlock the better you inside you and live your best life now— no, that’s an ancient heresy called Pelagianism and, though it’s the most popular religion in America, it’s a lie.

The you inside you is not better.

The you inside you is bound.

The you inside you is bound.

We forget— God’s grace, God’s One-Way Love, reveals not just the character of the Giver but the condition of the Receiver.

The medicine should indicate the disease; the prescription should betray the diagnosis. You don’t require some advice or a nudge in the right direction; you require a savior.

That you require the liberating, unilateral, one-way love called Grace should tell you something about your predicament.

As Paul Zahl says, the New Testament’s High Christology— it’s view of who Christ is and what Christ has done— comes with a correlative Low Anthropology— a dim view of who we are by nature and the good we’re capable of doing.

Notice, today—

Paul announces the invasion (that’s the word Paul uses in Greek, apokalyptetai) of God’s grace in Jesus Christ without a single “if” here in chapter three.

For almost three chapters, Paul’s been raising the stakes, tightening the screws, shining the light hotter and brighter on our sins, implicating each and every one of us.

The first three chapters of Romans— it sounds like Paul’s whipping you up for an altar call until what you anticipate next from Paul is the word if.

If you turn away from your sin…

If you turn towards God…

If you repent…

If you plead for God’s mercy…

If you believe THEN God will justify you.

No— there’s no ifs there’s just this great big but, what Karl Barth says is the hinge of the Gospel, the turning of the ages: “But now, apart from the Law, apart from Religion, apart from anything we do, the righteousness of God has been revealed…”

The grace of God has invaded our world without a single if, without a single condition demanded of you, without a single expectation for your cooperation.

Because, Paul’s already told you, you’re not capable of cooperating with a single one of those conditions.

As Paul told us at the top of his argument in verse nine: All of us are under the Power of Sin. And the language the apostle uses there is the language of exodus. All of us are in bondage, Paul says, under the dominion— the lordship— of a Pharaoh called Sin.

This is a Power from whom we’re never totally free this side of the grave.

Don’t forget the Paul who celebrates the baptized walking in newness of life just after today’s text is the same Paul who laments (just after that) how the converted heart remains a heart divided against itself; such that, we all do what we do not want to do and we do not do what we want to do.

There is no health in us.

———————-

Here’s the dark but necessary underside to the Gospel of God’s One-Way Love called Grace. And, brace yourselves, in our American culture with its high, optimistic anthropology, this is going to feel like a micro-aggression, so here it comes:

You are not free.

I’m going to say it again because I know you don’t believe it: You are not free.

You are not free.

Your neighbor is not free. Your mother-in-law is not free. Your co-worker is not free. Your boss is not free. Your son? Your daughter? You might already suspect as much, neither is free. Your spouse— hell, every married person already knows this is true— is not free.

Christianly-speaking, free will is a fantasy.

Free will is a fiction.

And that’s an assertion upon which traditional Christianity, Catholic and Protestant, concur. Christianly-speaking, your will is not free.

Your will is bound.

All those promises we’re sold three-thousand times a day— they’re pitched to prisonsers not to free people (that’s exactly why they work on us!).

I realize this is the most un-American thing I could say but to speak the language of free will is not to speak Christian. Your will is not free.

It’s right there in Romans, the book of the Bible that the Church Fathers put in the middle of your New Testament so that you would know its importance for our faith.

Your will is not free. Your will is bound, doing the evil you want not to do and not doing the good you want to do.

You will is not free. Your will is torn, between a Pharaoh called Sin and a Lord named Jesus Christ; such that, all of us who’ve been rescued by grace are like the Israelites in the wilderness.

God has gotten us out of Egypt but we’ve still got Egypt in us.

The shadow side to the Gospel of God’s One-Way Love is your bound, unfree will.

Now don’t get your panties in a bunch, this doesn’t mean you’re a robot. It doesn’t mean that every moment of your life is pre-determined— the only thing predetermined in life is UVA Basketball’s disappointing play in March.

It doesn’t mean you had no choice this morning between sausage or bacon, jeans or khakis. No, when Christianity teaches that your will is not free, it means that your will is not free to choose (reliably) that which is good.

When Christianity teaches that your will is not free, it teaches that no one— because of our bondage to sin—by sheer force of will can reliably choose the right thing, which is God, for the right reason, which is selfless love.

You might choose the good and godly thing, for example, but do you do so for the right reasons? And are those reasons even always evident to you?

Our love compass is off—that’s what the Church means by the boundedness of your will.

As John Wesley’s prayerbook puts it in Article X of the 39 Articles: “The condition of Man after the fall of Adam is such, that he cannot turn and prepare himself, by his own natural strength and good works, to faith and God.”

And if all of this sounds like so much theological hocus-pocus to you, consider that Timothy Wilson, a psychologist at UVA, writes that most of us only make free, rational decisions about 13% of time— a statistic that Pat Vaughn’s wife, Margaret, corroborates.

Most of the time, Timothy Wilson argues, we’re exactly what St. Paul says we are.

We’re strangers to ourselves.

Our wills follow our hearts and our reason tags along behind.

———————-

I drove that Vitamix home from Whole Foods, and I showed it to my wife, presenting it to her like a hunter/gatherer laying his bounty at the foot of his woman’s cave.

And then I got back in my car and drove it back to the store in order to return it because, as my wife pointed out, I already had a blender and a food processor.

“Who convinced you to buy such ridiculous thing?” she asked me, and I quickly covered Gabriel’s mouth with my hand.

I shrugged my shoulders.

“I couldn’t help myself.”

And she smiled and shook her head at unfree me.

“I know you couldn’t” she said, “I forgive you. Now go return it.”

———————-

For over six months now I’ve been preaching God’s grace to you, Sunday after Sunday. And some of you have been riding me about when I’m going to get around to giving you some advice. Some of you have been riding me about when I’m going to tell you what to do.

And just so you know— I’ll stop preaching God’s grace just as soon as you actually start believing it.

I’m not going to stop preaching to you God’s grace, but that doesn’t mean God’s grace isn’t practical for everyday life.

It is practical for everyday life because everyday everywhere you go everyone you meet has a bound, unfree will.

So here’s some advice, advice on how to see other humans in light of the Gospel. Your bound, unfree will is the necessary, shadow side to the Gospel of God’s One Way Love, but it is not bad news.

It is the birth pangs of compassion.

The moment you understand the Gospel’s implication that people are not as free as they think they are, you’re able to have compassion and tenderness for them. Instead of judging them for doing wrong when they should be doing right, you can find sympathy for them.

What the Gospel teaches us about the bound will is the grace-based way to mercy.

It’s when you mistakenly think people are free, unbound, active agents of everything in their lives, choosing the terrible damaging decisions they make, that you get angry and impatient with them.

It’s then that you judge them.

And it’s then that you begin to confuse what they do for who they are.

Just because Grace is a message about what God has done doesn’t mean it has no practical implications for what we do.

Botton line—

Grace means we look at each other with the Savior’s eyes.

Grace means we look upon each other as fellow captives.

As those who never advance very far beyond needing Jesus’ final prayer: “Father forgive them, they still know not what they do.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 15, 2019

Episode #199 – Barbara Brown Taylor: Holy Envy

For this latest episode, I get to crush on talk with my hero Barbara Brown Taylor while talking with her about her new book, Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others. The author of previous books like the Preaching Life and Leaving Church, Baylor University recognized Taylor as one of the most influential preachers in the English language. I think you’ll enjoy this one.

For this latest episode, I get to crush on talk with my hero Barbara Brown Taylor while talking with her about her new book, Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others. The author of previous books like the Preaching Life and Leaving Church, Baylor University recognized Taylor as one of the most influential preachers in the English language. I think you’ll enjoy this one.

You can get her latest book here.

This goodness isn’t easy nor is it cheap. Before you listen, help us out:

Go to iTunes, look up Crackers and Grape Juice and give us a rating— it helps others find out about the podcast.

Like our Facebook Page— how easy is that?

Go to www.crackersandgrapejuice.com and click on “Support the Show.”

There you can sign up to be a monthly or one-time donor for PEANUTS.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 6, 2019

The Art of Living Posthumously

“We die the way we live,” says BJ Miller, a palliative care doctor at a facility called Zen Hospice in San Francisco, “and all of us are dying.” I heard Miller give a TED Talk a couple of years ago, and last winter I read a story about him in the NY Times.

When BJ Miller was a sophomore at Princeton University, one Monday night, he and two friends went out drinking. Late that night, on their way back, drunk and hungry, they headed to WAWA for sandwiches.

There’s a rail junction near the WAWA, connecting the campus to the city’s main train line. A commuter train was parked there that night, idle, tempting BJ Miller and his friends to climb up it.

Miller scaled it first.

When he got to the top, 11,000 volts shot out of a piece of equipment and into Miller’s watch on his left arm and down his legs. When his friends got to him, smoke was rising from his shoes.

BJ Miller woke up several days later in the burn unit at St. Barnabas Hospital to discover it wasn’t a terrible dream. More terribly, he found that his arm and his legs had been amputated.

Turmoil and anguish naturally followed those first hazy days, but eventually Miller returned to Princeton where he ended up majoring in art history.

The brokenness of the ancient sculptures— the broken arms and broken ears and broken noses— helped him affirm his own broken body as beautiful.

From Princeton, Miller went to medical school where he felt drawn to palliative care because, as he says:

“Parts of me died early on. And that’s something, one way or another, we can all say. I got to redesign my life around my death, and I can tell you it has been a liberation. I wanted to help people realize the shock of beauty or meaning in the life that proceeds one kind of death and precedes another.”

After medical school, Miller found his way to Zen Hospice in California where their goal is to de-pathologize death; that is, to recover death as a human experience and not a medical one.

They impose neither medicine nor meaning onto the dying. Rather, as Miller puts it, they let their patients “play themselves out.” Whomever they’ve been in life is who they’re encouraged to be in their dying.

For example, the NY Times story documents how Miller helped a young man named Sloan, who was dying quickly of cancer, die doing what he loved to do: drink Bud Light and play video games.

Talking about Sloan’s mundane manner of dying, Miller said this- this is what got my attention:

“The mission of Zen Hospice is about wresting death from the one- size-fits-all approach of hospitals, but it’s also about puncturing a competing impulse: our need for death to be a transcendent experience.

Most people aren’t having these profound [super-spiritual] transformative moments (in their lives or in their deaths) and if you hold that out as an expectation, they’re just going to feel like they’re failing.”

They’re going to feel like there is something they must be doing that they’re not doing.

They’re going to worry that they’re doing something wrong or they’re going to fear that they’re not doing enough.

“The dying are still very much alive and we are all dying,” BJ Miller tells the Times writer, “we die the way we live.”

———————-

We die the way we live.

He means-

Just as many die thinking that there’s something more spiritual or profound or meaningful they’re supposed to be doing and worry that they aren’t doing it or aren’t doing it right or doing it enough, we live with that same anxiety.

It’s same anxiety the crowds by the lakeshore put to Jesus: “What ought we be doing so that we’re doing the works of God?”

St. Paul says earlier in his Letter to the Romans that the Law (what we ought to do, who we ought to be) is written not just on tablets of stone but on every single human heart, believer and unbeliever alike.

Therefore, you’re hard-wired to think that there’s something else you should be doing for God.

You’re hard-wired to think there’s somone else you should be for God.

In a way, it’s natural for you to think that Jesus came down from Heaven, cancelled out your debts upon the cross, but now it’s on you to work your way up to God, climbing up to glory one commandment at a time.

The Golden Rule may not justify you before God, but with the Law written on your heart it’s not surprising you think the Golden Rule makes a good ladder up to him.

With the Law written on our hearts, it’s natural that we live in the same exhausting manner in which BJ Miller says so many of us attempt to die.

Indeed St. Paul writes in Galatians that this way of living is a ministry of death— it kills us.

It kills us because tonight’s scripture, I believe, is the only empirically verifiable, objectively true claim in all of the Bible.

Paul’s confession here in Romans 7 is an indictment of us all. None of you really know the stranger you call you. The good you want to do is very often what you do not do and the evil and damage you want to avoid is very often the very evil and damage you wreak.

As Thomas Cranmer puts Paul here: What the heart loves, the will chooses, and the mind justifies. The mind doesn’t direct the will. The mind is captive to what the will wants, and the will itself, in turn, is captive to what the heart wants.

We’re hard-wired to do, Paul says, but such doings end up deadly because we are all strangers to ourselves.

“Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death?”

———————-

Tonight, we answer Paul’s question with ash and oil.

The way we live and the way we die— it’s natural.

But the Gospel is not natural.

The Gospel must be revealed.

Because the Law comes naturally to us while the Gospel does not, we can never take the Gospel for granted. We need to remind ourselves of the Gospel over and again. So tonight we make the Gospel message plain on the best ad space available to us, our faces.

Even though what we’ll say to you tonight, “Remember that from dust you came and to dust you will return,” sounds like a micro-aggression, the medicine administered tonight is not grim but, to those who know they are sick in a Romans 7 sort of way, it is the good news of the Great Physician.

What we make plain on your face tonight is the Gospel.

“Remember that from dust you came and to dust you shall return” is Gospel because for you the only death that matters is the death you have behind you.

I’m going to say that again so you’ve got it: “Remember that from dust you came and to dust you shall return” is good news because for you the only death that matters is the death you have behind you.

Don’t let the props get in the way— what’s important about the ash-and-oil cross we smear across your fore-head is that it’s a cross.

The wages of sin is death, the Apostle Paul writes.

We mix up our metaphors on Ash Wednesday, dust…ash…dirt…sin…death…because the wage for the sin we should mourn with ashes is a death marked by the throwing of dirt.

Or the sprinkling of water.

While the words we will say to you invite you to remember that you’re going to die, the cross we smear on you invites you to remember that you already have.

The cross on your forehead isn’t a symbol of your sin.

The cross on your forehead is a symbol of your death.

Your death to sin.

That is, the cross is an oily and ashen reminder of your baptism.

“To dust you came and to dust you shall return”—- you’re gonna die— is grim godawful news not good news unless it presumes the prior promise that by your baptism you have already died the only death that ultimately matters.

You will die, sure. From dirt you came and, when your DNR kicks in or the Medicare runs out or your children lose their patience, you’ll just as surely get planted right back there.

But the death that should haunt. The death that should keep you up at night— meeting God in the good you wanted to do but did not do and the evil you did not want to do but did— the death that should haunt you is a death you’ve already died.

You’ve already been paid the wages your sins have earned.

What you have done and what you have left undone— what you have coming to you has already come to you by way of the grave we call a font.

By water and the Spirit, God drowned sinful you into Christ’s death.

The death Christ died he died to sin, once for all. The death Christ died he died for your sins, all of them, once, and in his blood by your baptism all your sins have been washed away.

We do not smudge our foreheads to solicit God’s forgiveness for our sins. We smudge our foreheads to celebrate God’s once for all forgiveness of them.

The dust on your forehead says: “You, wretched man, were dead in your trespasses.” But the cross on your forehead says: “You have been rescued, baptized, into his death for your trespasses.”

The wages of sin smudged on your head is good news not grim news.

Your sin, though incontrovertible, cannot condemn you. There is therefore now no condemnation for you.

The seal of that promise is your baptism into his death. The sign of that promise is the symbol of his death smeared on your temple.

———————-

What’s miraculous, BJ Miller contends, more miraculous than empty, contrived spiritual gestures, is watching what the dying do with their lives once they learn they have the freedom not to do anything.

What’s miraculous is watching what the dying do with their lives once they learn they have the freedom not to do anything, the freedom just to play themselves out.

“My work,” Miller says, “is to unburden them from the crushing weight of unhelpful expectations.”

The Law comes naturally to us but the Gospel does not so tonight if the ash and oil doesn’t do it then let a triple amputee agnostic working at crunchy Buddhist hospice hospital on the Left Coast remind: it’s the work of the Gospel to unburden you from the crushing weight of expectations.

It’s the work of the Gospel to unburden you from the accusations of all the Oughts and Shoulds and Musts— the Law— written on your heart, a heart which— at best— you know only dimly.

The Gospel is that, though what’s inside of you is about as beautiful as what we smear on the outside of you— though you are every bit as broken and busted up as those sculptures that rescued BJ Miller— nonetheless you are forgiven and justified and loved exactly as you are…FULL STOP.

The work of the Gospel is to unburden you of the crushing weight of that question which the Law on your heart naturally compels you to ask: “What must I be doing to be doing the works of God?”

The Gospel unburdens you to ask a different question, a question that leads to something more miraculous and even more beautiful:

What are you going to do with this faith of yours now that you have the freedom not to do anything?

What are you going to do with this life of yours now that you can live— free—with death behind you?

What are you going to do for your neighbor now that— with death behind you— there’s nothing more for you to earn.

What are you going to do now that you have the freedom not to do anything?

It’s fitting then that crowd is always smaller tonight.

Like hospice, it’s not for everybody.

The ash and oil tonight is like palliative medicine for those who are already dead in Christ.

It’s a visible, tangible reminder that you who, lives with death behind you, you’re free to play yourself out. To learn the art of living posthumously.

The ash and the oil— it marks you out as one like those busted up sculptures without the noses and the ears, broken by the Law but declared beautiful by the Gospel.

And you’ll leave here tonight not practicing your piety before others— as Jesus wants us not to do.

You’ll leave here tonight like one of those broken sculptures inviting another broken person to discover themselves beautiful.

Follow @cmsvoteup

(Her)Men*You*tics: Transfiguration

Whatever. We’re working our way through the alphabet and we thought “Trinity” would be a little unwiedly for a 20 minute conversation. So this week’s word is Transfiguration and as always Johanna is asking the hard questions. Let’s just hope her comparing Jesus to Freddie Mercury doesn’t get her struck by lightening.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 5, 2019

The Way Forward is the Way Back

Here’s another by my brother from a different mother (at least, I hope so or both of our families are f@#$#@).

Here’s another by my brother from a different mother (at least, I hope so or both of our families are f@#$#@).

I give you Drew Colby…

It all started one Sunday in 1787. On that day, Richard Allen, a Methodist preacher licensed to preach at the 1784 Christmas Conference, was forced by a church trustee to leave a “whites only” section of a sanctuary. Try not to read this as a commentary on the character of church trustees. Instead, read it as a sin, and a great loss, in the family history of the Methodist Church.

Just a few years after the American Revolution Allen and other African-Americans formed a new fellowship; but when some of them wanted to join other denominations, Allen insisted they remain Methodist, saying “there was no religious sect or denomination [that] would suit the capacity of the colored people as well as the Methodist; for the plain and simple gospel suits best for any people.” And so, after some legal battles, the AME church was formed.

Looking back, it is clear that Allen and the congregations that followed (AME, CME, etc.) maintained the holiness of the church by splitting, in faith. If we could go back and do this over, I believe Methodists like me would have been right to follow him out. If measured in average worship attendance and budget, the United Methodist Church has been more successful in the intervening years. If measured in righteousness, we would not fare as well.

More recently, in the wake of the 2015 mass shooting in a historic Charleston, SC AME church, our St. Stephen’s congregation wanted to do something to honor this church. They were not only victims of a massacre, and not only other Christians; they were fellow Methodists. They were family– estranged family–but family nonetheless.

We decided, for one Sunday, to use the AME communion liturgy for our own communion. It would be a way of learning from them, and of honoring the communion we believe we have in Christ. It was a holy experience for me.

In fact, as we prepared, I noticed how much more Anglican that liturgy actually is. So, I dug deeper into AME liturgies and their Book of Discipline. In some cases I found that this tradition has stayed better in touch with the tradition of Wesleyan Methodism than the United Methodist Church has. And, being an anglophilic liturgical snob, in many ways I liked their stuff better than ours! And so, I grieve at the effects of estrangement over time. I wish we could have kept in touch. I wish we could have stayed together.

Since that day I have pondered a sort of thought experiment. As the UMC considers and (mostly) tries to avoid a schism, what is to happen if a schism occurs? What if it is determined to be unavoidable–or even the will of God? Personally, I hope against hope that God will make a way forward where there seems to be no way. Nonetheless, I do wonder where everyone will go. Will one “side” get the “spoils” of trademarks, logos, pensions, Hymnals, and the Book of Discipline? Who will get “custody” of these things? And what if It is not my side that “wins,” whatever that means? Where will I go?

Ponder this with me: if I found myself ecclesiologically homeless, or orphaned, from the United Methodist Church, do you think the AME church would take me (back) in? Would the church that my church put out take me back? Even after we did her wrong? Is reconciliation after a split possible? Or, more broadly, is reconciliation instead of a split possible?

The answer may be no. For a number of reasons, it would probably be too awkward or difficult for some sort of pan-Methodist union to be born. And, let’s be honest, it would probably be even more awkward for me to become an African Methodist Episcopal pastor (I’m white, by the way). Our estrangement means we have grown terribly unfamiliar with one another, and we’d make strange bedfellows.

But, what if the answer were yes? What if what came out of this whole project was a re-united United Methodist Church? Imagine that. What if instead of schism, our minds were instead set on reconciliation?

Whatever the outcome of the ongoing Bishops’ Commission, I pray that the commission itself, and its aftermath, can be an opportunity to practice humility, repentance, and openness to the reconciliation revealed in the cross of Jesus Christ. May we be open to confession, forgiveness, and reconciliation in order to experience the Easter life. I can’t help but think that my 18th century ancestors would encourage all of us to consider the negative effects of estrangement over time. To avoid these effects would be prudent. To heal them would be a miracle.

The Church’s One Foundation: verse 4

’Mid toil and tribulation,

And tumult of her war,

She waits the consummation

Of peace forevermore;

Till, with the vision glorious,

Her longing eyes are blest,

And the great Church victorious

Shall be the Church at rest.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 4, 2019

“The United Methodist Church’s unfixable rot has nothing to do with sex and everything to do with polity.”

I think opposition and resistance to the Traditionalist Plan in the UMC need not equate to a progressive (I hate that term— it’s elitist) United Methodism. In fact, I think if opposition to the TP leads to or becomes synonymous with a progressive Christianity then GC2019 will only hasten our decline. Theologically speaking, I am not progressive.

I happen to think that, on the one hand, the Traditionalists are not really traditionalist in that their chief concern, sexuality, is not a matter of creedal confession and, on the other hand, the justification of the ungodly is the most inclusive and traditional doctrine possible. A bare-knuckled, unapologetic Pauline understanding of grace makes our holiness-enforcing and bickering over inclusion unintelligble as Christian speech.

Masked by the Traditionalist Plan’s regressive treatment of gay United Methodists is the larger structural problems in the denomination and the longer historic acrimony of which GC2019 was but the latest skirmish.

As Diana Butler Bass shared at a gathering of pastors and laity in my home this weekend: “Those who think that if the One Church Plan had passed all would be well in the UMC are living a fantasy.”

Had the One Church Plan passed a different 50% of the UMC would now feel aggrieved and victimized. That the math and the felt outcome would not have changed— and that the council of bishops were unable to avoid any other outcome— shows the extent to which the UMC is broken.

Christians are good at burying the dead.

Christians are seldom good at giving a funeral to church programs or polity.

Brad Todd, a good friend and parishioner, shares these thoughts on GC2019:

“The United Methodist Church has finally admitted this week that it’s not united at all but what’s worse is that few in the nation’s second-largest (for now) Protestant body seem to even understand why.

After a divisive global gathering of the denomination to sort out policies on gay ordination and gay marriage, I have been more dismayed by the way my fellow Methodists have reacted to the conference than by anything that was decided at the conference – and I think I’d be saying that no matter which side ended up on the 47 end of the 53-47 vote. That event was ill conceived and destined to fail no matter how the votes fell. Almost all American Methodists speaking out this week express angst about the church’s future – but these emotions, on both sides, are mostly unconstructive and not aimed in the direction of our problem.

The United Methodist Church’s unfixable rot has nothing to do with sex and everything to do with polity.

For the purposes of argument let’s totally set aside for the next 1,200 words what I believe is a symptom of our problem – the debate over church’s positions on homosexuality – and focus on the tectonic plate structure that ripped us open at that specific fissure. It’s not that I don’t think the debate over sexuality is one we can respectfully have, but I think people like my pastor Jason Micheli have accurately noted that the Methodist left and Methodist right have both pursued this legalistic question far outside the dominant shadow that should be cast by our shared commitment to spreading a theology of sin-cleansing Grace, and only sin-cleansing Grace.

So for a moment, let’s assume both sides on this question have enough sin and wrong to go around and look behind the way we got to this food fight.

And while we’re at it, let’s junk the faction labels crudely borrowed from secular politics (my chosen profession, incidentally) and use centuries-old, value-positive religious analogies instead – let’s call those who want to change the Book of Discipline’s policies on gays “reformers” and those who like the current policies “orthodox.”

For decades in the last century, orthodox Methodists protested the drift of the UMC on societal issues and personnel policies but their objections were beaten back by the majoritarian, procedurally rigid, top-down polity of the denomination’s quadrennial conferences.

An insulated, career-tenured church bureaucracy functionally ignored the unrest in the years between conferences. But eventually, as mainline American Christians began making church a thing of their memories and not of their lifestyles, the numbers got away from the old majority in the UMC – and the people I’m now calling “reformers” became outnumbered by a booming population of orthodox Methodists in Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe. This week in St. Louis, those globally-diverse orthodox Methodists used the same rigid majoritarian polity to stuff all notions of reform on gay marriage and ordination policies.

Too few got the irony of a mostly-white losing faction using rainbow avatars to deride the lack of inclusiveness of a real rainbow coalition on the orthodox side.

Too few got the irony of a mostly-white losing faction using rainbow avatars to deride the lack of inclusiveness of a real rainbow coalition on the orthodox side.This omission once again should have proven that the problem is polity and not people.

The United Methodist Church as we know it was forged in the post-war era dominated by national brand conformity and big, top-down, bureaucratic solutions. From government to beer brands to department stores, the age that spawned the UMC created national behemoths in almost every consumer category. But today, Sears & Roebuck is in bankruptcy and Amazon is creating a hundred million different, individualized department stores on the smartphones of a hundred million Americans. In politics, a reality show act with a can’t-miss Twitter account created an organic movement that blew up both political parties in the 2016 election. In The Great Revolt, the book I wrote with journalist Salena Zito, we attempted to put that election in the light of every other change that has happened in our economy in the 12 years since the smartphone was introduced. This Methodist failure should also be put on that timeline.

Why should United Methodists think our musty, unresponsive, hierarchy is going to fare any better in this moment of individual empowerment than any other fat, slow post-war monstrosity?

You simply cannot force people to change their minds or trust your brand today.

Organizations that dictate from the top are doomed to fall in consumer-led coups.

Sometimes those coups elect Donald Trump, sometimes those coups nearly nominate Bernie Sanders, sometimes those coups send your company to bankruptcy, and sometimes those coups split your denomination.

The likelihood of this failure in Saint Louis was entirely foreseeable – the numbers are the numbers. But the bishops and ordained church leaders and staff who cooked up the one-sided reform plan ignored the denominational dynamics they’d put in place over the last three decades, and chose to never look in the mirror. Now they seem shocked that the orthodox delegates wouldn’t accept what they smugly dubbed the “One Church Plan” (a title reeking of “do this or else” sentiment) crammed down their throats. The back up Connectional Plan – which would’ve split the church into three quasi-autonomous strains – raised so many long-lead constitutional questions that it had no chance among the delegates, reflecting the fact that it was proposed ten years too late. But tone deaf bureaucracies are always late to the party with the answer that would work. It’s the nature of the arrogance of unchecked power.

The inherent impossibility of running a bottom-up religion with top-down bishops and winner-take-all conference showdowns is the crisis Methodist now must address if we are to quit sniping at each other long enough to get back to the work of spreading the good news of Christ – together or apart.

Next year in Minneapolis when Methodists gather again for the regular global conference, this reform of our polity should be the only item on the agenda. Let’s blow the whole thing up and replace the cathode-ray tube governance model with a digital-age grass roots structure that puts congregational work first.

It might look something like this:

Make a denomination wide commitment to evangelism, above all social activism and even the good work of the church. A shrinking army argues more than a growing one, so it will be good for governance and has the added benefit of being the one thing Christ compelled the church to do (sarcasm intended.)

Allow any UMC church that wants to leave the denomination with its property to gracefully do so, provided they assume any debts associated with the property. Deed over all other church properties to the congregations that remain. Make it clear that no congregation is held captive. The mother church must earn the trust of its congregants every day and a land-poor mother church will be a more responsive mother church.

Make the job of bishop a 5-year, one-term job to be completed at the end of a ministry career. Refashion the job to be a congregational consultant and ministerial mentor instead of the current role of administering a needlessly complicated system of itinerancy and moderating parliamentary procedure.

Dismantle the bulk of the central denominational staff via generous early retirement packages. Every other industry has right-sized itself in the last decade – and many of them gave up middle management layers that were less flabby and failed than ours. Devolving power away from the central organization of the denomination is essential to sustainability in the new age of smartphone connectionalism. Keep only the departments and agencies that provide direct services to congregations, and trim even those.

Spin off the mission functions of the denomination to separate entities that are sustained only on voluntary subscription payments from congregations. As Christians we believe we are all called to mission – so our denomination should trust Christ to adequately do the compulsion.

Critics of my plan will say that this is incompatible with the inherently catholic notions of pastoral authority that have been embedded in Methodism since our founder John Wesley came from the Anglican tradition. They are right. But Bible-centric orthodox Methodists will surely agree that this pastoral authority model has few plausible New Testament roots and modern reform Methodists have to admit that this system no longer works for any of us no matter how we got it or how long it took them to realize they will never again have the numbers to run the machine.

Dueling speakers on the floor of the St. Louis conference extolled, in alternating speeches, the need for Methodism to focus on the teachings of the Bible and on the need to reach a new generation for Christ. They are both right. We need a new polity to achieve both – or either – aspiration.

Our secular politics has devolved into a poisonous frenetic cycle in which the second line of any dialogue is either: “you’re a bigot” or “you’re a traitor.” Now we’ve let those same slurs come to define how church people talk to each other. We have a better model than that.

Forgive us of our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us. Lead us not into temptation and deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 3, 2019

Exodus International

Transfiguration Sunday — Luke 9

Transfiguration Sunday — Luke 9

If you’ve endured more than a handful of sermons in a United Methodist Church, then, chances are, you already know how the preaching from this point on the mountaintop is supposed to go.

I’m supposed to point the finger at Peter and chalk this episode up as yet another example of obtuse, dunder-tongued Peter getting Jesus all wrong.

If you’ve sufferd through a few sermons on the Transfiguration, then you already know I’m expected to chide Peter for wanting to preserve this spiritual, mountaintop experience instead of rolling up his sleeves and going back down into the valley of life where we are called to serve the least, the lost, and the left behind (which, for the record— just so you get to know your pastor a little better— is my least favorite Christian cliche).

But that’s how preaching on the Transfiguration is supposed to go, right?

The way down the mountain is almost always a descent into moralism— about how discipleship is about going back down into the valley, into the grit and the grind of everyday life, where we can feed the hungry and cloth the naked and embrace the outcast and do everything else upper middle class Christians aren’t embarrassed to affirm in front of their non-Christian co-workers.

If you’ve endured more than a few Sundays in the mainline church, then you already know that’s usually the way preachers preach this text on the Transfiguration: Don’t rest in Christ. Go back down the mountaintop, back into “real life,” and do like Christ.

Given the way sermons on the Transfiguration always go, you’d think that’s the only option allowed.

——————

Except-

If Peter is wrong, if this is nothing more than another example of how obtuse Peter is, then when Peter professes “Master, it is good for us to be here. Let us make three tabernacles, one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah” why doesn’t Jesus correct him?

Why doesn’t Jesus rebuff Peter and say: ‘No, it is good for us to go back down the mountain to serve the least, the lost, and the lonely?’

Why doesn’t Jesus scold Peter: ‘Peter, it’s not about resting in me. It’s about doing like me, for the Son of Man came not to serve but to send you out to serve?” If Peter’s suggestion that they rest there is such a grave temptation, then why doesn’t Jesus exhort him like he does just before this scene and say: ‘Get behind me, Satan?’ If Peter is so wrong, then why doesn’t Jesus respond by rebuking Peter? It’s not an idle question.

In fact— pay attention now— here on the mountaintop, it’s the only instance in any of the Gospels where Jesus doesn’t respond at all to something that someone has said to him.

You got that? This is the only instance in the Bible where someone says something to Jesus and Jesus doesn’t reply.

—————-

Ludwig Feuerbach, a 19th century critic of religion, accused Christians that all our theology is really only anthropology, that rather than talking about God, as we claim, most of the time we’re in fact only speaking about ourselves in a loud voice.

There’s perhaps no better proof of Feuerbach’s accusation than our propensity to make Peter the point of this scripture. To make this theophany, anthropology. To transfigure this preview of the Gospel message into moralism.

Just think-

What would Peter make of the fact that so many preachers like me make Peter the subject of our preaching— how we should go and do what he doesn’t seem to understand he should go and do? Which is but a way of making ourselves the focus of this story.

Don’t forget that this is the same Peter who insisted that he was not worthy to die in the same manner as Christ and so asked to be crucified upside down. More than any of us, Peter would know that he should not be the subject of our sermons. Peter would know that the takeaway from the Transfiguration is not what we must go down and do for God through our good deeds or holy living. The takeaway from the Transfiguration is what God is about to go down and do for us.

For ALL of us.

For ALL of us.

I’m going to say it again— for ALL of us.

The Transfiguratin is about what God is about to go down and do.

Once for ALL.

The Transfiguration— it is a preview of the Gospel.

————–

Luke spells it out for you:

Just before this scene, Jesus tells the disciples that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, be rejected by the super-pious holiness enforcers, and get crucified by an angry crowd taking the only democratic vote in scripture (“We want Barabbas!”)

Next scene, today’s scene:

Moses and Elijah, the giver of the Law and the prophet of the Law, are there on this mountaintop “speaking with Jesus about his departure which he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem.”

Accomplish.

Luke doesn’t say Jesus was about to experience something unfortunate or unintended in Jerusalem. He says accomplish.

It’s vogue among preachers today to downplay the crucifixion, but when you read the Gospels straight through you discover that not only does Jesus talk about his death all the time, he speaks of it as a necessity.

He speaks of it as a mission he will accomplish.

Luke says here that Jesus speaks of his crucifixion as a departure that he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem.

And the Greek word Luke uses for departure? Any guesses?

Exodus.

They’re talking about the exodus he will accomplish in Jerusalem.

You see, what St. Luke shows you here on the mountaintop is what St. Paul tells you in his Letter to the Romans: that our baptism into Christ’s death— it is our exodus from the Pharaoh called Sin. In case you miss that point— Luke piles on the clues. He tells you about Jesus’s shining happy people face and his bedazzled Rick Flair clothes. And Luke tells you that Moses and Elijah appeared there in glory. And that Christ became it. Became the glory That Christ was transfigured before them into glory.

————–

Luke doesn’t throw around glory as just any generic adjective.

It’s like Indiana Jones asked in Raiders of the Lost Ark: “Didn’t any of you guys ever go to Sunday School?”

In the David story, the glory of God is what spilled forth from the ark of the Law and struck an innocent bystanding boy named Uzzah dead. That’s 2 Samuel 6. That’s why Indiana Jones tells Marion to close her eyes when the bad guys open up the ark— he knows the Uzzah story.

And likely, Indiana Jones knows too that the glory of God is what dwelt in the Temple.

In the holy of holies.

Behind the temple veil. A veil that was there— pay attention now— not to protect the holy God from sinful us. A veil that was there— by God’s own mercy and design— to protect sinful us from the holiness of God.

Elijah and Moses appeared to them on the mountaintop in glory, Luke tells us.

The glory of God transfigured Christ, Luke tells us.

And Peter and James and John beheld the glory, Luke tells us.

Notice what Luke doesn’t tell us— they lived.

They lived. All three of them, they’re like Harry Potter. They’re the boys who lived.

Peter and James and John— sinners all, Peter maybe most of all— beheld the umediated glory of God, loosed from the Temple, in the flesh in the transfigured Christ, and they did not receive the wage their sins had earned them.

They were not struck dead.

They lived.

That’s why they walk away dead silent.

They were dumbfounded by this preview of the grace of God where another’s death will do for undeserving sinners.

————–

All the news in the United Methodist Church this week, all of the acrimony over inclusion and acceptance, on the one hand, and sin and holiness, on the other hand— it can obscure a basic presupposition of the Bible that’s implicit here in the Transfiguration.

What even Indiana Jones knew that all those folks at General Conference in St. Louis seemed not to know is this basic Gospel grammar:

You aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way you are.

(So who are we to draw lines?)

What makes you a child of God isn’t anything inherent to you or achievable by you. Not a one of you. All of us— the gap between our sinfulness and the holiness of God is too great. So great, in fact, that when we even begin to argue about whether this or that is a sin is to have lost the Gospel plot.

You aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way you are.

You have to be rendered acceptable.

You have to be made acceptable.

You are a child of God not by birth but by adoption— an adoption that St. Paul calls an exodus, our baptism into Christ’s death. You aren’t acceptable before the Lord just the way you are— not a one of us. That’s the assumption that animates all the action at the Temple where glory lived, and it’s the assumption that leaves Peter and James and John speechless after they run into that glory on the mountain.

To understand this you have to go back to the Book of Leviticus.

Once a year a representative of all the people, the high priest, would draw the short straw and venture beyond the temple veil, into the holy of holies, to draw near to the glory of God and ask God to remove his people’s sins so that they might be made acceptable before the Lord. Acceptable for their relationship with the Lord. Acceptable to be counted among God’s People.

After following every detail of every preparatory ritual, before God, the high priest lays both his hands on the head of a goat and confesses onto it, transfers onto it, the iniquity of God’s People.

And after the high priest’s work was finished, the goat would bear the people’s sin away into the godforsaken wilderness; so that, now, until next Yom Kippur, nothing can separate them from the love of God.

It’s easy for us with our un-Jewish eyes to see this Old Testament God veiled in glory as alien from the New Testament God we think we know. But, as Christians we’re not to see them as alien rituals or inadequate even.

We’re meant to see them as preparation.

We’re meant to see them as God’s way of preparing his People for a single, perfect sacrifice.

That’s exactly how the New Testament Book of Hebrews frames Jesus’ death:

As the perfect sacrifice for sin.

One sacrifice. Offered once.

The temple veil is no longer needed.

The glory of the Holy God need be feared no more.

One sacrifice. Offered once.

Such that now our justification before God is based not on who we are or what we’ve done but on who God is and what God has done in Jesus Christ.

Because of Christ’s perfect sacrifice— because of our exodus, our baptism into his sacrifice offered in our stead— our acceptablity before God— for all of us— must always and forever be spoken of in the past, perfect tense.

It has been accomplished.

It is finished.

Ephapax is the word the Bible uses to describe the sacrifice, which Luke here calls an exodus.

Ephapax: “once for all.”

For all sin.

For past sin. For present sin. For future sin.

Ephapax.

Once for all sin.

Once for all those believers adopted by the baptism of his blood.

————–

So why in the hell are some arguing in the United Methodist Church about who is and is not compatible with Christian teaching?

We’re all incompatible with Christian teaching— that’s Christian teaching.

According to the survey I sent, there’s two dozen LGBTQ people in this congregation.

If you think they’re the ones incompatible with Christian teaching, you need to read your Romans, or try the Sermon on the Mount on for size (Be perfect?!).

We’re all incompatible with Christian teaching. Why are we dividing Christ’s Church by arguing over who is acceptable? None of us— not a single one of us— are acceptable. All of us have been made acceptable.

Don’t you see—

The cross of Jesus Christ already contains everything conveyed by a rainbow flag.

God judges not a one of us according to us. God judges every one of us according to Christ— according to Christ’s perfect (once for all sin, once for everybody) sacrifice.

Such that, now, by grace alone— not by what you do or who you are— by grace alone— now, like those three disciples on the mountaintop today, you and I (though sinners we are and sinners we always will remain) We can sleep easy before the glory of God.

We can sleep easy before the glory of God.

Luke shows you in their sleeping what St. Paul tells you: “While we were yet sinners, Christ died for us…there is therefore NOW NO CONDEMNATION…NOTHING CAN SEPARATE US FROM THE LOVE OF GOD IN CHRIST JESUS.”

Why are we arguing when all of us— gay or straight, liberal or conservative, married or divorced, addicts or clean, racists or sexists or homophobes, skinny or not so skinny, black or white or brown, male or female (or somewhere in between), old or young, rich and poor, even people who actually like Maroon 5…all of us sinners have been made acceptable.

Not by our behavior.

Not by by our belief.

But by our baptism.

By our baptism into his departure, his exodus, his once for all death accomplished for you, for your sin…by our baptism, you and I— still in our sins— we can sleep easy before the glory of God.

That’s the Gospel.

Everything else— every single other thing we can say—is the Law not the Gospel.

And Christ is the end of the Law, scripture says.

For freedom from the Law, Christ has set us free, scripture says.

That’s the other takeaway Luke wants you to see in this preview of the Gospel.

Jesus appears there with Moses and Elijah, the giver of the Law and the prophet of the Law, because the Law— with all of its demands for holiness, all of its expectations of a lifestyle compatibile with its commands— the Law ends in Jesus Christ.

Full stop.

Moses and Elijah appear there in glory but their glory fades.

The glory of God is the Christ who delivers grace.

You see—

Christianity is either all grace (what God has done for you) or it’s all works (what you must do for God).

Grace and Works— they’re mutually exclusive.

That is the insight of the Protestant Reformation.

If it’s not all of the former, it is all of the latter— no matter the lip service you might pay to grace.

Any attempt to balance or blend grace with works destroys the very notion of grace.

It muddles the Gospel with the Law. It creates a kind of Glawspel, which is exactly the sort of toxic religion I witnessed this week in St. Louis.

Everything that is not the Gospel of grace is the Law.

And as soon as you make Christianity about the Law, you become a debtor to every single one of its demands— it’s funny how, as much as we fire off scripture at each other, we don’t much quote that scripture.

As soon as you make Christiantity about the Law, you become a debtor to every single one of its demands. And thus far, only one guy has been able to clear that bar. He was as perfect as his Father in Heaven is perfect.

So why don’t we worry about proclaiming what Christ has done for us— for ALL OF US— instead of yelling at each other about what we think the other ought to do for Christ?

————–

Whenever you make Christianity about the Law— about living a life compatible with the commandments— you become a debter to every single one of its demands.

Don’t you see?

That’s why this is the only place in all of scripture that Jesus doesn’t reply.

That’s why Jesus doesn’t rebut him.

That’s why Jesus doesn’t say “Get behind me, Satan.”

Peter is right.

It is good for us to be here— at least, it should be.

Peter is right.

It is good for us to be here.

It is good for us to see that the Law, according to which not one of us measures up, ends in the glory of his grace; so that, the Law is fulfilled in us not through our pious deeds or holy living but through faith alone.

Faith alone in the Gospel of grace is what reckons to you the credit of a lifestyle compatible with Christian teaching.

That’s not just good news.

That’s the good news.

So Peter is right.

It is good for us to be here.

Because the Church is the only place in the world— at least, it should be— twhere we can lay down all our burdens of what we ought to do but don’t and what we oughtn’t do but did— this is the only place where we can lay those burdens down and rest.

Rest in his grace.

————–

On Tuesday afternoon in St. Louis, after the vote, I watched from up above in the press box, as a group of pastors and lay delegates gathered through the scrum to the center of the conference floor. They fell on their knees and wept.

Only an arm’s distance away from them, another group of pastors and lay people sang and danced and clapped their hands in celebration.

If you want to talk about what’s incompatible with Christianity— it’s that image I saw from high up top in the press box.

Peter is right.

Until we learn to lay down the Law and go cold turkey from commandment-keeping and holiness-enforcing, until we learn to rest in Grace, every journey back down the mountain will be a descent that leaves the Gospel behind.

So come down to the Table.

And roll up your sleeves.

Come down to the Table.

Where Christ invites you not to serve but to be served.

Wine and bread. The Body and Blood. The tangible promise of grace.

Come down.

Taste and see the goodness of God that is yours.

Not as your wage, something you earn.

But as your inheritance, something that’s yours by way of another’s death, something that is yours as an adopted child of God.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 1, 2019

Episode #197: Emma Green — “Because Beth Moore is Their Pastor” (GC2019)