Jason Micheli's Blog, page 106

April 11, 2019

Can We be Condemned for Believing that All Shall be Saved?

Hello Rev. Micheli,

My name is Matthew _______, I’m an enormous fan of your work.

I was reading Rob Bell the other day and was a bit disturbed by this line: “It’s been clearly communicated to many that this belief (in hell as eternal, conscious torment) is a central truth of the Christian faith and to reject it is, in essence, to reject Jesus.”

Would you say it is a common view among evangelicals that the *belief itself* in universalism warrants Hell? That even if the person believes Jesus saves, the additional belief of universalism amounts to rejecting him? (This could just be Bell’s hyperbole regarding the word “essentially”.) Can one be a Christian and believe that all will be saved?

I was wondering what your take on the matter might be.

Sincerest,

Matt

Hi Matt,

Quite obviously you’ve read a sufficient amount of my writing to guess that flattery was a good gamble to get a response from me. I thank you all the same, and I’m being truthful when I say that I’m humbled not only by your kind words but more so by your trust in me with such a significant question.

I think a word like “trust” is absolutely the right to use in this matter for the stakes explicit in a doctrine like the— supposed— doctrine of eternal conscious torment are too high for the sort of callous, unthinking certitude with which many Christians comment on it. On the hand, I know far too many liberals who attempt to posit universal salvation by resorting to sloppy analogies about spokes on a wheel. “Different religions are just different paths to the same destination,” is a mantra many are conditioned by the culture to repeat. Seldom do such people realize the presumption behind what they surely take to be a humble position; after all, just as only God can reveal God, only God can know which paths might produce the destination that is God. Likewise those who want to iron over differences between the faiths of Abraham by dismissing them altogether with “We all worship the same God, right?” We may indeed all worship the same God, but such a dismissal ignores that the central tension in scripture is not over having or not having a generalized belief in God but in whether or not God’s People worship God rightly.

Any account of universal salvation, therefore, must arise not from the secular impulse to undo what God does at Babel and eliminate difference, for the difference God does at Babel is the way in which God blesses the world.

The elimination of difference, Babel teaches us, comes from our sinful inclination to be gods in God’s stead. Often I think Christians of a certain vintage insist upon the notion of eternal hell because those Christians adovcating for universal salvation do so in a way that seems insufficiently Christian; that is, Christianity seems incidental to the sentiments that prompt their universalism.

Incidentally, I believe this is also why so many liberal Christians are unpersuasive to other Christians on LGBTQ issues. “Love and welcome for all,” for example, is a principle with which I concur, but it is a principle.

Principles, in principle, do not require a crucified Jew for you to discover them.

Any argument for universal salvation then must be one that emerges from the particular revelation given to us by God in Jesus Christ, and, frankly, the argument from those scriptures is much easier to execute than many brimstone-loving evangelicals seem to realize. Certainly there’s sufficient scriptural witness to disqualify any characterization of eternal conscious torment as an essential Christian belief. As Jesus tells Nicodemus, his coming comes from God’s love for the entire cosmos and what God desires is that all the world will be saved— the word there is healed— through him (Question: Does God get what God wants in the End? If not, wouldn’t what frustrates God’s eternal aim, by definition, be god?) In that Gospel, John makes explicit in his prologue and in his Easter account that the incarnation is God’s way of constituting a new creation not evacuating a faithful few from the old creation. The cosmic all-ness of Christ’s saving work is the thrust of Paul’s argument in Romans where even the unbelief of the Jews Paul attributes to God’s own doing: “God has consigned some to unbelief so that God may be merciful to all.” He puts it even plainer in Timothy: “Our savior God . . . intends that all human beings shall be saved and come to a full knowledge of the truth.”

Where hell is mentioned in the creeds, which, remember are the only means by which Christians evaluate who is and is not a legitimate believer, hell is mentioned because Christ harrowed it, rescuing the dead from former times from Sheol.

Even in Christ’s own parables—

Hell is never a realm that lies outside the realm of grace.

Whenever we separate the person and work of Christ, which an accomodated Church in Christendom is always tempted to do, we abstract discipleship (a life patterned after the person of Jesus) from faith (confession in the work of Christ), leaving “belief” to play an outsized role in how we conceive of what it means to be a Christian. Faith then becomes a work we do— when we don’t want to do the things that Jesus did— a work by which we merit salvation rather than a gift from God to sinners. Understand— this insistence on eternal conscious torment is ungracious all the way down. We’re the agents of it all. It turns Christianity into a religion of Law instead of Grace.

To answer your question, though, I’m not sure that I can answer your question. I don’t know how many evangelicals believe that belief in universalism itself warrants eternal conscious torment. If they do believe that believing all shall be saved is a surefire way not to be saved, I’m not sure what Bible they’re reading. Karl Barth, for instance, who was an evangelical, wrote that while the Bible does not permit us to conclude without qualification that all shall be saved, the Bible does exhort us to pray that all will be saved— because the salvation of all is God’s revealed will. Just as I’m not sure what Bible such evangelicals could be reading, I’m also unclear about what God they could worshipping.

Such dogmatic insistence behind belief in eternal conscious torment and the alleged justice that requires such a doctrine grates against the justice God reveals to us in crucifixion of God’s own self for the ungodly.

When it comes to questions of eternal punishment, we mustn’t let the world’s sin obscure the fact that Jesus, crucified for the ungodly, is the form God’s justice takes in the sinful world.

While I’m not sure how many evangelicals believe believing in universal salvation yields damnation, I do believe many evangelicals lack an helpful awareness that belief in universal salvation is more than a meager minority voice in the history of the Christian Church. There have been universalists as long as there have been Christians. In the first half the Church’s history, they were so numerous that Augustine had a sarcastic epithet for them (“the merciful-hearted”). The Church Father Gregory of Nyssa, whom Rob Bell basically ripped off, was one. He argued that since Adam and Eve were types who represented the entire human community whatever salvation meant it meant the redemption of all of humanity. You need not agree with Gregory but to suggest Gregory is not a Christian seems to indicate the plot has gotten lost.

As David Bentely Hart notes in his forthcoming book:

“[universalists] cherished the same scriptures as other Christians, worshipped in the same basilicas, lived the same sacramental lives. They even believed in hell, though not in its eternity; to them, hell was the fire of purification described by the Apostle Paul in the third chap- ter of 1 Corinthians, the healing assault of unyielding divine love upon obdurate souls, one that will save even those who in this life prove unworthy of heaven by burning away every last vestige of their wicked deeds.”

Back to your question— Would you say it is a common view among evangelicals… that even if the person believes Jesus saves, the additional belief of universalism amounts to rejecting him?

Again, I’m not sure what evangelicals believe about the dangers of believing in universalism, but if any do, then we should pray for them. How sad to think that it’s possible for Christians in America to have turned the wine of the Gospel into water.

A Gospel where, in the End, sinners get what they deserve— that’s water not wine.

It’s religion; it’s not the justification of the ungodly.

A Gospel where those who err by believing too much in the triumphant mercy of God will be banished to eternal outer darkness— that’s worse than the plain old water of religion. What’s more, it puts the right-believers outside the party standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the older brother pissed off at the prodigality of the Father’s grace. A week from Good Friday we’d do well to remember it was such begrudgers who pushed God out of the world on a cross.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 10, 2019

If Jesus is Not Political, Why was Jesus Not Stoned to Death?

Palm Sunday, the most political Sunday of the liturgical year is upon us. Of course, I realize such an assertion is anything but obvious to a good number of Christians. Jesus came to die for our sin; Christianity isn’t about politics, surely some of you are thinking. If it’s indeed the case that Christianity is about religion and not politics, that Christ died as a sacrifice for sinners not as a victim of the Power of Sin, then why in the hell does Jesus die on a cross?

If the death of Jesus is a religious death, then why is not stoned to death?

The late Dominican theologian and philosopher, Herbert McCabe, cautions against any understandings of the cross that are exclusively religious or theological. The very fact that Jesus was crucified suggests the familiar cliche that ‘God willed Jesus to die for our sin’ is not nearly complex enough nor this worldly. McCabe writes in God Matters:

“Some creeds go out of their way to emphasize the sheer vulgar historicality of the cross by dating it: ‘He was put to death under Pontius Pilate.’

One word used, ‘crucified,’ does suggest an interpretation of the affair.

Yet [that word] ‘crucified’ is precisely not a religious interpretation but a political one.

If only Jesus had been stoned to death that would have at least put the thing in a religious context- this was the kind of thing you did to prophets.

Nobody was ever crucified for anything to do with religion.Moreover the reference to Pontius Pilate doesn’t only date the business but also makes it clear that it was the Roman occupying forces that killed Jesus- and they obviously were not interested in religious matters as such. All they cared about was preserving law and order and protecting the exploiters of the Jewish people.

It all goes to show that if we have some theological theory [about the cross] we should be very careful.

This historical article of the creed isn’t just an oddity. This oddity is the very center of our faith.It is the insertion of this bald empirical historical fact that makes the creed a Christian creed, that gives it the proper Christian flavor. It is because of this vulgar fact stuck in the center of our faith that however ecumenical we may feel towards the Buddhists, say, and however fascinating the latest guru may be, Christianity is something quite different.

Christianity isn’t rooted in religious experiences or transcendental meditation or the existential commitment of the self. It is rooted in a political murder committed by security forces in occupied Jerusalem around the year 30 AD…Before the crucifixion Jesus is presented with an impossible choice: the situation between himself and the authorities has become so polarized that he can get no further without conflict, without crushing the established powers.

If he is to found the Kingdom, the society of love, he must take coercive action. But this would be incompatible with his role as as meaning of the Kingdom. He sees his mission to be making the future present, communicating the kind of love that will be found among us only when the Kingdom is finally achieved.

And the Kingdom is incompatible with coercion.

I do not think that Jesus refrained from violent conflict because violence was wrong, but because it was incompatible with his mission, which was to be the future in the present.

Having chosen to be the meaning of the Kingdom rather than its founder Jesus’ death- his political execution- was inevitable.He had chosen to be a total failure. His death meant the absolute end his work. It was not as though his work was a theory, a doctrine that might be carried on in books or by word of mouth. His work was his presence, his communication of love.

In choosing failure out of faithfulness to his mission, Jesus expressed his trust that his mission was not just his own, that he was somehow sent.

In giving himself to the cross he handed everything over to the Father.

In raising Jesus from the dead, the Father responded…This is why Christians sat that what they mean by ‘God’ is he who raised Jesus from the dead, he who made sense of the senseless waste of the crucifixion.

And what Christians mean by ‘Christian’ are those people who proclaim that they belong to the future, that they take their meaning not from this corrupt and exploitative society but from the new world that is to come and that in a mysterious way already is.”

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 8, 2019

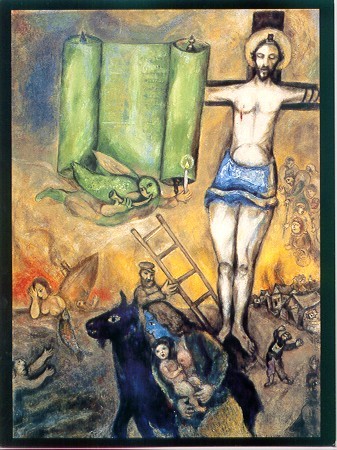

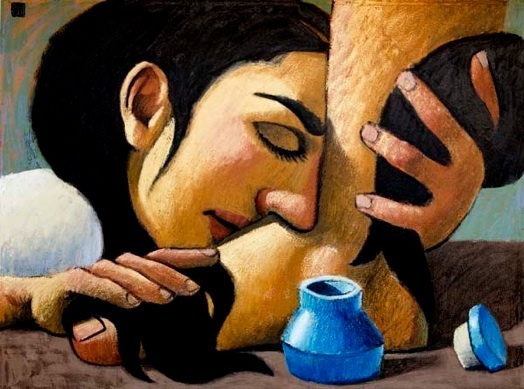

Virtue Signal

John 12.1-8

For God’s sake, don’t lie.

Admit it.

You think Judas is right.

Of course, if you’ve spent any time at all in church, then you already know that you’re not supposed to identify with Judas. Judas is the traitor. Judas is the villain. Judas is the Judas.

He’s the bastard who turns around right after today’s text to rat out Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, which according to the prophet Zechariah was about a day’s wage.

A day’s wage.

According to the Book of Exodus, thirty pieces of silver is the cost of an average slave.

Judas sells out the Son of God as though a slave.

So we know we’re not supposed to identify with Judas but, be honest now, we think Judas is right, or at the very least he’s reasonable. If you saw a line item in our church operating budget for nard you’d be PO’d too. In case you’re not a first century Mary Kay agent, nard was a perfume from the Himalayas. Amazon Prime still doesn’t deliver to Bethany so how this much nard ended up there is anyone’s guess. Who knows how Mary got her hands on it, but you can be sure this nard was not gained on the cheap. 300 denarii is what Judas guesses it would go for on the open market.

Just to help you locate your place in the story here today: 300 denarii was the rough equivalent to $45,000.00.

The nard cost Mary more than a Tesla Model 3.

Wanna come clean now?

You think Judas is right on the money about the money. For HimalayanObsession?! At that cost, it would be better to rub Jesus down with some $5.99 Old Spice and give the rest of the five figures worth to the poor.

Or, why not Axe Body Spray? For ten measley bucks she could spray some sexy on Jesus and then they’d still have approximately $44,990.00 for do-gooding.

And doing good is what it’s about, right?

After all, Matthew’s account of this anointing occurs right after Jesus lays down every liberal Methodist’s favorite parable— the one about clothing the naked, giving drink to the thirsty, feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, and visiting the prisoner. Judas has just heard Jesus drop the boom about eternal punishment so how can you blame Judas for wanting to get reckoned a sheep rather than goat?

If we’re honest, it’s hard for us to see what Judas got wrong.

Christians ought to be on the side of the poor. If Christians fail to capture the cultured despisers’ respect and imagination isn’t it largely because of our inability to live lives that correspond to Christ and his teachings (perhaps especially his teaching about the poor)?

What’s more, isn’t Judas’ the better strategy for the Church to survive in a pagan nation like America? After all, Americans may not believe that Jesus is Lord of anything but pious hearts, but they at least believe we probably ought to help the poor.

Isn’t Judas’ the smarter strategy in a secular age? Surely, serving the poor is a way for us as Christians to win friends and influence people. And while we’re truth-telling, let’s be honest. Believing what Christians are required to believe is no easy thing. Believing that the infinite took flesh in Mary’s finite womb, believing that three days dead Christ was dead no more, believing that he now and forevermore sits at the right hand of the Father— believing what Christians believe is no easy matter.

We’re not even sure what it means to say someone sits at the Father’s right hand.

Handouts to the hungry though? Let’s be honest. It’s just easier. Helping the less fortunate— it makes sense, which likely explains why it’s not distinctively Christian.

If you’ve seen Monty Python’s Life of Brian then you already know. In first century Israel, “poor” was a political category. The poor weren’t lazy or left behind. The poor were the oppressed. Money’s tight when you’ve got to foot the bill for your own military occupation— that’s why the Christmas story kicks off with a census.

Just read your Old Testament if you don’t believe me— it’s not a minor theme in scripture— the poor were poor because they were oppressed.

If you don’t understand the relationship between poverty and oppression you won’t understand Palm Sunday. You won’t understand how the Messiah they anticipate with shouts of hosanna produces first their disappointment and then their betrayal when the “Messiah” they get turns out to be the Messiah named Jesus.

Judas isn’t simply suggesting that this down payment’s worth of perfume should’ve been shared with the poor; he’s arguing that it’d be better spent on the cause.

Judas isn’t griping that they should’ve given the money to feed the poor.

He’s saying they should’ve used the money to free them.

To free the poor. To liberate the oppressed. Judas’s point is not just about charity. Judas’ point is also about justice. After all, he’s named for Israel’s most famous armed revolutionary.

Like today, Judas’ language about the poor is political language. It’s a campaign contribution’s worth of cash Judas watches Mary rub into Jesus’ calloused feet.

“Why was this nard not sold for almost fifty grand and the money given to the Democratic National Committee?” That’s a better way to hear what Judas says.

“Why was this perfume not sold and the money donated to Make Israel Great Again?” Is another way to hear him.

“What’s she doing? What a waste! Don’t you people know your Micah 6.8?! Do you know the kind of change we could make with that much cash?”

Even if we’re too chicken to admit it, Judas makes sense to us. But we’re right to pretend otherwise. Think about it— Judas is sitting at the supper table with Lazarus, a guy who’d been dead for four days.

Judas had watched graveside as Jesus called Lazarus out of the tomb, stinking with death and tripping over his burial clothes he was so surprised. In fact, Jesus had commanded him to be dead no longer: “Lazarus, come out!”

From dust he came and to dust he returned and then he returned again.

Now Judas is eating with the guy who was wormfood a few days ago, but as soon as Judas sees Mary pull out some some five figure Chanel No. 5 he’s back to thinking in terms of scarcity.

Which puts Judas (and thus, puts us) in the same camp as Caiphas—another name we know better than to identify.

In the text just before today’s text, John tells us that a crowd of Jews, having witnessed Jesus speak Lazarus forth from the dead, began “believing into Jesus.”

Some of these bystanders, John says, went and tattled on Jesus to the Pharisees and the Pharisees went and tattled to the chief priests and the chief priests went and tattled to the Chief Priest, Caiphas.

And how does Caiphas respond?

“If we let him go on like this,” Caiphas worries, “everyone will believe into him, and the Romans will come and destroy our nation.”

Sit with that for a second—

When the chief religious leaders of God’s people hear about Jesus’ power over the Power of Death, their immediate worry is not religious. It’s political.

Like we do, Caiphus had been towing the God and Country line, but as soon as the Living God shows up our true colors come out.

When Caiphas hears Christ can raise the dead, he doesn’t cripe about commandments. He worries about the two things over which you most worry too.

Currency.

And country.

Jesus is hiding out here in Bethany because just after Jesus produces Lazarus alive from the tomb, Caiphas plots to kill Jesus because Caiphas worries that Christ’s power over the Power of Death will upset the political arrangement of the powers-that-be.

Don’t forget:

This is the same Caiphas who on Good Friday will condemn Jesus to a cross on a charge of blasphemy while pledging to Pontius Pilate what exactly? He says what no Jew should ever say: “We have no King but Caesar.”

But since Messiah and King and Caesar all name in different languages the same word, Caiphas basically says “We have no Messiah but the King you call Caesar.” That’s where the Old Testament grinds to halt. It ends there with “We have no Messiah but Caesar.“ Christ’s passion is the price to secure Caiphas’ political promise to Pilate.

“Forty-five grand! We could’ve donated that money to MoveOn.org— think of the justice work we could do with that much money.” Judas says.

“Power over Death? But only Death makes our economy of scarcity possible. Resurrection, it’ll ruin the nation.” Says Caiphas.

You see— Judas and Caiphas, their failure is not primarily one of faithfulness. Their failure is a failure of imagination. Their failure is a failure of political imagination.

In order to see their failure as a failure of political imagination, however, we must first swallow our squeamishness about what Jesus says to Judas. Even if we’re too cowardly to admit we think Judas is right, we should at least be able to acknowledge that Jesus’ response to Judas embarrasses us. We wish Jesus had not said what Jesus says: “You’ll always have the poor with you; you don’t always have me.”

Just try that verse out on a woke, unbelieving Bernie supporter and see how they react. Talk about religion as the opiate of the people. What Jesus says to Judas seems to legitimate the sort of apathetic, pie-in-the-sky Christianity for which non-Christians critique Christians.

Maybe it’s because “You’ll always have the poor with you; you don’t always have me” embarrases us that we seldom stop to notice the fact that the one who said “You’ll always have the poor with you; you don’t always have me” is himself poor.

Jesus is poor.

Jesus is oppressed.

And very soon, Jesus will be the naked without any clothes. Jesus will be the parched who’s given gall. Jesus will be the stranger shunned. Jesus will be the prisoner abandoned by all but his mother and a single disciple. Surrounded by goats, they’ll be the only sheep at his side for the Last Judgement that is his Cross.

Don’t you see?

This is the point of it all— this is why Caiphus plots to kill him.

We think Judas is right, but we miss how right Caiphas really is.

Jesus is a threat to our politics.

Jesus does intend to end the world as we know it.

Mary upends our categories of helping the poor and the oppressed by lavishing a Mercedes C-class worth of money on a single poor person (who also happens to be the incarnate God). And Jesus praises her for it. It’s a good and joyful thing, always and everywhere, to do what she did.

Judas has got his mind stuck in the grave— he still thinks that change-making comes in terms of charity and campaign contributions, but Mary’s response to Jesus’ power over the Power of Death is to shower two-thirds of our entire mission budget on a solitary poor man living on borrowed time. Judas lacks Mary’s imagination.

Only when you understand what Mary understands will you understand what Jesus means when he says to Judas that we will not always have Jesus with us bodily but we will always have the poor with us.

Jesus is not implying that we should be resigned to the way of the world. On the contrary, we will always have the poor with us because the Church, the Body of Christ, is the People God has put in the world who know, by the sacrament of the resurrection, that the poor and the prisoner, the naked and the shunned, are to celebrated.

The Church is the People God has put in the world who know that we can afford to love the poor with lavishment because Christ is a gift that can never be used up. So of course we’ll always have the poor with us. Because the Church is the Body of him who is poor. We will always have the poor with us because the Body of Christ is for them.

“Leave her alone,” the poor man said to Judas, “she bought it [she bought it—for $45K!] for me.”

“She’s done the better thing,” the poor man adds in Matthew’s account.

Jesus praises Mary because Mary understands that Jesus makes a different politics possible. To put a finer point on it, Mary understands that she-and-her-nard constitutes the different politics which God has made possible in the world in Jesus.

Karl Barth, the theologian on whom I cut my teeth and who remains my north star, wrote:

“Whenever Christians use a construction like Christianity and Politics they open the door to every devil.”

Barth liked to point out how when the devil temps Christ in the wilderness by offering him the governments of this world the implication is that the governments of this world are the devil’s to give. They belong to him.

Barth, who was one of the only German Christians to stand up against Hitler’s Nazi regime, was not being hyperbolic.

“Whenever Christians use a construction like Christianity—and—Politics they open the door to every devil.”

It’s the and there that’s problematic. Just as soon as the church begins to ponder how its Christianity can inform politics, Barth argued, you can be sure the church has lost the plot. Such a church might be a church of great sincerity and zeal. Such a church might be a church of fervent devotion and good works of charity. Nonetheless, such a church will be a church that’s failed to understand that it is the way God has chosen to love and redeem the world.

Whenever we talk about Christianity and Politics, we risk forgetting that the way God has chosen to heal his creation is through his particular People— that’s a promise that goes all the way back to Abraham.

The way God has chosen to heal his creation his through the witness of his People.

Not the House or the Senate. Not POTUS or SCOTUS. Not with bills or billboards or hashtags. Not through political policy. But his People. The Church. The Body of Christ, sent by the Spirit, is God’s virtue signal; that is to say, the Church doesn’t have a politics the Church is a politics.

I’m sure right about now that some of you (if not all of you) are thinking Well, gee Jason, that sounds nice but what in the hell do you mean“The Church doesn’t have a politics. The Church is a politics?”

I’m glad you asked.

Yesterday afternoon we celebrated a Service of Death and Resurrection for a man here in the community, Gordon.

Gordon was a Vietnam vet. The cancer that killed him likely came from Agent Orange that killed others. A couple of days before he died, he called me to his bedside. In addition to wanting to profess that Jesus is Lord and give to Christ what remained of his life, Gordon also wanted to confess his sins.

“I want to confess,” he told me staring at the ceiling, “what I had to do in the war— it was necessary, but it was still sin.”

Think about it—

He was dying. He didn’t know how quick. Time was a precious, valueable commodity to him. Time was a gift, and Gordon wanted to give it, to lavish it— some would say waste it— by giving his confession to Christ.

In a culture that ships our soldiers off to do what is necessary and then, when they return home, we insist that they not tell us about what we’ve asked them to do, Gordon’s confession— what the Church calls the care of souls— that’s a politics.

It’s how God has chosen to care for the world.

During the funeral service, Gordon’s son spoke candidly about his often difficult sometimes estranged relationship with his father.

In a culture of sentimentality and pretense, the sort of truth-telling that this sanctuary makes possible— that’s a politics.

Later this afternoon, a group from church will go up to Sleepy Hollow Nursing Home to worship with elderly residents who may not be able to hear it or comprehend it. In a culture like ours that is determined to get out of life alive— a culture that worships at the altar of youth and achievement— the old are very often cloistered away and cast-off.

It’s a simple thing some of you will do at Sleepy Hollow, offering them prayer and presence and touch. But

But make no mistake, it’s a politics.

A while ago, I read a story in the paper about the California Prison Hospice Program. The unintended consequence of stiff prison sentences doled out in the ‘80’s and ‘90’s is that now many penitentieries must double as nursing homes.

Already underfunded, many prison systems have recruited and trained convicts to serve as hospice workers to care for and accompany aging inmates as they die of cancer and other causes.

It might not surprise you to hear most of the prisoners who volunteer to care for the dying are Christians.

“It’s what God’s given us the opportunity to do, to pour out our love on them” one prisoner— guilty of a gang bang in his youth— told the New York Times.

It might not surprise you to hear that most of the hospice workers are Christians, but it might surprise you to hear that of the hundreds of prisoners who’ve worked caring for the dying and later been released not one of them has returned to prison.

They have a recidivism rate of 0%.

In a culture where even Democrats and Republicans can agree our criminal justice system is broken, a simple unimpressive act, Christian care for the dying…zero percent— that’s a politics.

At the end, the Times article unintentionally echoes St. Paul:

“Within the walls of the prison hospice, all the invisible boundaries of the world have fallen down. Black men give meal trays to [dying] white men with swastikas tattooed on their faces, Crips play cards with Bloods, and a terminal Latino with cirrhosis gets his hair cut by an Asian with whom he previously wouldn’t have peaceably shared a cellblock.”

The way God has chosen to heal the world is the Church— that’s what we forget whenever we argue about the Church and Politics.

We’re the nard that God has purchased at great cost to himself to lavish Christ upon the dying world.

You see—

It’s not that grace— what God has done for us in Jesus Christ— makes what we do as Christians incidental or unimportant.

It’s that what we do as Christians should be unintelligible— an expensive waste, even— if God has not raised Jesus Christ from the dead.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 5, 2019

Episode #202– David Zahl: Seculosity

Calvin said the human heart is an idol factory. Augustine said our hearts are restless until they find rest in God. DZ of Mockingbird Ministries and the author of the new book, Seculosity, says we’re more religious than ever before we’re church “in church” in different ways.

Calvin said the human heart is an idol factory. Augustine said our hearts are restless until they find rest in God. DZ of Mockingbird Ministries and the author of the new book, Seculosity, says we’re more religious than ever before we’re church “in church” in different ways.

Love, politics, parenting, technology, fitness are not secular alternatives to religion. They are, says DZ, secular ways of being religious. We’re never not in church now says David, but because the Church of Politics or Soul Cycle are inherently religions of Law, we’re increasingly exhausted, self-righteous, and cruel. We’er searching for “enoughness” from gods that, without the promise of grace, cannot bestow it.

Check out his work at www.mbird.com and grab a copy of his book over at Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

And after you do David a solid, pay it forward by helping us out at the podcast to keep delivering you conversations about faith without using stained-glass language. Go to our website (www.crackersandgrapejuice.com) and click on “Support the Show” to become a patreon for chump change.

Follow @cmsvoteup

April 3, 2019

“Those who want to save their life will WASTE it”

For our Wednesday evening eucharist service, I decided to write a homily on Matthew’s version of the Sunday Gospel lection:

For our Wednesday evening eucharist service, I decided to write a homily on Matthew’s version of the Sunday Gospel lection:

“For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it,” Jesus tells his disciples, but specifically Peter, just after calling Peter “Satan” for tempting Jesus with a fate other than cruciform destiny.

Perhaps because Jesus’ statement about our needing to lose our lives in order to gain them occurs within the context of Peter balking at the notion of a crucified Messiah we mishear Jesus as suggesting that we too must seek a cross if the Kingdom is to be added unto us.

But the Risen Christ is no nihilist. When Jesus says we must lose our lives to gain them, he’s not recruiting kamikaze Kingdom warriors, for the word “lose” in Matthew 16 is the same word Matthew uses just after Jesus tells us about the sheep and the goats.

The word “lose” is the same word in Greek for “waste.”

ἡ ἀπώλεια αὕτη

apoleia

“For those who want to save their life will waste it, and those who waste their life for my sake will find it.”

Matthew uses that same word ‘waste” a few chapters later when Jesus visits the house of Simon the Leper for supper— Jesus might as well ask the Pharisees and chief priests to kill him.

Two nights before Passover, two nights before he dies, Jesus goes to Simon’s house for dinner. They’re eating dessert and drinking coffee when in walks a woman. She doesn’t have a name but she does have a crystal jar filled with expensive oil— about $45,000 worth.

This woman, she break the jar and she pours the oil over Jesus’ head and body.

Just like the psalm about the good shepherd in the valley of death— just like King David, whose kingdom God promised would be forever— she anoints him. She anoints him for his death, for his cross will be his enthronment, thorns his crown, and the jeers of onlookers his acclamation.

And Jesus, he praises her for not holding back, for sparing no cost in pouring out her love on him.

Meanwhile the disciples look on in anger, and all they can do is grumble over all the “good” they could have done with that much money. I mean, don’t forget Jesus had just laid every liberal Methodist’s favorite parable on them— the one about the sheep and the goats.

So here, watching this woman who shelled out a year’s worth of wages for perfume, they virtue signal, estimating the number of hungry that could’ve been fed, the naked who could’ve been clothed, the poor they could’ve served.

If she hadn’t wasted it.

Yet Jesus praises her.

The disciples look at her and they get angry at the waste. Jesus looks at her and sees a holy waste. He praises her for lavishing love and devotion on him, who—don’t forget— is poor and will very soon be the naked without clothes, the thirsty who’s given gall, the prisoner abandoned by all but his mother and a single disciple.

Lose.

Waste.

You see when Jesus tells us we need to lose our lives to gain a life in the Kingdom, he’s not talking about crosses. He’s talking about something even more reckless. He’s recommending the example of this woman— he’s urging us to lavish love and devotion— to spare no cost— on him.

This woman at the leper’s house knows that Jesus is not a means to some other end. Rather devotion to Jesus— worship of him is a good in and of itself.

An economy that the world cannot help but see as a waste and which ironically may lead the world in its economy to crucify us.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 28, 2019

You Must Be Born Anothen

For the Wednesdays of Lent we’re doing an evening eucharist service where each week I preach a homily on one of the Comfortable Words. The Comfortable Words are a collection of promises from the New Testament, compiled by Thomas Cranmer for the Book of Common Prayer. Cranmer wanted to guarrantee that having confessed our sin and been confronted with the demands of God’s Law God’s people never left a service of Word and Table without having heard the promise of the Gospel.

For the Wednesdays of Lent we’re doing an evening eucharist service where each week I preach a homily on one of the Comfortable Words. The Comfortable Words are a collection of promises from the New Testament, compiled by Thomas Cranmer for the Book of Common Prayer. Cranmer wanted to guarrantee that having confessed our sin and been confronted with the demands of God’s Law God’s people never left a service of Word and Table without having heard the promise of the Gospel.

Here’s my homily on John 3…

“If you want to see the Kingdom of God, you must be born anothen.’

You must be born again. Or- You must be born from above. Jesus only ever says “You must be born anothen” to Nicodemus. No one else. Except- That you in “You must be born again” is plural. It’s “You all must be born again.”

Nicodemus comes to Jesus not as a seeker but as a representative. Of his people. Nicodemus approaches Jesus armed with the plural. “Teacher, we know…” he says. And Jesus answers with “You all…” We are in that you. Here with Nicodemus, it’s the only scene in all of John’s Gospel where Jesus mentions the Kingdom of God.

Being born anothen- It’s something God does; it’s not something we do. Jesus couldn’t have put it plainer: “The wind— the Holy Spirit— blows where it chooses to blow. You can’t know where it comes from or where it goes.”

Being born anothen, Jesus says, it cannot be achieved by people like you or orchestrated by preachers like me. You didn’t contribute anything to your first birth from your mother’s womb, so why would you think you could contribute anything to your new birth?

That’s what Jesus means by “What is born of flesh is flesh…” Flesh in John’s Gospel is shorthand for our INCAPACITY for God. What is flesh, i.e. you and me, is incapable of coming to God. You can’t get born again; it’s something you’re given. Being born again, it’s not something we do. It’s something God does. But Jesus says it’s something that must happen to us. Even if God is responsible for our being born again, Jesus says it black and white in red letters: It’s required if we’re to see the Kingdom of God.

———————-

Maybe the problem is that we pay too much attention to what Jesus says. We get so hung up on what Jesus says to Nicodemus in the dark of night that we close our eyes to what John tries to show us.

This Gospel of Jesus Christ, says John in his prologue, is about the arrival of a New Creation. And next, right here in John 3, Jesus tells Nicodemus and you all that in order to see the Kingdom of God you’re going to have to become a new creation too. You’re going to have to be born anothen. Again. From above. By water and the spirit.

Skip ahead.

To Good Friday, the sixth day of the week, the day of that first week in Genesis when God declares “Behold, mankind made in our image.”

And what does John show you? Jesus, beaten and flogged and spat upon, wearing a crown of thorns twisted into his scalp and arrayed with a purple robe, next to Pontius Pilate. And what does Pilate say?

“Behold, the adamah.”

And later on that sixth day, as Jesus dies on a cross, what does John show you?

Jesus giving up his spirit, commending his holy spirit. And then, John shows you Jesus’ executioners, attempting to hasten his death they spear Jesus in his side and what does John show you? Water rushing out of Jesus’ wounded side. Water pouring out onto those executioners and betraying bystanders, pouring out- in other words- onto sinful humanity.

Water and the spirit, the sixth day.

And then Saturday, the seventh day of the week, the day of that first week in Genesis when God rests in the Garden from his creative work- what does John show you? Jesus being laid to rest in a garden tomb.

Then Easter, the first day of the week. And having been raised from the grave, John shows you a tear-stained Mary mistaking Jesus, as naked and unashamed as Adam before the Fall, for the what? For the gardener, what Adam was always intended to be.

Later that Easter day, John shows you the disciples hiding behind locked doors. This New Adam comes to them from the garden grave and like a mighty, rushing wind he breathes on them. “Receive the Holy Spirit” he says to them. Water, Spirit, Wind blowing where the Spirit wills, the first day. He breathes on them. Just as God in the first garden takes the adamah, the soil of the earth, breathes into it the breath of life and brings forth Adam, brings forth life, this New Adam takes the grime of these disciples’ fear and failure, their sin and sorrow, and he breathes upon them the Holy Spirit, the breath of life.

They’re made new again. Anothen.

And on that same first day John shows you Jesus telling these disciples for the very first time, in his Gospel, that his Father in Heaven, is their Father too. They’re now the Father’s children in their own right.

The Father’s Kingdom is theirs to enter and inherit.

And it’s ours.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 27, 2019

Disability and the Good Life— Christian Century Article

Here’s a long review I wrote for the latest issue of the ChristianCentury, out today:

Here’s a long review I wrote for the latest issue of the ChristianCentury, out today:

Crippled Grace: Disability, Virtue Ethics, and the Good Life.

By Shane Clifton. Baylor University Press, 285 pp., $49.95.

One summer Sunday this year, after the last few worshippers trickled through my line to receive the sacrament, their hands outstretched like beggars, I carried the body and blood of Christ to Mary. In the early stages of multiple sclerosis, she sat behind the back pew in her wheelchair next to her husband James.

I broke off a piece of bread and placed it between her clenched fingers. “The body of Christ broken for you, Mary,” I whispered. She chewed slowly, as though she knew better than us that her life depended upon what lay within it. James waited calmly. I watched the clock nervously. When she finally swallowed, James and I guided the cup to her lips. “The blood of Christ poured out for you, honey.” He’d stolen my line. Some of the wine dribbled out of her mouth and onto her blouse. Unwrapping the cloth from the stem of the chalice, he wiped her face clean and blotted the stain on her shirt.

“I admire you for the way you are with her, your patience and tenderness,” I said to James.

He looked puzzled and replied, “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“Our marriage has never been better,” Mary slurred with a smile. Chastened, I carried the chalice and the crust back to the altar table as the congregation finished singing “O love, how deep, how broad, how high.”

It reveals my own handicapped Christianity that I assumed Mary’s illness and consequent disability was a hardship to bear rather than the labor pains through which she and James were becoming new creations. “There but for the grace of God go I,” we say in stubborn denial that one day we may indeed find ourselves as someone like Mary—and oblivious to the possibility that, finding ourselves like her, we might discover it’s not the tragedy we suppose but is instead an occasion for grace.

My particular surprise at Mary and James’s experience of grace stems, Shane Clifton argues in Crippled Grace, from our general reluctance to come out of the closet and live openly—vulnerably—as finite, contingent creatures. The author of Husbands Should Not Break, Clifton teaches theology at Alphacrucis College in Australia. Having been a teacher of the church’s virtue ethics tradition, from Thomas Aquinas to Alasdair MacIntyre, Clifton became a student of it after he suffered an injury while jumping a bicycle. It rendered him a complete (C5) quadriplegic.

Depression and despair followed seven months in the hospital for Clifton, but eventually his dark night of the soul yielded to happiness. Or rather, his injury and resulting disability led him to find happiness under the new conditions of his life. The good life is discoverable, Clifton shows, not in spite of his struggles with sexual function as “a crip” nor in spite of his daily “dealings with the messiness of piss and poo.” The good life opens up to him in the midst of them—because of them.

To be disabled, Clifton observes, is to be in a near constant state of dependency upon others. Such dependency usually strikes us as an ordeal to be avoided at all costs. Says Clifton: “We hear of a person rendered a quadriplegic, and we think to ourselves ‘They’d be better off dead.’ So we say to our loved ones, ‘If that ever happens to me, turn off the machine.’” As common as such assumptions may be, Christianly-speaking they are incoherent. If that ever happens to me is unintelligible as Christian grammar since the content of Christian revelation discloses that we are dependent, contingent creatures. Those who are disabled cannot help but make visible the truth that the rest of us, crippled by fear or pride, prefer to hide: we are not in control of our lives.

The imagodei, we too often forget, is firstly not a resemblance to the Creator; it’s the confession that we are created. As creatures, we are dependent upon our Creator, contingent in the fragile world God has wrought. In contrast to Descartes, who posited the human as primarily a thinking thing, Clifton asserts that “to be human is to be subject to the vulnerabilities of finite life.” This view offers a fresh perspective on what constitutes the human creature, since dependence and vulnerability are largely absent categories in moral philosophy. It also allows Clifton to conceive of disability in terms contrary to the prevailing notions about it. For Clifton, spinal cord injury doesn’t mark the impoverishment of his life as a human creature. Quadriplegia proves instead to be the crucible through which he becomes more human. Spinal cord injury becomes the occasion for Clifton to discover the truth of Christian speech: weakness is not the opposite of strength.

Nor are disability, happiness, and faith contradictory terms. Clifton uses his own experience as well as the testimonies of others with disabilities to bring virtue philosophy and disability studies into conversation with Christian theology. The layered approach, marrying first-person memoir with multiple disciplines, recalls the work of another virtue ethicist, Stanley Hauerwas. Like Hauerwas’ own work, Crippled Grace has wide-ranging implications beyond the specificity of its topic. This is not a book about disability. It’s a book about mortality—about how those of us who came from the dust conceive of happiness before we return to it.

If what constitutes us as human creatures is contingency amidst the vulnerabilities of finite life, then disability is not a specific subset of human life. It is, as Clifton writes, “symbolic of the human condition.” Disability is a lens through which all of us can understand the good life.

The way the church engages people with disabilities is often analogous to the way the church engages people living in poverty through short-term mission projects. They become the means by which we or our children learn to count our blessings and to be grateful for our lives. Frequently people with disabilities are considered problems for the church to solve in terms of facilities and accommodations. Or they’re occasions for self-congratulation when we successfully welcome and include them. Or people with disabilities become our source material for lessons about dealing with adversity, what Clifton calls “inspiration porn.”

CrippledGrace thrusts a very different conversation upon the church. It argues for the possibility that disabled people possess a happiness, hewed by hardship, that the abled, in their avoidance of vulnerability, have yet to countenance much less attain.

Clifton begins the book in the same way his experience of disability began: with an attempt to make sense of suffering and the problem of pain. His experience as a sufferer thrusts him into a community of sufferers where the traditional theodicy question takes on surprising qualifications. “Why is there suffering in the world?” becomes a more ambivalent question when you discover, as Clifton did both personally and in his reading about disability, that many quadriplegics report that they would not trade their crippled life for another. The experience of disability, Clifton found, has enriched many people’s lives as “the catalyst for self-discovery.” That good can from an experience of suffering like quadriplegia does not justify or excuse God, Clifton rightly concedes. However, that good can and does come from an experience of suffering—even from an experience of suffering like quadriplegia—should give us pause before we posture ourselves like Job to rage against the mysteries of existence. The questions of theodicy we ask out of empathy with disabled people may inadvertently do sufferers great harm, tacitly dismissing the happiness they have found through the harrowing of their suffering. What for many of us is an imponderable privation in God’s good creation is simultaneously the means by which some of God’s impaired creatures discover the good life.

Clifton understands his own accident matter-of-factly as “a contingent event that is part and parcel for what it means to be a creature of the earth.” Following MacIntyre, Clifton assumes that vulnerability, affliction, and dependency are not so much mysteries to be plumbed as they are facts of the human condition. Precisely because they are facts of the human condition, they are corollaries for any account of human flourishing. The givenness of vulnerability, affliction, and dependency in a world of contingency is the necessary condition for the balance Clifton achieves as he explores the virtues in light of disability.

Virtue especially arises, he suggests, as a response to hardship. Therefore, the very vulnerability we lament and avoid as contingent creatures is ironically the ground necessary for us to find happiness. Those who are disabled cannot avoid the kind of dependency that the abled so skillfully avoid. This reality gives disabled people a particular and acute perspective on what the virtue tradition teaches about the good life.

Friendships, for example, are central to human flourishing. People who are severely disabled, Clifton notes, literally cannot negotiate their day-to-day lives without relying upon the care and compassion of friends. Moreover, intimacy and mutual vulnerability constitute the fruitful friendships we call marriage. The struggles and shame, acceptance and eroticism that many disabled people experience under the covers with their partners gives them a particular wisdom about intimacy and mutual vulnerability.

If nothing else, Clifton convinces me that people who are disabled have much to teach the church. If humility and patience are virtues, then there is no catechesis quite like the daily letting go that comes with relying on others to move you, feed you, and clean you. Luther said that the Christian life is a constant return to one’s baptism in the sense that it involves a daily dying to self. Clifton’s account of the daily dependency of disability puts skin on Luther’s claim. The dependency of those who are disabled, counterintuitively, can be empowering—for grace is the power of God that perfects our broken nature.

Happiness, Clifton shows, is not achieved so much as discovered. Happiness is the reward happened upon by those who do not avoid our human fragility but embrace it, daring to live as vulnerably as “those who need a push” in the wheelchair. Hauerwas jokes that “a God who doesn’t tell us what to do with our pots, pans, and genitals isn’t a God worthy of our worship.” Clifton ups the ante by demonstrating that those who live vulnerably—requiring others’ help with the doing of their pots, pans, genitals, and more—just may be the mosthuman of God’s creatures.

The dependency that is the day-to-day given of disabled people is also grist for the making of happiness. The good life that emerges from disability is necessarily a shared life. A disabled person’s stories are necessarily stories that include others, notably those upon whom the person depends.

Although I am not disabled, I live with an incurable cancer. I know firsthand as a patient what I’ve learned secondhand as a pastor: the partners of the afflicted are afflicted too. Caregivers bear a unique burden, and it’s one that is often harder to suffer. Opportunities to grieve can be spare amid the daily demands of care. It’s one thing to lament your own lot in life. It’s quite another more complicated, guilt-inducing thing to mourn the life you’ll no longer have because of the affliction that comes to your contingent spouse. CrippledGrace would be a fuller book, I think, if it included more testimony from the partners with whom disabled people are discovering the good life. I’ve got a vested interest, I suppose, but I’d like to hear the spouses of disabled people echo that they too would not trade their life for another.

This is a minor critique that should not distract from how upending Clifton’s work is. My takeaways were greater than I anticipated when I first cracked open the cover. I expected to close the book with a better understanding of how I should serve people like Mary, the disabled woman in my congregation. Instead I walked away convinced that my congregation might be more fully Christ’s own broken body were we to listen to Mary about life as it is lived in her dependent body. By highlighting the vantage point disabled people have on the virtues, CrippledGrace imbues people with disabilities with an agency and a (non-patronizing) spiritual wisdom that is not only unique to them but is largely absent from how they are typically regarded.

By examining the good life through the lens of disability, Cliftonexposes just how fraught are terms like disability and handicapped. Both terms betraythe extent to which we are captured by goods that are not the Christian virtues. They designate that certain people cannot perform certain skills—namely, doing and producing things for the marketplace—as well as other people can.

But Christianly speaking, how is this a disadvantage, much less one that should determine how we understand a person? People who are disabled are not impaired from—and may be especially equipped for—extending forgiveness, expressing gratitude, offering hospitality to a stranger, showing kindness, giving grace, absolving sins, and loving. Words make worlds, Christians believe, and words can also undo the world as God has disclosed it to us. The way we typically speak about disability shows that we’ve forgotten a Sunday School lesson Clifton ably teaches: weakness and vulnerability are God’s way of pouring out power.

I didn’t finish Clifton’s book with Mary on my mind. I closed Crippled Grace thinking instead of my two sons. They’re both active, able-bodied, teenage boys. As an aside in his conclusion, Clifton confesses his worry that he failed in the book to use disability as a particular metaphor for the fragility of life in general. It’s a striking moment of authorial vulnerability in a book about the importance of vulnerability. But he’s wrong. It’s a testament to the success of his endeavor that I came to the end of his work not thinking about the disabled people in my life but worrying about my boys, the world in which they’re about to make their way, and the church that will or will not be there for them.

If Clifton is correct, if to be human is to suffer the vulnerabilities of life in a contingent world and if happiness and all its composite virtues comes by how we handle those vulnerabilities, then the culture my sons are entering appears designed to make them unhappy and less than human. Seemingly at every turn, their world tempts them to filter all their imperfections through a social media sheen and to posture a public self that, in its premeditated artificiality, is the opposite of vulnerability. Increasingly, theirs is a world where relationships are virtual rather than vulnerable, online instead of incarnate. Such a world is not prepared to train my boys for the burden of being dependent on another; in fact, it expects them to have become “self-sufficient” by the time they bind their life to another by vows and rings. Worse perhaps, it’s a world where they’re encouraged to maximize every moment of their schedule to raise their score and perfect their permanent record. Such a world does not well form them to be ready with care when another becomes dependent upon them.

While Clifton’s account of authentic humanityleft me uneasy about the world that surrounds my children, it also lent me a clearer picture of the church needed in such a world. Clifton has convinced me that what my congregation needs is not wheelchair ramps and ADA-approved restrooms so much as a wrecking ball taken to its Sunday-best pretenses. This book has convinced me that the church in the digital age needs to become more like AA. It’s not that “Hi, my name is Jason and I’m…” is the means to a more inclusive church. It’s that such a hospitality for vulnerability may be the only means to a more fully alive congregation. Early iterations of the Book of Common Prayer used to invite worshippers to confess that “there is no health in us.” Crippled Grace helps us see, regardless of ability, that this sort of frank admission of brokenness—and a candid willingness to be dependent upon God or others—is the path to happiness.

Jason Micheli is a pastor at Annandale United Methodist Church in Annandale, Virginia, and the author of the forthcoming Living in Sin: Making Marriage Work Between I Do and Death (Fortress).

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 25, 2019

Ten Points on Preaching Parables

The lectionary gospel text for this coming Sunday, I noticed, is the sphincter-tightening yarn Jesus spins in Luke 15– without exaggeration the most beloved and familiar of all Christ’s parables. Thinking about the Parable of the Prodigal Son(s) and/or the Parable of the Prodigal Father (see just the naming of the parables reveals their interpretive possibilities and all the pitfalls that lie therein) got me to thinking about how we preach what are themselves Jesus’ story-form sermons.

The lectionary gospel text for this coming Sunday, I noticed, is the sphincter-tightening yarn Jesus spins in Luke 15– without exaggeration the most beloved and familiar of all Christ’s parables. Thinking about the Parable of the Prodigal Son(s) and/or the Parable of the Prodigal Father (see just the naming of the parables reveals their interpretive possibilities and all the pitfalls that lie therein) got me to thinking about how we preach what are themselves Jesus’ story-form sermons.

10. The Form of the Text Should Determine the Form of the Sermon

What holds true for preaching on scripture in general is particularly so for parables: the rhetorical form of the scripture passage should determine the rhetorical form of the sermon. A sermon on a parable should not be 3 points and a poem; it should be parabolic with a counterintuitive narrative turn that surprises and offends enough to make room for the Gospel.

9. For God’s Sake, Don’t Explain

When pressed by his disciples and his enemies, Jesus seldom resorted to the kind of utilitarian explanation that fits nicely onto a PowerPoint slide. Instead Jesus most often told stories and more often than not he let those stories stand by themselves. Rarely did he explain them and rarely should preachers do what Jesus seldom did. A parable is not an allegory with simple equivalencies between its characters and figures outside the story. Besides dwelling too long on ancient near east paternal customs or the exact equivalency of a talent in order to ‘explain’ the parable is a sure way to kill the parable.

8. Show Don’t Tell

Similar to #9, the converting power of Jesus’ parables is the emotional affect they elicit in the listener, and they hit the listener as ‘true’ even prior or without the listener being able to put the parable’s point into words.

Preaching on the parables should focus less on explaining what Jesus said and more on doing what Jesus did; that is, the sermon should aim at reproducing the head-scratching affect of Jesus’ parable rather than reporting on it.

7. Who’s Listening?

Jesus’ closed parables, the stories he explains not at all, tend to be the ones told in response to and within earshot of the scribes and the Pharisees and, about, them.

6. Context is Key

Where the evangelists have chosen to place a particular parable within the larger Gospel narrative clues one into how they at least took its meaning. Matthew places the Parable of the Talents, for example, just after a parable about waiting for the coming Kingdom but just before another about our care of the poor being love shown to Christ. So is the Parable of the Talents about anticipating the Kingdom? Or is it a harbinger of that story to come, that the 1 talent servant failed to do anything for the ‘least of these’ with his treasure?

5. Create Ears to Hear

What has made parables powerful is also what makes them difficult to preach. No longer offensive stories, they’re beloved tales whose familiarity has numbed their subversive nature. Preachers need to create new ears to hear the old stories.

To be heard rightly, preaching on parables must play with them, changing the setting, modernizing the situation, positing a contrary hypothesis about the story, or seeing the story from the point of view of one of the other characters.

4. The Idiom is Important

Jesus’ parables are largely agrarian in imagery because that was the context in which his listeners lived. Largely, listeners today do not share such a context. Not having the familiarity with that context as Jesus’ listeners did, it’s easy for us to miss the glaring omissions or additions that Jesus casts in his parables.

To do the work they originally did, preachers should rework Jesus’ parables into the idioms of our day and place so that we can hear ‘what was lost is now found’ in our own idiom.

3. Own It (Wherein ‘It’ = Hell, Judgment, Darkness)

Many of Jesus’ parables end with arresting imagery of eschatological judgment: sheep from goats, darkness, weeping and gnashing of teeth, and torture.

Rather than acting squeamish about such embellishment, preachers of parables should remember that Jesus was telling parables, stories whose truth is hidden in the affect of the narrative. Jesus was not mapping the geography of hell nor attempting any literal forecast of judgment’s content.

The shock at the end of many of these parables is what helps deliver the shock of the parable itself. Rather than run from such imagery or explain it away, preachers should own it and be as playfully serious about it as Jesus.

2. They’re about Jesus

Jesus’ parables do not reveal eternal truths or universal principles about God that are intelligible to anyone.

The parables are stories told to Jesus’ disciples even if others are near to hear. They reveal not timeless truths but the scandal of the Gospel and what it means to be a student of that good news. As Karl Barth liked to point out, the parables are always firstly self-descriptions of Jesus Christ himself. Christ is the son who goes out into the far country and is brought low. As Robert Capon argues so well, the parables are all stories Jesus tells about himself; specifically, stories Jesus tells about his death. The parables reflect Jesus’ passion for the passion.

As with preaching on scripture in general, preachers would do well to remember: It’s about Jesus.

1. Would Someone Want to Kill You Over a Story Like This?

The Gospel writers tell us that the scribes and Pharisees sought to kill Jesus in no small part because of the stories he told.

Preaching that renders the parables into home-spun wisdom, pithy tales of helpful commonsense advice or truths about the general human condition betrays the parables.

Preachers of the parables are not exempt from Christ’s call to carry their cross and preaching of the parables is one way in which we do so.

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 22, 2019

Episode #200: Guy Talk

200 Episodes!!! Say what?!? Listen as the guys take a trip down memory lane to talk about their favorite episodes, their white whale guests and what’s to come for the podcast Crackers and Grape Juice!

200 Episodes!!! Say what?!? Listen as the guys take a trip down memory lane to talk about their favorite episodes, their white whale guests and what’s to come for the podcast Crackers and Grape Juice!

Many thanks to all of you who make this project possible. Our audience grows with each conversation and new friends come into our lives each week. If you’re so inclined, visit us at www.crackersandgrapejuice.com where you can sign up to support the show.

Be on the lookout for guests we have coming down the pike:

My friend David Zahl on his forthcoming book Seculosity

Friend of the podcast, David Bentley Hart, on Universalism

Chad Bird, Amy Laura Hall, Kate Bowles, Nick Lannon and more!

Follow @cmsvoteup

March 21, 2019

Another Way Forward: Give Local Churches Power to Interview Potential Pastors

A couple of years ago I got head-hunted for several senior ministry positions by Vanderbloemen, a private church-staffing company. Just as in many other industries, local churches contract with Vanderbloemen to find, vet, and recommend candidates for open pastorates and staffing vacancies.

“How’d you find me?” I asked the head-hunter.

“You’ve got a large platform— came across you on the internet— you’ve got executive experience in a large church, and, most importantly, you’re a United Methodist. We need Methodists. These are United Methodist congregations for whom were conducting the search.”

And so went my introduction to the reality across our denomination.

Those who pledge fealty to the itinerant system ignore that there already are and have been for some time multiple parallel appointive systems in the United Methodist Church.

Around the same time I got head-hunted, for example, a prominent large church pastor who was considering an episcopal nomination conceded that in the event of his/her election to the episcopacy his/her congregation would employ a private firm like Vanderbloemen to identify a successor. Meanwhile, in every conference in Methodism there are discrete groups of “limited itinerancy” clergy who will not be moved based on a spouse’s career, children’s needs, or other factors. Conservative clergy will never be sent to certain parishes in a given conference. Ditto liberal clergy.

I mean— does anyone seriously believe that when Adam Hamilton retires from Church of the Resurrection that the area bishop will simply select another pastor from the annual conference to be appointed in his stead? Why should only the large, leading churches be granted such autonomy over their future?

Every competent pastor knows that in a congregation “anyone can serve but leaders are chosen.” Of course, in a United Methodist congregation this maxim may be true for everyone but the pastor, whom no one in the congregation chose.

It simply is not true that United Methodism has a single appointive system for clergy called iterancy, and this is a poorly-kept secret for everyone but parishioners in local churches most of whom continue to accept that they have, at best, a limited and passive role in the pastor who will lead them.

In light of the massive disruption the 2019 General Conference has visited upon local churches, the question of agency in the appointive process is not a minor one. Will Willimon says the governing ethos in the Book of Discipline since our founding in 1968 is “You can’t trust the local church.” Now however— no matter where folks fall on the question of human sexuality— the ham-fisted decision-making process at the 2019 General Conference has made plain that local churches would be foolish to trust the leadership of the larger church much less tie their future to it.

Why should local churches, whom the larger UMC does not trust and whom the larger UMC has just done irrevocable damage, rely upon the same institution to send them, unilaterally so, pastoral leaders?

Unmistakably, the fallout from GC2019 has made the local unit of the United Methodist Church more essential than at any time since our founding as a bureaucratic entity. The brand is damaged. For about half the population, we no longer are automatically the people of open hearts, open minds, and open doors. We can’t even claim any more that “Methodist means mediocre” as the UMC has just proven quite adept at harming people. Now more than ever, local churches deserve the opportunity to be empowered to make leadership decisions for their congregations’ next faithful step out of this morass.

As famed Methodist theologian Albert Outler argued back in the 60’s, the Book of Discipline’s appointive process encourages clergy who are concerned more with how they’re perceived by those who fix their appointments (district superintendents and bishops) than with their effectiveness in the local parish. A system, Outler said, where pastors are delivered to local churches by an annual conference produces pastors who think their primary duty is to deliver apportionments to their annual conference. At the same time, the current practice of appointment-making, where a 1/4 to 1/5 of all clergy in a conference are moved annually, requires an inordinate amount of time from cabinent members.

A friend who is a DS in another conference confessed to me at General Conference:

“No sooner is the appointment process done for the year than I’m back to talking with clergy about next year’s appointments. It’s a process that justifies the staffing necessary to sustain it.”

This same DS observed that as his position— and even the episcopal positions— become less attractive across the connection (because of capped maxium salaries, institutional decline, and barriers to effectiveness) more and more the appointments of pastors to local churches are in the hands of people who have no firsthand experience of having led healthy, growing congregations.

As Richard Bass, the former editor at the Alban Institute argues: “the itinerant, appointive system cannot survive a new iteration of Methodism in a post-Christian culture. Nothing frustrates the missional energy of a congregation like having no agency in who their leader is.”

Add to this the reality post-GC2019 that, with salary and seniority still a primary driver of appointment-making decisions, local churches, who now must stake out a position in the culture war over sexuality, must trust the larger church not to send them a pastor whose position is at odds with their own. The passage of the Traditional Plan and its subsequent furor makes it unavoidable that our itinerant system of sending pastors to churches will have yet another permuation to it; General Conference has made it inescapable that every conference will have parallel appointive tracks. Given that United Methodism has always had multiple systems for fixing pastors’ appointments and that General Conference will complicate this reality even more so…

Why would we not empower all local churches with the same agency that the Staff-Parish Relations Committee at Church of the Resurrection will be granted?

I say all of this too not as a gripe or with any grievance about how the present process has served me. I’m a reasonably competent, good-looking white guy. The process has served me quite well and, despite all of the above, I’m grateful for it.

Still…

The United Methodist Church’s present system of appointment-making is now incompatible with the mission of the local church.

Here’s another way forward in light of GC2019–

Free local churches to interview candidates (from a slate approved by the DS and Bishop) as well as candidates the local church solicits as well and make a selection in consultation with their DS and pending the final approval by the Bishop.

Such a process would retain our Discipline’s tradition of appointment-making being by the authority of the bishop, yet it would also return us to the true, original spirit of itinernancy. Our vows, after all, frame itinerancy not in terms of fealty to the larger organization but to the spreading of the Gospel. The form is meant to follow the function not vice versa. Itinerancy is meant to guarantee adaptable clergy so that the Gospel may be served best in each local congregation; it’s not meant to serve the career interests of clergy or the current bureaucratic arrangement.

As I see it, giving local churches more agency in the appointment process would require SPRC leaders to be more accountable to their congregations for their role in the church’s pastoral leadership no longer will be passive. It’s more likely the pastor and parish will be able to build an effective partnership for ministry since the latter will have invested time and effort to find the former. Thus it would force local churches to be intentional about their vision and missional needs and it would share more ownership of staffing those needs with the people who know them best. In addition, it would link salary increases and effectiveness measurements more closely to performance in the local congregation than with pleasing the hierarchy.

It would make the connection less dependent upon layers of apportionment-funded bureucracy, and it would force clergy out of our comfortable guild of guarranteed appointments (which is not sustainable anyways) and push clergy to be more entreneurial in our ministry, an attribute that will only benefit the church. Finally, in light of General Conference, such a process will require transparency on the issue of sexuality on the part of both pastor and parish.

I went through Vanderbloemen’s interview process. Mostly, I wanted to learn their methodology.

The staff person in charge of the search had first spent a month at the church in question, interviewing staff people, church leaders, former employees, and random people in the community. The questions I was asked to answer totaled over a dozen pages. I eventually demurred and removed my name from consideration, but had I not I would’ve been sifted through four layers of interviews before being interviewed by anyone from the congregation itself. This compared to the single form used in my annual conference consisting of a few boxes from which SPRC members are asked to check just before Christmastime.

I also learned the church paid the search company a fraction of what it normally sends in apportionments to its district office.

Follow @cmsvoteup

Jason Micheli's Blog

- Jason Micheli's profile

- 13 followers