The Paris Review's Blog, page 908

June 12, 2012

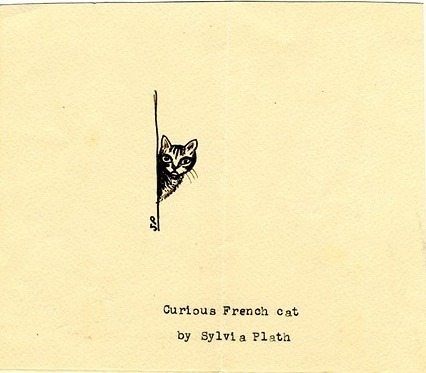

Sylvia Plath’s Sketches

Those of us who weren't able to visit the exhibition of Sylvia Plath’s drawings on view at London’s Mayor Gallery in November may take some comfort in The Telegraph’s comprehensive slide show of the poet’s pen-and ink work. The delicacy and precision of her execution will come as no surprise to fans of Plath’s writing; her mastery of the medium may. Do look at the whole gallery, but below, find just a few demonstrating the range of her subjects.

Tuesday: Me

Gombrowicz in Malosyce, 1909.

Zygmunt Grocholski’s vernissage in Galatea. Portfolios full of engravings on the table. Large surfaces soaked in color on the walls. Compositions frozen in proud abstraction look down from the walls onto the sloppy human anthill; a mob of disorderly two-legged creatures tumbling past in wild disarray. On the walls: Astronomy. Logic. Composition. In the gallery: Confusion. Imbalance. An excess of unorganized detail, which overflows on all sides. Accompanied by the Dutch painter Gesinus, I comment on one of the engravings, on which certain masses are harnessed by the slanted tensions of lines and are like a horse reined in and frozen in a leap, when someone’s behind nudges under my rib cage. I jump back. This turns out to be a photographer, bent over and aiming his box at the more important guests.

Thrown off balance, I try, nevertheless, to compose myself. In the presence of Alice de Landes, I feel myself drifting into a certain colorful fugue subject to its own laws when something rolls over me like a water buffalo or hippopotamus, barbarian style … Who? The photographer, stretched beyond all endurance, shooting doublets en face and profiles.

Salinger Foods, Austen Portraits

Does this painting portray Jane Austen at thirteen?

The Stephen King–universe flowchart.

Gertrude Stein: fact and fiction.

Regina Spektor likes J.D. Salinger.

Holden Caulfield’s cheese sandwich and other literary dishes.

June 11, 2012

Taylor Mead’s Lost East Village

Taylor Mead is dishing gossip. “For our final exam”—in boarding school, where he studied English with the novelist John Horne Burns—“he said, write four hundred to five hundred lines of poetry from memory. It was unbelievable. He killed poetry for me. I haven’t been able to read more than two poems a month since.” Burns would later write a novel loosely based on his time teaching at the school, rife with homosexual undertones. Taylor said he would have enjoyed school if he knew all the great stuff that was happening behind the scenes. “If they want me to make a commencement speech, they better fasten their seat belts,” he joked.

Taylor sat across from me at a small table near the front door of Lucien, a French bistro on First Avenue near the corner of First Street. When I walked in the door, the legendary East Village resident and professional bohemian was already sipping from a glass of Dewar’s, waiting patiently. Lucien is Taylor’s favorite restaurant; it’s one of the few places he leaves the apartment for. At eighty-seven, he still resides in the neighborhood he has called home, more or less, for more than four decades. Now, though, he has trouble walking more than a few blocks. Read More »

Electrical Banana

Mati Klarwein, Annunciation (used for Santana's Abraxas), 1961, oil and tempera on primed canvas.

I have always been a poor visualizer. Words, even the pregnant words of poets, do not evoke pictures in my mind. No hypnagogic visions greet me on the verge of sleep. When I recall something, the memory does not present itself to me as a vividly seen event or object. By an effort of the will, I can evoke a not very vivid image of what happened yesterday afternoon, of how the Lungarno used to look before the bridges were destroyed, of the Bayswater Road when the only buses were green and tiny and drawn by aged horses at three and a half miles an hour. But such images have little substance and absolutely no autonomous life of their own. They stand to real, perceived objects in the same relation as Homer’s ghosts stood to the men of flesh and blood, who came to visit them in the shades … This was the world—a poor thing but my own—which I expected to see transformed into something completely unlike itself.

So wrote Aldous Huxley just before an afternoon mescaline trip, his first, in 1954. The psychedelic sixties would take Huxley’s message to heart, opening new doors of perception while under the influence. But for graphic designer Heinz Edelmann, Huxley’s journalistic exploration was mescaline enough. After reading the British novelist’s account, Edelmann thought, “Well, I don’t need mescaline. I can do that stone cold sober.” If you don’t know who Edelmann is, have a look at Yellow Submarine: he created the look of the film and designed all the characters.

Monday: Me

Gombrowicz in Rosario, Argentina, ca. 1954.

Among literature’s famous first lines, we must include this one: “Monday. Me. Tuesday. Me. Wednesday. Me. Thursday. Me.” It comes from Witold Gombrowicz’s Diary, widely considered the Polish author’s masterpiece. Yet Gombrowicz didn’t make his first entry until 1953, when he was forty-nine and an expatriate in Argentina, and the last entry was made in 1969 from France, shortly before his death. Still, the Diary lacks for nothing: history, politics, philosophy, literature, art, music, love, death, humor, communism, Poland, Europe, writing—everything is there.

Long out of print, the Diary will be republished next week by Yale University Press as part of their Margellos World Republic of Letters series. But we have unofficially dubbed this one Gombrowicz Week and will be sharing entries from 1954 and 1955 here daily.

Yesterday (Thursday) a cretin began to bother and worry me all day. Perhaps it would be better not to write about this … but I do not want to be a hypocrite in this diary. It began when I first went to Acasusso to Mr. Alberto H.’s (an industrialist and engineer) for breakfast. At first glance, his villa seemed too Renaissance, but not betraying this impression, I sat down at the table (also Renaissance) and began to eat dishes whose Renaissance in the course of eating became more and more obvious at which time the conversation, too, settled on the Renaissance until finally and completely openly and even passionately one began to adore Greece, Rome, naked beauty, the call of the flesh, evoe, Pathos and Ethos (?) and even some column or other on Crete. When it got to Crete, the cretin crawled out, crawled out (?) and crept up but not in Renaissance manner (?!) but quite neoclassically cretinously (?) (I know that I should not write about this, this sounds rather odd).

Epic Battles, Boring Idiots, Paper Clips: Happy Monday!

The classics, condensed for babies.

Archaeologists from the Museum of London are excavating the Curtain Theatre, which predates the Globe, and may have served as an interim home for Shakespeare’s troupe.

In praise of the paper clip.

Buzz Bissinger versus Dallas.

Amazilla versus Barnes Kong: watch the epic trailer for Rebel Bookseller .

Slavoj Žižek: “For me, the idea of hell is the American type of parties. Or, when they ask me to give a talk, and they say something like, ‘After the talk there will just be a small reception’—I know this is hell. This means all the frustrated idiots, who are not able to ask you a question at the end of the talk, come to you and, usually, they start: ‘Professor Žižek, I know you must be tired, but …’ Well, fuck you. If you know that I am tired, why are you asking me? I'm really more and more becoming Stalinist. Liberals always say about totalitarians that they like humanity, as such, but they have no empathy for concrete people, no? OK, that fits me perfectly. Humanity? Yes, it's OK—some great talks, some great arts. Concrete people? No, ninety-nine percent are boring idiots.”

June 8, 2012

See You There: Paris Review at the Strand

Mark your calendars! This coming Wednesday, June 13, join The Paris Review and the Strand for the first of a series of literary salons.

Mark your calendars! This coming Wednesday, June 13, join The Paris Review and the Strand for the first of a series of literary salons.

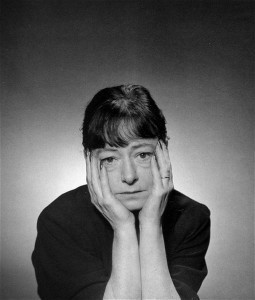

Our kickoff event brings together performers with some of our favorites from the magazine's archive. Actress Martha Plimpton will read from Dorothy Parker's 1957 Art of Fiction interview, and Wallace Shawn will reads Denis Johnson's “Car-Crash While Hitchhiking.”

In addition, we'll unveil the winner of our tote-bag contest.

Wednesday, June 13, 7 P.M.–8:30 P.M.

The Strand Bookstore, Third-floor Rare Book Room

828 Broadway at 12th Street

Admission: Buy a copy of the current Paris Review or a $15 Strand gift card.

Please note that online orders require payment at the time of checkout to guarantee admission.

Dear Paris Review, What Books Impress a Girl?

Dear Paris Review,

Someone sent me this text message yesterday: “What’s a book I should read to make girls think I'm smart in a hot way? I want to seem like a douchey intellectual instead of my deadbeat self.” What should I tell him?

Sincerely,

A

Dear A,

The correct answer is probably that your friend should be secure in his tastes, find someone who loves him for who he is, and not worry about impressing anyone. Many movies have demonstrated the pitfalls of posturing and the inevitable public unmasking that follows. That said, our job here is to try to answer questions, and as such, I took the unusual step of soliciting a range of answers from both men and women. (My own immediate response was to offer the following formula: worst book of great author, a gambit that men of this type also apply to albums, i.e. Metal Machine Music, which they will claim is underrated.) Then too, there is the dual nature of the question: Does the author wish to come across as a poseur for some reason, or attract a woman of substance? If his goal is (inexplicably) the former, the female contingent offered the following names: Madness and Civilization; The Power Broker; Žižek (any), The Brothers Karamazov. (All worthy reads, needless to say, but often used for ostentatious or intimidating purposes.) And, added one, “I like DFW, but he’s the novelist equivalent of a neg.”

As to books the women whom I spoke to found appealing (and please note that this implies actual reading, not use as props): At Swim Two Birds, The Beauty Myth, “any book read twice.” Elaborated one: “Extra points for Martin Amis memoir, minus points for other Martin Amis nonfiction. Someone who actually appears to be reading William Gaddis for real and not just carrying it around will always rate a second glance. And a straight man reading Mary Gaitskill would be nearly irresistible to me.”

When faced with the same question, male correspondents provided the following terse responses: “Cantos, Pound.” “Kathy Acker.” “Sontag.”

“Portnoy’s Complaint,” said one, “may as well be Yiddish for douche.”

Others were more expansive. “How about Laszlo Kraszahorkai’s Satantango? It’s ostentatious, hip, handsomely designed (looks great on a bedside table), and comes with seals of approval from Sontag, Sebald, and James Wood. It is also, for the most part, unreadable.”

“Gravity’s Rainbow, all the completed Caro LBJ books, Brothers Karamazov. But if you really want ‘I am a brooding intellectual with an effortless knowledge of contemporary culture,’ I think Matterhorn is tough to top.”

“There’s a difference,” remarked one colleague, “between getting a girl to think you’re smart, and getting a girl to WANT to talk to you. The following are books that will make girls want to talk to you.

—Greatest pick-up book of all time is Just Kids by Patti Smith, because every girl has read it and they ALL want to talk about it.

—Any book ever written by Haruki Murakami

—The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis

—White Album by Joan Didion

—What We Talk About, When We Talk About Love by Raymond Carver

—The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster. (Don’t question it. Just trust.)”

And in corroboration, one fellow says: “If it means anything, the only time a girl ever sat down and started talking to me out of nowhere was when I was reading Slouching Towards Bethlehem in college. Didion has an effect on people.”

Take this for what it’s worth, and we hope you actually find a book you love in the process.

Have a question for the editors of The Paris Review? E-mail us.

Watch: Ray Bradbury, 1963

I remember watching Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer, a 1963 TV documentary, in seventh-grade English class. And for good reason: there’s more good advice for writing and life packed into these thirty minutes than in many a longer (and less entertaining) tutorial.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers