The Paris Review's Blog, page 904

June 28, 2012

Good-bye, Friends; Hello, Technology!

Au revoir, Village Voice bookstore! You will be missed!

Slow readers, listen up: a new app tells you exactly how long it will take to finish a book.

Library patrons can now not only borrow but publish books.

The best Nora Ephron bookstore moments.

Meet “The Stressful Life of Salman Rushdie and Implementation of His Verdict,” a new Iranian video game.

June 27, 2012

House Proud

Almost everyone loves my apartment, which is tucked away in a pocket of New York I think of as Dowager Brooklyn. Indie Brooklyn, with its musicians and lofts and filmmakers, gets all the press. But Dowager Brooklyn has what I want: a good butcher, a wine shop that delivers, and a hardware store.

Still, even the hippest of my acquaintances walks through the wrought-iron hobbit door into my garden-level brownstone apartment and sighs with pleasure at the decorative marble fireplace, the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, the ivy-walled garden in the back. I think they half believe me when I joke that Edith Wharton drops by for tea.

Inevitably, someone asks, “How did you get this place?’’

Sometimes, I tell them the truth: witchcraft.

Peel Sessions

I’m the one who comes on Radio 1 late at nights and plays records made by sulky Belgian art students dying of tuberculosis.

This was how John Peel introduced himself to a family audience, on one of his occasional forays into British television. He can’t always have been graying, or bearded, or balding, but this is how most people continue to visualize him. He seemed, to those of us who listened to him, to have been born avuncular. For nearly four decades, until his death in 2004, Peel shared his musical enthusiasms with the ever-changing audience of his late-night show on BBC Radio 1 and made his personal collection into a truly representative historical document, like a latter-day Alan Lomax. Except that in this case, the field came to him: homemade cassette recordings sent from across Britain, and beyond, to Peel's door. This didn’t mean that no hard work was involved. Peel listened to them all, working through an avalanche of audio slush, with a heroic commitment to the aesthetically new.

Now, though not for long, we can experience the chaotic variety of Peel’s taste. Over the course of the next four months, the first hundred records for each letter of Peel’s alphabetized and rigorously ordered collection of 26,000 are to be presented online, replete with their owner’s personally devised catalogue number and, occasionally, remarks. The John Peel Archive has been supported by the Arts Council and curated with the assistance of Sheila Ravenscroft, Peel’s wife. For each letter, Ravenscroft has selected an artist of special significance to Peel, such as Dick Dale or Fairport Convention, and hosted a short corresponding film. There are links to Spotify as well as to short films, video footage, and audio files from the famous sessions recorded for his show, including an early performance by David Bowie.

Maji Moto

May 2011, Durham, North Carolina. It is late spring and the rain comes heavy in this old tobacco town. Rivulets carve tiny tributaries into the Durham Triassic Basin. Soaking up the water, the red clay swells, and then offers up an overture of honeysuckle blossoms and sugar snap peas for the upcoming symphony of tomatoes and sweet corn.

In October of 2008, I traveled to another basin, a former Pleistocene lake in Kenya. In Amboseli, my intention was to study the evolution of mate choice and fertility signals in a population of wild baboons for my dissertation research. I was working with the Amboseli Baboon Research Project, an ongoing project that began more than four decades ago. Since the time that Kenya became free of British colonial rule, when the Amboseli basin was thick with rhinoceros, researchers from the United States have been following the daily lives of the baboons in Amboseli. The births of infant male Suede, born in November of 2008, and his younger brother Saa, born in August of 2010, were like bookends on my time in Amboseli. Sorghum, their lean and lanky mother, has a coat that seems dusted with ochre undertones like the deep red soil of Amboseli, and the clay from the Triassic basin. She is high-ranking and she certainly knows it. Born into a lineage of great fortune, she is the daughter of Sera, who was the daughter of Sana, who was the daughter of Safi, who was the daughter of Spot, who was the daughter of Alto, who was one of the first adult females to be identified in Amboseli by Jeanne and Stuart Altmann in 1969.

June 26, 2012

Phillip’s Dry Cleaners

In New York, I did not want to go online and search for a gifted dry cleaner, and so I took the recommendation of a friend. The shop was in Nolita, and the cleaner was skeptical. The stain was unlikely to come out, he explained, and to attempt it, he would need a week. I told him I was leaving in three days, and he shrugged. He apologized.

In Seattle, I went online and found a place called Phillip’s Cleaners. What attracted me was not so much the raves—there were twenty accounts of removals of stains deemed unremovable—but the complaints. One man said that for a year, he had brought Phillip several shirts and two pairs of pants weekly. Then, for no apparent reason, Phillip had said to the man, “I don’t want your business anymore.”

There were several reviews of that sort. And due to a kink in my psychology—one that I believe is shared by many—this indicated to me that I had found in Phillip something very rare: a master.

My mom drove me to his shop. We had trouble finding it; naturally, it was small and not so much nondescript as invisible. She parked out front.

Portfolio: The Moors of Chicago

Code 451, Psychotic Real Estate

In what might be the ultimate honor, it has been proposed that the Internet pay tribute to Ray Bradbury. Says The Guardian , “Tim Bray, a fan of Bradbury’s writing, is recommending to the Internet Engineering Task Force, which governs such choices, that when access to a website is denied for legal reasons the user is given the status code 451.”

Happy birthday, Yves Bonnefoy!

Letters to young poets. (And novelists, playwrights, and journalists!)

Buy Bret Easton Ellis’s apartment. If you dare. To spend a lot.

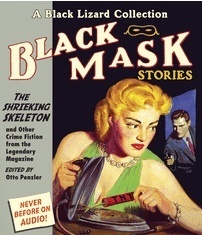

It is Audiobook Week, and in its honor, you can win a classic pulp noir.

June 25, 2012

Dance to the Music of Time: Tacita Dean at the New Museum

Merce Cunningham in "Five Americans."

Several times a week, I sneak downstairs to watch dancers rehearse with Merce Cunningham. I work at a nonprofit located in the New Museum and its current Tacita Dean exhibition includes Craneway Event, a 108-minute film of the choreographer at work in an enormous former assembly plant outside San Francisco. A postcard vista of the bay glistens in the background. As the sun creeps in, it warms the reflective surface of the floor to a bluish-gray so that in some shots water seems to ripple beneath the dancers’ feet.

Architect Albert Kahn originally designed the plant for maximum natural light. Stripped of furnishing and ornament, it looks porous rather than cavernous. There feels something almost prescriptively calming about looking at a space that size while living in a city as densely populated as New York; as if just by looking at it, I reclaim my proper wingspan after weeks in shoebox-sized studio apartments and subway cars sitting elbow-to-elbow with other passengers. My sense of time is similarly unreined. Nothing rushed, no antics, and absent of narrative; the film offers rather than requests my patience.

The term “time-based art” seems especially apt when discussing Tacita Dean’s work. In interviews, she talks of her delight in the period between shooting footage and processing it, as it allows her to revisit a film in progress with a new perspective. Her subjects might be defined broadly as the history slipping through our fingers: fleeting moments, obsolescing technology, the wisdom of an old master (Cunningham died a year after Craneway Event was made,) things just about to disappear.

As her very craft faces extinction, it fittingly became one of her subjects. Last year, Soho Film Laboratory, where she was a longtime customer, abruptly ended new orders of 16mm film prints due to new management. She was at the time preparing an installation for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, as The New Yorker explained in a profile of Dean last autumn.

Britain’s thriving community of 16mm filmmakers now must look overseas for professional printing services. And how long those labs will operate is another question. Writing for the Guardian in February last year, Dean explained how switching to digital would be like switching to a different medium:

I shoot on negative that is then taken to the lab, in much the same way you used to drop your photos off to be developed. The 16mm print I get back is called the rush print. The negative stays in the lab. Working alone on a cutting table over many weeks, I cut my film out of the rush print. Using tape, I stick the shots together, working as both artist and artisan. It is the heart of my process, and the way I form the film is intrinsically bound up with these solitary hours of watching, spooling and splicing.

When I have finished, I take my reel of taped film, now called my cutting copy, to a negative cutter, who cuts the original negative and delivers it to the lab, which then prints it as a film. My relationship to film begins at that moment of shooting, and ends in the moment of projection. Along the way, there are several stages of magical transformation that imbue the work with varying layers of intensity. This is why the film image is different from the digital image: it is not only emulsion versus pixels, or light versus electronics but something deeper—something to do with poetry.

It made me think what I would do in a world without paper and pencils, only laptops to write on. But while processing costs can be low, filmmaking, in any form, has never been cheap. Understanding the costs involved in preserving these labs, Dean called for a public specialist laboratory that could provide 16mm and 35mm film processing, “possibly affiliated to the BFI.” This would have to happen quickly as equipment, not to mention the skills of professionals, may soon be lost.

“Film” at Turbine Hall.

The Turbine Hall commission became FILM, an 11-minute long urgent plea for celluloid in an increasingly dematerializing world. “Today its years are numbered, but I will remain loyal to this analogue art form until the last lab closes,” wrote Steven Spielberg in the exhibition catalog, which reads like a series of manifestos on that point. Contributors also include Martin Scorsese, Jean-Luc Godard, and countless other writers, artists, curators, and musicians. Even Keanu Reeves wrote an essay explaining how a photochemical film set “feels like something is at stake ... it feels important and intense—uniquely ... in a way death is present in the rolling of that film.”

FILM, was itself a loving tribute to the medium. Rather than a frustrated attempt to stop time and rewind back to technologies of the past, Dean argued for the co-existence of digital and analog, emphasizing the difference. The silent film on a loop is a series of images from around the Tate. Its elevators, escalator steps, windows and other ordinary surfaces are manipulated with bright colors and cut-out shapes projected vertically on a giant perforated filmstrip 42 feet high. To see the dust and grain of the film, watch shadows puncture the image as people pass, to listen to a projector purr; is to appreciate the very physical nature of film.

Situated in the five storeys tall Turbine Hall, it provided a comforting familiarity, reminiscent of the dark expanses of a movie theater as experienced from a child's eye view. Museum visitors, especially children, walked up to the screen as close as they could to stare up. After watching the piece run multiple times, I could feel myself adjusting to its circadian rhythm and soon could approximate the time from a familiar frame.

Nostalgia is not quite the right word to describe how Tacita Dean relates to celluloid film. She is firmly rooted in the present while considering what might pass. There’s no vaseline on the lens or sepia tone here. Her nostalgia is not for film itself, but film’s way to relate the experience time. A film projector measures out minutes and seconds relating to the speed that the footage was shot.

"Film is time made manifest: time as physical length - 24 frames per second, 16 frames in a 35mm foot,” she wrote in the accompanying wall text. “It is still images beguiled into movement by movement and is eternally magical. The time in my films is the time of film itself.”

Joanne McNeil is editor of Rhizome. She lives in Brooklyn.

Watch: Issue 201 in Action!

To celebrate the release of The Paris Review’s summer issue, we put together a little video that takes you inside the pages of 201.

In case you’ve forgotten, the issue features Tony Kushner and Wallace Shawn on the art of theater; new fiction from Sam Lipsyte and Ann Beattie; nonfiction by Davy Rothbart, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Rich Cohen, and J. D. Daniels; a portfolio curated by Waris Ahluwalia; and poetry by Sophie Cabot Black, Roberto Bolaño, Raúl Zurita, John Ashbery, Octavio Paz, Lucie Brock-Broido, and David Ferry.

Five in the Colonies: Enid Blyton’s Sri Lankan Adventures

Most mornings this past winter—the Boyagoda household already running late—I discovered my oldest daughter reading at the kitchen table: one boot on, gloves, hat, knapsack, and other boot nowhere to be found. So immersed was she, so indifferent to my pleas and threats, that finally I had to pull the book from her grasping hands just to make her finish dressing for the cold walk to school. This experience has made me more sympathetic to my mother, who once spanked me in a grocery store because I wouldn’t stop reading a book. It was by Enid Blyton, the British children’s writer who wrote some 400 nursery, fantasy, and adventure series titles that have sold more than six hundred million copies worldwide, mostly in Britain and the former colonies, including Sri Lanka—where as a girl my mother herself first encountered Blyton. I recently bought one of Blyton’s books for my own daughter. But before passing it on, I decided to reread it.

The book seemed innocuous enough. As with all of Blyton’s adventure stories, it was about boys and girls drawn into mysterious doings while on summer holiday. Bickering but loyal, they best adults who are either distracted and dismissive, or criminals capable of outsmarting everybody but the kids. Working this premise for decades and dozens of stories, Blyton enjoyed great success—at the time of her death, a book club devoted to her work had some 200,000 members in Britain alone. But because that success depended upon such patterned writing, she was also accused by librarians, teachers, and academics of relentlessly dulling the imaginations of her young readers, and of unjustly encouraging those who were reading her from abroad to make identifications that race, geography, history, and politics preemptively denied them. This certainly seems to have been the case for the Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; in a 2006 interview with The Times, she explained that her development as a writer was stunted by her early reading: “When I started to write, I was writing Enid Blyton stories, even though I had never been to England. I didn’t think it was possible for people like me to be in books.” Similar notions affect the eponymous protagonists of Jamaica Kincaid’s novels Lucy and Annie John, who both declare they wish they were named Enid, after their favorite author. For both the young Adichie’s and Kincaid’s characters, mimicry and the desire for renaming aren’t simple expressions of literary admiration; they’re also rejections of the children’s African and Caribbean worlds, which have been diminished by their very immersion in Blyton’s books. The Blyton reading experience likewise impacts a colonial child’s maturation in Rohinton Mistry’s novel Family Matters, in which an intelligent Indian boy grows up reading her books and from this develops a dismissive attitude towards the foods and places and names that figure in his Bombay life. When self-loathing and alienation begin to build, he stops reading her; later, noticing her books on his shelves, he admits, “I can’t bear to even open them. I wonder what it was that so fascinated me. They seem like a waste of time now.”

Intellectually, I sympathize with these postcolonial renderings of Blyton’s invidious effects upon young imaginations, but my own experience isn’t captured by their accounts. The first Blyton book I remember reading, as a child of Sri Lankan immigrants growing up in small-town Canada, was Five on a Treasure Island. In it, four kids and a dog search for a cache of gold while avoiding grown-ups, dungeons, and other dark forces. I read other Famous Fives and Adventure books before coming to a disorienting realization. The kids in these stories were supposed to be white. I had assumed they were brown. These were, after all, stories my mother had read while she was growing up in Sri Lanka. I naturally assumed they were set there, and I populated them accordingly. But thirty years later, in reading the Blyton book I bought for my daughter, I didn’t find any brown kids. The Island of Adventure is a tale about holidaying children who discover a money-laundering operation on a deserted island and get into all sorts of trouble before saving the day. These children and their world are clearly British—their speech is punctuated by exclamatory “I says” and “spot of this, spot of that” quips; the oldest boy is already a devoted birder; and their pet parrot declares “God Save the Queen” rather a lot.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers