The Paris Review's Blog, page 790

August 20, 2013

Watch The Paris Review on Charlie Rose, Here!

Now we’re making it really easy for you! For those readers who were unable to catch James Salter, Mona Simpson, Lorin Stein, and John Jeremiah Sullivan discussing The Paris Review’s sixtieth anniversary on Charlie Rose, are you ever in luck! You can now watch the full segment below (sans introductory interview with Yelp founder Jeremy Stoppelman). Yes, we’ve given this a lot of ink, but what can we say—we’re proud!

Mark Twain Designed His Own Notebooks, and Other News

Twain’s notebooks, Plath’s pens, and other preferred writing paraphernalia of famous authors.

Via the minds at McSweeney’s, an invaluable Field Guide to Uncommon Punctuation.

An elaborate, book-themed proposal involving a custom children’s book, a library, and a lot of planning.

The Today Show has reanimated its book club, and kicked off with The Bone Season, by twenty-one-year-old Samantha Shannon. (“The next Rowling?” asks Today, unfortunately.)

August 19, 2013

This Is Growing Up

A panel of Adam and Eve in Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise.

I had only been in Europe for two weeks when I started to feel homesick.

I’d decided to study in Florence on a whim, after having vaguely planned my entire sophomore year on traveling to Prague to study film at the famed FAMU. But while for FAMU there was a separate application I would have had to fill out, Florence was a simple checkbox on the registration website. And student housing in Florence was even cheaper than at my university in New York.

The general idea was to get a handful of my general education requirements out of the way and maybe even try to pick up some Italian while I was at it. I flew over to Italy with my mother, who was looking for a few days away from Chicago to take in, as she called it, la dolce vita. “I want a gondolier to sing to me, like in the movies,” she said. The gondolier spoke on his cell phone the entire time.

We arrived at the Florence Airport mid-morning. On the cab ride into the city, the driver informed us that one of the city’s time-honored traditions was complaining about the tourists, and, even worse than the general run of tourists, the hordes of visiting college students. I soon found myself in a large apartment off via Guelfa introducing my mother to ten other college students and an Italian RA. My mother quickly pulled me aside. “Please don’t get into any trouble. You know what the driver said.”

In Case You Missed It…

If you weren’t able to catch James Salter, Mona Simpson, Lorin Stein, and John Jeremiah Sullivan talking The Paris Review’s sixtieth on Friday night’s Charlie Rose (or, like some of us, were forced to watch it in closed caption), you’re in luck! Tonight, the show airs again on Bloomberg TV at 8 P.M. and 10 P.M. EST.

The Immortality Chronicles: Part One

What have we not done to live forever? My research into the endless ways we’ve tried to avoid the unavoidable is released today as The Book of Immortality: The Science, Belief, and Magic Behind Living Forever (Scribner). Every Monday for the next six weeks, this chronological crash-course will examine how humankind has striven for, grappled with, and dreamed about immortality in different eras throughout history.

We’ve always had a thing for sequels. The suggestion of a second act is built into the fossil record. Tens of thousands of years ago, Neanderthals were already digging premeditated gravesites. They intentionally buried dead kin in fetal positions, indicating some hunch about posthumous rebirth. By Neolithic times, when we’d gotten the hang of agriculture, food started being placed alongside entombed bodies—presumably so they’d have snacks for their journey to the spirit realm.

Our terror and awe of mortality can be traced back to prehistoric nothingness. Every story about immortality since then has been a story about the meaning of death, an attempt at warding off our innate fear of finality. As soon as we figured out how to write, we started jotting down consolatory tales about living forever.

The cuneiform tablets of Nineveh, among the earliest written documents, tell of King Gilgamesh, whose best friend dies. He is stricken with grief. But he is the omnipotent king of Uruk, the one who gazed into the depths—the one who slayed the Bull of Heaven!—surely he’s almighty enough to bring dead loved ones back from the grave. Mute with sorrow and pride, he buries his friend beneath a river and sets out to find eternal life. The scorpion people, whose knowledge is fathomless and whose glance is death, warn him about dangers ahead. A lady of the vines tries to console him, telling him that love is the closest mortals can come to immortality. Crossing the Waters of Death, he discovers a marvelous underwater plant that contains the secret of perpetual youth—the watercress of immortality, as the clay etchings call it, or the “never-grow-old”—but, alas, a serpent promptly steals it away. History’s prototypical protagonist fails, yet his story ends the only way it can: with acceptance, of reality. Of mortality.

John Hollander, 1929–2013

“Literature is not different from life, it is part of life. And for someone like myself, The Odyssey is as much a part of nature as the Aegean. And I react to the Aegean—as distinct, say, from the Caribbean—because its history is part of its physical substance. What I know about it, and feel about it, even mistaken things, is a part of it. Certain great texts are like this. Paradise Lost is like the Himalayas. It’s there. A part of nature, not separate.” —John Hollander, The Art of Poetry No. 35

John Hollander, 1929-2013

“Literature is not different from life, it is part of life. And for someone like myself, The Odyssey is as much a part of nature as the Aegean. And I react to the Aegean—as distinct, say, from the Caribbean—because its history is part of its physical substance. What I know about it, and feel about it, even mistaken things, is a part of it. Certain great texts are like this. Paradise Lost is like the Himalayas. It’s there. A part of nature, not separate.” —John Hollander, The Art of Poetry No. 35

Heartless Thief Steals Books on Bikes Bicycle, and Other News

Shocking, shocking: a Seattle thief has stolen the Books on Bikes librarian’s bicycle. Thankfully, the trailer of books was not attached.

“Sixty percent of the thirty-six books recommended for four-to-eight-year-olds feature animals, or are in other ways concerned with nature. For the nine-to-twelve age group, it’s just over fifty percent.” Why are children’s books so preoccupied with fauna?

Casual sex: a great way to get book recommendations!

By contrast: an interview with the author of the best-selling The Art of Sleeping Alone: Why One French Woman Gave Up Sex. (This is, obviously, the English title; French people are presumably less obsessed with French women than are anglophones.)

Behold: the trailer for C.O.G., adapted from David Sedaris’s Naked!

August 16, 2013

Literary Architecture

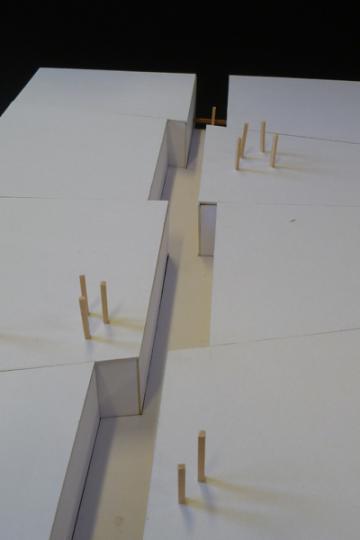

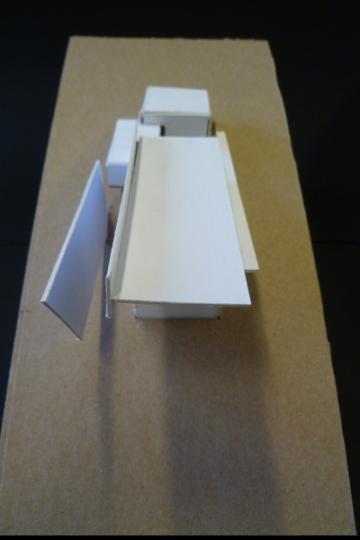

One Friday evening in March, I took the train to Columbia University and walked into one of the strangest and most interesting classes I’d ever seen. It was the Laboratory of Literary Architecture, part of the Mellon Visiting Artists and Thinkers Program at Columbia University School of the Arts, and a multimedia workshop in which writing students, quite literally, create architectural models of literary texts. For the past four years, Matteo Pericoli has led the workshop at the Turin-based Scuola Holden creative writing school, and this year, he brought the concept to New York. While the idea seems intuitive enough—each student chooses a text he or she knows inside out, and then builds it—the challenges arise in interpretation. “A text you love is not, necessarily, the best for this project,” said Pericoli. He adds that it is crucial that students work from another author’s text, rather than their own, to facilitate the true objectivity necessary.

And then of course there is the question of getting away from the literal. “One student chose ‘A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again’ and thought she would just make a ship,” he explains, referring to David Foster Wallace’s cruise-ship odyssey. But then they learned the class’s mantra: “Literary, not literal.” The structure that ultimately resulted (because the writing students team up with architects to build models that must function as well as engage) was very different. Writes Elizabeth Greenwood of her final model,

I designed a rectangular structure with many floors. Bolstered by concrete brackets, the end pieces represent the hard, inescapable fact of heavy things in the essay: the Harper’s assignment, the ship itself. But the floors inside these brackets are made of glass to represent the clarity and truth Wallace sees during his time at sea. On the outer edges are two parentheses turned away from one another (which might one day be openings for stairs) representing the thoughts and connections between seemingly unrelated things. These cuts into the plexi allow light to filter through between the floors, illuminating their invisible links and also tracing seemingly disparate themes and digressions. As the floors ascend, these parentheses edge closer to the upper right corner, where an elevator shaft penetrates through the structure. This burst of continuity between floors represents the author’s presence, and the author himself, who cannot be contained even within the clearest of glass, and who stubbornly refuses to be subdued even in the most ostensibly light of occasions, like a vacation on the high seas.

As Pericoli explained to me, the process of examining structure, flow, interconnections, the author’s intentions, all managed to both mirror and illuminate the process of writing: rendering explicit that which had been intuitive, forcing students to deal in both interpretation and a little mental detective work. What is an author’s intention for how a piece is read, or experienced? What is a reader’s? As much as anything, the variety of interpretations—and, yes, over the years, Pericoli has seen multiple students take on the same work, with wildly differing results—is startling. J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace becomes a rectangular structure with a meandering path that evokes the protagonist’s unwilling shifts in perspective. To the Lighthouse bears no resemblance to an English country house by the sea, but rather becomes a structure that centers around a vacancy: that of the mother. The exercise demands both serious imagination and intense discipline—qualities essential to the disciplines of both writing and architecture but presented as dauntingly unfamiliar challenges that both force participants out of their comfort zones, and ultimately create new ones: different, yes, from the initial familiar comfort of a beloved text, but functional and fascinating all the same.

“The way out can only be seen from a specific perspective—the staircase back up to ground level is hidden behind a false wall—and once seen it cannot be unseen. Eventually, the staircase becomes too much of a curiosity. The participants will climb the stairs and exit the structure, and find themselves completely removed from it. To leave, first they have to go completely into the structure.” —Joseph Ponce, writing on Raymond Carver, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love”

“Ultimately, I wanted this model to be interpretable from two perspectives: one, the perspective of the walker going through the path who cannot know what to expect next, and two, the perspective from above that is able to see the model in its entirety: to see the knife cuts, the single-minded yet zig-zagging path, and the reflection in the water at the end of it.” —Joanna Yao, J. M. Coetzee, Disgrace

“My idea was to have an entrance that you stumble upon, peep in, and find yourself within, without actively seeking it. It’s welcoming because it does not have a door, but rather an entry. You cannot see what is inside it without going in, similar to not perceiving the nightingale’s song unless you let the other thoughts fade away and listen. The building could also have an actual door on the ground level for the part below the elevated path that could be used as a café or restaurant. The elevated path is above and apparent for those who choose to see it and are curious about it.” —Zeynep Lokmanoglu, John Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale”

“The structure is a tall and narrow space, reflecting both the vast scope of the book as well as the intimacy of the reading experience. An uneven path is suspended along metal supports, and gradually rises and falls across the entire length of the structure. The path’s shape is dictated by the fragmented and surprising nature of the narrative, in which the novel leaps from subject to subject through unconventional avenues, such as the documentary playing in the narrator’s hotel room. The path is covered in a translucent material so that these supports are visible, which alludes to the meta-fictional nature of the novel.” —Joss Lake, W. G. Sebald’s Rings of Saturn

“The two structures are alienated by a space, a gap, but connected by a passageway, which, situated on the far left, spills from one building into the next. To get from one structure to the other, one must endure the trip through this dark, windowless space. To embody the cyclical nature of Woolf’s writing style, there is also a circular gesture created by the space between the two buildings, rounded on each side by the ramp and the passageway, respectively. This reveals itself only in a bird’s eye view of the design.” —Catherine Pond, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse

“When you are inside this structure, traveling back and forth, up and down, there is an imperious desire to discover the space as you become overwhelmed by its magnitude. I wanted to mimic the strong sense of spatial awareness that you experience reading the piece, thus I looked for a similar feeling while you navigate the structure. The sense that you have an active role in reading the space and that when you are traveling through it, you are ultimately ‘writing’ the space with your body.” —Javier Fuentes, George Saunders’s “The Falls”

Read more about the Laboratory here. You can read more about Matteo Pericoli on his website and follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Tonight! The Paris Review on Charlie Rose

Tune in tonight to Charlie Rose for a conversation with editor Lorin Stein, James Salter, Mona Simpson, and John Jeremiah Sullivan on the sixtieth anniversary of The Paris Review. Trust us, it’s an engaging interview—even Kevin Spacey agrees.

The show will air at 11 P.M. on PBS, but check your local affiliate to confirm the time.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers