The Paris Review's Blog, page 201

October 29, 2019

John Ashbery’s Reading Voice

“75 at 75,” a special project from the 92nd Street Y in celebration of the Unterberg Poetry Center’s seventy-fifth anniversary, invites contemporary authors to listen to a recording from the Poetry Center’s archive and write a personal response.

John Ashbery at 92Y in 1970 – Frank O’Hara Tribute reading (photo by Jack Prelutsky)

The Unterberg Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y has a seventy-year archive of recordings—it began hosting readings in 1939 and recording them in 1949—and it offers a unique opportunity to study poets’ voices and reading styles. Between 1952 and 2014, John Ashbery made seventeen appearances on the stage of the Poetry Center. He read with other poets—Barbara Guest, Mark Ford, Jack Gilbert, John Hollander, J. D. McClatchy, W. S. Merwin, Kenneth Koch, Ron Padgett, and James Schuyler. He read with painters—Jane Freilicher and Larry Rivers. And he joined in readings honoring other poets—tributes to Frank O’Hara (1970), Elizabeth Bishop (1979) and Marianne Moore (1987). Ashbery, who made regular Poetry Center appearances from the ages of twenty-four to eighty-seven, is on a short list of poets whose Y readings spanned so many decades (others include W. S. Merwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, Adrienne Rich, Richard Wilbur, and Galway Kinnell).

As a scholar and poet who uses software to analyze performance style in poetry recordings, I was thrilled when Bernard Schwartz, the Poetry Center’s director, invited me to study the archive. The Ashbery readings seemed, to me, like a perfect corpus to begin with.

But even those who loved attending Ashbery’s poetry readings (I am one of them) might feel that he’s the last poet in the world whose performance style is worth studying. He typically read in a restrained, unassuming voice, and the unofficial consensus is that the performative energy of his poetry plays out not in the vocal delivery, but in the slippery syntax, the sly comedy of skewed idioms, the rich mixture of vocabularies and startling tropes, the momentum of swerving thought. His poems can elude the audience’s understanding in a live reading, and they elude many readers on the page as well.

Raphael Allison (as I discussed in Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non)Performance Styles of 100 American Poets) describes Ashbery’s reading style as “a performance of nonperformance.” He means this as a compliment, particularly in reference to a 1963 reading recorded at the Living Theatre. However, Richard Howard, who actually attended the reading that night, remembers Ashbery as having, in Allison’s words, “read with extreme dramatic flair.” Ashbery was “striding up and down, smoking, wreathed in clouds of smoke … on the set for The Brig [a play about a soldier that went up in May of the same year] behind a lot of barbed wire,” Howard remembered. “It wasn’t certain on that occasion whether the wire was to keep him from us or us from him.” Clearly Howard ascribes a certain power to Ashbery’s physical presence, while Allison has only the recording to judge from.

Here’s another perspective. “John Ashbery’s near monotone suggests a dreamier dimension than the text sometimes reveals,” writes Charles Bernstein. Once we have heard a poet like Ashbery read, he feels, “we change our hearing and reading of their works on the page as well.”

I witnessed Ashbery read on four occasions. At one of these, on April 8, 2001, he cleared the room—the beautiful Morrison Library reading room at the University of California, Berkeley. The reading began as standing-room only. My boyfriend and I were the last to squeeze in the door. Charles Altieri introduced Ashbery with sincere, abstrusely articulated enthusiasm, sat down, and soon fell asleep.

I watched as many in the audience become visibly, unduly mystified by the poetry, or Ashbery’s manner of reading it, or both. Or they were simply bored. The undergraduates, drawn by the aura of Ashbery’s name, streamed quietly out of the room in ones and twos and threes, until it was more than half empty. But I was committed to the end. I was writing my dissertation in part on Ashbery’s poetry, and his writing had changed my attitude to boredom, to poetry, to language itself.

It is common to be bored at a poetry reading, or at least under-stimulated, especially by poets esteemed in the academy. My own inarticulate pleasure in, and intense irritation with, certain poetry reading styles is what led me to research poetry performance in the first place.

If I’ve learned anything in this rather rarefied line of research, it’s that the voice is a slippery thing, and so is our perception of it. Speech scientists concur with Robert Frost that the “tone of meaning … without the words”—the intonation and rhythm of the voice—are often perceived as more important than the words. Whenever we listen to a voice, we bring all sorts of unconscious and half-conscious expectations and biases to the experience.

Those who walked out on Ashbery at Berkeley in 2001 probably thought, in some way, that he wasn’t reading the way a poet should, or that his poems were not what they thought poems should be. When we hear a voice, and especially when we listen to a disembodied voice—we listen with expectations and biases in regard to gender, age, race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, cultural or religious background, education, educational background, region, nationality, mood, et cetera. We try to pin down the speaker’s identity, and complain if they do not fit our expectations. The Berkeley undergraduates of 2001 might have expected Ashbery’s vocal delivery to sound more like a poet, or more queer, or more like a New Yorker, to correspond with whatever vocal stereotypes or conventions they had in mind for these roles or identities.

In her recent book, The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre and Vocality in African American Music, Nina Sun Eidsheim gives us a term for the question we ask when we listen to a voice: Who is this? We don’t just ask this when we answer a phone call from an unknown number. When we listen to any stranger’s voice, we try to pin down the speaker’s identity—and thus radically reduce that voice’s individuality to conform to or be rejected by our expectations. Eidsheim calls this the acousmatic question—after Pierre Schaeffer, who “derive[s] the … root [of acousmatic] from an ancient Greek legend about Pythagoras’s disciples listening to him through a curtain.” She argues that it relies on fundamental misunderstandings of the human voice and our own listening practices, particularly in regard to vocal timbre. One of her case studies is the voice of Jimmy Scott, a jazz singer who was sometimes characterized as a freak (as he arguably was in Episode 29 of Twin Peaks). Though he was a cisgender male, Scott suffered from Kallmann syndrome (delayed or absent puberty), and had a limited career due in part to racialized assumptions about how a black man should sound.

Who is this? is often the wrong question, but we are always asking it anyway. The next time you listen to a recorded voice without knowing the speaker’s identity, ask yourself what assumptions you are making about their identity, and why.

In The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, Jonathan Sterne advances a persuasive critique of conventional assumptions about hearing versus seeing, which he calls “the audiovisual litany,” including the notions that “hearing tends toward subjectivity, vision tends toward objectivity” and “hearing is a temporal sense, vision is primarily a spatial sense.”

Of course, seeing is no more objective than hearing, and both hearing and seeing operate spatially and temporally. But a poem holds still on the page when we study it. A recorded poem does not. Nor do our perceptions of what we’ve heard. And so what I call slow listening—listening repeatedly to the same recording, and making some attempt to analyze recorded voices as physical phenomena, to visualize their effects, and to analyze quantitative data about them can illuminate (there’s the hegemony of the visual for you!) what it is we have just heard. Slow listening serves as a refinement of, and sometimes a corrective to, our impressionistic perceptions; developing this technique has made me more aware of my own biases as a listener, and it has made me listen more precisely.

So what was Ashbery up to as a reader? Studied calm? Dramatic flair? Trance-inducing monotone? Was he an unusually inexpressive reader, not to say boring? And did he always read in a similar manner? What was characteristic of his voice, anyway?

When I analyze a poet’s voice, I start with pitch and timing patterns. Based on some linguistic research and our own intuitions about what makes a voice sound expressive, neurobiologist Lee M. Miller and I have developed a toolbox of prosodic measurements called Voxit.

Pitch is typically measured in Hertz, or cycles per second; with the human voice, this means the number of times the vocal cords vibrate per second. Among the fifty male American poets I sampled in “Beyond Poet Voice,” the average pitch was 115 Hz. (Richard Blanco, Carl Phillips, Ted Kooser, Robert Pinsky, Matthew Zapruder, Peter Gizzi, and Mark Doty ranged from 81 to 91 Hz, while CA Conrad, Amiri Baraka, Joshua Clover, Robert Hass, Juan Felipe Herrera, and Alberto Rios were at the upper end, from 139 to 151 Hz).

What about Ashbery? In a sampling of recordings drawn from his readings at the Poetry Center, his pitch ranged from 100 to 149 Hz. As a generalization, Ashbery seemed to use lower pitch when he was younger and higher pitch when he was older. A much larger sample would be needed to confirm this, but the finding aligns with the research: the pitch of male voices tends to rise with age.

People may raise their pitch when emotions become more intense, as when Ashbery read Elizabeth Bishop’s “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance” at the Y’s Earth Day event in 1997. In The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets, David Lehman remembered that, “When [Ashbery] reached the last stanza, he cried.” As you can hear, Ashbery starts to sound hoarse and teary around line 54 (“asking for cigarettes”), part way through the second stanza. He recovers and breaks down again for much of the last stanza, beginning with “Why couldn’t we have seen / this old Nativity while we were at it?”

When a speaker changes pitch faster, either up or down—we measure this as pitch speed and pitch acceleration—they sound more expressive. In these terms, Ashbery uses his most expressive pitch—his fastest pitch speed—in his youth, and, not surprisingly, when he reads humorous crowd pleasers, no matter the year. For instance, the masterful sestina “The Painter” in his 1952 debut reading; or “The Songs We Know Best,” in both 1981 and 2008; or the comic sestina “Faust,” in 1967 and 2008, which was inspired (as Ashbery explains in 2008) by a comic strip about The Phantom of the Opera in the Montpellier newspaper. He uses pitch least expressively—his slowest pitch speed—when he reads Marianne Moore’s poem “Abundance,” at the tribute in 1987. “Abundance” is a highly formal poem of nine stanzas, and like many of Moore’s poems, the poem’s mood is one of quiet, restrained amusement; perhaps Ashbery reads it with rather flat intonation to enact a deadpan tone. Perhaps he does this all the time, to some degree.

What about rhythm? How quickly a poet speaks, how much their speaking rate varies, how often they pause, and for how long—these factors influence the perception of rhythm and how regular the rhythm is. Long pauses in speech create suspense, and, if they do not recur, they can break a rhythmic pattern. As a generalization, the more predictable a poet’s rhythmic complexity, the more formally they may read—whether the poem they are reading is written in a fixed form or not. In my research, I have found that Allen Ginsberg exhibits very low rhythmic complexity, or a predictable rhythm, in reading Howl, for instance, while a conversational poet such as Dean Young sometimes uses very high rhythmic complexity, or an unpredictable rhythm.

So when does Ashbery read most formally, in terms of regular rhythm? And when does he use a more irregular rhythm that is more typical of conversation than formal poetry? Does the rhythm he deploys in the reading of the same poem shift over time? Below are samples of the same two poems, “Faust” and “Rivers and Mountains,” from 1967 and 2008.

In the 1967 reading, Ashbery tended toward a more predictable, formal rhythm. Perhaps he was feeling rather formal that night, or in that era? Ashbery never wrote a great deal in fixed forms, and perhaps he moved away from them more as his poetry developed. But in 2008, he read a number of poems that use anaphora and other forms of verbal or rhythmic or even musical repetition and catalog (“He,” “Default Mode,” “They Knew What They Wanted” and “The Songs We Know Best”) and read them with a more conversational, less predictable rhythm than he might have in 1967. Of course, the use of irregular rhythm, shifting emphases and long pauses also play well for comedy and dramatic suspense.

On the 2008 recording, Ashbery sounds like he is good spirits—he decides to read two more, rather than one more, poem at the end. It’s as if he is having a lively conversation, albeit one-sided, with an appreciative, frequently chuckling audience. It reminds me of the best reading I ever heard him give—at the New School’s John Ashbery Festival in 2006—when he read “Litany,” a poem famously written in “two columns meant to be read as simultaneous but independent monologues” with Ann Lauterbach, James Tate, and Dara Weir. It was deeply funny and poignant at once—Ashbery at his best, feeding off the energy of conspiratorial collaboration.

The best way to appreciate Ashbery’s reading style is to listen, of course, yet Ashbery himself was not always sold on poetry in performance. In a 1966 interview (included in the Y’s 2017 memorial tribute to Ashbery), he said: “Well, I’m against poetry being read out loud. That may sound funny. When I hear poems read out loud, I really don’t get very much from them. I have to see the poem and hear it in my mind for it to really mean something. In fact, when I’ve read poems out loud, sometimes people will say, Oh I really understood that when you read it, I got a great deal more out of it, which is not what I want to happen. Because, I mean, if I had written the poem right, it should mean more when it was read on the page.”

Ashbery did not particularly like his own voice, or at least his native upstate accent. Of meeting Frank O’Hara for the first time, he remembered: “It was rather a surprise when I overheard a ridiculous remark such as I liked to make uttered in a ridiculous nasal voice that sounded to me like my own, and to realize the speaker was Frank … Though we grew up in widely separated regions of the Northeast, we both inherited the same twang, a hick accent so out of keeping with the roles we were trying to play that it seems to me we probably exaggerated it, later on, in hopes of making it seem intentional.”

My favorite way to read Ashbery is on the page, while listening to his recorded voice. His 1952 reading of “The Painter” is especially delightful. At the age of twenty-four, he reads “The Painter” with the broad vowels of his upstate accent fully intact.

Listening to Ashbery’s comparatively expressive early reading of “The Painter” reminds me how much different voices are crucial to his poetics, whether they are explicitly different characters in a poem or simply contending points of view within a single consciousness. It’s no surprise that his own voice and performance style changes—perhaps more than we would have thought—poem by poem and over the years.

Marit MacArthur is a lecturer in the University Writing Program and an affiliate faculty member in Performance Studies at the University of California, Davis.

October 28, 2019

The Opera Backstage

Edgar Degas and the stories we tell ourselves, at the opera and everywhere else.

Edgar Degas, La Loge (cropped), 1885. © Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

The opera is an ideal place to be distraught. You’re surrounded by characters who are on the brink of emotional collapse, performing some exaggerated version of a familiar feeling: it gives perspective. It’s also an ideal place to dupe yourself, to tell yourself stories about who you are. You can go alone, sip your drink elegantly at intermission, as if waiting for someone just out of sight.

Edgar Degas was particularly in his element at the opera house. In 1875, Charles Garnier designed what might still be Paris’s most beautiful building, the Opéra Garnier. It was a place of cultural but also social and political power, set at a major crossroads of Baron Haussmann’s Second Empire boulevards. In the mid-nineteenth century, opera was embraced as a focal point for the burgeoning movements of realism, Romanticism, and Orientalism, and was viewed as the ultimate art form—a place to work out human potential and ambition: as heroes and villains, as cultures and nations, the grandest of stories. But as the Garnier was going up, opera’s sociocultural power was going down. France didn’t have a great singer and the dancers were just okay. Perhaps the Garnier’s beauty wasn’t fair to the performers: they had such rarefied surroundings, how could they ever live up to them? Degas preferred Paris’s old opera house, the one on the rue Le Peltier that burned down in 1873. The Garnier, he found, was too overwhelming.

François Debret, Plans de l’Opéra de la rue Le Peletier : coupe longitudinale, 1821. Paris, BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra © BnF

“Degas at the Opera,” on at the Musée d’Orsay until January 19, includes dozens of his behind-the-stage scenes and explores the way in which the Paris opera was the Studio 54 of its day, the place to see and be seen and, crucially, to catch people at their most charismatic in the audience and at their most honest backstage, where the public wasn’t watching. Behind the curtain a number of stories transpired, and Degas, throughout his life, was the ultimate voyeur. He preferred the wily characters, the creepy men who held their top hats steady as they walked about the foyer de la danse, allowed to share space with the dancers backstage so long as they attended the opera three days a week. Technically, they weren’t allowed to touch, but invariably they did. In 1882, Degas wrote to his friend Albert Hecht, a known art collector, asking for a day pass to the opera’s backstage; eventually, he would subscribe himself. He began coming all the time, even when shows were not on. “He comes here in the morning,” a friend noted. “He watches all the exercises in which the movements are analyzed, and … nothing in the most complicated step escapes his gaze.” He was obsessed with the women of the opera, but according to his friends and by his own admission, he was celibate. Manet spun it differently: “Incapable of loving a woman or even telling her he does.” Or Van Gogh: “Degas lives like some petty lawyer and doesn’t like women, knowing very well that if he did like them and bedded them frequently, he’d go to seed and be in no position to paint any longer. The very reason Degas’ painting is virile and impersonal is that … he observes human animals who are stronger than himself screwing and fucking away and he paints them so well for the very reason he isn’t all that keen on it himself.” Degas only watched the stories unfold; he did not partake. And it was only by not taking part that he gained such a complex grasp. He recognized the artifice of the opera and of life—the business of the backstage, how the stories being told in front of the curtain were not the same as the stories happening behind it.

Edgar Degas, La Classe de danse,1873. Photo © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Mostly, the stories were of class. The men chasing the dancers around were of a higher social stratum—the age-old trade of wealth and status for beauty and youth. The dancers were almost exclusively from the lowest classes, and the glamour bestowed upon them by the opera was just enough to make them desirable as mistresses or even as wives. Degas did not like this. Having come from a wealthy family (he never had to work for money; his father a banker, his mother an heiress of a New Orleans cotton fortune), Degas advocated a rigid class structure: the ballerinas should be nowhere near lawyers and diplomats.

Edgar Degas, Le Rideau, vers 1881. Photo © Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art – NGA IMAGES

But the stories were also of gender. John Richardson, that cheeky art historian, was particularly tough on the performers’ looks. “Photographs,” he once wrote, “confirm that Degas was not exaggerating when he revealed his dancers to have been a depressingly dog-faced bunch. No wonder he preferred to show us a maître de ballet teaching a class or conducting a rehearsal rather than a ballerina strutting her stuff.” Degas likewise said harsh things of women. When he learned a female friend wouldn’t be attending a dinner party he was throwing because she was “suffering,” Degas wondered aloud, “How does one ever know? Women invented the word ‘suffering.’” About his supposed friend Berthe Morisot, he declared, “She made paintings as she would hats.” Was Degas a misogynist? In front of the curtain, in the way he spoke about women, he was, but behind the curtain, in the way he painted them, perhaps not.

Edgar Degas, La Classe de danse,1873-76. Photo © Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art – NGA IMAGES

Certain female scholars like Carol Armstrong and Norma Broude have concluded that Degas’s depictions of women are generally disinterested in what a male viewer might think. Others, though, like Hollis Clayson and Anthea Callen see him as just the prototypical man, maintaining the male gaze on his female subjects. So, too, the critic J. K. Huysmans didn’t buy the idea of Degas’s protofeminism. Degas, Huysmans wrote, wanted to “humiliate” and “debase” the dancers by painting them. He “brought an attentive cruelty and a patient hatred to bear upon his studies of nudes,” depicting them in pain, as they stood tall on their delicate toes, washing away their innocence for the supposed banality of the stage, for the supposed chance at a top-hatted man.

Edgar Degas, Ludovic Halevy et Albert Boulanger-Cavé dans les coulisses de l’Opéra, 1879

Degas framed his pictures untraditionally, going for odd perspectives, looking where he shouldn’t look: a woman askew, a seemingly key player cut out, as if photographically cropped from his canvas. The poet Paul Valéry, as noted by the American artist Paul Trachtman, thought of Degas as “divided against himself.” “On the one hand,” Valéry wrote, “driven by an acute preoccupation with truth, eager for all the newly introduced and more or less felicitous ways of seeing things and of painting them; on the other hand possessed by a rigorous spirit of classicism, to whose principles of elegance, simplicity and style he devoted a lifetime of analysis.”

Degas ultimately thought that his paintings of the women who performed at the opera cut through the stories they were telling themselves, about their claims to beauty, status, and talent. He believed that was the goal of the artist: to separate what we tell ourselves from what is true. “Women can never forgive me,” he told the painter Pierre-Georges Jeanniot. “They hate me. They can feel that I am disarming them. I show them without their coquetry, in the state of animals cleaning themselves.”

Edgar Degas, Répétition d’un ballet sur la scène, 1874. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Degas might have been a misogynist, but he was right about the nature of human performance. We all tell ourselves stories, many of them conflicting, but, so long as we’re not irredeemably deluded, we know they are, at least in part, necessary fictions. Sometimes the cracks show between what we tell ourselves and what we know to be the truth. Nuance is key. At times, the curtain comes up before the dancers have had a chance to ready themselves, before the top-hatted men have made their way back to their seats. Some of us tell ourselves closely accurate stories, others turn themselves into victims or aggressors, kindly souls or crafty louts. We crave identity, selfhood—to have a story is to be human. Friends, therapists, lovers—they tell us our stories are correct. To affirm a person’s story is to affirm her significance.

The scope of opera is such that nearly any other story can fit inside. La Traviata is about a courtesan who falls in love, betrays her lover, loves him again, is forced to live modestly, then, only on her deathbed, receives his forgiveness. It was set in the eighteenth century, then the late-nineteenth century; today, it’s the most frequently performed of all operas, and it’s often set in the fifties. It’s elastic. Betrayal, love, and death are its constants. Or Carmen: a gypsy seduces a soldier who abandons his post and his first love; then, when he is betrayed by the gypsy, he murders her. Again: betrayal, love, death. The holy trifecta, the trinity of human experience. For the most classic opera, like the most classic stories, you can turn a deaf ear and a blind eye to the specifics because there really are no specifics. Their point is their grandeur, and in this way opera is an exercise in spectacular sameness. It is an umbrella over all possible stories and emotions.

Edgar Degas, Le foyer de la danse, 1890 -1892.

One of my favorite paintings by Degas, which is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art but is sadly seldom on view, is “The Ballet from ‘Robert le Diable’,” in which Degas depicts men in the audience distracted and bored as the performance rumbles on. One has even turned his binoculars to others in the audience, looking for different entertainments, different stories.

I’ve been going to the opera frequently lately—La Cenerentola, Manon Lescaut, Madama Butterfly—sitting in the cheapest seats at the Met, where only unwitting tourists and NYU students go. When I was younger, I didn’t enjoy the opera because I didn’t know how to watch; I didn’t know that sometimes what is happening off stage is as intriguing as the show itself. On a recent evening, I looked around my row to watch people watching, as the man in “The Ballet from ‘Robert le Diable’,” does. Have you ever watched others watch something? At first, they look like machines, and it’s difficult to think that they are feeling things as layered and intimate as you are. But then it takes you out of yourself. You see that what you are seeing and what they are seeing is both exactly the same and entirely different. You begin to see yourself in them because it is impossible to watch yourself watching. As the story goes on onstage, you see that we have all neared some form of emotional death; we have all been beaten down and raised up.

Edgar Degas, La Loge, 1880. ©The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Albert Sanchez, photographer

Degas could not see himself in the women he painted. He called the female performers “little monkey girls,” and he depicted their innocence leaving their bodies as their feet cracked and bled while they performed. He extrapolated backward. He could not see the individuality of those who comprised the great scenes at the Garnier. Huysmans found that Degas could translate what he considered society’s “moral decay” into his depicted “venal female rendered stupid by mechanical gambols and monotonous jumps.” Huysmans thought Degas could make the universal into the individual, but they both knew he could not find the individual in the universal.

Edgar Degas, Etude de danseuse le bras tendu, 1895-96. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris © photo Bnf

Opera asks us to manufacture our own empathy. Because it is disjointed, it cannot manipulate emotions like music or movies or television can. With opera, you opt in or out of catharsis. But most of us don’t want to think too hard. To reflect is, almost invariably, to regret. We are all animals in the process of trying to clean ourselves, trying to get our stories straight. The trouble is that we need our stories. We cling to them madly. Go to the opera, tell yourself stories as you must, and leave knowing we’re all the same: our stories have overlapped for centuries, long before these elaborate palaces were erected. Palace of love, of death, of betrayal and of all the rest. The curtain goes up. The curtain goes down. In the end, acting or watching or painting—no matter what side we’re on—we’re all performing for ourselves.

Cody Delistraty is a writer and critic in Paris and New York.

The Cult of the Imperfect

Still from trailer for Casablanca, 1942. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Count of Monte Cristo is one of the most exciting novels ever written and on the other hand is one of the most badly written novels of all time and in any literature. The book is full of holes. Shameless in repeating the same adjective from one line to the next, incontinent in the accumulation of these same adjectives, capable of opening a sententious digression without managing to close it because the syntax cannot hold up, and panting along in this way for twenty lines, it is mechanical and clumsy in its portrayal of feelings: the characters either quiver, or turn pale, or they wipe away large drops of sweat that run down their brow, they gabble with a voice that no longer has anything human about it, they rise convulsively from a chair and fall back into it, while the author always takes care, obsessively, to repeat that the chair onto which they collapsed again was the same one on which they were sitting a second before.

We are well aware why Dumas did this. Not because he could not write. The Three Musketeers is slimmer, faster paced, perhaps to the detriment of psychological development, but rattles along wonderfully. Dumas wrote that way for financial reasons; he was paid a certain amount per line and had to spin things out. Not to mention the need—common to all serialized novels, to help inattentive readers catch up on the previous episode—to obsessively repeat things that were already known, so a character may recount an event on page 100, but on page 105 he meets another character and tells him exactly the same story—and in the first three chapters you should see how often Edmond Dantès tells everyone who will listen that he means to marry and that he is happy: fourteen years in the Château d’If are still not enough for a sniveling wimp like him.

Years ago, the Einaudi publishing house invited me to translate The Count of Monte Cristo. I agreed because I was fascinated by the idea of taking a novel whose narrative structure I admired and whose style I abhorred, and trying to restore that structure in a faster paced, nimbler style, (obviously) without “rewriting,” but slimming down the text where it was redundant—and thereby sparing (both publisher and reader) a few hundred pages.

So Dumas wrote for a certain amount per page. But if he had received extra pay for every word saved would he not have been the first to authorize cuts and ellipses?

An example. The original text says:

Danglars arracha machinalement, et l’une après l’autre, les fleurs d’un magnifique oranger; quand il eut fini avec l’oranger, il s’adressa à un cactus, mais alors le cactus, d’un caractère moins facile que l’oranger, le piqua outrageusement.

A literal translation would go like this:

One after another, Danglars mechanically plucked the blossoms from a magnificent orange tree; when he had finished with the orange tree he turned to a cactus, but the cactus, a less easy character than the orange tree, pricked him outrageously.

Without taking anything away from the honest sarcasm that pervades the excerpt, the translation could easily read:

One after another, he mechanically plucked the blossoms from a magnificent orange tree; when he had finished he turned to a cactus but it, being a more difficult character, pricked him outrageously.

This makes thirty-two words in English, in contrast to forty-two in French. A savings of roughly 25 percent.

Or take expressions such as comme pour le prier de le tirer de l’embarras où il se trouvait (as if to beg him to get him out of the difficulty he found himself in). It is obvious that the difficulty someone wants to get out of is the difficulty he actually finds himself in and not another, and it would suffice to say, “as if to beg him to get him out of difficulty.” More words saved.

I tried, for a hundred pages or so. Then I gave up because I began to wonder if even the wordiness, the slovenliness, and the redundancies were not part of the narrative apparatus. Would we have loved The Count of Monte Cristo as much as we did if we had not read it the first few times in its nineteenth-century translations?

Let’s go back to the initial statement. The Count of Monte Cristo is one of the most exciting novels ever written. With one shot (or with a volley of shots, in a long-range bombardment), Dumas manages to pack into one novel three archetypal situations capable of tugging at the heartstrings of even an executioner: innocence betrayed, the persecuted victim’s acquisition—through a stroke of luck—of a colossal fortune that places him above common mortals, and finally, the strategy of a vendetta resulting in the death of characters that the novelist has desperately contrived to appear hateful beyond all reasonable limits.

On this framework there unfolds the portrait of French society during the “Hundred Days” and later during Louis Philippe’s reign, with its dandies, bankers, corrupt magistrates, adulteresses, marriage contracts, parliamentary sessions, international relations, state conspiracies, the optical telegraph, letters of credit, the avaricious and shameless calculations of compound interest and dividends, discount rates, currencies and exchange rates, lunches, dances, and funerals—and all of this dominated by the principal topos of the feuilleton, the superman. But unlike all the other artisans who have attempted this classic locus of the popular novel, the Dumas of the superman attempts a disconnected and breathless state of mind, showing his hero torn between the dizziness of omnipotence (owing to his money and knowledge) and terror at his own privileged role, tormented by doubt and reassured by the knowledge that his omnipotence arises from suffering. Hence, a new archetype grafted on to the others, the Count of Monte Cristo (the power of names) is also a Christ figure, and a duly diabolical one, who is cast into the tomb of the Château d’If, a sacrificial victim of human evil, only to arise from it to judge the living and the dead, amid the splendor of a treasure rediscovered after centuries, without ever forgetting that he is a son of man. You can be blasé or critically shrewd, and know a lot about intertextual pitfalls, but still you are drawn into the game, as in a Verdi melodrama. By dint of excess, melodrama and kitsch verge on the sublime, while excess tips over into genius.

There is certainly redundancy, at every step. But could we enjoy the revelations, the series of discoveries through which Edmond Dantès reveals himself to his enemies (and we tremble every time, even though we already know everything), were it not for the intervention, precisely as a literary artifice, of the redundancy and the spasmodic delay that precedes the dramatic turn of events?

If The Count of Monte Cristo were condensed, if the conviction, the escape, the discovery of the treasure, the reappearance in Paris, the vendetta, or rather the chain of vendettas, had all happened within two or three hundred pages, would the novel still have an effect—would it pull us along even in those parts where the tension makes us skip pages and descriptions? (We skip them, but we know they are there, we speed up subjectively but knowing that narrative time is objectively dilated.) It turns out that the horrible stylistic excesses are indeed “padding,” but the padding has a structural value; like the graphite rods in nuclear reactors, it slows down the pace to make our expectations more excruciating, our predictions more reckless. Dumas’s novel is a machine that prolongs the agony, where what counts is not the quality of the death throes but their duration.

This novel is highly reprehensible from the standpoint of literary style and, if you will, from that of aesthetics. But The Count of Monte Cristo is not intended to be art. Its intentions are mythopoeic. Its aim is to create a myth.

Oedipus and Medea were terrifying mythical characters before Sophocles and Euripides transformed them into art, and Freud would have been able to talk about the Oedipus complex even if Sophocles had never written one word, provided the myth had come to him from another source, perhaps recounted by Dumas or somebody worse than him. Mythopoeia creates a cult and veneration precisely because it allows of what aesthetics would deem to be imperfections.

In fact, many of the works we call cults are such precisely because they are basically ramshackle, or “unhinged,” so to speak.

In order to transform a work into a cult object, you must be able to take it to pieces, disassemble it, and unhinge it in such a way that only parts of it are remembered, regardless of their original relationship with the whole. In the case of a book, it is possible to disassemble it, so to speak, physically, reducing it to a series of excerpts. And so it happens that a book can give life to a cult phenomenon even if it is a masterpiece, especially if it is a complex masterpiece. Consider the Divine Comedy, which has given rise to many trivia games, or Dante cryptography, where what matters for the faithful is to recall certain memorable lines, without posing themselves the problem of the poem as a whole. This means that even a masterpiece, when it comes to haunt the collective memory, can be made ramshackle. But in other cases it becomes a cult object because it is fundamentally, radically ramshackle. This happens more easily with a film than a book. To give rise to a cult, a film must already be inherently ramshackle, shaky and disconnected in itself. A perfect film, given that we cannot reread it as we please, from the point we prefer, as with a book, remains imprinted in our memory as a whole, in the form of an idea or a principal emotion; but only a ramshackle film survives in a disjointed series of images and visual high points. It should show not one central idea, but many. It should not reveal a coherent “philosophy of composition,” but it should live on, and by virtue of, its magnificent instability.

And in fact the bombastic Rio Bravo is apparently a cult movie, while the perfect Stagecoach is not.

“Was that cannon fire? Or is my heart pounding?” Every time Casablanca is shown, the audience reacts to this line with the kind of enthusiasm usually reserved for football matches. Sometimes a single word is enough: fans rejoice every time Bogey says “kid” and the spectators often quote the classic lines even before the actors do.

According to the traditional aesthetic canons, Casablanca is not or ought not to be a work of art, if the films of Dreyer, Eisenstein, and Antonioni are works of art. From the standpoint of formal coherence Casablanca is a very modest aesthetic product. It is a hodgepodge of sensational scenes put together in a rather implausible way, the characters are psychologically improbable, and the actors’ performance looks slapdash. That notwithstanding, it is a great example of filmic discourse, and has become a cult movie.

“Can I tell you a story?” Ilsa asks. Then she adds: “I don’t know the finish yet.” Rick says: “Well, go on, tell it. Maybe one will come to you as you go along.”

Rick’s line is a kind of epitome of Casablanca. According to Ingrid Bergman, the film was made up piecemeal as filming progressed. Until the last minute, not even Michael Curtiz knew if Ilsa would leave with Rick or Victor, and Ingrid Bergman’s enigmatic smiles were because she still did not know—as they were filming—which of the two men she was really supposed to be in love with.

This explains why, in the story, she does not choose her destiny. Destiny, through the hand of a gang of desperate scriptwriters, chooses her.

When we do not know how to deal with a story, we resort to stereotypical situations since, at least, they have already worked elsewhere. Let’s take a marginal but significant example. Every time Laszlo orders a drink (and this happens four times), his choice is always different: (1) Cointreau, (2) a cocktail, (3) cognac, (4) whisky—once, he drinks champagne but without having ordered it. Why does a man of ascetic character demonstrate such inconsistency in his alcoholic preferences? There is no psychological justification for this. To my mind, every time this kind of thing happens, Curtiz is unconsciously quoting similar situations in other films, in an attempt to provide a reasonably complete range.

So, it is tempting to interpret Casablanca the way Eliot reinterprets Hamlet, whose appeal he attributes not to the fact that it is a successful work, because he considers it to be among Shakespeare’s less felicitous efforts, but to the imperfection of its composition. According to Eliot, Hamlet is the result of an unsuccessful fusion of several previous versions, so the bewildering ambiguity of the main character is due to the difficulty the author had in putting together several topoi. Hamlet is certainly a disturbing work in which the psychology of the character strikes us as impossible to grasp. Eliot tells us that the mystery of Hamlet is clarified if, instead of considering the entire action of the drama as being due to Shakespeare’s design, we see the tragedy as a sort of poorly made patchwork of previous tragic material.

There are traces of a work by Thomas Kyd, which we know indirectly from other sources, in which the motive was only that of revenge; and the delay in taking revenge was caused only by the problem of assassinating a monarch surrounded by guards; moreover, Hamlet’s “madness” is feigned, the aim being to avert suspicion. In Shakespeare’s definitive drama the delayed vengeance is not explained—with the exception of Hamlet’s continuous doubts, and the effect of his “madness” is not to lull but to arouse the king’s suspicions. Shakespeare’s Hamlet also deals with the effect of a mother’s guilt on the son, but Shakespeare was unable to impose this motif upon the material of the old drama—and the modification is not sufficiently complete to be convincing. In several ways the play is puzzling, disquieting as none of the others is. Shakespeare left in unnecessary and incongruent scenes that ought to have been spotted on even the hastiest revision. Then there are unexplained scenes that would seem to derive from a reworking of Kyd’s original play perhaps by Chapman. In conclusion, Hamlet is a stratification of motifs that have not merged, and represents the efforts of different authors, where each one put his hand to the work of his predecessors. So, far from being Shakespeare’s masterpiece, the play is an artistic failure. “Both workmanship and thought are in an unstable condition … And probably more people have thought Hamlet a work of art because they found it interesting, than have found it interesting because it is a work of art. It is the Mona Lisa of literature.”

On a lesser scale, the same thing happens in Casablanca.

Obliged to invent the plot as they went along, the scriptwriters threw everything into the mix, drawing on the tried and tested repertoire. When the choice of tried and tested is limited, the result is merely kitsch. But when you put in all the tried and tested elements, the result is architecture like Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia: the same dizzying brilliance.

Casablanca is a cult movie because it contains all the archetypes, because every actor reproduces a part played on other occasions, and because human beings do not live a “real” life but a life portrayed stereotypically in previous films. Peter Lorre drags behind him memories of Fritz Lang; Conrad Veidt envelops his German officer with a subtle whiff of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Casablanca pushes the feeling of déjà vu to such a point that the viewer even adds elements to the film that only appear in later films. It wasn’t until To Have and Have Not that Bogart took on the role of the Hemingway hero, but here he “already” reveals Hemingwayesque connotations for the simple fact that Rick has fought in Spain.

Casablanca stages the powers of narrativity in the natural state, without art stepping in to tame them. And so we can accept that characters have changes of mood, morality, and psychology from one moment to the next, that conspirators cough to break off their talk when a spy approaches, and that ladies of the night weep on hearing “La Marseillaise.”

When all the archetypes shamelessly burst in, we plumb Homeric depths. Two clichés are laughable. A hundred clichés are affecting—because we become obscurely aware that the clichés are talking to one another and holding a get-together. As the height of suffering meets sensuality, and the height of depravity verges on mystical energy, the height of banality lets us glimpse a hint of the sublime.

—Translated from the Italian by Alastair McEwen

Umberto Eco (1932–2016) was an internationally acclaimed writer, philosopher, medievalist, professor, and the author of the best-selling novels Foucault’s Pendulum, The Name of the Rose, and The Prague Cemetery, as well as children’s books. His numerous nonfiction books include Confessions of a Young Novelist, Six Walks in the Fictional Woods, and The Open Work. He was a recipient of the Premio Strega, Italy’s highest literary prize; the Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities; and a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur from the government of France.

Alastair McEwen is an award-winning literary translator. After nearly forty years in Italy he now lives in his native Scotland.

Excerpted from On the Shoulders of Giants , by Umberto Eco, published by Harvard University Press. English translation copyright © 2019 by La Nave di Teseo Editore, Milan. Published in the United States by Harvard University Press, 2019. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

October 25, 2019

Spooky Staff Picks

Keon-kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo) in Parasite. Courtesy of Neon and CJ Entertainment.

On a dark and stormy night earlier this week, I made my way to see Bong Joon-Ho’s much-lauded new film Parasite. I was on edge the whole way there—frankly, I’ve been on edge since seeing the phenomenal trailer, and the anticipation, it seems, was getting to me. At the theater, the preshow jostling and chatter was at a minimum. We awaited the start of the film—and the twist we knew must be coming—with bated breath. I was surprised, however, by how quickly I felt myself and those around me exhale. The movie’s opening introduces us to the struggling Kim family as they craftily invite themselves into the stylish home of their immensely wealthy counterparts, the Parks. The Parks are profoundly, hilariously gullible, and Bong allows us to delight in their naïveté. There are a few ominous moments early on, but it hardly felt as if we were about to launch into a thrilling story of vast inequality and the horror and violence it yields. But then, of course, we did. Capitalism is terrifying. Happy Halloween. —Noor Qasim

You remember The Shining. You know how scary it is. Reader, you’re wrong. It’s so much scarier than you remember, with freaky shots you never noticed the first few times you watched. The scene with the twins? You know the one, in the hallway, with them alive and then, all of a sudden, horrifically and brutally murdered? Look closer: from shot to shot, their stomachs move; they’re breathing. You thought you were seeing them dead. You’re seeing them dying. This is one of the myriad reasons I suggest you rewatch The Shining this holiday season. If dead children and a renewed fear of showers don’t wholly entice you to pop this baby on, know that this movie is also hilarious. Jack Nicholson’s chaotic interview with the hotel owner could be an SNL sketch. It’s an unforgettable film, but trust me, you forgot some of the best parts. —Eleonore Condo

Photo: Charleswallacep (CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)).

On a stormy day in early October, a copy of The Best American Mystery Stories 2019 appeared on The Paris Review shelves. Waiting for the rain to break, I picked it up and leafed through, landing first on Reed Johnson’s “Open House.” The story begins when an ominous man arrives at the door of a family’s home. It turns out he is an ICE agent who has come to search the home in connection with a crime, and things get darker from there. I took the book home, where, for the past few weeks, it has lived on my nightstand, and I’ve been reading a story or two each night in the dusky hour between when I should be asleep and when I am. Murder, it turns out, makes for good bedtime reading. The stories are fast-paced, dark, and deeply satisfying. They also feel timely, with nods to the inherent horror of mass incarceration, immigrant detainment, and internet anonymity. My favorites, though, are the more classic whodunits, populated with shadowy characters, train cars, and gumshoes in trench coats poking around empty apartments or questioning suspicious bartenders, only to find that the culprit was right under their noses all along. “Crime stories,” writes Jonathan Lethem, the editor, in his engaging introduction, “are deep species gossip. They’re fundamentally stories of power, of its exercise, both spontaneous and conspiratorial; stories of impulse and desire, and of the turning of tables.” The Best American Mystery Stories series was established in 1997 under the auspices of Otto Penzler, a veteran of the genre and the owner and proprietor of the Mysterious Bookshop in Tribeca, a perfect place for the bookish to indulge their spooky side and hide out for Halloween. —Cornelia Channing

Writing and a belief in the occult seem like natural bedmates—just look at James Merrill and his Ouija board, or Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes poring over each other’s birth charts. In the past few years, I’ve been reading tarot cards, and I find them fascinating in how they combine archetypes, myth, and storytelling in an attempt to capture the ineffable. If you, too, are interested in tarot, I recommend signing up for 22 Moons, a free newsletter from the small press Ignota Books that, in their words, is “delivered on each New and Full Moon, bringing together 22 poets, writers, artists, musicians, thinkers, curators, astrologers, practitioners, witches and scientists for 22 lunations.” So far, there’s been The Hierophant, The Moon, Judgement, The High Priestess, and The Tower, and each has been helpful or interesting in its own way. —Rhian Sasseen

M. Night Shyamalan earned a reputation for landing his movies on a plot twist, and the gimmick has in many ways clouded how worthwhile his work can be. The Village is a parable, rich with satisfying folkloric embellishments, about how the narratives we tell ourselves subsume reality; it is also a tense and exciting monster movie. Signs plays with peering into the dark, and like all good writers of fear, Shyamalan is careful about obstructing our view and letting our imaginations do the work (the final scene breaks away from this operating principle and is weaker for it). He does the same thing to his characters, isolating them with the unknowable: what lives in the woods, how much of civilization remains, whether we can communicate with the dead. At his best, Shyamalan aligns as closely as possible what his characters know with what the viewer does. When the big reveal happens, fear is alleviated as pieces fall into place and the characters’ gratification becomes our own. —Lauren Kane

M. Night Shyamalan at San Diego Comic-Con, 2018. Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)).

October 24, 2019

Feminize Your Canon: Iris Origo

Our column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors.

Iris Origo (courtesy La Foce)

Iris Origo might be the most self-effacing writer ever to gain renown as a diarist. Her reputation rests on her unique perceptions of others. As an aristocratic landowner in mid-twentieth-century Italy, she bore witness to all strata of Italian society during the long rise and precipitous fall of fascism.

The external circumstances of her life were unquestionably extraordinary. She participated in the final glittering years of prewar Europe’s cosmopolitan society; transformed a region of Italian countryside into a home still visited today for its beauty; and housed, during World War II, escaped prisoners and fleeing refugees. Her writing about this time evinced truths rarely seen in the narratives of historical texts, and did so through illustrative anecdotes that captured the people of the period and what they were feeling. In her diary of the years leading up to the war, A Chill in the Air, there is, for instance, an ever-increasing sense of being shut off from the rest of the world. Letters from England arrive a month late. What little reading material people can access becomes restricted. Origo recounts meeting, at a dinner party, a grad student who spends his nights, with fellow students, sitting up copying by hand an illicit New Republic essay about dictatorship. Iris writes of him, “I wish I could convey his odd mixture of childish pride at belonging to ‘the minority’ of real intelligence, and of something very sincere and tragic.” More than simply remain an anecdote about censorship, her observation captures the tragic paradox of this young man’s pride and sincerity, and his powerlessness in the face of what is to come.

A Chill in the Air and the diary that originally made Origo famous during her lifetime, War in Val d’Orcia, both belong to a retinue of Origo works being reissued by New York Review Books. The NYRB has followed up the diaries by publishing Images and Shadows, Origo’s autobiography, this month. Both volumes of diaries were reissued in 2018, two years after Donald Trump’s election and amid the widespread sense that Americans stood to learn something from the rise of fascism. Origo shows us the complacency of the upper classes, the questions over what news is true or false, which bears uncanny resemblance to our own era.

Origo’s autobiography shows that her reticence on personal matters ran deep. Comparing it with Caroline Moorehead’s definitive biography, Iris Orgio: Marchesa of Val d’Orcia, displays an extensive gallery of omissions. Origo had, over the course of her life, three passionate and protracted affairs with men who get no mention in her autobiography. But her hesitation to talk about these relationships is not simply out of propriety; Moorehead also uncovers an intense friendship with a woman named Elsa Dallolio that was a major part of Origo’s late life. Her unwillingness to allow her intimate relationships into her autobiography exemplifies how Origo was always least interested in herself as a subject. She shifted her focus entirely to the people around her, and it was as much a benefit to her diaries as it was a detriment to her autobiography. But ultimately, her reserved narrative voice produced empathetic, sensitive work that uniquely illuminates a crux of modern history.

*

Origo’s youth was marked by wealth and constant travel. She’d later treasure memories of a brief, early period of childhood spent between family estates on Long Island and Ireland. When her father, Bayard Cutting, was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the family embarked a consumptive’s grand tour, hoping the next sanatorium in Saint Moritz, then California, then Egypt, would bring Bayard back to health. He died at age thirty, when Iris was seven years old. Bayard gave her mother, Sybil, instructions for continuing his daughter’s peripatetic regimen, now as a matter not of necessity but of principle: “All this national feeling makes people so unhappy. Bring her up somewhere where she does not belong, then she can’t have it.” He wanted Iris to be “free to love and marry anyone she likes, of any country, without its being difficult.” His wish was met, and as a result Iris would always feel an outsider wherever she was.

Her adolescence presented her with a confusing jumble of cultural styles. She lived in Florence, but among fashionable English expats. She survived an exhausting series of debutante seasons across Europe and in the U.S. Without feeling any one set of morals and manners to be natural, she felt out of place everywhere. In young adulthood, it was a recipe for social alienation. Later, however, this experience would give to Origo’s career as a writer the power to notice what others took for granted.

As an eighteen-year-old debutante, Iris met Antonio Origo, and they were soon engaged. In some ways, Origo’s passage into married adulthood represented a rejection of her youth. Both Iris and Antonio found in their marriage a “strong reaction” against their prescribed paths: Iris against society life and Antonio against the career in business that he had been trained for. In 1924, they bought La Foce, a sweeping estate in Tuscany still operating under the feudal system. The previous landlords had been heedless, and the people were starving on arid land, alienated from the comforts of modern life.

The Origos approached the neglected landscape as an opportunity to undertake a project in the service of the less fortunate. It was what they’d been looking for: “enough work for a lifetime.” In this difficult, remote, rural landscape, Origo seemed to find the self-possession she had been lacking, a place where for the first time her actions were not determined by societal strictures. It was at La Foce where Origo decided to be a writer and began producing acclaimed biographies of important figures from Italian cultural history.

Origo’s first and abiding writerly pursuit was biography. Among her subjects were the poet Giacomo Leopardi, the Franciscan priest Bernardino of Siena, and a fourteenth-century merchant banker; she also produced a dual biography of Lord Byron and his daughter. She gave herself a professional credo: “The biographer who puts his wit above his subject will end by writing about one person only—himself.” The results were discreet, meticulous books that garnered appreciation, but not lasting significance. Yet that same quality, when applied in her diaries to the everyday reality of fascism and war, gave the pulse of an entire people, capturing in a sort of group biography the experience of the Italian people.

War in Val d’Orcia was a success upon its publication in 1947. Origo published the diary as a way of quelling the lingering animosity felt by England for Italy. It is packed full of facts, displaying the historian’s rigorous attention to the concrete realities of war. Her anecdotes and observations demonstrate that the hardships suffered by Italians during the war were similar to those of the English, such as living in fear of bombing, and the opposition to fascism felt by many. The diary crackles with excitement—but in leaving out Origo’s own voice, Val d’Orcia exhibits an archival density that stifles the pathos at the heart of what is happening.

A Chill in the Air, conversely, was never intended for publication at all. As a result, Origo seems less intent on capturing every instance of conflict. The diary is not as dense with action, but it lingers more freely on the poignancy of fleeting moments and ordinary people. In that sense, it is the consummate achievement of Origo’s distinctive style. As a record not of World War II itself but of the rising forces of political illiberalism, it also offers a more direct parallel to our own time. It offers us a way of peering through a keyhole in the locked door of history, to understand the people in the situation that might soon become our own, not only as a warning but as a way of knowing that we are not unique, or alone.

A Chill in the Air begins in 1939 on a train to Rome crowded with Fascist squadistri. Origo is in a car with six of them, “stoutish, with their black shirts bulging at the waists.” The atmosphere among soldiers is like that of a “college reunion” as the men talk about what has been accomplished over the two decades of Fascism. Several days later, Origo is in a crowd of people listening to Mussolini over a speaker: “the guarded, colourless expression on most of the men’s faces—and the undisguised anxiety in the women’s.” Origo’s evocations of the crowd are vivid, and they imbue the inscrutable mythos of Fascism with humanity and individualism.

And yet her own feelings and anxieties are absent from the text. At a crucial moment just a month before war is declared, Origo and Antonio are traveling over the Swiss-Italian border. As they wait at the customs checkpoint, they see an Italian car heading for the Swiss border get turned away and sent back by the paramilitary. An officer returns their passports with a smile. “No more Italians jaunting abroad now!” he said. “Come in, and stay in!” As their car pulls away, Iris watches as “the pole of the barrier swung slowly back behind us.” The false cheerfulness of the guard followed by the dark omen of the closing gate echoes the dread that Origo may have been experiencing, but if so, the feeling goes unspoken; even remembering this incident again in her autobiography, she says that revisiting the moment brought back feelings “very vividly”—but we are meant simply to trust her, as the details of those feelings are never articulated.

A large part of War in Val d’Orcia records how the Origos transformed their estate into a checkpoint for fleeing prisoners of war and refugees. Had they been discovered, they would almost certainly have been executed. However, the dire stakes are often second to the recording of violence and disruption in their region. The most remarkable moments of pathos are those in which Origo records stories heard secondhand. An art historian smuggles paintings by Piero della Francesca down routes that are shaken with bombings. A boy of nineteen in Florence refuses to report for military service and is sentenced to death: he “faced the firing squad, unbound, with unflinching serenity, reciting ‘Our Father.’ On the following Sunday the Prior of San Miniato, in his sermon, mentioned the death of these three young men as a remarkable instance of Christian faith and courage, and was promptly arrested himself.” There is a timelessness to Val d’Orcia—reading it today has the same effect it did in the forties. We experience the war years not from the global stage of action but through the experience of the common Italian people.

*

Iris Origo, however, was not a political activist. Her and Antonio’s elevated social position entangled them financially and socially with Fascism. Mussolini’s agricultural subsidy program, the Bonifica Integrale, made La Foce into a case study, a fact recounted in Moorehead’s biography that gets only glancing mention in Images and Shadows. A Chill in the Air mentions Origo staying with friends, the Sennis—Catholics with aristocratic Italian lineage who are “all Fascists, but they are Catholics first.” She writes about Carlo Senni as a man loyal to Mussolini, a man whose “personal ascendancy” is built on the backs on “underlings” who know they will be “kicked away as soon as they cease to be useful.” Her critical assessment of his character is veiled; she follows with an entry about reading an article about the evils of anti-Semitism, which she agrees with. Her reactions to the world around her never accumulate to a direct rejection or condemnation of what she recognizes as evil.

The title of Origo’s autobiography is a signal to the reader not to expect a clear picture. The chronology of Images and Shadows is scattered, skipping back and forth to accommodate a full history of her ancestry; not until past a hundred pages does it move into Origo’s childhood in Fiesole. The reticence that created such a titillating narrative voice in her diaries has somehow gone stale. Images and Shadows becomes largely philosophical, with the chapter “On Writing” beginning, “Why does one write at all?” The best way to read Images and Shadows is to immediately follow it up with Moorehead’s biography, to watch the subject come alive. Why did Origo write at all? It seems a rare thing for a person with such an abiding interest in the personal to be so absent from the page. She was never a firebrand, in her writing or in her life. Her actions were pastoral rather than revolutionary; her reticence was rooted in the old-world domesticity she came from, which never quite left her. The resulting impulse was to subsume herself in deference to others; with this empathy she put those who would have otherwise gone unnoticed down to paper. Her father had hoped to free her from national feeling, and in many ways, he did; that freedom brought her to make a place home, all the same: La Foce, the people of Italy. What of herself she found, she found there.

Read earlier installments of Feminize Your Canon here.

Lauren Kane is a writer who lives in New York. She is the assistant editor at The Paris Review.

October 23, 2019

Just Enjoy Every Fucking Blessed Breath

Photo: Kate Simon

It’s hard to imagine Nick Tosches ever having been young. His interests, the way he dressed, the language he used, his love of cigarettes—everything about Tosches was out of time. He wasn’t so much from a different era as he was from a different sensibility, one that refused to distinguish between highbrow and lowbrow, didn’t countenance small talk, wore ties and stood when a lady entered the room, but also trucked in ethnic slurs. He saw no contradiction in being both courtly and vulgar.

Tosches, who died on Sunday at the age of sixty-nine, began his writing career as a record reviewer for Creem and Rolling Stone. Throughout the seventies, he wrote about music with audacious flair, mixing Latin phrases and Biblical themes with a sailor’s vocabulary. Album reviews couldn’t hold him, and in 1988 he published his first novel, Cut Numbers, about a loan shark.

In 2012, he published Me and the Devil, a novel about a writer named Nick who lived in the same downtown New York neighborhood Tosches lived in, and had the same opinions, friends, and outlook, and who regained his waning vitality by drinking the blood of young women during violent sexual bouts. “It’s the vampirism of trying to regain something of youth through young flesh,” he said when I visited him, on a magazine assignment, in his brick-walled apartment. We talked for two hours, sometimes about his book, but more often about vanity, technology, illness, how New York had changed, and old age. Tosches was observant, restless, and hilarious. Our conversation remained unpublished—here’s a small part of it, in tribute.

INTERVIEWER

I think this is a book that no one under the age of forty or fifty could have written.

TOSCHES

No matter how gifted, or what powers of imagination they had, no one under forty or even fifty could pull it off. It’s a book about aging as much as it is about anything else. And seeing the world change. It’s a book about love. And it’s always, in a way, about books, because there are certain small parcels of ancient wisdom I’ve been fortunate enough to discover through the years, and have held closely. And I keep trying to spread them. I don’t even know if people are looking for wisdom these days.

INTERVIEWER

I think people are looking for better cable TV service.

TOSCHES

You’re right! Or the smart phone with the next gizmo. And that says a lot. It’s like everybody’s afraid to die, but how often do you hear, Oh, I can’t wait until this week is over? You want to get closer to what terrifies you most. Through writing a book, I get close to what scares me about myself. People just … they’re not really living. It’s just a certain—this breath is really the only thing we have. That’s it, you know? That’s it.

INTERVIEWER

Abbie Hoffman once said, “They tell you when you get old, you get wiser. You know what you get? You get hemorrhoids.”

TOSCHES

Well, I had hemorrhoids when I was nineteen and really rocking, so I don’t know what the hell he was talking about. He was a guy who couldn’t get enough attention, so he killed himself! Talk about not living your life! He just had a fabricated life. He didn’t know what to do with the real one.

I just know that the world is going more insane. One consolation, one good part about getting much closer to the grave than to the cradle, is that the feeling of being a speck in the universe, which we all are, doesn’t bother me one bit. I never, ever thought I’d outlive civilization! Which I think I’ve already done. And it feels great!

INTERVIEWER

When did the decline of civilization begin?

TOSCHES

I think it’s fallen apart in the last … like, right now. As we speak, it’s just going to hell. The whole thing is going down, and I like it. I like watching people get stupider and stupider, ‘til they couldn’t tell if they were getting raped unless their fucking phone rang and someone across the street told them.

INTERVIEWER

I mentioned Abbie Hoffman in order to say that getting older is always a surprise to people. We’ve seen our grandparents and parents get older, yet it’s still a surprise when it happens to us.

TOSCHES

Well, up to a point, it’s virgin territory, and it’s like, Oh, this is going to go on forever, except that life is going to get better. And then you realize that it doesn’t. If you live the right way—and the right way to me would be considered the wrong way by many—you do gain a good outlook, and it comes down to this—it doesn’t pay to worry. It doesn’t pay to give a fuck. Because ninety-nine percent of what you worry about ain’t never gonna happen. What’s gonna happen is gonna come over your left shoulder and just do you in.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write this book, among other things, to work out your understanding of being older?

TOSCHES

Yeah.

INTERVIEWER

So what’s your current understanding?

TOSCHES

Just enjoy every fucking blessed breath. Just enjoy it, because it’s not getting better. Even at the senior rates, I don’t go to movies. I derive my entertainment from bad news. It’s perverse but it’s funny. It’s so fuckin’ funny to overhear people, to observe people. It’s a riot. I don’t like to read newspapers or watch the news. It’s all right here. I just walk out on the street, and there it is.

Rob Tannenbaum writes about music and pop culture for the New York Times, LA Times, New York Magazine, and other publications. He is the coauthor of I Want My MTV, which has been optioned by A24.

The Deceptive Simplicity of Peanuts

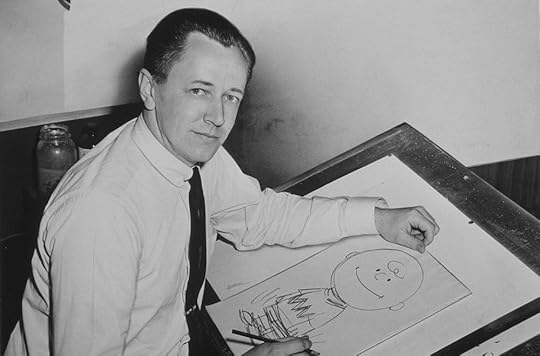

Charles M. Schulz. Photo: Roger Higgins for the New York World-Telegram and Sun. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Schulz exposed me as a fraud. Nearly two decades ago, upon hearing of Mr. Schulz’s impending retirement, I drew a clumsy comic strip tribute to Peanuts, fancying myself a halfway-decent mimic. I attempted to copy the strong, fluid lines of his mid-’50s work, which I long admired (idolized), but I quickly realized that I was going to fall far short. I could only scratch the surface of his inimitable drawings—as natural as handwriting, but even harder to forge—much less the emotional content he could pack into every molecule of ink. And anyway, the veneer is never the thing itself. You know how sometimes you might hear what sounds like a simple melodic line in, say, Mozart, and then you see the actual sheet music, which reveals an unfathomably complex, rich structure, an eternity condensed into tiny, elusive black marks flowing through, over, under, and beyond the staves, swimming like furtive cells viewed under a microscope, seemingly unfixed and unfathomable yet cohering into a unified and inextricable whole, all of this therefore outing you as an arrogant, deluded, oblivious fool? That was me.

While I hadn’t been drawing comics for very long at that point, I should have known better. A teacher in high school once explained that drawing was simply observation; thirty-five years later, that still seems like a pretty thorough definition. For starters, I wasn’t observing keenly or deeply enough. Even though in my pastiche/homage I was “drawing a drawing,” I hadn’t fully understood what I was looking at, because cartooning exists in a kind of liminal space somewhere between writing and drawing. Sure, one could imitate the telltale twirl of a brush winding its way through a stroke, or calculate the pressure applied to a nib traveling along a particular vector, but there was also something ineffable about comics, something more than the sum of its parts.

At the time, I had recently become good friends with Chris Ware, who articulated quite eloquently the difference between drawing and drawing comics. I had an inkling of what he meant, but it wasn’t until I tried copying Schulz that I experienced comics as a special kind of calligraphy, formed and informed not only by an iconic mental map of the world but also by the intensity of life lived, the depth of feelings felt. Charlie Brown is simultaneously a beautifully proportioned, abstracted assemblage of marks; a conceptually pure and original character; a true expression of Schulz; and, through the act of reading Peanuts, a way also to understand myself. To communicate so much to so many, with so little, as Schulz was able to do with Peanuts, takes a lifetime of practice, persistence, determination, focus, stamina, and dare I say: obsession. Dilettantes and imposters easily betray themselves.

The genius of Peanuts is that it seems simple, replicable. But simplicity and complexity are arbitrary categories; where is the a priori boundary that separates one from the other? The true undergirding of lasting works of art is the embrace of contradictions, and Peanuts is no exception: it is at once universal and idiosyncratic, miniature and vast, constrained and infinite, composed and improvised, claustrophobic and inviting, caustic and sentimental, funny and sad.

Moreover, what a wonderfully strange strip it is, this internal world playacted by ciphers. A playwright famously noted that every character is the author, and Peanuts exemplifies this truth. Via the interactions of these captivating characters (themselves full of contradictions, with their own internal conflicts), we are inside Schulz’s splintered psyche—unbeknownst to us, because it never feels that way as we read the strip; the content isn’t self-conscious or pretentious or “meta.” Despite the small, tight, even dense panels, Schulz wisely keeps at us at eye level with the characters, and thus we can easily enter a rectangle of Peanuts and imagine ourselves roaming along with the characters inside what paradoxically seems a boundless world; maybe this is what it feels like inside Snoopy’s doghouse. We inhabit the drama (by which I mean comedy) as it unfolds, following these characters as if they were real people, despite their outsize heads, squiggly arms, and occasional graphic flourishes.

Peanuts has no discernible scale, because it exists simultaneously as small increments and a fifty-year totality, an epic poem made up entirely of haikus. Then again, maybe that’s also what life is: short, packed moments of intense, concentrated awareness, minuscule epiphanies that accrete as we age, an accumulation of efforts, some meaningful and some meaningless, moments all too real that unsettlingly feel somehow also not real, jottings taking note of everything, within and without. One life, all life. An isolated four-panel comic strip of Charlie Brown and Linus debating a philosophical point can be appreciated just as it is, humorous, insightful, compact, and perfect; one strip a day documenting one man’s thoughts for half a century has the weight of a full life. Peanuts endures, both from the closest micro-view and the farthest macro–vantage point.

Likewise, time also doesn’t really exist in Peanuts. Maybe that’s not the best way to put it. To be sure, the action always unfolds in a linear fashion, with dialogue often driving the action (dialogue perforce functions as a transcript of time). And there are surprisingly a greater number of topical references than might have stuck in one’s memory of the strip. What I mean by time “not existing” is that Schulz is reliving his past, revising it into his characters’ constant present. They aren’t children who speak as adults, nor adults inhabiting child costumes. The characters and all that transpires in the strip are the sum total of one man’s mind, memory, experience, history, speculations, and dreams, a self-contained universe revealing itself as if it were a slowly exploding singularity.

Take two: We are the same person from childhood to death, but we are always in flux, reacting to unpredictable stimuli, a little different after each experience, perhaps worse for the wear. We don’t look the same from year to year, certainly not decade to decade, and our memory is imperfect (to put it kindly). We know there are ebbs and tides and biological upheavals as we age, but deep down we know we have always been one and the same person, the same one we are now and will continue to be. There is a continuity that seems odd to me. Is there a latent self that exists in perpetuity, a Platonic version of each individual, that briefly flickers on planet Earth? Peanuts, too, captures this odd sensation: Charlie Brown in 1950 looks quite different from Charlie Brown in 2000, but we always know it’s the same Charlie Brown and, weirdly, that there exists a Charlie Brown.