The Paris Review's Blog, page 197

November 27, 2019

Behind the Scenes of ‘The Paris Review Podcast’

The second season of our celebrated podcast is here to carry you away from all the troublesome sounds of Thanksgiving squabbles. And if you’d like to know how something so excruciatingly exquisite gets made, read on for a behind-the-scenes interview with executive producer John DeLore. He is a senior editor and tenured audio engineer at Stitcher’s NYC studio. In addition to The Paris Review Podcast, he has worked on Stranglers, Beautiful/Anonymous, The Longest Shortest Time, Couric, Clear + Vivid with Alan Alda, Fake the Nation, The Sporkful, and Household Name. He answered some questions from our engagement editor, Rhian Sasseen, about his preferred microphones, the differences between Season 1 and Season 2, and how to respect both the language and the listener.

INTERVIEWER

In the spirit of the many times “pencil versus pen?” has been asked in The Paris Review’s Writers at Work interviews, what’s your preferred setup for recording?

JOHN DELORE

Most of the process is not a solitary craft. And while a lot of recording happens in our studio where we’ve got our preferred tools and our studio vibe, a lot of it is happening out in the world, or “in the field,” as they say.

And for me, I’m sort of always “in the field.” I’ve had the same silver Zoom H2 portable recorder for almost ten years, and I carry it just about everywhere I go. And these days I’ve been using the iPhone VoiceMemo app. It’s like a butterfly net. I hear something in the world, like a train on an elevated track, or a nice bird, or a thunderstorm, and I capture it. I label it and throw it in this massive folder of random sounds.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a particular type of, say, microphone you gravitate toward over all others—or are only writers this superstitious about the tools they use?

DELORE

When I will be more intentionally hunting down sounds, in those cases I’ve got a more proper setup. My Sennheiser shotgun mic with a pistol grip and a big wind cover, plugged into a more robust recorder. And then there are other situations, where I’m lugging around a suitcase of gear, like the time Jamaica Kincaid invited me into her home to record her reading and discussing her work. I packed extra mics, cables, an extra recorder, an excessive amount of AA batteries. Those are the situations where you’ve got one shot to capture that moment in time, and in those cases it’s less about “superstition” and more about discipline and preparation.

If someone reading this is not interested in specific technical details, then jump to the next question. For the rest of you, here’s a little bit of detail.

In the studio we use Shure Sm7B microphones. I’ve always liked the way they sound. They don’t add any color to the sound, and it’s a very straightforward and clean-sounding mic. In the field I like a Sennheiser MKE #600 shotgun paired with a Zoom H5. The H5 lets you simultaneously record a stereo image with the built-in microphones while also recording the shotgun mic onto a third track. The stereo image can go a long way in terms of making the listener feel they’re surrounded by a place.

The shotgun mic is designed with a “throw” so you can capture good direct sounds without being right next to the source. These are used in movie shoots. They’re the mics that boom operators are holding above the actors’ heads, just outside the camera frame. In the first season, when you hear Jamaica Kincaid talking about the birds in her backyard, I think I was about six feet away from her using the shotgun mic.

That “throw” also makes the shotgun very useful in the field because you can put it on a coffee table or a desk a few feet from a speaker and still get a full-sounding recording. That smaller desktop mic stand is also much more portable. But if I’ve got a car, or a budget to expense a taxi, I’ll sometimes bring a Neumann KMS #105, which is a really great sounding microphone. But that mic requires more proximity to the speaker’s mouth to get the full-spectrum sound, so it requires bringing a bigger mic stand. So sometimes a technical decision is made based on the fact that I’m riding the subway and I don’t want to carry all the extra stuff. Okay. Nerd alert over. Next question.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any favorite moments from recording or editing Season 2?

DELORE

For this season, I was there for the Alex Dimitrov in-studio session. It was actually the very first thing we recorded for this season. His poem “Impermanence” is really beautiful. It’s one of those poems where the personal aspect gradually moves into this bigger, more abstract and more indefinable space.

I remember reading it, and it’s one of those poems where you read it, then you reread it, and when it’s on the page you can linger on different stanzas or lines for as long as you like. But when it’s put into a podcast, all that subjective patience disappears. Everyone is now locked to the same timeline. So when we recorded that poem, and all the other works, we spent a little time trying to find the right pacing for a few choice moments, to create a listening experience that gives folks room to digest and enjoy the progress of the poem.

Of course, we also try to get a little bit of ephemeral interview tape from our readers, and Alex gave this really beautiful answer to Emily Nemens’s question, “Why do you write poetry?” His poem and his answer are in the first episode, so if you’re curious to hear his answer, by all means, subscribe to the podcast right now!

INTERVIEWER

The relationship between writing, editing, and reading is clearly a source of continued fascination and relevance within the pages of The Paris Review. Did you approach editing Season 2 differently from Season 1?

DELORE

For us, editing often means taking all the raw tape and editing the best takes together. Sometimes we have a reader try a line a half dozen times, just to have options. After we have the audio all edited together, we start adding sound design and scoring. Those decisions will often alter the pacing of the read a bit. For example, if there’s a particularly emotional section in the middle of a story, we’ll let the music post for a solid moment, maybe as long as ten to fifteen seconds. In the audio version, we create pockets of space to leave room for listeners to process and digest an idea or an emotion. Sometimes it’s just a second or two, but other times it’s a longer moment of scoring.

I think that in both seasons we’re abiding by the same general principle of respecting both the language and the listener. We’re presenting a lot of really beautiful language—as well as some really complicated language—so we need to create a space where the listener has room to process in real time, and where the language is supported by the vocal performance, the pacing we create around the read, and the scoring and sound-design choices we make to underline the read. To me, Season 2 feels a bit more like the pieces are in conversation with one another. Less themes, more echoes.

Read more behind the scenes interviews. Producer Helena de Groot delves into the art of interviewing, executive producer Brendan Francis Newnam discusses the finer points of recording and producing, and composers David Cieri and Emily Wells talk about scoring Seasons 1 and 2.

November 26, 2019

Redux: One Empty Seat

Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

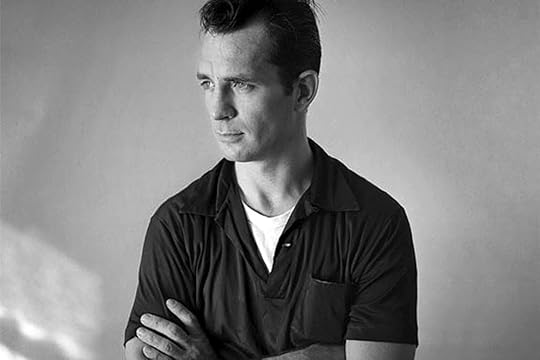

Jack Kerouac, ca. 1956. Photo: Tom Palumbo.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about travel—by train, plane, car, or bus. Read on for Jack Kerouac’s Art of Fiction interview, W. S. Merwin’s essay “Flight Home,” and Paulé Bártón’s poem “The Sleep Bus.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Jack Kerouac, The Art of Fiction No. 41

Issue no. 43 (Summer 1968)

I spent my entire youth writing slowly with revisions and endless rehashing speculation and deleting and got so I was writing one sentence a day and the sentence had no FEELING. Goddamn it, FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings.

Flight Home

By W. S. Merwin

Issue no. 17 (Autumn–Winter 1957)

They say that after seven years every cell in your body has changed. You are a different person.

I wish I could remember what day it was, in July 1949, that I landed in Genoa. Or the day (one or two days before?) when we first came in sight of the Spanish coast.

Strange, now I am going back, to think that I have been in Europe without a break, ever since I was a minor. Ever since I was twenty-one.

The Sleep Bus

By Paulé Bártón

Issue no. 70 (Summer 1977)

I get on

the racket bus,

and see one empty seat

next to a burlap-face

mongoose

in a cage …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

Redefining the Black Mountain Poets

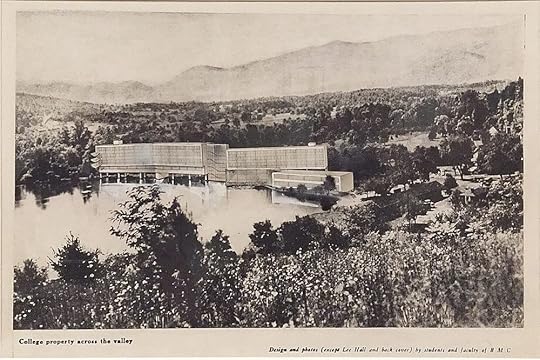

Drawing of project for Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. Architectural design by Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius. Photo of original work taken in Harvard Art Museums. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Grouping writers into “schools” has always been problematic. The so-called Black Mountain poets never identified themselves as such, but the facts of their union spring from a remarkable instance of artistic community: Black Mountain College and the web of interactions the place occasioned. Founded in the mountains of western North Carolina in 1933 and closed by 1956, the college was one of the most significant experiments in arts and education of the twentieth century. In recent years, a number of international exhibitions and publications have showcased the range of artwork produced at the college’s two campuses, the first situated in the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly, and the second at Lake Eden in the Swannanoa Valley. The list of famous names associated with Black Mountain is as impressive as it is unlikely, given that the college never housed more than a hundred students and faculty at a time, often far fewer.

Difficult questions persist in attempting to define a “Black Mountain” school of poets. Do we look to the physical and historical circumstances of Black Mountain College, or the complex pattern of friendships, influence, correspondence, publication, and collaboration that constitute the broader notion of this artistic coterie?

Charles Olson, the nucleus of what we have generally considered Black Mountain poetry, began teaching at the college in 1948 and became its final rector in 1953. In 1954, he brought Robert Creeley—Olson’s “Figure of Outward”—to Black Mountain. By that time there were fewer than twenty students in residence. However, through a network of relationships and correspondence emanating from Olson’s “little hot-box of education,” the instigations of Black Mountain College made an impact on artistic circles in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and elsewhere. The “open field” poetics of Olson, Creeley, and Robert Duncan in particular have influenced generations of poets. Still, the supposed Black Mountain school of poetry is difficult, if not impossible, to define. Olson said himself,

I think that whole “Black Mountain Poet” thing is a lot of bullshit. I mean, actually, it was created by the editor, the famous editor of that anthology, Mr. Allen … There are people, for example, poets, who just can’t get us straight, because they think we form some sort of a what? A clique or a gang or something. And that there was a poetics? Boy, there was no poetics. It was Charlie Parker. Literally, it was Charlie Parker.

Donald Allen’s anthology The New American Poetry 1945–1960 includes Olson, Duncan, Creeley, Denise Levertov, Paul Blackburn, Paul Carroll, Larry Eigner, Edward Dorn, Jonathan Williams, and Joel Oppenheimer under the Black Mountain banner. Allen makes this selection based on these poets’ publication in two important little magazines of the fifties, Origin (edited by Cid Corman) and The Black Mountain Review (edited by Creeley from 1954 to 1957). Two small presses—Creeley’s Divers Press in Mallorca and Williams’s Jargon Press, founded in 1951 just before he arrived at Black Mountain—published early works by many of these writers.

Critics and editors have also argued that the Black Mountain poets can be understood in relation to Olson’s “projective verse” essay from 1950, in which he argues for a breath-metered poetry that breaks free from “that verse which print bred.” Yet, just as he rejected the idea of Black Mountain poetry, Olson diminished the importance of his 1950 essay. Much of his work is concerned with the visual elements of poetry on the page as well as with sound projected on the breath. Susan Howe, one of Olson’s poetic inheritors, argues that the “feeling for seeing in a poem, is Olson’s innovation,” and that this vision separates Olson’s epic, The Maximus Poems, from his predecessors Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams and their verse epics, The Cantos and Paterson. Poems can be performative but also plastic and pictorial.

In reference to Black Mountain, Olson once told Creeley, “I need a college to think with.” The intense artistic community shaped Olson’s work and marked him as a distinctly pedagogical poet. Creeley once remarked that his voluminous correspondence with Olson leading up to their first meeting at Black Mountain was “of such energy and calculation that it constituted a practical ‘college’ of stimulus and information.” The profound creative and personal relationship between Olson and Creeley, both teachers at the college, is one window into the poetry and poetics associated with Black Mountain. Yet the story goes much deeper. As Olson says, it was “Charlie Parker”; it was improvised, open-ended, subject to chance and change.

What is all too obvious is that Allen’s grouping of Black Mountain poets leaves out a number of writers who have more to do with Black Mountain than some of those who appear in The New American Poetry. Olson, Creeley, and Duncan taught at Black Mountain, and Dorn, Oppenheimer, and Jonathan Williams were students there. Levertov and Blackburn never set foot in Black Mountain, while students like John Wieners and poet-teachers like Mary Caroline Richards and Hilda Morley are left out of Allen’s book and many other important anthologies of U.S. poetry. Olson rejected the idea of a common Black Mountain poetics, but if we look to the actual facts of the college—the teaching, learning, and experimentation that went on there, and the extraordinary artists on its grounds and in its orbit—we find certain elements of process, form, and content that reveal shared aims in their work.

The college’s founder John Andrew Rice envisioned an institution that would take the “progressive” model as professed by John Dewey and push it further toward a new vision of education within democracy. It was not an art school. Rather, in line with Dewey’s thinking, the college’s goal was to provide a well-rounded curriculum that placed the arts at its center. Rice is quoted in a 1936 article on Black Mountain, published in Harper’s Monthly,

Here our central and consistent effort is to teach method, not content, to emphasize process, not results; to invite the student to the realization that the way of handling facts and him amid the facts is more important than the facts themselves …

There is a technic [sic] to be learned, a grammar of the art of living and working in the world. Logic, as severe as it can be, must be learned; if for no other reason, to know its limitations. Dialectic must be learned: and no feelings spared, for you can’t be nice when truth is at stake … Man’s responses to ideas and things in the past must be learned. We must realize that the world as it is isn’t worth saving; it must be made over. These are the pencil, the brush, the chisel.

Though the founding principles laid out by Rice in the thirties rarely come into discussion of the Black Mountain Poets, I can think of no better statement to unify the group of writers later associated with the college. Another founder, Theodore “Ted” Dreier, writes, “Black Mountain has stood for a non-political radicalism in higher education which, like all true radicalism, sought to find modern means for getting back to fundamentals.”

Black Mountain was not, however, isolated from the political realities of its time. From the beginning, the college’s progressive experiment was shaped by a group of European émigrés fleeing authoritarian regimes. Principal among these figures were Josef Albers, the German painter and former master in the Bauhaus, and his wife, Anni Albers, the weaver and teacher. Anni was Josef’s student in the Bauhaus, and they came to America together after the Nazis forced closure of the German art school.

Beginning in 1933, over sixteen years Josef and Anni were central to life at Black Mountain. Josef Albers’s modified Bauhaus curriculum became the high standard for teaching at the college. His goal as a teacher, he said, was “to open eyes.” This was the focus of education at Black Mountain: finding new perspectives, new ways of seeing and thinking about the world. These means were aesthetic, pedagogical, and—yes—political.

Josef Albers’s teaching later influenced poets at Black Mountain. As Duncan says of his own classes at the college,

I just had what would be anybody’s idea of what Albers must have been doing. You knew that [Albers’s students] had color theory, and that they did a workshop sort of approach, and that they didn’t aim at a finished painting … I thought “Well, that’s absolutely right” … I think we had five weeks of vowels … and syllables … Numbers enter into poetry as they do in all time things, measurements. But … [with] Albers … it’s not only the color, but it’s the interrelationships of space and numbers.

Interactions and relationships were part of the shared artistic concerns at Black Mountain, but they were also simple facts of life in the community. Beside the Black Mountain poets, one thinks of the incredible list of artists who spent time living, teaching, and studying at the college: Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, Franz Kline, Ruth Asawa, Cy Twombly, Dorothea Rockburne, Elizabeth Jennerjahn, Pete Jennerjahn, Robert Rauschenberg, Kenneth Noland, Ray Johnson, Arthur Penn, Hazel Larsen Archer, Jacob Lawrence, Gwendolyn Knight, Merce Cunningham, Katherine Litz, John Cage, David Tudor, Lou Harrison, Stefan Wolpe—the list goes on.

On the grounds of Black Mountain College, relationships between these artists created new works. For instance, Creeley collaborated with painter Dan Rice on the book All That Is Lovely in Men, which includes some of Creeley’s finest early work. Creeley and Rice lived together at the college and shared a deep love of jazz, an interest that shaped the rhythms and stuttering syntax characteristic of Creeley’s lyric poems.

Olson participated in a “glyph exchange” with artist Ben Shahn and dancer-choreographer Katherine Litz, and he even attended some of Merce Cunningham’s dance classes. William Carlos Williams, Albert Einstein, and John Dewey were all included in a list of the college’s advisers. This gives a sense of how vibrant the artistic, intellectual, and social interactions at Black Mountain really were. It inspired focused attention and groundbreaking work, while—like any small, tightly knit community—it bred resentments and schisms that ultimately led to its end.

Many of the well-known figures at Black Mountain wrote poems, and when we look at the life of the college from 1933 to 1956, we see a much wider view of what might be considered Black Mountain poetry. Josef Albers is the heart of Black Mountain pedagogy, and he served as a link between the Bauhaus and Black Mountain, extending those schools’ influence in U.S. higher education through his later connections to Harvard and Yale. Like most of his artworks, Albers’s poems are simple, direct, and economical.

John Cage taught at the college for short periods in the spring and summer of 1948 and summers of 1952 and 1953, and he made a profound impact on the community alongside his collaborator Merce Cunningham. Cage’s Theater Piece No. 1 (known as the first “happening”) is one of the most famous events in Black Mountain’s history and mythology. The improvised event included Olson and Richards reading poems, with contributions from Cunningham, Rauschenberg, and Tudor, among others. Cage’s largely chance-derived writing, much of which he wrote to be performed as lecture-poetry, expands the space-time experiments of his musical compositions.

Paul Goodman also taught briefly at Black Mountain. A fine poet, he authored seminal prose works of the era, including Growing Up Absurd, Communitas, and Gestalt Therapy. Goodman’s work gives us a view into the profound shifts in society taking place in the United States in the forties and fifties. Black Mountain played a part in this shifting cultural landscape, and its instigations—like Goodman’s writing—paved the way for counterculture movements of the sixties.

Both M. C. Richards and Hilda Morley have been neglected for far too long. Richards was one of the most beloved teachers at Black Mountain. In 1948, she founded the Black Mountain Press and she published the first edition of The Black Mountain Review (though it is possible that Olson and Creeley knew nothing of this earlier venture when they published their magazine in 1954). The Black Mountain student Fielding Dawson writes, “We must rid our minds of the famous names that have come to identify the school. A fresh approach to comprehend and define Black Mountain, would be to place M. C. at narrative center, and define Black Mountain through her. She as much as anyone, far more than most, assumed its identity, absorbed it, no matter where she was.” Dawson places Richards in direct contrast to Olson as a potential center of Black Mountain poetry, art, and education. After leaving Black Mountain in 1954, Richards joined Cage, Cunningham, and Tudor in Paul Williams’s Stony Point community in Rockland County, New York. Olson later referred to Stony Point as a “continuing limb” of Black Mountain College.

Morley taught poetry at BMC, with a special interest in the Metaphysical poets. In 1952, she married Stefan Wolpe, the German composer who taught music at Black Mountain, and whom Olson refers to in the opening lines of “The Death of Europe.” Wolpe suffered from Parkinson’s disease for almost a decade before his death in 1972, and Morley wrote a beautiful book of elegies for him, What Are Winds & What Are Waters. Morley’s work shows a deep and abiding interest in contemporary painters, as we see in her poem “The Eye Opened.” In “For Creeley,” she gives an indelible portrait of the young poet upon his arrival at Black Mountain. Creeley himself contrasts Morley’s work with “the characteristic male proscriptions one had thought to learn and attend.” He continues in a foreword to her selected poems, The Turning, “I wonder at the way you taught yourself then to move with such lightness and particularity, touching each term and thing, each feeling, always making them actual—like Denise saying (quoting Jung), ‘Everything that acts is actual.’ You made remarkable sense of it.”

If the term “Black Mountain” stands for anything, it is a relentless searching—constant experimentation with form and process to find what is at the root. As Olson writes in “Maximus, to Himself”: “I have had to learn the simplest thing / last.” In different ways, the work of the Black Mountain poets seeks modern means for getting back to fundamentals. The power of their poems exists in a ceaseless inward searching and outward projection of simple human truths through the activity of poetry—poems as the measure of a life.

Jonathan C. Creasy is an author, musician, editor, publisher, and educator based in Dublin, Ireland.

From Black Mountain Poems: An Anthology , edited by Jonathan C. Creasy. © New Directions.

On Desolation: Vija Celmins’s Gray

John Vincler’s column Brush Strokes examines what is it that we can find in paintings in our increasingly digital world.

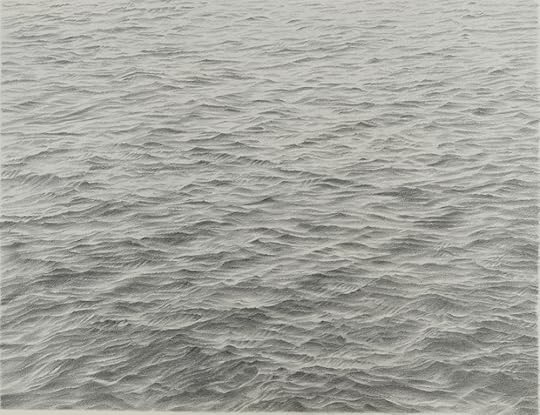

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Ocean), 1973. Collection of Aaron I. Fleischman © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

Open sea water seen from above. Star-filled skies. Stones. Gray after gray: from the graphite of pencils, charcoal on paper and its erasure, oil paint in layer after layer of deep, smooth near-black. Forays into ochre and midnight blues, the earthen tones of sand and stone, then returning seemingly always to gray. Before seeing the objects, works on paper, and paintings gathered together at the Met Breuer for the immense Vija Celmins’s retrospective, “To Fix the Image in Memory,” I had previously witnessed the gnostic perfection of the later paintings of ocean waves and night skies. The Breuer exhibition was the first time I was able to trace in person the artist’s development from the early paintings of objects and appliances in her studio (a hot plate, a fan, a lamp) to her distinctive late work. What I didn’t anticipate from this exhibition was the suggestion of utter desolation.

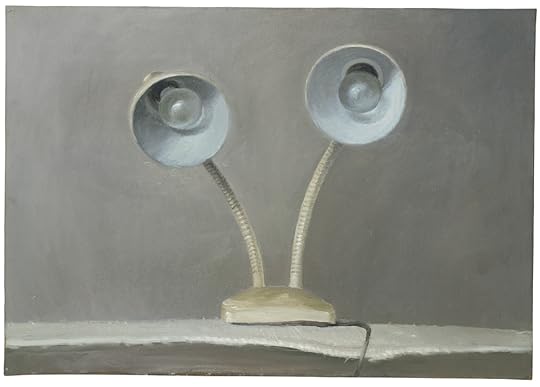

I should say that Vija Celmins paintings are not about this sense of foreboding. The artist has said, “I am not interested in telling stories.” And yet art exhibitions, career retrospectives in particular, do engage in storytelling. What is an exhibition but an essay written with objects in three dimensional space? Celmins’s biography and the sequence and development of her work proceed in an ordered and coherent fashion across two floors of the Breuer. Vija Celmins was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1938, two years before the Soviet occupation. A decade after her birth, her family moved to the United States where they settled in Indiana. Clemens drew animals in her notebook in the back of the classroom while the teacher spoke in a still-unfamiliar foreign language, English. After earning her B.F.A. in Indiana, she headed to California as an art student in the M.F.A. program at University of California, Los Angeles, where she would find a studio near the beach outside of downtown Venice. Here the studio interior itself became her object of study, particularly the functional objects within it. The resulting paintings read more like portraits of inanimate objects than still lives. A lamp stares back at the viewer with its two bulbs, the orange coils of the heater and hot plate in two separate paintings glow with an almost palpable animal heat from their gray perches on the floor and a shelf respectively.

Vija Celmins, (American, b. 1938, Riga, Latvia) Lamp #1, 1964. Collection of the artist, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Photo: Sarah Wells

Celmins was an LA artist before that was fashionable and once it was fashionable her work never read as very LA (again, all that gray). She is either detached from the New York art world, or in dialogue with it from what seems like a vast distance away, with the message changed beyond recognition along the way. In the sixties, she moved away from painting into making sculptures of oversize objects—a hyper-realistic pencil, scaled to the length of a person; oversize erasers—which relate conceptually to pop art but are of a strikingly different character. Celmins’s sculptures remain inward-looking, a new avenue for obsessively documenting the tools and objects found in the studio and used by the artist. They also foreshadow a move, gradual at first, toward meticulous drawings made with pencil on paper prepared with an acrylic ground. For a time, magazine clippings provided her subjects: warplanes, an explosion at sea, a floating zeppelin, and, in 1968, her first moonscape. An early drawing of the open sea, sourced from her own photograph, was also completed in 1968. (There are striking affinities between Celmins and Gerhard Richter’s work from this period, although they were not aware of one another.) By the seventies, she had all but abandoned painting for works made with pencil (without the use of an eraser). The narrative, as it is spun, both in the exhibition itself and in the many reviews, leads us to the arrival of Celmins’s almost transcendental subjects: mostly the open seas and starry skies, but also spider webs, desert floors, clouds, and, again, the surface of the moon. Instead of objects, in this late work she paints or draws expanses.

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Double Desert), 1974. Collection of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

Vija Celmins paintings and drawings feel at once mystical and philosophical. Through all of their insistent gray, they hum with an inherent melancholy, that somehow doesn’t deaden their sense of life and activity. Her works are wondrous and vibrant while also paradoxically stilled (the undulating surface of the sea stopped in a moment) and delimited (the expanse of space contained in a small rectangle)—alive, yet rarely enlivened by anything as distracting as color. Mystical because they often conjure the unknown. Her great subject might be the abyss, depicted through the known and recognizable: the sea, outer space. Philosophical because Celmins returns to first principles. A return to painting as representation, or more than this, art that reassembles truth. The title of the exhibition, “To Fix the Image in Memory,” takes its name from a sort of artistic-philosophical game she played, a game that brought her back to painting by the end of the seventies, before her move to New York in the eighties. Celmins collected stones from the beach or desert, took them home, and then made bronze casts of them. Each individual cast was then painted as a twin facsimile of an original, both were then set before a viewer to see if any difference could be discerned between, in her words, one “found” and one “invented.” Celmins’s work is not simply about obtaining a likeness. It is about seeing and process and working the materials so as to render something that is not only an object of artistic labor, but the result of great and, ultimately, mysterious contemplation.

Vija Celmins, To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI, 1977–82. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Edward R. Broida in honor of David and Renee McKee © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

In an interview, she describes her process of composing the star-field paintings. Of painting and then sanding the surface smooth again and then repainting, repeating this process as many as a dozen times. Is this layered yet anonymous quality (there are no discernible brush strokes), what gives the images their depth and presence? In an almost offhand comment she describes these as “a lame attempt to make something that can remain … like the end of art history, and this my answer to it.” “Lame” perhaps because she recognizes that the work is doomed, as every made thing is doomed. Whatever their fate, while they remain, these works should be treasured, shown, seen, and contemplated.

*

We of course bring our own stories to the art we see. In the weeks before seeing the Celmins show at the Met Breuer it seemed every conversation I had included quips about climate change, the discomfort bubbling to the surface for everyone. “If there is a future, when we’re old,” someone I met for the first time said, as I was holding my child. “Sailing will be a useful skill, after farming, in the decades ahead,” said a friend about to head to Iceland to write about climate change, uncertain if she’d return to New York. I read that the Upper Peninsula in Michigan, where I just spent a few weeks, may be one of the best-suited geographic sites for surviving a climate crisis in the contiguous United States. This relates to the futurity I sensed in Celmins’s work, which I failed to see when I saw her recent paintings at Matthew Marks Gallery in 2017. It occurred to me that Vija Celmins could be described as a painter of geological time. That much of her later subject matter consists of what will remain when and if human beings are no longer: the sea, the solar system, rock and sand, stones and sky. Will clouds remain? Spider webs? These are the questions her work has left me asking as I encounter it in 2019.

Vija Celmins, Falling Star, 2016. Private collection © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Photo: Ron Amstutz courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Celmins’s paintings and drawings made me think anew about of one of my favorite novels, David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. The central and sole character, Kate, appears to be the last living person on earth after some unnamed cataclysmic event. She occupies a house on the beach, or rather a series of them, when she is not spending her winters living in the world’s great museums (the Metropolitan Museum and the Louvre, among others), where “she burned artifacts and certain other objects” for warmth. Once, after leaving her cooking to urinate on the beach, she turned back to see that the house was burning. So, after watching her house become consumed by fire, she simply moved on to another. But she would still see the other house sometimes on her walks down the beach. “One is still prone to think of a house as a house, however, even if there is not remarkably much left of it.” After leaving Celmins’s exhibition, I thought to myself that in one of those otherwise emptied out museums, Celmins’s work would seem almost singularly prescient. Yes, like an answer to the end of art history. Painting for the Anthropocene. Nature painting wholly divorced from romance. But maybe this is too much. I look at the news. Multiple wild fires are burning across California with names like Kincadefire, Tickfire, Skyfire, and Gettyfire. Hundreds of thousands evacuated from their homes. Nearly a million people without power. Prisoners conscripted as firefighters. The Getty Museum campus, with its store of invaluable art objects, is in its namesake fire’s path, protected only by fire retardant dropped from airplanes and its own fire-resistant design. What might we discern of our future in Vija Celmins’s ashen yet beatific grays? What will remain after everything burns?

To Fix The Image in Memory will be on view at the Met Breuer in New York City until January 12.

Read earlier installments of Brush Strokes here

John Vincler is a writer, visual artist, and has worked for a decade as a rare book librarian. He is editor for visual culture at Music & Literature and is at work on a book-length project on cloth as subject and medium in art.

November 25, 2019

The Whole Fucking Paradigm

© paul / Adobe Stock.

“Nigger music,” he said.

He paused and thought deeply for a moment. “Yeah, that’s what we do: full on nigger music. It’s fucking great.”

I wasn’t quite sure what to say so I leaned into the couch and mumbled something like, “That sounds fascinating. I’ve got to come see that sometime.”

San Francisco hipsters filled the corners of the dark apartment. Outside, a light rain came down around the city. Conversations oscillated between fashion and music. I could have talked to so many people but I had chosen this skinny musician who had tried to French kiss me earlier. In that moment, he seemed like a true artist to me—someone who created, revised, destroyed, and rebuilt in an effort to understand the world. And, he played nigger music. Was it a travesty or a triumph that this skinny, five-o’clock-shadowed white guy had so comfortably described his band’s style of music to me, a skinny, five-o’clock-shadowed black guy, as none other than “nigger music”? He apparently didn’t know what else to call it. He said that his rock band, Mutilated Mannequins, constructed lyrical diatribes on racism, pairing them with gripping art-rock freak-outs. He was so sincere, calm, and honest. His eyes honed in on me, his confidence unwavering. His philosophies unfolded: “We are doing important shit, man. Rethinking the whole world. The whole fucking paradigm.”

He went on describing his music. After some time his words echoed listlessly like the distant pitter-patter of rain on the windowsill. I thought about punching him in the neck. I was in a state of existential shock. Lifting up from my body I considered that I needed to spend fewer nights like this: twenty-six years old, going to work, making music, barely sleeping, and then going out just to hear someone talk about nigger music. The age-old question lingered: Would it ever be possible for a nonblack person to throw around the word nigger in a nonmalicious sense? Does the weight of such a word truly vary with context or is it a shotgun shell whenever it gets fired into the air? And, damn, sometimes it takes a minute to figure out how they’re shooting. Former NAACP representative Julian Bond said that the second civil rights movement will be harder because the WHITES ONLY signs have been taken down. Yet their shadows remain firmly placed to doorways and water fountains. How do you challenge a ghost when you can’t even touch it?

*

I visited the University of Virginia when I was nineteen. I was a freshman studying at Princeton but I joined some friends for a road trip. The campus stood as a memorial to Thomas Jefferson—political leader, slave owner, and sexual violator. I stumbled down fraternity row, drunk and foggy, beneath a warm blanket of Gentleman Jack Daniel’s. I had chased down the whiskey with half a case of Natural Light. Then I had lost my friends at the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity house. That was the place where they tossed couches from the second-floor balcony when they get bored.

I had spent the day tracking down friends from D.C. In high school, our class was so small that there wasn’t much room for segregation. White kids and kids of color spent a lot of time together—we were mostly all friends. Yet, just several months removed from that privileged prep school experience I found that all of my friends had splintered into different circles in Charlottesville. If they did not see each other because of their different academic and social interests, I could understand that, but the realization that white and black people did not congregate socially at such a distinguished school shocked me. I had been fast asleep and suddenly I was awake. As I grew older and more explicitly understood the context in which the University of Virginia had been conceived, it was my early-college naïveté that would prove more shocking. It is a school and community that pays homage to a remarkable, elite, and intelligent hero, Thomas Jefferson, who, in the midst of his accomplishments, embraced the ownership—and sexual predation—of slaves toward his own benefit. The system, from its inception, was complex and cracked.

As the evening descended, I conspired to find my college friends who I had parted from earlier. In an age before cell phones, I asked a group of white-shirt, dark-tie frat boys sitting on the steps of another fraternity if they had seen about four or five guys in Princeton T-shirts walking by.

One of them stepped forward, stars and bars glistening behind his eyes, and pointed in a direction that I had no intention of following. He said, “A bunch of black guys came by here ten minutes ago. They went that way.”

He might have been helpful had I specifically inquired about black friends, but I hadn’t and his assumptions bred something foul in my stomach. He had used the golden sword of twenty-first century racists. He had called me a nigger without even using the word. The invisible noun: it just needs to be insinuated—a subtle threat of a bomb that could go off at any moment. I waved my hand at him, pushing away his advice, a dismissal of what he had to offer. I could have taken them on. I could have traded in bloody teeth for intangible pride. I could have found out if they have WHITES ONLY signs in Valhalla.

*

Wait, do you remember the first time you put that record on? Maybe it was a CD or a tape. My roommate had picked up the LP from a San Francisco street vendor for ninety-nine cents: Elvis Costello’s 1978 album This Year’s Model. That picture on the front is priceless: Elvis bent over a camera, taking a picture of you, turning the listener into his model. The album’s third track, “The Beat,” captures the essence of new wave music as well as Blondie, the Cars, and Talking Heads had done in entire albums. I used to spin “The Beat” and other songs off This Year’s Model at late-night house parties just when the makeshift dance floor of someone’s apartment needed one more momentous lift. That song, no, that whole album, was always reliable. I even owned the CD, the expanded edition with all of the demos and b-sides.

One day a friend told me the old story about Elvis Costello calling Ray Charles a “blind, ignorant nigger” during a drunken argument with Bonnie Bramlett and Stephen Stills in a Columbus, Ohio, bar in 1979. When I heard the story, my blood froze up like Arctic pistons. I stopped listening to Costello immediately. Listening to his music would have felt like a betrayal to my identity, my people. I leafed through numerous articles on the internet detailing Costello’s frequent attempts to reckon with and apologize for the incident. Costello, whose actions have often put him on the side of peace, social justice, and equality, has witnessed the weight of his words follow him into his golden years—as recently as 2015 he discussed and apologized for his drunken, youthful missteps in an interview with ?uestlove. Even though I wouldn’t listen to him, I couldn’t bring myself to throw out his albums. I was caught somewhere between my love for the music and a mistake that I couldn’t forgive. This Year’s Model remains tucked away on my long shelf of vinyl.

Mick Jagger famously referred to black women as “brown sugar” in a song of the same name, then managed to squeeze out a phrase about “ten little niggers sittin’ on da wall” in “Sweet Black Angel”—confusingly in a song about civil rights activist Angela Davis—and came full-circle with the revelation that “black girls just wanna get fucked all night long” on 1978’s “Some Girls,” a song that disparaged women of all backgrounds.

Nevertheless, there was a period when I listened to the Stones all of the time and something about it killed me. Why should Costello get the sanction while the Stones have access to my stereo? Maybe their oft-professed debt to black musicians excuses their racial errs. Wait, Costello loves black American music. Perhaps it’s the fact that they have been roundly sexist, racist, and offensive to practically everyone on Earth. But Costello appears to be one of the nicest people in the music industry. It certainly must be their combination of irresistible hooks, intriguing decadence, and unapologetic rock ’n’ roll clichés that make them the bad guys that I hate to love. Isn’t “Alison” one of the catchiest pieces of pop ever written?

*

Rap artists Mobb Deep’s second album, The Infamous, is one of the best albums of the last century. It offers a gritty portrayal of New York life, possessing a distinct literary honesty akin to Lou Reed’s impressions of the city through his solo work and albums with the Velvet Underground. If I dared to count the number of times they throw out the N-word on that album, I would find myself needing a secretary. But why would I count? Their N-bombs and tales of urban violence don’t bother me when I’m listening to the music. Even though they had art-school backgrounds, their drug-lord sound is so convincing that it doesn’t matter. When I think about Mobb Deep and their Infamous album, and really, any number of rap albums can serve as the control here, my reasonable side tells me that I should be bothered by their loose use of nigger—trap talk and misogyny aside. But it sounds so good. I catch myself in the car or listening to music on my phone, rattling off lines like, “This nigga that I’m beginning to dislike, he got me fed / If he doesn’t discontinue his bullshit, he might be dead,” as if they were my own.

Rap producer Dr. Dre makes records that millions of people can dance and bob their heads to. He’s been doing it for years through the voices of a variety of rappers: Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Kendrick Lamar. He is a legend. Yet he was also a member of a band called N.W.A—Niggaz with Attitudes—and produced an album called Niggaz4Life. Does he feel at this point in his career, when he can roll up to the Grammy Awards looking dapper and decidedly un-gangsta, that he is a nigger for life? This is the man who cofounded Beats Audio, a company purchased by Apple for several billion dollars. Or does no amount of corporate wealth and industry success protect a luminary even like Dr. Dre?

Perhaps in the entertainment world it doesn’t matter what you call yourself as long as you manufacture hits for the executives. Good reviews from the critics are a plus, but only optional. And if to Dr. Dre and others, the “nigga4life” lifestyle means casual sex, getting high, and flaunting money, then perhaps it can be a black term for rock star; in which case, Keith Richards, Tommy Lee, and Dave Navarro all could have had guest spots on the Niggaz4Life album.

How does the rest of the country consider Dr. Dre? How might a white, rap-listening college graduate working on Capitol Hill feel about a rap icon? Does this white college grad consider the image of the African American portrayed in hip-hop when considering larger racial issues? Or does he even care to mix his art with politics and ethics? Maybe after all it’s just music and the ethos of rock ’n’ roll filtered through the African American experience comes out in such a way that niggers are homies are bros are pals are dudes are your crew. What are the nationwide effects if everyone, not just black people, buys into this logic? Or is it already selling? Rap music rarely goes multiplatinum without white money. So where are the white listeners—the ones who roll down the street en route to middle class jobs in their trucks shaking the whole block with the bass and rhymes of A$AP Rocky, Rick Ross, and The Game—where are they when it is time to stand in the streets for justice, for the requiems of Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, and the ever-expanding roll call of innocent lives consumed by hate? Where are they when they just need to vote for the right person? To have it both ways, for all of us, is a distinct privilege that we should never invoke.

Andre Perry is an essayist and arts advocate. He received his M.F.A. from the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program, and his work has appeared in The Believer, Catapult, Granta, and other journals. He cofounded Iowa City’s Mission Creek Festival, a celebration of music and literature, as well as the multidisciplinary festival of creative process Witching Hour. He continues to live and work in Iowa City. Some of Us Are Very Hungry Now is his first book.

From Some of Us Are Very Hungry Now , by Andre Perry. Copyright © 2019 by Andre Perry. Reprinted with the permission of Two Dollar Radio.

Feminize Your Canon: Mary Heaton Vorse

Our column Feminize Your Canon explores the lives of underrated and underread female authors. Originally begun by Emma Garman, it will now be written by Joanna Scutts.

Mary Heaton Vorse.

Mary Heaton Vorse, prolific novelist, journalist, and labor activist, spent most of her long life trying to escape her upper-middle-class origins. The heroine of her 1918 novel I’ve Come To Stay calls the inescapability of a bourgeois upbringing life’s “blue serge lining”—a reference to the practical fabric that protected the inside of coats and suits, forming a barrier between the self and the world. The lining stands for the inevitable conformity of class, getting, if not quite under the wearer’s skin, then next to it, holding her upright, constraining her imagination and her freedom. Camilla is constantly on the run from it. She embraces the pretensions of bohemian Greenwich Village—anarchist friends, artistic aspirations, a Polish violinist lover, and nights spent in smoky bars. She repeatedly rejects her neighbor and suitor, the equally middle-class Ambrose Ingraham, out of fear that he will wrap her up in blue serge once again, and strangle her with it. Subtitled A Love Comedy of Bohemia, the novel is more of an archaeological find than a timeless classic. Yet its ironic depiction of young people caught between ambition and gender-based expectation dramatizes the central conflict of its author’s life, and that of her generation of American “New Women.”

Mary Heaton was born rich and rebellious in 1874, and spent most of her childhood in Amherst, Massachusetts, a place that was, by contrast, rural and religious. She was close to her bookish father and idolized her distant mother, Ellen, who paid more attention to her five older children from her first marriage. Mary watched her intelligent, energetic mother struggle to fill her days with meaningful activity. Other women of her era and class threw themselves into social reform and the fight for women’s suffrage, but Ellen believed too many people already had the vote, and that a woman’s place was in the home. This did not preclude plenty of European travel and culture to burnish her daughters’ marriage prospects, and Mary had a rich, if haphazard education, bolstered by voracious private reading. Although she belonged to a generation of women who were breaking down the doors to academia and the professions, she had no interest in submitting to the rules of a women’s college. She longed for a greater freedom, and begged to go to Paris to study art.

Her mother insisted on coming with her, somewhat curtailing the nineteen-year-old’s freedom to indulge in the temptations of the Left Bank, but Mary managed her first serious romance there with a domineering fellow art student. Although she didn’t consider herself especially beautiful—photographs show a thin woman with a strong straight nose, wide mouth, and pouched, intelligent eyes—Mary nevertheless exuded confidence, and rarely had trouble attracting men. Her lover praised her intelligence and independence, yet undermined it by constantly pointing out her social and physical limitations as a woman. It was a dynamic that would mark Mary’s subsequent relationships, and come to life over and over again in her fiction: the young heroine enthralled by male strength, but chafing against male dominance.

Back in America, Mary convinced her parents to let her go to New York to continue her art studies, adopting the persona of the “Bachelor Girl.” This mid-1890’s phenomenon, a more rebellious version of the already mythologized “New Woman,” was discussed with an eager censoriousness, while the girls themselves enjoyed a brief respite from family obligations. “I am part of the avant-garde. I have overstepped the bounds!” Mary wrote exultantly. Having realized rather late that she could not paint, she attached herself to the male-dominated literary scene that was drinking and pontificating in downtown cafes in the late 1890’s. In 1898, she met and secretly married Albert White Vorse, the Harvard-educated son of a Massachusetts minister trying as earnestly as she was to reinvent himself as a bohemian. Mary’s biographer quotes Bert’s delight at discovering that, despite her Paris sojourn, he had been the one to take her virginity (after noting how she “hesitated” and he “pushed” her). Their letters make clear Mary’s deeply conflicted desires for marriage and independence.

Although she published her first short story in a local newspaper at the age of sixteen, and was now regularly publishing book reviews, Mary (and Bert) insisted that her writing was merely something to fill her time. But before long it became obvious that she was the talent and the breadwinner in the house. Perhaps they might have navigated this uneven division of labor, but then there was a baby, and then there was Bert’s cheating. In the first of many attempts at a fresh start, the couple decamped for France in 1903, where Mary started writing fiction. “I reel off stuff like a regular phonograph,” she wrote—painfully aware that Bert, at the same time, was a stuck record. In her midthirties, Mary’s literary star rose as her marriage crumbled. In 1924, she wrote an essay, “Why I Have Failed As A Mother,” that articulated the impossible struggle between motherhood and work. She admits that the fault lies not just in the obligation to earn money, though she certainly felt that. No, her real failure, as she saw it, was the very thing that was supposed to undergird male success: “I grew ambitious.” She writes that she dreaded leaving her desk to face her children and their needs: “They seem to me like a nestful of birds, their yellow beaks forever agape for me to fill.” Yet her intense love for them, detailed in story after story, was as much of a drive as the work.

Between 1906 and 1911 Vorse sold story after story about domestic relationships and family life—popular fiction that was lucrative enough to support her family. Her fiction was aimed at a middle-class female audience, but it resonated with men trying to figure out their roles in a changing society. The marital ideal was shifting away from the traditional dynamic of dominance and submission, toward a union of friendly equals. Yet gender roles, deeply ingrained, could not be shaken loose as easily as that. Her novels from this period—The Breaking-In of a Yachtsman’s Wife, Autobiography of an Elderly Woman, The Heart’s Country—often blame men for failing to understand women, but she also criticizes women for embracing their own subservience, whether to husbands or children. Mothers who sacrifice their own needs for their families—as dramatized in her 1907 story “The Quiet Woman”—end up breeding “beautiful soulless monstrosities,” as selfish and tyrannical as their mothers were selfless. Yet Vorse also paid a rare degree of attention to parental love. Her 1911 novel The Very Little Person brings to life a father’s bewildered affection for his infant daughter, emphasizing how absurdly little middle-class men were expected to know about children and about women’s maternal experiences. A subtle rivalry and distance lingers between the parents, John and Constance. When his wife reports on their daughter’s first smile, John feels “secretly hurt that the baby hadn’t smiled at him, and to hide this feeling, pretended a disbelief.” The book’s ending hovers in that gap between them, with John triumphant that his daughter has said her first word, and thus “she isn’t a baby any more, she is a grown-up little girl.” He is utterly oblivious to the heartbreak this causes his wife.

The Very Little Person is rooted in close and tender observation of Mary’s own daughter, conceived partly in an effort to save her marriage. Mary had tried to reconcile herself to Bert’s cheating by treating him with the patience of a mother nursing a sick child. (She would scrutinize that “maternal instinct” of women toward adult men in I’ve Come To Stay, six years later.) The marriage was all but over by the time Bert died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage, alone in a hotel on Staten Island in 1910. The next day, Mary’s mother died of heart failure.

It is hardly surprising that the direction of Mary’s life and writing changed after this brutal break with the past. Yet it was the 1912 textile workers’ strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that she would name in her 1934 autobiography as the turning point. For the rest of her life, until her death in 1966 at the age of ninety-two, workers’ battles for fair treatment would be her primary focus. “We knew now where we belonged;” she wrote, “on the side of the workers, and not with the comfortable people among whom we were born.”

The conditions in the mills at Lawrence are still shocking. At the turn of the century, workers, many of them teenagers, scraped by on two or three dollars a week, most of which went to paying their rent in overcrowded districts. Women were subject to routine sexual exploitation by their bosses, and death from accidents or lung diseases were everyday occurrences. Thirty-six out of every hundred men and women who worked the mills died before the age of twenty-five. In early 1912, the state attempted to enforce a law cutting the hours of the women and those under eighteen in the mills to fifty-four hours a week. In response, the mill owners cut everyone’s hours and their salaries, and were accused of speeding up output.

Vorse’s report on the “The Trouble at Lawrence,” ran in Harper’s, where she was one of the few left-leaning writers the magazine would publish. (She also wrote for liberal publications like The Nation and The New Republic, and was a contributor and editor at the Greenwich Village socialist monthly The Masses.) Her piece opened with a focus on a group of workers’ children, who had been prevented by local authorities from leaving Lawrence to stay with relatives in other cities—a relief effort spearheaded by Margaret Sanger. The “forcible detention” of children was the rare event, Vorse wrote, that Americans all over the country would surely rise up to protest. She went on to describe the killing of a nineteen-year-old Syrian striker by a member of the militia formed by the Lawrence factory owners to put down the strike, and the reaction of his community, noting both the exotic beauty of the women in the Syrian quarter and the presence of posters that had lured immigrants from Damascus with the promise of good jobs. Although the strikers were “of warring nations and warring creeds” (Lawrence’s workforce included at least twenty-five nationalities), Vorse wrote that they had come together spontaneously in protest. The experience opened their eyes to a life, and a world, beyond home and the mill, she said hopefully. “A strike like this makes people think.”

Mary traveled to Lawrence with Joe O’Brien, a reporter she’d met the year before, and they married three months later. He was a gregarious, joyful partner who loved family life, and they soon had a son together to join Mary’s two older children. She continued to write “lollypops”—her lucrative women’s stories—and to spend summers at her home in Provincetown, an anchor for her throughout her life, and began to turn it into the summer “colony” of their Greenwich Village friends. In 1915, those friends staged the first performances of the avant-garde theater group they called the Provincetown Players, performing each other’s daring, satirical, self-consciously modern plays. Sinclair Lewis passed through, and later credited Mary with teaching him “the three Rs—Realism, Roughness, and Right-Thinking.” But through this social and energetic time, O’Brien was plagued with an illness that turned out to be stomach cancer. Mary was widowed again after just five years of marriage. During her subsequent relationship with the political cartoonist Robert Minor, she suffered a devastating second-trimester miscarriage, and spent several years afterward addicted to the morphine she was given for the pain.

Yet she continued to write and travel to protests and war zones, always with a focus on the human story. Through her friendships with labor activists and her reporting, she was especially aware of the intersecting challenges of being female and working class. She was also the rare journalist who actively participated in strikes and worked with unions, enabling her to bring an insider perspective to readers. During World War II, she was perhaps the oldest American foreign correspondent—seventy-one when the war ended—and politically active up until her death.

In addition to her novels and journalism, Vorse published two volumes of humorous, sharp-eyed memoir, A Footnote to Folly in 1935, and Time and the Town, in 1942, a “chronicle” of her beloved home in Provincetown, where she lived on and off for thirty-six years. Her fiction hints at the compromises and costs of rebellion for middle-class women of her era, but her autobiographical writing lays bare what it really meant to break out and blaze her own trail. Vorse wrote for the world in which she lived, with an immediacy that cares little for posterity. To read her now feels as disorienting as time travel, plunging us into a world that resembles ours but for which we’re lacking crucial maps and signposts. Nevertheless, some values hold strong. Throughout her long flight from that stifling Amherst mansion, Mary Heaton Vorse cherished freedom and the people who would fight for it, a value that to her was not an abstraction but a deeply human impulse.

Joanna Scutts is a cultural historian and critic, and the author of The Extra Woman: How Marjorie Hillis Led a Generation of Women to Live Alone and Like It.

The Lost & Found Archives

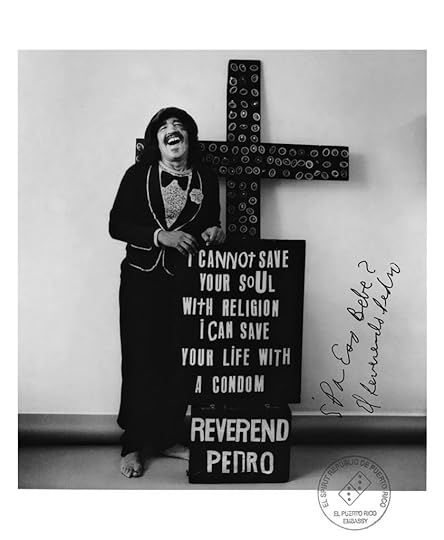

Rev. Pedro Pietri, ADÁL, 1990

On an unremarkable street corner in East Harlem, diagonal from a big gray battleship of new housing development, sits the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, which everyone calls the Centro. This fall, I went to the Centro to meet Rojo Robles, a student in the Latin American, Iberian, and Latino cultures department at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, who had offered to show me the library where the archives are kept. We paused in a fluorescent-lit hallway to observe photos of leaders from the Puerto Rican diaspora, many of whose works are preserved at the Centro. Among them, mustache drooping over a smile, was Pedro Pietri, cofounder and poet laureate of the Nuyorican Movement in downtown Manhattan, who died in 2004—and whom Robles is studying. Together, we were visiting his collection.

These days, most people don’t remember Pietri. Not just a poet but a playwright and early performance artist, he spent the AIDS era hand-packaging his “condom poems”: bits of verse along with prophylactics in tiny manila envelopes, which he distributed during performances at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and other galleries, bars, and public spaces. Both artist and activist, he used his work to make the AIDS crisis visible while also providing protection to a community on the margins. As we reevaluate the horror and official inaction that surrounded the crisis, his actions are of particular interest. But they were ephemeral. The scraps that remain have been tucked away in the archives for decades.

Now, they are being revived. In November, Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative published text and images from the condom poems as part of a new series of chapbooks. For ten years, the poet and scholar Ammiel Alcalay and his graduate students at CUNY’s Center for the Humanities have been trawling the archives of mid-twentieth-century poets like Pietri. Each year, using a printing press in the basement of the Graduate Center, they publish a selection of the strange treasures they find. “A lot of the writers we think we know, seventy or eighty percent of their work is still in the archives,” said Alcalay, a gentle, gray-maned eccentric who uncovers letters, lectures, syllabi, translations, and other marginalia. Without the work of his team, it might all remain buried.

Alcalay envisions his project as a subversive one. As Jacques Derrida noted in his formative 1995 essay “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” the keepers of an archive don’t just guard its physical security: “They have the power to interpret the archives.” Alcalay wants to undermine that power by reinterpreting the canon and the stories that surround it. Had he not uncovered Audre Lorde’s syllabi and classroom notes, we might have forgotten the astonishing fact that she taught race theory to aspiring cops at John Jay College in the seventies. And until his student Rowena Kennedy-Epstein looked, no one knew that the poet Muriel Rukeyser had kept an unpublished novel from 1937, topped with a rejection letter; today, that book is in print. There are dozens more examples.

Pietri is a case in point. Where mainstream American poetry is concerned, he is often “invisibilized,” as Robles puts it. Yet he is an important writer, one who made early entries into conceptual art as a means to advocate publicly for Nuyoricans, queer people, and downtown artists during one of the darkest and deadliest periods in New York City’s history.

*

“I feel like a mime,” Robles said as his white-gloved hands gingerly lifted a piece of sheet metal onto which Pietri had printed the maroon cover of a book called Invisible Poetry. I had thought we might enter a hangar-size storage area, like an FBI evidence warehouse, full of boxes to pick through. But instead we stood at a conference table piled with boxes in a cozy, carpeted room hung with art and photos of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Using an elaborate printed “finding aid,” Robles had preselected artifacts from among Pietri’s eighty-odd boxes of plays, manuscripts, flyers, paintings, photos, vinyl records, and what Robles calls “mutant gadgets,” since some of the works are uncategorizable handmade props.

Robles leafed through a manuscript called “Out of Order,” which Pietri had photocopied and distributed at readings but never published. The source for most of the condom poems, it contains thousands of short works that dissect the disordered and racially unequal New York City of the seventies and eighties. City officials had abandoned black and brown enclaves like Harlem and the Bronx, trash towered on the sidewalks, and heroin and crack ravaged whole neighborhoods. “New york new york / you are your own undertaker,” Pietri wrote. Some of these poems have been collected—City Lights Books published a selection of thirty poems in 2015, and an out-of-print 2001 Italian volume holds about 350 more—but most exist only at the Centro.

Pietri’s works are both morbid and playful. His preoccupation with the AIDS epidemic was a natural outgrowth of a poetics of grand metaphysical decline—his interest in the way we’re all dying all the time, some of us more so than others. “It’s raw,” said Robles of the collection, his dark eyes shining with contained excitement. “It’s sexual. It’s about drugs, it’s about alcohol, it’s about wayward lives, it’s about street life, it’s about difficult feelings, it’s about broken families. It’s about fun, as well.”

The manila packets of Pietri’s condom poems were smaller, and more pleasingly assembled, than I had imagined from a description alone. Some Pietri had hand-painted black with tiny gold insignia. Typewritten onto the back of each packet is a short poem in Spanish, English, or Italian, with warnings like “socializing can be fatal” and “Is no longer safe / to screw Every place,” and encouragements to “Masturbate slowly” instead. Though I looked through dozens, Robles told me there were likely thousands in the world.

Contained within these kinetic poems is Pietri’s attempt to protect his community, which was uniquely vulnerable to AIDS infection. As we spoke, Robles unfurled a banner, with ransom-note letters reading “CONDOMS & POEMS 4-SALE,” that Pietri displayed during readings. It was tattered and coffee-stained in places, and taped to it were handwritten notebook pages. Often, Pietri would improvise performances as the Reverend Pedro, his barefoot-prophet persona, tossing condoms from hand-painted suitcases that bore slogans like “UNDERTAKER POET.” When Robles carefully removed these suitcases from their Bubble Wrap chrysalides, they still smelled sharp, like paint and musty leather.

“The dynamic was always to emphasize the importance of safe sex,” said Robles. “For him, it wasn’t about moralizing. It was about protecting yourself from AIDS and other STDs.” In Robles’s introduction to the Lost & Found volume, he shares a story from Nuyorican poet María Teresa “Mariposa” Fernández, who recounts that she was a twenty-year-old freshman at New York University when she first saw Pietri perform. “He threw condoms at us, something our school administrators should have been doing,” she said. “I thought it was genius.” Filed carefully away in the archives, these artifacts are a monument to creative community action at a time when authorities stood mute in the face of suffering and death. “It’s documentation of a period of Nuyorican history that is, for the most part, erased,” said Robles.

*

The Lost & Found chapbook, Condom Poems 4 Sale One Size Fits All, contains a tight selection of thirty poems—enough to open a window into that little-known moment in history. In a special envelope, Alcalay’s team has reproduced personal photos and hand-painted performance flyers from the archive, including one of the Reverend Pedro laughing, standing barefoot before a “condom cross.”

The Pietri volume is part of the eighth series Lost & Found has published. Other new materials include notes from Diane di Prima’s lectures on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound as a “magical working”; Muriel Rukeyser’s full translation of Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, completed in the early thirties while she was a student and involved in the Scottsboro trial; and the former Dominican nun Mary Norbert Körte’s 1967 response to Ghost Tantras, by Michael McClure.

Much of Alcalay’s output is as niche as this. For years, his academic community saw him as a “wacky poet” tinkering in the recesses of the Graduate Center, he told me. You can see why. His office is cluttered with books and posters and bags of papers; one pities his future executor. “I’m a lunatic,” he told me from behind a sagging pair of tortoiseshell eyeglasses. “I keep everything.”

More recently, though, the project has found a measure of legitimacy. It’s quietly influencing the field and finding its way into classrooms, books, and dissertations. In 2017, the Before Columbus Foundation presented Alcalay its American Book Award. Lost & Found also appears as an example in Jean-Christophe Cloutier’s new book Shadow Archives, which argues for the importance of archival research in historicizing African-American literature. And not long ago, another powerful endorsement reached Alcalay’s ears: shortly before Toni Morrison died, a mutual friend told him that the writer was an admirer of the project’s Toni Cade Bambara volume, “Realizing the Dream of a Black University,” & Other Writings.

Alcalay is fond of saying that Lost & Found is about relationships. By this, he means the unexpected ones among poets that his students uncover. The most obvious examples are in the surprising creative correspondences they publish, like that between Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn, or the odes, like Kathy Acker’s to Leroi Jones. “To me, it’s like fine weaving,” said Alcalay, of revealing these connections. “It’s like weaving this very complex pattern.” Doing so binds familiar figures together within an expanding creative fabric, pleasantly exposing the notion of the great solitary artist as a myth.

*

Pietri, too, was bound to better-known contemporaries, kindred downtown spirits like Baraka, Ishmael Reed, June Jordan, and Ntozake Shange. But the strongest connections that emerge from his archives are those he forged with his public. During his life, he nurtured the language and longings of a fiercely dedicated subculture. His poems abound with street talk, slang, informal conjugations. “That was the aesthetic proposal,” Robles told me. “He was validating Spanglish, he was validating the English that Puerto Ricans were speaking, he was validating Black English.” It was not for the academy, said Robles, it was for the people. It may be part of why he’s often ghettoized as a Latin American poet and overlooked in the canon. But it’s also why he served so aptly as a community advocate and provocateur.

A thrilling part of the new Lost & Found volume is that it extends Pietri’s public provocation. Its afterword, written by Cristina Pérez Díaz, the student who began the Pietri project before Robles took it over, is preserved in untranslated Spanish, like many of Pietri’s archived poems. “If you can’t read it, tough luck,” said Alcalay. “Learn some Spanish.”

After all, the archive—the existence of certain collections and the absence of others—is always a matter of politics. What gets chosen and surfaced depends wholly on who is doing the choosing. We tend to think of it as a rarefied space, the province of scholars and authorities. “The meaning of archive, its only meaning,” wrote Derrida, “comes to it from the Greek arkheion: initially a house, a domicile, an address, the residence of the superior magistrates, the archons, those who commanded.”

But public archives are everywhere, in libraries across the country. Anyone can visit and decide what’s important, as I discovered at the Centro. Think, too, of all the uncommanded archives, in cluttered homes and offices. “Some stuff ends up in dumpsters,” said Alcalay. To his mind, Lost & Found is an invitation to non-scholars to join the process, to become editors and archivists themselves. “It’s creating a consciousness and awareness that these are the materials of our culture, and they’re going to disappear if we’re not vigilant.” He hopes some minor archons will think to rescue these materials—or maybe spirit them his way: “If you don’t take charge of your culture, who will?”

Michael Friedrich is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn who covers culture and social justice. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, The Nation, and The New Republic.

November 22, 2019

Staff Picks: Royals, Rothkos, and Realizations

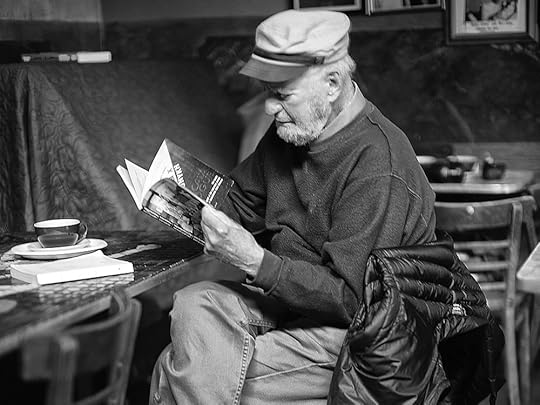

Lawrence Ferlinghetti at Caffe Trieste, 2012. Photo: Christopher Michel (CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/...)). Via Wikimedia Commons.

I have always loved November. I don’t know if that’s because I was born in it or because it’s when fall becomes the cruelest version of itself. The air bites; the final leaves fall to the ground. Either way, the month is tailor-made for nostalgia. At times like these, I often turn to the first poet I ever loved, Lawrence Ferlinghetti. In high school, I memorized “The Pennycandystore beyond the El” and recited it to myself daily, a strange sort of mantra. At the time, I thought myself the girl in the poem, a heaving form full of tragedy and potential. But now, I see I am the cat, strolling among the sweets, unhurried and unbothered. I don’t know if I’ll ever be the man. Or maybe that’s all I’ve ever been, sitting in the “semigloom,” “in love with unreality.” —Noor Qasim

I picked up Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other one evening earlier this week thinking I’d get fifty pages in and save the rest for the weekend. Hours later, I realized it was 1 A.M. and that I needed to force myself to go to bed for work the next morning. Evaristo’s Booker Prize–winning novel is a compulsively readable exploration of the lives of twelve characters in contemporary Britain, the majority of them black and female. Much of the book converges around The Last Amazon of Dahomey, a play by Amma—whose chapter opens the novel—that is set to premiere at the National Theatre. Each chapter takes the voice of a different character, many of them connected to one another through blood or friendship, and as Evaristo moves closer to the premiere of the play, she explores questions of race, gender, sexuality, immigration, and what it means to be British. There’s something truly pleasurable to watching a virtuoso at work, and Evaristo’s ability to switch between voices, between places, and between moods brings to mind an extraordinary conductor and her orchestra. —Rhian Sasseen

Saeed Jones.

“There should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a black boy can lie awake at night,” Saeed Jones writes in his memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives. Jones, an acclaimed poet and journalist with a talent for expressing the ineffable, may be uniquely capable of giving us these words. In this slim book, Jones describes his experience growing up as a queer black boy in Texas and his struggle to carve out space for himself within a family and country that were often hostile. The story is told through a series of cinematic vignettes that trace a course through Jones’s tumultuous young adulthood. In one, we see an adolescent Jones fighting his devoutly Christian grandmother. In another, we see his early forays into sexuality—some tender, some treacherous. Throughout, Jones weaves an unflinching examination of race and sexuality, grappling with a violent national mythology and reflecting on events such as the AIDS crisis and the murder of Matthew Shepard. In all, it is an uncommonly generous book, one that refuses simple explanations. When describing a harrowing scene in which a lover turns violent, for instance, Jones recalls looking up at his attacker, and says, “I didn’t see a gay basher; I saw a man who thought he was fighting for his life.” Jones’s work—which falls naturally into the legacy of Toni Morrison and Roxane Gay—engages with the physical body as a complicated site of experience and identity, capable of both lust and violence, vulnerability and power. Many passages in the book warrant underlining. But one of the most powerful, for me, comes about halfway through the story, when Jones—lying in bed in a stranger’s home—realizes “that my body could be a passport or a key … a brick thrown through a sleeping house’s window.” Jones’s gradual discovery of his own power, both sexual and creative, is one of the book’s most exciting and ultimately moving arcs. —Cornelia Channing