James Clear's Blog, page 8

August 27, 2015

Overrated vs. Underrated: Common Beliefs We Get Wrong

As a society, we often overvalue unimportant things and undervalue the ideas and strategies that make a real difference.

Here’s my take on a few common beliefs that I think we often get wrong.

Overrated: Being busy.

Underrated: Doing one thing at a time.

Being in motion is not the same thing as taking action. As a society, we’ve fallen into a trap of busyness and overwork. More critically, we have mistaken all this activity as an indicator of living an important life. The underlying thought seems to be, “Look how busy I am? If I’m doing all this work, I must be doing something important.” And, by extension, “I must be important because I’m so busy.”

Read more: The Myth of Multitasking: Why Fewer Priorities Leads to Better Work

Overrated: Avoiding criticism.

Underrated: Sharing unique ideas.

You can either be judged because you created something or ignored because you left your greatness inside of you. Too often, we let our fears and emotions prevent us from sharing our work with others.

Read more: Haters and Critics: How to Deal with People Judging You and Your Work

Overrated: Unrestricted freedom.

Underrated: Carefully designed constraints.

Constraints actually increase our skill development rather than restrict it. We need lines to show us where to add color, not a blank canvas to draw on. As an entrepreneur, I struggled to manage myself until I realized that I needed to add some structure to my day. I began to only scheduled calls in the afternoon. I blocked my email inbox until noon. I required myself to publish a new article every Monday and Thursday. By adding a few carefully designed constraints to my life I reduced my freedom, but actually improved my productivity and happiness. Instead of feeling restricted by constraints, I felt empowered.

Read more: The More We Limit Ourselves, the More Resourceful We Become

Overrated: Degrees, certifications, and credentials.

Underrated: Courage and creativity.

Degrees can be important. (I don’t want to be operated on by a neurosurgeon who didn’t attend medical school.) But as my friend Charlie Gilkey told me, “Most people need degrees because they don’t have the courage to ask for what they want.” In many cases, the courage to ask for what you want and a willingness to solve other people’s problems is all you really need. The degrees, the awards, going to the “right” school or being born into the “right” family—none of these things are a prerequisite for success.

Read more: Let Your Values Drive Your Choices

Overrated: Getting motivated.

Underrated: Changing your environment.

We incorrectly believe that motivation is the missing link that will enable us to stick to a new diet plan or write that book or learn a new language. Motivation is fickle and it doesn’t last. One study found that motivation had no impact on whether or not people exercised over a two week period. The effects of motivation essentially vanished after a day. Meanwhile, most of your daily choices are simply a response to the environment around you. We rarely think about the spaces we live and work in, but they drive our behavior whether we feel motivated or not.

Read more: How to Stick With Good Habits Even When Your Willpower is Gone

Overrated: Watching the news.

Underrated: Reading old books.

By default, any good book that is more than 10 years old is filled with life-changing ideas. Why? Because bad books are forgotten after a decade or two. Any lasting book must be filled with ideas that stand the test of time. Meanwhile, the news is filled with fleeting information. We justify paying attention to the media because we think it makes us informed, but being informed is useless when most of the information will be unimportant by tomorrow. The news is just a television show and, like most TV shows, the goal is not to deliver the most accurate version of reality, but the version that keeps you watching. You wouldn’t want to stuff your body with low quality food. Why cram your mind with low quality thoughts?

Read More: Stop Overdosing on Celebrity Gossip, The News, and Low Quality Information

Overrated: Discovering the “new” thing.

Underrated: Mastering the fundamentals.

I’ve been guilty of jumping at the latest tactic or strategy, just like everyone else. We fool ourselves into thinking that a new tactic will change the fact that we need to do the work. There really isn’t much of a secret to most things. Want to be a better writer? Write more. Want to be stronger? Lift more. Want to learn a new language? Speak the language more. The greatest skill in any endeavor is doing the work. You don’t need more time, more money, or better strategies. You just need to do the work.

Read more: Vince Lombardi on the Hidden Power of Mastering the Fundamentals

Overrated: Being the leader.

Underrated: Being a better teammate.

We love status. We want pins and medallions on our jackets. We want power and prestige in our titles. We want to be acknowledge, recognized, and praised. It’s too bad all of those make for hollow leaders. Great teams require great teammates. Nowhere is that more true that at the top. No leader ever became worse by thinking about their teammates more.

Overrated: Winning.

Underrated: Improving.

Too often, we value immediate results over long-term improvement. CFOs play accounting games to meet quarterly earnings projections. Police chiefs fudge the numbers to make crime rates appear lower. Students cheat on exams because getting an A is more important than learning the material. Learning, growth, and improvement are undervalued in the name of getting faster results. The shame of it all is that if we could find the time to focus on the process, the outcomes would follow shortly after.

Read more: Pat Riley on the Remarkable Power of Getting 1% Better

Overrated: Training to failure.

Underrated: Not missing workouts.

Feeling exhausted at the end of your workout is massively overrated. Working until you have nothing left is a recipe for burnout, injury, illness, and inconsistency. It is better to make small progress every day than to do as much as humanly possible in one day. Effort means nothing if it only last for a week or two. Do things you can sustain.

Read more: How to Stay Focused When You Get Bored Working Toward Your Goals

August 24, 2015

The 2015 Tiny Gains Challenge

For the next 20 weeks, I’m going to lead the charge on The Tiny Gains Challenge. Along the way, you’ll learn how to build better health habits, avoid injury, and get leaner and stronger in the easiest way possible.

Let me explain how this is going to work and, more importantly, why this will work.

Tiny Gains Every Week

At the beginning of this year—on January 7th, 2015—I did four sets of five chin-ups. During that first week, I did chin-ups without any additional weight. The second week, however, I strapped on a weight belt and added one pound before doing my chin-up workout. The third week, I added another pound.

I have continued this pattern for the entire year. Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday I will do four sets of five chin-ups. When the next Monday rolls around, I add one more pound and then complete my three workouts that week at the new weight.

I haven’t been perfect, of course. I have repeated the same weight a handful of times because I skipped workouts due to travel, but generally speaking, I have been increasing by one pound every week.

Something Surprising

After a few months passed, I started to realize something strange. I was definitely stronger because I was lifting more weight, but the workouts still felt easy. The weight was steadily climbing week by week, and yet, the difficultly was nearly the same.

Here are three videos of my progress:

On May 18, 2015 I did four sets of five reps with 15 pounds. (video)

On June 29, 2015 I did four sets of five reps with 20 pounds. (video)

On August 10, 2015 I did four sets of five reps with 25 pounds. (video)

If you watch those videos, you’ll notice that each set looks virtually the same. I was setting personal records every week, but the gains were so small that I could actually adapt to them and be ready for another tiny increase the next week. This pattern has now continued for eight months.

Slowly, I began to apply this same concept to other exercises: squats, bench press, overhead press, and more. The same thing happened. Here are videos of me doing 3 sets of 6 reps on bench press at 220 lbs, 225 lbs, 232 lbs, and 238 lbs. Again, each video is a few weeks apart and they all look more or less the same.

These personal experiments are what sparked The Tiny Gains Challenge.

How The Tiny Gains Challenge Works

This challenge is really simple. The basic idea is to start with a weight that is easy for you and increase that weight by a very tiny amount each week so that by the end of the challenge your new “easy weight” is 20 pounds heavier.

There are three steps:

Choose an exercise that you want to improve and start with an easy weight.

Add one pound per week for the next 20 weeks. (Or, 0.5 kg per week.)

If you want, use the hashtag #tinygains to share your progress on Instagram.

At this point you may be wondering a few things. How do I only increase by one pound? How do I know what weight to start with? What if I want to run or do bodyweight exercises instead of lifting weights? I have answers to these questions and more in the Frequently Asked Question at the bottom of this article.

Next Steps

The Tiny Gains Challenge starts this week. I’ll be in the gym today to kick off the first day of the challenge, but you’re welcome to start anytime this week.

This is a personal challenge, not a competition. The goal is for everyone to make consistent progress and build better fitness habits. That said, if you’re interested in following along with my progress I’ll be updating my Instagram weightlifting account each week. I’ll be experimenting right along side you.

Overall, the challenge will run for the next 20 weeks (basically until the end of the year). When 2016 gets here, you’re going to be 20 pounds stronger.

Making progress in the gym doesn’t have to be complicated. One pound per week for the next 20 weeks. Let’s do this. #tinygains

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are my answers to some common questions you may have about The Tiny Gains Challenge.

“How do I increase by just one pound?” The smallest plates at most gyms are 2.5 lbs (about 1 kg), so if you want to increase by just one pound like I do, then you need to use fractional plates. Most people have never heard of fractional plates, which are small plates that let you add tiny amounts of weight to the bar—the smallest ones are 1/4 pound. My gym happens to have fractional plates, but if your gym does not, then you can buy a decent set of fractional plates and toss them in your gym bag since they don’t weigh very much.

“What weight should I start with?” You should start with a weight that you can do relatively easily and with good form. Your reps should be crisp, smooth, and fast. When in doubt, start with a weight that feels too easy. If you actually show up each week and add one pound, then the weight will get heavy soon enough. Each time I have done this, I have started with a weight that was 70 percent of my one-rep max. So, if the most I could squat was 100 pounds for one rep, then I would start with 70 pounds.

How many repetitions should I do for each set? I use Prilepin’s chart to determine how many sets and reps I do during my workouts. This chart is based on research done with Russian weightlifters during the 1970s and 1980s. In my experience, it works very well. 1

To use the chart, you start with your one-rep max. A one-rep max is the most weight you can lift for a single repetition. Then, you decide what percentage of your one-rep max you want to lift during your workout. As I recommended above, I think 70 percent is a good place to start for The Tiny Gains Challenge.

According to Prilepin’s chart, if you are lifting a weight that is 70 percent of your max, then you should shoot for an optimal number of 18 repetitions in total with an acceptable range between 12 and 24 reps. According to the table, you can break these 18 reps out into sets of 3 to 6 repetitions. That means you can do 3 sets of 6 reps (18 in total), 6 sets of 3 reps (18 in total), 4 sets of 5 reps (20 in total), 4 sets of 4 reps (16 in total), and many other combinations. Any of those are within the acceptable range of 12 to 24 reps and they are all very close to the optimal number of 18 total reps.

How much should I add each week if I lift ___ pounds? The Tiny Gains Challenge is about making tiny gains each week. When lifting weights, I define tiny as being one pound per week or an improvement of 1 percent, whichever is smaller. So, if you’re bench pressing 50 lbs, then you should increase to 50.5 lbs next week (+1%). If you squat 300 lbs this week, then squat 301 lbs next week (+1 lb).

“What if it feels like I can add more than one pound?” This challenge will require patience. In my experience, one of the hardest parts of this challenge is having the discipline and patience to only go up by one pound per week even when it feels easy. After a week or two of feeling good, you’ll find yourself being pulled in. “Oh, I’m supposed to increase from 13 pounds to 14 pounds today? I could easily do 15 lbs. I’ll just toss that on there.” Don’t fall into this trap. Start with something easy, stick with something easy, and make tiny gains.

How many exercises can I do this for? Resist the urge to transform every aspect of your fitness habits overnight. I’d recommend you start with one exercise like I did with chin-ups and pour your energy and focus into not missing workouts. Once you find that you’re showing up consistently it is an easy transition to making tiny gains in more than one exercise.

What happens if I miss a workout? If you miss a workout (or even a week’s worth of workouts), then simply repeat the same weight you did before the next time. If you miss more than one week in a row, then you will need to drop the weight or, if it’s a gap of a month or more, simply start over.

“What if I do something instead of lifting weights?” That’s great! The Tiny Gains Challenge is about making tiny improvements in fitness. You can use it with any exercise: running, swimming, biking, pushups, burpees, and so on. Browse the examples below for more ideas.

“I have no idea where to begin and I don’t want to spend any money.” No worries! You can do the Tiny Gains Challenge by increasing your repetitions of an exercise or the distance you travel, not just with weight increases. If you’re not sure where to start, then I would suggest doing pushups or walking. You’ll find examples for both exercises listed below.

Where should I post my progress and ask questions? If you want to share your progress or follow along with other members of our community, then use the #tinygains hashtag. You’re welcome to post photos, videos, or just text updates. I’ll be sharing my workouts on on Instagram and you can ask me questions there, but you can use that hashtag anywhere (Twitter, Facebook, etc.).

Examples

Here are a few examples of how to do the Tiny Gains Challenge for various exercises. You are welcome to adapt the principles of this challenge for any exercise you do.

Squats: Let’s say your maximum squat is 200 pounds. Start with 70 percent of your max, or 140 pounds, the first week. Do four sets of five reps. Increase by one pound each week, so you will lift 141 pounds for four sets of five reps next week.

Bench Press: Let’s say your maximum bench press is 75 pounds. Start with 70 percent of your max, or 52.5 lbs, the first week. Do 4 sets of 5 reps. Increase by one half pound each week, so you will do 53 pounds for four sets of five reps next week.

Pushups: Start with an amount of pushups that seems very easy to you. Let’s say that you can do twenty pushups in a row. 5 pushups might be a very easy number for you. The first week, do five pushups per day. The second week, increase by one rep and do six pushups per day. Continue increasing by one rep per week.

Walking: Walking is a great way to start The Tiny Gains Challenge. You should start with a distance that is easy for you and then figure out a way to measure that distance. How you measure it will be specific to your situation. Then, increase by a tiny amount each week.

For example:

If you’re walking on a track, maybe you walk around the track one time (400m) the first week and then you walk around one time plus another quarter of a lap the second week (500m).

If you’re walking on a trail, maybe you walk down to a big rock and back. The second week, you can walk down to the big rock, go 10 steps further, and then come back.

If you have a Fitbit or other tracking device, maybe you walk 5,000 steps per day during the first week. The second week, you can increase that to 5,100 steps per day. Again, the entire goal is to make a very tiny gain and keep the work easy week after week.

Footnotes

I believe the Prilepin’s chart was named after the Russian weighlifting coach, Alexander Sergeyevitch Prilepin.

August 20, 2015

It’s Not Just About What You Say, It’s About How You Live

For the last 2,000 years the Nguni people have lived on the lands of central and southern Africa. Today, the Nguni people are primarily spread across the southern and eastern portions of the African continent.

Given their long and rich culture, oral tradition and hand gestures are an important part of communication within the Nguni nations. The Nguni people speak not just with words, but also with their bodies.

For example, when receiving a gift, it is customary to do so while holding both hands out in a cupped position. According to Melanie Finney, a communications professor at DePauw University, this gesture signals that “the gift you give me means so much that I must hold it in two hands.” 1

The Manner In Which We Live

The gestures of the Nguni people provide one example of how gratitude is not just about what we say, but also about the manner in which we live.

This is an idea that we can apply to nearly any area of life:

As an athlete: the goal is not to talk about how fantastic you are as a leader, but to show your leadership by being a great teammate first and foremost.

As an entrepreneur: the goal is not to merely tell your customers that you care about them, but to show them that you care by how run your business and how you deliver your product.

As a partner: the goal is not to simply claim that you love your spouse, but to show them your love by the care that you infuse into little behaviors each day.

As a doctor or a customer service rep or a middle manager: the goal is not to explain why you’re good at your job, but to make each day a work of art by the way that you do your job.

Our behavior is perhaps the strongest indicator or what we believe and what we value. In the words of John F. Kennedy, “As we express our gratitude, we must never forget that the highest appreciation is not to utter words, but to live by them.”

Gratitude is not just about what we say, but how we live. And so it true for all of life. 2

Footnotes

Nonverbal Communication, South Africa by Melanie Finney.

Thanks to Chad Songy and his friend for originally pointing me toward Nguni hand gestures.

August 17, 2015

World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov on How to Build Confidence in the Face of Fear

Garry Kasparov and his long-time rival Anatoly Karpov—two of the greatest chess players of all-time—took their respective seats around the chess board. The 1990 World Chess Championship was about to begin.

The two men would play 24 games to decide the champion with the highest scoring player being declared the World Chess Champion. In total, the match would stretch for three months with the first 12 games taking place in New York and the final 12 games being played in Lyons, France.

Kasparov started off well, but soon began to make mistakes. He lost the seventh game and let multiple victories slip away during the first half of the tournament. After the first 12 games, the two men left New York with the match tied at 6-6. The New York Times reported that “Mr. Kasparov had lost confidence and grown nervous in New York.��� 1

If Kasparov was going to retain his title as the best in the world, it was going to take everything he had.

“Playing Kasparov Chess”

Josh Waitzkin was a chess prodigy as a child and won multiple U.S. Junior Championships before the age of 10. Along the way, Waitzkin and his father had the opportunity to connect with Garry Kasparov and discuss chess strategy with him. In particular, they learned how Kasparov dealt with remarkably difficult matches like the one he faced against Karpov in the 1990 World Chess Championship.

Waitzkin shares the story in his book, The Art of Learning (audiobook).

Kasparov was a fiercely aggressive chess player who thrived on energy and confidence. My father wrote a book called Mortal Games about Garry, and during the years surrounding the 1990 Kasparov-Karpov match, we both spent quite a lot of time with him.

At one point, after Kasparov had lost a big game and was feeling dark and fragile, my father asked Garry how he would handle his lack of confidence in the next game. Garry responded that he would try to play the chess moves that he would have played if he were feeling confident. He would pretend to feel confident, and hopefully trigger the state.

Kasparov was an intimidator over the board. Everyone in the chess world was afraid of Garry and he fed on that reality. If Garry bristled at the chessboard, opponents would wither. So if Garry was feeling bad, but puffed up his chest, made aggressive moves, and appeared to be the manifestation of Confidence itself, then opponents would become unsettled. Step by step, Garry would feed off his own chess moves, off the created position, and off his opponent’s building fear, until soon enough the confidence would become real and Garry would be in flow…

He was not being artificial. Garry was triggering his zone by playing Kasparov chess.

—Josh Waitzkin, The Art of Learning

When the second half of the World Chess Championship began in Lyons, France, Kasparov forced himself to play aggressive. He took the lead by winning the 16th game. With his confidence building, he rattled off decisive wins in the 18th and 20th games as well. When it was all said and done, Kasparov lost only two of the final 12 games and retained his title as World Chess Champion.2

He would continue to hold the title for another 10 years.

“Fake It Until You Become It”

It can be easy to view performance as a one-way street. We often hear about a physically gifted athlete who underperforms on the field or a smart student who flounders in the classroom. The typical narrative about underachievers is that if they could just “get their head right” and develop the correct “mental attitude” then they would perform at the top of their game.

There is no doubt that your mindset and your performance are connected in some way. But this connection works both ways. A confident and positive mindset can be both the cause of your actions and the result of them. The link between physical performance and mental attitude is a two-way street.

Confidence is often the result of displaying your ability. This is why Garry Kasparov’s method of playing as if he felt confident could lead to actual confidence. Kasparov was letting his actions inspire his beliefs.

These aren’t just feel-good notions or fluffy self-help ideas. There is hard science proving the link between behavior and confidence. Amy Cuddy, a Harvard researcher who studies body language, has shown through her groundbreaking research that simply standing in more confident poses can increase confidence and decrease anxiety.

Cuddy’s research subjects experienced actual biological changes in their hormone production including increased testosterone levels (which is linked to confidence) and decreased cortisol levels (which is linked to stress and anxiety). These findings go beyond the popular fake it until you make it philosophy. According to Cuddy, you can “fake it until you become it.”

How to Build Confidence

When my friend Beck Tench began her weight loss journey, she repeatedly asked herself the question, “What would a healthy person do?”

When she was deciding what to order a restaurant: what would a healthy person order? When she was sitting around on a Saturday morning: what would a healthy person do with that time? Beck didn’t feel like a healthy person at the start, but she figured that if she acted like a healthy person, then eventually she would become one. And within a few years, she had lost over 100 pounds.

Confidence is a wonderful thing to have, but if you find yourself overcome with fear, self-doubt, or uncertainty then let your behavior drive your beliefs. Play as if you���re at your best. Work as if you���re on top of your game. Talk to that person as if you���re feeling confident. You can use bold actions to trigger a bold mindset.

In short, what would a brave person do? 3

Read Next

How to Be Confident and Reduce Stress in 2 Minutes Per Day

Bob Mathias on How to Master the Art of Self-Confidence

The Best Self-Help Books for Increasing Confidence

Footnotes

With a Draw, Kasparov Keeps Title by Steven Greenhouse. December 27, 1990.

The World Chess Championship 1990.

Thanks to Derek Sivers for posting his notes on The Art of Learning, which mentioned Kasparov and sent me down the rabbit hole of chess history and, ultimately, led to this post. And thanks to Kristy, the love of my life, for coming up with the phrase, “What would a brave person do?”

August 13, 2015

Getting to Simple: How Do Experts Figure out the Correct Things to Focus On?

Peak performance experts say things like, ���You should focus. You need to eliminate the distractions. Commit to one thing and become great at that thing.���

This is good advice. The more I study successful people from all walks of life—artists, athletes, entrepreneurs, scientists—the more I believe focus is a core factor of success.

But there is a problem with this advice too.

Of the many options in front of you, how do you know what to focus on? How do you know where to direct your energy and attention? How do you determine the one thing that you should commit to doing?

I don���t claim to have all the answers, but let me share what I���ve learned so far.

“Until Something Comes Easily…”

Like most entrepreneurs, I struggled through my first year of building a business.

I launched my first product without having any idea who I would sell it to. (Big surprise, nobody bought it.) I reached out to important people, mis-managed expectations, made stupid mistakes, and essentially ruined the chance to build good relationships with people I respected. I attempted to teach myself how to code, made one change to my website, and deleted everything I had done during the previous three months.

To put it simply, I didn’t know what I was doing.

During my Year of Many Errors I received a good piece of advice: “Try things until something comes easily.” I took the advice to heart and tried four or five different business ideas over the next 18 months. I’d give each one a shot for two or three months, mix in a little bit of freelance work so I could continue scraping by and paying the bills, and repeat the process.

Eventually, I found “something that came easily” and I was able to focus on building one business rather than trying to find an idea. In other words, I was able to simplify.

This was the first thing I discovered about figuring out the right things to focus on. If you want to master and deeply understand the core fundamentals of a task you may, paradoxically, need to start by casting a very wide net. By trying many different things you can get a sense of what comes more easily to you and set yourself up for success. It is much easier to focus on something that’s working than struggle along with a bad idea.

Make a Call

Assuming you’re willing to try things and experiment a bit, the next question is, “How do I know what’s coming easily to me?”

The best answer I can give is to pay attention. Usually this means measuring something.

If you’re an entrepreneur, track your marketing and promotion efforts.

If you’re trying to gain muscle, track your workouts.

If you’re learning an instrument, track your practice sessions.

Even when you do measure things, however, there comes a point where you have to make a call.

In my mind, this moment of decision is one of the central tensions of entrepreneurship. Do we continue trying new things or do we double down on one strategy? Do we try to innovate or do we commit to doing one thing well?

Everyone wants to know the right time to simplify and focus on one thing, but nobody does. That’s what makes success so hard. Entrepreneurship isn���t like baking a cake. There is no recipe. There is no guidebook. 1

At this stage your best option is to decide. You can’t try everything. At some point, you don’t need more information, you just need to make a choice.

A Volume of Work

Now we have reached the stage where figuring out the correct things to focus on becomes a real possibility.

You have experimented with enough ideas to discover one or two options that seem to provide better than average results for you. You’ve overcome the hurdle of wanting more information and the fear of committing to something and now you’ve made a choice. You took the job. You started the business. You signed up for the class. You’re ready.

Welcome to the grind. It’s time to put in a volume of work. Not just once or twice. Not just when it’s easy. But a consistent, repeated volume of work.

It is through this sheer number of repetitions that you’ll come to understand the fundamentals of your task. You might know what greatness looks like before this point, but you won’t understand how to achieve greatness until you’ve put the work in yourself.

In the words of Ira Glass, “your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you���re making is kind of a disappointment to you.” You’ll bridge that gap between what you know is good and what you can produce yourself by putting in the reps.

This applies to so many areas of life.

Want to dress well and develop killer style? You���re going to have to try on a lot of clothes before you can simplify down to the essentials. You���ll probably have to buy a lot of clothes before you can really get a feel for what your day-in, day-out style is. I���m not a fan of promoting rampant consumerism, but if that���s the skill set you want to develop then it���s likely going to take some experimentation and effort.

Want to become a great cook? How many bad meals do you think you need to make before you can whip up a ���simple, but tasty dinner��� whenever you feel like it? I���d say hundreds at least. I don���t know many people who are amazing cooks after making their tenth meal ever. Developing a deep understanding the fundamentals of cooking takes a while.

What to write an amazing book? You’re going to have to write and write and write some more. You need to write hundreds of thousands of words to find your voice, maybe millions. Then you need to edit those words and whittle them down to the most powerful version possible.

Only after the repetitions have been completed will you understand which pieces of the task are fundamental to success.

Getting to Simple

Now, finally, after trying many things and committing to an idea and putting in enough reps, you can begin to simplify. You can trim away the fat because you know what is essential and what is unnecessary.

As the Frenchman Blaise Pascal famously wrote in his Provincial Letters, “If I had more time, I would have written you a shorter letter.”

Mastering the fundamentals is often the hardest and longest journey of all.

Footnotes

Furthermore, everyone has different timelines. If you’re sitting on a bunch of cash, you can afford to try even more ideas, experiment a little longer, and see if you come across a better idea. If time is short and your options are slim, you have to make a call with what you have in front of you.

August 10, 2015

First Principles: Elon Musk and Bill Thurston on the Power of Thinking for Yourself

Bill Thurston was a pioneer in the field of mathematics. He was particularly known for his contributions to low-dimensional topology, 3-manifolds, and foliation theory—concepts that sound foreign to number-challenged mortals like you and me.

In 1982, Thurston was awarded the Fields Medal, which is often considered the highest honor a mathematician can receive. One reason Thurston was able to contribute valuable insights to his field of mathematics was that he utilized a different set of mental models than his peers.

In a paper he wrote for the American Mathematical Society—which, no joke, I found to be a fascinating read—Thurston explains his approach to solving difficult problems. 1

“My mathematical education was rather independent and idiosyncratic, where for a number of years I learned things on my own, developing personal mental models for how to think about mathematics. This has often been a big advantage for me in thinking about mathematics, because it’s easy to pick up later the standard mental models shared by groups of mathematicians. This means that some concepts that I use freely and naturally in my personal thinking are foreign to most mathematicians I talk to.”

—Bill Thurston

Self-taught mental models—or, in simple terms, figuring things out for yourself—seem to be a favorite weapon of brilliant minds. (Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, also relied heavily on personal mental models.) In many cases, it is the unique point-of-view afforded by self-directed learning and deep thought that enables someone to unleash an idea of minor genius.

How can you go about developing a unique view of the world?

First Principles Thinking

Elon Musk is perhaps the boldest entrepreneur on the planet right now. After helping revolutionize online payments as the founder of PayPal, Musk now runs three companies: Tesla Motors (electric cars), SpaceX (space exploration and tourism), and Solar City (solar energy).

In a fantastic interview with Kevin Rose, Musk explains one of the core philosophies that has guided him during his bold entrepreneurial ventures. 2

“I think it is important to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. The normal way we conduct our lives is we reason by analogy. [When reasoning by analogy] we are doing this because it���s like something else that was done or it is like what other people are doing ��� slight iterations on a theme.

First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world. You boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say, “What are we sure is true?” … and then reason up from there.

Somebody could say, “Battery packs are really expensive and that���s just the way they will always be��� Historically, it has cost $600 per kilowatt hour. It���s not going to be much better than that in the future.”

With first principles, you say, “What are the material constituents of the batteries? What is the stock market value of the material constituents?”

It���s got cobalt, nickel, aluminum, carbon, some polymers for separation and a seal can. Break that down on a material basis and say, “If we bought that on the London Metal Exchange what would each of those things cost?”

It���s like $80 per kilowatt hour. So clearly you just need to think of clever ways to take those materials and combine them into the shape of a battery cell and you can have batteries that are much, much cheaper than anyone realizes.”

—Elon Musk

Reasoning by first principles is one of the best ways to develop mental models that are rare and useful. Put another way, forcing yourself to look at the fundamental facts of a situation can help you develop your own perspective on how to solve problems rather than defaulting to way the rest of the world thinks.

First Principles in Daily Life

This methodology extends beyond problems in science and business. Here are a few example of how we live everyday life by analogy and my attempt to uncover the first principles instead.

“Eating healthy and losing weight is hard work. Plus, I have to give up certain foods.” 3

First principles: What are we sure is true about eating healthy and losing weight? To eat healthy, you need to eat more whole foods to get a good balance of macronutrients and micronutrients. To lose weight, you need fewer overall calories each week. Is it possible to achieve those two things without it being “hard work” or requiring you to “give up certain foods?” Yes, you could hire a meal preparation service to deliver finished meals to you each week. 4

“Writers have poor career prospects and don’t make a lot of money.”

First principles: What is the core function of a writer? To create and share information. What is required to have a prosperous and fruitful career? To provide value that a company or a group of customers are willing to pay for. Can writers use their skill of creating and sharing information to provide value? Yes, they can. Are there writers already using this skill to provide value and make a very good living? Yes, there are writers doing that already. In other words, whether an individual writer has a successful career has more to do with how they choose to package their writing skills than whether or not the skill of writing itself is valuable.

“You have to be a risk-taker if you want to be a successful entrepreneur.”

First principles: What do you need to be an entrepreneur? You need something to sell and a way to get paid. Ok, you need something to sell. Does it have to be a risky product or service? Not at all. Many people buy “normal” products and services like bow ties and lawn maintenance and car insurance. But what about leaving it all behind and starting your own venture? Isn’t that risky even if you sell something boring? There is no rule that says you have to start as a full-time entrepreneur. In fact, that’s one of the great things about entrepreneurship: there are no rules. Keep your day job and work on nights and weekends. Or, save up a big emergency fund before jumping in.

We often live life by analogy and simply assume that what has been true before must be true in the future. Instead, break your problems down to their first principles and you may see very different solutions emerge.

Read Next

Mental Models: How Intelligent People Solve Unsolvable Problems

The Best Business Books on Decision Making

How to Solve Difficult Problems by Using the Inversion Technique

Footnotes

On Proof and Progress in Mathematics by William P. Thurston. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. Volume 30, Number 2, April 1994.

Seriously, the Kevin Rose – Elon Musk interview is awesome. You can watch the whole thing here.

Hat tip to Bruce Achterberg. I got this example from his post about first principles on Quora.

Important note: Meal preparation services aren’t as expensive as you might imagine. You can often get meals (including shipping) for $8 or less. However, I still realize that this is out of budget for many people, so I don’t want you to think that I’m delusional by offering this example. Regardless of how feasible getting a meal service is for you personally, this is a good example of how we often assume one version of a story to be the one-and-only truth while other solutions become obvious if we reason from first principles.

August 6, 2015

The Chemistry of Building Better Habits

There is a concept in chemistry known as activation energy.

Here���s how it works:

Activation energy is the minimum amount of energy that must be available for a chemical reaction to occur. Let’s say you are holding a match and that you gently touch it to the striking strip on the side of the match box. Nothing will happen because the energy needed to activate a chemical reaction and spark a fire is not present.

However, if you strike the match against the strip with some force, then you create the friction and heat required to light the match on fire. The energy you added by striking the match was enough to reach the activation energy threshold and start the reaction.

Chemistry textbooks often explain activation energy with a chart like this:

It���s sort of like rolling a boulder up a hill. You have to add some extra energy to the equation to push the boulder to the top. Once you���ve reached the peak, however, the boulder will roll the rest of the way by itself. Similarly, chemical reactions require additional energy to get started and then proceed the rest of the way.

Alright, so activation energy is involved in chemical reactions all around us, but how is this useful and practical for our everyday lives?

The Activation Energy of New Habits

Similar to how every chemical reaction has an activation energy, we can think of every habit or behavior as having an activation energy as well.

This is just a metaphor of course, but no matter what habit you are trying to build there is a certain amount of effort required to start the habit. In chemistry, the more difficult it is for a chemical reaction to occur, the bigger the activation energy. For habits, it���s the same story. The more difficult or complex a behavior, the higher the activation energy required to start it.

For example, sticking to the habit of doing 1 pushup per day requires very little energy to get started. Meanwhile, doing 100 pushups per day is a habit with a much higher activation energy. It’s going to take more motivation, energy, and grit to start complex habits day after day.

The Disconnect Between Goals and Habits

Here���s a common problem that I���ve experienced when trying to build new habits:

It can be really easy to get motivated and hyped up about a big goal that you want to achieve. This big goal leads you to think that you need to revitalize and change your life with a new set of ambitious habits. In short, you get stuck dreaming about life-changing outcomes rather than making lifestyle improvements.

The problem is that big goals often require big activation energies. In the beginning you might be able to find the energy to get started each day because you’re motivated and excited about your new goal, but pretty soon (often within a few weeks) that motivation starts to fade and suddenly you���re lacking the energy you need to activate your habit each day.

This is lesson one: Smaller habits require smaller activation energies and that makes them more sustainable. The bigger the activation energy is for your habit, the more difficult it will be to remain consistent over the long-run. When you require a lot of energy to get started there are bound to be days when starting never happens.

Finding a Catalyst for Your Habits

Everyone is on the lookout for tactics and hacks that can make success easier. Chemists are no different. When it comes to dealing with chemical reactions, the one trick chemists have up their sleeves is to use what is known as a catalyst.

A catalyst is a substance that speeds up a chemical reaction. Basically, a catalyst lowers the activation energy and makes it easier for a reaction to occur. The catalyst is not consumed by the reaction itself. It���s just there to make the reaction happen faster.

Here���s a visual example:

When it comes to building better habits, you also have a catalyst that you can use:

Your environment.

The most powerful catalyst for building new habits is environment design (what some researchers call choice architecture). The idea is simple: the environments where we live and work influence our behaviors, so how can we structure those environments to make good habits more likely and bad habits more difficult?

Here is an example of how your environment can act as a catalyst for your habits:

Imagine you are trying to build the habit of writing for 15 minutes each evening after work. A noisy environment with loud roommates, rambunctious children, or constant television noise in the background will require a high activation energy to stick with your habit. With so many distractions, it���s likely that you���ll fall off track with your writing habit at some point. Meanwhile, if you stepped into a quiet writing environment—like a desk at the local library—your surroundings suddenly become a catalyst for your behavior and make it easier for the habit to proceed.

Your environment can catalyze your habits in big and small ways. If you set your running shoes and workout clothes out the night before, you just lowered the activation energy required to go running the next morning. If you hire a meal service to deliver low calorie meals to your door each week, you significantly lowered the activation energy required to lose weight. If you unplug your television and hide it in the closet, you just lowered the activation energy required to watch less television.

This is lesson two: The right environment is like a catalyst for your habits and it lowers the activation energy required to start a good habit.

The Intermediate States of Human Behavior

Chemical reactions often have a reaction intermediate, which is like an in-between step that occurs before you can get to the final product. So, rather than going straight from A to B, you go from A to X to B. An intermediate step needs to occur before we go from starting to finishing.

There are all sorts of intermediate steps with habits as well.

Say you want to build the habit of working out. Well, this could involve intermediate steps like paying a gym membership, packing your gym bag in the morning, driving to the gym after work, exercising in front of other people, and so on.

Here���s the important part:

Each intermediate step has its own activation energy. When you���re struggling to stick with a new habit it can be important to examine each link in the chain and figure out which one is your sticking point. Put another way, which step has the activation energy that prevents the habit from happening?

Some intermediate steps might be easy for you. To continue our fitness example from above, you might not care about paying for a gym membership or packing your gym bag in the morning. However, you may find that driving to the gym after work is frustrating because you end up hitting more rush hour traffic. Or you may discover that you don���t enjoy working out in public with strangers.

Developing solutions that remove the intermediate steps and lower the overall activation energy required to perform your habit can increase your consistency in the long-run. For example, perhaps going to the gym in the morning would allow you to avoid rush hour traffic. Or maybe starting a home workout routine would be best since you could skip the traffic and avoid exercising in public. Without these two barriers, the two intermediate steps that were causing friction with your habit, it will be much easier to follow through.

This is the lesson three: Examine your habits closely and see if you can eliminate the intermediate steps with the highest activation energy (i.e. the biggest sticking points).

The Chemistry of Building Better Habits

The fundamental principles of chemistry reveal some helpful strategies that we can use to build better habits.

Every habit has an activation energy that is required to get started. The smaller the habit, the less energy you need to start.

Catalysts lower the activation energy required to start a new habit. Optimizing your environment is the best way to do this in the real world. In the right environment, every habit is easier.

Even simple habits often have intermediate steps. Eliminate the intermediate steps with the highest activation energy and your habits will be easier to accomplish.

And that���s the chemistry of building better habits.

Read Next

The Physics of Productivity: Newton���s Laws of Getting Stuff Done

The Best Psychology Books for Building Better Habits

Transform Your Habits: Free 45-page Guide on How to Stick to Good Habits and Break Bad Ones

August 3, 2015

August Reading List: 5 Good Books to Read This Month

It’s time for another edition of my reading list.

In addition to the five books reviewed below, I maintain a complete list of the best books I���ve read across a wide range of disciplines.

Here are a few of the top books I’ve read recently.

A Short Guide to a Happy Life by Anna Quindlen

The Book in Three Sentences: The only thing you have that nobody else has is control of your life. The hardest thing of all is to learn to love the journey, not the destination. Get a real life rather than frantically chasing the next level of success.

Key Ideas: This is a list of key ideas that I recorded while reading the book. These notes are informal and include quotes from the book as well as my own thoughts.

The only thing you have that nobody else has is control of your life. You job, your day, your heart, your spirit. You are the only one in control of that.

“Show up. Listen. Try to laugh.”

“You cannot be really good at your work if your work is all you are.”

“Get a life, a real life. Not a manic pursuit of the next promotion.”

“Turn off your cell phone. Keep still. Be present.”

“Get a life in which you are generous.”

“All of us want to do well, but if we do not do good too then doing well will never be enough.”

“Knowledge of our own mortality is the greatest gift God gives us.” It is so easy to exist rather than to live… Unless you know a clock is ticking.

We live in more luxury today than ever before. The things we have today our ancestors thought existed for just the wealthy. And yet, somehow, we are rarely grateful for all this wealth.

The hardest thing of all is to learn to love the journey, not the destination.

“This is not a dress rehearsal. Today is the only guarantee you get.”

“Think of life as a terminal illness.”

“School never ends. The classroom is everywhere.”

3 Reasons to Read This Book

You need a reminder of why you should be grateful for the life you live.

You need a reminder of why it is important to live a balanced life.

You want to be inspired and you like short books.

Buy This Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism by Naoki Higashida

The Book in Three Sentences: This book is an autobiography written by a 13-year-old boy from Japan about what it is like to live with autism. The way autistic people view the world is very different than the way we may perceive them to view the world. This disconnect between how we view and treat people with autism and how they actually view the world makes living with autism is even more difficult than it already is.

Key Ideas: This is a list of key ideas that I recorded while reading the book. These notes are informal and include quotes from the book as well as my own thoughts.

���When you see an object, it seems that you see it as an entire thing first, and only afterwards do its details follow on. But for people with autism, the details jump straight out at us first of all, and then only gradually, detail by detail, does the whole image float up into focus.���

���On our own we simply don’t know how to get things done the same way you do things. But, like everyone else, we want to do the best we possibly can. When we sense you’ve given up on us, it makes us feel miserable. So please keep helping us, through to the end.���

���But I ask you, those of you who are with us all day, not to stress yourselves out because of us. When you do this, it feels as if you’re denying any value at all that our lives may have–and that saps the spirit we need to soldier on. The hardest ordeal for us is the idea that we are causing grief for other people. We can put up with our own hardships okay, but the thought that our lives are the source of other people’s unhappiness, that’s plain unbearable.���

���True compassion is about not bruising the other person���s self-respect.���

���To give the short version, I’ve learnt that every human being, with or without disabilities, needs to strive to do their best, and by striving for happiness you will arrive at happiness. For us, you see, having autism is normal — so we can’t know for sure what your ‘normal’ is even like. But so long as we can learn to love ourselves, I’m not sure how much it matters whether we’re normal or autistic.���

���Everybody has a heart that can be touched by something.���

There is a fantastic story that Higashida tells about learning to wave goodbye to a friend. People kept telling him that he was doing it incorrectly, but he didn’t understand why until someone had him look in a mirror. He finally realized that he was waving goodbye to himself with his palm facing toward his own face rather than his palm facing away and toward the other person. He was simply mimicking what he saw when someone waved goodbye to him (the other person’s palm), but couldn’t fully translate what he saw into the correct behavior.

He spends much of his day feeling like a failure and knows he screws up often.

Childish behavior does not equal childish intelligence.

My biggest takeaway was that when it comes to many everyday circumstances Higashida “gets it,” but he can’t act on it. Perhaps I was just ignorant about autism, but I feel that we often assume that autistic people are “out of it” and aren’t really following what’s going on. (And how would we know when we have no outward or physical indication otherwise?) But he does understand. He gets context and subtlety. He knows what is happening even if he can’t take appropriate action.

3 Reasons to Read This Book

You don’t know much about autism or what it’s like to live with autism and you’re interested enough to learn more.

You’d like a glimpse inside the mind of someone who is likely very different from you.

You want to be reminded of how every life has value.

Buy This Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

The Martian: A Novel by Andy Weir

Summary: Hot damn. This is my favorite fiction book that I’ve read this year. If you like space, read this book. If you like science, read this book. If you like the idea of humans somehow landing on Mars, read this book. The book has a great premise and the author did a fantastic job of blending his fictional world with believable engineering and real-world science. I thought it was great. (Plus, it’s being made into a movie starring Matt Damon. Here’s the trailer.)

Buy This Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia by Mohsin Hamid

Summary: I read this book after venture capitalist Chris Sacca recommended it. The novel begins with a poor child living in rural Asia and progresses through his life as he moves to the city and takes step after step in the pursuit of wealth and success. My biggest takeaways were 1) most people in the world live very differently than you do, 2) there is a lot of corruption and cheating in business, 3) there are many people who sacrifice love and relationships to achieve success and it rarely seems to be worth it.

3 Reasons to Read This Book

You want a sobering reminder of the sacrifice success often requires.

You want to follow an exciting story that carries you through many different stages of life.

You want to learn how to get filthy rich in rising Asia.

Buy This Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

The Redbreast by Jo Nesbo

Summary: The Redbreast is one of a series of novels by crime writer Jo Nesbo. All of the mystery novels feature Harry Hole as the primary detective. This one spans 60 years and involves all of the plot twists you would expect in a mystery novel. It’s a good book although I personally enjoyed Stieg Larsson’s books more, if we’re splitting hairs over Scandinavian fiction writers.

2 Reasons to Read This Book

You like thriller and mystery novels.

You want to start reading Jo Nesbo, who is considered one of the top Scandinavian crime writers alive.

Buy This Book: Print | eBook | Audiobook

How to Get Free Audiobooks

I have shared my strategy for how to read more books previously, but I also love listening to audiobooks. I have a monthly subscription to Audible and I really enjoy it.

Good news: if you start a 30-day free trial with Audible right now, you can get your first 2 audiobooks free. Here’s the best part: You get to keep the 2 audiobooks, even if you cancel the trial. It’s a no-brainer. You can sign up here.

More Book Recommendations

Looking for more good books to read? Browse the full reading list, which lists the best books in each category.

Enjoy!

July 30, 2015

How to Stop Lying to Ourselves: A Call for Self-Awareness

It was September of 1816 and two Parisian boys were playing in the courtyard of the Louvre, the famous museum in Paris.

On the other side of the courtyard, a physician named Ren�� Laennec began to quicken his pace as he walked along in the morning sun. There was a woman with heart disease waiting for him at the hospital and Laennec was late.

As Laennec crossed the courtyard, he looked toward the two boys. One of them was tapping the end of a long wooden plank with a pin. On the other end, his playmate was crouched down with his ear pressed against the edge of the plank.

Laennec was immediately struck with a thought. “I recalled a well-known acoustic phenomenon,” he would later write. “If you place your ear against one end of a wood beam the scratch of a pin at the other end is distinctly audible. It occurred to me that this physical property might serve a useful purpose in the case I was dealing with.”

When Laennec arrived at the hospital later that morning, he immediately asked for a piece of paper. He rolled it up and placed the tube against his patient���s chest. He was stunned by what he heard next. “I was surprised and elated to be able to hear the beating of her heart with far greater clearness than I ever had with direct application of my ear,” he said.

Ren�� Laennec had just invented the stethoscope.

Laennec quickly upgraded from his piece of paper and, after experimenting with various sizes, he began using a hollow wood tube about 3.5 centimeters in diameter and 25 centimeters long. 1

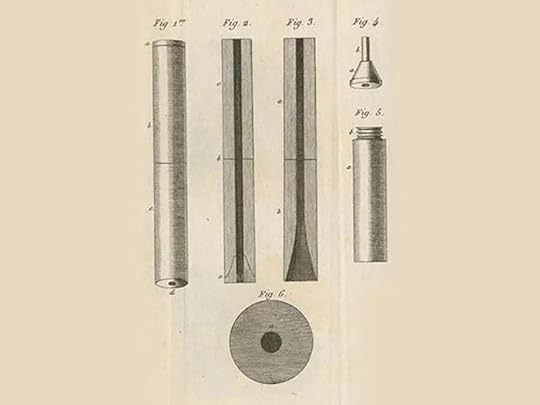

This is a sketch of Ren�� Laennec’s original stethoscope design, which was essentially a hollow wood tube. The ear piece is featured in the top right corner. (Image Source: US National Library of Medicine.)

This is a sketch of Ren�� Laennec’s original stethoscope design, which was essentially a hollow wood tube. The ear piece is featured in the top right corner. (Image Source: US National Library of Medicine.)Laennec’s simple invention instantly changed the field of medicine.

For the first time in history, physicians had a safe, unbiased way to understand what was going on inside a patient’s body. They didn’t have to rely solely on what the patient said or how the patient described their condition. Now, they could track and measure things for themselves. The stethoscope was like a window that allowed a doctor to view what was actually happening and then compare their findings to the symptoms, outcomes, and autopsies of patients.

And that brings us to the main point of this story.

The Lies We Tell Ourselves

We often lie to ourselves about the progress we are making on important goals.

For example:

If we want to lose weight, we might claim that we’re eating healthy, but in reality our eating habits haven’t changed very much.

If we want to be more creative, we might say that we’re trying to write more, but in reality we aren’t holding ourselves to a rigid publishing schedule.

If we want to learn a new language, we might say that we have been consistent with our practice even though we skipped last night to watch television.

We use lukewarm phrases like, “I’m doing well with the time I have available.” Or, “I’ve been trying really hard recently.” Rarely do these statements include any type of hard measurement. They are usually just soft excuses that make us feel better about having a goal that we haven’t made much real progress toward. (I know because I’ve been guilty of saying many of these things myself.)

Why do these little lies matter?

Because they are preventing us from being self-aware. Emotions and feelings are important and they have a place, but when we use feel-good statements to track our progress in life, we end up lying to ourselves about what we’re actually doing.

When the stethoscope came along it provided a tool for physicians to get an independent diagnosis of what was going on inside the patient. We can also use tools to get a independent diagnosis of what is going on inside our own lives.

Tools for Improving Self-Awareness

If you’re serious about getting better at something, then one of the first steps is to know—in black-and-white terms—where you stand. You need self-awareness before you can achieve self-improvement.

Here are some tools I use to make myself more self-aware:

Workout Journal – For the past 5 years or so, I have used my workout journal to record each workout I do. While it can be interesting to leaf back through old workouts and see the progress I’ve made, I have found this method to be most useful on a weekly basis. When I go to the gym next week, I will look at the weights I lifted the week before and try to make a small increase. It’s so simple, but the workout journal helps me avoid wasting time in the gym, wandering around, and just “doing some stuff.” With this basic tracking, I can make focused improvements each week.

My Annual Reviews and Integrity Reports – At the end of each year, I conduct my Annual Review where I summarize the progress I’ve made in business, health, travel, and other areas. I also take time each spring to do an Integrity Report where I challenge myself to provide proof of how I am living by my core values. These two practices give me a chance to track and measure the “softer” areas of my life. It can be difficult to know for certain if you’re doing a better job of living by your values, but these reports at least force me to track these issues on a consistent basis.

RescueTime – I use RescueTime to track how I spend my working hours each week. For a long time, I just assumed that I was fairly productive. When I actually tracked my output, however, I’ve uncovered some interesting insights. For example, I currently spend about 60 percent of my time each week on productive tasks. This past month, I spent 9 percent of my working time on social media sites. If you would have asked me to estimate those two numbers before using RescueTime, I’m certain I would have been way off. Now, I actually have a clear idea of how I spend my time and because I know where I truly stand, I can start to make calculated and measured improvements.

A Call for Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is one of the fundamental pieces of behavior change and one of the pillars of personal science.

If you aren’t aware of what you’re actually doing, then it is very hard to change your life with any degree of consistency. Trying to build better habits without self-awareness is like firing arrows into the night. You can’t expect to hit the bullseye if you’re not sure where the target is located.

Furthermore, I have discovered very few people who naturally do the right thing without ever measuring their behavior. For example, I know a handful of people who maintain six-pack abs without worrying too much about what they eat. However, every single one of them weighed and measured their food at some point. After months of counting calories and measuring their meals, they developed the ability judge their meals appropriately.

In other words, measurement brought their levels of self-awareness in line with reality. You can wing it after you measure it. Once you’re aware of what’s actually going on, you can make accurate decisions based on “gut-feel” because your gut is based on something accurate.

In short, start by measuring something. 2

Read Next

Inside the Mind of a Mad Scientist: The Incredible Importance of Personal Science

Measure Backward, Not Forward

Footnotes

Rubber tubing wasn���t developed until the second-half of the 19th century, which is when stethoscopes resembling modern designs were first produced. Further details are explained in this piece called, ���The Man Behind the Stethoscope��� from a 2006 edition of Clinical Medicine and Research. That article is also the source where I found the quotes from Laennec used in this article.

Thanks to NPR���s Science Friday segment, where I originally heard the story of the origin of the stethoscope from Ira Flatow and Howard Markel.

July 27, 2015

The Repeated Bout Effect: If Nothing Changes, Nothing Is Going to Change

If you have ever taken a few weeks off from exercise and then completed a strenuous workout, you may know what I’m about to say.

That first workout back from a long break can be tough, but it’s usually the soreness that follows a few days later that is really brutal. For example, if you do a squat workout after a few weeks off, it can hurt to simply sit in a chair or climb the stairs later that week. 1

One of the quickest ways to resolve this soreness is very counterintuitive:

Squat again.

If I’m feeling sore a few days after a squat workout, then doing some light reps is often the quickest way to recover from the soreness. I’ll usually opt for three sets of ten bodyweight squats. The first few are uncomfortable, but then my muscles limber up and I feel significantly better by the end of it.

How could this be? If squatting caused the pain, then why would more squatting resolve it? It’s sort of like saying, “I spent too much money, so my solution is to spend a little more money.”

On the surface, this makes little sense. But, as you may expect, there is something deeper going on here. It’s called the Repeated Bout Effect and it applies to much more than just exercise.

The Repeated Bout Effect

Here���s the Repeated Bout Effect in plain language:

The more you repeat a behavior, the less it impacts you because you become accustomed to it.

The Repeated Bout Effect comes from exercise science research, so let’s return to our previous squat example.

When you perform a new squat workout your body will experience a new stimulus that stresses your muscles and, eventually, results in muscle soreness. However, the way you respond to this new stimulus is not constant. Researchers have found that “a repeated bout results in reduced symptoms.” 2 Generally speaking, the more consistently you squat, the less soreness you will experience.

This is what is known as the Repeated Bout Effect. Your body’s response to a stimulus decreases with each repeated bout.

There are hundreds of research studies confirming the Repeated Bout Effect. The exact mechanism by which it occurs isn’t totally understood, but the fact that it does occur has been well-established. 3

The Repeated Bout Effect in Your Life

The Repeated Bout Effect tells us that the more we do something, the less of an impact it makes on us. There are many ways to think about this effect throughout life.

When you haven’t done much strength training, doing thirty pushups will make you stronger. After a few months of that, however, an extra thirty pushups isn’t really building new muscle.

When you drink coffee for the first time, you will notice an immediate caffeine spike. After years of consumption, however, one cup of coffee seems to make less of a difference.

When you start eating smaller portions, you’ll lose weight. After the first ten or fifteen pounds fall off, however, your smaller portion slowly becomes your normal portion and weight loss stalls.

Making ten sales calls on your first day in business may lead to a big jump in overall revenue. Making ten sales calls for the 300th day in a row, however, is unlikely to have a large impact on overall revenue.

These examples make sense when you see them neatly lined up in an article, but out in the real world we often curse ourselves for a lack of progress.

Let���s say you want to lose weight and you weren���t working out previously. You start running twice per week and pretty soon you’ve lost ten pounds. At some point, the Repeated Bout Effect kicks in, your body adapts, and the weight loss slows. Suddenly, you’re still running twice per week but the scale is no longer moving.

It can be very easy to interpret these diminishing results as some kind of failure.

“This always happens. I make a little bit of progress and then I hit a plateau.”

“Ugh, I’m working out every week and nothing is happening.”

“I’ve tried it all. Exercise doesn’t work for me.”

Except, it did work. In fact, your initial exercise worked exactly as it was supposed to because it delivered a new result and then your body adapted and became better. Now, your body has a new baseline and if you want to achieve a higher level of success, then you need to add something new to the mix.

3 Lessons On Improvement

The Repeated Bout Effect can teach us three lessons on improvement.

First, doing a light amount of work is a great way to reduce the pain of difficult sessions. Imagine that you do an easy 1-minute pushup workout on Monday and a difficult 10-minute pushup session on Friday. The Repeated Bout Effect says that your soreness after Friday’s workout will be reduced simply because you did an easy session earlier in the week. Easy work can make a difference.

Second, the amount of work that you need to do to reach your maximum level of output is higher than what you are doing now. Unless you are already performing at 100 percent of your potential, you have room to grow. And the Repeated Bout Effect tells us that you have probably adapted to all of the normal stimuli in your life. If you want to reach a new level of success then you need to put in a new level of work. This does not mean you should start by doing as much work as possible, but it does mean that when you start small you can’t expect one small change to work forever. You have to continually graduate to the next level.

Third, deliberate practice is critical to long-term success. Doing the same type of work over and over again is a strange form of laziness. You can���t go to the gym, run the same three miles each week, and expect to enjoy ever-improving results. After a few months of repetitive workouts, you���ve seen all the results that three-mile runs can deliver and your body has adapted to that stimulus. This is why deliberately practicing new skills that you can master in one to three practice sessions is important for long-term improvement. Making deliberate practice a habit can help you avoid carelessly practicing things that no longer deliver any benefit.

The key takeaway here is that things will work for a little while and then we will get used to them.

As Marshall Goldsmith says in his best-selling book, “What got you here won���t get you there.” Doing the same thing over and over again, even if it worked for a long time, will eventually lead to a plateau. If nothing changes, nothing is going to change. 4

Footnotes

Personally, I tend to experience greater-than-normal soreness when I take a break from strength training for longer than eight days. If I’m traveling for a ten day span, for example, fitting a workout in during day five or six ends up making a big difference in my levels of soreness when I return to a normal training schedule the following week.

The Repeated Bout Effect: Does Evidence for a Crossover Effect Exist? by Declan Connolly, Brian Reed, and Malachy McHugh.

Want to dive into the research? Here are two decent studies to kick things off. First, Temporal Pattern of the Repeated Bout Effect of Eccentric Exercise on Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness by Cleary, Kimura, Sitler, and Kendrick. Second, The repeated bout effect of reduced-load eccentric exercise on elbow flexor muscle damage by Nosaka, Sakamoto, Newton, and Sacco.

Thanks to Greg Nuckols and Justin Laczek for their writing and work on the Repeated Bout Effect, which prompted this article.