James Clear's Blog, page 4

December 31, 2016

My 2016 Annual Review

Well friends, 2016 is in the books. Before we turn the page and start a new chapter in 2017, I’d like to share my Annual Review with you.

I conduct my Annual Review at the end of each year. The process reminds me to look back on the previous twelve months, celebrate my victories, evaluate my failures, and hold myself accountable in public. I hope that you’ll find my stories, stumbles, and insights useful.

My 2016 Annual Review will answer three questions.

What went well this year?

What didn’t go so well this year?

What am I working toward?

You’re welcome to use a similar format for your own Annual Review.

1. What went well this year?

Alright, let’s cover the fun stuff first. Here’s what went well this year.

Hiring. My biggest win this year was making my first full-time hire. One great employee is worth ten mediocre freelancers. (Lyndsey, you’re the best.) I spent years suffering from “Superhero Syndrome” and I tried to handle every major aspect of the business by myself. Eventually, I realized that while this strategy allowed me to run the business “my way” it also prevented the business from growing beyond my limiting beliefs. When you’re the only person in the company, your mindset is also the company’s mindset. If you have a bad day, the company has a bad day. If you have a mental block with sales or marketing, the company has a mental block with sales or marketing. Thus, hiring has taught me an important lesson: The fastest way to get over your limiting beliefs is to hire someone who doesn’t have them.

Business growth. I made a lot of mistakes this year (more on that below), but thanks to the addition of Lyndsey and the groundwork I laid in previous years, JamesClear.com continued to grow in nearly every way despite my blunders.

Here are some quick stats…

28 new articles published this year (browse my best articles)

210,623 new email subscribers this year

373,938 total email subscribers as of December 31, 2015

7,956,860 unique visitors this year

16,794,628 unique visitors since launching on November 12, 2012

Almost eight million people visited JamesClear.com this year. When I think about that number for more than four seconds, two things happen. First, I become momentarily paralyzed by the idea that millions of people will judge what I write. Second, I remember that nobody cares that much and I start to feel the same awesome sense of excitement and possibility as when I first began writing.

The truth is, it doesn’t matter if you’re writing to one person or one million. The responsibility of a writer is always the same: if you’re going to interrupt someone with your words, you better be damn sure you have something good to say to them. For my part, I promise I’ll do my best to write things worth reading.

Travel. Exploring the world continues to be one of my top priorities in life and I was fortunate enough to make it to some great places this year. One of those places was Vietnam where I was stopped at least 17 times per day to get a photo with a random stranger. (It turns out that tall bald men are considered a rare and important species there. America should take note.) I also updated my Ultralight Travel Guide, which includes some of my favorite new travel gear.

Travel highlights for 2016:

7 countries (2 new): Bahamas, England, Iceland, Peru, Scotland, United States, Vietnam.

12 states (1 new): Arizona (2x), California (3x), Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas (2x), Utah.

Weightlifting. I like to think that I strike a reasonable balance between training hard and having a normal life. I love weightlifting, but not in the I-use-protein-powder-as-deodorant sort of way. Anyway, I have been slowly increasing the my training volume over the last three years. In 2014, I exercised 113 times. In 2015, I bumped that up to 122 workouts. In 2016, I switched my training style and completed 178 workouts for an average of 14.8 per month. Currently, I lift for about 45 minutes to 1 hour on Monday thru Friday.

Workouts per month in 2016:

January – 15

February – 17

March – 16

April – 9

May – 12

June – 22

July – 18

August – 19

September – 17

October – 9

November – 9

December – 15

My best lifts of the year were:

Back Squat – 415 lbs for 1 rep

Bench Press – 295 lbs for 1 rep

Deadlift – 501 lbs for 1 rep (at my first official powerlifting meet)

500m row – 1 minute 27 seconds

These were all personal bests for me, so I guess we could say that I was in the best shape of my life in 2016. (Although I doubt I could run a mile very well right now.)

Retreats. After thinking about it for years, I finally pulled the trigger and hosted a retreat for fellow authors in 2016. I also joined a group of entrepreneurs for two other retreats where I wasn’t the host. All of the deepest, most useful, and most inspiring conversations I had with fellow entrepreneurs and authors in 2016 happened at these retreats. Even in our digital world, the best connections still happen in person. I’m planning to host two of them in 2017 and I can’t wait.

2. What didn’t go so well this year?

Now for the ugly stuff. Meh.

Book writing. Plain and simple, 2016 was the worst year of writing of my young career. I haven’t been at this very long, but I’ve been at it long enough to know that this year was a total disaster from a writing standpoint.

It all started at the end of 2015 when I signed a major book deal with Penguin Random House. As soon as the book became a reality, my perfectionism kicked into high gear. In the quest to produce something great, I fell into a deep spiral of research and reading. I convinced myself I had to know everything that had been written about habits and human performance if I wanted to write a great book on the topic. Of course, that’s an impossible task and at some point you have to start writing. The end result was I did very little writing during the year and November rolled around without me having a finished draft.

Unfortunately, my decision to bury myself in book research not only prevented me from writing the book, but also from writing more articles. Of course, the year wasn’t a total loss—I still found a way to write almost 30 articles and guides—but my output paled in comparison to previous years. (If you’re interested, you can browse my 10 Best Articles of 2016.)

Looking back now, I realize that I spent a large part of 2016 learning how to create a new style of work. For the three years prior, I was writing a new article every Monday and Thursday. The focus was on creating great work that was usually 1,500 words or less. Now, my writing ambitions have grown and I’m working to create a really fantastic book of 50,000 words or more. This transition from rapid work to deep work has been hard for me. I’m just now learning what it takes to create something of that scope and do it well.

With all that said, I do believe this story will have a happy ending. I was adamant about finishing the year strong despite my lackluster effort early on. I wrote more in the month of December than I did during the eleven months prior. I’m proud of my desire to bounce back and I’m confident that 2017 is the year I finish my first book.

The hiring process. As I mentioned above, hiring a great executive assistant was one of the highlights of my year. Unfortunately, the way I handled the hiring process left a lot of room for improvement. When I put out the call for applications, I was stunned by the response. In total, 911 people applied. Given that this was going to be my first full-time hire, I was really worried about making the best choice. I read each application myself and it took months for me to finish them all. Hiring was basically my full-time job, which is yet another reason why I did very little book writing during that time. 1

While I did respond to every candidate, it took me far too long to do so. Applicants were left wondering about their status for weeks. In total, hiring my first full-time employee took nearly four months. The end result was wonderful, but the process was messy. I can definitely do better next time.

Don’t celebrate my wins and share my failures.

3. What am I working toward?

Be a finisher. I’m not in this to be average and I’m not working to get halfway done with something. Beginner’s are many. Finisher’s are few.

Transitioning to deep work.

This past year has been a strange one for me in a variety of ways. Compared to recent years, it seems like 2016 came in a more all-or-nothing flavor for me. I had some big successes, but I also had some hardships and major failures—not a whole lot of so-so, run-of-the-mill performances. Boom or bust. So it goes, I guess.

Finally, thank you for reading. I don’t have all the answers, but I’m happy to share what I learn with you along the way.2

The Annual Review Archives

This is a complete list of Annual Reviews I have written.

My 2016 Annual Review My 2015 Annual Review My 2014 Annual Review My 2013 Annual Review

Footnotes

The number of applications still seems silly to me. I’m completely stunned by how many people not only read this site, but are truly interested in being part of the journey. Thank you to everyone who applied.

Thanks to Chris Guillebeau for inspiring me to do an Annual Review each year.

December 19, 2016

The 10 Best Articles of 2016

Hi friends! Today I would like to continue a tradition I have conducted each year JamesClear.com has been around. I’d like to share my 10 best articles of the year.

Before we dive into the list for 2016, I’ll point out that you are welcome to browse the 10 Best Articles of 2013, 2014, and 2015 as well.

I always find it interesting to see which articles resonated most with you all (and which ones flopped), and I hope you find this list helpful too.

The 10 Best Articles of 2016

1. Make Your Life Better by Saying Thank You in These 7 Situations

This post explains the power of a simple phrase: thank you. It also discusses a variety of situations when we should say thank you, but usually say something else instead.

2. The Evolution of Anxiety: Why We Worry and What to Do About It

This article discusses how our evolutionary instincts clash with the modern world and what this means for anxiety, stress, and worry. I’m proud of this one because of how I was able to blend science, practical application, and fun hand-drawn images. My best articles tend to be ones that are educational, entertaining, and useful.

3. The Akrasia Effect: Why We Don’t Follow Through on What We Set Out to Do and What to Do About It

This article shares the story of the famous author, Victor Hugo, and the totally-strange-but-somehow-effective strategy he used to overcome his chronic procrastination. Throughout the post, I weave in some interesting scientific insights about why we procrastinate and what we can do about it.

4. The Downside of Work-Life Balance

A few years ago, I came across this interesting concept about work-life balance called The Four Burners Theory. In this article, I finally got around to writing about it, and I lay out three different approaches I have used for dealing with the fundamental tradeoffs of life and work.

5. Motivation is Overvalued. Environment Often Matters More.

The power of the environment is one of my favorite themes when it comes to discussing our habits and behavior. This article examines how environment has shaped the course of humanity over the centuries and then dives into the practical application of these ideas for our modern world.

6. The 3 Stages of Failure in Life and Work (And How to Fix Them)

For one of my longest and most comprehensive articles of the year, I decided to discuss the 3 stages of failure. The examples I use primarily draw from the business world, but many of the lessons hold true for life as well. In addition to describing the symptoms, I try to offer practical strategies for fixing each of the 3 stages of failure.

7. Motivation: The Scientific Guide on How to Get and Stay Motivated

Throughout the second half of the year, I focused on creating a variety of comprehensive guides on various topics related to habits and human performance. One of the best ones was this guide on motivation. In fact, if you search “motivation” in Google, this article will likely come up #1 or #2.

8. The Science of Sleep: A Brief Guide on How to Sleep Better Every Night

Another one of my comprehensive guides dived into the science of sleep. In this 4,600-word beast, you will not only find out how much sleep you actually need and how sleep works, but also proven ideas for how to get better sleep each night.

9. Healthy Eating: The Beginner’s Guide on How to Eat Healthy and Stick to It

This guide takes a different stance on healthy eating. Rather than focusing on telling you what to eat or how much to eat, this guide explains why we eat the way we do and what to do about it. It focuses on behaviors like why we tend to eat so much junk food and why we overeat so frequently, and then lays out simple strategies for overcoming these unhealthy habits.

10. The Proven Path to Doing Unique and Meaningful Work

Finally, we have an article that shares some brilliant advice that comes from a Finnish photographer named Arno Rafael Minkkinen. In this article, I explain the philosophy Minkkinen used to make it through the difficult portions of his career and ultimately produce unique and meaningful work. No matter what profession you are in, his advice is valuable.

My Best Articles of All-Time

Looking for more good articles to read? Check out the complete archive of the best articles I’ve written.

Thanks for reading!

August 30, 2016

The Shadow Side of Greatness

Pablo Picasso. He is one of the most famous artists of the 20th century and a household name even among people who, like myself, consider themselves to be complete novices in the art world.

I recently went to a Picasso exhibition. What impressed me the most was not any individual piece of art, but rather his remarkably prolific output. Researchers have catalogued 26,075 pieces of art created by Picasso and some people believe the total number is closer to 50,000.

When I discovered that Picasso lived to be 91 years old, I decided to do the math. Picasso lived for a total of 33,403 days. With 26,075 published works, that means Picasso averaged 1 new piece of artwork every day of his life from age 20 until his death at age 91. He created something new, every day, for 71 years.

This unfathomable output not only played a large role in Picasso’s international fame, but also enabled him to amass a huge net worth of approximately $500 million by the time of his death in 1973. His work became so famous and so numerous that, according to the Art Loss Register, Picasso is the most stolen artist in history with over 550 works currently missing.

What made Picasso great was not just how much art he produced, but also how he produced it. He co-founded the movement of Cubism and created the style of collage. He was the artist his contemporaries copied. Any discussion of the most well-known artists in history would have to include his name.

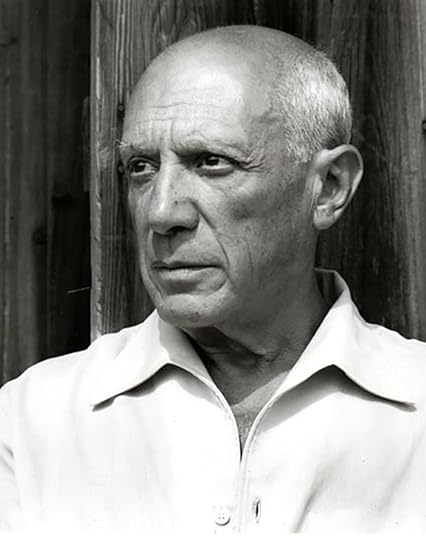

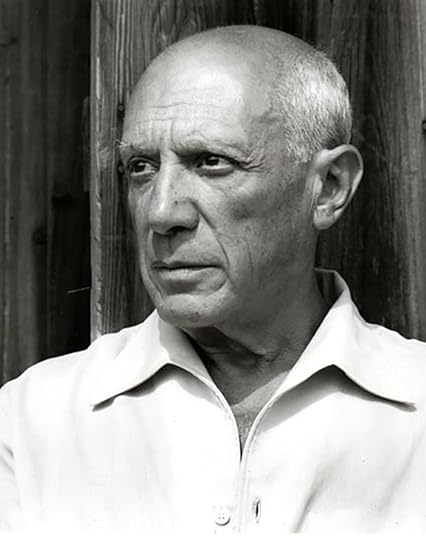

Pablo Picasso as photographed by Gilles Ehrmann in 1952.

Pablo Picasso as photographed by Gilles Ehrmann in 1952.Falling in Love With Picasso

Falling in love with Picasso was a terrible thing to do.

His first marriage was to a woman named Olga Khokhlova and they had one child together. The two separated after she discovered that Picasso was having an affair with a seventeen-year-old girl named Marie-Therese Walter. He was 45 years old at the time.

Picasso fathered a child with Walter, but moved on to other lovers a few years later. He began dating an art student named Francoise Gilot in 1944. She was 23 years old. Picasso had just turned 63 at the time.

Gilot and Picasso had two children together, but their relationship ended when Picasso began yet another affair, this time with a woman who was 43 years younger than him. After they separated, Gilot published a book called Life with Picasso, which revealed his long list of sexual flings and sold over one million copies. Out of revenge, Picasso refused to see their two children ever again.

Basically, Picasso’s romantic life was a revolving door of affairs and infidelity. In the words of our guide at the Picasso exhibit, “There were always many others.” There must have been something intoxicating about Picasso because after his death, not one, but two of his lovers committed suicide due to their grief. 1

The Shadow Side

Many of the qualities that make people great have shadow sides as well. Picasso’s singular focus on art meant that everything else in life had to take a back seat, including his relationships and his children.

Most humans have a primary relationship with their lover and maintain a variety of hobbies and interests during different periods. Picasso was the reverse. His primary relationship was with his art, while his lovers were like hobbies and passing interests, things he experimented with for a period here and there.

Some scholars believe Picasso’s many relationships were essential to the progression of his art. According to art critic Arthur Danto, “Picasso invented a new style each time he fell in love with a new woman.” 2

This was the shadow side of his strength as an artist. The qualities that made Picasso one of the greatest artists of all-time may very well have made him a terrible life partner too. They are like two sides of the same coin. You couldn’t have one without the other. 3

Shadows Appear in All Fields

I don’t mean to pick on Picasso here. The idea that strengths have tradeoffs, especially extreme versions of strengths, holds true in nearly every field.

For example, consider Floyd Mayweather Jr. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest boxers of all-time. His career record is 49-0. He has earned more than $1.3 billion over the course of his career.

He also has serious anger management issues. In 2002, he was charged with two counts of domestic violence. In 2004, two counts of misdemeanor battery against different women. In 2005, another charge of misdemeanor battery. In 2010, yet another misdemeanor battery charge. Not to mention, there have been a number of reported charges that were later dropped.

The qualities that make him a once-in-a-lifetime boxer—his unbridled anger and lack of impulse control—also lead him to be violent in normal situations. This combination makes him unbeatable in the ring and unbearable in the rest of life.

Every Strength Has a Tradeoff

Now, you might be thinking, “Well, you don’t have to cheat on your spouse to produce great art or beat up others to become a good boxer. Those are two different things.”

You’re right. I’m using extreme examples here to make the point, however, it remains true that every strength has a shadow side. Some shadows are darker than others, but all paths to success have a cost.

Maybe you’re a doctor or a nurse who has learned how to remove yourself from the emotion of death. This quality that allows you to do your job well when patients die each day, but also reduces the empathy and connection you feel with friends and family.

Maybe you’re a scientist who holds themselves to the highest standards. This perfectionism makes you excellent in the lab, but also leads you to show tough love to your children and they grow up believing nothing they do is ever good enough.

Maybe you’re a smart and enthusiastic friend who wants to help others by always providing value. You’re just trying to be helpful, but you end up providing too much value. Your friends wish you would just listen to their problems and not feel the need to make your mark on everything.

There are an infinite number of ways this can play out, but one singular punchline: every strength comes with tradeoffs.

Is Success Worth the Shadow Side?

Success is complicated. We love to praise people for becoming famous, for winning championships, and for making tons of money, but we rarely discuss the costs of success.

Did the beauty of Picasso’s art add more joy to the world than the pain he caused through a series of broken relationships? It’s easy for you and me to believe his contribution was net positive because we didn’t have to bear the pain. His ex-wives and mistresses might feel differently—especially the two who committed suicide.

The fact that you cannot escape the downsides of your strengths brings us to an interesting decision point. People often talk about the success they aspire to in life, but as author Mark Manson writes in his popular book, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, the most important question to ask yourself is not, “What kind of success do I want?”, but rather, “What kind of pain do I want?”

Do you want the shadow that comes with the success? Do you want the baggage that comes with the bounty? What kind of pain are you willing to bear in the name of achieving what you want to achieve? Answering this question honestly often leads to more insight about what you really care about than thinking of your dreams and aspirations.

It is easy to want financial independence or the approval of your boss or to look good in front of the mirror. Everybody wants those things. But do you want the shadow side that goes with it? Do you want to spend two extra hours at work each day rather than with your kids? Do you want to put your career ahead of your marriage? Do you want to wake up early and go to the gym when you feel like sleeping in? Different people have different answers and you’ll have to decide what is best for you, but pretending that the shadow isn’t there is not a good strategy.

Bigger Success, Longer Shadow

Success in one area is often tied to failure in another area, especially at the extreme end of performance. The more extreme the greatness, the longer the shadow it casts.

To phrase it differently, the more one dimensional your focus, the more other areas of life suffer. It’s the four burners theory in action. The more you turn up one burner, the more you risk others burning out.

The things that make people great in one area often make them miserable in others.

Footnotes

Picasso literally had multiple people killing themselves over losing him. When I was dating, I could barely get someone to text me back.

“Picasso and the Portrait” by Arthur Danto. The Nation 263 (6): 31–35. September 2, 1996.

I also think it is possible, and I’m just theorizing here, that Picasso’s brain was neurologically wired to be more curious than the average person. This curiosity led him to experiment with new forms of art and to produce vibrant work, but also constantly drew him toward new women.

The Shadow Side of Greatness: When Success Leads to Failure

Pablo Picasso. He is one of the most famous artists of the 20th century and a household name even among people who, like myself, consider themselves to be complete novices in the art world.

I recently went to a Picasso exhibition. What impressed me the most was not any individual piece of art, but rather his remarkably prolific output. Researchers have catalogued 26,075 pieces of art created by Picasso and some people believe the total number is closer to 50,000.

When I discovered that Picasso lived to be 91 years old, I decided to do the math. Picasso lived for a total of 33,403 days. With 26,075 published works, that means Picasso averaged 1 new piece of artwork every day of his life from age 20 until his death at age 91. He created something new, every day, for 71 years.

This unfathomable output not only played a large role in Picasso’s international fame, but also enabled him to amass a huge net worth of approximately $500 million by the time of his death in 1973. His work became so famous and so numerous that, according to the Art Loss Register, Picasso is the most stolen artist in history with over 550 works currently missing.

What made Picasso great was not just how much art he produced, but also how he produced it. He co-founded the movement of Cubism and created the style of collage. He was the artist his contemporaries copied. Any discussion of the most well-known artists in history would have to include his name.

Pablo Picasso as photographed by Gilles Ehrmann in 1952.

Pablo Picasso as photographed by Gilles Ehrmann in 1952.Falling in Love With Picasso

Falling in love with Picasso was a terrible thing to do.

His first marriage was to a woman named Olga Khokhlova and they had one child together. The two separated after she discovered that Picasso was having an affair with a seventeen-year-old girl named Marie-Therese Walter. He was 45 years old at the time.

Picasso fathered a child with Walter, but moved on to other lovers a few years later. He began dating an art student named Francoise Gilot in 1944. She was 23 years old. Picasso had just turned 63 at the time.

Gilot and Picasso had two children together, but their relationship ended when Picasso began yet another affair, this time with a woman who was 43 years younger than him. After they separated, Gilot published a book called Life with Picasso, which revealed his long list of sexual flings and sold over one million copies. Out of revenge, Picasso refused to see their two children ever again.

Basically, Picasso’s romantic life was a revolving door of affairs and infidelity. In the words of our guide at the Picasso exhibit, “There were always many others.” There must have been something intoxicating about Picasso because after his death, not one, but two of his lovers committed suicide due to their grief. 1

The Shadow Side

Many of the qualities that make people great have shadow sides as well. Picasso’s singular focus on art meant that everything else in life had to take a back seat, including his relationships and his children.

Most humans have a primary relationship with their lover and maintain a variety of hobbies and interests during different periods. Picasso was the reverse. His primary relationship was with his art, while his lovers were like hobbies and passing interests, things he experimented with for a period here and there.

Some scholars believe Picasso’s many relationships were essential to the progression of his art. According to art critic Arthur Danto, “Picasso invented a new style each time he fell in love with a new woman.” 2

This was the shadow side of his strength as an artist. The qualities that made Picasso one of the greatest artists of all-time may very well have made him a terrible life partner too. They are like two sides of the same coin. You couldn’t have one without the other. 3

Shadows Appear in All Fields

I don’t mean to pick on Picasso here. The idea that strengths have tradeoffs, especially extreme versions of strengths, holds true in nearly every field.

For example, consider Floyd Mayweather Jr. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest boxers of all-time. His career record is 49-0. He has earned more than $1.3 billion over the course of his career.

He also has serious anger management issues. In 2002, he was charged with two counts of domestic violence. In 2004, two counts of misdemeanor battery against different women. In 2005, another charge of misdemeanor battery. In 2010, yet another misdemeanor battery charge. Not to mention, there have been a number of reported charges that were later dropped.

The qualities that make him a once-in-a-lifetime boxer—his unbridled anger and lack of impulse control—also lead him to be violent in normal situations. This combination makes him unbeatable in the ring and unbearable in the rest of life.

Every Strength Has a Tradeoff

Now, you might be thinking, “Well, you don’t have to cheat on your spouse to produce great art or beat up others to become a good boxer. Those are two different things.”

You’re right. I’m using extreme examples here to make the point, however, it remains true that every strength has a shadow side. Some shadows are darker than others, but all paths to success have a cost.

Maybe you’re a doctor or a nurse who has learned how to remove yourself from the emotion of death. This quality that allows you to do your job well when patients die each day, but also reduces the empathy and connection you feel with friends and family.

Maybe you’re a scientist who holds themselves to the highest standards. This perfectionism makes you excellent in the lab, but also leads you to show tough love to your children and they grow up believing nothing they do is ever good enough.

Maybe you’re a smart and enthusiastic friend who wants to help others by always providing value. You’re just trying to be helpful, but you end up providing too much value. Your friends wish you would just listen to their problems and not feel the need to make your mark on everything.

There are an infinite number of ways this can play out, but one singular punchline: every strength comes with tradeoffs.

Is Success Worth the Shadow Side?

Success is complicated. We love to praise people for becoming famous, for winning championships, and for making tons of money, but we rarely discuss the costs of success.

Did the beauty of Picasso’s art add more joy to the world than the pain he caused through a series of broken relationships? It’s easy for you and me to believe his contribution was net positive because we didn’t have to bear the pain. His ex-wives and mistresses might feel differently—especially the two who committed suicide.

The fact that you cannot escape the downsides of your strengths brings us to an interesting decision point. People often talk about the success they aspire to in life, but as author Mark Manson writes, the most important question to ask yourself is not, “What kind of success do I want?”, but rather, “What kind of pain do I want?”

Do you want to shadow that comes with the success? Do you want the baggage that comes with the bounty? What kind of pain are you willing to bear in the name of achieving what you want to achieve? Answering this question honestly often leads to more insight about what you really care about than thinking of your dreams and aspirations.

It is easy to want financial independence or the approval of your boss or to look good in front of the mirror. Everybody wants those things. But do you want the shadow side that goes with it? Do you want to spend two extra hours at work each day rather than with your kids? Do you want to put your career ahead of your marriage? Do you want to wake up early and go to the gym when you feel like sleeping in? Different people have different answers and you’ll have to decide what is best for you, but pretending that the shadow isn’t there is not a good strategy.

Bigger Success, Longer Shadow

Success in one area is often tied to failure in another area, especially at the extreme end of performance. The more extreme the greatness, the longer the shadow it casts.

To phrase it differently, the more one dimensional your focus, the more other areas of life suffer. It’s the four burners theory in action. The more you turn up one burner, the more you risk others burning out.

The things that make people great in one area often make them miserable in others.

Footnotes

Picasso literally had multiple people killing themselves over losing him. When I was dating, I could barely get someone to text me back.

“Picasso and the Portrait” by Arthur Danto. The Nation 263 (6): 31–35. September 2, 1996.

I also think it is possible, and I’m just theorizing here, that Picasso’s brain was neurologically wired to be more curious than the average person. This curiosity led him to experiment with new forms of art and to produce vibrant work, but also constantly drew him toward new women.

August 9, 2016

How Innovative Ideas Arise

In 2010, Thomas Thwaites decided he wanted to build a toaster from scratch. He walked into a shop, purchased the cheapest toaster he could find, and promptly went home and broke it down piece by piece.

Thwaites had assumed the toaster would be a relatively simple machine. By the time he was finished deconstructing it, however, there were more than 400 components laid out on his floor. The toaster contained over 100 different materials with three of the primary ones being plastic, nickel, and steel.

He decided to create the steel components first. After discovering that iron ore was required to make steel, Thwaites called up an iron mine in his region and asked if they would let him use some for the project.

Surprisingly, they agreed.

The Toaster Project

The victory was short-lived.

When it came time to create the plastic case for his toaster, Thwaites realized he would need crude oil to make the plastic. This time, he called up BP and asked if they would fly him out to an oil rig and lend him some oil for the project. They immediately refused. It seems oil companies aren’t nearly as generous as iron mines.

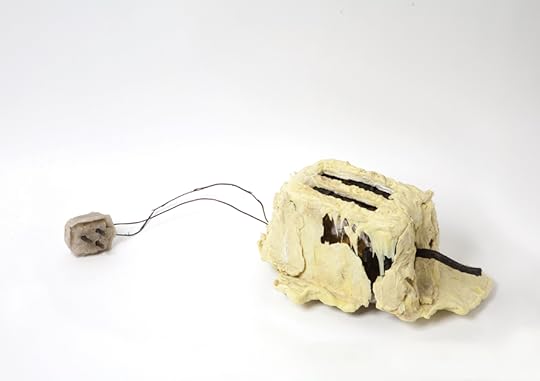

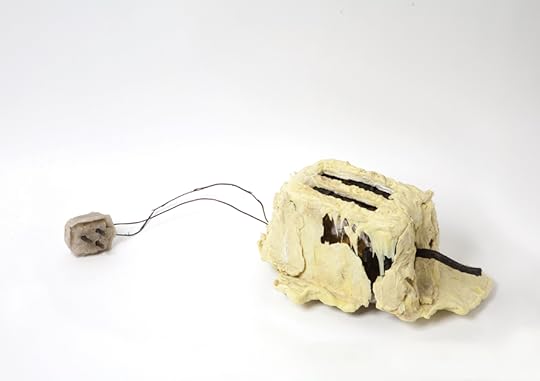

Thwaites had to settle for collecting plastic scraps and melting them into the shape of his toaster case. This is not as easy as it sounds. The homemade toaster ended up looking more like a melted cake than a kitchen appliance.

This pattern continued for the entire span of The Toaster Project. It was nearly impossible to move forward without the help of some previous process. To create the nickel components, for example, he had to resort to melting old coins. He would later say, “I realized that if you started absolutely from scratch you could easily spend your life making a toaster.” 1

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)Don’t Start From Scratch

Starting from scratch is usually a bad idea.

Too often, we assume innovative ideas and meaningful changes require a blank slate. When business projects fail, we say things like, “Let’s go back to the drawing board.” When we consider the habits we would like to change, we think, “I just need a fresh start.” However, creative progress is rarely the result of throwing out all previous ideas and completely re-imagining of the world.

Consider an example from nature:

Some experts believe the feathers of birds evolved from reptilian scales. Through the forces of evolution, scales gradually became small feathers, which were used for warmth and insulation at first. Eventually, these small fluffs developed into larger feathers capable of flight.

There wasn’t a magical moment when the animal kingdom said, “Let’s start from scratch and create an animal that can fly.” The development of flying birds was a gradual process of iterating and expanding upon ideas that already worked. 2

The process of human flight followed a similar path. We typically credit Orville and Wilbur Wright as the inventors of modern flight. However, we seldom discuss the aviation pioneers who preceded them like Otto Lilienthal, Samuel Langley, and Octave Chanute. The Wright brothers learned from and built upon the work of these people during their quest to create the world’s first flying machine.

The most creative innovations are often new combinations of old ideas. Innovative thinkers don’t create, they connect. Furthermore, the most effective way to make progress is usually by making 1 percent improvements to what already works rather than breaking down the whole system and starting over.

Iterate, Don’t Originate

The Toaster Project is an example of how we often fail to notice the complexity of our modern world. When you buy a toaster, you don’t think about everything that has to happen before it appears in the store. You aren’t aware of the iron being carved out of the mountain or the oil being drawn up from the earth. 3

We are mostly blind to the remarkable interconnectedness of things. This is important to understand because in a complex world it is hard to see which forces are working for you as well as which forces are working against you. Similar to buying a toaster, we tend to focus on the final product and fail to recognize the many processes leading up to it.

When you are dealing with a complex problem, it is usually better to build upon what already works. Any idea that is currently working has passed a lot of tests. Old ideas are a secret weapon because they have already managed to survive in a complex world.

Iterate, don’t originate.

Read Next

The Domino Effect: How to Create a Chain Reaction of Good Habits

The Best Art and Creativity Books

Transform Your Habits: The Science of How to Stick to Good Habits and Break Bad Ones

Footnotes

Information for this story was collected from Thomas Thwaites’ personal website, The Toaster Project, and from his TED Talk titled, “How I built a toaster from scratch.”

If you’re curious, I believe the closest living reptile ancestor to birds is the crocodile. You sort of imagine how reptile scales interlink and lay over one another in a similar fashion as bird feathers.

I first read about The Toaster Project in Adapt by Tim Harford. He also discusses the interconnectedness of our modern world. It’s a good read if you’re interested in the idea of applying the concept of evolution to business and life. I recommend it.

Don’t Start From Scratch: How Innovative Ideas Arise

In 2010, Thomas Thwaites decided he wanted to build a toaster from scratch. He walked into a shop, purchased the cheapest toaster he could find, and promptly went home and broke it down piece by piece.

Thwaites had assumed the toaster would be a relatively simple machine. By the time he was finished deconstructing it, however, there were more than 400 components laid out on his floor. The toaster contained over 100 different materials with three of the primary ones being plastic, nickel, and steel.

He decided to create the steel components first. After discovering that iron ore was required to make steel, Thwaites called up an iron mine in his region and asked if they would let him use some for the project.

Surprisingly, they agreed.

The Toaster Project

The victory was short-lived.

When it came time to create the plastic case for his toaster, Thwaites realized he would need crude oil to make the plastic. This time, he called up BP and asked if they would fly him out to an oil rig and lend him some oil for the project. They immediately refused. It seems oil companies aren’t nearly as generous as iron mines.

Thwaites had to settle for collecting plastic scraps and melting them into the shape of his toaster case. This is not as easy as it sounds. The homemade toaster ended up looking more like a melted cake than a kitchen appliance.

This pattern continued for the entire span of The Toaster Project. It was nearly impossible to move forward without the help of some previous process. To create the nickel components, for example, he had to resort to melting old coins. He would later say, “I realized that if you started absolutely from scratch you could easily spend your life making a toaster.” 1

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)Don’t Start From Scratch

Starting from scratch is usually a bad idea.

Too often, we assume innovative ideas and meaningful changes require a blank slate. When business projects fail, we say things like, “Let’s go back to the drawing board.” When we consider the habits we would like to change, we think, “I just need a fresh start.” However, creative progress is rarely the result of throwing out all previous ideas and completely re-imagining of the world.

Consider an example from nature:

Some experts believe the feathers of birds evolved from reptilian scales. Through the forces of evolution, scales gradually became small feathers, which were used for warmth and insulation at first. Eventually, these small fluffs developed into larger feathers capable of flight.

There wasn’t a magical moment when the animal kingdom said, “Let’s start from scratch and create an animal that can fly.” The development of flying birds was a gradual process of iterating and expanding upon ideas that already worked. 2

The process of human flight followed a similar path. We typically credit Orville and Wilbur Wright as the inventors of modern flight. However, we seldom discuss the aviation pioneers who preceded them like Otto Lilienthal, Samuel Langley, and Octave Chanute. The Wright brothers learned from and built upon the work of these people during their quest to create the world’s first flying machine.

The most creative innovations are often new combinations of old ideas. Innovative thinkers don’t create, they connect. Furthermore, the most effective way to make progress is usually by making 1 percent improvements to what already works rather than breaking down the whole system and starting over.

Iterate, Don’t Originate

The Toaster Project is an example of how we often fail to notice the complexity of our modern world. When you buy a toaster, you don’t think about everything that has to happen before it appears in the store. You aren’t aware of the iron being carved out of the mountain or the oil being drawn up from the earth. 3

We are mostly blind to the remarkable interconnectedness of things. This is important to understand because in a complex world it is hard to see which forces are working for you as well as which forces are working against you. Similar to buying a toaster, we tend to focus on the final product and fail to recognize the many processes leading up to it.

When you are dealing with a complex problem, it is usually better to build upon what already works. Any idea that is currently working has passed a lot of tests. Old ideas are a secret weapon because they have already managed to survive in a complex world.

Iterate, don’t originate.

Footnotes

Information for this story was collected from Thomas Thwaites’ personal website, The Toaster Project, and from his TED Talk titled, “How I built a toaster from scratch.”

If you’re curious, I believe the closest living reptile ancestor to birds is the crocodile. You sort of imagine how reptile scales interlink and lay over one another in a similar fashion as bird feathers.

I first read about The Toaster Project in Adapt by Tim Harford. He also discusses the interconnectedness of our modern world. It’s a good read if you’re interested in the idea of applying the concept of evolution to business and life. I recommend it.

July 25, 2016

For a More Creative Brain, Follow These 5 Steps

Nearly all great ideas follow a similar creative process and this articles explains how this process works. Understanding this is important because creative thinking is one of the most useful skills you can possess. Nearly every problem you face in work and in life can benefit from creative solutions, lateral thinking, and innovative ideas.

Anyone can learn to be creative by using these five steps. That’s not to say being creative is easy. Uncovering your creative genius requires courage and tons of practice. However, this five-step approach should help demystify the creative process and illuminate the path to more innovative thinking.

To explain how this process works, let me tell you a short story.

A Problem in Need of a Creative Solution

In the 1870s, newspapers and printers faced a very specific and very costly problem. Photography was a new and exciting medium at the time. Readers wanted to see more pictures, but nobody could figure out how to print images quickly and cheaply.

For example, if a newspaper wanted to print an image in the 1870s, they had to commission an engraver to etch a copy of the photograph onto a steel plate by hand. These plates were used to press the image onto the page, but they often broke after just a few uses. This process of photoengraving, you can imagine, was remarkably time consuming and expensive.

The man who invented a solution to this problem was named Frederic Eugene Ives. He went on to become a trailblazer in the field of photography and held over 70 patents by the end of his career. His story of creativity and innovation, which I will share now, is a useful case study for understanding the 5 key steps of the creative process.

A Flash of Insight

Ives got his start as a printer’s apprentice in Ithaca, New York. After two years of learning the ins and outs of the printing process, he began managing the photographic laboratory at nearby Cornell University. He spent the rest of the decade experimenting with new photography techniques and learning about cameras, printers, and optics.

In 1881, Ives had a flash of insight regarding a better printing technique.

“While operating my photostereotype process in Ithaca, I studied the problem of halftone process,” Ives said. “I went to bed one night in a state of brain fog over the problem, and the instant I woke in the morning saw before me, apparently projected on the ceiling, the completely worked out process and equipment in operation.” 1

Ives quickly translated his vision into reality and patented his printing approach in 1881. He spent the remainder of the decade improving upon it. By 1885, he had developed a simplified process that delivered even better results. The Ives Process, as it came to be known, reduced the cost of printing images by 15x and remained the standard printing technique for the next 80 years.

Alright, now let’s discuss what lessons we can learn from Ives about the creative process.

The printing process developed by Frederic Eugene Ives used a method called “halftone printing” to break a photograph down into a series of tiny dots. The image looks like a collection of dots up close, but when viewed from a normal distance the dots blend together to create a picture with varying shades of gray. (Source: Unknown.)

The printing process developed by Frederic Eugene Ives used a method called “halftone printing” to break a photograph down into a series of tiny dots. The image looks like a collection of dots up close, but when viewed from a normal distance the dots blend together to create a picture with varying shades of gray. (Source: Unknown.)The 5 Stages of the Creative Process

In 1940, an advertising executive named James Webb Young published a short guide titled, A Technique for Producing Ideas. In this guide, he made a simple, but profound statement about generating creative ideas.

According to Young, innovative ideas happen when you develop new combinations of old elements. In other words, creative thinking is not about generating something new from a blank slate, but rather about taking what is already present and combining those bits and pieces in a way that has not been done previously.

Most important, the ability to generate new combinations hinges upon your ability to see the relationships between concepts. If you can form a new link between two old ideas, you have done something creative.

Young believed this process of creative connection always occurred in five steps.

Gather new material. At first, you learn. During this stage you focus on 1) learning specific material directly related to your task and 2) learning general material by becoming fascinated with a wide range of concepts.

Thoroughly work over the materials in your mind. During this stage, you examine what you have learned by looking at the facts from different angles and experimenting with fitting various ideas together.

Step away from the problem. Next, you put the problem completely out of your mind and go do something else that excites you and energizes you.

Let your idea return to you. At some point, but only after you have stopped thinking about it, your idea will come back to you with a flash of insight and renewed energy.

Shape and develop your idea based on feedback. For any idea to succeed, you must release it out into the world, submit it to criticism, and adapt it as needed.

The Idea in Practice

The creative process used by Frederic Eugene Ives offers a perfect example of these five steps in action.

First, Ives gathered new material. He spent two years working as a printer’s apprentice and then four years running the photographic laboratory at Cornell University. These experiences gave him a lot of material to draw upon and make associations between photography and printing.

Second, Ives began to mentally work over everything he learned. By 1878, Ives was spending nearly all of his time experimenting with new techniques. He was constantly tinkering and experimenting with different ways of putting ideas together.

Third, Ives stepped away from the problem. In this case, he went to sleep for a few hours before his flash of insight. Letting creative challenges sit for longer periods of time can work as well. Regardless of how long you step away, you need to do something that interests you and takes your mind off of the problem.

Fourth, his idea returned to him. Ives awoke with the solution to his problem laid out before him. (On a personal note, I often find creative ideas hit me just as I am lying down for sleep. Once I give my brain permission to stop working for the day, the solution appears easily.)

Finally, Ives continued to revise his idea for years. In fact, he improved so many aspects of the process he filed a second patent. This is a critical point and is often overlooked. It can be easy to fall in love with the initial version of your idea, but great ideas always evolve.

The Creative Process in Short

“An idea is a feat of association, and the height of it is a good metaphor.”

—Robert Frost

The creative process is the act of making new connections between old ideas. Thus, we can say creative thinking is the task of recognizing relationships between concepts.

One way to approach creative challenges is by following the five-step process of 1) gathering material, 2) intensely working over the material in your mind, 3) stepping away from the problem, 4) allowing the idea to come back to you naturally, and 5) testing your idea in the real world and adjusting it based on feedback.

Being creative isn’t about being the first (or only) person to think of an idea. More often, creativity is about connecting ideas.

Footnotes

This quote is excerpted from A Technique for Producing Ideas by James Webb Young. Page 21.

July 19, 2016

How to Create a Chain Reaction of Good Habits

Human behaviors are often tied to one another.

For example, consider the case of a woman named Jennifer Lee Dukes. For two and a half decades during her adult life, starting when she left for college and extending into her 40s, Dukes never made her bed except for when her mother or guests dropped by the house.

At some point, she decided to give it another try and managed to make her bed four days in a row—a seemingly trivial feat. However, on the morning of that fourth day, when she finished making the bed, she also picked up a sock and folded a few clothes lying around the bedroom. Next, she found herself in the kitchen, pulling the dirty dishes out of the sink and loading them into the dishwasher, then reorganizing the Tupperware in a cupboard and placing an ornamental pig on the counter as a centerpiece.

She later explained, “My act of bed-making had set off a chain of small household tasks… I felt like a grown-up—a happy, legit grown-up with a made bed, a clean sink, one decluttered cupboard, and a pig on the counter. I felt like a woman who had miraculously pulled herself up from the energy-sucking Bermuda Triangle of Household Chaos.” 1

Jennifer Lee Dukes was experiencing the Domino Effect.

The Domino Effect

The Domino Effect states that when you make a change to one behavior it will activate a chain reaction and cause a shift in related behaviors as well. 2

For example, a 2012 study from researchers at Northwestern University found that when people decreased their amount of sedentary leisure time each day, they also reduced their daily fat intake. The participants were never specifically told to eat less fat, but their nutrition habits improved as a natural side effect because they spent less time on the couch watching television and mindlessly eating. One habit led to another, one domino knocked down the next. 3

You may notice similar patterns in your own life. As a personal example, if I stick with my habit of going to the gym, then I naturally find myself more focused at work and sleeping more soundly at night even though I never made a plan to specifically improve either behavior.

The Domino Effect holds for negative habits as well. You may find that the habit of checking your phone leads to the habit of clicking social media notifications which leads to the habit of browsing social media mindlessly which leads to another 20 minutes of procrastination.

In the words of Stanford professor BJ Fogg, “You can never change just one behavior. Our behaviors are interconnected, so when you change one behavior, other behaviors also shift.” 4

Inside the Domino Effect

As best I can tell, the Domino Effect occurs for two reasons.

First, many of the habits and routines that make up our daily lives are related to one another. There is an astounding interconnectedness between the systems of life and human behavior is no exception. The inherent relatedness of things is a core reason why choices in one area of life can lead to surprising results in other areas, regardless of the plans you make.

Second, the Domino Effect capitalizes on one of the core principles of human behavior: commitment and consistency. This phenomenon is explained in the classic book on human behavior, Influence by Robert Cialdini. The core idea is that if people commit to an idea or goal, even in a very small way, they are more likely to honor that commitment because they now see that idea or goal as being aligned with their self-image.

Returning to the story from the beginning of this article, once Jennifer Lee Dukes began making her bed each day she was making a small commitment to the idea of, “I am the type of person who maintains a clean and organized home.” After a few days, she began to commit to this new self-image in other areas of her home.

This is an interesting byproduct of the Domino Effect. It not only creates a cascade of new behaviors, but often a shift in personal beliefs as well. As each tiny domino falls, you start believing new things about yourself and building identity-based habits.

The Rules of the Domino Effect

The Domino Effect is not merely a phenomenon that happens to you, but something you can create. It is within your power to spark a chain reaction of good habits by building new behaviors that naturally lead to the next successful action.

There are three keys to making this work in real life. Here are the three rules of the Domino Effect:

Start with the thing you are most motivated to do. Start with a small behavior and do it consistently. This will not only feel satisfying, but also open your eyes to the type of person you can become. It does not matter which domino falls first, as long as one falls.

Maintain momentum and immediately move to the next task you are motivated to finish. Let the momentum of finishing one task carry you directly into the next behavior. With each repetition, you will become more committed to your new self-image.

When in doubt, break things down into smaller chunks. As you try new habits, focus on keeping them small and manageable. The Domino Effect is about progress, not results. Simply maintain the momentum. Let the process repeat as one domino automatically knocks down the next.

When one habit fails to lead to the next behavior, it is often because the behavior does not adhere to these three rules. There are many different paths to getting dominoes to fall. Focus on the behavior you are excited about and let it cascade throughout your life.

Read Next

Transform Your Habits: The Science of How to Stick to Good Habits and Break Bad Ones

The Best Psychology Books to Read

The Scientific Argument for Mastering One Thing at a Time

Footnotes

“Want to Change the World? Start by Making Your Bed” by Jennifer Lee Dukes

The phrase, the Domino Effect, comes from the common game people play by setting up a long line of dominoes, gently tapping the first one, and watching as a delightful chain reason proceeds to knock down each domino in the chain. I thought up this particular use of the phrase, but I’ve seen others say similar things like “snowball effect” or “chain reaction.”

Multiple Behavior Change in Diet and Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial Using Mobile Technology by Bonnie Spring, Kristin Schneider, H.G. McFadden, Jocelyn Vaughn, Andrea T. Kozak, Malaina Smith, Arlen C. Moller, Leonard H. Epstein, Andrew DeMott, Donald Hedeker, Juned Siddique, and Donald M. Lloyd-Jones. Archives of Intern Medicine (2012).

Quote from “BJ’s note” posted on September 21, 2015. It is worth noting that BJ has some fantastic ideas on behavior change on his site, many of which have influenced my thoughts including his idea that “behaviors travel in packs,” which is similar to the core argument of Domino Effect.

The Domino Effect: How to Create a Chain Reaction of Good Habits

Human behaviors are often tied to one another.

For example, consider the case of a woman named Jennifer Lee Dukes. For two and a half decades during her adult life, starting when she left for college and extending into her 40s, Dukes never made her bed except for when her mother or guests dropped by the house.

At some point, she decided to give it another try and managed to make her bed four days in a row—a seemingly trivial feat. However, on the morning of that fourth day, when she finished making the bed, she also picked up a sock and folded a few clothes lying around the bedroom. Next, she found herself in the kitchen, pulling the dirty dishes out of the sink and loading them into the dishwasher, then reorganizing the Tupperware in a cupboard and placing an ornamental pig on the counter as a centerpiece.

She later explained, “My act of bed-making had set off a chain of small household tasks… I felt like a grown-up—a happy, legit grown-up with a made bed, a clean sink, one decluttered cupboard, and a pig on the counter. I felt like a woman who had miraculously pulled herself up from the energy-sucking Bermuda Triangle of Household Chaos.” 1

Jennifer Lee Dukes was experiencing the Domino Effect.

The Domino Effect

The Domino Effect states that when you make a change to one behavior it will activate a chain reaction and cause a shift in related behaviors as well. 2

For example, a 2012 study from researchers at Northwestern University found that when people decreased their amount of sedentary leisure time each day, they also reduced their daily fat intake. The participants were never specifically told to eat less fat, but their nutrition habits improved as a natural side effect because they spent less time on the couch watching television and mindlessly eating. One habit led to another, one domino knocked down the next. 3

You may notice similar patterns in your own life. As a personal example, if I stick with my habit of going to the gym, then I naturally find myself more focused at work and sleeping more soundly at night even though I never made a plan to specifically improve either behavior.

The Domino Effect holds for negative habits as well. You may find that the habit of checking your phone leads to the habit of clicking social media notifications which leads to the habit of browsing social media mindlessly which leads to another 20 minutes of procrastination.

In the words of Stanford professor BJ Fogg, “You can never change just one behavior. Our behaviors are interconnected, so when you change one behavior, other behaviors also shift.” 4

Inside the Domino Effect

As best I can tell, the Domino Effect occurs for a two reasons.

First, many of the habits and routines that make up our daily lives are related to one another. There is an astounding interconnectedness between the systems of life and human behavior is no exception. The inherent relatedness of things is a core reason why choices in one area of life can lead to surprising results in other areas, regardless of the plans you make.

Second, the Domino Effect capitalizes on one of the core principles of human behavior: commitment and consistency. This phenomenon is explained in the classic book on human behavior, Influence by Robert Cialdini. The core idea is that if people commit to an idea or goal, even in a very small way, they are more likely to honor that commitment because they now see that idea or goal as being aligned with their self-image.

Returning to the story from the beginning of this article, once Jennifer Lee Dukes began making her bed each day she was making a small commitment to the idea of, “I am the type of person who maintains a clean and organized home.” After a few days, she began to commit to this new self-image in other areas of her home.

This is an interesting byproduct of the Domino Effect. It not only creates a cascade of new behaviors, but often a shift in personal beliefs as well. As each tiny domino falls, you start believing new things about yourself and building identity-based habits.

The Rules of the Domino Effect

The Domino Effect is not merely a phenomenon that happens to you, but something you can create. It is within your power to spark a chain reaction of good habits by building new behaviors that naturally lead to the next successful action.

There are three keys to making this work in real life. Here are the three rules of the Domino Effect:

Start with the thing you are most motivated to do. Start with a small behavior and do it consistently. This will not only feel satisfying, but also open your eyes to the type of person you can become. It does not matter which domino falls first, as long as one falls.

Maintain momentum and immediately move to the next task you are motivated to finish. Let the momentum of finishing one task carry you directly into the next behavior. With each repetition, you will become more committed to your new self-image.

When in doubt, break things down into smaller chunks. As you try new habits, focus on keeping them small and manageable. The Domino Effect is about progress, not results. Simply maintain the momentum. Let the process repeat as one domino automatically knocks down the next.

When one habit fails to lead to the next behavior, it is often because the behavior does not adhere to these three rules. There are many different paths to getting dominoes to fall. Focus on the behavior you are excited about and let it cascade throughout your life.

Read Next

Transform Your Habits: The Science of How to Stick to Good Habits and Break Bad Ones

The Best Psychology Books to Read

The Scientific Argument for Mastering One Thing at a Time

Footnotes

“Want to Change the World? Start by Making Your Bed” by Jennifer Lee Dukes

The phrase, the Domino Effect, comes from the common game people play by setting up a long line of dominoes, gently tapping the first one, and watching as a delightful chain reason proceeds to knock down each domino in the chain. I thought up this particular use of the phrase, but I’ve seen others say similar things like “snowball effect” or “chain reaction.”

Multiple Behavior Change in Diet and Activity: A Randomized Controlled Trial Using Mobile Technology by Bonnie Spring, Kristin Schneider, H.G. McFadden, Jocelyn Vaughn, Andrea T. Kozak, Malaina Smith, Arlen C. Moller, Leonard H. Epstein, Andrew DeMott, Donald Hedeker, Juned Siddique, and Donald M. Lloyd-Jones. Archives of Intern Medicine (2012).

Quote from “BJ’s note” posted on September 21, 2015. It is worth noting that BJ has some fantastic ideas on behavior change on his site, many of which have influenced my thoughts including his idea that “behaviors travel in packs,” which is similar to the core argument of Domino Effect.

July 14, 2016

The Scientific Argument for Mastering One Thing at a Time

Many people, myself included, have multiple areas of life they would like to improve. For example, I would like to reach more people with my writing, to lift heavier weights at the gym, and to start practicing mindfulness more consistently. Those are just a few of the goals I find desirable and you probably have a long list yourself.

The problem is, even if we are committed to working hard on our goals, our natural tendency is to revert back to our old habits at some point. Making a permanent lifestyle change is really difficult.

Recently, I’ve come across a few research studies that (just maybe) will make these difficult lifestyle changes a little bit easier. As you’ll see, however, the approach to mastering many areas of life is somewhat counterintuitive.

Too Many Good Intentions

If you want to master multiple habits and stick to them for good, then you need to figure out how to be consistent. How can you do that?

Well, here is one of the most robust findings from psychology research on how to actually follow through on your goals:

Research has shown that you are 2x to 3x more likely to stick with your habits if you make a specific plan for when, where, and how you will perform the behavior. For example, in one study scientists asked people to fill out this sentence: “During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME OF DAY] at/in [PLACE].”

Researchers found that people who filled out this sentence were 2x to 3x more likely to actually exercise compared to a control group who did not make plans for their future behavior. Psychologists call these specific plans “implementation intentions” because they state when, where, and how you intend to implement a particular behavior.

This finding is well proven and has been repeated in hundreds studies across a broad range of areas. For example, implementation intentions have been found to increase the odds that people will start exercising, begin recycling, stick with studying, and even stop smoking.

However (and this is crucial to understand) follow-up research has discovered implementation intentions only work when you focus on one goal at a time. In fact, researchers found that people who tried to accomplish multiple goals were less committed and less likely to succeed than those who focused on a single goal. 1

This is important, so let me repeat: developing a specific plan for when, where, and how you will stick to a new habit will dramatically increase the odds that you will actually follow through, but only if you focus on a single goal.

What Happens When You Focus on One Thing

Here is another science-based reason to focus on one habit at a time:

When you begin practicing a new habit it requires a lot of conscious effort to remember to do it. After awhile, however, the pattern of behavior becomes easier. Eventually, your new habit becomes a normal routine and the process is more or less mindless and automatic.

Researchers have a fancy term for this process called “automaticity.” Automaticity is the ability to perform a behavior without thinking about each step, which allows the pattern to become automatic and habitual.

But here’s the thing: automaticity only occurs as the result of lots of repetition and practice. The more reps you put in, the more automatic a behavior becomes.

For example, this chart shows how long it takes for people to make a habit out of taking a 10-minute walk after breakfast. In the beginning, the degree of automaticity is very low. After 30 days, the habit is becoming fairly routine. After 60 days, the process is about as automatic as it can become. 2

The most important thing to note is that there is some “tipping point” at which new habits become more or less automatic. The time it takes to build a habit depends on many factors including how difficult the habit is, what your environment is like, your genetics, and more.

That said, the study cited above found the average habit takes about 66 days to become automatic. (Don’t put too much stock in that number. The range in the study was very wide and the only reasonable conclusion you should make is that it will take months for new habits to become sticky.)

Change Your Life Without Changing Your Entire Life

Alright, let’s review what I have suggested to you so far and figure out some practical takeaways.

You are 2x to 3x more likely to follow through with a habit if you make a specific plan for when, where, and how you are going to implement it. This is known as an implementation intention.

You should focus entirely on one habit. Research has found that implementation intentions do not work if you try to improve multiple habits at the same time.

Research has shown that any given habit becomes more automatic with more practice. On average, it takes at least two months for new habits to become automatic behaviors.

This brings us to the punchline of this article…

The counterintuitive insight from all of this research is that the best way to change your entire life is by not changing your entire life. Instead, it is best to focus on one specific habit, work on it until you master it, and make it an automatic part of your daily life. Then, repeat the process for the next habit. 3

The way to master more things in the long-run is to simply focus on one thing right now.

Footnotes

“Too Much of a Good Thing: The Benefits of Implementation Intentions Depend on the Number of Goals” by Amy N. Dalton and Stephen A. Spiller (2012). Journal of Consumer Research.

“How are habits formed: Modeling habit formation in the real world” by Phillippa Lally, Cornelia H. M. Van Jaarsveld, Henry W. W. Potts and Jane Wardle (2010). European Journal of Social Psychology.

You might be thinking, “But you don’t understand, I have so many things I need to change in my life.” Consider this: solving deep life issues often requires some space to sit, think, and figure out a better solution. If you feel like you’re drowning and can barely keep your head above water, then you will almost never find the time to figure out a better approach. By picking one habit and mastering it you not only make progress, but also free up the mental space you need to think through deeper issues. Sometimes you need a good tactic so you can make enough room to figure out a better strategy.