James Clear's Blog, page 7

October 26, 2015

One Research-Backed Way to Effectively Manage Your Stressful and Busy Schedule

About twenty years ago, a group of college students at Stanford University headed home for winter break. While they were gone, they were given the task of keeping a daily journal.

In this journal, some of the students were asked to write about their most important personal values and then describe how the events of each day connected with those values.

Another group of students was simply asked to describe the positive events that happened throughout their day.

When the students returned to school after the break, the researchers discovered that those students who wrote about their personal values were healthier, experienced fewer illnesses, and had better energy and attitude than the students who merely wrote about the positive events in their lives.

As time has gone on, these findings have been replicated in nearly a hundred additional studies. In fact, according to the book The Upside of Stress (audiobook) by Stanford professor Kelly McGonigal:

“It turns out that writing about your values is one of the most effective psychological interventions ever studied. In the short term, writing about personal values makes people feel more powerful, in control, proud, and strong. It also makes them feel more loving, connected, and empathetic toward others. It increases pain tolerance, enhances self-control, and reduces unhelpful rumination after a stressful experience.

In the long term, writing about values has been shown to boost GPAs, reduce doctor visits, improve mental health, and help with everything from weight loss to quitting smoking and reducing drinking. It helps people persevere in the face of discrimination and reduces self-handicapping. In many cases, these benefits are a result of a one-time mindset intervention. People who write about their values once, for ten minutes, show benefits months or even years later.”

—Kelly McGonigal

But why?

The Power of Personal Values

Why would such a simple action like writing about your personal values deliver such incredible results?

Researchers believe that one core reason for this is that journaling about your personal values and connecting them to the events in your life helps to reveal the meaning behind stressful events in your life. Sure, taking care of your family or working long hours on a project can be draining, but if you know why these actions are important to you, then you are much better equipped to handle that stress.

In fact, writing about how our day-to-day actions match up with our deepest personal values can mentally and biologically improve our ability to deal with stress. In McGonigal’s words, “Stressful experiences were no longer simply hassles to endure; they became an expression of the students’ values… small things that might otherwise have seemed irritating became moments of meaning.”

Living Out Your Personal Values

My own experiences have mirrored the findings of the researchers. In fact, I stumbled into a very similar practice by accident before I had even heard about these research findings.

Each year, I conduct an Integrity Report. This report has three sections. First, I list and explain my core values. Second, I discuss how I have lived and worked by those core values over the previous year. Third, I hold myself accountable and discuss how I have missed the mark over the previous year and where I did not live up to my core values.

I have found that doing this simple exercise each year actually helps to keep my values top of mind on a daily basis. Furthermore, I have direct proof of how and why my writing and work connects with my most meaningful personal values. This type of reinforcement makes it easier for me to continue working when the work gets stressful and overwhelming.

If you’re interested in writing about your own personal values, I put together a core values list with more than 50 common personal values. You are welcome to browse that list for inspiration when considering your own values.

Whether you choose to conduct an integrity report like I do or keep a journal like the Stanford students, the science is pretty clear on the benefits. Writing about your personal values will make your life better and improve your ability to manage stressful events in your life.

P.S. The Stress Management Seminar

If you enjoyed this little lesson on how to effectively manage stress, then you’ll love my complete Stress Management Seminar. It’s being broadcast online on October 27, 2015. Can’t attend live? No worries, everyone who signs up with get a full audio and video recording emailed to them.

October 12, 2015

Free Download: Transform Your Habits (3rd Edition)

Today I am excited to release the 3rd edition of Transform Your Habits, my popular guide on habit change and behavior science. Transform Your Habits has been downloaded over 150,000 times and it is the highest-rated habits book on Goodreads.

This guide is filled with some of my best writing on the science of forming better habits and the 3rd edition features an expanded section on how to break bad habits.

Servant leadership is one of the core values I mention in my annual Integrity Reports and so I am happy to offer Transform Your Habits a free download to members of our wonderful community.

What Will You Learn?

Here’s a quick taste of what you can expect to learn in this version of the guide…

How to reverse your bad habits and stick to good ones.

The science of how your brain processes habits.

The common mistakes most people make (and how to avoid them).

How to overcome a lack of motivation and willpower.

How to develop a stronger identity and believe in yourself.

How to make time for new habits (even when your life gets crazy).

How to design your environment to make success easier.

How to make big changes in your life without overwhelming yourself.

How to get back on track when you get off course with your goals.

And most importantly, how to put these ideas into practice in real life.

… and of course those are just the highlights.

The 3rd edition of Transform Your Habits is filled with more than 49 pages of information on mastering your habits, improving your performance, and boosting your mental and physical health. I hope you enjoy it!

Get it Now (For Free)

This guide is available as a free download to members of our wonderful community.

All you have to do is enter your email address below and click “Get Updates!” and the guide is all yours. In addition to the guide, you’ll also receive useful articles every week about sticking to good habits and living healthy.

(If you’re already an email subscriber, then you can just enter your email address again and you’ll be sent straight to the download page. You won’t be subscribed twice.)

My email address is…

You’ll get one email every Monday and Thursday.

No spam guaranteed. Unsubscribe at any time.

P.S. Stress Management Seminar

In addition to the free writing I share each week, I also conduct online seminars each quarter which dive into greater detail on a particular aspect of building better habits.

On October 27, 2015, I will be running a seminar on stress management habits. I’ll be talking about practical, science-based ideas for simplifying your life, letting go of worry, decluttering your brain, and preventing the little things from taking over your day. I’ll have more information on this seminar soon, but if you are already interested you can grab an early bird ticket here.

October 5, 2015

The Diderot Effect: Why We Want Things We Don’t Need — And What to Do About It

The famous French philosopher Denis Diderot lived nearly his entire life in poverty, but that all changed in 1765.

Diderot was 52 years old and his daughter was about to be married, but he could not afford to provide a dowry. Despite his lack of wealth, Diderot’s name was well-known because he was the co-founder and writer of Encyclopédie, one of the most comprehensive encyclopedias of the time.

When Catherine the Great, the emperor of Russia, heard of Diderot’s financial troubles she offered to buy his library from him for £1000 GBP, which is approximately $50,000 USD in 2015 dollars. Suddenly, Diderot had money to spare. 1

Shortly after this lucky sale, Diderot acquired a new scarlet robe. That’s when everything went wrong. 2

The Diderot Effect

Diderot’s scarlet robe was beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that he immediately noticed how out of place it seemed when surrounded by the rest of his common possessions. In his words, there was “no more coordination, no more unity, no more beauty” between his robe and the rest of his items. The philosopher soon felt the urge to buy some new things to match the beauty of his robe. 3

He replaced his old rug with a new one from Damascus. He decorated his home with beautiful sculptures and a better kitchen table. He bought a new mirror to place above the mantle and his “straw chair was relegated to the antechamber by a leather chair.”

These reactive purchases have become known as the Diderot Effect.

The Diderot Effect states that obtaining a new possession often creates a spiral of consumption which leads you to acquire more new things. As a result, we end up buying things that our previous selves never needed to feel happy or fulfilled.

Denis Diderot as depicted by Louis-Michel van Loo in 1767. In this painting Diderot is wearing a robe similar to the one that prompted his famous essay on the Diderot Effect.

Denis Diderot as depicted by Louis-Michel van Loo in 1767. In this painting Diderot is wearing a robe similar to the one that prompted his famous essay on the Diderot Effect.Why We Want Things We Don’t Need

Like many others, I have fallen victim to the Diderot Effect. I recently bought a new car and I ended up purchasing all sorts of additional things to go inside it. I bought a tire pressure gauge, a car charger for my cell phone, an extra umbrella, a first aid kit, a pocket knife, a flashlight, emergency blankets, and even a seatbelt cutting tool.

Allow me to point out that I owned my previous car for nearly 10 years and at no point did I feel that any of the previously mentioned items were worth purchasing. And yet, after getting my shiny new car, I found myself falling into the same consumption spiral as Diderot.

You can spot similar behaviors in many other areas of life:

You buy a new dress and now you have to get shoes and earrings to match.

You buy a CrossFit membership and soon you’re paying for foam rollers, knee sleeves, wrist wraps, and paleo meal plans.

You buy your kid an American Girl doll and find yourself purchasing more accessories than you ever knew existed for dolls.

You buy a new couch and suddenly you’re questioning the layout of your entire living room. Those chairs? That coffee table? That rug? They all gotta go.

Life has a natural tendency to become filled with more. We are rarely looking to downgrade, to simplify, to eliminate, to reduce. Our natural inclination is always to accumulate, to add, to upgrade, and to build upon.

In the words of sociology professor Juliet Schor, “the pressure to upgrade our stock of stuff is relentlessly unidirectional, always ascending.” 4

Mastering the Diderot Effect

The Diderot Effect tells us that your life is only going to have more things fighting to get in it, so you need to to understand how to curate, eliminate, and focus on the things that matter.

Reduce exposure. Nearly every habit is initiated by a trigger or cue. One of the quickest ways to reduce the power of the Diderot Effect is to avoid the habit triggers that cause it in the first place. Unsubscribe from commercial emails. Call the magazines that send you catalogs and opt out of their mailings. Meet friends at the park rather than the mall. Block your favorite shopping websites using tools like Freedom.

Buy items that fit your current system. You don’t have to start from scratch each time you buy something new. When you purchase new clothes, look for items that work well with your current wardrobe. When you upgrade to new electronics, get things that play nicely with your current pieces so you can avoid buying new chargers, adapters, or cables.

Set self-imposed limits. Live a carefully constrained life by creating limitations for you to operate within. Juliet Schor provides a great example with this quote…

“Imagine the following. A community group in your town organizes parents to sign a pledge agreeing to spend no more than $50 on athletic shoes for their children. The staff at your child’s day-care center requests a $75 limit on spending for birthday parties. The local school board rallies community support behind a switch to school uniforms. The PTA gets 8o percent of parents to agree to limit their children’s television watching to no more than one hour per day.

Do you wish someone in your community or at your children’s school would take the lead in these or similar efforts? I think millions of American parents do. Television, shoes, clothes, birthday parties, athletic uniforms-these are areas where many parents feel pressured into allowing their children to consume at a level beyond what they think is best, want to spend, or can comfortably afford.”

—Juliet Schor, The Overspent American

Buy One, Give One. Each time you make a new purchase, give something away. Get a new TV? Give your old one away rather than moving it to another room. The idea is to prevent your number of items from growing. Always be curating your life to include only the things that bring you joy and happiness.

Go one month without buying something new. Don’t allow yourself to buy any new items for one month. Instead of buying a new lawn mower, rent one from a neighbor. Get your new shirt from the thrift store rather than the department store. The more we restrict ourselves, the more resourceful we become.

Let go of wanting things. There will never be a level where you will be done wanting things. There is always something to upgrade to. Get a new Honda? You can upgrade to a Mercedes. Get a new Mercedes? You can upgrade to a Bentley. Get a new Bentley? You can upgrade to a Ferrari. Get a new Ferrari? Have you thought about buying a private plane? Realize that wanting is just an option your mind provides, not an order you have to follow.

How to Overcome the Consumption Tendency

Our natural tendency is to consume more, not less. Given this tendency, I believe that taking active steps to reduce the flow of unquestioned consumption makes our lives better.

Personally, my goal is not to reduce life to the fewest amount of things, but to fill it with the optimal amount of things. I hope this article will help you consider how to do the same.

In Diderot’s words, “Let my example teach you a lesson. Poverty has its freedoms; opulence has its obstacles.” 5

Footnotes

In addition to her payment for the library, Catherine the Great asked Diderot to keep the books until she needed them and offered to pay him a yearly salary to act as her librarian. (Source)

Diderot’s scarlet robe is frequently described as a gift from a friend. However, I could find no original source claiming it was a gift nor any mention of the friend who supplied the robe. If you happen to know any historians specializing in robe acquisitions, feel free to point them my way so we can clarify the mystery of the source of Diderot’s famous scarlet robe.

The quotes from Denis Diderot in this article come from his essay, “Regrets for my Old Dressing Gown.”

“The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need” by Juliet Schor. Chapter 6.

Thanks to my friend Joshua Becker for originally sparking my interest in the Diderot Effect by writing his own article on the topic.

September 29, 2015

Debunking the Eureka Moment: Why Creativity Is a Process, Not an Event

In 1666, one of the most influential scientists in history was strolling through a garden when he was struck with a flash of creative brilliance that would change the world.

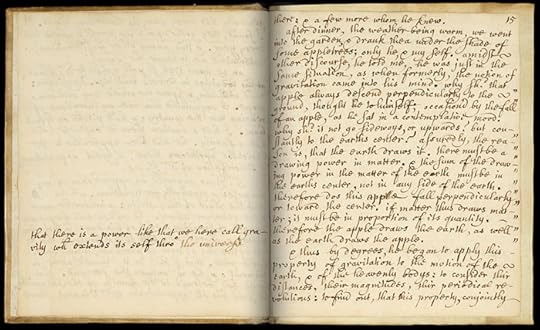

While standing under the shade of an apple tree, Sir Isaac Newton saw an apple fall to the ground. “Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,” Newton wondered. “Why should it not go sideways, or upwards, but constantly to the earth’s center? Assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. There must be a drawing power in matter.” 1

And thus, the concept of gravity was born.

The story of the falling apple has become one of the lasting and iconic examples of the creative moment. It is a symbol of the inspired genius that fills your brain during those “light bulb moments” when creative conditions are just right. 2

What most people forget, however, is that Newton worked on his ideas about gravity for nearly twenty years until, in 1687, he published his groundbreaking book, The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. The falling apple was merely the beginning of a train of thought that continued for decades.

The famous page describing Newton’s apple incident in Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life by William Stukeley.

The famous page describing Newton’s apple incident in Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life by William Stukeley.Newton isn’t the only one to wrestle with a great idea for years. Creative thinking is a process for all of us. In this article, I’ll share the science of creative thinking, discuss which conditions drive creativity and which ones hinder it, and offer practical tips for becoming more creative.

Creative Thinking: Destiny or Development?

Creative thinking requires our brains to make connections between seemingly unrelated ideas. Is this a skill that we are born with or one that we develop through practice? Let’s look at the research to uncover an answer.

In the 1960s, a creative performance researcher named George Land conducted a study of 1,600 five-year-olds and 98 percent of the children scored in the “highly creative” range. Dr. Land re-tested each subject during five year increments. When the same children were 10-years-old, only 30 percent scored in the highly creative range. This number dropped to 12 percent by age 15 and just 2 percent by age 25. As the children grew into adults they effectively had the creativity trained out of them. In the words of Dr. Land, “non-creative behavior is learned.” 3

Similar trends have been discovered by other researchers. For example, one study of 272,599 students found that although IQ scores have risen since 1990, creative thinking scores have decreased. 4

This is not to say that creativity is 100 percent learned. Genetics do play a role. According to psychology professor Barbara Kerr, “approximately 22 percent of the variance [in creativity] is due to the influence of genes.” This discovery was made by studying the differences in creative thinking between sets of twins. 5

All of this to say, claiming that “I’m just not the creative type” is a pretty weak excuse for avoiding creative thinking. Certainly, some people are primed to be more creative than others. However, nearly every person is born with some level of creative skill and the majority of our creative thinking abilities are trainable.

Now that we know creativity is a skill that can be improved, let’s talk about why—and how—practice and learning impacts your creative output.

Intelligence and Creative Thinking

What does it take to unleash your creative potential?

As I mentioned in my article on Threshold Theory, being in the top 1 percent of intelligence has no correlation with being fantastically creative. Instead, you simply have to be smart (not a genius) and then work hard, practice deliberately and put in your reps.

As long as you meet a threshold of intelligence, then brilliant creative work is well within your reach. In the words of researchers from a 2013 study, “we obtained evidence that once the intelligence threshold is met, personality factors become more predictive for creativity.” 6

Growth Mindset

What exactly are these “personality factors” that researchers are referring to when it comes to boosting your creative thinking?

One of the most critical components is how you view your talents internally. More specifically, your creative skills are largely determined by whether you approach the creative process with a fixed mindset or a growth mindset.

The differences between these two mindsets are described in detail in Carol Dweck’s fantastic book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (audiobook).

The basic idea is that when we use a fixed mindset we approach tasks as if our talents and abilities are fixed and unchanging. In a growth mindset, however, we believe that our abilities can be improved with effort and practice. Interestingly, we can easily nudge ourselves in one direction or another based on how we talk about and praise our efforts.

Here’s a brief summary in Dweck’s words:

“The whole self-esteem movement taught us erroneously that praising intelligence, talent, abilities would foster self-confidence, self-esteem, and everything great would follow. But we’ve found it backfires. People who are praised for talent now worry about doing the next thing, about taking on the hard task, and not looking talented, tarnishing that reputation for brilliance. So instead, they’ll stick to their comfort zone and get really defensive when they hit setbacks.

So what should we praise? The effort, the strategies, the doggedness and persistence, the grit people show, the resilience that they show in the face of obstacles, that bouncing back when things go wrong and knowing what to try next. So I think a huge part of promoting a growth mindset in the workplace is to convey those values of process, to give feedback, to reward people engaging in the process, and not just a successful outcome.”

—Carol Dweck 7

Embarrassment and Creativity

How can we apply the growth mindset to creativity in practical terms? In my experience it comes down to one thing: the willingness to look bad when pursuing an activity.

As Dweck says, the growth mindset is focused more on the process than the outcome. This is easy to accept in theory, but very hard to stick to in practice. Most people don’t want to deal with the accompanying embarrassment or shame that is often required to learn a new skill.

The list of mistakes that you can never recover from is very short. I think most of us realize this on some level. We know that our lives will not be destroyed if that book we write doesn’t sell or if we get turned down by a potential date or if we forget someone’s name when we introduce them. It’s not necessarily what comes after the event that worries us. It’s the possibility of looking stupid, feeling humiliated, or dealing with embarrassment along the way that prevents us from getting started at all.

In order to fully embrace the growth mindset and enhance your creativity, you need to be willing to take action in the face of these feelings which so often deter us.

How to Be More Creative

Assuming that you are willing to do the hard work of facing your inner fears and working through failure, here are a few practical strategies for becoming more creative.

Constrain yourself. Carefully designed constraints are one of your best tools for sparking creative thinking. Dr. Seuss wrote his most famous book when he limited himself to 50 words. Soccer players develop more elaborate skill sets when they play on a smaller field. Designers can use a 3-inch by 5-inch canvas to create better large scale designs. The more we limit ourselves, the more resourceful we become.

Write more. For nearly three years, I published a new article every Monday and every Thursday at JamesClear.com. The longer I stuck with this schedule, the more I realized that I had to write about a dozen average ideas before I uncovered a brilliant one. By producing a volume of work, I created a larger surface area for a creative spark to hit me.

Not interested in sharing your writing publicly? Julia Cameron’s Morning Pages routine is a fantastic way to use writing to increase your creativity even if you have no intention of writing for others.

Broaden your knowledge. One of my most successful creative strategies is to force myself to write about seemingly disparate topics and ideas. For example, I have to be creative when I use 1980s basketball strategies or ancient word processing software or zen buddhism to describe our daily behaviors. In the words of psychologist Robert Epstein, “You’ll do better in psychology and life if you broaden your knowledge.”

Sleep longer. In my article on how to get better sleep, I shared a study from the University of Pennsylvania, which revealed the incredible impact of sleep on mental performance. The main finding was this: Sleep debt is cumulative and if you get 6 hours of sleep per night for two weeks straight, your mental and physical performance declines to the same level as if you had stayed awake for 48 hours straight. Like all cognitive functions, creative thinking is significantly impaired by sleep deprivation.

Enjoy sunshine and nature. One study tested 56 backpackers with a variety of creative thinking questions before and after a 4-day backpacking trip. The researchers found that by the end of the trip the backpackers had increased their creativity by 50 percent. This research supports the findings of other studies, which show that spending time in nature and increasing your exposure to sunlight can lead to higher levels of creativity. 8

Embrace positive thinking. It sounds a bit fluffy for my taste, but positive thinking can lead to significant improvements in creative thinking. Why? Positive psychology research has revealed that we tend to think more broadly when we are happy. This concept, which is known as the Broaden and Build Theory, makes it easier for us to make creative connections between ideas. Conversely, sadness and depression seems to lead to more restrictive and limited thinking.

Ship it. The honest truth is that creativity is just hard work. The single best thing you can do is choose a pace you can sustain and ship content on a consistent basis. Commit to the process and create on a schedule. The only way creativity becomes a reality is by shipping.

Final Thoughts on Creative Thinking

Creativity is a process, not an event. You have to work through mental barriers and internal blocks. You have to commit to practicing your craft deliberately. And you have to stick with the process for years, perhaps even decades like Newton did, in order to see your creative genius blossom.

The ideas in this article offer a variety approaches on how to be more creative. If you’re looking for additional practical strategies on how to improve your creativity habits, then read my free guide called Mastering Creativity.

Footnotes

Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life by William Stukeley. Page 15.

In some versions of the famous incident, Newton is hit on the head by the falling apple and screams “Eureka!” when he recognizes the importance of his brilliant insight. There is no evidence that an apple actually plunked ol’ Isaac on the head, but the story of the falling apple does appear to be true. Both William Stukeley, a friend of Newton, and John Conduitt, an assistant to Newton, confirmed in separate texts that the sight of a falling apple kickstarted Newton’s thoughts about gravity.

Breakpoint and Beyond: Mastering the Future Today by George Land and Beth Jarman (1992).

The Creativity Crisis: The Decrease in Creative Thinking Scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, Volume 23, Issue 4, 2011.

Encyclopedia of Giftedness, Creativity, and Talent By Barbara Kerr

“The relationship between intelligence and creativity” by Jauk, Benedek, Dunst, Neubauer.

“The Right Mindset for Success.” Interview with Carol Dweck for Harvard Business Review.

Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings by Ruth Ann Atchley, David Strayer, Paul Atchley.

September 21, 2015

Scott Dinsmore: A Tribute

My friend Scott Dinsmore died last week. He passed away during a tragic mountain climbing accident on Mount Kilimanjaro. He was 33 years old.

Scott is my first friend to die young and unexpectedly. One of the hardest parts of growing up is realizing that life is a race with a different finish line for each of us. We walk this journey together, but we all finish it separately.

This article is about Scott, about the lessons I learned from him, about the global movement he created, and about the incredible difference one person can make in the world. My words are a poor tribute to the life he lived, but they are the best I can offer.

The Mastermind

In August of 2011, Tyler Tervooren reached out to me and asked if I would like to join a three-person mastermind group. It would include Scott, Tyler, and myself.

The three of us were just beginning to take online entrepreneurship seriously. We used the calls to talk through business issues, make big plans, hold ourselves accountable, and—mostly—as a form of therapy for dealing with the rollercoaster ride of emotions that awaits every entrepreneur.

Because of these calls, I spoke with Scott every month for the last four years. He became a peer, a mentor, a friend. When we started, I had no idea that I was about to watch him connect people from around the world and make a dent in his corner of the universe.

TEDx

Scott ran a business called Live Your Legend where he focused on helping people find and do work they love. He was on a quest to help people make a living off of their passion.

His website grew rapidly. Out of the three of us, Scott’s site was the first to hit 10,000 subscribers. About a year after we began our monthly calls, Scott told me that he wanted to give a TEDx Talk.

He spent months talking to previous speakers and conference organizers. He went to dinners and other conferences with the hope of connecting with someone who could get him on the shortlist for a TEDx event. Eventually, he worked his way into the second alternate spot for TEDxGoldenGatePark.

A month before the event, the first speaker dropped out. Six days before the event, a second speaker dropped out. Scott received the call informing him that he would be speaking, created his presentation in six days, and delivered his now famous TEDx Talk titled, “How to Find and Do Work You Love.”

Within a week, his talk had nearly 50,000 views. Within a year, 500,000 views. By the time he passed away, it was one of the 25 most popular TEDx Talks in history with more than 2.5 million views.

I was fortunate to get a behind-the-scenes look at how hard Scott worked to achieve his success. He didn’t stand by and hope for his chance to come. He didn’t wait patiently to be tapped, nominated, appointed, or chosen. He worked his tail off to get the chance to be on stage and when the window of opportunity opened, he made the most of it.

The World’s Greatest Gym

A few months after his TEDx Talk, I visited Scott in San Francisco. We decided to get a workout in while I was there. I just assumed that we would head to his local gym and train together. When Scott picked me up, I asked which gym we were going to and he looked at me like I was crazy.

“Hell no. You’re not coming to San Francisco and training in some gym.”

We drove down by the marina and parked along the bay near Chrissy Field Marsh. The early morning fog had burned off and the sun was warming the Golden Gate Bridge. The weather was perfect.

We ran for a mile or two along the water before Scott told me that he had designed a workout for us. We ran back to his SUV, he pulled a few kettlebells out of his back seat with a grin on his face, and we proceeded to do so many damn burpees that I nearly threw up.

Before our final set of kettlebell swings, Scott asked a woman walking by to snap a photo of us working out in the world’s greatest gym. Now that he is gone, I find myself wishing that I had more photos of our times together. I wish had pictures from our dinner in San Francisco, from our brunch in Portland, from the drinks we shared at the hotel bar or from the conversations we had on the rooftop patio at WDS. Memories will have to do.

Take photos with the people you love. It’s too easy to let those moments pass us by.

Showing a good friend the best gym in San Francisco. No extra charge… @james_clear

A photo posted by Scott Dinsmore (@scottluckeydinsmore) on Oct 22, 2013 at 8:51am PDT

Going Global

Scott and I both had dreams about facilitating ways for our community to meet in the real world and not just online.

We decided that hosting a series of meetups in various cities would probably be the best way to start. I got commitments from readers in over 60 countries who expressed an interest in hosting a local meetup in their area. Scott developed his own list.

The software for organizing something like this wasn’t great and while I was busy whining about how I didn’t have the right tools, Scott said, “Screw it. I’m going to go with what we have.”

Live Your Legend LOCAL was born. The global kickoff event featured simultaneous meetups in more than 150 cities. Scott asked me to be the featured speaker at the event in my area. I was happy to help.

By the time Scott passed away, Live Your Legend LOCAL had grown to include monthly in-person meetups in 206 cities in 57 countries around the world.

The scope of the project is incredible, but I know that the impact of the venture meant even more to Scott than the numbers. He told me with pride about one attendee who, after attending the meetup with his wife, sent Scott an email that said, “After the meetup, my wife told me that she finally understands me.” There were tons of testimonials like that.

The moment that Live Your Legend LOCAL launched, Scott’s work and mission became bigger than himself. His life was a perfect example of how work is not merely a task to be finished, but an opportunity for us to do something that matters. I’m so grateful that I was there to witness it.

Living His Legend

If you could rewind the clock to January 1, 2015 and tell Scott that he had eight months to live, he very well might have done the same thing he actually did.

The climbing accident that took Scott’s life happened during a year-long round-the-world trip with his wife, Chelsea. He traveled the globe with the person he loved most in the world. He shared meals with people he impacted through his work. He sipped wine in France with Leo. He battled strangers in a Mexican dance off with Corbett. He re-lived his honeymoon in Croatia.

Is it even possible to fill eight months with more adventure, love, passion, and joy? His final year was a gift.

One of my favorite memories of Scott was the night he ran through the streets of Portland in a cape, twirling at every turn, while Steve Kamb and I ran behind him covered in paint of all colors. We finished the night drinking beers and doing impersonations of one another. I can’t imagine what the strangers who passed us thought, but we were having a blast.

We tell people to follow their dreams. We claim that you should be the change that you wish to see in the world. We encourage people to bring others together and to create projects and businesses that impact those around them. Start a business. Travel the world. Live life to the fullest.

Scott actually did those things.

You Are Not Alone

During one of our regular calls a few months ago, Scott said something that I immediately wrote down and placed at the top of my mission statement.

“People just don’t want to do this journey solo.”

We all need to be surrounded by people who can support our dreams. We all need to connect with someone and think, “You understand me.” Scott used Live Your Legend to build a space where connections like that could happen. He fostered understanding, meaning, and connection for people all around the world.

And as I try to grapple with this loss, I’d like to extend Scott’s advice to the people who need it most:

To Scott’s family and his closest friends, you don’t have to do this journey solo. I am so sorry for your loss. Know that Scott loved you, that he talked of you often, and that he was grateful for your presence in his life.

To his wonderful wife Chelsea, you don’t have to do this journey solo. I’m here to talk, to support, to help. That’s true today. It’s true in a month. It’s true in a year. And I know you already know this, but let me tell you again: Scott adored you. He loved you fully. He was constantly talking about how lucky he was for “marrying up.”

And to Scott, wherever you are now, you didn’t make this journey solo and you won’t make the next one alone either. We are with you. We are here to carry on the work you did. You are not alone.

September 14, 2015

The Next Chapter: I’m No Longer Writing Twice Per Week. Here’s Why

For nearly three years, I have written a new article on JamesClear.com every Monday and every Thursday.

This twice-per-week pattern has changed my business and my life. When I started this habit on November 12, 2012, I had zero readers. Today, more than 200,000 people receive my email newsletter each week.

Along the way, I’ve met many of you at live events, heard from thousands of you via email, and enjoyed the satisfaction of knowing that my writing is making some small difference in the world. I’m very thankful to have you reading each week.

But today marks the end of my Monday-Thursday streak and the beginning of something new. I will now be writing once per week. Every Monday, I’ll post a new article.

Here’s why…

Why Write?

From the very beginning my intention has always been to create work that matters. Usually, this means I write articles that attempt to answer the question, “How can we live better?” 1

When I started, there was no way I could answer that question for myself or for others without developing some level of skill as a writer. I needed to write twice per week to find my voice. I needed to write twice per week to build an audience. I needed to write twice per week to churn through my average ideas, so that I could uncover the great ones. In the beginning, I had to put in my reps.

After three years, my mission is still the same: to create work that matters. The difference, of course, is that now that I have put in some reps (260+ articles) and I have you all reading each week (over 5 million readers per year).

I feel a serious level of responsibility to produce work that is more meaningful and more impactful for your life. I’m grateful that many of you find my previous work useful and inspiring, but I believe it’s time for me to step up my game.

To produce a higher quality of work I need to improve the way I practice my craft. I need the time and space to create a higher standard of work. I need to build upon my previous efforts and pour more effort into each article. In the words of Marshall Goldsmith, “What got you here won’t get you there.”

This is the reason for the change in my writing schedule.

Why Do We Have Habits?

I often write about how to build better habits. Maintaining my twice-per-week writing schedule for nearly three years was one example of how I lived this philosophy out.

But why do we have habits?

We don’t build new habits in the hope that our lives will become fully automated, repetitive, and robotic. We do it because habits are a tool for helping us do the things that make us come alive more frequently and more consistently. Habits are a method for accomplishing the things that provide meaning and purpose to our lives.

That’s exactly what my twice per week schedule did for the previous three years. It was a tool that helped me produce a volume of work, improve my skill set, and create meaningful work.

My new writing schedule will give me the space to create work that I hope will be more inspiring, more thoughtful, and more meaningful. I’m so excited to share what this next chapter has in store. I’ll see you on Monday.

Footnotes

When I say that the central question I’m trying to answer is, “How can we live better?” I don’t just mean, “How can we live better as individuals?” I mean, “How can we live better as friends, as family members, and as a community?” We’re all in this together and I’m excited to produce better work that empowers us an individuals, connects us as friends, and inspires us as a community.

September 10, 2015

5 Common Mental Errors That Sway You From Making Good Decisions

I like to think of myself as a rational person, but I’m not one. The good news is it’s not just me — or you. We are all irrational.

For a long time, researchers and economists believed that humans made logical, well-considered decisions. In recent decades, however, researchers have uncovered a wide range of mental errors that derail our thinking. Sometimes we make logical decisions, but there are many times when we make emotional, irrational, and confusing choices.

Psychologists and behavioral researchers love to geek out about these different mental mistakes. There are dozens of them and they all have fancy names like “mere exposure effect” or “narrative fallacy.” But I don’t want to get bogged down in the scientific jargon today. Instead, let’s talk about the mental errors that show up most frequently in our lives and break them down in easy-to-understand language.

Here are five common mental errors that sway you from making good decisions.

1. Survivorship Bias.

Nearly every popular online media outlet is filled with survivorship bias these days. Anywhere you see articles with titles like “8 Things Successful People Do Everyday” or “The Best Advice Richard Branson Ever Received” or “How LeBron James Trains in the Off-Season” you are seeing survivorship bias in action.

Survivorship bias refers to our tendency to focus on the winners in a particular area and try to learn from them while completely forgetting about the losers who are employing the same strategy.

There might be thousands of athletes who train in a very similar way to LeBron James, but never made it to the NBA. The problem is nobody hears about the thousands of athletes who never made it to the top. We only hear from the people who survive. We mistakenly overvalue the strategies, tactics, and advice of one survivor while ignoring the fact that the same strategies, tactics, and advice didn’t work for most people.

Another example: “Richard Branson, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg all dropped out of school and became billionaires! You don’t need school to succeed. Entrepreneurs just need to stop wasting time in class and get started.”

It’s entirely possible that Richard Branson succeeded in spite of his path and not because of it. For every Branson, Gates, and Zuckerberg, there are thousands of other entrepreneurs with failed projects, debt-heavy bank accounts, and half-finished degrees. Survivorship bias isn’t merely saying that a strategy may not work well for you, it’s also saying that we don’t really know if the strategy works well at all.

When the winners are remembered and the losers are forgotten it becomes very difficult to say if a particular strategy leads to success.

2. Loss Aversion.

Loss aversion refers to our tendency to strongly prefer avoiding losses over acquiring gains. Research has shown that if someone gives you $10 you will experience a small boost in satisfaction, but if you lose $10 you will experience a dramatically higher loss in satisfaction. Yes, the responses are opposite, but they are not equal in magnitude. 1

Our tendency to avoid losses causes us to make silly decisions and change our behavior simply to keep the things that we already own. We are wired to feel protective of the things we own and that can lead us to overvalue these items in comparison with the options.

For example, if you buy a new pair of shoes it may provide a small boost in pleasure. However, even if you never wear the shoes, giving them away a few months later might be incredibly painful. You never use them, but for some reason you just can’t stand parting with them. Loss aversion.

Similarly, you might feel a small bit of joy when you breeze through green lights on your way to work, but you will get downright angry when the car in front of you sits at a green light and you miss the opportunity to make it through the intersection. Losing out on the chance to make the light is far more painful than the pleasure of hitting the green light from the beginning.

3. The Availability Heuristic.

The Availability Heuristic refers to a common mistake that our brains make by assuming that the examples which come to mind easily are also the most important or prevalent things.

For example, research by Steven Pinker at Harvard University has shown that we are currently living in the least violent time in history. There are more people living in peace right now than ever before. The rates of homicide, rape, sexual assault, and child abuse are all falling.2

Most people are shocked when they hear these statistics. Some still refuse to believe them. If this is the most peaceful time in history, why are there so many wars going on right now? Why do I hear about rape and murder and crime every day? Why is everyone talking about so many acts of terrorism and destruction?

Welcome to the availability heuristic.

The answer is that we are not only living in the most peaceful time in history, but also the best reported time in history. Information on any disaster or crime is more widely available than ever before. A quick search on the Internet will pull up more information about the terrorist act of your choice than any newspaper could have every delivered 100 years ago.

The overall percentage of dangerous events is decreasing, but the likelihood that you hear about one of them (or many of them) is increasing. And because these events are readily available in our mind, our brains assume that they happen with greater frequency than they actually do.

We overvalue and overestimate the impact of things that we can remember and we undervalue and underestimate the prevalence of the events we hear nothing about. 3

4. Anchoring.

There is a burger joint close to my hometown that is known for gourmet burgers and cheeses. On the menu, they very boldly state, “LIMIT 6 TYPES OF CHEESE PER BURGER.”

My first thought: This is absurd. Who gets six types of cheese on a burger?

My second thought: Which six am I going to get?

I didn’t realize how brilliant the restaurant owners were until I learned about anchoring. You see, normally I would just pick one type of cheese on my burger, but when I read “LIMIT 6 TYPES OF CHEESE” on the menu, my mind was anchored at a much higher number than usual.

Most people won’t order six types of cheese, but that anchor is enough to move the average up from one slice to two or three pieces of cheese and add a couple extra bucks to each burger. You walk in planning to get a normal meal. You walk out wondering how you paid $14 for a burger and if your date will let you roll the windows down on the way home.

This effect has been replicated in a wide range of research studies and commercial environments. For example, business owners have found that if you say “Limit 12 per customer” then people will buy twice as much product compared to saying, “No limit.”

In one research study, volunteers were asked to guess the percentage of African nations in the United Nations. Before they guessed, however, they had to spin a wheel that would land on either the number 10 or the number 65. When volunteers landed on 65, the average guess was around 45 percent. When volunteers landed on 10, the average estimate was around 25 percent. This 20 digit swing was simply a result of anchoring the guess with a higher or lower number immediately beforehand. 4

Perhaps the most prevalent place you hear about anchoring is with pricing. If the price tag on a new watch is $500, you might consider it too high for your budget. However, if you walk into a store and first see a watch for $5,000 at the front of the display, suddenly the $500 watch around the corner seems pretty reasonable. Many of the premium products that businesses sell are never expected to sell many units themselves, but they serve the very important role of anchoring your mindset and making mid-range products appear much cheaper than they would on their own.

5. Confirmation Bias.

The Grandaddy of Them All. Confirmation bias refers to our tendency to search for and favor information that confirms our beliefs while simultaneously ignoring or devaluing information that contradicts our beliefs.

For example, Person A believes climate change is a serious issue and they only search out and read stories about environmental conservation, climate change, and renewable energy. As a result, Person A continues to confirm and support their current beliefs.

Meanwhile, Person B does not believe climate change is a serious issue, and they only search out and read stories that discuss how climate change is a myth, why scientists are incorrect, and how we are all being fooled. As a result, Person B continues to confirm and support their current beliefs.

Changing your mind is harder than it looks. The more you believe you know something, the more you filter and ignore all information to the contrary.

You can extend this thought pattern to nearly any topic. If you just bought a Honda Accord and you believe it is the best car on the market, then you’ll naturally read any article you come across that praises the car. Meanwhile, if another magazine lists a different car as the best pick of the year, you simply dismiss it and assume that the editors of that particular magazine got it wrong or were looking for something different than what you were looking for in a car. 5

It is not natural for us to formulate a hypothesis and then test various ways to prove it false. Instead, it is far more likely that we will form one hypothesis, assume it is true, and only seek out and believe information that supports it. Most people don’t want new information, they want validating information.

Where to Go From Here

Once you understand some of these common mental errors your first response might be something along the lines of, “I want to stop this from happening! How can I prevent my brain from doing these things?”

It’s a fair question, but it’s not quite that simple. Rather than thinking of these miscalculations as a signal of a broken brain, it’s better to consider them as evidence that the shortcuts your brain uses aren’t useful in all cases. There are many areas of everyday life where the mental processes mentioned above are incredibly useful. You don’t want to eliminate these thinking mechanisms.

The problem is that our brains are so good at performing these functions — they slip into these patterns so quickly and effortlessly — that we end up using them in situations where they don’t serve us.

In cases like these, self-awareness is often one of our best options. Hopefully this article will help you spot these errors next time you make them. 6

Footnotes

“Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model.” by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

“The World is Not Falling Apart” by Steven Pinker.

“Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability.” by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.

“Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.” by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman.

“Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises.” by Raymond S. Nickerson

Thanks to Sam Sager for his help researching this post.

September 7, 2015

The Impact Bias: How to Be Happy When Everything Goes Wrong

In the summer of 2010, Rachelle Friedman was preparing for one of the best periods of her life. She was recently engaged, surrounded by her best friends, and enjoying her bachelorette party.

Friedman and her friends were spending the day at the pool when one of them playfully pushed her into the shallow end of the water. Friedman floated slowly to the top of the pool until her face emerged. It was immediately obvious that something was wrong. “This isn’t a joke,” she said.

Her head had struck the bottom of the pool and shattered two vertebrae. In particular, the fracture of her C6 vertebra severed her spinal cord and left her permanently paralyzed from the chest down. She would never walk again.

“We are just so happy…”

One year later, Rachelle Friedman became Rachelle Chapman as she married her new husband. She decided to share some of her own thoughts on the whole experience during an online question-and-answer session in 2013. 1

She started by discussing some of the challenges you might expect. It was hard to find a job that could accommodate her physical disabilities. It could be frustrating and uncomfortable to deal with the nerve pain.

But she also shared a variety of surprisingly positive answers. For example, when asked if things changed for the worse she said, “Well things did change, but I can’t say in a bad way at all.” Then, when asked about her relationship with her husband she said, “I think we are just so happy because my injury could have been worse.”

How is it possible to be happy when everything in life seems to go wrong? As it turns out, Rachelle’s situation can reveal a lot about how our brains respond to traumatic events and what actually makes us happy.

The Surprising Truth About Happiness

There is a social psychologist at Harvard University by the name of Dan Gilbert. 2 Gilbert’s best-selling book, Stumbling on Happiness, discusses the many ways in which we miscalculate how situations will make us happy or sad, and reveals some counterintuitive insights about what actually does make us happy.

One of the primary discoveries from researchers like Gilbert is that extreme inescapable situations often trigger a response from our brain that increases positivity and happiness.

For example, imagine your house is destroyed in an earthquake or you suffer a serious injury in a car accident and lose the use of your legs. When asked to describe the impact of such an event most people talk about how devastating it would be. Some people even say they would rather be dead than never be able to walk again.

But what researchers find is that when people actually suffer a traumatic event like living through an earthquake or becoming a paraplegic their happiness levels are nearly identical six months after the event as they were the day before the event.

How can this be?

The Impact Bias

Traumatic events tend to trigger what Gilbert refers to as our “psychological immune systems.” Our psychological immune systems promote our brain’s ability to deliver a positive outlook and happiness from an inescapable situation. This is the opposite of what we would expect when we imagine such an event. As Gilbert says, “People are not aware of the fact that their defenses are more likely to be triggered by intense rather than mild suffering. Thus, they mis-predict their own emotional reactions to misfortunes of different sizes.”

This effect works in a similar way for extremely positive events. For example, consider how it would feel to win the lottery. Many people assume that winning the lottery would immediately deliver long-lasting happiness, but research has found the opposite.

In a very famous study published by researchers at Northwestern University in 1978 it was discovered that the happiness levels of paraplegics and lottery winners were essentially the same within a year after the event occurred. You read that correctly. One person won a life-changing sum of money and another person lost the use of their limbs and within one year the two people were equally happy. 3

It is important to note this particular study has not been replicated in the years since it came out, but the general trend has been supported again and again. We have a strong tendency to overestimate the impact that extreme events will have on our lives. Extreme positive and extreme negative events don’t actually influence our long-term levels of happiness nearly as much as we think they would. 4

Researchers refer to this as The Impact Bias because we tend to overestimate the length or intensity of happiness that major events will create. The Impact Bias is one example of affective forecasting, which is a social psychology phenomenon that refers to our generally terrible ability as humans to predict our future emotional states. 5

Where to Go From Here

There are two primary takeaways I have from The Impact Bias.

First, we have a tendency to focus on the thing that changes and forget about the things that don’t change. When thinking about winning the lottery, we imagine that event and all of the money that it will bring in. But we forget about the other 99 percent of life and how it will remain more or less the same.

We’ll still feel grumpy if we don’t get enough sleep. We still have to wait in rush hour traffic. We still have to workout if we want to stay in shape. We still have to send in our taxes each year.

It will still hurt when we lose a loved one. It will still feel nice to relax on the porch and watch the sunset. We imagine the change, but we forget the things that stay the same.

Second, a challenge is an impediment to a particular thing, not to you as a person. In the words of Greek philosopher Epictetus, “Going lame is an impediment to your leg, but not to your will.” We overestimate how much negative events will harm our lives for precisely the same reason that we overvalue how much positive events will help our lives. We focus on the thing that occurs (like losing a leg), but forget about all of the other experiences of life.

Writing thank you notes to friends, watching football games on the weekend, reading a good book, eating a tasty meal. These are all pieces of the good life you can enjoy with or without a leg. Mobility issues represent but a small fraction of the experiences available to you. Negative events can create task-specific challenges, but the human experience is broad and varied.

There is plenty of room for happiness in a life that may seem very foreign or undesirable to your current imagination.

For more on the fascinating ways in which our brain creates happiness, read Dan Gilbert’s book Stumbling on Happiness (ebook | audiobook).

Footnotes

Friedman’s Ask Me Anything post on Reddit: I am Rachelle Friedman Chapman aka “The Paralyzed Bride”.

This Dan Gilbert is not to be confused with the Dan Gilbert who owns the Cleveland Cavaliers.

“Lottery winners and accident victims: is happiness relative?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978, Vol. 36, No. 8, 917-927.

This is obvious, but I feel compelled to point out that individual experiences will differ. It’s quite possible you know a lottery winner that loves their life or a paraplegic that is constantly unhappy. The point of these studies (and the Impact Bias in general) is not to label the experience everyone will have, but to point out that we drastically overestimate the effect that extreme events have on our lives. In any particular situation, your mileage may vary.

Affective forecasting is sometimes referred to as hedonic forecasting. Same thing, different name.

September 3, 2015

Shoshin: This Zen Concept Will Help You Stop Being a Slave to Old Behaviors and Beliefs

I played baseball for 17 years of my life. During that time, I had many different coaches and I began to notice repeating patterns among them.

Coaches tend to come up through a certain system. New coaches will often land their first job as an assistant coach with their alma mater or a team they played with previously. After a few years, the young coach will move on to their own head coaching job where they tend to replicate the same drills, follow similar practice schedules, and even yell at their players in a similar fashion as the coaches they learned from. People tend to emulate their mentors. 1

This phenomenon—our tendency to repeat the behavior we are exposed to—extends to nearly everything we learn in life.

Your political or religious beliefs are mostly the result of the system you were raised in. People raised by Catholic families tend to be Catholic. People raised by Muslim families tend to be Muslim. Although you may not agree on every issue, your parents political attitudes tend to shape your political attitudes. The way we approach our day-to-day work and life is largely a result of the system we were trained in and the mentors we had along the way. At some point, we all learned to think from someone else. That’s how knowledge is passed down.

Here’s the hard question: Who is to say that the way you originally learned something is the best way? What if you simply learned one way of doing things, not the way of doing things?

Consider my baseball coaches. Did they actually consider all of the different ways of coaching a team? Or did they simply mimic the methods they had been exposed to? The same could be said of nearly any area in life. Who is to say that the way you originally learned a skill is the best way? Most people think they are experts in a field, but they are really just experts in a particular style.

In this way, we become a slave to our old beliefs without even realizing it. We adopt a philosophy or strategy based on what we have been exposed to without knowing if it’s the optimal way to do things.

Shoshin: The Beginner’s Mind

There is a concept in Zen Buddhism known as shoshin, which means “beginner’s mind.” Shoshin refers to the idea of letting go of your preconceptions and having an attitude of openness when studying a subject.

When you are a true beginner, your mind is empty and open. You’re willing to learn and consider all pieces of information, like a child discovering something for the first time. As you develop knowledge and expertise, however, your mind naturally becomes more closed. You tend to think, “I already know how to do this” and you become less open to new information.

There is a danger that comes with expertise. We tend to block the information that disagrees with we learned previously and yield to the information that confirms our current approach. We think we are learning, but in reality we are steamrolling through information and conversations, waiting until we hear something that matches up with our current philosophy or previous experience, and cherry-picking information to justify our current behaviors and beliefs. Most people don’t want new information, they want validating information.

The problem is that when you are an expert you actually need to pay more attention, not less. Why? Because when you are already familiar with 98 percent of the information on a topic, you need to listen very carefully to pick up on the remaining 2 percent. 2

As adults our prior knowledge blocks us from seeing things anew. To quote zen master Shunryo Suzuki, “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.”

How to Rediscover Your Beginner’s Mind

Here are a few practical ways to rediscover your beginner’s mind and embrace the concept of shoshin.

Let go of the need to add value. Many people, especially high achievers, have an overwhelming need to provide value to the people around them. On the surface, this sounds like a great thing. But in practice, it can handicap your success because you never have a conversation where you just shut up and listen. If you’re constantly adding value (“You should try this…” or “Let me share something that worked well for me…”) then you kill the ownership that other people feel about their ideas. At the same time, it’s impossible for you to listen to someone else when you’re talking. So, step one is to let go of the need to always contribute. Step back every now and then and just observe and listen. For more on this, read Marshall Goldsmith’s excellent book What Got You Here Won’t Get You There (audiobook).

Let go of the need to win every argument. A few years ago, I read a smart post by Ben Casnocha about becoming less competitive as time goes on. In Ben’s words, “Others don’t need to lose for me to win.” This is a philosophy that fits well with the idea of shoshin. If you’re having a conversation and someone makes a statement that you disagree with, try releasing the urge to correct them. They don’t need to lose the argument for you to win. Letting go of the need to prove a point opens up the possibility for you to learn something new. Approach it from a place of curiosity: Isn’t that interesting. They look at this in a totally different way. Even if you are right and they are wrong, it doesn’t matter. You can walk away satisfied even if you don’t have the last word in every conversation.

Tell me more about that. I have a tendency to talk a lot (see “Providing Too Much Value” above). Every now and then, I’ll challenge myself to stay quiet and pour all of my energy into listening to someone else. My favorite strategy is to ask someone to, “Tell me more about that.” It doesn’t matter what the topic is, I’m simply trying to figure out how things work and open my mind to hearing about the world through someone else’s perspective.

Assume that you are an idiot. In his fantastic book, Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb writes, “I try to remind my group each week that we are all idiots and know nothing, but we have the good fortune of knowing it.” The flaws discussed in this article are simply a product of being human. We all have to learn information from someone and somewhere, so we all have a mentor or a system that guides our thoughts. The key is to realize this influence.

We are all idiots, but if you have the privilege of knowing that, then you can start to let go of your preconceptions and approach life with the openness of a beginner.

Shoshin. 3

Footnotes

Occasionally, you’ll hear about this system-focused behavior in the elite levels of sport as well. “He coached under Bill Belichick and learned the Patriots’ system.” Or, “He was an assistant under Urban Meyer and learned his way of doing things.”

Hat tip to Richard W., a reader of this website, for explaining to me why you need to pay more attention once you are an expert. He noticed that after reading many books on a certain topic, you know it so well that you can’t just skim through similar books. Most of the information will be repetitive, so you need to read line-by-line to discover the one insight you haven’t heard before.

Thanks to Sam Yang for his article on shoshin, which influenced my thinking.

September 1, 2015

Why Old Ideas Are a Secret Weapon

A series of explosions shook the city of St. Louis on March 16, 1972. The first building fell to the ground at 3 p.m. that afternoon. In the months that followed, more than 30 buildings would be turned to rubble.

The buildings that were destroyed were part of the now infamous housing project known as Pruitt-Igoe. When the Pruitt-Igoe housing project opened in 1954 it was believed to be a breakthrough in urban architecture. Spanning 57 acres across the north side of St. Louis, Pruitt-Igoe consisted of 33 high-rise buildings and provided nearly 3,000 new apartments to the surrounding population.

Pruitt-Igoe was designed with cutting-edge ideas from modern architecture. The designers emphasized green spaces and packed residents into high-rise towers with beautiful views of the surrounding city. The buildings employed skip-stop elevators, which only stopped at the first, fourth, seventh, and tenth floors. (Architects believed that forcing people to use the stairs would lesson the foot traffic and congestion in the building.) The buildings were outfitted with “unbreakable” lights that were covered in metal mesh and intended to reduce vandalism. The floors featured communal garbage chutes and large windows to brighten the corridors with natural light.

On paper, Pruitt-Igoe was a testament to modern engineering. In practice, the project was a disaster.

The Pruitt-Igoe Failure

Once the troublemakers of the neighborhood heard that the light fixtures were supposedly unbreakable, they accepted the challenge and threw water on the lights until they overheated and burnt out. 1

Next, they busted the garbage chutes and shattered the windows. According to one report, the bright new corridors had so many broken windows that “it was possible to see straight through to the other side.” 2

The St. Louis Housing Authority had planned to use rental incomes to pay for the maintenance of the buildings. In the years after the massive project opened, the population of St. Louis began to drop as people moved out of the city. With fewer tenants than expected and increasing rates of vandalism, the buildings were left unfixed.

Soon the modern design of Pruitt-Igoe began to accelerate its downfall. Suddenly, the skip-stop elevators became a danger to well-behaved citizens who were forced to walk through additional corridors and risky stairways just to get into and out of their apartments. As criminal activity rose, more things were broken, more people moved away, and less money came in.

In 1972, less than 20 years after the project had opened, the St. Louis Housing Authority scheduled a demolition and blew up the entire $36 million complex. 3

This iconic image of the Pruitt-Igoe demolition with the St. Louis arch in the background became a symbol of the failure of modern architecture and urban renewal. (Image Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development)

This iconic image of the Pruitt-Igoe demolition with the St. Louis arch in the background became a symbol of the failure of modern architecture and urban renewal. (Image Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development)Old Ideas Are Undervalued

The sprawling 33-building, 57-acre layout of Pruitt-Igoe ignored the traditional knowledge about how cities grow and develop. Nearly every thriving and successful city on our planet was built organically and unpredictably. Buildings popped up as needed. City blocks expanded gradually.

There is a reason we tend to undervalue old ideas:

At first glance, we just see an idea that has been around for a long time. We incorrectly assume that familiar ideas provide average results. “Everyone does it this way, so it can’t be that great … right?”

What we fail to understand is that the fundamentals are not merely a collection of good ideas. The fundamentals are a collection of good ideas that outlasted thousands of bad ideas.

For example:

Fitness. Decades have seen the rise and fall of countless exercise fads. New training styles come into vogue, only to be replaced by another a few years later. In our quest to get fit we chase the latest and greatest offering even though boring fundamentals like lifting weights three times per week or going for a daily walk have outlasted all the previous fads.

Entrepreneurship. Simple fundamentals like making more sales calls can be the difference between success and failure as an entrepreneur. As Patrick McKenzie, CEO of Starfighter, says “Our secret weapon is patient execution of what everyone knows they should be doing, because that actually is a competitive barrier.”

Reading. Half of this year’s best-selling books are filled with ideas that may seem intelligent today, but will be proven wrong in the near future. Only a handful will still be read consistently a decade from now. These books—the ones that stand the test of time—are the ones you want to be reading because they are filled with ideas that last. This is why old books can provide incredible value.

The Power of Inherited Knowledge

Across the street from Pruitt-Igoe was more traditional housing complex named Carr Square Village. Unlike Pruitt-Igoe, Carr Square Village was a smaller, low-rise complex and featured more traditional designs. It was built 12 years before Pruitt-Igoe, but despite its older age, Carr Square Village outlasted Pruitt-Igoe and boasted lower crime and vacancy rates all while being in the same neighborhood.

Is this evidence that we should abandon creative thinking and innovation in the name of sticking to the fundamentals? Of course not. But I do believe the Pruitt-Igoe story is one example of our tendency to undervalue inherited knowledge.

Furthermore, I’d like to propose that sometimes the creative thing to do is to actually practice the fundamentals more consistently than everyone else. Most people don’t fully use the knowledge they already have. As I have written previously, “Everybody already knows that” is very different from “Everybody already does that.”

Footnotes

“The Pruitt-Igoe Myth” by 99 Percent Invisible. January 6, 2012.

“Why the Pruitt-Igoe housing project failed.” The Economist. October 15, 2011.

A 1991 paper titled, “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth” by Katherine Bristol of the University of California, Berkeley discusses the various factors that led to the downfall of the housing complex. The modern architecture, which is used in this article as an example of undervaluing proven ideas, was just one of the reasons for the failure of the project. Bristol’s paper sparked a recent documentary of the same name.