L.D. Colter's Blog, page 11

April 5, 2017

Writing Tips 101.07 - Plot-Driven vs Character-Driven Storytelling

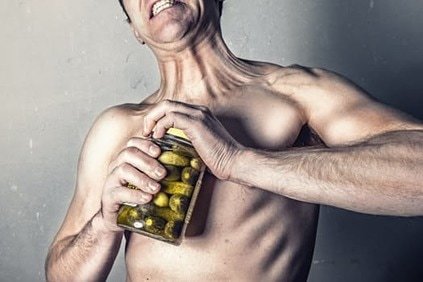

Photo from Pexels The terms are pretty self-explanatory, even if you’re not already familiar with them, but here’s a quick definition (mine, at any rate): character-driven means that your story delves into the emotions, goals, and internal conflicts of your characters (your protagonist and antagonist at the least, and hopefully your other characters as well), and uses the action or plot of the story as a framework for the characters to change, grow, or learn. Plot-driven stories, as you can guess, have action and external conflict as the central driving force. The characters can (and should) have individual traits and even internal conflict, but if you decide halfway through your manuscript to trade out Captain Stanley Jones and his set of issues for Captain Keesha Moews and her different set of issues, your story will probably still hold together because the plot twists and conflicts are the core element. For the picture above, you could write a compelling story about either the training, planning, and execution of the stunt, or about the personality, motives, and drive of a person who is drawn to take extreme risks. All stories have (or should have) both character and plot arcs, but the emphasis determines which kind of story you’re writing.

Photo from Pexels The terms are pretty self-explanatory, even if you’re not already familiar with them, but here’s a quick definition (mine, at any rate): character-driven means that your story delves into the emotions, goals, and internal conflicts of your characters (your protagonist and antagonist at the least, and hopefully your other characters as well), and uses the action or plot of the story as a framework for the characters to change, grow, or learn. Plot-driven stories, as you can guess, have action and external conflict as the central driving force. The characters can (and should) have individual traits and even internal conflict, but if you decide halfway through your manuscript to trade out Captain Stanley Jones and his set of issues for Captain Keesha Moews and her different set of issues, your story will probably still hold together because the plot twists and conflicts are the core element. For the picture above, you could write a compelling story about either the training, planning, and execution of the stunt, or about the personality, motives, and drive of a person who is drawn to take extreme risks. All stories have (or should have) both character and plot arcs, but the emphasis determines which kind of story you’re writing.There’s no right or wrong. My writing is character-driven, and I know plenty of successful writers who write plot-driven novels. As the writer, it’s up to you what sort of story you want to tell and how you want to tell it. For those seeking traditional publishing, though, it’s good to know your markets and their preferences. (The same goes for my advice throughout this series: write how you want, but do it with intention and from a place of knowledge rather than through trial and error.) Approach it the same as last week’s tip on atmosphere - think about the kind of story you want to tell before you start, so that you can gear toward a character-driven tale or a plot-driven one from the start. When you’re finished (if you plan to send it to publishers - either via an agent or directly) choose your markets by reading submission guidelines thoroughly, looking at other books and stories that the market has published, and sending to the ones looking for what you write. And whether you plan to self-publish or submit to traditional publishers - read! I said it last week and I’ll say it again. Read a lot. Read well-written books that keep you excited about reading and writing. Take a look back at your favorite books - are they character-driven or are they plot-driven? Tell your own unique story for readers to discover, but write what you love!

Published on April 05, 2017 11:32

March 27, 2017

Writing Tips 101.06 - Voice

Photo from Pexels We’re at the halfway point of Writing Tips 101 now and - as mentioned last week - we’re transitioning from micro tips about sentence level structure to macro concepts that should be consistently applied through the entire story or novel, things like voice.

Photo from Pexels We’re at the halfway point of Writing Tips 101 now and - as mentioned last week - we’re transitioning from micro tips about sentence level structure to macro concepts that should be consistently applied through the entire story or novel, things like voice.Voice is more than just what the characters say in dialogue, it’s how they say it. It’s likely there are people you would know by their texting even if their name was hidden because their manner of speech and turns of phrase would give them away. In the same way that people you know don’t all speak the same way, you need to make sure that your characters don’t all sound alike. Dialogue has never been the easiest part of writing for me, but I’ve found that the better I know my characters, the more distinctive their voices become and the more naturally the dialogue flows (for them and me). Different writers have different methods of getting to know their characters - some people interview a character by literally writing out a set of questions to ask the character about themselves and then write out the answers. Character sheets can also be a good method, and templates can be found online or in writing tools like Scrivener. Some writers base character or speech traits or on people they’ve met or observed in public (remember that it’s polite to file the serial numbers off beyond just changing the name unless you have a person’s permission to use them as a character). However you develop your characters, make sure they have depth, and feel like real people instead of cardboard cutouts or clichés. You don’t have to work in every detail that you know about your character and their past and personality into the story, but if you know it, it will come out in their mannerisms, reactions, natural sounding dialogue, and in their distinctive voice.

Another tool for learning how to write effective dialogue and voice is to read as much as possible. In fact, I can’t emphasize the importance enough that, as writers, you should be reading as much as you possibly can to help you constantly grow in all aspects of your writing. Reading a range of styles and expertise is good for seeing what works and what doesn’t, but be sure read far more of what works well and study it as you read to see why it works. You can even do a search to find authors known for certain strengths, such as Elmore Leonard and Douglas Adams often praised for exceptional talent with dialogue.

Published on March 27, 2017 20:57

March 23, 2017

Writing Tips 101.05 - Atmosphere

Photo from Pexels Apologies that this post is late, but the book release overshadowed it on Tuesday and a big storm here knocked out power for most of the morning today.

Photo from Pexels Apologies that this post is late, but the book release overshadowed it on Tuesday and a big storm here knocked out power for most of the morning today.Okay, for a quick recap: Tip 01 began with an overview of show vs. tell, Tip .02 discussed weak words, Tip .03 covered details (too much and too little), and Tip .04 differentiated between description and descriptors. This week's topic - atmosphere and tone - is a good transitional topic to move from talking about sentence-level construction that captures and engages readers, into larger concepts of telling a story. No matter how epic or complex your story is, it is still built sentence by sentence, but the detail and descriptions and emotions you create in those sentences will combine to give the work as a whole a sense of atmosphere.

Every author has a different process to get from concept to finished story or novel. For me, the very first step is nearly always atmosphere. (BTW - Not everyone defines atmosphere, tone, and mood the same way. I tend to refer to the overall feel as tone, because I think in terms of setting the tone for the novel or short story. Most people would call this atmosphere, or perhaps mood, and say that tone refers to smaller sections of the story and can change with the circumstances.)

Sometimes I can put the atmosphere I want to evoke into words - Gothic, dark, noir. Sometimes I can’t and I have to settle for shooting for duplicating something I feel. For anyone interested, the next few steps of story creation for me - steps which often occur nearly simultaneously with defining the atmosphere I want - are a sense of the protagonist and often an image of the location (real or imagined). Next comes the inciting incident and a general feel for the arc of the story (in other words, a vague - or sometimes defined - idea of the beginning and end). The point is, for me, atmosphere is such an important component of story creation that it usually comes to me before anything else. Not that it can’t change. I once started writing what I thought was a humorous flash fiction piece and it quickly let me know it wanted to be horror instead. I had to rethink all the details, from setting details to voice, to change it. I wish I still had the earliest version of that story around, because comparing the first draft paragraph with the final version might have helped show how changing just a few words can affect atmosphere, tone, and or mood. Instead, here are a couple of excerpts from well-known authors who are masters of their craft.

“Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun.

Orbiting this at a distance of roughly ninety-two million miles is an utterly insignificant little blue green planet whose ape-descended life forms are so amazingly primitive that they still think digital watches are a pretty neat idea.”

-Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy

Compare that atmosphere to this:

“The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.

The desert was the apotheosis of all deserts, huge, standing to the sky for what looked like eternity in all directions. It was white and blinding and waterless and without feature save for the faint, cloudy haze of the mountains which sketched themselves on the horizon and the devil-grass which brought sweet dreams, nightmares, death. An occasional tombstone sign pointed the way, for once the drifted track that cut its way through the thick crust of alkali had been a highway.”

-Stephen King, The Gunslinger: The Dark Tower I

Setting your atmosphere early on and maintaining it throughout your story will add essential depth and feeling, and bringing out the tone or mood within the scenes and dialogue will increase this effect for the reader.

Published on March 23, 2017 20:36

March 21, 2017

Book Release For A Borrowed Hell!

The day has come at last. My debut novel has been released by Shirtsleeve Press. I love the stunning cover I received from the publisher and the first editorial review of the book from author Nathan Lowell:

The day has come at last. My debut novel has been released by Shirtsleeve Press. I love the stunning cover I received from the publisher and the first editorial review of the book from author Nathan Lowell:"Colter has created a world equal parts magical realism, inner journey, and psychological horror. Carlos Castaneda meets Thomas Covenant in a well crafted tale of fear, doubt, and redemption as July Davish pursues his inner demons in order to face them down and break the cycle of anger and frustration that has held his life hostage. Recommended."

-Nathan Lowell, Author of the Tanyth Fairport Adventures and the Solar Clipper Series

Chronologically, this was the second novel I wrote, and the start of my road into contemporary magic realism. The novel is a bit slipstream and arguments could be made for it being alternate world (parts of it, anyway) or perhaps even literary-genre (with themes similar to Jason Gurley's "Eleanor"). An early reviewer mentioned a "Jonathan Livingston Seagull" vibe. My favorite thing about this novel is the characters - July and Val and Pat flowed out onto the pages as if I was transcribing their story more than creating it, and I think they remain some of the most vivid and real characters I've ever written.

I hope you'll hop over to Amazon to check out the full description and maybe get the book. If you do, I'd love to hear what you think!

Published on March 21, 2017 07:22

March 17, 2017

2017 Anthology of Campbell-Eligible Authors

Shirtsleeve Press - the press that is publishing my debut novel "A Borrowed Hell" - has taken over the hefty project of publishing the free, annual anthology of Campbell Award-eligible authors. My eligibility ended last year, but I remember how grateful I was when editors S. L Huang and Kurt Hunt stepped up in the second of my two years of eligibility and revived the project that M. David Blake and Rampant Loon Press had begun and discontinued.

Shirtsleeve Press - the press that is publishing my debut novel "A Borrowed Hell" - has taken over the hefty project of publishing the free, annual anthology of Campbell Award-eligible authors. My eligibility ended last year, but I remember how grateful I was when editors S. L Huang and Kurt Hunt stepped up in the second of my two years of eligibility and revived the project that M. David Blake and Rampant Loon Press had begun and discontinued.Shirtsleeve's Quanta imprint (their SciFi imprint - though stories can be any sub-genre of SFF) will be publishing the book for the foreseeable future. Below, are the details and the link directly from the Quanta announcement:

Event Horizon 2017

Quanta Books

An anthology of authors eligible for the John W.Campbell Award for Best New Writer.

The John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer is presented annually at WorldCon to an outstanding author whose first professional work of science fiction or fantasy was published within the previous two years. This anthology includes over 75 authors and nearly 400,000 words of fiction. A resource of amazing new writers for both Hugo Award voters and those interested in seeing the brightest new lights of fantasy and science fiction, Event Horizon is exclusively available until July 15, 2017.

Published March 13, 2017

Download a free copy here

Published on March 17, 2017 09:34

March 14, 2017

Writing Tips 101.04 - Descriptors vs Description

Photo from Pexels Last week I talked about detailed descriptions; this time I want to talk about descriptors. Here's the Reader's Digest version: description is good. Descriptors, not so much.

Photo from Pexels Last week I talked about detailed descriptions; this time I want to talk about descriptors. Here's the Reader's Digest version: description is good. Descriptors, not so much.Description is a phrase or block of prose that describes something (or many things). Descriptors are words that summarize description. The most common descriptors are adjectives and adverbs. Again, the biggest reason for being conscious of overusing descriptors goes back to showing vs telling. Well done description and detail will show your story, where using descriptors is a shortcut to tell your reader what you want to convey. Take dialogue for starters:

“You never listen to me,” she said angrily.

Adverbs are often recognizable by their ‘ly’ endings - “angrily” in this case. This statement tells the reader the speaker is angry, but it’s shortcut writing for showing what’s really going on here.

“You never listen to me,” she said, striding around to the front of the couch and standing, hands on hips, blocking the TV, daring him to tell her to move.

Now, technically, “striding” is a descriptor the way the verb is used here. It describes how she is moving, which in turn describes how she is feeling, but it’s being used in a larger frame of description. As I said in week 2 when talking about eliminating weak words (Writing Tips 101.02), beware of stripping too much out of your prose as it can leave it sterile and unnatural sounding. Prose needs to flow. Ideally, if done well, it will be largely invisible, replaced by sounds, smells, and images in the reader’s mind. What you don’t want is for shortcut words, weak words, long narrative, and other crutches to pull your reader out of the story.

Just as adverbs modify verbs, adjectives modify or describe nouns, and in the same way, they can be redundant, unnecessary, and telling. Don't tell your readers that the "scary ghost reached for the last student running from the old mansion." It's a ghost. It's reaching for someone. They're running. We don't need the adverb "scary" to modify the ghost.

A quick search will turn up many, many articles on the pitfall of adverbs and adjectives - here's one from Writer's Digest if you'd like to see more examples: Don’t Use Adverbs and Adjectives to Prettify Your Prose

Published on March 14, 2017 08:10

March 8, 2017

Literary-Genre: One Writer's Definition

Definitions for literary, mainstream, and commercial/genre are slippery, and not everyone agrees on every point. Literary, at its roots, simply means having to do with words, and yet, many people classify fiction into two separate camps: literary and commercial. My personal definition is this: Fiction is an umbrella term for stories about imaginary events and/or people. Genre is separated into styles that adhere to reader expectations. Literary is one of the many genres of fiction.

Definitions for literary, mainstream, and commercial/genre are slippery, and not everyone agrees on every point. Literary, at its roots, simply means having to do with words, and yet, many people classify fiction into two separate camps: literary and commercial. My personal definition is this: Fiction is an umbrella term for stories about imaginary events and/or people. Genre is separated into styles that adhere to reader expectations. Literary is one of the many genres of fiction.So what then is literary-genre? I think it starts with a commercial framework (science fiction, fantasy, mystery, romance, historical fiction, or thriller) but either the prose becomes as much a part of the story as the plot (sometimes slowing the pacing more than action-oriented readers are used to), or the themes emphasize some aspect of the human condition rather than focusing solely on the plot elements. (This is not to say that commercial fiction isn't character driven, it most often is these days, just that heavier themes associated more with literary fiction are generally not delved into as deeply.) Though there’s less literary-genre published than straight literary or straight genre, there’s still plenty out there—both in movies and novels.

I’ve found some of my favorite novels in that gray space between genres. I discovered Kurt Vonnegut in my high school library and read every book of his they had. (I also read Catch-22 in high school, which wasn’t SFF but weird enough to nearly qualify - and the same could be said for my favorite literary author, John Irving.) Books like Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale (or movies like Mystic River, The Green Mile, and many others) may be categorized as literary despite their fantasy or science fiction elements. Books such as the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Watership Down, The Once and Future King, and many others may be shelved in SFF but referred to as literary. In my 20’s I loved John Crowley’s Little Big, Michael Moorcock’s Elric novels, Gene Wolfe’s New Sun books, and all of Ursula Le Guin. In the past decade, I discovered and devoured whole collections by China Mieville, Neil Gaiman, and Tim Powers. I’ve enjoyed Gregory Maguire’s Wicked, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, and Jeff Vandermeer’s Area X trilogy. In just the past year I’ve read Samuel Delany’s Dhalgren, Jason Gurley’s Eleanor, Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus, Michael Cisco’s The Narrator, and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

My first novel, A Borrowed Hell, will be released in just over a week by Shirtsleeve Press. I don't know how individual readers will classify it but, in my opinion, the plot is more commercial than literary, the prose falls somewhere in-between, and the themes of the story are more literary than commercial. Here’s a little bit about it:

Fate has dealt July Davish a lifetime of nothings; no happy childhood, no lasting relationships, and now, no job. His mantra of perseverance has gotten him this far but, faced with losing his home, July finds himself heading for the same road of self-destruction the rest of his family followed. When a nearby car accident sends him diving for safety he lands instead on a far different road, one in a bizarrely deserted San Francisco. July is willing to do anything to end his bizarre world-hopping, right up until he learns the price: reliving a past he's tried his whole life to forget. He’s not sure his sanity can take revisiting the neglect and grief that surrounded him growing up. Not even to get back to his own world, a woman he’s falling in love with, and a life he finally cares about.

Despite my love of words and of literary-leaning SFF, I’m not normally a reader of straight literary. I’ve found that unless a book has an element of weird, it just isn’t likely to hold my interest. And just because I prefer literary leaning SFF, I’m not certainly implying anything negative about commercial prose or themes. I’ve read and enjoyed plenty over the years. If you’re like me and enjoy a little bit of both in your reading, I hope you’ll check out A Borrowed Hell.

Published on March 08, 2017 23:00

March 5, 2017

Writing Tips 101.03 Detail - Too Much or Too Little?

Published on March 05, 2017 14:42

February 28, 2017

Writing Tips 101.02 - Weak Words

Photo from Pexels Last week I reviewed the concept of writing with immediacy to put the reader in the character’s skin, and gave an example of “show vs tell” when writing narrative. Another subtle habit that can create distance rather than immediacy and lead you into 'telling' is using weak words - things like passive verbs, weak verbs, filter words, and phrases that serve no purpose.

Photo from Pexels Last week I reviewed the concept of writing with immediacy to put the reader in the character’s skin, and gave an example of “show vs tell” when writing narrative. Another subtle habit that can create distance rather than immediacy and lead you into 'telling' is using weak words - things like passive verbs, weak verbs, filter words, and phrases that serve no purpose.First up: passive verbs. Defining specific parts of speech can get involved - not to mention boring - pretty fast. Let’s keep it simple. Verbs are your action words - or at least in most fiction writing, they should be. When caught up in getting words on the page, though, it can be easy to fall into using passive verbs instead of active ones. What’s the difference? The subject is either doing the action or being acted upon. When the subject is performing the action, the construction is active. When the subject is acted upon, the construction is passive. A list of examples can be found here:

examples-of-active-and-passive-voice.html

Weak Verbs: In the example phrases at the link above, you’ll notice a lot of ‘was’ and ‘were’ and ‘had done’ (or in present tense, is, are, be), etc. It doesn’t mean that those verbs are always passive (it depends on the construction of the sentence, right?), but they are always weak verbs. Best to avoid them when you can, and find something more interesting. (Stephen King in his book On Writing calls this punching up his verbs.)

Tip: be aware of gerund useage (-ing words) as they can lead you into passive words. ‘She was running... ’ vs ‘She ran... '

writers-toolbox/gerunds-and-participles-avoid-ing-words/

simplewriting.org/are-ing-words-bad/

Another pitfall to watch for is filter words, (he saw, she thought, they seemed, zhe wondered). There’s an article here by Chuck Palahniuk that has some great examples of how to change ‘telling’ filter words into ‘showing’.

thought-verbs-by-chuck-palahniuk

Lastly, watch out for waffling in your prose (my word for not getting to the point). It’s another way to weaken a sentence and add unnecessary words. She got a bit nervous, he kind-of wanted to go...: In real life, you do or you don’t, right? Try this instead: She felt nervous, but [did something about it]. He wanted to go, but decided [whatever].

One caution here: using tighter writing, active verbs, avoiding filter words, and cutting down on gerunds will increase the immediacy in your writing. However, the prose still has to flow well and sound natural. Changing every sentence to “She called (and told him to get ready)...He packed (for the trip)... They left (from her apartment)... They boarded (the bus, plane, whatever) - to make it more active will, instead, make your writing stilted and monotonous. Be sure to mix up the constructions and sentence lengths. Use the occasional passive verbs, weak verb, filter word, and gerunds where they’re needed - just be sure it’s a conscious choice and done for a good reason. The goal is a good reading experience, not a story so stripped down that it becomes lifeless.

Okay, I’m going to make up an example on the spot to try and illustrate these concepts in prose. See if you can spot the weak words and phrases.

Mara felt uncertain about Troy’s plan, and began to try and think of another way to find the rogue vampire. She was flipping through an ancient text on Hungarian rituals when the phone rang. Getting up to answer it, she thought she spotted a shadow moving outside the window. It slid away, and she found she was so scared that she couldn’t speak.

“Hello?” Troy said.

Nothing overtly wrong or unusual about the example above, but compare it to this:

The last time Mara followed Troy’s advice they’d found themselves running for their lives; this time she planned to do her research on the rogue vampire before setting out. She pulled a volume of Laszlo Fodor’s “Nocturna” from a shelf by the couch and settled back into her favorite overstuffed recliner. Picking a page at random, she opened the book to an old illustration of a vampire sucking the blood of a young woman in his arms. She stared in shock at the face in the illustration and the striking resemblance to the vampire they tracked. The phone rang, pulling her out of her contemplation with a start. She closed the book and hurried to the small phone table by the window, cutting off the insistent, European double-ring when she lifted the receiver. A movement out the window caught the corner of her eye. She focused on it and made out a formless shadow slithering into the nearby bushes. Her voice froze in her throat.

“Hello?” Troy said.

Yes, I’ve added a lot, but as I mentioned last week, showing will nearly always take more words than telling. Details and specifics are an important part of immersing the reader in your world.

Find a paragraph of writing you’ve done that has a few weak words in it and try a re-write. I’ll bet you’ll like the result.

Published on February 28, 2017 07:08

February 23, 2017

New, Old Mythology

As an author who is currently writing a series of books based on mythologies around the world, I love educating myself about different cultural beliefs. Myths can be either allegorical stories, or a living religion based on stories or narratives that embody the belief or beliefs of a group of people. Some myths are well-known and well-preserved, such as Greek mythology; other myths have largely been lost to us. Some fall in between, like Norse mythology - where a handful of the gods are very well known, such as Odin, Thor, and Loki, yet the majority of the pantheon and their stories have vanished over time. Because so many tales have been lost, it's heartening to see the effort some people are making to preserve the ones that still exist.

As an author who is currently writing a series of books based on mythologies around the world, I love educating myself about different cultural beliefs. Myths can be either allegorical stories, or a living religion based on stories or narratives that embody the belief or beliefs of a group of people. Some myths are well-known and well-preserved, such as Greek mythology; other myths have largely been lost to us. Some fall in between, like Norse mythology - where a handful of the gods are very well known, such as Odin, Thor, and Loki, yet the majority of the pantheon and their stories have vanished over time. Because so many tales have been lost, it's heartening to see the effort some people are making to preserve the ones that still exist.

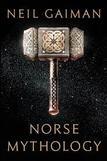

I recently read Neil Gaiman's new book, Norse Mythology. I've tried in the past to research Norse myths on my own, and I can say it wasn't easy. Unlike my slogs through textbook-like publications and the translations of the original Prose Edda and Poetic Edda, Gaiman's book is an organized, easy to read, retelling of the major Norse myths still available. I'd recommend it to anyone interested in the Norse gods, or mythology in general.

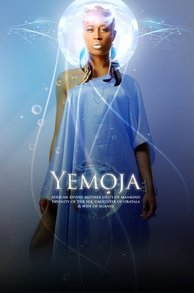

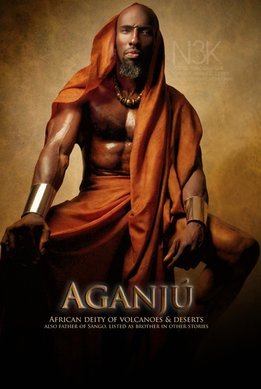

Just today, I ran across this old post by Buzzfeed, with a gallery of beautiful artwork of the Orishas - gods of the Yoruba-speaking peoples (primarily West Africa, mainly Nigeria). You can check out the art by James C. Lewis and the descriptions of the deities here.

Published on February 23, 2017 11:38

Photo from

Photo from