Adam Fenner's Blog, page 20

October 20, 2024

Do not weep

Santable

Do not weep on my grave,

You are my strength.

Think of life without me,

As you started your life on your own.

Depart from me,

As you have to carry your time to your own.

Do not weep,

Remember we were together,

We dreamed together,

We shared affairs to multiply.

Now grief is yours,

Your grievances are with me.

You swim alone alongside,

You strive,

As you grew alone,

You prepared yourself for me.

Do not weep,

Now our meeting is in memory.

Do not weep,

Leave to live,

Dream to be more alive,

Thank God for my sake,

Gather time for realisation.

Do not weep,

I may be restless as a defaulter.

Do not weep,

I may not excuse myself for my departure.

Do not weep,

I may not rest in peace.

Do not weep,

Keep yourself before me,

Keep yourself for you,

Keep yourself with time.

Do not weep,

Time was always yours,

Time is always yours,

I will remain yours,

In dreams,

In memory.

Do not weep,

Be my guide,

Be my well-defined friend.

Do not visit my resting yard,

No flower, please,

No weeping, please,

You may be in grief forever,

Do not miss but think to be.

I am always yours.

Define the divine love.

It is the eternal truth.

Truth is journey to unknown.

Mercy is a hindrance.

Do not weep for me.

I am a lesson.

Time changes.

Time is the best healer.

I had my time.

You are a beautiful symbol of bravery.

You may find this and more of Santable’s poetry here.

This poem explores themes of loss, resilience, and the enduring bond between loved ones through a heartfelt dialogue between the speaker and a mourner. The speaker urges the mourner not to weep at their grave, emphasizing their role as a source of strength and encouraging them to reflect on the joyful moments they shared. The repeated refrain of “Do not weep” highlights the desire for the mourner to embrace life fully and continue growing, fostering a deep sense of gratitude for the relationship that shaped their past.

The poem’s structure, characterized by short lines, creates a conversational tone that renders the message intimate and direct. This format allows the speaker to guide the mourner toward focusing on their own journey and the lessons learned from their shared experiences. Time emerges as a crucial symbol, representing healing and an ongoing connection that transcends physical separation. The poem’s simple yet powerful language reinforces themes of memory and appreciation, culminating in the assertion, “I am always yours.” This line encapsulates the enduring nature of their bond, suggesting that love persists even in death.

Throughout the poem, love is depicted as a lasting connection that survives beyond mortality. The speaker encourages the mourner to cherish memories rather than succumb to sorrow, reinforcing the idea that the relationship continues to hold significance. This perspective invites a sense of gratitude for shared experiences instead of a fixation on loss.

Ultimately, the poem captures the complexity of grief while emphasizing hope and the importance of treasuring memories. The speaker’s insistence on living fully reflects a profound understanding of love that endures beyond death. With its direct and simple language, the structure creates an intimate tone that feels personal and sincere. The repetition of “Do not weep” serves both to comfort the mourner and to encourage them to embrace life, conveying a powerful message about the resilience of love in the face of loss.

Photo by Robert Thiemann on Unsplash

October 19, 2024

I want to work in a cubicle

Olive

The perversion of the work-loving employee

creates a self fulfilling prophecy

as workload creates workload

and efficiency creates desire

yet each morning, count it, 16 nods

head held down by the primordial sea

of morning meetings between

hollowed out heads overflowing with itineraries

a sickness haunts the spreadsheets,

some dastardly fog still lingers

above the cubicles and beyond the break rooms

onset by fear in the eyes of employees at 4:45

glamorous countdown,

that ticking of the clock

buttons on the walls of the dryer

dastardly in the way it lingers

I long for the gracious stampede

where no shoulders rub

the ivory pencil dresses

and somber gray suits

You may find this and more of Olive’s works here.

This poem critiques the relentless cycle of work culture, addressing themes of burnout, dehumanization, and the empty pursuit of efficiency. Through stark language and vivid imagery, it conveys the exhaustion inherent in grind culture, where “workload creates workload” and “efficiency creates desire.” The repetition of routines, illustrated by “16 nods” in morning meetings, reflects a robotic existence, trapping employees in a self-perpetuating cycle that strips away individuality and joy.

The poem employs free verse, lacking a fixed meter or rhyme scheme, which mirrors the chaotic, unstructured nature of the work environment it depicts. This absence of traditional form enhances the monotony and unpredictability of daily tasks, creating an overwhelming and mechanical atmosphere with little room for human connection or respite.

The structure mirrors the cycle’s oppressive nature, with long, continuous lines symbolizing the monotony of daily work and feelings of being submerged in a “primordial sea” of corporate life. The “sickness” haunting the spreadsheets symbolizes the emotional and mental toll of work culture, hinting at a deeper malaise lingering in the workplace. Fear creeps in as the poem approaches the climactic “4:45,” where the countdown to the end of the workday becomes a twisted form of hope. However, even this moment of potential release is depicted as mechanical, with the ticking clock compared to “buttons on the walls of the dryer.”

The contrast between the glamorous “ivory pencil dresses and somber gray suits” and the speaker’s desire to escape emphasizes the tension between outward appearances and inner dissatisfaction. The “gracious stampede” at day’s end signifies not just leaving work but a yearning to break free from an oppressive routine where “no shoulders rub,” suggesting a space devoid of genuine human connection.

Overall, this poem critiques the dehumanizing effects of corporate life using symbols like clocks and spreadsheets to highlight the exhaustion and detachment workers experience in grind culture. Its free-flowing structure and dark imagery underscore feelings of burnout and fear, while the conversational tone and uneven rhythm reflect the chaotic nature of the work environment. The poem serves as a vivid portrayal of the emotional and physical toll that modern workplace culture imposes on individuals.

Photo by Adolfo Félix on Unsplash

Silence

Dawn Pisturino

Emptiness.

The desert no longer calls to me.

Your voice no longer whispers on the wind.

Silence—like a wet cloth—suffocates me. . .

Please click HERE to read the rest of the poem.

Click here to explore Dawn Pisturino’s page and her other poetry.

As a note, when a poet, or author only shares a portion of a piece and links to a publisher’s page, that is a consequence of a publishing agreement. Be respectful of that, but also take the time to explore that publisher’s page. You may find some other great works by other authors.

This poem conveys a powerful sense of isolation and longing, with its stark language and somber tone exploring themes of loneliness and disconnection. From the opening line, “The desert no longer calls to me,” the poem establishes a mood of desolation. Traditionally a symbol of vastness and reflection, the desert here loses its comforting qualities, reflecting the speaker’s internal shift. The speaker’s heart, described as “flat and dull,” mirrors the barren desert, highlighting their emotional desolation.

The imagery of silence, described as “like a wet cloth,” evokes suffocation, making the absence of sound feel heavy and oppressive. This silence, once a place for solace or connection, has now become stifling. The phrase “a living death” captures the speaker’s sense of being caught between life and oblivion, amplifying the emotional weight of the poem. As the speaker’s internal landscape grows as barren as the desert, their heart “barely beating,” the poem’s repetition of phrases like “Isolated. Alone.” reinforces their profound abandonment.

The climax, “WHERE ARE YOU?” bursts with raw desperation, acting as both a question and accusation. It emphasizes the speaker’s yearning for something that could restore a lost connection, whether with another person, a sense of self, or the desert itself. This unresolved longing highlights the painful reality of searching for meaning in a world that offers no response. The desert, devoid of whispers and life, symbolizes the speaker’s emotional isolation.

The free verse form, with its irregular line lengths and lack of rhyme or meter, mirrors the speaker’s fragmented thoughts, contributing to the poem’s sense of unpredictability and vulnerability. The repetition of phrases like “no longer” and the tightening structure as the poem progresses reflect the emotional contraction of the speaker. The final line, “WHERE ARE YOU?” disrupts the quiet tone and intensifies the sense of unanswered longing, leaving the reader with a lingering feeling of unresolved emptiness.

Pisturino’s “Silence” mournful tone captures feelings of loss, isolation, and the search for meaning amid overwhelming emptiness. Its sparse, direct language deepens the emotional impact, with the desert symbolizing both external and internal isolation—a place once full of life, now reduced to a hollow echo. The speaker’s struggle lies in the absence of connection and the realization that even the desert’s desolation no longer offers comfort. The poem’s irregular structure, lack of rhyme, and climactic question all enhance the themes of emptiness and isolation, reflecting the speaker’s fragmented emotional state.

Photo by Parsing Eye on Unsplash

October 18, 2024

I am

Amber Lynn Manning

I am a breeze, rustling through the Autumn leaves.

Crisp clean air that revitalizes the land.

I am a ray of sunshine, blanketing the Earth with my warmth.

Providing the light for all life.

I am the rain, washing the dust of the day away.

Breathing new life into everything I touch.

I am a tree, standing tall above the grass.

Holding firm in my roots, creating a shelter.

I am the sand, simple enough.

Infinite grains creating a pathway to walk the beach.

I am a wave, traveling the vast sea.

Finally, ending my life gracefully against the shore.

Amber shared the original poem here, please explore her other poetry.

This poem employs accessible language that allows a wide audience to engage with its themes. The straightforward vocabulary facilitates a quick connection to the imagery and ideas, particularly the theme of interconnectedness between the self and the surrounding world. Each stanza highlights a distinct aspect of nature—breeze, sunshine, rain, tree, sand, and wave—illustrating how the speaker identifies with these elements and suggesting a unity between individual existence and the broader ecosystem.

The tone is reflective and calm, promoting a sense of unity with the natural world. The speaker expresses a deep connection to various elements of nature, conveying both personal identity and a broader ecological awareness. This tone fosters an appreciation for the role of each element in the cycle of life.

Structurally, the poem consists of six stanzas, each centered around a different natural element. This consistent format emphasizes the diversity of nature while reinforcing the central theme of interconnectedness. The repetition of “I am” serves as a powerful affirmation of identity, linking the self to the world. The progression from the intangible (breeze, sunlight) to the more substantial (tree, sand, wave) mirrors the journey of life, illustrating how the self is both shaped by and contributes to the environment.

Overall, the poem’s straightforward language and clear imagery create a poignant reminder of the relationship between the self and nature, inviting readers to consider their own connections to the world around them.

Photo by Shifaaz shamoon on Unsplash

October 17, 2024

Coal Town

Ryan Stone

Birds don’t stop in this town.

I see them fly past, black peppering

blue, going someplace. I’ve given up

dreaming wings. This town

will know my bones. Condoms

sell well in Joe’s corner store – boredom breeds

but breeding’s a trap, a twitch in the smile

of those steel-eyed shrews

who linger late after church.

I walked half a day, out past the salt flats,

after they closed the movie house down. Smoked

the joint she’d brought back from college

when she returned to bury my dad.

I remember how pale her fingers lay

across my father’s hands –

coal miner’s hands, tarred like his lungs;

like this town.

Ryan posted this poem here.

First published in Eunoia Review, July 2016.

Winner of the Goodreads Monthly Poetry Contest, August 2016.

First Place in Poetry Nook contest 101, November 2016.

You can find more of his poetry and postings at his website here.

Ryan Stone’s “Coal Town,” effectively captures the theme of decay in small-town America, presenting a stark exploration of a community defined by stagnation and loss. Through vivid imagery and contrasts, it highlights the disillusionment often experienced in such environments. The free verse structure facilitates a conversational flow that mirrors the speaker’s reflective journey, enhancing the raw emotions conveyed. The poem delves into the moral decay of college-educated children, contrasting their aimlessness with the steadfast values of their labor-class parents. This tension emphasizes the profound disillusionment and loss of ideals that often accompany education and upward mobility.

The opening lines immediately establish a sense of movement with birds flying past—“black peppering blue”—which is quickly contrasted by the speaker’s admission of resignation: “I’ve given up dreaming wings.” This line encapsulates the struggle between aspiration and the weight of reality, suggesting that hope has been replaced by inevitability and entrapment. The repeated references to the town and its physical elements further create a claustrophobic atmosphere, emphasizing a sense of being trapped in a cycle of boredom and decay.

The imagery of the speaker walking “half a day” to the salt flats after the closure of the movie house reinforces the theme of decline, with the closing of the movie house serving as a metaphor for the loss of communal spaces and cultural vitality—a broader reflection of the town’s diminishing spirit. This decline is further emphasized through the juxtaposition of vibrant life, represented by the birds, against the town’s dullness, which “will know my bones.” This line encapsulates the inevitability of death and the permanence of place. Additionally, the mention of “condoms” and “steel-eyed shrews” introduces a gritty realism, suggesting a community ensnared in unfulfilled desires and harsh realities.

The poem portrays the town as a place marked by both physical and emotional decay, illustrated by the reference to “condoms” selling well in Joe’s corner store. This detail paints a bleak picture of the town’s moral landscape, where superficial pleasures thrive amid pervasive boredom. The phrase “breeding’s a trap” suggests that the cycle of life here is more about entrapment than progress, reflecting a moral ambiguity that permeates the lives of the college-educated youth. Additionally, the imagery of “steel-eyed shrews” lingering after church underscores a community grappling with unfulfilled desires, emphasizing a cycle of stagnation where life feels trapped in routine and disillusionment.

The speaker’s recollection of a friend returning from college to bury their father evokes a profound sense of loss, both personal and cultural. The comparison of the father’s “coal miner’s hands” to “tarred like his lungs” connects this personal loss to the town’s identity, highlighting the toll of labor and a shared fate marked by hardship and fading vitality. The juxtaposition of the friend’s college education with the physicality of the father’s hands serves as a critique of the perceived moral decline among the educated. While the father embodies hard work and resilience, the college-educated child appears disconnected, symbolized by the act of smoking a joint—a fleeting escape rather than a constructive engagement with life.

Overall, the poem poignantly critiques the loss of moral grounding in the pursuit of education and upward mobility, suggesting that the values of labor and resilience may hold more weight than the fleeting aspirations of the next generation. It reflects on the decay of small towns, using personal memory to illustrate a broader narrative of loss and resignation. Through stark imagery and informal diction, the poem captures the complexities of living in a place where dreams are overshadowed by reality. This effective combination of personal history and communal decay creates a compelling narrative that lingers long after reading, enhancing the themes of entrapment and memory.

To Irushka at the Coming of War

Frank Thompson

If you should hear my name among those killed,

Say you have lost a friend, half man, half boy,

Who, if the years had spared him might have built

Within him courage strength and harmony

Uncouth and garrulous his tangled mind

Seething with warm ideas of truth and light,

His help was worthless. Yet had fate been kind

He might have learned to steel himself and fight.

He thought he loved you. By what right could he

Claim such high praise, who only felt his frame

Riddled with burning lead, and failed to see

His own false pride behind the barrel’s flame?

Say you have lost a friend and then forget.

Stronger and truer ones are with you yet.

You can find this and other poems here.

This poem, written in 1939, explores the young soldier’s internal battle with his own sense of manhood and the fear of death as he goes to war. He sees himself as “half man, half boy,” acknowledging his incomplete growth and potential. His self-doubt is palpable, as he reflects on his “uncouth” nature, filled with lofty ideals but lacking the maturity to fully realize them. The poem’s steady rhyme scheme emphasizes his reflective tone, underscoring his sense of inadequacy, his unfulfilled potential, and his fear that he will be remembered more for his failings than what he might have achieved. Despite his belief that his love was imperfect, the speaker expresses the hope for understanding before asking to be forgotten in favor of “stronger and truer” individuals. The tension between his anticipation of death and his acknowledgment of his unfinished journey resonates deeply, capturing the emotional turmoil faced by young soldiers. Ultimately, the poem paints a portrait of a young man wrestling with insecurity, love, and the impending loss of his life, evoking a bittersweet reflection on youth and sacrifice.

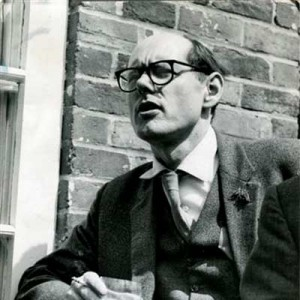

Frank Thompson

You can find this image here.

Frank Thompson (1920–1944) was a British poet and soldier, remembered for his literary talent and his work in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. Educated at Oxford, he became a prominent intellectual and writer with socialist ideals.

He joined the British Army in 1941 and later became part of the SOE, where he was deployed to support resistance forces in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. As a soldier-poet, Thompson’s writings reflected his idealism, intellect, and empathy for the oppressed. His work, often infused with socialist values, emphasized his belief in fighting for justice.

Captured by Bulgarian forces in 1944, Thompson faced trial and execution. His defiance at his trial is legendary; he maintained his commitment to his ideals, rejecting any chance to plead for clemency. Despite the short span of his literary output, Thompson’s writings capture the complexities of war, love, and revolution, preserving his legacy as both a poet and a soldier who gave his life for his beliefs. His bravery and eloquence remain a testament to the intellectuals who fought in World War II, bridging the world of literature and military service.

You can find more information here.

October 16, 2024

All Day It Has Rained

Alun Lewis

All day it has rained, and we on the edge of the moors

Have sprawled in our bell-tents, moody and dull as boors,

Groundsheets and blankets spread on the muddy ground

And from the first grey wakening we have found

No refuge from the skirmishing fine rain

And the wind that made the canvas heave and flap

And the taut wet guy-ropes ravel out and snap.

All day the rain has glided, wave and mist and dream,

Drenching the gorse and heather, a gossamer stream

Too light to stir the acorns that suddenly

Snatched from their cups by the wild south-westerly

Pattered against the tent and our upturned dreaming faces.

And we stretched out, unbuttoning our braces,

Smoking a Woodbine, darning dirty socks,

Reading the Sunday papers – I saw a fox

And mentioned it in the note I scribbled home; –

And we talked of girls and dropping bombs on Rome,

And thought of the quiet dead and the loud celebrities

Exhorting us to slaughter, and the herded refugees;

As of ourselves or those whom we

For years have loved, and will again

Tomorrow maybe love; but now it is the rain

Possesses us entirely, the twilight and the rain.

And I can remember nothing dearer or more to my heart

Than the children I watched in the woods on Saturday

Shaking down burning chestnuts for the schoolyard’s merry play,

Or the shaggy patient dog who followed me

By Sheet and Steep and up the wooded scree

To the Shoulder o’ Mutton where Edward Thomas brooded long

On death and beauty – till a bullet stopped his song.

You may find this poem and others here.

This poem, written in 1940 by a soldier, captures the bleak monotony of life at war, particularly during long stretches of inactivity. The tone is reflective, melancholic, yet conversational. The poet emphasizes the camaraderie shared by the soldiers, marked by their casual banter about everyday life, women, and war, yet always under the looming shadow of death. The structure, composed of long, free-flowing lines, mirrors the slow passage of time, as they wait in the rain, blending memories of peace with thoughts of war.

Camaraderie is conveyed through simple, shared experiences: smoking, reading newspapers, and repairing socks. Yet amidst this, there’s an undercurrent of loss and weariness. The poem ends with a poignant juxtaposition, recalling Edward Thomas, a poet-soldier from World War I, and the children playing innocently in the woods. This connection between the soldiers’ present and a past world that held beauty and innocence highlights the human cost of conflict. The “twilight and the rain” symbolize how war has consumed the soldiers’ lives, overtaking the memories of peace and home.

The poem’s structure is free verse, lending it an unpolished, organic feel, reflective of the everyday moments during wartime. The use of imagery, particularly nature, underscores the contrast between the soldiers’ isolation and the life they left behind. The mention of Edward Thomas, a poet who died in World War I, deepens the sense of loss and the cycle of war’s relentless toll on those caught in its grasp.

At the conclusion of the poem, Alun references Edward Thomas a War time poet from World War I.

Edward Thomas (1878–1917) was a British poet and essayist renowned for his nature poetry and introspective writing. Initially known for his literary criticism and prose, Thomas only turned to poetry in 1914, influenced by his friendship with Robert Frost. His major works include Adlestrop, The Owl, and Rain, poems that often explore themes of nature, memory, and loss. In 1915, Thomas enlisted in the British Army and was killed in action at the Battle of Arras in 1917. His war poetry reflects a deep sense of melancholy and reflection on human fragility.

For more information, visit Edward Thomas’s Wikipedia page.

Alun Lewis

Alun Lewis (1915–1944) was a Welsh poet and short story writer known for his poignant works that reflect his experiences during World War II. After graduating from Aberystwyth and Manchester universities, Lewis began his career as a teacher before enlisting in the British Army in 1940. His military service deeply influenced his writing, as seen in his poetry collections like Raider’s Dawn (1942) and Ha! Ha! Among the Trumpets (1945). These works capture the disillusionment and human toll of war, blending themes of love, death, and nature with vivid, often melancholic imagery. Lewis tragically died in Burma in 1944, but his legacy endures as one of the foremost war poets of his generation.

For further reading, visit Alun Lewis’s Wikipedia page.

October 15, 2024

Friends Gone

Ian Fletcher

Philip's slim half-forgotten hand-writingAnd Donald courting death like a girlAnd Tony when drunk finding God excitingAnd Peter whose courtship was too successfulFalling down in a locket of fire;And Kenneth with his sinister metaphysic;Jack Gregory loving his gun and his beerWith one or two others out of the wreckFashioning some vivid life of their own.Now what I remember, what runs quickRound the heart is this much alone:

Some found that death was too lovely, or

Some were bent on trying to believe it so,

Some merely stayed away, uncalled for:

Their time was shortest, having nowhere to go.

Poem source the Salamander Oasis.

This poem vividly captures the tragedy of war and the deep bonds of brotherhood, blending sorrow with moments of humor. Each character, from Philip to Peter, represents a life touched by the chaos of war—either cut short or irrevocably changed. The poet balances intimate memories with the absurdity of war, as in Tony’s drunk spiritual awakening. The free verse form mirrors the fragmented, unpredictable nature of wartime existence, emphasizing both the randomness of soldiers’ fates and the emotional toll on those left behind. Ultimately, humor and tragedy intertwine, highlighting the lasting impact of war on human connections.

The poem’s irregular structure reflects the disjointed memories of the fallen, and its final lines underscore the futility and brevity of life in war. Some soldiers embraced death, others tried to make sense of it, and a few simply faded away. Through these varied fates, the poem explores how the collective loss of comrades shapes the emotional landscape of those who survive, underscoring the weight of unresolved grief and the persistence of memories. Despite the brevity of their lives, the dead’s presence remains vivid, haunting the speaker and reminding us of the enduring legacy of brotherhood amidst the devastation of war.

Ian Fletcher

Ian Fletcher (1920–1988) was a renowned British literary critic and scholar, particularly known for his work on the Decadent and Edwardian periods of English literature. His academic contributions were instrumental in reshaping the study of often-overlooked literary figures, including Algernon Charles Swinburne, John Gray, and other poets of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Fletcher’s research illuminated the philosophical and stylistic shifts between the Victorian and modernist periods.

Born in 1920, little is documented about Fletcher’s early life. However, his passion for literature and intellectual exploration likely took root during his education. He pursued a career in academia, where his critical focus leaned toward the more obscure and marginalized literary movements, particularly the aesthetic and Decadent writers who challenged the Victorian moral landscape.

Fletcher’s life was notably marked by his service in the British military during World War II. The war profoundly impacted many of his contemporaries, fostering deep reflections on culture and art. Though specific details of his service are not widely recorded, the war likely influenced Fletcher’s worldview and intellectual interests. Many scholars and intellectuals of the time, having witnessed the devastation of global conflict, turned to literature as a way to find meaning and solace, and Fletcher’s work exhibits the kind of complexity and depth reflective of such life-altering experiences.

Fletcher’s academic career reached its height at Reading University, where he became a key figure in literary scholarship. His meticulous work reinvigorated interest in the poets of the Decadent and Edwardian movements, periods that had long been overshadowed by more mainstream literary figures like Tennyson or Hardy. Fletcher’s research, particularly his studies of Swinburne, brought fresh perspectives to English poetry and restored the importance of poets who had long been neglected by the critical establishment.

His work on Swinburne was particularly significant, as he repositioned this controversial poet within the broader landscape of English literature. Swinburne’s themes of eroticism, rebellion, and his critique of societal norms placed him outside the traditional literary canon, but Fletcher’s scholarly analyses highlighted the poet’s artistic value and philosophical contributions.

Fletcher also delved into the life and work of John Gray, another poet associated with the Decadent movement, further establishing his reputation as a critic who sought to revive interest in lesser-known figures. By reexamining such poets, Fletcher expanded the literary field’s focus and allowed for a more nuanced understanding of the intersections between aestheticism, symbolism, and modernism.

Beyond his contributions to the study of Decadent literature, Fletcher maintained a broader academic interest in Romanticism, particularly with figures like Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron. His work on these poets examined the radical ideas, revolutionary politics, and literary techniques that influenced later movements, including the Decadent period.

Ian Fletcher passed away in 1988, leaving behind a rich legacy of scholarly work. His dedication to exploring the margins of English literary history helped reshape academic discourse and ensured that many neglected poets received the recognition they deserved.

October 14, 2024

The Sonnet-Ballad

Gwendolyn Brooks

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

They took my lover’s tallness off to war,

Left me lamenting. Now I cannot guess

What I can use an empty heart-cup for.

He won’t be coming back here any more.

Some day the war will end, but, oh, I knew

When he went walking grandly out that door

That my sweet love would have to be untrue.

Would have to be untrue. Would have to court

Coquettish death, whose impudent and strange

Possessive arms and beauty (of a sort)

Can make a hard man hesitate-and change.

And he will be the one to stammer, “Yes.”

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

This evocative poem poignantly captures the heartache of losing a lover to war, intertwining themes of sacrifice and the loss of youth in a world torn apart by conflict. The form is a structured quatrain with a consistent rhyme scheme, lending a musical quality that enhances the emotional resonance. The rhythm propels the reader through the speaker’s lament, creating a sense of inevitability that mirrors the inescapable nature of war.

The tone is steeped in melancholy and resignation, marked by a deep longing for the past. The repeated cry, “Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?” underscores a universal quest for solace amid despair. This invocation of a maternal figure amplifies the emotional gravity, suggesting that the speaker’s suffering is both personal and collective, resonating with anyone who has experienced loss.

The theme of youth sacrificed to the ravages of war is central to the poem. The imagery of “empty heart-cup” poignantly illustrates the void left by the absence of the lover, while the line “my sweet love would have to be untrue” conveys a profound sense of betrayal—not just by the lover, but by the very circumstances of war that demand such sacrifices. The characterization of death as “coquettish” adds a haunting quality, portraying it as both alluring and threatening, which reflects the seductive yet devastating nature of conflict.

The finality of “he will be the one to stammer, ‘Yes’” encapsulates the choice made by the serviceman departing, highlighting that although there is a national call, each young man is complicit. This line resonates deeply, highlighting how war not only claims lives but how we agree to participate.

This poem weaves together form, tone, and theme to create a powerful meditation on the losses incurred by war, particularly the sacrifices of youth. It serves as a poignant reminder of the emotional and personal toll of conflict, leaving readers with a lingering sense of grief and reflection on the cost of love amidst the chaos of war.

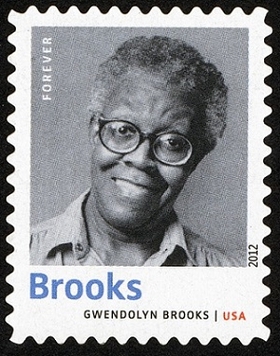

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks was an influential American poet, born on June 7, 1917, in Topeka, Kansas, and raised in Chicago. She became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for her book “Annie Allen” in 1949. Brooks’s poetry often reflects the experiences of Black life in America, addressing themes of identity, social justice, and the struggles of urban existence.

Throughout her career, she published several collections, including “A Street in Bronzeville” and “The Bean Eaters.” Brooks was also known for her commitment to her community and served as a mentor to younger poets. In 1968, she was appointed the Poet Laureate of Illinois, a position she held until her death on December 3, 2000. Her work continues to inspire and influence poets and readers today, making her a central figure in American literature.

October 13, 2024

Next steps

For a while now, really since WordPress locked me out of prompts, I’ve been happily romping around the world and through time exploring war poetry. Playing with it’s themes and participating in the tradition. I’m going to pivot a bit.

I’m going to continue to explore war poetry, but in a review format. While I do this, I’m going to collect and edit the work I’ve already done into what will be my first published poetry collection. I’m also going to start cataloguing the poems that I share, including poetry not yet within the public domain, with reviews. Not trying to build the largest collection of war poetry on the internet, but definitely trying to build a comprehensive collection that is not only centered on the western world.

With that, I don’t only want to focus on the grim topics of war, and dead poets. I’d like to also review the works of contemporary poets. I’m going to both collect, as well as accept the works of others to review. If you are interested in requesting a review, please use the contact form, or drop a comment. I will also cruise the internet and WordPress, for poetry to review, I’ll link back.

My goal is to promote others works, and open a real dialogue with other poets.

Not going to stop writing, just going to pivot a bit to get some more structured projects completed.

Photo by Laura Geror on Unsplash