Adam Fenner's Blog, page 16

November 29, 2024

A Poetic Warning (Revisited) – Reviewed

In a former life

Of chaos and disorder

Through a cosmic haze

Of bloodshed and strife

I well remember

A pilgrimage metaphysical

Seeking wisdom ancient

And knowledge mystical

From a secret agent

By the mythical code name

Brainwave Alpha

“First … you need learn how to fly,

if indeed, you wish to kiss the sky.”

With a flash of white light

And the clap of thunder

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

A Poetic Warning (Revisited)

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

In “A Poetic Warning (Revisited),” the poem takes us on a wild, psychedelic journey of spiritual searching, pulling in elements of mysticism, music, and cultural disillusionment. The speaker starts in a chaotic, disordered state, yearning for something greater — wisdom, enlightenment, maybe a utopian vision. But this search, as it unfolds, reveals itself to be more complex, shifting between idealism and disillusionment, with music, particularly Bob Dylan’s work, playing a critical role in that evolution.

From the very beginning, the theme revolves around the tension between transcendence and the inevitable letdown that often follows the pursuit of idealized states. The speaker describes a journey for wisdom, led by a mysterious figure, Brainwave Alpha, who offers a cryptic message: “First … you need learn how to fly, / if indeed, you wish to kiss the sky.” This is a metaphor for reaching a higher state, for seeking something more than the mundane — spiritual or intellectual enlightenment. But the journey isn’t just about ascension; it’s about the disillusionment that comes when that pursuit doesn’t pan out the way we imagine it will.

The quest for enlightenment is framed by an overwhelming sense of cosmic wonder, heightened by vivid, dreamlike imagery. Phrases like “a flash of white light,” “clap of thunder,” and “riding the crest of a wave” evoke the sensation of being on a trippy, mind-bending adventure. But despite the beauty and intensity of the experience, doubts begin to creep in. The speaker questions whether this mystical, higher realm is really “heaven,” or simply an illusion. The very idea of a “higher dimension of perpetual bliss” starts to feel more like an empty promise than a tangible reality.

It’s at this critical juncture that Bob Dylan enters the poem as a pivotal figure. Dylan’s music, specifically the song Gates of Eden, becomes a sharp reminder of reality, cutting through the haze of idealism. Dylan’s role in the poem is not just symbolic; it’s a wake-up call. He comes in with his harmonica and electric guitar, almost like a modern-day prophet, pulling the speaker out of their blissed-out trance. The phrase “a poetic warning that cut like a knife” signals this shift. Dylan’s song critiques the utopian visions the speaker has been chasing, suggesting that these idealized paradises are hollow, built on false promises.

This turning point in the poem brings us to a structural shift. In the beginning, the poem’s form feels loose, fluid, and expansive, mirroring the speaker’s dreamy journey. The lack of a set rhythm or pattern enhances the feeling of drifting through cosmic realms. However, as Dylan’s song interrupts the flow, the poem tightens in focus. The speaker is jolted back to a grounded, more reflective place. This shift in structure, from freeform to something more direct, mirrors the change in tone from mystical reverie to sober reflection.

The tone of the poem evolves with this shift. At first, it’s full of wonder and curiosity, the speaker caught up in the euphoria of a transcendental pursuit. But as the doubts start to surface, the tone becomes more skeptical. The appearance of Dylan marks the most significant tonal change, as the speaker now faces the hard truth that their quest for a perfect paradise is, at best, misguided. This realization is not just disheartening; it’s sharp, almost sardonic, as the speaker understands that chasing utopia often leads to disappointment rather than fulfillment. The tone, once airy and expansive, becomes more grounded and ironic — a clear critique of the illusions that come with seeking a perfect world.

Music, especially Bob Dylan’s song lyrics, serves as the key to unlocking this disillusionment. The reference to Gates of Eden adds a cultural and philosophical layer to the poem. Dylan’s lyrics in the song point out the futility of seeking a perfect, idealized paradise — a theme that resonates deeply in the poem. In Gates of Eden, Dylan describes a world that, while seemingly perfect, is unattainable and, ultimately, empty. The line “with a time-rusted compass blade / Aladdin and his lamp / Sits with Utopian hermit monks” suggests that those who chase such dreams end up disconnected from any real wisdom. They are sitting alongside false idols, like the “Golden Calf,” worshipping empty promises. The idea that “you will not hear a laugh, all except inside the Gates of Eden” is especially poignant, as it highlights the irony and emptiness of chasing unattainable ideals.

Ultimately, A Poetic Warning (Revisited) is about the realization that the pursuit of transcendence — whether spiritual, intellectual, or otherwise — can be a hollow and disillusioning experience. The structure of the poem, with its loose and expansive beginning, mirrors the carefree pursuit of enlightenment, while the tightening focus toward the end reflects the sobering realization that such pursuits often lead to disappointment. The poem warns against idealizing utopia, showing how such a vision can become a trap — something that looks beautiful but proves empty once attained. Dylan’s music offers the sobering clarity needed to see through the illusion.

The message of the poem is a powerful one: wisdom doesn’t always come from ascension or from searching for an ideal world. Sometimes, it comes from understanding the limitations of these pursuits and facing the reality that perfection is not something we can attain. The speaker’s journey through cosmic realms ultimately leads to the understanding that seeking wisdom involves accepting imperfection, and that real enlightenment might come from the most unexpected places, like a song, a moment of clarity, or a shift in perspective. The poem’s reference to Dylan serves as a reminder that wisdom, though often elusive, is not about escaping the world but about confronting it as it is.

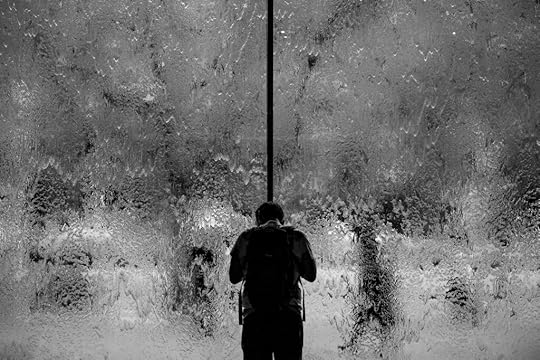

Photo by Lacey Williams on Unsplash

November 28, 2024

SEDUCTION – Review

the rhythm of castanets awakens the moon

on opal rings your kisses spin

a cricket’s hitting a crescendo

waves tattoo dark shadows on your skin

sonority, you who vibrates the souls

of those who haunt at night the Port of Cartagena

I toss in smells of apricots and plumes

the Hand of Fatima takes off my veils

your forehead sinks into the sweat of lovers

who sever their veins

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Thanksgiving wishes, a poem, and more on Celebrating Poetry by Cindy Georgakas

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

In “Seduction,” the poem delves into the complexity of desire, attraction, and the roles that both lover and beloved play in the act of seduction. It doesn’t just recount a romantic exchange—it plunges the reader into the very experience of seduction itself, showing how fluid and shifting these roles can be. Throughout the poem, the boundaries between the one doing the seducing and the one being seduced blur, creating an atmosphere of confusion and tension that mirrors the contradictory nature of romantic and sexual encounters.

From the start, the poem conjures a world that is both familiar and otherworldly. Imagery like the “rhythm of castanets” and the moon’s “awakening” immediately sets a tone of intense sensuality. The scene is charged with physical sensations—sounds, smells, textures—that create a powerful, almost cinematic experience. But the poem also carries a deeper, more mystical quality, as if the seduction is tied to forces beyond the control of either participant. The mention of the moon and “sonority,” for instance, hints at something cosmic or inevitable about the attraction between the two. It’s as if seduction isn’t just an act of two people coming together, but a force that sweeps them into its current, compelling them to follow paths they may not fully understand.

This blending of the physical and the mystical deepens as the poem progresses. The speaker’s surrender to the act of seduction becomes apparent when the Hand of Fatima takes away their veils, a powerful symbol of protection and fate. The removal of the veil here is significant—it’s not an act of the speaker’s own doing, but something that happens to them. This suggests that in the act of seduction, one can lose control, not only of their body but of their very identity. The Hand of Fatima becomes an external force that pulls the speaker further into this seductive world, marking a moment of both vulnerability and inevitability.

In this way, the poem plays with the idea of power in relationships—who holds it and how it shifts between the lovers. The speaker’s role is complicated: they are at once an active participant and a passive object of desire. The lines “your forehead sinks into the sweat of lovers / who sever their veins” describe a kind of mutual loss, an emotional and physical sacrifice that both parties share. Love here is presented as something that demands a high cost—perhaps even a kind of destruction. The image of lovers “severing their veins” suggests that seduction comes with the potential for both intimacy and harm, an exchange that leaves both parties exposed and vulnerable.

This sense of sacrifice and transformation is echoed in the closing lines: “it wasn’t me / it was you who stole his soul.” Here, the speaker shifts the blame to the lover, acknowledging that seduction is not a one-sided act. The lover’s words—“I love you”—are steeped in myth, and by saying “you stepped on roads of fables and folk tales,” the speaker links their experience to something larger, almost inevitable. The act of seduction is part of a grand narrative, a cycle of power and loss that transcends individual encounters. Yet, in placing the blame on the lover, the speaker also points to their own complicity. Seduction isn’t just about one person taking; it’s about a shared experience that leaves both parties irrevocably changed.

The poem’s imagery constantly moves between the personal and the universal, the real and the imagined. The line “you glued your heart onto a purple sunset” is one of many moments where the lover’s emotions seem both passionate and fleeting, bound to something ephemeral. Here, the heart is attached to a sunset—a symbol of something beautiful but doomed to fade. This gives the poem a sense of both intensity and transience, a reminder that desire can be overwhelming but also passing, like the tides or the seasons.

“Seduction” doesn’t resolve the conflict it presents; instead, it leaves the roles of lover and beloved ambiguous and fluid. It’s as if seduction itself is a force that defies easy explanation, where identities shift and change, and where the one who seems in control may be just as lost as the one being seduced. The final realization that “it wasn’t me / it was you who stole his soul” underscores the complexity of these roles. It’s not just a story of one person being taken, but a mutual transformation that leaves both parties marked. The poem leaves us with the sense that seduction, love, and desire are not static—they are constantly in flux, like the mythic tales and fables that have been passed down through generations.

Ultimately, the poem explores how attraction can transcend the personal, becoming part of something larger, timeless, and mythological. The language of folklore, the references to symbols like the Hand of Fatima, and the suggestion that seduction is something both spiritual and transformative give the poem an emotional depth that lingers long after the words end. In the end, “Seduction” is a meditation on how love, desire, and power constantly shift between the lovers, leaving them both altered, lost in the ebb and flow of desire’s pull.

Hands of Fatima

The hamsa, also known as the Hand of Fatima, is a palm-shaped amulet that has been used for centuries across North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Europe. It features the image of an open hand and is traditionally believed to offer protection against the evil eye, a harmful gaze thought to bring bad luck or illness. This symbol, representing five fingers, is often used in jewelry, wall hangings, and other decorative items.

Historically, the hamsa has roots in several ancient cultures. The earliest examples can be traced back to Mesopotamian and Phoenician artifacts, where it was associated with goddesses and used as a protective symbol. In ancient Carthage, it appeared as part of religious symbols dedicated to deities like Tanit, and it is also seen in early Jewish and Christian contexts. Over time, it became a common amulet among Sephardic Jews, who believed in its power to ward off the evil eye, a concept prevalent in Mediterranean cultures.

The hamsa has different meanings depending on the culture. In Jewish tradition, it is often linked to the “strong hand” of God, mentioned in the Bible as the force that led the Israelites out of Egypt. In Islamic culture, it became known as the Hand of Fatima, named after the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad, and is seen as a symbol of divine protection. Among Christians in the Levant, it is called the Hand of Mary, referring to the Virgin Mary’s protective qualities.

The amulet’s symbolism is deeply connected to the concept of protection and blessings. It is typically depicted with the fingers spread apart to ward off negative energy or closed together to bring good fortune. In many cultures, it is also adorned with an eye symbol to strengthen its power against the evil eye. The number five, which corresponds to the five fingers of the hand, is another key element, representing various forms of protection and good luck.

In modern times, the hamsa has become a popular symbol beyond religious and cultural boundaries. It is often used as a “good luck” charm and can be found in a variety of forms, from jewelry to home decor. While it lost some of its traditional religious significance during the modernization of the Middle East, it has since made a resurgence as a secular symbol of protection and positivity.

Today, the hamsa is still widely used in the Middle East, North Africa, and beyond, especially in jewelry, art, and other cultural expressions. Its enduring popularity highlights its continued cultural importance as a symbol of safeguarding against misfortune.

Photo by Nahid Hatami on Unsplash

November 27, 2024

Lost Horizons – Review

Ever since I began work

I said

I’d travel to Tibet,

Take off one summer, rucksack on my back,

Freedom in my stride

But other things intervened:

Another child,

Extensions to the house,

A hard mortgage

But now

…

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

You may find this and other poems here.

Lost Horizons

Analysis

“Lost Horizon” is a poem that explores the theme of unfulfilled dreams, particularly the tension between a desire for adventure and the realities of domestic life. At the core of the poem is the speaker’s dream of traveling to Tibet, a place that represents freedom, spirituality, and exploration. This dream, however, is slowly overtaken by the demands of family, work, and financial responsibilities. What once seemed like a straightforward ambition—symbolized by a rucksack and the promise of freedom—becomes an increasingly distant and abstract goal, something left behind in the wake of life’s practical concerns.

The poem is structured in free verse, which suits its conversational, almost casual tone. There’s no strict rhyme or meter, which mirrors the speaker’s unpredictable life and wandering thoughts. The speaker reflects on how time has passed and how the dream of visiting Tibet has slipped further away, delayed by things like children, home improvements, and the financial weight of a mortgage. Instead of embarking on a real journey to Tibet, the speaker finds himself watching documentaries, listening to tapes of the Dalai Lama, and studying Buddhism from a distance. These are substitutes for the real experience, a way of connecting to the idea of Tibet without ever actually getting there.

The shift from active exploration to passive consumption highlights the internal conflict at the heart of the poem. At one point, the speaker had the freedom to dream of adventure, but now, with adult responsibilities in the way, that dream has turned into an unreachable fantasy. The reference to “Shangri-La” and watching reruns of Lost Horizon emphasizes how the dream has become an idealized, distant image rather than a tangible goal. The speaker acknowledges this reality with a mix of resignation and subtle humor. The line “One day, I say, One day” reflects this resignation—it’s both a promise of hope and an empty acknowledgment that the dream may never come true.

The poem’s tone is bittersweet. The speaker doesn’t express anger or frustration about the unfulfilled dream; rather, there’s a quiet acceptance of how life has unfolded. The question from the child, “When are you going to Tibet, Dad?” serves as a gentle reminder of promises made long ago, but also underscores the passage of time and the speaker’s failure to act on those promises. The speaker’s response, “One day, I say, One day,” feels like both a hopeful wish and a quiet admission that the journey will likely never happen. This line captures the tension between what could have been and what has actually occurred.

Ultimately, “Lost Horizon” is about the way dreams can become overshadowed by the responsibilities of adult life. The speaker’s dream of exploring Tibet is something many people can relate to—the desire to travel, to experience something new, to break free from the routine. But as life moves on, those dreams often get pushed aside in favor of more pressing concerns. In this case, Tibet becomes not just a physical destination but a metaphor for any dream that gets delayed or forgotten in the face of life’s practicalities. The speaker comes to terms with this reality, recognizing that some dreams might be impossible to achieve, but that doesn’t mean they are entirely lost. Instead, they transform into something else—perhaps a memory, a fantasy, or a distant hope, but not necessarily a failure.

Through the simple, conversational structure and the speaker’s reflection on how time alters our goals, the poem captures a universal experience: the way dreams, no matter how important they once seemed, can fade or shift as life’s demands take over. The journey to Tibet may never happen, but the poem leaves room for the speaker to find other ways to engage with that dream, whether through books, reruns, or quiet moments of reflection. In the end, it’s not the fulfillment of the dream that matters, but the acceptance of the life that has unfolded in its place.

Photo by Lucija Ros on Unsplash

November 26, 2024

Thoughts on a Sunday Morning in the Rain – Review

Francisco Bravo Cabrera

What’s in a name?

Your name,

your good name,

your fame,

your reputation?

It’s worth more than gold,

than bit-coins,

than “likes”,

than followers

or comments…

Common sense?

Or the sense to be common?

The idiot does not recognise danger

and falls into a pit,

a pit of despair or a cliff.

The prudent man avoids danger,

recognising it for what it is

because he has eyes to see,

lips to seduce,

ears to let sound waves caress

the innermost dancer, dancing in the dancehall of the soul…

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

#poem, “Thoughts on a Sunday Morning in the Rain”

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

Thoughts on a Sunday Morning in the Rain invites readers into a space of quiet reflection, urging them to reconsider what truly matters in life—wisdom, reputation, self-awareness, and the importance of living with integrity. The poem uses the calm, introspective mood of a rainy Sunday morning to create the perfect setting for deep, personal thought. It encourages slowing down and taking the time to reflect on one’s choices, actions, and values, reminding us that in a world filled with distractions, it’s easy to lose sight of what truly defines a meaningful life.

The poem starts by asking, “What’s in a name?” This simple question is much deeper than it might seem at first. The poet points out that reputation—our name—holds more value than material wealth, social media likes, or followers. These external markers of success are fleeting, temporary, and unreliable. What truly matters is how we carry ourselves in the world, the integrity we maintain, and the legacy we leave behind. The poem quickly challenges readers to think about their own reputation, not in the sense of public image or fame, but in terms of character and lasting impact.

One of the major themes in the poem is the distinction between wisdom and folly. The poet contrasts the “idiot” who falls into a pit because they fail to recognize danger, with the “prudent man” who avoids harm because he is aware and attentive. This isn’t just about being smart; it’s about being mindful and paying attention to the world around us. The “prudent man” sees the world with clarity, while the “idiot” is oblivious to the risks that lie ahead. The poem thus encourages readers to cultivate awareness, to actively reflect on their surroundings and decisions, and to live with purpose rather than blindly following the flow of life.

The poem also speaks to the dangers of pride and arrogance. The “spoiled child” who grows up stubborn and spiteful is destined to a life of difficulty. The poet suggests that unchecked ego can lead to poor decisions, failure, and suffering. The metaphor of a “good whack in the butt” is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but it highlights the importance of discipline and humility in the process of personal growth. Without the willingness to confront our own flaws and correct our course when necessary, we risk living a life filled with regret and wasted potential.

Reputation is further examined in the poem through the figure of the “gossipy woman,” a symbol of how quickly and easily one’s name can be destroyed by rumors or idle chatter. This is a reminder of how fragile reputation can be, especially in today’s world where gossip spreads quickly through social media and word of mouth. Once damaged, a reputation may never fully recover. The poet urges readers to be mindful of how their words and actions affect others, as well as the company they keep. In a world that often seems to thrive on scandal and rumor, it is important to protect one’s reputation with care and to act with integrity at all times.

But the poem isn’t just about avoiding missteps; it’s about striving for something greater. The poet calls on the reader to aim for excellence, to rise above mediocrity, and to reflect deeply on how they can become the best version of themselves. It’s not enough to just get by in life; we should constantly push ourselves to grow, to learn, and to become more than we were the day before. This call to personal growth and self-improvement is one of the most powerful elements of the poem, urging readers to think about the legacy they want to leave and how they can live a life of meaning and substance.

The poet also critiques the false sense of security that comes from wealth. The poem asks whether riches are earned or “ill-gotten,” suggesting that we should reflect on how we acquire material possessions and the impact that has on others. There is an ethical consideration here: how we obtain wealth—whether through honest work or exploitation—shapes who we are as individuals. The poem calls for a deeper examination of the choices we make and challenges the idea that financial success should be our primary goal. Instead, it encourages us to seek wisdom, compassion, and integrity, values that are far more important than money or status.

In the latter half of the poem, the poet takes a step back and questions the very nature of reality. What if everything we’ve been taught is a lie? This existential line of questioning urges the reader to think critically about the beliefs and assumptions that shape their worldview. It encourages introspection and challenges us to examine whether the truth we take for granted is truly our own, or if it has been shaped by others. This is a powerful call to intellectual independence and self-awareness, asking us to question the systems and ideas we live under and to decide for ourselves what is true and meaningful.

The poem closes by returning to the idea of reflection, suggesting that the best time for deep thinking is in moments of solitude—like those found on a quiet, rainy Sunday morning. The rain here acts as a symbol of clarity and renewal, a time to pause and look inward. The poet reminds us that true wisdom doesn’t come from external validation or wealth, but from taking the time to reflect on our lives and our place in the world. It’s in these quiet moments that we can gain the clarity needed to make better choices, to understand our true priorities, and to pursue a life of greater meaning.

In the end, Thoughts on a Sunday Morning in the Rain is a call for deep self-reflection. The poem challenges readers to reconsider their values, to think critically about their actions and beliefs, and to live a life of integrity. It’s a reminder that success is not measured by external validation—whether that’s fame, wealth, or popularity—but by the depth of our character and the wisdom we cultivate. Through introspection and thoughtful action, we can strive to become the best versions of ourselves and lead lives that are meaningful, purposeful, and true.

Photo by Vincent Wachowiak on Unsplash

November 25, 2024

Fading Into Obscurity – Review

It’s happened

I fade away

No one’s reading

Less views per day.

–

I’m just not sure

What can I do

To ebb the flow

Or am I through.

–

Once my blog bloomed

Thousands of views

Now low hundreds

What can I do.

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Fading Into Obscurity

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

“Fading Into Obscurity” paints a relatable and raw picture of the frustrations many creators face in today’s digital landscape. The poem reflects the emotional struggle of watching an online presence slowly fade despite hard work, dedication, and genuine effort. It speaks to a reality where success can be fleeting, and visibility on platforms often feels beyond a creator’s control. For anyone who has built something online—whether a blog, a social media account, or any other creative project—this poem will hit close to home.

The theme revolves around the uncertainty of maintaining an online audience. The speaker starts by noting the decline in views, a sharp contrast to the “thousands of views” their blog once received. This shift is something many creators experience as algorithms change, trends shift, or competition increases. There’s a deep sense of loss that comes from watching something you’ve worked hard on slip out of focus. It’s not just about the views but the sense of fading relevance and wondering whether all the time and energy put in is even worth it anymore.

The structure of the poem mirrors the speaker’s scattered thoughts. With short, almost clipped stanzas, the poem captures the urgency and confusion the speaker feels. These fragmented lines give us a sense of how the speaker’s mind is racing, trying to find answers but getting caught in a loop of self-doubt. The repetition of lines like “What can I do?” or “What if I quit?” shows the speaker’s internal conflict, constantly questioning what went wrong and if they should even keep trying. It’s a snapshot of someone grappling with the overwhelming feeling of being stuck, unsure whether their efforts will ever bring them back into the spotlight.

Tone-wise, the poem is one of resignation and exhaustion. The speaker’s voice is not angry or bitter, but weary—almost defeated. Phrases like “I need to rest” and “Doesn’t matter” reflect the emotional toll of trying to keep up with a system that’s constantly changing. There’s a clear sense of burnout, not just creatively but emotionally, as the speaker grapples with their fading relevance. The tone also reflects the impersonal nature of the platforms themselves, where creators’ fates are often dictated by algorithms beyond their control, leaving them with little agency in their own success.

The poem also touches on the bitterness that can come with competition. The line “Some jealous folks / Went to WordPress” suggests that others may have found success at the speaker’s expense, possibly by exploiting the system in ways the speaker could not or would not. It adds an extra layer of frustration, showing that success online is often about more than just talent or hard work. It can feel like the rules are rigged, and that success is often about strategy or luck, rather than pure merit.

What stands out in “Fading Into Obscurity” is its lack of resolution. The poem ends on a quiet, unresolved note. The speaker doesn’t find a way to turn things around, nor do they decide to quit for good. The final line—“Fading into / Obscurity…”—feels both like an end and a continuation, as though the speaker is resigned to the inevitable, but still unsure of what that means. The poem doesn’t offer answers, and that’s what makes it so powerful. Many creators will relate to the uncertainty and the feeling of being caught in an endless cycle of trying to stay visible, despite changes beyond their control.

There’s a sense of realism in how the poem addresses the experience of fading away online. It doesn’t romanticize or offer false hope. Instead, it gives voice to the frustration, confusion, and quiet despair that comes when you feel like you’re working hard for something that no longer seems to matter to anyone. The poem is a stark reflection of the struggles of maintaining an online presence, whether it’s the unpredictability of algorithms, the fatigue of constant effort, or the loneliness that comes with feeling unseen.

Overall, “Fading Into Obscurity” speaks to the realities of being an online creator. Its simple, unadorned structure and raw emotion capture the quiet resignation of someone trying to keep up in a system that’s often beyond their control. The speaker’s journey—marked by moments of self-doubt, frustration, and fatigue—feels incredibly relatable to anyone who has tried to make their mark online, only to find that success is as unpredictable and fleeting as the platform itself.

Photo by Benoit Roy on Unsplash

November 24, 2024

I can’t remember you – Review

Michelle Cook

I forgot you

You made me forget you

And now

Whenever I think of you

I can’t remember

Why I’m thinking of you

I think a piece of my heart

Has a muscle memory of you

But my mind can no longer be sure

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

I can’t remember you

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

“I Can’t Remember You” is a poem that explores the process of letting go of a painful relationship and the strange way memories fade over time. The speaker reflects on how, despite the passing of time, the emotional impact of the relationship lingers in the heart, even as the mind forgets. There’s a tension between the heart’s memory and the mind’s forgetfulness, capturing the complexity of healing after a loss.

The central theme of the poem revolves around the idea of emotional release through forgetting. At first, the speaker talks about how they’ve “forgotten” the person, even suggesting that the other person may have been responsible for making them forget. This implies that the act of forgetting wasn’t a passive process but one that was perhaps forced by the circumstances of the relationship. In this sense, forgetting is a survival mechanism, a way for the speaker to move on from pain and emotional weight.

But as the poem continues, the speaker acknowledges that while the mind forgets, the heart holds on to what could be described as “muscle memory.” This idea of “muscle memory” is powerful because it suggests that emotions and memories are stored in the body in ways the mind may not fully understand. Even though the details of the relationship may blur, there is still something in the heart that remembers. This contrast between the mind’s erasure of the past and the heart’s lingering echo speaks to the complexity of emotional memory.

The structure of the poem itself reflects the disjointed nature of memory and forgetting. The free verse form, with its irregular line breaks and lack of rhyme, mirrors the fragmented and unclear process of recalling something lost. The speaker’s thoughts appear scattered, and the lack of punctuation at the ends of some lines gives the poem an unfinished, almost drifting quality. This conveys the sense that the speaker is trying to hold on to thoughts and emotions that are slipping away, much like the process of letting go of a painful memory.

Tone-wise, the poem is introspective and melancholic, but not overwhelmingly sorrowful. There’s a quiet resignation in the speaker’s voice, as if they’ve come to terms with the gradual fading of the relationship, both in their mind and their heart. The speaker doesn’t express bitterness; instead, there’s an acceptance that this process of forgetting, though difficult, is part of healing. The final lines, where the speaker says, “the pain I once felt is finally gone,” signal a sense of emotional release. It’s as if the act of forgetting, while initially uncomfortable, has brought about a kind of peace.

Throughout the poem, the speaker’s journey from confusion and loss to eventual relief is subtle but clear. The fading of the memory is not an active decision but a natural, almost inevitable part of moving on. This sense of healing is portrayed as a quiet, internal process—a shift from emotional chaos to a calm, neutral space. The poem speaks to how time and distance from the relationship help the speaker heal, not by forcing them to forget, but by allowing them to do so without resistance.

“I Can’t Remember You” is a reflection on how we remember and forget, particularly in the context of healing from a painful relationship. The poem highlights the tension between the heart’s lingering emotions and the mind’s fading memories, suggesting that while forgetting can feel like loss, it’s also part of the natural process of moving on. There’s a sense of peace that comes with the fading of the past, as time allows for emotional release. Through its structure, tone, and themes, the poem captures the quiet, often unnoticed process of letting go, offering a meditation on how we heal from heartbreak and find closure, sometimes without even realizing it.

Photo by Samuel Austin on Unsplash

November 23, 2024

Hymn Before Action – Review

Rudyard Kipling

The earth is full of anger,

The seas are dark with wrath,

The Nations in their harness

Go up against our path:

Ere yet we loose the legions —

Ere yet we draw the blade,

Jehovah of the Thunders,

Lord God of Battles, aid!

High lust and froward bearing,

Proud heart, rebellious brow —

Deaf ear and soul uncaring,

We seek Thy mercy now!

The sinner that forswore Thee,

The fool that passed Thee by,

Our times are known before Thee —

Lord, grant us strength to die!

For those who kneel beside us

At altars not Thine own,

Who lack the lights that guide us,

Lord, let their faith atone.

If wrong we did to call them,

By honour bound they came;

Let not Thy Wrath befall them,

But deal to us the blame.

From panic, pride, and terror,

Revenge that knows no rein,

Light haste and lawless error,

Protect us yet again.

Cloak Thou our undeserving,

Make firm the shuddering breath,

In silence and unswerving

To taste Thy lesser death!

Ah, Mary pierced with sorrow,

Remember, reach and save

The soul that comes to-morrow

Before the God that gave!

Since each was born of woman,

For each at utter need —

True comrade and true foeman —

Madonna, intercede!

E’en now their vanguard gathers,

E’en now we face the fray —

As Thou didst help our fathers,

Help Thou our host to-day!

Fulfilled of signs and wonders,

In life, in death made clear —

Jehovah of the Thunders,

Lord God of Battles, hear!

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

You may find this and other poems here.

Analysis

Rudyard Kipling’s “Hymn Before Action” is a powerful and deeply reflective poem that speaks to the moral and spiritual turmoil faced by soldiers on the brink of war. Written during World War I, the poem blends Christian themes with vivid natural imagery, using them to explore the internal conflicts of soldiers preparing for battle. The poem is framed as a prayer, calling on divine intervention to help soldiers confront the violence and chaos they are about to face, while also grappling with their own vulnerability, sin, and need for redemption.

The poem opens with a stark portrayal of nature’s wrath. “The earth is full of anger, / The seas are dark with wrath,” Kipling uses nature to mirror the violence of the war. The earth and seas are personified as hostile forces, setting the tone for the poem. The imagery of “angry earth” and “dark seas” suggests a world in turmoil, overwhelmed by the destruction wrought by human conflict. This natural chaos parallels the soldiers’ own emotional and moral disarray, as they prepare to march into a battle that seems inevitable and all-consuming. It is as though nature itself is complicit in the violence, adding an additional layer of tension and urgency to the soldiers’ plight.

In this context, Kipling introduces the central theme of divine intervention. The soldiers, aware of their own moral failings, turn to God, asking for mercy and strength. “Jehovah of the Thunders, / Lord God of Battles, aid!” By invoking God as the protector of soldiers, Kipling places the poem within a Christian framework, drawing on biblical traditions where soldiers and warriors seek divine favor before battle. The soldiers’ prayer is not for victory but for the strength to face death and for guidance through the moral uncertainties of war. They ask for protection from their own darker impulses—“panic, pride, and terror”—and the chaotic, lawless tendencies that can arise in the heat of battle. This plea for divine mercy reflects the internal moral struggle that soldiers endure as they wrestle with fear, duty, and the potential for wrongdoing in the face of violence.

The Christian themes of sin and redemption are central to the poem. The soldiers acknowledge their unworthiness—“the sinner that forswore Thee, / The fool that passed Thee by”—yet still plead for God’s grace. The phrase “grant us strength to die” encapsulates not only a willingness to face death but a desire for spiritual strength to endure the violence they will face, suggesting that the battle is as much a moral and spiritual challenge as a physical one. This recognition of the soldiers’ sinfulness and their plea for mercy emphasizes the moral confusion and emotional weight of war. Kipling does not glorify war but instead portrays it as a place where soldiers must confront their own weaknesses and vulnerabilities, asking for divine help in navigating the complex moral terrain of battle.

The inclusion of Mary, “pierced with sorrow,” brings a compassionate and nurturing element to the poem. Kipling calls on the Virgin Mary to intercede on behalf of the soldiers, reflecting the Christian view of Mary as a compassionate figure who understands human suffering. “True comrade and true foeman” is a line that highlights the shared vulnerability of all soldiers, whether friend or foe. This plea for mercy for soldiers of all nations, regardless of their faith, underscores Kipling’s understanding of the common humanity that binds people together, even in the midst of war. The prayer for Mary to intercede also suggests that there is a hope for mercy that transcends religious boundaries—a desire for redemption for all, not just those who share the same beliefs.

In addition to Christian themes, Kipling uses nature to reflect the soldiers’ emotional and spiritual struggles. The metaphor of the soldiers being “bound in harness” suggests that they are part of a larger, uncontrollable force, trapped by history and fate. The natural world—represented by the angry earth, dark seas, and thunder—acts as a reflection of the uncontrollable forces at play in the soldiers’ lives. Kipling evokes the destructive power of storms, which mirror the emotional storms within the soldiers themselves. “Jehovah of the Thunders” is a plea for divine intervention, asking God to control the storm, both literal and figurative, that the soldiers face. This heightened sense of nature’s fury emphasizes the sense of doom that hangs over the soldiers as they approach the battlefield.

However, Kipling also acknowledges the soldiers’ potential to disrupt the natural and moral order. The lines “revenge that knows no rein” and “light haste and lawless error” suggest that the soldiers may be swept away by their own destructive impulses. Despite their prayers for divine guidance, they are aware that they might act in ways that mirror the chaos of nature. The soldiers are asking for protection not just from external enemies but from the darker forces within themselves—fear, panic, and revenge—that threaten to cloud their judgment and lead them astray.

In the final stanzas, Kipling brings the prayer full circle, asking for protection and guidance as the soldiers face the coming violence. The tone is one of grim acceptance, with no illusions about the horrors of war. The repetition of phrases like “Jehovah of the Thunders” and “Lord God of Battles” reinforces the urgency and earnestness of the plea, while also creating a ritualistic, hymn-like structure that mirrors the soldiers’ preparation for battle. The poem ends with a final plea for divine aid: “E’en now their vanguard gathers, / E’en now we face the fray.” This sense of inevitability underscores the helplessness the soldiers feel in the face of the overwhelming forces of nature, history, and war.

Ultimately, “Hymn Before Action” is a meditation on the vulnerabilities of soldiers and the moral and spiritual challenges they face in the lead-up to war. Kipling’s use of nature to reflect both the destructive forces of war and the soldiers’ internal struggles is effective in conveying the bleak reality of battle. The Christian themes of sin, mercy, and redemption add a layer of depth to the poem, highlighting the soldiers’ need for divine intervention as they grapple with their fears, pride, and moral uncertainties. The poem is not a glorification of war but rather a solemn prayer for strength, guidance, and compassion in the face of impending violence. In a world ravaged by war, Kipling’s soldiers seek solace not just in their faith but in the hope that divine mercy can help them navigate the moral chaos that war inevitably brings.

Photo by Yoal Desurmont on Unsplash

November 22, 2024

Recruiting – Review

Ewart Alan Mackintosh

‘Lads, you’re wanted, go and help,’

On the railway carriage wall

Stuck the poster, and I thought

Of the hands that penned the call.

Fat civilians wishing they

‘Could go out and fight the Hun.’

Can’t you see them thanking God

That they’re over forty-one?

Girls with feathers, vulgar songs –

“Washy verse on England’s need –

God – and don’t we damned well know

How the message ought to read.

‘Lads, you’re wanted! over there,’

Shiver in the morning dew,

More poor devils like yourselves

Waiting to be killed by you.

Go and help to swell the names

In the casualty lists.

Help to make a column’s stuff

For the blasted journalists.

Help to keep them nice and safe

From the wicked German foe.

Don’t let him come over here!

‘Lads, you’re wanted – out you go.’

* * * * *

There’s a better word than that,

Lads, and can’t you hear it come

From a million men that call

You to share their martyrdom.

Leave the harlots still to sing

Comic songs about the Hun,

Leave the fat old men to say

Now we’ve got them on the run.

Better twenty honest years

Than their dull three score and ten.

Lads, you’re wanted. Come and learn

To live and die with honest men.

You shall learn what men can do

If you will but pay the price,

Learn the gaiety and strength

In the gallant sacrifice.

Take your risk of life and death

Underneath the open sky.

Live clean or go out quick –

Lads, you’re wanted. Come and die.

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

You may find this and other poems here.

Analysis

Ewart Alan Mackintosh’s “Recruiting” gives us a soldier’s sharp and disillusioned perspective on the gap between the propaganda pushing young men to enlist and the grim reality of war. Through the soldier’s voice, the poem critiques not just the glorified messages on recruitment posters but also the hypocritical civilians who, from the comfort of their homes, eagerly cheer on the war while avoiding its dangers. The tone throughout is sarcastic, bitter, and darkly humorous, exposing the vast disconnect between the romanticized image of war and its brutal truth.

The central theme of “Recruiting” is disillusionment, as the soldier reflects on the hollow nature of the recruitment slogans that plague the public. The poem starts with a cynical view of the “Lads, you’re wanted, go and help” posters, which, when viewed from the soldier’s perspective, seem almost mocking. This phrase, repeated throughout the poem, becomes a cruel refrain that exposes the exploitation of young men sent off to fight a war they barely understand. For the soldier, these words hold no nobility or call to patriotism—they are merely a reminder of the growing list of casualties and the suffering ahead.

The first part of the poem criticizes civilians—specifically, the “fat civilians” and “girls with feathers” who, while singing patriotic songs and voicing support for the war, are completely removed from its harsh realities. The soldiers know that these civilians are safe from conscription, many being “over forty-one” or too removed from the frontlines to ever truly understand what it means to fight. Mackintosh uses sarcasm to highlight the ignorance and hypocrisy of these figures. The “fat old men” who wish they could fight the “Hun” are an example of people who romanticize war without any real willingness to endure its violence. Meanwhile, the “girls with feathers,” whose lighthearted songs about the war only serve to distract from the horrors, are depicted as disconnected from the true cost of the conflict. Through the soldier’s eyes, these expressions of support seem shallow and naïve, more about keeping up appearances than actual sacrifice.

As the poem unfolds, the tone shifts from mocking civilians to a more resigned bitterness. The soldier comments on how these civilians, despite their songs and slogans, are contributing to a war that will never touch them in the same way it will touch the men who actually fight. “Help to swell the names / In the casualty lists,” the soldier bitterly observes, highlighting how the war is reduced to numbers, to statistics that the media and civilians consume without ever facing the consequences themselves. The repeated refrain, “Lads, you’re wanted,” becomes increasingly ironic, as the soldier sees through the empty rhetoric and propaganda that encourage men to enlist. Each repetition feels less like a call to arms and more like a command to face inevitable death.

By the second half of the poem, Mackintosh contrasts the empty ideals of civilians with a more grim and realistic view of war. Here, the soldier offers a “better word”—not one of glory or honor, but of brutal truth. “Come and learn / To live and die with honest men,” he urges, acknowledging that while war may offer fleeting moments of nobility, the reality is one of suffering, sacrifice, and death. This is not a call to fight for country or glory; it is a bleak invitation to share in the martyrdom of those already at the front. In this section, the soldier’s voice grows more bitter as he sarcastically tells civilians to leave their empty patriotic songs behind and experience the true cost of war.

The final lines of the poem—”Lads, you’re wanted. Come and die”—are perhaps the most powerful. In these words, the call to arms is stripped of any remaining illusion of heroism or glory. The soldier, weary and resigned, recognizes that the recruitment message is not a noble cause but a brutal, inevitable cycle of death. There is no romanticized vision of war here—just the cold, harsh reality of what awaits those who heed the call.

Mackintosh’s use of repetition in the refrain “Lads, you’re wanted” reflects the relentless, almost hypnotic nature of recruitment messages. The structure of the poem mirrors the way these slogans are hammered into the public consciousness, growing more and more disillusioned with each cycle. The poet’s straightforward, almost colloquial style mirrors the bluntness of war itself—there is no room for idealized language when dealing with death and suffering. This creates a contrast between the hollow, distant patriotism of civilians and the raw, painful reality faced by soldiers.

Ultimately, “Recruiting” is a brutal critique of the societal forces that perpetuate war, from the recruitment posters to the civilians who, through their detached idealism, glorify conflict without understanding its true cost. Through the soldier’s biting humor and dark sarcasm, Mackintosh exposes the hypocrisy and ignorance of those who cheer for war from the sidelines, while leaving the real suffering to be endured by those who fight. The poem is a powerful reminder of the tragic disconnect between the idealized, romanticized view of war and the grim reality those at the frontlines face.

Photo by Library of Congress on Unsplash

November 21, 2024

Bring back the dragon – Review

Laired heavy on scales

atop diamonds and gold

wrapped in her tail;

she’s older than old.

her breathing is fire

her veins are from venom;

all the humans are liars

but lettered on vellum

is the spell to subdue

and bind her forever

to her treasure accrue

it’s a hero’s endeavour

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Bring back the dragon

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

“Bring Back the Dragon” flips the script on traditional fantasy storytelling, using a familiar mythic structure to critique not only modern cinema but also the suffocating grip of bureaucratic systems. The poem begins with an ancient dragon, a symbol of untamable power and danger, breathing fire and carrying venom in her veins. The dragon is old, wise, and overwhelming, setting the stage for what seems like a classic heroic struggle. But this is where the poem subverts expectations—it’s not brute force that defeats the dragon, but words. The hero uses a spell, a clever manipulation of language, to tame the beast. This twist transforms the usual narrative, where a hero defeats a creature through physical strength, into one where victory is achieved through intellectual cunning.

This shift from a traditional hero’s battle to a subjugation by bureaucracy offers a sharp critique of both modern storytelling and the structures that govern our world today. The hero, rather than slaying the dragon, binds her to her treasure with legal language and manipulation. There’s something almost transactional about this victory, a sign that the fight isn’t about overcoming pure evil, but managing systems that control and limit. It’s a reflection of how modern fantasy films and stories, particularly superhero movies, have become formulaic—heroes overcoming impossible odds in predictable ways, with no real depth or consequence. The thrill of a fierce battle with a dragon gives way to a much more mundane and bureaucratic process, mirroring how cinema today often rehashes the same old tropes without bringing anything new or original to the table.

Then, the poem shifts to a more cynical note. The hero’s supposed triumph gives way to a realization that the true enemy is not the dragon, but the system—the “committees” that now hold him in their grip. After all, the hero doesn’t go on to have grand adventures or rebuild the world in an epic fashion. Instead, he’s bogged down by political processes and red tape, an image that suggests bureaucracy is far worse than any mythical beast. The dragon, for all her power, is at least straightforward. You know what you’re facing. But committees, with their endless paperwork, delays, and confusing rules, are far more insidious. They drain energy, creativity, and ambition, creating a stifling environment where nothing ever truly changes.

This image of bureaucracy as a worse threat than the dragon is at the heart of the poem’s critique. While the dragon is dangerous, she’s clear in her purpose. The committees, however, are a web of obstruction that never ends. They represent a kind of bureaucratic beast that, in its endless complexity, keeps everything stagnant and bound. It’s a comment on how modern systems—whether in government, corporations, or even social structures—often become more oppressive than the very problems they were meant to solve.

The poem’s structure helps underline this shift from the grand to the mundane. The first few stanzas focus on the dragon’s immense power, using serious, almost mythic language to emphasize her ancient strength. But as the poem progresses, particularly in the final stanza, the tone lightens. The hero, no longer in the midst of an epic battle, is shown to be “stuck in committees”—a more relatable, less glamorous struggle that mirrors the frustrating realities of modern life. The grand adventure fades, and what remains is the dull grind of bureaucracy, which is far more suffocating than the immediate danger the dragon once posed.

Ultimately, “Bring Back the Dragon” is both a clever commentary on modern fantasy and a critique of the systems that hold us back. The poem suggests that perhaps we’ve lost touch with what made these stories powerful in the first place—the raw, dangerous, and uncontrollable forces of the world. Instead, we’re now stuck with systems that bog down any real change. The dragon may be asleep, but the poem implies that the real danger is the bureaucracy that holds everything in place. It’s not the mythical beast that we should fear, but the institutional systems that keep us trapped. In the end, we might long for the dragon’s straightforward menace, because at least it was honest about the danger.

November 20, 2024

Reflections – Review

Andrew Tait

Farewell, farewell you’ve gone to rest

your duty nobly done

the battle rages over you

but you sleep amidst the storm

I miss you in the billets

I missed you in the trench

but you fell for Britain’s honor

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

Andrew Tait’s “Reflections” captures the deep emotional complexity of war, focusing on the themes of loss and brotherhood. The poem is a tribute to a fallen comrade, reflecting on grief, memory, and the bond that soldiers share, forged under the intense pressures of World War I.

The theme of loss is central and immediate. From the opening lines, Tait sets the tone with “Farewell, farewell you’ve gone to rest.” The speaker’s sorrow is clear, but it is also mixed with a sense of respect and recognition that the comrade’s death was part of a larger, noble cause. “Your duty nobly done” places the loss in the context of war, where death is seen as an inevitable outcome of serving a greater good. However, despite this honor, the absence left by the fallen soldier is palpable. The speaker misses his comrade in the day-to-day struggles of the war, in the “billets” and “trench,” spaces where the soldiers spent much of their time. The poem underscores the depth of the loss, not just as the death of a friend but as the removal of a constant presence, leaving an empty space both physically and emotionally.

As the speaker reflects on the bond they shared, the theme of brotherhood becomes evident. This isn’t just about a soldier’s loss of a fellow fighter—it’s a personal loss of a friend, a brother. The use of “you” rather than a more distant “he” or “the fallen” brings the comrade down to the level of a close friend, someone who was there through every hardship. “We marched so many weary miles / and made our plans together” shows how their relationship wasn’t just about surviving the war but also about dreaming of a life after it. They were not just soldiers; they were companions with intertwined hopes for the future. When the speaker says, “But now at last I go alone,” it marks the devastating shift from a shared journey to one of isolation. The brotherhood is fractured by death, but even as the speaker must move on alone, he carries the memory and spirit of his comrade with him: “A comrade I shall ne’er forget, / you were ever by my side.”

The tone of the poem shifts between grief and acceptance. Early on, the speaker is overcome with loss, as he recounts his comrade’s death in the “smoke and stench” of battle. Yet, there is also a quiet determination that emerges, reflected in lines like “I must tarry here below, / the fight to carry on.” The speaker understands that death is part of the experience of war, and he acknowledges that his own time may come too. “But God someday will call me too” suggests a resignation to the inevitable, a belief that death is not something to be feared but an eventual reunion with his fallen friend.

Even in the face of this loss, the poem ends with a tribute to the fallen soldier’s memory. “A happy, cheerful soldier friend” captures the essence of who the comrade was—a source of joy and lightness amidst the horrors of war. The speaker’s final words honor the deep connection between them, one that even death cannot sever. The relationship is framed not just by shared military duty but by the affection and companionship that developed in the most difficult circumstances.

Through simple, rhyming quatrains, Tait’s structure mirrors the emotional tone of the poem. There is nothing ornate or overly complex about the form, reflecting the straightforward, honest grief of the speaker. The steady rhythm of the quatrains gives the poem a sense of continuity, almost as if the speaker is trying to hold on to the memory of his comrade while recognizing that life, and war, must move on.

In “Reflections,” Tait conveys the pain of loss but also the unbreakable bond between soldiers who endure together. The poem is a meditation on the deep connections forged in war and the emotional weight of losing someone who was more than just a fellow soldier. Through both loss and brotherhood, Tait shows how war shapes relationships, leaving behind memories that continue to guide those who survive, long after the battle is over.

Photo by Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa on Unsplash