Jose Vilson's Blog, page 13

January 22, 2019

MLK’s Work Precedes Us And, With Resilience, Lives After [Medium]

Yesterday, I had the opportunity to sit live at Riverside Church to watch a spirited conversation between writer Ta-Nehisi Coates and newly minted congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. For a little less than an hour, TNC and AOC spoke up and around the current state of affairs, rarely mentioning the person working from 1600 Pennsylvania. Ocasio-Cortez has seemingly busted open the Overton window for progressives, deftly maneuvering conservative talking points and offering no apologies. Coates, no stranger to heavy critiques from across the board, asked the questions the audience wanted to know from this Latinx supernova.

On the same platform that MLK Jr. gave us his “Beyond Vietnam” speech in 1967, we were asked to consider what “Beyond 2019” looked like for all of us. After the event, I offered the following:

In other words, we need to keep building an education movement that, at its heart, is responsive and adjacent to the anti-racism movements, the pro-immigration movements, the economic movements, and the anti-capitalism movements. Black Lives Matter at our schools and elsewhere. Our students have led us to DREAM better. We need to assure that corporations pay their workers decent wages, which often includes so many of our students. Teachers shouldn’t have to spend thousands of dollars to create affirming learning environments for our students to make up for society’s lack of will.

If there’s enough money to spend for the United States’ war on terrorism, there’s enough money to make sure our students can close the generational education gap.

To continue reading, click here. As educators, it’s incumbent upon us to sit in our power and rectify our country’s wrongs in whatever capacity we can.

The post MLK’s Work Precedes Us And, With Resilience, Lives After [Medium] appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

January 11, 2019

On Creativity and The Stories Our Schools Tell Themselves

Around each March, a few students say they can do my job better than me. At the end of the year, I let them mock the adults in the building for a bit before they graduate to high school. A few years ago, however, I decided to flip that challenge and gave them a lesson plan template to work from. They were interested in how they could get their class to learn. They’d create whole poster boards for their lessons and develop PowerPoint projects that they’d use to teach me. In May, they were a few days from presenting and teaching their classes.

A few adults walked in with power and gaze. One of them said, “Does this look like the kids are learning?” The question already prompted disapproval. Instead of asking for my lesson, asking my students, and watching them speak as if the learning was theirs, a few minutes passed by and a whole department and district would be pushed, prodded, berated, and prompted over the years and to this day to the traditional, rote pedagogy that would supposedly raise test scores and, ostensibly, learning.

With only a hint of irony in these adult voices, the call for creativity has rung louder recently. No. Don’t do that.

Creativity continues to float around the educational zeitgeist even as the ropes tighten the noose around our pedagogies. The move to emulate rigorous – the actual meaning of the word – instruction may have had good intentions. We assigned more numbers to what we felt the students learned. Graduation rates. College acceptance rates. Test scores. All of them. If these and other numbers attached to our status quo form of education dip or level out, our current inclination is to squeeze tighter, thus granting less freedoms. Our current education system does not believe in emancipation, and too many theories of practice use systems that double down on the oppression.

We love using words like “creativity” and “imagination” when we want to inspire adults, but never instill these words in the culture and framework of the schools. Our actions still yell.

How does it feel for a black educator who started his career as an openly creative mathematician to now feel himself subverting, bobbing, and weaving mandates while calls for creativity come to the fore? Frustrated is a word. Disoriented is another. It’s important to keep the eye rolls and snickers to a minimum. Questions like “Who gets to be seen as creative?” and “Why do students appreciate my classroom even as I feel as constricted as ever?” come to the fore.

Creativity in the classroom isn’t something you write as an objective or a standard, but how you’re able to play with the time that you’re not talking.

To wit, creativity is supposedly the most sought-after quality from employers in the new century. People have complained that creativity as a resource has been depleted by the uber-measurement era. College professors from on high have said their students are no longer as creative. Many op-eds have lamented the decline of society through millennials and their sui generis way of approaching the world. A new millennium with its leading people burnt out, and society keeps burning.

The question remains, however: why ask for a quality that our schools don’t invest in? And are we willing to fail in earnest?

Until then, keep writing those mission and vision statements. It’s all the same to me.

The post On Creativity and The Stories Our Schools Tell Themselves appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 30, 2018

Keep That Same Energy, Tho [2018 and Beyond]

“So what year are you?”

I hesitated. In circles like these, I’m usually the odd person out. People probably ask themselves qualification questions privately, as well. On any given day, I can represent the 3.6 million teachers of America, the 20% of teachers who identify as nonwhite, the 2% of Black male teachers, the 1% of Latinx male teachers, or just me. I’m usually invited to have the race conversation because that’s the necessary one, but sometimes, I rather have the easy one. Like math.

Normally, when I get questions doubting my purpose for attending a given space, I get real New York City hood. It’s usually an instance where I’d break into slang. “Wait, you deadass asked me that? Keep that same energy when …” followed by a few claps post-every word. The shoulders get raised. “You KNOW you’re not about that …” with scrunched eyes and menacing mouth twist. Even in professional settings, I might respond with a high road response and a sarcastic laugh.

It’s not that I’m unapproachable; it’s that I prefer my time be valued, especially if organizers requested (and paid for) my presence in a space.

Before I could start answering, my friend says, “Well, he’s not really in this group. He’s got a few books, a widely-read blog, tons of followers, a fellowship, and a National Board certification, so he really doesn’t need this.” After I prepared myself for another argument I didn’t ask for, I probably let out a timid “Thank you” and went about the rest of the evening floored that someone would go to bat for me like this. Another friend pulls me aside at an event that “folks are really mad because you’re self-made and they’re not. They gotta thank a random somebody from some office that they’re where they are.”

We should always be critical of sword-swallowers and disappearing card conjurers with titles.

I came off a school year where I had to battle my own school district because of my own teacher ratings. That meant for a whole year, I’d have a label on me that I neither earned nor could contest. While teachers of color often leave / get fired quicker than their white counterparts, those of us who remain in these schools still face policies meant to sever us from the students we serve and the work we must do. In this, I feel connected not just to the current set of educators, especially of color, across the country facing similar or worse conditions, but the droves of educators before my tenure who saw this coming, whose narratives never get told, who were ignored for the pyritic stories of wayward children saved by mostly white sympathizers.

Yet, and still, all of this pales in comparison to the context in which this work has become ever more critical. We have children, both immigrant and “native,” locked up for the reason of being “other.” We have children committing suicide, and many of them because our society has not deemed their gender identities appropriate. We have children who feel invisible and inhumane in their own schools and children who’ve disappeared off schools’ rosters after their district went private. We have children who’ve had their hair cut for sport, and children who had the police called on them for any number of reasons and no apparent reason all the same. We have children who only know the word “refuge” after their own countries were bombed the way smart phones ring across our collective homes from 5:30am to 7:30am on weekdays. We have children who will definitely be too ill-resourced to make the Earth hospitable to us after oligarchs destroy its resources in their excesses.

Oh, and we have racists, fascists, and xenophobes all up and down our government making decisions against and on their behalf. Dude, the Racist-In-Chief abides.

This acknowledgement seeps into our operations, too. We say we didn’t vote for fascism, but appreciate when our schools have expressionless, incurious, and obedient children. We equate success and learning with children who came milly rock and shoot dance only on command. We prefer them in lines, rows, and aisles sans the reasons we call excuses as to why they just won’t. We like schools that call disobedient children’s parents once an hour until it’s our child. We enroll our children in institutions with a clear theory of praxis even when said praxis is deleterious to their self-fulfillment. We negotiated our children down to where we’re A-OK if we lose a few.

Statistically, the loss of a few students perpetuates the inequity, but asserting our wokeness and putting up a Black Lives Matter poster in our windows works better than a hall pass.

Our pedestals do nothing if they don’t give us a macro view of the world we must impact. In every and any space I was passed the mic, I made sure to drive a message for these children who could not be in attendance and our responsibility to them. I treated every one of those conversations like I’d never get invited back and will continue to do so. The same organizations who kept proffering teacher voice finally got this teacher to keynote / present on a panel at their conferences. Nothing about us without us is for us, right? Observers and critics have their questions as to how these spaces that want teachers and never had one speak suddenly had one that would both attend and speak.

It’s simple. In mornings and afternoons, I teach my kids math. In the evening, I tell adults what it takes to make that happen. Alignment.

All I asked is that people match my energy this year. It’s life-affirming to have educators willing to teach in the very spaces America has left to rot and still find ways to ground that narrative for the rest of us. Everywhere I went, I found these hope bearers, educators who speak as if they taught the same students I did and wanted to change the course of their education. I may have created rifts between me and people who had no intention of hearing me out, but I built even more bridges with people who didn’t know which side of the rift they wanted to be on.

I learned that the best accolade was the one where my partners-in-arms across the country and the world felt like they could do this beautiful, powerful struggle work one more day.

A guide recently told me I’ve been asked to go from a fisher of fish to a fisher of people. I don’t know what that metaphor means, but 2018 felt like it was preparing me to assume the role of the person I need to be. For Alejandro. For Luz. For #EduColor. For my friends and fam. For the world around me. And, when I encounter the world, I hope it keeps that same energy.

The post Keep That Same Energy, Tho [2018 and Beyond] appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 24, 2018

A Book That Tells Teachers How To Talk About Race. No, Really. [Not Light But Fire]

Recently, a conversation flared up on Twitter. (That last sentence has become the new “a guy walks into the bar …” for online education activists, but more soon, maybe.) Mind you, at the end of 2017, I set a goal to minimize how many arguments I’d get into on Twitter in 2018, but I must have missed the fine print when I signed on that platform because I failed hard. Most folks have an argument on Twitter and get over it the next day. I participate on Twitter and I can guarantee the thread will continue a week later. This time, it happened between another education professional development leader in the field and a person who consistently discusses race issues on and offline.

Long story short: nobody won except racism. The practitioners who ask everyone to reflect on their practices did nothing to reflect about their racial relationships and the practitioners who do this race work daily took precious time explaining our lived experience to people who want to maintain our current racial paradigm.

In the middle of these difficult conversations, people always ask for the resource that will help them understand how to apply it into the classroom. Without fail, people bring up Beverly Daniel Tatum’s Why Are All The Black Kids …, Glenn Singleton’s Courageous Conversations …, and Lisa Delpit’s Other People’s Children. There are a few others. Some of the books do a solid job of charting some activities that can be integrated into simple or complex conversations. Some books are written by people of color with racial dynamics in mind, but don’t actually address race. Others still have equity and any other social justice buzzword integrated into the text, but still speak on race as if they were observing galaxies from a telescope.

Related: did you know that the light we see from other galaxies is probably millions and billions of years old so what we’re seeing is probably not relevant? Yeah, that.

Matthew R. Kay seeks to address this gaping hole with the book Not Light, But Fire: How To Lead Meaningful Race Conversations In The Classroom. The book starts off with a prelude that’s an ode to his imbued identities as a seasoned English teacher, as a slam poetry champion, and as an unapologetically Black man. After his introductory polemic “Talk is cheap,” he sifts through tidbits of the American race conversation to land upon what we consider “the conversation about the conversation.” He says:

[Frederick] Douglass knew what many are noticing now: that we never seem to graduate to the next conversation. The hard one. That we hide our stasis beneath puffed-up punditry and circular debate. He called for us to infuse our conversation with fire – to seek out and value historical context, to be driven by authentic inquiry, and above all, to be honest – both with ourselves and with those with whom we share a racial dialogue. Just as fire rarely passes through an environment without acting upon it, so too should our world be impacted by our students’ race conversation.

In the next chapters, he skillfully does three things:

He explicitly discusses conditions and dissuades the reader from using words like “safe space” uncritically.He pulls in student examples regularly and uses their voices as a way of pushing the narratives forward.He doesn’t make himself out to be the hero at all.

The last point is especially paramount. As I’ve said numerous times in this space, education “influencers” of all stripes have clamored for relevancy by weaving in mentions of equity, access, and social justice even when their legacy doesn’t suggest that they’ve put in the work in that front. Kay’s book challenges all of us to reconsider our current classroom practices and readjust ourselves to get maladjusted and discomforted so we can have this race talk. Current classroom teachers will find resonance in chapters like “The N-Word: Facing It Head-On.”

You get a sense that, if you asked Kay to swing at you, he’d take a few minutes to explain why he was going to swing at you with a full-knuckle fist, then do exactly that.

We should be so fortunate, too. Our classrooms deserve to have a book that directly lays out scenarios for us to consider. Obviously, critics will point to the fact that he teaches in one of the country’s most celebrated schools (Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia, PA) with a principal who allows a level of autonomy that most of us wouldn’t get if our admin walked by with their Danielson “not-a-checklist” checklists. Yet, as I was reading it on the train, I found myself immediately applying at least one of the techniques almost immediately into my own math classroom.

This book deserves a bigger audience, especially those who only recently found their social justice voice in the service of expanding their influence. If there is a tool to be given, this book is one. If people want to hire someone to actually lead conversations about race in 2019, I’m asking school districts to focus on folks who are ready to have the next conversation, the one that not only sail the surface of the racial ocean, but also willing to dismantle the rudders of the boat driving in it.

The post A Book That Tells Teachers How To Talk About Race. No, Really. [Not Light But Fire] appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 19, 2018

Just Take It Slow, We Got So Far To Go

On Monday, our students had a trip to the American Museum of Natural History. After a series of whip-arounds and semi-completed scavenger hunts, we entered the waiting area for the Neil deGrasse Tyson-narrated Dark Universe. Because I saw it this summer with my son, I had the utmost confidence in telling my students it would be the best movie they’ve seen on a school trip and went into a furious synopsis of what they were about to see. One student commented that I should be their science, social studies, ELA, and math teacher.

My colleagues probably didn’t take too kindly to hearing that from him, but I smirked a little.

After the trip, I dragged my feet back home. My shoes felt loose. My sweater felt too tight. I was walking by pushing my ankles forward, so I was walking slower than my body thought. I picked up my son from after school and, upon my return home, I sat on the couch and blacked out for a good 20 minutes. The accidental nap is one of the silver linings in getting older: I was made when I woke up, but happy it happened. It was also a sign that we’re officially in the grind months.

I’m tiiiired. Admitting it is the first step towards invincibility. And caffeine or whatever drug of your choice.

The easy thing is to pretend that we’re a 10 every time we step into the classrooms. We have well-prepared lesson plans. We kept our desks and rooms flawless. Pristine book collections and lightly-alcohol scented whiteboards without a trace of work residue add flourish to our rooms. Our clothes have no wrinkles, our hair perfectly combed, coiffed, or groomed. Our voices never crack and the winter medley of diseases hasn’t stripped our voices of volume and clarity.

Our souls don’t erode at the sight of another “failed” assessment, an unchanged and negative relationship with a student, an adverse observation from our administration, a meeting gone awry. We walked into our rooms and, when any number of people strayed from our expectation, we bounced right back and didn’t take it personally even when it kept happening to our person. Those of us in positions of authority don’t feel overextended and can multitask with octopus-like adroitness.

We feed ourselves lies as appetizers for our half-enjoyed meals midday.

Luckily, a prophet by the name of Michael Jackson once said decades ago, “Just take it slow. We got so far to go.” The idea that we always have it together came from any number of teacher-ed books, teacher evaluation expectations, images of our colleagues whose classrooms we don’t stay in for longer than 20 minutes, and our own expectations. It hurts when we don’t meet our self-notions, so we avoid it through edubabble and redirection.

I’m learning to sit in this pain. How foolish are we to think that having 30 energetic children in front of us soaking up our energies wouldn’t leave us depleted. Why search deep into the universe’s seemingly endless dark matter when we can barely fathom the deepest recesses of ourselves? What’s more, the majority of us have until late spring to early summer. We’re smarter for holding on to a little something so we can restore ourselves at the start of the new year.

It takes us embracing that which makes us human, thus error-prone. It frees us from the responsibility of pretense. Our kids get to appreciate that scene, too.

The post Just Take It Slow, We Got So Far To Go appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 9, 2018

Learning and Earning In This Era of Education Justice

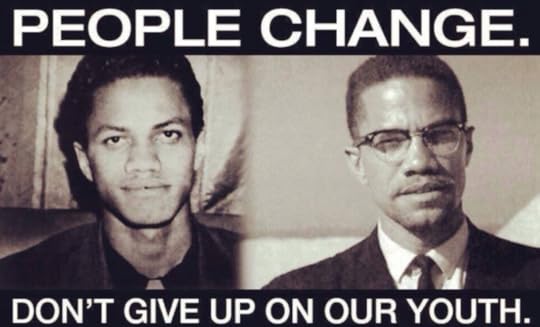

This year, as with every year, I’ve hung a little poster of both Malcolm Little to Malcolm X / el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz with the tagline “People Change: Don’t Give Up On Our Youth.”

When I’m seated at my desk in the morning, it’s positioned so it’s slightly above my head. Curious students ask who the boy and the man are and why I decided to buy that poster. A student might chime in “That’s Malcolm X” while other students might not chime in at all.

The grumpy old man in me, trained in black liberation thought back in college and exposed to so many of the greats of the Civil Rights era, might have belted out a “YOU DON’T KNOW WHO THAT IS?” The teacher in me said, “Well, he was someone special” and build my case accordingly.

Suppressing the urge to not do as some of my elders did has gotten exponentially easier over time, a function of empathy and actual social justice. Another part of it is knowing that students need the time to let these ideas and people foment before actualizing knowledge of the struggles to win the rights they may not fully comprehend. For adults, it also means that we understand that the work for justice did not find its genesis in us. We’re stewards for the movement forward and we hold the past for lessons and guidance.

Learning and earning in education has so many implications for our students and their schools, but we’re reluctant to use over-abused words like status quo.

The current era of what we consider justice work has proven even more perilous with the economic shift towards neoliberalism and individualism. Neoliberalism has been defined a billion different ways, but a handy set of characteristics include austerity, privatization, market-based solutions, and the focus on the uplift of one or a handful as stewards for these ideas. The term itself has lost popularity these days thanks in large part to global and domestic uprisings, but the elements within our capitalist society remains. Also, as we’ve seen with movements in the past, our society can more readily handle the rise and fall of one individual who fervently or reluctantly takes on leadership of a movement than a collective mass who’ve offered a new model for governance.

In education, this has been even more unsettling. While we can argue whether education policy and practice have changed dramatically in the last few decades, we still haven’t discussed the simplest yet most complex question facing our schools today: what is an education? We have – pardon the pun – so many schools of thoughts, we might never get to a single solution. Yet, it seems to me that moving folks along a continuum that suggests all of our students deserve an equitable education and it will take some personal and institutional sacrifices to do so is our most arduous task. As I’ve stipulated in the past, we can provide equitable resources to every school, assure highly qualified (and highly paid) educators get staffed in the neediest schools, and re-envision our school spaces. As long as one school is viewed as predominantly white while another is viewed as predominantly Black / Latinx / Asian / Native-American-First-Nation, inequity will always reign.

This is even exemplified in who’s taken up the mantle of “leadership” in education today. Of course, there’s a difference between authority as an official position in a recognized institution or organization [management, for argument’s sake] and leadership as a set of affirmations and permissions granted to someone on a micro and macro scale. In this era of social justice work, influenced in large part by movements like Black Lives Matter / Occupy Wall Street / Fight for 15 / DREAMers, equity came to the fore for educators in the Obama era.

From within education, plenty of educators, parent groups, and scholars had a hand in keeping the justice boat afloat before the wave came in, many of whom I consider mentors and colleagues. Even when they held no formal leadership positions, their thought formations and galvanizing created a foundation for the current set of education justice groups like EduColor, Black Teacher Project, and Black Lives Matter at School to influence otherwise resistant folks. Most of this work was done through grassroots efforts and often against the will of administrators who oversaw the decimation of our teaching workforce diversity.

But now, not only has it gotten more popular, it’s gotten more profitable. One of our current presidential administrator’s greatest accomplishments might be that he pulled white supremacists out from hiding. The other side effect might also be that those who don’t consider themselves supremacists have gone scurrying to putting on the veneer of anti-racism. Thus, people who had rarely uttered the word “equity” were now forcing themselves into incorporating the words into the vocabulary.

The white folks with massive followings have been the most interesting case to watch. The same folks who thought they inoculated themselves from issues that people of color suddenly found their following asking them questions about what to do. Some clumsily cobbled together words about black kids they once knew while others pulled in the people of color closest to them for cover while others never needed said cover because they sought to do the work before it became relevant.

Ostensibly, our education economy only allows for a handful of leaders at a time, and too many of us still see leadership as the person placed in front of us by the economy. Where this leadership model fails miserably is ensuring that the voices of students, parents, and educators in our most marginalized communities get equitable power through democratic and liberating solutions. Folks feel the need to signal virtues of justice in their blogs, podcast, books, and other wares where they did not care to before. For folks who’ve done said work without remuneration, this shift breeds real contempt because we saw how quickly those gates went from a simple key to combination locks and deadbolts. We’ve seen so many of our colleagues’ lives and livelihood sacrificed for the greater fight and how that was rarely if ever acknowledged.

We see how neoliberalism allows for the wealthy to buy up space in a movement and sit themselves in that space. And the droves of followers who uncritically co-sign the malarkey.

Marian Dingle’s recent essay lays out how averse our white brethren are to that transfer of power. Too many of us want to be perceived as allies to the work without changing the structure and placement of the seats we’ve been bestowed. Even people of color with orientations centered on funders, pundits, and scholars who like the power “the way it is” can get caught up in the machinations.

It’s not too much to ask white people to shout out the folks who taught them how to speak in anti-racism. It’s not too much for all of us to shout your friends and fam in your books and presentations like the back of the liner notes in a rap / R&B CD. It’s not too much to pass on a speaking engagement or an article writing gig to a person currently in schools, especially our most marginalized schools. It’s not too much to check in on folks who, even in the fight for justice, have made time to organize with or without pay. It’s not too much to check our enthusiasm and assumptions before jumping in at the chance to flex our presumed wokeness in favor of asking good questions and prompting discussions with one another.

It’s OK for the powerful to redistribute their power so we can all model the sort of world our students see, especially those of us who see students daily. It’s OK for us to see ourselves as the leaders we’ve been waiting for and adjust our worldview accordingly. In this work, it’s the only way our world progresses.

The post Learning and Earning In This Era of Education Justice appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 6, 2018

Actually, Yes, I’m About To Sing Hamilton At This Event

Recently, Math for America asked NYC science teacher Lynn Shon and me to co-speak at their annual Fall Function also known as Nerd Prom. It was awkward because the function is held at the Marriott Marquis, close to the Richard Rodgers Theatre. For those unaware, the theatre is home to the original Hamilton musical. Also, I never went to my high school prom. The event is usually a serious affair and I had every intent of changing that dynamic.

It meant that, actually, yes, I was about to sing a Hamilton medley with the help of Ms. Shon.

I was so glad to have Math for America’s support in our new vision for our speech. I especially loved how we got to be our most authentic selves, even when we remixed Lin-Manuel Miranda’s magnum opus.

It was appropriate that the best rendition of the speech was the one we did in front of everyone. We created the speech with the people in front of us in mind.

The post Actually, Yes, I’m About To Sing Hamilton At This Event appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

December 3, 2018

You Don’t Have To Like It (Students Watch and Talk About Us, Anyways)

A few times a month, I’ll be on the whiteboard, jotting down examples for my lesson with my back turned to my students. The students find ways to distract themselves (while believing they have nothing to copy down along with me, but that’s another story). I let them rock until I’m turned back around and then they know it’s go time. Today, however, I took the opportunity to listen in when one student said: “School sucks.” I didn’t stop them. In fact, they went off for about two minutes and my ad libs were as follows:

“Oh, word?”

“Yo, for real.”

“Nah, I hear that.”

“Um, I can’t talk about that. When you graduate, I’ll holla. Not now, though.”

“No, not saying you’re not graduating, but yeah, that’s too old.”

We took our students’ feedback for granted. If you ever want to know how a school is doing, you don’t have to ask the adults. Ask them if you wish. Well, most of them. Look at the reports and the jumble of quantitative data on any number of Excel spreadsheets. You don’t even have to necessarily visit the school, though that’s my #2 indicator, really. We could visit a school, get a peek at the gorgeous bulletin boards, and lay out gridded curriculum early and often. We can look at the accolades splayed near the entrance and the artwork on the walls. We can check the website with its responsive design and glossy photos, too.

And, if you want to know how a school’s doing, ask the students.

Our society vastly undervalues student opinion as a matter of course. In the way of efficiency and so-called rigidity, we continually push for institutions that force schooling upon students, not education for and with students. Even those of us who proffer liberation and freedom talk still serve schools, if not promote schools, that need students to sit down, shut up, and take these quotes from icons of liberation and freedom movements of yore. Discipline has its place and so does human expression. The tension about student opinion is ultimately about showing the discipline to hear things that might make us as adults maladjusted.

Or we can keep lying to ourselves that 12-14 years of militaristic schooling methods will allow students self-determination.

Adults can often lie to themselves. We can make the moves assigned to them. We lay out their data and action plans for other adults to see. We bring in other adults that – under pressure – will vouch for our competence. We focus on the aesthetic to dissuade the nitpickers. We pull up our chins and speak with a bass in our voice to invoke authority. We create as many filters as professionalism allows, many of which protect us from scrutiny, from vulnerability, from the pain that our optimism was slowly but surely decimated by individual and structural choices made around us, by us, and for us. We’re so complicated and have a hard time owning that, due in no small part to the nature of our profession.

Failure comes in degrees and sometimes, it’s scalding in our chairs and stools.

Some might say that we shouldn’t ask every student about their opinions, to which I’d contest that these stories matter as well. We should listen to the students who excel and the students who struggle in equitable measure. At some point, we start to see patterns in their narratives that could inform our thinking. Our students have stories to tell, and many of them are about us as adults. Even the majority of students who “lie” to us relent and get to the heart of their frustration eventually.

But this also depends on the relationships we have with students.

My main class this year inadvertently reports on the schools happenings all around me in the morning when they leave their coats and in the afternoons when they leave. Some yell at each other about the NBA and the latest sneakers while others take selfies on Snapchat (“Hey, put that away!” a loud adult says, then smiles) and jump at their friends for a hug. They usually approach my desk since my music is anywhere between Meek Mill and Beyoncé. They don’t want me to take it personally (“OK, this is awkward”) but they can’t stand school nor math nor any of this nonsense. Yes, the synonym for nonsense. I give a few teacher glances and let them interpret my face for each other. Then, I hear whether I’m doing the job I’m supposed to, who I’m reaching, and who I still have ways to go before I got them.

I don’t give them the impression that they have to lie to me for their grade. If anything, their opinion is the goal. Some schools don’t hear it because they refuse to. Other schools don’t hear it because they don’t. I rather be the latter without reservations.

The post You Don’t Have To Like It (Students Watch and Talk About Us, Anyways) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

November 18, 2018

I Put In Work And It’s All For The Kids [An NCTE Reflection]

Just before I got home, I turn on DMX’s “X Gon’ Give It To Ya” because it matches the BPM I need to make it through the length of JFK International Airport corridors. As I get off the umpteenth moving sidewalk, DMX rapped:

“I’ve been doing this for 19 years.

Cats wanna fight me? Fight these tears.

I put in work, and it’s all for the kids,

But these cats done forgot what work is.

They don’t know who we be,

Looking, but they don’t know who they see …”

Headline reads: “Typical NYC Guy Sheds Half a Tear Before Dealing with Queens Traffic.”

This idea we call “professionalism” has so many of us holding our tongues and acting out of character. For instance, we have misinterpretations of a framework meant ostensibly to wrest control from control as praxis. I have , but I’m not a fan of using dimensions of a rubric to play games with someone’s passions and duties. This and many more elements are the burdens I don’t wish upon future students and educators, but here we are. When higher-ups hold schools under hostage for the express purpose of keeping appearances and test scores up, we lose any number of social and cultural norms that makes schools palatable to our kids.

If we don’t give students opportunity to express themselves, why should we expect them to perform? The same goes for our educators and parents.

So when we find spaces to convene, like the National Council of Teachers of English Convention, we savor the moment to share experiences with colleagues who want to teach students, regardless of subject area. These institutional spaces might feel “too white.” Large education conferences are merely a reflection of the profession as a whole. But, unlike so many other conferences, the NCTE experience leans on rock-star educators and pop culture authors aligned to their work. Jason Reynolds and Elizabeth Acevedo flow naturally with the plethora of teachers who created classrooms collections based on their works. NCTE can invite Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Daniel Jose Older, and Marley Dias and still have folks who could equally take those keynote slots and have them in the exhibit fall or a workshop instead. Their benches are deep with talent in a way that other conferences aren’t.

Which made this year interesting because they also invited a science / hip-hop pedagogy guy and a current math classroom teacher to keynote as well.

Hundreds of white educators (and the rest of us, too) stood at attention when Christopher Emdin’s prompted us to not be “consumed by or concerned by” the gaze of another. Riveting. I, however, needed to sit with that sentiment. How much was that outside gaze – through formal and informal observation or workshop and speech – affecting what I know to be true of my own classroom?

At my best, I’m less concerned with assuring that the right words show up on my lesson plan and more concerned with the revelations of inquiry and the interplay of children’s minds with the math they’re learning. At my worst, I worry about survival and becoming another exemplar of study on the lack of racial diversity in the teaching profession. On a daily basis, the implicit and explicit job descriptions we abide by and the contracts we’ve signed mire the revolutionary / oppressor dichotomy in complications.

We are intensely problematic, whether we’ve been granted a stage in front of other learners or not.

A few hours later, it was my turn to wax poetic. I thanked Shekema Silveri and the whole NCTE crew for passing the mic to a math teacher. I included a fresh set of GIFs, a few touch points that would hopefully build bridges between the attendees and their respective departments, and a new framework for how we discuss math in society. [Yes, I’m probably writing a book on it.] More important than the content was my approach, unapologetically hood / Dominican / Haitian / Black with some infusion of the Geto Boys, Beyoncé, and Johnny Cash. The pedagogy felt natural.

After signing a bunch of copies of This Is Not A Test: A New Narrative or so while taking selfies with colleagues, I felt affirmed in both the work I was doing with children and the work I am doing to inspire others to do the same. None of this comes without faults and responsibilities, but leading with these flaws allow us the mirrors and windows we so desperately need for all of our students.

And the rest of us learners, too.

A math teacher at an English conference shouldn’t be weird because we all teach children, not subjects or labels (gifted and talented, special ed, English language learners, etc.). Specificity is important and we need some collective principles about our understandings of the work. Our disciplines are but avenues for our approaches and relationships to the work. Of course, I also came into that conference as a best-selling author, a parent of a burgeoning reader, a loving partner of an administrator and English as a New Language expert, a parent who was once labeled an English as a Second Language student, a person who’s conversational in two languages (and any number of dialects within those languages), and one of the few published teacher-writers in the largest school district in the country.

None of these matter if I don’t share that power with folks who also do truly powerful work, especially those in the English teaching space.

A few hours later, I’m already thinking about my own students, the ones so easily discarded. Some are currently playing Fortnite, taking selfies on Snapchat and Instagram, or following whatever LeBron James / Kevin Durant / Steph Curry are doing. They may or may not be getting ready to do their school work tomorrow. They’re deciding whether they’ll make it to school on time or if they’ll be a few minutes late. An empathy of language would mean that, when students walk into my classroom, I’d leave myself open enough to their feelings and woes, I’d create space for students to express their understanding of the material in front of them, and I’d let my full self emanate from the walls. I like to read my students before they read my objective and Do Now.

I shouldn’t have to fight to be that. The ways that our students read each other and how we perform are the collective implicit literacy, and this educational literacy would be universal.

Let us put in work for and with all of my kids.

The post I Put In Work And It’s All For The Kids [An NCTE Reflection] appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

November 13, 2018

There’s A War Going On Inside We Ain’t Safe From [A Conversation with Lorena Germán]

Jose Vilson: Recently, there’s been some conversation as to whether or not our schools should be compared to war. Lots of folks, for example, say that teachers are the “people in the trenches.” On the other hand, it’s hard for me to not make the comparison between our contemporary versions of war and our schools. What say you?

Lorena Germán: Using language that makes our schools out to be war zones is a complicated matter. On the one hand, I’m always weary of those terms because it’s often used as coded language to signify schools that are located in communities where people of color predominantly live. Schools in suburbia are rarely discussed in this light. The language places teachers as martyrs (therefore advantaged in our collective conscience), and in these communities, those teachers are overwhelmingly white females. These martyrs are victims of the students (mainly Black and Brown ones) attacking them and each other, producing chaos, or a war. That perspective justifies the need for police officers in schools, zero tolerance policies, violent disciplinary measures, and more.

Also, it’s locating the problem in the wrong place and that is the other side of the coin of this conversation. Looking at our schools as war zones can be used strategically to reveal the war waged on our students of color, their communities, and their teachers. I’m referring to oppressive policies that maintain the historic abuse of white supremacist schooling on our communities of color. These are policies and pedagogical methods that demand students and their families assimilate, instead of celebrate. They demand students be seen as less than human and their parents as problems to be solved. These policies and methods would never be used in other districts where predominantly White students attend.

In the middle of all this, is the reality that our schools are over-policed and the physical environment is very much like a prison or war. There are metal detectors, police officers, dark colors on the walls because of old buildings and lack of funding, students being tackled, tasers, expulsions, walking on the line, eyes down, penalties, detentions, rules upon rules, and more. Our schools therefore, are prisons, they are war zones, but not for the reasons we often discuss.

A question for you: What do you think it takes to change this?

JV: It’s gotta start with the reframing of the statement: “War doesn’t belong in our schools.” We should ask, “Where do I see elements of combat in our schools?”

A part of me feels weird as well, because war has so many different implications. Coming from countries where police literally have tanks strolling through the streets, it’s fascinating to think how many teachers have the privilege of never having to deal with remnants of our seemingly endless wartime at this juncture. Also, I’m finding that too many of the people who aren’t OK with using war-like metaphors in schooling simultaneously refuse to advocate for every school in a given area to be stripped of metal detectors, police roaming the halls, and any number of surveillance measures for our most marginalized youth. By the way, these are conditions they wouldn’t accept for their own children.

Ultimately, I’m starting to see a few different divides with schools: ones that treat our kids like human beings and ones that don’t, and those seem to span our current categories for schooling. What were you thinking?

LG: Pointing out that these are conditions they wouldn’t accept for their own children is crucial! It’s infuriating, too, because it makes the work of bringing about change so much harder. It feels impossible when it’s just a few voices calling out the injustice and the majority isn’t too concerned because the issues are on “other people’s children.” (Shout-outs to Delpit!) I agree that there’s a current trend revealing a stark gap between schools that humanize and schools that dehumanize.

One way to change a lot of this is by shifting narratives. The truth is that a lot of “reform” is concerned about changing classroom practices, or schools, or students. We certainly need to change classroom practices in order to humanize all students. Schools definitely need some re-envisioning. Students are not the problem, so I’ll never localize the issue within them. While we certainly need to improve how we teach and support who we teach, it is necessary to address where and why we teach. I think that looking at and addressing the systems of inequity in our country is where we will find our solutions. Then, thinking about why teachers are standing in front of kids, why teachers are making the choices they’re making, why folks are choosing to dedicate their lives to education will be integral to figuring out how to move forward.

Why do you teach, Jose?

JV: I started to teach because I wanted to open doors for my students, to give them opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have. Now, I’m finding myself constantly questioning this prospect. If I’m teaching, where am I guiding them? Some of my students have become teachers, police officers, engineers, and other municipal workers. It’s also true that these professions make us agents of the state. If the system works exactly as it’s designed, then we’re accomplices to all of this, despite our best efforts. If the system has enough cracks in it to allow for the promise of greater democracy, participation, and equity, I hope I’m doing my best to make it so for my students.

I teach not simply because I’m one of the only – if not the only – Black teachers they’ll have in their entire PK – 12 career, but also because I like to believe I can show my students paths to humanity and ways of being that aren’t self-destructive. I believe in a world, like you, that would eventually eradicate the idea of “other people’s children.” We got a stake in this. As parents and educators, the responsibility is multiplied.

You?

LG: Whew! I also began because I wanted to open doors for students. In fact, I used to use that exact phrase. I want to believe that I have done more and continue to do more. I believe that I teach in order to free myself, free others, and create paths for a better society. It’s very idealistic, but it’s grounded in truth and working toward change. I free myself by being the type of teacher I never had and repairing the relationship between me and school. I try to create space in my classroom and school so that we can interrogate our systems and work diligently to dismantle oppression. I do believe that education is one of the steps in that process. I believe that my role within education is to enact a curriculum and approach that works toward freedom. I have to believe this. I have a dream, and I can’t let it dry like a raisin in the sun.

Ya dig?

The post There’s A War Going On Inside We Ain’t Safe From [A Conversation with Lorena Germán] appeared first on The Jose Vilson.