Sandra Byrd's Blog, page 21

August 23, 2012

Blog Hop! An Enduring Tudor Mystery: What happened to Mary Seymour?

Thank you for joining the Historical Fiction blog hop! The giveaway for this site is a signed copy of The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr along with a gold-plated book mark of Kateryn Parr. Please enter any comment below, in the “leave a reply” section at the end of the blog post about Mary Seymour, in order to enter the drawing. US/Canada only, please. And be sure to visit the other blogs on the hop!

___

Queen Kateryn Parr, courtesy of wikimedia

Lady Mary Seymour was the only child of Queen Kateryn Parr and her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour. Parr died of childbed fever shortly after giving birth to Mary, and the baby’s father, Thomas Seymour, was executed for treason just a few short years thereafter. But what happened to their child, who seems to have vanished without trace into history? This is an enduring mystery.

The last known facts about the child include that her father, Thomas Seymour, did ask as a dying wish, that Mary be entrusted to Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk and that desire was granted. Willoughby, although a great friend of Mary Seymour’s mother, Queen Kateryn Parr, viewed this wardship as a burden, as evidenced by her own letters. According to Parr’s biographer Linda Porter, “In January, 1550, less than a year after her father’s death, application was made in the House of Commons for the restitution of Lady Mary Seymour…she had been made eligible by this act to inherit any remaining property that had not been returned to the Crown at the time of her father’s attainder. But in truth, Mary’s prospects were less optimistic than this might suggest. Much of her parents’ lands and goods had already passed onto the hands of others.”

The 500 pounds required for Mary’s household would amount to approximately 100,000 British pounds, or 150,000 US dollars today, so you can see that Willoughby had reason to shrink from such a duty. And yet the daughter of a Queen must be kept in commensurate style. There were many people who had greatly benefitted from Parr’s generosity. None of them stepped forward to assist Baby Mary.

Biographer Elizabeth Norton says that, “The council granted money to Mary for household wages, servants’ uniforms, and food on 13 March, 1550. This is the last evidence of Mary’s continued survival.” Susan James says Mary is, ” probably buried somewhere in the parish church at Edenham.”

Most of Parr’s biographers assume that Mary died young of a childhood disease. But this, by necessity, is speculative because there is no record of Mary’s death anywhere: no gravestone, no bill of death, no mention of it in anyone’s extant personal or official correspondence. Parr’s biographer during the Victorian ages, Agnes Strickland, claimed that Mary lived on to marry Edward Bushel and become a member of the household of Queen Anne, King James I of England’s wife.

Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, courtesy of wikimedia

Various family biographers claimed descent from Mary, including those who came down from the Irish shipping family of Hart. This family also claimed to have had Thomas Seymour’s ring which was inscribed, What I Have, I Hold, till early in the twentieth century. I have no idea if that is true or not, but it’s a good detail and certainly possible.

According to an article in History Today by biographer Linda Porter, Kateryn Parr’s chaplain, John Parkhurst, published a book in 1573 entitled, Ludica sive Epigrammata juvenilia. Within it is a poem that speaks of someone with a “queenly mother” who died in childbirth, child of whom now lies beneath a marble after a brief life. But there is no mention of the child’s name, and 1573 is twenty-five years after Mary’s birth. It hints at Mary, but does not insist.

Fiction is a rather more generous mistress than biography, and I was therefore free to wonder. Why would the daughter of a Queen and the cousin of the King not have warranted even a tiny remark upon her death? In an era when family descent meant everything it seemed unlikely that Mary’s death would be nowhere definitively noted. Far less important people, even young children, had their deaths documented during these years; my research turned up dozens of them.

Sudeley Castle, Mary Seymour’s birthplace, courtesy of wikimedia

Edward Seymour requested a state funeral for his mother, as she was grandmother to the King (which was refused). Would then the death of the cousin of a King, and the only child of the most recent Queen, not even be mentioned? The differences seem irreconcilable. Then, too, it would have been to Willoughby’s advantage to show that she was no longer responsible for the child if she were dead.

The turmoil of the time, in which Mary’s uncle the Lord Protector was about to fall, the fact that her grandmother Lady Seymour died in 1550, and the lack of motivation any would have had to seek the child out lest they then be required to then pay for her upkeep, all added up to a potentially different ending for me. The lack of solid facts allowed me to give Mary a happy ending in my novel, The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr, an ending I feel is entirely possible given Mary’s cold trail, and one which I feel both “Kate” and Mary deserved.

July 11, 2012

Our Tudor Sisters

Historical novelists are sometimes suspected of importing twenty-first century values into sixteenth century novels. While it’s true that most authors seek to connect their readers with their novel’s women of the past, it isn’t necessary to ascribe new values to past women.

They valued education. Although medieval women’s education was often limited to gentler feminine arts such as dance, needlework, and playing of the lute or virginals, by the beginning of the Tudor era women were much more interested and involved in intellectual education. Queen Catherine of Aragon ensured that her daughter, Mary, had a strict regimen of demanding studies in accordance with her own upbringing. Sir Thomas More is often credited with putting practice to the idea that non-royal women deserved as much education as noble or highborn men. His daughters undertook an education complete in classical studies, languages, geography, astronomy, and mathematics.

Queen Kateryn Parr

Queen Kateryn Parr’s mother, Maude, educated her own daughters in accordance with More’s program for his children, eventually running a kind of “school for highborn girls” after she was widowed. Eventually, educating one’s daughters was seen as a social necessity and men expected their wives to be able to play chess with them, discuss poetry and devotional works, and be conversant in the issues of the day.

They knew they couldn’t marry for love – the first time – but desired it anyway. Most historical readers understand that women in the Tudor era were chattel, legally controlled by their fathers and then their husbands. They married for dynastic or financial reasons; marriage was an alliance of families and strategy and not of the hearts. And yet, these women, too, had read Song of Songs wherein a husband and wife declare their passion for one another. Classically educated as they were, Tudor women had surely come across the Greek myths, including Eros and Psyche, and perhaps had even read the medieval French love poem, Roman de la Rose.

Mary Rose Tudor

If a woman was left widowed – and that happened quite often – she was free to remain widowed and under her own authority or to marry whom she wished. Henry VIII’s sister Mary, married first King Louis XII of France, for duty. When he died, she married Charles Brandon, for love. After Mary’s death, Brandon married his ward, Katherine Willoughby, her duty. Later, she married Richard Bertie for love. Kateryn Parr married three times for duty, including her third husband, King Henry VIII. Her fourth marriage, to Thomas Seymour, was for love.

They were working women. High born women were often ladies in waiting to the queen, a demanding, full time job with little pay and time off. They ran the accounts for their husband’s properties and juggled household management. Kateryn Parr’s sister, Anne, served in the household of all six of Henry VIII’s wives. Some highborn women, such as Lady Bryan, became governesses. Lower born women were lady maids, seamstresses, nurses, servants, or baby maids in addition to helping their husbands as fishmongers or in the fields.

Although there are some notable differences, we have much more in common with our high born sisters of five hundred years ago than one may think!

June 16, 2012

Palace of Whitehall

King Henry VIII wanted the biggest and the best – and he desired to have the most sumptuous royal dwellings in all Europe. He certainly set the standard with the fifteen-hundred-room Palace of Whitehall. Standing in the center of London, the original dwelling was known as York Place. Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey, was the last of the Archbishops of York to occupy York Place. During his tenure at the dwelling, originally built to be close to the royal residence at Westminster, Wolsey greatly enhanced York Place. Visitors to the Archbishop’s home mentioned hundreds of rooms filled with velvet, silk and cloth of gold. Keep in mind that Cardinal Wolsey had more than eight hundred persons in his household.

King Henry VIII wanted the biggest and the best – and he desired to have the most sumptuous royal dwellings in all Europe. He certainly set the standard with the fifteen-hundred-room Palace of Whitehall. Standing in the center of London, the original dwelling was known as York Place. Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey, was the last of the Archbishops of York to occupy York Place. During his tenure at the dwelling, originally built to be close to the royal residence at Westminster, Wolsey greatly enhanced York Place. Visitors to the Archbishop’s home mentioned hundreds of rooms filled with velvet, silk and cloth of gold. Keep in mind that Cardinal Wolsey had more than eight hundred persons in his household.

A major shift in tenants, and palace name, came in 1530 when Henry VIII seized the property as Cardinal Wolsey fell into disgrace. Henry was also motivated by the fact that he had been living “temporarily” at Lambeth Palace since Westminster had been heavily damaged by fire eighteen years earlier. Whitehall Palace at the time of Henry VIII was an immense complex on the banks of the Thames just north of Westminster Palace. Here the luxurious apartments, intriguing “pleasure complex” and magnificently landscaped parklands provided the ambitious king with a residence worthy of his station. It, like him, grew to be very large indeed.

It became known as the Palace of Whitehall, and was to be the principal residence of English monarchs for the next one hundred fifty years. Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were married at the Palace of Whitehall in 1533, and he married Jane Seymour there in 1536. Henry himself died at Whitehall in 1547, though he did not allow his wife, Kateryn Parr, to accompany him there in his final illness – she was sent to Greenwich and never saw her husband alive again. The original Banqueting House was built for the coronation of Elizabeth I in 1559; she enjoyed Whitehall and had a magnificent library there. Famously, Charles I was executed on a scaffold in front of the palace’s new Banqueting House in 1649; he wore warm clothes so that the onlookers would not mistake his shivering for trembles of fear.

In Henry’s day, the magnificent Whitehall Palace was surrounded by twenty three acres of ornamental gardens and parklands. On one side of the road to Westminster, which bisected the property, sat plush royal apartments, a chapel and the Great Hall. Drawings of this part of the palace complex show dozens of stained glass windows among brightly-painted red bricks with white stonework. The soaring towers, tall windows and many gables of the Tudor style were evident in Henry’s renovation of the central London palace.

Because Henry VIII, and his son and daughters after him, always lived in comfort, the royal apartments would have been draped with fine tapestries and lavishly furnished. Meeting rooms such as the King’s Privy Chamber were filled with treasures presented to Henry by his loyal subjects and visiting heads of state.

What Henry built across the road, conveniently accessed through one of two covered galleries known as the Holbein and King’s Gates, reveals much about the King’s character. Henry VIII enjoyed sport of every kind, and so he built a tiltyard for jousting, a large viewing gallery, bowling greens, a cockpit and tennis courts. His daughter Elizabeth enjoyed cockfighting and bear baiting, too.

Although by 1691 The Palace had become the largest and most complex in Europe, it began a steady decline thereafter thourgh fires and demolition. Today, only the Banqueting House remains mostly intact, though parts of the old Palace exist, folded, neatly and aptly, into the Whitehall government buildings. A portion of the roof of Henry VIII’s wine cellar still lies, carefully preserved, the basement of the Whitehall complex. Toast him, or not, if you visit!

May 9, 2012

Citrus Tarts

Citrus Tarts

Citrus Tarts

Serves 6

Here’s the challenge, read it: I warrant there’s vinegar and pepper in’t.

Twelfth Night, 3, 4

I doubt your guests will guess that these refreshing tarts contain both pepper and vinegar, two flavors not ordinarily associated with dessert. Peppercorns, popular since the time of ancient Greece and Rome, were often included in sweet dishes in Shakespeare’s day. In Medieval times this valuable spice was traded as money. “Peppercorn rent”, a legal term for a symbolic or nominal payment, is still used in England today.

4 large naval oranges

3 lemons

2 tablespoon butter

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground 5 color peppercorns

3 teaspoons fresh ginger, minced

3 tablespoons sugar

1/2 cup white wine

2 tablespoons verjus or white wine vinegar

1 tablespoon honey

15 ready-made tiny phyllo tart shells, (1 inch diameter)

Using a vegetable peeler, but the peel from the oranges and lemons, removing any of the white pith. Soak the peels for 10 minutes in cold water. Drain and coarsely chop the peels.

Melt the butter in a medium saucepan. Add the peels, pepper, ginger, sugar, and wine, and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer for 30 minutes.

Allow the mixture to cool to room temperature and stir in the verjus and honey.

Spoon the filling into the tart shells and serve.

© Shakespeare’s Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook by Francine Segan.

March 28, 2012

Beef Purses

Beef Purses

Beef Purses

Serves 8

I picked and cut most of their festival purses; and had not the old man come in with a whoo-bub against his daughter and the king's son and scared my choughs from the chaff, I had not left a purse alive in the whole army.

A Winter's Tale, 4, 4

In Shakespeare's day, meat turnovers like these were called "purses" because they looked like the small change holder people wore attached to their belt. The expression "cut purse" referred to a thief who cut the cord to steal the purse, an all too common occurrence in those days before policed streets.

The savory filling of tangy candied ginger and sweet dried fruit make these purses worth stealing! Enjoy them with a glass of cold ale before heading off to see your favorite production of Shakespeare or while watching one of the many great movies inspired by his work.

8 ounces ground round or ground sirloin

1/4 teaspoon ground rosemary

1/3 cup currants

6 dates, finely chopped

1 tablespoon finely chopped candied ginger

1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground nutmeg

2 tablespoons light brown sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

Pinch of freshly milled black pepper

pie dough, homemade or store bought

1 large egg, beaten

Place the beef, rosemary, currants, dates, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, brown sugar, salt, and pepper in a bowl and mix well. Refrigerate for at least 6 hours, or overnight. Remove the meat from the refrigerator 1 hour before baking.

Preheat the oven to 350° F. Roll out the Renaissance Dough 1/8 inch thick on a floured work surface. Using a 3-inch round ring cutter, cut out 24 dough circles. Place 1 1/2 tablespoons of the meat mixture onto each circle, fold in half, and pinch the edges to seal. Brush the purses with the egg and place on a well-greased, nonstick baking sheet. Bake for 15 minutes, or until golden brown.

Original recipe: To make pursses or Cremitaries

Take a litle mary, small raysons, and Dates, let the stones bee taken away, these being beaten together in a Morter, season it with Ginger, Sinemon, and Sugar, then put it in a fine paste, and bake them or fry them, so done in the serving of them cast blaunch powder upon them:

The Good Husewifes Jewell, 1587

© Shakespeare's Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook by Francine Segan.

March 19, 2012

Anne Boleyn’s Gatehouse?

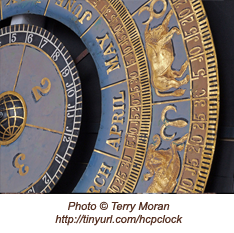

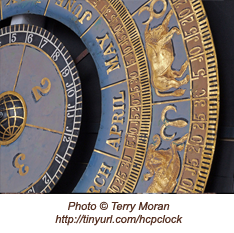

When most visitors arrive at Hampton Court Palace, they come through the stately gatehouse near the second, inner court, on the “Tudor side” of the palace. Once at the gatehouse, the eye is first drawn to is the astonishing astronomical clock that still functions in spite of being more than five hundred years old, although its mechanisms have been replaced at least once. According to Simon Thurley in his book, Hampton Court Palace, the clock not only tracks the time of day, it shows the phases of the moon, displays the month and quarter of the year, the date, the sun and star signs, and uniquely, the high water at London Bridge. Tidal information was especially important to those visiting by barge from London, as at low water London Bridge created dangerous rapids.

When most visitors arrive at Hampton Court Palace, they come through the stately gatehouse near the second, inner court, on the “Tudor side” of the palace. Once at the gatehouse, the eye is first drawn to is the astonishing astronomical clock that still functions in spite of being more than five hundred years old, although its mechanisms have been replaced at least once. According to Simon Thurley in his book, Hampton Court Palace, the clock not only tracks the time of day, it shows the phases of the moon, displays the month and quarter of the year, the date, the sun and star signs, and uniquely, the high water at London Bridge. Tidal information was especially important to those visiting by barge from London, as at low water London Bridge created dangerous rapids.

The gatehouse and rooms around the clock are also well known as they were the sumptuous chambers of Anne Boleyn. They were adapted for her as she, understandably, didn’t want to use Katharine of Aragon’s old rooms, which stand directly opposite hers – an interesting juxtaposition. The gatehouse is known today as Anne Boleyn’s gate, and sadly, work was still underway on Anne Boleyn’s apartments above that gate on the day the King had her executed. Her rooms today have been enveloped by, ironically, the Young Henry Exhibit as well as parts of the gift shops. However, as romantic as the notion may be, the gatehouse would not have been called Anne Boleyn’s Gate during the Tudor period. Alas, the name allegedly comes from the Victorian period, as do the entwined H&As in its ceiling.

Anne Boleyn's Gatehouse?

When most visitors arrive at Hampton Court Palace, they come through the stately gatehouse near the second, inner court, on the "Tudor side" of the palace. Once at the gatehouse, the eye is first drawn to is the astonishing astronomical clock that still functions in spite of being more than five hundred years old, although its mechanisms have been replaced at least once. According to Simon Thurley in his book, Hampton Court Palace, the clock not only tracks the time of day, it shows the phases of the moon, displays the month and quarter of the year, the date, the sun and star signs, and uniquely, the high water at London Bridge. Tidal information was especially important to those visiting by barge from London, as at low water London Bridge created dangerous rapids.

When most visitors arrive at Hampton Court Palace, they come through the stately gatehouse near the second, inner court, on the "Tudor side" of the palace. Once at the gatehouse, the eye is first drawn to is the astonishing astronomical clock that still functions in spite of being more than five hundred years old, although its mechanisms have been replaced at least once. According to Simon Thurley in his book, Hampton Court Palace, the clock not only tracks the time of day, it shows the phases of the moon, displays the month and quarter of the year, the date, the sun and star signs, and uniquely, the high water at London Bridge. Tidal information was especially important to those visiting by barge from London, as at low water London Bridge created dangerous rapids.

The gatehouse and rooms around the clock are also well known as they were the sumptuous chambers of Anne Boleyn. They were adapted for her as she, understandably, didn't want to use Katharine of Aragon's old rooms, which stand directly opposite hers – an interesting juxtaposition. The gatehouse is known today as Anne Boleyn's gate, and sadly, work was still underway on Anne Boleyn's apartments above that gate on the day the King had her executed. Her rooms today have been enveloped by, ironically, the Young Henry Exhibit as well as parts of the gift shops. However, as romantic as the notion may be, the gatehouse would not have been called Anne Boleyn's Gate during the Tudor period. Alas, the name allegedly comes from the Victorian period, as do the entwined H&As in its ceiling.

March 3, 2012

Ladies in Waiting

Having close friends is an important part of the female experience from girlhood through womanhood. These friends might be especially valuable when the woman's position is exalted, public, and potentially treacherous — such friendships take on an even more important role. When Oprah Winfrey started her empire she brought along Gayle King. When Kate Middleton was preparing to become Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge her sister Pippa was her constant companion. And when Anne Boleyn went to court to stay she took her friends, too. Among them was her longtime friend, who would ultimately become her chief Lady and Mistress of Robes, Meg Wyatt.

Having close friends is an important part of the female experience from girlhood through womanhood. These friends might be especially valuable when the woman's position is exalted, public, and potentially treacherous — such friendships take on an even more important role. When Oprah Winfrey started her empire she brought along Gayle King. When Kate Middleton was preparing to become Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge her sister Pippa was her constant companion. And when Anne Boleyn went to court to stay she took her friends, too. Among them was her longtime friend, who would ultimately become her chief Lady and Mistress of Robes, Meg Wyatt.

Ladies in waiting were companions at church, at cards, at dance, and at hunt. They tended to their mistress when she was ill, or anxious and also shared in her joy and pleasures. They did not do menial tasks — there were servants for that — but they did remain in charge of important elements of the Queen's household, for example, her jewelry and her clothing. They were gatekeepers, and during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I small bribes were often offered to her ladies for access to Her Grace. The Queen was expected to assist her maids of honor in becoming polished and finding a good match, and they were in turn to be loyal and obedient. Married women had more freedom, better rooms, and usually, closer contact with the queen.

In her excellent book, Ladies in Waiting, Anne Somerset quotes a lady-in-waiting to Queen Caroline as saying, "Courts are mysterious places … Intrigues, jealousies, heart-burnings, lies, dissimulations thrive in (courts)as mushrooms in a hot-bed." This is exactly the kind of place where one wants to know whom one can trust. Somerset goes on to tell us that, "At a time when virtually every profession was an exclusively masculine preserve, the position of lady-in-waiting to the Queen was almost the only occupation that an upperclass Englishwoman could with propriety pursue." Although direct control was out of their hands, the power of influence, of knowledge, of gossip, and of relationship networks was within the firm grasp of these ladies. Appointment was not only by the personal choice of the queen or the king, but a political decision as well. Queen Victoria's first stand took place when her new Prime Minister, Robert Peel, meant to replace some of the ladies in her household to reflect the bipartisan English government and keep an even political balance. According to Maureen Waller in Sovereign Ladies, Victoria was adamant. "'I cannot give up any of my ladies,' she told him at their second meeting. 'What, Ma'am!' Peel queried, 'Does your Majesty mean to retain them all?' 'All', she replied."

Keeping the political balance in mind was a concern during the Tudor years, too. Ladies from all of the important households were appointed to be among the Queen's ladies, though she held her closest personal friends in closest confidence. Of course Queen Katherine of Aragon understandably preferred the ladies who had served her for most of her life right till her death. Henry told his sixth wife, Queen Kateryn Parr that she may, "choose whichever women she liked to pass the time with her in amusing manners or otherwise accompany her for her leisure." Parr chose like-minded friends when she could. Queens often surrounded themselves with family members, hoping that they could trust in their loyalty because as the queen gained more influence, so advanced her family.

Sadly in Queen Anne Boleyn's case, family seems to have been less than worthy of her generosity and trust. Among those thought to have betrayed her in the end were her sister-in-law, Jane Parker, Lady Rochford, and some of her Howard relatives. Among those better deserving of her friendship were the Wyatt sisters and Nan Zouche, all of whom shared Anne's joie de vivre and reformist sympathies, and remained true friends to her till the end.

January 21, 2012

Bough Breakers

There was an historic snow and ice storm in my town this week. Our home backs up to a thickly wooded area, so we watched the fir trees become slowly enrobed in snow and the deciduous trees become, twig by twig and branch by branch, sheathed in ice. The most fascinating thing about this process is how weightless a solitary snowflake or a drop of water is, and yet how much damage can be wrought when there are hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of them piling up upon one another.

There was an historic snow and ice storm in my town this week. Our home backs up to a thickly wooded area, so we watched the fir trees become slowly enrobed in snow and the deciduous trees become, twig by twig and branch by branch, sheathed in ice. The most fascinating thing about this process is how weightless a solitary snowflake or a drop of water is, and yet how much damage can be wrought when there are hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of them piling up upon one another.

Within a few days, the mighty trees began to weary. The deciduous, bereft of the ability to bend and yield, became brittle and snapped at the least blow of the wind. Whole branches abruptly snapped off, leaving a forest of amputees. The firs, more flexible, held up better, but they also were more generous in catching and collecting snow, and after a certain weight, they, too, fell. The trees that seemed to make it all right were those who were able to lean into a mightier tree nearby, resting until the wind and snow stopped and the sun melted away their great load.

Within a few days, the mighty trees began to weary. The deciduous, bereft of the ability to bend and yield, became brittle and snapped at the least blow of the wind. Whole branches abruptly snapped off, leaving a forest of amputees. The firs, more flexible, held up better, but they also were more generous in catching and collecting snow, and after a certain weight, they, too, fell. The trees that seemed to make it all right were those who were able to lean into a mightier tree nearby, resting until the wind and snow stopped and the sun melted away their great load.

I thought how this reminded me of our Christian faith. We are not exempted from the ice that suddenly delivers many tiny, stinging troubles that pelt and pile upon us till we are ready to snap and break. Nor are we excused from heavier loads. This is not heaven yet. But we are given a promise, that we have Someone we can lean upon, upon whom we can rest and transfer the weight of our cares and sorrows. He props us, as it were, till the stormy cycle passes (and it always does) and our burdens melt away, allowing us to stand true and straight again.

"Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest."

Matthew 11:28

January 3, 2012

Hever Castle, Childhood Home of Anne Boleyn

Sandra Byrd

Sandra Byrd

with Kate Eaton

Surrounded by a double moat, this historic castle began life as a lowly farmhouse on land awarded to Walter de Hevere by William the Conqueror in 1066. In 1270, Walter de Hevere's grandson, William, built an impressive stone gatehouse and bailey on the site of the farmhouse. Tall, crenellated twin towers flanked the gatehouse, featuring cross-shaped arrow slits, a portcullis and a drawbridge to defend the castle. St. Peter's Church at Hever is adjacent to the castle, and dates back more than eight hundred years.

The Boleyn connection to the castle began in 1459, when the property came into the hands of Geoffrey Bullen. Bullen was a wealthy mercer, or dealer in expensive fabrics, who became Lord Mayor of London the same year. His rise in prominence, first as an alderman and then as Lord Mayor, would have required Sir Geoffrey to maintain a home befitting his station. He was responsible for transforming the stone fortification into a comfortable and impressive Tudor dwelling for his family. Geoffrey Bullen's son, William, inherited the castle from his father, and then in 1505 passed it down to his own son, Sir Thomas Boleyn.

Historians don't agree on whether or not Anne Boleyn was born at Hever Castle, but it's certain she lived at least part of her childhood there. It isn't hard to imagine Anne and her siblings, Mary and George, running through the ancient bailey walls, strolling along the nearby River Eden and exploring the imposing twin towers. Most certainly, the sturdy walls of the castle's Long Gallery were the site of many leave-takings as both Anne Boleyn and her sister, Mary, traveled back and forth from England to France. An interesting architectural note, common among the great homes of this era—the sisters' bedrooms were actually quite small and cramped in comparison with Hever Castle's public rooms.

There were no doubt dozens of servants in a house this size, not only to care for the Boleyns and their home, but also to attend to the large stables and expansive grounds at Hever Castle. The expectation that the Boleyn family would entertain traveling nobility expanded the household regularly. Henry VIII, himself, did eventually come to this castle in the English countryside. Under the bows of an ancient oak, King Henry made known his affection for the fascinating Anne Boleyn. He would visit Hever Castle several times during his pursuit of Anne. This lovely castle with a fascinating history remained in the Boleyn family until the death of Thomas Boleyn in 1539, at which time it reverted to the Crown. Hever was among the properties Henry awarded to his wife Anne of Cleves when he divorced her.

Resources:

http://www.hevercastle.co.uk

http://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/castles/hever.shtml