Sandra Byrd's Blog, page 19

July 10, 2014

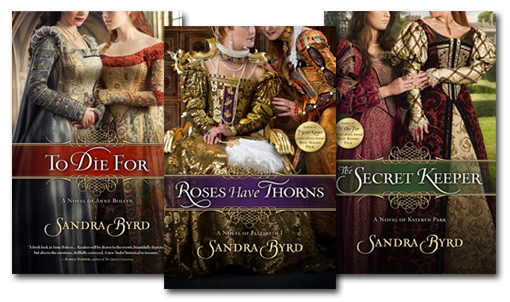

An Enduring Tudor Mystery: What happened to Mary Seymour?

Queen Kateryn Parr, courtesy of wikimedia

Lady Mary Seymour was the only child of Queen Kateryn Parr and her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour. Parr died of childbed fever shortly after giving birth to Mary, and the baby’s father, Thomas Seymour, was executed for treason just a few short years thereafter. But what happened to their child, who seems to have vanished without trace into history? This is an enduring mystery.The last known facts about the child include that her father, Thomas Seymour, did ask as a dying wish, that Mary be entrusted to Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk and that desire was granted. Willoughby, although a great friend of Mary Seymour’s mother, Queen Kateryn Parr, viewed this wardship as a burden, as evidenced by her own letters. According to Parr’s biographer Linda Porter, “In January, 1550, less than a year after her father’s death, application was made in the House of Commons for the restitution of Lady Mary Seymour…she had been made eligible by this act to inherit any remaining property that had not been returned to the Crown at the time of her father’s attainder. But in truth, Mary’s prospects were less optimistic than this might suggest. Much of her parents’ lands and goods had already passed onto the hands of others.”

The 500 pounds required for Mary’s household would amount to approximately 100,000 British pounds, or 150,000 US dollars today, so you can see that Willoughby had reason to shrink from such a duty. And yet the daughter of a Queen must be kept in commensurate style. There were many people who had greatly benefitted from Parr’s generosity. None of them stepped forward to assist Baby Mary.

Biographer Elizabeth Norton says that, “The council granted money to Mary for household wages, servants’ uniforms, and food on 13 March, 1550. This is the last evidence of Mary’s continued survival.” Susan James says Mary is, ” probably buried somewhere in the parish church at Edenham.”

Most of Parr’s biographers assume that Mary died young of a childhood disease. But this, by necessity, is speculative because there is no record of Mary’s death anywhere: no gravestone, no bill of death, no mention of it in anyone’s extant personal or official correspondence. Parr’s biographer during the Victorian ages, Agnes Strickland, claimed that Mary lived on to marry Edward Bushel and become a member of the household of Queen Anne, King James I of England’s wife.

Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, courtesy of wikimedia

Various family biographers claimed descent from Mary, including those who came down from the Irish shipping family of Hart. This family also claimed to have had Thomas Seymour’s ring which was inscribed, What I Have, I Hold, till early in the twentieth century. I have no idea if that is true or not, but it’s a good detail and certainly possible.According to an article in History Today by biographer Linda Porter, Kateryn Parr’s chaplain, John Parkhurst, published a book in 1573 entitled, Ludica sive Epigrammata juvenilia. Within it is a poem that speaks of someone with a “queenly mother” who died in childbirth, child of whom now lies beneath a marble after a brief life. But there is no mention of the child’s name, and 1573 is twenty-five years after Mary’s birth. It hints at Mary, but does not insist.

Fiction is a rather more generous mistress than biography, and I was therefore free to wonder. Why would the daughter of a Queen and the cousin of the King not have warranted even a tiny remark upon her death? In an era when family descent meant everything it seemed unlikely that Mary’s death would be nowhere definitively noted. Far less important people, even young children, had their deaths documented during these years; my research turned up dozens of them.

Edward Seymour requested a state funeral for his mother, as she was grandmother to the King (which was refused). Would then the death of the cousin of a King, and the only child of the most recent Queen, not even be mentioned? The differences seem irreconcilable. Then, too, it would have been to Willoughby’s advantage to show that she was no longer responsible for the child if she were dead.

The turmoil of the time, in which Mary’s uncle the Lord Protector was about to fall, the fact that her grandmother Lady Seymour died in 1550, and the lack of motivation any would have had to seek the child out lest they then be required to then pay for her upkeep, all added up to a potentially different ending for me. The lack of solid facts allowed me to give Mary a happy ending in my novel, The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr, an ending I feel is entirely possible given Mary’s cold trail, and one which I feel both “Kate” and Mary deserved.

June 16, 2014

Mist of Midnight: Daughters of Hampshire, Book One

I am delighted to announce the launch of a new series: Daughters of Hampshire. There will be three books, Gothic romances all, which take place in Victorian England. Book 1, Mist of Midnight, will debut in March 2015. What do you think?! Please sign up for my mailing list, below, so I can let you know when the book is available and enter you into any contests run! I’ll be drawing five names from among the sign ups for a free advance copy of the book plus a Victorian lace book mark to be sent early next year.

Sandra’s newsletter sign up: Click Here

In the first of a brand new series set in Victorian England, a young woman returns home from India after the death of her family to discover her identity and inheritance are challenged by the man who holds her future in his hands.

Rebecca Ravenshaw, daughter of missionaries, spent most of her life in India. Following the death of her family in the Indian Mutiny, Rebecca returns to claim her family estate in Hampshire, England. Upon her return, people are surprised to see her… and highly suspicious. Less than a year earlier, an imposter had arrived with an Indian servant and assumed not only Rebecca’s name, but her home and incomes.

That pretender died within months of her arrival; the servant fled to London as the young woman was hastily buried at midnight. The locals believe that perhaps she, Rebecca, is the real imposter. Her home and her father’s investments reverted to a distant relative, the darkly charming Captain Luke Whitfield, who quickly took over. Against her best intentions, Rebecca begins to fall in love with Luke, but she is forced to question his motives–does he love her or does he just want Headbourne House? If Luke is simply after the property, as everyone suspects, would she suffer a similar fate as the first “Rebecca”?

A captivating Gothic love story set against a backdrop of intrigue and danger, Mist of Midnight will leave you breathless.

April 17, 2014

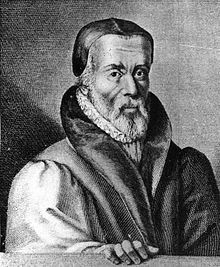

William Tyndale

A Guest Blog by Kate Eaton

The copy of scripture read most commonly by Anne Boleyn and Kateryn Parr in Sandra Byrd’s Ladies in Waiting series, and by Sandra herself as she wrote the books, was William Tyndale’s translation. Tyndale played a central role in the English Reformation by being the first to translate the Scriptures from the original Hebrew and Greek into English and make them available to the common man. Born in Gloucester, England around 1494, Tyndale received his degrees from Oxford and was ordained a priest.

William Tyndale

Except for what has been recorded by British historian John Foxe in his ‘Book of Martyrs’, not much is known about William Tyndale as a young man. He is said to have developed a reputation at Oxford for enlightening fellow students privately as to the truth of Scriptures, which was not popular with the established Church at the time.

We know that after leaving Oxford, Tyndale spent time at Cambridge and then was hired by Sir John Walsh of Gloucestershire as a tutor for his children. One benefit of this humble occupation was the opportunity to discuss theology and philosophy with the religious scholars who regularly visited Sir Walsh’s estate. During that time, the young priest also began preaching publicly in Bristol and surrounding villages, often criticizing the more questionable practices of the Church.

[image error]

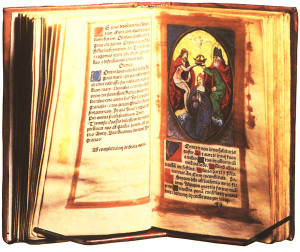

Anne Boleyn’s copy of Tyndale’s “Newe Testament.”

Early in his career as a priest, Tyndale embraced the mission of directly translating the Bible into English, but that first required the approval of a bishop. Refused permission by Bishop Tunstall in London, William Tyndale was forced to flee England and worked for a time with Martin Luther at Wittenburg, Germany.

An important early English theologian and philosopher, John Wycliffe, had already overseen the translation of the Vulgate, a fourth century Latin translation of the Bible, into English during the 14th century. Wycliffe’s early work to make the Scriptures available to the common man was to be a major influence on Tyndale. In 1526 as a young priest, Tyndale completed the first translation of the New Testament from the original Greek and Hebrew into common English language. Printed at Cologne, Germany, these New Testaments were smuggled into England over the next few years, enraging the Bishops as well as Henry VIII.

For the next ten years, Tyndale suffered deprivation, shipwreck, loss of his manuscripts, and the constant threat of arrest for heresy by order of King Henry VIII. During those years, many English men and women embraced Reform theology, thanks to the now easily-understood Scriptures, fueling a violent, chaotic era in Europe. During those terrible days, nobles and common men alike became involved in the struggle between traditional Christianity and the new Reform.

William Tyndale was able to complete a revision of his New Testament translation and also an English-language version of the first five books of the Old Testament by 1530. It was printed in large numbers, thanks to the newly-available printing press, and was smuggled into England and widely distributed by itinerant preachers. While working on further translations in Antwerp, Belgium, Tyndale was betrayed in 1535 by Henry Phillips, an Englishman. He was imprisoned for over a year, despite attempts by Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s Vicar General, to have him freed. In October 1536, William Tyndale was strangled and then burned at the stake for heresy near Brussels, Belgium, by order of Henry VIII. His associates Myles Coverdale and John Thomas completed his translation of the Old Testament soon after Tyndale’s death.

Ironically, although King Henry had ordered Tyndale’s death for the crime of heresy because he dared to translate the Scripture into everyman’s language, Henry later commissioned four English translations of the Bible!

After the publication of Tyndale’s translation of the Bible, the idea of the Scriptures in common language could not be denied. Both Roman Catholics and Protestants fueled the further availability of the Bible in a language even the uneducated could understand.

Three important versions followed – the Puritan’s ‘Geneva Bible’, the Anglican Bishops’ Bible and the Doway Catholic English Bible. James I of Scotland, in an attempt to bring peace among the religious factions of the day, commissioned in 1611 a new version with its roots in Tyndale’s translation. This version became known as the ‘King James Bible.’

Without the courage and perseverance of early translators of the Bible such as William Tyndale, the Scriptures might never have become available to the common people. Anne Boleyn’s velvet bound, 1534 copy of William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament can be found today in the British Library.

Research Sources: TudorPlace.com.ar; Tyndale.org; Christian Assemblies International; Christianity Today; PBS.org

March 14, 2014

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn

Friends often want to share good things with each other and I have a new treasure I want to share with you, a book written by my friend Natalie Grueninger and her co-author Sarah Morris. It’s billed as a visitor’s companion to the palaces, castles & houses associated with Anne – and that’s exactly what it is. Reading the book is almost like walking a pilgrimage of sorts, stopping at significant way stations in Anne’s life.

For those of us fortunate enough to visit England once or more, or for English readers themselves, this is the perfect travel guide to plan, anticipate, and understand an actual visit. For the rest of us, this is an irreplaceable armchair companion-guide to any Tudor fiction you may read. The book is organized chronologically so the reader feels immersed in Anne’s life, progressing through it with her.

Blickling Hall

The book is rich and detailed, managing to broadly cover history, architecture, religion, social classes, and royal families while carefully examining small scale concerns such as clothing, family and friendship, and, truly important to understand the times, motivations. It manages to be both expansive in coverage and intimate in delivery.

I love revisiting familiar places such as Hever Castle, Hampton Court Palace, and of course, the Tower of London. Some of my favorite chapters, though, covered places important in Anne’s life but not quite as widely covered: Blickling, Eltham, and, tantalizingly, Wolfhall. The care given the research allowed me to disappear into the book confident in its authority. The details wooed me with charm. This is a book that should be on every Tudor lover’s bookshelf and will certainly remain close at hand on mine.

Please pop over to amazon.com or amazon.co.uk and have a look. If you’d care to leave a comment below, and like Natalie’s Facebook page, On the Tudor Trail, I’ll enter you into a worldwide contest for a London Starbucks Card worth $25 US dollars, or local equivalent.

January 10, 2014

Elizabeth I’s Beloved Locket Ring

She held the realm’s finances in her grasp and the crown jewels round her neck or on her head, but there were only two pieces of jewelry that Queen Elizabeth I was reliably said to have never removed: her coronation ring, which she considered to be her “wedding” ring, and her ruby and pearl locket ring. This latter ring, shrouded in mystery, tells us as much about the queen’s heart as does the former.

The ring is generally referred to as the Chequers ring because its permanent home is now at the British Prime Minister’s country home, Chequers, and under the authority of its trustees. In 2008, Prime Minister Gordon Brown lent out several pieces of art from Chequers to the museum at country house Compton Verney. Kathleen Soriano, head of exhibitions at Compton Verney, said of the ring, “It’s a very moving piece because it’s so delicate and small and really evokes the sense of the story. It’s a very powerful object.”

Just what is that story evoked?

Most sources place the first appearance of the locket ring at 1575. Although some assert that the queen had it commissioned, there is no trail or definitive provenance for that claim. Traditionally, lockets are gifts. Inside might be a portrait of a lover or a child, or perhaps a lock of hair from someone who had passed on. The idea is to keep close to heart someone who is likely far removed by death or convention, politics, or sea. The idea, too, is to be able to shield or shroud the identity of the loved one by clasping and keeping the locket closed.

@ National Museums Scotland

English locket jewelers Lily & Will tell us that, “When Elizabeth I wore a locket ring … it marked a new beginning for the locket. It started to rise in popularity as Elizabeth I gave gifts of jewel encrusted lockets to many of her favourite loyal subjects—Sir Francis Drake being one of them.” The Scottish National Museum holds among its collection a locket with portraits of Mary, Queen of Scots and her son James, given to a trusted servant on the eve of her execution. Then who is to be found inside of the ring so cherished by Queen Elizabeth? Another royal, executed mother, and her beloved only child. When opened, the Chequers ring reveals two portraits which face one another. One is clearly Queen Elizabeth, seemingly in her early forties, neatly fitting with the year 1575. The second portrait is widely understood to be her mother, Queen Anne Boleyn.

Because there is no direct provenance, there has been speculation that the portrait could be of the young Queen Elizabeth herself, or even of Queen Kateryn Parr, Elizabeth’s stepmother. It’s unlikely that the queen would have worn two portraits of herself throughout her life and in any case, there would have been no need for those portraits to be kept hidden. Although Elizabeth bore tender affection for Parr, the portrait within does not clearly resemble Parr, nor does the French hood worn by the subject fit in with the French hoods known to have been worn by Parr. It does, however, perfectly match the French hoods Anne Boleyn was well known for.

The British Museum says of Anne Boleyn: “Of the mid-sixteenth century representations of her, the most reliable must be the tiny miniature set into a ring of about 1575 which belonged to her daughter, queen Elizabeth I (The Chequers Trust; see ‘Elizabeth’ exhibition catalogue edited by Susan Doran, London, The National Maritime Museum, 2003, no.7). This likeness comes from the same source as the painting in the National Portrait Gallery.”

The British Museum says of Anne Boleyn: “Of the mid-sixteenth century representations of her, the most reliable must be the tiny miniature set into a ring of about 1575 which belonged to her daughter, queen Elizabeth I (The Chequers Trust; see ‘Elizabeth’ exhibition catalogue edited by Susan Doran, London, The National Maritime Museum, 2003, no.7). This likeness comes from the same source as the painting in the National Portrait Gallery.”

The NPG portrait is widely understood to have been painted by John Hoskins the elder (c.1590-1664/5). Boleyn’s principle biographer Eric Ives believes that it is “more likely that Hoskins had access to an earlier image of the kind from which the NPG image originated.” In essence, perhaps there was one early portrait or sketch that both Hoskins and the painter of the locket miniature based their work upon.

Although Elizabeth likely could not remember what her mother looked like, there were those at her court old enough who would remember, and there were also those who still held quiet affections for and perhaps an illustration of Queen Anne. And just like that, the generosity of fiction allowed me to consider who might have loved and understood Elizabeth enough to risk giving her a ring with a portrait of her beloved, but taboo, mother inside.

Please leave a comment below to be entered into a drawing to win a Queen Elizabeth I Coronation notebook as well as a bar of the Queen’s Chocolate, the preferred chocolate for royal everyday divas!

December 6, 2013

Five Fantastic English Christmas Traditions We Yanks Should Adopt

Stir It Up Sunday: Celebrated on the Sunday before Advent, the terms is drawn from the opening words from the day in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer of 1549. “Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people; that they, plenteously bringing forth the fruit of good works, may of thee be plenteously rewarded; through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

Many recipes for English Christmas puddings (desserts, often baked) call for the mix to be fixed and then rest for several weeks before being served; ladies and their cooks would therefore prepare their hearts – and their meals – for the Advent and Christmas season. Wouldn’t hurt me to do a little baking, and heart preparation, in advance.

Christmas Crackers are not vehicles for tidbits of the Christmas Cheese ball! Instead, they are snappy little rolls that ‘crack’ when two people tug them apart like a wishbone… and find a delightful surprise inside. Wrapped in Christmas paper, they are a festive way to convey a tiny gift of any kind; traditionally they included a joke and a paper crown and who can’t use more laughter and bling? Today, crackers may also include a love note, a tube of lip gloss, some cuff links, an engagement ring, or anything you can imagine!

Christmas Crackers are not vehicles for tidbits of the Christmas Cheese ball! Instead, they are snappy little rolls that ‘crack’ when two people tug them apart like a wishbone… and find a delightful surprise inside. Wrapped in Christmas paper, they are a festive way to convey a tiny gift of any kind; traditionally they included a joke and a paper crown and who can’t use more laughter and bling? Today, crackers may also include a love note, a tube of lip gloss, some cuff links, an engagement ring, or anything you can imagine!

Christingle: Christingles remind me of the traditional orange with cloves pomander commonly seen in the US, but since their adaptation by the Church of England in 1968 they also have spiritual significance. The orange represents the word, the red ribbon ’round it the blood of Christ, the four sticks stuck in the sides with dried fruit or candy for the four “corners” of the earth and the candle, Christ, the light of the word.

Christingle: Christingles remind me of the traditional orange with cloves pomander commonly seen in the US, but since their adaptation by the Church of England in 1968 they also have spiritual significance. The orange represents the word, the red ribbon ’round it the blood of Christ, the four sticks stuck in the sides with dried fruit or candy for the four “corners” of the earth and the candle, Christ, the light of the word.

Boxing Day: A holiday that likely began in the middle ages, it was traditionally a day for employers to present a gift to their employees, they presented a “box” filled with gift or money the day after Christmas. At my house, it’s the day for boxing up the gifts and recycling the wrappings. Best of all – it’s another legal holiday and therefore one more day off from work. What’s not to celebrate?

Please leave a comment about your favorite Christmas tradition and enter to win this tasty bag of Queen Elizabeth I tea!

November 4, 2013

London Confidential Tween Giveaway!

Tyndale House is giving away the ebook for Asking for Trouble, the first book in the London Confidential Series, for the entire month of November! To celebrate, I’m hosting a Brit-tastic give away.

Tyndale House is giving away the ebook for Asking for Trouble, the first book in the London Confidential Series, for the entire month of November! To celebrate, I’m hosting a Brit-tastic give away.

For Tween:

• The complete four-book set of London Confidential Books

• A British flag coin purse PLUS a British penny

• British themed hair bands

For Mom/Grandma/Adult friend who spied this giveaway:

• Butter London Nail Polish in All Hail the Queen

Read all about it!

When her family moves to London, 15-year-old Savvy Smith has to make her way in a new school and in a new country. She just knows the school newspaper is the right place for her, but she doesn’t have the required experience. Can she come up with a way to prove herself and nab the one available position on the newspaper staff at Wexburg Academy? LONDON CONFIDENTIAL: Where British fashion, friendships, and guys collide, and where an all-American girl learns to love life and live out her faith.

Two steps to enter:

1. Please click on the link to the book Asking for Trouble at the Amazon Kindle Store

2. Please leave a comment and email contact information in the comments section, below.

Name will be drawn at the end of November. Cheers!

October 18, 2013

Salmon in Pastry

Salmon in Pastry

Salmon in Pastry

Serves 12

Bait the hook well; this fish will bite.

Much Ado About Nothing, 2, 3

Fish pies were often made into the shape of the fish being eaten such as lobster, crab, salmon or carp and the crust embellished with elaborate pastry scales, fins, gills, and other details.

If you prefer a quicker version, wrap the ingredients in parchment or aluminum foil instead of the pastry dough.

Store bought or homemade pastry or pie dough

3 artichoke bottoms, cooked and quartered

1 salmon fillet, cut into twelve 2- by 3-inch pieces (about 1 1/2 pounds)

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon coarsely milled black pepper

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground nutmeg

1 dozen medium oysters

12 thin asparagus stalks, cut into 1 inch pieces

24 green seedless grapes or gooseberries

1/4 cup coarsely chopped pistachio nuts plus 1/4 cup finely ground pistachio nuts

1 large egg, beaten

3 lemons, cut in wedges

Roll out slightly less than one-half of the dough into a 5- by 13-inch rectangle about 1/4 inch thick and place on a parchment-lined baking sheet.

Place the artichokes in a long line down the center of the crust. Sprinkle the salmon with the salt, pepper, and nutmeg and place over the artichokes. Arrange the oysters, asparagus, green grapes, and coarsely chopped pistachios over the salmon.

Roll out the remaining dough into a 5- by 13-inch rectangle and place on top of the ingredients. Trim the dough into the shape of a fish and pinch the edges to seal. Using the excess dough, add fish details, such as an eye or fin. Using a teaspoon, imprint scale and tail marks on the dough, being careful not to cut through the dough. Brush with the egg and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 375° F. Bake the salmon for 40 minutes, or until golden brown.

Serve with lemon wedges.

Side bar:

This recipe includes artichokes and asparagus, both considered aphrodisiacs in Elizabethan England. Artichokes originated in Sicily and were introduced into England by the Dutch. King Henry VIII’s fondness for artichokes was legendary and he had them grown in his castle gardens. Artichokes, asparagus, and salmon were all expensive delicacies in Shakespeare’s day enjoyed only by the nobility and wealthy.

© Shakespeare’s Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook by Francine Segan.

September 22, 2013

Allington – A Castle for the Ages

Allington Castle, tucked away amongst the lush greenery of Kent, has a long and noble lineage beginning shortly after the Norman Invasion. Its most famous residents, arguably, were the Wyatts.

Allington Castle, tucked away amongst the lush greenery of Kent, has a long and noble lineage beginning shortly after the Norman Invasion. Its most famous residents, arguably, were the Wyatts.

Thomas Wyatt the Elder was renowned as a poet and is looked upon as the father of the English version of the sonnet. He is also well known as the thwarted lover of Anne Boleyn, and nearly lost his life for that affection. His son, Thomas the Younger, lost his life in Wyatt’s rebellion, likely intended to unseat Queen Mary I and, perhaps, place her younger sister, the future Elizabeth I, on the throne. The rebellion failed and lead to his beheading. As further punishment, for treason, Wyatt’s head and limbs were hung from gallows after his death.

Thomas Wyatt the Elder was renowned as a poet and is looked upon as the father of the English version of the sonnet. He is also well known as the thwarted lover of Anne Boleyn, and nearly lost his life for that affection. His son, Thomas the Younger, lost his life in Wyatt’s rebellion, likely intended to unseat Queen Mary I and, perhaps, place her younger sister, the future Elizabeth I, on the throne. The rebellion failed and lead to his beheading. As further punishment, for treason, Wyatt’s head and limbs were hung from gallows after his death.

The family seat of the Wyatts is in Maidstone, near the Medway River, which flows from the North Sea into the County of Kent in the southeast of England. Allington Castle stands on land once held by the Celts, then the Romans and next the Saxons. As early as 1086 there is mention of a manor house at Allington (Elentun) held by Uluric, thought to be the fourth son of Earl Godwin.

Following the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror’s half brother, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, was awarded the estate, but it was soon transferred to William, Earl of Warren. During his tenure as landowner, a Norman castle was built, probably a stone bailey with a moat. When that castle was ordered destroyed by King Henry II in 1174, a manor house was rebuilt that included dovecotes that remain to this day.

In a medieval do-it-yourself frenzy over the next several hundred years, the castle was improved by successive tenants. When Allington passed by marriage to Sir Henry Cobham in 1309, the impressive Solomon’s Tower was added. From then until 1492, Allington stayed by marriage and inheritance in the hands of Penchester descendants.

In 1492, however, the castle was awarded with gratitude by Henry VII to Sir Henry Wyatt; Sir Henry had suffered imprisonment and torture in Scotland under Richard III for Wyatt’s support of the Tudor claimant. Sir Henry served Henry VII for many years as a Privy Councillor, with the king’s finances, and finally as executor of Henry VII’s will. He not only helped manage the royal family’s affairs during Henry VIII’s childhood, he also became an extremely wealthy man in his own right.

In 1492, however, the castle was awarded with gratitude by Henry VII to Sir Henry Wyatt; Sir Henry had suffered imprisonment and torture in Scotland under Richard III for Wyatt’s support of the Tudor claimant. Sir Henry served Henry VII for many years as a Privy Councillor, with the king’s finances, and finally as executor of Henry VII’s will. He not only helped manage the royal family’s affairs during Henry VIII’s childhood, he also became an extremely wealthy man in his own right.

This wealth enabled him to refurbish and expand Allington Castle, adding tall Tudor windows, a large porch, modern fireplaces, an improved kitchen and a courtyard through which England’s oldest Long Gallery ran. One of the towers was also torn down and in its place a Tudor dwelling was built. A magnificent, panelled Royal Room was added to house important guests. The public rooms featured high, stone walls and the private lodgings of the family were beautifully furnished with wood-panelled walls and luxurious carpets, tapestries and furniture.

The Wyatt household included two sons, Thomas and Henry, and at least two daughters, Margaret and Anne/Mary. These residents of Allington Castle were deeply enmeshed in the story of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII. The youngest sister, Meg in my books, was a favorite of Anne Boleyn’s and became one of her chief ladies-in-waiting. Meg traveled with Anne to Calais and later served as Mistress of the Queen’s Wardrobe, sticking by Anne all the way to the platform on which the queen was beheaded. Meg received Anne’s final prayer book in which Anne had inscribed, ““Remember me when you do pray, That hope doth lead from day to day.” Notably, Anne, who often wrote in French, used English here.

The Wyatt household included two sons, Thomas and Henry, and at least two daughters, Margaret and Anne/Mary. These residents of Allington Castle were deeply enmeshed in the story of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII. The youngest sister, Meg in my books, was a favorite of Anne Boleyn’s and became one of her chief ladies-in-waiting. Meg traveled with Anne to Calais and later served as Mistress of the Queen’s Wardrobe, sticking by Anne all the way to the platform on which the queen was beheaded. Meg received Anne’s final prayer book in which Anne had inscribed, ““Remember me when you do pray, That hope doth lead from day to day.” Notably, Anne, who often wrote in French, used English here.

And, so, to modern times. Today, Allington Castle is owned by a generous American, deeply committed to properly stewarding the castle: Sir Robert Worcester, KBE DL, the current Chancellor of University of Kent. It’s interesting to note that Sir Robert is not the first American connection to Allington Castle. In November, 1621 Francis Wyatt, grandson of Thomas the Younger, became the first royal English governor of Virginia.

And, so, to modern times. Today, Allington Castle is owned by a generous American, deeply committed to properly stewarding the castle: Sir Robert Worcester, KBE DL, the current Chancellor of University of Kent. It’s interesting to note that Sir Robert is not the first American connection to Allington Castle. In November, 1621 Francis Wyatt, grandson of Thomas the Younger, became the first royal English governor of Virginia.

I wonder, should we visit Allington today, would we feel whispers of England as it was, is, and ever shall be?

Please enter a comment, below, to be entered into a drawing to win a complete set of Sandra’s Ladies in Waiting Series!

Be sure to check out the other blogs on the blog hop as well!

July 13, 2013

A Masque, A Mask, and a Mystery

Although she bore no child, Queen Elizabeth I midwived a number of bright achievements during her reign which persist to this day; among them a settled religious faith, a healthy national commerce, and a nursing of the fine arts, specifically, the development of theater. London still has one of the finest, if not the premiere, theater districts in the world. But in truth, the English love of drama began much earlier than the 16th century.

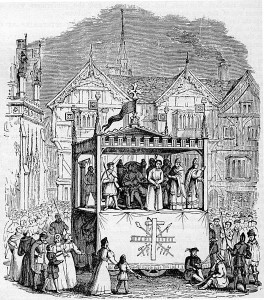

Theater—A Crash Course by Rob Graham states: “During the 12th century, nonliturgical vernacular plays based on biblical stories were performed at festivals, such as Christmas. These were called the Mystery Cycles (the ‘mystery’ was redemption…). Local lads from the crafts guilds and companies performed those ‘passions’ on rough wagons in procession through the streets or on fixed circular stages.”

Early Chester Mystery Play

These plays, staged locally, were mostly enjoyed by the lower classes. The upper class enjoyed theater, too, especially when they put it on themselves. To plays based solely upon Scripture, courtiers added topics such as Greek and Roman gods, comedy, tragedy, and life as they (and their countrymen) knew it. Henry the Eighth was well known as a person who loved to sponsor and act in masques and disguisings. He preferred, of course, to play the valiant knight, or sometimes, what else? the sun itself!

Later in the sixteenth century, plays, playwrights, and performers came into their own and the love of theater spread. The Age of Shakespeare by Frank Kermode, shares that poets and playwrights depended on aristocratic patrons for support. Many of the most highly titled men in Elizabeth’s court sponsored their own troupe, known by the sponsor’s name. For example, The Earl of Leicester’s Men were sponsored by the queen’s favorite, and later, The Queen’s Men were sponsored by Her Majesty herself.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

When the queen finally sponsored her own troupe, the cloudy reputation of players and playwrights finally lifted. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men were sponsored by Baron Hunsdon, Queen Elizabeth’s cousin by Mary Boleyn. William Shakespeare wrote many of his plays for the troupe sponsored by The Lord Chamberlain, including Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth. Others were writing and performing too. Kermode tells us that, “between 1558 and 1642 there were about three thousand (plays), of which six hundred and fifty have survived.”Shakespeare was not only a playwright, he sometimes acted in secondary roles and later, when partnerships began to sponsor performances for financial gains, he was an investor. He was among those who received a grant of arms and a great deal of money for his talents. Some of his better known colleagues and competition weren’t so lucky. Christopher Marlow was stabbed to death at 29; Ben Johnson was often in jail and ended up with a branded thumb.

Plays were also used for political purposes, even against the queen who allowed them to flourish. Historian Simon Schama tells us that the traitorous Earl of Essex sponsored a special production of “Richard II – which deals with the murder of an incompetent king … to gee up his supporters against Elizabeth…” Elizabeth herself approved a play written by Sir Henry Lee, The Hermit’s Tale, which celebrated a woman who chose her father’s dukedom and duty over her own love. She used the tale, masterfully, to signal to her courtiers and her people that she would always put her true husband, England, first.

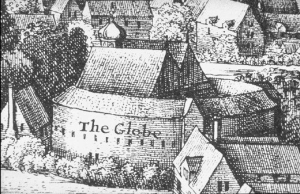

The Old Globe theater, print created in 1642 by Hollar.

Then, and now, drama allows us to explore our lives, our problems, our hopes and dreams, and our loves and losses. In fact, we, too, are players, for as William Shakespeare wrote, “All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and entrances and one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.”

Please leave a comment, below, and you’ll be entered to win one of the fabulous Elizabeth I necklaces, seen here!