Sandra Byrd's Blog, page 20

May 31, 2013

Did Elizabeth I Really Hate Other Women?

There has long been an “urban rumor” that Elizabeth Tudor hated other women. It’s true that she was a female monarch in a time which greatly preferred sovereign men. {Note the extent to which her father, Henry VIII, extended himself to get a male heir, as well as the contents of John Knox’s much-circulated pamphlet, “The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women,” which railed against sitting queens and regents of the era.} Elizabeth didn’t forestall imprisoning women for long periods of time, such as her Grey cousins and Mary Queen of Scots, when she felt they threatened her throne, which admittedly may have seemed unfeminine and harsh.

There has long been an “urban rumor” that Elizabeth Tudor hated other women. It’s true that she was a female monarch in a time which greatly preferred sovereign men. {Note the extent to which her father, Henry VIII, extended himself to get a male heir, as well as the contents of John Knox’s much-circulated pamphlet, “The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women,” which railed against sitting queens and regents of the era.} Elizabeth didn’t forestall imprisoning women for long periods of time, such as her Grey cousins and Mary Queen of Scots, when she felt they threatened her throne, which admittedly may have seemed unfeminine and harsh.

Because of her ruling position, Queen Elizabeth was never really able to be an equal companion with anyone. William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, who dedicated his life to her service, once said the queen was “more than a man and, in truth, something less than a woman.” And yet, perhaps that was a man’s perspective, or one man’s perspective of a woman with power. Elizabeth knew how to dress like a woman, flirt like a woman, fall in love like a woman, and there were certainly women who were in every sense her lifelong friends.

Katherine Carey, Lady Knollys

Take for example, Katherine Carey Knollys, daughter of Mary Boleyn. Shortly after Elizabeth became queen, she installed this cousin as Chief Lady of the Bedchamber and kept her close at hand, perhaps to the detriment of Knollys family, till the day Lady Knollys died.Katherine “Kat” Ashley and Blanche Parry stayed with Elizabeth from her childhood until each woman died. Because Elizabeth was deprived of her own mother as a young girl, Ashley and Parry became surrogate mothers to her. Ashley spoke bluntly to Elizabeth when no one else dared, and Parry continued on in Elizabeth’s household in positions of honor and affection long past her abilities warranted them.

Anne Russell Dudley married Lord Ambrose Dudley, the brother of Elizabeth’s longtime love, Robert, and became the Countess of Warwick. But even before then, Anne served Elizabeth as a maid of honor. They became great friends, and Anne stayed by her mistress’ side until Elizabeth died in 1603. Catherine Carey, the Countess of Nottingham, was the eldest daughter of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, Mary Boleyn’s son and therefore a cousin to Elizabeth; she died shortly before Elizabeth did, and it was said that her death was the loss Elizabeth was unable to bear, eventually leading to the queen’s lack of will to live.

And then in 1566, Elin von Snakenborg came from Sweden to England. The queen intervened, unusually, with another monarch in order to allow Elin to remain in England. Elizabeth, as famous for counting her pennies as her grandfather Henry VII, atypically awarded rooms, a servant, and a horse to Elin (later Helena) within months of her arrival. Throughout her service, Helena was known as someone who couldn’t be bribed. She became a great friend of the queen and the highest ranking woman in England after Elizabeth, though that friendship was tested perhaps more than many of the queen’s confidantes.

(Elin) Helena von Snakenborg

But what about all those women Elizabeth is supposed to have precluded from getting married, insisting that they remain virgins like herself? There is no doubt that from time to time Elizabeth expressed, sometimes forcefully, her preference that her ladies not marry. Anne Somerset, in her biography, Elizabeth I, states, “The Queen’s opposition to her ladies marrying stemmed from more than mere jealousy that they should attain contentment of a sort that she would never know. Although she occasionally lamented her spinsterhood, simultaneously she entertained an altogether contradictory conviction that matrimony was an undesirable condition for women, a view not altogether surprising when one recalls that her father had executed her mother and stepmother, and the marriage of her sister had been a fiasco. It may well have been her early experience that instilled in her that instinctive aversion to the married state.”

While the Queen clearly enjoyed her power, she perhaps also keenly felt the loss of the kind of social and emotional intimacy that all people, and especially women, desire in a family. And yet she had no mother or father, no siblings, no husband, no children and her (Tudor) cousins all had claim to her throne. Historian and author Antonia Fraser said, “Her [Elizabeth’s] household resembled a large family, often on the move between residences, and as a family it had its feuds when factions formed around strong personalities. It was not out of malice that Elizabeth opposed her maids of honors’ plans to marry, but because marriages broke up her own family circle.”

Thought to be Catherine Carey Howard, Countess of Nottingham

The queen did, sometimes, help them to marry and marry well. Somerset says, “She (Elizabeth) could point out in the course of her reign no less than 13 of her maids of honor contracted prestigious marriages within the peerage, and this might seem to justify her claim that it was only unsuitable matches of which she disapproved.” The trick, of course, is that one never knew if the queen would approve or not. The consequences of the latter could be severe and long lasting.In the whole, though, it certainly cannot be proved that Elizabeth Tudor hated women; in fact, the handful of long term, devoted friendships we know about prove otherwise. She gifted those women with rents, properties, perquisites, trust, affection, gowns and jewels, and emotional intimacy. Oxford University historian Susan Doran states in her book, Queen Elizabeth I, “It should also not be forgotten how loyal and gracious she could be to her intimates and that the turnover of her household was very low. The majority of women served until death or severe illness intervened.”

Please leave a comment below for a chance to win this lovely, antiqued Elizabeth necklace as well as a copy of the book, Roses Have Thorns: A Novel of Elizabeth I:

April 1, 2013

Books and Blooms Giveaway!

To celebrate the release of my third Ladies in Waiting novel, and to say thank you to my prized readers, I’m offering everyone the chance to win one of three fabulous “Rose” themed prizes in my Books and Blooms Giveaway. First prize, an e-book or print book of Roses Have Thorns: A Novel of Elizabeth I. Second Prize, a handcrafted Elizabeth I necklace from Belle on a Budget. These two prizes are open internationally as well as North America. Third prize, a $25 gift certificate to Heirloom Roses, available to US readers only.

This giveaway is all about sharing, so the more you spread the word, the more chances you have at winning a prize! Please share via Facebook, Twitter, email, and/or your blog. If you are on Pinterest you can also re-pin the contest button which can be found here (link to come). Be sure to read the Rafflecopter form below for complete rules and to enter.

Books and Blooms Giveaway is open for entries April 9 – May 31, 2013!

February 12, 2013

Locked Lips or Love Locks in Paris?

When I first told a friend that I was writing a post on the Love Locks of Paris, she teasingly asked if they related to chastity locks: those early medieval belts by which a Crusaders was supposed to reassure himself that his girl would remain true. Not quite!

When I first told a friend that I was writing a post on the Love Locks of Paris, she teasingly asked if they related to chastity locks: those early medieval belts by which a Crusaders was supposed to reassure himself that his girl would remain true. Not quite!

Wander along the lovely Seine in Paris; stop at any number of bridges to enjoy a crepe, and the view. Many place you’ll notice the webbed metal railings alongside the stonemasonry and clasped to them are hundreds, often thousands, of padlocks. Sometimes they’re thinly scattered, with ribbons aflutter, sometimes they’re as thick as hoarding like bees on a honeycomb.

Love locks on the bridge Pont des Arts across river Seine in Paris, France @istock photos.

Although locks with lovers names have a history throughout European bridges dating back perhaps a hundred years, in Paris, they only began to show up in 2000. Most often they have “his” and “her” names on either side of the lock and then are hooked, permanently they hope, to the side of a bridge in the City of Light and Love. As long as the lock, lasts, so goes the hope, so shall the love.

According to an article in The New York Times, “The Paris town hall expressed concern: what about the architectural integrity of the Parisian landscape? One night about two years ago, someone cut through the wires and removed all the locks on one of the bridges. But in just a few months, locks of all sizes and colors reappeared, more conspicuous than ever.”

@istock photos

Alas, keeping love alive requires more than simply firmly clasping a lock to keep your lover true, whether it be a chastity lock or hooking a Shlage or Kwikset through the rails of a Parisian bridge. As French philosopher Marcel Proust, “We only love what we do not wholly possess.” Isn’t that the very opposite of a lockdown? Much better to lock lips, and perhaps put a ring on it, instead. What do you say – delightful ode to eternal love or deadly-locked display? What makes love last for you? Leave a reply to be entered into a drawing for the DVD French Kiss!

January 8, 2013

Teamwork

“Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.” Helen Keller

On a visit to London several years ago we rented a flat with a lovely view of the Thames. Each morning, as the sun rose, low slung skiffs would silently glide up the placid brown river, the oarsmen keeping time with one another in a delicate dance as their boat bellies skimmed the water.

I wasn’t surprised to learn that modern rowing competitions originated in London, among the city’s watermen. These men ran what we would call water taxis, ferrying passengers and goods from one shore to the next in an era when there were fewer bridges. The first race was sponsored in 1715 and over time the prize purses grew quite large, sometimes subsidized by owners of the grand houses which lined the river’s shores; they often held viewing parties.

The Boat Race at Cambridge

In 1829 the first Boat Race between Cambridge University and Oxford University took place and it has been held annually ever since. Great Britain took the lion’s share of the rowing medals in the 2012 Olympics. Its long oaring tradition certainly helped. Even the Duchess of Cambridge rows; she practiced as coxswain for a charity sponsored event. Something tells me she already knows quite a bit about teamwork.

In team competition it’s often the crew that has learned to best work together which brings home the cup. Each individual member has to bring his or her A game, to be sure, but then once in the boat, set aside individualism to be in sync with, no better nor less than, the others, all under the direction of the coxswain, who directs the crew.

I asked myself: To which team would you like to bring your A game this year? What cause would you like to put your muscle toward? Whom can you join, and help? “Two are better than one, because they have a good return for their labor.” Ecclesiastes 4:9

How about you?

December 17, 2012

“Pears” in Broth

“Pears” in Broth

“Pears” in Broth

Serves 6

This impressive dish was designed with a feast in mind. The meatballs, with their sage leaf stems resemble tiny speckled pears.

They are also wonderful served alone, without the broth.

8 ounces ground veal or pork

1/4 cup dried whole wheat bread crumbs

1 large egg

1 tablespoon finely chopped thyme

2 tablespoons finely chopped parsley

1/2 teaspoon salt

12 small green seedless grapes

12 sage leaves, with stems

1 1/2 quarts chicken broth, warm

Pinch of saffron threads

Combine the veal, bread crumbs, egg, thyme, parsley, and salt in a bowl. Divide the mixture into 12 equal portions. Wrap each portion of meat around a grape and form a pear shape. Refrigerate until ready to cook.

Preheat the broiler. Place the pears upright on a well-greased pan, and broil 4 to 5 inches from the flame for 4 minutes, or until done. Using a toothpick, gently imbed a sage leaf into the top of each pear.

Carefully place 2 pears in each serving bowl and ladle the broth around the pears.

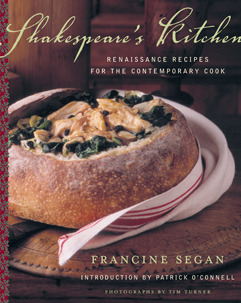

© Shakespeare’s Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook by Francine Segan.

December 10, 2012

Tudor Christmas Traditions

Please enjoy this guest post by Wendy Pyatt, then enter the drawing, below!

Please enjoy this guest post by Wendy Pyatt, then enter the drawing, below!

Tudor Christmas Traditions

Christmas through New Years was the greatest festival period celebrated by the Tudors. Advent was a time of fasting; Christmas Eve was particularly strictly kept with no meat, cheese or eggs. Celebrations began on Christmas Day when the genealogy of Christ was sung while everyone held lighted tapers. The monarch was required to attend church and would be expected to wear new clothes. He or she would progress from the Privy Chamber to the Chapel Royal dressed in coronation robes of purple and/or scarlet complete with crown.

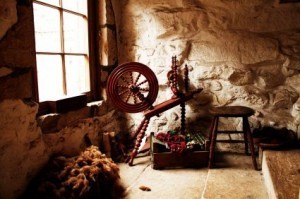

The whole 12 days of Christmas was celebrated (25th December – 6th January). All work stopped except looking after animals; spinning was even banned as this was a common occupation for women and flowers were placed around the spinning wheels. People would visit friends instead of working and it was seen as very much a community celebration. Work re-started on Plough Monday, the first Monday after 12th night.

In Tudor Times the most sumptuous feasts were held on 25th Dec, 1st Jan and 6th Jan. In 1532/33, the preparation for the 12th night feast at Greenwich palace required the building of a temporary boiling and working house. Up to 24 courses would be served, much more than was needed for the guests, but it was a status symbol. Leftover food was always used to feed the poor.

Tudor Christmas had a definite purpose and was always a 2 week period of concerted power, politics, and networking as the monarch would certainly be surrounded by all courtiers, nobility and other important people. Because society was very strictly organised, these celebrations acted as a pressure release, a time when everything was turned on its head, the world turned inside out and upside down. Certain sections of society were even allowed an unusual degree of freedom. For example, there was a Lord of Misrule. He was like a mock king and supervised entertainments or rather unruly events involving drinking, revelry, role reversal and general chaos. The inspiration for this Lord of Misrule was the earlier 11th century tradition of The Feast of Fools.

Tudor Christmas had a definite purpose and was always a 2 week period of concerted power, politics, and networking as the monarch would certainly be surrounded by all courtiers, nobility and other important people. Because society was very strictly organised, these celebrations acted as a pressure release, a time when everything was turned on its head, the world turned inside out and upside down. Certain sections of society were even allowed an unusual degree of freedom. For example, there was a Lord of Misrule. He was like a mock king and supervised entertainments or rather unruly events involving drinking, revelry, role reversal and general chaos. The inspiration for this Lord of Misrule was the earlier 11th century tradition of The Feast of Fools.

Another favorite Tudor Christmas tradition was the performing of plays. There are records from the early 16th century that both Oxford and Cambridge colleges employed travelling players in their Christmas entertainments. There are also records of a play being performed for Cardinal Wolsey at Grays Inn during Christmas 1526. Coventry mystery plays, which the Coventry carol was written for, tell the story of Herod’s murder of the innocents. Mystery plays are still performed in Coventry today.

The Tudors also possibly practiced the Viking custom of burning a Yule Log. The Log would be decorated on Christmas Eve for the 12 days of Christmas and then burned. It was considered lucky to keep some remains to help light the following year’s log.

All sports on Christmas day were banned by Henry VIII in 1541 (except archery of course). In theory gambling, tennis, bowls and other games were forbidden to all but the very wealthy except. Jousting was also a popular aristocratic sport during the Christmas period.

An interesting tidbit is that in 1551, Edward VI passed a law commanding everyone to walk to church on Christmas Day; it’s still on the books today.

Drawn with permission from a post originally published at www.localhistories.org

Please enter a comment, below, to be entered for the prize of a signed copy of the novel To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn, and a set of drink coasters of the six wives of Henry VIII, put out by the National Portrait Gallery.

Please enter a comment, below, to be entered for the prize of a signed copy of the novel To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn, and a set of drink coasters of the six wives of Henry VIII, put out by the National Portrait Gallery.

November 5, 2012

A Seer, A Prophet or A Witch?

“And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams…” Acts 2:17 King James Version

Six women in the Bible are expressly stated as possessing the title of prophetess: Miriam, Deborah, Huldah, Noahdiah and Isaiah’s wife. Philip is mentioned in Acts as having four daughters who prophesied which brings the number of known prophetesses to ten. There is no reason to believe that there weren’t thousands more, undocumented throughout history, then and now. According to religious tradition, women have often been powerful seers and that is why I’ve included them in my current novel: The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr.

Hundreds of years before the renaissance, which would bring about improved education for women, Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) wrote medicinal texts and composed music. She also oversaw the illumination of many manuscripts and wrote lengthy theological treatises. But what she is best known for, and was beatified for, were her visions.

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard said that she first saw “The Shade of the Living Light” at the age of three, and by the age of five she began to understand that she was experiencing visions. [1] Although she was understandably reluctant to share her visions she continued to receive them, understanding them to be from God and, in her forties, was instructed by Him to write them down. She said, ” I set my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I sensed, as I mentioned before, the deep profundity of scriptural exposition… I spoke and wrote these things not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from Heaven saying to me, ‘Cry out therefore, and write thus!” [2]

Spiritual gifting is not given for the edification of the person receiving it, but for the church at large. Hildegard wrote three volumes of her mystical visions, and then exegeted them biblically herself. Her theology was not, as one might expect, shunned by the church establishment of the time, but instead Pope Eugenius III gave her work his approval and she was published in Paris in 1513.

Several centuries later, Julian of Norwich continued Hildegard’s tradition as a seer, a mystic, and a writer. In her early thirties, Julian had a series of visions which she claimed came from Jesus Christ. In them, she felt His deep love and had a desire to transmit that He desired to be known as a God of joy and compassion and not duty and judgment. Her book, Revelations of Divine Love, is said to be the first book written in the English language by a woman. [3] She was well known as a mystic and a spiritual director by both men and women. The message of love and joy that she delivered is still celebrated today; she has feast days in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran traditions.

Julian of Norwich

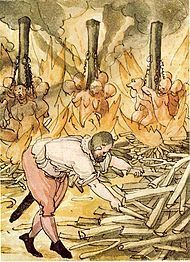

It had been for good cause that Hildegard and Julian kept their visions to themselves for a time. Visions were not widely accepted by society as a whole, and women in particular were often accused of witchcraft. This risk was perhaps an even stronger danger in sixteenth and seventeenth century England when “witch hunts” were common. While there is no doubt that there was a real and legitimate practice of witchcraft occurring in some places, the fear of it whipped up suspicion where no actual witchcraft was found. Henry the VIII, after imprisoning Anne Boleyn, proclaimed to his illegitimate son, among others, that they were all lucky to have escaped Anne’s witchcraft. The evidence? So obviously bewitching him away from his “good” judgment.

In that century, the smallest sign, imagined or not, could be used to indict a “witch”. A gift handling herbs? Witchcraft. An unrestrained tongue? Witchcraft. Floating rather than sinking when placed in a body of water when accused of witchcraft and therefore tested? Guilty for sure. Women with “suspicious” spiritual gifts, including dreams and visions, had to be particularly careful. And yet they, like Hildegard and Julian before them, had been given just such a gift to share with others. And share they must.

One women in the court of Queen Kateryn Parr is strongly believed to have had a gift of prophecy. Her name was Anne Calthorpe, the Countess of Sussex. One source possibly hinting at such a gift can be found at Kathy Emerson’s terrific webpage of Tudor women: [4] Emerson says that Calthorpe, “was at court when Katherine Parr was queen and shared her evangelical beliefs. Along with other ladies at court, she was implicated in the heresy of Anne Askew. In 1549 she was examined by a commission “for errors in scripture” and that “the Privy Council imprisoned two men, Hartlepoole and Clarke, for “lewd prophesies and other slanderous matters” touching the king and the council. Hartlepoole’s wife and the countess of Sussex were jailed as “a lesson to beware of sorcery.”

Execution of Alleged Witches, 1587

According to religious tradition women have often had very active prophetic gifts; we are mystical, engaging, and intuitive. I admire our sisters throughout history who actively, risk-takingly, used their intellectual and spiritual gifts with whatever power they had at hand.

[1] Bennett, Judith M. and Hollister, Warren C. Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001), 317.

[2] Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, trans. by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop with an Introduction by Barbara J. Newman, and Preface by Caroline Walker Bynum (New York: Paulist Press, 1990) 60–61.

[3] http://www.julianofnorwich.org/vision...

[4] http://www.kateemersonhistoricals.com...

October 27, 2012

Meat Pies with Cointreau Marmalade

Individual Meat Pies with Cointreau Marmalade

Individual Meat Pies with Cointreau Marmalade

Serves 8

Elizabethan street vendors sold little minced pies like these as well as oyster pies, apples, and nuts to theatergoers. The audience ate during the entire play and tossed cores, shells, and scraps onto the theater floor.

These tiny meat pies delicately flavored with orange liqueur are just as perfect now, as then, for picnics or pre-theater nibbling.

8 ounces ground lamb, beef or veal

1/4 teaspoon freshly milled black pepper

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/4 teaspoon freshly ground nutmeg

1/2 teaspoon ground mace

3 dried plums, finely chopped

1/2 cup currants

1/4 cup freshly squeezed orange juice (or any orange liqueur such as Cointreau)

pie dough, either homemade or store bought

1/4 cup Cointreau

1/2 cup thick-cut orange or 3 fruit marmalade

Combine the meat, pepper, salt, nutmeg, mace, dried plums, currants and orange juice in a bowl and refrigerate for at least 6 hours, or overnight. Remove the meat from the refrigerator 1 hour before baking.

Preheat the oven to 450° F. Roll out the Renaissance Dough 1/16 inch thick on a floured work surface. Cut twenty-four 3-inch circles from the dough. Press the dough circles into mini-muffin pans. Loosely fill each muffin cup with the meat mixture (about 1 tablespoon per pie) and bake for 15 minutes.

Bring the Cointreau to a boil in a small saucepan, stir in the marmalade, and cook until the marmalade is warm.

Spoon some of the marmalade mixture on top of each minced pie and serve.

© Shakespeare’s Kitchen: Renaissance Recipes for the Contemporary Cook by Francine Segan.

September 19, 2012

Author Blog Tag!

I’ve been tagged! A group of generous and collegial authors has put together The Next Big Thing, in which authors answer 10 questions they hope will help one of their books become just that. Whether or not my book is a big thing, a little thing, or no-thing at all, I’m very grateful to Regency era author Debra Brown who also owns the English Historical Fiction Authors site and Nancy Bilyeau for passing the goodness along. And without further ado … here are my 10 questions and answers!

Ten Interview Questions for the Next Big Thing:

1. What is your working title of your book?

Roses Have Thorns: A Novel of Elizabeth I

2. Where did the idea for the book come from?

When I set out to write the Ladies in Waiting Series, I already knew the three queens I liked best, and wanted to write about: Anne Boleyn, Kateryn Parr, and Elizabeth. I just didn’t know from which Lady’s point of view I would tell Elizabeth’s story. So when I stumbled upon Elin von Snakenborg, later Helena, Marchioness of Northampton, I knew I’d found my girl.

3. What genre does your book fall under?

Historical Fiction, with a little more romance than the others in the series, perhaps. I had fun writing this kind of romance because it’s different than the other two.

4. Which actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition?

Helena von Snakenborg: Alicia Vikander

William Parr: John Forsythe, were he but alive

Thomas Gorges: David Garrett

Elizabeth: Who but Cate Blanchett?

Dudley: I’ve always loved Joseph Fiennes in that role

Sofia: Emily Blunt

Helena von Snakenborg

5. What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

In a court that is surrounded by enemies who plot the queen’s downfall, Helena is forced to choose between her unyielding monarch and the husband she’s not sure she can trust—a choice that will provoke catastrophic consequences.

6. Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

My book will be published in April, 2013 by Howard Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

7. How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

About a year, all told.

8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

Any of the many Tudor historical fiction books.

9. Who or what inspired you to write this book?

I admit to being an unapologetic Elizabethan despite her imperfections and I wanted to tell the Queen’s story from a fresh point of view. Discovering Helena Northampton allowed me to do that. I loved getting to known Helena, and to rediscover Elizabeth again through her eyes.

10. What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

Mary, Queen of Scots

The story builds to and just beyond the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots, another fascinating Queen, and Elizabeth’s cousin.

Please visit these fine authors I’m tagging to learn if their next book might be the Next Big Thing!

September 5, 2012

Mother Mourning: Childbed Fever in Tudor Times

Black death. The Great Pestilence. Plague. Sweating Sickness. The very words themselves cause us to shudder, and they certainly caused those in centuries past to quake because they and their loved ones were often afflicted by those diseases. But when we survey the physical ailments that afflicted sixteenth century women there is one death that caused the deepest fear among women: Childbed Fever, also known as Puerperal Fever and later called The Doctors’ Plague.

Medieval and Tudor medicine centered around both astrology and the common belief that all health and illness was contained in balance or imbalance of the four “humours” of bodily fluids: blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. Therefore, the letting of blood or sniffing of urine were common manners to address or diagnose illness. Although it seems ludicrous to us today, this understanding of medicine had reigned supreme for nearly 2000 years, coming down from Greek and Roman philosophical systems. It’s been said that perhaps only 10-15% of those living in the Tudor era made it past their fortieth birthday. Common causes of illness leading to death? Lack of hygiene and sanitation.

Elizabeth of York

Decades before the germ theory was validated in the late nineteenth century, Hungarian physician Ignac Semmelweis noticed that women who gave birth at home had a lower incidence of childbed fever than those who gave birth in hospitals. Statistics showed that, “Between 1831 and 1843 only 10 mothers per 10,000 died of puerperal fever when delivered at home … while 600 per 10,000 died on the wards of the city’s General Lying In Hospital.”[1] Higher born women, those with access to expensive doctors, suffered from childbed fever more frequently than those attended by midwives who saw fewer patients and not usually one after another.

In 1795 Dr. Alexander Gordon wrote, “It is a disagreeable declaration for me to mention, that I myself was the means of carrying the infection to a great number of women.”[2] Although they did not realize it at the time, it was, in fact, the sixteenth century doctors themselves who were transmitting death and disease to delivering mothers because the doctors did not disinfect their hands or tools in-between patients.

Queen Jane Seymour, courtesy of wikimedia

Because illnesses are often transmitted via germs doctors (and busy midwives) could infect the young mothers one after another, most often with what is now known as staph or strep infection in the uterine lining. Semmelweis discovered that using an antiseptic wash before assisting in the delivery of the mother cut the incidence of Childbed Fever by at least 90% and perhaps as much as 99%, but his findings were soundly rejected. Infected women had no antibiotics to stop the onslaught of familiar symptoms once they began: fever, chills, flu like symptoms, terrible headache, foul discharge, distended abdomen, and occasionally, loss of sanity just before death.

This kind of death was not only no respecter of persons, as mentioned above, it perhaps struck the highborn more frequently than the low born. In fact, fear of childbed fever is often mentioned when discussing Elizabeth I’s reluctance to marry and bear children. In the Tudor era Elizabeth of York, the mother of Henry VIII, died of Childbed Fever as did two of Henry’s wives: Queen Jane Seymour and Queen Kateryn Parr. Parr’s deathbed scene is perhaps one of the most chilling death accounts of the century, beheadings included.

Tomb of Queen Kateryn Parr, courtesy of Meg McGath

Although Semmelweis was outcast from the community of physicians for his implication that they themselves were the transmitters of disease, ultimately, science and modern medicine prevailed. Today, in the developed world very few of the newly delivered die due to Puerperal Fever. Moms no longer need fear that the very act of bringing forth life will ultimately cause their own deaths and therefore can happily bond with their babies, instead.

[1] The Doctors’ Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis, Sherwin B Nuland, WW Norton, 2004

[2] Oliver Wendell Homes: The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever