Adriano Bulla's Blog, page 7

March 27, 2015

Marc Nash

Everything is MetaphoricalDo you remember how Edgar Allan Poe stated that short stories should 'be able to be read in one sitting'? Well, I am honoured to present an author I believe is the contemporary master of flash fiction: Marc Nash, a London-based fiction writer who mixes an incredible, often quirky, imagination, which fetches ideas from the most unexpected corners of Human knowledge and experience, with a peculiar and idiosyncratic, unique sense of irony t...

Published on March 27, 2015 12:17

March 26, 2015

The Big Wide Calm

A Journey through Human Nature to the Sound of Music

The Big Wide Calm

by novelist Rich Marcello is an intriguing, innovative and well written coming of age novel, part of a trilogy including The Color of Home and the forthcoming The Beauty of the Fall exploring three different aspects of love. Published in 2013 by Langdon Street Press, The Color of Home a story of love, of loss, of digging deep down to the bottom of things until maybe, just maybe, Nick...

A Journey through Human Nature to the Sound of Music

The Big Wide Calm

by novelist Rich Marcello is an intriguing, innovative and well written coming of age novel, part of a trilogy including The Color of Home and the forthcoming The Beauty of the Fall exploring three different aspects of love. Published in 2013 by Langdon Street Press, The Color of Home a story of love, of loss, of digging deep down to the bottom of things until maybe, just maybe, Nick...

Published on March 26, 2015 16:04

March 12, 2015

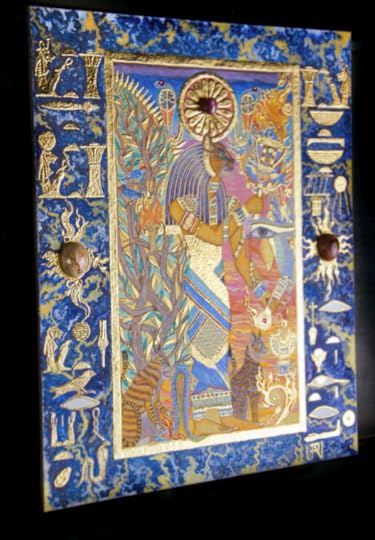

Living In A World of Symbols

An Intimate Interview with Iconographer & PoetPtahmassu Nofra-Uaa

We live in an Aristotelian world; a descriptive mindset where essence is subordinate to parameters by which we describe it, a world that denies its own soul and metaphysical nature and pretends to find its identity in a labyrinth of systems which insist on presenting us with the walls that constrain and limit our senses as a guide towards an exit, yet only promote the part over the whole. Plato is loved by most, revered by...

We live in an Aristotelian world; a descriptive mindset where essence is subordinate to parameters by which we describe it, a world that denies its own soul and metaphysical nature and pretends to find its identity in a labyrinth of systems which insist on presenting us with the walls that constrain and limit our senses as a guide towards an exit, yet only promote the part over the whole. Plato is loved by most, revered by...

Published on March 12, 2015 13:53

February 23, 2015

Amy Aimee's Good Pussy Bad Pussy

Who Knows What Is Good or Bad?A look at the themes in “Good Pussy Bad Pussy – Rachel’s Tale” by A. Aimee

Who Knows What Is Good or Bad?A look at the themes in “Good Pussy Bad Pussy – Rachel’s Tale” by A. AimeeDo you know the story of the Chinese farmer whose horse runs away? It goes like this: When the farmer’s neighbour came to console him the farmer said, ‘Who knows what’s good or bad?’ When his horse returned the next day with a herd of horses following her, the foolish neighbour came to congratulate him on his good fortune. ‘Who knows what’s good or bad?’...

Published on February 23, 2015 13:18

January 17, 2015

Thoughtful Oxymoron

I Can't Paint, Aarti Shinde, 2014, View painting here

I Can't Paint, Aarti Shinde, 2014, View painting hereI do like my oxymora. Following from my post on poetics and ambiguity, which focused on a simple way of provoking thoughts in the reader, syntactic inversion, I would now like to look at another, powerful tool in the hands of the writer, known by many, yet not as widely used as one would expect. Like all tropes, and I use the word in its primary meaning, of literary device, it is not easy, or possible, to decide where the ethos of...

Published on January 17, 2015 09:06

January 12, 2015

Fragmentary Solipsism

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman, Oil on Canvas, 1909

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman, Oil on Canvas, 1909Fragmentary Solipsism

I have recently read a post arguing that Post-Modernism has alienated readers. Possibly so, and I would wish to point out some of the reasons why. When Alan Bullen describes the Modernist experience as a 'double image', where the divide between the Victorian world and the one left in tatters after the First World War, he was not speaking simply academically, but of a deep malaise that affected Humankind as a whole. True, the Modernists explored fragmentation and its psychological and emotional consequences in their Literature, yet took it as a starting point in the development of the most influential literary movement in Human History. The coming together of three colossal figures such as Joyce, Woolf and Eliot on the literary scene made 1921 the annus mirabilis of Literature, just at the time when Einstein was telling the world that all is relative. Woolf in particular seems to have understood that the 'moments of being' are relative, that consciousness dilates and contracts in time and space, an experience anyone who reads her work will feel quite clearly. Although I do understand how difficult it is to measure up to such gigantic advancements in writing, I also believe that the Modernists did not see themselves as the end of the line, but a new beginning. What they did was embrace new philosophies and new expressive techniques to provide a platform for future Literature. Fragmentation was seen by the Modernists as a condition to explore and conquer, in fact, if we look at how Septimus and Clarissa bridge, even if in the act of dying, separation, at how Tiresias 'sees' when the Sun sets and two worlds come together, and compare it to what Post-Modernism has made of it, we can see that the latter has made of a painful condition a value: not exactly what the Modernists had in mind.

In its unconditional surrender to fragmentation, Post-Modernism has thrown away the baby with the bath water, forgetting that 'these fragments' had been 'shored against [our] ruin,' and had not been presented as reality itself but an experience of reality which we were set to fight against, thus abandoning the battlefield and running away with the weaponry left therewith.

Post-Modernism has fallen into the temptation of exploring and developing the technical consequences of Modernism, but has betrayed its spirit: the way the message is conveyed has become paramount at the expense of the message itself. This has, in my opinion, created a rift between what the reader enjoys and what the writer-now-turned-technician offers: whilst the former is in pursuit of meaning, the latter starts with the assumption that no truth can be arrived to, that the breakdown in our perception of Human experience is ultimate and unbridgeable. The writer appears, to the Post-Modernist reader, as primarily preoccupied with a form of Representationalism which dictates that narrative cannot and should not have unity: the fight against fragmentation has become the search for and justification of it.

The allure of Post-Modernism for the writer is the infinite possibilities that narrative fragmentation implies and engenders: we may have overthrown the tyranny of the omniscient narrator, but have not replaced him/her with a structured republic, yet with a long and self-absorbed discourse on how there can be no authority. Solipsism, possibly the only accountable reality of our condition, reigns supreme in the Post-Modern literary world. Yet, and here one needs a leap of faith, Free Will implies the ability to change our condition, not just taking stock of it. And it is Free Will which Post-Modernism sacrifices on the altar of Representationalism.

The irony is that Representationalism a rather antiquated Aesthetic Theory, and whilst the visual Arts have progressed, Post-Modernism seems incapable of accepting its Representationalist bias: if the focus remains on ways of portraying experience, rather than ways of shaping it, the very argument thus engendered is mote. No better evidence is offered than by the great McEwan himself, who follows the argument of Post-Modernism to its very conclusion, thus, while 'The beginning is simple to mark', the separation of reality into fragments, each running on a parallel yet irreconcilable line, end, like the branches Jed clearly sees in one of the three appendixes of Enduring Love , standing naked against the winter sun in all its loneliness. I do understand why some readers felt frustrated by the use of appendixes in the novel, yet I believe McEwan is making a very important statement: if we assume that all Literature is about is representing fragmentation from different points of view, we forsake the very meaningfulness of narrative and surrender our roles as Artists to assume one of 'appendix writers'. We have been writing footnotes to a theory for far too long. The very consciousness Woolf so beautifully explores has become a dependent factor in an equation dominated by the form of experience and our limitations in reporting it, not experience itself.

What Post-Modernism, I believe, has done is put artistry on a pedestal, and forgotten the metaphysical, whilst I am of the opinion that we should put artistry to the service of Art, and re-establish a link between our physical and metaphysical self. We may wish to keep digging as many ditches as we can think of around our shattered selves, but the only reality we will be reinforcing is that there are infinite possibilities for digging, or decide, and here's the leap of faith I believe we need, that Literature is more than a representation of our condition, it is a way of defining ourselves, of, if I am allowed to use these words, even inventing ourselves.

Published on January 12, 2015 09:06

December 20, 2014

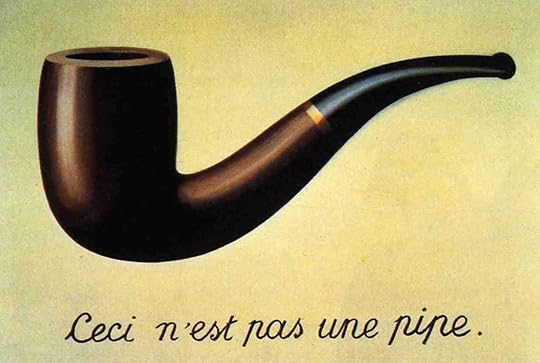

Saussure's Pipe

René Magritte Ceci n'est pas une pipe, oil on canvas, 1928-29Saussure's Pipe

René Magritte Ceci n'est pas une pipe, oil on canvas, 1928-29Saussure's PipeI do understand that some of my posts may appear to be 'against' some ideas, for example my post on

Published on December 20, 2014 12:09

December 19, 2014

Words for Water

Word for Water

This is a project I have been working on for some time: I was contacted by a very worthy Charity, Water.org , whose cause is very, very worthy, as they provide clean water to people who, in a world that we call 'civilised', are still left without, and they asked me to help. So, as there's strength in unity, I have thought of producing an anthology, Words for Water, together with other writers, and give all the copyrights to the Charity.So far, many writers have joined in, but we'd like more, so, if you feel you want to contribute, please get in touch (I will write how to at the bottom of this post).What we are looking for is poems and short stories, which do not have to be about the theme of water, but can, to go in the anthology. There's no word limit (though a full novel would not fit in) nor a word minimum.The copyrights remain with the authors, so, if you wish to publish your text elsewhere, you are entitled to copyright payments on it, you only renounce the copyright revenue from this specific anthology.Ideally, I'd wanted it to be out by Christmas, but we'd like more people on board, there is no deadline to the project, but I'd like it to be out as soon as possible.I'd like to thank the many writers who have contributed so far.If you wish to get in touch, please do it via Twitter @Bulla_Adriano or on Goodreads. Thanks!

This is a project I have been working on for some time: I was contacted by a very worthy Charity, Water.org , whose cause is very, very worthy, as they provide clean water to people who, in a world that we call 'civilised', are still left without, and they asked me to help. So, as there's strength in unity, I have thought of producing an anthology, Words for Water, together with other writers, and give all the copyrights to the Charity.So far, many writers have joined in, but we'd like more, so, if you feel you want to contribute, please get in touch (I will write how to at the bottom of this post).What we are looking for is poems and short stories, which do not have to be about the theme of water, but can, to go in the anthology. There's no word limit (though a full novel would not fit in) nor a word minimum.The copyrights remain with the authors, so, if you wish to publish your text elsewhere, you are entitled to copyright payments on it, you only renounce the copyright revenue from this specific anthology.Ideally, I'd wanted it to be out by Christmas, but we'd like more people on board, there is no deadline to the project, but I'd like it to be out as soon as possible.I'd like to thank the many writers who have contributed so far.If you wish to get in touch, please do it via Twitter @Bulla_Adriano or on Goodreads. Thanks!

Published on December 19, 2014 04:03

December 17, 2014

Political Criticism

Political Criticism

I still remember when I first met this term leafing through the pages of Professor Eagleton's Literary Theory, an Introduction , and how it took me a few minutes to realise why he classed such a wide range of literary theories, from Marxism through Feminist Criticism to Post-Colonial Criticism under the hypernym 'political'; divergent though they are in their developments, they all address the study of Literature from the original diktat of Marxist Criticism, namely that Art is a social product. On reflection, I understand Eagleton's almost derogatory lexical choice, and, having thought about the implications of his taxonomy, I have come to consider the consequences, brought about by the dynamics between Literature and Literary Theory which come from the widespread adoption of these theories.

A glaring example of how these theories are affecting and will affect the whole of Literature is their adoption as pet theories first by universities in the past twenty years or so, and more recently by secondary syllabi around the UK. The A Level 'critical essay' is basically a political essay. Not wishing to use the word indoctrination (ok, here's a cheeky apophasis), we cannot however neglect to remember that behind syllabi imparted to youth of such an 'impressionable age' lurks the shadow of political agenda.

Apart from starting from the same postulate and progressing in their evaluation of literary texts without ever questioning the foundations of their beliefs, these theories place themselves on the diametrical opposite pole to Aestheticism. Although I can see that the tenets of this movement are more easily applicable to Music and the Visual Arts than Literature, if Art for Art's sake is seen as an all encompassing aesthetic and procedural principle, History teaches us that Literature has found it difficult to adhere to it thoroughly, due to the dichotomy our minds have developed between form and content: while Music can be fully self-encompassing and totally shed content, Literature can only do it in very short texts. I shall not indulge in an epistemological argument on whether this dichotomy has sound foundations at this stage (yes, here's praeteritio for you), instead, I wish to salvage literary Aestheticism as a moral imperative: Art should serve its own sake, not society's. This does not mean, of course, that Art ought not to discuss social issues, but that it should have the freedom to do so, as its driving force should not be the amelioration (or pejoration, if one really wishes) of society, though it can be instrumental to it as a corollary of its social impact.

I shall here add a caveat, that Artists have, in my opinion, to answer to the call to duty that comes with the privilege of influence when there is a historical need for it. The irony of the current system is, for example, evident in how the Bush Wars posed, in my opinion, very strong grounds for such call, yet very few Artists responded. The Artist, in fact, can only respond to such call if her or his moral imperative is not tarnished by subservience to ideological and societal influences. The Artist needs the ideological and political freedom to choose if and when her or his Art should have a political message.

It seems clear that political criticism has two functions: the first is presenting Art as subordinate to society, the second is to promote an ideology where Art is no longer independent, but subservient to political agendas, thus denying the freedom necessary for Artists to have the moral grounds to influence society: political criticism serves politics at the expense of Art.

I would go as far as to say that the only theory amongst political ones is Marxism, as it is the only one that proposes a novel way of reading Literature; the others are applications of Marxist Criticism to specific topics, no more than analytical palimpsests, which goes to show how the focus on the servitude to society imposed by these 'theories' has removed the focus from the very nature and heart of Art and redesigned our reading of it along sociological parameters, having found allies in the powers that be, and is, wittingly or not, redrafting the whole of our aesthetic consciousness from without, by means of a common tool in the media that were once in the hands of the Artist: repetitio, variatio and amplificatio.

Oscar Wilde, whom I have chosen to present in the picture at the top of this post, based his witty criticism of society on his artistic freedom, on his belief that Life imitates Art; thus preserving the independence of his pen.

Published on December 17, 2014 04:32

December 16, 2014

The Sound of Poetry

The Sound of Poetry

This is mainly to express my opinions on free verse. A bit like Free Jazz, after its invention by French poets Gustave Kahn and Jules Lafrogue, though, if one counts translation (which in this case I am inclined not to), some argue its real origin goes back to Wycliffe in the Fourteenth Century, when it became popular through the works Whitman and Ginsberg, its revolutionary potential was immediately apparent. Yet, with revolution, also comes the risk of anarchy. In a literary scene that was trying to come to terms with an inconsistent and fragmented world, none less than Ezra Pound dedicated time and his genius to reining in free verse, to the point that, as his most famous disciple stated, 'No verse is free' if the Poet 'wants to do a good job.' Although revolutions are sometimes necessary and often rich in creative opportunities, they also have the awkward tendency of making two mistakes, namely, pushing development into a narrow, blinkered dimension, and wasting the lessons of the past, seen more as an enemy than an interlocutor. By doing so, they are prone to replacing an old mantra for a new one; so, the French Revolution replaced the absolute power of the King with that of the republic, the October Revolution swapped Tzars with Party Leaders, and free verse promoted obsequious deference towards idealism over obsequious deference towards structure. We have seen anarchy in Poetry, though admittedly not whole-pervasive, the very face of Nihilism has been staring at us from behind the mask (yes, it's a reference to Shelley) for some time, and this is evident in how nowadays we find it hard to explain what Poetry is. When things fall apart, recent concepts and definitions are the first to slough off the body of culture, and what we are left with as parameters are the often simpler and less easily assailable ancient ones, thus, digging deep into the many ideas of what Poetry is I have encountered in my life, I shall go back to the oldest I can recall: Poetry is an exceptional use of language. The corollary is ironic when we look at some use of free verse nowadays: whilst Arthur Rimbaud had already experimented prosaic layout of Poetry, which was exceptional at the time, free verse per se is quickly self-exhaustive and self-defeating; if the exceptionality only lies in dividing sentences or grouping words into lines, that is not exceptional any more, and has not been for a very long time. Imagery, we can argue, may be seen as very common in Poetry, yet under careful scrutiny, imagery alone cannot be at the root of what we define as poetry, as it is present in prose as well, so, what percentage of imagery (I am being sarcastic) does a text need to cross the barrier between the two?

Thus, I see myself again going back to Classical Mythology... We all know that the Muses are nine, do we not? Well, not exactly; originally, the Muses were three, Melete, the Muse of practice, Mneme, the Muse of memory and Aeode, the Muse of song. The assignment of discrete disciplines to the Muse is only fully ascertained in Roman Mythology and what I find interesting in the original three Muses is that the first two are dedicated to the skills any artist has to master: practice, of course, goes without saying, though we may wish to remember that in its etymology, the word includes the meaning of 'repeating' and 'contriving', which need models and antecedents for their own execution; memory is, in my view to be read as both a backward and forward movement in time, meaning that Art is innately a memory (even if of a split second before), and also needs to remember itself, I shall add, and is created in the service of future memory; the last one, Aeode, tells us a very important message which goes to the very heart of Poetry: Music and Poetry are the same thing but expressed via different means. This is, of course, corroborated by the oral origin of Poetry, but what I would wish to focus on are the consequences of this.

Poetry to be such needs to have a musical quality, this is exactly where Pound arrived with his work on free verse, and finds Leibniz agreeing with Milton when the former says that 'Music is counting without knowing,' and the latter that it 'consists only in apt numbers, fit quantity of syllables'. Of course, fit does not need to mean 'standard', but suited to the expressive intention. Chopping sentences as if they were cabbages is not Poetry, unless the result is aleatory, in which case, I would think that the reader is the Poet, not the writer.

Going back to my political metaphor, anarchy can only exist if everybody starts with the principle that with freedom comes responsibility, though I have reservations about whether the syntactic structure of this sentence matches the aetiology of an ethical system, thus, with free verse, which in poetic terms we can regard as great, comes great responsibility. This adds a moral dimension that poets cannot ignore: assuming we have all paid our tributes to Melete and practised to refine our skills not disregarding the lessons of our fore-parents, and assuming we have done it so thoroughly that their memory lives in our words, we then have the privilege of choice, and freedom of choice. Thus, if free verse is used as an expressive choice, implying that the poet preferred one, or more, or all the lines of a poem to be 'free' from meter, it is still within the dialogue with Poesy, yet if the use of free verse simply comes from oblivion of meter, we abdicate the title of poets.

I will close this post with a gripe against the educational postulate that says that all students are, for lack of a better word, stupid, and has stopped, out of ideological reasons and obtusity, teaching the old mnemonic on meter and feet, 'Content iamb...' No, I will not finish it, as this has been handed down orally for centuries, and for a reason; because in the very learning of the basic tools of Poetry we remind ourselves that Poetry is, primarily, sound.

Published on December 16, 2014 04:50