Robert M. Kelly's Blog, page 4

July 23, 2015

Wallpaper in the Gilded Age, Part I: Introduction

Wallpaper in the Gilded Age:

A Nine-Part Series Based on Ventfort Hall

by Robert M. Kelly

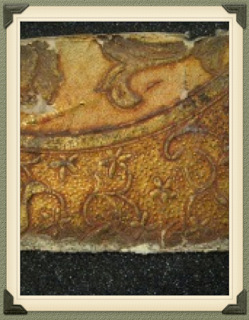

1. "leather" paperI. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

1. "leather" paperI. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

II. 1893: historical context

III. 1893: social context

IV. architectural changes 1850-1910

V. wallpaper's commercial context in the Gilded Age

VI. Wharton's wallpaper complex

VII. revisiting six wallpaper types found at Ventfort Hall

VIII. conclusion

IX. addendum: Cottage Industry: L. C. Peter's Notebook

*** author's note: These blog posts started as a written version of a lecture about six wallpapers found at Ventfort Hall. The six wallpapers are covered in Part I.

I went on. When I came up for breath I had a series of nine parts. I enjoyed exploring the nooks and crannies of related areas such as the architecture and social history of the Berkshire County region, and hope you will, too. Many will wonder in the course of this nook and cranny-ing what the heck happened to those original six wallpapers. Let me assure you: the wallpapers SHALL RETURN in Part VII.

During this work I was introduced by Nini Gilder to the amazing nineteenth-century daybook left behind by L. C. Peters, an accomplished carpenter and fix-it man for the Lenox colony. I decided that his story, (Cottage Industry) belonged here as well. It appears as Part IX.

That said, forward into 1893!

I. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

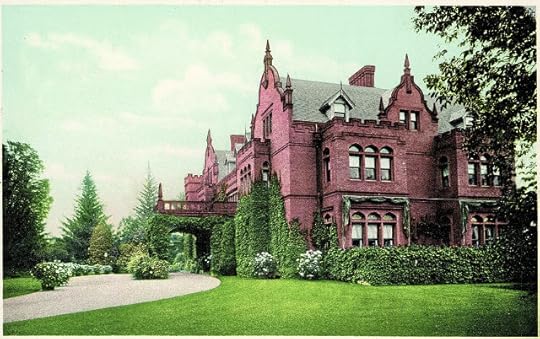

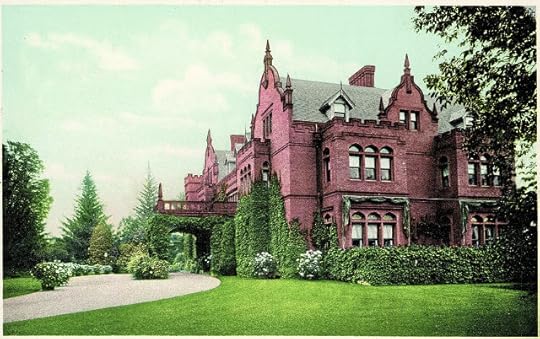

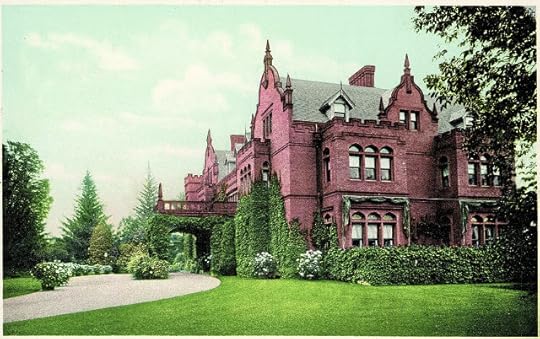

2. period colorized postcard

2. period colorized postcard

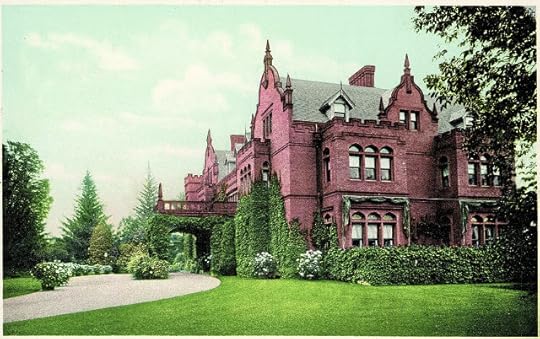

Ventfort Hall, a Jacobean-revival pile in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, was narrowly saved from the wrecking ball around twenty years ago. Volunteers instituted a preservation program which has breathed new life into the 1893 structure. The educational programs of Ventfort Hall explore not only the Hall's history but also the culture of the late Gilded Age during which it was constructed.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

Six seemingly first-generation wallpapers from the house are of prime importance: a leather paper, a block printed floral, a “stenciled look,” a Lincrusta-type, an Anaglypta-type, and a varnished tile.

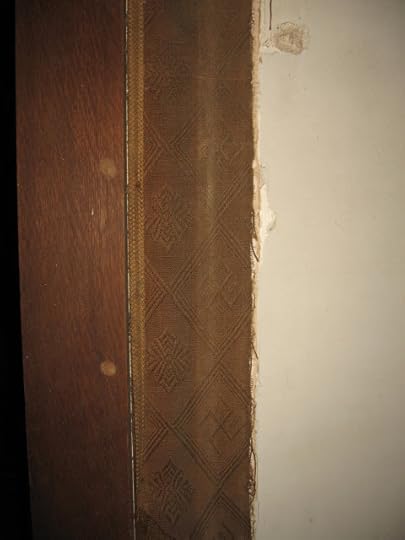

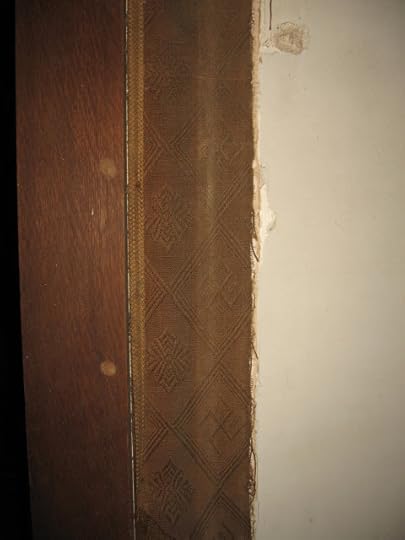

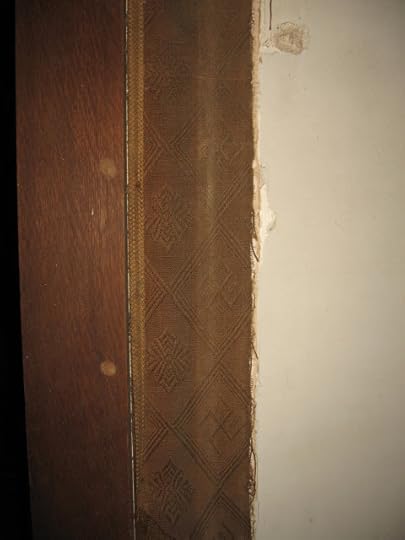

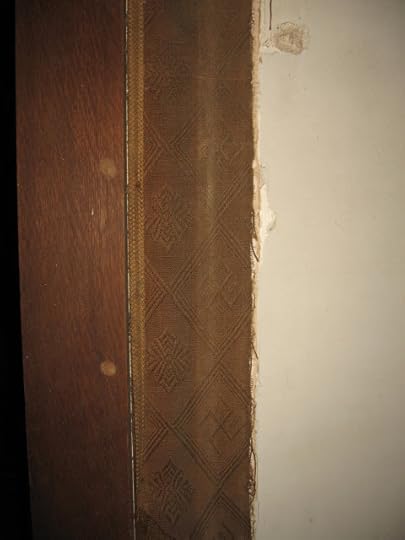

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

Though not adddressed here, fabric was also important at Ventfort Hall. A batten system to which sewn fabric was tacked extended throughout a second-floor hallway in the private quarters and more fabric was hung in the Salon.

When I was asked to give a lecture about Ventfort Hall's wallpaper I gladly accepted. For starters, wallpaper history is literally made up of fragments, and any opportunity to connect the fragments must be taken. Wallpaper was so prolific in the nineteenth century that we’ve resorted to stereotyping it, perhaps in self-defense.

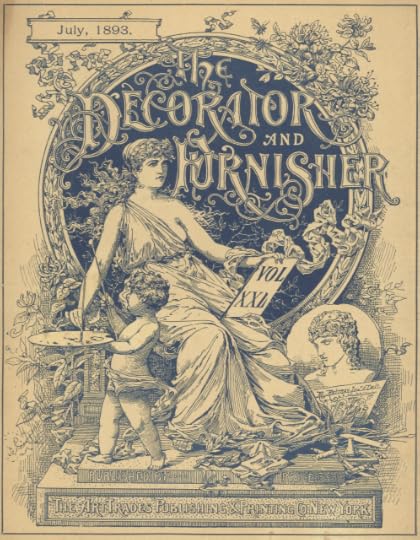

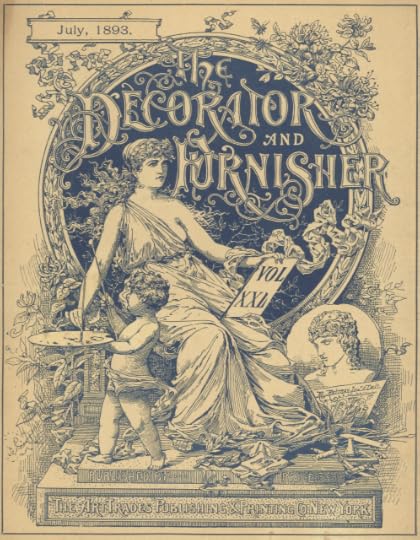

Few eras are stereotyped more firmly than the last decade of the century, when bilious green and red gilt scrolls, like some invasive species from hell, grew wild on ceilings, friezes, sidewalls, and adjoining surfaces. Or did they? In fact, the colors were often pastels, the scrolls COULD be reform influenced, and many wallpapers of the time were painstakingly colored and nicely matched to their surroundings—a claim that cannot be made for every era. Much that has been written about 1890s decoration treats it as a way station, as a time when decoration was either stuck in a rut or desperately trying to advance out of one. The pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the major trade magazine of the time, are vivid testimony that this picture is unfair and inaccurate. To be sure, the writers of the magazine were salesmen. Yet, within their sales vocabulary one can discern a genuine pride in American manufacturing that does not seem misplaced when rare samples of 1890s wallpaper are closely examined.

Other than these concerns, case studies are an excellent way to illuminate a moment in time. The moment here is June, 1893, when the George Hale Morgan family moved into their newly constructed home in Lenox. George's wife, Julia Morgan, brought the Morgan name (and Morgan money) into the marriage — she was the sister of J. P. Morgan. But, as impressive as the house and family are, the wallpaper story associated with them is no less important. It leads us far beyond the Hall—to Chicago, to Europe, and to the White House. It turns out that 1893 was a significant year for architecture, design, and decoration. It was, I believe, a hinge year. Broadly speaking, 1893 witnessed the last stand of the picturesque and a resurgence of classicism. The first suggestion of complexity came when my colleague Bo Sullivan sent several gigabytes of information gleaned from the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the New York City trade magazine which ran from 1882 to 1897.

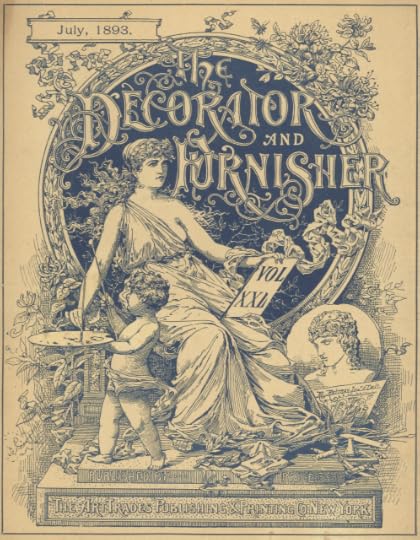

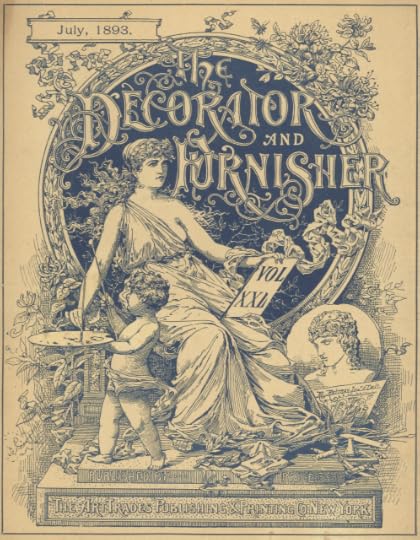

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

The magazine's style was not quite what I expected. The early 90s are known for grandiosity, but the depth of it displayed in the magazine was surprising. Some historians have proposed that by the early 90s a shift toward the cleaner styles of classicism had occurred and that this forward-looking change was visible in the buildings and plan of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. These buildings are discussed below. While there is some truth to the claims, upper-class style in 1893, on the evidence of the contemporaneous commercial press, seems, in my opinion, to have been looking not forward, but backward. Back past the short 120-year span of the United States. Back to Europe and to post-medieval if not medieval times. Back to shields, heraldry, mottos, nationalism, and the “colors of woven tapestry” as one writer put it. To some extent, this conservative outlook dovetailed with the design of American wallpapers in the late-nineteenth century, which were often florid, in the sense of flower-based. But, the high-style decoration encountered in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher went further. It was florid in the sense of exceptionally ornate. This extended to the house style of the magazine.

Although a shift to pared-down styles was certainly in the wind, this de-cluttering is hardly in evidence in much of the documentation from 1893. This makes the somewhat retrograde wallpaper choices of the Morgans more understandable. Yet, it left unanswered the questions that we always have about wallpaper, namely: how popular were these choices?; how expensive were the wallpapers?; how exclusive were they?; were they domestically produced? how did the style of the wallpapers relate to the style of the house? This series of posts aims to answer some of these questions.

Ventfort Hall was build by Rotch & Tilden, a Boston firm, and housed George Hale Morgan and his wife, the former Sarah Spencer Morgan, a distant cousin of George. The house was the most expensive building project yet in an area known for expensive building projects.[1]

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

The first samples to consider are the so-called leather papers. These oblong scraps were found beneath the cornice moldings in the first-floor hallway. Leather papers were highly processed. They were created by embossing and finishing paper laminates to approximate the effect of gilt leather. There seems to have been a shift from multiple layers to single layers as machine embossing improved. Leather papers were often promoted in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher. During a review of the offerings of Warren, Fuller & Company, a writer stated: "We must not forget to mention the leather papers. The most striking one is the Heraldic shield pattern. Unusual care has been taken in producing this high relief effect. These are well named, as they retain the character color and texture of stamped leather. Architects and others will be gratified in finding so close a resemblance."[2] This direct appeal to architects is telling, for it would have been Arthur Rotch or George Tilden who chose, or, have had a hand in choosing, the interior finishes. Both were trained for this creative role at the Beaux Arts school in Paris.

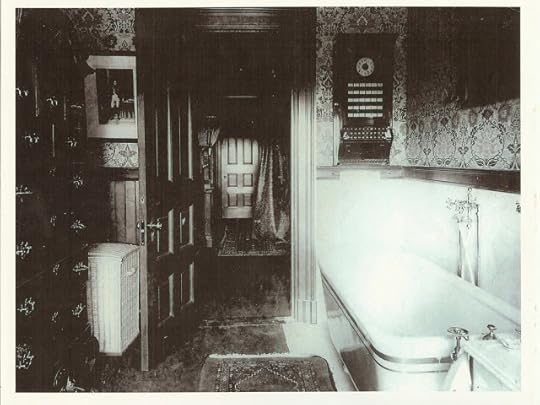

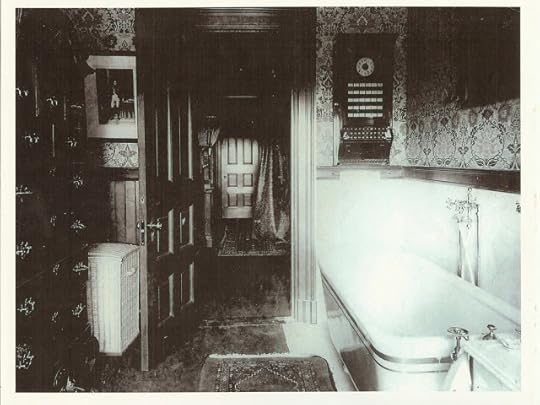

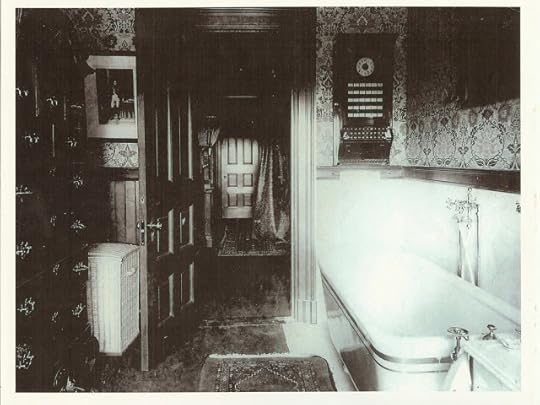

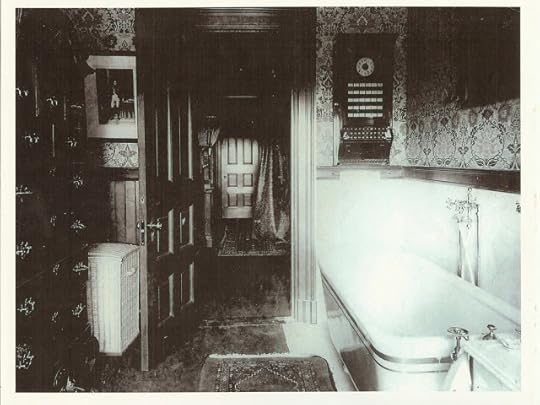

7. block printed floral in 1894

7. block printed floral in 1894

This block printed floral was found in a bathroom thought to be Sarah's. Even though the design and colors are elaborate, the wallpaper conforms to English reform design principles. The flowers are not naturalistic but instead symmetrical, two-dimensional flowers. The strange object on the bathroom wall was apparently part of the burglar alarm system.

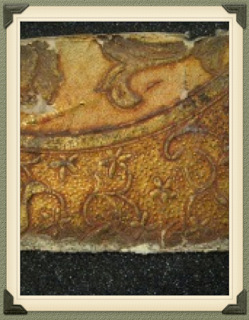

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

9. "stenciled look"

9. "stenciled look"

The next pattern has been dubbed a “stenciled look.” The two colors are simply rendered in a post-medieval style, but the vertical repeat is very long—55". This wallpaper was almost certainly created with block prints, and therefore expensive. This looming pattern decorated the wide third-floor hallways outside of the guest rooms. Incidentally, the pattern as rendered here is askew, due to the preserved strip of wallpaper twisting in mid-air.

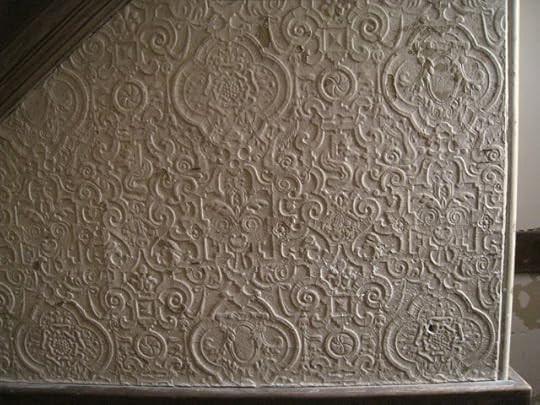

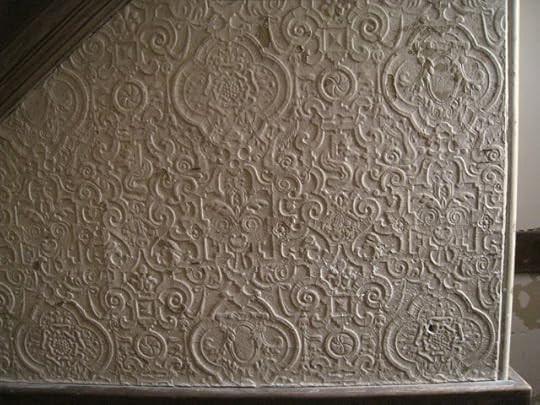

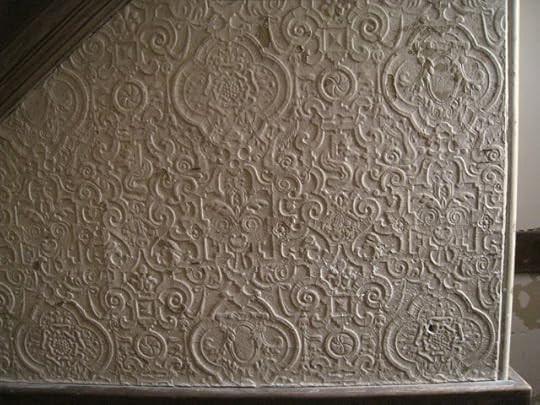

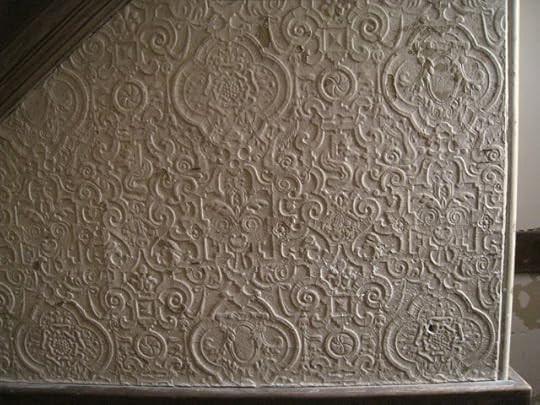

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

Neither of the manufacturers of the service-hall papers are known. Both the Anaglypta-type (above the dado) and the Lincrusta-type (below the dado) were hung throughout the three floors of the hallway, mute witnesses to the hustle and bustle of household chores. With its spear and shaft motifs the Lincrusta-type presents a somewhat military aspect, albeit the beaded molding and rigid fluting hint at a Classic Revival effect. Both Lincrusta (from 1877) and Anaglypta (from 1887) were English patented products, though there was an American licensee for Lincrusta—Beck—who ran a Connecticut factory.

“Lincrusta-Walton” is often encountered in advertising of the period. Lincrusta was developed by Frederick Walton, inventor of linoleum, while Anaglypta was invented and patented by Thomas Palmer, an employee of Walton. The distinction between the types is that Lincrusta is solid, being made from linseed oil, cork, and other materials which were forced under pressure and great heat into molds. Anaglypta, on the other hand, was hollow, and made from pulp. Thus Anaglypta was cheaper and often used overhead. With a few coats of paint, the Anaglypta types could stand up to regular wear and tear.

12. varnished tile

12. varnished tile

The final paper under consideration is a varnished tile wallpaper which still hangs in a third-floor bathroom. The offerings of Nevius and Haviland were reviewed in 1893 by The Decorator and Furnisher [3]: "That branch of their sanitary grade known as tile patterns contain some new and rarely beautiful designs. There are tile effects with Empire patterns and blue and white, green and white, soft red and white, and other combination, all washable and sanitary, and suitable for halls, kitchens and bathrooms. These goods are artistic, durable and cheap...."

The hygienic aspect of sanitary papers was hugely important to a late-Victorian audience. The company's pitch for varnished tile papers combines this virtue with others: varnished tile wallpaper was artistic, rarely beautiful, durable, and yet, for all that...cheap!—suggesting that low cost was a high value for producers and consumers alike. The varnished tile paper at Ventfort Hall, with its several colors, is a step up from the description in the magazine, but not by much. As we shall see, varnished tiles, like most wallpapers, came in a variety of grades, some of which found their way into other large estates in the Berkshire hills during the Gilded Age.

=====

footnotes:

[1] Gilder and Jackson, Houses of the Berkshires, 1870-1930: The Architecture of Leisure, 2011, p. 132. Some of the wealth which created Ventfort Hall was inherited by Sarah from her father, Junius Spencer Morgan, who was killed in a freak carriage accident in 1890. The Ventfort Hall complex included six greenhouses on 26 acres. The house had 15 bedrooms, 13 bathrooms, 17 fireplaces, billiard room, bowling alley, elevator, burglar alarms, and central heating.

For more about Ventfort Hall:

http://gildedage.org/history/

Before and after photos are at John Foreman's blog site:

http://bigoldhouses.blogspot.com/2012/02/hairbreadth-escape.html

[2] The Decorator and Furnisher, V. 23, N. 4 (July, 1893) p. 147.

[3] The Decorator and Furnisher, V. 23, N. 6 (September, 1893) p. 223.

=====

captions:

1 - 4. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

5. cover, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine, courtesy Bolling & Company Archive.

6 - 8. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

9. © WallpaperScholar.Com

10 - 12. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

A Nine-Part Series Based on Ventfort Hall

by Robert M. Kelly

1. "leather" paperI. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

1. "leather" paperI. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort HallII. 1893: historical context

III. 1893: social context

IV. architectural changes 1850-1910

V. wallpaper's commercial context in the Gilded Age

VI. Wharton's wallpaper complex

VII. revisiting six wallpaper types found at Ventfort Hall

VIII. conclusion

IX. addendum: Cottage Industry: L. C. Peter's Notebook

*** author's note: These blog posts started as a written version of a lecture about six wallpapers found at Ventfort Hall. The six wallpapers are covered in Part I.

I went on. When I came up for breath I had a series of nine parts. I enjoyed exploring the nooks and crannies of related areas such as the architecture and social history of the Berkshire County region, and hope you will, too. Many will wonder in the course of this nook and cranny-ing what the heck happened to those original six wallpapers. Let me assure you: the wallpapers SHALL RETURN in Part VII.

During this work I was introduced by Nini Gilder to the amazing nineteenth-century daybook left behind by L. C. Peters, an accomplished carpenter and fix-it man for the Lenox colony. I decided that his story, (Cottage Industry) belonged here as well. It appears as Part IX.

That said, forward into 1893!

I. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

2. period colorized postcard

2. period colorized postcardVentfort Hall, a Jacobean-revival pile in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, was narrowly saved from the wrecking ball around twenty years ago. Volunteers instituted a preservation program which has breathed new life into the 1893 structure. The educational programs of Ventfort Hall explore not only the Hall's history but also the culture of the late Gilded Age during which it was constructed.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.Six seemingly first-generation wallpapers from the house are of prime importance: a leather paper, a block printed floral, a “stenciled look,” a Lincrusta-type, an Anaglypta-type, and a varnished tile.

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floorThough not adddressed here, fabric was also important at Ventfort Hall. A batten system to which sewn fabric was tacked extended throughout a second-floor hallway in the private quarters and more fabric was hung in the Salon.

When I was asked to give a lecture about Ventfort Hall's wallpaper I gladly accepted. For starters, wallpaper history is literally made up of fragments, and any opportunity to connect the fragments must be taken. Wallpaper was so prolific in the nineteenth century that we’ve resorted to stereotyping it, perhaps in self-defense.

Few eras are stereotyped more firmly than the last decade of the century, when bilious green and red gilt scrolls, like some invasive species from hell, grew wild on ceilings, friezes, sidewalls, and adjoining surfaces. Or did they? In fact, the colors were often pastels, the scrolls COULD be reform influenced, and many wallpapers of the time were painstakingly colored and nicely matched to their surroundings—a claim that cannot be made for every era. Much that has been written about 1890s decoration treats it as a way station, as a time when decoration was either stuck in a rut or desperately trying to advance out of one. The pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the major trade magazine of the time, are vivid testimony that this picture is unfair and inaccurate. To be sure, the writers of the magazine were salesmen. Yet, within their sales vocabulary one can discern a genuine pride in American manufacturing that does not seem misplaced when rare samples of 1890s wallpaper are closely examined.

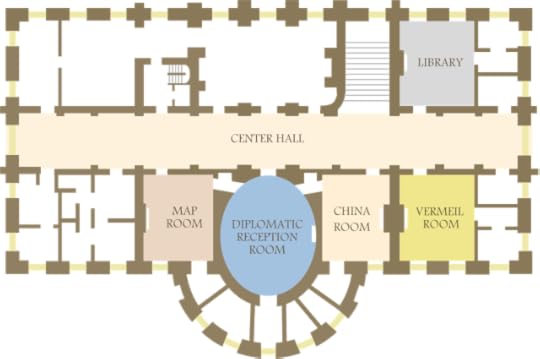

Other than these concerns, case studies are an excellent way to illuminate a moment in time. The moment here is June, 1893, when the George Hale Morgan family moved into their newly constructed home in Lenox. George's wife, Julia Morgan, brought the Morgan name (and Morgan money) into the marriage — she was the sister of J. P. Morgan. But, as impressive as the house and family are, the wallpaper story associated with them is no less important. It leads us far beyond the Hall—to Chicago, to Europe, and to the White House. It turns out that 1893 was a significant year for architecture, design, and decoration. It was, I believe, a hinge year. Broadly speaking, 1893 witnessed the last stand of the picturesque and a resurgence of classicism. The first suggestion of complexity came when my colleague Bo Sullivan sent several gigabytes of information gleaned from the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the New York City trade magazine which ran from 1882 to 1897.

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazineThe magazine's style was not quite what I expected. The early 90s are known for grandiosity, but the depth of it displayed in the magazine was surprising. Some historians have proposed that by the early 90s a shift toward the cleaner styles of classicism had occurred and that this forward-looking change was visible in the buildings and plan of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. These buildings are discussed below. While there is some truth to the claims, upper-class style in 1893, on the evidence of the contemporaneous commercial press, seems, in my opinion, to have been looking not forward, but backward. Back past the short 120-year span of the United States. Back to Europe and to post-medieval if not medieval times. Back to shields, heraldry, mottos, nationalism, and the “colors of woven tapestry” as one writer put it. To some extent, this conservative outlook dovetailed with the design of American wallpapers in the late-nineteenth century, which were often florid, in the sense of flower-based. But, the high-style decoration encountered in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher went further. It was florid in the sense of exceptionally ornate. This extended to the house style of the magazine.

Although a shift to pared-down styles was certainly in the wind, this de-cluttering is hardly in evidence in much of the documentation from 1893. This makes the somewhat retrograde wallpaper choices of the Morgans more understandable. Yet, it left unanswered the questions that we always have about wallpaper, namely: how popular were these choices?; how expensive were the wallpapers?; how exclusive were they?; were they domestically produced? how did the style of the wallpapers relate to the style of the house? This series of posts aims to answer some of these questions.

Ventfort Hall was build by Rotch & Tilden, a Boston firm, and housed George Hale Morgan and his wife, the former Sarah Spencer Morgan, a distant cousin of George. The house was the most expensive building project yet in an area known for expensive building projects.[1]

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

6. "leather" paper in Long HallThe first samples to consider are the so-called leather papers. These oblong scraps were found beneath the cornice moldings in the first-floor hallway. Leather papers were highly processed. They were created by embossing and finishing paper laminates to approximate the effect of gilt leather. There seems to have been a shift from multiple layers to single layers as machine embossing improved. Leather papers were often promoted in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher. During a review of the offerings of Warren, Fuller & Company, a writer stated: "We must not forget to mention the leather papers. The most striking one is the Heraldic shield pattern. Unusual care has been taken in producing this high relief effect. These are well named, as they retain the character color and texture of stamped leather. Architects and others will be gratified in finding so close a resemblance."[2] This direct appeal to architects is telling, for it would have been Arthur Rotch or George Tilden who chose, or, have had a hand in choosing, the interior finishes. Both were trained for this creative role at the Beaux Arts school in Paris.

7. block printed floral in 1894

7. block printed floral in 1894This block printed floral was found in a bathroom thought to be Sarah's. Even though the design and colors are elaborate, the wallpaper conforms to English reform design principles. The flowers are not naturalistic but instead symmetrical, two-dimensional flowers. The strange object on the bathroom wall was apparently part of the burglar alarm system.

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm 9. "stenciled look"

9. "stenciled look"The next pattern has been dubbed a “stenciled look.” The two colors are simply rendered in a post-medieval style, but the vertical repeat is very long—55". This wallpaper was almost certainly created with block prints, and therefore expensive. This looming pattern decorated the wide third-floor hallways outside of the guest rooms. Incidentally, the pattern as rendered here is askew, due to the preserved strip of wallpaper twisting in mid-air.

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall 11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hallNeither of the manufacturers of the service-hall papers are known. Both the Anaglypta-type (above the dado) and the Lincrusta-type (below the dado) were hung throughout the three floors of the hallway, mute witnesses to the hustle and bustle of household chores. With its spear and shaft motifs the Lincrusta-type presents a somewhat military aspect, albeit the beaded molding and rigid fluting hint at a Classic Revival effect. Both Lincrusta (from 1877) and Anaglypta (from 1887) were English patented products, though there was an American licensee for Lincrusta—Beck—who ran a Connecticut factory.

“Lincrusta-Walton” is often encountered in advertising of the period. Lincrusta was developed by Frederick Walton, inventor of linoleum, while Anaglypta was invented and patented by Thomas Palmer, an employee of Walton. The distinction between the types is that Lincrusta is solid, being made from linseed oil, cork, and other materials which were forced under pressure and great heat into molds. Anaglypta, on the other hand, was hollow, and made from pulp. Thus Anaglypta was cheaper and often used overhead. With a few coats of paint, the Anaglypta types could stand up to regular wear and tear.

12. varnished tile

12. varnished tileThe final paper under consideration is a varnished tile wallpaper which still hangs in a third-floor bathroom. The offerings of Nevius and Haviland were reviewed in 1893 by The Decorator and Furnisher [3]: "That branch of their sanitary grade known as tile patterns contain some new and rarely beautiful designs. There are tile effects with Empire patterns and blue and white, green and white, soft red and white, and other combination, all washable and sanitary, and suitable for halls, kitchens and bathrooms. These goods are artistic, durable and cheap...."

The hygienic aspect of sanitary papers was hugely important to a late-Victorian audience. The company's pitch for varnished tile papers combines this virtue with others: varnished tile wallpaper was artistic, rarely beautiful, durable, and yet, for all that...cheap!—suggesting that low cost was a high value for producers and consumers alike. The varnished tile paper at Ventfort Hall, with its several colors, is a step up from the description in the magazine, but not by much. As we shall see, varnished tiles, like most wallpapers, came in a variety of grades, some of which found their way into other large estates in the Berkshire hills during the Gilded Age.

=====

footnotes:

[1] Gilder and Jackson, Houses of the Berkshires, 1870-1930: The Architecture of Leisure, 2011, p. 132. Some of the wealth which created Ventfort Hall was inherited by Sarah from her father, Junius Spencer Morgan, who was killed in a freak carriage accident in 1890. The Ventfort Hall complex included six greenhouses on 26 acres. The house had 15 bedrooms, 13 bathrooms, 17 fireplaces, billiard room, bowling alley, elevator, burglar alarms, and central heating.

For more about Ventfort Hall:

http://gildedage.org/history/

Before and after photos are at John Foreman's blog site:

http://bigoldhouses.blogspot.com/2012/02/hairbreadth-escape.html

[2] The Decorator and Furnisher, V. 23, N. 4 (July, 1893) p. 147.

[3] The Decorator and Furnisher, V. 23, N. 6 (September, 1893) p. 223.

=====

captions:

1 - 4. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

5. cover, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine, courtesy Bolling & Company Archive.

6 - 8. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

9. © WallpaperScholar.Com

10 - 12. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

Published on July 23, 2015 22:46

Wallpaper in the Gilded Age: Part I

Wallpaper in the Gilded Age:

A Nine-Part Series Based on Ventfort Hall

I. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

II. 1893: historical context

III. 1893: social context

IV. architectural changes 1850-1910

V. wallpaper's commercial context in the Gilded Age

VI. Wharton's wallpaper complex

VII. revisiting six wallpaper types found at Ventfort Hall

VIII. conclusion

IX. addendum: Cottage Industry: L. C. Peter's Notebook

* * * author's note: These blog posts started as a written version of a lecture about six wallpapers found at Ventfort Hall. The six wallpapers are covered in Part I.

I went on. When I came up for breath I had a series of 9 parts. I enjoyed exploring the nooks and crannies of related areas such as the architecture and social history of the Berkshire County region, and hope you will, too. Many will wonder in the course of this nook and cranny-ing what the devil happened to those original six wallpapers. Let me assure you: the wallpapers SHALL RETURN in Part VII.

During this work I was introduced by Nini Gilder to the amazing 19th century daybook left behind by L. C. Peters, an accomplished carpenter and fix-it man for the Lenox colony. I decided that his story belonged here as well. "Cottage Industry" appears as Part IX.

That said, forward into 1893!

1. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

1. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

I. six types of wallpaper

2. period colorized postcard

2. period colorized postcard

Ventfort Hall, a Jacobean-revival pile in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, was narrowly saved from the wrecking ball around twenty years ago. Volunteers instituted a preservation program which has breathed new life into the 1893 structure. The educational programs of Ventfort Hall explore not only the Hall's history but also the culture of the late Gilded Age during which it was constructed.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

Six seemingly first-generation wallpapers from the house are of prime importance: a leather paper, a block printed floral, a “stenciled look,” a Lincrusta-type, an Anaglypta-type, and a varnished tile.

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

Though not adddressed here, fabric was also important at Ventfort Hall. A batten system to which sewn fabric was tacked extended throughout a second-floor hallway in the private quarters and more fabric was hung in the Salon.

When I was asked to give a lecture about Ventfort Hall's wallpaper I gladly accepted. For starters, wallpaper history is literally made up of fragments, and any opportunity to connect the fragments must be taken. Wallpaper was so prolific in the nineteenth century that we’ve resorted to stereotyping it, perhaps in self-defense.

Few eras are stereotyped more firmly than the last decade of the century, when bilious green and red gilt scrolls, like some invasive species from hell, grew wild on ceilings, friezes, sidewalls, and adjoining surfaces. Or did they? In fact, the colors were often pastels, the scrolls COULD be reform influenced, and many wallpapers of the time were painstakingly colored and nicely matched to their surroundings—a claim that cannot be made for every era. Much that has been written about 1890s decoration treats it as a way station, as a time when decoration was either stuck in a rut or desperately trying to advance out of one. The pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the major trade magazine of the time, are vivid testimony that this picture is unfair and inaccurate. To be sure, the writers of the magazine were salesmen. Yet, within their sales vocabulary one can discern a genuine pride in American manufacturing that does not seem misplaced when rare samples of 1890s wallpaper are closely examined.

Other than these concerns, case studies are an excellent way to illuminate a moment in time. The moment here is June, 1893, when the George Hale Morgan family moved into their newly constructed home in Lenox. George's wife, Julia Morgan, brought the Morgan name (and Morgan money) into the marriage — she was the sister of J. P. Morgan. But, as impressive as the house and family are, the wallpaper story associated with them is no less important. It leads us far beyond the Hall—to Chicago, to Europe, and to the White House. It turns out that 1893 was a significant year for architecture, design, and decoration. It was, I believe, a hinge year. Broadly speaking, 1893 witnessed the last stand of the picturesque and a resurgence of classicism. The first suggestion of complexity came when my colleague Bo Sullivan sent several gigabytes of information gleaned from the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the New York City trade magazine which ran from 1882 to 1897.

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

The magazine's style was not quite what I expected. The early 90s are known for grandiosity, but the depth of it displayed in the magazine was surprising. Some historians have proposed that by the early 90s a shift toward the cleaner styles of classicism had occurred and that this forward-looking change was visible in the buildings and plan of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. These buildings are discussed below. While there is some truth to the claims, upper-class style in 1893, on the evidence of the contemporaneous commercial press, seems, in my opinion, to have been looking not forward, but backward. Back past the short 120-year span of the United States. Back to Europe and to post-medieval if not medieval times. Back to shields, heraldry, mottos, nationalism, and the “colors of woven tapestry” as one writer put it. To some extent, this conservative outlook dovetailed with the design of American wallpapers in the late-nineteenth century, which were often florid, in the sense of flower-based. But, the high-style decoration encountered in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher went further. It was florid in the sense of exceptionally ornate. This ornateness extended to the house style of the magazine.

Although the shift to pared-down styles certainly occurred going forward, this de-cluttering is hardly in evidence in the available documentation from 1893. This makes the somewhat retrograde wallpaper choices of the Morgans more understandable. Yet, it left unanswered the questions that we always have about wallpaper, namely: how popular were these choices?; how expensive were the wallpapers?; how exclusive were they?; were they domestically produced? how did the style of the wallpapers relate to the style of the house? This series of posts aims to answer some of these questions.

Ventfort Hall was build by Rotch & Tilden, a Boston firm, and housed George Hale Morgan and his wife, the former Sarah Spencer Morgan, a distant cousin of George. The house was the most expensive building project yet in an area known for expensive building projects.[1]

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

The first samples to consider are the so-called leather papers. These oblong scraps were found beneath the cornice moldings in the first-floor hallway. Leather papers were highly processed. They were created by embossing and finishing paper laminates to approximate the effect of gilt leather. There seems to have been a shift from multiple layers to single layers as machine embossing improved. Leather papers were often promoted in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher. During a review of the offerings of Warren, Fuller & Company, a writer stated: "We must not forget to mention the leather papers. The most striking one is the Heraldic shield pattern. Unusual care has been taken in producing this high relief effect. These are well named, as they retain the character color and texture of stamped leather. Architects and others will be gratified in finding so close a resemblance."[2] This direct appeal to architects is telling, for it would have been Arthur Rotch or George Tilden who chose, or, have had a hand in choosing, the interior finishes. Both were trained for this creative role at the Beaux Arts school in Paris.

7. block printed floral in 1894

7. block printed floral in 1894

This block printed floral was found in a bathroom thought to be Sarah's. Even though the design and colors are elaborate, the wallpaper conforms to English reform design principles. The flowers are not naturalistic but instead symmetrical, two-dimensional flowers. The strange object on the bathroom wall was apparently part of the burglar alarm system.

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

9. "stenciled look"

9. "stenciled look"

The next pattern has been dubbed a “stenciled look.” The two colors are simply rendered in a post-medieval style, but the vertical repeat is very long—55". This wallpaper was almost certainly created with block prints, and therefore expensive. This looming pattern decorated the wide third-floor hallways outside of the guest rooms. Incidentally, the pattern as rendered here is askew, due to the preserved strip of wallpaper twisting in mid-air.

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

Neither of the manufacturers of the service-hall papers are known. Both the Anaglypta-type (above the dado) and the Lincrusta-type (below the dado) were hung throughout the three floors of the hallway, mute witnesses to the hustle and bustle of household chores. With its spear and shaft motifs the Lincrusta-type presents a somewhat military aspect, albeit the beaded molding and rigid fluting hint at a Classic Revival effect. Both Lincrusta (from 1877) and Anaglypta (from 1887) were English patented products, though there was an American licensee for Lincrusta—Beck—who ran a Connecticut factory.

“Lincrusta-Walton” is often encountered in advertising of the period. Lincrusta was developed by Frederick Walton, inventor of linoleum, while Anaglypta was invented and patented by Thomas Palmer, an employee of Walton. The distinction between the types is that Lincrusta is solid, being made from linseed oil, cork, and other materials which were forced under pressure and great heat into molds. Anaglypta, on the other hand, was hollow, and made from pulp. Thus Anaglypta was cheaper and often used overhead. With a few coats of paint, the Anaglypta types could stand up to regular wear and tear.

12. varnished tile

12. varnished tile

The final paper under consideration is a varnished tile wallpaper which still hangs in an upper-story bathroom. The Decorator and Furnisher reviewed the offerings of Nevius and Haviland on p. 223 of the September, 1893 issue: "That branch of their sanitary grade known as tile patterns contain some new and rarely beautiful designs. There are tile effects with Empire patterns and blue and white, green and white, soft red and white, and other combination, all washable and sanitary, and suitable for halls, kitchens and bathrooms. These goods are artistic, durable and cheap...."

The hygienic aspect of sanitary papers was hugely important to a late-Victorian audience. The pitch for varnished tile papers above combines this virtue with others: artistic, “rarely beautiful,” durable, and yet, for all that...cheap!—suggesting that low cost was a high value for producers and consumers alike. The varnished tile paper at Ventfort Hall, with its several colors, is a step up from the description in the magazine, but not by much. As we shall see, varnished tiles, like most wallpapers, came in a variety of grades, some of which found their way into other large estates in the Berkshire hills.

=====

footnotes:

[1] Gilder and Jackson, Houses of the Berkshires, 1870-1930: The Architecture of Leisure, 2011, p. 132. Some of the wealth which created Ventfort Hall was inherited by Sarah from her father, Junius Spencer Morgan, who was killed in a freak carriage accident in 1890. The Ventfort Hall complex included six greenhouses on 26 acres. The house had 15 bedrooms, 13 bathrooms, 17 fireplaces, billiard room, bowling alley, elevator, burglar alarms, and central heating.

For more about Ventfort Hall:

http://gildedage.org/history/

Before and after photos are at John Foreman's blog site:

http://bigoldhouses.blogspot.com/2012...

[2] The Decorator and Furnisher, July, 1893, p. 147.

=====

captions:

1. masthead, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

2 - 4. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

5. cover, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine.

6 - 8. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

9. © WallpaperScholar.Com

10 - 12. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

A Nine-Part Series Based on Ventfort Hall

I. introduction to six types of historic wallpaper found at Ventfort Hall

II. 1893: historical context

III. 1893: social context

IV. architectural changes 1850-1910

V. wallpaper's commercial context in the Gilded Age

VI. Wharton's wallpaper complex

VII. revisiting six wallpaper types found at Ventfort Hall

VIII. conclusion

IX. addendum: Cottage Industry: L. C. Peter's Notebook

* * * author's note: These blog posts started as a written version of a lecture about six wallpapers found at Ventfort Hall. The six wallpapers are covered in Part I.

I went on. When I came up for breath I had a series of 9 parts. I enjoyed exploring the nooks and crannies of related areas such as the architecture and social history of the Berkshire County region, and hope you will, too. Many will wonder in the course of this nook and cranny-ing what the devil happened to those original six wallpapers. Let me assure you: the wallpapers SHALL RETURN in Part VII.

During this work I was introduced by Nini Gilder to the amazing 19th century daybook left behind by L. C. Peters, an accomplished carpenter and fix-it man for the Lenox colony. I decided that his story belonged here as well. "Cottage Industry" appears as Part IX.

That said, forward into 1893!

1. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

1. The Decorator and Furnisher magazineI. six types of wallpaper

2. period colorized postcard

2. period colorized postcardVentfort Hall, a Jacobean-revival pile in Lenox, Berkshire County, Massachusetts, was narrowly saved from the wrecking ball around twenty years ago. Volunteers instituted a preservation program which has breathed new life into the 1893 structure. The educational programs of Ventfort Hall explore not only the Hall's history but also the culture of the late Gilded Age during which it was constructed.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.

3. Ventfort Hall in disarray: the view from the basement looking up through the collapsed floor to the dining room.Six seemingly first-generation wallpapers from the house are of prime importance: a leather paper, a block printed floral, a “stenciled look,” a Lincrusta-type, an Anaglypta-type, and a varnished tile.

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floor

4. fabric remnant on 2nd floorThough not adddressed here, fabric was also important at Ventfort Hall. A batten system to which sewn fabric was tacked extended throughout a second-floor hallway in the private quarters and more fabric was hung in the Salon.

When I was asked to give a lecture about Ventfort Hall's wallpaper I gladly accepted. For starters, wallpaper history is literally made up of fragments, and any opportunity to connect the fragments must be taken. Wallpaper was so prolific in the nineteenth century that we’ve resorted to stereotyping it, perhaps in self-defense.

Few eras are stereotyped more firmly than the last decade of the century, when bilious green and red gilt scrolls, like some invasive species from hell, grew wild on ceilings, friezes, sidewalls, and adjoining surfaces. Or did they? In fact, the colors were often pastels, the scrolls COULD be reform influenced, and many wallpapers of the time were painstakingly colored and nicely matched to their surroundings—a claim that cannot be made for every era. Much that has been written about 1890s decoration treats it as a way station, as a time when decoration was either stuck in a rut or desperately trying to advance out of one. The pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the major trade magazine of the time, are vivid testimony that this picture is unfair and inaccurate. To be sure, the writers of the magazine were salesmen. Yet, within their sales vocabulary one can discern a genuine pride in American manufacturing that does not seem misplaced when rare samples of 1890s wallpaper are closely examined.

Other than these concerns, case studies are an excellent way to illuminate a moment in time. The moment here is June, 1893, when the George Hale Morgan family moved into their newly constructed home in Lenox. George's wife, Julia Morgan, brought the Morgan name (and Morgan money) into the marriage — she was the sister of J. P. Morgan. But, as impressive as the house and family are, the wallpaper story associated with them is no less important. It leads us far beyond the Hall—to Chicago, to Europe, and to the White House. It turns out that 1893 was a significant year for architecture, design, and decoration. It was, I believe, a hinge year. Broadly speaking, 1893 witnessed the last stand of the picturesque and a resurgence of classicism. The first suggestion of complexity came when my colleague Bo Sullivan sent several gigabytes of information gleaned from the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher, the New York City trade magazine which ran from 1882 to 1897.

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

5. The Decorator and Furnisher magazineThe magazine's style was not quite what I expected. The early 90s are known for grandiosity, but the depth of it displayed in the magazine was surprising. Some historians have proposed that by the early 90s a shift toward the cleaner styles of classicism had occurred and that this forward-looking change was visible in the buildings and plan of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. These buildings are discussed below. While there is some truth to the claims, upper-class style in 1893, on the evidence of the contemporaneous commercial press, seems, in my opinion, to have been looking not forward, but backward. Back past the short 120-year span of the United States. Back to Europe and to post-medieval if not medieval times. Back to shields, heraldry, mottos, nationalism, and the “colors of woven tapestry” as one writer put it. To some extent, this conservative outlook dovetailed with the design of American wallpapers in the late-nineteenth century, which were often florid, in the sense of flower-based. But, the high-style decoration encountered in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher went further. It was florid in the sense of exceptionally ornate. This ornateness extended to the house style of the magazine.

Although the shift to pared-down styles certainly occurred going forward, this de-cluttering is hardly in evidence in the available documentation from 1893. This makes the somewhat retrograde wallpaper choices of the Morgans more understandable. Yet, it left unanswered the questions that we always have about wallpaper, namely: how popular were these choices?; how expensive were the wallpapers?; how exclusive were they?; were they domestically produced? how did the style of the wallpapers relate to the style of the house? This series of posts aims to answer some of these questions.

Ventfort Hall was build by Rotch & Tilden, a Boston firm, and housed George Hale Morgan and his wife, the former Sarah Spencer Morgan, a distant cousin of George. The house was the most expensive building project yet in an area known for expensive building projects.[1]

6. "leather" paper in Long Hall

6. "leather" paper in Long HallThe first samples to consider are the so-called leather papers. These oblong scraps were found beneath the cornice moldings in the first-floor hallway. Leather papers were highly processed. They were created by embossing and finishing paper laminates to approximate the effect of gilt leather. There seems to have been a shift from multiple layers to single layers as machine embossing improved. Leather papers were often promoted in the pages of The Decorator and Furnisher. During a review of the offerings of Warren, Fuller & Company, a writer stated: "We must not forget to mention the leather papers. The most striking one is the Heraldic shield pattern. Unusual care has been taken in producing this high relief effect. These are well named, as they retain the character color and texture of stamped leather. Architects and others will be gratified in finding so close a resemblance."[2] This direct appeal to architects is telling, for it would have been Arthur Rotch or George Tilden who chose, or, have had a hand in choosing, the interior finishes. Both were trained for this creative role at the Beaux Arts school in Paris.

7. block printed floral in 1894

7. block printed floral in 1894This block printed floral was found in a bathroom thought to be Sarah's. Even though the design and colors are elaborate, the wallpaper conforms to English reform design principles. The flowers are not naturalistic but instead symmetrical, two-dimensional flowers. The strange object on the bathroom wall was apparently part of the burglar alarm system.

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm

8. recent photo of block printed floral remnant found behind alarm 9. "stenciled look"

9. "stenciled look"The next pattern has been dubbed a “stenciled look.” The two colors are simply rendered in a post-medieval style, but the vertical repeat is very long—55". This wallpaper was almost certainly created with block prints, and therefore expensive. This looming pattern decorated the wide third-floor hallways outside of the guest rooms. Incidentally, the pattern as rendered here is askew, due to the preserved strip of wallpaper twisting in mid-air.

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall

10. Anaglypta-type in service hall 11. Lincrusta-type, service hall

11. Lincrusta-type, service hallNeither of the manufacturers of the service-hall papers are known. Both the Anaglypta-type (above the dado) and the Lincrusta-type (below the dado) were hung throughout the three floors of the hallway, mute witnesses to the hustle and bustle of household chores. With its spear and shaft motifs the Lincrusta-type presents a somewhat military aspect, albeit the beaded molding and rigid fluting hint at a Classic Revival effect. Both Lincrusta (from 1877) and Anaglypta (from 1887) were English patented products, though there was an American licensee for Lincrusta—Beck—who ran a Connecticut factory.

“Lincrusta-Walton” is often encountered in advertising of the period. Lincrusta was developed by Frederick Walton, inventor of linoleum, while Anaglypta was invented and patented by Thomas Palmer, an employee of Walton. The distinction between the types is that Lincrusta is solid, being made from linseed oil, cork, and other materials which were forced under pressure and great heat into molds. Anaglypta, on the other hand, was hollow, and made from pulp. Thus Anaglypta was cheaper and often used overhead. With a few coats of paint, the Anaglypta types could stand up to regular wear and tear.

12. varnished tile

12. varnished tileThe final paper under consideration is a varnished tile wallpaper which still hangs in an upper-story bathroom. The Decorator and Furnisher reviewed the offerings of Nevius and Haviland on p. 223 of the September, 1893 issue: "That branch of their sanitary grade known as tile patterns contain some new and rarely beautiful designs. There are tile effects with Empire patterns and blue and white, green and white, soft red and white, and other combination, all washable and sanitary, and suitable for halls, kitchens and bathrooms. These goods are artistic, durable and cheap...."

The hygienic aspect of sanitary papers was hugely important to a late-Victorian audience. The pitch for varnished tile papers above combines this virtue with others: artistic, “rarely beautiful,” durable, and yet, for all that...cheap!—suggesting that low cost was a high value for producers and consumers alike. The varnished tile paper at Ventfort Hall, with its several colors, is a step up from the description in the magazine, but not by much. As we shall see, varnished tiles, like most wallpapers, came in a variety of grades, some of which found their way into other large estates in the Berkshire hills.

=====

footnotes:

[1] Gilder and Jackson, Houses of the Berkshires, 1870-1930: The Architecture of Leisure, 2011, p. 132. Some of the wealth which created Ventfort Hall was inherited by Sarah from her father, Junius Spencer Morgan, who was killed in a freak carriage accident in 1890. The Ventfort Hall complex included six greenhouses on 26 acres. The house had 15 bedrooms, 13 bathrooms, 17 fireplaces, billiard room, bowling alley, elevator, burglar alarms, and central heating.

For more about Ventfort Hall:

http://gildedage.org/history/

Before and after photos are at John Foreman's blog site:

http://bigoldhouses.blogspot.com/2012...

[2] The Decorator and Furnisher, July, 1893, p. 147.

=====

captions:

1. masthead, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine

2 - 4. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

5. cover, The Decorator and Furnisher magazine.

6 - 8. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

9. © WallpaperScholar.Com

10 - 12. © 2015 Ventfort Hall Association, Inc.

Published on July 23, 2015 22:46

September 5, 2014

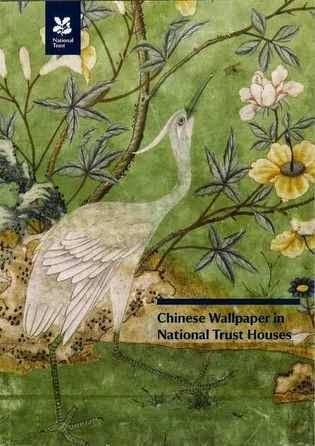

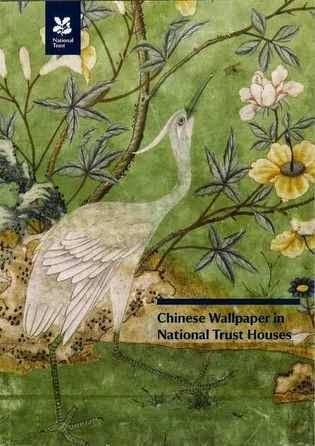

REVIEW: Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses

by Robert M. Kelly

link to buy "Chinese Wallpaper": (cost of the book is about £10, or $16.33)

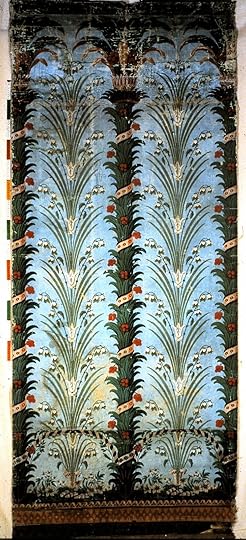

In 1988, paper conservator Catherine Rickman wrote that "there is no information to be had in China about the watercolour paintings, albums and lengths of handpainted paper exported in their thousands from the country over the last two centuries. To find out how such artifacts were made we must study the paintings themselves....." Twenty-five years later this remains largely true, but what enormous strides have been made by the National Trust and the cadre of devoted paper conservators in England and other Western European countries through their periodic work on these marvels of decorative design. This in-the-trenches practice has now been supplemented by a catalog, "Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses," which gives great detail for each of the 45 some-odd Chinese wallpapers that beautify the walls of homes belonging to the Trust.

In 1988, paper conservator Catherine Rickman wrote that "there is no information to be had in China about the watercolour paintings, albums and lengths of handpainted paper exported in their thousands from the country over the last two centuries. To find out how such artifacts were made we must study the paintings themselves....." Twenty-five years later this remains largely true, but what enormous strides have been made by the National Trust and the cadre of devoted paper conservators in England and other Western European countries through their periodic work on these marvels of decorative design. This in-the-trenches practice has now been supplemented by a catalog, "Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses," which gives great detail for each of the 45 some-odd Chinese wallpapers that beautify the walls of homes belonging to the Trust.

Distinctions are made from the beginning between so-called Indian pictures (generally small) and wallpaper proper (generally large). References to Chinese pictures at Versailles in the late 1660s and at Whitehall Palace in 1693 establish that oriental wallpaper was an influence long before the tax of 1712 and thus helps to explain the ads of tradesmen like George Minnikin (1680), and Edward Butling (1690), who traded in both Chinese wares and English chinoiserie adapted from them.

The authors report that one art authority (John Winter) found that shimmering grounds not unusually found in Chinese fine art pictures. This prompts speculation that shiny grounds for wallpaper may have been specially made for the West. The catalog is strong in technical details like these. The text is so dense that it even notes whether "the paper was trimmed", or not, but this brings up a point, about the perceived differences between pictures, which arguably remained art objects in the home, as opposed to wallpaper, which submitted more easily to the demands of the architectural environment. It's helpful to know that "drops" in this text means "strips." It's good that there are so many qualifications of the description "hand painted" which, although not wrong, has sometimes left a false impression. Far Eastern artisans turned naturally to stencils and block printed outlines to speed the work, where possible.

The catalog has scoured the history of each house, family, and sometimes even the circumstances of the installation. Whether it was framed by fillets or turned corners to explode away the very architecture of the room, the Chinese style owned a power which repetitive Western design could not match. There is much here about the decorative traditions of China as well.

In this connection the contributions of Anna Wu, PhD candidate, to the catalog cannot be overstated. She brought Chinese books, research and historic sites to the attention of the writing team (Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush and Helen Clifford). To cite one example, the decorative schemes in the restored Juanqinzhai (Studio of Exhaustion from Diligent Service). This curiously-named retirement lodge of an emperor is awash in silk hangings painted with tromp l'oeil scenery and offers "...a high-end, customized parallel to the wallpaper produced for export to the West."

Although non-Trust properties are not scrutinized, they are not ignored. In addition to the 45 catalog entries, 125 "other" installations are included in the fine map of locations coded by era, so that in total 170 of these Chinese wallpapers are documented. The bibliography is sparkling and includes the most up-to-date (Peck's "Interwoven Globe" from last year) as well as an assortment of fairly recent titles that will be fresh to most.

Catalog # 29 (a c. 1750 firescreen at Osterly Park) shows the age of that quaint tradition. In retrospect it is astonishing that most of these catalog entries relate to installations before the American Revolution and the founding of the American trade. Yet what could be more "early American" than a blockprinted flowerpot in your fireplace for the summer?

We Americans badly need this new information to be folded into what is known about Chinese scenics here. The best treatment remains that of Carl Crossman's Chapter 15: "Decorative Painted Wallpapers to 1850" in his "Decorative Arts of the China Trade" (1991). Our two older books, McClelland and Sanborn, have pictures of Chinese wallpaper. We must not forget that many Chinese scenics formerly in English country houses were auctioned off to a new home in the US, the most prominent of which may be the former Ashburnham Place wallpaper now at Blair House, the president's guest house.

Even when little wallpaper remains, as at Osterly Park, the scent of tea and perfumes of the exotic East linger in the air. This catalogue supplies many details which bring the past to life, even if the remnants are no more than "various wallpapers of unknown types", to quote a contemporary source. A particular effort is made to untangle and understand the identification of Chinese wallpaper with femininity and sociability. It seems to have been no accident that most of the known locations were dressing rooms, bedrooms, and drawing rooms.

Who were the patrons who made this all possible? The homeowners turn out to be various MP's, landed gentry, and (in a later age) heirs to marmalade-manufacturing fortunes: in other words, those who possessed the patrimony, the tall and large rooms, the resources, and the nerve to order up such exotic wall treatments and live with them. That American rooms tended to be squat, and that our decorative traditions tended to be republican and democratic rather than aristocratic, helps to explain why Chinese scenics are practically unheard of in our nation's early history.

link to buy "Chinese Wallpaper"

link to buy "Chinese Wallpaper": (cost of the book is about £10, or $16.33)

In 1988, paper conservator Catherine Rickman wrote that "there is no information to be had in China about the watercolour paintings, albums and lengths of handpainted paper exported in their thousands from the country over the last two centuries. To find out how such artifacts were made we must study the paintings themselves....." Twenty-five years later this remains largely true, but what enormous strides have been made by the National Trust and the cadre of devoted paper conservators in England and other Western European countries through their periodic work on these marvels of decorative design. This in-the-trenches practice has now been supplemented by a catalog, "Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses," which gives great detail for each of the 45 some-odd Chinese wallpapers that beautify the walls of homes belonging to the Trust.

In 1988, paper conservator Catherine Rickman wrote that "there is no information to be had in China about the watercolour paintings, albums and lengths of handpainted paper exported in their thousands from the country over the last two centuries. To find out how such artifacts were made we must study the paintings themselves....." Twenty-five years later this remains largely true, but what enormous strides have been made by the National Trust and the cadre of devoted paper conservators in England and other Western European countries through their periodic work on these marvels of decorative design. This in-the-trenches practice has now been supplemented by a catalog, "Chinese Wallpaper in National Trust Houses," which gives great detail for each of the 45 some-odd Chinese wallpapers that beautify the walls of homes belonging to the Trust.Distinctions are made from the beginning between so-called Indian pictures (generally small) and wallpaper proper (generally large). References to Chinese pictures at Versailles in the late 1660s and at Whitehall Palace in 1693 establish that oriental wallpaper was an influence long before the tax of 1712 and thus helps to explain the ads of tradesmen like George Minnikin (1680), and Edward Butling (1690), who traded in both Chinese wares and English chinoiserie adapted from them.

The authors report that one art authority (John Winter) found that shimmering grounds not unusually found in Chinese fine art pictures. This prompts speculation that shiny grounds for wallpaper may have been specially made for the West. The catalog is strong in technical details like these. The text is so dense that it even notes whether "the paper was trimmed", or not, but this brings up a point, about the perceived differences between pictures, which arguably remained art objects in the home, as opposed to wallpaper, which submitted more easily to the demands of the architectural environment. It's helpful to know that "drops" in this text means "strips." It's good that there are so many qualifications of the description "hand painted" which, although not wrong, has sometimes left a false impression. Far Eastern artisans turned naturally to stencils and block printed outlines to speed the work, where possible.

The catalog has scoured the history of each house, family, and sometimes even the circumstances of the installation. Whether it was framed by fillets or turned corners to explode away the very architecture of the room, the Chinese style owned a power which repetitive Western design could not match. There is much here about the decorative traditions of China as well.

In this connection the contributions of Anna Wu, PhD candidate, to the catalog cannot be overstated. She brought Chinese books, research and historic sites to the attention of the writing team (Emile de Bruijn, Andrew Bush and Helen Clifford). To cite one example, the decorative schemes in the restored Juanqinzhai (Studio of Exhaustion from Diligent Service). This curiously-named retirement lodge of an emperor is awash in silk hangings painted with tromp l'oeil scenery and offers "...a high-end, customized parallel to the wallpaper produced for export to the West."

Although non-Trust properties are not scrutinized, they are not ignored. In addition to the 45 catalog entries, 125 "other" installations are included in the fine map of locations coded by era, so that in total 170 of these Chinese wallpapers are documented. The bibliography is sparkling and includes the most up-to-date (Peck's "Interwoven Globe" from last year) as well as an assortment of fairly recent titles that will be fresh to most.

Catalog # 29 (a c. 1750 firescreen at Osterly Park) shows the age of that quaint tradition. In retrospect it is astonishing that most of these catalog entries relate to installations before the American Revolution and the founding of the American trade. Yet what could be more "early American" than a blockprinted flowerpot in your fireplace for the summer?

We Americans badly need this new information to be folded into what is known about Chinese scenics here. The best treatment remains that of Carl Crossman's Chapter 15: "Decorative Painted Wallpapers to 1850" in his "Decorative Arts of the China Trade" (1991). Our two older books, McClelland and Sanborn, have pictures of Chinese wallpaper. We must not forget that many Chinese scenics formerly in English country houses were auctioned off to a new home in the US, the most prominent of which may be the former Ashburnham Place wallpaper now at Blair House, the president's guest house.

Even when little wallpaper remains, as at Osterly Park, the scent of tea and perfumes of the exotic East linger in the air. This catalogue supplies many details which bring the past to life, even if the remnants are no more than "various wallpapers of unknown types", to quote a contemporary source. A particular effort is made to untangle and understand the identification of Chinese wallpaper with femininity and sociability. It seems to have been no accident that most of the known locations were dressing rooms, bedrooms, and drawing rooms.

Who were the patrons who made this all possible? The homeowners turn out to be various MP's, landed gentry, and (in a later age) heirs to marmalade-manufacturing fortunes: in other words, those who possessed the patrimony, the tall and large rooms, the resources, and the nerve to order up such exotic wall treatments and live with them. That American rooms tended to be squat, and that our decorative traditions tended to be republican and democratic rather than aristocratic, helps to explain why Chinese scenics are practically unheard of in our nation's early history.

link to buy "Chinese Wallpaper"

Published on September 05, 2014 21:54

August 28, 2014

In Memoriam: Don Carpentier, Master of the "Useful Arts"

Don Carpentier (September 22, 1951 - August 26, 2014)

Donald G. Carpentier, 62, died Tuesday morning at his home in Eastfield Village near Nassau, NY. He had been battling ALS for the past three years, and lost his voice about a year ago. He kept communicating by writing notes on a pad and continually posted new discoveries via his Facebook account. He was active in workshops at the Village until two days before his death.

I was fortunate to have been one of the huge number who attended classes at Eastfield. He was passionate about wallpaper. Then again, the list of early American crafts he was passionate about, and adept at, would fill a small book. His contributions to the field of pottery are legendary. Somehow, describing Eastfield's agenda as "education," "classes," and "historic preservation" sounds wrong. These words, while accurate as far as they go, fail to capture Don's vision, which he fully realized, much to our enrichment and his delight. He was perhaps the most insatiably curious man I ever met. He did not so much study history as live it, appreciate it, and share it. No detail was too small, and Don was always racing ahead to the next detail. It seemed that for him "history" was synonymous with "discovery."

Though he became internationally known for his breadth of knowledge, Don lived most of his life within a 50-mile radius of Albany, New York. Remarkably, most all of the buildings in the Village were within that same 50-mile orbit. The family moved from Knoxville, Tenessee, where Don was born, to New York in 1954, settling near Nassau in 1966. He began collecting in his early teens. According to the Eastfield Village website, after building up a substantial collection of medicine bottles, he constructed "...storage space for them out of old buildings he found in the fields" — a portentous development.

As a young adult, after studying civil engineering at Hudson Valley Community College and earning a bachelor's degree in historic preservation from Empire State College in Saratoga Springs, he followed a personal path toward professional growth. He began his life project in 1971 after inheriting 14 acres of land — the former east field of his father's farm — in rural Nassau. He was soon acquiring and moving 18th and 19th century buildings onto the land, board by board.

Over many years, a fair copy of an authentic 19th century village materialized. It includes a church, tavern, blacksmith's shop, tin shop, woodshop, doctor's office, shoe shop, pond, general store, Dutch barn, print shop, several residences, and assorted sheds and outhouses. The outhouses are not decorative. Nor have electricity, cable TV or central heating been installed at the Village proper. Participants in the sessions, which range from two days to a week, are informed that they can stay for free at the Village. There is only one requirement: "...each person choosing to stay at the tavern must supply 10 ten-inch white candles…" Eastfield Village is a place to study Americana, like Colonial Williamsburg or Sturbridge Village, but unlike any other place, workshop participants can sleep on rope beds, cook their own food, and haul their own water.

In effect, Don's collection of buildings became a laboratory of early American culture. The Early American Trades and Historic Preservation Workshops are now in their 38th year. The integrity of the buildings, buttressed by Don's burgeoning knowledge about all sorts of undervalued trades and crafts, allowed participants total immersion — a way to handle, use, and learn about hundreds of architectural elements, tools, and typical artifacts of the late 18th and early 19th century. While Don was an excellent teacher, his open-minded attitude and enthusiasm for learning may have been more important. He was respectful toward the collective knowledge of his adult students. At Eastfield, people learned as much from each other and their own experience as from the putative instructors.

The wallpaper workshops at Eastfield in the summers of 1995 and 1996 were seminal events and were led by Bernard Jacqué (Musée du Papier Peint), Treve Rosoman (English Heritage), Allyson McDermott (British paper conservator), Richard Nylander, Joanne Warner, Ed Polk Douglas, Matt Mosca, Margaret Pritchard, and Chris Ohrstrom. The Eastfield wallpaper workshops spurred the resumption of block printing in the United States after a hiatus of close to 50 years. At the conclusion of the workshops the reproduction 19th-century block printing press created by Eastfield's master carpenters went to the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown, New York for several years before ending up as the first press for Adelphi Paper Hangings, now located in nearby Sharon Springs. Adelphi has now supplied block printed wallpaper for two rooms in the White House and for countless more historic homes.

Many other fields — among them tinsmithing, coopering, typesetting, painting, blacksmithing, masonry, and textiles — have been enhanced by the workshops at Eastfield and by the dedication of its genius, Don Carpentier, sometimes styled the Squire of Eastfield.

Survivors include his former wife, Denise, his husband, Scott Penpraze and stepson Bryce; daughter, Hannah Carpentier, and son, Jared Carpentier; sisters, Linda (and Anthony) Covert and Ellen (and Brian) Cypher, and brother, Jim (and Caroline) Carpentier. Donations in Don's memory may be made to the ALS Association, P.O. Box 6051 Albert Lea, MN 56007, or at www.alsa.org. A private celebration of life will be held for family and close friends. Those who wish information about attending are invited to send a private message to the Historic Eastfield foundation using this URL (the link for messages is in the upper righthand corner of the page):

https://www.facebook.com/HistoricEastfieldFoundation

The Historic Eastfield Foundation, an educational non-profit, was established within the last 10 years or so. It would be fitting indeed if the Foundation can succeed in carrying on his legacy.

Tributes to Don Carpentier:

http://andrewbaseman.com/blog/?p=9242

http://www.crockerfarm.com/blog/2014/08/don-carpentier-1951-2014/

The Facebook page of the Early American Industries Association had been sharing Don's album, and has put up this notice: "The life and accomplishments of Don Carpentier. This album is now dedicated to his memory and a tribute to his craftsmanship and willingness to share with others."

https://www.facebook.com/don.carpentier.7/media_set?set=a.213567902160210.1073741831.100005210049769&type=1

Donald G. Carpentier, 62, died Tuesday morning at his home in Eastfield Village near Nassau, NY. He had been battling ALS for the past three years, and lost his voice about a year ago. He kept communicating by writing notes on a pad and continually posted new discoveries via his Facebook account. He was active in workshops at the Village until two days before his death.

I was fortunate to have been one of the huge number who attended classes at Eastfield. He was passionate about wallpaper. Then again, the list of early American crafts he was passionate about, and adept at, would fill a small book. His contributions to the field of pottery are legendary. Somehow, describing Eastfield's agenda as "education," "classes," and "historic preservation" sounds wrong. These words, while accurate as far as they go, fail to capture Don's vision, which he fully realized, much to our enrichment and his delight. He was perhaps the most insatiably curious man I ever met. He did not so much study history as live it, appreciate it, and share it. No detail was too small, and Don was always racing ahead to the next detail. It seemed that for him "history" was synonymous with "discovery."

Though he became internationally known for his breadth of knowledge, Don lived most of his life within a 50-mile radius of Albany, New York. Remarkably, most all of the buildings in the Village were within that same 50-mile orbit. The family moved from Knoxville, Tenessee, where Don was born, to New York in 1954, settling near Nassau in 1966. He began collecting in his early teens. According to the Eastfield Village website, after building up a substantial collection of medicine bottles, he constructed "...storage space for them out of old buildings he found in the fields" — a portentous development.

As a young adult, after studying civil engineering at Hudson Valley Community College and earning a bachelor's degree in historic preservation from Empire State College in Saratoga Springs, he followed a personal path toward professional growth. He began his life project in 1971 after inheriting 14 acres of land — the former east field of his father's farm — in rural Nassau. He was soon acquiring and moving 18th and 19th century buildings onto the land, board by board.

Over many years, a fair copy of an authentic 19th century village materialized. It includes a church, tavern, blacksmith's shop, tin shop, woodshop, doctor's office, shoe shop, pond, general store, Dutch barn, print shop, several residences, and assorted sheds and outhouses. The outhouses are not decorative. Nor have electricity, cable TV or central heating been installed at the Village proper. Participants in the sessions, which range from two days to a week, are informed that they can stay for free at the Village. There is only one requirement: "...each person choosing to stay at the tavern must supply 10 ten-inch white candles…" Eastfield Village is a place to study Americana, like Colonial Williamsburg or Sturbridge Village, but unlike any other place, workshop participants can sleep on rope beds, cook their own food, and haul their own water.

In effect, Don's collection of buildings became a laboratory of early American culture. The Early American Trades and Historic Preservation Workshops are now in their 38th year. The integrity of the buildings, buttressed by Don's burgeoning knowledge about all sorts of undervalued trades and crafts, allowed participants total immersion — a way to handle, use, and learn about hundreds of architectural elements, tools, and typical artifacts of the late 18th and early 19th century. While Don was an excellent teacher, his open-minded attitude and enthusiasm for learning may have been more important. He was respectful toward the collective knowledge of his adult students. At Eastfield, people learned as much from each other and their own experience as from the putative instructors.

The wallpaper workshops at Eastfield in the summers of 1995 and 1996 were seminal events and were led by Bernard Jacqué (Musée du Papier Peint), Treve Rosoman (English Heritage), Allyson McDermott (British paper conservator), Richard Nylander, Joanne Warner, Ed Polk Douglas, Matt Mosca, Margaret Pritchard, and Chris Ohrstrom. The Eastfield wallpaper workshops spurred the resumption of block printing in the United States after a hiatus of close to 50 years. At the conclusion of the workshops the reproduction 19th-century block printing press created by Eastfield's master carpenters went to the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown, New York for several years before ending up as the first press for Adelphi Paper Hangings, now located in nearby Sharon Springs. Adelphi has now supplied block printed wallpaper for two rooms in the White House and for countless more historic homes.

Many other fields — among them tinsmithing, coopering, typesetting, painting, blacksmithing, masonry, and textiles — have been enhanced by the workshops at Eastfield and by the dedication of its genius, Don Carpentier, sometimes styled the Squire of Eastfield.

Survivors include his former wife, Denise, his husband, Scott Penpraze and stepson Bryce; daughter, Hannah Carpentier, and son, Jared Carpentier; sisters, Linda (and Anthony) Covert and Ellen (and Brian) Cypher, and brother, Jim (and Caroline) Carpentier. Donations in Don's memory may be made to the ALS Association, P.O. Box 6051 Albert Lea, MN 56007, or at www.alsa.org. A private celebration of life will be held for family and close friends. Those who wish information about attending are invited to send a private message to the Historic Eastfield foundation using this URL (the link for messages is in the upper righthand corner of the page):

https://www.facebook.com/HistoricEastfieldFoundation

The Historic Eastfield Foundation, an educational non-profit, was established within the last 10 years or so. It would be fitting indeed if the Foundation can succeed in carrying on his legacy.

Tributes to Don Carpentier:

http://andrewbaseman.com/blog/?p=9242