Robert M. Kelly's Blog, page 2

October 28, 2019

About Jacqué's thesis and "the WALLPAPER"

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

"the WALLPAPER" is founded on an assumption: that the linchpin to an all-around better understanding of historical wallpaper, in all countries, is “Manufacture Au Mur," hereinafter "MauM." I have translated three parts of MauM (hopefully without wrecking them beyond repair) and those links are below.

"the WALLPAPER" newsletter, on the other hand, is essentially a commentary, in monthly installments, on the thesis, for at least the first year of publication. You may subscribe by sending request to thewallpaper@roadrunner.com

This commentary is my own work and consists of adapting the lessons of the thesis to the American situation and to present-day wallpaper scholarship. Beyond any one detail or lesson, the focus of MauM is critically important. MauM is the first extended attempt to view wallpaper not as decorative art or applied art or as a minor art of any kind, but as material culture.

In other words, MauM dares to ask the question: outside of style, why is wallpaper important?

Granted, there have been many books published about wallpaper over the last 20 or 30 years (not any about American wallpaper, mind you) but books published about wallpaper nonetheless. But few of these wallpaper books break new ground. And fewer still are written in English.

Instead, the most interesting writing has come from people with names like Velut, Koldeweij, Cerman, and Wailliez - the Europeans. As for major journal articles published in the US over the last twenty years, to the best of my knowledge there have been precisely three, and two were written by Bernard Jacqué. This only underscores that Jacqué is the most prolific writer about wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age. So that the volume as well as the quality of Jacqué’s writing is a factor in putting his thesis at the forefront of the agenda of 'the WALLPAPER.'

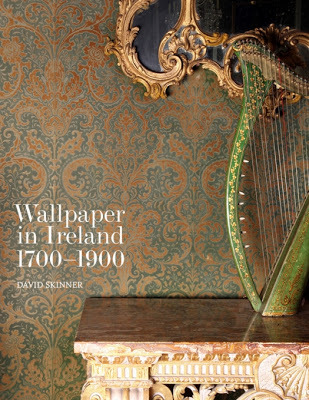

After Jacqué’s thesis I judge the second most significant English-language publication about wallpaper over the last 17 years as David Skinner's book about Irish wallpaper. Skinner took Catherine Lynn's approach. His broadly-based archival research searched well beyond the scant visual evidence to find the social, economic, and personal stories that needed telling. Next most important publication might arguably be the catalog about Chinese wallpapers in National Trust houses authored by Andrew Bush, Emile de Bruijn, and Helen Clifford.

For the rest in the Anglo/American world, I note four other theses as worthy of study, all from the UK, and all freely available to browse on the internet: those of Clare Taylor, Phillippa Mapes, Wendy Andrews, and Anna Wu.

Taylor: ‘Figured Paper For Hanging Rooms’

http://oro.open.ac.uk/60714/1/518280_Vol1.pdf

Mapes: The English Wallpaper Trade, 1750 - 1830

https://core.ac.uk/display/76987513

Andrews: The Cowtan Order Books, 1824-1938

https://www.martincentre.arct.cam.ac.uk/downloads/wd-andrews-phd-thesis-2017/view

Wu: Chinese Wallpaper, Global Histories, and Material Culture

https://tinyurl.com/wlywor5

Some final words about the thesis. In compiling this massive work, Jacqué kept his nose to the grindstone.

He did, however, allow himself one personal memory. It's about a boy's visit to the Wallpaper Musum in Rixheim. This youngster took in the panoramic views of 'Scenic America' with great excitement. He knew this one! A recent reissue had been hung in his grandmother's house. Everyone was enjoying the moment until the boy began reviewing the troops near West Point. Something caught his attention. Much to his disappointment, THESE soldiers in the museum sported brilliant red plumes; whereas the same soldiers back at grandma's house had none! Jacqué comments: “...a printer had failed in his task - and only a child's eye's could see it."

I thought of this boy and this anecdote when reviewing Zuber's earliest successes. For it is a fact that this young visitor to the Wallpaper Museum was walking on the same wooden floors where children not much older or younger than he had toiled throughout much of the nineteenth century.

In a typical year, the Zuber factory employed 200 workers. At least a quarter (50) were between the ages of 8 and 12. Indeed, during the 1790s the proportion of child labor was double that - half of the entire work force. Jacqué repeatedly brings home that the low price of labor in the quasi-feudal village of Rixheim, a dependency of the independent city of Mulhouse, was a significant factor. Labor cost less than in Paris, Lyon, and other French cities.

And this is just one example of the value of the thesis. We may come away with the same conclusion: that the French dominated luxury wallpaper-printing in the long nineteenth century, and therefore Malaine, the artistic director as well as other artisans deserved the gold medals handed out at international exhibitions. But thanks to Jacqué's unblinking assessment we know that Zuber’s provision of beautiful ornaments for parlor walls also depended, to a significant extent, on the willing hearts and tiny hands of children.

_____________________

Three selections from Jacqué's thesis are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

"the WALLPAPER" is founded on an assumption: that the linchpin to an all-around better understanding of historical wallpaper, in all countries, is “Manufacture Au Mur," hereinafter "MauM." I have translated three parts of MauM (hopefully without wrecking them beyond repair) and those links are below.

"the WALLPAPER" newsletter, on the other hand, is essentially a commentary, in monthly installments, on the thesis, for at least the first year of publication. You may subscribe by sending request to thewallpaper@roadrunner.com

This commentary is my own work and consists of adapting the lessons of the thesis to the American situation and to present-day wallpaper scholarship. Beyond any one detail or lesson, the focus of MauM is critically important. MauM is the first extended attempt to view wallpaper not as decorative art or applied art or as a minor art of any kind, but as material culture.

In other words, MauM dares to ask the question: outside of style, why is wallpaper important?

Granted, there have been many books published about wallpaper over the last 20 or 30 years (not any about American wallpaper, mind you) but books published about wallpaper nonetheless. But few of these wallpaper books break new ground. And fewer still are written in English.

Instead, the most interesting writing has come from people with names like Velut, Koldeweij, Cerman, and Wailliez - the Europeans. As for major journal articles published in the US over the last twenty years, to the best of my knowledge there have been precisely three, and two were written by Bernard Jacqué. This only underscores that Jacqué is the most prolific writer about wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age. So that the volume as well as the quality of Jacqué’s writing is a factor in putting his thesis at the forefront of the agenda of 'the WALLPAPER.'

After Jacqué’s thesis I judge the second most significant English-language publication about wallpaper over the last 17 years as David Skinner's book about Irish wallpaper. Skinner took Catherine Lynn's approach. His broadly-based archival research searched well beyond the scant visual evidence to find the social, economic, and personal stories that needed telling. Next most important publication might arguably be the catalog about Chinese wallpapers in National Trust houses authored by Andrew Bush, Emile de Bruijn, and Helen Clifford.

For the rest in the Anglo/American world, I note four other theses as worthy of study, all from the UK, and all freely available to browse on the internet: those of Clare Taylor, Phillippa Mapes, Wendy Andrews, and Anna Wu.

Taylor: ‘Figured Paper For Hanging Rooms’

http://oro.open.ac.uk/60714/1/518280_Vol1.pdf

Mapes: The English Wallpaper Trade, 1750 - 1830

https://core.ac.uk/display/76987513

Andrews: The Cowtan Order Books, 1824-1938

https://www.martincentre.arct.cam.ac.uk/downloads/wd-andrews-phd-thesis-2017/view

Wu: Chinese Wallpaper, Global Histories, and Material Culture

https://tinyurl.com/wlywor5

Some final words about the thesis. In compiling this massive work, Jacqué kept his nose to the grindstone.

He did, however, allow himself one personal memory. It's about a boy's visit to the Wallpaper Musum in Rixheim. This youngster took in the panoramic views of 'Scenic America' with great excitement. He knew this one! A recent reissue had been hung in his grandmother's house. Everyone was enjoying the moment until the boy began reviewing the troops near West Point. Something caught his attention. Much to his disappointment, THESE soldiers in the museum sported brilliant red plumes; whereas the same soldiers back at grandma's house had none! Jacqué comments: “...a printer had failed in his task - and only a child's eye's could see it."

I thought of this boy and this anecdote when reviewing Zuber's earliest successes. For it is a fact that this young visitor to the Wallpaper Museum was walking on the same wooden floors where children not much older or younger than he had toiled throughout much of the nineteenth century.

In a typical year, the Zuber factory employed 200 workers. At least a quarter (50) were between the ages of 8 and 12. Indeed, during the 1790s the proportion of child labor was double that - half of the entire work force. Jacqué repeatedly brings home that the low price of labor in the quasi-feudal village of Rixheim, a dependency of the independent city of Mulhouse, was a significant factor. Labor cost less than in Paris, Lyon, and other French cities.

And this is just one example of the value of the thesis. We may come away with the same conclusion: that the French dominated luxury wallpaper-printing in the long nineteenth century, and therefore Malaine, the artistic director as well as other artisans deserved the gold medals handed out at international exhibitions. But thanks to Jacqué's unblinking assessment we know that Zuber’s provision of beautiful ornaments for parlor walls also depended, to a significant extent, on the willing hearts and tiny hands of children.

_____________________

Three selections from Jacqué's thesis are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

Published on October 28, 2019 13:06

Introduction To: 'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections from Jacqué's thesis are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of décors, tableaux, and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections from Jacqué's thesis are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of décors, tableaux, and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

Published on October 28, 2019 13:06

Introduction To: 'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'...

Introduction To: 'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

Published on October 28, 2019 13:06

'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'In 2003 Dr. Berna...

'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

In 2003 Dr. Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, the title of which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2,300 footnotes) and important. Trust me.

Jacqué was curator at the Museé du Papier Peint from its inception in 1981 until his retirement in 2009. He is the most prolific writer about historical wallpaper of our age. Indeed, of any age, to the best of my knowledge.

His legacy also consists in a variety of exhibitions, conferences, and catalogues which he conceived, led, or contributed to. Fortuitously, Jacqué wound up directing a museum which was practically married to the Zuber wallpaper company. Museum and factory inhabit the same piece of property, a quasi-feudal estate in Rixheim now owned by the local government.

This gave Jacqué everyday access to the wallpaper samples, inventories, marketing materials, and production records of the Zuber company, making up, in its entirety, the most complete record of wallpaper in existence. It is fitting that the aims of the thesis capping his curatorial career are ambitious and comprehensive:

ABSTRACT

In the period 1770-1914 wallpaper became the premier decoration in Western interiors. Until recently, it has been studied in terms of style. Yet we continue to know little about wallpaper as a material object. Here, the full context surrounding wallpaper is under consideration: the manufacturer, the design studio, the workshop, how and to whom it was sold, and how it was hung. Beneath the style of wallpaper are the cultural foundations which give it meaning. During the eighteenth century, wallpaper was a relatively well-documented, elite product. Some questions about its context are answered by the royal archives and the extensive record-keeping of N. Dollfus & Company in Mulhouse. During the nineteenth century the consumption of wallpaper of all types increased with mechanization. This study concentrates on the better-documented products of the Zuber company in Rixheim such as panoramics and décors which were intended for elite markets. Wallpaper, often misinterpreted, is established here as a fundamental element of the culture of the interior at every level of society.

_____________________

Three selections are presented in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

A fourth PDF based closely on the thesis will examine the roles of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers. These high-style French genres from the last half of the 19th century prolonged the scenic era. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

Published on October 28, 2019 13:06

'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'In 2003, after a ...

'Toward A Material History of Wallpaper'

In 2003, after a distinguished career founding and leading the Museum of Wallpaper in Rixheim, Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis at the University of Lyon about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2300 footnotes) and important.

Three selections are presented here in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

I am preparing a fourth PDF based closely on the thesis which examines the role of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers in the late 19th century. These types were a prolongation of the scenic idea. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

In 2003, after a distinguished career founding and leading the Museum of Wallpaper in Rixheim, Bernard Jacqué wrote a thesis at the University of Lyon about wallpaper: ‘De La Manufacture Au Mur: Pour une histoire matérielle du papier peint, 1770-1914’.

The French original can be accessed at:

http://theses.univ-lyon2.fr/documents/lyon2/2003/jacque_b

This thesis, which I have translated "From the Workshop to the Wall - Toward a Material History of Wallpaper" is large (600 pages, 2300 footnotes) and important.

Three selections are presented here in English-language versions (the links lead to a PDF):

1: A Historiography of Wallpaper, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/rzsz-6286

2: Zuber’s ‘Indépendance’ (1853) a hand-painted restatement of ‘Scenic America’ (1835),

http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/jnr1-zv39

3: The Scenic Revival of the 20th Century, http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/e87a-2350

I am preparing a fourth PDF based closely on the thesis which examines the role of "tableaux" and so-called tapestry papers in the late 19th century. These types were a prolongation of the scenic idea. Like the scenics, they were pictorial and often referenced art history in some way.

Published on October 28, 2019 13:06

October 1, 2018

Toward A History of Canadian Wallpaper Use: Mechanization...

Toward A History of Canadian Wallpaper Use: Mechanization 1860-1935

Toward A History of Canadian Wallpaper Use: Mechanization 1860-1935Robert M. Kelly

Abstract

This article examines wallpaper use in Canada from the beginning of cylinder printing in 1860 to 1935. Statistics reveal that the value of wallpaper within Canada grew steadily during this period, before declining precipitously during the 1930s. Canada’s four major factories achieved dominance in their home market by producing low-to-middle grade wallpaper at affordable prices. This paper documents this achievement and explores its significance, centering on a key compilation of primary and secondary sources. From this compilation, costs and patterns of trade are extracted in order to show Canadian development against the backdrop of wallpaper history. Partial comparison to Canada’s chief competitor and trading partner, the United States, is made through analysis of per capita production and consumption figures. This article is grounded in recent scholarship from Europe which suggests that wallpaper can be viewed as an object of use over and above its more familiar role as a minor art-historical artifact.

full article.......https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/25553/29620

Published on October 01, 2018 12:35

July 31, 2017

Review: Wallpaper In Ireland 1700-1900

Review:"Wallpaper In Ireland 1700-1900" by David Skinner, Churchill House Press, 2014

BY ROBERT M. KELLY

A very large number of houses are always changing their tenants — houses of the middling and cheaper classes more particularly — and a ‘fresh paper’ is the usual complement of a new tenant.

(The Irish Builder magazine, 1868)

This account of the customary use of wallpaper in central Dublin reminded me of my parents’ upbringing in Pittsfield, a small industrial city in western Massachusetts. Elaine McConkey and Richard Kelly grew up during the 1930s in large households surrounded by cheap wallpaper. Renting was a way of life. I also grew up in rented quarters surrounded by cheap wallpaper, the second of their ten children. I began Skinner’s book, then, more prepared than most to hear his assessment of the Irish contribution to wallpaper history.

The photos reveal that Skinner had predecessors. For many years Mrs. Leask and John O’Connell had foraged the countryside securing remnants of Irish-stamped wallpaper. Many of the samples shown in the book have since found a home at Fota House (Cork) in the Irish Heritage Trust Collection of Historic Wallpaper.

The provenance of the wallpapers, along with Skinner’s meticulous research, give the book the stamp of authority. English and French wallpapers sold and installed in Ireland are no less scrutinized. The samples come from all strata of society. The firsthand evidence that Skinner has uncovered is often thrilling. It’s one thing to know that the Cowtan company of London furnished Irish estates, and another thing to have found, as he did, penciled inscriptions from Cowtan’s workers on the very walls of Carton and Coollattin.

On the evidence of this book, important paperstaining shops in the United Kingdom were not limited to a few English cities but were common in Ireland, at least leading up to the high-water mark of the mid-nineteenth century. While Skinner's book does not exactly upend the conventional portrait of a dominant English wallpaper culture within the UK, it does confront those assumptions with new evidence. He shows the character of wallpaper production in Ireland and how this production affected that of other countries.

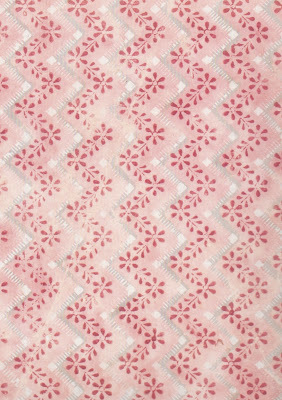

Skinner challenges assumptions that English or Irish wallpaper can be easily sorted into stereotypes. The range of finish was vast. Of course, each nation had areas of specialization, and some genres were quite distinctive. But these exemplars, so visually arresting and therefore so appealing to one’s individual preference, can have a tendency to overshadow the essential sameness of wallpaper in context, when each pattern for sale was simply one choice among many. Within these generalities, there were of course recognizable facts and trends. For example, Skinner all but proves that the “middling and cheaper classes” referred to in the quote from The Irish Builder accounted for most of the consuming in Ireland in the nineteenth century. This seems to have been true in North America as well.

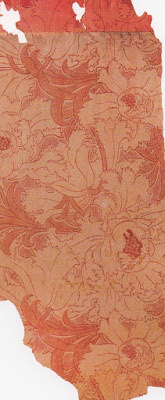

If there was an Irish style, it seems to have been equal parts cheap, harmonious, and staid, judging from these photos. That said, there was also a preference for a significant number of down-market papers of almost punishing vivacity that pose a challenge to our twenty-first century sensibilities. Did people really like these outrageous colors and designs? Apparently, they did. An example of a 'fancy flowered, rainbowed' paper from France sold by James Boswell in the 1830s is shown below (Figure 189).

At the other end of the scale, the book shows agreeably-aged wallpapers draping many a stately home. These now-echoing castles, country homes, and great halls may be stately, but they are nevertheless domiciles, thus validating their inclusion here.

Historical wallpapers have been increasingly integrated into museum collections and thereby saved for posterity, a generally happy result. But, we must remember that this acceptance is no substitute for what has been lost in the separation from the home, namely, an essential linkage: that a particular pattern was chosen by a particular person for a particular room. The acquisition of wallpapers by museums therefore presents risks as well as rewards: a risk that these artifacts might be presented and appreciated as something that they were never intended to be: art. It is encouraging to see that this risk was seemingly anticipated and avoided in the present volume. The wallpapers come from a wide variety of collections, but they are consistently presented in context as subjective choices for the domestic interior.

Chapter Six will probably appeal the most to students of North American history. Here we learn how native producers emerged and sustained themselves within a market defined by foreign rivals; how various grades of wallpaper were brought to market; and who bought them. The marketing story, like the question of style, is not simply national. Many of the economic variables (tariffs, taxes, competition, and contraband) were international in scope, and they mattered absolutely: one or two of these variables could make or break a small producer. None of these aspects are neglected by Skinner.

Many of the nuances of Irish history (for example, that the aristocratic lifestyle all but vanished in Dublin after the Act of Union in 1800) are sure to slip by American readers. Yet this in no way lessens Skinner's achievement. He paints a lively picture against a constantly shifting backdrop as the village and family paperstainers of the eighteenth century gave way to the factories of the nineteenth. Skinner demonstrates that Irish wallpaper was dominant in the home market and available for only a few pence per roll by the mid-1830s. Yet, this was a qualified success.

None of the Irish shops grew to the size of English behemoths such as Heywood, Higginbotham, and Smith. The long-delayed utilization of continuous paper and newly-invented machinery for printing combined to spark proliferation world-wide by around 1850. Ireland certainly saw proliferation, but it was of the hands-on and small scale variety. Indeed, Irish shops can hardly be described as mechanized, since block-printing was almost exclusively employed throughout the nineteenth century. The industry petered out completely by 1880.

Why did mechanization of paper-hangings skip over Ireland? Skinner makes no claims that his book is a sociological text, but he does point out on page 164 that Ireland lost four million people to famine and emigration between 1841 and 1900, becoming thereby the only European nation to lose population in those years. These losses occurred at the very time that mechanization was taking hold elsewhere.

Many wallpaper historians have implied that the rise of machine-printing was swift and that it soon replaced block-printing. Skinner’s book throws some new light on these assumptions. He notes that in 1845 Moses Staunton was dissatisfied with the new English-made machine-prints: “…he found the colours lasted but a few days from being put on the walls… ”. This technological speed bump has been evident (a discussion of the shortcomings of machine-prints was published in the Journal of Design and Manufactures of 1851) yet shortcomings like thin, watery inks and botched registration have not been brought to the surface in secondary sources until now. This new information rounds out our picture of late-nineteenth century shops and helps explain why block-printing continued in English, French, Canadian, and American shops long after machinery had arrived.

Skinner describes the country house Ballinterry as “solid, rambling, and unpretentious”. That might be said as well about Skinner’s text. He provides just enough helpful redundancy. I appreciated this foundation as I struggled to keep up with his brisk gallop through two centuries of decorative history. The photography is exceptional. Figure 112 (showing borders from 1810) practically explodes off the page.

The wooly flock, shiny metallics, pin-dots, and irregularities of the blockprints show the tactile qualities of early wallpaper. The simple but effective designs of the cheap self-grounded papers hint at why they were so popular.

The inclusion of many gorgeous photos of oddball print-room types and art-historical darlings such as the Chinese scenics and the Cupid & Psyché series (from Dufour) threaten to tip the book into coffee-table territory. Yet Skinner includes many previously unpublished details about Hamilton’s Etruscan prints in the print-room section. He also explains how Tischbein adapted them for the wall. We learn why Hamilton and Tischbein were inspired, who carried this trade out, and how tastemakers and householders realized the possibilities.

The 237 color photos are accompanied by just enough context. Captions and photos are precisely placed, a virtue not always found in wallpaper books. Footnotes contain important information.

Skinner dutifully reports on the few French arabesques that are known to have been used in Ireland (many more were advertised) and tidies up some lingering anomalies about the late-eighteenth century Sherringham and Eckhardt factories, both in the London area. His chapter on Edward Duras, who successfully transplanted his paperstaining business from Dublin to Bordeaux, France, is a revelation.

Skinner dutifully reports on the few French arabesques that are known to have been used in Ireland (many more were advertised) and tidies up some lingering anomalies about the late-eighteenth century Sherringham and Eckhardt factories, both in the London area. His chapter on Edward Duras, who successfully transplanted his paperstaining business from Dublin to Bordeaux, France, is a revelation.Skinner sorts out many corners of wallpaper history. For example, it’s well-known that a group of Irish paperstainers emigrated to Liverpool in the early nineteenth century and thrived for the next fifty years. He explains their rise and fall. Much fresh information is provided about James Boswell’s company. Boswell’s designs, his upright business methods (not emulated by all of his competitors) and his impact on the paperstaining culture are on display, which is quite an accomplishment since Boswell’s company had been little more than a footnote. Skinner notes that over a hundred Boswell designs have been deposited in the Office of the Registrar of Designs in Kew, forming what is arguably the most comprehensive body of work for any Irish paperstainer. Nothing like this exists in the United States.

Skinner puts Morris-type papers in context, describing their designs as “organic” and “neo-vernacular”. He shows how Irish manufacturers juggled processes, styles, and regulations to see off competitors, poach patterns, and capture markets.

An art nouveau design on self-grounded paper (Figure 212) proves the point that no design, however avant-garde, was beyond exploitation. It is a cheap machine-print, most likely English. By the time this pattern was printed about 1890 the Irish industry had collapsed.

An art nouveau design on self-grounded paper (Figure 212) proves the point that no design, however avant-garde, was beyond exploitation. It is a cheap machine-print, most likely English. By the time this pattern was printed about 1890 the Irish industry had collapsed.To take on 200 years of decorative history, albeit that of a single product in a single country, is a daunting task. Skinner has succeeded at this project by imaginatively reconstructing and communicating the outlooks of those who were intimately associated with the product — paperstainers, retailers, paperhangers, and consumers. Fulfilling one of his stated goals, he has contributed a sound history of the rise and fall of the Irish paper-hangings industry. But more important, his book will certainly influence future wallpaper studies because of its firm grasp on the historical context within which these wallpaper artifacts must be understood. “Wallpaper In Ireland” teaches us much about the Irish people and Irish craft traditions. But it also shows us that when it comes to wallpaper, no country is an island.

Published on July 31, 2017 20:27

June 2, 2017

Wallpaper In Ireland.....a series

Herewith an examination in serial form of David Skinner's 2014 book

Wallpaper In Ireland 1700 - 1900.

Introduction:

...One of Ireland's lesser-known trades, its history largely forgotten, wallpaper manufacture employed many hundreds of people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when locally-produced papers were sold and used alongside those imported from other countries. Charting the history of wallpaper use by examining surviving examples and the documentary record, this book aims to awaken some echoes of the people who bought wallpaper in Ireland or who spent their lives in making it, and to trace the 'things' which formed the contexts of its production and design…

Paper-staining, as the trade came to be known, took root, flourished and declined in Ireland in an arc of activity spanning the century and a half between the 1720s and the 1870s…In England wallpaper manufacture was developed by well-capitalized companies like the Blue Paper Company, backed by investors with an expansionist outlook on foreign markets, while in Ireland artisanal family businesses, passed on from fathers to sons, operated in an isolated and hermetic economy, training apprentices who, when they became masters, had either to carve out a share of a limited market or emigrate. By the 1830s Dublin was said to have more master wallpaper makers than all of Britain, but only a few of them were doing much more than eking out a living. To a great extent, what differentiates Irish wallpapers from those made in Britain is not so much their design as the circumstances and conditions of their production…

A central aim of the present study is to chart the rise and fall of the Irish paper-stainer, from the artisan workshops which supplied the wealthy elite of Georgian society to the clandestine garrets which sent contraband wallpapers to Victorian Britain...[This book] illustrates the richness and diversity of the styles and patterns which formed the backdrop to domestic lives in Ireland over two centuries...

Introduction:

...One of Ireland's lesser-known trades, its history largely forgotten, wallpaper manufacture employed many hundreds of people in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when locally-produced papers were sold and used alongside those imported from other countries. Charting the history of wallpaper use by examining surviving examples and the documentary record, this book aims to awaken some echoes of the people who bought wallpaper in Ireland or who spent their lives in making it, and to trace the 'things' which formed the contexts of its production and design…

Paper-staining, as the trade came to be known, took root, flourished and declined in Ireland in an arc of activity spanning the century and a half between the 1720s and the 1870s…In England wallpaper manufacture was developed by well-capitalized companies like the Blue Paper Company, backed by investors with an expansionist outlook on foreign markets, while in Ireland artisanal family businesses, passed on from fathers to sons, operated in an isolated and hermetic economy, training apprentices who, when they became masters, had either to carve out a share of a limited market or emigrate. By the 1830s Dublin was said to have more master wallpaper makers than all of Britain, but only a few of them were doing much more than eking out a living. To a great extent, what differentiates Irish wallpapers from those made in Britain is not so much their design as the circumstances and conditions of their production…

A central aim of the present study is to chart the rise and fall of the Irish paper-stainer, from the artisan workshops which supplied the wealthy elite of Georgian society to the clandestine garrets which sent contraband wallpapers to Victorian Britain...[This book] illustrates the richness and diversity of the styles and patterns which formed the backdrop to domestic lives in Ireland over two centuries...

Published on June 02, 2017 12:52

January 30, 2017

All About: The Wallpaper History Review 2015

The Review from 2015 edited by Christine Woods is an overstuffed sandwich of wallpaper.

It contains close to a hundred pages with an astonishing number of excellent color photos (140) and wonderful articles. The Review has been out for some time but news travels slowly in the wallpaper world. It is is based in the UK, only available through print subscription, and North American wallpaper is rarely encountered in its pages. Nevertheless, the content is rich and addicting.

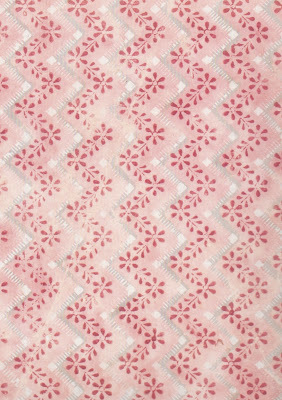

Below, I am summarizing some of the most important articles from this 2015 issue. This first photo is from "Matching 'furnitures’ - Some Mid-18th Century Stencilled Wallpapers” by Andrew Bush. Bush, who works for the National Trust, explains how these simple check and plaid and stripe designs made the jump from textiles to wallpaper, sometimes because someone wanted to do up a single room and have them match (custom work) but also because they were so versatile and could be stocked. Most all of these are on ungrounded paper.

1. 200 Years Of Home Decor, by Linda Imhof

2. The American Taste For English “Regency” Stripes, by Philip Aitkens

3. Challenging Assumptions, by Andrew Bush

4. Regional Versus Metropolitan: The Provincial Wallpaper Trade, by Phillippa Mapes

5. Paul Balin, Master Of Illusion, by Astrid Arnold-Wegener

6. Chinese Wallpaper, A Cultural Chameleon, by Anna Wu

7. Japanese Leather Paper, by Wivine Wailliez

8. A Spanish Odyssey, by Veronique de La Hougue

1. 200 Years Of Home Decor

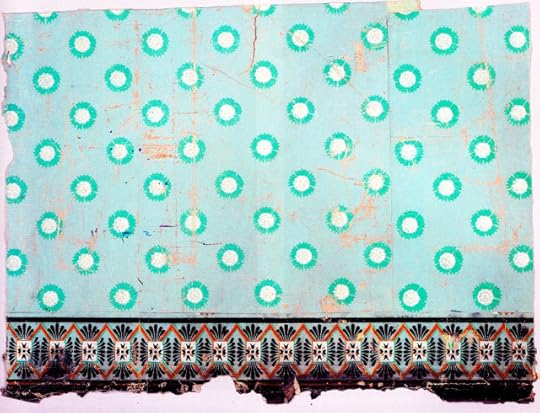

The photo below could be titled “Date Me!” What year do you think it is from? Now bear in mind that this design features a round motif of raspberries in the middle of the circles. The color has faded terribly so that they now appear white…..but they used to be red.

This quiz introduces an interesting project: a regional study of a canton (state) smack in the middle of Switzerland. Two hundred or so wallpapers were catalogued by freelance art historian Linda Imhof. She did this work in conjunction with her MA thesis to obtain her degree. The wallpapers came from 8 buildings in the Swiss canton of Zug. Two dwellings were in Zug (also the name of the chief city of the canton), three were in rural areas, and three were clerical buildings. According to Imhof, wallpaper research is still young in Switzerland; it started in around 1990.

Her questions focussed on: 1. identification of manufacturing technique and dating of each paper; 2. recording where and how the papers were hung in the houses; and 3. comparison of the use of the papers in the three groups of houses.

The stone city houses are old. Somewhat astonishing to this American, one dates from the 16th century and the other from the 17th. A few blockprints from around 1790 were found; in some cases wallpaper sandwiches of up to 5 or 6 layers as well. These latter were from roughly 1880 to 1960, so a wide range of style and materials were evident.

Not surprisingly, most of the wallpapers hung in the rural areas were cheap. Many ungrounded papers were found. One house in particular was a treasure chest and gave up 66 papers, of which only two were blockprints. These three houses in the country were made of wood. They have since been torn down.

The houses for clerics yielded some upscale papers, and in particular the so-called Biedermeier period is well-represented. Most all of these papers were block-printed. Imhof rounds out her paper with sections on “several options for hanging wallpaper”, “reusing wallpaper leftovers”, and “repapering”. Imhoff found that the type of paper, i. e., whether it was composed of earlier rag paper or the later and cheaper pulp machine-made paper, had a decisive impact on the condition of surviving wallpapers.

2. The American Taste For English “Regency” Stripes

This is a marvelous exercise in close visual analysis. It considers the question: “How did American paper stainers and their customers move away from imported English designs as independent taste developed in the USA during the early 19th century?”. This article compares three versions of a design that apparently originated in London in about 1800. It was copied closely (but not completely) by Zechariah Mills of Hartford. The design was then adapted in a simpler version by Mills for a paper that was used to line a trunk (shown in “Wallpaper In America” (1980) by Lynn, p. 114).

Aitkens, an English historic building consultant who has a collection of about 500 18th and 19th century wallpaper fragments (!) corresponded with Richard Nylander of Historic New England who shared his unpublished research into the Cadwell House wallpaper in Connecticut. Aitkens reports that his own collection contains not a single striped pattern and ventures a question: could it be that although English custom favored stripes in the 1770s and 80s (among other types) that English paperstainers began “turning away from stripes for a while during the years around 1800”?

On the other hand, it seems that the USA was not turning away. One can point to the Janes & Bolles (also of Hartford) sample book of 1821-29, which was full of stripes. Although the topic is debatable, Aitkens wonders whether we should be leaning toward emphasizing “late-Regency stripes” in England rather than simply “Regency stripes”.

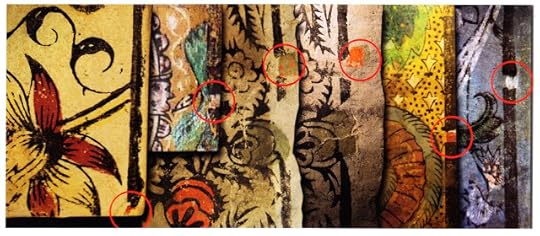

3. Challenging Assumptions

The article centers on a group of six wallpapers covering notebooks dating from 1733-44. The steps in their production: 1. grounding paper; 2. applying opaque stencil designs; 3. applying a block printed outline; 4. applying a transparent colored glaze. All of this was done by utilizing a registration system.

Bush explains that most wallpaper in the UK from the mid-18th century onward had a registration system of pins in the leading corner of a woodblock and/or bars printed alongside the wallpaper pattern. But not these. Although to our eyes these designs might look somewhat primitive compared to what was to follow, nevertheless, the number of individual processes required for these early examples led to the need for a registration system to help with alignment.

Note figure 5 (reproduced here). This photo shows edge details from six sheets of wallpaper, and indicates how the registration system worked. The colored squares within the red circles are a result of color being brushed through cut-outs on both sides of consecutively applied stencils. Essentially, what looks like a “notch” (consisting of a square area) was created when the black outline from the woodblock was applied above and below the registration square.

These wallpapers are from the period of transition from individual decorative sheets with stand-alone patterns (like the domino papers of France and Italy, which have the black rectangle around a design, for instance) to a period when paper was joined and all patterns were expected to provide an endless design in both directions. Bush concludes that “the seamless nature of these later continuous patterns required the development of the pin and bar registration aids, and it seems that the earlier system described above faded into obscurity.”

4. Regional Versus Metropolitan: The Provincial Wallpaper Trade 1750-1830

One of the really fine things that the Wallpaper History Society does is that they have a research grant program. One of the recipients, Ms. Mapes, is a paper conservator and has been looking into the trade history of wallpaper as part of her work toward a doctorate.

In this article, Mapes shows that the wallpaper trade enjoyed a period of expansion in the second half of the 18th and early 19th century as part of the economic boom and rise in population attributed to the Industrial Revolution. This enabled middle class consumers to spend more on newly developed consumer goods like wallpaper. Although the wallpaper trade was primarily based in London, Mapes has found a surprising amount of evidence for the migration of manufacturers to regional locations such as Ipswich, Bath, Bristol, Liverpool, York, and Manchester.

She not only traces the sheer evidence that they existed, but notes the various ways that consumer goods either flowed from the capital into the provinces, or vice versa. The way that pricing worked was complex. Mapes does a good job of sorting it out, for there were advantages to producing wallpaper in a city, and other advantages to being in the country. For example, country locations advertised that they could do custom work right away, as opposed to sending to London to have it done where it might take longer due to distances and complications.

The transportation network was often key. But, it was not that factories needed to be near raw materials, as in other trades. It was the mobility, and population concentrations enabled by the new canals and railroads, and the coastal cities, that were important for these regional factories. Even the Isle of Man had a factory, for their citizens were equally impatient for the latest fashions and were willing to patronize a new paperstainer in town, especially if he was employing London blockprinters, rather than wait for the opportunity to visit London to pay what were perceived as huge markups to decorators and upholders’ shops for the privilege of purchasing the wallpaper.

By the time that heavy machinery arrived into the trade starting in around 1830, these regional centers had grown and were in a position to compete more directly with London, especially since the London paperstaining industry had itself been weakened by a shift in fashionable focus from London to Paris, which had happened in the first few decades of the 19th century.

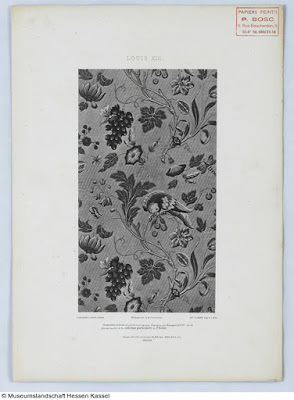

5. Paul Balin, Master Of Illusion

This overview of Paul Balin’s career can be seen as a sort of introduction to the 2016 summer show at the German wallpaper museum in Kassel and even more as a sort of teaser for the gorgeous book that resulted from the exhibition: “Schöner schein : Luxustapeten des Historismus von Paul Balin”.

The book combines the work of a half-dozen wallpaper scholars in telling the story of Paul Balin, a very gifted but somewhat eccentric wallpaper manufacturer who started in the Defosse workshops in 1861 and proceeded to invent and create (along with litigating against and exasperating his competitors) for the next 40 years or so. Of special interest is the “wallpaper affair” in which his litigation threatened to grind the high-end industry to a halt for several years while patent disputes about embossing and finishing machines were resolved, not only in France but in several other countries. Zuber, among other companies, was deeply affected. He seems to have won most of his cases but certainly did not leave many fond memories behind among his competitors. He was an excellent networker and social butterfly and no doubt would have had an iPhone and a well-used Twitter account in our times. His crowning glory was the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna where his productions met with acclaim. Subsequently he was able to finagle his way into state recommendations, honors, and awards. In short, he aspired to be a “thought leader” in the luxury trade and succeeded.

Ms. Arnold-Wegener tells the inside story about how the documentation, some of it discovered quite recently, was gathered, and how the show came together. Of special interest is her explanation of how Balin worked. He was genuinely obsessed with his work, which cannot be understood without the repeated invocation of “historicism” — in other words, the constant quest for finding new processes to carry forward the craft of earlier generations. He was a genuine aesthete but he was nevertheless sometimes accused of a backwards fussiness. It is said that he particularly loathed Art Nouveau as "degenerate art" that he would never engage with or promote.

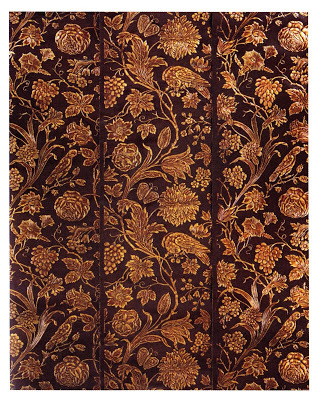

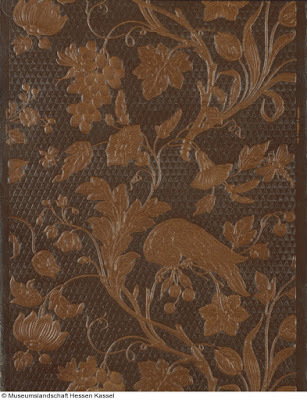

In these photos, we can see how Balin, a master marketer, took a single pattern from a gilt leather panel (the so-called Peacock pattern) and reinterpreted it in a bronze paper; as well as a leather paper; as well as a chintz blockprint. The last one named has brilliant coloring and was produced as "A" and "B" rolls. This was probably necessary because the usual width of the paper rolls (about 18") would hold only about half the horizontal repeat; it is likely that the original embossed gilt leather was fairly wide.

6. Chinese Wallpaper, A Cultural Chameleon

Wu is an academic expert on Chinese wallpaper and has developed good connections to China where she has done some innovative research and also visited certain high-style hotels and private clubs where contemporary Chinese wallpaper is on display.

In this piece she sets out to tell a comprehensive story of how Chinese wallpaper has remained an exotic presence, a highly-polished craft, and yet at the same time a commodity over the last several hundred years, resulting in worldwide popularity. What makes this piece fresh is that she links up the several traditions of Chinese wallpaper (East and West) and then follows its fortunes through the many historical twists and turns of the 19th and 20th century, and does not neglect todays wallpaper scene.

As to the blending, for example, it was not only Chinese pictorial traditions and scroll legacies that resulted in Chinese wallpaper, but also the Western ideas of perspective and indeed, the very idea of market-driven and portable “paper-hangings” that were the essential European contribution. She explains her theme: “through an examination of specific designs and use contexts this essay explores some of the contrasting identities of Chinese wallpaper in order to reveal their broader significance, dynamic and multivalent character and the rich variety of cultural ideas contained within them.”

Her explanation for how Chinese wallpaper became fused with the ideal and idea of the English country house is not exactly new, but it has seldom been stated so clearly. She writes that “Chinese wallpapers are also a regular feature in lifestyle magazines such as Country Life, which, since its foundation in 1897, has featured an article on a country house in every issue, alongside articles on art, architecture gardens and countryside issues. In this context, images of Chinese wallpaper instantly communicate strong visual messages about social and familial connections, heritage, wealth and history: concepts which define the “country house” and underpin the magazines ethos and reader’s aspirations.

She concludes that “the richness of the design presented on them and the stories and traditions which surround them have allowed generations of consumers and viewers to project their own ideas, fantasies, personal histories and aspiration onto Chinese wallpaper, establishing several contrasting identities for this rarefied global design phenomenon.”

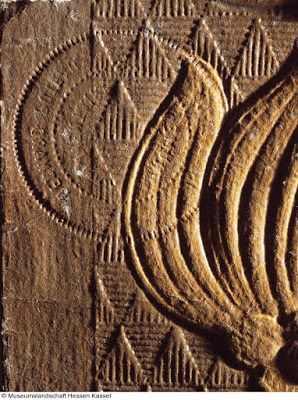

7. Japanese Leather Paper Or Kinkarakawakami: An Overview From The 17th Century To The Japonist Hangings By Rottmann & Co.”

One of the things you learn right off the bat from Wivine's article is that the origin of the rather impossible-looking name of Kinkarakawakami makes perfect sense.

kin = gilt

kara = foreign

kawa = leather

kami = paper

Therefore, kin-kara-kawa-kami means “gilt foreign leather paper”. This article is like Anna Wu's in that we get a head-spinning overview of how leather papers started in the East, came West, were influenced by Western design, moved back East, picked up more Eastern influence, and then headed back to be sold in the West. Or something like that.

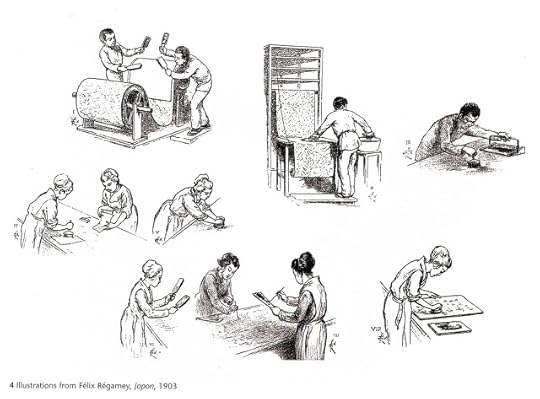

In this particular article Wailliez pivots nicely from his usual chemical and technical work, at which he is a master, in order to explain why we should care about kinkarakawakami (Japanese Leather Paper) and why this industrialized art form has endured. Reproduced here is a plate which shows the essential steps: beating wet paper onto the embossing rollers; gilding; stenciling; and applying other finishes.

This is an extraordinarily well-sourced article (67 footnotes) and includes dozens of references to important 19th century magazines such as Decorator and Furnisher and The Furniture Gazette, but also hard to find books such as Felix Regamey’s “Japon” (1903) and Alcock’s “Art and Art Industries in Japan” (1878).

Like early Chinese wallpaper, and dominos, Japanese embossed papers were generally made in a single sheet when they were introduced at large expositions. A key arrival was at Paris in 1873 where they caused quite a commotion. Later they were produced in longer rolls, like most wallpaper. Wailliez divides their history into three phases:

1. 1873-1884: many of these smaller pieces had an oily smell and had distinctly Japanese designs, not all of which were acceptable to a European market. They were therefore often used to put into the panels and coves of furniture, for example that of Godwin.

2. Starting in about 1882 a Rottman, Strome & Co. factory opened in Yokohama. This company's public relations campaign touted their new Westernized designs as not only washable but also “…Japanese, but not too Japanese…” This reinvention and blending of designs resulted in an all-over character that most decorators and the public found acceptable.

3. The third phase went from about 1890-95 to 1905. Japanese Leather Paper became a mass-produced commodity. Design luminaries such as Walter Crane, working for Silver Studio, delivered designs, many in the “Modern English” (Art Nouveau) style.

Wailliez, a conservator at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels, concludes that “Kinkarakawakami offers a synthesis in the conjunction of Western historicism and a Far Eastern renaissance resulting, paradoxically, in a form of modern industrial art.”

8. A Spanish Odyssey

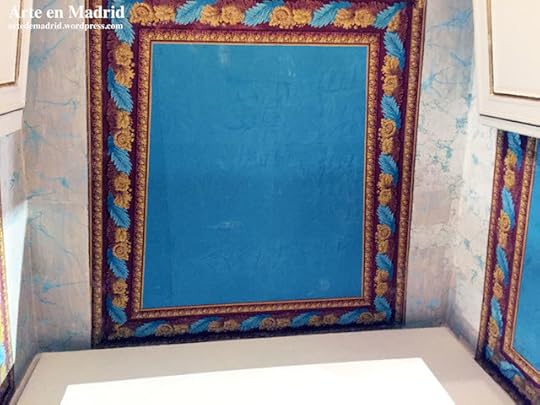

(A book review of “La Real Fábrica de Papeles Pintados de Madrid (1786-1836): Arte, artesanía e industria”, by Isadora Rose-de Viejo

This is the story of a royal manufactory of wallpaper. Not England, not France, but Spain. Spain? Spain.

What fascinates is that the de Villette family that obtained the rights to produce in Madrid (and obtained a monopoly on wallpaper production within 90 miles of that city) was based in France, and that the time period was early 19th century. And as we know, early 19th century French wallpaper was about as gorgeous as wallpaper ever became.

Another interesting detail is that the original proprietor after survived painstaking negotiations for years with the Spanish ambassador and various royalty happened to drop dead about a month before the final contract was to be signed. No problem, he had a brother, who signed the contract and set up shop. But then four years later he, too, dropped dead. No problem, there was a third brother. It was the third brother, Peter, who carried the factory into its heyday, roughly 1793 to 1829, and passed it down to his son, Segismundo Giroud de Villette. The life of the factory was about 50 years.

This is a Spanish language book, which of course presents a problem for English readers, but not an insurmountable one among wallpaper people, who are used to looking at pictures. Still, an English translation would be incredibly helpful in this particular case as it seems likely there are many references to the nuts and bolts of how, exactly, a wallpaper factory was set up during the late 18th century, what the working conditions were like, and what sort of product lines were offered. For example, part of the deal was that during set-up they were allowed to import 5,000 rolls of joined paper; they could also import the necessary raw materials such as pigments from France and Holland. Getting back to the product line, it would be interesting to know about not only the de luxe types, but also about the more moderate types which presumably were bought and sold as in most wallpaper factories. What we see in the pictures here are French-influenced and exquisite. Since the de Villettes had a license to import as well as produce it is not always clear which surviving papers were actually made in Spain.

One tiny detail of the social history is touched on when we learn that 12 local homeless orphans were hired by the factory as part of the deal. No doubt they took the lowest rungs of the work such as tier boys, hanging-up, and rolling up.

=========================

So there! I hope you enjoy this preview about this excellent 2015 edition of the Review!

Having said all that, if you are seriously interested in wallpaper, you _need_ to subscribe. It’s as simple as that.

On the plus side, they have an arrangement on their web site to pay via Paypal.

Like I said, if you are really serious about wallpaper, you really _need_ to do this.

Go to the “subscribe” link, plop in “non-UK member, 30£” and fork over $38.72 via Paypal.

https://www.wallpaperhistorysociety.org.uk/join-us/

Published on January 30, 2017 07:20

October 2, 2016

Wallpaper in the Royal Apartments at the Tuileries

Review: Wallpaper in the Royal Apartments at the Tuileries, 1789-1792, by Bernard Jacqué, in the journal Studies in the Decorative Arts, Vol. XIII, No. 1, Fall-Winter, 2005-2006 (Bard Graduate Center).

Review: Wallpaper in the Royal Apartments at the Tuileries, 1789-1792, by Bernard Jacqué, in the journal Studies in the Decorative Arts, Vol. XIII, No. 1, Fall-Winter, 2005-2006 (Bard Graduate Center).By Robert M. Kelly

The story of the royal family's steadily dwindling luck during the French Revolution is gripping. It becomes more personal yet when we learn about their personal choices, among which were wallpaper choices. In this article we learn what their wallpaper consisted of and why it was chosen to decorate the previously empty apartments of the Tuileries in Paris after the family was forced to abandon Versailles.

This article is ostensibly about the royal wallpaper, which was significant in both price and effect. But, M. Jacqué, former curator at the Musée du Papier Peint, has a magisterial and enthusiastic grasp of wallpaper history. Like a seasoned jazz drummer, he cannot resist throwing in a few extra beats. It's surprising that the editors at Bard were able to limit him to one exclamation point and thirty pages.

None of the wallpapers survive but thanks to billing records Jacqué nonetheless paints a believable picture. For example, he estimates the size of the rooms based on the linear feet of cornice border. Some of the rooms were large (the Queen's Dining Room was almost 114 feet in circumference). Madame Royale's Study was about half that size. No less interesting are the eight color illustrations of surviving late-eighteenth century installations. These styles and colors bring the text to life.

The section on Madame Royale’s cabinet d'entresol is a sort of mini-glossary of French wallpaper terminology. There are differences between camees and cantonnieres. “Objets en feuilles” refers to single sheets: this short-lived style featured a wide variety of vases, medallions, overdoor elements, framing, and rosettes.

Wallpaper was used extensively at the Tulileries, amounting to thousands of yards and almost 20,000 livres by the time the family was sent off to their last rather more sparsely furnished accommodations. As to why decoration was even an option in these perilous times, Jacqué explains that in the new setting "…monarchical ceremony, although subdued, continued in full public view. The sovereign still retained broad powers, not to mention a real popularity. It mattered, then, that the king was surrounded by décor suited to his status and functions."

Wallpaper was used extensively at the Tulileries, amounting to thousands of yards and almost 20,000 livres by the time the family was sent off to their last rather more sparsely furnished accommodations. As to why decoration was even an option in these perilous times, Jacqué explains that in the new setting "…monarchical ceremony, although subdued, continued in full public view. The sovereign still retained broad powers, not to mention a real popularity. It mattered, then, that the king was surrounded by décor suited to his status and functions."The king hesitated to spend too much on furnishings because of the political and financial crisis. Besides, he hoped to return to Versailles. The solution to these quasi-permanent decorative needs was wallpaper. By 1784 wallpaper was appropriate for royal use, at least in private rooms, though it cost far less than fabric. And unlike fine silks painstakingly woven in Lyons, wallpaper was almost immediately available.

But this was no routine redecoration. The single sheets just referred to (objets en feuilles) were often trimmed and pasted onto a background prepared with plain green or blue paper. Single-sheet motifs were more distinctive than those found on sidewall papers and were more carefully printed. These creative layers were applied within panels, and, more adventurously, on overdoors and ceilings. No wonder these installations were so expensive.

Not everyone was thrilled with the results. An anonymous letter criticized Thierry de Ville d'Avray, the official who oversaw the installations. The writer was of the opinion that "in royal residences such décor [wallpaper] is only suitable for the lodgings of domestics."

But any opposition would have been easily overcome by a supremely important voice, that of Marie Antoinette.

By this time her preference for wallpaper was well-known. She apparently went hog-wild in her dining room. She created an entirely new style with pale green grounds, wide borders of floral twists, and no less than 229 rosettes installed in spandrels and at the corners of panels. The cornice area sported four different borders.

The wallpaper in the study of Madame Royale was elaborate and even more expensive than the dining room paper. Other important rooms dissected by Jacqué are the King's Study (arabesques) and the King's Bedroom and Alcove (arabesques again, but this time in avant-garde colors).

Jacqué suggests that high-ranking Parisians imitated these rooms soon after their official and semi-official visits. He argues persuasively (through a careful selection of examples and by comparing like to like) that the royals were fashion leaders. According to Jacqué, the royal family followed aristocratic traditions of using the best decorative materials with "… great artistic audacity, even in difficult times," which certainly applies here.

He singles out the forward-looking color combination of black, orange and violet in the King's Bedroom. This combination predates by almost a decade a wider transformation whereby a warm color palette based on florals curdled into acidic tones.

Jacqué also highlights the Queen's innovative use of floral twist borders on plain grounds. He ruminates on a conflicted combination: rich floral borders surrounding austere, almost monochromatic antique images in the King's quarters. The borders looked backward to the Rococo while the cool classicism of the prints foreshadowed the Neoclassical style.