Dane Cobain's Blog, page 39

January 3, 2016

The Postcard Poetry Project: An Update

Hi, folks! Just a quick update to let you know about a slight change in my plans for the postcard poems that I told you about in a previous update. I’ve started having responses from people and writing up the poems, and I realised that there’s quite a lot of potential there.

So I decided to purchase a domain name – www.postcardpoetryproject.com – and to use that to blog about the experience. Of course, I can also use it to subtly promote my upcoming poetry book, Eyes Like Lighthouses When the Boats Come Home, too.

The Postcard Poetry Project will also be active on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, where I’ll be posting scans of each of the postcards that I send out. In the meantime, if you want to get involved, you can also submit an application over on the website or by filling out the form below:

First NameSurnameWord #1:Word #2: Word #3Address Line 1Address Line 2Address Line 3PostcodeCountry

Submit.inbound-button-submit{ font-size:16px; }

The post The Postcard Poetry Project: An Update appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

December 29, 2015

The Postcard Poetry Project: Get Involved!

Hi, folks! I’ve got something special for you today – I’ve got a project in mind, and I need your help. It doesn’t cost you anything and you’ll scoop yourself a unique piece of swag by participating, so get involved!

Basically, I have a bunch of postcards that I received over Christmas, and I’m planning on sending them out to people and writing poems on the back of them. Some of them are collectible postcards based on the beat poets, and some of them are based on the bestselling Secret Garden series of adult colouring books and require me to colour them in before I send them.

So what do I need from you? Well it’s easy, really – just fill out the form below and provide me with your name, your postal address, and three words of your choice. The best submissions will be turned into poems, which include those three words and which will be posted out to your address at no cost to you!

Bear in mind that I only have a limited number of postcards, and so the quicker you get your submission in, the more likely you are to be successful. I’ll also prioritise UK addresses, purely because it’s cheaper for me to post to them, but I’d like to hit as much of the world as possible.

Fill in your details below to be considered for inclusion, and good luck!

First NameSurnameWord #1:Word #2: Word #3Address Line 1Address Line 2Address Line 3PostcodeCountry

Submit.inbound-button-submit{ font-size:16px; }

The post The Postcard Poetry Project: Get Involved! appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

December 20, 2015

The Lexicologist’s Handbook: Sampler

Kafkaesque

Pronunciation: Kaff-ka-esk

Type: Adjective

Definition:

Characteristic, typical of or reminiscent of the surreal, nightmarish qualities of Franz Kafka’s writing.

Example:

Chris’ parents banned him from watching television after he started having Kafkaesque dreams.

Kaput

Pronunciation: Ka-put

Type: Adjective

Definition:

Broken or useless.

Example:

We couldn’t get back home because the car’s engine was kaput.

Kasbah

Pronunciation: Kaz-bar

Type: Noun

Definition:

A type of fortress or a formerly fortified complex of buildings, usually where a citadel is found.

Example:

Bettie had never been inside the Kasbah, but she knew that The Clash wanted to rock it.

Kayak

Pronunciation: Kye-yak

Type: Noun, Verb

Definition:

A type of canoe made from a light frame and a water-tight covering, originally used by the Eskimo. The verb describes the action of travelling using this type of transportation.

Example:

#1: Kevin planned to continue his expedition by kayak.

#2: They got stuck in the jungle and had to kayak downstream.

Kelpie

Pronunciation: Kell-pee

Type: Noun

Definition:

A water spirit from Scottish folklore†, taking the form of a supernatural horse that delights in the drowning of travellers. It’s also the name of an Australian breed of sheepdog.

Example:

The last thing that Leonard ever saw was the flowing mane of the kelpie.

Kenspeckle

Pronunciation: Ken-speck-ul

Type: Adjective

Definition:

Easy to recognise or conspicuous.

Example:

The kenspeckle elephant had pink skin.

Kibbutz

Pronunciation: Kih-bootz

Type: Noun

Definition:

A communal settlement in Israel, usually one that’s based on agriculture.

Example:

The old Jew hobbled back to the kibbutz.

Kibosh

Pronunciation: Kye-bosh

Type: Noun

Definition:

To put an end to or dispose of something, or to stop something from happening.

Example:

The businessman put the kibosh on the deal.

Kinaesthesia

Pronunciation: Kin-ass-thee-zee-a

Type: Noun

Definition:

The sense of the relative position of different parts of the body.

Example:

Even though there was zero gravity, the astronaut’s kinaesthesia told him his head was by his knee.

Kinky

Pronunciation: Kin-kee

Type: Adjective

Definition:

Involving, related to or prone to sexually provocative behaviour.

Example:

Gary’s dad had a passion for watching kinky movies.

Kismet

Pronunciation: Kiss-met

Type: Noun

Definition:

Fate.

Example

It looked like certain death, but kismet intervened and saved my life that night.

Kleptomaniac

Pronunciation: Klep-toe-may-nee-ack

Type: Noun

Definition:

Someone that’s addicted to stealing.

Example:

The kleptomaniac kept the pen that the examiner lent to him.

Knurl

Pronunciation: Nurl

Type: Noun

Definition:

A small projecting ridge, especially one that’s in a series around the edge of something.

Example:

Keith cut his finger on the metal knurl of the open tin of beans.

Kook

Pronunciation: Kook

Type: Noun

Definition:

A strange, crazy or eccentric person.

Example:

‘That old man?’ said Owen. ‘He’s nothing but a crazy old kook.’

Kowtow

Pronunciation: Cow-tow

Type: Verb

Definition:

To kneel and touch the ground with the forehead or to act in any other subservient† manner.

Example:

The general refused to kowtow to the emperor.

Kryptonite

Pronunciation: Kripp-ton-ite

Type: Noun

Definition:

A fictional element from the Superman series, created from the radioactive remains of the planet Krypton.

Example:

Superman had a mortal fear of kryptonite, his only weakness.

Kukri

Pronunciation: Koo-kree

Type: Noun

Definition:

A curved knife that grows broader and forms a point, often used by Ghurkhas.

Example:

Jonathan Harker cut off Dracula’s head with a kukri.

Kumquat

Pronunciation: Kum-kwot

Type: Noun

Definition:

A type of fruit that’s similar to an orange.

Example:

Laura’s favourite fruit is the kumquat.

The post The Lexicologist’s Handbook: Sampler appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

December 6, 2015

Close Reading: Allen Ginsberg’s America

I’ve chosen to carry out a close reading of ‘America’, a poem by Allen Ginsberg. Written in 1956, it was published as part of Howl and Other Poems (Ginsberg, Allen. Howl and Other Poems. City Lights Books, 1986).

From the first line, Ginsberg sets the tone of the piece. Addressing his country, he says ‘…I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.‘ He has ‘…two dollars and twenty-seven cents…‘ as he sets the scene – ‘…January 17, 1956.‘ Allen often doubted his own sanity and paid visits to psychoanalysts – it’s unsurprising that he ‘…can’t stand [his] own mind.‘ In ‘Footnotes to the Film‘, British novelist Graham Greene suggests that ‘The artist is not as a rule a man who takes kindly to life, but can his critical faculty help being a little blunted on two hundred pounds a week?’ Ginsberg followed that rule, and with only $2.27, we can see why his verse is so sharp.

When the poem was written, the United States was between wars – World War II ended ten years earlier, and the Korean War had drawn to a close. In less than five years, the U.S. would be involved in Vietnam. Ginsberg was sick of conflict; ‘Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb…’, he writes. ‘I don’t feel good don’t bother me.‘ He says that ‘I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind.‘; with Ginsberg, we could be waiting for a long time.

Three years earlier, Hugh Hefner founded Playboy magazine. With the mounting tension of the cold war, America had never seemed less ‘angelic’. Ginsberg asked ‘When will you take off your clothes?‘ By writing his poetry and baring his soul to the world, Allen was as naked as the playboy girls that were taking the country by storm. It’s understandable that he wanted his country to reveal itself during a time when international secrecy was imperative.

As the poem continues, Ginsberg’s imagery grows darker. ‘When will you look at yourself through the grave?‘ he asks. ‘When will you be worthy of your million Trotskyites?‘ Ginsberg’s poetry often explored communism (his mother used to take him to meetings when he was a child); here, he implies that America is unworthy of the Trotskyites that she’s home to, a dangerous statement to make in the midst of the Cold War. Bob Dylan, who would later become good friends with Ginsberg, satirised the hatred that many Americans felt in ‘Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues’. Throughout the song, Dylan blames ‘them god-darn reds’ for everything, even though he can’t find any ‘commies’ – the closest that he gets is when he finds ‘…red stripes on the American flag.’ Dylan and Ginsberg were both left-wing liberals, discontent with their country; it’s unsurprising that they formed a friendship.

When asking ‘…why are your libraries full of tears?‘, Ginsberg was well aware of the power of the written word. It makes the next line ironic – ‘…when will you send your eggs to India?‘ It’s hard not to think of the food crisis in the third world and the images of starving children that are broadcasted during the adverts of soap operas. With typical sarcasm, he states that he’s ‘…sick of your insane demands…’ and asks ‘When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?‘ In 1956, ‘…two dollars and twenty-seven cents…’ didn’t pay for much.

Despite the bitterness, there’s a touch of tenderness in Allen’s words – ‘America after all it is you and I who are perfect not the next world.‘ America’s machinery was too much for him, all that Ginsberg needed was Benzedrine and a typewriter. America ‘…made [him] want to be a saint…’ , an interesting choice of word from a Jew. It seems likely that Ginsberg was describing his ambitious goals as a poet, his desire to be a ‘saint’ of the written word.

By now, the reader has a sense of the structure – most lines are short statements or questions, with few commas. America feels fast, and we are hurried through emotions as Ginsberg reveals his outlook. His lines grow longer throughout the poem, as though his terseness has grown in to hostility. With this in mind, when Ginsberg says ‘There must be some other way to settle this argument…‘, it’s easy to wonder whether he’s suggesting a truce or a physical fight. With Ginsberg, it’s likely that he wanted to settle his internal conflicts by writing the poem, like a primal scream.

One of Ginsberg’s favourite techniques was to write about his friends, many of whom were famous. Allen was one of the founding members of the Beatnik movement, with Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs and others. It’s the latter that he mentions in America – ‘Burroughs is in Tangiers I don’t think he’ll come back it’s sinister.’ William Burroughs was notoriously eccentric, and Kerouac and Ginsberg both visited him when he was living in Morocco. It was whilst living in Tangiers that Burroughs wrote Naked Lunch, one of his most widely recognised novels, and it’s unsurprising that Ginsberg thought that his old friend had finally found somewhere to settle.

The next line, (‘Are you being sinister or is this some form of practical joke?‘), differs from the rest of the poem because it’s directed at Burroughs, and not at America. Jack Kerouac described Burroughs (under the pseudonym ‘Old Bull Lee’) in On the Road: ‘…[he] disappeared in the bathroom for his pre-lunch fix. He came out glassy-eyed and calm, and sat down under his burning lamp… ‘Say, why don’t you fellows try my orgone accumulator? Put some juice in your bones. I always rush up and take off ninety miles an hour for the nearest whorehouse, hor-hor-hor!’‘ Burroughs was crazy enough to play a sinister practical joke.

Allen’s poems were often written over a short period of time and featured few changes between their conception and publication. Perhaps that’s why he was ‘…trying to come to the point.‘ In typical Ginsberg style, America continues the rambling monologue until the end, reflecting upon everything that crosses his mind, from the Wobblies to Time Magazine, from Sacco and Vanzetti to ‘Them Russians them Russians and them Chinamen.‘ As with all of Ginsberg’s poetry, America is highly personal, and it helps to know the ‘…nearsighted and psychopathic… ‘ beatnik that wrote the poem before judging it.

Section One, Line One

Section One, Line Two

Section One, Line Two

Morgan, Bill (ed.). The Letters of Allen Ginsberg. Da Capo Press, 2008.

Section Two, Line One

Greene, Graham., 1937. Subjects and Stories. In Charles Davy, (ed.). Footnotes to the Film. Arno Press, 1970. Ch. 4.

Section Three, Lines One & Two

Section Four, Line One

Playboy Magazine, 2010. The Playboy FAQ. [Online] Available at: http://www.playboy.com/articles/the-p... [Accessed 10th March 2010].

Section Five, Line One

Section Five, Line Two

Section Six, Line One

Section Thirty One, Line One

Section Six, Line Two

Section Seven, Line One

Section Seven, Line Two

Section Eight, Line One

Section One, Line Two

Section Eight, Line Two

Section Nine, Line One

Section Nine, Line Two

Section Ten, Line One

Section Eleven, Line One

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. Penguin Classics, 2000. Pg. 137.

Section Eleven, Line Two

Section Fourteen, Line One

Section Twenty, Lines One & Two

Section Thirty, Line One

Section Thirty Two, Line Two

Section Thirty Six, Line One

The post Close Reading: Allen Ginsberg’s America appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

November 30, 2015

Interview with Ken Edwards, Editor of Reality Street Press

Dane: What are the most common mistakes made by poets that send you unsolicited submissions?

Ken: They have not bothered to find out anything about the press or what kind of poetry it publishes.

Dane: You’ve published work by Jeff Hilson and Peter Jaeger, two lecturers that we’ve already interviewed – what was it about their work that stood out to you, and how did Stretchers/Rapid Eye Movement/The Reality Street Book of Sonnets come about?

Ken: Jeff Hilson’s poems are adventurous, witty, sharp and sophisticated. Peter Jaeger’s REM sequence appealed to me because I have a common interest in dream narratives and their absurdities, and I liked the rigour with which he pursued the project. The Reality Street Book of Sonnets came about following a discussion with Jeff after one of my own readings when I presented some radical takes on the sonnet that I had written. Jeff thought there was an anthology to be done of poets similarly deconstructing the form, and he convinced me of this, and of his own expertise in putting such a book together.

Dane: It’s been said that the difference between poets and novelists is that novelists have agents – in your experience, how true is this?

Ken: Where there’s money to be made, there will be agents. Where there isn’t (and in 99% of poetry there isn’t) there won’t be.

Dane: How important is a poet’s reputation to you, as a publisher? Are you more likely to publish a writer if they’re well-known on the local scene or an established performance poet, or do you try to let the work speak for itself?

Ken: I try to focus on the writing, not the reputation. Realistically, I couldn’t publish only first-time or completely unknown writers, but I do try to ensure that the press doesn’t just publish a coterie of writers with ‘reputations’. Reality Street doesn’t specialise in ‘local’ poets or performance poets, though.

Dane: Tricky question – which Reality Street poet do you most enjoy reading and why?

Ken: Not going to answer this! I enjoy them all.

Dane: How many unsolicited submissions do you receive (on average) per year, and of these, how many do you usually publish?

Ken: I seem to get solicitations (mostly by email these days) almost daily. So let’s say maybe 365 a year. It may be that over a year one or at most two proposals from writers previously unknown to me will interest me enough to want to publish them.

Dane: Why do you think that small presses are important for the present and the future of poetry?

Ken: Small presses can take a chance on new concepts which would not interest those whose main motivation in publishing is to make a profit. They are therefore vital for the continuation and renewal of poetry, which would otherwise atrophy and die.

Dane: In general, what attracts you to potential Reality Street poets and how do you usually come across their work?

Ken: Usually, I read their work in online or print magazines or in other small press editions, or I hear them at readings. I am looking for all the usual things: intelligence, imagination, innovation, a feeling for structure, a unique concept.

Dane: What are the best and worst parts about working as the editor for Reality Street?

Ken: Reality Street is my project for creating a community of writers and readers. Those I publish inspire me in my own writing. I also enjoy editing and designing books. Those are the good bits. Like many small press operators, I am less keen on promotion and publicity, and the mechanics of selling books are tedious, though I do have a reasonably good business brain I think.

Dane: In your experience, how has the advent of the internet changed the way that small publishers operate, and has it been beneficial for you?

Ken: Without a doubt. With the disenfranchisement of small presses from the retail book trade (now dominated by the big conglomerates), the internet has been a lifeline for us to promote and sell books and to get authors and their work known.

Dane: If you could publish your dream anthology and attract your choice of living and dead poets to create original work for it, who would you ask to appear in it and why choose them?

Ken: Blake, Lorca, Rimbaud, Rilke, William Carlos Williams, Olson, and oh, why not Dante? He would be good, and Homer, and why not get Sappho to write more than the odd fragment? Probably they would quarrel among themselves though.

Dane: Do you feel that it’s possible for (particularly underground) poetry to break in to the mainstream and still maintain its artistic value and merit?

Ken: I think it would be very difficult. What is ‘the mainstream’ looking for? I don’t think it’s actually poetry. Having said that, I’m quite heartened by Rae Armantrout winning the Pulitzer prize, and Christian Bök’s Eunoia becoming a bestseller.

Dane: Which Reality Street publication has caused you the most problems? What problems were they, and how did you overcome them?

Ken: There have been various technical problems, for instance in trying to put together a collection of Maggie O’Sullivan’s out-of-print works from the 1980s. They were originally composed on a typewriter, and while not actually concrete poetry, these texts depended crucially on the look of a typewriter face. So we ended up scanning hundreds of pages, which was a chore but worth it.

Dane: How important is networking for both poets and publishers? How many poets have you published after meeting them at readings, book signings and similar events?

Ken: I am not a very good networker, but readings do provide an opportunity to meet people.

Dane: What’s your best piece of advice for young poets that are seeking publication by a small press?

Ken: Read as much as you can. Learn from other poets and writers, living and dead, and also from film-makers, artists, musicians. Attend readings. Make contacts. Submit your work to magazines that publish the kind of work you are interested in. Subscribe to magazines and buy small press books. Write and write. There are no short cuts.

The post Interview with Ken Edwards, Editor of Reality Street Press appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

November 23, 2015

Agents: The Difference Between Novelists and Poets

Note: This essay originated as a piece of work that I did during my third year of university.

During this essay, I aim to answer the following:

It has been said that one of the differences between novelists and poets is that novelists have agents, while poets do not. Discuss and describe why you think that is the case.

I intend to answer this question by referring to texts that I studied and the interviews that I conducted during the course of the module, and by researching the methods that novelists and poets use to publish their work.

One of the key differences between the novel and the poem is that the novel is designed to be read by somebody else, while poetry is usually an intellectual exercise and is often designed for performance. Novels, particularly best-sellers, can bring in huge amounts of income for the author and the publishing house, while poetry is notoriously capitalism-free. It’s near-impossible to earn a living from poetry alone – most poets that live on the proceeds of their writing are forced to take up a second job as a travelling lecturer, a journalist or an editor. In an interview that I conducted, Roehampton lecturer and published poet Peter Jaeger said: ‘The only poets that I know who have agents are poets who are primarily novelists, such as someone like Margaret Atwood.’

Peter and his fellow lecturer Jeff Hilson, who was interviewed at the same time, are examples of poets that don’t have agents. For them, the publishing process is much more personal. ‘One sends stuff out occasionally to magazines,’ explains Jeff. ‘And one’s asked to submit stuff to magazines, and I guess if you’re lucky enough, a publisher will ask you for a manuscript at some point.’ This approach automatically forces the poet to become his own agent and leaves him with more creative control over his work, although there can still be restrictions from the publisher. As poetic movements are often small and intimate, poets are generally aware of the publications and presses that publish similar poetry to their own. It’s important for poets, as well as for novelists and journalists, to have an awareness of their contemporaries and to read widely to give their work context. Jeff explains, ‘The community that we’ve got involved in is so small, we know all the publishers anyway.’

Poetry isn’t a money-maker, so agents are obsolete. As Peter pointed out, ‘Agents are involved with money, that’s why they’re there, and they get a percentage.’ When dealing with a niche market (which poetry is), agents find it difficult to earn enough to make it worth their while. In the world of fiction, where bestsellers can shift a thousand times as many copies, the money is more lucrative and the agent finds it easier to thrive.

For many, the poetry world has an edge over fiction because of the widespread use of chapbooks, small collections of poetry that are usually cheap and often home-made. It makes sense, in a circle where the words are more important than the money. When Peter started publishing, ‘the first thing [he] did was a little D.I.Y. thing that [he] made [himself], a little chapbook.’ This is a common approach among unpublished poets that want to spread their work around – the simplicity of not needing an agent is attractive. If a poet publishes a series of well-received chapbooks, he’s likely to get targeted by a publisher anyway, regardless of whether he has an agent.

But, as Jeff pointed out, some ‘superstar’ poets do have an agent, even if it’s because of their public image instead of for their poetry. Jeff says, ‘I think Ted Hughes used to have an agent,’ but Peter claims that even the modern-day American superstars don’t have agents. ‘Robert Pinsky,’ he says. ‘Poet Laureate under Clinton, he doesn’t have an agent. Charles Bernstein doesn’t have an agent. Ron Silliman doesn’t have an agent.’ If such high profile writers can publish without the need for an agent to sap the little revenue that they earn, there’s nothing to stop young, aspiring poets from doing the same.

The veteran poets stress the importance of networking and getting to know more about the field that you’re working in. After the chapbooks, Peter ‘started getting things in magazines here and there and basically it was because [he] knew the magazine and [he] knew that they would be interested in [his] kind of work. There was a bit of research involved at first where [he’d] have to look and see what was going on.’ For fiction writers, much of the pressure is relieved by their agents, who effectively do this research for them and contact appropriate presses and publishers on their behalf.

Something else for poets to consider is the option of appearing in anthologies, which present a small amount of their work alongside the work of other authors. This enables the poet to share their work with the general public without expensive production costs on their part. As anthologies are usually genre-specific, the poet has the advantage of being exposed to readers that have an interest in the field that they work in, whether from the title of the anthology or from association with the other poets. But publishing in an anthology isn’t without its problems – Peter ‘…[tends] to compose [his] work for the book…’, which can lead to a feeling of fragmentation. He sees his last three books as ‘pieces that go together.’ In such a case, the work is supposed to be presented as a whole, rather than as individual poems excerpted in to an anthology.

For performance poets, work is often self-distributed in the form of video clips on YouTube or audio recordings on websites like SoundCloud and MySpace. For this type of poetry, the transcript of the performance is less important than the performance as a whole, so there’s no need for agents to negotiate book deals. The poet’s appearances are usually organised by the poet himself, whether he appears at a local open mike night or gets a booking off the fame of previous performances. It’s in situations like these where the poet and the agent are in a lose/lose situation if they work together – the poet gains nothing and loses a percentage of any profit that he makes, while the agent puts in time and effort and gets a low financial return.

In the last twenty years, the internet has had a huge effect on the availability of self-published poetry. Before, the cheapest and easiest option was the printed chapbook, which still needed to be distributed by hand to the poet’s audience. With the advent of the world-wide-web, poets have been able to share their work with their peers across forums and message boards. Years ago, web programming required an extensive knowledge of coding – nowadays, thanks to simple HTML editing software, poets can easily share their work without any knowledge of programming languages. Blogging platforms like WordPress allow the poet to concentrate entirely on the content of their site by providing a standardised and easy-to-use layout, simultaneously offering useful features for them to use to update their followers and embed their news feeds on other websites. This hands the publishing power back to the poet, who doesn’t need an agent as a go-between – just a computer and an internet connection.

In the rare case that a poet and agent can work together for high financial return and wider circulation, they’re often publishing a Manifesto or an anthology. It’s also possible, though difficult, for a poet to grow famous enough for his readership to increase to such a level that an agent can make a profit and help the poet at the same time. Such circumstances are rare, and most poets are motivated more by their work than by the small financial reward that it may provide.

Poetry is often considered less glamorous than other areas of writing, and most people think of a novelist when imagining a ‘writer’. Even a best-seller of poetry can shift fewer copies than a badly-performing novel, meaning that novels bring more money to the writer and inevitably, the agent. It’s possible for novelists to publish and distribute their work without an agent (and even without a publisher), but it’s far more common for a novelist to have an agent than a poet. This is due, in part, to the difficulties of releasing a novel – there’s no such thing as a chapbook novel, and it’s unrealistic to suppose that small publishing houses and self-distributing writers could release the chapbook’s prose equivalent.

I also interviewed industry gatekeeper Ken Edwards, poet and editor of the Reality Street press. He suggested that the most common mistake made by poets that are looking for publication is that ‘they have not bothered to find out anything about the press or what kind of poetry it publishes.’ This demonstrates the varying roles that he expects the unpublished poet to take on – not only are they responsible for creating the work, they must also scout out appropriate literary publications and send out their work accordingly. Even so, Ken gets ‘solicitations (mostly by email these days) almost daily’ and says that of these, ‘one or at most two proposals from writers previously unknown to me will interest me enough to want to publish them.’

Ken also agreed that in his experience, poets with agents are an uncommon sight. He said, ‘Where there’s money to be made, there will be agents. Where there isn’t (and in 99% of poetry there isn’t) there won’t be.’ This concise but accurate statement epitomises the central argument in this essay – without sufficient amounts of money, there’s nothing for the agent to feed on. It’s possible, in certain circumstances, for an agent to work for free – for example, when acting on behalf of a friend or a family member – but it’s standard practice in the industry for the poet to distribute their work themselves, whether selling chapbooks and manuscripts at readings or sending a submission to a poetry press.

In Ken’s opinion as the editor of a small press, his business gives poets the chance to ‘take on new concepts which would not interest those whose main motivation in publishing is to make a profit.’ This suggests that small presses, while dooming the poet to less distribution, offer him a chance to experiment with language and form and to innovate. For many poets, particularly those that are relatively un-established and pushing something new, the freedom of the independent press is worth the low circulation. This is also important for poetry to develop – Ken says that small presses ‘are therefore vital for the continuation and renewal of poetry, which would otherwise atrophy and die.’

The advent of the internet has also had a big impact on the options that are available for unpublished poets. Thanks to sites like WordPress and Blogger, poets can easily share their material with the world across the internet with no extensive knowledge of coding required. When the internet first began to assert itself as an important publishing space, the poet needed to pay a coder to make their content available online. Now, with the advent of simple WYSIWYG software like Microsoft FrontPage and Adobe Dreamweaver, the poet can share his work with the world across the internet for free. As the owner of a small press, Ken agrees that the internet is important: ‘With the disenfranchisement of small presses from the retail book trade (now dominated by the big conglomerates), the internet has been a lifeline for us to promote and sell books and to get authors and their work known.’

The internet has also made it easier for performance poets to boost their reputation – many, like Joshua Idehen, publish videos of their work on YouTube. SoundCloud and MySpace allow poets to share footage of their readings, and many combine them with Twitter to keep fans up-to-date. The only problem, as Jeff points out, is that ‘there are just so many of them. It’s a huge distraction from doing what might be called ‘proper reading’ or ‘proper research’, having to spend increasing hours in the day finding out what people have been saying on their blogs.’

Even older poets, like Ron Silliman (currently in his sixties), are keen to advocate the importance of an online presence. According to Jeff, ‘He came over a couple of years ago and said that any poet that doesn’t have a web presence is committing writing suicide.’ He sees it as a portal and says that people will ‘just stick your name in to Google and see what it comes up with. If that’s the first way of coming across people’s work then that’s no bad thing. Even if it’s just a reference to the books you’ve published, you know. Because where else are you going to find out about that? You’re certainly not going to find out about it in the press, not in the popular press, not in The Guardian, not in The Independent.’

It’s clear from Ken that many small presses and their editors expect their poets to do so much more than hand over copy. His advice to young poets is: ‘Read as much as you can. Learn from other poets and writers, living and dead, and also from film-makers, artists, musicians. Attend readings. Make contacts. Submit your work to magazines that publish the kind of work you are interested in. Subscribe to magazines and buy small press books. Write and write.’ And as an afterthought, he adds: ‘There are no short cuts.’

For most poets, their writing alone generates nowhere near enough income for them to survive on. Most write in their spare time and work, with many opting for jobs as lecturers, freelance non-fiction writers or journalists to pay the bills while keeping one eye on the art of writing. In our interview, Peter talked about the time he had dinner with Raymond Federman while at university. ‘He said, ‘You know, you and I are very lucky because we have these university places.’ We’re so lucky we can just maintain a bit of intelligent, critical thought by being in a university context.’

Even a book of poetry that sells well can be forgotten about completely in the space of a year. Peter says, ‘I had the dubious pleasure of seeing my book ‘Prop’ in the Waterstone’s best-seller list, and then within about a year in the half-price delete bin at Foyle’s so… fame is a fleeting thing.’ Peter was one of the lucky few – he received relatively good distribution, which doesn’t always happen. Jeff remembers ‘walking in to the Norwich branch of Borders and there were three or four copies of ‘Prop’ there.’ Peter’s lack of an agent clearly had no negative effects when it came to the release and distribution of his manuscript.

To conclude, agents are uncommon among poets because there’s barely any money in the business and agents need to make a living too. Unlike with novelists, where the writer and the agent need each other, there’s no advantage to the poet or the agent if they combine their efforts. It’s possible for an agent to work for free or for a poet to generate enough money to make it worth their time, but in general there’s no natural symbiosis between the two. Even when they do work together, there’s little-to-no advantage for the poet – at best, the agent does what the poet would have done anyway, saving him time and effort. The poet and the agent run in different literary circles – in the great food chain of literature, poets are meerkats and agents are armadillos.

See: www.youtube.com.

See: www.soundcloud.com.

See: www.myspace.com.

See: www.wordpress.com.

What-you-see-is-what-you-get: For more information, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WYSIWYG.

PiP – Joshua Idehen: My Love. [Online Video]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=280_dpqOQ9w. [Accessed: March 24th, 2011].

See: http://www.twitter.com.

The post Agents: The Difference Between Novelists and Poets appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

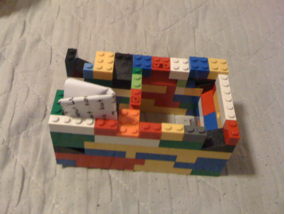

Lego

Note: This piece was part of a three-dimensional piece of innovative fiction work that I delivered during my final year at university. It was printed out onto a piece of paper and wedged inside a castle made from Lego, that was included as part of the fictional Benjamin Hughes’ time capsule.

Lego

At school today we played with Lego and I made a castle for me and Lucy to live in when we finish school and get a job, I hope she likes it because I want us to both live happily ever after and get a butler and a maid and a dragon. Did you know dragons breathe fire? I saw it on TV when I was supposed to be asleep, daddy was watching it and the BAD DRAGON breathed fire and burned down the village and it made me sad because all of the people didn’t have a home and everyone should have a home to sleep in – that’s why I built the castle. I wanted to build a dungeon so I could put Sam in it, he’s horrible to me just because his mummy likes crack and his daddy doesn’t have a job and they fight all the time and he drinks the BAD STUFF and they do BAD THINGS over and over and over again until the walls shake. Mummy says they’re BAD PEOPLE but when I went to his house I ate one of their special cakes and fell asleep and dreamt about Lucy, so they can’t be that bad. But now Sam bullies me, he likes to hit me but that’s okay because daddy says if I don’t hit him back then I’m the bigger man, but it still hurts a lot. I try to hide from him but he always finds me and Lucy tries to stop him but she’s not as strong as me and I’m not as strong as Sam and Sam’s not as strong as Mr. Griffiths but Mr. Griffiths never finds me and then mummy shouts at me for getting in to fights and daddy looks disappointed. I don’t mind though, they don’t have to love me, I have Lucy and she loves me very much and when we live in our castle I won’t let mummy in and I won’t let daddy in and I won’t let Sam in and I won’t let anybody in but Lucy and the butler and the maid and the dragon and maybe baby dragons if Lucy wants them. Do you like the walls? I wanted to use lots of colours because Lucy likes rainbows and I like red and green and blue and yellow and Lego and castles and dragons and Lucy and Lucy says she likes me too, she says she wants to marry me when we grow up and I think I want to marry her too. I don’t know how grown ups tell when they’re ready, how do they decide? HOW DO I DECIDE? I just don’t know…

The post Lego appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

November 15, 2015

Progress Report: November 2015

Hi, folks! Today, I wanted to revisit an old blog post from a couple of months ago to give you a bit of an update on where I am with my various projects. Let’s do this!

Eyes Like Lighthouses When the Boats Come Home:

Eyes Like Lighthouses is my book of poetry. So far, I’ve memorised about two thirds of it, and I think it’s pretty much there. I am, however, writing one final suite of poems based on Paul Armfield’s Found, and so it would be good to include those if I can. I’m also looking for a new illustrator as my old one had to pull out due to time commitments around her wedding. I’m expecting Eyes Like Lighthouses to come out in early 2016.

Former.ly:

Former.ly is the novel that I’ve been working on for two and a half years. It’s taken this long because I’m an idiot, and I decided to write it out by hand. Two months ago, I was finishing off the final chapter – now, I’ve completed my first edit and I’m on to my third read-through. This is due to go into editing in January, for a Spring 2016 release through Booktrope.

Forsaken RPG Game:

Gosh, remember when I was working on this? The Forsaken RPG game is complete and on general release (you can download it for free over here), and there’s also an official walkthrough that you can take a look at.

Social Paranoia:

I was just starting this off during the last update – I’m now about 90% of the way through, with just a couple of chapters left to do. It’s on about 32,000 words right now and will still need editing etc., so I’m probably looking at a Summer 2016 release.

Robots V.S. Zombies:

This project has stalled for now, but that’s not to say that it’ll never happen. I didn’t finish planning it out, but it might still happen – I’m going to let it simmer for a while and see what happens.

Tammityville:

This is a working title at the moment and it’s still a pretty loose concept, but the idea of this is a sort of semi-fictionalised memoir about growing up in working-class Tamworth at the turn of the millennium. They say you should write what you know, right?

Anyway, I think that’s pretty much it for current projects that I’m actually likely to pursue through to completion. But that could change! That’s why you ought to follow me on Facebook and Twitter and to check back often for further updates. In the meantime, I’ll see you soon!

The post Progress Report: November 2015 appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

November 8, 2015

Former.ly: Chapter Eleven (Second Draft) (Excerpt)

John and Peter hadn’t finished – far from it, in fact. But first, they had to deal with an unexpected backlash from the staff, starting with Flick.

“What about us?” she asked. “I don’t know about everyone else, but I’ve invested time and money in this company. I’m not so sure about taking on extra investment – do we really need it? Is it worth having some idiot in the Valley telling us what we can and can’t do?”

“We thought about that,” said John. “And we think we’ve come up with a solution.”

“Good. Because if the deal’s already signed, it’s too late for you to change it.”

“No-one’s changing anything,” Peter said. “You’ll still retain your shares, and they’ll be worth even more by the time you sell them. Besides, we’ve cooked up a deal where John and I will retain full control of the company, so there’s no need to worry about that. The contracts look legit, so take it easy and enjoy the ride.”

“I’m not convinced,” murmured Kerry, stroking the stubble on his chin. “And I don’t like it.”

“Understood,” said John. “But sometimes there are things that we need you to trust us on. We can’t tell you everything – in fact, the less we tell you, the better. Former.ly is built on secrecy.”

“Just how many secrets are there?” I asked.

“Loads,” Peter replied. “And we’re about to tell you another one.”

The post Former.ly: Chapter Eleven (Second Draft) (Excerpt) appeared first on DaneCobain.com.

October 31, 2015

Former.ly: Chapter Ten (Second Draft) (Excerpt)

That night, we foiled another break-in. Nils suspected one of his men of taking a bribe and launched a review of personnel – nothing was taken and no damage was done, but the whole place was turned over in the middle of the night. One of the guards was knocked unconscious, and another was found bound and gagged in the alley outside.

Peter was furious, because we had no way of knowing whether our data had been compromised. We didn’t think so, but how can you be sure? Nils’ CCTV cameras caught four figures dressed from head to toe in black, like the guy from The Princess Bride. They rushed in, overpowered the two guards and sprayed paint over the cameras. That’s the last we saw of them, which gave them around two hours in the office before the cleaners disturbed them.

“My men saw nothing,” said Nils, addressing us in our temporary war room. “But I don’t know if I can trust them. Either way, don’t worry – I’m looking into it.”

“Worry?” laughed Flick. “Two of your men could have been killed! And you think it might have been an inside job? For all we know, the people we’re trusting to protect us are being paid by someone else to try to kill us!”

“Yeah,” I agreed. “And why are we even paying you in the first place? What’s the point in having security guards if they’re going to get themselves knocked out at the first sign of trouble?”

“And where were you, Dan?” Nils snapped. “They’re brave lads, whether you trust them or not. I’ll do some digging, because you can never be too careful, but my priority is to find out how they got into the building in the first place. I’ll step up security, too.”

“I wonder,” John murmured. The conversation had descended into chaos, and I was the only one who seemed to hear him. “Perhaps there’s another solution.”

The post Former.ly: Chapter Ten (Second Draft) (Excerpt) appeared first on DaneCobain.com.