Dave Fecak's Blog, page 9

October 10, 2013

Hello World! What Every CS Student Should Know About the First Job

Anyone involved with hiring entry-level technology professionals (or reads posts on Reddit’s cscareerquestions forum) is aware that students are being prepared by schools for how to do work in the industry, but are often ill-prepared on how to find work in the industry. There is a major difference between the two, and many grads are being edged out on jobs by equally or even less-qualified peers who were just a bit more proactive about their career. If you think finding a job is only about internships and GPAs, please keep reading.

Some students feel that if they aren’t working 10 hours a day building the next Twitter from their dorm room, or if they didn’t intern at Google or Amazon, that they will struggle to find work. This is hardly the case, and I assure you that if you do a few things during your college years (that require a minimal time investment and no money), you will be several steps ahead when it is time to apply for your first job.

Everyone knows about finding internships, good grades, and putting together a solid résumé. But there’s more to it than that for today’s grads. Here are some things that college freshmen (or even high school students) that intend to pursue a career in technology can do to give themselves a head start on the competition.

I tend to find that college students and even early career candidates often have Facebook, Google +, and Twitter accounts, but no LinkedIn profile. But I thought LinkedIn was a place to signup only when I was about to start looking for a job? Nope. LinkedIn is your Rolodex (forgot my audience) address book of professional contacts, and there are plenty of reasons to start building that database and network even before you are a full professional.

Did you intern with a company last summer? Connect to your co-workers on LinkedIn. Did you interview for an internship, but didn’t get the job? Connect with your interviewers on LinkedIn. Did some industry professionals come to campus and speak to your class? Connect with them on LinkedIn. Did a recent grad or classmate start a business? Got a favorite professor? Connect!

Beyond just the ability to connect like you do on Facebook or Google +, LinkedIn also has thousands of virtual networking groups that include a wide range of specific and general topics. Many of these groups are related directly to employment, and most of them are monitored (and sometimes infested) by recruiters that could be valuable connections to make before graduation.

Once your profile is completed with your experience and any relevant technical buzzwords to attract recruiters or hiring professionals, you may expect to receive connection invites and blurbs on job opportunities. Having more connections means that you will appear in more searches, but most in the industry still use some discretion in connecting.

I don’t want to overstate the importance of LinkedIn as I think too much is often made of the site by so-called “social media experts”, and endorsements have become a running joke, but industry pros that you don’t know well are more likely to accept a LinkedIn connection than a friend request on Facebook. Graduating college with anywhere from 50 to 500 LinkedIn connections gives you a place to start your job search that is infinitely more productive that applications to random jobs on Monster or Craigslist.

I write about GitHub so much that even I’m sick of watching myself write about GitHub (where’s my t-shirt?!). If LinkedIn is your professional address book, GitHub is a combination of your sketch pad, notebook, and even a Trapper Keeper folder (did it again) to file past assignments. There are other code repo sites out there, but GitHub is the leader today.

What’s so great about GitHub? First, by using it you’ll learn how to use the Git tool itself and how version control works to some degree, which has value in itself (and another Skills entry for your résumé). You can also take advantage of GitHub Pages, which gives you free hosting and customizable themes for a web page that you can have up in minutes. More importantly, your GitHub account is perhaps one of the best ways to demonstrate your experience to potential employers.

If you are going to be writing some bits of code for various school projects, even if they are small and generic exercises like FizzBuzz or Conway’s Game of LIfe, why not retain those as potential work samples at GitHub? As your skills improve, you can go back and refactor and optimize your code so that it is representative of your current ability level.

Once you develop some comfort level with your coding skills, you can explore some other public repos and start contributing to open source projects or even start your own. You don’t need to have some substantial GitHub account upon graduation in order to get a job, but there is no reason not to keep your code all in a safe place for others to view down the line. A GitHub account has quickly become a common request from many employers in the industry, so having these samples available can make a significant difference.

Stack Overflow is a question and answer site used by a large percentage of the programming world to help themselves and others. It has a massive collection of past threads that is like a FAQ for the tech world, as well as many unique threads that would be considered Rarely Asked Questions. The site’s gamification model allows participants to earn reputation points for highly rated questions and answers, and those points can serve as yet another potential indicator of your knowledge as an entry-level candidate.

Can I really get a job based on some arbitrary internet points I earned through asking or answering questions? Of course not. But again, it serves as an indicator of your interest in the profession, the time you invest in your craft, and your willingness to both seek and provide answers with others in the industry.

I wouldn’t suggest spending hundreds of hours on the site in order to accrue a massive point total, but checking out the questions being asked and chiming in when appropriate has value. The questions and trends will also give you a finger on the pulse of the industry, and perhaps ideas as to which languages or technologies may be lacking a pulse.

Users’ groups and Meetups are another way to demonstrate your interest while learning. You attend class because you have to (or are supposed to anyway), but you attend Meetups because you want to. I have managed a users’ group for almost 14 years that met on a college campus for several years, and many of the student attendees now have highly successful careers. In addition to the ability to hear informative presentations and group discussions, Meetups are perhaps the most useful way for students to meet industry pros that may be incredible resources during your first job search. (If you haven’t figured this out on your own, connect with your fellow Meetup members on LinkedIn.)

If you can’t get to group meetings due to location, there may even be some users’ groups and Meetups that happen right on your college campus. None at your school, eh? That’s too bad. If only there were a group on campus… Congratulations, you are now the founder (and chapter president, of course) of the Springfield University Python Meetup!

Conclusion

Creating a profile in any of these sites takes minutes and has no cost. With LinkedIn you can start making connections in seconds, and logging in even once a month to accept and send connection requests is pretty standard. Using GitHub for your coding assignments or projects will become second nature, and exploring other repos can be done as time permits. Stack Overflow is something you can visit once a week or as necessary, and over time you will build reputation while learning. A user group or meetup is typically a monthly meeting. All this adds up to just a couple extra hours a month, which is a small investment for the rewards it can provide.

Like this article? My DRM-free ebook Job Tips For GEEKS: The Job Search is now available for $9.99.

October 4, 2013

How to Network Less For Geeks

The fundamental importance of professional networking for today’s career-minded tech pro has been pounded into our heads for many years now. ”It’s not what you know, it’s who you know” gets spouted by everyone who gets denied a job or interview, and there is certainly some truth in the saying. The mere thought of hobnobbing and mingling with other technologists at an event may instill terror in many (myself included sometimes), and most in the industry yearn to be evaluated purely on their ability to code and not their ability to shake hands and make good eye contact. If you are repulsed by the concept that your elbow-rubbing skill may be integral to career success, or are perhaps uncomfortable in traditional networking situations, please continue reading – it’s less necessary today than most think.

When visualizing networking, most in the industry probably picture a room with a number of people separated into small groups of varying size having discussions. (Googling “professional networking” confirms my suspicion) It could be an industry conference, meetup, or even a more social event such at a bar or restaurant. The images will be appealing to no one but salespeople, and even many of them may shudder.

As communication and professional relationship building have shifted from the physical world into the electronic and virtual, who you know and who knows you have taken on new definitions. People develop what they consider deep romantic relationships from thousands of miles away without ever meeting (sometimes without speaking), so why would anyone think the professional world would be any different?

What is the purpose and goal of networking?

Simply speaking, the purpose of networking is to develop relationships with others in order to hopefully produce mutual professional benefits. Those mutual benefits are (for us) increased access to job opportunities, with the belief that someone’s positive impression of you will translate into a foot in the door or a preferable consideration for employment.

The most important aspect of the relationship isn’t the depth (how well the person knows you) so much as it is their perception of you. A contact may be more willing to help if they truly know you well, but the minimum goal is to get someone willing to say something nice about you that they would not be able to say about a stranger.

Soft and Hard Vouch

Saying something nice is a form of vouching, defined as a personal assurance on someone or something. You may be willing to give what I call a soft vouch to someone you’ve never even met. If you have exchanged several emails and chatted online with someone and read their blogs, and have at least some understanding of that person’s professional reputation, you are probably comfortable saying that person seems personable and/or qualified. You wouldn’t stake your reputation on it, but you’d give at least that soft vouch.

A hard vouch is when you use your goodwill by recommending someone for hire or consideration. This may be a person that you have worked with extensively in the past or have known well for many years. However, tech pros today are increasingly willing to give this hard vouch to people they have never met, due to the nature of online relationships and the wealth of electronic information available that forms a reputation. If you’ve collaborated with someone on an open source project for a period of time, know their coding ability, and he/she seems nice on Twitter and Facebook, a hard vouch is not much of a stretch.

Second-hand vouching and influencers

Vouching gets more interesting when members of a community give added weight to recommendations by one respected member (the influencer), and it reaches the point that community members are willing to make a recommendation purely on that influencer’s vouch. As a real-world example, suppose someone that knows you and your business fairly well refers a candidate to you, saying that the candidate was interviewed and was not a good fit for their organization but is likely an excellent fit for yours. Would you even need to see the résumé before agreeing to interview? Would you be willing to bypass the phone screen? And if you weren’t hiring, would you pass that recommendation along to another contact?

These second-hand vouches happen every day within more established networks, which were not always established in the traditional way. I can point to at least a dozen or so respected people in my network where their recommendation alone would give me no pause in also recommending that person to clients. In other words, I’ll give a fairly hard vouch for someone I’ve never previously heard of under certain circumstances. This can have risk, but I’ve found it very low. Of course, making a profound negative impression on one of these influencers can almost serve as being blacklisted within a community as well.

How can the goals of networking be achieved in other ways beyond the traditional?

Technologists that spend many hours suffering through events in the name of networking may want to reconsider the value. This is particularly true for those that don’t find the personal interaction as natural, as they may actually do more harm than good by appearing. All we want is someone to vouch for us professionally. Instead of trying to alter your personality to become a better networker, focus on two things:

Building reputation – It is much easier and (in my opinion) more valuable to develop a reputation within a community than it is to develop meaningful individual relationships with many members. Reputation is best achieved with a multi-platform approach.

The quickest way in our industry might be to collaborate on large projects where many people can see your work, but most don’t have this luxury. Blogging can be powerful and less time-consuming, while the simple act of sharing thought-provoking and relevant articles with your connections on social networks is at least somewhat effective. I can immediately think of people I don’t know at all that post really interesting things on Google+ and Twitter, and their activity and curation alone scores at least some points.

Answering questions (or asking thoughtful ones) in forums will get name recognition as being both knowledgable and helpful, whether or not the forums keep score (like Stack Overflow or Quora). I’ve seen this first hand on sites that I frequent, where my services have been recommended to others just based on my writing. If public speaking is within your comfort zone, that is another option.

Even investing 15 minutes a day into some of these activities can reap fairly quick benefits.

Getting on the radar of influencers - The influencers can make a huge impact on your future job prospects. The first challenge may be to identify who these influencers are. Often, they may be the most visible members of the community and in some position of leadership, which could be within a company or within a community organization (Meetups, conferences, etc.). One quick and dirty way to gauge influence is through social network subscribers and connections, which is far from foolproof but at least some indicator. For our purposes, we are probably going to place more value on GitHub followers over Facebook friends. Start with small communities focused on specific technologies or a shared location to see how easy it is to identify influencers.

Once you’ve identified these influencers, how do you get their attention? In an ideal world it happens naturally, simply because your reputation caught their eye. If not, try to direct their attention to something that should interest them, or just write up a short note to introduce yourself. Networking with an influencer with a wide audience is the way to go if you do choose to spend time meeting people.

Conclusion

At the end of the day a strong reputation will open doors without a need for much traditional networking, but all the open doors in the world won’t make up for an undesirable skill set or low levels of ability. The need for technologists to network becomes much less important as the ability to display work is increased. Your reputation, and in some cases just your code, can open doors as well.

Like my work? I wrote a book.

September 27, 2013

Salary Negotiation For Geeks

Advice on salary negotiation is abundant, but material written for the general public may not always be applicable to a technology sector where demand is high and the most sought after talent is scarce. There is quite a bit of misinformation and the glorified mythology of negotiation is often mistaken for the much less interesting reality where little negotiation actually takes place.

Let’s start by going over a few “rules” that are often thrown around in these discussions.

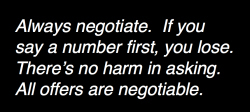

Always negotiate

Using absolutes is never a good idea (see what I did there?), and there are definite situations when you should not negotiate an offer. For example, entry-level candidates who are considered replaceable with other entry-level candidates often do more harm than good by negotiating, particularly when the job being offered is among the most desirable. We will cover when you should and should not negotiate a bit later, but there are clearly some conditions when it’s not a great idea.

There’s no harm in asking for more/Doesn’t hurt to ask

Actually, sometimes it does. When you propose a counteroffer, there are only a few realistic outcomes.

1. Yes, it’s a deal.

2. No, but here is a compromise.

3. No, we won’t budge.

4. No, your demands are unrealistic and you have exposed some character trait during the negotiation process that we didn’t recognize before. We rescind our original offer. Bye.

In the first two scenarios the choice to negotiate made you better off and the third scenario is a wash. It’s the fourth scenario that is probably the least likely, but is the only one where your desire to negotiate caused you harm (particularly if this is a job you really wanted and an offer that you would have taken at face value). Companies usually won’t rescind an offer based on a request to negotiate, but the way you negotiate or reasons cited may cause an offer to be rescinded.

It is not common to see offers rescinded, but it happens often enough that anyone making a counteroffer should be well aware of the possibility before asking for more. As a recruiter, I always try to educate job seekers of this potential outcome before proposing a counteroffer, as I do not want any blame for losing a job opportunity.

If you say a number first, you lose

This one is quite popular today and comes up whenever negotiation is discussed. It’s not possible to even attempt to evaluate this statement without some definitions. Based on how I’ve heard this phrase used, we should clarify both number and lose, and mention the time when this conversation is happening.

Number in this case should usually refer to a desired salary. Some apply number to also mean any mention of current compensation, and I can argue both sides of the argument as to whether or not providing current salary is potentially harmful.

Those firmly against providing current salary say that it’s nobody’s business, and a company will just take that number and match it or maybe throw 5% on top of it. If you are unemployed and provide your most recent comp figures, perhaps they even go 5% below that number. These are possibilities, of course, but if you know the true market rate for your skills you never have to accept anything less.

I’ve provided current salary details to almost all clients for many years (at their request), and sometimes the number is accompanied by a note saying that the candidate is now being paid below market rate and it is our intent to correct this underpayment. Other times the current comp number is acknowledged as above market, with the understanding that the candidate does not expect that number to be matched.

The concept of win/loss adds another wrinkle. Most seem to define losing as not getting the absolute maximum amount a company would be willing to pay for your services. As there is no way to know this mystery figure and managers won’t reveal that they would have paid more, it’s impossible to truly gauge a win or loss on this basis. Wins and losses could be measured by salary offer relative to market rate, but information on market rate is imperfect. Most probably define a win or loss by being offered above what they were willing to accept, which of course is usually dependent upon the candidate’s self-evaluation of market rate. If the data shows that senior engineers make 100-140K, where should I fall in that range?

It is clearly not advisable to provide a salary that you would fully agree to accept before even going through the interview process. A company has the right to ask for a target, but can you be held to a number given before you were able to gather extensive information about the expectations of the job, career path, team, environment, benefits, etc.? If you are somehow required to give an expectation before an interview, be sure to add this caveat that the number is given with incomplete details and your expectation could go up (and even down perhaps) once those blanks are filled in.

Just throw out an arbitrary high number and let the company respond with something lower

This is perhaps the worst negotiating advice you can get, and will often result in no offer being provided. A company will usually dismiss even a strong candidate if they are unwilling or unable to be realistic during the process. It makes the candidate appear uninformed (at best) and unprofessional/immature, and the outcome is rarely positive. It seems most professionals know better than to do this, but I have heard enough candidates suggest this to me that it bears repeating.

All offers are negotiable

No, they aren’t. Even if all companies are willing to negotiate, that doesn’t mean that your offer is going to be negotiated. Smaller companies that don’t typically have pay bands and clearly defined ranges that correlate to specific job titles may have more wiggle room on both salary and other benefits and perks. It’s less likely that a large company can customize your vacation, health benefits, or 401k plan for obvious reasons.

When to negotiate an offer

As was mentioned earlier, there are several situations where it is useful and advised to negotiate.

When the offer is clearly below market (without other upside)

There is no reason to work for less than market rate for your skills. Market rate is difficult to define, but some research into the data and anecdotal evidence will go a long way. This is tied to your personal perception of your level as well as the employer’s evaluation, and the two may not be in the same ballpark.

When you feel you are in a secure position of strength

As opposed to negotiating just for the sake of negotiating, this is negotiating because you can and should. If you receive multiple offers, decide which job you would take if all else were equal and try to maximize that one offer. When your skill set includes something that is very rare and in high demand, you are often in a position to ask for more. Your greatest position of strength is when you:

1. Possess a skill set highly desired by multiple employers

2. Have multiple legitimate job offers in hand

3. Are fully employed at or above market rate

Even if you only meet one or two of the requirements you still may be in a position of strength.

When an offer matches all of your criteria except one or two that break the deal for you

Often an offer will meet almost all of your expectations but falls short in one or two key areas that make it unacceptable. Someone who requires additional time off due to a family situation may find ten days of PTO to be a dealbreaker. In cases where the current offer would not be accepted due to a specific condition, there is no real loss if the offer were to be rescinded.

When not to negotiate an offer

When the risk of losing the offer far outweighs the potential gain

When the additional amount requested is negligible, it often isn’t worth negotiating if there may be risk of losing the offer. Asking for 2% on top of an offer for your dream job doesn’t seem like the reward would warrant the risk. The risk of an offer being rescinded is often measurable by the number of available candidates at the company’s disposal and the age of the offer. An offer made several weeks ago to an entry-level candidate (or anyone with a common skill set) has a high risk of being rescinded.

Sometimes I’ll work with a candidate who requests say $2,000 more on an offer. This may amount to $1.00 per hour if you do the math. In these situations, I advise my candidates on the risk/reward and let them make the decision.

When you have no data or justification as to why you are asking for more

If you are asked why you want more, can you give a reasonable explanation as to why your experience warrants the amount? This applies to people who negotiate for the sake of negotiating. The justification doesn’t have to be an incredibly elaborate study, but asking for more just because you want more might raise eyebrows. Usually these justifications will rely on market data or details of your current package relative to the package being offered.

Like tips like these? Check out my book.

September 16, 2013

How to Prevent Crying During Your Technical Interview

A recent blog post Technical Interviews Make Me Cry by Pamela Fox tells the personal tale of a technologist and conference speaker who gets a Skype/Stypi interview for her dream job, becomes stumped on a technical question, breaks down in tears, almost abandons the interview, fights through it, and eventually gets the job. Everyone loves a happy ending, and it was courageous for the author to tell her story so publicly as a service to others. However, I think some of her takeaways and the advice she provides can be improved upon.

So how can we prevent crying or freezing up during a technical interview?

Let’s start with the author’s advice. She offers that interviewees should prepare for the format and not just the material, and writes

“If I had made myself go through the uncommon and uncomfortable situation of being put in (sic) the spot and asked to answer a random technical question, maybe I would not have cracked so easily when it came to the real deal.”

Haven’t we been preparing for a question and answer format, in one way or another, for almost our entire lives? I can understand being a bit uncomfortable with Skype and an online collaboration tool, or some level of adjustment to having someone watch you code during a live exercise, but being asked random technical questions is not all that different than taking exams in school (other than the potential for real-time feedback). You have a math test, you study math, and you are asked math questions on that test – some you may have anticipated, some you did not. More about how school messed us all up later. Going into an interview one should expect to be asked some technical questions, some random and some that you see coming.

Pamela’s second takeaway

“If you’re an interviewer: seriously consider the format of the on-the-spot technical interview and whether that’s the best way to judge all candidates.”

This is a good point and certainly fodder for the continuing saga and ongoing debate regarding the best ways to evaluate technical talent, but this isn’t actionable advice for anyone that has an interview scheduled for this afternoon. Take-home assignments and collaborative exercises are becoming more common as part of the process, but we are not all there yet.

In the middle of the article, she gives us this additional lesson.

“It was then that I realized the most important part of prepping for the phone screens: confidence.”

Confidence is important, but I don’t see how confidence would have necessarily helped her situation. If she were more confident, would she have immediately come up with an answer and not froze up? Perhaps? This might be more a function of the impostor syndrome that she mentions, and not applicable to most of the world.

Here are my takeaways

First, if you want to get good at something, you have to practice. Pamela wrote

“…technical interviews. I’ve been lucky to have very few in my life…”

Herein lies the first problem. One should not be surprised when failing at something they’ve only done a few times before. Interviews are high-stakes situations, and being a skilled interviewee requires practice. We can debate whether taking an interview when you are not on an active job search is a noble pursuit, but if you have gone several years without interviewing I assure you that today’s technical interview may be unrecognizable. If you don’t care to interview when you have no intent of taking a job, perhaps sit in on an interview at your company. The observation gives you risk-free access to the process, and you can see how others handle situations that are potentially stressful.

** First takeaway - Interview, whether giving or receiving, more often than you job search.

The author wrote about her preparation process.

“I wasn’t sure how to prepare for it, what sort of questions I’d be asked. I figured I’m known for more frontend work these days and folks may be under the misguided illusion that I’m a JS expert, so I read through parts of the ECMAscript spec, reviewed the craziness of prototypical inheritance in JS, and read through all the frontend posts on that engineer’s blog. Part of me thought I should study more, study enough that I’d feel confident that I could handle *anything* they threw of me, but that would have taken me months, if that. More likely, I’d never feel 100% confident.”

This is how most tech pros prepare for interviews, which is why books that list answers to commonly asked questions sell bundles. She read through tons of technical information that she anticipated would be covered during her screen, and even felt she should keep studying so she’d be more confident. But what didn’t she prepare for?

It seems as though the author didn’t prepare for the high probability that she would be asked a question that she couldn’t answer right away. She never prepared to fail, and because of that oversight she froze, panicked, and began to cry. Had she anticipated that being stumped was a likely scenario, and had she known that there are many technical interviewers who will continue to ask questions until you get one wrong, she would have been much more comfortable when it happened.

This is why schools have fire drills.

**Second takeaway - Realize that you will not be able to answer every question, and prepare an answer for when you get stumped.

Shortly after the phone interview debacle, the author had some pretty low points.

“And then the sobbing REALLY began. I had just finished the first step of the interview process with the company I desperately wanted to work for, and I’d bombed it. I’d frozen, I’d cried, I’d stumbled through my somewhat shoddy solution. Did I really deserve to even be an engineer, if I couldn’t even make it through a phone screen? What gives me the rights to give talks at conferences, if I can’t make it through standard interview processes? I was pretty damn frustrated with myself.”

All of these thoughts and feelings that led to questions about even being fit for the industry, which were the result of what would subsequently be deemed a successful phone interview. How did she get there?

Remember earlier when I mentioned school? Suppose I were to give you a test, and I provide the results in real-time with a ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ signal after every response. Ten questions into the test, you manage to get half correct. How are you feeling right now about your test performance?

We’ve been programmed since an early age to think of success based on certain scales, and most of us use common academic grading standards to judge test performance. This false expectation leaks into interviews, where an interviewee may feel that 5/10 is failure without having any concept of how others have fared. Answers to technical interview questions are often not judged as simple right/wrong, and some credit is usually applied to approach and process. Sometimes interviewers don’t expect you to know most answers.

**Third takeaway – Manage your expectations properly, and accept that an interviewer’s definition of success may be vastly different than traditional academic standards.

The defining moment for our author was a fateful decision to abandon ship or press on.

“The only thing going through my mind was ‘I can’t do this.’ I stared at the ‘hang up’ button on Skype. I could just press it, and he would go away, and then I’d give up on my obsession, and I would convince myself it was a stupid idea in the first place.”

Of course, we all know that she kept going with the encouragement of the interviewer and eventually got the job. It’s reasonable to think that the interviewer didn’t expect candidates to cry, but it’s not unreasonable to think that the interviewer felt the exercise would be difficult for Pamela and most similarly qualified professionals. How a candidate reacts to stress, surprise, and failure are all potential markers for success in the job. If I were hiring a pilot, I’d ideally like to put her/him in a flight simulator and observe a crash landing or engine failure scenario.

Luckily, the interviewer was understanding and the author worked through the discomfort to come up with a satisfactory solution. Pressing ‘hang up’ would have served no positive for either side in this case.

**Fourth takeaway – Don’t give up just because you think you are failing. There is nothing to gain by quitting, and you may learn some things about the process and about yourself by sticking it out.

Change your mindset on interviews and keep the tissues in your pocket.

My ebook offers absolutely ZERO answers to algorithm questions,

but does prepare you to fail!

September 13, 2013

To The Programmers, On Programmers’ Day

To the Programmers on Programmers’ Day,

To the childhood spent with cassette players and VIC-20s, and Saturdays loitering in the local Radio Shack for a turn on the TRS-80.

To those who maybe weren’t always the coolest kids in high school, but were often the smartest.

To the Rubyists and Lispers and Pythonistas, the architects, and the web and mobile developers who are able to show their children what mom/dad made. And to the embedded engineers who write code most people don’t even know is there.

To the thousands of Googlers, Yahoos, and Microsofties who make our email work and build tools to find anything imaginable. And to the many millions more who build things to run our homes and our lives.

To the hackers, the makers, the tinkerers, the startup junkies, the hobbyists, the open source contributors, the newbies and the grayhairs, who live in IDE’s and editors by day and often by night.

To those of you who have some of the best jobs in the world, with the highest hiring demand, yet are sometimes prone to saying that spending several minutes deleting potential job offers from your inbox can be a chore. And to those that are hustling for their next gig.

To those who solve the most complex technical problems in creative and elegant ways, yet are forced to distill their career for most people down to “I work with computers”.

Today, we salute you. Thanks for all you do.

With the deepest respect,

Job Tips For Geeks

September 5, 2013

Why You Took The Wrong Job

The decision to join a new employer and the process leading up to the move can be fraught with emotional attachments, irrational fears, and incomplete information. Since job searches in technology often include self-interested third parties of varying influence (e.g. recruiters, founders, hiring managers) acting within a highly competitive hiring environment, the job seeker can be pushed and pulled in several directions, sometimes based on half-truths and distortions. The result of the job change (or the decision to refuse an offer and stay put) in many circumstances is buyer’s remorse, where regret can be felt rather quickly.

First let’s look at the more common reasons that candidates regret taking a new job, and then explore one rather simple solution to avoid the mistake.

You overvalued salary without considering other details of the job and package. There is obviously much more to a job offer than pay, but when numbers are discussed job seekers become distracted from any red and yellow flags that were concerns prior to the offer. If your new position includes a longer work week and an employer with a lower benefits contribution, that 20% raise could actually be a compensation decrease when calculated on an hourly basis. The value of work-life balance and additional money is complex and will fluctuate over the course of a career.

You made an emotional decision over a rational one. Perhaps you were drawn to a less than ideal job due to loyalty to a friend or former co-worker that is employed by the company and needs your help. Fear of taking on new responsibilities and making decisions to stay in a comfort zone will keep some from ever feeling challenged and fulfilled with a new position. Emotional decisions can even be tied to compensation, as individuals tend to have attachments to certain numbers. That 95K job might come with better benefits and plenty of upside, but if that 100K job is your first making “six figures” you may be irrationally swayed.

You focused on short-term gains instead of long-term. Entry-level candidates who typically have no savings and significant debt will often go to the highest bidder, placing little weighing on other factors such as skills and career development. Taking an offer without consideration for how a job will allow learning and growth can negatively impact your future marketability (and compensation) for years to come. In some cases the higher paid big company job may lead to boredom, where the lower-paying startup could consistently challenge you and allow you to show tangible accomplishments to potential future employers. Items such as sign-on or relocation bonuses provide instant gratification for job seekers, even though they are only one-time payments. A short-term gain can even be satisfied by a job title for some, where the simple act of adding “Senior” on a business card might influence a decision much more than it probably should.

You ran from the job you had instead of pursuing the job you want. Any port in a storm. The decision to accept an offer becomes relatively easy when your current position is making you miserable. Spats with co-workers or bosses can hasten job searches that may be based on questionable rationale.

You were made promises during the hiring process that the employer couldn’t or didn’t fulfill. Hiring managers or recruiters often dangle a potential carrot in front of recruits that they may not be able to deliver. Often the bait will include a tasty new project that would look very attractive on your résumé, or an expedited path to a leadership position. These promises are dangerous for both sides, and accepting positions based on an uncertain future rewards is questionable without detail of the promiser’s track record. I frequently hear anecdotes from candidates that were hired as the next-in-line CTO but quickly realized that would never come to be.

You were talked into something you clearly never wanted in the first place. Experienced recruiters (both agency and internal) can be quite skilled at manipulating candidates and overselling an opportunity, and successful entrepreneurs must be effective in getting others excited about investing in their endeavor. Recruiters may prey on your fears, however irrational those fears may be, to get you to accept their offers and reject counteroffers or the offers of other employers. Company founders implore recruits to help make their dream a reality, and could ignore whether the role or environment are a fit for your goals. When money is added to the mix, candidates can be their own worst enemy and can talk themselves into jobs that they would never have taken otherwise.

One effective method to avoid taking the wrong job

A job search has lots of moving parts. One way to potentially avoid taking the wrong job is to create a defined and relatively static target job opportunity that you are willing to take, and to lay the details out before starting a job search. In my book I encourage job seekers to write specifics about the dream job, and I also have them draft an equally important list of dealbreakers (defined as details of a job that would be unacceptable under any circumstances).

These short lists typically include minimum salaries, maximum commute distances, work hours, desired technologies, industries, company size, and almost any imaginable detail of a job or company. Search criteria should be prioritized where trade-offs are possible, as most seekers would be willing to commute a couple extra miles for more money or benefits.

The value of creating a physical list is that you will regularly refer to it when being pitched new positions or while evaluating offers. Share the lists with someone who knows you well, such as a significant other or family member, and ask them to hold you accountable to what you’ve written during your job search. This person is your designated driver who must be willing to talk you out of a bad decision if you get tipsy from all the love you are getting.

When job offers arrive bearing fancy titles and large salaries bundled with promises of future rewards, delivered by trained salespeople who know how to spin, it is common for a candidate to disregard their initial search criteria and dealbreakers – which directly leads to accepting offers based on the mistakes listed above. By employing a little self-discipline and using a couple easy lists (and a designated driver to keep you honest), you should be able to prevent yourself from taking a job based on the wrong reasons.

If you liked what you read, you might enjoy my DRM-free ebook

August 9, 2013

Recruiters Are Pretty (and How to Find One)

You would need to be blind not to notice that tech recruiting firms are now tending to hire young and attractive female rookie recruiters, which is an obvious strategy (similar to the so-called “booth babes” at trade shows) to get the attention of the predominantly male tech audience. Some of the LinkedIn recruiter profile photos border on racy, and perhaps sad. I should confess here that I too use a LinkedIn profile photo, which is probably best described as smug (included below, for science).

Since I started blogging I have been regularly approached by readers living hundreds of miles away asking if I know a recruiter in their geography that might be able to help them find new work. For every ten people that hate on recruiters, there are at least a couple that see value. Many tech pros complain that they are only being approached by the aforementioned 22 year old crowd with an average six months of recruiting experience, sending canned messages with a pretty LinkedIn profile photo. How much solid career advice can you get from a new liberal arts or PE grad who was waiting tables until a couple months ago? Very little, and I should know – because that was me 15 years ago (except Economics and bartender).

I deal with internal recruiters that work at my client companies, but readers want intros to people who do what I do. These internal recruiters only represent their company, whereas agency recruiters like me can provide several job opportunities. Instead of just replying with “Sorry, I don’t really know anyone in your area”, I thought I’d provide some thoughts on methods to find someone you will want to work with in your job search.

Actually finding a recruiter should be quite easy, but how do you know if that recruiter is any good? Let’s start with the search for a recruiter, and then talk about some positive and negative indicators that might give some insight into their ability to help.

How To Find Your Recruiter

Referrals from other technologists

The most obvious way to find a recruiter is to ask around. Who to ask? Start with former (and current if you trust them) co-workers or friends in the industry. Another source may be local user group and meetup leaders, who are regularly approached by recruiters and could know a few that are ethical and helpful. The more veteran among technologists, and particularly independent contractors, should have a wider recruiter network than most.

Referrals from HR/internal recruiters/hiring managers

If you are lucky enough to have some contacts in HR or internal recruiting, they could be the most effective resource. HR pros who have been in the business for a while will know which recruiters and firms are best and which may be cutting corners to make a buck. Your former manager, or any hiring managers that you know, will have some historical anecdotal data on their success rates with certain firms or individuals.

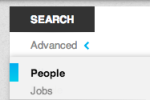

Recruiters use LinkedIn to find you, so why can’t you do the same? Not only can you find the recruiter, but you can also discover some valuable information on their background – not to mention, PRETTY PICTURES! Here’s how you do it:

1 – Click on Advanced at the top of the main LinkedIn screen (just to the right of the search bar)

2 – On the upper left side of your screen you will see several fields. Make sure you are doing a People search (and not a Jobs search).

3 – Type ‘Recruiter’ and something else that you feel is specific to you in the Keywords field. Try ‘developer’ and the name of a technology that a recruiter might lazily use to brand you, such as a language. Recruiters typically will fill their LinkedIn profiles with the technologies sought for their clients, not unlike job seekers who populate their tech skills section to catch the automated eye of a résumé scanning system.

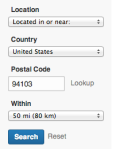

4 – Enter the zip code of the area where you wish to find work and consider setting a parameter. Some recruiters work nationally, but local knowledge goes a long way if you are seeking to work in a specific geography. Once you start entering the code, a box appears with a dropdown menu. Depending on where you live, you may want to select 25 or 50 miles (probably good for northeast or mid-Atlantic US), or up to 100 miles (for midwest).

5 – On the right, make sure you have 3rd + Everyone Else checked under Relationship. This will maximize your results, particularly if your LinkedIn network is not large.

6 – Click Search

7 – Repeat, and vary the words you used in Step 3. You should see a few different faces as you adjust the keywords.

How to Evaluate Your Recruiter

We’ve found some LinkedIn profiles and viewed recruiter pics (some pretty, others smug). Now what? What methods can we use to eventually choose which recruiter(s) we want to contact? Are there any indicators as to who might be best to use?

Just like recruiters do to find out more about you, a simple Google search or looking up the company on Glassdoor might lead to some useful info. It also just might lead to more pictures.

As recruiters today rely heavily on LinkedIn, you can be sure that any serious technical recruiter pays close attention to their profile. The LinkedIn profile IS the recruiter’s résumé. Thus, we can assume that everything we need to know about a recruiter should absolutely be included there.

Here are a few things to consider

Industry experience

This will indicate quite a bit. For one, agency recruiters with many years of experience will have witnessed most scenarios imaginable, and should be a valuable guide throughout the search. They should also have deep networks, loyal clients, and insight into the local market. The job market turbulence of the first dot com boom/bust and the more recent recession have served to cull the recruiting herd, so those that survived through must have been successful.

Keep in mind that recruiting is highly competitive, revenue-driven and results-based, and recruiters are primarily compensated on a commission basis. Staying employed in the agency recruiting business is dependent upon results (getting people hired). However, some of the successful recruiters might just be the best at selling snake oil.

Consistency

There are a few different items to consider when we evaluate consistency.

Has this recruiter remained in the industry throughout their career or did he/she have some unrelated experience somewhere along the line? For someone who leaves the industry and returns, recruiting is probably a job and not a career. Some recruiters might change areas of focus and switch from technology to finance, in which case the depth of specific industry expertise may be questionable.

Has the recruiter moved between agencies on a consistent basis? The recruiting industry has job hoppers too, and often this can be due to lack of success with different firms. Since recruiters compensation is commission-based they are cheap to hire, so taking a chance on a job hopper poses little risk for the recruiting agency.

Has the recruiter bounced back and forth between the agency side and internal recruiting? This one is important, and perhaps a bit controversial. In case you didn’t know, successful agency recruiters make a very good living. To put it in relative terms, a top agency recruiter can make two to three times (or more) as much as the typical salaried internal company recruiter at most firms (exceptions, of course), and agency recruiters often earn significantly more than the tech pros they represent.

So why would a recruiter leave a lucrative agency job to go work as an internal recruiter for a hiring company? Stability is one factor, as the promise of a consistent paycheck with no risk is attractive to many. The desire to build a company and actually help create something big is another cited reason, and even though I’ve been successful on the agency side for my entire career I’ve given consideration to internal roles on occasion.

Some agency recruiters jump to the internal side because they couldn’t survive on the outside, and sought the safety of an internal recruiting job. Some will revert back to agencies, as even the most experienced recruiters can be hired by agencies for cheap.

Credibility

Does this recruiter have any details that stand out above the others? A list of LinkedIn endorsements is a bit of a joke, but you can give at least some credence to a recommendation that required effort and thought. Are there any extracurricular activities listed that may give some evidence of expertise?

A professional blog or writings can provide insight into the recruiter’s attitudes towards industry trends. Is the recruiter involved with any industry organizations? Has the recruiter actually worked in the technology industry, where it is assumed the recruiter would have greater understanding?

There are a few certifications that recruiters can achieve, but their value is questionable due to the fact that most are virtually unknown even within the industry. There is no degree in recruiting that I’m aware of, so education isn’t usually a valuable indicator.

Conversation

The best way to evaluate a recruiter is to talk to him/her. Your career is important, so partially entrusting it to someone requires a level of mutual respect. If you find a recruiter immediately tries to sell you on all open jobs he/she has regardless of fit, chances are this person isn’t very concerned with your best interests.

Find a recruiter who shows curiosity in your goals before trying to push every job on you. Is the recruiter even paying attention to what you are saying?

Like this? Thinking about a job search in the near future? You might like my book.

July 30, 2013

LinkedIn Spam (?) and Recruiters: A Guide for Geeks

Recruiters take quite a bit of heat from those in the tech community based on what many refer to as LinkedIn spam, and the definition of spam within LinkedIn’s context seems to be fairly wide. Recruiter shaming in public forums and blog posts about making ridiculous demands or nasty responses when being presented a potential opportunity are usually popular among a certain set.

Some potential recruits are a bit more creative, like making the Contact Me on their blog a puzzle that most recruiters will be unable or unwilling to solve. I for one truly admire his creativity and think this is a great way to keep recruiters from knocking based on your desire to have a web presence. +1 for allowing both a Python and Haskell option, which just makes me want to hire him more!

As I’ve said before, when the shaming and mockery of recruiters is deserved I’m not against it – I’ll grab my popcorn and watch. Although I probably use LinkedIn much less than others in my industry I am cautious to try and keep my use appropriate. Bashing recruiters is becoming a bit cliché, and I think the backlash related to LinkedIn in many cases seems unwarranted for a few reasons.

Many technologists use their LinkedIn profile as a way to attract employers – If you go to a publicized networking event and I approach you with a quick, “I’m Dave! Nice to meet you.”, punching Dave in the face is probably not an appropriate response. The environment you place yourself in (a networking event) should create the expectation that someone may try to engage you. Independent contractors, unemployed tech pros, and recent graduates often use LinkedIn specifically as their preferred method (over say Monster or Dice postings) of exposing their experience to recruiters and potential employers. If you are not using LinkedIn for this purpose, it might be useful for you to include that information on your profile.

It can be pretty confusing for a recruiter to get a nasty response from some LinkedIn users and a warm response from others, particularly when both profiles could be virtually identical. LinkedIn has products specifically targeted to recruiters and hiring entities. Being contacted about jobs on LinkedIn shouldn’t be considered a surprise or an infringement on your rights. LinkedIn is pretty clearly trying to allow people to find and contact you for this purpose.

LinkedIn limits how many characters you can include in an invite – If you’ve been complaining that the recruiter who pitched you a job through a LinkedIn invite gave you vague information, I’d encourage you to try pitching someone a job at your company through two tweets (and no URLs). Not to mention, you of course want to know why this recruiter feels you might be a good fit for the job. And you want to know about the job itself. Funding status? Tell me about the founders at least?? Chances are you will have to leave out something the potential hire would find important if you are limited to about 300 characters.

If a recruiter finds you on LinkedIn, the only way to contact you may be an invitation to connect - Most recruiters don’t expect that you will want to connect to them (as if connecting has some sort of implied relationship, which in most cases it clearly doesn’t) after a single relatively anonymous interaction on the internet. The majority of LinkedIn profiles for technologists don’t include an alternative contact method for those they are not connected to already. If the recruiter is unable to find other contact information the invitation to connect may be the only way to reach you, even if the recruiter feels that connecting is somewhat premature based on the lack of a prior relationship.

What to do when a recruiter sends you a LinkedIn invitation to connect, and how to prevent it?

Some thoughts

Remember that you are fortunate – You have a job that people are falling over themselves to hire you to do. The inconvenience of clicking Accept or Ignore is about as first world as a first world problem gets.

Don’t respond – Simply deleting the request takes hardly any time at all. If you get a lot of these requests and deleting them takes a bit more time, please see the point above.

Respond, but don’t connect – If it is something you might want to discuss but you aren’t ready for the whole level of commitment that a LinkedIn connection surely brings, just send a response and take the conversation to email. No harm done.

Create a canned response – Write a few sentences that you can cut/paste into a quick reply, explaining if/why you were offended and what (if any) type of opportunities you might want to hear about in the future. Recruiters who value their reputation will try and take your recommendations to heart (for the minority that have one) and be more courteous in the future.

Clarify on your LinkedIn profile that you don’t want to talk to any recruiters – Why is this necessary? Because you are on LinkedIn. If recruiters disobey this request, shame away.

CONCLUSION: You have every right to complain if you are approached for a job that is not at all appropriate to what you do, and you can certainly shame recruiters that ignore any notices you posted on your profile to try and prevent such contact. But let’s not call every LinkedIn contact about a job LinkedIn spam – for most, that is exactly what LinkedIn is there for.

Like my writing(s)? I wrote a book.

July 25, 2013

Job Hopping For Geeks

I first wrote about the topic of job hopping back in 2007 and I feel the advice I gave then is still relevant in 2013, although the perceptions and attitudes of most hiring managers have evolved significantly. The post in 2007 was partly inspired by a past client (financial trading firm) that would only accept résumés of software engineers that were employed at their current company for a minimum of seven years. Today, it seems more likely that my clients would discourage me from submitting candidates that have had too long a tenure. Times have changed.

As a refresher, the term job hopping is used to describe a history of somewhat frequent moves from one employer to another after spending little time working for a company. Some use the one year mark as the measure of a hop, but multiple moves before a second or third anniversary should also earn you the label with most traditionally-minded recruiters and managers. However, being tagged a job hopper in the tech industry is not nearly as troublesome as many would want you to believe.

A survey of 1500 recruiters and hiring managers last year had the following results:

“According to 39% of recruiters, the single biggest obstacle for an unemployed candidate in regaining employment is having a history of ‘hopping jobs’, or leaving a company before one year of tenure. 31% consider being out of work for more than a year as the greatest challenge in regaining employment, followed by having gaps in your employment history (28%).” – Bullhorn survey

Unfortunately, this result was misinterpreted by an article on job hopping that appeared in Forbes earlier this year. Let’s see if you can spot the subtle difference.

“Nearly 40% of recruiters and hiring managers say that a history of hopping is the single biggest obstacle for job-seekers, according to a recent survey conducted by recruiting software company Bullhorn.” – Forbes.com

Did you catch the difference? The Forbes article calls job hopping the biggest obstacle for job seekers, while the Bullhorn survey clarifies that job hopping is the biggest obstacle for unemployed candidates. One could agree that having a job hopper reputation while being unemployed is a tough combination, but anecdotally I’ve found that employed job hoppers have a much easier time. After all, job hoppers are clearly skilled at getting hired.

Why is it necessary to make this distinction between job seekers and unemployed job seekers? Because unemployment acts as a sort of multiplier or catalyst towards the “unemployability” of the job hopper, which explains why almost 40% of managers and recruiters would essentially call unemployed job hoppers the least attractive group. It is also useful to point out that in high-demand labor markets with relatively low unemployment rates such as the market for software engineering, the job hoppers almost always have a job.

The data also seems flawed for another reason. 39% cite job hopping as the biggest issue, while 31% point to lengthy unemployment. One would think that the gap between these two numbers should be much greater. In my experience, a candidate that has been unable to get a job for over a year probably has more serious marketability issues than someone who was able to get hired twice in a year. There could be countless extenuating circumstances to either situation, of course.

A few thoughts on job hopping and the alternative.

Extreme longevity at one company can be viewed as a detriment in a job search (worse than job hopping)

20th century hiring managers viewed your 15 years at COMPANY as a sign of employee loyalty, while 21st century managers feel that if you were any good another company would have hired you away by now. I typically consider extended stays (>10 years perhaps) with one employer as a potential challenge to overcome for a job seeker in today’s tech market. Making a series of moves that allowed you to progress your career and skills will often be viewed more positively than stagnating in one role for an extended period.

Don’t get fired

Job hoppers that lost jobs due to a documented and significant reduction in force or company closing shouldn’t have too many problems, as they aren’t viewed as true job hoppers (rather victims of circumstance). Those that made multiple moves to pursue better opportunities will only be negatively impacted if they are not staying in jobs long enough to improve their skills and to accomplish something valuable. Having a pattern of being fired, even only twice, is where the major employability problem lies for job hoppers.

If your performance is a known issue and you resemble a job hopper, find a new job before they have a chance to fire you.

Have at least one or two stints worthy of highlighting

One of the problems with making quick moves is that you often don’t have enough time to do anything worth putting on a résumé. As an exercise for writing this post, I looked back at the résumés of the candidates I’ve placed in the past two years. The results were telling.

Only about 5% of the candidates I placed had been in their current job for more than three years at the time of placement, and most had been in their past two jobs for less than two years each. Almost all of them, however, had an impressive stint of three to six years at a company within the last decade with obvious accomplishments. The sample size isn’t significant enough to call this a study, and my client base tends to be small companies that are probably less likely to exclude candidates solely based on some jobs per year metric.

It appears that candidates who have had two or three jobs over a short period of time will be forgiven for job hopping if they had at least one stable stretch in the recent past. Just as a former league MVP should be able to find a spot on a team’s roster even after a couple sub-par seasons, candidates that have somewhat recent success stories will overcome the stigma of job hopping.

Job Tips For GEEKS: The Job Search DRM free ebook is available for $9.99 on most platforms. See the book’s page for details and a free sample.

July 23, 2013

Why You Can’t Work For Google

Many new entrants to today’s technology job market are obsessed with the handful of high-profile companies that set the trends in the industry, and the next generation of software engineers seem to think that the only companies worth working for are Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, Yahoo, Twitter, and Amazon. Software development has become both a celebrity culture (where companies and their CEOs are the stars) and an oligarchy in the eyes of recent graduates and teens, who set their sights on employment with this small number of firms. Young developers in foreign countries appear to be particularly susceptible to this hyperfocus on a tiny segment of the hiring market. If you don’t know how widespread this is, I’d suggest a visit to Reddit’s CS Career Questions section to see what people are asking.

When Yahoo changed their remote work policy the web exploded in debate around the value of remote employees, and the more recent news around Google dismissing GPAs, test scores and answers to Fermi questions made many tech companies reconsider their hiring procedures. Not a day passes where a piece on one of these companies doesn’t hit the front page of most major news sites. A cottage industry has erupted with authors and speakers providing guides for aspiring engineers to create résumés, land interviews and answer technical questions to get jobs specifically at these companies. The focus seems to be less about becoming skilled and more about being attractive to a specific subset of employers.

These companies are glamorized amongst budding engineers much like Ivy League and top-tier schools are with high school students, and the reason you probably won’t work for Google is the same reason you probably didn’t go to MIT. Because they are highly selective, and they simply can’t hire everyone.

Of course some of you can and perhaps will work for Google and the other companies listed here, just as some of you may have attended top universities. But the majority of you us won’t – and that’s OK. Follow your dreams, but be realistic about the outcome.

So here comes the good news! Beyond Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo and Amazon, there are hundreds of awesome places to work that are highly regarded by engineers the world over, and most people outside the industry (and many inside) haven’t heard of most of them. Experience with these shops, much like the above list, will get you noticed. Companies like Netflix, LinkedIn, Salesforce, eBay and GitHub are well-known but not typically mentioned in the same breath as the top celebrity firms, though they certainly could be. I’d venture that most college CS majors haven’t even heard of 37signals or Typesafe, where smaller teams are doing work that is regularly recognized by the engineering community.

And again the bad news. You probably won’t work for these companies either. For most of the world, these are still reach schools that employ relatively few. Although they may not be held by the general public in the same esteem as that list up top, they are incredibly selective, and most in the industry will view the difference between this group and the Googles as incredibly slim.

And now for some more good news. Beyond the lists of companies above are thousands of great places to work that I guarantee you have never heard of. These may consist of startups that fly under the radar or smaller specialized technology companies that serve a niche market. They could be the development groups for major banks or 25 year old mom and pop shops that have an established customer base and solid revenues. Game developers, ecommerce sites, consulting firms, robotics – the list goes on.

In almost every city, this group is the one that employs the overwhelming majority of engineers. This is where most of us will likely end up – a company that you will surely need to describe and explain to your parents and significant other.

In the city where I focus my business (Philadelphia) and run our Java Users’ Group, we have some Googlers and I’ve known engineers who have worked for Amazon, Yahoo, and Apple. And I know many many others who either turned down offers or likely could have joined those companies, but chose instead to work somewhere else. Just as some students may reject the offer from the top-rated school to stay closer to home or to accept a more attractive scholarship package, many of the world’s top engineers simply don’t work for Google or Facebook, or anywhere else in the Valley for that matter.

Philadelphia is by no means Silicon Valley, yet there is a fairly robust startup scene and a large number of software shops that are doing valuable work. Over the past 15 years I’ve worked with hundreds of Philly companies to hire engineering talent, and 99% of these places would be unknown to the typical developer. I almost always have to describe my clients to potential candidates, as most of these shops have not built a reputation yet, and these are firms ranging from 20 to perhaps 20,000 employees. And the vast majority of them are great environments for technologists where developers work alongside at least a few top engineers that could (and some that did) pass the entrance requirements for the Googles and Facebooks of the world.

All the great engineers in the world aren’t in the Valley, and they don’t all work for Google. This fact is obvious to most, but fewer than I’d expected and hoped. If that is the goal, go after it. The rest of us will be here if it doesn’t work out.

Job Tips For GEEKS: The Job Search DRM-free ebook is available for $9.99 – more info here.