Dave Fecak's Blog, page 7

July 22, 2014

How to Evaluate Job Offers

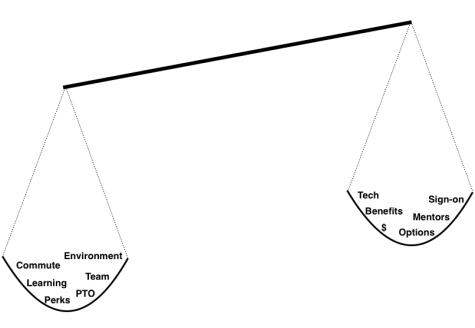

At some point in a career, many will be in a position to decide between multiple job offers from different companies – or at worst having to decide between accepting a new job or staying put. When starting to compare offers, it is common for the recipient to focus on the known quantities (i.e. salary, bonus, etc.) and perhaps a couple additional details that are generally considered more subjective (work environment, technologies).

In order to make a truly wise choice it is also useful to include less obvious factors as well as future considerations, as those generally will have a much stronger influence on career earnings and success. These are harder to predict, but must enter into your decision unless your sole objective is to meet some immediate short-term need.

The easy part

The most common components factoring into gross compensation are:

Cash compensation (salary, bonus, sign-on) – If the bonus is listed as guaranteed, the figure can be lumped into salary. Most bonuses are not guaranteed, but rather are tied to personal and/or company goals being met. Some firms or individual employees are willing to provide data on bonus history. Sign-ons are used to sweeten an offer or to rectify a potential cost the new hire would incur by leaving their job, such as an unpaid bonus.

Healthcare premiums and contributions – Offer letters typically do not list employee out-of-pocket insurance cost, and personal circumstances may weigh heavily on how one values health insurance. Employer contribution can vary from 50-100% while other companies offer employee-only contribution (no contribution towards spouse/partner/child), which can result in a total compensation difference of a few percent.

401k or retirement plans – Employee match and contribution to these plans can be significant. Consider both the dollar amounts and the vesting schedules.

Education reimbursement – If considering a return to school this policy could make a difference.

Paid time off – Although the real value any employee places on time off will vary, the dollar value of each day of PTO can be estimated using a formula.

(Annual salary / estimated annual work hours) x work hours in a day

Many candidates make the mistake of basing their decisions with too much weight placed on base salary. This may be attributed to our emotional attachment to numbers and compensation “milestones” (usually round numbers), the perception of status that results from salary, and the inability of candidates to accurately gather and calculate the details of a comprehensive package.

A friend might tell you about her 100K salary, but how often do you hear someone independently offer up that they pay 10K per year for health insurance and only get one week of vacation?

Additional considerations

The details above are all easily obtained, quantified, and require no interpretation. Everything from this point on will require a bit of investigation as well as some educated guessing.

Expected hours – To put a value on time for offer comparison, a quick calculation to convert salary into dollars per hour can be a telling figure. All else being equal, that 80K offer with a 40 hour work week is more per hour than the 100K offer at 55 hours. Estimates of work hours may not be accurate, so multiple data sources can help.

Commute time/cost and possibility for remote work – Distance may not be a reliable predictor of commute time or cost, and mundane details such as gas efficiency will quickly add up when you consider the trip is repeated 400+ times a year. Mass transit inefficiencies and delays have a cost to commuters as well. The ability to work remotely, even for one or two days a week, makes some difference.

Travel – This can be viewed as a positive or a negative depending on the worker. Consider any hidden expenses that may not be reimbursed, such as child or pet care costs.

Perks – Company provided phone or internet, gym membership, and office meals/snacks are not things job seekers expect, yet could provide thousands of dollars in value.

Self-improvement budget – Some companies may be willing to foot the bill for training or conferences that the employee would have paid for anyway.

Forecasting and speculation

The most vital characteristics contributing to a job’s long-term value are often hidden and unsupported by reliable data. Establishing the present day value of any one job is somewhat complex, and trying to forecast future values requires speculation.

Future marketability – This is a key factor in career compensation, yet is often overlooked when the temptation of short-term gains are presented. The consideration of future marketability is most critical for new grads or junior level employees, who are (unfortunately) often in debt and easily influenced by short-term gains and cash compensation. What skills will be obtained in a job, and to what extent will these new skills increase market value? Will having a company’s name on a résumé (whether by associated prestige or number of direct competitors) create some additional demand for services? If a goal is to maximize lifetime earnings, one could theorize that a year of unpaid work at a place like Google or Facebook is preferable to two years of paid work at many other companies.

Promotions and raises – Job offers only include starting salary/title. How, and how often, does a company evaluate employees for salary increases, and what amounts might be expected for performers? Do they tend to promote from within or hire from outside? Is there a career path and is there a point where compensation plateaus?

Stress and satisfaction – It’s impossible to place a hard value on work stress or job satisfaction, and the amount of either is difficult to predict. Satisfaction, work/life balance, and stress can impact both health and productivity, which could also contribute to marketability.

Stock/stock options – The number of factors that influence the potential value is too long to list. Vesting schedules may have substantial impact on perceived value if a long tenure isn’t expected.

Environment, team, management – Companies try to make a strong positive impression during interviews, but that image doesn’t always accurately reflect day-to-day operations. Younger workers should place considerable weight on whether there are team members to learn from and mentors who are both available and willing to guide. Employees with long tenures will have insight, though the opinion of more recent hires may be more relevant to anyone considering an offer.

Conclusions

Job change decisions are complex, and tough choices usually end up coming from the gut. The immediate results of a choice are easily identified and quantified, but the more important long-term ramifications require research, interpretation, and a bit of conjecture. When combining all of the smaller elements of a compensation package, the highest salary will not always be the most lucrative offer.

June 27, 2014

So You Want to Use a Recruiter Part III – Warnings

This is the final installment in a three-part series to inform job seekers about working with a recruiter. Part I was “Recruit Your Recruiter” and Part II was “Establishing Boundaries”

In Part II, I alluded to systemic conditions inherent to contingency recruiting that can incentivize bad behavior. Before proceeding with warnings about recruiters, let’s provide some context as to why some recruiters behave the way they do.

Agency recruiters (AKA “headhunters”) that conduct contingency searches account for most of the recruiting market and are subsequently the favorite target of recruiter criticism. These are recruiters that represent multiple hiring firms that pay the recruiter a fee ranging anywhere from 15-30% of the new employee’s salary. This seems a great deal for the recruiter, but the downside of contingency recruiting is that the recruiter may spend substantial time on a search yet earn no money if they do not make the placement.

Contingency recruiters absorb 100% of the “risk” for their searches by default, unlike retained recruiters who take no risk. Hiring companies can establish relationships with ten or twenty contingency firms to perform a search, with each agency helping expand the company’s name and employer brand, yet only one (and sometimes none) is compensated. When we combine large fees with a highly competitive, time-sensitive demand-driven market, the actors in that market are incentivized to take shortcuts.

Please don’t confuse these revelations as excuses for bad behavior. Recruiters who either do not understand or choose to ignore industry ethics make it much more difficult for those who do follow the rules. I provide these warnings to expose problems in a secretive industry, with hopes that sunlight will serve as disinfectant.

All recruiters won’t act this way. Many will. Keep these things in mind when interacting with your recruiter.

Your recruiter may send your résumé places without your knowledge - To maximize the chances of getting a fee or to utilize your desirable background as bait to sign a prospective client, recruiters may shop you around without your consent. This only tends to cause issues when the recruiter sends your résumé somewhere that you are already interviewing.

REMEDY: Insist that your recruiter only submits you with prior consent (in writing if that makes you feel more comfortable).

Your recruiter may attempt to get you as many interviews as possible, with little consideration for fit - This sounds like a positive until you have burned all your vacation days and realize that over 50% of your interviews were a complete waste of time. This is the “throw it against the wall and see what sticks” mentality loathed by both candidates and employers.

REMEDY: Perform due diligence and vet jobs before agreeing to interviews.

If you reject a job offer, the recruiter may take questionable actions to get you to reconsider – No one can fault a recruiter for wanting to promote their client when a candidate is on the fence. That is part of the recruiter’s job. Recruiters cross the line when they knowingly provide false details about a job to allay a candidate’s fears. A recruiter may call a candidate’s home when the recruiter knows the candidate isn’t there in an attempt to speak to and get support from a spouse or significant other. The higher the potential fee, the more likely you are to see these tactics.

REMEDY: If you have questions about an offer that don’t have simple answers, such as inquiries about career path or bonus expectation, get answers directly from the company representatives. When your decision is final, make that fact clear to your recruiter.

If you accept a counteroffer, the recruiter will attempt to scare you - Counteroffers are the bane of the recruiter’s existence. Just as the recruiter starts counting their money, it’s swiped at the last possible moment – and just because the candidate changed their mind. Recruiting is a unique sales job, in that the hire can refuse the deal after all involved parties (employer, new employee, broker) have agreed to terms. Sales jobs in other industries don’t have that issue.

When a counteroffer is accepted, expect some form of “recruiter terrorism“. In my opinion, this is perhaps the most shameful recruiter behavior. Recruiters have been known to tell candidates that their career is over, they will be out of a job in a few months, and that the decision will haunt them for many years to come. All of those things may be true in some isolated instances, but plenty of people have accepted counteroffers without ill effects. I’ve written about this before, as it’s important to understand the difference between the actual dangers of counteroffer acceptance and the recruiter’s biased perspective.

REMEDY: Consider any counteroffer situation carefully and do your own research on the realities of counteroffer, while keeping in mind the source of any content you read.

You will be asked for referrals, perhaps in creative ways – Recruiters are trained to ask everyone for referrals. This was much more important before the advent of LinkedIn and social media, when names were much more difficult to come by. Candidates may expect that recruiters will ask “Who is the best Python developer you know?”, but they may feel less threatened by a recruiter asking “Who is the worst Python developer you know?”. Again, we shouldn’t blame recruiters for trying to expand their network, but if the recruiter continues to ask for names without providing any value it’s clearly not a balanced relationship.

REMEDY: Give referrals (if any) that you are comfortable providing, and tell the recruiter that you’ll keep them in mind if any of your associates are looking for work in the future. Whether you act on that is up to you.

If you list references they will be called (and perhaps recruited) – When a candidate lists references on a résumé, it’s an open invitation to recruit those people as well. If your references discover that you leaked their contact information indiscriminately to a slew of recruiters and that act resulted in their full inbox, don’t expect them to volunteer to serve as references in the future.

REMEDY: Never list references on your résumé. Only provide references when necessary, and ask the references what contact information they would like presented to the recruiter.

You will receive continuous recruiter contact for years to come, usually more often than you’d like - Once your information is out there, you can’t erase it. Don’t provide permanent contact details unless you are willing to field inquiries for the rest of your career.

REMEDY: Use throwaway email addresses and set guidelines on future contact.

Recruiters get paid when you take a job through them, regardless of whether it’s the best job choice for you – This is a simple fact that most candidates probably aren’t conscious of during the job search. There are three potential outcomes – you accept a job through the recruiter, you accept a job without using the recruiter, or you stay put. Only the first outcome results in a fee, so the recruiter has financial incentive first to convince you to leave and then to only consider their jobs.

What type of behavior does this lead to? Recruiters may ask you where you are interviewing, where you have applied, and what other recruiters you are using. Some may refuse to work with you if you fail to provide this information. They may provide some explanation as to why this information is vital for them to know, but the reason is only the desire to know who they are competing against and to have some amount of control. The more detail you provide, the more ammunition the recruiter has to make a case for their client.

REMEDY: Always consider a recruiter’s advice, but also consider their incentives. Provide information to recruiters on a need to know basis and only provide what will help them get you a job. Specifics about any other job search activity are private unless you choose to make it known.

Recruiters have almost no incentive to provide feedback - Many job seekers wonder why agency recruiters often don’t provide feedback after a failed interview. Of my 60+ articles on Job Tips For Geeks the most popular (based on traffic coming from search engines) is “Why The Recruiter Didn’t Call You Back“, so it’s clear to me that this is a bothersome trend. Once it becomes clear that you will not result in a fee, your value to the recruiter is primarily limited to the possibility of a future placement or a source for referrals.

Interview feedback is valuable to candidates, and job seekers that commit to interviews deserve some explanation as to why they were not selected for hire.

REMEDY: Set the expectation with the recruiter that you will be interested in client feedback, and ask for specific feedback after interviews are complete.

June 24, 2014

So You Want to Use a Recruiter Part II – Establishing Boundaries

This is the second in a three-part series to inform job seekers about working with a recruiter. Part I was “Recruit Your Recruiter” and Part III is “Warnings”

Once you have identified the recruiter(s) you are going to use in your job search, it is ideal to immediately gather information from the recruiter (and provide some instructions to the recruiter) so expectations and boundaries are properly set. All recruiters are not alike, with significant variation in protocol, style, and even the recruiter’s incentives.

The stakes are high for job seekers who entrust someone to assist with their career, but it’s important to keep in mind that a recruiter stands to earn a sizable amount when making a placement. For contingency agency recruiters who make up the majority of the market, the combination of large fees and competition can incentivize bad behavior. More on this in Part III.

As a recruiter, I find that transparency helps gain trust and is necessary to establish an effective professional relationship. Candidates should realize that I have a business and profit motive, but I also want my candidates to understand my specific incentives so they can consider those incentives during our interactions. The negative reputation of agency recruiters makes this transparency necessary, and honest recruiters should have nothing to hide.

Some recruiters will be more open than others, and the recruiter’s willingness to share information can and should be used as potential indicators of the recruiter’s interests. A recruiter must be able to articulate their own incentives, and be willing to justify situations where full transparency is not provided.

To establish boundaries and set expectations, there are several topics that need to be addressed.

What you need to know

The recruiter’s experience – Hopefully you vetted your recruiter before contact, but now is the time to verify anything that you may have read. Confirm any claimed specialties.

How the recruiter is paid for any given client – Whether or not recruiters should reveal their fee percentages is debatable, but job seekers certainly have the right to know how fees are calculated. Why is this important? Some fees may be based on base salary only while other agreements may stipulate that a fee includes bonuses or stock grants. If the recruiter is providing advice in negotiation, it’s helpful to know what parts of the compensation package impact the recruiter’s potential fee.

Keep in mind that recruiters often have customized agreements with their clients. When a recruiter is representing you to multiple opportunities, it’s absolutely necessary for you to be made aware of each client’s fee structure. If you sense that your recruiter is pushing you towards accepting an offer from Company A and discouraging you from a higher offer with Company B, knowing who pays the recruiter more helps temper the advice.

The recruiter’s relationship with any given client – Did the recruiter just sign this client last week or do they have a ten year history of working together? Has the recruiter worked with certain employees of the client in the past? This information is primarily useful when considering a recruiter’s advice on hiring process and negotiation, as the recruiter’s familiarity (or lack thereof) could be a contributing factor to getting an offer and closing the deal.

The recruiter should also be willing to share if the client is a contingency search or retained (some fee paid in advance). This information has little impact on incentives, but clients do have a vested interest in hiring from a recruiter on retainer as they already have some skin in the game.

As much detail as possible on any given job being pitched – Some candidates are satisfied with only knowing a job title while others want to know whether a company has a tendency to hire executives from outside or within. Recruiters will have some specific details, but candidates should expect to perform a bit of due diligence as well. If there are certain deal breakers regarding your job search (maybe tuition reimbursement is a requirement for you), it’s the candidate’s responsibility to convey those conditions and the recruiter’s responsibility to clear those up before starting the process.

What you need to express

How and when to contact – If you share all your contact information with a recruiter without instruction, many recruiters will assume they have full access. Recruiters want to establish a solid relationship and may feel the best way to do that is through extensive live contact. An inordinate number of calls to your mobile phone during office hours could tip off managers to your search, which may even benefit the recruiter’s efforts to place you. Set guidelines on both method and time acceptable for contact.

No changes to the résumé without consent – I hear this complaint often, and the solution for many is a PDF. The most common change made is the addition of the recruiter’s contact info and maybe a logo. This is harmless, and designed to ensure that the recruiter gets their fee if the résumé is found three months later and the candidate is hired.

There are many anecdotes about recruiters adding or subtracting details from a résumé, which is a different story. It’s entirely unethical for a recruiter to insert skills or buzzwords without consent.

No résumés submitted without permission - To prevent a host of potential issues, be explicit about this. A recruiter who is not given this directive may feel they have carte blanche and might submit your résumé to a company you are already interviewing with, a former boss you didn’t like, or any number of places you don’t want your résumé going.

Need to provide client names before submittal – See above. There are somewhat unique scenarios where companies request anonymity before they establish interest in a candidate, but these are extremely rare cases. It is not only important to know that your résumé is being sent out, but also where it is going.

Only want to be pitched jobs that meet your criteria – This is more about saving time than anything else, but contingency recruiters playing the numbers game may try to maximize their chances of making a fee on you by submitting you to every client in their portfolio. The result is wasteful interviews for jobs that you are unqualified for or that you would never have accepted in the first place.

Recruiters aren’t mind readers, so you’ll need to be specific. If you are limiting your search to specific locations and types of jobs, establish those parameters early and ask to be informed only about jobs that fit.

Expectation of feedback, preferably actionable – One of the biggest complaints about recruiters is that they suddenly disappear after telling you about a job or sending you on an interview. There are multiple reasons for this, some understandable and others less so. Asking the recruiter when you should expect to hear feedback and sending prompt emails after interviews should help you gather valuable information about what you are doing well and where you could use some work.

Recruiters don’t want to hurt a candidate’s feelings and may filter their feedback, but the raw information is more useful and often actionable. Ask for a low level of filtering.

Follow this blog (see right margin) or @jobtipsforgeeks on Twitter to receive notifications about new posts, including Part III of this series.

June 20, 2014

So You Want to Use A Recruiter Part I – Recruit Your Recruiter

This week I read an unusually high number of articles (and the comments!) about recruiting. Although most of the discussion quickly turns to harsh criticism, there are always a few people wondering the best ways to find a decent recruiter to work with and what to do once they have established contact.

Some recruiter demand stems from candidates looking to relocate into areas where they have no network, while others just want to maximize their options and feel they may benefit from the services provided by an agency recruiter. Regardless of your reasons for seeking out an agency recruiter, first you have to find one.

Finding a Recruiter

There are three reliable methods to getting introduced to a recruiter.

Referral

This is the best method for most, as being introduced by a contact can have unexpected benefits. To maximize those benefits, you must consider the source of your referral.

If the recruiter has a great deal of respect for the person introducing you, you are likely to be given some immediate credibility and favorable treatment due to that association. Unfortunately the alternative is true, and if you are referred by someone the recruiter does not respect it may be assumed that you are not a strong talent. When asking for recruiter referrals it is wise to start with the most talented people in your network.

Your network does not have to be the only source of referrals, particularly if you are looking for a recruiter in an area where you have no network. User group and meetup leaders are frequently contacted by recruiters and one should expect group leaders to be knowledgeable of the local market. Even a random email to an engineer in another location could result in a solid lead.

Let the recruiter find you

If I had a nickel for every time I heard technologists complain that they aren’t hearing from enough recruiters, I’d be poor – though some voice frustration that they don’t hear from the ‘right ones‘. Increasing your visibility will attract recruiters who may or may not be the ones you’d want, but it helps establish a pool for evaluation to choose who is worthy of a response.

To maximize your chances of being found and contacted, you need to consider how recruiters will find you. The obvious place is LinkedIn, and spending a few minutes fixing up your profile will help.

Keywords and SEO concepts as well as profile ‘completeness’ should be your focus. (further reading on this) Recruiters are likely to be searching for combinations of keywords from their requirements, usually with some advanced search filters based on location, education, or experience. Completeness matters.

Some recruiters search Twitter and the other standard social sites as well. If you have a profile anywhere, just assume that a recruiter might find it and optimize keywords similarly.

Keep in mind how easy or difficult it is for people to contact you once you’ve been found. Just because I see your LinkedIn profile or Google + account doesn’t mean I can contact you. Many professionals create an email address (maybe currentemail-jobs@domain) strictly for recruiter correspondence and include it in their LinkedIn profile and other social pages.

Another option is to get discovered on job search sites like Indeed, Monster, and Dice. These are frequented by active job seekers, and some recruiters may view your posting there as a somewhat negative signal. Be warned that posting personal information on these sites means that those phone numbers or email addresses will live forever in the databases of recruiters everywhere.

PROTIP: Those that complain about recruiters often cite laziness in the initial contact. This may be evidenced by an obvious cut and paste or clear signs that the recruiter didn’t read the bio. If you want to screen out recruiters that don’t do the work, put up a barrier to weed out the lazy. This page that uses scripts in Python and Haskell to hide an email address is perhaps my favorite, but there are other less clever ways if you want to set the bar lower than the ability to cut/paste code into a compiler.

Search

Recruiters search for you, and you can search for them. Most recruiters are going to be easiest to find on LinkedIn due to the amount of time they spend there.

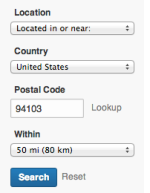

1 - Click on Advanced at the top of the main LinkedIn screen (just to the right of the search bar)

2 - On the upper left side of your screen you will see several fields. Make sure you are doing a People search (and not a Jobs search).

3 - Type ‘Recruiter’ and other terms specific to you in the Keywords field. Try ‘developer‘ or ‘programmer’ and a term that a recruiter might use to brand you, such as a language. Recruiters often populate their LinkedIn profiles with the technologies they seek, not unlike job seekers trying to catch the automated eye of a résumé scanning system.

4 - Enter the zip code of the area where you wish to find work and consider setting a mile limit. Some recruiters work nationally, but local knowledge goes a long way if you are seeking to work in one area. Once you start entering the code, a menu appears. Depending on where you live, you may want to select 25 or 50 miles (probably good for northeast or mid-Atlantic US), or up to 100 miles (for midwest).

5 - On the right, make sure you have 3rd + Everyone Else checked under Relationship. This will maximize your results, particularly if your LinkedIn network is small.

6 - Click Search. Repeat, and vary the words you used in Step 3. You should see a few different faces as you adjust the keywords, and you’ll also see whether you have connections in common with those in your search results.

Twitter is another decent option. Make sure you are searching People (and not Everything), and pair up the word recruiter with some keywords and/or geographic locations. You’ll get numerous hits in most cases, and should only have to do a bit of legwork to find their bios.

In addition to being able to find recruiters on social sites, you can use job boards as well. If you search for a Ruby job in New York City, you may quickly find that several of the listings are posted by one or two recruiting companies. Look into those firms to see if they have a specialty practice.

Search engines might be a bit less useful and are likely to turn up the same listings found on job boards.

Evaluating a Recruiter

Once you have found a pool of potential recruiters, you need to decide which ones to contact. Most job seekers want a recruiter that can provide quality opportunities, has deep market knowledge, can leverage industry relationships, and will navigate issues in the hiring process.

What criteria should we use in the evaluation?

Experience

Just like most disciplines, in recruiting there is no substitute for experience. It takes time to develop contacts and to learn how to uncover potential land mines. Extensive education, recruitment certifications, and training programs don’t get you a network or prepare you for handling unique situations.

Early in my career I know I made many of the mistakes that technologists complain about, and I didn’t have a solid network or steady clients for at least five years. At a certain point in your recruiting career you may not have seen it all, but it’s rare that you are surprised by an outcome.

Focus and Expertise

Experienced recruiters that have spent little time in the industry may be good for general job search advice or negotiation, but can’t provide full value. Look for a consistent track record of years in your field and geography of your search. Talking to a few generalists will make the specialists stand out.

Relationships/Clients

Since recruiters aren’t paid by you and differ from a placement agency, it’s important that the firm has client relationships. Most firms do not advertise their client names which can make it difficult to discover the strength of an agency’s opportunities. The descriptions themselves could be enough to convince you that the agency has attractive clients. Agencies with solid relationships may reach out to past clients and contacts when they don’t have a position that is a clear fit for your background.

Personality fit

Being that an agency recruiter is going to be representing you to companies and even advocating and negotiating on your behalf, it’s important that you get along. You don’t need to be best friends, but someone who dislikes you is unlikely to fight for your best interests.

A ten minute call should give the insight you need to make the decision. Ask questions about their experience and pay attention to the types of questions they ask you. If they don’t dig into your goals and objectives, they probably aren’t concerned with finding a good fit for you.

May 30, 2014

How I Learned To Appreciate Job Hoppers

The possibility of being labeled a job hopper is still a concern for many in the technology world. This fear is often unreasonable and is primarily a function of traditional and antiquated employment concepts being extended into an economy where they likely don’t belong. In other words, don’t take career advice from your parents.

When I first started recruiting software engineers during the late 90′s dot-com boom, I was advised by more senior coworkers to avoid wasting time speaking with job hoppers. People who frequently switched employers were perceived as high risk for companies who needed to invest significant time and money into making new hires effective, only to lose them shortly thereafter. Recruiters were afraid a placement might not even reach their guarantee period.

The economy and workforce as a whole were undergoing rapid and dramatic changes, but long-established preconceptions about employment were somewhat slower to adapt. Linear career paths were the expectation, and the prevailing practice was still to promote our best engineers into management without regard for their leadership potential or soft skills. Company loyalty was still a strong emotional factor that resulted in long tenures.

This new well-funded software startup ecosystem siphoned talent from large and established companies, with engineers leaving behind stability and pensions for modest salaries and stock options that provided get-rich-quick possibilities. Once the big firm pool dried up, they cannibalized and created a class that appeared to many as mercenary startup engineers. This was a class of job hoppers, but their motivations (and subsequently their character) were often misrepresented or misunderstood.

Were they mercenaries?

There were (and still are) a fair share of individuals that chase short-term gains by making job decisions based almost exclusively on numbers. Accepting offers from the highest bidder every time will work for some, but to maximize lifetime earnings (ignoring job satisfaction here) the top offer may not always be the best path. Was this new class of startup job hoppers driven primarily by financial gain?

For most, I believe the answer was no.

Due to the competitive nature of the industry and basic economic principles of supply and demand, most job changes result in at least some small increase in compensation. It would be easy to assume that engineers accepted these offers based on the higher package, but for most the desire for change was probably attributed to the need to build new things.

It’s no coincidence that we find many of the startup job hoppers went on to become independent consultants and contractors, where there is no stigma attached to short stints. We could again make the argument that they were driven to consulting by high rates, and some certainly were, but many point to their preference to finish projects and then move along.

Engineers left many of their startup jobs after a year or two because they had built what they were hired to build, were drawn to the job based on the opportunity to create something, and were much less enthusiastic about maintaining it. This desire to build is a characteristic valued by managers who emphasize getting things done, so they can hardly fault them for leaving when there is little left to do.

Job hopping vs the alternative

Of course, the opposite of job hoppers are employees who remain in the same job for inordinate tenures. Most industries have historically interpreted a long stay with the same employer as a positive sign and an asset for one’s candidacy. In technology this is typically no longer the case. In recent years the adage “Do you have ten years of experience or one year of experience ten times?” has been applied to those who seem more driven by company loyalty and stability than career self-interest.

There was a time when it was more difficult to find new work without a highly stable work history. In today’s technology market, I would make the argument that a career characterized by one or two lengthy employment stints is actually less marketable to the majority of tech employers than your standard job hopper. Discrimination against those with long tenures is often wrongfully attributed to ageism or an overqualified candidate, where the root of the discrimination is a belief that work variety produces better engineers. As a recruiter, removing the appearance of dust or stagnation is a major challenge when working with candidates coming off a long tenure.

Positive vs negative hopping

It’s important to note that there are different kinds of job hoppers, and the picture painted thus far has been mostly of those viewed favorably by the industry. These are people who make self-interested decisions to move once they have maximized their career gain from an opportunity. Usually this meant the ability to gain a new experience, such as learning a skill or building a product. To lose any potential negative stigma associated with job hopping, one should have a list of accomplishments and projects that were seen to completion. That doesn’t mean there can’t be failings along the way, but successful job hoppers have a track record of being hired for a purpose and meeting or exceeding the expectations of the employer. They should also be able to explain the motivations behind each move and why it was right for their career at that time.

The job hoppers that are likely viewed in a negative light often lack both accomplishments and justifications for their transitions, and can often have résumé gaps that aren’t easily explained. They may have a history of abandoning efforts before completion, or are consistently wooed by new employers regardless of current project status. Unemployed job hoppers with these backgrounds eventually have a difficult time in job search.

Conclusion

Attitudes towards those that frequently change jobs have transitioned as the economy has changed, and companies have more realistic expectations about their employees acting in their own self-interests. The stigma around job hopping in technology has almost been eliminated at smaller companies, particularly for candidates who have a solid list of accomplishments and are able to articulate a history of positive career choices.

May 20, 2014

How Ben Accidentally Became a Developer

In early April I received a message from Ben, delivered to my Reddit account.

I’ve been reading /r/resumes for, well, the whole time I’ve been actively looking for another job. I’ve noticed your comments on other posts and respect your opinion. Even though I’m not a “programmer” per se, I do enjoy reading your site and appreciate the time you take to help folks like me who are trying to make the best impression possible.

Ben wanted some advice on his résumé and career prospects in technology, and he wrote a quick bio. He earned a degree in religion and worked in that field for seven years before deciding that his passion was for technology. During his tenure in the church he dabbled in web development and learned to solve basic networking and hardware issues to reduce the church’s technology expenses. He resigned his church position to pursue entry-level roles, and ended up spending a year in retail before eventually being hired as a Junior Computer Technician.

After spending three years in the technician role, Ben asked his manager for additional responsibilities. He was already performing light systems administration tasks for their small office, and was then entrusted to write a web application. Ben taught himself PHP, JavaScript, and SQL. The web app he built became a major revenue source for his company and a highlight of his career.

Ben, on paper

After learning about Ben’s work history, I reviewed his résumé. The two sentence profile atop his résumé mentioned troubleshooting, managing hardware and software, vendor selection and training. There was no mention of programming experience.

Below the profile was a listing for certifications. None of his certs were truly relevant to programming.

His experience section was next. The first role listed was Systems Administrator, which had descriptions of his accomplishments in that role.

I was now halfway down the page and I have seen nothing about what he saw as his most valuable professional accomplishment. And then there it was – Web Developer. He had duties in both sys admin and development, and chose to list the sys admin experience first.

His technical skills section led with several operating systems, servers, and virtualization tools. Below that, a mere two lines from the bottom of the résumé (just above his degree), he listed programming languages.

“…not a programmer, per se…”?

After I finished reading the résumé, I thought back to his comment from the original Reddit comment. “Even though I’m not a ‘programmer’ per se…” At this point it was hard to tell if Ben would be more marketable (or happier) as a sys admin or a developer, so more information was required.

Ben then sent me a random email to tell me about his blog, which he had recently converted from WordPress to Octopress and had subsequently picked up some Ruby along the way. I checked it out and saw he had a couple small GitHub repos. This was all news to me. I asked if he had any other programming experience he was hiding.

It turns out he had done some freelance front-end web development work for a bit. He added that he had also contributed to the development of a template that was adopted by WordPress as a stock theme.

Ben might not have considered himself a programmer, but I expected others would disagree.

The Intervention

I sent Ben an email suggesting he focus 100% of job search efforts on finding a development role, and that his experience should qualify him for intermediate level slots. Ben responded that he had been reluctant to seek programming positions because he’d been doing that work for the least amount of time, but acknowledged that he’d probably be happier (and better compensated) as a developer. We worked together over the course of a couple days to rewrite his résumé, which emphasized his coding accomplishments.

Results

Within five days of our first contact, Ben had a couple interviews lined up for web development positions. Fifteen days later Ben accepted a new job offer as a developer, which came with a 60% increase from his prior salary.

Ben now describes himself as a “Full-stack web developer” on his blog.

April 11, 2014

How to Level Up

I regularly hear from and read about technologists in a career rut. Unless one is both lucky and adept at predicting the future, experiencing some temporary stall can happen to professionals at any career stage. It may be the feeling of being stuck in an unchallenging role, feeling burdened by an undesirable skill set, or trapped in a company that seems difficult to escape.

Career stagnation in technology could be defined as a prolonged period characterized by limited project variety, no advancement or even lateral movement, few tangible accomplishments, and little exposure to any emerging trends. Some managers are aware that workers in these situations generally leave, so the managers may proactively try to satisfy staff by shuffling teams and providing more interesting tasks. Many managers have to focus on deliverables and may give little thought to the career development of their charges, perhaps throwing money at retention problems instead of providing challenges.

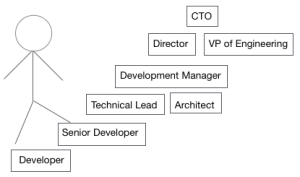

To “level up” could mean a promotion into management or technical leadership, a new start at a firm with increased opportunity, a role with autonomy and decision-making responsibility, or the ability to make significant improvements to skills and marketability. People that think about the leveling up concept often know what they want (or sometimes what they don’t want), but don’t necessarily see the best paths to get there.

Leverage the skills you have to get the skills you want

Most professionals view their current skills as a means to getting new jobs, but it’s useful to also think about skills as the key to acquiring other new skills. This tactic is most relevant when a skill set is dated and a previously strong marketability level is now questionable. Some will attempt to make a clean and immediate break from their old technologies or responsibilities into the new, usually with mixed results.

As an example, many COBOL programmers tried to enter the stronger Java job market following Y2K. Some applied to jobs with no Java experience hoping their COBOL years would be deemed transferrable, while others pursued certifications and self-study to ideally be viewed as a somewhat “experienced” hire. One overlooked strategy was to approach companies that were using both COBOL and Java in some capacity, with the understanding that the candidate was willing to write COBOL if provided the ability to also work with Java.

Most job seeking technologists have at least one ability that will help them contribute immediately to any other team or organization. It could be an obscure technical skill, leadership experience, or domain knowledge. Even if the skill is not something the person wants to use forever, it could be a key component to getting hired. Try to identify companies that may be looking for some specific expertise you can provide, even if it isn’t the most attractive tool in your bag, and be transparent about your willingness to do that less desirable work in exchange for exposure to skills that are in demand.

DIY

For those in the most stagnant of technical environments, taking on independent projects or open source may be the best way to gain experience and increase marketability. It’s usually preferable to learn new things on the job (because money), but being proactive about your career and keeping abreast of current marketable technologies will also show initiative to potential employers. The level up from personal projects almost always comes from an employment change.

Sometimes to level up you need to take a step back – or sideways

Careers aren’t always linear, and the expectation that trajectory needs to follow a strict continuous and incremental level of responsibilities is perhaps naive and potentially dangerous. Job seekers are often prone to placing too much weight on a position’s salary or (gasp) title without fully considering the position’s potential opportunity as it relates to future marketability and career development. Somewhat frequent movement between jobs is accepted in our industry, so positions can be viewed as stepping stones to future opportunities.

When evaluating new roles, whether with a current employer or another firm, imagine what a three or four year tenure in that role at that company will look like on future résumés. Will the skills likely to be acquired or improved in that role be marketable and transferrable to other firms? Accepting positions that come with lateral responsibility and compensation is usually a wise long-term decision when provided a more favorable learning and growth environment.

March 27, 2014

Homakov: Story of a White Hat

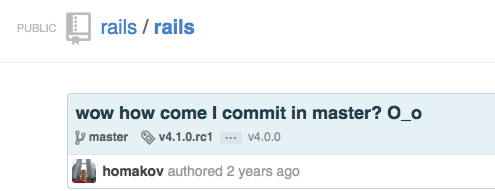

In early March 2012, a Russian programmer one month shy of his 19th birthday emerged on the radar of the software world via one “simple” commit that startled both the Rails and GitHub communities.

The exploited vulnerability was known to many in the community, so discussion about the controversy gravitated towards GitHub’s failure to properly protect repos and the potentially insecure default settings of Rails. The attention drawn to mass assignment served as a beneficial public service announcement to other Rails users, although the delivery method put off many developers as well as GitHub admins who quickly suspended (and just as quickly reinstated) the account. It was all over within a few hours, but Homakov had “arrived”.

Who is this guy?

Egor Homakov grew up in Saransk, a small city of 300,000 residents that sits 400 miles east of Moscow and somewhere deep within Ukraine on a Risk board. He dabbled with Delphi as a teenager to learn how programs worked, and later Pascal. His GitHub dates to 2009, oddly enough on New Year’s Eve. After initially struggling to understand programming concepts, his self-study turned a corner when he transitioned to web apps. Homakov dropped out of university before completing a year, which he admits was a risky move for someone in Saransk, but he found the program far too boring to continue.

Homakov initially focused his career on SEO, but when clients were hard to come by he began advertising PHP programming services on SEO forums. When negotiating a proposal to build a simple news management system for an early prospective client, Homakov requested a rate around $10 per hour. The prospect countered with an offer of $30 if the job was done well. This was a significant wage in Saransk, and Homakov distinctly remembers his mother’s pride.

Over the next few years Homakov bounced between employers, with freelancing gigs followed by short stints at European startups in the online payments and travel spaces. Eventually he decided consulting was his best option, and he is now part of the security firm Sakurity which provides penetration testing and code audit services to clients worldwide. The lion’s share of Homakov’s income comes from consulting, with some additional income via bug bounties (including a $4,000 payout from GitHub earlier this year).

Fame or infamy

Although he admits that he knew little about security before the 2012 GitHub hack, Homakov instantly became a polarizing figure. His action was lauded by some who believed the high profile exposure of the vulnerability would benefit the community by raising awareness for other Rails users. Others felt a more private notification would have been more appropriate, not to mention GitHub’s clear responsible disclosure policy in the terms of service. Supporters saw him as some populist hero sparring the Rails elite, while detractors resorted to mocking his broken English and even criticizing his profile photos. Those on both sides surely realized that he could have chosen the black hat route and done something much more malicious with the Rails repo and any others, and could have done so anonymously.

Some soon discovered that Homakov had indeed opened an issue about the mass assignment vulnerability, and only went public when he felt his warning had fallen on deaf ears. Homakov later regretted much of his behavior, and eventually provided a brief public apology to both GitHub and the Rails team. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that GitHub’s bug bounty program launched earlier this year was at least partially influenced by their highly public experience with Homakov.

The most interesting man in tech?

Since leaving Russia, Homakov has become a world traveler. His Tumblr feed reads like a poorly edited and NSFW Frommer’s guide, chock full of selfies and commentary on the livability and food/drink from locations throughout Europe, the United States, and southeast Asia. Sofia, St. Petersburg, Barcelona, Istanbul, New York, Shanghai, and Seoul – all while earning a living and developing a reputation in the security space.

From his writing it is clear that he has an affinity for Asian culture, bright city lights, and beer (not necessarily in that order), while showing no affection for his country of birth. After about a year on the road, Homakov finally settled in Thailand, where he intends on living for a year before picking up for more travel on the spots he has missed on his first world tour. India, Africa, and South America are on the agenda.

He seems pretty funny too. His Twitter feed is peppered with various self-deprecating third person references as well as little gems like this…

And now that he’s showing maturity…

… he seems to have the ear of at least some in the industry.

… he seems to have the ear of at least some in the industry.

Although much of his security research is unpaid and he is far from wealthy, it’s been quite a trip so far. From $30 to $300 an hour, and from Russia to Bangkok with plenty of stops in between – all in two years. He admits he acted irresponsibly, but now calls himself white hat and takes responsible disclosure seriously. As someone who first arrived to the security field conspicuously, Homakov continues to strive for increased credibility and legitimacy from peers in the industry. For many, his work will speak for itself. As he now approaches his 21st birthday, one has to wonder what his future hold.

Author’s Note: This article is a departure from Job Tips For Geeks normal content, but I see value in profiling technologists who have unique careers. I hope to profile others with non-traditional backgrounds and career paths. Feel free to contact me if you feel you fit into this category.

March 25, 2014

Why Hire Older Engineers

Another day, another article about age and technology. The comments of these articles usually escalate into some generational war played out with mythology and anecdotes regarding relative energy levels and productivity, work hours, the value of experience, and general competence. These discussions usually make no progress, while some useful topics are ignored.

As someone who has been around programmers (and ran a Java Users Group) for about 15 years, I often guide senior technologists in marketing their skills. When doing business with clients, I find myself advocating on behalf of older coders regularly. During the first dot com boom multiple six-figure job offers were dealt to anyone at any age who could spell J-A-V-A, but the landscape is much different now.

Most companies I’ve worked with give candidates of all ages a fair shake, although I’ve witnessed some who have been less friendly to industry veterans. For firms that need additional justification for hiring older workers, here are a few additional considerations that may go beyond the more common topics of discussion.

Recruiting – So your efforts to scale your team came to a screeching halt? Inevitably the friends and family network dries up and firms rely on internal recruiters or outside agencies to identify talent. Although young hires may be more connected due to early adoption of social networks, older workers usually come with established professional networks. These contacts are not just other senior engineers, but will also include younger former co-workers. When you consider the costs of recruiting (not to mention the costs of a bad hire), the ability to tap into the network of highly experienced engineers might even justify paying a higher salary.

Beyond just the network a senior engineer may possess, having experienced talent on staff will appeal to young candidates who understand the value of learning and career development. A predominance of junior engineers will typically scare off older applicants, and it’s also likely to be a red flag for some subset of the young. Graduates are typically encouraged to find a career mentor, and they will seek experienced professionals to serve in that capacity.

I generally advise my clients on employing some senior level engineers who are strong coders but will also serve a secondary purpose of attracting other less experienced hires. The term I usually use is “hire magnets“, and those magnets may fit a few different profiles. The magnet could be a recognized authority on a topic, an involved tech community leader, or simply a knowledgeable and charismatic developer who enjoys sharing knowledge.

Fad recognition – Industry experience may give engineers a sharpened ability to sniff out the difference between a passing fad and the genuine article when considering new technologies. This of course isn’t by rule, but once an engineer has seen enough shiny things being hyped by marketers and evangelists it should theoretically become easier to evaluate trends with less bias. Hires with this skill may save a company time, money, and many developer hours.

Less performance unknowns - Older engineers with a documented work history, a list of credible references, and demonstrable work experience should be easier to vet than juniors coming from their first or second job. The ability to rely on past performance to predict the future is a benefit, though never perfect.

Retention/stability – Employee retention is a serious concern and cost for many firms, with demand for talent contributing to turnover. Older engineers and those with families should be less likely to consider relocation for new positions, which limits their other employment options to local or regional opportunities. Although both junior and senior level engineers may have bills to pay, the breadwinner concept changes perspective and may result in satisfied and fairly-compensated developers staying put.

Senior level developers often reach a point where compensation plateaus and money ceases to be an incentive to change jobs. Employees less driven by dollars are surely driven by something. It could be something as simple as proximity to their home or a desire to solve complex technical problems, but competitors are less apt to change these factors and often need to compete with pay.

From my experience, most engineers see fewer significant increases related to job change around their 15th year in the business, and by the time someone reaches that level of seniority it isn’t unusual to have once taken a pay cut. Junior level talent in competitive markets view job change as the most reliable means to salary increases, while the relatively minor compensation differential for senior engineers may not outweigh the uncertainty of a new employer.

Unique situations - There are some scenarios that happen in development shops that are nearly impossible to replicate in a classroom or lab setting, and the ability to face the unexpected comes from being there. This could refer to crisis management when a server goes down, handling difficult customers, or knowing how to navigate office politics. Prior exposure does not guarantee preparedness, but should make the second experience less shocking.

On-the-job learning – Older engineers may now be on their second or third set of platforms and corresponding tools. Developing the ability to learn new languages and tools in a work environment is a skill. It is quite valuable to know how much (or how little) to read before starting a project with an unfamiliar component, or which methods are most effective for you when seeking knowledge.

Any that I missed?

March 7, 2014

How To Succeed in Software Without a CS Degree

This week I was approached by two individuals seeking advice on finding employment in a programming capacity, yet both lacked the traditional standard requirement for entry-level positions – the BS in CS (‘BSCS’). I get asked about entering the industry often, and each scenario has a unique wrinkle.

The most recent candidates were a fresh Ivy League liberal arts grad and a Physics Ph.D. The former had brief hobbyist programming experience and the latter gained light exposure during school. Both are immediately employable in other industries, but perhaps not in the field they now target.

Of course, both may still be able to earn a BSCS (or MS) and take the traditional route. For our purposes here, let’s take that option off the table. For a Ph.D., the thought of additional classes might be hard to swallow, while costs might serve as a barrier for many others.

Non-BSCS candidates are often at a distinct disadvantage when competing with BSCS grads for entry-level positions. It’s becoming more common for CS grads to enter the workforce with multiple internships and code samples to bolster their candidacy. It’s reasonable to assume that typical non-BSCS grads have nothing comparable, in addition to what may be considered a less attractive degree.

One important point to remember is once you’re in you’re in, meaning that the most difficult job search for non-BSCS grads should be the first one. After gaining a bit of experience, your risk factor subsides (assuming you didn’t perform horribly in your first job). After three years no one cares about your major, and after five no one cares about your degree.

What are the common approaches for a non-BSCS grad to break in?

DIY and self-study (AKA GitHub, apps, certifications, blogs, and sites) – This method is based on the philosophy that you get a shot if you have a body of work. The wealth of freely available resources makes this method attractive to both the confident and the frugal. There can be a fine line between rigorous code immersion and post-graduation idling, so it’s helpful to set tangible goals, a schedule, and practice self-discipline.

When given no direction on what to build, people usually struggle to find projects ideas. Look for suggestions like those on Martyr2′s Project list, and improvise. As for reading material, there are extensive lists of free programming books that may be helpful. All the material you need is out there and easy to find.

Bootcamps – Any conversation today about breaking in for the non-BSCS will include bootcamps, and I have mentioned thoughts on them before. Bootcamps may be regarded as a compromise, where the investment of both time and money rests between DIY and degree programs. Some view bootcamps as an accelerated BSCS, or a hybrid internship and apprenticeship with classwork included. Most bootcamps appear as preparatory schools for startups based on the skill focus and instructors. Do your homework, and use caution when discussing the value of bootcamp experience versus degrees to avoid insulting employers.

Internships, or cheap/free labor – Some organizations (think small businesses and non-profits) will let a non-BSCS perform development tasks as an intern or volunteer. This can be a clear ‘win-win’, as the organization gets productivity while you get somewhat valuable real-world experience. A combination of volunteer or internship and personal projects starts to level the playing field for a non-BSCS.

Training in – There are companies that hire non-BSCS for entry-level programming jobs, and the first months include corporate training programs designed for non-CS grads. The positions may pay less than entry-level programming jobs, with curriculum intended to produce effective employees instead of versatile engineers. For example, instruction could focus on proprietary technologies and frameworks instead of popular industry offerings.

What are some key items to consider?

Get out of the basement! – Some DIY’ers bury their head in code and books with no human interaction. Make community learning events and outside communication a part of your diet. This will help you measure your knowledge in a live setting while also providing the opportunity to make some industry contacts.

Don’t enter the job market too soon – For CS grads, the natural time to start the search is around graduation. No mystery there. For the non-BSCS, there is an instinctive rush to start applying to jobs early in order to take the temperature of the job market. Fight the urge. If you apply to a desirable company today and are subsequently deemed unready, don’t expect to be reconsidered in three months (when you are ready). Make sure you know enough to succeed in technical interviews, have your GitHub code clean and optimized, have any apps or sites tested and fully functional, and are prepared to make a strong impression.

Leverage the skills you have to acquire the ones you want – Bringing useful abilities and experience that can pay immediate dividends (no matter how small) to an employer mitigates their hiring risk. If you are able to contribute to an organization beyond just code, providing both a learning opportunity and a decent wage is easier for firms to justify.

Be realistic – Your three months of self-study or bootcamp are not likely to get you the dream job at Google. Be willing to start towards the bottom and pay your dues to move up.

Beware certifications – When faced with a choice of proving abilities with either code or certifications, always pick code. Many industry pros attach a stigma to those who focus on getting certified instead of just doing.

Make learning opportunity your #1 job search criteria for first jobs – The money will come. Trust me. If provided multiple job opportunities simultaneously, opting for a job due to an extra $2K or a commuting difference of five miles will be regretted. Find a place where you can learn and grow.

For more tips on job search for software professionals, see Job Tips For Geeks archives or my book.