Jodi Daynard's Blog, page 12

February 1, 2013

Welcome at Last!

Welcome at last to my new website, jodidaynard.com. With most of the glitches gone now, it remains only to add interesting links and, with a little luck, some interesting entries here as well. I’ll be adding links to short stories and essays on those pages soon. Occasionally, I’ll post a draft of something to see what you think about it. To be honest, I’m not much of a “talker,” and I’m not sure how I plan to use this space. Certainly, I’ll be sharing news, but it would be nice to get some questions and suggestions as to what you’d like to know or learn. I have a great deal of life and writing experience. I have raised a son and have survived cancer. I have taught writing and know something about the craft of writing essays, short stories, and novels. I have gone through conventional publishing processes and have self-published. Although my time is limited and life is short, I would enjoy using this space to help young writers just breaking into the business, or learning the craft, with questions about either. Let me know!

January 30, 2013

Reading on Monday, Feb. 4, at the Thomas Crane Library, Quincy, MA, at 7:00

Hi, South Shore folks. Come hear me read from The Midwife’s Revolt on Monday at the Thomas Crane Library in Quincy. You can purchase a signed copy, enjoy some refreshments, and hang out with the author. You’ll also get a discount on your purchase just for mentioning this blog.

http://calendar.boston.com/quincy_ma/...

Quincy Reading Mon. Feb. 4

http://calendar.boston.com/quincy_ma/...

January 28, 2013

Please bear with us while we’re under construction.

If you’re reading this in Google or Safari, I apologize for the mind-warping, warped images. Try Firefox — it should be okay. Jodidaynard.com is a brand new website, and I and my publicist, the lovely Pavarti Tyler, are still working on getting all the kinks and bugs out. We will be working on these issues all week; plus, we’ll be adding lots of links to some of my stories and essays that you can read. So please bear with us just a little longer. Plus, since this IS a new site, if there’s anything you’d particularly like to see, or any links you’d enjoy that don’t yet exist, just let us know! Thanks much, Jodi

January 25, 2013

A Wonderful Reading at Dumbarton House

January 23, 2013

Upcoming Reading At Dumbarton House, D.C.

January 15, 2013

New Review of The Midwife’s Revolt

Just got a great new review from Crystal Falconer:

“If you love American History, this novel will blow your mind…”

Read the full review here:

January 12, 2013

The Midwife’s Revolt on Television

It’s a strange experience to be interviewed on television: you are staring into blackness and the faint outline of your dedicated camera; blinding lights shine from above. As she reads from her teleprompter, the interviewer turns into an android-like being, one whose voice and comportment are superior that of a human. I try to emulate her: no um’s, ah’s, or nervous blinking. I am careful, too, not to drop my voice until I am ready to move on to her next question, for she moves from one subject to the next with a great, practiced fluidity.

Here’s the interview:

December 30, 2012

Interesting Historical Links

A writer of historical novels finds many kinds of material fascinating and useful: old town records, contemporary newspapers, family archives, census records, diaries, and also visual material such as drawings and sketches. To be sure, we spend a lot of our time in libraries and registries of deeds. But, thanks to the internet, many sources may be accessed from the comfort of home. Here are a few I found particularly valuable in writing The Midwife’s Revolt.

How I wrote The Midwife’s Revolt

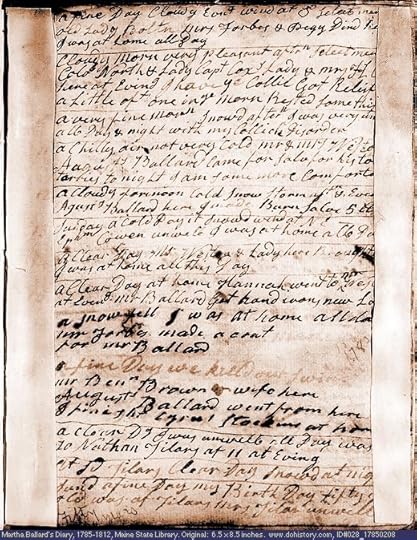

Manuscript page of Martha Ballard’s diary, dated 1785.

The first stirrings of this novel came to me as I read Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785 – 1812. I remember the thought that got the proverbial ball rolling: that midwives were privvy to the most intimate moments of a person’s life and death. My second thought was: What if a midwife came to wash a body and discovered that the person didn’t die of natural causes?

A few weeks might have passed before I knew my setting. I had been reading the letters of Abigail and John Adams when the setting came to me: “What if my midwife was a friend of Abigail Adams? What if someone died and, tending to the body, she discovered something amiss? I didn’t know what had happened, but I knew that it would involve the politics of the time. I was on my way.

I began my research with a monthly calendar which ran from June 1774 through November 1778. Each page contained boxes for all the days of the week. As I researched The Midwife’s Revolt, I wrote down all the facts that would have impacted the lives of my characters: was it hot the day Jeb went off to join Prescott’s regiment? Who died in Braintree in July of 1774, when Lizzie was mourning? What babies did he have to deliver despite her grief? Where was the army, and when did the inhabitants find out about the army’s victories and defeats? (It usually took anywhere from a few days to a full month for news to reach Braintree, depending on the source). What did the town selectmen decide about the livestock, the harvests, the grain situation? Lizzie notices many of these “facts,” and thus it is safe for a reader to assume that nearly all mentions of births, deaths, weather, diseases, and political events are all “real.” When Lizzie and Martha shoot crows for a shilling a piece, they do so because the selectmen of the time voted for this measure: the crows of Braintree were overrunning the farms. Taverns where Lizzie stops are all “real,” though my descriptions of them are imagined.

As for John and Abigail Adams and their family, I took special care to know their whereabouts and communications with one another throughout this time period. For example, when I write that Abigail was in Boston taking the “cure,” that is where she and her family actually were that week. Abigail did in fact have a stillborn child on the day Lizzie delivers it, and it took some hunting to discover the private letter in which the cause of death is described. Finally, John really does set sail for France on February 15, 1778, and his brief note scribbled from the frigate Boston to his wife, is included here verbatim, quirky capitalization and all.

I took more liberties with the “real” secondary characters Josiah Quincy, Richard Cranch, Mary Cranch, Stephen Holland, George Washington, Betsy Cranch, and Mr. Cleverly (a.k.a. Benjamin Thompson). In their actions, fact and fiction become harder to sort out. Nonetheless, I endeavored to stay true to their personalities and also their whereabouts at this time, based on many written sources. For example, Abigail’s sister Betsy Cranch was a true literary talent who kept astonishing diaries. But was her husband unappreciative of her? I don’t know. Her fictional husband certainly is. Stephen Holland was a Tory counterfeiter and was arrested at one point. But he eventually escaped to the British Army.

Lizzie Boylston is my own creation, and she is not related to any real Boylstons of Massachusetts. Martha and Thomas Miller, Harry Miller, Eliza Boylston, Giles and Bessie are entirely fictional. The plot against the Adamses—this plot, at least—is also a figment of my imagination.

Thus, George Washington never wrote letters to Josiah Quincy about Thomas Miller; nor, sadly, did he ever write my heroine Lizzie Boylston to congratulate her on a job well done. Of course, I take great pleasure in his having done so within my fictional world of The Midwife’s Revolt. It was a profoundly generous gesture; and neither Lizzie nor Martha will ever forget it.