Deborah Macgillivray's Blog, page 5

March 11, 2021

A Tale of Two Women and One Castle – The Ladies of Dunbar - Part Two

In Part 1 of my stories about the Two Ladies of Dunbar, I covered the valiant Marjorie Comyn, countess of Dunbar and March. She married into the ancient Dunbar family, and yet she held her castle against the king of England in a time of war. Instead of that deed striking a heroic chord in history, earning her immortality, her fate has been largely, frustratingly buried. Her defiance is little noted today. No poems about her, few people ever recall her life, or her heroic audacity.

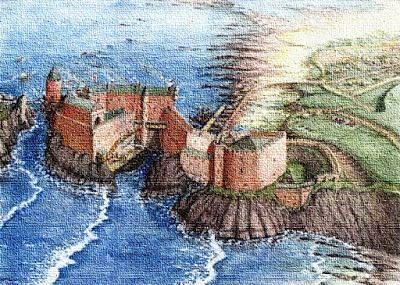

Castle Dunbar

Forty decades later, another woman traveled that same path. Agnes Randolph married into the Dunbar family—in fact, she married Marjorie’s son Cospatrick. By the time they wed, he was using Patrick as his given name. He was about eleven-years-old when his mother defended Dunbar Castle. Since young men of the nobility became squires around that age, I might assume he was riding at his father’s side, with the English king Edward I, and watched as his mother took a stance for the Scottish side. His young age is why his name isn’t on the Ragman Roll. Some mistakenly assert he assumed the titles to the earldoms in 1297, the year after his mother vanished from history. However, correspondence to and from king Edward during that time remark upon Patrick’s father’s and his loyalty to the crown, referencing the elder Dunbar as still in possession of the titles and keeping his oath to the English monarch. Edward won a crushing battle at Falkirk that autumn—with both Dunbars riding with him—yet it failed to bring him the control of the country he long craved. The castle of Dunbar—the name meaning fort of the point— was built on a huge promontory, which projected out into the sea. The ancient stronghold of the earls of March was of key strategic importance, due to its location being near to the major commercial seaport of Berwick. The fortress overlooked the coastal town of Dunbar, in East Lothian, and afforded defenders the view of most of southwest Scotland. Thus, Castle Dunbar was vital to Edward’s plans to defeating the Scots, once and for all.

Caerlaverock Castle, Dumfries

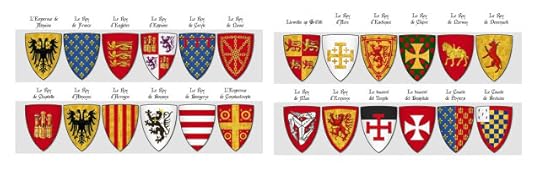

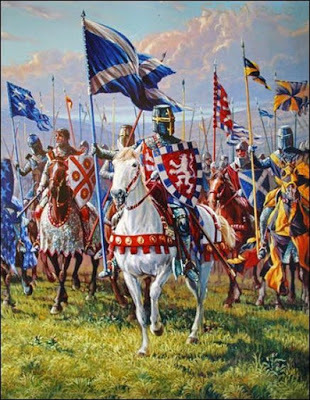

The center of the Scottish resistance was Caerlaverock Castle, near Dumfries. The Comyns were still giving the English soldiery, garrisoned throughout the countryside, hell and fury. And the supposed highly defensible Caerlaverock was their base for the struggle. From there, they could launch surprise attacks, fighting in the Highland way of guerilla warfare—strike and then vanish into the mists. Their familiarity of the countryside, and the English troops' lack of it, gave them a distinct advantage. And the tactics proved to be a festering thorn in Edward’s side. To that aim, he fixed on denying the Scots this base of operations. Edward and his army advanced through Annandale—lands of the Bruces—stopping off at the royal Pele Tower of Lochmaben. The full splendor of Longshanks' army bore down upon the beautiful moated castle, and with banners flying high, he laid siege. Once again, riding at his side was Cospatrick of Dunbar and his son Patrick. You can read about the siege in the Song of Caerlaverock, an overly flowery poem that is mostly PR for the English view of what happened. Even so, it is valuable to historians as it notes the names of the many knights and lords who were there.

There were many rich caparisons embroidered on silks and satins; many a beautiful pennon fixed to a lance; and many a banner displayed. And afar off was the noise heard of the neighing of horses: mountains and valleys were everywhere covered with sumpter horses and wagons with provisions, and sacks of tents and pavilions. And the days were long and fine.

Touches, chevalier of worship, carried gules with yellow martlets. Banner gules, a lion argent, there the Earl of Lennox flew, and upon a silver border roses of the field’s same hue; Patrick of Dunbar, his son, bore likewise with a label blue.

The anonymous poet made the whole affair sound so gay, and what a valiant effort it was on the English’s part to invest the castle. In truth, the fortress was hardly a match for the English forces, so soon both Patrick and his father were back to their own business. By December, 1300, Patrick, now in his mid-twenties, was named in an English Royal Administration paper, indicating he received regular payments for assisting King Edward in controlling the Scots in East Lothian.

Sometime after that point, he married his first wife, Ermengarde Soulis. Little is known of Ermengarde, other than she was a few years younger than Patrick, and likely a cousin, the daughter of Sir William de Soulis (one of the claimants to the throne of Scotland in 1296) and Ermengarde de Duward. She gave birth to a son Patrick—yes, yet another Patrick—sometime around 1304, for it was recorded that she received a shipment of a cask of wine from Edward Longshanks, and it was noted she was pregnant at the time. There was another son, John, born less than two years later. After that, nothing else is heard about her. No reference to her death. No place of burial, though one would assume at Dunbar Castle, which is now in ruins. One might infer she died in childbirth, or shortly thereafter, as the date would indicate that.

In 1305, Patrick petitioned King Edward for his father's lands at Polwarth, Berwickshire to be settled upon him, but this was declined. Against the backdrop of February 1306, Robert Bruce called for a meeting with John “Red” Comyn. Both had been Guardians of Scotland. Both held no love loss for the other. And both wanted to be king of the Scots. Instead of coming to an agreement, Bruce killed Comyn, and a month later then declared himself king. Early 1307, Edward was making plans, once more, to invade Scotland. He commanded, Patrick, along with his aging father (now sixty-five), were to preserve the peace in Scotland and to obey the earl of Richmond in this aim. The denial of his petition in 1305 had little consequences or impact to Patrick. Edward I died in July of 1307. Less than a year later saw Cospatrick die, so his heir Patrick assumed the earldoms of Dunbar and March.

Bruce's killing of Red Comyn

In 1313, Patrick was sent to England with a petition for the new king—Edward II. The communication was from people of Scotland, laying out their suffering at the hands of Edward Bruce. Robert’s younger brother had a bone to pick with the Comyns and Dunbars and seemed to take great pleasure in the confiscating coin, crops and horses from his enemy. Patrick’s own lands and those of his vassals were vulnerable to raids of both Bruces, as well as by attacks by the English garrisons at Berwick and Roxburgh. I surmise, in order to protect his honours, Patrick did his best to keep both sides in reasonable humor with him. When the Battle of Bannockburn in 1313 was a route for the Scots, Patrick provided shelter and assistance to the fleeing English king.

Edward II

No sooner than Edward II was safely across the English border, Patrick switched sides, aligning himself with Robert the Bruce in spectacular fashion. He took part in the Scottish siege at Berwick, as one of Bruce’s commanders. He helped Bruce gain control of the town on the 28th of Mar 1318, and the castle by the 20th July of the same year. Bruce must have been pleased with Patrick’s tireless efforts for he received a grant of lands from King Robert covering the ones Patrick had been forced to forfeit in England due to the war.

He also received a new wife. And no miss to fade into the annals of history. His second wife was Agnes, daughter of Bruce’s nephew, Thomas Randolph, 1st earl of Moray. Their royal lineage goes back to Gospatrick of Dunbar, Somerland, King Duncan I and Pictish kings, and through his mother's side he was 8th great-grandson of Henry I, king of France. Though doubt has been cast by some historians about her father being Robert the Bruce's nephew it is easily proven. Bruce's older half-sister, Isabel du Kilconquhar was the mother of Thomas Randolph. Documents from the reign of David II of Scotland (Bruce's son) makes hundreds of references to John Randolph being his cognatus/consanguineus (kinsman/male cousin)-- a cousin of the first or second degree.

If Dunbar had been vital to the English’s ability to strike into the heart of Scotland, it was doubly as important in the Bruce’s mind. He was fighting to subdue Clan Comyn—which meant the largest part of Scotland—and preparing should Edward II invade yet again. The marriage between Patrick and Agnes had all the markings of a political union. Bruce got a strong ally against his old foes the Comyns—Patrick’s relatives—and Patrick checkmated Bruce’s generals Randolph and James Douglas from raiding his lands every time they needed supplies. The advantageous marriage seemed to seal the pact. They were married in England, due to Scotland being under interdict. In 1317, Pope John XXII issued the interdict because Bruce and Douglas kept raiding in England. The papal decree prevented Scotland’s churches from celebrating all sacred rites and ceremonies, save death—which meant no marriages could be performed there.

Agnes, who was Randolph’s first born, brought to the marriage her sizable inheritance—including the lordship of Annandale (the honour belonging to Bruce’s father, but after his death had been bestowed by Bruce on his nephew Randolph). However there were a few bumps to the marriage. Dispensation had to be sought, and was granted for them to wed on the 18th August 1320, the need arising because they were related closer than the fourth degree of consanguinity. Patrick and the Bruce shared the same great grandfather—Robert de Brus, 4th lord of Annandale, which meant Agnes and Patrick were second cousins. Later, a second dispensation was needed from the Pope dated the 16th of January 1323, when it was found their family connections complicated things further. Agnes’ sister Isabella had married Patrick Dunbar—yes, another one!—this time Patrick Dunbar of Cockburn, Stranith and Bele, the nephew to Patrick through his brother Alexander, knight of Wester Spott. And her sister Geilis Isobel (history keeps merging with her older sister—by ten years—who was also named Isobel—hello! they are NOT the same person!!) married John de Dunbar of Derchester & Birkynside, Earl of Fife— another Dunbar male—Patrick’s younger brother. It seems these Randolph sisters had a thing for the men of Dunbar. The second decree was needed to validate any children as legitimate. Agnes and Patrick were already married by that time, so they were permitted to remain husband and wife. While there might be a question if Patrick was in love with his lady wife, there is no doubt he truly wanted their marriage and was willing to go to extremes to see no man put their vows asunder. In 1328, he is named as a surety on a promise to pay Edward III of England a sum of 20,000 pounds—an ungodly amount for the times—and to submit to the jurisdiction of the papal court on the matter. He wanted it clear any issues of the marriage would be considered by the church and king as true heirs to their vast joint holdings.

Agnes’ amazing father died in 1332 at the Battle of Musselburg. He didn't die in battle, but fell ill and died a short time later. Randolph was on his way to repeal yet another attack by the English. This time, it was Edward III backing the exiled Edward Balliol in his attempt to claim the Scottish crown. The latter was the son of John Balliol—the man Edward’s grandfather made king of the Scots in 1292. Both of them were pressing the assertion that Robert the Bruce had no true claim to the crown, that John was the last king of Scotland, and thus Edward Balliol, his son, was the real monarch.

During these years, Agnes held the important castle of Dunbar. She was the eldest child of Randolph’s children by his wife Isabel Stuart of Bonkyll. Agnes was a strong, opinionated female, and clearly had learned a lot from her resourceful father. She inherited her dark looks from her handsome sire. Often called "Black Annis" (a Scottish witch) or “Black Agnes”, historians immediately assume she was dark-complected, calling her “swarthy”. However, in Scottish Clans you will often see “black branch” and “red branch”, meaning the black line is the elder son, while the red branch is the younger son, so I question if the Scots calling her Black Agnes had more to do with the fact she was the eldest of Randolph’s children.

It must have chafed a strong-willed Agnes that upon the death of her father, the title of earl of Moray went to first her younger brother, instead of her. Thomas held the title for barely a year before dying at the Battle of Daupin. Then, it was handed to her second brother, John. Later on, after his demise, the title reverted to the crown, but Agnes refused to accept that and added the Countess Moray to her status. None dared challenge her on this. Patrick began using the title as well. Her brother had married well to Euphemia Ross; later, after his death she remarried to King Robert II of Scotland. After Agnes’ death, Robert II conferred the title officially to her nephew, George Dunbar (Isabella’s son) since Agnes had no legitimate heirs. (This has been questioned and disputed by historians, even to some listing George as their son).

Patrick was a good match in ambition for Agnes. Sometime after 1331, the Bishop of Durham complained to the Regency in Scotland that the village of Upsettlington, on the Scottish side of the River Tweed west of Norham, belonged to the See of Durham and “not the earl of Dunbar, who had seized it”. Patrick was not only a good fighter, but proved a savvy politician. Patrick was named as the Guardian of Scotland, and upon his father-in-law’s death, replaced Randolph as regent for Bruce’s young son, King David II.

Accounts differ about whether Agnes and Patrick had and were survived by any children. That they didn’t seem to be confirmed since their titles and inheritances passed to the children of the marriage between Patrick's nephew and Agnes' sister. There is a claim (which doesn't square with the way the earldom of Moray actually passed to the next generation), suggesting that she did have a daughter, also called Agnes of Dunbar. In the years following, the other Agnes became the mistress of David II, and preparations undertaken showed she was his intended wife when he died in 1371. Since Patrick was away so much, Agnes could have had a child by another man, or possibly she was fostering the daughter of her sister, in Scottish tradition. (One assertion is that Agnes was Patrick’s daughter by his first wife—but even a small amount of research invalidates that claim as the birth of this Agnes was after Patrick married Randolph’s daughter).

Edward III of England

Edward III of EnglandIf Edward III had given up on his schemes to place Edward Balliol on the throne of Scotland, Agnes Randolph’s name would likely have faded from history, just as her mother-in-law’s did. Only, Longshanks’ grandson had a bee in his bonnet and was unwilling to give up on the crackedbrain plan. Patrick opposed Balliol in several battles and skirmishes, following the Battle of Dupplin Moor. Thus, it appeared that his marriage to Agnes kept him firmly anchored to the Scots’ side. In January of 1333, he was appointed governor of Berwick Castle. His tenure in that position was short lived, as the English forces compelled his surrender of the castle following the Battle of Halidon Hill in July.

To escape prison, Patrick bent knee to the two Edwards, and was back on the English side. His presence is noted at the Scottish parliament Edward Balliol held, in the role of the new king. No mention of Agnes being with her husband was noted, so we may assume she was still at Dunbar and in charge of the fortress. Balliol gave over the castles Berwick, Dunbar, Roxburgh, and Edinburgh to Edward III as payment for his help. Likely a furious Agnes was forced to watch her husband destroy much of Dunbar Castle’s fortifications as part of the agreement, rendering it useless to the Scottish forces. No sooner than the dismantling was accomplished, Edward III contrarily changed his mind and demand Patrick rebuild and refit Dunbar—and pay for all the refortifications out of his own pocket. The castle wouldn’t be battle ready again until late 1337. A change in decision, which would soon come to haunt Edward III.

Edward Balliol, King Edward of Scotland (for a time)

Edward Balliol, King Edward of Scotland (for a time)At this stage, I am losing track of the ping pong game of Patrick’s changing alliances. I’m sure Agnes was, too. He had given oath to the two Edwards, in spite, he was still working for the Scottish crown. In 1335, when the King and Baliol made an attack upon the Scots, the Earl Patrick cut off a body of English archers on their return southward. Afterwards, he assisted John Randolph, 3rd earl of Moray (his wife’s younger brother) and Sir Alexander Ramsay in defeating the Count Namur at the Battle of Boroughmuir. After Namur’s surrender, John guaranteed the man’s safety and escorted him back to the English—after all, the count was the cousin of the Queen of England. On the way, John fell into an ambush and was taken prisoner. Patrick and Ramsay barely escaped with their lives.

On 13th January 1338, when Patrick Dunbar was away, the English, under William Montague, 1st earl of Salisbury, laid siege to Dunbar Castle. They made the mistake of assuming it would be an easy task since Lady Dunbar was in residence with only her servants and a few guards. However, Agnes was determined not to surrender the fortress, even though facing the English’s vastly superior force of 20,000 men. Salisbury must have been flabbergasted as Agnes tossed down her firm No! from the rampart and answered the demand:

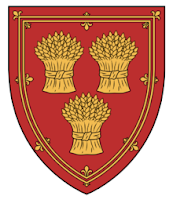

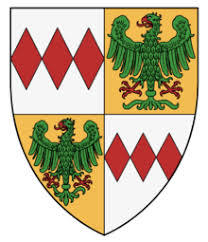

Coat of Arms for Earl Salisbury

"Of Scotland's King I haud my house, I pay him meat and fee, And I will keep my gude auld house, while my house will keep me."

Don’t you think Agnes was just a tad upset? They had just finished rebuilding the castle on Edward III’s command, and he turned around and decided to lay siege to it? Clearly, Agnes was not about to hand it over to Edward’s lackey, just to appease the king’s current whim. Enough was enough! It appears she was caught unawares by the attack. The castle guard had been thinned, the Dunbar men off fighting with her husband, and since it was midwinter, supplies were running low. Agnes was not prepared to withstand a long siege, but withstand she did.

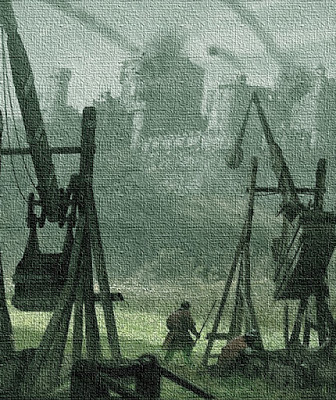

When she refused to surrender the castle, and the opening attacks were repelled, the Earl Salisbury called forth siege engines, mangonels. He attempted to take the fortress by catapulting huge boulders and lead shot against the ramparts. Agnes met their efforts with disdain. When the English would finally break from hurling stones for the day, she’d parade her ladies-in-waiting along the ramparts and they would “dust” the castle wall with white kerchiefs. After a couple weeks of this nonsense, the earl built a movable siege tower, called a sow, meant to allow men to use a battering ram under a shelter, protecting them from archers raining arrows down on them, or the defenders pouring boiling pitch or oil on them. Unflappable, Agnes called out that Salisbury better take care of his sow or she would soon be catching “little English pigs” in her bailey.

When the earl didn’t hesitate in launching the machine, Agnes had boulders—the very ones the English had been flinging into the castle—dropped over the ramparts from a crane and onto the sow, crushing it. She, naturally, shouted thanks to Salisbury for the ammunition he had supplied Dunbar. As the survivors scurried back to the English line, Agnes launched another taunt with her indelicate wit:

“…behold the litter of English pigs scurrying!”

a Sow

Her joyful defiance seemed to infect the meager number of guards. One Dunbar archer drew down on Salisbury, but deliberately hit the man next to him, and then yelled:

"There comes one of my lady's tire pins; Agnes' love shafts go straight to the heart."

Obviously, all the work Patrick had done over the past three years to refortify Dunbar was well worth the coin it cost. It was impossible for the English to invest the castle. Unable to make any progress with the attacks, Salisbury switched to guile. He bribed a Scotsman, who guarded the portcullis at the front of the castle. Salisbury extracted a promise to leave the gate unsecure, so his troops could descend upon the mighty gate and force their way inside the bailey before alarm could be raised. The earl must have smirked when the man accepted the bribe, and a short time later the portcullis creaked open. In true careless fashion, the English troops charged the gate, with Salisbury in the lead. One of his eager soldiery dashed past him and through the entry first. Shock filled them when the portcullis came crashing down, trapping the eager Englishman on the Scottish side. Salisbury just missed being captured by Agnes! The gatekeep had accepted the bribe, but had run straight to Agnes with the tale of what Salisbury wanted him to do. She had turned the tables and laid a trap for the haughty earl. Sadly, she missed taking him prisoner, but she couldn’t resist another of her stinging taunts:

"Farewell, Montague, I intended that you should have supped with us, and assist us in defending the Castle against the English."

Weeks dragged by, then months, and with Agnes getting the best of him at every turn, Salisbury’s patience was wearing thin. He had John Randolph, earl of Moray (Agnes’ youngest brother, and prisoner to the English since his capture) dragged before the castle walls, with a rope around his neck. Anges and John corresponded regularly during his imprisonment in a series of places--Bamburgh Castle, thence by York and Nottingham to Windsor, and from there was removed to Winchester, and finally to the Tower in irons. Thus Salisbury assumed she would give into a threat to his life. The earl called out that unless she surrendered he would hang John before her very eyes. If he thought to crush Agnes’ spirit, he little understood Randolph’s daughter. She merely laughed and told him to go ahead and hang John, that he would be making her the new countess of Moray—a title that should have been hers in the first place. (Evidentially, the threat to kill John was nothing more than a bribe to get her to surrender. John wasn’t harmed, and later was released, only to die in six years at in the Battle of Neville Cross. (**In a side note, an odd quirk of fate saw John being exchanged for Salisbury in a prisoner trade. In 1341 Salisbury had been taken prisoner by the French, and they agreed to trade the earl for John Randolph. After the exchange the French released Moray, and he came straight back to Scotland to raise more hell.)

Winter passed, then spring, and summer was upon them. Salisbury knew the castle had to be rationing food and water. So, he turned his attention to the longer means of winning a siege—a blockade to starve the castle out. He cut off all roads, paid Genoese galleys to block the defenders from receiving support from the sea, and stopping any communication with the outside world. Only Sir Alexander of Dalhousie (my 26th great-grandfather)—who had earned a reputation for being a constant thorn in the English king's side— got wind of Agnes’ predicament. He left Edinburgh, and with forty men, moved swiftly up the coast. Ramsay and his small company approached the castle in the cover of night, and entered through the postern gate from the sea. He brought fresh troops, ready and eager to fight, and food for the people of Dunbar. Salisbury, expecting a weakened guard, launched another frontal assault on the castle. However, Ramsay rushed out with his hardened troops, and pushed the startled Englishmen back all the way to their encampment.

Agnes had held Dunbar for nearly five months. With Salisbury becoming a laughing stock and no closer to forcing her surrender, on the 10th of June 1338, he threw up his hands and lifted the siege. The triumph of Agnes over the earl and 20,000 English men lives on in a poem by Sir Walter Scott, which put a rhyme in the earl’s mouth…

She kept a stir in tower and trench

That brawling, boisterous Scottish wench;

Came I early, came I late,

I found Agnes at the gate

The failed siege of Dunbar had cost the English crown nearly 6,000 British pounds and gained nothing from it but mockery. It seemed Edward III was no more successful in subduing Scotland than his father and grandfather had been. But Agnes, the heroine of the Scots, had earned immortality in history with her valiant defiance.

Agnes died in 1368 and was buried at Mordington, at a church established and patronized by the family. Patrick died a few months later in Crete, on route to the Holy Land. Perhaps he did love his Agnes and was making the pilgrimage after losing her. Before leaving Scotland he had arranged the security of the vast Moray and Dunbar estates. As his sons by his first marriage preceded him in death, Agnes nephew (Patrick’s grandnephew), George Dunbar, received Dunbar & March, Man and Annandale. John, the younger brother, was eventually confirmed earl of Moray.

Mordington Church

In a time of war, when Scotland was fighting for its life, Agnes gave the Scots hope. She kept over 20,000 soldiers and siege engines tied up for over five months. She saved her husband and her family from having to face that massive army. No telling how many lives she saved, and quite possible saved the country from having to yield to English rule.

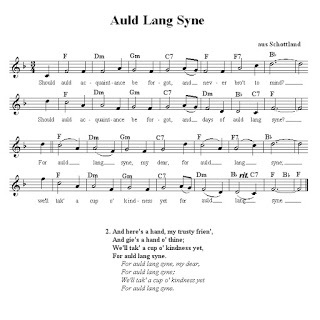

George Dunbar must have inherited the traits of the Randolph family, because he rose to become one of the most powerful men in Scotland. But no one wrote sagas and poems about him. They even wrote a song about her.

The Tales of Two Women and One Castle - The Ladies of Dunbar PART ONE

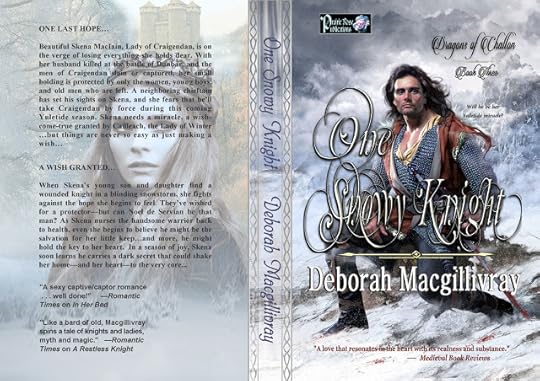

Deborah writes in the period of Robert the Bruce in her Dragons of Challon series

February 11, 2021

A Tale of Two Women and One Castle – The Ladies of Dunbar - Part One

A Tale of Two Women and One Castle

– The Ladies of Dunbar - Part One

(Ruins of Castle Dunbar)

I had intended this blog to be about one castle and two valiant women. Only, these are ladies I have long admired, thus I cannot keep their roles in history brief. With an eye to showcasing each, I will present them in two parts. I think they have earned that.

In In my second blog on women, famous or infamous ancestors, and how history can shift the view on their roles in the past or ignore them, I will be talking about two special women and one castle. These women, both my direct ancestors, both valiantly defended their castle, the same one—Dunbar Castle. While a ruins today, Dunbar was one of the strongest fortresses in all of Scotland. Situated on a prominent position overlooking the harbor town of Dunbar in East Lothian, this castle played a pivotal part in Scottish history throughout the medieval era. The first woman held this castle in a siege against the king of England—and her own husband. Then, nearly forty years later, another woman—countess of the same castle and daughter-in-law of the first—held out against another siege by the English for six months and won. These acts of defiance earn one a near legend, while the other is all but forgotten by historians.

When I got my first computer, I was amazed at the access to research online. Instead of hands on investigations of days, weeks, months of going to specific places to research documents (IF you were permitted access), suddenly, you could do the same amount of work in a matter of a few minutes. It was a researcher’s dream come true! No more “limited access” to vital records because of their age, no expensive traveling, and no more time drain.

One of the first projects I posted online was my research into Marjorie Comyn, Countess of Dunbar and March (my 25th great-grandmother). Marjorie came from Scottish nobility on both sides of her family. Daughter of Alexander Comyn, 2nd earl of Buchan and Elizabeth de Quincy(daughter of Sir Roger de Quincy, earl of Winchester), Marjorie married Cospatrick Dunbar, 8th earl of Dunbar, 7th earl of March (an ancient lineage going back to the original warrior kings of the Scots). Cospatrick carried the nickname "Blackbeard the Competitor" for he was one of thirteen men vying for the crown of the Scots in 1290, after the deaths of Alexander III and his only heir the Maid of Norway.

Cospatrick's strongest opposition was from Robert the Bruce (King Robert I’s grandfather), John Balliol (who eventually won by Edward Longshanks' decree) and John "the Black" Comyn, Lord of Badenoch. All had direct lines going back to David, earl of Huntingdon, who had been prince and heir to the crown, making this basically a family dispute! These challengers, having rather similar lineages, each claimed they held the right to rule Scotland. In the vacuum of no clear path to crowning a monarch, King Edward declared himself “overlord” to Scotland. The contenders yielded to him on this point, each hoping he would then back their bid to be Scotland’s new king. Without realizing the enormity and future repercussions of the move, they made the error of going to Edward and laying their claims before his consideration, asking him to be the judge.

(Crest of Dunbar)

Edward was considered a great legal mind. Many of the legal reforms that are still used today originated with him. While he might have loved the legal system, he had one single focus above all: uniting the kingdoms of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland—and France—under one crown—his. When the Scots nobles deferred to Edward to rule who should be king of the Scots, Edward seized the opportunity to flex that power. In the end, Edward chose John Balliol. John Black Comyn and John Balliol were both trying to snatch the crown, but they were also close kinsmen. Being of an incisive mind, Edward knew Black Comyn was no man to be controlled. To further his own aims, Edward thought by choosing Balliol he could unite the majority of Scotland behind King John, after all Clan Comyn was one of the most powerful clans in the Highlands. Balliol proved as malleable as Edward assumed, and he ended up bending knee to Edward as his overlord. If the nobles thought this would be the end to the question of who ruled Scotland, they soon learned the English monarch had other ideas. He used every excuse to yank on the puppet strings attached to Balliol. Edward's excessive demands for men and money to support the upcoming war with France placed the new Scottish king in an impossible position. Balliol was left with little choice but to rebel, and to seek an agreement to a mutual defense pact with France. Edward Longshanks'machinations and deliberate humiliations of King John would push the barons to finally say enough! Balliol—prodded by the Comyns—found spine enough to defy Edward (likely what the king of England wanted to happen all along, thus giving him the excuse to invade Scotland). Both Robert Bruce “the Competitor” and Cospatrick sought to curry favor with the English King, each thinking to offer themselves as a replacement for Balliol.

In this swirling toxic mix of political strife, Marjorie’s marriage only complicated matters. Her father was Alexander Comyn, 6th earl of Buchan, both he and her brother wanted the crown for themselves. Since the men were close kin to Balliol, they eventually backed his claim. However, the man she married, Cospatrick earl of Dunbar and March, was also a contender, and he was not letting go of his ambition to be king so easily. He rode at Edward’s side when the king of England came northward with his army of 10,000 infantry and 1000 heavy-horse.

Marjorie stood on the curtain wall, waving bye byeto her lord husband. There in the spring of 1296, she was now commander of a fortress smack in the middle of the English army and the Scottish army. Her husband was in charge of part of the English forces under Balliol’s father-in-law John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey. Her brother and uncle, and a slew of cousins, were commanders in Balliol’s army.

I suppose Cospatrick chauvinistically assumed his lady wife would abide by his decision to side with Edward Longshanks, and carry out his wishes. He failed to consider his wife was a true Scots lass, bred to think and act on her own. She was Marjorie Comyn, after all, not Marjorie Dunbar, in the tradition of Scottish females keeping their maiden name, instead of assuming their husband’s surname. After the horrible sacking of Castle Berwick, where three days of killing left the town filled with thousands of dead Scots—men, women and children—word spread like wildfire throughout the Highlands. Marjorie was determined her people would not suffer a similar fate.

In Medieval times, women often were in charge of fortresses and castles while their husbands went off to war or the Crusades. They had to deal with getting crops out, and harvesting them so their people had food enough for the winter. They were responsible for commanding the fortress troops to keep their people safe. They had to deal law locally, maintain the peace, and manage with taxes and more. The portrait of the damsel in distress, waving her kerchief from the castle bastion and waiting for a valiant knight to save her, was as much a myth back then as it is now. Women had to be capable, self-reliant, politically savvy, able to command soldiers and have a just mind to deal with day-to-day grievances of her vassals and villeins. With that in mind, I’m not certain why Cospatrick failed to heed what his wife’s reaction would be to his presence at Edward’s side when Berwick was slaughtered—especially when she knew those same troops would soon fight her family, her clan. Cospatrick intended she hold the castle against the Scots—her brothers, uncle and cousins—until Edward came with his army. There they would rest and refit before the battle brewing nearby.

April 1296 found Cospatrick in Berwick, a town littered with thousands of rotting corpses. Edward had commanded the defeated citizens rot in place as a warning to the Scots of what happened to a town when they defied the mighty king of England. Cospatrick was attending the council of war convened by Edward when tides came that Marjorie had handed over his castle to her brother, John Comyn of Buchan. One can imagine how Cospatrick felt. He lived in a strange mix of fear and awe of Edward Plantagenet. Edward’s view on women was well known. Here, Cospatrick was hoping to curry favor with the king, on the chance Edward would put the crown of Scotland on his head, to that goal, he had pledged Dunbar Castle for Edward’s forward base of operations. The castle was vital to Edward’s plans since it lay on the road that went straight to Edinburgh. Suddenly, the rug was yanked from beneath his feet! His lady wife had defied him and was supporting the Scottish forces. I am sure Cospatrick knew his chance of ever being king of the Scots died with the news of Marjorie’s defiance. Edward was forced to change his plans and send John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey, and William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick (the latter a veteran of Edward’s campaigns in Wales) northward with the express purpose of retaking the castle. On the 25th of April, one-third of Edward’s force marched out of Berwick with a brigade of 400 heavy cavalry and 4500 infantry.

Can you imagine the embarrassment of the mighty earl of Dunbar and March? A man who dreamt of being king of Scotland, and seeing that objective within grasp only to learn his lady wife was destroying his ambition—not only defying him, but defying his king? Edward demanded the castle taken before the coming battle. It didn’t happen. Marjorie refused to yield. The troops had arrived late in the day on April 26th. Edward Longshanks and her husband were forced to deal with being locked out. Already undermanned due to her husband stripping the fortress of men to fight for Edward, Marjorie used her disobedience to buy time to get her people out by the sea. Edward ordered Cospatrick to retake his own castle. He was impatient to see the deed done before they engaged the Scottish army.

(Dunbar Castle 1296)

I suppose her brother and uncle hoped to catch the English in the midst of trying to take the castle. On the sunny, but cold spring morn of the 27th, the Scottish host was camped near Doon Hill. Comyn, Lord Badenoch could easily see Warenne’s army, marching on the road to Spott Village. Dust raised by the men and horses would have signaled where the English forces were a mile away. The Comyns were confident in their numbers, but failed to take into account they lacked heavy horse, archers, and their infantry was hardly more than farmers with pitchforks and axes. Compared to well-seasoned warriors and shock troops in the English army, doom rode on the horizon. The Scots didn’t stand a chance. Comyn’s single plan of battle was a full frontal attack. The whole battle was over in less than an hour. Hundreds —thousands, if you believe some English historians—of Scots lay dead on the battlefield, and nearly all of Scottish nobility was taken prisoner to be sent south for trial.

(Battle of Dunbar 1296)

That left Edward to turn his attention back to Dunbar castle. Some sources say the castle just surrendered when Edward rode up to the gates after the battle had been won. However, his exchequer receipts hint at a different story. Edward paid for “repairs, restocking and refitting” and for the English troops to remain behind and secure the castle. Since Edward was a pinchpenny, it is doubtful he would have paid such large sums had the fortress not been severely damage during the retaking.

There are only a few references to the storming of the castle, and even less about Marjorie’s fate. The great Scottish author Nigel Tranter featured the Dunbars heavily in several of his novels, and even made mention of Marjorie’s defiance in his Scottish Castles: Tales and Traditions. Still, he made no mention of her fate. I was honored to develop a bit of email correspondence with him on the topic, just before his death. He was just learning the internet, still puzzled by it, and said it might take time to answer my questions about Marjorie’s fate. Sadly, he died before he could reply with his thoughts.

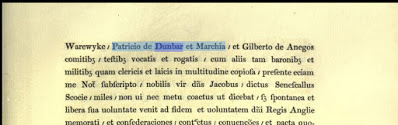

Through the years, I met Scottish historians who traveled in my grandfather’s circle. The “lit test” I used to weed out people, who truly knew their history from the ones that just repeated the works of others, was by posing this: “What happened to Marjorie Comyn, Countess of Dunbar and March in 1296?”. Sadly, most never tried to follow up with an answer. One came to me at a party and said Marjorie went back north to Clan Comyn and died in 1308. I busted that bubble. That was Marjorie’s daughter—Margaret, also called Marjorie—who was a teen at the time. Historians keep getting all the Cospatricks/Patricks and Marjorie/Marjorys mixed up. Her daughter did escape and go back to Clan Comyn and lived a long life, marrying William Douglas, earl of Douglas. Another man, a professor of Scottish History—emailed me with a photocopy of a record, retelling of her death, recorded 1286. No. That is incorrect. Since Marjorie was holding the castle against her husband and his king in 1296, she could hardly have been dead 10 years earlier. I pointed out how similar an 8 and 9 could look when done by a hand using pen and ink. I even had one tell me she was alive and signed the Ragman Roll in August 1296. There is only one name for Dunbar and March. Patricio de Dunbar et Marchia. I was never certain if he was outright lying, trying to trip me up for not knowing who was on the document, or he was just running a bluff, hoping I would defer and not call him on it. Cospatrick did die in 1308, so I think some just ascribe the date to Marjorie, too. I even had one tell me she died in 1358 and he had her bearing children in her late 60s. Humm…no….lol.

(List of Names in Ragman Roll showing only Cospatrick of Dunbar and March)

It was always my contention she died either in the siege of the castle or sometime shortly thereafter. I make reference to Marjorie’s defiance and the question of her fate in my first novel, A Restless Knight.

“What shame for Cospatrick. He curries favor at the English’s side, thinking Edward might consider him as the next king of the Scots, whilst the Lady Marjorie commands Castle Dunbar. She be a Comyn born and bred, daughter to Buchan.”

“Aye, she sided with her brother and father, turning the castle over to the Scots. Battle took place. Though outnumbered three times over, Warenne’s troops are battle-hardened horsemen, veterans from campaigns in Wales and Flanders. They held and repulsed the Scots. After that, the Scots crumbled. Edward ordered Cospatrick to invest Castle Dunbar. The castle fell...”

“And the Lady Marjorie?”

He hoped Tamlyn would not empathize too strongly with Marjorie Comyn, Lady Dunbar. “No one knows for sure. Some of Dunbar’s people escaped, using tunnels to the sea. Possibly, she slipped out with them, and has returned north to the Comyn stronghold in the Highlands.”

Tamlyn shivered. “Or she was in the castle when it was stormed? Many mislike the Earl Dunbar. His persecution of True Thomas be nigh well legend. Pride wouldst not stand the disgrace of his countess handing his castle over to her kin.”

Great strides are being made since the internet to reexamine and correct bad history. For centuries, and in the movie Braveheart, William Wallace’s father was named as Malcolm Wallace. Just recently, they turned over Wallace’s great seal from when he was Guardian of Scotland, and lo!—was “William Wallace son of Alan Wallace”. All these years they had it wrong! To my excitement, in the past few years, I am finally seeing sources listing Marjorie’s death as 29th April, 1296 and at Dunbar Castle, Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland. The battle of Dunbar was on the 27th, two days before. This new information fits with my long held belief that Marjorie died either defending her castle and people, or was killed afterward, and her death hushed up because it would have been a rallying cry for Clan Comyn.

She was a valiant lady who defended and saved many of her people, who did make it northward to Clan Comyn because of her. She defied a husband and a king—and likely died for it. Now history largely has erased her heroic effort. She was a true brave heart! She was forty-years-old when she died.

In Part two of The Ladies of Dunbar, I will tell you of another countess of Dunbar—daughter-in-law of Marjorie, who was just as stubborn and savvy, who once again held the castle against the English. So until next month, I will leave you with the Dunbar motto “In Promptu”, which means “In Readiness”. I do believe Marjorie did those words honor.

January 30, 2021

History of the Masks of Carnival

The History and Meaning Behind the Masks of Carnival

The Venice Carnival dates back to the 1300s, but has changed in purpose and style over the centuries, even banned by the Church at points. Not just a time of festivities, it saw a period of social change by the people, outside of government and Church. It was often used for political purposes, allowing the common man and nobility to move and navigate the troubled times without revealing their identities. In ancient years, the lengths of observances ran much longer, often months—sometimes nearly half of the year—as it permitted people to hold votes and work political machinations, giving voice, albeit anonymous to the common citizen, and allowing the nobles to work outside of their sphere to affect change. It often allowed romantic assignations, as the masked revelers moved from party to party, even indulged in the gaiety in the streets. Yet, it was so much more. Carnival was the budding of political and religious change that happened outside normal channels of government and Church.

Currently, it runs the ten days before Ash Wednesday. On first glance, The Carnival of Venice shares many characteristics with the Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans. New Orleans is the Big Easy, with a party on down, Cher that sees less emphasis on the traditional costumes, and focuses on enjoying the best time ever. The Venice celebration still draws heavily on their Medieval roots and customs of their elaborate costumes. The fancy attire slowly evolved over the centuries, yet remained firmly rooted in the Medieval origins. Venetians generally started holding their masked parties on the 26th of December—the start of Lent. Masks were created to conceal identities, thus reflecting a social change, allowing the lowest classes and nobility to mingle. Peasants and aristos alike could indulge in grand balls, dancing and partying throughout the long winter nights. The anonymity of masks permitted a freedom to let their inner wishes and fantasies take life. Gambling, drinking and indulging in clandestine affairs happened with no repercussions, which soon proved advantageous for furtive political aspirations. Soon, it was obligatory to wear masks at certain governmental decision-making events, where all citizens were required to act anonymously as peers. Through the masquerades the divisions of aristo and serf lines blurred. The protected processes, in truth, were the first steps to a democracy. To see this balloting was fair and secure, men were not permitted to carry swords or guns while wearing masks, and the police enforced this law religiously. Thus, you see the masks and their meanings carry a more involved significance that just hiding who you were and having a good time.

The original mask was named the Batua. It was always white, and made of ceramic or leather. The name comes from behüten, meaning to protect. The mask fit over the whole face, completely concealing the wearer’s identity. To further hide who they were, a hood of black or red covered their heads and reached their shoulders, and was topped by a black tricono—a tri-corner hat. A long black or red cape finished the costume. While designed for a man, women soon were taking advantage of the opportunity the outfit afforded them. The mouth on the mask was very small and expressionless, with oval slits for eyes, and two air holes on the nose. While the mask afforded complete protection, it did not allow the wearer to eat or drink without taking it off.

The Volta was the next style to rise. It completely cover the face, but often held a ghostly or more sinister expression. Also called the Larva Mask—Larva meaning ghost—it was a slightly unnerving countenance, though it did let the wearer eat and drink easily.

Usually worn by men, again they came with black hoods covering hair and shoulders, black capes and the black tricorno hat.

Women quickly saw disadvantage to the full covering, and adopted the Moretta. Originating in France, the Moretta, allowed their feminine features to be showcased with less coverage. The design quickly saw this mask losing favor. Also called the Silent Mask, women held the mask before their face by clenching a tabbed button between their teeth. I can imagine they quickly wanted changes to this style! Surely, a man invented this one.

Disenchanted with the Moretta’s enforced silence, women soon flocked to the Columbina masks. Inspired by Commedia dell’arte. The art form was improvised plays, very popular from the 1500s. Each held a set stock of comedic characters for the actors, a few basic plots—such as troubled love affairs—but often they reflected current events and political protests in the guise of comedy. Much like political cartoons of today, these street plays poked fun at politicians and the Church, all in the perimeters of comedy and entertainment. The female standard in the plays had a demi-masque, only covering part of the forehead, eyes and upper parts of the nose and cheeks, revealing, yet more flattering to the female face. These were decorated with gold, silver, crystals, and colorful plumes, especially peacock feathers, and tied with ribbons to hold them in place or carried on a baton. Today, the costuming has been taken to a high art form.

One of the more bizarre ones you will see is the Medico Della Peste (Plague Doctor). These startling bird-beak style masks were created in the 1600s by a French physician Charles de Lorme, and not for the purposes of Carnival celebrating. Just the opposite, de Lorme formed them to protect doctors treating plague victims. By this time, foul airs were suspect as the cause of spreading the plague, and in response, naturally physicians wanted to guard themselves against infection. De Lorme decided plague tainted the air with these noxious fumes, so then if the physicians breathed perfumed air they would escape catching the disease. He created this grotesque mask that looked like a larger-than-life bird head. The exaggerated beak was filled with herbs, and the eye slits were covered with rose tinted lenses. Literally, several pieces of common knowledge have passed into our consciousness from this horrible period. The term looking through rose colored glasses, now meaning viewing the world in a beautiful tone, instead of facing reality, came from the creation of these physicians’ masks. The other was the old tome Ring Around the Rosie—a child’s rhyme that speaks about the mass spreading of deaths from the Black Death. Children of future generations repeated this morbid singsong without ever understanding what they were chanting. To further the protection of the healers, physicians wore hoods covering their head and shoulders, long gowns and capes, with huge white gloves that went all the way up their upper arms. The Japanese used the figure of Godzilla, first to explain the bombs that were dropped on them during WWII, and then through making Godzilla the protector of their island, they faced their terrors and made the nightmare less disturbing. The Venetians did the same in adopting this bizarre costume as part of the collection of characters. They were saying that death walked amongst them, and they mocked and laughed at mortality.

Arlecchino was a later addition. Coming from the French Arleguin—this evolved to the more familiar Harlequin. He was a fool, depicted dressed in diamonds of black and white, or a rainbow of colors. Another version on this theme was the Pulcinella—a crook-nosed hunchback, that you typically saw as Punch in the Punch and Judy street puppet theatre performers.

The final two you will see are La Ruffina—the Old Woman. She is usually the mother or, grandmother, sometimes with Gypsy portrayals, who takes great delight in trying to foil a lovers' tryst. Scaramuccia, again comes from the French Scaramouche. He was a total rogue, who dashed about with a sword causing mischief, and challenging other males to mock duels. Rounding out the costumes were ones of the Moon and Sun, religious popes and bishops, kings and queens, or sometimes animals such as cats and wolves.

By the 1800s, Carnival began to fall into decline. It had changed from the period of Lent, to lasting for six months of every year. In 1797 Venice became a part of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, after Napoleon signed the Treaty of Campo Formio. The Austrians quickly took charge of the city, and afterward the celebrations all but stopped. It was a long absence before Venice saw a true Carnival again. In 1979, the government decided to revive the traditions of the celebration, using it to draw tourists. The move worked as over three million visitors come to Venice each year for the colorful pre-Lent parades and parties. A centerpiece for the ten day festival is the la maschera più bella—the most beautiful mask. A panel of international designers pick the most stunning mask for each year.

So, even if you have experienced the unforgettable Mardi Gras of New Orleans, you might still wish to indulge in the extravagance, pageantry and historical display of Carnival in Venice.

© Deborah Macgillivray, February 2019

January 24, 2021

Carnival goes virtual

I always eagerly await the new picture of Carnival in Venice, Italy each year. The costumes are simply breathtaking. I worried about Covid this year, and yes most of the yearly celebration starting January 30th will be virtual this season.

So check around on social media -- there will he chat room celebrations and more. And in a way, it is going to open up the world into joining the celebrations.

The broadcasts are scheduled for February 6-7 and February 11-16 at 17:00. Look for information on social networks. Virtual rooms will be created in which you can become a participant in the Virtual Carnival

January 6, 2021

Countess Mabel Montgomerie -- a woman ahead of her times or a monster in men's eyes?

The first in a series of blogs about ancestors,

the past and the truth

Ever notice the media tends to be harder on women than men? They critique their hair, what they wear. If a women is strong she is portrayed as being hateful, mean or—excuse the slur—a bitch. Men are not subjected to such criticisms. You cannot go anywhere that you won’t see this in action: she’s too fat, too short, too skinny, her nose is too long, eyes close together, omg—she wore a pantsuit! There is Miss America, Miss Universe, Mrs. America, Miss Black America—but where is the Mr. America or Mr. Universe? Just stop and try to think of a platform that subjects men to those same demoralizing nitpicking. Tapping my nails on the table, waiting. Fashion throughout history was a means to see women conform. Whatever the era the dress, customs, protocols and positions in life, all were dictated by men’s critical eye and control. Along with the male point of view on the woman’s role in life, they have also managed what we know of how women lived, survived and dealt with their roles in a man’s world.

Ever notice the media tends to be harder on women than men? They critique their hair, what they wear. If a women is strong she is portrayed as being hateful, mean or—excuse the slur—a bitch. Men are not subjected to such criticisms. You cannot go anywhere that you won’t see this in action: she’s too fat, too short, too skinny, her nose is too long, eyes close together, omg—she wore a pantsuit! There is Miss America, Miss Universe, Mrs. America, Miss Black America—but where is the Mr. America or Mr. Universe? Just stop and try to think of a platform that subjects men to those same demoralizing nitpicking. Tapping my nails on the table, waiting. Fashion throughout history was a means to see women conform. Whatever the era the dress, customs, protocols and positions in life, all were dictated by men’s critical eye and control. Along with the male point of view on the woman’s role in life, they have also managed what we know of how women lived, survived and dealt with their roles in a man’s world. Now extend that throughout history. There were a few matriarchal societies through the ages, the belief being you cannot tell a man’s true father at birth, but you knew who the mother was. Those societies were stamped out, or consumed by male dominance. This is not a rant of hating men, for I find them endlessly fascinating, only I am humbugged that women’s pasts are increasingly lost to our knowledge due to being relegated to “unknown mother”. There were women over the centuries that seized life and molded the course of their destiny, their fortunes, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (my 24th great-grandmother). Only rarely have historians portrayed these women in the light of admiration. Randall Wallace, in the screenplay for Braveheart, opens the movie with the line “...history is written by those who have hanged heroes”. Women had often been portrayed as little more than servants to their husbands, a brood mare to bear heirs, and a piece of property easily discarded, once they have worn themselves out birthing babies one after another. They were set aside, locked away in some nunnery— or sometimes died in highly suspect circumstances i.e. murdered— to make way for another younger, richer wife.

I had to wonder about this slant against women as I looked at my first ancestor in this series of blogs about unusual women: Mabel Montgomerie. She has been called many unflattering things, murderess, "l'Empoisonneuse", evil, greedy, wicked—and she paid the price for her deeds—real or rumored slander. However, with history turning a blind eye to granting women their true recognition, it’s very hard to find the facts to refute these claims. I can only ponder and try to be impartial in judging my ancestor, especially since some of the writings about her come from Orderic Vitalis, who was only two years old at the time of her death.

(Countess Mabel Montgomerie's arms)

My 31st great-grandmother on my mother’s side, Mabel Montgomerie was born Mabel Talvas dame de Bellême et d'Alençon in Alençon, Orne, Basse-Normandie, France, sometimes around 1030. As often the case for females, the exact date was not noted. Neither was the name of her mother recorded, only singled out as “Hildegard, daughter of Raoul V de Beaumont”. Even in death, Mabel is not allowed to rest in peace, as her tomb has been destroyed due to the hatred of her. She was a wealthy Norman noblewoman. She inherited the lordship of Bellême from her father, Guillaume II "Talvas" de Bellême, seigneur d'Alenço. Mabel was a loyal woman, but that loyalty cost her when her brother exiled their father for various offences—his cruelty was legendary, they say—including killing their mother for daring to disagree with him on the way to church. Being a loving daughter, favorite of her father over her brothers, she accompanied him in his exile, thus earning the amenity of everyone, automatically believing she was “cut from the same cloth”.

Mabel and Guillaume sought the protection of Roger II "The Great" de Montgomerie, 1st earl of Shropshire, earl of Arundel & earl of Shrewsbury. He was one of William the Conqueror’s counselors, but stayed behind for the 1066 invasion of England, actually left in power to run the whole of Normandy. For that, William rewarded him with holdings of two powerful positions in England, and immediately he began building the massive Ludlow Castle. Besides this, he eventually built his honours to number eight-three, over half of England and Normandy. Small wonder, people called him Roger “The Great”.

(Ludlow Castle)

Mabel saw him as a husband worthy of her goals. The Talvas convinced Roger they were the aggrieved party, and that her brothers were plotting to get rid of her, since Guillaume had named her as his heir. Well, the brothers were plotting, so we have that much truth. Her dowry was worth a king's ransom—if they could get his oldest son off their backs. Mabel came with massive lands, endless wealth and a shrewdness that attracted Roger. He was as ambitious as Mabel, if not more so, thus they seemed a perfect match. Theirs was not only a brilliant political bond, it must have been a marriage of love, since she bore him eleven children! Thus, Mabel became Countess Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Arundel—and eighty other titles—through her marriage to the eminently pious, Roger Montgomerie. Through the ages, Montgomerie men have proved time and again to warm to intelligent wife, relishing the challenge of women willing to step outside of the normal roles afforded females. Following that tradition, Mabel was given free rein to be an equal partner to Roger.

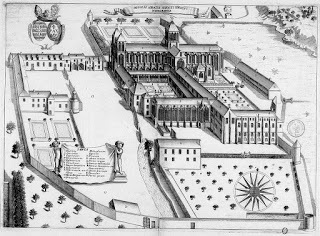

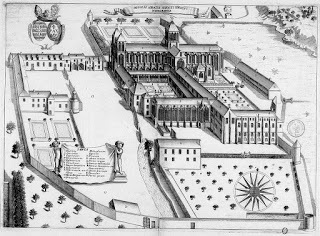

(Abbey of St Evroul)

(Abbey of St Evroul)But not in one matter—religion. Montgomerie supported many churches and abbeys, and even built several abbeys on his different fiefs. The biggest thorn in her side was the Abbey of St Evroul. Religious views likely was one their first clashes of wills. She was determined he curtail the huge fortunes he was placing in the hands of these monks and priests. Roger was very devout, and the religious sects ran their monastery on his largess, frequently prevailing upon him to give more than the general tithing. Tithing was required in ancient times—everyone was to give ten percent of their income to the church. Since he inherited control of her lands through the marriage, coin from her holding of Bellême, in northwest France, was going into the hands of these ever-needy monks without a bye your leave. That didn’t sit well with Mabel. Most of this tale comes from writings of the monks, especially the head of the order—Abbot Thierry. He was Roger’s confessor, so in spite of Montgomerie’s ever growing greed, the abbot proved adept at bending his lord’s will on concerns of the monastery. Thierry heard the man’s confessions. It was reasonable he likely knew Montgomerie’s nature, as well as Mabel’s. Since the strong-willed Mabel’s attempt to curtail their monies, we have to take their reporting of incidents with a thimble full of salt.

(Abbey of St Evroul)

No matter what, Mabel could not influence her husband on this issue, especially this tug of war with Abbot Thierry. Being a cunning woman, she devised an end run. She began visiting the monasteries, with her full entourage. Castles and the monasteries, in medieval times, were basically required to serve as hotels for traveling lords and ladies. Mabel created a win-win situation. She would go traveling the countryside on the excuse of checking on her husband’s vast holdings, along with her one hundred knights and ladies, and various servants. These abbeys dare not offer insult to the countess, or run the risk of Roger withdrawing his support. They were forced to open their gates and all Mabel and her retinue in, to stay as long as they liked. They would have to feed them—and all the horses. Mabel saved money by not feeding the lot at the Montgomerie honours, and she was draining away the supplies bought with her husband’s monies.

The Abbot tried to reason with her, that they were a poor monastery (which was not the truth and she knew it) and it would drain them completely to support her entourage. Mabel was unmoved by his appeals. When he said feeding one hundred knights, and providing for her “worldly pomp” was simply too much, Mabel said fine, she would leave. But—she would return the next week with one thousand knights! Thierry was furious—a mere woman daring to best him. Likely, he knew he was losing this battle of the wills, so he countered, “Believe me, unless you depart from this wickedness, you will suffer for it!” Much to no surprise, a few hours later at supper, Mabel suddenly was seized by stomach pains. She retired for the evening and the queasiness turned to agony. From this distance, we can assume one of the learned monks put something in her supper, and you can bet the incisively smart Mabel knew it, too. Ceding the battle for the moment, she took her troops and left the monastery. The monks were not content with that bit of mischief. On the way home, Mabel stopped at the holding of Roger Suisnar. Still feeling ill—according to the Abbot—Mabel demanded Suisnar he give her his infant child to suckle at her breast. The child drew the poison from Mabel, who instantly recovered. Only the small child died doing it. Mabel knew the monks had poisoned her, but instead of demanding her husband punish them, she wisely never went to the abbey again.

The next big black mark history sees against Mabel was endlessly hunger for more land—and vengeance against those who had opposed her, her father and her husband. Arnold de Echauffour, the son of Lord William Giroie, presented himself to Roger, seeking his aid. William was an old enemy of Mabel’s father, and there was a long running blood feud between the Montgomeries and the Giroies. Arnold was making his way back from Italy, and stopped to present himself to Earl Roger, hoping to gain favor. Arnold sought to barter a truce between his family and the Montgomeries. He even presented a fine fur cloak to Roger as a gift. He wanted Roger to throw his might behind him, so he could see his ancestral lands restored to his father. As Roger’s holdings were so widespread, he was always in the need of loyal knights, so having one less enemy was worth putting aside old grievances. Arnold swore homage to Roger, who gave him a writ for Arnold and his father to travel across Montgomerie lands without bother, and agreed the Giroies lands in Montgomerie’s hands would be returned to them.

It is reported that Mabel was less than happy with this turn of events. She decided to avenge her father on her own, so it is written. Here is where it’s murky, more rumors than fact, but history seemed determined to paint Mabel as a monster. Tales say she prepared a celebratory drink to seal the pact, and had one of her prettiest ladies take the potion to him, before he left the holding. Whatever the circumstances, Arnold did not trust the daughter of his old enemy, and refused her kindness. Unfortunately, Gilbert Montgomerie, Roger’s only brother, was showing off, grabbed the goblet and gulped it down. Gilbert was some miles away, when he fell ill. Three days later he died in anguish. Roger’s brother had been a valiant knight, and was much loved by all. Roger adored his brother and grieved deeply.

Some time later, Arnold did fall gravely ill. Rumors swirled Mabel had poisoned him by sending some “special” refreshments to him. It seems rather unlikely, if Arnold did not trust her, and proved that by refusing the drink she offered before, why would he accept another such beverage sent from her? Arnold, Lord Grioie, and his chamberlain, Roger Goulafre, all fell ill, and had to be carried back to their castle. Both Goulafre and Lord Grioie recovered with good care. Arnold did not. He died on the first of January 1064. The lands he sought to claim stayed with Roger Montgomerie's possession. After those events, the Giroie family fell on hard times. Arnold’s infant children were sent to live as poor relations within the households of various lords across Normandy. His wife sought refuge with her wealthy brother, Eudo, steward to the Duke of Normandy. The Giroie family would never be powerful again. Who poisoned Arnold? There were several possibilities, but all fault fell on Mabel’s shoulders. Few point at Roger Montgomerie, who gained as much as she did. It’s just too easy to blame a female—just like they blame Helen of Troy for causing the Trojan War.

Roger held great influence with the duke of Normandy, who was paranoid about his vassals rebelling. When Roger hinted this his neighbors were planning just this thing, the duke listened, and was only too happy to have Roger put down the so-called rebellion by striking first and seizing the lands of Eodolph de Toni, Hugh de Grant-Mesnil and Arnold d’Eschafuour, amongst many others. So it was clear, Roger was as devious as Mabel, maybe more so. When Mabel’s brother died in 1070, she finally seized control of that part of the lands of her father. Between Roger and Mabel, they owned so many honours in three countries, that he was as powerful and wealthy as any king.

That sort of influence, and sway with the kings of two nations, naturally fermented jealousy and enemies. Hugh Brunel de la roche was one of the knights who lost everything to Roger and Mabel. Unable to accept the humiliation of losing his ancestral holding, he plotted to take his revenge. During the long night of December 2, 1079, Hugh led his three brothers to force their way into Mabel’s quarters at Château at Bures-sur-Dives. Mabel was relaxing in her chamber, enjoying a bath, when Hugh and his brothers burst in. Before she could raise a cry, Hugh lopped off Mabel’s head with his great sword. Her son, Hugh de Montgomerie gave chase to the murdering brothers; they evaded pursuers by destroying a bridge, knowing those following could not cross the small river due to wintertide flooding. They left Normandy, never to return.

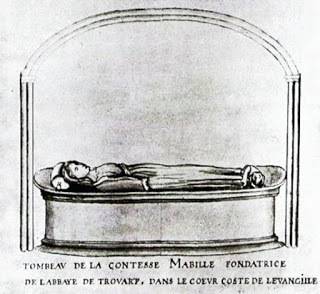

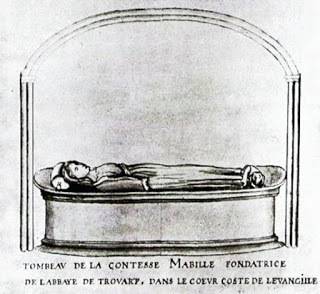

Mabel’s decapitated body was buried three days later at Troarn Abbey. Her tomb was marked by an epitaph.

Sprung from the noble and the brave,Here Mabel finds a narrow grave.But, above all woman’s glory,Fills a page in famous story.Commanding, eloquent, and wise,And prompt to daring enterprise;Though slight her form, her soul was great,And, proudly swelling in her state,Rich dress, and pomp, and retinue,Lent it their grace and honours due.The border’s guard, the country’s shield,Both love and fear her might revealed,Till Hugh, revengeful, gained her bower,In dark December’s midnight hour.Then saw the Dive’s o’erflowing streamThe ruthless murderer’s poignard gleam.Now friends, some moments kindly spare,For her soul’s rest to breathe a prayer.

Mabel’s tomb survived into the early 18th century, but by 1752 it no longer existed. No one knows what became of her body.

History, written by men, painted her as a monster, a poisoner. But you have to wonder how much was really her machinations, and how much was blamed on her because she was an easy target. She was beautiful, smart, aggressive, and dared to take a place in a man’s world. I have to wonder if she is guilty more of those thoughts, than the supposed deeds attributed to her.

Her son carried the mantle of her animosity. Robert de Belême de Montgomerie, comte de Phonthieu, 3rd earl Shrewsbury and Arundel, was known as "Robert the Devil."

Thank you for taking time to stop by and learn about Mabel, a woman ahead of her times. I hope you will continue to join me on the second Saturday of each month, to learn of another colorful ancestor.

Countess Mabel Montgomerie -- a woman head of her times or a monster in men's eyes?

Ever notice the media tends to be harder on women than men? They critique their hair, what they wear. If a women is strong she is portrayed as being hateful, mean or—excuse the slur—a bitch. Men are not subjected to such criticisms. You cannot go anywhere that you won’t see this in action: she’s too fat, too short, too skinny, her nose is too long, eyes close together, omg—she wore a pantsuit! There is Miss America, Miss Universe, Mrs. America, Miss Black America—but where is the Mr. America or Mr. Universe? Just stop and try to think of a platform that subjects men to those same demoralizing nitpicking. Tapping my nails on the table, waiting. Fashion throughout history was a means to see women conform. Whatever the era the dress, customs, protocols and positions in life, all were dictated by men’s critical eye and control. Along with the male point of view on the woman’s role in life, they have also managed what we know of how women lived, survived and dealt with their roles in a man’s world.

Now extend that throughout history. There were a few matriarchal societies through the ages, the belief being you cannot tell a man’s true father at birth, but you knew who the mother was. Those societies were stamped out, or consumed by male dominance. This is not a rant of hating men, for I find them endlessly fascinating, only I am humbugged that women’s pasts are increasingly lost to our knowledge due to being relegated to “unknown mother”. There were women over the centuries that seized life and molded the course of their destiny, their fortunes, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (my 24th great-grandmother). Only rarely have historians portrayed these women in the light of admiration. Randall Wallace, in the screenplay for Braveheart, opens the movie with the line “...history is written by those who have hanged heroes”. Women had often been portrayed as little more than servants to their husbands, a brood mare to bear heirs, and a piece of property easily discarded, once they have worn themselves out birthing babies one after another. They were set aside, locked away in some nunnery— or sometimes died in highly suspect circumstances i.e. murdered— to make way for another younger, richer wife.

I had to wonder about this slant against women as I looked at my first ancestor in this series of blogs about unusual women: Mabel Montgomerie. She has been called many unflattering things, murderess, "l'Empoisonneuse", evil, greedy, wicked—and she paid the price for her deeds—real or rumored slander. However, with history turning a blind eye to granting women their true recognition, it’s very hard to find the facts to refute these claims. I can only ponder and try to be impartial in judging my ancestor, especially since some of the writings about her come from Orderic Vitalis, who was only two years old at the time of her death.

(Countess Mabel Montgomerie's arms)

My 31st great-grandmother on my mother’s side, Mabel Montgomerie was born Mabel Talvas dame de Bellême et d'Alençon in Alençon, Orne, Basse-Normandie, France, sometimes around 1030. As often the case for females, the exact date was not noted. Neither was the name of her mother recorded, only singled out as “Hildegard, daughter of Raoul V de Beaumont”. Even in death, Mabel is not allowed to rest in peace, as her tomb has been destroyed due to the hatred of her. She was a wealthy Norman noblewoman. She inherited the lordship of Bellême from her father, Guillaume II "Talvas" de Bellême, seigneur d'Alenço. Mabel was a loyal woman, but that loyalty cost her when her brother exiled their father for various offences—his cruelty was legendary, they say—including killing their mother for daring to disagree with him on the way to church. Being a loving daughter, favorite of her father over her brothers, she accompanied him in his exile, thus earning the amenity of everyone, automatically believing she was “cut from the same cloth”.

Mabel and Guillaume sought the protection of Roger II "The Great" de Montgomerie, 1st earl of Shropshire, earl of Arundel & earl of Shrewsbury. He was one of William the Conqueror’s counselors, but stayed behind for the 1066 invasion of England, actually left in power to run the whole of Normandy. For that, William rewarded him with holdings of two powerful positions in England, and immediately he began building the massive Ludlow Castle. Besides this, he eventually built his honours to number eight-three, over half of England and Normandy. Small wonder, people called him Roger “The Great”.

(Ludlow Castle)

Mabel saw him as a husband worthy of her goals. The Talvas convinced Roger they were the aggrieved party, and that her brothers were plotting to get rid of her, since Guillaume had named her as his heir. Well, the brothers were plotting, so we have that much truth. Her dowry was worth a king's ransom—if they could get his oldest son off their backs. Mabel came with massive lands, endless wealth and a shrewdness that attracted Roger. He was as ambitious as Mabel, if not more so, thus they seemed a perfect match. Theirs was not only a brilliant political bond, it must have been a marriage of love, since she bore him eleven children! Thus, Mabel became Countess Shrewsbury, Shropshire, Arundel—and eighty other titles—through her marriage to the eminently pious, Roger Montgomerie. Through the ages, Montgomerie men have proved time and again to warm to intelligent wife, relishing the challenge of women willing to step outside of the normal roles afforded females. Following that tradition, Mabel was given free rein to be an equal partner to Roger.

(Abbey of St Evroul)

(Abbey of St Evroul)But not in one matter—religion. Montgomerie supported many churches and abbeys, and even built several abbeys on his different fiefs. The biggest thorn in her side was the Abbey of St Evroul. Religious views likely was one their first clashes of wills. She was determined he curtail the huge fortunes he was placing in the hands of these monks and priests. Roger was very devout, and the religious sects ran their monastery on his largess, frequently prevailing upon him to give more than the general tithing. Tithing was required in ancient times—everyone was to give ten percent of their income to the church. Since he inherited control of her lands through the marriage, coin from her holding of Bellême, in northwest France, was going into the hands of these ever-needy monks without a bye your leave. That didn’t sit well with Mabel. Most of this tale comes from writings of the monks, especially the head of the order—Abbot Thierry. He was Roger’s confessor, so in spite of Montgomerie’s ever growing greed, the abbot proved adept at bending his lord’s will on concerns of the monastery. Thierry heard the man’s confessions. It was reasonable he likely knew Montgomerie’s nature, as well as Mabel’s. Since the strong-willed Mabel’s attempt to curtail their monies, we have to take their reporting of incidents with a thimble full of salt.

(Abbey of St Evroul)

No matter what, Mabel could not influence her husband on this issue, especially this tug of war with Abbot Thierry. Being a cunning woman, she devised an end run. She began visiting the monasteries, with her full entourage. Castles and the monasteries, in medieval times, were basically required to serve as hotels for traveling lords and ladies. Mabel created a win-win situation. She would go traveling the countryside on the excuse of checking on her husband’s vast holdings, along with her one hundred knights and ladies, and various servants. These abbeys dare not offer insult to the countess, or run the risk of Roger withdrawing his support. They were forced to open their gates and all Mabel and her retinue in, to stay as long as they liked. They would have to feed them—and all the horses. Mabel saved money by not feeding the lot at the Montgomerie honours, and she was draining away the supplies bought with her husband’s monies.

The Abbot tried to reason with her, that they were a poor monastery (which was not the truth and she knew it) and it would drain them completely to support her entourage. Mabel was unmoved by his appeals. When he said feeding one hundred knights, and providing for her “worldly pomp” was simply too much, Mabel said fine, she would leave. But—she would return the next week with one thousand knights! Thierry was furious—a mere woman daring to best him. Likely, he knew he was losing this battle of the wills, so he countered, “Believe me, unless you depart from this wickedness, you will suffer for it!” Much to no surprise, a few hours later at supper, Mabel suddenly was seized by stomach pains. She retired for the evening and the queasiness turned to agony. From this distance, we can assume one of the learned monks put something in her supper, and you can bet the incisively smart Mabel knew it, too. Ceding the battle for the moment, she took her troops and left the monastery. The monks were not content with that bit of mischief. On the way home, Mabel stopped at the holding of Roger Suisnar. Still feeling ill—according to the Abbot—Mabel demanded Suisnar he give her his infant child to suckle at her breast. The child drew the poison from Mabel, who instantly recovered. Only the small child died doing it. Mabel knew the monks had poisoned her, but instead of demanding her husband punish them, she wisely never went to the abbey again.