Deborah Macgillivray's Blog, page 4

July 11, 2021

On this day 1274 Robert de Brus, earl of Carrick, king of the Scots was born

11 July 1274: The birth of the future Robert the Bruce, or Robert I of Scotland, at Turnberry Castle.

I have 27 lines (and counting...lol) as Bruce's great-granddaughter. Three at 17th GGF, one st 19th GGF and twenty-three at 20th GGF.

Turnberry Castle, the home of Marjorie Carrick, countess of Carrick in her own right, mother of Robert de Brus.

July 6, 2021

The Women of Bruce — Part 4 —The Sisters of Robert the Bruce — Christian

The Women of Bruce–Part Four –

The Sisters of Robert Bruce–Christian

When I first set up my series of articles on the Women of Bruce, I had intended to devote a single article to Robert the Bruce’s six sisters. However, as I began writing the blog, I found one sister earned her own individual story. For Christian de Brus was a woman to draw admiration and respect. Born about 1273 at Turnberry Castle, she was the third daughter to Robert and Marjorie, and she is likely the most colorful, controversial and tragic Bruce sister.

Like most females of this period in history, little is recorded of her childhood, or her life before she married. Controversy pops up quickly at this point, as it is now fashionable to try and cast doubt that her first marriage ever took place. I cannot follow that trend. Too much evidence says otherwise. Her first marriage was to Gartnait mac Domhnail, Mormaer and 7th earl of Mar, sheriff of Aberdeenshire. Gartnait’s father was a longtime supporter of the Bruces; he was ambitious, and blessed with the farseeing vision to back Clan Bruce. The joining of Mar and Bruce bloods was the perfect balance for future rulers of the country—the Bruces coming from Norman ancestry would see the Lowlanders following them, while the ancient line of Mar would open doors through the old Celtic Scots. With that dream in mind, Domhnall mac Uilleim, 6th earl of Mar set out to see his line woven into the Bruces through a double marriage.

In about 1292, he wed his son Gartnait to Christian. As her bride’s gift from her father, she received the lands of Garioch for her life. The earls of Mar eventually inherited the feudal lordship of Garioch through her (not a peerage dignity) and were even latterly styled the "earls of Garioch”. By the Mars inheriting Christian’s holding–her grandson being the first earl of Garioch–it’s clear that she did wed him. That assumption is further backed up by the holding of Kildrummy Castle, seat of the earls of Mar. In 1305, her brother Robert was in possession of the Mar stronghold. This would indicate the castle went to Mar’s small son, his heir, after his death, and Robert, as his uncle, was acting as guardian for his nephew, controlling the fortress until the boy came of age to accept responsibility of the earldom.

To further back up my inference is wording in the truce made with Edward in January 1302. When Robert saw his fighting for Scotland was only opening the door for the return of King John Balliol—which was basically giving all the power to John Comyn earl of Buchan, and to Red Comyn, Robert gave up the struggle. He made peace with King Edward. It is specific to note in the pact, which can still be read, is a listing of the return of all lands in England, Scotland and France to Robert, and that his people wouldn’t suffer for taking up arms and following him in rebellion. Right in the middle of this avowing is reference to the earl of Mar’s son being given over to Robert as his ward. Why else would this be included in this pact, except Robert was trying to protect his nephew by Christian?

“And the King grants to Robert the wardship and marriage of the Earl of Mar's son and heir. And because it is feared the Kingdom of Scotland may be removed out of the hands of the King’s hands which God forbid and handed over to Sir John Balliol…”

Less than three years after Gartnait wed Christian, Gartnait’s sister, Isabel, would marry Christian’s brother, Robert earl of Carrick (with papal dispensation, naturally). Brother and sister marrying brother and sister, saw Mar blood destined to flow through the child, and future children, that would one day sit on the throne of Scotland.

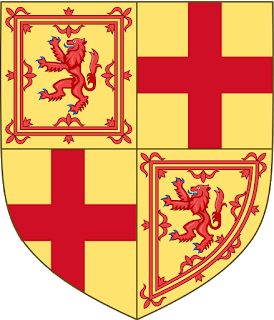

arms of Mar

arms of Mar Christian gave Gartnait a son, Domhnall Mar, and twin daughters, Elyne de Mar and Margaret de Mar. Only, their marriage was short-lived, and his death mysteriously unexplained. Mar was on record as having reconciled with Edward in 1302 and the English king appointed him “warden of Garioch” to enforce Edward’s Peace. Sometime before 1305, Gartnait vanishes from history and not a word of how or why. We might infer he died acting as warden in the troubled times.

If Christian despaired that her life was filled with sorrow at losing her husband, she could little foresee what would come at her in the year following. A little over a year later, in March of 1306, she wed her second husband, Sir Christopher Seton. A close companion to her brother, Christopher was at his side when Bruce faced Red Comyn at Greyfriars Abbey. Some report it was he, not Bruce, who struck the fatal blow to Comyn (though other sources credit this deed to Sir James Kirkpatrick, another close ally of Robert). Legend records Seton saved Robert’s life at the Battle of Methven on 19th June 1306, when the new king fell from his horse. The battle was a total rout, setting the Scots to fleeing.

Ruins of Kildrummy Castle

Robert had sent his second wife, Elizabeth, his daughter by his first marriage, Marjorie, Isabella Macduff (the cousin who crowned him) and his two sisters—Christian and Mary—to Kildrummy Castle. The people of Kildrummy were still devoted to Christian. The stronghold was a formidable one, and clearly Bruce assumed they would be safe there. Their brother Nigel was in command of the castle. When a blacksmith betrayed all by setting a grain store afire, Nigel bravely defended the stronghold, knowing all was lost, giving his sisters and kinswomen time to flee. Nigel lost his life for the valiant effort, along with the entire garrison of the castle. The women were later captured by William, earl of Ross, and turned over to King Edward as prisoners.

arms of Seton

Christian was sent to solitary confinement at the Gilbertine nunnery at Sixhills in Lincolnshire, England. She wasn’t the only female prisoner of nobility housed there. Gwladys ferch Dafydd was the daughter of Dafydd ap Gruffud, the Last Free Prince of Wales. After executing her father for treason, Edward sent Gwladys–a mere child—to the remote Sixhills Priory. She died there in 1336, having spent her whole life as a prisoner to three English kings. While Christian’s fate was grim, it was much kinder than what her sister suffered, and that of Isabella Macduff. That Christian did not face being held in a cage outside also reinforces the validity of her marriage to Mar. The Setons were a family rising in prominence, but held little sway in either country at that time; on the other hand, the powerful earls of Mar traced their lineage back to the early kings of Scotland. Edward could be brutal, cruel; however, he was also mindful of forgiving perceived offenses from nobles–when it was to his benefit. He didn’t dare risk harming Christian for fear the Mars might raise their countrymen against him. Her sister, Mary, was married to Sir Neil Campbell, son of Cailean Mór Campbell, coming from the mighty earls of Argyll. Why that connection didn’t help save Mary from the cage was simple—Neil was one of Bruce’s most trusted lieutenants, and had fought by his side at every point of Bruce’s rebellions. Thus, she suffered the full force of Edward’s vindictive fury.

Sixhills Abbey, Lincolnshire, England

The next we learn of Seton’s whereabouts comes in the attack at Loch Doon Castle. Some try to say he was not at the Battle of Methven, citing his presence at Loch Doon. However, the castle was a vital fortress for the earls of Carrick, and was one of three strongholds that Robert tried desperately to hang on to in order to keep power. It is reasonable to assume, Robert sent Seton there just after the Methven defeat. The castle was built on an island within Loch Doon, and consisted of a formidable eleven-sided curtain wall. Yet, in spite of Seton’s heroic defence, the castle fell the 14th of August 1306. It would not be retaken for another eight years. The castle’s surrender supposedly came by the hand of the Governor, Sir Gilbert FitzRoland de Carrick (son of the illegitimate half-brother to Marjorie Carrick). The truth that would come out much later: it was Gilbert’s brother-in-law who gave over to the English. Christopher was hanged, drawn and quartered at Dumfries in accordance with Edward's new hardline policy of giving no quarter to Scottish prisoners.

Loch Doon Castle ruins

(relocated in 1937 due to raising the level of the loch for a hydroelectric project)

More controversy arises—there is a question that Christian was pregnant with Christopher’s child when she was captured. Possible? Perhaps. As in the question I raised in my last article over concerns that Robert’s queen had been with child –there are no records referring to a child taken as prisoner, nor one born in captivity— I see the same circumstances reflected in this child of Seton. Two different Alexander Setons are listed as her son. One is cited as born in 1252 (which is two decades before Christian’s own birth!) and another as 1290 (at which time she hadn’t married her first husband!). Thus, I surmise it reasonably safe to assume she was neither pregnant, nor had a newborn infant at the time of her capture. Worse, some historians credit her with giving birth to a daughter by Seton before 1306 named Margaret. I think they are confusing her daughter, Margaret de Mar, by Gartnait with a 'daughter' with Seton. Possibly, an attempt of those to forge a link for their family lines to Bruce blood?

Poor Christian even sees historians trying to deny her as mother of the son by Mar. I suppose since they see it as target of choice to refute the marriage took place, so the next step would be to claim the children from that union aren’t hers. Mar’s son was also held prisoner by Edward. The naysayers point to no correspondence between the two during their captivity. It is not hard to envision a man who commanded women held in cages, also capable of preventing correspondence to and from his prisoners.

Christian went on to live as a hostage to the English for eight years. She was made prisoner to Edward I, and it would be another king—Edward II—that would finally recognize her brother as the true king of the Scots, and agree to send the Bruce women home in 1314. Christian returned home to her lands, to children who were nearly grown, and once more she was a widow.

The little over a year after her release her brother, Edward, invaded Ireland, and the following year on the 2nd May 1316 he was crowned king of Ireland. That same year Marjorie Bruce died, giving birth to her son, who would one day be King Robert II. Bruce joined his brother in Ireland for a spell, but by 1318, Edward was slain at the Battle of Dun Delgan on 5th October.

Still, life was far from through with this woman of Bruce. There was talk of another marriage with Sir Andrew Harclay – at the time he was raised from baron of Carlisle to earl– as part of peace talks instigated by Harclay. Nothing came of it. I would guess Christian would not accept an Englishman for a husband. It's just as well they didn't wed, because Harclay was arrested after signing the treaty with King Robert. Edward II had him executed for treason, hanged, drawn and quartered, and his body parts sent to different parts of the country as a warning.

Instead, Christian married a third husband of her choosing—Sir Andrew de Moray. This man was the son born posthumously to the late Andrew de Moray, lord of Bothwell, the same warrior, who fought with William Wallace at Stirling Bridge. Moray, quite possibly, would have been crowned king instead of her brother, had young Andrew not died of wounds received in the decisive battle. It is reported that Christian gave him two sons: Sir John de Moray and Sir Thomas de Moray

arms of Moray

Peace came to Scotland. Edward II died, replaced by his son, Edward III. Then, King Robert died. Christian was there for the coronation of Robert’s son, David II. She had lost two husbands and five brothers at the altar of Scotland, and lived through the reign of three English kings. Even so, Christian was not a lady to sit idle with her spinning and weaving. The English came northward, yet again, this time Edward III, backing the son of John Balliol in claiming he was the real king of the Scots.

After the Battle of Dupplin in August 1332, Andrew was named Regent of Scotland, protecting Robert’s small son, King David II. While attacking Roxburgh Castle in 1333, he was captured and held prisoner for nearly two years. Christian arranged ransom and he was released in 1335. Upon his return, Parliament appointed him Guardian of Scotland. He spent five years fighting the English, and repulsing their attempts to return Balliol to the throne.

Christian was commander of Kildrummy Castle, and while Andrew was away, she found herself besieged later that year by David Strathbogie, a claimant for the title of earl of Atholl — and Edward Balliol’s chief commander in the north. Strathbogie moved through Scotland with fire and sword, repeating the campaign of Edward I of 1296, in a clear attempt to wipe the freeholder lords off the face of Scotland. Laying siege to Kildrummy Castle was to be the pinnacle of his campaign. Only one obstacle lay in his path—Christian de Brus. The fall of the castle would have been a big setback to the Scots, perhaps to the extent of losing the country. Possibly, since the castle had been lost to the Bruces in 1306, in true warrior fashion, Christian held the castle in resolute determination. She refused to surrender, and kept it and its people safe until her husband could march to her aid with an army of over one thousand strong. Thanks to Christian drawing Strathbogie’s attention to focus on the siege, Andrew was able to attack Strathbogie’ from the rear, and even though outnumbered three to one, he defeated David Strathbogie’ at Culblean 30th November 1335. Strathbogie stood with his back to a tree, pinned there, finally killed in a last stand, along with a small group of followers, including Walter and Thomas Comyn. (A side note–Strathbogie was married to the daughter of Hugh de Beaumont and Alice Comyn, niece of the late John Comyn, earl of Buchan – the very pair who were likely responsible for the death of Isabella Macduff, countess of Buchan).

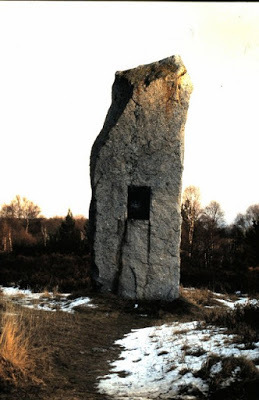

The Culblean Monument

After contracting pneumonia while besieging Edinburgh Castle in the early winter months of 1337, Andrew retired to Avoch Castle in Ross, and less than a year later died, making Christian a widow for the third time. She still retained possession of Kildrummy Castle and so she returned to her home. King David was generous to his beloved aunt, providing her with an income from a number of sources, and his queen, Joan, was said to visit her at Kildrummy as well.

Through those years, tragedy had continually stalked Christian Bruce — brothers, husbands — so many had died. Now, she was forced to watch her children die one-by-one, outliving all but one son. Her first born son by Gartnait, who had spent years as a prisoner to both Edward and Edward II, was appointed Guardian of Scotland on 2nd August, 1332, following the death of Thomas Randolph, 1st earl of Moray (Christian's nephew). The honor was only for a matter of days. On the 11th of August at Dupplin Moor. Mar led the second division of the Scottish army, while Robert Bruce, lord of Liddesdale (Bruce's illegitimate son) led the first division. Mar never saw his 38th birthday. (Odd happenchance — Domhnall's son, Thomas, Mormaer of Mar, 1st earl of Garioch would also die at the same age.) Domhnall was killed, along with Bruce of Liddesdale, who died leading the first charge. Lost as well was Christian's grandnephew, son of Randolph—Thomas Randolph, 2nd earl of Moray. A cousin, Duncan, earl of Fife a lieutenant under Mar (and brother to the woman who crowned Bruce king) barely escaped. After her son's death, her husband had been appointed Guardian.

Margaret de Mar died in 1338 (the same year Christian had lost Andrew); almost nothing of this daughter is recorded, even the cause of death (Historians have her so muddled with the fictional daughter of Seton). Margaret’s twin sister, Elyne de Mar, of Rusky and Knapdale died in 1342 at age 44, cause not given.

At the Battle of Neville's Cross, the 17th of October 1346, King David II (Bruce’s son) was taken prisoner by the English. Along with him was Christian’s elder son by Andrew – Sir John de Moray. Edward III had allowed Andrew to be ransomed—a decision that came back to cost him dearly – so he refused to allow his son to be ransomed. John died in captivity at age 31 (likely from the Black Death) in September of 1351. Christian would have relived every breath of every day for those nearly six years, knowing what her son suffered being held a hostage. If that wasn’t sorrow enough to break anyone’s heart, Edward demanded that John’s younger brother, Thomas, take the place of John after his death. Christian had to watch as yet another son by Andrew was turned over to be an English hostage. The next blow to the family came in losing Christian in 1358. She passed away three years before Thomas. He died at age 35 — also of the plague, in 1361 — also still a hostage to an English king. He was Christian’s only child to outlive her, but only by three years.

As the fashion for women in history, little is recorded of Christian’s death. Her husband, Andrew, had been buried in the chapel at Rossmarkie. Later, his body was reinterred in Dunfermline Abbey, next to Robert Bruce and Thomas Randolph, earl of Moray. Accordingly, one might presume it Christian’s resting place as well. Many of her ancestors and family were buried there—especially her brother, Robert. Due to the Reformation and destruction of the abbey, many of the royal graves were lost. It wasn’t until 1817 that Robert’s grave was found again. Sadly, Christian’s final resting place remains a mystery.

Dunfermline Abbey

Christian Bruce de Mar de Seton de Moray was every bit the warrior her brother was. In return, her legend has suffered the indifference of a history that little paid her life heed, now works to deny her a husband, denied her children by both Mar and de Moray as not being hers, and then contrarily gave her three sons named Alexander and a daughter by a man who was her husband but for a few fleeting months. In the end, it has even deprived her of a final resting place, where people could come to pay their respects. Thousands visit Robert’s tomb each year. How many ask, “Where is the grave of Lady Christian?” Few, if any. Sadly, I fear Christian Bruce will never get the true homage she deserves, simply because she was a woman of Bruce and not a man.

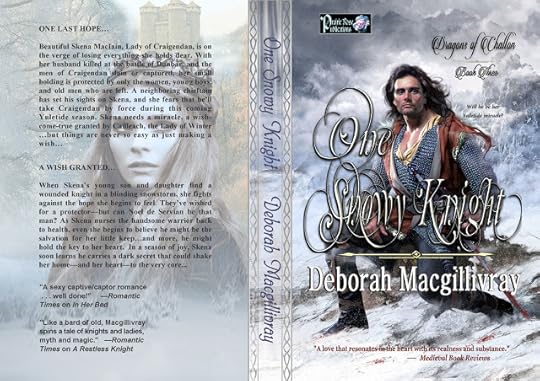

Deborah writes Scottish Medieval Historical Romances

set in the time of Robert the Bruce in a series, the Dragons of Challon.

coming in August

you will meet other sisters of Robert the Bruce in Part 5 -

The Tale of Two Isabels

July 3, 2021

Links to my articles on my women ancestors

Coming in September

Women of Bruce - Part 6 - Sisters of Robert the Bruce--Maud, Margaret and Mary

Coming in August

Women of Bruce - Part 5 - Sisters of Robert the Bruce--A Tale of Two Isabels

Coming in July -

Women of Bruce - Part 4 - Sisters of Robert the Bruce--Christian

Women of Bruce - Part 3 - The Wives of Robert the Bruce

Women of Bruce - Part 2 - Isabel Macduff, countess of Buchan, a woman who crowned a king

- [image error]

The Women of Bruce Part One -- Marjorie Carrick, countess of Carrick

A Tale of Two Women and One Castle - The Ladies of Dunbar - Part Two - Agnes Randolph

[image error]

A Tale of Two Women and One Castle - The Ladies of Dunbar - Part One - Marjorie Comyn

Countess Mabel Montgomerie -- a woman ahead of her times, or a monster in men's eyes

June 12, 2021

The Women of Bruce - Part Three - The Two Wives of Robert Bruce

The Women of Bruce - Part Three

The Two Wives of Robert Bruce

What do we know of the two women that married Robert the Bruce, king of the Scots? There have been four, maybe more films made about Bruce’s life in the last 20 years, all iffy history at best, which is sad since the story of Bruce’s rise from the earl of Carrick to the man who fought his cousin to determine who would claim the crown is a wonderful tale. Did the women who became his brides fare any better? For the most part they were simply omitted, or if included written with questionable inaccurately. Both women were born to be a queen, but only one reached that pinnacle. They were both young, both reputed to be lovely, and both came from lineage that had ancient and royal blood running through the lines.

Isabel of Mar

Arms of Isabel of Mar

Isabel of Mar was born 1278 at Kildrummy, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. She was the first wife of Robert Bruce, and she carried blood royal on both sides of her family. Her father, Donald "Domhnall mac Uilleim" Mar, 10th earl of Mar, whose lineage goes back to origins of Clan Macdonald and “King of the Hebrides”—Somerled. He also was the great grandson of Henry I Beauclerc, king of England, younger son of William "the Conqueror" FitzRobert, duke of Normandy, king of England. An impressive lineage but it is matched by Isabel’s mother—Elen “the Younger” ferch Llywelyn was a princess of Wales, and widow of Mormaer Maol Choluim II, earl of Fife. Her grandfather on her mother’s side was Llywelyn Fawr 'the Great' Llywelyn prince of Wales and Gwynedd, who married Lady Joan Siwan Fitzjohn of Wales, lady of Snowdon, illegitimate daughter of King John of England. So in the marriage to Isabel, Bruce was cementing bonds not only to powerful clans of Scotland, but to the high English and Welsh rulers as well. Isabel was a woman bred to be a queen, the perfect wife to rule at Robert’s side when the time came.

Isabel’s father was an ardent supporter of Robert Bruce, 5th lord of Annandale—Bruce’s grandfather, known as 'the Competitor'—and was there at Annandale’ back during The Great Cause. Of the seventeen lords vying for the crown of the Scots, Annandale was one of the top three contenders, if not the candidate to wear the Scottish crown. And it wasn’t arrogance for Annandale to expect, when all was said and done, that he would become the ruler of Scotland. When Alexander II, his cousin, lacked an heir, the king had name Annandale as tanist—a Scottish term for heir apparent. If Alexander had died at that point in history, Annandale would have become king of the Scots with none to lay challenge. Later, he was Regent of Scotland during the minority of his second cousin, King Alexander III. I am sure it came as a shock, which turned to outrage, when Edward chose John Balliol over him. Edward had deliberately held the Bruces close to him, rewarded them richly in ways he wouldn’t do with other nobles, yet at the back of his mind was the truth—the men of Bruce were not to be taken lightly. The ultimate goal for the English king was to fold Scotland into the kingdom of England, along with Wales, and then to add France.

The Earl of Mar was one of the seven Guardians of Scotland and he had believed Robert the Bruce was the lawful King of Scots. Mar could see great advantage in aligning his family with the Bruces. In 1292, Isabel’s older brother, Gartnait mac Domhnaill, married Robert’s older sister, Christian. Three years later, by papal dispensation, and at the age of 18, Isabel married Robert, earl of Carrick, who was four years her senior. In a time when marriages for nobles were little more than political power moves, legend has it that Robert and Isabel were very much in love. Few were surprised, when a short time later, Isabel was soon with child. They seemed blessed; she had a healthy pregnancy. Late in 1296, Isabel gave birth to a daughter. They named her Marjorie after Bruce’s late mother, Marjorie, countess of Carrick. Then, Fate waved a hand on the night of December 12th, Isabel died at Castle Cardross, on the Firth of Clyde, in Renfrewshire.

Paisley Abbey

Following her death, Isabel of Mar was buried at the Cluniac Paisley Abbey. Her tomb has not survived. In his last act of revenge against Robert Bruce, Edward had the abbey burnt to the ground in 1307, thus destroying both the tomb of Isabel and her daughter Marjorie. William Wallace was born in nearby Elderslie, and is believed to have been educated in the abbey when he was a boy. Scots not being deterred had the Abbey was rebuilt. An eerie circumstance arose when Isabel’s daughter, now grown and married to Walter Stewart, was riding near the abbey and was thrown from her horse. She was pregnant at the time. They carried her to abbey for medical care. I suppose saving the life of a princess came second to the child who might be king. Robert II was born by caesarean section. Considering the lack of anesthetics, it was small wonder she did not recover. Marjorie was interred at the rebuilt abbey, as her mother before her had been once, and as the line of Stewarts after her.

Elizabeth de Burgh

Arms of Elizabeth de Burgh

Elizabeth de Burgh was likely born in 1284 at Connaught Province, Ireland. Some sources cite Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland as her place of birth. However, since her father had been fighting in Wales with the king of England, and another daughter, Eleanor (named after Edward’s queen) was born in Wales, there is an outside chance Elizabeth might have been born there as well. Without question she was conceived in Wales. At this point in history, male historians barely noted the arrival of another de Burgh female, little need in their minds for accuracy of place and date of birth; they never suspected she would be one of the most famous queens of Scotland, her legend only eclipsed by Mary queen of the Scots.

She was the third daughter of seven, out of eleven children of Richard Óg de Burgh, the ‘Red Earl’. He was the 2nd earl of Ulster, 3rd baron of Connacht, Lieutenant of Ireland, Keeper of Athlone, Randown, and Roscommon Castles—and unarguably the most powerful man in Ireland. His wife was Margaret Guines, daughter of Arnoul de Guines III and Alice de Coucy. Margaret was a 2nd cousin once removed of Queen Eleanor. Margaret was also a first cousin of Alexander III of Scotland, Edward I's brother-in-law. Edward was Elizabeth’s godfather. As impressive as Margaret’s lineage was, her husband Richard matched it. He was educated at the Court of Henry III (Edward’s father), thus cementing a lifelong friendship between Edward and Richard. Through the years Richard was Edward’s closest friend and one of his most trusted advisers. At nearly every battle Edward fought in England, Wales and Scotland, Richard was there at his back.

Elizabeth most likely met Robert Bruce, earl of Carrick, at the English Court. The Bruces and de Burghs dancing to Edward’s whims, living and fighting nearly in the other’s pockets, there had to be occasions where both were in attendance. With Isabel Mar’s death in 1296, Robert was a good catch for mothers looking for arranged marriages for their daughters. By 1300, there was some hint Edward was considering giving Robert a new bride. Richard had three daughters of age at the time—Aveline, Eleanor and Elizabeth, the youngest. The second daughter married Sir Thomas de Multon, 1st Lord Multon of Egremont, so that left the other two as candidates. Edward was playing a game of chess with the Bruces, often lavishing money on Robert after he refused to pay homage to John Balliol, and his lands in Scotland were seized in punishment. At Court, he was mocked and called Edward’s Lordling. Some say, Edward paid more attention to Robert than he did his own son. I truly think he hoped by keeping Robert close, he could curb the hunger to be the king of the Scots that had filled Robert’s father and grandfather. And what better way than presenting him with a new wife? Not just any bride—but one that was his goddaughter.

The English invaded Scotland in 1301. In 1302, Robert married Elizabeth at Writtle, near Chelmsford in Essex. Robert would have been close to 28 and she was 18. In 1304, Edward again invaded Scotland to regain control of Stirling Castle. So, it’s not surprising to see the political turmoil around their marriage was coming to a head.

On February 10th, 1306 at Greyfriars, Bruce met with John Red Comyn to settle, for once and all, who would be the future king of Scotland. Comyn or his uncle tried to kill Bruce; in return, Bruce pulled his dirk from his boot and struck back, wounding Comyn. Bruce staggered outside and told his trusted friend, Sir Alexander Seton, that he stabbed Comyn but the man was still alive. Roger de Kirkpatrick rushed inside to see, and came back with the tides that he killed Comyn. Events that would soon propel Elizabeth’s life out of control.

After meeting with the Church of Scotland, it was decided to crown Bruce king as soon as possible. So on 27th March 1306, Robert and Elizabeth were crowned king and queen of Scots at Scone. One might infer Elizabeth lacked faith that her husband’s bold move to be king would be a lasting one, for it is reported that she smiled faintly after the coronation and said, ‘Alas, we are but king and queen of the May that children crown for sport.’ The May Kingand May Queen only rule for one day. On the other hand, perhaps it wasn’t a lack of faith in Bruce’s ability to hold the kingship as much as she understood her godfather’s ruthlessness when betrayed, and knowing also that her father would be backing Edward’s every move to put the new king down. As well, two-thirds of Scotland aligned with Clan Comyn would be the hounds for Longshanks hunting Robert Bruce.

Thus, once again, the English army invaded. Bruce was forced to contend with facing the English, and hampered by raising troops to fight for him. Gold was offered to any man who could bring Bruce in. Bruce had little time to form a strong government, or to raise his army, when he was compelled to meet the English at Methven. Aymer de Valence, the English general acting for Edward I, had not only arrived with an established host of English soldiery and knights, the men of Comyn were flocking to him. To Bruce’s credit he did have very able commanders in James Douglas, Christopher Seaton and Gilbert Hay to lead his troops. Aymer de Valence seemed content to outwait Bruce. In flamboyant fashion, Bruce invited de Valence to leave the walls of Perth and join him on the battlefield. To his mistake, Robert presumed the preliminaries of feudal battle protocol would be observed. When de Valence failed to take up the challenge, Bruce figured there would be no battle that day. He and his forces retired for the night at Methven, expecting to get a good night’s sleep before the coming battle on the morrow. Instead, before dawn, the English attacked and nearly destroyed Bruce’s forces.

Bruce had to scramble to see his family was moved out of harm’s way. He sent Elizabeth, his young daughter by his first marriage, Marjorie, and his sisters Mary and Christian to Kildrummy Castle, under the protection of his brother Nigel. Kildrummy was the castle of Christian’s first husband Gartnait of Mar, and though she was now newly married to Christopher Seton, the people there were still very devoted to her. Bruce, I would assume, thought the English would give chase to him, leaving the women safely out of reach.

Ruins of Kildrummy Castle

Again, underestimating the choices the enemy would make, the English laid siege to the castle containing the royal women. The siege finally succeeded when de Valance bribed a blacksmith with 'all the gold he could carry' to set fire to the grain store. Nigel gave a valiant defense, knowing the castle was lost, but giving time for the earl of Atholl to get the ladies safely away. Nigel was captured alive. He was taken to Berwick to be hanged, drawn and beheaded.

The Bruce ladies were probably heading to the Orkneys, where they would be beyond reach of Edward. Isabel, another of Bruce’s sisters, had married Eric II Magnusson, king of Norway and ruler of the Orkneys. Though Magnusson had died in 1299, Isabel had remained in Norway as dowager queen, and still exerted a great influence in court matter there and abroad. However, the women only made it as far as the sanctuary of St. Duthac at Tain in Easter Ross. There they were captured by a Balliol supporter, William, earl of Ross, who handed them over to Edward I’s men. (Odd side note—less than two years later, Robert’s sister Maud would marry the son the earl of Ross—Aodh 0'Beoland) For his protection of the Bruce women, the earl of Atholl was hanged, drawn and beheaded. His head was displayed on a pike on London Bridge.

Elizabeth spent the next eight years in captivity. While Isabella Macduff, the woman who had crowned Bruce king, and Bruce’s sister, Mary, were taken to Berwick and Roxbury Castle, and hanged over the castle walls to punish Robert, his wife suffered a milder fate. She was housed from October 1306 to July 1308 at Burstwick-in-Holderness, Yorkshire. At first, she was confined with only two elderly women to take care of her needs, and ordered not to speak with her. A letter from her during this period complained about her conditions, that she was limited to three sets of clothing and no headgear or linen bed clothing. That saw a series of moves to other manors and castles—Bisham Manor, Windsor Castle, Shaftesbury Abbey, Barking Abbey and finally Rochester Castle. By the time she reached Windsor Castle, she had been given six servants and an allowance to pay them. She was even permitted to have her pet Irish wolfhounds to keep her company. At this point Edward was long dead, and she was dealing with his son, Edward II.

So why had she been treated so well compared to the dire fates of Isabella and Mary? Simply because she was Richard de Burgh’s daughter. Edward had been planning on invading France for over a decade. He needed men from Ireland to support that invasion, as well to replenish his forces in Scotland to fight Bruce, and de Burgh could do that.

Bruce’s daughter was kept prisoner at the nunnery at Watton during those eight years. But a puzzle surrounds Bruce’s daughters by Elizabeth. They had three daughters: Maud, Margaret and Elizabeth. Not surprisingly, historians seem to have the births of the three mixed up, some even try to deny the existence of Elizabeth, and one says her birth was in 1364 (that is her death). Genealogy sites list the dates of Maud’s birth as 1303, and then Margaret’s as 1307. This seems perplexing. Maud would have been three years old when her father was crowned king and her mother captured, if that were the case. Yet, there is no reference to Elizabeth having a baby with her when captured by the earl of Ross. John Fordun in his Scotichronicon refers to Maud as “did nothing worth recording”. I would think if she had been held captive with her mother, or take from her mother by the English, then Fordun might have deemed her worthy of writing about! And if the second daughter was born in 1307, that would mean Elizabeth have given birth to her after she was a prisoner. Nowhere have I come across any reference to this.

There is no way a daughter could be born until late 1315. If Maud’s actual date were 1315, and Margaret in 1316, that would dovetail with Elizabeth’s birth in 1317, backed up by reference to her as Bruce’s “youngest daughter”.

In the case of this Elizabeth, you will see some sites fail to list her as Bruce’s daughter entirely, or suggest she must be the child of one of his mistresses. Sir David Dalrymple dismisses her out of hand. He declared Fordun had not mentioned Elizabeth, and that he had not seen any charters of land grants to her, and that if any such charters existed they needed to be “deposited in the Register House”. Well, they do exist. There are a number of royal charters, mostly regrants signed by King David II, in which Elizabeth is described as "dilecte sorori me" — my beloved sisteror "dilecte sorori nostre" — our beloved sister. When Dalrymple was shown the proof, he promised to publish a correction to his The Annals of Scotland Volume 2, but he died without fulfilling that promise. Thus, historians referencing Dalrymple today keep perpetuating the lie that she was illegitimate, or not Robert’s daughter at all.

After the Battle of Bannockburn, Elizabeth was moved to York. There, she had an audience with Edward II. In the end, Elizabeth was released as part of the ransom for Humphrey de Bohun, earl of Hereford (Edward’s brother-in-law), who had been captured after Bannockburn on 29th September 1314. In exchange for Hereford’s release, Edward was forced to give voice that Robert was the legal king of Scots, and to return Elizabeth, Christian, Mary and Marjorie, along with the aging Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow. Isabella Macduff was not mentioned in the transfer, but as I expressed in my article for her, I believe she was dead by that time.

After being reunited with Bruce, Elizabeth gave birth to daughters Maud, Margaret and Elizabeth. There were no more children for seven years—miscarriages?—and Bruce likely feared of ever having a son and heir for the throne when Elizabeth became pregnant again. This time, on 5th of March, a son was born. They named him David, and he would go on to be David II, king of the Scots. Another son, John, was born in early October 1327, though little is recorded other than he died soon afterward, likely a short time before Elizabeth’s own death.

Rumors were Elizabeth might have been pregnant again when she was out riding near Cullen Castle in Banffshire when she was thrown from her horse. The circumstances were an eerie echo of the death of Robert’s daughter just ten years before, almost as if Bruce were cursed. Whether it was from illness pertaining to the birth and death of son, John, or perhaps the miscarriage of a child she was carrying, Elizabeth de Burgh closed her eyes on the night of October 27th, 1327 and slipped away from a world that hadn’t been too kind to her. Her entrails were buried in the Church of St. Mary of the Virgin at Cullen and her body was interred at Dunfermline Castle. She was forty-three years old.

Deborah writes Scottish Medieval Historical Romances set in the time of Robert the Bruce in a series, The Dragons of Challon.

May 12, 2021

Women of Bruce - Part 2 - Isabel Macduff, countess of Buchan, a woman who crowned a king

Isabella Macduff Comyn's life was not a happy one.

It didn't start happy. And in spite of one bright shining moment in time, it didn't end happy.

Isabella Macduff, heir to the earldom of Fife and countess of Buchan by marriage, was born at Methil, Fifeshire, Scotland sometime around 1275-80 to the 3rd earl of Fife, Donnchadh Macduff, and his English wife, Johanna de Clare, daughter of Gilbert de Clare, 7th earl of Gloucester and 6th earl of Hertford (He later divorced his first wife and married Edward Plantagenet’s sister). By hapchance, Isabella was also a cousin to two very powerful men, both Scottish earls—one she married by a king's decree, and one she made a king. A pretty Scots lass with bright red hair, the poor lass was but a pawn in the center of games of power and building kingdoms. I seriously doubt anyone ever asked Isabella what she wanted out of life—not in childhood, not in her teen years, and certainly not in her final years as a woman.

Macduff Castle

Isabella's father was a vicious man; hence few were hardly surprised when in 1289 while on his way to Dunfermline, the earl was murdered at Pittillock by his own clansmen. In fear, the English Johanna de Clare took her son (Isabella’s younger brother, Duncan) and fled to England where the two were welcomed warmly by Edward I. Oddly, Isabella, not even eight-years-old, was left behind to be raised in Scotland—possibly because she was the eldest child, and in old Pictish tradition, was the heir of her father, and with that in mind, clan Macduff was not about to let her leave clan control. Little is recorded of her upbringing. My heart breaks thinking of young Isabella living alone, men governing her life, her destiny, while her mother and brother thrived lavishly at the English Court.

By decree of Edward I, king of England, and papal dispensation since they were cousins, Isabella was married in her teens to John Black Comyn, 3rd earl of Buchan, a man over twenty years her senior. John was the head of one of the most powerful families in Scotland. The son of Alexander Comyn, 2nd earl of Buchan, he was also nephew to John Balliol, king of Scotland. His sister was the valiant Marjorie Comyn, countess of Dunbar and March, about whom I have previously written. In Comyn marrying the heiress of another influential clan—this time the ancient one of Macduff—you see a pattern repeated for centuries by Comyn males. They married heiresses, in their own right, drawing these powerful holdings into the Comyn honours, ever increasing and widening their power base and control of the northern half of Scotland. It’s hard to judge, outside the prestige and lands that Isabella brought to the union, if John cared for his young bride. They were wed in 1290, the same year as John’s father died, making him the 3rd earl of Buchan, but it was seven years later before Isabella produced their first child—a daughter she named Isabel. I am reasonably sure John resented Isabella hadn’t produced a son and heir. History almost ignores the existence of this daughter, and it’s clear John certainly tried. However, documents in Edward II’s daily papers dated 3rd December 1308 make references of the female child’s presence, controlling her future and lands, and later, a marriage to the son of Reginald le Chayne, Justiciar of Scotia, so there is little denying her place in history.

Inverlocky Castle, a Comyn stronghold

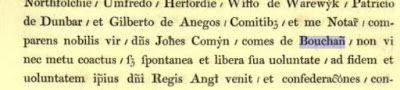

During the Scottish War for Independence, the Comyns—backers of John Balliol (their cousin and uncle)—led the Scottish host at Dunbar, fighting against King Edward. In spite, they were smart enough: they had half of the clan support Balliol, while the other half stayed home or rode with the English. John, on the side fighting against Longshanks, was captured and sent to the Tower of London as prisoner in April 1296. Regardless, Edward was always quick to make peace where it benefitted him. He was planning an invasion of France, and thus needed the most influential clan in Scotland on his side and to supply him men and coin. After the Scottish defeat, and time as prisoner in the Tower of London, you see the earl of Buchan pledging allegiance to Longshanks and reclaiming his lands. John’s name was on the Ragman Roll in August 1296 at Berwick, swearing his fealty to Edward:

Comyn comes de Bouchan, Dominus Johannes

(Johan Comyn comte de Bouchan)

There’s no mention of Isabella being with him. Likely, she was pregnant, and since it was one of the hottest and driest summers ever, and conditions of Berwick on Edward's command saw bodies from the 3-day sack back in April still lying, rotting on the ground, John might not have wanted to risk Isabella losing the baby. In my first Challon novel, A Restless Knight, I make reference to these vile conditions, when Julian and Tamlyn were summoned to Berwick, and how this situation was deliberately created by Edward’s orders to force the nobility of Scotland to witness what happened to a town when they defied him.

Outside the date of birth of her daughter, Isabella was largely ignored by history at this point. Just another woman given in marriage as a reward to a powerful lord. Only, the battle of cousins would soon shape her destiny, and forevermore forge her name into the legend and lore of Scotland.

Her husband’s cousin (and yes, her cousin, too) was also named John Comyn— John Comyn III of Badenoch, called John the Red or Red Comyn. In the vacuum of Longshanks removing John Balliol from the throne of Scotland, the Comyns assumed control of the northern two-thirds of the country—ruling in Balliol’s name—of course. Red Comyn, after all, was the grandson of Balliol. However, as time passed, the mighty Comyn men began to see there would be no hope for returning Toom Taber—the nickname Longshanks hung on Balliol after stripping him of ceremonial regalia of Scotland—ever be king again. The empty throne saw the eyes of both John Comyns on that prize.

John "Red" Comyn, Lord Badenoch

Still, they weren’t the only ones with the same desire—another cousin—Robert de Brus (Bruce), the young earl of Carrick, possessed that very dream in his heart and was resolute to undo the crowning of Balliol in 1292. The Bruces had firmly believed Edward I would rule in favor of Robert’s grandfather, the 5th lord of Annandale instead of Balliol. After all, the man had been designated as heir by decreeby King Alexander II at one point. Since Alexander had produced no sons, he placed the eldest Bruce in the line of succession as heir presumptive in 1238, and he was to follow the king should anything happen to him. A heartbeat away from the dazzling prospect of being sovereign of the Scots created a fire in Annandale, which carried over to his son the 6th lord, and now the same hunger grew inside Robert Bruce, the grandson. Robert was raised tri-lingual, considered one of three men as the first knights of Christendom, had been polished in courtly ways, educated in diplomacy, handsome, arrogant, yet smart enough to play a waiting game—and filled with the belief God intended him to be Scotland’s king.

Some consider the triumph at the Battle of Stirling Bridge was more a victory under the guidance of Sir Andrew de Moray of Bothwell than William Wallace. Moray died of wounds sustained in the battle, so the credit went and still goes to Wallace. That assumption of Moray's military brilliance is upheld for at the Battle of Falkirk, when Wallace led the Scottish army alone, the battle had been lost. After the defeat, Wallace resigned as Guardian of Scotland and left the country. In an effort to balance the power, both Red Comyn and Robert Bruce were named Co-Guardians of Scotland.

Since both men were single-minded to wear the crown of the Scots, the idea of them working together was doomed from the outset. One incident clearly demonstrates how impossible the situation was between the two men. At a meeting after Wallace resigned, a knight—Sir David Graham—a Comyn supporter, demanded the lands of Wallace be forfeit and given to him since Wallace had left the country without the permission of the Guardians. Wallace's brother—Sir Malcolm Wallace—refuted this claim. He knew his brother was actually on a mission for Bishop Wishart in France, and then on to Italy, trying to bring the King of France and the Pope to side with the Scots against the king of England. Bruce ruled in favor of Malcolm Wallace. This in turn set David Graham and Malcolm Wallace to fighting with more than words. Out of the blue, Red Comyn leapt for the throat of Bruce and began strangling him! James Stuart, 5th High Steward of Scotland, and others had to drag Red Comyn away from Bruce. Soon after, Comyn refused to be a Guardian if Bruce remained one; then Bruce said there was no working with Comyn, and quit in 1300.

There is an old Scottish saying: the enemy of my enemy is my friend. That was never so proven as in this time in Scotland’s history. The Bruces had been firmly in Edward's camp, while the Comyns were on the Scottish side backing John Balliol, their kinsman. Edward felt he held control over young Robert. Not surprising since the king had even gifted Robert with a new bride—Elizabeth de Burgh, Edward’s goddaughter. Only, like many ruthless monarchs through the ages, Edward was growing suspicious of his councilors. And though he showed great favoritism toward Robert–even paying his debts when Bruce lands had been seized for refusing to pay fealty to John Balliol—he was increasingly mistrustful about the loyalties of both Bruces. After Edward removed Balliol, Robert's father, Lord Annandale prodded Longshanks to rectify his mistake by placing him on the throne. Edward was said to sneer and reply that he had better things to do than win a kingdom for Annandale. Ever since, Edward held the Bruces close, yet never fully trusted them. And in the case of being paranoid doesn't mean that someone isn't out to get you—Robert was working behind the scenes against Edward's interest.

(yeah, it's Patrick McGoohan playing Longshanks, but I think he did him so well)

Around 1305, Robbie had entered into secret negotiations with Red Comyn—a deal, that they help each other. Not one of Bruce’s brighter plans! One would resign their claim to the kingship, leaving the path clear for the other to seize the crown. In return, the one giving up the claim would receive all the lands and titles of the other. Comyn had another idea. Through the backdoor came Red Comyn, plotting to make another deal for the crown. He turned over these letters from Robert, outlining the details of their pact, in which Comyn basically agreed to step aside so Robert could be crowned king. Instead, Comyn saw this as the perfect opportunity to eliminate his competition.

Unable to contain his fury, the king confronted Robert with the letters and asked if he had written them—after all it had the Carrick seal upon the documents. I am sure Robert was furious by the betrayal, but he kept his head. He replied yes it was one of his seals. Deftly, he pulled on a chain about his neck and produced his official sigil. He went on to explain the seal affixed to the paper was one, but an older seal that he’d left at his castle in Scotland, and protested someone surely had stolen it and was using the wax sigil to frame him. Bruce vowed to get to the bottom of who was the real traitor. Storming out, the Bruce and his entourage headed to his manor house in Tottenham. Barely an hour passed, when someone knocked on the door to Bruce’s room. The man held up his finger to his lips to signal silence, then handed Robert a spur and a gold coin with the face of Edward Longshanks upon it. The message was clear. Arrest warrants had been issued by the English king to seize Robert and his brothers.

Riding hard, the men of Bruce headed to Scotland, escaping arrest by barely an hour. He and his party happened upon a messenger wearing the colors of Red Comyn. The men pursued the fleeing rider and dispatched him. On his body were more letters written by Robert to Red Comyn, and now were being sent to Edward Longshanks.

Once in Scotland, Robert arranged one last meeting with Red Comyn, determined to have it out with the man who was his enemy. With Bruce were Roger de Kirkpatrick of Fleming and Sir Christopher Seton, another powerful noble, who just weeks before had married Bruce's younger sister, Christian. At Dumfries church, Bruce confronted Comyn with the captured letters that were being dispatched to Longshanks. Just as he had at their meeting over William Wallace's lands, when Comyn tried to strangle Robert, Comyn struck out. Someone—either Comyn or his uncle, Sir Roger Comyn, landed a blow with a sword across Robert's chest—his chain mail saving his life. Robert desperately reached for his long dirk, hidden in the side of his cross-laced boot.

When the fight was over, Red Comyn and his uncle, Sir Robert, lay wounded. Robert staggered outside, and told Seton that he had stabbed Comyn, but it was only a flesh wound. As his brother-in-law helped Bruce up and onto the saddle of his horse, Kirkpatrick rushed into the church and killed Comyn. When Kirkpatrick came out and confessed Comyn was now dead, Robert knew there would be no turning back. It was all or nothing. Robert proceeded with haste through Scotland to Scone Palace where he would be crowned King of the Scots.

Miles away, Robert's cousin, Isabella, was unaware of these men’s matters. Her husband John was away in England. One can infer John Comyn, earl of Buchan was in England with purpose—he was the one who carried the first letters and gave them to Longshanks. The messenger that the Bruces had intercepted, bearing more letters, was intended for Buchan. Isabella knew nothing of the Comyn’s plots and plans, or how it would soon propel her young life toward a moment of defiance and victory, and then into the nightmare that would follow.

There was all speed to crown Robert as king before word of what happened would cause all of clan Comyn to hunt him down. In 1296, Edward had removed or destroyed all Scottish regalia—or so he thought—his intent to prevent the pomp and circumstance for placing a crown on a new Scottish king.

Six weeks after Comyn had been killed in Dumfries, Bruce was crowned king of the Scots by Bishop William de Lamberton at Scone on Palm Sunday 25th of March 1306, with all formality and solemnity. Royal robes and vestments that Robert Wishart had hidden from the English a decade before were brought out by the bishop and set upon King Robert. The bishops of Moray and Glasgow were in attendance, as were the earls of Atholl, Menteith, Lennox and Mar. The great banner of the kings of Scotland was planted behind Bruce's throne. Only, they lacked the one thing that every monarch of Scotland had had in their coronation—the earl of Fife putting the crown on the head of the new king.

As expected, tides of Bruce’s killing Comyn spread through the countryside, told, retold and embellished until reaching Isabella. Her younger brother was still in England, and declared by Edward to be the current earl of Fife. Isabella ignored that she had been robbed of her birthright. If her brother wasn’t going to do his hereditary duty, and put the crown on Robert the Bruce’s head, then she was determined to fulfill the role.

Since her lord husband was still in England, she took his valuable destriers, and nearly rode them into the ground, trying to get to Robert in time. When she reached Scone, it was to her disappointment that she arrived one day too late. However, wanting to cement the Bruce’s rights as king, Lamberton suggested they redo the crowning, a second one, two days after the first. So, Isabella, as the true countess of Fife and Buchan placed the crown on Robert Bruce, earl of Carrick, sealing his destiny as the new king of the Scots.

And sealing her own fate as well.

Isabella had just crowned the man responsible for the death of her cousin, Red Comyn, a man who was also cousin to her husband. Worse, her husband was with the English king at the time she was crowning the Bruce, the embarrassment of the deed must have burned inside of John. To add to the insult—she had taken his five destriers and driven them hard to reach Scone. Not just any old horse, mind, these were a knight’s shod chargers, animals valued at $15,000-$25,000 at that period. When jousting, the winning knight claimed a ransom from the loser. Generally, it was their armor or their destrier. Knights often paid these prices to get their mounts back. You didn’t ride a destrier from place-to-place like a regular horse. Knights rode palfreys for conveyance, and had trained horsemen to lead the valuable destriers to destinations. Think of them as the Lamborghinis of horses! She had driven these valuable animals hard to get to Scone, hardly stopping for food and water. Such treatment could cause the animals to founder—a condition where the horses could never bear a rider again.

By coming to Scone, Isabella forevermore cut ties to her husband and Clan Comyn. Bruce recognized this, too. He knew Clan Comyn was coming for him, and soon it would be summer and Edward I would, once again, bring forth his army—nearly a summer event—the invasion of Scotland by Edward Longshanks. Isabella had to go with the Bruce entourage to safeguard her life.

And come for Bruce, they did. Edward had received word, and vowed to ride north to avenge Comyn’s death. Only age and infirmities were beginning to take a toll upon the king, too long a warrior. The whole country wanted Bruce’s head. However, the Scottish church, long backers of the rebellion, remained steadfastly at Robert’s back. He sent for his brother Nigel to fetch his queen, his small daughter, two sisters, Mary and Christian, and the countess of Buchan, and placed them in the care of Kildrummy Castle after he learnt the earl of Pembroke’s army approached. Christian’s first husband was Gartnait, earl of Mar, and she had raised their twin daughters at Kildrummy. Also, Bruce was originally married to Gartnait’s sister, Isabel, and thus his daughter, Marjorie was half Mar blood. The people there would remain loyal to them. In the end, they were forced to flee the castle. Poor Christian’s second husband, Sir Christopher Seton, was captured aiding her brother to escape after the Battle of Dalrigh. For his valiant defense of the Bruce women and for saving Bruce’s life, Sir Christopher was hanged, drawn and quartered by the English along with Nigel Bruce.

Ruins of Kildrummy Castle

In a final desperate move, the Bruce women were given safe passage by John of Strathbogie, 9th earl of Atholl, with the intent to get the women to the Orkneys. Bruce’s sister, Isabel, had married King Eric of Norway, and she was now queen there. They made it as far as the sanctuary of St. Duthac at Tain in Easter Ross. There, they were captured by a Balliol supporter, William earl of Ross, who handed them over to Edward’s men. (Odd side note—Bruce would wed another of his sisters, Maud, to Aodh 0'Beoland scarcely two years later. Aodh was the son of the earl of Ross!). For his role in protecting the Bruce women, Atholl was killed, burnt and his head later set on a pike on London Bridge.

Edward was ever a ruthless king, but in his dealing with the women of Bruce he showed just how merciless he was. Elizabeth de Burgh’s fate was most lenient—after all Edward was her godfather and he had arranged the marriage with Robert Bruce. Her father was Edward’s closest friend, Richard de Burgh, earl of Ulster, a powerful man. Edward needed his support. So, she was placed in a string of different castles under guard, prisoner for nearly eight years. However, she lacked for nothing, including her favorite Irish wolfhounds at her side.

The other women of Bruce didn’t fare so well. Christian was sent to a Gilbertine nunnery at Sixhills in Lincolnshire, England. She was held in a large cage in a room, and not allowed to see anyone, save a single attendant and mother superior to attend to her spiritual needs. It was puzzling Christian’s fate was milder than that of her niece and sister. I can only assume since she was the widow of the earls of Mar and Seton, Edward didn’t wish to anger those clans against him.

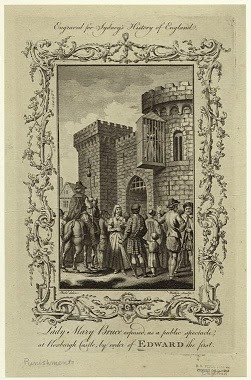

It was with Mary Bruce, Marjorie Bruce and the countess Buchan where he displayed a most ‘peculiar ferocity’. He instructed the three women would be held in cages. He drew up specific designs for them. From Francis Palgrave, Letters of Privy Seal were sent to the Chamberlain of Scotland that he should make cages in the turrets of various royal castles, so they could be hung over the side, and with especially harsh words for Isabella:

Orders originally had been for little Marjorie Bruce to be held in one of these horrid prison. The cage was constructed. But evidently, someone finally swayed Edward's anger long enough to reason that putting a child of barely 10 years old in a cage would be too much for Scots to stomach. She was sent to a convent in Watton instead.

Mary was unmarried, not blessed with a well-connected husband, so I assume Edward felt leave to come down so harshly on her. She was caged in his iron and wood prison on the wall of Roxbury Castle.

Poor Isabella had crowned Robert king of the Scots. And she was married to one of the most powerful men in Scotland—who now held favor with the English king. You might expect her husband to intercede on her behalf, beg for a less harsh treatment. John did nothing. In fact, some historians attributed him saying she needed executing. Attempts to secure her release were made by Sir Robert Keith and Sir John Mowbray, by appealing to Duncan, earl of Fife—her younger brother—but the appeals came to naught. Duncan was too happy being the absentee earl, living high at English Court with his mother, grandfather and new step-grandmother—the king’s own sister.

Her cage was built as a front to a turret, and within was a privy so she could dress and relieve herself without exposing her body to the hecklers gathering and often tossing things at her. However, she was forced to be out in all weather and on display for all to see, but not allowed to speak to anyone. There is some debate as to whether the women were kept in the open. Edward’s own commands tell a story otherwise.

Why did Edward Longshanks treat these women in such a vile manner? Perhaps it was a challenge to the Bruce to come try to snatch them from their captivity. Or he might have been doing an in your face to Robert: These are the women under your protection and you are helpless to save them. The Bruce women were prisoners of the English for nearly eight years, and long after Edward I had died. Some writings of the period, speak that Mary and Isabella were removed from their cages after four years and in 1310 were relocated to nunneries. Mary eventually went on to be returned to her brother in a prisoner exchange under Edward II.

Sadly, fate wasn’t through with being unkind to Isabella MacDuff Comyn. Oddly, her husband died suddenly in 1308 barely forty-eight years of age (two years after his wife was put in a cage). His title was inherited by his younger brother, Alexander, who strangely died at age forty-four, just a couple months after his brother. It was another five years before Isabella was released. Eventually, Edward II had her handed over to Alice Comyn, niece of Isabella and John, and to Alice’s husband, Henry de Beaumont, 1st Lord Beaumont. Immediately after taking control of Isabella, Alice and Henry began calling themselves the countess and earl of Buchan, and Isabella is heard of no more. A peculiar situation overlooked in assessing what happened to her.

Henry Beaumont had an unsavory reputation, and was closely aligned to Piers Gaveston the ‘favorite’ of Edward II–a man Edward Longshanks exiled because of the closeness of his son and Gaveston. Henry and his sister had also been banished from English Court by the Ordainers at the same time as Gaveston for debauched and depraved behavior. His personal battle to hang onto the title of earl of Buchan grew to legend. The title was only valid in England—because in Scotland King Robert refused to confirm Alice and Henry. Beaumont’s battle to regain possession of the earldom was such an obsession that he helped overturn the peace between England and Scotland established by the Treaty of Northampton, and brought about the Second War of Scottish Independence, simply to satisfy his single-minded desire to be earl of Buchan, in his own right. There is little doubt in my mind that Isabella was murdered sometime after her release to Beaumont. If he was willing to destroy the peace between two countries merely to hold onto a title that never really was his, disposing of a weakened woman, who had no champion, would’ve hardly caused Henry Beaumont to blink. At one point, he pushed the powerful Edmund of Woodstock, 1st earl of Kent (half-brother to Edward II) to start a rebellion to put his sibling back on the throne of England—one problem Edward II was already dead!. Henry knew this, but it shows the lengths he would go to merely to claim the title to Buchan.

Of all of the Bruce women captured, Isabella is the only one not to return home. Isabella’s life was little more than a pawn for kings, and an unloved wife of one of the most mighty men in Scotland. But for one bright shining shard of time, she seized fate and chose her destiny. And cruelly paid the price. With Beaumont’s vanishing of Isabella, she was even denied a proper burial, mourning, and a place to pay tribute to the gutsy lass. They robbed her of that last dignity. But they could never rob her of the legacy of a woman who defied all to crown a king.

Women of Bruce - Part 2 - Isabel MacDuff, countess of Buchan, a woman who crowned a king

Isabella Macduff Comyn's life was not a happy one.

It didn't start happy. And in spite of one bright shining moment in time, it didn't end happy.

Isabella Macduff, heir to the earldom of Fife and countess of Buchan by marriage, was born at Methil, Fifeshire, Scotland sometime around 1275-80 to the 3rd earl of Fife, Donnchadh Macduff, and his English wife, Johanna de Clare, daughter of Gilbert de Clare, 7th earl of Gloucester and 6th earl of Hertford (He later divorced his first wife and married Edward Plantagenet’s sister). By hapchance, Isabella was also a cousin to two very powerful men, both Scottish earls—one she married by a king's decree, and one she made a king. A pretty Scots lass with bright red hair, the poor lass was but a pawn in the center of games of power and building kingdoms. I seriously doubt anyone ever asked Isabella what she wanted out of life—not in childhood, not in her teen years, and certainly not in her final years as a woman.

Macduff Castle

Isabella's father was a vicious man; hence few were hardly surprised when in 1289 while on his way to Dunfermline, the earl was murdered at Pittillock by his own clansmen. In fear, the English Johanna de Clare took her son (Isabella’s younger brother, Duncan) and fled to England where the two were welcomed warmly by Edward I. Oddly, Isabella, not even eight-years-old, was left behind to be raised in Scotland—possibly because she was the eldest child, and in old Pictish tradition, was the heir of her father, and with that in mind, clan Macduff was not about to let her leave clan control. Little is recorded of her upbringing. My heart breaks thinking of young Isabella living alone, men governing her life, her destiny, while her mother and brother thrived lavishly at the English Court.

By decree of Edward I, king of England, and papal dispensation since they were cousins, Isabella was married in her teens to John Black Comyn, 3rd earl of Buchan, a man over twenty years her senior. John was the head of one of the most powerful families in Scotland. The son of Alexander Comyn, 2nd earl of Buchan, he was also nephew to John Balliol, king of Scotland. His sister was the valiant Marjorie Comyn, countess of Dunbar and March, about whom I have previously written. In Comyn marrying the heiress of another influential clan—this time the ancient one of Macduff—you see a pattern repeated for centuries by Comyn males. They married heiresses, in their own right, drawing these powerful holdings into the Comyn honours, ever increasing and widening their power base and control of the northern half of Scotland. It’s hard to judge, outside the prestige and lands that Isabella brought to the union, if John cared for his young bride. They were wed in 1290, the same year as John’s father died, making him the 3rd earl of Buchan, but it was seven years later before Isabella produced their first child—a daughter she named Isabel. I am reasonably sure John resented Isabella hadn’t produced a son and heir. History almost ignores the existence of this daughter, and it’s clear John certainly tried. However, documents in Edward II’s daily papers dated 3rd December 1308 make references of the female child’s presence, controlling her future and lands, and later, a marriage to the son of Reginald le Chayne, Justiciar of Scotia, so there is little denying her place in history.

Inverlocky Castle, a Comyn stronghold

During the Scottish War for Independence, the Comyns—backers of John Balliol (their cousin and uncle)—led the Scottish host at Dunbar, fighting against King Edward. In spite, they were smart enough: they had half of the clan support Balliol, while the other half stayed home or rode with the English. John, on the side fighting against Longshanks, was captured and sent to the Tower of London as prisoner in April 1296. Regardless, Edward was always quick to make peace where it benefitted him. He was planning an invasion of France, and thus needed the most influential clan in Scotland on his side and to supply him men and coin. After the Scottish defeat, and time as prisoner in the Tower of London, you see the earl of Buchan pledging allegiance to Longshanks and reclaiming his lands. John’s name was on the Ragman Roll in August 1296 at Berwick, swearing his fealty to Edward:

Comyn comes de Bouchan, Dominus Johannes

(Johan Comyn comte de Bouchan)

There’s no mention of Isabella being with him. Likely, she was pregnant, and since it was one of the hottest and driest summers ever, and conditions of Berwick on Edward's command saw bodies from the 3-day sack back in April still lying, rotting on the ground, John might not have wanted to risk Isabella losing the baby. In my first Challon novel, A Restless Knight, I make reference to these vile conditions, when Julian and Tamlyn were summoned to Berwick, and how this situation was deliberately created by Edward’s orders to force the nobility of Scotland to witness what happened to a town when they defied him.

Outside the date of birth of her daughter, Isabella was largely ignored by history at this point. Just another woman given in marriage as a reward to a powerful lord. Only, the battle of cousins would soon shape her destiny, and forevermore forge her name into the legend and lore of Scotland.

Her husband’s cousin (and yes, her cousin, too) was also named John Comyn— John Comyn III of Badenoch, called John the Red or Red Comyn. In the vacuum of Longshanks removing John Balliol from the throne of Scotland, the Comyns assumed control of the northern two-thirds of the country—ruling in Balliol’s name—of course. Red Comyn, after all, was the grandson of Balliol. However, as time passed, the mighty Comyn men began to see there would be no hope for returning Toom Taber—the nickname Longshanks hung on Balliol after stripping him of ceremonial regalia of Scotland—ever be king again. The empty throne saw the eyes of both John Comyns on that prize.

John "Red" Comyn, Lord Badenoch

Still, they weren’t the only ones with the same desire—another cousin—Robert de Brus (Bruce), the young earl of Carrick, possessed that very dream in his heart and was resolute to undo the crowning of Balliol in 1292. The Bruces had firmly believed Edward I would rule in favor of Robert’s grandfather, the 5th lord of Annandale instead of Balliol. After all, the man had been designated as heir by decreeby King Alexander II at one point. Since Alexander had produced no sons, he placed the eldest Bruce in the line of succession as heir presumptive in 1238, and he was to follow the king should anything happen to him. A heartbeat away from the dazzling prospect of being sovereign of the Scots created a fire in Annandale, which carried over to his son the 6th lord, and now the same hunger grew inside Robert Bruce, the grandson. Robert was raised tri-lingual, considered one of three men as the first knights of Christendom, had been polished in courtly ways, educated in diplomacy, handsome, arrogant, yet smart enough to play a waiting game—and filled with the belief God intended him to be Scotland’s king.

Some consider the triumph at the Battle of Stirling Bridge was more a victory under the guidance of Sir Andrew de Moray of Bothwell than William Wallace. Moray died of wounds sustained in the battle, so the credit went and still goes to Wallace. That assumption of Moray's military brilliance is upheld for at the Battle of Falkirk, when Wallace led the Scottish army alone, the battle had been lost. After the defeat, Wallace resigned as Guardian of Scotland and left the country. In an effort to balance the power, both Red Comyn and Robert Bruce were named Co-Guardians of Scotland.

Since both men were single-minded to wear the crown of the Scots, the idea of them working together was doomed from the outset. One incident clearly demonstrates how impossible the situation was between the two men. At a meeting after Wallace resigned, a knight—Sir David Graham—a Comyn supporter, demanded the lands of Wallace be forfeit and given to him since Wallace had left the country without the permission of the Guardians. Wallace's brother—Sir Malcolm Wallace—refuted this claim. He knew his brother was actually on a mission for Bishop Wishart in France, and then on to Italy, trying to bring the King of France and the Pope to side with the Scots against the king of England. Bruce ruled in favor of Malcolm Wallace. This in turn set David Graham and Malcolm Wallace to fighting with more than words. Out of the blue, Red Comyn leapt for the throat of Bruce and began strangling him! James Stuart, 5th High Steward of Scotland, and others had to drag Red Comyn away from Bruce. Soon after, Comyn refused to be a Guardian if Bruce remained one; then Bruce said there was no working with Comyn, and quit in 1300.

There is an old Scottish saying: the enemy of my enemy is my friend. That was never so proven as in this time in Scotland’s history. The Bruces had been firmly in Edward's camp, while the Comyns were on the Scottish side backing John Balliol, their kinsman. Edward felt he held control over young Robert. Not surprising since the king had even gifted Robert with a new bride—Elizabeth de Burgh, Edward’s goddaughter. Only, like many ruthless monarchs through the ages, Edward was growing suspicious of his councilors. And though he showed great favoritism toward Robert–even paying his debts when Bruce lands had been seized for refusing to pay fealty to John Balliol—he was increasingly mistrustful about the loyalties of both Bruces. After Edward removed Balliol, Robert's father, Lord Annandale prodded Longshanks to rectify his mistake by placing him on the throne. Edward was said to sneer and reply that he had better things to do than win a kingdom for Annandale. Ever since, Edward held the Bruces close, yet never fully trusted them. And in the case of being paranoid doesn't mean that someone isn't out to get you—Robert was working behind the scenes against Edward's interest.

(yeah, it's Patrick McGoohan playing Longshanks, but I think he did him so well)

Around 1305, Robbie had entered into secret negotiations with Red Comyn—a deal, that they help each other. Not one of Bruce’s brighter plans! One would resign their claim to the kingship, leaving the path clear for the other to seize the crown. In return, the one giving up the claim would receive all the lands and titles of the other. Comyn had another idea. Through the backdoor came Red Comyn, plotting to make another deal for the crown. He turned over these letters from Robert, outlining the details of their pact, in which Comyn basically agreed to step aside so Robert could be crowned king. Instead, Comyn saw this as the perfect opportunity to eliminate his competition.

Unable to contain his fury, the king confronted Robert with the letters and asked if he had written them—after all it had the Carrick seal upon the documents. I am sure Robert was furious by the betrayal, but he kept his head. He replied yes it was one of his seals. Deftly, he pulled on a chain about his neck and produced his official sigil. He went on to explain the seal affixed to the paper was one, but an older seal that he’d left at his castle in Scotland, and protested someone surely had stolen it and was using the wax sigil to frame him. Bruce vowed to get to the bottom of who was the real traitor. Storming out, the Bruce and his entourage headed to his manor house in Tottenham. Barely an hour passed, when someone knocked on the door to Bruce’s room. The man held up his finger to his lips to signal silence, then handed Robert a spur and a gold coin with the face of Edward Longshanks upon it. The message was clear. Arrest warrants had been issued by the English king to seize Robert and his brothers.

Riding hard, the men of Bruce headed to Scotland, escaping arrest by barely an hour. He and his party happened upon a messenger wearing the colors of Red Comyn. The men pursued the fleeing rider and dispatched him. On his body were more letters written by Robert to Red Comyn, and now were being sent to Edward Longshanks.

Once in Scotland, Robert arranged one last meeting with Red Comyn, determined to have it out with the man who was his enemy. With Bruce were Roger de Kirkpatrick of Fleming and Sir Christopher Seton, another powerful noble, who just weeks before had married Bruce's younger sister, Christian. At Dumfries church, Bruce confronted Comyn with the captured letters that were being dispatched to Longshanks. Just as he had at their meeting over William Wallace's lands, when Comyn tried to strangle Robert, Comyn struck out. Someone—either Comyn or his uncle, Sir Roger Comyn, landed a blow with a sword across Robert's chest—his chain mail saving his life. Robert desperately reached for his long dirk, hidden in the side of his cross-laced boot.

When the fight was over, Red Comyn and his uncle, Sir Robert, lay wounded. Robert staggered outside, and told Seton that he had stabbed Comyn, but it was only a flesh wound. As his brother-in-law helped Bruce up and onto the saddle of his horse, Kirkpatrick rushed into the church and killed Comyn. When Kirkpatrick came out and confessed Comyn was now dead, Robert knew there would be no turning back. It was all or nothing. Robert proceeded with haste through Scotland to Scone Palace where he would be crowned King of the Scots.

Miles away, Robert's cousin, Isabella, was unaware of these men’s matters. Her husband John was away in England. One can infer John Comyn, earl of Buchan was in England with purpose—he was the one who carried the first letters and gave them to Longshanks. The messenger that the Bruces had intercepted, bearing more letters, was intended for Buchan. Isabella knew nothing of the Comyn’s plots and plans, or how it would soon propel her young life toward a moment of defiance and victory, and then into the nightmare that would follow.

There was all speed to crown Robert as king before word of what happened would cause all of clan Comyn to hunt him down. In 1296, Edward had removed or destroyed all Scottish regalia—or so he thought—his intent to prevent the pomp and circumstance for placing a crown on a new Scottish king.