William Krist's Blog, page 4

March 12, 2025

Trade War Implications for U.S. Agriculture: Round Two

Canada, Mexico and China, the three largest markets for U.S. agricultural exporters, are in the crosshairs of a U.S.-led trade war, and once again U.S. agricultural producers look poised to take the brunt of retaliation.

Canada and Mexico

Since President Trump took office on January 20, 2025, several tariff measures on Canada and Mexico have been announced and then reeled back. There has been a flurry of on-again, off-again tariff announcements. Readers can find the latest news at The White House Fact Sheet website. At the time of this writing, most of the tariffs on Mexico were lifted, but steep tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Canada may still be imposed.

On April 2, President Trump plans to impose “reciprocal tariffs” on goods from a wide range of countries, where the U.S. tariff would match the tariffs imposed on U.S. exports in each country. It has been reported that Canada and Mexico may escape reciprocal tariffs if they continue to make progress on border security and fighting fentanyl.

China

On March 3, President Trump imposed an additional 20% tariff on all Chinese imports (this covers two cumulative rounds of 10% tariffs since he took office. i.e., 10% + 10% = 20%). In response, China announced swift retaliation. Once again, U.S. agriculture is the target of China’s retaliation. Specifically, China is imposing 10% retaliatory tariffs on U.S. soybeans, pork, beef, sorghum, fruits and vegetables, and dairy; and 15% tariffs on U.S. corn, wheat, cotton, and chicken.

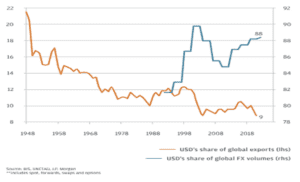

This may feel like déjà vu for many U.S. farmers, who weathered the 2018-2020 trade tensions, including suffering major export losses. Overall, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) reports that China accounts for approximately 17% of U.S. agricultural exports. China remains a key market for many U.S. producers.

Remembering the 2018 Trade War

In 2018, President Trump announced several rounds of tariffs on Chinese imports under Section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974. China wasted no time in retaliating and targeted U.S. agriculture. U.S. agricultural export losses due to the trade war totaled $27.2 billion, or annualized losses of $13.2 billion. The U.S. government provided farmers with financial assistance to help weather the storm, allocating nearly $28 billion in direct payments to farmers over 2018 and 2020. If China and other countries retaliate again, similar export losses may follow.

Soybeans, corn, and wheat were among the commodities that suffered the greatest export losses, alarming industry participants. Within two to three years, however, U.S. export values mostly bounced back albeit with a slightly different country mix. The experience revealed strengths and vulnerabilities in U.S. agriculture. Over the long term, fundamentals like U.S. soil fertility, yield, and innovation work in the sector’s favor. But the growing uncertainty around trade policy and deterioration of U.S.-China relations loom large. As Brad Lubben, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln agricultural economics professor, noted, “Supply chains and markets shifted, with countries like Brazil and Argentina exporting more soybeans to China to fill the demand previously filled by U.S. farmers.”

Will Financial Assistance for Farmers be there Again?

The Trump Administration’s financial assistance to farmers over 2018-2020 was made possible with funds from the Commodity Credit Corporation’s Market Facilitation Program. The Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) is a government-owned entity within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Trump was able to draw upon that USDA account. In 2018, $12 billion was withdrawn to be allocated to U.S. farmers. In 2019, $16 billion was withdrawn for a total of $28 billion (just about matching the export loss U.S. farmers incurred due to the trade war).

The Trump Administration did not require congressional approval for these payments since the CCC already had the authority to disburse funds for farm assistance.

The U.S. government could use the CCC again to support farmers if another trade war occurs, but there are some limitations and political considerations.

For one, the CCC has an annual borrowing limit of $30 billion from the U.S. Treasury. The USDA can unilaterally use CCC funds for farm aid without requiring congressional approval if it falls within the CCC’s mandate.

As of now, USDA still has broad discretion to use CCC funds. There are alternative mechanisms. For instance, instead of using the CCC, the government could provide direct congressional appropriations, although that would require legislative approval. Other emergency aid programs (e.g., disaster relief) could be used if a new trade war leads to farm losses that exceed $30 billion.

The Big Upfront Hits on Key Commodities

China accounted for the vast majority (94%) of U.S. agricultural export losses due to retaliation.

Following China’s retaliation, U.S. exports of soybeans, wheat and corn fell by 77%, 61% and 88%, respectively.

U.S. soybean exporters took the brunt of it, absorbing 71% of the annualized losses caused by retaliatory tariffs; corn and sorghum absorbed 8%. Nebraska also took more than its fair share of export losses—the state represents 4.6% of US agricultural exports but represented 5.6% of the export losses.

Partial Truce

In January 2020, the United States and China called a partial truce and signed the Phase One trade deal, officially known as the U.S.-China Phase One Economic and Trade Agreement. As part of the Phase One deal, the United States agreed to suspend further tariffs and even reduce some existing duties. China agreed to a series of changes that would make it easier for U.S. businesses to operate in China, and to purchasing $40 billion of agricultural products per year on average from the United States for two years. A few months later in March 2020, China began to exempt some products from its retaliatory tariff lists, including soybeans and pork.

China did not fulfill its Phase One commitments although agriculture fared better than other sectors. Chad Bown found that China’s purchases of U.S. agricultural products over 2020 and 2021 reached 83% of the Phase One commitment, which was better than manufacturing (59%) or services (54%).

Non-trade factors are important in understanding post-Phase One activity. For instance, China’s economic slowdown (associated with the global pandemic) likely hindered, in part, its ability to fulfill its Phase One purchasing commitments. Meanwhile, China’s rebuilding of its pig herd, which suffered African Swine fever in 2019, contributed to its expanded pork imports from the United States.

Since the trade war, many industry observers have focused less on import values and more on market shares, specifically, U.S. agriculture market share of China’s imports. By that metric, there was some bounce back to nearly pre-trade war shares, but it appears tenuous. In 2017, the year before the trade war, U.S. agricultural market share (by value) in China was 20%. That share dropped sharply to 12% in 2018 and even further to 10% in 2019. But by 2022, the U.S. share of China’s agricultural imports reached 19%, just one percentage point shy of the pre-trade war share.

However, China has indicated a desire to diversify away from the United States in key agricultural products such as corn and soybeans as a way to shield itself from any fallout from trade wars. Other suppliers including Brazil, Argentina and South Africa are reportedly keen to take advantage of US-China trade tensions—Argentina recently received approval from the Chinese government to ship corn to China.

No Substitute for Market Access

Fundamentals like yields and innovation bode well for the future of U.S. agriculture, but even those advantages have limits. Yields for U.S. major crops tend to be on the higher end across the world’s largest exporters. For the last three marketing years, U.S. yield was the second highest in soybeans, by far the highest in corn, and the third highest in wheat. But Brazil achieves slightly higher yields on soybeans, a crop with relatively low fertility needs. And while Brazil’s corn yields are less than half U.S. yields despite their higher usage of fertilizer, Brazil has two, sometimes three growing seasons for corn.

On innovation, the United States generally has a more robust research and development infrastructure in the ag biotech sector, which will only become more important as agricultural producers struggle to adapt to changing weather patterns and new diseases. Maintaining a strong innovation climate requires the U.S. to maintain its robust patent system and intellectual property rights environment.

Market Relief is Great, but Farmers Seek More Trade and New Markets

In sum, retaliatory tariffs imposed by China and others initially dealt a big blow to U.S. agricultural exports, particularly in key commodities like soybeans, corn, and wheat, and particularly for Nebraska exporters. At first, these sectors exhibited resiliency and U.S. shares in China’s agricultural imports nearly recovered to pre-trade war levels, but now they appear to be dropping off again. Further, while yields and innovation tend to favor U.S. agriculture relative to key competitors, another bruising trade war will further invite other market participants to step in.

Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins initially elicited cautious optimism from U.S. farmers. Her proactive stance in addressing the potential repercussions of trade tensions on U.S. agriculture is welcome, but America’s farmers and ranchers have repeatedly called for greater market access abroad, a science-based agricultural trade policy, and pursuit of strong ag biotech provisions in future trade agreements, which are more consistent with long term viability in U.S. agriculture.

This sentiment was strongly reinforced in American Soybean Association President Caleb Ragland’s recent interview with AgriPulse in which he said, “Market relief is great, but the reality is that it’s a band-aid on an open wound. What we need is trade, free trade, open trade, more of it, new markets, more markets that already exist. We’ve got to find ways to increase demand for our products because long term, that is the only thing that is going to keep the farm economy strong and productive.”

To read the full research blog, please click here.

The post Trade War Implications for U.S. Agriculture: Round Two appeared first on WITA.

The Impact of Trump Tariffs on US-Canada Minerals and Metals Trade

In an escalation of trade tensions, Donald Trump threatened to double tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum to 50 percent this week. This increase would have been in response to Ontario’s 25 percent surcharge on electricity exports to the United States. The threat rattled markets and several major indices continued to decline after the announcement, increasing fears of a recession. While Trump has at least temporarily backed down from the plan to raise the tariff to 50%, the 25% aluminum and steel import tariffs are still a big blow to North American supply chain interdependency and resilience. The following Q&A discusses the impact of Trump’s tariffs on US-Canada minerals trade and its ripple effects on supply chains, prices, and policy. It finds that the tariffs are costly and directly undermine North American supply chain resilience, as no immediate substitute sources are available, domestically or from foreign allies.

1) How have the United States and Canada collaborated on minerals and metals in the recent past?

Recent years have seen the United States and Canada deepen cooperation on critical minerals in response to geopolitical pressures and the need for supply chain resilience, even during the first Trump administration. Under the U.S.-Canada Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals (2020), both governments committed to strengthening cross-border supply chains, co-investing in extraction and processing, and aligning policies to support North American industrial capacity. There is extensive cross-border investment in critical minerals. For example, about 323 Canadian companies have invested over $45 billion in the US mining sector.

2) How large is the US-Canada minerals and metals trade?

There is a huge interdependence between both countries. The two countries are each other’s biggest export and import partners. In 2023, out of $57 billion in total minerals and metals exports, Canada exported $38 billion in minerals to the United States, or two-thirds of its total exports. In the same year, out of $114 billion in minerals and metals exports, the United States exported $28 billion to Canada, or about 25 percent of total exports. This figure also includes non-critical minerals like iron.

3) How much will the new tariffs cost?

Canada exports $13 billion of aluminum to the United States and $17 billion of iron and steel. Those now must pay 25 percent tariffs, implying an additional cost of $7.5 billion annually. When other minerals and metals are required to pay the 10 percent tariff that would apply to them, the costs will go up further. Canada exported $4 billion of copper in 2024 and $1.5 billion of nickel. These costs will undoubtedly impact the downstream producers, affect their competitiveness, the ability to offer jobs, and finally, the costs for the final consumer via inflationary trends.

4) Can Canadian minerals and metals be substituted by domestic production?

Not really. In terms of reserves and production, the United States and Canada are largely complementary. The United States holds significant global reserves in molybdenum (23 percent), tellurium (11 percent), lithium (4 percent) and silver (4 percent). Canada adds to that with significant reserves of niobium (9 percent), selenium (6 percent), titanium (4 percent), and lithium (3 percent). For other strategic minerals, the countries each hold smaller shares of global reserves, but they often produce more. If critical minerals security of supply is truly a strategic goal, then it is important to protect that production and facilitate, at the local, national, and regional level, responsible expansions where feasible. In terms of production, the complementarity is largely similar. The United States produces significant global shares of beryllium (56 percent), molybdenum (14 percent), zirconium (7 percent), zinc and copper (6 percent each), and silver (4 percent). Canada is a significant producer of niobium, cadmium, palladium (8 percent each), nickel, aluminum, tellurium, indium (4 percent each), selenium (3 percent), and copper (2 percent).

5) Can Canadian exports be substituted by other foreign partners?

In some cases, yes, but those supplies would not necessarily come from partners that the United States has historically been keen on relying on. Canada was the second largest source of iron and steel for the United States after China. Canada was the largest source of aluminum for the United States, with China in second place. Canada was the largest source of nickel for the United States, followed by Russia. Copper is a different case. Canada is second to a historically US-allied country, Chile, but Chilean copper production has been struggling and cannot easily pick up the slack.

6) Has the uncertainty already impacted metals markets?

Market volatility has already increased due to the tariffs. Steel and aluminum prices have experienced spikes, leading to supply uncertainty and increased costs for US stakeholders. The combination of tariffs and retaliatory measures from Canada and Mexico has disrupted supply chains across multiple industries. While price effects depend on long-term policy implementation, historical precedent suggests that import tariffs on metals often result in higher costs for downstream manufacturers. The uncertainty surrounding compliance with USMCA and additional tariff exemptions has further complicated investment decisions, particularly in the US industrial sector.

7) What are the potential impacts of the Trump tariffs beyond prices?

The tariffs could have broader implications for North American supply chain integration, industrial competitiveness, and workforce mobility. The US mining and refining sectors have already faced talent shortages due to underinvestment, leading experienced professionals to retire or move abroad. The tariffs could also discourage Canadian professionals from relocating to the United States, further exacerbating domestic capacity constraints. Additionally, higher costs for raw materials could reduce North American competitiveness in sectors such as batteries, clean energy, and defense. Retaliatory measures from Canada and Mexico could also affect broader trade relations, creating additional uncertainty for investors.

8) What steps could be taken to create a more collaborative policy path for the United States with Canada?

The Trump administration could take several steps to strengthen minerals cooperation with Canada. First, aligning regulatory frameworks under the USMCA could facilitate cross-border investment in mineral extraction and processing. Second, expanding joint stockpiling and refining initiatives, including co-financing projects through mechanisms such as the Defense Production Act, would enhance supply chain security. Third, ensuring that US legislation—such as the IRA and CHIPS Act—consistently recognizes Canadian minerals as “domestic” would remove trade barriers. Finally, fostering workforce development initiatives, including mutual recognition of mining and refining certifications, could help address industry-wide skill shortages.

To read this blog as it was posted by the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia SIPA click here.

The post The Impact of Trump Tariffs on US-Canada Minerals and Metals Trade appeared first on WITA.

March 3, 2025

2025 Trade Policy Agenda and 2024 Annual Report

A Trade Policy for the Next Great American Century

The United States of America is the most extraordinary nation the world has ever known. From the very beginning, and even more so as it unfolded across the entire continent, the United States was populated with people of immense talent, drive, and grit. In the previous century it saved the entire world, dispatching three rounds of adversaries by winning two world wars and defeating Communism. It put an American on the moon.

The United States accomplished those feats because it was a tremendous industrial power fueled by innovation and blessed with abundant agricultural and energy resources. Indeed, the very success of the American way of life—its freedom and its prosperity—is supported by two things: a robust middle class earning high wages and a strong national defense. These are, in turn, created by a combination of innovation that fuels productivity growth, domestic work and investment in industry, and the day–to–day choices of individual Americans.

Today, the upward mobility offered by the manufacturing sector is not widely available to the working

class, much of our industrial might has moved overseas, and innovation has begun to follow. Manufacturing jobs in the United States declined from 17 million in 1993 to 12 million in 2016.1 Over 100,000 factories closed between 1997 and 2016. 2,3 And the U.S. goods trade deficit has soared to over a trillion dollars.4 These trends are the product of a withering, decades–long assault by globalist elites who have pursued policies—including trade policies—with the aim of enriching themselves at the expense of the working people of the United States. As a result, the middle class has atrophied, and our national security is at the mercy of fragile international supply chains.

President Trump alone recognized the role that trade policy has played in creating these challenges and how trade policy can fix them. Since he first took the oath of office in 2017, President Trump has reshaped the trade policy landscape to prioritize the national interest. He has built a new consensus that tariffs are a legitimate tool of public policy. He has demonstrated the imperative for tough trade enforcement against countries who think they can take advantage of the United States and get away with it. He has shown that the United States has leverage and can negotiate aggressively to open markets for Made in America exports, particularly for agricultural exports. He has proven that a robust and realist trade policy can create jobs, promote innovation, strengthen the national defense, raise wages, support farmers, and foster the manufacturing renaissance that many elites long thought was impossible for the United States to achieve.

Toward a Production Economy

To reach these objectives, the United States must have an economy focused on production. For much of our history, the American way of life was defined by creating, inventing, building, growing, and producing. Americans are more than just what they consume. And the United States is more than an economy that merely moves money around—it is a nation of intertwined communities, oriented around the production of manufactured goods, agricultural products, services, and knowledge. Ensuring that trade policy favors a Production Economy will help the President Make America Great Again.

Why? It’s simple:

A Production Economy is a high-wage economy. Manufacturing jobs have a wage premium of roughly 10 percent. However, as the United States deindustrialized, that wage premium declined for manufacturing workers in core production jobs. Using trade policy to increase the number of manufacturing jobs in our country – and the share of manufacturing contributing to gross domestic product – will help raise wages and return our country to one with a more vibrant and secure middle class.

A Production Economy creates jobs for all. Trade policy does not need to pit workers or sectors against each other. This is because manufacturing is a sector known for positive spillovers, including in the service sector, that benefit the economy overall. One study found that for every additional manufacturing job created in a community, 1.6 jobs were created in other sectors.6 And agriculture-related jobs—work that produces the sustenance vital for human life—comprise about 10.4 percent of total U.S. employment.

A Production Economy is a boon for innovation. Between 2003 and 2017, research and development (R&D) expenditures in China by U.S. multinationals grew at an average rate of 13.6 percent per year, while R&D investment by U.S. multinationals in the United States grew by an average of just 5 percent per year. Deploying trade policy tools to create incentives to reshore manufacturing will reverse this troubling trend and promote U.S. technological dominance.

A Production Economy is a vital component of our national defense. The United States was able to win World War II because of our industrial might, but our manufacturing base has atrophied. Although the United States produced less than 14,000 aircraft in the two decades prior to World War II, it produced 96,000 planes annually by 1944.9 By comparison, today the United States can only produce each month about a third of the 360,000 artillery rounds the military says it needs to deter our adversaries. Trade policy can help strengthen our defense industrial base.

Changing this alarming trajectory requires a trade policy that is strategically coordinated to achieve three things: an increase in the manufacturing sector’s share of gross domestic product; an increase in real median household income; and a decrease in the size of the trade in goods deficit.

An America First Trade Policy

On January 20, 2025, President Trump signed the Presidential Memorandum “America First Trade Policy” laying out a plan to accomplish the transformational change necessary to reverse our country’s economic decline. The Presidential Memorandum instructs USTR and other agencies to undertake rapid, unprecedented work to put America First on trade.

Right away, the Presidential Memorandum strikes at the threat posed by the trade deficit by directing USTR and other agencies to “investigate the causes of our country’s large and persistent annual trade deficits in goods, as well as the economic and national security implications and risks resulting from such deficits.” By reversing the flow of American wealth to foreign countries in the form of the trade deficit, the United States can reclaim its technological, economic, and military edge.

The Presidential Memorandum further instructs the USTR to review our country’s economic relationship with all nations in order to identify their unfair trade practices, including where trading partners engage in non-reciprocal trade with the United States. By identifying, and acting against, such unfair and non-reciprocal practices, the United States can use its leverage to open new markets for U.S. exports and re-shore the production that has been lost.

USTR has been empowered to chart a new course for any trade agreements to ensure they help raise wages and grow our industrial base. USTR will review existing trade agreements to guarantee that those agreements operate in the national interest. For instance, third countries should not be permitted to free ride on our trade agreements with other trading partners. Alongside this review, USTR will commence the statutorily required public consultation process of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in order to “assess the impact of the USMCA on American workers, farmers, ranchers, service providers, and other businesses” in preparation for the mandated review of the agreement in July 2026. USTR will also identify opportunities for bilateral or sector-specific plurilateral agreements that might be negotiated to open new market access for U.S. exports and reorient the trading system to promote U.S. competitiveness.

The Presidential Memorandum also addresses U.S. trade relations with the People’s Republic of China, the single biggest source of our country’s large and persistent trade deficit and a unique economic challenge. In his first term, President Trump negotiated a historic and enforceable Economic and Trade Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the People’s Republic of China (also known as the Phase One Agreement). However, there has been no action taken to enforce the agreement where China has not lived up to its commitments. USTR will assess China’s compliance with the Phase One Agreement.

The Phase One Agreement grew out of USTR’s investigation under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 into China’s acts policies, and practices related to technology transfer, intellectual property (IP), and innovation. Yet, technology and IP-intensive sectors are hardly the only ones that are threatened by China’s non-market behavior. USTR will look broadly at the bilateral relationship to identify, and respond to, additional unfair practices.

President Trump’s interest in addressing challenges in the relationship with China complements significant interest by the U.S. Congress on the topic. Pursuant to the Presidential Memorandum, USTR will assess the recent legislative proposals related to China’s Permanent Normal Trade Relation (PNTR) status and “make recommendations regarding any proposed changes to such legislative proposals.”

Taken together, these workstreams signal a national commitment to continuing the America First approach to trade developed in President Trump’s first term of office. By taking a strategic, yet vigorous, approach, the United States can finally address the structural challenges distorting the global trading system in ways that undermine U.S. competitiveness and course-correct for the short-sighted trade policy mistakes of the past.

Building on Past Success

To summarize: over the last several decades, the United States gave away its leverage by allowing free

access to its valuable market without obtaining fair treatment in return. This cost our country an important share of its industrial base and thereby its middle class and national security. Although many sectors benefitted from trade, it was at too high a price—for example, despite its comparative advantage in agricultural production, the United States has even incurred a worrying trade deficit in agriculture over the past two years.

Going forward, the United States will take action to create the leverage needed to rebalance our trading relations and to re-shore production, including, but not limited to, through the use of tariffs. This will raise wages and promote a strong national defense.

Importantly, this America First Trade Policy builds upon President Trump’s accomplishments from his first term.

• Though promised by Presidents past, but never accomplished until his first Administration,

President Trump successfully renegotiated NAFTA. Its replacement, the USMCA, contains

historic provisions to re-shore manufacturing (especially in the auto sector, which had been

decimated by NAFTA), the strongest labor and environment provisions in any trade agreement,

new market access for U.S. agricultural products, and high-standard digital trade rules.

• Under his leadership, the United States entered into two important agreements with Japan, opening

new access for U.S. agricultural products and securing USMCA-style digital trade rules.

• The United States also engaged extensively at the WTO, calling attention to and defending U.S.

rights to take action against non-market policies and practices and reclaiming American

sovereignty from unaccountable foreign bureaucrats.

• The United States responded assertively to China’s unfair trading practices, negotiating the Phase

One Agreement to protect U.S. firms against China’s forced technology transfer and IP theft and

imposing significant bilateral tariffs at the same time.

These past successes on trade demonstrates the wisdom and efficacy of President Trump’s America First approach.

First, the proof is in the pocketbook: In 2001, the year China joined the WTO, real median household

income in the United States (measured in 2023 dollars) was $70,020. In 2016, the comparable figure

was $73,520—real median household incomes had grown only 5 percent in sixteen years.11 That’s an

annual average growth rate of 0.3 percent. Then, from 2016 to 2019, the last year before the U.S.

economy was disrupted by COVID-19, real median household incomes had grown to $78,250—an

increase of 10.5 percent over the course of only three years.12 That’s an average annual growth rate of

3.4 percent, over ten times the annual average growth rate that prevailed from 2000 to 2016. By putting America First on trade, President Trump restarted our Production Economy in a single term; something prior Presidents failed to do for a generation.

Further proof is in our newfound national security strength resulting from President Trump’s first term. An America First posture, complemented by new investments in our industrial base, showed that the United States is still a superpower. President Trump’s first term peace dividend brought benefits not only to Americans, but also to the rest of the world.

Lastly, one of the most satisfying pieces of evidence for the America First approach is its bipartisan

credibility: all of President Trump’s first term trade accomplishments were retained by the next

administration and, in some cases, even expanded upon.

President Trump’s ability to deliver for all Americans while forging a new consensus on trade validates his inaugural pledge: the trade challenges facing our country will “be annihilated” because “from this moment on, America’s decline is over.”

2025 Trade Policy Agenda WTO at 30 and 2024 Annual Report 02282025 -- FINAL

To read the complete report as it was published by the United States Trade Representative click here.

The post 2025 Trade Policy Agenda and 2024 Annual Report appeared first on WITA.

How the US Courts Rewrote the Rules of International Trade

Shaina Potts’s Judicial Territory examines how the American legal system created an economic environment that subordinated the entire world to domestic business interests.

Consider the following two stories involving legal disputes between American companies and foreign governments.

In 1919, the ocean steamer The Pesaro sailed from Genoa, Italy, for New York City. Built in Germany for a German shipper and formerly named the SS Moltke, the steamer had been seized by the Italian government in 1915 after Italy entered World War I. On board for its departure to America four years later were 75 cases of artificial silk owned by a company incorporated and based in the United States called the Berizzi Brothers. When The Pesaro arrived in New York after two weeks at sea, however, the Berizzi Brothers cried foul: Only 74 cases of silk were delivered. One had been lost or damaged in transit.

Eighty-two years later, a dispute on an altogether larger scale began. In 2001, with Argentina’s economy mired in recession, the country defaulted on around $93 billion of government debt, in what was then the largest sovereign debt default in history. Though a portion of that debt was owed to foreign governments, the default primarily involved private bondholders such as institutional investors. Most of these creditors would eventually agree to restructure the debt for cents on the dollar (thus booking losses), but a minority of the debt holders refused to accept this “haircut.” Like the Berizzi Brothers eight decades earlier, these holdouts, too, were based in the United States, namely a group of Wall Street “vulture funds” that had invested in the debt at distressed prices.

Beyond the fact that both cases pitted American firms against foreign governments, what links these stories is that the firms in question sought legal redress for their grievances. Not only that, but they sought this redress specifically in American courts, and thus by appeal to US law. The Berizzi Brothers sued for $250 in damages; the vulture-fund owners of the Argentinian debt sued for full face value plus interest.

The Berizzi Brothers’ case ended up in the US Supreme Court, and in 1926 the company lost, which is to say that the Italian government won. The Pesaro was owned and operated by Italy, and it was well established under US law that foreign governments (and their oceangoing vessels) were immune from suit in domestic courts. Yes, the Italian government was engaged in this case in a commercial activity, but it was so engaged, the court ruled, in a public rather than private capacity and with a public purpose.

But the Argentine government would not prove so fortunate, twice finding itself on the receiving end of negative legal judgments in its battle with the vulture funds. The first was when the US courts decided in 2012 in favor of the creditor holdouts, ruling that the full bond value was indeed due. The second followed Argentina’s subsequent decision—highly unusual among sovereign debtors in recent decades—to stand firm and continue to not pay up. While the US courts could not directly make Argentina pay, they could and did make life extremely uncomfortable, issuing rulings from 2012 to 2014 that indirectly forced the Argentine government’s hand by prohibiting it from making payments to other creditors unless it paid the holdouts first, and by prohibiting anyone anywhere in the world except Argentina from helping the country make such payments.

This pair of legal battles prompts a number of questions: What role does the law play in the arbitration of economic disputes? How does the direct involvement of sovereign states in such disputes affect that legal function? And what difference does it make when legal and economic disputes involving governments spill across national borders? These concerns have once again moved to the fore, with an explicitly protectionist and imperially minded president having taken the reins of power in America. The transition from The Pesaro and silk to Argentinian bonds and American vulture funds is an essential backdrop against which to answer these questions. In the course of eight decades, US courts seemingly made a decisive turn against foreign governments, stacking the deck in favor of American companies and becoming, in the process, a handmaiden to American empire.

The two stories with which we began effectively bookend the account of transnational commercial law that Shaina Potts, a geography professor at UCLA, provides in her new book, Judicial Territory. Potts’s study is capacious, offering insights on everything from financialization and hegemony to international trade and globalization. But at the core of the book is the history of how we got from US courts being willing to rule in favor of foreign governments and against American firms in the 1920s to the opposite outcome in the 21st century.

In a nutshell, that history is a chronicle of expanding US judicial authority over the economic decisions and activities of foreign governments, and in particular their relationships with private—usually American—companies. Governments that had previously been treated as sovereign and immune, such as the Italian government in its ownership and operation of The Pesaro, are no longer accorded such deference by US courts. Foreign states and their commercial dealings had not formerly been beyond the reach of US power altogether: The United States’ executive branch had rarely granted them immunity, especially when American interests were involved. What changed was that the US judiciary started to treat foreign governments exactly like private corporations, robbing them of any special legal status. This, as Potts describes it, was an epochal shift.

The change began in earnest in the 1950s and ’60s, and it was initially centered on what came to be termed “the Third World” and on developments in various postcolonial countries. Independence for such countries was frequently followed—albeit sometimes not until decades later—by the nationalization of foreign-owned assets and by the establishment in their stead of state-owned enterprises. Bolivia, for instance, nationalized its tin mines; Turkey nationalized its railways, ports, and utilities; Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal; and countries ranging from Iran to Mexico nationalized their oil industries.

Such nationalizations, which were integral to the plans of developing countries for a New International Economic Order, had long been regarded as beyond the purview of US law. But after World War II, a shift gradually occurred, and American courts increasingly came to treat the nationalization of US assets as unlawful expropriation. The nationalizations in Cuba on the heels of its revolution—Castro famously nationalized all American-owned sugar companies in 1960—were a particular flash point and are given special attention by Potts.

The path from The Pesaro to Wall Street vulture funds, and the markedly different legal treatment accorded to the latter, were enabled by transformations—halting, uneven, and in certain respects still ongoing—in two main legal doctrines that had historically insulated foreign governments from US courts. The first concerned foreign sovereign immunity rules: Who and what were immune from lawsuits? In the 1950s, both the who and the what began to be understood by US jurists in more restrictive ways, with the result that the commercial acts of foreign states—such as Italy’s conveyance of silks to America—lost their former immunity (through the so-called “commercial exception”).

The second key doctrine was “act of state.” This international legal principle asserts that acts carried out by sovereign states in their own territories—such as nationalizations—cannot be challenged by other countries’ courts. Historically, US courts fully respected this doctrine, but by the 1960s they’d started to chip away at it. In particular, commercial acts came to be excluded, just as they were from foreign sovereign immunity rules. Increasingly, it didn’t matter to US courts who a business operator or asset owner was: The activities and possessions of all economic actors (be they public or private) were no longer protected by the rules of sovereign immunity and acts of state.

The expansion of US judicial authority that resulted from the parallel transformations of these two doctrines has been as audacious as it has been largely unnoticed outside of narrow legal circles. It has also been multidimensional: While the juridical encroachment on foreign sovereignty has perhaps been most notable in cases of financial contracts (with creditor rights typically being privileged, as with Argentina’s debt), the phenomena newly falling within the ambit of US law are far more extensive. Anything that conceivably could be subjected to the transnational application of US domestic commercial laws has been. This includes, for example, cigars: A landmark case was Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba (1976), in which the US Supreme Court ruled against the Cuban government, which had nationalized the cigar industry and subsequently refused to return the money mistakenly paid to it for pre-nationalization cigar shipments by importers in the United States. All that has been required to bring foreign governments to heel, Potts shows, is to successfully argue that the relationships or activities in dispute are “merely economic” (that is, private and commercial) rather than public and political, which is an argument that US courts have been increasingly happy to accept.

Meanwhile, alongside this expansion of what is litigable in the United States, more striking still has been the expansion of who can be sued and where the relevant activities or assets are located. Today, no sovereign government can operate without the risk of falling afoul of US laws and being held so accountable, and this is true wherever in the world they happen to be operating. Indeed, while making foreign governments subject to US laws for what they do in America is one thing, making them subject to these laws for what they do elsewhere, including in their own countries, is something else entirely. Yet that is precisely what has come to pass.

In 1990, the Nigerian government found itself embroiled in a US court case involving a contract it had awarded for the construction of a military hospital in Nigeria. Why? One American firm had accused another of having secured the contract through the bribery of Nigerian officials. The US Supreme Court decided that it did have the power to adjudicate the bribery accusation, thus reminding foreign governments the world over that they cannot deal with American firms, even at home, without considering how US courts will judge those dealings. (President Trump has recently weighed in on the appropriate course of judgment, telling US jurists to stop ruling against such bribery: “It’s going to mean a lot more business for America,” he said.) As Potts insists, it is surely a sea change of profound political significance that, over the course of several decades in the post–World War II era, the US legal system has “helped make the whole world part of US economic space.”

The transformations discussed in Judicial Territory are, as Potts admits, familiar ones to certain legal experts and well documented by legal historians. The particular importance and value of her new account lies in refusing the idea—implicit if not always explicit in the bulk of the existing literature—that this is merely a technocratic history, consisting merely of technical juridical tweaks. This process was not technocratic whatsoever, but partisan and nationalistic—thoroughly political from start to finish.

To begin with, the timing of the commencement of this shift in legal treatment—in the 1950s—was anything but happenstance. It coincided both with an upsurge in the socialist and postcolonial nations pursuing economic development models that prioritized domestic populations and industries rather than multinational (increasingly, US) capital, and with the diminishing potential for powerful Western countries to strangle those upstart development models in ways they had in the past. The American courts’ growing subordination of the international arena into merely another jurisdiction of US domestic law is part and parcel, then, of a longer and larger historical policy of containment.

Hence, the history that Potts narrates refuses technicist readings every step of the way. Behind the expansion of US judicial reach in the second half of the 20th century was the desire and determination of US government and corporate actors to tame statist national economic models overseas and to nip in the bud any developments remotely inimical to the interests of US capital. Much of the richness of Potts’s account is found in its careful identification of the primary nonjudicial actors (the private companies, investors, and policymakers with intimate connections to both constituencies) that animated and motivated these historical juridical transformations.

The value and importance of Judicial Territory also lies in Potts’s assessment of the consequences and indeed intrinsic nature of the massive expansion of US judicial authority. One of the most enduring puzzles of the postcolonial age has been the question of why previously colonized countries so frequently failed to flourish once the colonizers were sent packing and formal sovereign status had been achieved. Potts does not exactly situate her study as an answer to that question, but an answer—one adding to and complementing a range of existing answers—is nonetheless what she indubitably provides. Postcolonial nations have widely failed to thrive, Potts effectively argues, because in reality they remained part of a de facto empire, although in this case an American as opposed to a British, German, or Spanish one; and this has served to undermine their nominal sovereignty.

In fact, the refreshing thing about Potts’s book is that she makes no bones about it: Imperialism is clearly what we are dealing with here. But it is a different type of imperialism, one where exogenous judicial authority increasingly stands in for military or executive authority. Her book is a call to treat the United States as an imperial power precisely (although not exclusively) because of this extension across international space of US legal authority and, correspondingly, of the interests of US capital. Potts writes of the latter-day American empire evincing a “judicial modality”—of foreign sovereign nations and their peoples being subordinated to America by law rather than by colonial occupation or military force.

What is perhaps most insidious about the “imperial modality”—another striking Potts framing—of US judicial power is the extent to which it was designed to quietly snuff out “postcolonialism.” The expansion of US judicial territory after World War II, Potts writes, “enabled the United States to continue exercising substantial authority over the decisions of foreign governments in an age of avowed anti-imperialism and formal sovereign equality.” More than that, the turn to law was a mechanism of the active disavowal of empire. “The recoding of many foreign policy issues as merely legal,” Potts notes at one point, “has been an especially potent way for the United States to obscure its own imperial operations.” Or, as she puts it elsewhere, the trick has been “to cloak the pursuit of US geopolitical and geoeconomic goals (always entangled to a large degree with private corporate interests) in the guise of the ‘rule of law.’”

For that, of course, is the thing about law: its self-professed impartiality and, well, judiciousness. A modern-day empire rooted in law, of all things? The very idea seems counterintuitive, absurd even. Yet that is what Judicial Territory presents us with: empire camouflaged by the veneer of fairness that the law furnishes. If, as Carl von Clausewitz famously argued, war is merely the continuation of politics by other means, then, for Potts, law—at least the transnational application of domestic American commercial law—represents the continuation of empire by other means.

Just as Indigenous populations worldwide resisted the imposition of foreign occupation and rule that was European colonialism, so too have national governments worldwide—to varying extents and with varying degrees of determination—resisted and challenged the postwar expansion of US judicial authority. Potts recounts many such examples of confrontation. The Cuban government has long been a particular irritant for the United States in this respect, repeatedly and robustly arguing against the overreach of American judicial authority.

But Potts is also clear-eyed about the fact that, for the most part, these challenges have ultimately been in vain: “Once judicial decisions are made,” she observes, “most foreign governments do obey them most of the time.” But why? After all, as Potts notes, “transnational law is not backed directly by the enforcement power of the police the way domestic law is.” Her answer emphasizes the chilling impact of the economic blackballing that routinely comes with not conforming: “Foreign governments simply cannot afford to be locked out of US markets or legal services.”

The case of Argentina’s defaulted debt and the vulture-fund holdouts appeared, at least, to represent something of a counterpoint to this tendency. When the US courts initially ruled in 2012 that the country did have to pay the vulture funds in full, Argentina continued to refuse to do so. It held firm.

But that was not the end of the matter. As mentioned, the courts proceeded over the next two years to ratchet up the pressure further—effectively blocking Argentina from paying its other bondholders unless it first paid the holdouts in full—and in the end, the government buckled: In 2016, it settled with the vulture funds to the tune of more than $10 billion. Why? Argentina had essentially been excluded from the international capital markets while making its stand, compounding its domestic economic strife. Settling with the holdouts enabled Argentina to restore its credibility in the markets, issue new debt, and take measures to stabilize its economy.

In the end, Argentina had no real choice, besides isolationism, other than to settle. Settling was structurally required of it, given the country’s dependent positioning in the circuits of international finance. Economists call this structural bind “international financial subordination,” by which they mean that fundamental inequality in the global financial system structurally subordinates less powerful states and constrains their financial autonomy. What Potts has brought to light with Judicial Territory is the crucial role of the law in fashioning and enforcing such subordination—that is, in demanding and securing the obedience of sovereign states.

And the vulture funds? They made out like the bandits. According to data published by the courts in conjunction with the 2016 settlement, the funds each earned returns on investment of between 300 and 1,000 percent. But in its own analysis of the numbers, The Wall Street Journal found that one fund, Florida’s Elliott Investment Management, had actually achieved a return of up to 1,400 percent.

Elliott was very much the public face of the vulture funds in the lengthy battle with Argentina, receiving endless brickbats for its leading role in facing down the Latin American sovereign. Indeed, the normalization of the term “vulture” to refer to Elliott and the other investment funds involved in the litigation plainly indexed the way they were widely viewed: as operating somehow beyond the acceptable pale. “Elliott is the ugly face of America,” one critic, capturing the mood, exclaimed in 2018.

But to suggest that an investment fund such as Elliott is an aberration from contemporary American capitalism is to miss the point entirely. Insofar as it trades on the rule of law that the United States propagates and exercises globally, Elliott is American capitalism’s globalizing arm, its vanguard rather than black sheep.

Argentina’s government was demonstrating an “inexhaustible disregard for the rule of law,” Paul Singer, Elliott’s founder and president, opined in a letter to his clients at the height of the dispute. In 2014, a banker who’d done business with the firm was asked by a journalist what made Elliott so successful. “They have deep respect for the rule of law and they expect others to share it,” the banker said. But what would happen if Singer and his colleagues ever sensed that others did not share this “respect”? “I think you know the answer,” the banker replied.

To read the article as it was posted on The Nation website, please click here.

The post How the US Courts Rewrote the Rules of International Trade appeared first on WITA.

That’s What (Economic) Friends are For: Guiding Principles to Boost Supply Chain Security

The United States has recently pursued “friendshoring” of supply chains to trusted countries in the Indo-Pacific as part of its efforts to reduce dependence on China and make supply chains more resilient to global shocks. Friendshoring initiatives include plurilateral forums such as the Minerals Security Partnership and the Chip 4 Alliance, as well as initiatives to bolster bilateral economic relationships with Indonesia, Vietnam, and India, among other countries.

However, the implementation of U.S. friendshoring policy has met its fair share of challenges, including how potential tariff increases may impact its viability. Moreover, it is not always clear who is a “friend” of the United States, and there is uncertainty about the longevity and durability of the “friendship” classification. In addition, the increase in U.S. policies (and dollars) supporting domestic production – for example, through the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act – seems to be somewhat at odds with the goal of friendshoring to strengthen trusted supply chains. Furthermore, friendshoring policy reinforces trends toward the bifurcation of the global economy along a U.S./China split, contributing to a slowdown in global economic growth.

In interviews with Indo-Pacific experts both inside and outside government, the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI) heard that while U.S. engagement in the region is welcome, there are also some frustrations with the friendshoring policy. Interviewees bemoaned the lack of real economic benefits for their countries from initiatives to date and highlighted their disappointment with U.S. policies that subsidize domestic production, especially when they cannot compete with such incentives. The recent political positioning around Nippon Steel’s attempted acquisition of U.S. Steel was cited as undermining trust among friends of the United States. Respondents also emphasized the difficulty of excluding China from their supply chains, with several stressing the importance of balancing ties with China and the United States.

As the new administration considers the future of this policy, ASPI recommends bolstering friendshoring policies by adopting five guiding principles:

Strategic focus: Working closely with the private sector, focus friendshoring first on a limited number of strategic sectors in line with U.S. priorities, such as chips, critical minerals, and pharmaceuticals, and expand to other sectors over time.

Certainty: Take a long-term approach to building confidence among friends by situating friendshoring policy in a new, comprehensive U.S. economic security strategy. This would provide a clear direction, certainty, and consistency of application for friendshoring policy.

Expanding membership: Look beyond traditional partners to include trusted developing economies that will provide greater access to resources and supply networks for businesses.

Substantive benefits: Strengthen the benefits of friendshoring for both sides, including gains in market access, collaboration on research and development, and increased support for capacity building.

Engagement: Ensure that engagement with trusted partners – and the U.S. business community – goes both ways, creating ample opportunities for early discussion and feedback on new initiatives.

Introduction

The United States, like many other countries, has seen its economy become increasingly intertwined with China’s over the past few decades. However, the risks of overdependence on China, especially in critical sectors, are rising more to the fore and spurring action. At the same time, the potential for global trade disruptions from external forces such as climate change, pandemics, and geopolitical tensions is on the minds of many businesses. As governments and businesses look to shore up their supply chains to tackle these challenges, they are quickly coming to the realization that not everything can be made at home. A strong economic security policy requires the United States to consider how it can build resilient supply chains through effective partnerships with its friends and allies – the so-called friendshoring policy.

This paper examines the rise of the United States’ friendshoring policy over recent years and delves into some of the challenges and tensions that have arisen from the implementation of this policy in the Indo-Pacific. Valuable perspectives on the U.S. friendshoring policy from experts across Asia are shared. Finally, five guiding principles to enhance this policy are recommended for the new U.S. administration.

The Rise of U.S. Friendshoring Policy

In April 2022, then–Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen articulated a U.S. policy “favoring the friendshoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries,” arguing that doing so would allow the United States to “continue to securely extend market access” and thereby “lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners.” While other terms like “ally-shoring” had already gained currency, Yellen and others in the Joe Biden administration latched onto “friendshoring” as a key plank of U.S. economic security policy. The objectives were twofold: to reduce the United States’ economic dependence on China and to better respond to global supply chain shocks, such as the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, Yellen explained that the United States would focus on strengthening supply chains with countries that “have strong adherence to a set of norms and values about how to operate in the global economy and how to run the global economic system.”

The Indo-Pacific has become a key region for implementing effective friendshoring policy. The launch of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in May 2022 offers an illustration of friendshoring policy in action. A key goal of the 14-member IPEF is supply chain resiliency: this was the first pillar of work to be concluded in May 2023, reflecting both lessons learned from the disruptions of the pandemic and a keen eye on the risks of overdependence on China. Amid growing concerns about China’s dominant role in the critical minerals sector – China is the world’s largest producer of 28 metal and mineral commodities – the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) was also established in 2022. Comprising 14 countries plus the European Union, the MSP was designed to accelerate the development of diverse and sustainable supply chains of critical minerals. MSP countries have launched 32 projects to date, including several focused on upstream mining and mineral extraction. The Chip 4 Alliance between the United States, Japan, Republic of Korea, and Taiwan is an example of efforts to bring together key allies in the Indo-Pacific with the goal of building resilience across the semiconductor supply chain and lessening China’s role in this strategic industry.

Alongside these plurilateral economic initiatives, the United States has strengthened its bilateral trade relationships with key economic partners in the Indo-Pacific as part of its friendshoring push. For example, in 2022, India and the United States launched the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology, which supports the development of high-tech industries in India, including enhancing semiconductor supply chains. The United States also elevated its relationships with Vietnam and Indonesia to the level of “comprehensive strategic partnerships” and bolstered its cooperation with these two important Southeast Asia players to support and improve, inter alia, semiconductor supply chains and, in the case of Indonesia, critical minerals.

A Bumpy Path for Friendship: Challenges in Friendshoring Policy

While the United States has pursued friendshoring with some vigor in recent years, the implementation of the policy has encountered its share of challenges.

Who is a “Friend” of the United States?

One of the first tough issues to work through is the definition of friendship: Who is a “friend” of the United States? The Trump administration’s recent announcements of new U.S. tariffs that could be applied to friends and allies alike will no doubt make Indo-Pacific friendshoring partners and businesses pause for thought on the future economic engagement of the U.S. with its ‘friends’. For its part, the Biden administration often described friendshoring policy as applying to “trusted” partners, and those countries that espouse a common set of values about international trade. Japan has long been a trusted partner and friend of the United States, and it is committed to the international rules-based trading system. The United States and Japan have also worked together in forums such as the G7 and IPEF to enhance supply chain security. However, former President Biden’s decision in January 2025 to block the acquisition of U.S. Steel by Nippon Steel, citing national security concerns, raised questions about the durability and reliability of the “friendship” category. In the wake of this, friendshoring partners may well question whether their friendship with the United States is enduring or will be limited to certain situations at the whim of the U.S. government.

Friendshoring has also been described as involving countries with which the United States does not have any geopolitical concerns. The reality is that countries’ policies can, and indeed do, change over time. This means that while a country may be considered a friend at one point, the relationship may later change in a way that makes supply chains between that country and the United States difficult, inadvisable, or even impossible. For example, the extent of Chinese investment in a country or a county’s level of engagement with Beijing may, over time, lead the United States to view that country less favorably. We are seeing heightened U.S. concerns about Chinese companies moving production to other Indo-Pacific countries and exporting to the United States from those countries to avoid U.S. trade restrictions and benefit from tariff advantages. For example, Vietnam’s and Mexico’s imports to the United States have grown, but at the same time their imports from China have grown even faster, and Chinese investment in manufacturing in those countries is rising. Indeed, a 2023 World Bank report found that the reduction of U.S. imports from China may not have diminished dependence on China because countries that were more deeply engaged in Chinese supply chains saw the fastest growth in exports to the United States.

Were the United States to go so far as to exclude a friendshoring partner from the supply chain because of increased Chinese investment there, that would mean a reversal of fortunes for the friendly country. This potential uncertainty around the longevity of the “friend” classification poses a challenge for businesses that are looking for certainty and stability when they consider investment decisions.

The definitional issues extend to questions about whether countries that have been identified as “friends” for supply chain purposes (and where the United States is actively encouraging closer economic ties) are in fact reliable partners with which the United States has no geopolitical concerns. Vietnam, for example, has been a part of initiatives to strengthen supply chains with the United States, including those in critical sectors like semiconductors, but it has also been included on the United States’ list of countries that raise national security concerns for dual-use goods, meaning that specific export controls apply.

Inconsistencies with Onshoring Policy

At the same time that it has been pursuing friendshoring policy, the United States has also been ratcheting up its industrial policy and subsidizing production at home in recent years – the so-called “onshoring” policy. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), passed by the U.S. Congress in 2022, set out an ambitious plan to support climate and clean energy technology. This includes tax incentives and credits for electric vehicles assembled in North America and domestic production of clean energy components like solar panels and wind turbines. Since its passage, more than $265 billion in clean energy investments have been announced, contributing to $900 billion in total manufacturing investments.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) and the CHIPS and Science Act (2022) also provide financial incentives for building semiconductor manufacturing plants in the United States, and include “Buy America” provisions that mandate the use of some domestically produced materials for federally funded infrastructure projects. Dozens of companies have committed to nearly $400 billion in semiconductor investments across the United States, spurred largely by the CHIPS and Science Act’s incentives program.

On the face of it, onshoring policies focused on supporting domestic production seem to be somewhat at odds with the goals of friendshoring, which are about strengthening international supply chains. While in some cases, U.S. domestic policies offer incentives that certain foreign countries may be able to access, this mechanism is not the same as friendshoring of supply chains. Limitations on which countries can access the incentives, such as a provision that countries must have free trade agreements with the United States, are also problematic given that many “friends” of the United States do not have such agreements in place.

The increase in U.S. subsidies for domestic production also creates an uneven playing field. The effects of these measures are especially acute for countries that cannot afford to provide similar incentives to support production at home. While Secretary Yellen commented that friendshoring is “open and inclusive of advanced economies, emerging markets, and developing countries alike” and that the United States is “working to strengthen – not weaken – our ties with the emerging and developing world,” these industrial policies may run counter to such goals. Indeed, significant incentives to manufacture in the United States effectively diminish the competitiveness of many emerging and developing economies in global supply chains.

Increased Bifurcation of the Global Economy

Friendshoring is also contributing to the bifurcation of the global economy along U.S./China lines. International Monetary Fund researchers concluded that friendshoring trends could lead to a more fragmented global trade network and the loss of 2% of the world’s gross domestic product. Developing countries, which would otherwise benefit from more foreign investment, are most vulnerable to the loss of economic output. Similarly, when the World Trade Organization considered the implications of the war in Ukraine, it predicted that if supply chains were reoriented based on geopolitical blocs, global GDP would drop by 5% in the long run as a result of restrictions on competition and the stifling of innovation. Countries that try to operate in both blocs would be faced with duplicative supply chains, creating significant inefficiencies and raising costs.

Perspectives from the Indo-Pacific: Friendshoring Is Welcome, but It’s Not All Plain Sailing

The success of the United States’ friendshoring policy relies on its friends around the world – but what do those friends think of the policy? To gain insights into the Indo-Pacific region’s view of this policy, ASPI interviewed experts from across the region to hear their frank assessments of the implementation of the U.S. friendshoring policy. Interviewees discussed how the policy has been received in their countries, as well as whether, and how, it could be strengthened. These interviews were conducted in the last quarter of 2024. The experts interviewed included current and former government officials, businesspeople, academics, and senior researchers from think tanks in India, Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam.

Overall, the interviewees gave the U.S. friendshoring policy mixed reviews. They noted that the region welcomes stepped-up U.S. engagement and increased cooperation to strengthen supply chains, but they also expressed frustrations with the limited benefits that so-called friends receive. There was also some confusion among friendshoring partners about the mixed messages coming from the United States about the importance of onshoring versus friendshoring. The United States’ Indo-Pacific partners were also cognizant of their strong economic ties to Beijing and the need to balance relations with both the United States and China.

The Importance of Concrete Benefits

Most experts agreed that it is important for the U.S. friendshoring policy to provide benefits to both sides. While Secretary Yellen commented that “achieving resilience through partnering with Indo-Pacific countries means gains for Indo-Pacific economies as well,” several interviewees noted that, from an economic perspective at least, friendshoring had not brought them substantial benefits. One interviewee commented that “the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and Minerals Security Partnership are examples of friendshoring, but they focus more on geopolitical considerations, like reducing dependence on China, rather than offering real economic benefits. Without market access, it’s hard to see substantial gains from joining them.” Furthermore, one interviewee expressed the view that friendshoring is “not sustainable in the long term unless the U.S. provides clear incentives for allied countries.” Another expert pointed to a real lack of benefits compared with traditional trade agreements. Others commented that the benefits of friendshoring for partners are simply “unclear.” Some interviewees were nevertheless pragmatic that the current friendshoring policy is “the best that we can get from the U.S. right now” and that “it’s better to have it than not have it.”

Still, some respondents identified tangible benefits for their countries, such as greater U.S. investment in key sectors, stronger supply chain integration, improved business collaboration, increased strategic economic ties, and benefits for specific sectors where the United States is trying to lessen China’s role. Others found the policy aligned with broader trade and investment goals. For example, one expert commented that friendshoring is useful for those seeking greater openness to foreign investment in the United States, while another highlighted the value of friendshoring in terms of boosting business confidence, given that the United States is “still engaging in the region.”

Concerns About U.S. Onshoring and Domestic Policies

A number of respondents expressed concerns about U.S. domestic policies, with both confusion and frustration arising from the perceived inconsistency between some domestic policies and friendshoring. One expert commented that “on the one hand, the U.S. says, ‘you are our friends,’ but then they pass policies like the IRA that hurt their friends.” Another expert similarly noted that “the U.S. is very keen on promoting growth back home, with policies like the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS [and Science] Act providing subsidies to incentivize companies to move production back to the U.S. This sometimes creates confusion or tension between supporting supply chains overseas or bringing them entirely back to the U.S.”One interviewee remarked that U.S. subsidies supporting domestic manufacturing were undercutting plans in their own country to become a manufacturing hub; this was a double hit because their country is not eligible for any of the IRA’s tax credits. Some experts added that while they had raised their concerns with U.S. officials, communication was not always easy, and they did not believe their concerns had been adequately addressed by the Biden administration.

The politicization of Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel was also cited by some interviewees as a move that had undermined trust in friendshoring – one that would have a lasting effect, and not just for Japan. One expert summed it up as “friends are not always aligned 100% but you need trust in the relationship.” There was a sense among several interviewees that the United States was prioritizing its domestic industries at the expense of its so-called friends. In this regard, one respondent observed that friendshoring worked best when the friend was complementing the U.S. initiatives, rather than trying to compete.

De-risking From China is Difficult

Respondents emphasized that their supply chains remain largely intertwined with China, not least because of their free trade agreements with China. Balancing the competing interests of relationships with the United States and China was important to players in the region given their heavy economic reliance on China. One expert remarked that “just cutting off the supply chain with China is not easy – it’s almost impossible.” Another explained that in their view, the economic calculations for business will always play out first, and “if producing in China makes the most sense, companies will continue there.” Nevertheless, a few interviewees acknowledged that a growing number of companies are relocating from China to other parts of Asia as they seek more stable production sites.

For some, keeping their relationships with China and the United States balanced meant that increased engagement through the U.S. friendshoring policy resulted in a need to boost engagement with China too. Yet other interviewees commented that the friendshoring policy did not significantly alter their country’s relationship with China. Some noted that the two relationships are not mutually exclusive – they want to benefit from both relationships and prioritize economic benefits over ideological alignment. One respondent commented that many in Southeast Asia prefer the term “like-minded” rather than “friend” because it avoids being strictly aligned with the United States or China and “reflect[s] our position of not taking sides.”

Views on Friendshoring Entangled With Broader Attitudes Toward the United States

Many interviewees commented on how the friendshoring policy impacted public sentiment in their countries toward the United States. One interviewee noted a persistent trust deficit with the United States in their country, but added that friendshoring was one initiative that was helping this to move in the right direction. Some countries also raised questions about the long-term reliability of U.S. engagement in the region. This concern resonated with a 2024 report from the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute on “The State of Southeast Asia,” which found that China continues to be seen as the most influential economic power in Southeast Asia, outpacing the United States 59% to 14%. China also edged past the United States to become the prevailing choice if Southeast Asia were forced to align with either China or the United States. While multiple factors contributed to this shift in public sentiment, reversing this trend may require greater clarity on how the region can effectively participate in U.S. economic strategy.

Enhancing Friendshoring Policy: Guiding Principles

Considering the objectives of the friendshoring policy, the challenges identified, and the perspectives shared by interviewees in the Indo-Pacific region, five principles should be adopted to enhance U.S. friendshoring policy. Many of these principles apply equally to the United States’ Indo-Pacific partners as they shape their own approach to building greater economic resilience.

Strategic focus: Working closely with the private sector, focus friendshoring first on a limited number of strategic sectors in line with U.S. priorities, such as chips, critical minerals, and pharmaceuticals, and expand to other sectors over time.

Certainty: Take a long-term approach to building confidence among friends by situating friendshoring policy in a new, comprehensive U.S. economic security strategy. This would provide a clear direction, certainty, and consistency of application for friendshoring policy.

Expanding membership: Look beyond traditional partners to include trusted developing economies that will provide greater access to resources and supply networks for businesses.

Substantive Benefits: Strengthen the benefits of friendshoring for both sides, including gains in market access, collaboration on research and development, and increased support for capacity building.

Engagement: Ensure that engagement with trusted partners – and the business community – goes both ways, creating ample opportunities for early discussion and feedback on new initiatives.

Principle 1: Strategic Focus

Friendshoring policy should focus first on areas of greatest strategic interest to the United States, as well as areas in which reducing supply chain dependence on China and increasing resilience are most critical. The Administration should work closely with the private sector to identify these sectors given business’ expertise in shaping supply chains and their interest in stability and certainty.