William Krist's Blog, page 3

April 16, 2025

Trump Trade Negotiations: Embrace Strategic Trade, Not Autarky

U.S. trade policy lacks nuance and strategy. Free traders want free trade for everything. Protectionists want protection for everything. Free traders are happy for other countries to subsidize their exports, and if those countries are dumb enough to subsidize American consumption, let ‘em. Protectionists, meanwhile, get riled up if any imports are subsidized.

It’s time to apply a strategic lens to U.S. trade policy. If nations want to subsidize their exports of commodity goods like minerals, lumber, and dairy products—have at it. We’ll take the discount. In contrast, if they want to subsidize exports of advanced goods like semiconductors, steel, and autos—no way. These are predatory moves designed to destroy U.S. capabilities in critical industries permanently.

This Manichaeism runs deep. During the Obama administration, I met with a top White House economist. He had just come from a high-level meeting where an even more senior economist successfully argued that if China wanted to dump solar panels (i.e., sell below costs), they were the dumb ones. The United States should allow it because our consumers would benefit. (That economist’s initials might have been L.S.) He advocated for this because he believed no industry was more important than any other. And so, we lost our solar panel industry.

Now we have a White House that decries all foreign export subsidies and sees all goods-producing industries as equally important.

Neither protectionists nor orthodox free traders fully grasp the essential political economy of international trade. This critical blind spot has profound consequences for policy. It is time to embrace a Hirschmann-oriented trade policy.

Albert O. Hirschmann, in his seminal work National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade, articulated what many economists overlook: Trade creates power relationships and dependencies between nations that extend far beyond simple economic efficiency. Trade patterns shape geopolitical leverage, vulnerability, and autonomy in ways standard economic models simply cannot capture. And advanced industries play a key role in shaping that power.

Orthodox free traders—steeped in the economic frameworks of Keynes, Hayek, and traditional neoclassical models—often treat trade as a purely economic phenomenon, divorced from political reality. They analyze tariffs and subsidies solely through the lens of efficiency, ignoring how trade dependencies can become geopolitical weapons. This explains why free traders consistently underestimate the strategic implications of becoming reliant on potential adversaries for critical inputs or technologies.

While protectionists intuitively grasp that economic dependencies matter, they typically lack a systematic framework for distinguishing genuine strategic vulnerabilities from special interest pleading. As a result, groups like the Coalition for a Prosperous America push to protect American ranchers and farmers, even though foreign trade barriers will never eliminate these industries in the United States. We have too much fertile land for that. This leads to blanket protections that undermine competitiveness without addressing core national interests.

The key is that advanced industry goods and services are fundamentally different from commodity industries. When a nation positions itself as a leading provider of high-value goods and services, it captures premium margins that fuel growth and innovation. Focusing on advanced sectors creates virtuous cycles in which expertise, capital, and talent converge, spurring further innovation and maintaining competitive advantages, including military capabilities. Nations that lead in critical technologies and services also gain diplomatic leverage and influence global standards, securing long-term market advantages.

Finally, unlike commodity goods, producing advanced goods takes considerable effort: capital, skills, R&D, learning, and scale economies. Once a nation’s competitive position is weakened by subsidized imports, the outcome is usually preordained—erosion of domestic capabilities with the ultimate result of near-total loss. These industries face high fixed development costs and require access to large markets to bring average revenues below average costs.

For example, it is highly unlikely that Boeing could have afforded to design and build the 787 jet if it could only sell in the United States. And if Boeing loses market share due to foreign subsidies (as it has in China and the EU) its revenue, and therefore its R&D investment, will decline, making it less competitive relative to COMAC and Airbus. The reality may not just be a decline in production, but the loss of the firm itself. America has already seen this in many industries, including telecom equipment, machine tools, and solar panels. It is highly unlikely that we will ever get them back, absent a CHIPS Act-like policy response.

President Trump rightly complains about foreign subsidies of commodity imports to the United States. But even with the threat of massive tariffs on foreign nations, he is unlikely to get everything he wants. He will have to decide which issues are the most important to press our trading partners on and which we can live with. We can live with Canadian tariffs on dairy imports. The result is a smaller U.S. dairy industry, but no meaningful decline in America’s techno-economic power. If those Canadian barriers were ever lifted, there is no reason U.S. dairy producers couldn’t simply expand production. This means it is time for U.S. trade policy to prioritize advanced goods and services over commodity-based, low-value-added sectors.

President Trump has said these negotiations will be win-win. That presumably means the United States will have to make some concessions. So, when the president and his team sit down with the roughly 70 countries that have asked to negotiate, the U.S. shouldn’t go to the mattresses over domestic protection or foreign dumping of commodity products. Who cares? Sure, in an ideal world, these products would be based on total free trade. But that world doesn’t exist—and few nations are going to give up everything. Better to let them keep these protections while we focus on eliminating the policies that harm America’s advanced industries.

Take the EU, for example. The USTR’s 2025 National Trade Estimate devotes 33 pages to EU trade barriers. The Trump administration should be willing to compromise on those barriers that don’t significantly affect American techno-economic power, such as food tariffs, wine and alcohol labeling, and professional services restrictions. In contrast, it should not give in on issues that matter, holding firm on eliminating barriers to cloud services, pharmaceutical products, and government support for Airbus.

The Trump administration will have to make a choice: Demand the removal of all barriers or be strategic and focus on eliminating those critical to America’s future. If it chooses the former, there will likely be no deals and tariff walls on both sides. That’s not a good outcome unless you are a protectionist. But President Trump has the opportunity to chart a bold new course for U.S. trade policy. Doing so will require making tough political choices and putting America’s long-term interests ahead of parochial ones.

To read the full blog as it was posted by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation click here.

The post Trump Trade Negotiations: Embrace Strategic Trade, Not Autarky appeared first on WITA.

April 14, 2025

TDM Insight: China Hikes Oil & Gas Imports

China’s Economy

When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, the move was seen as an essential turboboost to a huge but developing country. Without access to global markets, there was no way for China to become the greatest exporter the world has ever seen.

Now, as the backlash to that growth turns into a bitter battle over tariffs, China no longer needs help from a multilateral trade treaty. In fact, with China now the world’s second biggest economy, we’re in unchartered economic waters. For example, in March, despite all the furor around new U.S. import tariffs and the damage it might do its top trading partner, China boosted imports of oil and gas. Natural gas imports rose a whopping 39.2% year-on-year to 9.2 million tons. Imports of crude petroleum oil rose 4.8% to 51.4 million tons.

The numbers boosted energy prices around the globe, and showed how the realities of global trade and the uniqueness of China’s economy are likely to continue to surprise analysts. “We have a vast domestic market that serves as a strong strategic backup,” said a government spokesperson. “By staying focused on our own development, we aim to provide stability amid global uncertainty.” Overall, Chinese exports increased 12.3% year-on-year to $313.9 billion, and imports fell 4.3% to $211.3 billion, widening China’s trade surplus. Analysts attributed the high export figures to business stocking up on inventory before the tariffs sink in. Once they do, “we think it could be years before Chinese exports regain current levels,” wrote Julian Evans-Pritchard, head of China economics at Capital Economics in a note.

Across the Pacific

To be sure, the worst-case scenario appears grim. The data for March, released Monday, came after one of the most tumultuous weeks in global economic history, capped by both the U.S. and China announcing tariffs over 100% on each other’s products. The threat of the world’s top two economies ceasing to trade with each other could be devastating for the global economy. The stock market’s response to suggested U.S. tariffs showed how much the world’s prosperity depends on well-oiled supply chains. Locking them up with tariffs would really hurt. The WTO said shipments between the U.S. and China could fall as much as 80%, severely damaging global growth, because of the tariffs. In March, exports to the U.S. rose 8.8% to $40.1 billion, while imports from the U.S. fell 8.9% to $12.5 billion. The persistence of the trade surplus with the U.S. is unlikely to calm protectionist fears, but the volatile nature of this particular trade war is an invitation to stay focused on the data. For all the politics and the lobbying for exemptions, what really matters is what’s going in and out of ports.

High-Tech Exception

When China joined the world trading system, the move was driven in large part by U.S. corporations eager to base their manufacturing plants in a low-wage country. Americans loved it. It was the age of the cheap sneaker. How this current trade war plays out is also likely to be influenced by the needs of U.S. business and consumers. The Trump administration, for example, has been floating an exemption for smartphones, laptops and other essential electronics. In March, China’s exports of high-tech products rose 7.8% year-on-year to $77.8 billion. Sales of mobile phones bumped up 1.4% in number to 58.3 million sets. Shipments of integrated circuits increased 8.3% to $15.8 billion.

The Great Game

The global trade economy is one of the factors re-shifting geopolitical alliances. For China, the tension with the U.S. is a chance to redo economic ties with the entire world. In March, exports to ASEAN nations rose 11.9% to $59 billion, while imports from the ASEAN bloc increased 10% to $35.1 billion. Exports to the EU rose 9.9% to $43.1 billion. Imports from the EU declined 7.4% to $21.6 billion. Exports to Vietnam increased 19.6% to $17.7 billion, while imports from Vietnam were unchanged at $8.3 billion. Whatever happens with the U.S., there will still be markets for broad categories of Chinese manufacturing. In March, for example, exports of toys rose 6.4% to $3 billion, and sales of footwear increased 10% to $3.2 billion.

And China, of course, will keep changing. In March, its purchases of coal, long core to the country’s energy mix, fell 6.4% year-on-year to 38.7 million tons.

TDM Insight 14 April 2025 - China Hikes Oil & Gas Imports - By John W. Miller

The post TDM Insight: China Hikes Oil & Gas Imports appeared first on WITA.

April 9, 2025

EU Export of Regulatory Overreach: The Case of the Digital Markets Act (DMA)

The EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) exemplifies the “Brussels Effect,” extending the EU’s regulatory influence beyond its borders and shaping global digital competition policies. While intended to curb the market power of large technology platforms and promote fair competition, its broad, rigid, and pre-emptive approach risks stifling technological development, deterring investment, and creating legal uncertainty, particularly in emerging markets still building digital infrastructure and seeking to attract foreign investment.

Large technology firms play a pivotal role in global economic development, driving innovation, infrastructure upgrading, and consumer welfare. However, increasing regulatory scrutiny, particularly under DMA-like frameworks, could inadvertently harm the very markets they help grow by imposing compliance burdens that hinder business expansion and technology diffusion. Countries with weaker institutions and regulatory capacity – such as India, Brazil, South Africa, and other emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) like Indonesia – could face greater risks of regulatory capture, corruption, and enforcement challenges if they replicate the EU’s approach without adapting it to their economic realities.

A key concern with the DMA is the departure from traditional case-by-case enforcement in competition policy, instead relying on broad, pre-emptive obligations based on ambiguous concepts such as fairness and contestability. This shift reduces legal certainty, increases the risk of inconsistent enforcement, and may inhibit dynamic competition, which is essential for innovation-driven sectors like fintech, e-commerce, ICT, and edtech. By prioritising static over dynamic competition, the DMA could impede technological progress, limiting consumer choice and long-term economic benefits.

The global adoption of DMA-like regulations risks further regulatory fragmentation and may create unintended consequences, particularly in emerging economies where regulatory frameworks, institutional quality, and market structures differ significantly from the EU. Broad prohibitions on business practices, such as self-preferencing and data-sharing, could limit opportunities for local firms to scale internationally, weaken cybersecurity protections, and reduce incentives for large technology firms to invest in these regions.

To ensure proportionate and effective competition enforcement, governments outside the EU should prioritise regulatory flexibility and case-by-case assessments over broad, static restrictions. OECD best practices on competition policy emphasise clear objectives, legal certainty, and regulatory proportionality, ensuring that competition enforcement supports, rather than stifles, innovation and investment.

Moreover, the risks of corruption and regulatory overreach in developing countries make broad ex-ante regulations especially problematic. Excessive discretionary power granted to local authorities could increase the risk of politically motivated enforcement, deter foreign investment, and undermine long-term economic growth. A more effective approach would be to strengthen institutional frameworks, enhance transparency, and adopt supply-side policies that support technology neutrality, free trade, and economic freedom.

Key Policy Recommendations

To mitigate these risks, a smarter approach to digital market regulation is needed, balancing competition enforcement with innovation incentives.

EU regulators should reassess the DMA’s rigid approach, reverting to case-by-case competition enforcement and aligning with OECD best practices to avoid legal uncertainty and overregulation.

Globally, “outside-of-EU” regulators should adapt regulations to local market conditions, avoiding one-size-fits-all EU-style competition policies that may be ill-suited to emerging economies with different enforcement capabilities.

Businesses should proactively engage in policy debates, highlighting their role in fostering innovation, economic growth, and technology diffusion while advocating for evidence-based competition policies.

Civil society should promote regulatory transparency, supporting consumer welfare-driven policies and helping governments navigate competition enforcement without stifling market innovation. Civil society organisations should assist competition authorities by providing market knowledge, empirical research on consumer harm, and expert insights to improve regulatory decision-making.

By maintaining proportionate, targeted, and innovation-friendly competition policies, competition regulators can foster dynamic competition, ensure technological progress, and create a digital economy that benefits both businesses, consumers, and overall economic development.

ECI_25_PolicyBrief_08-2025_LY03

To read the policy brief as it was published by ECIPE, click here.

To read the full policy brief PDF as it was published by ECIPE, click here.

The post EU Export of Regulatory Overreach: The Case of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) appeared first on WITA.

March 31, 2025

USTR Releases 2025 National Trade Estimate Report

WASHINGTON — Today, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) submitted the 2025 National Trade Estimate (NTE) to President Trump and Congress. The NTE is an annual report detailing foreign trade barriers faced by U.S. exporters and USTR’s efforts to reduce those barriers.

“No American President in modern history has recognized the wide-ranging and harmful foreign trade barriers American exporters face more than President Trump,” said Ambassador Greer. “Under his leadership, this administration is working diligently to address these unfair and non-reciprocal practices, helping restore fairness and put hardworking American businesses and workers first in the global market.”

The findings of the 2025 NTE underscore President Trump’s America First Trade Policy and the President’s 2025 Trade Policy Agenda.

The NTE is an annual report due to the President and Congress by March 31 of each year. USTR works closely with other government agencies and U.S. embassies and solicits comments from the public through a Federal Register Notice to prepare the NTE.

The annual report is submitted in accordance with Section 181 of the Trade Act of 1974, as added by Section 303 of the Trade and Tariff Act of 1984 and amended by Section 1304 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, Section 311 of the Uruguay Round Trade Agreements Act, and Section 1202 of the Internet Tax Freedom Act.

2025NTE

To read the 2025 National Trade Estimate as it was posted by the Office of the United States Trade Representative click here.

To read the PDF as it was published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative click here.

The post USTR Releases 2025 National Trade Estimate Report appeared first on WITA.

March 28, 2025

TDM Insight: Vietnam Boosts Imports from China.

Vietnam Pivots Back to Asia

Vietnam, one of the world’s most dynamic economies, now faces one of its most important challenges of this century as it faces protectionist headwinds and tepid consumer economies in the U.S. and Europe.

So far, its formidable export-based economy has seemed up to the task. In 2024, overall exports rose 14.3% year-to-year to $405.5 billion. The part of that from foreign direct investment increased 12.4% to $289.2 billion.

Vietnam’s coping strategy, according to an analysis by Trade Data Monitor, has been to turn more toward its prosperous ASEAN partners and China. In 2024, Vietnam increased imports from China a whopping 30.2% to $144 billion.

After the first Trump administration imposed hefty tariffs on Chinese imports in 2018, U.S. and Europe-based consumer goods firms moved or shifted parts of their manufacturing supply chains to Vietnam. It was a boon for the formerly war-torn nation, which promptly build a network of new economic zones, deep-water ports, rail lines and roads. After the 2018 duties, Vietnam’s gross domestic product grew by around 8% a year. In 2024, it expanded by 7.1%. A modern economic export miracle.

According to U.S. trade statistics, in 2024 Vietnam had the third biggest trade surplus ($123.5 billion) with the U.S., after only China ($295.4 billion), Mexico ($171.8 billion), and followed by Ireland ($86.7 billion) and Germany ($84.8 billion).

Now as the U.S. faces protectionist sentiment and economic uncertainty, Vietnam must prepare for an adjustment, and it will be essential to diversify export markets. An analysis by TDM suggests that Vietnam possesses the capacity to find new markets for its exports and diversify fruitfully.

The Asian Connection

Vietnam is tightly networked with its Asian neighbors. Seven of the country’s top ten sources of imports are Asian: China, South Korea, the U.S., Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia, and Kuwait.

In 2024, shipments from South Korea nudged up 6.5% to $55.9 billion. By comparison, purchases from the U.S. rose 9.3% to $15.1 billion. Surprisingly, Japan is still the fourth biggest supplier of goods to Vietnam, although it is slipping. In 2024, Vietnam imported $21.6 billion from Japan, down 0.2% compared to 2023. Almost all of Vietnam’s imports from Kuwait were energy-related. In 2024, Vietnam shipped in $7.3 billion, up 23.3% over 2024, from the Middle Eastern nation.

But China was not yet Vietnam’s biggest export market in 2024. That would be the U.S. Vietnam shipped $119.5 billon of goods to the U.S. in 2024, up 23.2% from 2023. China was second, buying $61.2 billion worth of goods, flat compared to 2023. Vietnam’s next biggest exports markets were South Korea, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, India, the UK, Germany, and Thailand.

Now Vietnam faces the specter of new import tariffs from the Trump administration. At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, Vietnamese prime minster Pham Minh Chinh said he was looking for “solutions” to keep his economy balanced.

Why Vietnam Will Be Able to Diversify

A review of their exports shows that the country is likely in better shape than many fear. Vietnam has trade agreements with over 25 countries. In 2024, Vietnam exports over a billion dollars’ worth of goods to 36 countries.

Vietnam’s top category of exports was computers and electrical products ($72.6 billion, up 26.6%), telephones and mobile phones ( $53.9 billion, up 2.9%), machines, equipment, tools, and instruments ($52.2 billion, up 21%).

But Vietnam is still a dominant producer of more basics manufactured goods, offering it the flexibility it will need to adjust to changing export markets. In 2024, for example, Vietnam exported $22.9 billion of footwear, up 13% from 2023. The biggest destination for Vietnam’s powerful consumer goods manufacturing capacity: the U.S. Vietnam exported $8.3 billion worth of footwear to the U.S. in 2024, up 15.7% from 2023. The next biggest markets for footwear were China, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Japan.

Vietnam also shipped significant quantities of certain kinds of furniture ($3.4 billion, up 33.5%), plastics ($2.6 billion, up 21.3%), iron and steel ($9.1 billion, up 8.7%), fruits and vegetables ($7.1 billion, up 27.6%), rubber ($3.4 billion, up 18.2%), and coffee ($5.6 billion, up 32.5%). The top markets for coffee in 2024 were Switzerland, the Netherlands and Singapore.

TDM Insight 28 March 2025 - Vietnam Boosts Imports from China - By John W. Miller

To view the insight as it was originally published, click here.

The post TDM Insight: Vietnam Boosts Imports from China. appeared first on WITA.

March 24, 2025

Trump’s Use of Emergency Powers to Impose Tariffs Is an Abuse of Power

President Trump’s tariff war waged in the name of a national emergency over fentanyl imports is an abuse of power.

In an unprecedented move, President Trump justified the imposition of tariffs on Canada. China, and Mexico under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) based on an “extraordinary threat” from illegal immigration and drug trafficking. The problem for the president, however, is that IEEPA does not explicitly grant tariff authority at all—indeed, the words “duty” or “tariff” appear nowhere in the statute—and to the extent that it grants power to restrict imports, it requires that there be a direct connection between the action taken (here, broad-based tariffs) and a properly declared national emergency (here, migrants and fentanyl crossing the southern border). But there is no direct connection between tariffs on imports of all goods—no matter how innocent or far removed from fentanyl—and the declared national emergency.

The president’s initial move to impose IEEPA-based tariffs came on Feb. 1, with 10 percent tariffs announced on all goods from China and 25 percent on all goods from Mexico and all goods other than energy products (which were subject to a 10 percent duty) from Canada. The president subsequently paused their application to imports from Canada and Mexico but increased the tariffs to 20 percent on all goods from China. On March 3, he proceeded with the 25 percent tariffs on Mexico and Canada (10 percent on energy products), only to further pause those additional tariffs on Mexico and Canada for any goods meeting the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) rules of origin. He has also threatened additional IEEPA tariffs on a wide range of products, including cars, semiconductors, and oil, as well as on imports from various other countries. China has responded with retaliatory measures and initiated dispute settlement proceedings at the World Trade Organization. Similarly, Canada responded with tariffs of 25 percent on $155 billion of American goods.

IEEPA has never been used to impose tariffs. Congress enacted IEEPA nearly 50 years ago to give the president the power to act promptly to protect the nation’s security. Although this delegation grants the president broad discretion, it was not meant to provide him with a blank check on trade policy. The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the sole power to regulate foreign commerce and impose tariffs. The president’s powers can thus come only from authority that Congress expressly delegated. This begs the question: Did Congress clearly intend to hand over its tariff authority to the president or to permit him to exercise it in such a sweeping and procedurally skimpy manner? The answer is no, especially without establishing a clear relationship to a particular national emergency.

The Major Questions Doctrine

The U.S. Supreme Court’s articulation of the major questions doctrine may have created insurmountable hurdles to the president’s desire to use IEEPA as the legal basis for sweeping tariffs. Congress frequently delegates authority to the executive branch to regulate particular aspects of society, but in a number of recent decisions, the Supreme Court has declared that for an agency to decide an issue of major national significance, its action must be supported by clear congressional authorization. In 2022, the Court in West Virginia v. EPA explicitly referred to this concept as the major questions doctrine, which builds on years of understanding that Congress does not delegate sweeping and consequential authority in a “cryptic” fashion.

The major questions doctrine entails that the Court “expect[s] Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance’,” looking at the “the history and the breadth of the authority that [the Executive Branch agency] has asserted.” In Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA, the Court expressed skepticism when agencies claim to have discovered in a long-extant statute “an unheralded power to regulate ‘a significant portion of the American economy’.”

While the question of whether the major questions doctrine applies not only to agencies but also to the president remains unsettled, the doctrine’s aim to prevent actions that lack clear statutory authorization and carry vast economic and political significance to bypass congressional authority makes its application to presidential actions both logical and necessary. The major questions doctrine is grounded in the principle of separation of powers and a practical understanding of legislative intent, which suggests that it applies not only to the delegation of authority to executive branch agencies but also to the president himself. Several appellate court decisions strongly support this interpretation, such as from the Eleventh Circuit, which reasoned that since the major questions doctrine is an interpretive canon used throughout the administrative system, it should logically extend to the executive atop the administrative state. The imposition of broad tariffs under IEEPA not only raises concerns about executive overreach but also directly challenges the separation of powers and legislative intent, risking tariff policy becoming “nothing more than the will of the President.”

There can be no doubt that using IEEPA to impose broad tariffs is a major question. It falls squarely within the Supreme Court’s notion of a “novel” use of an “unheralded” power given that no other president has used IEEPA in its nearly 50-year history to impose tariffs. The decision to impose the new tariffs on the United States’s three largest trading partners constitutes a “transformative power expansion” and carries “vast economic and political significance” as it has significant breadth, national impact, and an effect on large segments of the economy. In 2024, imports from Canada, China, and Mexico exceeded $1.3 trillion. U.S. exports to Canada and Mexico totaled $680 billion, and trade among the three USMCA parties supports over 17 million jobs. Chinese imports of goods in 2024 were $439 billion, and additional tariffs on China will impact smartphones, computers, furniture, shoes, toys, food, and more. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that these tariffs collectively are the “largest tax increase in at least a generation” and will cost the typical U.S. household more than $1,200 a year. Moreover, much of the burden of paying the tariffs will fall on lower- and middle-income households. Trade historian Douglas Irwin has noted that these IEEPA tariffs “would constitute a historic event in the annals of U.S. trade policy.”

Applying the major questions doctrine to IEEPA also shows that Congress did not “clearly authorize” the president to impose broad-based tariffs. IEEPA sets forth a wide array of actions that the president can take following the formal declaration of a national emergency, including the power to “regulate … importation or exportation” of any property in which a foreign government or foreign national has any interest. While the power to regulate importation can be read to include the imposition of tariffs, an argument can be made that this does not constitute a sufficiently explicit congressional authorization. If Congress clearly intended to delegate its tariff power, it would have used tariff terms (“tariffs,” “duties,” or “taxes”) and called for a tariff-related process to establish the factual predicate for and the appropriate level of such duties. This is not the case with IEEPA.

The words “tariff’ or “duty” appear nowhere in the statute, in contrast to other laws in which Congress has clearly delegated tariff authority (such as Section 301, specifically authorizing “duties” to respond to unjustifiable acts that burden U.S. commerce; or Section 201, permitting “duties” or “tariff-rate quotas” to respond to a surge in imports that seriously injures a U.S. industry). Indeed, the most commonly used additional tariffs (antidumping and countervailing duties) are imposed following detailed procedures focused on calculating the appropriate level of duties along with developing a formal record of the factual predicate for such duties. As Peter Harrell observes., the president has numerous tariff avenues available to him but has chosen the “minimal procedural hurdle” IEEPA instead, even though the legislative history of IEEPA does not include an explicit authorization by Congress to impose tariffs.

The Dubious Link Between Broad-Based Tariffs and a Crisis of Illegal Drugs and Immigrants

Even if the major questions doctrine is held not to apply to delegations to the president, or, as Addar Levi suggests, the courts are reluctant to apply the doctrine in the context of national security decisions, President Trump exceeded any potential IEEPA delegated powers by adopting across-the-board tariffs that bear no reasonable connection to his declared emergency.

The only court case called upon to examine the connection between emergency powers and tariff authority, United States v. Yoshida International, upheld President Nixon’s temporary surcharge under the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA), IEEPA’s predecessor. However, in addition to the case predating the major questions doctrine, there is a stark difference between the limited nature of Nixon’s tariffs and Trump’s broad-based tariffs. Nixon’s tariffs were narrowly tailored, temporary, imposed at levels that did not exceed the rates Congress had approved, and calculated to meet a particular national emergency that was susceptible to being addressed through tariffs—the balance-of-payments crisis arising out of the U.S. withdrawal from reliance on the gold standard to determine exchange rates. Indeed, while the lower court in Yoshida found that TWEA did not delegate tariff authority to the president, the appeals court ultimately upheld Nixon’s tariffs, finding that imposing a temporary surcharge at rates below congressionally approved ceilings in order to discourage imports bore an “eminently reasonable relationship” to the declared balance-of-payments emergency. Here, it appears that President Trump’s executive orders imposing across-the-board tariffs—10 percent on Canadian energy products and potash, 25 percent on other goods from Canada and those from Mexico (even if subject to a 30-day pause or an exemption for USMCA qualifying goods) and 20 percent on all goods from China—include neither the temporal nor other specific limitations that Nixon’s tariffs did. There is no time frame for removing the duties, the duties exceed the rates Congress approved for Canada and Mexico in the USMCA, and tariffs on all products do not bear “an eminently reasonable relationship” to fentanyl. They thus appear to fall precisely into the box that the Yoshida court suggested would not be permissible: tariffs imposed at whatever rates the president deems desirable that may render U.S. trade agreement programs (such as the USMCA) nugatory.

Not only does President Trump’s measure imply a far more significant change to U.S. tariff and trade policy than Nixon’s did, but it was also adopted under a more limited authority than TWEA. Two years after the Yoshida decision, Congress transformed TWEA into IEEPA with the stated goal of both narrowing the scope of the delegation of power and adding procedural limitations, including those in the National Emergencies Act (NEA), making it clear the president’s exercise of this authority is not absolute.

Among the changes was limiting what can constitute a national emergency to “unusual and extraordinary threats” from outside the U.S. While these terms are not defined in the statute, legislative history indicates that “emergencies are by their nature rare and brief, and are not to be equated with normal, ongoing problems.” Given how long the United States has been fighting the drug war, the fentanyl trade, and the influx of illegal migrants, it is hard to see these emergencies as “rare” or “brief.” Moreover, the national emergency declaration focused on illegal migrants and illicit narcotics at a time when illegal southern border crossings and both fentanyl deaths and overall preventable drug deaths have been down since 2023.

The need to transform TWEA into IEEPA arose largely due to concerns that TWEA had essentially become “an unlimited grant of authority” and actions were adopted that did not bear any relationship to a specifically declared emergency. To address these concerns, a procedural restriction was added—in §1703(b)—that required the president to immediately report to Congress explaining why the particular actions under IEEPA are “necessary” to specifically “deal with” the declared emergency. This provision indicates that the measures taken (here, tariffs) must be directly linked to the unusual and extraordinary threat declared (here, a public health crisis), while the cross-references in §§1701 and 1702(a)(1) reinforce the limitation that the president may exercise authority only to the extent necessary to deal with the declared threat.

No such relationship between the measure and the declared objective exists in the present case. The president has contended that illegal trafficking of fentanyl from Canada, China, and Mexico is the cause of “a public health crisis” in the U.S., justifying broad tariffs under IEEPA. However, IEEPA requires that the president demonstrate why the imposition of tariffs on all goods is necessary to resolve the crisis, which is rooted in the excessive promotion of opioid painkillers in the U.S., the lack of prevention and addiction-treatment policies, and a number of other factors not linked to imports from Canada, China, or Mexico. Nor is it clear that tariffs on unrelated goods can address the fact that the vast majority of those caught during border crossings with fentanyl are U.S. citizens. IEEPA’s authority to regulate is not meant for domestic circumstances or for non-economic aspects of international relations.

Nowhere in the executive orders does the president provide the required explanation of why tariffs on all goods—including those that have nothing to do with drugs—are the necessary or appropriate tool to deal with a public health crisis in the U.S. To the contrary, to the extent that the tariffs cause a major economic downturn in Mexico, the impact of the tariffs may be increased illegal migration and smuggling of illicit goods. Moreover, the tariffs will also be applied to legal, needed drugs and essential hospital supplies, thereby causing price increases that will negatively impact public health in the U.S. Rather than making the required link between tariffs and the declared public health crisis, the White House’s fact sheet accompanying the executive orders states that the IEEPA tariffs were being imposed as a source of leverage.

In addition, IEEPA requires that the president declare a national emergency with respect to such a threat before adopting any actions under 50 U.S.C. § 1702(a)(1)(B). The only free-standing National Emergencies Act declaration was issued on Jan. 20, proclaiming a national emergency on the southern border. The Feb. 1 executive orders simply extended this emergency to apply to both Canada and China due to their failure to counter drug and human trafficking (Canada) and chemical precursor suppliers and money laundering (China). There was no new, separately declared national emergency. It is unclear whether embedding a national emergency declaration in an executive order imposing tariffs satisfies the requirements of the NEA that emergency powers can be exercised only when the president “specifically declares a national emergency” via a proclamation that is immediately transmitted to Congress and published in the Federal Register, nor the requirement in IEEPA that the president, “in every possible instance,” consult with Congress before taking action.

To permit IEEPA—a statute that does not mention tariffs and is designed to deal with unusual and extraordinary threats to America’s national security—to be used to impose tariffs at whatever level the president decides in order to create leverage to address any national emergency, no matter how disconnected from trade or imported goods, is to suggest that there are virtually no limits on the president’s power to impose tariffs. This can subvert the rule of law, undermine the Constitution and its separation of powers, risk exacerbating tensions with our trading partners, and invite destructive retaliation.

To read this article as it was published on the Lawfare website, please click here.

The post Trump’s Use of Emergency Powers to Impose Tariffs Is an Abuse of Power appeared first on WITA.

March 21, 2025

Here’s How Countries Are Retaliating Against Trump’s Tariffs

Trade retaliation looms from Canada, China, Mexico, and the European Union in response to U.S. tariffs. Four timelines lay out their responses, and the experience of American soybean farmers in 2018 shows how damaging this could be.

In response to the Donald Trump administration’s second-term tariffs, Canada, China, Mexico, and the European Union (EU)—the United States’ largest trade partners—have announced or threatened retaliatory tariffs.

How do retaliatory tariffs work?

A tariff is a tax on foreign-made goods, which makes them more expensive to import. To get a better idea of how retaliatory tariffs could affect the United States, let’s look at what happened to American soybean farmers during Trump’s first term. Soybeans are the United States’ largest agricultural export to China.

In 2017, U.S. soybean exports to China totaled $12 billion, near an all-time high. Then in 2018, the United States placed tariffs on $34 billion worth of Chinese non-agricultural goods, and China retaliated with tariffs on U.S. soybeans and other products. Soybean exports to China plummeted, with U.S. farmers suffering substantial losses.

U.S. farmers’ losses were Brazilian farmers’ gains. Brazil, the world’s leading soybean producer, increased soybean exports to China and has remained its top supplier.

U.S. soybean exports to China recovered after the two countries signed a trade deal in 2020 but have declined somewhat in recent years as China has sought to become less reliant on imported soy.

From 2018 to 2019, U.S. farmers suffered $26 billion in losses due to China’s retaliatory tariffs. In response, the Trump administration provided $28 billion in bailouts to farmers across the two years.

How are countries retaliating against Trump’s 2025 tariffs?

The second Trump administration has largely taken a blanket approach with tariffs, initially targeting all goods from Canada, China, and Mexico, as well as all aluminum and steel imports, and planning reciprocal tariffs on all trade partners. U.S. trade partners, meanwhile, have taken a more targeted approach aimed at specific U.S. products.

Canada

On March 4, Canada imposed tariffs on U.S. imports including agricultural goods, appliances, motorcycles, apparel, certain paper products, and footwear. In response to Trump waiving tariffs for Canadian imports covered under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), Canada delayed a second round of tariffs on goods ranging from agricultural and aerospace products to electric vehicles until April 2.

On March 10, the Canadian province of Ontario imposed a surcharge on electricity exported to Michigan, Minnesota, and New York, but later suspended this. However, in response to U.S. tariffs on aluminum and steel imports, Canada on March 12 announced additional tariffs on those two U.S. metals, as well as other goods.

China

China has also imposed retaliatory tariffs on the United States. The first round went into effect on February 10, affecting coal, liquefied natural gas, crude oil, agricultural machinery, large vehicles, and pickup trucks. After Trump increased tariffs on China in early March, Beijing announced a second round of tariffs starting March 10; this included 10 percent tariffs on chicken, wheat, corn, and cotton products, as well as 15 percent tariffs on a range of agricultural products, including soybeans.

In addition, China has enacted export controls on critical minerals, launched an antitrust investigation into Google, and added more than a dozen U.S. companies to their Export Control and Unreliable Entity lists. These measures will not only have the potential to disrupt U.S. supply chains but also harm the global economic competitiveness of U.S. businesses.

European Union

Likewise, the EU has stated that “unjustified” U.S. tariffs on European aluminum and steel “will not go unanswered,” and announced retaliatory tariffs on March 11. Specifically, the bloc plans to reimpose 2018 and 2020 retaliatory tariffs against the United States but also put into place new tariffs following discussions among EU member states in March.

Mexico

Mexico, meanwhile, planned on announcing retaliatory tariffs on March 9, but did not follow through after Trump exempted Mexican goods covered by the USMCA. On March 9, President Claudia Sheinbaum affirmed Mexico’s commitment to curb fentanyl trafficking and said she expects the United States to continue preventing arms trafficking into Mexican territory. If Mexico does choose to implement retaliatory tariffs—particularly after the exemption on USMCA goods expires on April 2—it is likely that they will target U.S. products such as vegetables, fruits, beer, and spirits.

Many of these retaliatory tariffs are targeting industries in parts of the country that supported Trump in the 2024 election, a move that some experts say is designed to maximize leverage. Examples include Canadian tariffs on fruit from Florida and motorcycles and coffee from Pennsylvania, and Chinese tariffs that will affect farming and manufacturing communities in the Midwest and Rust Belt. Ultimately, however, the economic cost will be felt throughout the country.

How could these retaliatory tariffs hurt the United States?

U.S. exports, specifically from the agriculture and livestock sectors, will decline in the short term as trade partners reduce their imports. U.S. producers will suffer from decreased revenue—as U.S. soybean farmers did during the 2018–19 trade war—while other countries will seek to fill the gap left by the United States. Soybean farmers have still not fully regained their market share of soybean exports to China.

Retaliatory tariffs could also result in an escalation of existing U.S. tariffs, hurting consumers as businesses pass on the costs of tariffs in the form of higher prices. The average U.S. household is already expected to face a cost increase of more than $1,200 per year as a result of existing U.S. tariffs. The imposition of retaliatory tariffs also raises other concerns, including the potential effects on the U.S. stock market and allies’ declining trust in U.S. economic leadership.

To read the article as it was published on the Council on Foreign Relations website, please click here.

The post Here’s How Countries Are Retaliating Against Trump’s Tariffs appeared first on WITA.

March 14, 2025

Global Trade Update (March 2025)

The March 2025 edition examines tariffs and their impact on global trade. As an important trade policy tool, tariffs serve as a mechanism to protect domestic industries and generate government revenue.

However, high import duties can increase costs for businesses and consumers, potentially stifling economic growth and competitiveness. Policymakers must strike a balance between leveraging tariffs for economic development and integrating into the global economy through trade liberalization.

The report also presents new trade data and projections across regions, industries and sectors, covering 2024 and early 2025. While global trade reached a record $33 trillion last year, the outlook for 2025 remains uncertain.

Key takeaways on tariffs

Today, about two-thirds of international trade occurs without tariffs, either because countries have chosen to reduce duties under most-favoured-nation (MFN) treatment or through other trade agreements.

However, tariff levels applied to the remainder of international trade are often very high, with significant differences across sectors. Agriculture remains highly protected, manufacturing still encounters trade barriers in key industries, while raw materials generally benefit from low tariffs.

Developing countries face higher duties that limit market access. Agricultural exports from these nations face import duties averaging almost 20% under (MFN) treatment. Meanwhile, textiles and apparel remain subject to some of the highest tariff rates (import duties average close to 6%), limiting developing countries’ competitiveness in these industries.

South-South trade (trade between developing countries) still faces high tariffs. For example, trade between Latin America and South Asia faces an average tariff of about 15%.

Tariff escalation discourages developing economies from exporting value-added goods, hindering industrialization. This refers to the practice of applying higher tariffs on finished goods than on raw materials or intermediate inputs. Designed to protect domestic industries, this tariff structure also discourages manufacturing in countries that produce raw materials, creating a disincentive to move up the value chain.

Key trade facts and figures

Global trade hit a record $33 trillion in 2024, growing by 3.7% ($1.2 trillion). Most regions saw positive growth, except for Europe and Central Asia.

Services led the expansion in 2024, growing 9% annually and adding $700 billion (nearly 60% of the total growth). Trade in goods grew at a slower 2%, contributing $500 billion. However, growth in both sectors slowed in the second half of 2024, with services growing just 1% and goods less than 0.5% in the fourth quarter.

Developing economies’ trade grew faster. Their imports and exports rose 4% for the year and 2% in the fourth quarter, driven mainly by East and South Asia. Meanwhile, developed economies saw their trade stagnate for the year and drop by 2% in the fourth quarter.

Merchandise trade imbalances widened. The United States trade deficit with China reached -$355 billion, widening by $14 billion in the fourth quarter, while the US deficit with the European Union increased by $12 billion to -$241 billion. Meanwhile, China’s trade surplus reached its highest level since 2022. And the EU reversed previous deficits, posting a trade surplus for the year.

Trade remained stable in early 2025, but uncertainty looms. Mounting geoeconomic tensions, protectionist policies and trade disputes signal likely disruptions ahead. Recent shipping trends also suggest a slowdown, with falling freight indices indicating weaker industrial activity, particularly in supply chain-dependent sectors.

ditcinf2025d1

To read the Policy Insight as it was published by the United Nations Trade and Development click here.

To read the PDF as it was published by the United Nations Trade and Development click here.

The post Global Trade Update (March 2025) appeared first on WITA.

March 12, 2025

The IMF, Country In Crisis & Sovereign Debt

(The IMF exists to achieve sustainable growth and prosperity is governed by and accountable to 190 countries that make up its near-global membership. The IMF was founded by 44 member countries that sought to build a framework for economic cooperation. The IMF was established in 1944 in the aftermath of the Great Depression of the 1930s.)

Countries, similar to companies and individuals, should honor their debts.

However, when a sovereign is faced with the dilemma of default it is a distressing one for both the lenders and borrowers, where paying back the debt re quires scenarios where resolutions can be achieved with repayment goals. The current dependence on the international community to bail out the private lenders deters countries from resolving unsustainable debts efficiently and appropriately amongst each other of their own initiative, especially since there is a lack of incentives for lenders and borrowers to do so. The broad ramifications may be an increase in sovereign defaults and international legal issues. The resolution is to alter macroeconomic policy in our treatment of sovereign default. In doing so, one suggested proposal is restructuring sovereign debt by creating formal procedures, an International Monetary Fund (IMF) Country Bankruptcy Court, where lenders and borrowers through a collaborative effort will restructure the debt and the IMF will preside as the governing body through this process (restructuring of debt is not too different than debt restructuring done in the private sectors, just depends on the borrower terms and the lender’s appetite for risk). This forthright approach was suggested by Anne O. Krueger, the First Deputy Managing Director of the IMF in November 2001. She believed that this “formal mechanism” would have served as a “catalyst”, and provide lenders and borrowers a number of protections during the debt restructuring process. In the following based on her proposal, I examine what leads a country to crisis or default.

Sources of Country Crisis & Economic Analysis:

It is arguable that essentially a country in crisis is a product of budget deficits, which triggers a downward-spiral in the economy through other contributing factors, such as the fixed exchange rate leading to an obscene decline in fixed exchange reserves. Also, there exists an inevitable conflict between expanding monetary policy and the fixed exchange rates. This was true in the case of Argentina. When President Carlos Menem took office in Argentina in 1989, the country had piled up huge external debts, inflation had reached 200% per month, and output was plummeting. To combat the economic crisis, the government embarked on a path of trade liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. In 1991, it implemented radical monetary reforms, which pegged the peso to the US dollar and limited the growth in the monetary base by law to the growth in reserves. Inflation fell sharply in subsequent years. In 1995, the Mexican peso crisis produced capital flight, the loss of banking system deposits, and a severe, but short-lived, recession; a series of reforms to bolster the domestic banking system followed. Real GDP growth recovered strongly, reaching 8% in 1997. Then in 1998, international financial turmoil caused by Russia’s problems and increasing investor anxiety over Brazil produced the highest domestic interest rates in more than three years, halving the growth rate of the economy. Conditions got worse in 1999 with GDP falling by 3%. President Fernando De La Rua, who was in office in December 1999, sponsored tax increases and spending cuts to reduce the deficit, which had ballooned to 2.5% of GDP in 1999. Growth in 2000 was a disappointing 0.8% (Argentina website), as both domestic and foreign investors remained skeptical of the government’s ability to pay debts and maintain its fixed exchange rate with the US dollar. Argentina, soon enough was in default with.

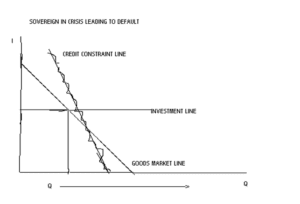

In addition to such tensions a sovereign may face, the eminent problem which is highlighted in parts of Argentina’s story and which stems from the theory that a potentially healthy economy can experience a “self-fulfilling” financial crisis (Krugman 1999) is attributed to the role of balance sheet problems in limiting investment by the private sector, and the impact of the real exchange rate on those balance sheets which produce such powerfully negative effects on a potentially healthy economy that they lead to, for our purposes, such an enormous “credit constraint” that the sovereign falls in a state of crisis. To illustrate my point, three conditions exit in a “potentially healthy economy” subsequent to each other as the sovereign defaults.

The conditions are as follows.

1. The first is that a “Goods Market” exists and contributes to the crisis,

2. The second is the “Equilibrium in the Asset Market”. The assumption is that capital lasts only one period; this period’s capital is equal to last period’s investment. So, the capital produced through investment and entrepreneurs is equal to the interest rate for this period times the exchange rate on goods for this period, and

3. The third condition for our purposes, is the “Credit Constraint”. With this condition, the assumption is that investment cannot be negative and lenders cannot lend more than half their wealth (I < λW), which is a result of the profits (P) minus the domestic debt (DD), minus the foreign debt (FD); (Q) the exchange rate is applied to the foreign debt for conversion.

If time permitted, applying real numbers to these conditions would indicate that the interaction of these three conditions will result in a depreciating exchange rate, the sovereign’s wealth will be significantly less since the declining exchange rate has already triggered a downward-spiral, and debt would be on the rise. Figure 1 illustrates that as the exchange rate (Q) shifts to the right and continues to do so, the “Credit Constraint Line” at conflict with the “Goods Market Line” results in the sovereign’s debt rising and leading towards default.

The IMF Country Bankruptcy Court Proposal & Economic Analysis:

As illustrated in Figure 1, since lenders will no longer want to lend the sovereign funds, and the sovereign will have no option, but to default as a result of its downward-spiral economy. For such sovereigns the question that comes up is: did Ms. Krueger’s IMF Country Bankruptcy Court proposal rescue them? In order to answer this, we will review the proposal more closely. Ms. Krueger sets up her approach to restructuring sovereign debt on two pillars: firstly, on “reforming the architecture” of the IMF and secondly, on “involving the private sector in crisis resolution”. Regarding the first pillar, she believes since the IMF is focusing on better national policies and reforms, such as “encouraging better communication between IMF and its members, creating the Contingent Credit Line facility offering countries with sound policies a public “seal of approval”, and now with more urgency, assisting to resolve balance sheet problems in the financial and corporate sectors”, today, the IMF is in a better position to have additional powers. These revisions to prevention and crisis management measures were highlighted by Ms. Krueger to justify that if such centralization of power were to occur, the IMF, despite the satirical political machine that it is with a multitude of politically aligned motivations it has had in emerging countries, has the foundation necessary in resolving sovereign debt issues.

To date, there is no IMF Country Bankruptcy Country Court and Ms. Krueger’s proposal, a novel idea and resolution to the dilemma discussed has not happened via the IMF yet. There are however, technical assistance and remedies to resolve sovereign debt default of countries and managing the domestic turmoil caused, offered by the IMF. These resolutions are a solution and aid in restructuring sovereign debt issues, but most of all the economy is in constraint like the “credit constraint” illustrated earlier. My strong inclination is that sovereign default is one of the worst predicaments a country can face: it impacts rising food costs, unemployment, inflation, political unrest likely, reduction in essential healthcare services, and extreme poverty overall. The remedy seems to be a restructuring of debt at favorable terms and a plan in place over time to achieve this goal. What good is the IMF if there is no collaboration or resolution scenarios? The IMF Bankruptcy Court was not “just a novel idea,” but a strong blueprint for resolving the issues of any country in sovereign debt default, and if does ever come to fruition it would lead to aiding many countries with default scenarios and effective resolutions that can also achieve collaborative private sector and public sector support.

Sonal Patney is a corporate and investment banker and author having originated, marketed, structured, executed, and closed over 100 debt and equity financings that ranged from $5M to $4B. As of October 2022, Sonal became an author with the international publishing of her book on sustainable finance debt by Europe Books – “How Should We Think About Debt Capital Markets Today? ESG’s Effect on DCM”. As a graduate of Columbia University, and New York University, she holds an MPA with a concentration in International Economic Policy, and a BA in Political Science, respectively. Her academic research has focused on emerging market countries, trade and hedge funds. Additionally, she has been a pro bono SCORE LI mentor for small business’ and the recipient of a mentoring award from SCORE; a member of varying nonprofit associations and a former Board member of some. She is also a “Contributor” for The Financial Executives Networking Group Journal online on capital markets topics.

The post The IMF, Country In Crisis & Sovereign Debt appeared first on WITA.

On The Relevance of Dollarization: Advantages & Disadvantages of the US Dollar

Implementing a monetary policy of dollarization has a multitude of implications. Before implementing such a monetary policy, it is imperative to examine what the implications of dollarization are, what the costs and benefits may be, and whether adopting dollarization at any time for our country would serve to be an effective monetary policy. The theoretical answer to this, and to use dollarization is that “it really depends on which side one decides to be on”. For example, if you are with the United States, through dollarization is one of the obvious benefits is seigniorage, revenue from issuing currency. If you are with the country adopting dollarization, one of the obvious benefits is the reduction of exchange rate risk, since the domestic currency is eliminated. The question of to dollarize or not to dollarize is certainly difficult to satisfy, particularly since we are lacking in historical precedence, as of July 2021 with Panama as the sole sizable comparative point (Berg & Borenztein, 4). Nevertheless, I will first present the overall advantages and disadvantages of dollarization, then examine whether adoption of this monetary policy is a wise course of action for a country in the western hemisphere and at what juncture.

Before I divulge any further into this, it is important to provide a definition of dollarization. In the most basic sense, dollarization occurs when the residents of a foreign country continuously use foreign currency concurrently (in our case the US$) or instead of the domestic currency (if we are looking at any other country). Dollarization can occur unofficially, individuals holding foreign currency bank deposits or paper money, or officially, the government adopting foreign currency as the dominant legal currency. Panama and East Timor are two examples of official dollarization, while others, such as Ecuador, were also considering official dollarization in 2021; in the case of East Timora and Panama economic stability and credibility avoiding political unrest is the primary reason why dollarization there works well (for East Timor, Indonesia, this has served as rescue tactic from the Asian Financial Crisis which occurred in late 1990s in East and Southeast Asia). I do agree the lack of controls with regards to their money supply and devoid of any local currency advantages are a concern, but for these countries dollarization has served to be beneficial. Now, I will look at dollarization as an official policy for the US.

There are four broad sets of advantages for dollarizing: eliminating the risk of increasing exchange rate adjustments, lower transaction costs, lower inflation, and increasing economic stability and transparency. The primary advantage for countries to dollarize is that it eliminates the risk of increasing exchange rate adjustments. This benefit triggered by dollarization can produce a “domino-effect” for the dollarized country. Countries which have very high exchange rates are often led to a state of currency crisis, dollarization helps avoid this scenario. However, an immediate result of this advantage is that there would be lower interest rates and less country risk premia (Berg & Borensztein, 5). This additional benefit of dollarization would lead to stable international capital inflows. Such capital movement stability will eventually lead to increasing investor confidence, lower international borrowing, and increasing foreign investments in the dollarized country.

The second advantage is lower transaction costs, the cost of exchanging one currency for another, since the dollarized country does not have to pay for currency exchange with other countries in the unified currency zone. This also increases trade and investment with countries within the unified currency zone due to the incentive of lower transaction costs. Additionally, this incentive may compel banks to hold lower reserves, thereby reducing their cost of doing business. The implications of a country’s domestic currency are that banks would have to separate their domestic currency and foreign currency portfolio. However, with official dollarization, the portfolio in essence would be part of one large pot.

The third advantage is lower inflation. By using a foreign currency. a dollarized country obtains a rate of inflation close to that of the issuing country. Dollarization for a country, such as Panama has served to be a significant advantage, with lower inflation today. The risk of high inflation has always been of extreme concern for countries, since its consequences are so grave. A historical example is the “drowning Argentina” when the peso sunk from one-to-the-dollar to three-to-the-dollar. From deflation, Argentina has moved to inflation, with a rise of 4% in the consumer price index for March. (Financial Times, 5/2002). For Argentina the big question is whether it will be able to rise above water before it reaches hyperinflation. In view of Argentina’s predicament in 2021, implementing dollarization to reduce inflation appears to be the imminent savior. Using not only the dollar, but also the Euro or the Yen would reduce inflation substantially for developing countries in the western hemisphere.

The fourth advantage is greater economic stability and transparency. With regards to greater economic stability, since there is no domestic currency that needs to be factored in, the threat of magnified depreciation and devaluation are no longer there. Therefore, dollarization eliminates the balance of payments crisis, effectively a currency crisis when the value of the currency declines, and there is less support for exchange controls, restrictions on buying foreign currency. Also, another element of economic stability would be a closer financial integration of the foreign country to the issuing country. Such integration would decrease the financial vulnerabilities a developing country may have, decreasing country risk and this is because the “integration” itself eliminates this “risk”. With regards to transparency, since there is a greater economic openness on the part of the government, by eliminating its power to create inflation, and dollarization promotes an inevitable budgetary discipline. This means that deficits must be financed by transparent methods, and these are higher taxes or increased debt, rather than through printing money.

In outlining the advantages of dollarization, it appears to be an attractive alternative for some countries, but this would not be a fair assessment, unless the disadvantages are highlighted as well. There are four main disadvantages of dollarization: the cost of lost seigniorage, default risk, the irreversible monetary policy dilemma, and elimination of the lender-of-last-resort function. The first disadvantage involves seigniorage (profit made by a government for minting currency). The magnitude of the “cost of lost seigniorage” is embedded in its two components: stock cost and flow cost. The “stock cost” is the cost of obtaining enough foreign reserves needed to replace domestic currency in circulation. An IMF study estimated that the stock cost of official dollarization for an average country would be 8% of gross national product (GNP was $23 trillion); a notably large amount. To compare an extreme example, in 2001, for the United States the stock cost was over $700 billion. In terms of gross domestic product, the stock cost would be about 4% instead of 8%, which is still a significant number. The other component of seigniorage, “the flow cost” is the continuous amount of earnings lost every year. This cost generates future revenue for a country by reprinting of money every year to meet the increase in currency demand. Besides the obvious attraction of seigniorage being a revenue source, it can be used to purchase assets or used towards resolving a deficit. (Berg & Borensztien, 15) Seigniorage can also be used to finance a portion of the government’s expenditures potentially without having to raise taxes.

The second disadvantage is the risk of default by the dollarized country, which may occur as a consequence of devaluation risk increasing sovereign risk. The sovereign risk may occur as a result of eliminating currency risk, which would reduce the risk premium on dollar-denominated debt. Such an effect potentially could be prevented by a devaluation of the exchange rate, which may improve the domestic economy, thereby decrease default risk. This disadvantage almost negates the rationale for dollarizing, since the desired effect of dollarization is to improve a country’s financial position and save it from a country crisis scenario.

The third disadvantage is that dollarization is irreversible. The lack of a flexible monetary policy may bear a high cost to the dollarized country in a situation where the issuing country is tapering its monetary policy during a boom, while the dollarized country needs a more flexible monetary policy because it is in a recession. A country’s tolerance for economic shocks decreases due to this. Another aspect of this disadvantage is that with dollarization being irreversible, a country losses’ its’ symbol of nationalism forever. Although, this may not carry as much weight comparatively, it is a key factor in being a cost to the country, particularly, in view of the gold standard period (1870s, when the currency was tied to a fixed amount of gold).

The fourth disadvantage is that dollarization eliminates the lender-of-last-resorts function, which would mean that the dollarized country would lose the domestic central bank as a lender of last resort, which is a grave predicament for any country and if dollarized then it should be proven that it is infact an advantages policy to implement for that particular country. The issue is that the dollarized country may not be able to obtain sufficient funds to save individual banks if need be. This would create further banking problems in the dollarized country. Since the banking systems in many developing countries are weak and vulnerable to market problems, they are not capable of handling the system-wide banking problems. Such a disadvantage would lead to a handicapped dollarized country, an even worse predicament.

Dollarization is not the optimal route for every country, but it is also not to be eliminated as an option and my recommendation is that the macroeconomic and microeconomic factors of any country should be carefully evaluated if dollarization is to be considered there, and in view of optimum currency areas (where benefits of using a common currency outweigh the costs). Optimum currency areas will allow us to judge whether dollarization is desired. This theory states that the economy is part of an optimum currency area when a high degree of economic integration makes a fixed exchange rate more beneficial than a floating rate. However, it is difficult to define this area accurately. Measuring the implications of “not dollarizing” economically will indicate when we should implement dollarization and factor in an exchange rate. For a mid-sized country in the Western Hemisphere, the characteristics, such as high exchange rates, susceptibility to higher inflation and overall weak economic conditions will lead to increasing default risk, which will lead to a country crisis. (Paul Krugman, 1998).

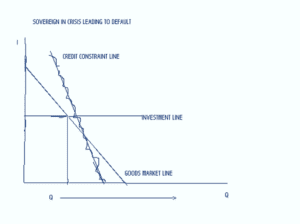

To illustrate this country crisis three conditions exit for our country:

1.The first is that a “Goods Market” exists and contributes to the crisis, expressed as Y = C + G + CA + I (Q). In this economy, (Y), the output or goods a economy produces is a result of a certain amount consumed (C), consumption of goods by government (G), goods exported and imported in (CA), and whatever amount is left over invested (I) to produce more goods for the economy. Since all the goods invested (I) are not domestic, (Q) is the price of foreign goods relative to a domestic good. As (Q) increases, the foreign goods are more expensive.

2.The second is the “Equilibrium in Asset Market”, expressed as MPK = (K, L) = (1 + R*) Qt/Qt , where the marginal product of capital (MPK) is created through investment (K) and entrepreneurs or lenders (L). The assumption is that capital lasts only one period; this period’s capital is equal to last period’s investment. So, the capital produced through investment and entrepreneurs is equal to the interest rate for this period multiplied by the exchange rate on goods for this period.

3.The third condition, for our purposes, is the “Credit Constraint”, expressed as I <λW = λ (P) – (DD) – Q (FD). With this condition, the assumption is that investment cannot be negative and lenders cannot lend more than half their wealth (I < λW), which is a result of the profits (P) minus the domestic debt (DD), minus the foreign debt (FD); (Q) the exchange rate is applied to the foreign debt for conversion.

If time permitted, applying real numbers to these conditions would indicate that the interaction of these three conditions will result in a depreciating exchange rate, our sovereign’s wealth will be significantly less since the declining exchange rate has already triggered a downward-spiral, and debt would be on the rise. Figure 1 illustrates that as the exchange rate (Q) shifts to the right and continues to do so, the “Credit Constraint Line” at conflict with the “Goods Market Line” results in our sovereign’s debt rising and leading towards default.

Figure 1. Country Crisis Model

Therefore, with such a distressing illustration of a country leading to the predicament of a country in crisis, with country characteristics such that default is an inevitable consequence, Dollarization is the best alternative, and it is arguable that just before this juncture is the optimal point at which dollarization should be implemented, thereby proving my case for Dollarization here.

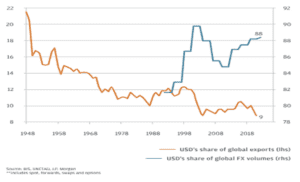

Today, the ideas of de-dollarization have become more widespread and it seems that the geopolitical events in many countries are the major factor for this. Once the dominant reserve currency, it is becoming more expensive due to high interest rates being another factor. “The US dollar’s shares in international foreign reserves, global trade invoicing, international debt securities, and cross-border loans are many times greater than the United States’ shares of global gross domestic product (GDP) and international trade (The International Banker 2024). The question at hand is how does de-dollarization help any situation from a macro-perspective when it diminishes the US stance and position in the foreign currency world and in the past this supremacy has always aided countries and represented a nationalism that advances trade policies generally? Exceptions to this are always there; dollarization today for Argentina is not conducive and rather would be an expensive route for the economy there; among the list of the countries that have de-dollarized today are Russia, India, China, Kenya, and Malaysia, while promoting local currencies for them is an enormous motivation, and the many advantages they aim to gain.

The following illustration (from JP Morgan as of April 2023) on “The Dollar’s Contrasting Fortunes” highlights the US’s share of global FX volumes increasing tremendously, and US’s share of global exports (%) decreasing equally, which implies that the value of the US $ currency decreasing and its demand, at least, as of late 2018.

So, where exactly are we with dollarization today? The best answer is to strategically evaluate on a case by case basis for any given country.

Sonal Patney is a corporate and investment banker and author having originated, marketed, structured, executed, and closed over 100 debt and equity financings that ranged from $5M to $4B. As of October 2022, Sonal became an author with the international publishing of her book on sustainable finance debt by Europe Books – “How Should We Think About Debt Capital Markets Today? ESG’s Effect on DCM”. As a graduate of Columbia University, and New York University, she holds an MPA with a concentration in International Economic Policy, and a BA in Political Science, respectively. Her academic research has focused on emerging market countries, trade and hedge funds. Additionally, she has been a pro bono SCORE LI mentor for small business’ and the recipient of a mentoring award from SCORE; a member of varying nonprofit associations and a former Board member of some. She is also a “Contributor” for The Financial Executives Networking Group Journal online on capital markets topics.

The post On The Relevance of Dollarization: Advantages & Disadvantages of the US Dollar appeared first on WITA.

William Krist's Blog