Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 133

September 30, 2013

Dual Review: Engines of the Broken World by Jason Vanhee

Though we don't have a formal horror series planned for October, Kimberly and I will be featuring a number of reviews and other fun features highlighting horror this month. We're going to kick it all off with a dual review of a horror novel that generated a ton of discussion between the two of us because it does precisely what a good horror novel should do: it leaves you with a lot more questions than answers, and those questions beg to be talked about. The two of us enjoyed Engines of the Broken World so much that we invited the author to participate in an interview. So whet your appetite on the review, and then we'll bring you an interview with Jason Vanhee tomorrow.

Kimberly Says . . .

Merciful and Gospel Truth's mother has just died. They live on a farm in the country, and it's been cold - and getting colder - for a long time. This means they can't bury their mother in the hard ground. Instead, they put her beneath the kitchen table, which they know is wrong.

The Minister, the talking cat who lives with them, guiding their actions on the path of righteousness, tells them this is wrong. They must bury their mother, even if it means venturing out into the encroaching fog, the fog which eats away at their neighbors' bodies, leaving nothingness behind.

But they don't listen to the Minister. They leave their mother's body unburied, and Merciful realizes what a mistake they've made when she hears her dead mother's voice speaking to her. Her mother - or whatever is inhabiting her mother's body - has something to do with the fog closing in on the farmhouse, closing out the rest of the world. The Minister is also involved somehow, and one of the greatest joys of watching this story unfold are the ways Vanhee leads the reader down so many different paths. What is the true nature of the Minister, of the fog, of Merciful's mother? You'll change your mind several times over the course of the story, and you may still feel like you don't have all the answers at the end.

I like it when authors take risks with their content. There's quite a lot of religion in this book, but it doesn't come close to resembling what most would consider "Christian fiction." Because Vanhee plays with Christianity in the way he does, twisting it into something one might call horrifying, I expect a great many readers would find his book offensive.

I love that. I don't love it just because people are offended; I love that these kinds of stories are not off-limits despite that. I've written about this a little bit when I discussed Misfit and The Obsidian Blade . By experimenting with a religion so many of us subscribe to, Vanhee makes his story all the more terrifying, I think, and more personal as well.

Engines is an apocalyptic story, but it's markedly different from any other apocalyptic story you've read recently, I assure you. For one thing, it's a small, intimate story. The cast of characters numbers six, and it diminishes quickly. The setting consists of the Truth home and a neighbor's home, plus the land between them. This, too, diminishes quickly. The book gives off a very claustrophobic feel. Its huge idea - the end of the world - may seem at odds with the smallness of its cast and setting, but that's what makes it stand out, and it's a large part of what makes it so effective.

It's also incredibly disturbing. One of my favorite moments is actually something I feared was an ARC mistake at first, involving the deliciously creepy and ambiguous Minister. (The Minister may be the most brilliant thing about the entire book.) If you choose to pick up this book after reading our review (and I hope you do), look for a moment where the Minister's true nature becomes even more ambiguous than before - and then let me know if you were as creeped out by it as I was.

I loved this book for its creativity, for its daring, and for its writing - which is concise, atmospheric, and doesn't waste a single word. This is an excellent choice for readers looking for something that will stretch them a little, something that's different from anything they've read lately. I also think it would be a great pick to re-energize anyone going through a reading slump.

Kelly Says . . .

A good scary novel in my mind leaves you wondering at the end, and I find it particularly enjoyable to wonder whether or not the ending is hopeful or hopeless. Vanhee captures this perfectly in Engines of the Broken World, as we're left with a world that's been literally shattered and destroyed. But Merciful Truth is such a trouper throughout the story, making some gut-wrenching decisions, and at the end, I couldn't help wonder if the world has hardened her enough to make her actually feel hope or if she's finally succumbed to the truth of the world in which she lives: it's hopeless. Period. Because even though she has the chance to live now, the chance to get out and do things on her own terms, there are lingering forces in the world around her which she has no control over.

The fog isn't going away. If anything, it continues to grow closer. The ending of Vanhee's novel was absolutely perfect and just the way I prefer my scary stories because of this. I don't want a cut and dry answer. I want to leave wondering. But I want to be left wondering enough that I also don't want to reenter that world and discover an ending. I like that discomfort. I like there to not be a pretty bow at the end.

Kim and I talked a long time about the role of The Minister in this book when we both finished, and we've each our own take on it. I believe The Minister's role was as the false prophet in the story: it's a role he (it?) sort of takes on himself and yet it's a role that both Merciful and Gospel choose to believe in when the times become exceedingly difficult for them. And it's through their belief and worship of The Minister that their world becomes more confusing and challenging, rather than one in which they can believe stronger. For me, the role of The Minister as false idol/prophet came to a head when Merciful has to make a huge choice about taking control of the situation within the house and spirits haunting it -- spoiler here -- she has to kill The Minister. And with that comes the freedom to move on with her life and make her own choices without his guidance and his judgment of them. This act of agency was empowering for her, rather than one done out of desperation, though desperation certainly aided in her choice.

Overall, Vanhee's novel is a lot of fun. Yes, I said fun. There's definitely a body count, and there's definitely a lot of scary stuff that happens within it, but what makes it fun is that it's ballsy. Engines plays upon a lot of taboo topics and does so without backing off them. And there's a cat who talks and is (in my mind) a jerk. It's satisfying and rewarding as a reader since there are no cheap ways out. There's bloodshed, there's murder of family, and there's possession, parallel worlds, and as a reader, you'll find yourself feeling a bit paranoid.

I think this book will make some people angry because it does these things. But I think the real element of horror in this book comes because of that: if we strip away the sanctity of things in our world -- death, religion, family, pets -- and we instead look at them in another way, of course we're going to be scared. And we should be.

Pass Engines of the Broken World off to your mature YA readers who want a challenging but satisfying scary book. This one should work well for those who love Stephen King, as well as those who love a story about other worldly spirits.

Related StoriesFriday Never Leaving by Vikki WakefieldWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa Desir

Related StoriesFriday Never Leaving by Vikki WakefieldWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa Desir

Kimberly Says . . .

Merciful and Gospel Truth's mother has just died. They live on a farm in the country, and it's been cold - and getting colder - for a long time. This means they can't bury their mother in the hard ground. Instead, they put her beneath the kitchen table, which they know is wrong.

The Minister, the talking cat who lives with them, guiding their actions on the path of righteousness, tells them this is wrong. They must bury their mother, even if it means venturing out into the encroaching fog, the fog which eats away at their neighbors' bodies, leaving nothingness behind.

But they don't listen to the Minister. They leave their mother's body unburied, and Merciful realizes what a mistake they've made when she hears her dead mother's voice speaking to her. Her mother - or whatever is inhabiting her mother's body - has something to do with the fog closing in on the farmhouse, closing out the rest of the world. The Minister is also involved somehow, and one of the greatest joys of watching this story unfold are the ways Vanhee leads the reader down so many different paths. What is the true nature of the Minister, of the fog, of Merciful's mother? You'll change your mind several times over the course of the story, and you may still feel like you don't have all the answers at the end.

I like it when authors take risks with their content. There's quite a lot of religion in this book, but it doesn't come close to resembling what most would consider "Christian fiction." Because Vanhee plays with Christianity in the way he does, twisting it into something one might call horrifying, I expect a great many readers would find his book offensive.

I love that. I don't love it just because people are offended; I love that these kinds of stories are not off-limits despite that. I've written about this a little bit when I discussed Misfit and The Obsidian Blade . By experimenting with a religion so many of us subscribe to, Vanhee makes his story all the more terrifying, I think, and more personal as well.

Engines is an apocalyptic story, but it's markedly different from any other apocalyptic story you've read recently, I assure you. For one thing, it's a small, intimate story. The cast of characters numbers six, and it diminishes quickly. The setting consists of the Truth home and a neighbor's home, plus the land between them. This, too, diminishes quickly. The book gives off a very claustrophobic feel. Its huge idea - the end of the world - may seem at odds with the smallness of its cast and setting, but that's what makes it stand out, and it's a large part of what makes it so effective.

It's also incredibly disturbing. One of my favorite moments is actually something I feared was an ARC mistake at first, involving the deliciously creepy and ambiguous Minister. (The Minister may be the most brilliant thing about the entire book.) If you choose to pick up this book after reading our review (and I hope you do), look for a moment where the Minister's true nature becomes even more ambiguous than before - and then let me know if you were as creeped out by it as I was.

I loved this book for its creativity, for its daring, and for its writing - which is concise, atmospheric, and doesn't waste a single word. This is an excellent choice for readers looking for something that will stretch them a little, something that's different from anything they've read lately. I also think it would be a great pick to re-energize anyone going through a reading slump.

Kelly Says . . .

A good scary novel in my mind leaves you wondering at the end, and I find it particularly enjoyable to wonder whether or not the ending is hopeful or hopeless. Vanhee captures this perfectly in Engines of the Broken World, as we're left with a world that's been literally shattered and destroyed. But Merciful Truth is such a trouper throughout the story, making some gut-wrenching decisions, and at the end, I couldn't help wonder if the world has hardened her enough to make her actually feel hope or if she's finally succumbed to the truth of the world in which she lives: it's hopeless. Period. Because even though she has the chance to live now, the chance to get out and do things on her own terms, there are lingering forces in the world around her which she has no control over.

The fog isn't going away. If anything, it continues to grow closer. The ending of Vanhee's novel was absolutely perfect and just the way I prefer my scary stories because of this. I don't want a cut and dry answer. I want to leave wondering. But I want to be left wondering enough that I also don't want to reenter that world and discover an ending. I like that discomfort. I like there to not be a pretty bow at the end.

Kim and I talked a long time about the role of The Minister in this book when we both finished, and we've each our own take on it. I believe The Minister's role was as the false prophet in the story: it's a role he (it?) sort of takes on himself and yet it's a role that both Merciful and Gospel choose to believe in when the times become exceedingly difficult for them. And it's through their belief and worship of The Minister that their world becomes more confusing and challenging, rather than one in which they can believe stronger. For me, the role of The Minister as false idol/prophet came to a head when Merciful has to make a huge choice about taking control of the situation within the house and spirits haunting it -- spoiler here -- she has to kill The Minister. And with that comes the freedom to move on with her life and make her own choices without his guidance and his judgment of them. This act of agency was empowering for her, rather than one done out of desperation, though desperation certainly aided in her choice.

Overall, Vanhee's novel is a lot of fun. Yes, I said fun. There's definitely a body count, and there's definitely a lot of scary stuff that happens within it, but what makes it fun is that it's ballsy. Engines plays upon a lot of taboo topics and does so without backing off them. And there's a cat who talks and is (in my mind) a jerk. It's satisfying and rewarding as a reader since there are no cheap ways out. There's bloodshed, there's murder of family, and there's possession, parallel worlds, and as a reader, you'll find yourself feeling a bit paranoid.

I think this book will make some people angry because it does these things. But I think the real element of horror in this book comes because of that: if we strip away the sanctity of things in our world -- death, religion, family, pets -- and we instead look at them in another way, of course we're going to be scared. And we should be.

Pass Engines of the Broken World off to your mature YA readers who want a challenging but satisfying scary book. This one should work well for those who love Stephen King, as well as those who love a story about other worldly spirits.

Related StoriesFriday Never Leaving by Vikki WakefieldWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa Desir

Related StoriesFriday Never Leaving by Vikki WakefieldWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa Desir

Published on September 30, 2013 22:00

September 29, 2013

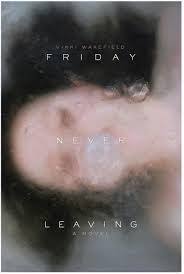

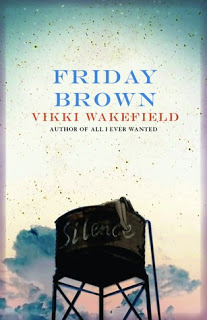

Friday Never Leaving by Vikki Wakefield

Friday Never Leaving by Vikki Wakefield came out in the US September 10, but it came out last year in Australia as Friday Brown. While I read the Australian version, from what I've figured out, little about the book has changed in the process -- except the title, some of the words (I'm assuming words like "pram" were Americanized), and the cover. While it looks like a drowning girl on the cover of the US version on the left, it's actually a perfectly fitting cover to some of the content in the story. But I think I do have a slight preference for the Australian cover, shown below. It, too, is a moment from the book and perhaps sums up the feeling of the story in a way that the US one doesn't quite capture.

Friday Brown has always lived her life moving from place to place. Her and mother Vivienne didn't stay long anywhere. They ran from their pasts, from the family curse of death by water, to new places with new hopes. But when Vivienne dies -- the first woman in the family to not be taken out by the curse, not quite -- Friday is living with her grandfather and she feels unsettled. Being in one place, that stasis, doesn't fit with her soul. And she certainly can't wrap her mind around her losses.

So she leaves.

Friday takes up residence with a group of other homeless teenagers after running into a homeless boy named Silence at the train station. He saved her and brought her back to the squatter house, where she quickly finds herself entranced with Arden. Arden entranced me too; she was powerful, she had a mystique about her, and she was captivating. She's the kind of girl who catches and captures attention.

And Arden knows this. She abuses it.

She is a woman with power.

When the squatters move on to the Outback, to a place where no one else is around them, Arden truly asserts her power and dominance. It doesn't sit well with Friday nor most of the others in the crew, but it is Friday who challenges her. And it is Friday who pays the consequences for it.

But when Friday sees her life nearing an end, after losing a friend, can she figure out how to find the place she truly needs to be? Is there such thing as stability? How do you pick yourself up again when everything you once knew is turned on its head? When the mother you thought you knew wasn't truly the person you thought she was? When moving doesn't mean freedom but instead means imprisonment? When finally you allow yourself the opportunity to grieve your losses and pick up the pieces for yourself?

Is it possible to be whole again and what does that look like?

Wakefield does an incredible job of exploring at the complexities of people. While the relationships she creates between these people is equally complex, they never quite got to the level I'd hoped for. Arden is intriguing, but we never see her power exerted until the very end. We know of it -- Friday tells us about it -- but I wanted more. In ways it's that not seeing which makes it scary, but to experience the full intensity, I wanted to see the full Arden.

I loved the relationship that emerged between Friday and Silence, though; she listened to him and she GOT him. She got his insistence that love and memory mattered, that someone is never really gone, ever, if you keep them in your mind and your heart. That learning people aren't always what they seem on the surface is hard, but it doesn't change the fact that love is something you have the right to choose to give; it's not automatic.

Wakefield's writing in Friday Never Leaving is exquisite and literary. Friday is quiet and she's observant about the world around her, particularly when it comes to Silence. The way she lovingly describes and engages in her world is easy to fall into, even if it's not pretty -- and it's not. The losses she's suffered in her life, and the life she led with mom that was never about stability or ease are not pretty things. The curse in her family, which almost gets her as well, doesn't offer us a reason for Friday to maintain the sort of optimism about her future and the world around her, and yet she does.

I think there is serious potential for this to be talked about for the Printz this year. It's challenging, multi-layered, and the writing is just damn good. I wanted to mark page after page for some of the thoughts that Friday shared and the truths she discovered. It's an achey read, not a feel-good read, and I suspect that even though I liked-not-loved it, the story and Friday's voice will remain with me for quite a while.

It's hard to put a finger on exactly what this book reads like, but I think it's a bit of a combination of Kirsten Hubbard's Like Mandarin in terms of relationships and power wielding within them, with a bit of Holly Cupala's Don't Breathe a Word, when it comes to choosing life as a homeless teen. Pass this one along to readers who want a contemporary title that's literary, that explores relationships, and that really tackles more questions than it offers answers -- and perhaps that's why this is a book that lingers and has a slower burn. There's more to wonder than there is to know.

Friday Never Leaving is an excellent title, too, for those readers who want books set abroad. Perhaps pair this one with Simmone Howell's Everything Beautiful or Melina Marchetta's realistic novels. I'm really eager to dive into some more Australian contemporary. While I've read a little bit, I think Wakefield's novel might be the one that encourages me to wade even deeper into these waters.

Friday Never Leaving is available now from Simon and Schuster. My copy was sent to me from Adele, along with a pile of other Aussie novels I am eager to read.

Related StoriesWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa DesirTime Traveling Teens

Related StoriesWhere the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)Fault Line by Christa DesirTime Traveling Teens

Published on September 29, 2013 22:00

September 26, 2013

Where the Stars Still Shine by Trish Doller (+ Giveaway)

This is a not-a-review of a book I had the honor of reading last year around this time in manuscript form and I don't feel right giving an objective review of the book because I can't.*

Where the Stars Still Shine is Trish Doller's sophomore novel, and as you might remember, I thought her debut Something Like Normal was one of the strongest books I read last year. Where the Stars Still Shine is quite different, but it's as tightly written and compelling. It's a book that's stuck with me since then and one I keep coming back to. I may have even liked it more than Something Like Normal.

Because I want to talk about the things in this book I think make it one to pick up, as well as give a general sense of the flavor of story for read alike and recommendation purposes, there are going to be spoilers. So proceed with that in mind.

Callie's mother kidnapped her, and they've been living on the road, place to place, for a long time. Callie's never been to a traditional school, her meals have often come from vending machines, and she's been subjected to repeat sexual abuse at the hands of her mother's boyfriends. But when the law finally catches up with them and Callie has the opportunity to resume a life of stability in the home of the father she doesn't really know, she's both relieved and, of course, nervous about what normal could possibly look like.

As I talked about earlier this year in a post about female sexuality, Callie has agency in the relationship she engages in with Greek boy Alex. And really, what made this book so strong for me wasn't necessarily the storyline about Callie learning how to reintegrate into a new family life -- though that definitely will appeal to many readers -- but instead, I found myself wrapped up in the relationship she begins with Alex. He's attractive and quite easy to like. He could be the easy love interest. But what made him so interesting to me is how not easy the relationship is because given Callie's own life, it cannot be easy. She's nervous and scared, despite what it is she portrays outwardly toward him. It's real and true to who she is and what her own experiences in intimate situations have been. But as she learns to trust the world around her and trust herself, she's able to have a satisfying relationship that is truly earned, rather than given.

From the standpoint of romantic relationships, Doller's book would make an excellent read alike to Lauren Myracle's The Infinite Moment of Us. And like Myracle's book, there's no holding back on honesty in the writing. It's mature and straightforward.

From the standpoint of the story's exploration of what it means to be a family and what it means to have to sew together a life when you've never had the promise of stability, Doller's book makes a strong read alike to Emily Murdoch's If You Find Me. They aren't the same book, but they share common elements of reintegrating into a family, of an absent and abusive mother (in both the absence and the presence), and both feature pretty great adults, as well. Doller's book skews more mature, not just from the aspect of older characters (Callie is 17) but in content as well.

Where the Stars Still Shine has a strong and vivid setting, too. It's set in Tarpon Springs, Florida, which has a huge Greek community, among other things. Jenna at Jenna Does Books did a series about Tarpon Springs, with photos, that's worth checking out. The book is set during the late fall and early winter, so the setting is even stronger as it's not portrayed as a tourist town or a place that's experiencing an influx of visitors. It's just what it is and where it is. In many ways, it's reminiscent of Sarah Dessen's The Moon and More -- it's a story about what happens to those who call this place home, rather than those who call it a reprieve from home. I do think readers looking for a book to turn to after Dessen will find a lot here to enjoy.

Want a chance to win a copy of Doller's book? I've got one to give away, courtesy of Bloomsbury. I'll pick a winner in a couple of weeks.

Loading...

* Disclosure: Trish sent me a copy of the manuscript to read early on because we're friends.

Related StoriesFault Line by Christa DesirTime Traveling TeensSeptember Debut YA Novels

Related StoriesFault Line by Christa DesirTime Traveling TeensSeptember Debut YA Novels

Published on September 26, 2013 22:00

Colorful Covers

A couple of years ago, there was a big brouhaha over how dark some people thought YA books had gotten - and I don't mean just the contents. Many people decried the seemingly overwhelming amount of black covers, drawing the conclusion that the color of the covers reflected the darkness of its contents.

I have opinions on this (naturally), but that's a topic for a whole other post (or several posts). What I did want to mention now is that I've actually seen a major growth in the amount of color being used on YA covers recently, most specifically fantasy covers. In particular, cover artists and designers seem to favor mixing blues, pinks, and purples in really striking ways.

I've collected a montage of recent titles below that feature this type of color usage. They're all published in 2013 or 2014. I personally love the color schemes on these. They're beautiful and quite eye-catching. For now, they stand out because they are so colorful. If more books start following suit, that will obviously change, and they'll begin to blend in just as the black covers have.

Related StoriesTwo Double-Takes& Titled: Ampersands in YA FictionHardcover to Paperback: Five Changes to Check Out

Related StoriesTwo Double-Takes& Titled: Ampersands in YA FictionHardcover to Paperback: Five Changes to Check Out

I have opinions on this (naturally), but that's a topic for a whole other post (or several posts). What I did want to mention now is that I've actually seen a major growth in the amount of color being used on YA covers recently, most specifically fantasy covers. In particular, cover artists and designers seem to favor mixing blues, pinks, and purples in really striking ways.

I've collected a montage of recent titles below that feature this type of color usage. They're all published in 2013 or 2014. I personally love the color schemes on these. They're beautiful and quite eye-catching. For now, they stand out because they are so colorful. If more books start following suit, that will obviously change, and they'll begin to blend in just as the black covers have.

Related StoriesTwo Double-Takes& Titled: Ampersands in YA FictionHardcover to Paperback: Five Changes to Check Out

Related StoriesTwo Double-Takes& Titled: Ampersands in YA FictionHardcover to Paperback: Five Changes to Check Out

Published on September 26, 2013 01:00

September 24, 2013

Worldbuilding

Worldbuilding is so important in science fiction and fantasy. I used to think I was a stickler for really believable worldbuilding, but I've come to realize that what I want more is something interesting. I can forgive something that doesn't quite make sense if it's different, if it's unique, if it makes me think "That is so cool." (This is not to say that glaring worldbuilding holes don't bother me. They do. But not as much as they do many other avid SFF readers.)

Below are a few recent-ish young adult SFF books that I think present some unique, creative, and interesting worldbuilding. I've linked to my reviews where relevant. Note that it's certainly possible to have fascinating worldbuilding in an otherwise lackluster book, so not all of the books come highly recommended overall. But they did all present something in the worldbuilding that engaged me.

Zenn Scarlett by Christian Schoon

Schoon's book takes place on a future colonized/terraformed Mars, where a group of exovets care for unusual alien life forms. I loved the creative alien animals, including ones that are so massive, the vet climbs into a pod which is then swallowed by the creature so the vet can work on it internally. There's also a sentient cockroach, which oddly enough did not give me nightmares.

Half Lives by Sara Grant

Half of Half Lives takes place in a fairly distant future. This section features a strange culture that uses odd slang and makes references that seem familiar, but not familiar enough to be completely recognizable. Learning how this culture is tied to the events of the other half of the book is what makes it really intriguing.

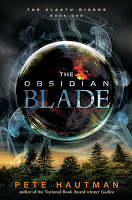

The Obsidian Blade and The Cydonian Pyramid by Pete Hautman

Hautman's time-travel books are chock full of crazy ideas. They include a couple of very well-realized, very futuristic, and very odd cultures. What makes these cultures so intriguing is the way Hautman reveals how they developed from our own contemporary cultures. It's fascinating to read about something so bizarre (like a "disease" involving math) springing from something we consider to be very mundane.

Incarnate and Asunder by Jodi Meadows

In Meadows' world, each person who dies is reincarnated in a new body, her memories intact. It's a cool plot device but also a fascinating bit of worldbuilding. Imagine the possibilities of an entire culture with a collective memory that goes back centuries. Imagine friendships and relationships that have existed that long, and will continue to exist in perpetuity. How different would those relationships be from our own, relatively fleeting ones?

Vessel by Sarah Beth Durst

Liyana lives in a world where gods can quite literally take over the bodies of humans, who offer themselves as sacrifices to those they worship. I love how the gods here are not imaginary (or simply non-interventionist), but very, very real. I also dug the desert setting, which is a refreshing change from the more cookie-cutter medieval Western European settings found so often in fantasy.

Crewel by Gennifer Albin

Albin's book straddles the line between fantasy and science fiction. Some inhabitants of Arras, the world in which the book is set, have the ability to literally weave the fabric of that world. These spinsters can change the physical layout of Arras, up to and including obliterating a person out of existence, by weaving (or breaking) threads. It's an intriguing worldbuilding concept, I think, but a little under-developed.

What other books would you add?

Below are a few recent-ish young adult SFF books that I think present some unique, creative, and interesting worldbuilding. I've linked to my reviews where relevant. Note that it's certainly possible to have fascinating worldbuilding in an otherwise lackluster book, so not all of the books come highly recommended overall. But they did all present something in the worldbuilding that engaged me.

Zenn Scarlett by Christian Schoon

Schoon's book takes place on a future colonized/terraformed Mars, where a group of exovets care for unusual alien life forms. I loved the creative alien animals, including ones that are so massive, the vet climbs into a pod which is then swallowed by the creature so the vet can work on it internally. There's also a sentient cockroach, which oddly enough did not give me nightmares.

Half Lives by Sara Grant

Half of Half Lives takes place in a fairly distant future. This section features a strange culture that uses odd slang and makes references that seem familiar, but not familiar enough to be completely recognizable. Learning how this culture is tied to the events of the other half of the book is what makes it really intriguing.

The Obsidian Blade and The Cydonian Pyramid by Pete Hautman

Hautman's time-travel books are chock full of crazy ideas. They include a couple of very well-realized, very futuristic, and very odd cultures. What makes these cultures so intriguing is the way Hautman reveals how they developed from our own contemporary cultures. It's fascinating to read about something so bizarre (like a "disease" involving math) springing from something we consider to be very mundane.

Incarnate and Asunder by Jodi Meadows

In Meadows' world, each person who dies is reincarnated in a new body, her memories intact. It's a cool plot device but also a fascinating bit of worldbuilding. Imagine the possibilities of an entire culture with a collective memory that goes back centuries. Imagine friendships and relationships that have existed that long, and will continue to exist in perpetuity. How different would those relationships be from our own, relatively fleeting ones?

Vessel by Sarah Beth Durst

Liyana lives in a world where gods can quite literally take over the bodies of humans, who offer themselves as sacrifices to those they worship. I love how the gods here are not imaginary (or simply non-interventionist), but very, very real. I also dug the desert setting, which is a refreshing change from the more cookie-cutter medieval Western European settings found so often in fantasy.

Crewel by Gennifer Albin

Albin's book straddles the line between fantasy and science fiction. Some inhabitants of Arras, the world in which the book is set, have the ability to literally weave the fabric of that world. These spinsters can change the physical layout of Arras, up to and including obliterating a person out of existence, by weaving (or breaking) threads. It's an intriguing worldbuilding concept, I think, but a little under-developed.

What other books would you add?

Published on September 24, 2013 22:00

September 23, 2013

Fault Line by Christa Desir

Ani is the new girl. She's a bit challenging -- not exactly "nice," not exactly "pleasant," and not exactly the kind of girl boys go wild over because, well, she's hard.

Ben is the kind of guy who could be with any girl. He's charming. He's attractive. But Ben wants to be with no one other than Ani. Her tough exterior is exactly what he finds attractive. Sure, at first it's almost a bit of a game to him, but it's quickly much more than simply getting with the girl who seems too hard to be won over. He finds himself really loving Ani and wanting to spend as much time with her as possible.

But after the party -- one Ani went to and Ben did not -- things change. Ani isn't the same girl she was before. And Ben can't do anything right anymore. He can't make her better, despite how much he desperately wants to.

Fault Line is Christa Desir's debut novel, and it takes a hard topic head-on: sexual assault. Or maybe I should be clearer. This isn't necessarily a book about what happens to a girl after she's raped. This isn't necessarily about who is the perpetrator or who is the savior. It's a book wholly about what it means to be a victim of sexual assault and sexual violence, and what it means to not know. Because this book isn't told from Ani's point of view but Ben's, we get the story through his perspective as the boyfriend of the girl who went to a party and woke up the next morning in a hospital.

Ben is the boyfriend of the girl who had a lighter found inside her body after the party. After the party where many heard her talking about how she was going to "get with" a bunch of boys and ended up in a room with one -- maybe more than one -- boy. After the party where her drink may or may not have been spiked. After the party where she may or may not have given consent for what happened to her and where she may or may not have been the one to insert a lighter inside her body.

And all Ben wants to do is make Ani feel better.

When he arrives at the hospital the next day, he's met by a victim's advocate, who runs down what she knows of what happened, but more importantly, what next steps he needs to take to ensure Ani is able to best recover. Be there for her, but don't push her. Don't beg her for details. And most importantly, never, ever blame her for what happened. She was the victim. What happened to her isn't her value, and it isn't what judgment of her as a person should be based upon.

Desir's novel about sexual assault from the perspective of a male voice -- one who did not initiate the incident -- is compelling and honest. It's brutal and what happened to Ani is incredibly difficult to read, not only as a woman but as a person, period. As much as he wants to protect her, Ben knows there is really only so much he can do. He can BE there for her, and he is. He tries, and even though many reviewers have faulted him for trying too hard, I disagree. Some reviews saying, for example, that his attempt to have sex with her in a very positive, very loving and caring manner, are his attempts at assaulting her himself. When she says no, he stops. He's not aggressive. He's trying so hard to offer her the safe and loving feelings she has allowed herself to forget about because those things -- those safe things, those good things, those truly intimate things -- are what were taken from her and what she believes she does not deserve anymore.

This book should be talked about for what it covers and how it covers it. It should be talked about because it does offer a lot of tricky territory to talk about. Did Ben go too far in trying to have sex with Ani when she wasn't ready? What signs did she give him to indicate what her feelings were?

Beyond those, though, there's the invaluable discussion to arise here about blame. If a victim can't remember what happened or was too intoxicated to give proper consent, is what happened to her her own fault? If there aren't readily named assailants, who is at fault? As the title suggests, what ARE the fault lines with cases like this? Because no date rape drugs showed up in Ani's system, who gets to make the call of whether or not she had been drugged before she was in a room alone with people? It's not just a timely story -- it's timeless. These are questions we wrestle with all the time, and they are questions we should wrestle with because the more we open up discourse on topics like sexual assault, on victim blaming, and other heavy hitters tackled in this book, the more we're able to be better about discussing them. The more we're able to understand when we're intentionally or unintentionally perpetrating problematic beliefs and ideas of sex and sexuality. The more we're able to understand why it is so damn problematic that we look at the girl (or boy!) as the person who was asking for it, rather than the one who became a victim of other people's inability to control their urges.

However.

There are many problems with the writing in Fault Line. At times, this book's agenda is far too obvious. It's important what messages are conveyed here -- don't blame the victim, be supportive, listen to them -- but the way it's laid down from a volunteer counselor in info dumps is overwhelming and diminishes the characters. Ben is a good guy. He wants to be good. He loves and honors Ani. But he doesn't get the chance to do that or be that for her because the counselor takes over and tells him what to do, point A to point B. He scoffs at it, even though he follows it. But why can't he do this and figure it out himself? Why is it handed to him and by extension, handed to the reader? If we want to start a conversation and start thinking about these issues heavily, we need the chance to see them, to absorb them, and to make the sorts of connections we need to individually. In other words....we aren't living in a world where that sort of clinical speak gets through. It's through our own actions and cognitive skills we put these things together.

It was the easy way out.

My other big criticism: why do we need the prologue? Why is it the most crucial scene in the book, the one that ultimately changes Ben's actions, is what we lead with? It kills tension, it kills growth, and it kills the impact of the story when we get the apex to kick off the book. We know almost immediately that Ani's story isn't going to have a positive resolution, and by leading off with this, Fault Line manages to simply shock. Where others have found the lighter to be the shock value moment in the story -- and I never did because it felt real and authentic and absolutely gut-wrenchingly awful -- for me the teacher scene opening the story was the shock value moment. Had it been left only at the end, I'd have felt much differently. It was resolution and closure, however uncomfortable. But opening? It was just there to shock.

This book would make for a killer pairing with Erica Lorraine Scheidt's Uses for Boys in talking about sex. Neither book is shy. Neither book is afraid to put the characters into positions that are uncomfortable to read and uncomfortable to think about or talk about. But they both are important in advancing conversations we need to be having. Obviously, this is a book to also pair with Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak and maybe even more so, Chris Lynch's Inexcusable. This is a book many people will be divided on, and I suggest spending some time reading the low-rated reviews over on Goodreads because they're eye opening.

I . . . have to talk about the cover of this book because it is perhaps the most upsetting element for me as a reader. And not just as a reader, but as a person who is exceptionally careful about and sensitive to discussions of rape and victimization, and as a librarian who understands full well the intentions behind the image choice here. It's a striking and appealing cover, isn't it? It's gender neutral, and I'd go as far as to say it does an excellent job of appealing particularly to male readers because it features a lighter, a catchy title, and the author's name isn't obviously feminine. The tag line "Who do you blame?" is enticing. The entire package begs to be picked up, particularly to male readers. Going to the back cover, too, readers will know the story is told from Ben's point of view. It's a male voice with a male-driven cover.

But I take mega issue with the lighter as the image choice.

That lighter was an object that violated Ani's body.

Fault Line isn't Ani's story -- it's Ben's story. And Ben's story only exists because of what happened to Ani. Her story becomes his story. That's fair and realistic and I think it's what makes Desir's book stand out in many ways. We get to hear what it means to be the one who is helpless and what it means to stand by someone who has been victim of something horrific.

That lighter was an object that violated Ani's body, though. Had the book been told through Ani's point of view, that cover would represent her reclaiming her body vis a vis the object. It would be her ownership of story.

But on the cover of Ben's story? That lighter represents the story he steals from her. It's there as shock. It's there to sell her story in an enticing way. That lighter is not Ben's. It does not belong to him. That part of the story is not his nor will it ever be. It's a lighter that traumatized Ani.

This cover steals her story as a means of selling his.

I'm really uncomfortable with that, and I really dislike that as a means of reaching a certain readership, that is the choice that was made. In many ways, that choice does precisely the opposite of not only what the story aims to say, but it does precisely what has happened in the high-profile sexual assault and rape cases we hear about everywhere. Steubenville is about the football players and what happened to their poor beautiful bright careers. It's never about the girl who they victimized. Her story is co-opted. It's not fair, and the longer I've thought about this cover, the more uncomfortable and upset it's made me. Because it does exactly what it should not be doing.

For me, the cover undermines a lot of the positive in the book, whether that's fair or not. To make the point the book attempts to make, the cover steals that away. And that's unbelievably unfortunate. While it might get new readers to pick up the book who may have otherwise scoffed at the idea of a "rape story," I certainly hope they reflect upon that choice. Because it reinforces a lot of what the story attempts to dismantle. We take a step forward in the story to protect the victim, to honor her and listen to her. But then we take ten steps back on the cover because this isn't her story, but we're going to sell the book with the object of violation. There's a disconnect.

Fault Line will be available October 1 from Simon Pulse. Review copy received from the publisher.

Related StoriesTime Traveling TeensSeptember Debut YA NovelsLiterary Inspirations: YA Characters Hooked on Inspiration

Related StoriesTime Traveling TeensSeptember Debut YA NovelsLiterary Inspirations: YA Characters Hooked on Inspiration

Published on September 23, 2013 22:00

Banned Books at Book Riot

I've got a post over at Book Riot today and wanted to link it over here and add a little bit more commentary. I'm talking about all of the challenges and book bannings that have happened over the last month.

I wanted to talk about this for a couple of reasons. First, I hate the idea that we celebrate banned books. I think it's terrible we celebrate the banned books aspect, rather than celebrate the other angle to it, which is intellectual freedom. We need to celebrate the freedom to choose, rather than the items that become representative of what happens when that right is taken from us.

Second, I think it is important to consider how much attention the recent invitation-revoking and removal of Eleanor & Park from Anoka County has received -- and where it's come from. The impassioned pleas people have written in defense of the book and the author's visit aren't coming from within the book community. They aren't coming from the library world or the publishing world. They're coming from the main stream, including NPR and The Toast. I think this is incredibly important and it leaves me wondering what would happen if this sort of widespread attention could be given to the other books challenged or banned this month alone.

Note the range of books I've talked about, too: they all feature "outsiders." Chew it over. Imagine what would happen if we got angry about all of this and were able to better shine light to it outside our own world, where we are well aware of this sort of thing happening. How do we keep grabbing wider attention?

Related StoriesAll over the place at Book RiotOver at Book RiotElsewhere in the book world

Related StoriesAll over the place at Book RiotOver at Book RiotElsewhere in the book world

Published on September 23, 2013 13:03

September 22, 2013

Guest Post: Raina Telgemeier on Fairy Tale Comics

Today we're excited to have a short interview with Raina Telgemeier, as part of the blog tour for Fairy Tale Comics, which we reviewed on Friday. Do you know how fun it was to be asked if we wanted to interview Raina? We dug her take on Rapunzel and we were excited to ask her more about it. If you want to see what other contributors to the book have had to say about their art, you can see who else is talking and where they're talking here.

How did you become involved in the project? Were you approached by the editor and pitched a particular fairy tale, or did you select it yourself?

Editor Chris Duffy asked if I wanted to adapt Rapunzel for the book. It was a pretty easy decision.

What inspired you most with the source material of Rapunzel? When was the moment you knew how to approach the story?

One of the versions of Rapunzel I read included the detail about her mother being pregnant with her, and craving the rapunzel plant growing in a neighbor’s garden. That seemed very human. I like gardens and plants and vegetables (although I don’t have much of a green thumb myself), so weaving them into the story made sense. Logistically, the trickiest part was figuring out a way to avoid violence and death--which I realize is an important part of many fairy tales. But I just don’t have a taste for it.

Do you go for art first or story first? What's your process?

For me they come together, as thumbnails. I knew I was working with an 8-page template, so I spent a few days reading over the various versions of the tale Chris sent, highlighting and rearranging my favorite elements from all of them, and then sat down and thumbnailed it all in a couple hours on a Sunday afternoon.

What challenges, if any, did you encounter writing such a short story compared with your long-form graphic novels?

With short stories, it’s all about compression. Most of the Rapunzel tales cover her birth, her childhood, and then the more dramatic events when she is a teenager. Some also jump ahead in time to Rapunzel living in the woods with the twins she and the prince have conceived. Distilling that all into a satisfying short was challenging, but I liked being able to strip away all the unnecessary components. Like most fairy tales, the story has a bone structure that works.

What fairy tale re-tellings or interpretations have you loved, in comics form or not?

We had various versions of fairy tale books and records and such around my house; my favorite thing was a German board game called Enchanted Forest, which had little game pieces shaped like pine trees, and each one had a tiny round illustration of a different fairy tale on the bottom.

I’m a Disney girl through and through, and with the exception of Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella, I love all the fairy tales they’ve adapted (those two leave me a little cold). However, I avoided re-watching Disney’s version of Rapunzel during this project, because I didn’t want to be too influenced by it.

If you were to create another fairy tale in comic style, which would you choose, why would you choose it, and what "twist" would you add to make it all your own?

Maybe Jack and the Beanstalk. Endlessly tall stalks and a castle in the clouds sound like fun to draw.

What's next for you?

I’m working on a companion to my first graphic novel, Smile, called Sisters. That will be out in September of 2014.

Related StoriesDual Review: Fairy Tale Comics edited by Chris DuffyBattling Boy by Paul PopeTwitterview: Carrie Mesrobian (author of Sex & Violence)

Related StoriesDual Review: Fairy Tale Comics edited by Chris DuffyBattling Boy by Paul PopeTwitterview: Carrie Mesrobian (author of Sex & Violence)

Published on September 22, 2013 22:00

September 20, 2013

Links of Note: 9/21/13

Let's put James Franco on all the covers.

So we're more than half-way through September and I don't know about you, but I didn't realize that until the moment I began typing this. I'm still thinking it's May.

Here's a roundup of some of the things that have caught my eye in the last couple of weeks that I think are worth reading -- and if you're looking for a good laugh, make sure you click the link under the Franco cover above because I laughed until I hurt.

Here's one for the bloggers/social networking folks: why successful networks breed good ideas. A lot of good food for thought on how and why writing and sharing on the internet are positive things.

Librarian Valerie Forrestal wrote an excellent piece about redefining success in one's career, particularly in a field like librarianship where honors and recognition can be contentious things. But this isn't just for librarians. This piece has fantastic advice for anyone who works.

Did you watch Daria when it was on TV? Because I did. I love this book list created by someone over at Goodreads which highlights all of the books Daria either read or talked about on the show.

Malinda Lo compiled a series of charts and graphs to talk about diversity in YA as it applies to YALSA's Best Fiction for Young Adults lists between 2011 and 2013. This is a multiple reader piece -- there is a lot to digest.

Speaking of longer reads requiring some digestion, there's this post by Foz Meadows about what mechanics we use when choosing our next reads. But more than that, it's a musing about representation and browsing for books, particularly in brick-and-mortar stores. As I said, not light reading but certainly worthwhile.

Are you reading YA Interrobang? It's a weekly online magazine started by Nicole of WORD for Teens, and it's fantastic. New issues are on Sundays -- put it on your weekly reading rotation.

Actual research that proves the point everyone who cares about reading knows already: reading for pleasure helps children do better in school.

Next month I'll be posting a review of Robin Wasserman's latest YA book The Waking Dark, but I wanted to share this great interview she did with Entertainment Weekly. Specifically, I found the discussion of how dark is too dark in YA was interesting. It got me thinking about how dark is too dark (I don't think that exists) but more than that, whether or not my own expectations of dark are impacted by genre distinction. I read Wasserman's book as straight-up horror, so I expected darkness. But would I feel that way if I hadn't read with my perceptions of darkness and horror in mind?

How about YA authors who write or have written for television? Here's a roundup of a few!

For fun: if you're listening to Welcome to Night Vale, I hope you've seen these incredible maps of what Night Vale might look like.

Liz Burns has a great post about sexism and technology and how we possibly introduce girls into both.

And if you're in or near Austin, Texas next weekend, you should come out to the Austin Teen Book Festival. I'll be there, and Kimberly likely will be, too.

Related StoriesLinks of Note: 9/7/13Links of Note, 8/24/13"Inside the Industry" Guest Post and Quick Survey

Related StoriesLinks of Note: 9/7/13Links of Note, 8/24/13"Inside the Industry" Guest Post and Quick Survey

Published on September 20, 2013 22:00

September 19, 2013

Dual Review: Fairy Tale Comics edited by Chris Duffy

Kelly's Thoughts

Kelly's ThoughtsI'm not a huge fan of fairy tales. I like them well enough, but there's little that compels me to pick up a fairy tale retelling -- a good hook or jump off the tale can do it, though. And Fairy Tale Comics, edited by Chris Duffy, has a fantastic one: it's a graphic collection of shortened fairy tales that span from your well-known stories to those which are far less well-known. Even more compelling is the fact this collection involves work from a lot of well-known artists in the comic world whose other works I've either enjoyed or are familiar with.

In other words, this isn't just any re-made fairy tale comic book. It adds something entirely new.

All of the art is stylistic to the artist, as are the ways that they spin their fairy tales. These are shortened versions of the stories, so it is interesting to see what was kept in and what was removed -- or what was swapped around all together.

Gigi D. G. did a spin on Little Red Riding Hood that was subtle but which made me fall in love with the way the story was told -- rather than have the lumberjack be male, as it's traditionally presented, it's a female in this version. My favorite in the entire book in terms of art was Gilbert Hernandez's Hansel and Gretel. Though I didn't love it at first, I warmed up to it because it's really funny. The expressions on the faces are excellent, and the use of color is really dynamic. The final page is perhaps where it shines the most: we see the kids shoving the witch in the oven, and there's a great juxtaposition of the bright, candy-colored images with the house burning down, with red and black. It's almost jarring, but in a way that's funny.

I was a fan of Raina Telgemeier's take on Rapunzel and I really liked the new-to-me fairy tale by Luke Pearson, The Boy Who Drew Cats. Even though it was unfamiliar to me, I found myself enjoying the read AND the art -- one didn't outshine the other. Graham Annable's take on Goldilocks and the Three Bears surprised me in a positive way, being wordless and just as effective a story without the words to tell it. Even those who might not be familiar with the tale (little kids) would completely understand it by art alone.

What makes Fairy Tale Comics enjoyable is that even those stories and interpretations that didn't work for me were quick and when I lost interest in a couple of them, I didn't feel bad skipping them. This collection has some misses, but other readers may find what I consider a miss to be really stand out. The book is perfectly appropriate for very young readers, as well as those who are older.

Kimberly's Thoughts

This collection is worth reading even if you only read The Boy Who Drew Cats. In fact, after I finished it, I made my boyfriend stop what he was doing and read it immediately so he could experience its joy. It's so different from the other mostly Grimm and Perrault tales and completely refreshing. Also, very very funny. (Its author/artist, Luke Pearson, is also the creator of the 2012 Cybils finalist Hilda and the Midnight Giant , another supremely weird and weirdly funny little graphic story that I enjoyed quite a lot.)

The other stories, as in most collections, were hit and miss for me. While there's certainly an enormous amount of creativity here, I was a little disappointed by how straightforward some of the tales were. By that I mean they followed very closely the storyline most readers are accustomed to, without a new twist to make them a bit fresher. The art is almost uniformly outstanding and interesting, but I wish there had been a little more oomph to the stories themselves.

I compare these stories to Nursery Rhyme Comics , the previous collaboration by graphic storytellers edited by Duffy. By necessity, authors/artists had to be a bit more creative when interpreting the rhymes, since the rhymes themselves were frequently nonsensical and didn't have a built-in story. It was interesting to see how the artists could draw the rhymes to give them a story (or not). By contrast, most of the authors in Fairy Tale Comics stuck to the traditional stories you've likely read before.

That said, the graphic format may make the stories fresh enough for most readers anyway. There are a few writers/artists who took things a little bit sideways, making them more their own. (The female lumberjack is a good example.) And as Kelly mentioned, it's a great collection for young readers who may come to many of these stories with new eyes, never having read them anywhere else before.

Fairy Tale Comics will be available on Tuesday. Review copy provided by the publisher.

Related StoriesBattling Boy by Paul PopeGraphic Memoirs & "New Adult" BooksWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

Related StoriesBattling Boy by Paul PopeGraphic Memoirs & "New Adult" BooksWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

Published on September 19, 2013 22:00