Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 137

August 15, 2013

Audio Review: A Matter of Days by Amber Kizer

The BluStar pandemic has killed most of the Earth's population. Nadia and her little brother Rabbit (nickname for Robert) managed to survive thanks to an injection given to them by their Uncle Bean, who somehow knew what was going to happen and had a vaccine available. Their mother, though, never got the shot, and after Nadia and Rabbit watch her die, they pack up the family's Jeep and head out east, intending to travel to their Pappy's home, where Uncle Bean mentioned he'd meet them when he saw them last.

They know it's not going to be an easy trip, but their father - a military man who died a few years ago - taught them how to "be the cockroach" and "survive the effects." They know how to shoot a gun, how to forage for food and supplies, how to survive without electricity. Rabbit actually read up on survival guides while Nadia was taking care of their dying mother, so he neatly avoids embodying the annoying younger sibling trope. He's a kid, sure, but he's also helpful.

The story is very episodic: Nadia and Rabbit travel for a bit, make a stop, run into some trouble (with wildlife, unsavory people, or the environment), survive it, then move on. They're alone for much of the story, though they do pick up some strays along the way (a dog, a bird, a teenage boy, and a little girl).

The narration, done by Alex McKenna, is a failure. She voices Rabbit like a 60-year-old with a lifetime smoking habit. Nadia doesn't fare much better, but the problem with her voice (which is the primary one, since this is a first-person story) is where McKenna chooses to place emphasis. More often than not, she'll overemphasize entire sentences that should have been read neutrally or matter-of-fact. When sentences should be emphasized, the words she chooses to emphasize are strange and don't carry the meaning she intends. It often made me wrinkle my brow in confusion and brought me out of the story.

Still, the book wasn't a complete loss. Despite its episodic nature, I found myself fairly engaged, in a "If I miss a bit of this because I'm not fully focused on it, it's not a big deal" way (great for driving!). There's no complicated overarching storyline that the listener needs to puzzle out - just a girl and a boy traveling across the country, meeting and overcoming a series of obstacles.

In a way, this reads like a younger version of Ashfall , except with a pandemic instead of a supervolcano. But where Ashfall was frequently harrowing, A Matter of Days is not nearly so dark or filled with tension. There is certainly danger, but it's not felt very strongly. Most of the story involves the fairly mundane aspects of survival: finding food and fuel, coping with poor hygiene, navigating roads full of stalled vehicles. For the most part, I thought it was nice to read a book without having to constantly worry if a beloved character would be violently murdered (or eaten).

That's not to say there is no threat of violence. There is, but much of it occurred in the past. Nadia and Rabbit stumble upon a lot of dead bodies, and not all from BluStar. Nadia does have occasion to use her gun, and they run into some people who wish them harm. Where other end-of-the-world survival stories tend to emphasize the violence, though, A Matter of Days tries instead to emphasize the kids' loss and the other non-violent horrors. Nadia and Rabbit are now orphans, and they're not even sure Pappy and Uncle Bean will still be alive when they reach their destination. There's a genuinely heartbreaking moment during a flashback as Nadia cares for her mother on her deathbed. There's also a lovely moment when Nadia is hiding from a group of violent raiders in a room with a decomposing body and she mentions she tries to swallow her own vomit. Early on in the book, Nadia and Rabbit rescue a dog and have to pick glass out of its paws. There's not a lot of blood, but there are a lot of moments like these.

This will probably appeal to fans of Ashfall, though hardcore post-apocalyptic readers will likely find it a bit tame for their tastes. (And I'd recommend picking it up in print.) If you'd like to listen to a bit of the book and see if you agree with me about the narration, Random House has an excerpt on their website.

Finished copy received from the publisher. A Matter of Days is available now.

Related StoriesThe Infinite Moment of Us by Lauren MyracleTo Be Perfectly Honest by Sonya SonesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

Related StoriesThe Infinite Moment of Us by Lauren MyracleTo Be Perfectly Honest by Sonya SonesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

Published on August 15, 2013 22:00

August 14, 2013

Graphic Memoirs & "New Adult" Books

The topic of "new adult" has been talked about left and right. I even talked about it earlier this week.

As a take-away for the conversation starter than Sophie Brookover, Liz Burns, and myself gave at ALA in June, we developed a fairly thorough resource list, with links to not only the articles, blog posts, and discussions surrounding the newly-emerging idea of "new adult" books, but it included a lengthy reading list of books that have been published as "new adult," as well as books that weren't published as "new adult" but which explored the themes we teased out as hallmarks to this category of books.

What is "new adult," if it's a thing at all? One of the definitions that keeps coming back around is that "new adult" explores the themes and challenges of being on your own for the first time -- whatever that may mean. It could mean what happens when you go away to college. It could mean what happens when you move into your first apartment by yourself or when you're moving back home with your parents after four years away at school. It could mean discovering how to navigate new relationships and new careers outside the safety net of high school or parental supervision. Roughly, these are books that explore the tricky things that happen in your life as a "new adult," or when you're somewhere between the ages of 18 and 26.

Of course, this is a slightly problematic definition in matching up what has been published as "new adult," since nearly every book published in this category has been a contemporary (and steamy) romance. It doesn't include those who marry young or those who don't necessarily attend college but choose a trade to go into (or choose a gap year or choose not to do go into a traditional career path at all). Likewise, the differences in experiences of those actually attending college and those just out of college are so different it's tough to wrap them all into a singular category and point to one media as an example of good "new adult." In other words, saying that Girls is a prime example of the category points to "new adult" being something wholly different than pointing to a book about a girl's first year in college being "new adult."

I'm not sold on this being a category. I'm still solidly in the camp that rather than try to define a type of book that's always been on the market as adult (or as YA, as the case may be for some of the books being lumped into the "new adult" category), we should look more closely at the importance of crossover appeal in books. The 18-26 age range is all about crossing over: you're walking the bridge between adolescence to true independence and adulthood. Whatever that looks like depends upon the individual. There aren't specific milestones to make because, unlike adolescence which is marked with somewhat shared milestones -- think learning to drive, graduating high school, and so forth -- adulthood is about defining your own milestones. Whether that's choosing to rent an apartment for the first time, choosing to attend college, or choosing to pursue marriage/children/a career or all of the above in tandem.

To that effect, it seems to make more sense to pull from those books already being published within the traditional category definitions of Young Adult and Adult. These books exist and these books can fit into the reading interests and needs of those interested in the so-called "new adult" realm. I've mentioned before that by exploding the definition outward and reconsidering these books as crossovers rather than as "new adult," then we're opening the doors to the possibility that emerging adulthood is a much broader, richer experience than what we're seeing played out right now as contemporary romance. The opportunity for change is here, but it seems like we offer more value and service to these books and their readers by building from what's already here than trying to start fresh and limit ourselves to a singular idea of "new adult."

As was mentioned during our panel in June and something I've been thinking about a LOT is that as it stands now, "new adult" is very white, very middle class, and very sexy. There is nothing inherently wrong with the books published as "new adult" being this way, but there is a problem if that's the only experience being mirrored. Someone in the audience mentioned that perhaps if the definition of what a good "new adult" book is is what I've listed above -- about the experiences of maturation and learning to make choices independently about one's life and being able to do so without the constraints of adolescence -- perhaps urban fiction offers a wealth of "new adult" books, as well, since they tread these themes and have been for quite a while.

Since the talk about "new adult" began, I've put considerable thought into the role that alternative formats may play in the discussion about the category and about the value they have in crossover appeal.

I've been a huge fan of graphic memoirs for quite a while now. I've read most of what's been traditionally published in the last few years. I've talked before about my love for Julia Wertz's graphic memoirs before. And in thinking about why it is I love these books, in conjunction with why I really like the show Girls, I've come to the idea that the reason why I like all of these things is because they hit upon the very ideas that books considered "new adult" hit upon. They're about learning to separate from the comfort and security afforded to the narrator (generally the author, but not always) and come to understand one's own place and roles as a new grown up. It's not pretty, and in fact, much of the appeal for me in these books is that they are downright ugly because they're true. Being an adult isn't always about the pretty romance. Often, it's about the baggage and the backstory and how those things inform the character and his or her choices. The character doesn't always make the right choices, either. Sometimes those choices are downright dumb.

But it's okay because they're still new at this. They're still learning when they can revert to the behaviors of their teenhood and when they need to put on grownup lenses to proceed. They're walking the bridge and making choices.

They are crossing over.

I think any discussion of "new adult" without exploration of graphic novels -- and graphic memoirs in particular -- is one that overlooks an entire category of books with tremendous crossover appeal for the readers looking for these themes (and character ages) in story. With that in mind, I thought I'd offer up a reading list of some strong graphic memoirs that definitely fall into what we're thinking about as "new adult." These books have great crossover appeal to them: teen readers looking for stories about being a young adult will find something here, as will adults who are looking for books that either they relate to because they're of the age the main character is or to adults who are looking for books that explore those tough times of emerging adulthood.

This is a format and genre I turn to when I'm looking for something "different," and I find that I'm rarely disappointed. I love the way the art interacts with the narrative, and I love the narratives themselves which are compelling and often quite relatable (I'm not too far removed from the age range that many consider "new adult"). I love that sometimes these stories take place at the end of high school and sometimes they take place when the main character is in his or her mid-20s. Sometimes the story is told entirely through reflection and isn't from a current perspective at all -- in other words, it's looking back at this time and age, rather than living through it.

My list isn't exhaustive, and I'd love to know of additional graphic memoirs that might fit the bill. I'm especially interested in the male or diverse experience -- I was going to include Persepolis in this list, as well, and perhaps I could since it fits a nice crossover niche as well. Are there historical graphic memoirs worth looking at, too?

All descriptions are from WorldCat.

Calling Dr. Laura by Nicole J. Georges: When Nicole Georges was two years old, her family told her that her father was dead. When she was twenty-three, a psychic told her he was alive. Her sister, saddled with guilt, admits that the psychic is right and that the whole family has conspired to keep him a secret. Sent into a tailspin about her identity, Nicole turns to radio talk-show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger for advice-- Calling Dr. Laura tells the story of what happens to you when you are raised in a family of secrets, and what happens to your brain (and heart) when you learn the truth from an unlikely source.

Kiss & Tell: A Romantic Resume Ages 0 to 22 by MariNaomi: Recounts the author's romantic experiences, from first love to heartbreak.

Life with Mr. Dangerous by Paul Hornschemeier (not technically a graphic memoir but it's so close to the storytelling in the otherwise listed memoirs that I'm including it): Somewhere in the Midwest, Amy Breis is going nowhere. Amy has a job she hates, a creep boyfriend she's just dumped, and a best friend she can't reach on the phone. But at least her (often painfully passive-aggressive) mother bought her a pink unicorn sweatshirt for her birthday. Pink. Unicorn. For her twenty-sixth birthday. Gliding through the daydreams and realities of a young woman searching for definition.

Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me by Ellen Forney: Shortly before her thirtieth birthday, Ellen Forney was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Flagrantly manic but terrified that medications would cause her to lose her creativity and livelihood, she began a years-long struggle to find mental stability without losing herself or her passion. Searching to make sense of the popular concept of the "crazy artist," Ellen found inspiration from the lives and work of other artist and writers who suffered from mood disorders, including Vincent van Gogh, Georgia O'Keeffe, William Styron, and Sylvia Plath.

Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel: Graphic memoir about Bechdel's troubled relationship with her distant, unhappy mother and her experiences with psychoanalysis, with particular reference to the work of Donald Winnicott.

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel: This book takes its place alongside the unnerving, memorable, darkly funny family memoirs of Augusten Burroughs and Mary Karr. It's a father-daughter tale perfectly suited to the graphic memoir form. Meet Alison's father, a historic preservation expert and obsessive restorer of the family's Victorian house, a third-generation funeral home director, a high school English teacher, an icily distant parent, and a closeted homosexual who, as it turns out, is involved with male students and a family babysitter. Through narrative that is alternately heartbreaking and fiercely funny, we are drawn into a daughter's complex yearning for her father. And yet, apart from assigned stints dusting caskets at the family-owned 'fun home, ' as Alison and her brothers call it, the relationship achieves its most intimate expression through the shared code of books. When Alison comes out as homosexual herself in late adolescence, the denouement is swift, graphic, and redemptive.

Little Fish by Ramsey Beyer (September 3, with a little more emphasis on prose than art): Told through real-life journals, collages, lists, and drawings, this coming-of-age story illustrates the transformation of an 18-year-old girl from a small-town teenager into an independent city-dwelling college student. Written in an autobiographical style with beautiful artwork, Little Fish shows the challenges of being a young person facing the world on her own for the very first time and the unease—as well as excitement—that comes along with that challenge. Description via Goodreads.

My Friend Dahmer by Derf Backderf: You only think you know this story. In 1991, Jeffrey Dahmer, the most notorious serial killer since Jack the Ripper, seared himself into the American consciousness. To the public, Dahmer was a monster who committed unthinkable atrocities. To Derf Backderf, 'Jeff' was a much more complex figure: a high school friend with whom he had shared classrooms, hallways, and car rides. In [this story], a haunting and original graphic novel, writer-artist Backderf creates a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of a disturbed young man struggling against the morbid urges emanating from the deep recesses of his psyche-- a shy kid, a teenage alcoholic, and a goofball who never quite fit in with his classmates. With profound insight, what emerges is a Jeffrey Dahmer that few ever really knew, and one readers will never forget.

French Milk by Lucy Knisley: A lighthearted travelogue--rendered in the form of a graphic novel--about a mother and daughter's life-changing six-week trip to Paris is comprised of the graphic artist daughter's illustrations of the sights and scenes they visited while each was facing a milestone birthday.

Relish by Lucy Knisley: Lucy Knisley loves food. The daughter of a chef and a gourmet, this talented young cartoonist comes by her obsession honestly. In her forthright, thoughtful, and funny memoir, Lucy traces key episodes in her life thus far, framed by what she was eating at the time and lessons learned about food, cooking, and life. Each chapter is bookended with an illustrated recipe-- many of them treasured family dishes, and a few of them Lucy's original inventions.

*Between the two, I think that French Milk falls more into the "new adult" category, as it explores more of the college experience than does Relish. Both both are excellent.

The Infinite Wait and Other Stories by Julia Wertz: These are comics filled with the sometimes messy, heartbreaking and hilarious moments that make up a life. (What's particularly good about this one is that it explores what happens when the career you thought was in your back pocket ends up not being so -- and all when you're young).

Related StoriesGet Genrefied*: Graphic NovelsThe Summer Before it All: A Reading ListWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

Related StoriesGet Genrefied*: Graphic NovelsThe Summer Before it All: A Reading ListWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

As a take-away for the conversation starter than Sophie Brookover, Liz Burns, and myself gave at ALA in June, we developed a fairly thorough resource list, with links to not only the articles, blog posts, and discussions surrounding the newly-emerging idea of "new adult" books, but it included a lengthy reading list of books that have been published as "new adult," as well as books that weren't published as "new adult" but which explored the themes we teased out as hallmarks to this category of books.

What is "new adult," if it's a thing at all? One of the definitions that keeps coming back around is that "new adult" explores the themes and challenges of being on your own for the first time -- whatever that may mean. It could mean what happens when you go away to college. It could mean what happens when you move into your first apartment by yourself or when you're moving back home with your parents after four years away at school. It could mean discovering how to navigate new relationships and new careers outside the safety net of high school or parental supervision. Roughly, these are books that explore the tricky things that happen in your life as a "new adult," or when you're somewhere between the ages of 18 and 26.

Of course, this is a slightly problematic definition in matching up what has been published as "new adult," since nearly every book published in this category has been a contemporary (and steamy) romance. It doesn't include those who marry young or those who don't necessarily attend college but choose a trade to go into (or choose a gap year or choose not to do go into a traditional career path at all). Likewise, the differences in experiences of those actually attending college and those just out of college are so different it's tough to wrap them all into a singular category and point to one media as an example of good "new adult." In other words, saying that Girls is a prime example of the category points to "new adult" being something wholly different than pointing to a book about a girl's first year in college being "new adult."

I'm not sold on this being a category. I'm still solidly in the camp that rather than try to define a type of book that's always been on the market as adult (or as YA, as the case may be for some of the books being lumped into the "new adult" category), we should look more closely at the importance of crossover appeal in books. The 18-26 age range is all about crossing over: you're walking the bridge between adolescence to true independence and adulthood. Whatever that looks like depends upon the individual. There aren't specific milestones to make because, unlike adolescence which is marked with somewhat shared milestones -- think learning to drive, graduating high school, and so forth -- adulthood is about defining your own milestones. Whether that's choosing to rent an apartment for the first time, choosing to attend college, or choosing to pursue marriage/children/a career or all of the above in tandem.

To that effect, it seems to make more sense to pull from those books already being published within the traditional category definitions of Young Adult and Adult. These books exist and these books can fit into the reading interests and needs of those interested in the so-called "new adult" realm. I've mentioned before that by exploding the definition outward and reconsidering these books as crossovers rather than as "new adult," then we're opening the doors to the possibility that emerging adulthood is a much broader, richer experience than what we're seeing played out right now as contemporary romance. The opportunity for change is here, but it seems like we offer more value and service to these books and their readers by building from what's already here than trying to start fresh and limit ourselves to a singular idea of "new adult."

As was mentioned during our panel in June and something I've been thinking about a LOT is that as it stands now, "new adult" is very white, very middle class, and very sexy. There is nothing inherently wrong with the books published as "new adult" being this way, but there is a problem if that's the only experience being mirrored. Someone in the audience mentioned that perhaps if the definition of what a good "new adult" book is is what I've listed above -- about the experiences of maturation and learning to make choices independently about one's life and being able to do so without the constraints of adolescence -- perhaps urban fiction offers a wealth of "new adult" books, as well, since they tread these themes and have been for quite a while.

Since the talk about "new adult" began, I've put considerable thought into the role that alternative formats may play in the discussion about the category and about the value they have in crossover appeal.

I've been a huge fan of graphic memoirs for quite a while now. I've read most of what's been traditionally published in the last few years. I've talked before about my love for Julia Wertz's graphic memoirs before. And in thinking about why it is I love these books, in conjunction with why I really like the show Girls, I've come to the idea that the reason why I like all of these things is because they hit upon the very ideas that books considered "new adult" hit upon. They're about learning to separate from the comfort and security afforded to the narrator (generally the author, but not always) and come to understand one's own place and roles as a new grown up. It's not pretty, and in fact, much of the appeal for me in these books is that they are downright ugly because they're true. Being an adult isn't always about the pretty romance. Often, it's about the baggage and the backstory and how those things inform the character and his or her choices. The character doesn't always make the right choices, either. Sometimes those choices are downright dumb.

But it's okay because they're still new at this. They're still learning when they can revert to the behaviors of their teenhood and when they need to put on grownup lenses to proceed. They're walking the bridge and making choices.

They are crossing over.

I think any discussion of "new adult" without exploration of graphic novels -- and graphic memoirs in particular -- is one that overlooks an entire category of books with tremendous crossover appeal for the readers looking for these themes (and character ages) in story. With that in mind, I thought I'd offer up a reading list of some strong graphic memoirs that definitely fall into what we're thinking about as "new adult." These books have great crossover appeal to them: teen readers looking for stories about being a young adult will find something here, as will adults who are looking for books that either they relate to because they're of the age the main character is or to adults who are looking for books that explore those tough times of emerging adulthood.

This is a format and genre I turn to when I'm looking for something "different," and I find that I'm rarely disappointed. I love the way the art interacts with the narrative, and I love the narratives themselves which are compelling and often quite relatable (I'm not too far removed from the age range that many consider "new adult"). I love that sometimes these stories take place at the end of high school and sometimes they take place when the main character is in his or her mid-20s. Sometimes the story is told entirely through reflection and isn't from a current perspective at all -- in other words, it's looking back at this time and age, rather than living through it.

My list isn't exhaustive, and I'd love to know of additional graphic memoirs that might fit the bill. I'm especially interested in the male or diverse experience -- I was going to include Persepolis in this list, as well, and perhaps I could since it fits a nice crossover niche as well. Are there historical graphic memoirs worth looking at, too?

All descriptions are from WorldCat.

Calling Dr. Laura by Nicole J. Georges: When Nicole Georges was two years old, her family told her that her father was dead. When she was twenty-three, a psychic told her he was alive. Her sister, saddled with guilt, admits that the psychic is right and that the whole family has conspired to keep him a secret. Sent into a tailspin about her identity, Nicole turns to radio talk-show host Dr. Laura Schlessinger for advice-- Calling Dr. Laura tells the story of what happens to you when you are raised in a family of secrets, and what happens to your brain (and heart) when you learn the truth from an unlikely source.

Kiss & Tell: A Romantic Resume Ages 0 to 22 by MariNaomi: Recounts the author's romantic experiences, from first love to heartbreak.

Life with Mr. Dangerous by Paul Hornschemeier (not technically a graphic memoir but it's so close to the storytelling in the otherwise listed memoirs that I'm including it): Somewhere in the Midwest, Amy Breis is going nowhere. Amy has a job she hates, a creep boyfriend she's just dumped, and a best friend she can't reach on the phone. But at least her (often painfully passive-aggressive) mother bought her a pink unicorn sweatshirt for her birthday. Pink. Unicorn. For her twenty-sixth birthday. Gliding through the daydreams and realities of a young woman searching for definition.

Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me by Ellen Forney: Shortly before her thirtieth birthday, Ellen Forney was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Flagrantly manic but terrified that medications would cause her to lose her creativity and livelihood, she began a years-long struggle to find mental stability without losing herself or her passion. Searching to make sense of the popular concept of the "crazy artist," Ellen found inspiration from the lives and work of other artist and writers who suffered from mood disorders, including Vincent van Gogh, Georgia O'Keeffe, William Styron, and Sylvia Plath.

Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel: Graphic memoir about Bechdel's troubled relationship with her distant, unhappy mother and her experiences with psychoanalysis, with particular reference to the work of Donald Winnicott.

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel: This book takes its place alongside the unnerving, memorable, darkly funny family memoirs of Augusten Burroughs and Mary Karr. It's a father-daughter tale perfectly suited to the graphic memoir form. Meet Alison's father, a historic preservation expert and obsessive restorer of the family's Victorian house, a third-generation funeral home director, a high school English teacher, an icily distant parent, and a closeted homosexual who, as it turns out, is involved with male students and a family babysitter. Through narrative that is alternately heartbreaking and fiercely funny, we are drawn into a daughter's complex yearning for her father. And yet, apart from assigned stints dusting caskets at the family-owned 'fun home, ' as Alison and her brothers call it, the relationship achieves its most intimate expression through the shared code of books. When Alison comes out as homosexual herself in late adolescence, the denouement is swift, graphic, and redemptive.

Little Fish by Ramsey Beyer (September 3, with a little more emphasis on prose than art): Told through real-life journals, collages, lists, and drawings, this coming-of-age story illustrates the transformation of an 18-year-old girl from a small-town teenager into an independent city-dwelling college student. Written in an autobiographical style with beautiful artwork, Little Fish shows the challenges of being a young person facing the world on her own for the very first time and the unease—as well as excitement—that comes along with that challenge. Description via Goodreads.

My Friend Dahmer by Derf Backderf: You only think you know this story. In 1991, Jeffrey Dahmer, the most notorious serial killer since Jack the Ripper, seared himself into the American consciousness. To the public, Dahmer was a monster who committed unthinkable atrocities. To Derf Backderf, 'Jeff' was a much more complex figure: a high school friend with whom he had shared classrooms, hallways, and car rides. In [this story], a haunting and original graphic novel, writer-artist Backderf creates a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of a disturbed young man struggling against the morbid urges emanating from the deep recesses of his psyche-- a shy kid, a teenage alcoholic, and a goofball who never quite fit in with his classmates. With profound insight, what emerges is a Jeffrey Dahmer that few ever really knew, and one readers will never forget.

French Milk by Lucy Knisley: A lighthearted travelogue--rendered in the form of a graphic novel--about a mother and daughter's life-changing six-week trip to Paris is comprised of the graphic artist daughter's illustrations of the sights and scenes they visited while each was facing a milestone birthday.

Relish by Lucy Knisley: Lucy Knisley loves food. The daughter of a chef and a gourmet, this talented young cartoonist comes by her obsession honestly. In her forthright, thoughtful, and funny memoir, Lucy traces key episodes in her life thus far, framed by what she was eating at the time and lessons learned about food, cooking, and life. Each chapter is bookended with an illustrated recipe-- many of them treasured family dishes, and a few of them Lucy's original inventions.

*Between the two, I think that French Milk falls more into the "new adult" category, as it explores more of the college experience than does Relish. Both both are excellent.

The Infinite Wait and Other Stories by Julia Wertz: These are comics filled with the sometimes messy, heartbreaking and hilarious moments that make up a life. (What's particularly good about this one is that it explores what happens when the career you thought was in your back pocket ends up not being so -- and all when you're young).

Related StoriesGet Genrefied*: Graphic NovelsThe Summer Before it All: A Reading ListWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

Related StoriesGet Genrefied*: Graphic NovelsThe Summer Before it All: A Reading ListWill & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

Published on August 14, 2013 22:00

August 13, 2013

Rewriting History (aka Lying to Our Children)

In the most recent issue of Kirkus, there are two reviews for books that feature Laika, the dog who was sent into space by the Soviet space program and died there (a return trip was never planned). Laika's life (and death) is dealt with sensitively and realistically in Nick Abadzis' 2007 graphic novel, simply titled

Laika

.

Stories about dogs dying are not new for kids. In fact, I'd say that children's books where the dog dies have a long and storied history in the English-speaking world, from Old Yeller to Where the Red Fern Grows to Sharon Creech's Love That Dog. There's even a joke that people often tell: If the children's book has a picture of a dog on it, that dog is a goner. ("Go to the library and pick out a book with an award sticker and a dog on the cover. Trust me, that dog is going down." -Gordan Korman's No More Dead Dogs). Dog deaths are painful, naturally, but kids aren't unaccustomed to reading about them.

I was a little surprised, then, to pick up the latest issue of Kirkus and read about two books being published in October that give a much more, shall we say, creative ending to Laika's story. One seems to outright lie; the other is a bit more of a fantasy. In both of these stories, the author imagines a happier end for Laika.

In Laika: Astronaut Dog by Owen Davey (picture book, Candlewick), Laika ends up living on an alien spaceship. What really happened is mentioned in a more text-heavy author's note, and as we know, author's notes are often skipped. Most kids will probably know that the alien spaceship is not real, but Davey doesn't tell us Laika's true end in the story proper, either. Fanciful, yes. Honest? Not so much.

In A Curious Robot on Mars by James Duffett-Smith (picture book, Sky Pony Press), Laika is not the primary character. That honor belongs to the Mars rover, who discovers, after its own mission ends, that Sputnik and Laika are living on Mars and makes friends with them. Unlike Davey's book, the entire story here is clearly a fantasy, but it doesn't erase the fact that Laika's true fate isn't mentioned. Does it need to be?

I wonder what motivates this kind of historical revision. We want to save our children from pain, certainly, but that doesn't explain why we keep publishing novels where the dog dies, where such an event is most likely meant to elicit pain. Perhaps it's easier to deal with if it's fictional, since we can tell our children "It's just a story. It's not real." Laika's death is real, and perhaps that makes it harder.

I can't completely buy that argument, though, since kids whose families have dogs will most likely experience their pet's death before they get too old. Dogs simply don't live very long when compared to humans. Dog deaths are real; they happen to kids every day.

Perhaps it's because Laika's death was intentional, planned. Perhaps it's because her story shows how adults use other living things for their own advancement, with little to no regard for that living thing's well-being or ultimate fate. Perhaps it's because it reveals the deliberate and casual cruelty of grown-ups, and that makes people uncomfortable. I'm not entirely sure.

I should note that the Kirkus reviewer calls out the first title as "cowardly." (The second title is dismissed more for its artwork.) I haven't read it myself, but it seems altogether too disingenuous. When we write about hard and painful things that happened in the past, we need to be truthful. There's a way to do it gently and sensitively, to make it appropriate for children at different ages and maturity levels. Lying (even by omission) isn't the way to do it.

What do you think about these stories, and others like them that sugarcoat or even rewrite unpleasant parts of history for kids?

Related StoriesLittle White Duck: A Childhood in China by Na Liu and Andres Vera Martinez

Related StoriesLittle White Duck: A Childhood in China by Na Liu and Andres Vera Martinez

Stories about dogs dying are not new for kids. In fact, I'd say that children's books where the dog dies have a long and storied history in the English-speaking world, from Old Yeller to Where the Red Fern Grows to Sharon Creech's Love That Dog. There's even a joke that people often tell: If the children's book has a picture of a dog on it, that dog is a goner. ("Go to the library and pick out a book with an award sticker and a dog on the cover. Trust me, that dog is going down." -Gordan Korman's No More Dead Dogs). Dog deaths are painful, naturally, but kids aren't unaccustomed to reading about them.

I was a little surprised, then, to pick up the latest issue of Kirkus and read about two books being published in October that give a much more, shall we say, creative ending to Laika's story. One seems to outright lie; the other is a bit more of a fantasy. In both of these stories, the author imagines a happier end for Laika.

In Laika: Astronaut Dog by Owen Davey (picture book, Candlewick), Laika ends up living on an alien spaceship. What really happened is mentioned in a more text-heavy author's note, and as we know, author's notes are often skipped. Most kids will probably know that the alien spaceship is not real, but Davey doesn't tell us Laika's true end in the story proper, either. Fanciful, yes. Honest? Not so much.

In A Curious Robot on Mars by James Duffett-Smith (picture book, Sky Pony Press), Laika is not the primary character. That honor belongs to the Mars rover, who discovers, after its own mission ends, that Sputnik and Laika are living on Mars and makes friends with them. Unlike Davey's book, the entire story here is clearly a fantasy, but it doesn't erase the fact that Laika's true fate isn't mentioned. Does it need to be?

I wonder what motivates this kind of historical revision. We want to save our children from pain, certainly, but that doesn't explain why we keep publishing novels where the dog dies, where such an event is most likely meant to elicit pain. Perhaps it's easier to deal with if it's fictional, since we can tell our children "It's just a story. It's not real." Laika's death is real, and perhaps that makes it harder.

I can't completely buy that argument, though, since kids whose families have dogs will most likely experience their pet's death before they get too old. Dogs simply don't live very long when compared to humans. Dog deaths are real; they happen to kids every day.

Perhaps it's because Laika's death was intentional, planned. Perhaps it's because her story shows how adults use other living things for their own advancement, with little to no regard for that living thing's well-being or ultimate fate. Perhaps it's because it reveals the deliberate and casual cruelty of grown-ups, and that makes people uncomfortable. I'm not entirely sure.

I should note that the Kirkus reviewer calls out the first title as "cowardly." (The second title is dismissed more for its artwork.) I haven't read it myself, but it seems altogether too disingenuous. When we write about hard and painful things that happened in the past, we need to be truthful. There's a way to do it gently and sensitively, to make it appropriate for children at different ages and maturity levels. Lying (even by omission) isn't the way to do it.

What do you think about these stories, and others like them that sugarcoat or even rewrite unpleasant parts of history for kids?

Related StoriesLittle White Duck: A Childhood in China by Na Liu and Andres Vera Martinez

Related StoriesLittle White Duck: A Childhood in China by Na Liu and Andres Vera Martinez

Published on August 13, 2013 22:00

Elsewhere in the book world

I wanted to do a quick roundup of some of my posts in other places over the last week or so before I forget to!

Over at Book Riot, I've got a post today about kid lit as it has been represented on stamps throughout the world (and there are some awesome stamps here, I think -- I love how differently different countries have interpreted these stories into art).

Last week at Book Riot, I talked about Sherman Alexie's Part-Time Indian and more specifically how adults are ultimately responsible for the hyper sexualizing of young adult fiction (I borrowed a line from the mom who was angry about Alexie's book and called the post "Fifty Shades for Kids").

I was asked this year to be an instructor for Write On Con, a fully online and free conference for writers. It's awesome, and you should check it out if you're a writer OR you work with writers (this is a killer resource for teachers and librarians who work with teens who love writing).

I wrote about the three things that good contemporary YA can teach you about writing in any genre. Because my specialty is reading rather than writing fiction, the emphasis is on examples throughout contemporary YA -- so it should offer some solid contemporary (and non contemporary!) book recommendations.

Also as part of my post, I'm giving away a 10-page first chapter critique. Entering involves just commenting on the post in some way.

I think that covers it.

Have I mentioned how much Kimberly and I appreciate everyone who reads STACKED, comments here, shares our posts or otherwise engages with us? Thank you!

Related StoriesLinks of Note: August 3, 2013Post on Adults Fearing YA at Book RiotLinks of Note: July 13, 2013

Related StoriesLinks of Note: August 3, 2013Post on Adults Fearing YA at Book RiotLinks of Note: July 13, 2013

Over at Book Riot, I've got a post today about kid lit as it has been represented on stamps throughout the world (and there are some awesome stamps here, I think -- I love how differently different countries have interpreted these stories into art).

Last week at Book Riot, I talked about Sherman Alexie's Part-Time Indian and more specifically how adults are ultimately responsible for the hyper sexualizing of young adult fiction (I borrowed a line from the mom who was angry about Alexie's book and called the post "Fifty Shades for Kids").

I was asked this year to be an instructor for Write On Con, a fully online and free conference for writers. It's awesome, and you should check it out if you're a writer OR you work with writers (this is a killer resource for teachers and librarians who work with teens who love writing).

I wrote about the three things that good contemporary YA can teach you about writing in any genre. Because my specialty is reading rather than writing fiction, the emphasis is on examples throughout contemporary YA -- so it should offer some solid contemporary (and non contemporary!) book recommendations.

Also as part of my post, I'm giving away a 10-page first chapter critique. Entering involves just commenting on the post in some way.

I think that covers it.

Have I mentioned how much Kimberly and I appreciate everyone who reads STACKED, comments here, shares our posts or otherwise engages with us? Thank you!

Related StoriesLinks of Note: August 3, 2013Post on Adults Fearing YA at Book RiotLinks of Note: July 13, 2013

Related StoriesLinks of Note: August 3, 2013Post on Adults Fearing YA at Book RiotLinks of Note: July 13, 2013

Published on August 13, 2013 11:29

August 12, 2013

To Be Perfectly Honest by Sonya Sones

I've known of Sonya Sones since I began working in a library, but I never actually picked up one of her books. She's been perennially popular, and I thought it about time to see just why. To Be Perfectly Honest was an excellent introduction and I am looking forward to becoming familiar with her back list sooner, rather than later.

As fair warning, this review is pretty spoiler heavy. So if you don't want to know what makes this book the way it is, come back after you've read it for yourself.

Colette's mother is a movie star, and this summer, she's shuffling Colette and her little brother away from their home and the promise summer in Paris. They're heading instead to a small town in California where she's filming her next movie. Colette's beyond bummed about this. But when she meets Connor, she starts to sing a little bit of a different tune. Maybe it won't be so bad when there's a cute boy around.

Something to know about Colette: she's a liar. She lies about everything. And it's not that she's an unreliable narrator. She's completely reliable -- if you accept she's a liar.

Colette and Connor are in love or so it feels. And when Colette tells her mother she needs alone time with Connor, away from her brother, her mother grants this wish to her. She even leaves a box of condoms, in order for them to be truly safe.

But Colette's not ready for that quite yet. Even though she's told Connor she's 18 (she's not -- she's 15) and that she's sexually-experienced (she's not -- she's a virgin), when the time comes for them to take their relationship somewhere more physical, she takes a stand and says no.

That's when Connor gets back at her for her lies.

He wants to get with Colette so badly, he tells her he has cancer. He goes as far as to make himself look sick -- a slick little trick Colette herself has tried in order to get attention. As a reader, I had a suspicion he was lying about this. Part of why my suspicions were raised was because up until this point in the story, I had been on board. I couldn't wrap my head around Sones taking such an easy way out of the story. No way would this go down the road of making the reader and Colette feel bad for Connor now because he's got cancer. I had much more trust in the story than that, and I am so glad I did.

But Colette is none the wiser, nor would she be. He's convincing! His head is bald. He looks sick.

It's all a rouse so he can get her to sleep with him. And yes, it's a big charade for a sexual encounter, but as he tells her later, he's gone further. It was a conquest for him. To make it more disturbing, he's not 18 like he claims. He's 21.

Since no sex goes down -- Colette figures him and his lies out before it could happen -- there's no rape, no charges.

But now she wants to get back and get even.

Except, Colette comes around before the big "gotcha" happens.

The turnaround in Colette is believable and I was appreciative of it. I didn't love her as a character but that's why I was compelled by her. In fact, when she was prepared to take Connor for a ride herself, I was really invested. Would she REALLY go through with her plans or was this a rouse on us, as readers?

In the end, we don't really know. Perhaps that's what made the book successful for me as a reader, the never knowing whether what was going on was truth or if Colette was playing a big game upon us as readers.

I felt the end of this book was almost a cheap way out of the story. But I had to remember the main character is 15 -- she'd just turned 16 at that point -- and so it was less of a cheap way out and more of a realistic way out of HER story. I believe her and it, even if it wasn't my favorite ending.

Sones masters verse novels. This is how verse works. It plays with the story, telling readers enough while leaving just the right amount UNSAID to make the reader wonder where and how Colette is leading us on. Her voice is spot on, and I thought the relationship she had with her learning-disabled younger brother was sweet and authentic. The wrap up with her mother and her mother's boyfriend was a little schmaltzy for me, but it was believable in context of the story.

To Be Perfectly Honest is for YA readers who like challenging characters, who like verse novels, and who are good with "tough" topics like sex, drugs, and drinking in their books. Even though Colette is on the younger side, this is one to hand to younger teen readers only if they're ready and like those topics tackled in their books (and many do!). I wouldn't put this on the level of Ellen Hopkins in terms of content, but I'd say it's a stepping stone to readers who will go to Hopkins down the road.

It's possible I'll talk about this in another post about repackaged book covers, but I wanted to say I love what they've done to update Sones's books to appeal to today's teens. They've gone through a few transformations, but these are by far my favorite:

They're fresh and feel so contemporary. I love when books that are popular in the library, like these, do get new looks a few years after their publication because when it's time to replace the battered or missing copies, they really do look new.

To Be Perfectly Honest is available today. Review copy received from the publisher.

Related StoriesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangOCD Love Story by Corey Ann HayduThe Summer Before it All: A Reading List

Related StoriesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangOCD Love Story by Corey Ann HayduThe Summer Before it All: A Reading List

Published on August 12, 2013 22:00

August 11, 2013

The Summer Before it All: A Reading List

I've talked about "new adult" books and those books which have tremendous crossover appeal because they're the kinds of books that YA readers and adult readers would appreciate. The main characters may be a little bit older -- eighteen, nineteen -- and they're no longer in high school. They might be in college or just out of college. I've talked at length about "new adult" and how crossovers may or may not fit into the idea of whatever "new adult" is or might become in the future.

But I haven't written about those books set in that delicate place between high school and college (or whatever comes after high school in terms of more education or a career). It's that summer of infinite possibility, where the main character straddles the line of being under the control of someone or something else and where she or he may be able to have complete and total freedom. When high school ends, that summer feels endless, both in a good way and in a bad way. In many ways, this summer is the first true taste of freedom. With that, the challenges of breaking free of the old ways of high school, of being a teenager, and the new challenges of being alone and on your own.

It isn't surprising that many of the books I pulled together that take place in this summer between an ending and a beginning take place on the road. The road trip narrative is, in many ways, that exact metaphor played out: you're navigating the old, moving forward toward something new and exciting/scary. A number of these also feature a summer romance, putting to question not just the idea of a summer fling, but what change and transition plays in attachment and attraction. There's also a lot of exploration of sexuality -- again, I suspect a good deal of that being the change in social pressure, both from the high school environment and from the home environment. What you like and what feels good to you can really emerge in new and interesting ways during this summer.

This is a small list of YA books that take place in that summer. I'd love to know of more titles that address this time period. I'm not interested in those books which use this time period as part of their time period. I want the books to be solidly set only in this period -- so Just One Day wouldn't count because it then follows through the following school year. I'm particularly interested in male-led stories, too. I have a small number from my memory/notes, but I know there have to be others as well. If there are any adult marketed titles that tackle this summer, lay those on me as well. As usual, my reading leans realistic, but if there are genre titles that fit the topic, leave those in the comments, too.

All descriptions are from WorldCat.

The Book of Broken Hearts by Sarah Ockler: Jude has learned a lot from her older sisters, but the most important thing is this: The Vargas brothers are notorious heartbreakers. But as Jude begins to fall for Emilio Vargas, she begins to wonder if her sisters were wrong.

The After Girls by Leah Konen: When their best friend Astrid commits suicide after high school graduation, Ella searches for answers while Sydney tries to dull the pain, and both girls look to uncover Astrid's dark secrets when they receive a mysterious Facebook message.

With or Without You by Brian Farrey: When eighteen-year-old best friends Evan and Davis of Madison, Wisconsin, join a community center group called "chasers" to gain acceptance and knowledge of gay history, there may be fatal consequences.

A Midsummer's Nightmare by Kody Keplinger: Suffering a hangover from a graduation party, eighteen-year-old Whitley is blindsided by the news that her father has moved into a house with his fiancée, her thirteen-year-old daughter Bailey, and her son Nathan, in whose bed Whitley had awakened that morning.

Kiss the Morning Star by Elissa Janine Hoole: The summer after high school graduation and one year after her mother's tragic death, Anna and her long-time best friend Kat set out on a road trip across the country, armed with camping supplies and a copy of Jack Kerouac's Dharma Bums, determined to be open to anything that comes their way.

Wanderlove by Kirsten Hubbard: Bria, an aspiring artist just graduated from high school, takes off for Central America's La Ruta Maya, rediscovering her talents and finding love.

The Disenchantments by Nina LaCour: Colby's post-high school plans have long been that he and his best friend Bev would tour with her band, then spend a year in Europe, but when she announces that she will start college just after the tour, Colby struggles to understand why she changed her mind and what losing her means for his future.

The Moon and More by Sarah Dessen: During her last summer at home before leaving for college, Emaline begins a whirlwind romance with Theo, an assistant documentary filmmaker who is in town to make a movie.

When You Were Here by Daisy Whitney: When his mother dies three weeks before his high school graduation, Danny goes to Tokyo, where his mother had been going for cancer treatments, to learn about the city his mother loved and, with the help of his friends, come to terms with her death.

The Infinite Moment of Us by Lauren Myracle: As high school graduation nears, Wren Gray is surprised to connect with gentle Charlie Parker, a boy with a troubled past who has loved her for years, while she considers displeasing her parents for the first time and changing the plans for her future. This book comes out later in August.

Roomies by Sara Zarr and Tara Altebrando: While living very different lives on opposite coasts, seventeen-year-old Elizabeth and eighteen-year-old Lauren become acquainted by email the summer before they begin rooming together as freshmen at UC-Berkeley. This book comes out at the end of the year, and the story ends when the girls meet one another in person.

Lovestruck Summer by Melissa Walker: Quinn plans to enjoy her summer in Austin, Texas, working for a record company, even though she has to live with her cousin Penny. The description doesn't tell you a whole lot about much, but it's set in the summer before Quinn goes to college. Not related to the setting, but I really dig the new cover for this one -- it's a fan-designed cover for the ebook version that Walker just released herself via Kindle (it was published in print by Harper).

Related StoriesWill & Whit by Laura Lee GulledgeNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

Related StoriesWill & Whit by Laura Lee GulledgeNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

But I haven't written about those books set in that delicate place between high school and college (or whatever comes after high school in terms of more education or a career). It's that summer of infinite possibility, where the main character straddles the line of being under the control of someone or something else and where she or he may be able to have complete and total freedom. When high school ends, that summer feels endless, both in a good way and in a bad way. In many ways, this summer is the first true taste of freedom. With that, the challenges of breaking free of the old ways of high school, of being a teenager, and the new challenges of being alone and on your own.

It isn't surprising that many of the books I pulled together that take place in this summer between an ending and a beginning take place on the road. The road trip narrative is, in many ways, that exact metaphor played out: you're navigating the old, moving forward toward something new and exciting/scary. A number of these also feature a summer romance, putting to question not just the idea of a summer fling, but what change and transition plays in attachment and attraction. There's also a lot of exploration of sexuality -- again, I suspect a good deal of that being the change in social pressure, both from the high school environment and from the home environment. What you like and what feels good to you can really emerge in new and interesting ways during this summer.

This is a small list of YA books that take place in that summer. I'd love to know of more titles that address this time period. I'm not interested in those books which use this time period as part of their time period. I want the books to be solidly set only in this period -- so Just One Day wouldn't count because it then follows through the following school year. I'm particularly interested in male-led stories, too. I have a small number from my memory/notes, but I know there have to be others as well. If there are any adult marketed titles that tackle this summer, lay those on me as well. As usual, my reading leans realistic, but if there are genre titles that fit the topic, leave those in the comments, too.

All descriptions are from WorldCat.

The Book of Broken Hearts by Sarah Ockler: Jude has learned a lot from her older sisters, but the most important thing is this: The Vargas brothers are notorious heartbreakers. But as Jude begins to fall for Emilio Vargas, she begins to wonder if her sisters were wrong.

The After Girls by Leah Konen: When their best friend Astrid commits suicide after high school graduation, Ella searches for answers while Sydney tries to dull the pain, and both girls look to uncover Astrid's dark secrets when they receive a mysterious Facebook message.

With or Without You by Brian Farrey: When eighteen-year-old best friends Evan and Davis of Madison, Wisconsin, join a community center group called "chasers" to gain acceptance and knowledge of gay history, there may be fatal consequences.

A Midsummer's Nightmare by Kody Keplinger: Suffering a hangover from a graduation party, eighteen-year-old Whitley is blindsided by the news that her father has moved into a house with his fiancée, her thirteen-year-old daughter Bailey, and her son Nathan, in whose bed Whitley had awakened that morning.

Kiss the Morning Star by Elissa Janine Hoole: The summer after high school graduation and one year after her mother's tragic death, Anna and her long-time best friend Kat set out on a road trip across the country, armed with camping supplies and a copy of Jack Kerouac's Dharma Bums, determined to be open to anything that comes their way.

Wanderlove by Kirsten Hubbard: Bria, an aspiring artist just graduated from high school, takes off for Central America's La Ruta Maya, rediscovering her talents and finding love.

The Disenchantments by Nina LaCour: Colby's post-high school plans have long been that he and his best friend Bev would tour with her band, then spend a year in Europe, but when she announces that she will start college just after the tour, Colby struggles to understand why she changed her mind and what losing her means for his future.

The Moon and More by Sarah Dessen: During her last summer at home before leaving for college, Emaline begins a whirlwind romance with Theo, an assistant documentary filmmaker who is in town to make a movie.

When You Were Here by Daisy Whitney: When his mother dies three weeks before his high school graduation, Danny goes to Tokyo, where his mother had been going for cancer treatments, to learn about the city his mother loved and, with the help of his friends, come to terms with her death.

The Infinite Moment of Us by Lauren Myracle: As high school graduation nears, Wren Gray is surprised to connect with gentle Charlie Parker, a boy with a troubled past who has loved her for years, while she considers displeasing her parents for the first time and changing the plans for her future. This book comes out later in August.

Roomies by Sara Zarr and Tara Altebrando: While living very different lives on opposite coasts, seventeen-year-old Elizabeth and eighteen-year-old Lauren become acquainted by email the summer before they begin rooming together as freshmen at UC-Berkeley. This book comes out at the end of the year, and the story ends when the girls meet one another in person.

Lovestruck Summer by Melissa Walker: Quinn plans to enjoy her summer in Austin, Texas, working for a record company, even though she has to live with her cousin Penny. The description doesn't tell you a whole lot about much, but it's set in the summer before Quinn goes to college. Not related to the setting, but I really dig the new cover for this one -- it's a fan-designed cover for the ebook version that Walker just released herself via Kindle (it was published in print by Harper).

Related StoriesWill & Whit by Laura Lee GulledgeNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

Related StoriesWill & Whit by Laura Lee GulledgeNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang

Published on August 11, 2013 22:00

August 8, 2013

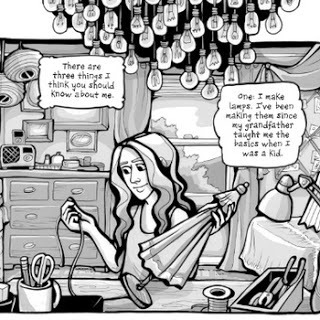

Will & Whit by Laura Lee Gulledge

We're human. All we are are beautiful contradictions.

Will -- short for Wilhelmina after her deceased grandmother -- is a creative soul. Will lives with her aunt who runs the family antique store; it's a job she inherited. It was only a year ago that Will moved in with her aunt Ella, after her mother and father died tragically and suddenly.

Important things to know about Willa that she'll tell you herself: she's an old soul. She loves creating lamps and playing with light. And she's scared of the dark.

Important things to know about Willa that she won't tell you: she's creative, passionate, romantic, and deeply aching inside from all of the loss in her life these last few years. When hurricane Whitney roars into town and the city is left without power, Willa is forced to face the shadows in her life head-on. Is she as strong as the face she's putting on? Is she allowed to show a moment of weakness? Can she let herself have a break?

Will & Whit is Laura Lee Gulledge's sophomore graphic novel, and while it's not as compelling as Page by Paige , it's still a well-drawn, well-written story about the means and ways of creative people. This is the kind of book that you know the readership for -- it's those teens who always feel a little on the outside, who love to creative and express and explore and sometimes lose the core of themselves in the midst of it or who feel like they'll never fit in with other people because of their passion. They live big lives internally and externally, even when it means that sometimes, their wants and their drive can collide with real world things.

Will is an incredibly complex main character. She comes off at times like she's well beyond her years, but she's really not. Will puts on a tough face, and it's one she carries off by constantly reminding people how awesome and talented they are while taking a step back and brushing off those things in herself. This is her grieving process. She can't break, and she won't allow herself the chance to cry, to get angry, to feel all of the ugly things that accompany loss. Doing so would mean she can't be there for her aunt. It would mean not being there for her best friends Autumn and Noel. It would mean not being the cheerleader in everyone else's life.

But she can't escape those shadows, even as she tries to repress them.

The storm is what sets the story into motion. Will has agreed to help a group of local kids with their low-budget carnival (think talent show more than ferris wheels here) by getting her friend to do a puppet show. But when the power is knocked out and the carnival kids need someone who can help illuminate the show, they seek her out personally. She has the light skills. She has the passion for creating and manipulating light. This is her chance to shine -- literally. It's a small and subtle moment but it highlights the entirety of Will's story: rather than step in and offer her own talents to the show when she hears about it, she offers up the talent of her friend. Even when she herself is asked to take part, she's still a little take aback that she has something worthwhile to offer.

When she's convinced, though, she discovers the importance of letting herself showcase her talents . . . and letting herself be comforted by those who love and care about her when she needs it.

There's a romantic subplot in Will & Whit that follows Autumn and one of the theater kids, who ends up not being all he's cracked up to be. Autumn, who is Indian, chooses to change her appearance for him, even. But doing so left her alone in the end, and she discovers that embracing who she is -- as she is -- will snag her the sort of boyfriend she deserves. And, well, who happens to have been there all along. Will, too, will get a chance to have something romantic happen in her life, as well, and both instances work well in the story. They don't feel shoved in and they feel authentic.

In many ways, Will & Whit reminds me of Drama by Raina Telgemeier and I think they'd make good read alikes. Gulledge's story is a little bit more mature, though I wouldn't hesitate to hand it to a middle school reader who was ready for an older story. Both books are about creative kids and about how embracing that creativity matters. Both encourage teens to be happy with who they are and to chase those things which matter to them. There are also some interesting comparisons to be drawn about the stage crew story -- being "in the back" of the show -- in Telgemeier's story and Will's knowledge of, experience with, and passion for lighting and the role that plays in getting the carnival going. Likewise, both books make their characters talk, interact, and look like the age group they're portraying. There is no doubt that Will is 17 and that her friends are all in that age group. Even Reese, who is Noel's 13-year-old sister, looks 13, as opposed to 17 like her brother and his friends.

I'd hoped for a little bit more of a relationship to be seen between Will and her aunt because I was

curious to know more about her aunt. Like Will, she, too, experienced a great amount of loss in a short time. Perhaps it's the description Will gives of Ella at the beginning of the book which captured me most about Ella and which is something I'd personally aspire to be: quietly badass (this is as profane as the story gets). Why there isn't more of a relationship ultimately makes sense, though: Will has tried to be the strong one for both of them, and as such, she hasn't allowed herself to let Ella in. I suspect that after this story's close, their relationship becomes what I'd hoped to see, and I can settle for that.

Gulledge's art is fun and her characters are bold. Her people stand out in every scene, but it's never at the expense of the scene around them. Because this is a story about people and not things, it's important that they do stand on their own.

I appreciated the black and white only method here, particularly because it plays well into the story itself, about darkness and light, about power being on and then being lost. About storms that come and shake things up and then leave you to pick up the pieces. The black and white illustrations are not boring; they're perhaps as bright and powerful as possible throughout. The use of shadows swirling behind Will are at times loud and at other times soft and subtle. It mirrors her feelings and how she interacts with and allows herself to have them. When the power goes off, the book goes much darker, as well -- and as Will explained at the start of the story, the third thing you need to know about her is that she is afraid of the dark. It's when she cannot suppress the shadows any more. It's when she cannot control the light because it is out of her control. It's smart stuff.

It's worth checking out the tumblr that Gulledge has going for Will & Whit. Pass this along to artsy readers who enjoy graphic novels and those who like graphic novels that are stand alones. I think Gulledge's book is also a great pick for readers who are more reluctant to try a graphic novel. It's a very nice introduction to the format.

Will & Whit is available now. Copy borrowed from my library.

Related StoriesNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangTwitterview: Sara Varon & Cecil Castellucci

Related StoriesNovel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading ListBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangTwitterview: Sara Varon & Cecil Castellucci

Published on August 08, 2013 22:00

August 7, 2013

Novel/Graphic Novel Hybrids: A Reading List

I don't think it's necessarily a trend in young adult fiction, but I've noticed recently more traditional novels are featuring graphic novel elements to them. Interspersed within the text are illustrations that either help tell the story or add an additional element to the storytelling (and sometimes both at once). Since getting new readers into graphic novels can be challenging, these illustrated/hybrid novels might be a way to encourage trying another method of storytelling. Likewise, these can be great books for those readers who are the opposite -- adding the graphic element to a traditional novel can persuade those who are heavy graphic novel readers to try more "traditional" novels.

Maybe most importantly, though, these books are fun. They offer new ways into stories, and work toward building and enhancing curiosity. Why did this particular scene get an illustration? What significance does this particular image mean? Is it telling the reader something visually that cannot possibly be expressed through written words? Is the character telling the story an artist him or herself and the graphic elements are "their" creations and not the work of the author/illustrator?

Here is a handful of these hybrid novels, including a couple that aren't out yet but will be coming out soon. If you know of other books that fit this category, we'd love to know about them in the comments. There's no restriction on when the books came out because this is a smaller range of books than most. As long as it's young adult and traditionally published, we want to know about them. Note that these books feature illustrations, too -- they aren't books including photographs, letters, or other ephemeral items (which is why books like Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children are not included).

All descriptions come from WorldCat unless otherwise noted.

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, with illustrations by Ellen Forney: Budding cartoonist Junior leaves his troubled school on the Spokane Indian Reservation to attend an all-white farm town school where the only other Indian is the school mascot.

Year of the Beasts by Cecil Castellucci and Nate Powell: Fifteen-year-old Tessa tries to be happy when her crush, Charlie, falls for her younger sister, Lulu, and it becomes easier after she begins a secret relationship with Jasper, a social outcast who lives next door to Tessa's best friend.

Wanderlove by Kirsten Hubbard (illustrations by Hubbard): Bria, an aspiring artist just graduated from high school, takes off for Central America's La Ruta Maya, rediscovering her talents and finding love.

Winger by Andrew Smith (illustrations by Smith): Two years younger than his classmates at a prestigious boarding school, fourteen-year-old Ryan Dean West grapples with living in the dorm for troublemakers, falling for his female best friend who thinks of him as just a kid, and playing wing on the Varsity rugby team with some of his frightening new dorm-mates.

A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness: Thirteen-year-old Conor awakens one night to find a monster outside his bedroom window, but not the one from the recurring nightmare that began when his mother became ill--an ancient, wild creature that wants him to face truth and loss.

Leviathan by Scott Westerfeld, illustrated by Keith Thompson: In an alternate 1914 Europe, fifteen-year-old Austrian Prince Alek, on the run from the Clanker Powers who are attempting to take over the globe using mechanical machinery, forms an uneasy alliance with Deryn who, disguised as a boy to join the British Air Service, is learning to fly genetically engineered beasts.

Lips Touch Three Times by Laini Taylor, with illustrations by Jim Di Bartolo: Three short stories about kissing, featuring elements of the supernatural.

Maggot Moon by Sally Gardner, with illustrations by Julian Crouch: An unlikely teenager risks all to expose the truth about a heralded moon landing. What if the football hadn't gone over the wall. On the other side of the wall there is a dark secret. And the devil. And the Moon Man. And the Motherland doesn't want anyone to know. But Standish Treadwell--who has different-colored eyes, who can't read, can't write, Standish Treadwell isn't bright--sees things differently than the rest of the "train-track thinkers." So when Standish and his only friend and neighbor, Hector, make their way to the other side of the wall, they see what the Motherland has been hiding. And it's big.

Broken by Elizabeth Pulford, with illustrations by Angus Gomes (available August 27): Zara has one immediate and urgent goal, and it is to find her brother, Jem. She faces a few complications, though, not the least of which is searching for him in her subconscious while she is in a coma. Zara’s coma has pulled her into the world of Jem’s favorite comic-book hero. But no matter how quickly Zara literally draws her own escape, she is taunted deeper into the fantastical darkness by the comic’s villain, Morven. All the while she is caught between the present with visits from friends and family in the hospital and the past by flashbacks of a traumatic event long ago forgotten.

The search for her brother may help Zara see the light, but in order to find him, she must face her innermost secrets first. (Description via Goodreads).

Chasing Shadows by Swati Avasthi, with illustrations by Craig Phillips (available September 24): Before: Corey, Holly, and Savitri are one unit—fast, strong, inseparable. Together they turn Chicago concrete and asphalt into a freerunner’s jungle gym, ricocheting off walls, scaling buildings, leaping from rooftops to rooftop. But acting like a superhero doesn’t make you bulletproof. After: Holly and Savitri are coming unglued. Holly says she’s chasing Corey’s killer, chasing revenge. Savitri fears Holly’s just running wild—and leaving her behind. Friends should stand by each other in times of crisis. But can you hold on too tight? Too long? In this intense novel, Swati Avasthi creates a gripping portrait of two girls teetering on the edge of grief and insanity. Two girls who will find out just how many ways there are to lose a friend…and how many ways to be lost. (Description via Goodreads).

The Well's End by Seth Fishman, illustrated by Kate Beaton (February 25, 2014): Mia Kish is afraid of the dark. And for good reason. When she was a toddler she fell deep into her backyard well only to be rescued to great fanfare and celebrity. In fact, she is small-town Fenton,Colorado’s walking claim to fame. Not like that helps her status at Westbrook Academy, the nearby uber-ritzy boarding school she attends. A townie is a townie. Being nationally ranked as a swimmer doesn’t matter a lick. But even the rarefied world of Westbrook is threated when emergency sirens start blaring and the school is put on lockdown, quarantined and surrounded by soldiers who seem to shoot first and ask questions later. Only when confronted by a frightening virus that ages its victims to death in a manner of hours does Mia realize she may only just be beginning to discover what makes Fenton special. The answer is behind the walls of the Cave, aka Fenton Electronics. Mia’s dad, the director of Fenton Electronics, has always been secretive about his work. But unless Mia is willing to let her classmates succumb to the strange illness, she and her friends have got to break quarantine, escape the school grounds, and outsmart armed soldiers to uncover the truth about where the virus comes from and what happened down that well. The answers they find just might be more impossible than the virus they are fleeing.

If you're curious about a sneak peek at the Fishman book, there's a nice piece with illustrations over at io9.

A few middle grade authors to have in your back pocket who have done these sorts of books include Neil Gaiman (though Coraline and The Graveyard Book), Philip Reeve (Larklight), Brian Selznick (Wonderstruck), and Tony DiTerlizzi (The Search for WondLa).

Related StoriesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangTwitterview: Sara Varon & Cecil CastellucciGet Genrefied*: Graphic Novels

Related StoriesBoxers & Saints by Gene Luen YangTwitterview: Sara Varon & Cecil CastellucciGet Genrefied*: Graphic Novels