Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 129

November 11, 2013

Contemporary YA Books Featuring Mental Illness

Mental illness and mental well-being are topics that keep emerging in contemporary YA, and they keep being explored in worthwhile -- even life-changing -- ways. This list features very recent contemporary YA titles that have tackled mental illness in some capacity.

All of these titles were published in the last two years, though many, many more titles have come before and many more will come after. This isn't an exhaustive list, but rather one meant to show a range of experiences. Some of the descriptions aren't entirely insightful as to what the mental illness tackled is, and sometimes that's purposeful (The Stone Girl, for example, highlights the eating disorder but there is most definitely a mental illness coexisting with it).

If you have other favorite contemporary realistic YA titles that tackle mental illness and mental well-being from any period of time, feel free to leave the title and author in the comments. And yes, you may borrow and share this list as you see fit.

Descriptions are from WorldCat, unless otherwise noted.

Wild Awake by Hilary T. Smith: The discovery of a startling family secret leads seventeen-year-old Kiri Byrd from a protected and naive life into a summer of mental illness, first love, and profound self-discovery.

Opposite of Hallelujah by Anna Jarzab: For eight of her sixteen years Carolina Mitchell's older sister Hannah has been a nun in a convent, almost completely out of touch with her family--so when she suddenly abandons her vocation and comes home, nobody knows quite how to handle the situation, or guesses what explosive secrets she is hiding.

Something Like Normal by Trish Doller: When Travis returns home from Afghanistan, his parents are splitting up, his brother has stolen his girlfriend and car, and he has nightmares of his best friend getting killed but when he runs into Harper, a girl who has despised him since middle school, life actually starts looking up.

Charm & Strange by Stephanie Kuehn: A lonely teenager exiled to a remote Vermont boarding school in the wake of a family tragedy must either surrender his sanity to the wild wolves inside his mind or learn that surviving means more than not dying.

Crash and Burn by Michael Hassan: Steven "Crash" Crashinsky relates his sordid ten-year relationship with David "Burn" Burnett, the boy he stopped from taking their high school hostage at gunpoint.

Drowning Instinct by Ilsa J. Bick: An emotionally damaged sixteen-year-old girl begins a relationship with a deeply troubled older man.

Crazy by Amy Reed: Connor and Izzy, two teens who met at a summer art camp in the Pacific Northwest where they were counsellors, share a series of emails in which they confide in one another, eventally causing Connor to become worried when he realizes that Izzy's emotional highs and lows are too extreme.

Dr. Bird's Advice for Sad Poets by Evan Roskos: A sixteen-year-old boy wrestling with depression and anxiety tries to cope by writing poems, reciting Walt Whitman, hugging trees, and figuring out why his sister has been kicked out of the house.

Zoe Letting Go by Nora Price: Zoe goes to a facility to help cure her anorexia as she comes to terms with the loss of her friend and her own identity.

Bruised by Sarah Skilton: When she freezes during a hold-up at the local diner, sixteen-year-old Imogen, a black belt in Tae Kwan Do, has to rebuild her life, including her relationship with her family and with the boy who was with her during the shoot-out.

Perfect Escape by Jennifer Brown: Seventeen-year-old Kendra, living in the shadow of her brother's obsessive-compulsive disorder, takes a life-changing road trip with him.

This is Not A Drill by Beck McDowell: Two teens try to save a class of first-graders from a gun-wielding soldier suffering from PTSD. When high school seniors Emery and Jake are taken hostage in the classroom where they tutor, they must work together to calm both the terrified children and the psychotic gunman threatening them--a task made even more difficult by their recent break-up. Brian Stutts, a soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after serving in Iraq, uses deadly force when he's denied access to his son because of a custody battle. The children's fate is in the hands of the two teens, each recovering from great loss, who now must reestablish trust in a relationship damaged by betrayal. Told through Emery and Jake's alternating viewpoints, this gripping novel features characters teens will identify with and explores the often-hidden damages of war.

Chasing Shadows by Swati Avasthi: Chasing Shadows is a searing look at the impact of one random act of violence. Before: Corey, Holly, and Savitri are one unit-- fast, strong, inseparable. Together they turn Chicago concrete and asphalt into a freerunner's jungle gym, ricocheting off walls, scaling buildings, leaping from rooftop to rooftop. But acting like a superhero doesn't make you bulletproof. After: Holly and Savitri are coming unglued. Holly says she's chasing Corey's killer, chasing revenge. Savitri fears Holly's just running wild-- and leaving her behind. Friends should stand by each other in times of crisis. But can you hold on too tight? Too long? In this intense novel, told in two voices, and incorporating comic-style art sections, Swati Avasthi creates a gripping portrait of two girls teetering on the edge of grief and insanity. Two girls who will find out just how many ways there are to lose a friend-- and how many ways to be lost.

The Girls of No Return by Erin Saldin: A troubled sixteen-year-old girl attending a wilderness school in the Idaho mountains must finally face the consequences of her complicated friendships with two of the other girls at the school.

OCD Love Story by Corey Ann Haydu: In an instant, Bea felt almost normal with Beck, and as if she could fall in love again, but things change when the psychotherapist who has been helping her deal with past romantic relationships puts her in a group with Beck--a group for teens with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Cracked by K. M. Walton: When Bull Mastrick and Victor Konig wind up in the same psychiatric ward at age sixteen, each recalls and relates in group therapy the bullying relationship they have had since kindergarten, but also facts about themselves and their families that reveal they have much in common.

Freaks Like Us by Susan Vaught: A mentally ill teenager who rides the "short bus" to school investigates the sudden disappearance of his best friend.

Lexapros and Cons by Aaron Karo: Realizing that his OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) is out of control, seventeen-year-old Chuck Taylor, who wants to win his best friend back and impress a new girl at school, tries to break some hardcore habits, face his demons--and get messy.

Forgive Me, Leonard Peacock by Matthew Quick: A day in the life of a suicidal teen boy saying good-bye to the four people who matter most to him.

Pretty Girl-13 by Liz Coley: Sixteen-year-old Angie finds herself in her neighborhood with no recollection of her abduction or the three years that have passed since, until alternate personalities start telling her their stories through letters and recordings.

The Stone Girl by Alyssa Sheinmel: Seventeen-year-old Sethie, a senior at New York City's Franklin White girl's school, has outstanding grades, a boyfriend, and a new best friend but constantly struggles to lose weight.

Related StoriesMental Illness in Contemporary YA: Guest Post from Hilary T. Smith (author of Wild Awake)Contemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: Steampunk

Related StoriesMental Illness in Contemporary YA: Guest Post from Hilary T. Smith (author of Wild Awake)Contemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: Steampunk

Published on November 11, 2013 10:00

November 10, 2013

Mental Illness in Contemporary YA: Guest Post from Hilary T. Smith (author of Wild Awake)

Let's kick off contemporary week with Hilary T. Smith's post about the importance of good, solid, realistic fiction about mental illness.

Hilary Smith is the author of the novel WILD AWAKE and of this semi-defunct blog. She lives in Portland, OR, where she is studying North Indian classical music and doing her best to keep the neighbors from having her spaceship van towed.

Burn the Pamphlet, Wrestle With the Bear: Mental Health Narratives and YA Literature

Our cultural scripts for mental illness are pretty uninspiring. The suicide pamphlet in the school nurse's office advises you to Get Help and Speak to a Counselor, where "help" is often a code word for "life-long medication," and the counselor might be the wise healer of your dreams, or might be a not-very-wise adult who hands you another stupid pamphlet and sends you on your way. If you weren't so busy being outlandishly sad or paranoid or hyper, you would be tempted to shout: "People! I am going through what may prove to be one of the most potent and devastating experiences of my life, and you want me to read a fucking pamphlet?"

In a cool culture, they'd send you into the forest to wrestle a grizzly bear, or everyone in your village would surround you in an all-night evil-spirit-dispelling drum circle dance, or they would give you a nice old Pippi Longstocking house on a leafy street where you could live in a way that worked for your brain and didn't bother anyone.

Anyone who has been on the receiving end of the suicide pamphlet (or the OCD pamphlet or the psychosis pamphlet) can tell you that when it comes to talking about mental illness, our culture has a terrifyingly limited vocabulary. We tiptoe. We oversimplify. We squawk the same Top Ten Tips over and over like parrots in a cage.

The conversation about mental illness has become completely jammed up by this squawking, and it's going to take a lot of smart, inquisitive, and imaginative people to unjam it.

This is where YA comes in. Many of those potential conversation-changing people are kids and teens right now. One of the exciting things that YA literature can do is provoke teens to question different elements of their culture—whether you're talking about politics, gender stuff, or reality TV. Why should mental health be excluded from that kind of questioning?

One thing I love about YA right now is that so many books have moved past the "issue-addressing" narratives of previous decades and are delving into the messiness and complexity of experiences like mental illness not as "issues" to be "resolved" but as part of a larger story. What is the difference between an "issue novel" and a novel-novel, and why is this difference important?

In an issue novel, the Problem is shown to be a certain situation or behavior (teen drinking! disordered eating! manic escapades!) which is shown to cause Conflicts that result in Consequences. The conflicts and consequences surrounding this single situation or behavior are the main drivers of plot and character; the story is over when the situation has been defused and/or the behavior modified. A novel-novel might also involve a problematic situation or behavior which creates conflicts and consequences, but the Problem is shown to be something greater than that choice or behavior. The Problem might be free will, or social justice, or alienation, or finding one's place in the world—but whatever it is, it takes place in a much larger context in which the "problematic situation or behavior" forms a small piece. With that in mind, the plot might not hinge on the situation or behavior or at all—it might simply be taken as part of the background.

In an issue novel, the Problem is shown to be a certain situation or behavior (teen drinking! disordered eating! manic escapades!) which is shown to cause Conflicts that result in Consequences. The conflicts and consequences surrounding this single situation or behavior are the main drivers of plot and character; the story is over when the situation has been defused and/or the behavior modified. A novel-novel might also involve a problematic situation or behavior which creates conflicts and consequences, but the Problem is shown to be something greater than that choice or behavior. The Problem might be free will, or social justice, or alienation, or finding one's place in the world—but whatever it is, it takes place in a much larger context in which the "problematic situation or behavior" forms a small piece. With that in mind, the plot might not hinge on the situation or behavior or at all—it might simply be taken as part of the background.

If The Catcher In The Rye was an issue novel, we might see Holden Caulfield receiving counseling for the death of his brother, getting help for his drinking habit, making up with his parents, and going back to school.

If Wonder When You'll Miss Me was an issue novel, the story would most almost certaintly revolve around the protagonist "coming to terms" with her highschool tormentor instead of hitting him in the head with an axe and running away to join the circus with her imaginary twin.

If Wonder When You'll Miss Me was an issue novel, the story would most almost certaintly revolve around the protagonist "coming to terms" with her highschool tormentor instead of hitting him in the head with an axe and running away to join the circus with her imaginary twin.

In Dante and Aristotle Discover the Secrets of the Universe, the teenaged characters drive into the desert to smoke pot. In a lesser version of the story, the pot smoking would be discovered and addressed and Made Into An Issue; luckily for the reader, Benamin Alire Saenz allows it to simply be a beautiful and believable part of the story.

So how do we write YA novels involving mental illness without turning them into issue novels? First, ask yourself if a given behavior or situation really needs to be treated as an "issue" at all (with all the capital-r Resolutions that this entails). Is mental illness really the main source of conflict in the story? Or can mental illness be part of a story about love, or freedom, or intergalactic space wars? Do you need to "Resolve" it in a dramatic way? Or can you treat it like Dante and Aristotle's illicit toking in the desert?

As a YA writer, you are quite literally affecting the range of stories teen can access about mental illness. Are you going to hand them another pamphlet, or send them to wrestle with the bear?

***

Hilary has offered up a signed copy of Wild Awake to one winner. Enter below and I'll draw a name at the end of the month.

Loading...

Related StoriesContemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!

Related StoriesContemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!

Hilary Smith is the author of the novel WILD AWAKE and of this semi-defunct blog. She lives in Portland, OR, where she is studying North Indian classical music and doing her best to keep the neighbors from having her spaceship van towed.

Burn the Pamphlet, Wrestle With the Bear: Mental Health Narratives and YA Literature

Our cultural scripts for mental illness are pretty uninspiring. The suicide pamphlet in the school nurse's office advises you to Get Help and Speak to a Counselor, where "help" is often a code word for "life-long medication," and the counselor might be the wise healer of your dreams, or might be a not-very-wise adult who hands you another stupid pamphlet and sends you on your way. If you weren't so busy being outlandishly sad or paranoid or hyper, you would be tempted to shout: "People! I am going through what may prove to be one of the most potent and devastating experiences of my life, and you want me to read a fucking pamphlet?"

In a cool culture, they'd send you into the forest to wrestle a grizzly bear, or everyone in your village would surround you in an all-night evil-spirit-dispelling drum circle dance, or they would give you a nice old Pippi Longstocking house on a leafy street where you could live in a way that worked for your brain and didn't bother anyone.

Anyone who has been on the receiving end of the suicide pamphlet (or the OCD pamphlet or the psychosis pamphlet) can tell you that when it comes to talking about mental illness, our culture has a terrifyingly limited vocabulary. We tiptoe. We oversimplify. We squawk the same Top Ten Tips over and over like parrots in a cage.

The conversation about mental illness has become completely jammed up by this squawking, and it's going to take a lot of smart, inquisitive, and imaginative people to unjam it.

This is where YA comes in. Many of those potential conversation-changing people are kids and teens right now. One of the exciting things that YA literature can do is provoke teens to question different elements of their culture—whether you're talking about politics, gender stuff, or reality TV. Why should mental health be excluded from that kind of questioning?

One thing I love about YA right now is that so many books have moved past the "issue-addressing" narratives of previous decades and are delving into the messiness and complexity of experiences like mental illness not as "issues" to be "resolved" but as part of a larger story. What is the difference between an "issue novel" and a novel-novel, and why is this difference important?

In an issue novel, the Problem is shown to be a certain situation or behavior (teen drinking! disordered eating! manic escapades!) which is shown to cause Conflicts that result in Consequences. The conflicts and consequences surrounding this single situation or behavior are the main drivers of plot and character; the story is over when the situation has been defused and/or the behavior modified. A novel-novel might also involve a problematic situation or behavior which creates conflicts and consequences, but the Problem is shown to be something greater than that choice or behavior. The Problem might be free will, or social justice, or alienation, or finding one's place in the world—but whatever it is, it takes place in a much larger context in which the "problematic situation or behavior" forms a small piece. With that in mind, the plot might not hinge on the situation or behavior or at all—it might simply be taken as part of the background.

In an issue novel, the Problem is shown to be a certain situation or behavior (teen drinking! disordered eating! manic escapades!) which is shown to cause Conflicts that result in Consequences. The conflicts and consequences surrounding this single situation or behavior are the main drivers of plot and character; the story is over when the situation has been defused and/or the behavior modified. A novel-novel might also involve a problematic situation or behavior which creates conflicts and consequences, but the Problem is shown to be something greater than that choice or behavior. The Problem might be free will, or social justice, or alienation, or finding one's place in the world—but whatever it is, it takes place in a much larger context in which the "problematic situation or behavior" forms a small piece. With that in mind, the plot might not hinge on the situation or behavior or at all—it might simply be taken as part of the background.

If The Catcher In The Rye was an issue novel, we might see Holden Caulfield receiving counseling for the death of his brother, getting help for his drinking habit, making up with his parents, and going back to school.

If Wonder When You'll Miss Me was an issue novel, the story would most almost certaintly revolve around the protagonist "coming to terms" with her highschool tormentor instead of hitting him in the head with an axe and running away to join the circus with her imaginary twin.

If Wonder When You'll Miss Me was an issue novel, the story would most almost certaintly revolve around the protagonist "coming to terms" with her highschool tormentor instead of hitting him in the head with an axe and running away to join the circus with her imaginary twin.

In Dante and Aristotle Discover the Secrets of the Universe, the teenaged characters drive into the desert to smoke pot. In a lesser version of the story, the pot smoking would be discovered and addressed and Made Into An Issue; luckily for the reader, Benamin Alire Saenz allows it to simply be a beautiful and believable part of the story.

So how do we write YA novels involving mental illness without turning them into issue novels? First, ask yourself if a given behavior or situation really needs to be treated as an "issue" at all (with all the capital-r Resolutions that this entails). Is mental illness really the main source of conflict in the story? Or can mental illness be part of a story about love, or freedom, or intergalactic space wars? Do you need to "Resolve" it in a dramatic way? Or can you treat it like Dante and Aristotle's illicit toking in the desert?

As a YA writer, you are quite literally affecting the range of stories teen can access about mental illness. Are you going to hand them another pamphlet, or send them to wrestle with the bear?

***

Hilary has offered up a signed copy of Wild Awake to one winner. Enter below and I'll draw a name at the end of the month.

Loading...

Related StoriesContemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!

Related StoriesContemporary YA Week @ STACKEDGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!

Published on November 10, 2013 22:00

November 9, 2013

Contemporary YA Week @ STACKED

Welcome to the third annual contemporary YA fiction week here at STACKED. I am so, so excited to get this week kicked off because there is so much great stuff to share.

Like in years past, I have a nice array of guest posts from contemporary YA authors. We're going to travel across the globe to talk about Australian contemporary YA, we'll talk about mental illness and contemporary YA, humor in contemporary YA, and much, much more. In fact, I have 7 guest posts lined up, along with a host of book lists.

After seeing what people were interested in reading about earlier this year, I noticed some of the topics that were mentioned were topics that have been covered here before -- either during a prior contemporary week or elsewhere. I thought that in addition to new posts, I'd rerun some older content, as well, in order to give a huge range of voices and insights into contemporary YA.

So in short, contemporary YA week will be a little longer than one week this year. It'll be closer to a week and a half long, with two posts a day. I promise a lot of worthwhile reading, thought-provoking guest posts, and, I hope, useful book lists of titles within a given topic and titles to get on your radar for the coming year.

And perhaps -- just perhaps -- I'll tell you a little bit more about my book about contemporary YA sometime at the end of this series.

Contemporary YA fiction week will start tomorrow with a guest post about mental illness as it's depicted in YA, with a sharp take on the idea of "the problem novel."

Related StoriesGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2

Related StoriesGet (sub)Genrefied: SteampunkA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2

Published on November 09, 2013 22:00

November 7, 2013

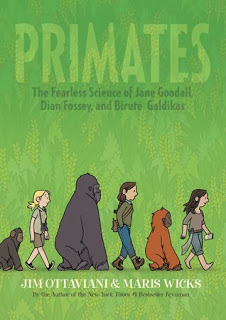

Primates by Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks

Primates is a nonfiction gem. Ottaviani and Wicks tell the interlocking stories of three female scientists who did groundbreaking research with primates: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas. All three women lived with the primates they studied (chimps, gorillas, and orangutans, respectively), and all three made significant contributions to their fields.

Of particular interest is the fact that they were all able to do their work because of their association with noted male scientist Louis Leakey - the three women were all dubbed "Leakey's Angels" as a result. Leakey believed women were uniquely qualified for this type of research, and he was able to secure the funding to make it happen. There's certainly an element of frustration knowing that brilliant female scientists needed another male scientist to make it possible for them to do their work.

I also found it interesting that two of the three women (Goodall and Fossey) actively eschewed traditional education (by this I mainly mean advanced college degrees), finding it unnecessary and even counterproductive. It's only the third and youngest, Galdikas, who was already pursuing an advanced degree when she met Leakey, several years after Goodall and Fossey had begun their research with him. I can't help but feel that the distaste for a degree has a lot to do with the traditional maleness of it as well as the very hands-off nature of such things, which didn't appeal to these scientists who literally lived alongside their subjects.

This is the kind of book that inspires the reader to find out more about the subjects after the last page is turned. In so doing, I discovered that Ottaviani and Wicks significantly glossed over Fossey's death - they refer to it, but make no mention of the fact she was murdered, the case still unsolved today (mostly). It's not an exhaustive biography. Ottaviani mentions in the author's note that the book is a hybrid of fiction and nonfiction - he had to fill in the gaps and speculate at some points. It's told in first person, with Goodall narrating the first part, Fossey the second, and Galdikas the third. All three scientists narrate the last few pages, their voices intermingling. During this section, we get some idea of what they thought of each other, which I found very interesting. While the handwriting is different for each scientist, I did find it a bit difficult to distinguish who was narrating at times.

It's in full-color, eye-catching and gorgeous. I'm so glad it is; it would be a travesty not to see the fantastic nature scenes depicted in all their glory. The three women look distinct from each other, and each is easily identifiable in a real-life photograph at the end of the book. This is excellent nonfiction with high appeal. I was amazed at what these women did, and I loved knowing that two of them continue to do amazing work today. I think this fact will make it seem relevant to kids - especially girls - who love science and animals, and it may inspire them to think of doing something like this themselves one day.

I never thought I'd find primates so fascinating. I still don't think I really do. But the scientists? Definitely so.

Copy borrowed from the library.

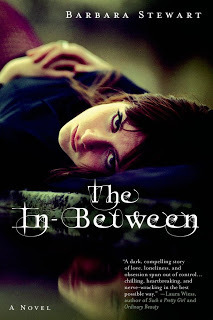

Related StoriesThe In-Between by Barbara StewartAudiobook Review: The Waking Dark by Robin WassermanJuvie by Steve Watkins

Related StoriesThe In-Between by Barbara StewartAudiobook Review: The Waking Dark by Robin WassermanJuvie by Steve Watkins

Published on November 07, 2013 22:00

November 6, 2013

Get (sub)Genrefied: Steampunk

Every month, we're highlighting one genre within YA fiction as part of Angela's reader's advisory challenge. So far, we've discussed horror, science fiction, high fantasy, mysteries and thrillers, verse novels, contemporary realistic fiction, historical fiction, graphic novels, romances, and dystopias. November's focus is another subgenre: steampunk.

Steampunk is not a subgenre either of us are very familiar with, but I know I've enjoyed getting to know it a bit more for this guide. So what exactly is steampunk? It's a subgenre of science fiction, and its primary characteristic is that it features steam-powered machines, often anachronistically. What this means is that steampunk stories may include complex steam-powered contraptions in a time (such as the 19th century) when the technology for such things never existed (making it alternate history). They also often feature this type of technology in a future world, making the stories a fun combination of futuristic and retro. The "classic" steampunk story is also culturally Western, frequently Victorian-era British.

(I will say that the machines I've found in books described as steampunk aren't always steam-powered. For a different sort of definition, take this one from the Steampunk Bible: a grafting of Victorian aesthetic and punk rock attitude onto various forms of science-fiction culture. As with other genres and subgenres, people define it in different ways.)

Like other genre fiction, there's lots of genre-blending that goes on. You'll find steampunk crossed with historical fiction, romance, mystery, fantasy, horror, and others. It's part of what makes reading genre fiction such an adventure - the possibilities are endless.

Perhaps more so than other genres and subgenres, steampunk has lent itself to an entire culture beyond the books. People dress up in steampunk costumes and wear steampunk jewelry. Often, they'll make their own. Fans make and sell steampunk art. Shops have sprung up online to sell these items to buyers all over. I've noticed that most of those passionate about steampunk tend to be adults - but I don't doubt that there are many avid teen fans as well.

Below are a few resources if you'd like to learn more about the subgenre (from people more knowledgeable about it than me, no doubt!):

The aforementioned Steampunk Bible by Jeff VanderMeer is the book to get if you're interested in diving headlong into the genre/culture. The Ranting Dragon gives us 20 Must-Read Steampunk Books in an article from 2011 (including YA titles) as well as a good, concise definition.AbeBooks discusses the history of the subgenre and offers more reading recommendations in their Steampunk 101 article.In a 2010 article, Library Journal offers up 20 core steampunk titles, including classics as well as more recent works. The New York Public Library recently wrote this fantastic piece about steampunk for teens, including a reading list. Steamed is the collaborative blog of a group of steampunk writers, and it's full of information. Posts include Steampunk for Beginners, Women in Steampunk, and Beyond Steampunk. They also run Steampunkapalooza, a yearly celebration of all things steampunk.As part of Steampunkapalooza this year, Teen Librarian Toolbox collected some excellent craft ideas plus rounded up links to other good content.Because this is a smaller subgenre without as many recent books to its name, I've broadened the list below to include notable titles older than five years. These titles, while older, should still be of interest to teens curious about the genre, especially since they've often influenced the more recent ones. Descriptions are from Worldcat. As always, please chime in if we've missed any.

Legacy of the Clockwork Key by Kristin Bailey: A orphaned sixteen-year-old servant in Victorian England finds love while unraveling the secrets of a mysterious society of inventors and their most dangerous creation.

Etiquette and Espionage and sequel by Gail Carriger: In an alternate England of 1851, spirited fourteen-year-old Sophronia is enrolled in a finishing school where, she is suprised to learn, lessons include not only the fine arts of dance, dress, and etiquette, but also diversion, deceit, and espionage.

Clockwork Angel and sequels by Cassandra Clare: When sixteen-year-old orphan Tessa Gray's older brother suddenly vanishes, her search for him leads her into Victorian-era London's dangerous supernatural underworld, and when she discovers that she herself is a Downworlder, she must learn to trust the demon-killing Shadowhunters if she ever wants to learn to control her powers and find her brother.

Riese: Kingdom Falling by Greg Cox: Riese has never been happy as a princess; she'd much rather be hunting or fighting than sitting through another lesson on court etiquette. When she meets Micah, a wandering artist with a mysterious past, she pretends to be a peasant--it's a chance to be just a normal girl with a normal boy for a while. But with war decimating her once-proud nation and the sinister clockwork Sect infiltrating her mother's court, Riese's moments with Micah are the only islands of sanity left in a world gone mad. As her kingdom falls and the Sect grows ever stronger, will Riese remain true to her duty as a princess...or risk everything on a boy she barely knows?

Girl in the Steel Corset and sequels by Kady Cross: Finley, who has a beastly alter ego inside of her, joins Duke Griffin's army of misfits to help stop the Machinist, the criminal behind a series of automaton crimes, from carrying out a plan to kill Queen Victoria during the Jubilee.

Incarceron and sequel by Catherine Fisher: To free herself from an upcoming arranged marriage, Claudia, the daughter of the Warden of Incarceron, a futuristic prison with a mind of its own, decides to help a young prisoner escape.

Worldshaker by Richard Harland: Sixteen-year-old Col Porpentine is being groomed as the next Commander of Worldshaker, a juggernaut where elite families live on the upper decks while the Filthies toil below, but when he meets Riff, a Filthy girl on the run, he discovers how ignorant he is of his home and its residents.

The Iron Thorn and sequels by Caitlin Kittredge: In an alternate 1950s, mechanically gifted fifteen-year-old Aoife Grayson, whose family has a history of going mad at sixteen, must leave the totalitarian city of Lovecraft and venture into the world of magic to solve the mystery of her brother's disappearance and the mysteries surrounding her father and the Land of Thorn.

The Friday Society by Adrienne Kress: Cora, Nellie, and Michiko, teenaged assistants to three powerful men in Edwardian London, meet by chance at a ball that ends with the discovery of a murdered man, leading the three to work together to solve this and related crimes without drawing undue attention to themselves.

Innocent Darkness and sequels by Suzanne Lazear: In 1901, on an alternate Earth, sixteen-year-old Noli rejoices when a mysterious man transports her from reform school to the Realm of Faerie, until Noli learns his sinister reason.

Steampunk! edited by Kelly Link: A collection of fourteen fantasy stories by well-known authors, set in the age of steam engines and featuring automatons, clockworks, calculating machines, and other marvels that never existed.

Railsea by China Mieville: On board the moletrain Medes, Sham Yes ap Soorap watches in awe as he witnesses his first moldywarpe hunt: the giant mole bursting from the earth, the harpoonists targeting their prey, the battle resulting in one's death & the other's glory. But no matter how spectacular it is, Sham can't shake the sense that there is more to life than traveling the endless rails of the railsea--even if his captain can think only of the hunt for the ivory-colored mole she's been chasing since it took her arm all those years ago.

Airborn and sequels by Kenneth Oppel: Matt, a young cabin boy aboard an airship, and Kate, a wealthy young girl traveling with her chaperone, team up to search for the existence of mysterious winged creatures reportedly living hundreds of feet above the Earth's surface.

Steampunk Poe: Presents a collection of Poe's short stories and poems, including "The Tell-Tale Heart," "The Fall of the House of Usher," and "The Raven," accompanied by steampunk-inspired illustrations.

Fever Crumb by Philip Reeve: Foundling Fever Crumb has been raised as an engineer although females in the future London, England, are not believed capable of rational thought, but at age fourteen she leaves her sheltered world and begins to learn startling truths about her past while facing danger in the present.

Mortal Engines and sequels by Philip Reeve: In the distant future, when cities move about and consume smaller towns, a fifteen-year-old apprentice is pushed out of London by the man he most admires and must seek answers in the perilous Out-Country, aided by one girl and the memory of another.

The Hunchback Assignments and sequels by Arthur Slade: In Victorian London, fourteen-year-old Modo, a shape-changing hunchback, becomes a secret agent for the Permanent Association, which strives to protect the world from the evil machinations of the Clockwork Guild.

Corsets and Clockwork edited by Trisha Telep: Collects thirteen original stories set during the Victorian era, including tales of steam-powered machines, family secrets, and love.

Leviathan and sequels by Scott Westerfeld: In an alternate 1914 Europe, fifteen-year-old Austrian Prince Alek, on the run from the Clanker Powers who are attempting to take over the globe using mechanical machinery, forms an uneasy alliance with Deryn who, disguised as a boy to join the British Air Service, is learning to fly genetically engineered beasts.

Related StoriesA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1

Related StoriesA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1

Steampunk is not a subgenre either of us are very familiar with, but I know I've enjoyed getting to know it a bit more for this guide. So what exactly is steampunk? It's a subgenre of science fiction, and its primary characteristic is that it features steam-powered machines, often anachronistically. What this means is that steampunk stories may include complex steam-powered contraptions in a time (such as the 19th century) when the technology for such things never existed (making it alternate history). They also often feature this type of technology in a future world, making the stories a fun combination of futuristic and retro. The "classic" steampunk story is also culturally Western, frequently Victorian-era British.

(I will say that the machines I've found in books described as steampunk aren't always steam-powered. For a different sort of definition, take this one from the Steampunk Bible: a grafting of Victorian aesthetic and punk rock attitude onto various forms of science-fiction culture. As with other genres and subgenres, people define it in different ways.)

Like other genre fiction, there's lots of genre-blending that goes on. You'll find steampunk crossed with historical fiction, romance, mystery, fantasy, horror, and others. It's part of what makes reading genre fiction such an adventure - the possibilities are endless.

Perhaps more so than other genres and subgenres, steampunk has lent itself to an entire culture beyond the books. People dress up in steampunk costumes and wear steampunk jewelry. Often, they'll make their own. Fans make and sell steampunk art. Shops have sprung up online to sell these items to buyers all over. I've noticed that most of those passionate about steampunk tend to be adults - but I don't doubt that there are many avid teen fans as well.

Below are a few resources if you'd like to learn more about the subgenre (from people more knowledgeable about it than me, no doubt!):

The aforementioned Steampunk Bible by Jeff VanderMeer is the book to get if you're interested in diving headlong into the genre/culture. The Ranting Dragon gives us 20 Must-Read Steampunk Books in an article from 2011 (including YA titles) as well as a good, concise definition.AbeBooks discusses the history of the subgenre and offers more reading recommendations in their Steampunk 101 article.In a 2010 article, Library Journal offers up 20 core steampunk titles, including classics as well as more recent works. The New York Public Library recently wrote this fantastic piece about steampunk for teens, including a reading list. Steamed is the collaborative blog of a group of steampunk writers, and it's full of information. Posts include Steampunk for Beginners, Women in Steampunk, and Beyond Steampunk. They also run Steampunkapalooza, a yearly celebration of all things steampunk.As part of Steampunkapalooza this year, Teen Librarian Toolbox collected some excellent craft ideas plus rounded up links to other good content.Because this is a smaller subgenre without as many recent books to its name, I've broadened the list below to include notable titles older than five years. These titles, while older, should still be of interest to teens curious about the genre, especially since they've often influenced the more recent ones. Descriptions are from Worldcat. As always, please chime in if we've missed any.

Legacy of the Clockwork Key by Kristin Bailey: A orphaned sixteen-year-old servant in Victorian England finds love while unraveling the secrets of a mysterious society of inventors and their most dangerous creation.

Etiquette and Espionage and sequel by Gail Carriger: In an alternate England of 1851, spirited fourteen-year-old Sophronia is enrolled in a finishing school where, she is suprised to learn, lessons include not only the fine arts of dance, dress, and etiquette, but also diversion, deceit, and espionage.

Clockwork Angel and sequels by Cassandra Clare: When sixteen-year-old orphan Tessa Gray's older brother suddenly vanishes, her search for him leads her into Victorian-era London's dangerous supernatural underworld, and when she discovers that she herself is a Downworlder, she must learn to trust the demon-killing Shadowhunters if she ever wants to learn to control her powers and find her brother.

Riese: Kingdom Falling by Greg Cox: Riese has never been happy as a princess; she'd much rather be hunting or fighting than sitting through another lesson on court etiquette. When she meets Micah, a wandering artist with a mysterious past, she pretends to be a peasant--it's a chance to be just a normal girl with a normal boy for a while. But with war decimating her once-proud nation and the sinister clockwork Sect infiltrating her mother's court, Riese's moments with Micah are the only islands of sanity left in a world gone mad. As her kingdom falls and the Sect grows ever stronger, will Riese remain true to her duty as a princess...or risk everything on a boy she barely knows?

Girl in the Steel Corset and sequels by Kady Cross: Finley, who has a beastly alter ego inside of her, joins Duke Griffin's army of misfits to help stop the Machinist, the criminal behind a series of automaton crimes, from carrying out a plan to kill Queen Victoria during the Jubilee.

Incarceron and sequel by Catherine Fisher: To free herself from an upcoming arranged marriage, Claudia, the daughter of the Warden of Incarceron, a futuristic prison with a mind of its own, decides to help a young prisoner escape.

Worldshaker by Richard Harland: Sixteen-year-old Col Porpentine is being groomed as the next Commander of Worldshaker, a juggernaut where elite families live on the upper decks while the Filthies toil below, but when he meets Riff, a Filthy girl on the run, he discovers how ignorant he is of his home and its residents.

The Iron Thorn and sequels by Caitlin Kittredge: In an alternate 1950s, mechanically gifted fifteen-year-old Aoife Grayson, whose family has a history of going mad at sixteen, must leave the totalitarian city of Lovecraft and venture into the world of magic to solve the mystery of her brother's disappearance and the mysteries surrounding her father and the Land of Thorn.

The Friday Society by Adrienne Kress: Cora, Nellie, and Michiko, teenaged assistants to three powerful men in Edwardian London, meet by chance at a ball that ends with the discovery of a murdered man, leading the three to work together to solve this and related crimes without drawing undue attention to themselves.

Innocent Darkness and sequels by Suzanne Lazear: In 1901, on an alternate Earth, sixteen-year-old Noli rejoices when a mysterious man transports her from reform school to the Realm of Faerie, until Noli learns his sinister reason.

Steampunk! edited by Kelly Link: A collection of fourteen fantasy stories by well-known authors, set in the age of steam engines and featuring automatons, clockworks, calculating machines, and other marvels that never existed.

Railsea by China Mieville: On board the moletrain Medes, Sham Yes ap Soorap watches in awe as he witnesses his first moldywarpe hunt: the giant mole bursting from the earth, the harpoonists targeting their prey, the battle resulting in one's death & the other's glory. But no matter how spectacular it is, Sham can't shake the sense that there is more to life than traveling the endless rails of the railsea--even if his captain can think only of the hunt for the ivory-colored mole she's been chasing since it took her arm all those years ago.

Airborn and sequels by Kenneth Oppel: Matt, a young cabin boy aboard an airship, and Kate, a wealthy young girl traveling with her chaperone, team up to search for the existence of mysterious winged creatures reportedly living hundreds of feet above the Earth's surface.

Steampunk Poe: Presents a collection of Poe's short stories and poems, including "The Tell-Tale Heart," "The Fall of the House of Usher," and "The Raven," accompanied by steampunk-inspired illustrations.

Fever Crumb by Philip Reeve: Foundling Fever Crumb has been raised as an engineer although females in the future London, England, are not believed capable of rational thought, but at age fourteen she leaves her sheltered world and begins to learn startling truths about her past while facing danger in the present.

Mortal Engines and sequels by Philip Reeve: In the distant future, when cities move about and consume smaller towns, a fifteen-year-old apprentice is pushed out of London by the man he most admires and must seek answers in the perilous Out-Country, aided by one girl and the memory of another.

The Hunchback Assignments and sequels by Arthur Slade: In Victorian London, fourteen-year-old Modo, a shape-changing hunchback, becomes a secret agent for the Permanent Association, which strives to protect the world from the evil machinations of the Clockwork Guild.

Corsets and Clockwork edited by Trisha Telep: Collects thirteen original stories set during the Victorian era, including tales of steam-powered machines, family secrets, and love.

Leviathan and sequels by Scott Westerfeld: In an alternate 1914 Europe, fifteen-year-old Austrian Prince Alek, on the run from the Clanker Powers who are attempting to take over the globe using mechanical machinery, forms an uneasy alliance with Deryn who, disguised as a boy to join the British Air Service, is learning to fly genetically engineered beasts.

Related StoriesA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1

Related StoriesA Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1

Published on November 06, 2013 22:00

November 5, 2013

A Literary Development Company Talks With Us: Welcome CAKE!

Remember last week how I blogged about book packagers and literary development companies? And I had a lot of questions with no real answers?

After the post ran, Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton, the founders of CAKE Literary, got in touch with me and gave me the opportunity to ask some of those questions. Knowing how much the topic fascinated me, I couldn't say no -- and I thought readers who wanted to know some of the same things I did would find this of interest as well.

This post won't talk about how you get involved with the company. Rather, this is a look at their mission, why they decided to create a company, what their intentions are, how they plan on breaking into the market with diversity-focused titles, and it'll talk a bit about their first book -- published under the company -- called Dark Pointe. It is long, but I think it's really fascinating and quite thorough about their process.

What

are your backgrounds with publishing and the book/literary world more

broadly?

Sona Charaipotra:

I’ve worked as a journalist for more than a decade, first on-staff

at People

and

TeenPeople

magazines,

then freelance for places like the New

York Times,

MSN, Cosmopolitan,

ABC News and others. While doing that, for a long time, I was writing

screenplays -- I have a Masters in Dramatic Writing from NYU -- and

even had a few projects developed. My screenwriting background means

I’m definitely a plotter -- I’m a huge believer in three-act

structure. But I’ve also been writing fiction for a while, and

decided to get my MFA at the New School so I could really work on

honing craft and character. That’s where I met Dhonielle. These

days, in addition to working on books, I’m writing a lot about

them. In doing a column for Parade.com on teen and YA culture, I’ve

interviewed writers like Holly Black, Maggie Stiefvater and Rainbow

Rowell.

Dhonielle Clayton:

After I stopped teaching, I decided to get into publishing because

the one thing that drew me to secondary education was being able to

read and discuss books that I loved. So I worked at National

Geographic

in Washington, DC, in their children’s department, reviewing

non-fiction manuscripts aimed at children, as well as fiction series

with strong environmental themes aimed at school and library markets.

I did this while I was earning my first masters in Children’s

Literature. I joined SCBWI and started going to conferences and

learning all that I could about the market. After I finished that

degree, I knew I had to go to NYC if I wanted to really dig into the

publishing world, so I applied to The New School MFA program, where I

met Sona. I knew immediately that I wanted to intern for a NYC

publishing house or a literary agency. I moved to the city the summer

before the program started, crashed on one of my good friend’s

couches, and landed an internship working for Stephen Barbara at

Foundry Media. Working at Foundry Media is where I learned a lot

about the business. I also started attending all the readings in the

city that I could, and lurking around the NYC book scene in general.

What

made you decide to create a literary development company and what's

your vision for it?

SC:

I was a huge reader as kid -- books were my greatest

indulgence, and my mother always said that it was the one thing she’d

always let me buy, because it was money well-spent. The thing is, as

much as I loved to read, I never saw myself in the books I devoured

as a kid. There were no brown children to be found. These days,

reading to my daughter, who’s three, things aren’t all that

different. So I think it’s really important to bring diversity to

kid lit and teen fiction -- and to women’s fiction, too, because I

still don’t see that grown-up version of myself anywhere, really.

We’ve all got stories to tell. But the thing that really moved me

towards CAKE and literary development is the idea that while a book

can have a character of color at its center, it can still be an

entirely universal story. I see that in a lot of my own work, and in

Dhonielle’s, too.

Dhonielle

and I are definitely ideas people. We could work ceaselessly and

never be able to put out even a tenth of what we’re coming up with.

These are exciting, compelling stories -- worth telling -- and we

thought working with other writers would be a great way to get them

out there. To be clear, not every book we publish will have a black

or brown girl at its center. We’re focusing on meaningful diversity

-- layered in and relevant, but not the central thrust of the story.

These aren’t, “Oh, I’m Indian and so discriminated against”

types of tales. These are fresh, high concept stories where the

characters happen to be diverse. But we don’t shy away from what

race, class or ethnicity brings to the character, either. If it’s

relevant, it will be explored.

DC:

I have always been an avid reader. My father took me to the bookstore

every weekend. It was our Saturday routine. So I was a spoiled child

and received a brand new set of books every Saturday with the caveat

that I finished the ones I got the week prior. My childhood home was

full of books, and I gravitated towards the ones on my father’s

shelf -- Tolkien, Isaac Asimov, C.S. Lewis, and Frank Herbert. I

wanted to go through the wardrobe into Narnia or trample through

Middle Earth. However, no one who looked like me starred as the lead

in those stories (unless you wanted to be an orc, and nobody wants to

be one of those). After my masters at Hollins University, I knew I

had to do something about it. I started writing stories, and keeping

a journal of other ideas that I felt might enhance the genre. I knew

I would not be able to physically write all of these books, and I had

become loosely familiar with some packaged projects while completing

grad school papers.

When

I met Sona, our conversations kept circling back to seeing or not

seeing ourselves in books as kids. As an Indian-American, her plight

was worse than mine. I had never even met a fictional Indian kid in a

story myself. There are African-American children’s books. Due to

responsible parents, I had every one of them, but sometimes I felt

like I was reading the same story over and over again. The

conversations Sona and I had were the foundation for CAKE Literary,

and helped carve out the start of our mission.

We

want to present a different model of how diversity can be included in

children’s and teen books, and move away from the cultural tales

(e.g. grappling with one’s culture, race, ethnicity, historical

tales of slavery or other events that have “marked” a group,

etc). Don’t get me wrong, these narratives are important

cornerstones to the world of children’s and teen fiction. I

wouldn’t be who I am without them. They need to be published, read

and studied by children and teens. But after seeing Chiamanda

Adichie’s TED talk titled “The

Danger of a Single Story” ,

it crystallized the emotion I had had as a child: feeling trapped

inside one story related to my people. This sparked my fervor for

wanting to help transform the landscape of books for kids and teens.

I wanted to open up the single story that is often attached to

children of color, whether that be the legacy of slavery, the

Holocaust, life on the reservation, poverty, immigration, etc. I

wanted to give these children other stories, too: adventures to other

planets, girl drama at school, quests through foreign lands full of

magical beings, awkward first crushes. Sona and I felt like a

packaging company was the right vehicle to start developing projects

that have a new take on diversity, and model how all writers can

incorporate color into their novels.

What

does it mean to have a highly commercial novel that's also decidedly

literary (in other words, what sorts of books on the market now are

what you envision to be what your company aims to produce)?

SC:

There’s been so much talk about voice -- and that’s what we mean

here. It’s about creating work that’s very high concept -- you

get what the story is just in a line or two, then think, “Why

didn’t I think of that?” But we’re playing careful attention to

craft and voice. We’re a packager, but we want there to be nothing

slapdash about CAKE’s projects. We want them to be compellingly

readable, but we also want those specific lines to linger in your

mind long after you’ve finished the book. Fun fiction that stays

with you.

DC:

A book that is delicious and compulsively readable, but on a sentence

level is still beautiful. Many times commercial books are given flack

for being not well-written, but contain an amazing plot,

story-telling structure, or interesting characters. So books like Jay

Asher’s Thirteen

Reasons Why,

Lauren Oliver’s Delirium,

Lauren DeStefano’s The

Chemical Garden Trilogy,

and Jenny Han and Siobhan Vivian’s Burn

for Burn trilogy,

just to name a few. Sona and I want to create books that are smart,

contain beautiful storytelling in a very high concept idea -- with a

strong element of diversity.

What

is it about the MG, YA, and women's fiction markets that makes now a

time that companies like your own are emerging?

SC:

Everyone keeps talking about the YA boom. Of course it’s something

people want to capitalize on. And these days, so much of what we see

in teen fiction is what’s translating to television and film. It

makes sense, business-wise, to be in this market. But also, as I’ve

mentioned, there’s a stark lack of representation of certain types

of people in this market. There’s still the idea that books about

people of color don’t sell. And it’s because a lot of the books

we’ve seen before were very pedantic, very heavy-handed, with a

certain point to make and maybe an axe to grind. I think there’s

definitely a way to do diversity -- and I’m not talking about

shying away from the issues people of different races or orientations

or classes deal with -- but do it in a way that still makes it a

compelling, universal read. I think that’s what readers are looking

for -- that delicious story, but with people they recognize at the

center. Perhaps with a reflection of themselves at the center. That’s

something I never got as a kid, and I would have killed for it.

(Okay, maybe not killed...but you get my point!)

DC:

The MG, YA, and women’s fiction markets are HOT! Work created for

individuals who belong to these groups is dynamic, fresh, and

interesting. I can’t even tear myself away from those titles to

explore any other genres. There’s just too much to read. We want to

be part of that. Sona and I watch a lot of TV (alas, it is a my vice,

yet part of her career as a journalist), and we see the world of TV

slowly changing in terms of diversity, and we feel like books could

reflect this change as well. Who wouldn’t want to read a YA book

series like ABC Family’s Twisted,

The

Fosters, or

Switched

at Birth?

High-concept projects with meaningful diversity that create a

compulsive story. We want to add new elements to the market.

Your

focus is on diversity -- speak to that a bit and why you chose that

angle for CAKE? What does the market look like now and what do you

envision CAKE adding to it?

SC:

The scale is tipping. There’s still a long way to go, but these

days, there are more people of different creeds, colors, orientations

than ever in media -- in film, on TV, and hopefully now the push has

come in books. Yet there’s still consistently this talk of how

books with black girls on the cover won’t sell, how diversity isn’t

marketable. I think the idea is that color may alienate a white

reader. But it doesn’t have to. The key is to make the story

relatable, universal -- and un-put-down-able. That’s what we were

aiming for with DARK POINTE. The book centers on three very different

girls, one white, one Korean, and one black. And their races do play

into the character development and even plot, however, the story

doesn’t dwell on that. It’s own, fast-paced, compelling thing --

and there are elements about each of these girls that make them

relatable, no matter what your skin color. That’s what we’re

hoping to bring to CAKE projects -- stories you can’t not

read,

but with those layers of diversity hewn in. Make race, sexual

orientation, class relevant, but not the center of the story.

DC:

Sona and I are nothing if not meticulous, so before even stepping out

on this journey, we researched. Tons. We looked at all of the current

packagers in the YA and MG market, and read their books, interviews,

online information, etc. We spent a lot of time thinking about what

could/would make us different in this crowded market besides that

fact that we are underdogs without any of our own published books on

the shelf. There were so many reasons not to jump in, and there were

many people who told us not to: You

guys have no real experience in publishing.

Neither

of you have your own books out there yet.

Diversity

doesn’t sell well internationally.

But

then the heart of the company bubbled up naturally. We didn’t start

with diversity at the core from which we wrote DARK POINTE. It just

continued to come up over and over again. When we looked at the

novel, we realized the key was there. We envision that CAKE will add

solid titles to the market that open up new stories and provide a new

lens for thinking about diversity. It’s not a term to invoke guilt

or shame, but rather to inspire flavor. Everybody loves cake, and it

would be mighty boring if it only came in one flavor.

Going

off that, what is it that CAKE will be able to make happen that other

authors who have been writing diverse stories are less able to do?

SC:

CAKE -- like the other literary development companies out there -- is

all about the high-concept. That’s the big book with the big hook

-- the one with the concept that carries, the delicious read.

That’s what publishers want. The other element we’re adding here

is the component of diversity. We’re hoping -- and I think this

will be true -- that diversity will also be what publishers want in

the future. We think the time has come. The population is shifting.

Librarians and teachers are asking for them. Dhonielle can attest

from her background in a middle school library that children

themselves are asking for them. So combining these two elements --

high-concept and diversity -- is what makes our projects different.

It’s

about a big story with a fresh cast of characters from varied

backgrounds, with layers of storytelling. Essentially, what we’re

hoping is that what a publisher will see in a CAKE story, first and

foremost, is a delicious, irresistible page-turner they have to have.

And then they see all those other layers that add a lot of depth to

the work.

DC:

We don’t think other authors and aspiring writers who are writing

diverse stories can’t do what we’re doing. Authors like Sherman

Alexie, David Levithan, Jacqueline Woodson, and countless others,

have been adding wonderfully diverse titles to the canon for years.

They have done remarkable things for bringing diversity to the

children’s and teen book world. We believe that using the vehicle

of a literary packaging company may add an influx in the number of

titles published with diverse elements, and help shrink the gap a bit

faster. We’re just starting out, so we don’t think we’ll

balloon into a powerhouse like Alloy Entertainment, but if we did,

there would be more stories out there that featured all types of

children at a higher frequency than possible for a single author

writing one or two books per year. At least we hope so!

Talk

a bit about the first book to come from CAKE: Dark Pointe.

SC:

A fast-paced YA mystery in the vein of Pretty

Little Liars,

DARK

POINTE

digs beneath the practiced poise of a cutthroat Manhattan ballet

academy, where three young protagonists all fight for prima position

while navigating secrets, lies, and the pressure that comes with

being prodigies. Free-spirited new girl Giselle just wants to dance –

but the very act might kill her. Upper East Side-bred Bette lives in

the all-encompassing shadow of her ballet star sister, but the weight

of family expectations brings out a dangerous edge in her.

Perfectionist June forever stands in the wings as an understudy, but

now she’s willing to do whatever it takes – even push someone out

the way – to take the stage. In a world where every other dancer is

both friend and foe, the girls have formed the tenuous bond that

comes with being the best of the best. But when New York City Ballet

Conservatory newbie Giselle is cast as the lead in The

Nutcracker

– opposite Bette’s longtime love Alec – the competition turns

deadly.

DC:

This book came out of my experience as a secondary teacher at the

Kirov Academy of Ballet in Washington, DC, and Sona’s love of

ballet (we both danced till we were about 11) and TV coverage of

Pretty

Little Liars.

I taught the middle school and high school dancers English, after I

graduated from college.

What

makes this project stand out from the masses of other projects

compared to the juggernaut of Pretty

Little Liars

is the diversity, and the nuances of the ballet world. In initial

brainstorm meetings for the project, we didn’t sit down and say,

“Let’s add some meaningful diversity to this book.” I spent

hours remembering my time teaching at the Kirov Academy of Ballet of

Washington, DC, and making lists of details. I wanted our characters

to reflect the world there. The reality is that there are legions of

Asian dancers that haven’t showed up on the new ballet reality TV

shows like the CW’s Breaking

Pointe or

in documentaries about ballet, and the Misty Copelands of the world

have had a challenging path to success in the ballet world. We wanted

those honest layers in there alongside the universal story of girls

who want something so bad they’re willing to do whatever it takes

to get it.

Why

did you decide to pursue publication under the umbrella of CAKE

rather than as coauthors and an agent (in other words, why not the

"traditional" path)?

SC:

Dhonielle and I both met while pursuing our MFAs in Writing for

Children at the New School. There, we were both working on individual

projects -- and we still are. But we were always coming up with these

crazy, cool and really fun ideas for collaborations. DARK POINTE was

the first we thought had serious potential, and we decided to work on

it together, while still working on our own stuff, which is very

different. It likely won’t be the last collaboration for us, and we

had plenty of other solid ideas that we didn’t want to write

together. What we quickly discovered was that there was something

awesome that happened when you put us in a room together to

brainstorm -- a creative chemistry, an alchemy of sorts. We both have

different strengths -- I am partial to the three-act structure and

plotting, while D is the world-builder -- and we work well together.

We

didn’t want to let all those ideas just fester. So we decided --

based on what we’d seen in the industry of boutique packagers --

that maybe this would be something for us to look into. After careful

planning, we decided we’d pursue this type of publication and

launch this company, alongside working on our individual projects. In

writing DARK POINTE together, we realized it was the perfect first

project for such a venture, and would embody everything we’re

about.

Thanks for sharing your own insights on book packagers and literary development, Sona and Dhonielle.

Related StoriesA Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1The In-Between by Barbara Stewart

Related StoriesA Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 1The In-Between by Barbara Stewart

Published on November 05, 2013 22:00

November 4, 2013

A Closer Look at The New York Times YA Bestsellers List, Part 2

* This is part two of a two-part series.

If you haven't spent time with yesterday's data, you should do that before diving into today's post. This is quite a bit shorter, though it's got far fewer images. Today I wanted to look at the publishers who are represented on the NYT YA List, as well as talk about what the list looks like now that Veronica Roth has jumped to series. I've also got a few concluding thoughts and observations I thought were worth sharing at the end.

Publishers Represented on the NYT YA List

I'm always curious whether there's one publisher which has more books landing on the bestseller list than others. Part of this stems from the idea that perhaps a bigger marketing push is why those books get on the list in the first place and then continued push on titles which maintain their spots over a lengthy period of time. I think, too, it's interesting to keep this in mind with the rise of very cheap and short-term ebook sales and what impact those may have on books which then appear or stick around on the list. Because it's not price that gets books on the list; it's sales numbers.

Because I am human and because counting up the appearance of publishers on a list, I know I made a little bit of a counting misstep. I looked at 47 lists total, which included the extended books -- leaving out the list where Veronica Roth has moved over to series -- and there should be a total of 705 books to tally. But in my final numbers, I missed a few and ended up with a count of only 701 books. So, I've taken the liberty and rounded the biggest numbers by publisher up to the nearest 0 or 5, for simplicity's sake. It did not impact the results.

I've flattened the publishers, folding all of the imprints within their bigger houses. In other words, Tor books and St. Martin's books are counted under Macmillan. Because Penguin and Random House are still appearing as separate houses, I kept them as separate in my tally.

On the 47 weeks worth of lists, a total of 12 publishers are represented. They break down as follows:

Penguin: 295 booksHarper Collins: 140 booksSimon & Schuster: 70 booksRandom House: 60 booksHachette/Little, Brown: 45 booksMacmillan: 45 booksQuirk: 45 booksScholastic: 7 booksDisney: 6 booksBloomsbury: 2 booksHoughton Mifflin Harcourt: 1 bookNicole Reed Books: 1 bookAs I noted in yesterday's post, I have no idea why a self-published "new adult" title got onto the NYT List. Human error is the most likely reason, which I'll talk about in the next section.

It's interesting to see that, without doubt, Penguin dominates with titles on the bestsellers list. Worth noting: Penguin publishes John Green, Rick Yancey, and Sarah Dessen, all of whom spent some time on the list. Harper publishes Roth's series, Random House publishes The Book Thief, and Simon & Schuster publishes Perks of Being a Wallflower. Quirk publishes Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children.

If you're curious about those smaller numbers: HMH published Dark Triumph which was on the list for one week, and Bloomsbury published Falling Kingdoms and S. J. Maas's Crown of Midnight.

E-Book Originals, The Definition of "Series," and Defining "YA"

I talked a bit yesterday about e-books and the impact of e-book sales on the appearance of titles on the list. What I didn't talk about was that a number of e-originals have themselves made the list. These are books which are not in print but only exist in a digital format. This tells us a number of things about the buyers of these books, as well as about what those appearances may say in terms of who or what influences the books that do appear on the list. Or maybe more, who or what influences the titles which last on the list more than a week or two.

The e-book originals -- short stories, it should be noted -- that have appeared on the list include two of the Cassie Clare co-written titles in the "Bane Chronicles" series: "What Really Happened in Peru" and "The Runaway Queen."

Kiera Cass's "The Prince," which was also an e-original short story, appeared on the list as well.

The reason I wanted to point these out is because, as noted yesterday, books jump to the series list after there are three titles published within that series. So the publication of Allegiant meant that Roth moved from the YA list onto the series list. But interestingly, this hasn't always been the case with YA books, and it's been inconsistent.

Taherhi Mafi's "Shatter Me" series made the series list this year, despite the fact the third book within that series has yet to be published. Rather than have potentially two spots on the YA list, the books were instead grouped onto the series list. And the reason? The publication of an e-original titled "Destroy Me."

By that theory, Cass's books should have jumped to the series list with the publication of The Elite, which came after The Selection and "The Prince." But it didn't.

There is clearly some inconsistency and human error going on with the definition of series and it does play a role in what is and is not ending up on the YA list. Had Mafi's books ended up on the YA List, rather than the series list, perhaps there would have been a week or two where women had more spots than men did. But we'll never know because when the final book in her series does publish, it'll definitely be on the series list.

Another thing that interests me on the YA List is how the creators define "YA." As noted previously, two "new adult" authors have made the list: Nicole Reed and Abbi Glines. Both of their books are published for the 17 and older audience, which is spelled out right in the listing about the book on the list. This is an interesting -- and frustrating -- tactic used to get those books on the list meant for books published for the 12-18 market. Would those books stand a chance on the much more crowded adult list, were they listed as being for those 18 and older instead of those 17 and older? How blurry do we allow the lines between YA and not-YA to get, especially when it comes to something as influential as the bestsellers list? And, if we are going to have something called "new adult" fiction, then can we fairly give them a space on the YA list if it's something completely all its own?

There is a lot to dig into here when it comes to readership and buyership. Those e-originals aren't getting their sales through traditional means. I want to know who is buying them. My bet is on teenagers who are devoted fans to the series -- which then would tie into my previous comments about teen influence on the list being why those titles appear once or twice and then disappear. I suspect, too, the e-original format severely limits long-term readership and audience reach.

The Post-Roth List

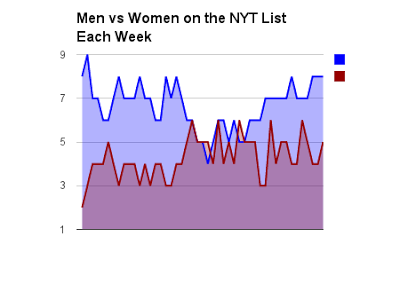

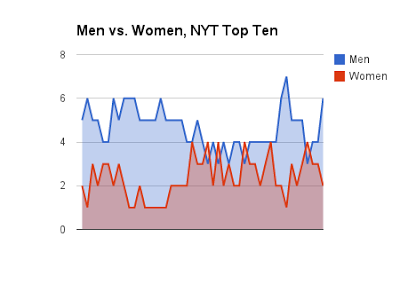

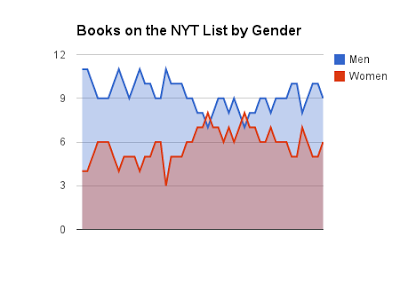

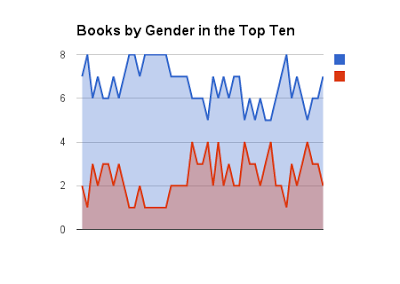

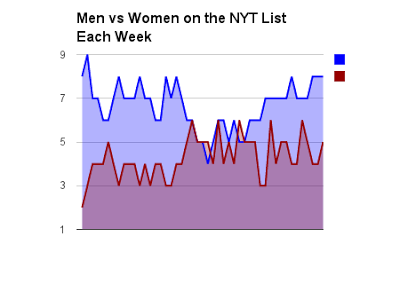

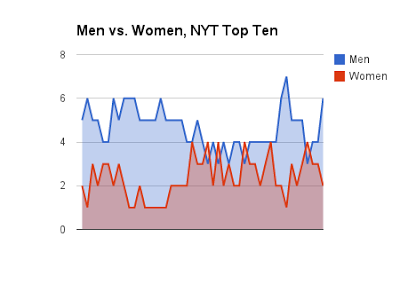

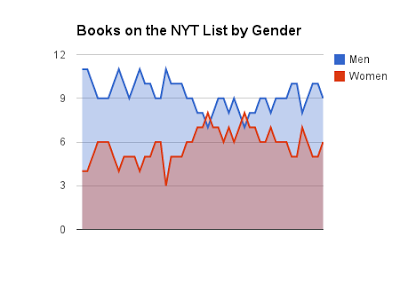

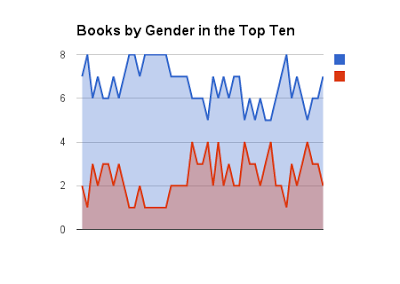

Part of my curiosity about gender and the NYT List came because I knew that Veronica Roth's "Divergent" series moving over to the series list would open up two spots. Would they allow more women in? Or would more men have the chance to land on the list? What would her two spots -- which have been there since week one -- do to the average length of stay for male-written vs. female-written change dramatically now that her two books with 47-week histories are gone?

So far, there has only been one list to look at to think about these questions. But the list that came out when her books went to the series list looks . . . remarkably like every other list so far. No surprises. No one new. Nothing out of left field.

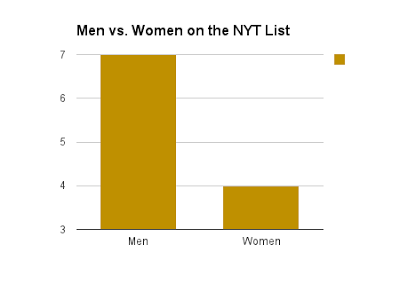

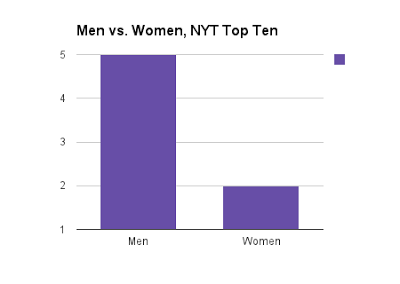

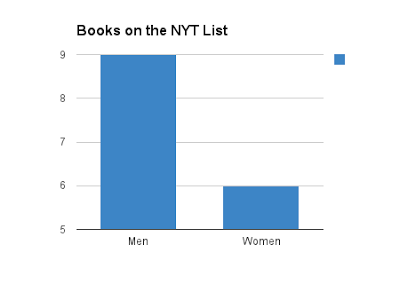

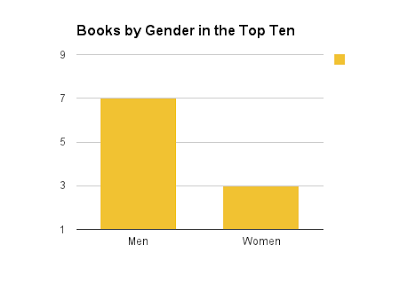

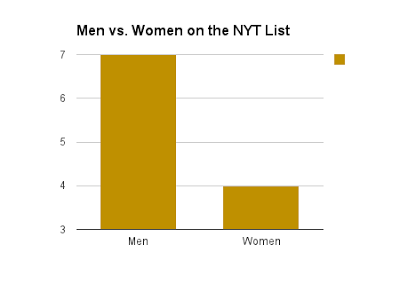

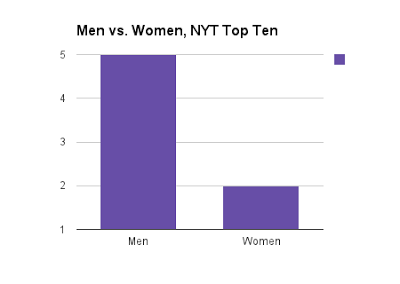

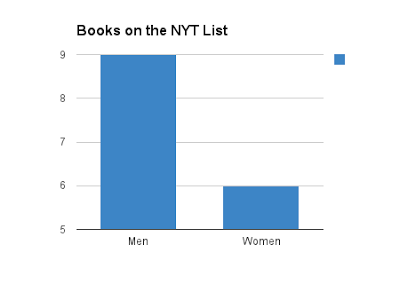

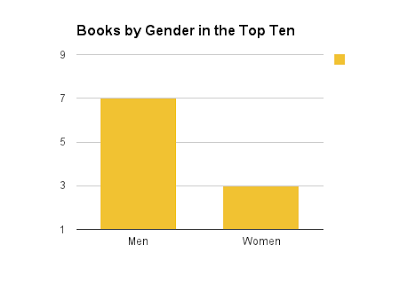

On this week 48 list, the stats broke down as such:

9 men total were on the list 12 books written by men were on the listWithin the top ten, 6 males were on the listWithin the top ten, 8 books written by men were on the list. The average length of stay for these 12 male-written book on the NYT List for week 48 -- the first one after Roth's series shifted -- was 32 weeks.

More stats about this list:

3 women total were on the list3 books written by women were on the listWithin the top ten, 2 females were on the listWithin the top ten, 2 books written by females were on the list.

The average length of stay for these 3 female-written books on the NYT List for week 48? Five Weeks.

Because doing an average of overall length of stay across genders would be silly with only this one week post-Roth to compare, this is a number to still think about. The average length of stay for books on the week 48 list for men is 32. Women, 5. This is going to make a difference the further out we go from here, as I predicted yesterday. It will matter.

The two women who were in the top ten were Marie Lu and Lauren Kate. As you likely know, Marie Lu's series wraps up in November and she, too, will shift over to the series list. This will leave one -- maybe two -- spots open for new faces on the list. More than that, it'll lower the average length of stay for a female-written book on the NYT List even further down.

We'll see if Lauren Kate's book will remain on the list. It debuted at #6, so even if Roth's books remained on the standard list, it's likely Kate's title would have made it on the list. But this list reflects the sales the week Kate's book came out, so it's worth keeping an eye on whether this one has staying power or if it reflects many of the other books which debut on the list one week and slide off the week or two next. Again, and this is all hypothesis, but perhaps those books represent high sales by the actual teen contingent, as they're books teens are eager and excited about as soon as they are published (which isn't to say those books don't remain popular, but rather, they don't sustain the same level of sales in the weeks after initial launch).

If you're curious about publisher representation on the post-Roth list, I've got that for you, too: