Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 126

December 11, 2013

"Best of 2013" and "Best of 2012" YA Lists Compared & What We Should Talk About

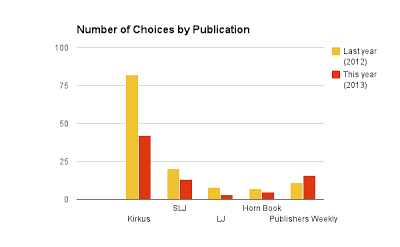

On Tuesday and yesterday, I looked at the data about this year's "best of" lists, as tallied from School Library Journal, Kirkus, Horn Book, Publishers Weekly, and Library Journal's "Best YA for Adults." I used almost the exact same metrics as I did in 2012, adjusting a bit for new categories and removing a couple I didn't necessarily find that interesting or have enough data to pull together into anything worth looking at.

Because I used the same tally sheet and looked at so many of the same factors, I thought it would be worthwhile to compare what the "best of" lists in 2012 looked like against this year's "best of" lists. Were there any notable differences between the two years? Were there more books considered "best" one year than the other? Was there a big difference in gender representation? What about other factors? If "best of" lists give a snapshot of a year in YA, then what will comparing two consecutive years say about preferences in "best" books? Again, this is all data and nothing conclusive can be said about it, but it is interesting to look and speculate.

In both 2012 and 2013, I used the same criteria to define a YA book. I didn't look at non-fiction, and I didn't include graphic novels in the final results. In both years, I also took Amazon's age rating of the book being for those 12 and older as a standard for "YA fiction."

Range and Spread of Titles Selected

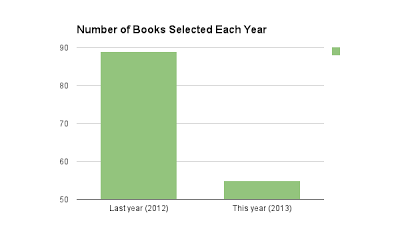

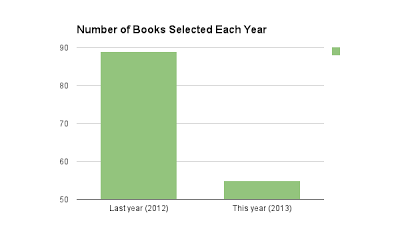

The first thing that caught my attention when looking at the 2013 data was that it seemed like there were far fewer books being labeled "best of" than there were in 2012. Turns out, my suspicions were correct.

Note that this bar chart begins at 50 and Google won't let me change it to begin at 0. But it shouldn't matter, as it's pretty clear there's a difference in titles selected: last year, there were 89 unique titles on the "best of" lists. This year, there were only 55.

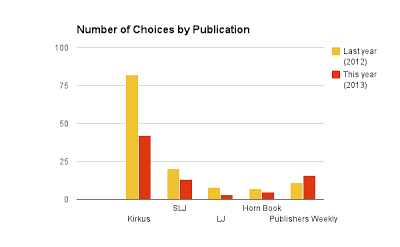

I decided to look at each publication and compare their number of unique choices last year against this year. Every publication selected more YA fiction last year than they did this year, except for Publishers Weekly, which picked 16 titles this year and only 11 last year. There's a big difference in Kirkus's number of choices, where they had selected 82 last year and 42 this year. Repeated titles were included here, as long as it was a unique journal which selected it (in other words, every instance of Far, Far Away counted as an individual title, as long as it was a different journal that picked it).

Even accounting for the non-fiction and graphic novel selections -- which were minimal this year, as well -- there were definitely fewer books selected as "best of" this year.

Does the fewer number of titles being selected as "best of" suggest that maybe this was a weaker year for YA fiction? Or if that's not the case, did fewer books stand out and resonate this year among editors tasked with selecting the bests? Most "best of" lists are decided by vote and by the editors of the journals, and I wonder if there's any correlation between the number of "best of" titles selected and the number of starred reviews earned this year. In other words, did fewer books earn starred reviews in 2013 than in 2012?

Even with Kirkus's more esoteric selections, as discussed yesterday, there seem to be surprisingly few bests this year. Is this a trend we're going to continue to see in the coming years or will 2013 be sort of an outlier?

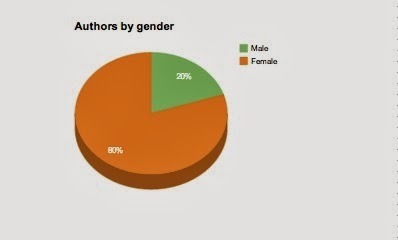

Author Gender and "Best of" Lists

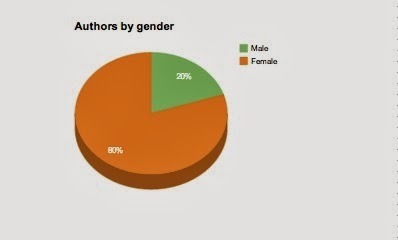

I didn't keep track of the gender of the main characters in 2012 the way I did in 2013 (part of it having to do with having way more books on the 2012 list), but I did look at the gender of the authors on both sets of lists. For 2012, there were a total of 90 authors and in 2013, there were a total of 55.

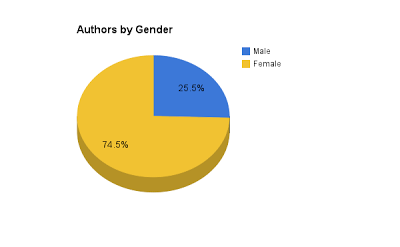

In 2012:

There were 72 females and 18 males.

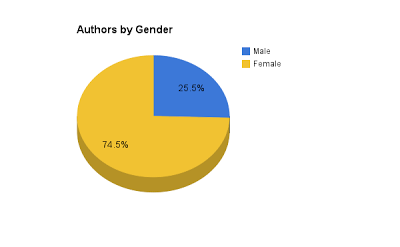

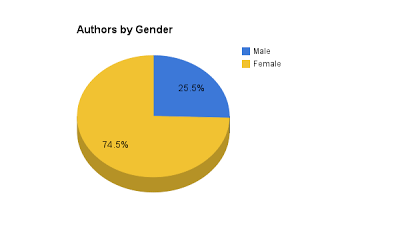

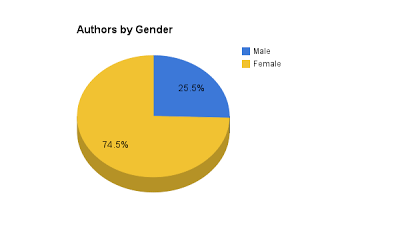

In 2013:

There were 41 females and 14 males.

As can be seen, there was a smaller percentage of female authors in 2013 than there were comparatively in 2012. Eighty percent of the authors in 2012 were female, whereas about 75% were female in 2013.

Although there aren't hard numbers to represent all of the YA books published as categorized by author gender in these years, it does make me wonder a little bit if there were fewer female authors in 2013. Or were there fewer female-written books that stood out as "best?" It's a small percentage drop, of course, but it's an interesting trend, especially when taken in light of the data about the New York Times gender split for their YA list.

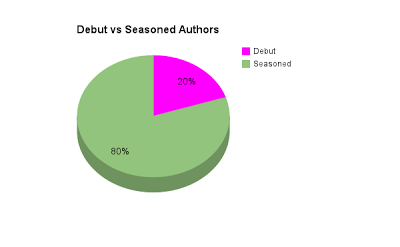

Debut Novelists on the "Best of" Lists

Did debut novelists do better in 2012 than they did in 2013 when it comes to being on the "best of" lists? Let's take a look.

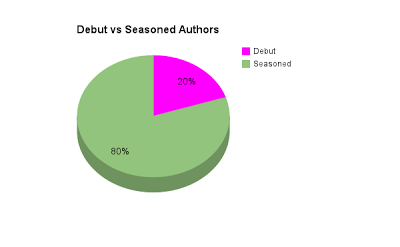

In 2012:

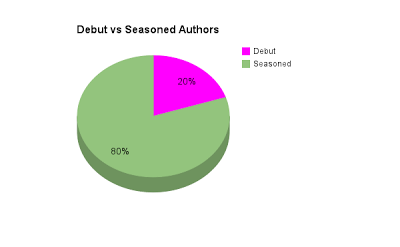

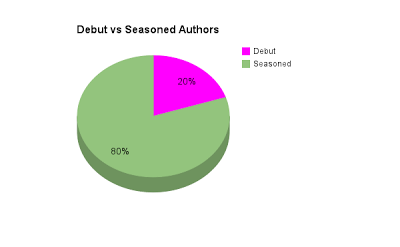

There were a total of 18 debut novelists in 2012, which came to 20% of the total number of authors on the "best of" list.

Compare to 2013:

There were 11 debut novelists in 2013, which also equalled a total of 20% of the authors on this year's "best of" lists. In other words, no difference in debut novelists on the lists in the last year.

There were 11 debut novelists in 2013, which also equalled a total of 20% of the authors on this year's "best of" lists. In other words, no difference in debut novelists on the lists in the last year.

Genre Representation in "Best of" Lists

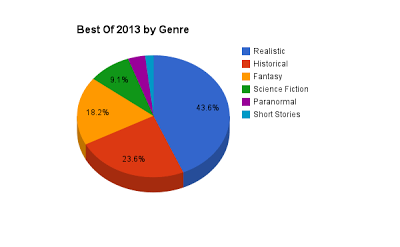

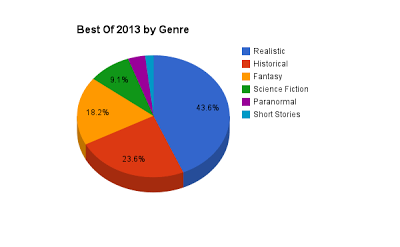

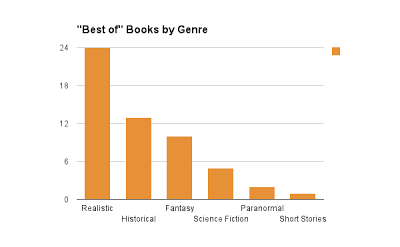

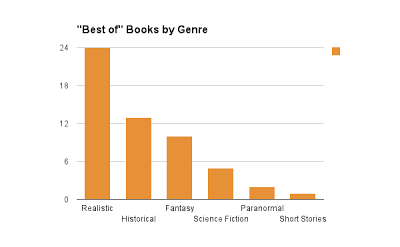

I mentioned that this year, there was a rise in realistic fiction in frequency of appearance on the "best of" lists. I thought it was notable, as the last couple of years have mentioned that realistic fiction would become "the next big thing," and the "best of" lists at least suggested that realistic fiction caught more critical attention this year.

But was there a rise in realistic fiction this year as compared to last year? And if so, what was in abundance last year that maybe didn't show itself as popular among the "best of" lists this year?

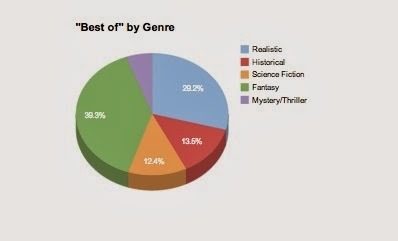

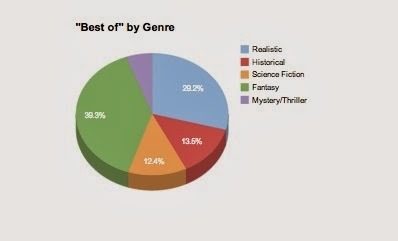

Here's the 2012 breakdown:

Fantasy took up the largest portion of the "best of" lists, though realistic held its own. Last year, when I did the genre breakdown, I made "mystery and thriller" a separate category, which I did not do this year. I suspect if I were to reconsider categories, many of those books would end up under realistic fiction, thus making it about the same size as fantasy in terms of appearances on the list. Historical and science fiction followed in popularity.

There were more historical novels on this year's "best of" lists than there were in 2012, with roughly 24% of the books falling under that genre. Compare to last year's 14%. But what's most notable is that fantasy dropped sharply this year, at roughly 19%, while in 2012, fantasy occupied almost 40% of the "best of" lists. There were also fewer novels categorized as science fiction that appeared in 2013 than in 2012.

There were more historical novels on this year's "best of" lists than there were in 2012, with roughly 24% of the books falling under that genre. Compare to last year's 14%. But what's most notable is that fantasy dropped sharply this year, at roughly 19%, while in 2012, fantasy occupied almost 40% of the "best of" lists. There were also fewer novels categorized as science fiction that appeared in 2013 than in 2012.

Realistic fiction's presence on the "best of" lists definitely increased, even if the mystery/thriller category is rolled into realistic fiction for 2012's counts. This year, realistic fiction was nearly 44% of the "best of" lists.

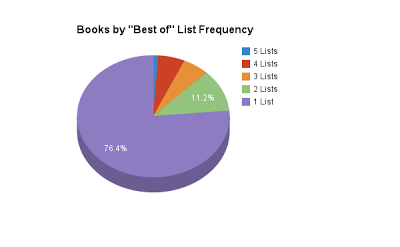

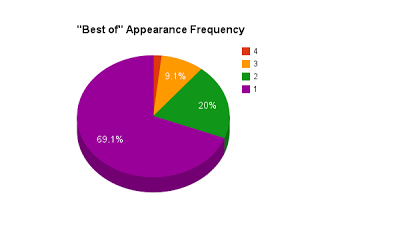

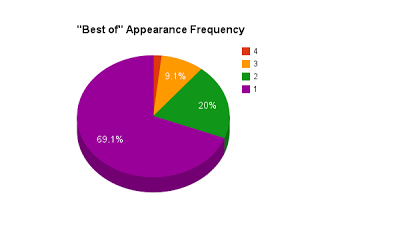

Best of by List Frequency

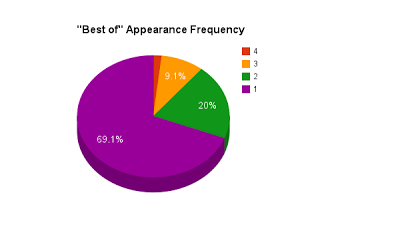

With the fact there were fewer books on this year's "best of" list than in 2012, as well as a shift a bit in terms of genre representation, I thought it would also be worth looking at the frequency of titles appearing across multiple lists. There were 5 lists total, and I was curious whether more books would appear more frequently on lists in 2012 or in 2013.

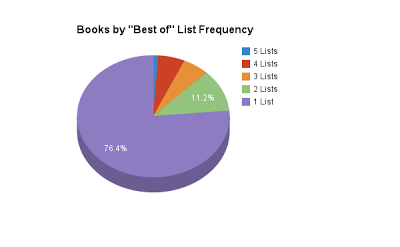

In 2012, here's what the frequency of books on the "best of" books looked like:

The vast majority of books only showed up on one list, though a good portion also showed up on two lists. Smaller numbers appeared on three and four lists, and there was a single book which appeared on all five of the lists (that went to Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity). For the curious, the books which were on four lists each last year were Vaunda Nelson's No Crystal Stair, Margo Lanagan's Brides of Rollrock Island, AS King's Ask the Passengers, John Green's The Fault in Our Stars, and Libba Bray's The Diviners.

The vast majority of books only showed up on one list, though a good portion also showed up on two lists. Smaller numbers appeared on three and four lists, and there was a single book which appeared on all five of the lists (that went to Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity). For the curious, the books which were on four lists each last year were Vaunda Nelson's No Crystal Stair, Margo Lanagan's Brides of Rollrock Island, AS King's Ask the Passengers, John Green's The Fault in Our Stars, and Libba Bray's The Diviners.

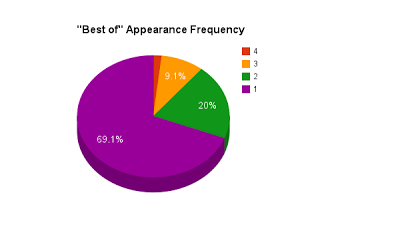

Compare to 2013:

There were a smaller percentage of books appearing on a single list this year than last, but there was a pretty big increase in the percentage of books on two lists, as opposed to one list in 2012. That's percentage-wise, though, of the total number of books across the five lists. Raw numbers show that it was actually only an increase of one book appearing on two lists this year -- 11 in 2013, rather than 10 in 2012. Both years saw a total of five books on three lists, though because of the smaller number of books overall on this year's list, the percentage appears larger.

There were a smaller percentage of books appearing on a single list this year than last, but there was a pretty big increase in the percentage of books on two lists, as opposed to one list in 2012. That's percentage-wise, though, of the total number of books across the five lists. Raw numbers show that it was actually only an increase of one book appearing on two lists this year -- 11 in 2013, rather than 10 in 2012. Both years saw a total of five books on three lists, though because of the smaller number of books overall on this year's list, the percentage appears larger.

As mentioned in a previous data post, there were no books this year that ended up on all five of the "best of" lists (except for Boxers and Saints, which was not included in any of the data because I didn't include it in YA fiction but considered it a graphic novel instead).

So What Does This All Mean?

In the big context of "best of" lists and accolades at the end of any given year in YA fiction, the data doesn't really say a whole lot. It does, however, give us a picture of what a year in YA looks like. This year, it appears we have fewer female authors penning books considered "best of" (though it's still a larger percentage than male authors), and we have many more realistic fiction filling out the lists than other genres.

We have fewer books earning multiple spots on "best of" lists, but with fewer books overall, what does that say? Again, the question I keep circling back to and have from the beginning of looking at this data is how much one list impacts another list and how much marketing may influence these things.

This year felt like a noteworthy one when it came to books being sold to readers and sold to readers in a very big way. There appeared to be a lot more money spent on a lot fewer titles, and I wonder how much of that reflects in these "best of" lists. The more a book is sold as a great book, how much more likely are we to believe that?

Even the most objective readers can't avoid hearing and seeing the buzz about certain books. I'm not suggesting that editorial boards choosing their "best of" are swayed by this kind of marketing, but rather, this kind of marketing really did stick out this year more than other years. Which then leads me to another set of questions that seem to be the ones authors and creative types deal with themselves: do these "best of" list creators stick to their purely objective "best of" picks or do they feel at times pressured to bend to what the popular opinion of the "best of" books might be?

The most popular book this year among the "Best of" selections this year was Rowell's Eleanor & Park. It was a good book.

But this was also a book that received spectacular marketing and publicity. It got a review in the New York Times by John Green, along with five starred reviews. That wasn't lost on the book's marketing, either -- how many places was the book heralded as one that John Green himself loved and that other readers would, too? It was SMART. It helped a new YA author, who had only published one book into the adult market prior, gain immense traction and attention very quickly (it didn't hurt the attention Rowell's second book out this year received, either, as we were reminded that Green loved her first book in the marketing there, too). Readers have fallen in love with Eleanor & Park over and over, and it showed up on nearly every list this year where adult readers were told it's okay to read YA because of books like that.

Was it this year's "best" book? Would this book be seen as this good were it not for all of the marketing behind it? What about without all of the adult praise it earned (you know, it's a "YA book that is okay for grown ups to read")? This book was impossible to avoid, whether you were a YA reader or you weren't a YA reader.

It's hard not to think about the other books that came out this year that were as good as Rowell's. But what were they? Are they some of those books Kirkus called out that, yesterday, I questioned as to why they were on the list in the first place? Have I become accustomed to thinking that outliers on these lists indicate a poor choice? Or is Kirkus on to something I'm unaware of because those books have yet to be sold and marketed to me as a reader (or more accurately, as a librarian who buys these books and then sells them to teen readers)?

The smaller the field of "bests," the more I wonder what was overlooked simply because a few big titles had so much weight behind them.

Of course I have no answers. I just have a lot more questions, and they're the kinds of questions I like to end a year with because they make me reevaluate my own reading, my own means of book recommendation, and my own personal "favorite" or "best of" lists. How much farther out do I want to reach to find hidden gems? How many of the big books should I make sure I do read because maybe I am missing something big there, too?

As of this writing, I haven't yet seen the Booklist nor the BCCB "best of" lists, and I'm curious how those will stack up against these lists. Likewise, what will YALSA committees select as best books with their Printz this year, their Quick Picks, or their Best Fiction for Young Adults?

I'd love thoughts and ideas regarding this year's best of picks, especially as they compare to last year's. Any thoughts? Do you have any books you wish had seen time on the "best of" lists that didn't show up? What about books that appeared on the list that make you scratch your head a bit?

Related Stories"Best of 2013" YA List Breakdown, Part 2"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA Novels

Related Stories"Best of 2013" YA List Breakdown, Part 2"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA Novels

Because I used the same tally sheet and looked at so many of the same factors, I thought it would be worthwhile to compare what the "best of" lists in 2012 looked like against this year's "best of" lists. Were there any notable differences between the two years? Were there more books considered "best" one year than the other? Was there a big difference in gender representation? What about other factors? If "best of" lists give a snapshot of a year in YA, then what will comparing two consecutive years say about preferences in "best" books? Again, this is all data and nothing conclusive can be said about it, but it is interesting to look and speculate.

In both 2012 and 2013, I used the same criteria to define a YA book. I didn't look at non-fiction, and I didn't include graphic novels in the final results. In both years, I also took Amazon's age rating of the book being for those 12 and older as a standard for "YA fiction."

Range and Spread of Titles Selected

The first thing that caught my attention when looking at the 2013 data was that it seemed like there were far fewer books being labeled "best of" than there were in 2012. Turns out, my suspicions were correct.

Note that this bar chart begins at 50 and Google won't let me change it to begin at 0. But it shouldn't matter, as it's pretty clear there's a difference in titles selected: last year, there were 89 unique titles on the "best of" lists. This year, there were only 55.

I decided to look at each publication and compare their number of unique choices last year against this year. Every publication selected more YA fiction last year than they did this year, except for Publishers Weekly, which picked 16 titles this year and only 11 last year. There's a big difference in Kirkus's number of choices, where they had selected 82 last year and 42 this year. Repeated titles were included here, as long as it was a unique journal which selected it (in other words, every instance of Far, Far Away counted as an individual title, as long as it was a different journal that picked it).

Even accounting for the non-fiction and graphic novel selections -- which were minimal this year, as well -- there were definitely fewer books selected as "best of" this year.

Does the fewer number of titles being selected as "best of" suggest that maybe this was a weaker year for YA fiction? Or if that's not the case, did fewer books stand out and resonate this year among editors tasked with selecting the bests? Most "best of" lists are decided by vote and by the editors of the journals, and I wonder if there's any correlation between the number of "best of" titles selected and the number of starred reviews earned this year. In other words, did fewer books earn starred reviews in 2013 than in 2012?

Even with Kirkus's more esoteric selections, as discussed yesterday, there seem to be surprisingly few bests this year. Is this a trend we're going to continue to see in the coming years or will 2013 be sort of an outlier?

Author Gender and "Best of" Lists

I didn't keep track of the gender of the main characters in 2012 the way I did in 2013 (part of it having to do with having way more books on the 2012 list), but I did look at the gender of the authors on both sets of lists. For 2012, there were a total of 90 authors and in 2013, there were a total of 55.

In 2012:

There were 72 females and 18 males.

In 2013:

There were 41 females and 14 males.

As can be seen, there was a smaller percentage of female authors in 2013 than there were comparatively in 2012. Eighty percent of the authors in 2012 were female, whereas about 75% were female in 2013.

Although there aren't hard numbers to represent all of the YA books published as categorized by author gender in these years, it does make me wonder a little bit if there were fewer female authors in 2013. Or were there fewer female-written books that stood out as "best?" It's a small percentage drop, of course, but it's an interesting trend, especially when taken in light of the data about the New York Times gender split for their YA list.

Debut Novelists on the "Best of" Lists

Did debut novelists do better in 2012 than they did in 2013 when it comes to being on the "best of" lists? Let's take a look.

In 2012:

There were a total of 18 debut novelists in 2012, which came to 20% of the total number of authors on the "best of" list.

Compare to 2013:

There were 11 debut novelists in 2013, which also equalled a total of 20% of the authors on this year's "best of" lists. In other words, no difference in debut novelists on the lists in the last year.

There were 11 debut novelists in 2013, which also equalled a total of 20% of the authors on this year's "best of" lists. In other words, no difference in debut novelists on the lists in the last year.Genre Representation in "Best of" Lists

I mentioned that this year, there was a rise in realistic fiction in frequency of appearance on the "best of" lists. I thought it was notable, as the last couple of years have mentioned that realistic fiction would become "the next big thing," and the "best of" lists at least suggested that realistic fiction caught more critical attention this year.

But was there a rise in realistic fiction this year as compared to last year? And if so, what was in abundance last year that maybe didn't show itself as popular among the "best of" lists this year?

Here's the 2012 breakdown:

Fantasy took up the largest portion of the "best of" lists, though realistic held its own. Last year, when I did the genre breakdown, I made "mystery and thriller" a separate category, which I did not do this year. I suspect if I were to reconsider categories, many of those books would end up under realistic fiction, thus making it about the same size as fantasy in terms of appearances on the list. Historical and science fiction followed in popularity.

There were more historical novels on this year's "best of" lists than there were in 2012, with roughly 24% of the books falling under that genre. Compare to last year's 14%. But what's most notable is that fantasy dropped sharply this year, at roughly 19%, while in 2012, fantasy occupied almost 40% of the "best of" lists. There were also fewer novels categorized as science fiction that appeared in 2013 than in 2012.

There were more historical novels on this year's "best of" lists than there were in 2012, with roughly 24% of the books falling under that genre. Compare to last year's 14%. But what's most notable is that fantasy dropped sharply this year, at roughly 19%, while in 2012, fantasy occupied almost 40% of the "best of" lists. There were also fewer novels categorized as science fiction that appeared in 2013 than in 2012.Realistic fiction's presence on the "best of" lists definitely increased, even if the mystery/thriller category is rolled into realistic fiction for 2012's counts. This year, realistic fiction was nearly 44% of the "best of" lists.

Best of by List Frequency

With the fact there were fewer books on this year's "best of" list than in 2012, as well as a shift a bit in terms of genre representation, I thought it would also be worth looking at the frequency of titles appearing across multiple lists. There were 5 lists total, and I was curious whether more books would appear more frequently on lists in 2012 or in 2013.

In 2012, here's what the frequency of books on the "best of" books looked like:

The vast majority of books only showed up on one list, though a good portion also showed up on two lists. Smaller numbers appeared on three and four lists, and there was a single book which appeared on all five of the lists (that went to Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity). For the curious, the books which were on four lists each last year were Vaunda Nelson's No Crystal Stair, Margo Lanagan's Brides of Rollrock Island, AS King's Ask the Passengers, John Green's The Fault in Our Stars, and Libba Bray's The Diviners.

The vast majority of books only showed up on one list, though a good portion also showed up on two lists. Smaller numbers appeared on three and four lists, and there was a single book which appeared on all five of the lists (that went to Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity). For the curious, the books which were on four lists each last year were Vaunda Nelson's No Crystal Stair, Margo Lanagan's Brides of Rollrock Island, AS King's Ask the Passengers, John Green's The Fault in Our Stars, and Libba Bray's The Diviners.Compare to 2013:

There were a smaller percentage of books appearing on a single list this year than last, but there was a pretty big increase in the percentage of books on two lists, as opposed to one list in 2012. That's percentage-wise, though, of the total number of books across the five lists. Raw numbers show that it was actually only an increase of one book appearing on two lists this year -- 11 in 2013, rather than 10 in 2012. Both years saw a total of five books on three lists, though because of the smaller number of books overall on this year's list, the percentage appears larger.

There were a smaller percentage of books appearing on a single list this year than last, but there was a pretty big increase in the percentage of books on two lists, as opposed to one list in 2012. That's percentage-wise, though, of the total number of books across the five lists. Raw numbers show that it was actually only an increase of one book appearing on two lists this year -- 11 in 2013, rather than 10 in 2012. Both years saw a total of five books on three lists, though because of the smaller number of books overall on this year's list, the percentage appears larger.As mentioned in a previous data post, there were no books this year that ended up on all five of the "best of" lists (except for Boxers and Saints, which was not included in any of the data because I didn't include it in YA fiction but considered it a graphic novel instead).

So What Does This All Mean?

In the big context of "best of" lists and accolades at the end of any given year in YA fiction, the data doesn't really say a whole lot. It does, however, give us a picture of what a year in YA looks like. This year, it appears we have fewer female authors penning books considered "best of" (though it's still a larger percentage than male authors), and we have many more realistic fiction filling out the lists than other genres.

We have fewer books earning multiple spots on "best of" lists, but with fewer books overall, what does that say? Again, the question I keep circling back to and have from the beginning of looking at this data is how much one list impacts another list and how much marketing may influence these things.

This year felt like a noteworthy one when it came to books being sold to readers and sold to readers in a very big way. There appeared to be a lot more money spent on a lot fewer titles, and I wonder how much of that reflects in these "best of" lists. The more a book is sold as a great book, how much more likely are we to believe that?

Even the most objective readers can't avoid hearing and seeing the buzz about certain books. I'm not suggesting that editorial boards choosing their "best of" are swayed by this kind of marketing, but rather, this kind of marketing really did stick out this year more than other years. Which then leads me to another set of questions that seem to be the ones authors and creative types deal with themselves: do these "best of" list creators stick to their purely objective "best of" picks or do they feel at times pressured to bend to what the popular opinion of the "best of" books might be?

The most popular book this year among the "Best of" selections this year was Rowell's Eleanor & Park. It was a good book.

But this was also a book that received spectacular marketing and publicity. It got a review in the New York Times by John Green, along with five starred reviews. That wasn't lost on the book's marketing, either -- how many places was the book heralded as one that John Green himself loved and that other readers would, too? It was SMART. It helped a new YA author, who had only published one book into the adult market prior, gain immense traction and attention very quickly (it didn't hurt the attention Rowell's second book out this year received, either, as we were reminded that Green loved her first book in the marketing there, too). Readers have fallen in love with Eleanor & Park over and over, and it showed up on nearly every list this year where adult readers were told it's okay to read YA because of books like that.

Was it this year's "best" book? Would this book be seen as this good were it not for all of the marketing behind it? What about without all of the adult praise it earned (you know, it's a "YA book that is okay for grown ups to read")? This book was impossible to avoid, whether you were a YA reader or you weren't a YA reader.

It's hard not to think about the other books that came out this year that were as good as Rowell's. But what were they? Are they some of those books Kirkus called out that, yesterday, I questioned as to why they were on the list in the first place? Have I become accustomed to thinking that outliers on these lists indicate a poor choice? Or is Kirkus on to something I'm unaware of because those books have yet to be sold and marketed to me as a reader (or more accurately, as a librarian who buys these books and then sells them to teen readers)?

The smaller the field of "bests," the more I wonder what was overlooked simply because a few big titles had so much weight behind them.

Of course I have no answers. I just have a lot more questions, and they're the kinds of questions I like to end a year with because they make me reevaluate my own reading, my own means of book recommendation, and my own personal "favorite" or "best of" lists. How much farther out do I want to reach to find hidden gems? How many of the big books should I make sure I do read because maybe I am missing something big there, too?

As of this writing, I haven't yet seen the Booklist nor the BCCB "best of" lists, and I'm curious how those will stack up against these lists. Likewise, what will YALSA committees select as best books with their Printz this year, their Quick Picks, or their Best Fiction for Young Adults?

I'd love thoughts and ideas regarding this year's best of picks, especially as they compare to last year's. Any thoughts? Do you have any books you wish had seen time on the "best of" lists that didn't show up? What about books that appeared on the list that make you scratch your head a bit?

Related Stories"Best of 2013" YA List Breakdown, Part 2"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA Novels

Related Stories"Best of 2013" YA List Breakdown, Part 2"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA Novels

Published on December 11, 2013 22:00

December 10, 2013

"Best of 2013" YA List Breakdown, Part 2

This is part two of this year's "best of YA" list breakdown. Make sure you read yesterday's post, or at least the introduction of it, to understand why and how this works. To summarize the key points and to make sense of today's data, I'll repeat some of the important details: none of the data presented here is meant to "prove" anything. It's presented in order to offer some discussion points, to explore trends and themes within the books deemed as the "best" of this year's YA fiction, and any errors in data tabulation are mine and mine alone (and hopefully, there are few, if none!).

All data is based on 55 book titles, 55 authors, and in situations where discussion turns to main characters in a book, there are 62 identified main characters. All of the data is pulled from five "best of" lists: School Library Journal, Kirkus, Horn Book, Library Journal's "YA for Adults," and Publishers Weekly.

I thought it would be interesting to break down the lists into less "big picture" stuff and into smaller picture stuff. Where yesterday looked at things like presence of books featuring POC or LGBTQ characters, as well as gender breakdowns of both authors and main characters, today I wanted to look at more granular list data. All of my raw data can be accessed here. It's not necessarily pretty, but I'm happy if people want to use it to draw additional connections between and among "best of" titles. Some of the information I included on the chart did not make my blog posts (there was too little to talk about in terms of print run, genre, and gender, especially compared to last year) and some of it will appear in tomorrow's comparison post between 2012 "best of" lists and this year's "best of" lists.

So with that, let's dig in.

Month of Publication

Were books published earlier in the year more likely than those published later in the year to make the "best of" lists? Or, because their newness and shininess wore off prior to decision-making time, were they less likely to make the lists?

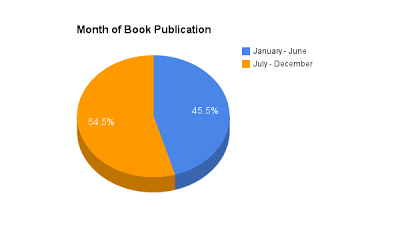

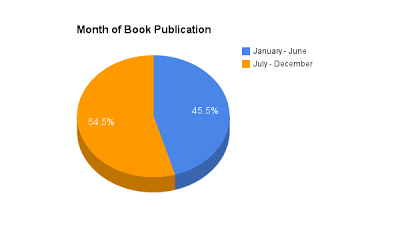

When it came to books published in the first half of the year (January - June) against those which published in the second half of the year (July - December), here's the breakdown:

"Best of" books published between January and June came to 25 total titles, while those published between July and December equalled 30. There's not a major difference between representation of titles in the first half of the year and those in the second half.

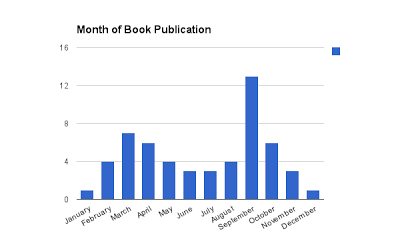

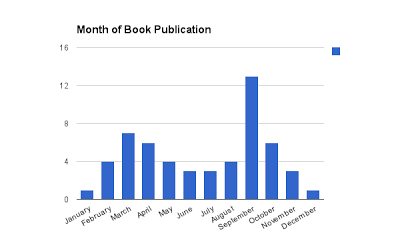

What about breaking it down more? Is there a month where more "best of" books were published? The answer to this one is yes.

The leader of the pack this year is September -- thirteen of the books on this year's "best of" lists were published that month. March had the second highest number of books on the lists, with 7, followed by October and April with six each.

Worth noting in this data is something I'm trying to better understand. On Kirkus's list, one of the books listed (Nowhere to Run by Claire Griffin) appeared to have numerous publication dates, according to Amazon's various listings. It was difficult to parse out whether this book was actually published this year or was published last year, since I saw a November 2012 date, as well as a March 2013 date. Kirkus made a handful of choices this year which didn't make perfect sense to me, and I can't help wonder if maybe that 2012 publication date was accurate. Either way, I operated as though the book was published in March of this year.

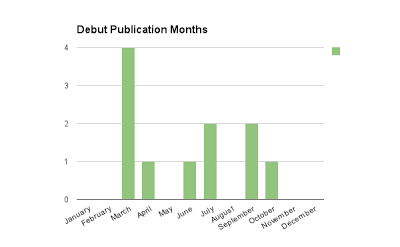

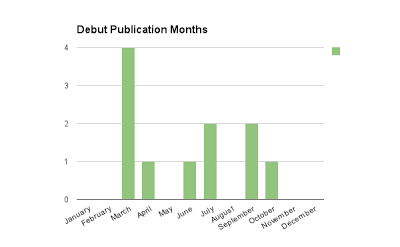

What about the month of publication for those debut authors? Was there a better month to be a debut author and end up on the "best of" lists?

There were four debut novels on the "best of" list published in March, followed by two in July and September. April, June, and October had one each.

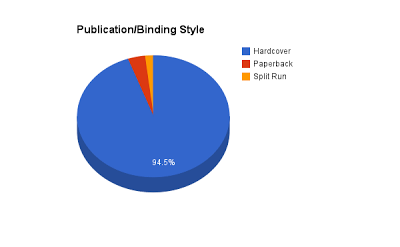

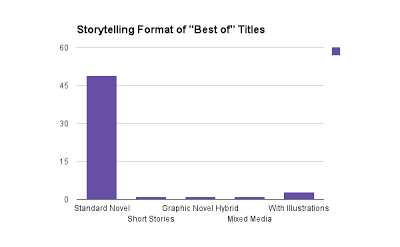

Publication Format

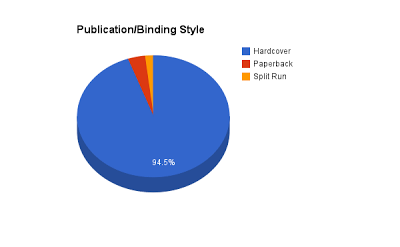

I'm always curious whether hardcovers or paperback originals do better on the "best of" lists. There seem to be fewer paperback originals published in YA than hardcovers, but it's a category I still like looking at. If there is data on this at all, I would love to know about it.

One thing I wanted to point out in this data was something that interested me with the Kirkus list. One of their titles, Outcast Oracle, appears not to be for sale in a non-e-book format in the general market. I checked both Amazon and Barnes and Noble and it's only available for purchase as a Kindle or Nook book. I went to the publisher's website to see if there was indeed a print run at all, and it appears you can buy a paperback copy from the publisher directly. I also hopped onto Baker & Taylor, which is where my library purchases its books (and where a large percentage of public libraries make their purchases) and the book is not available on there in any format.

Which makes me wonder a little bit about how valuable that title being on the list is, since getting access to it is such a hurdle. You either need an ereader OR you need to purchase direct from the publisher. Will having it on this list give it a bump in sales or encourage an easy way to purchase it? I'll talk a little bit more about this tomorrow, since it's fascinating to me what including this particular title might suggest.

But back to the category at hand: I looked at hardcover books, paperback originals (which is where I stuck the title above), and those books which feature a split run, where both a hardcover and a paperback are published simultaneously.

There's no question that hardcover format dominated the "best of" lists, with 52 of the titles published as hardcover. Two books were published as paperback originals, which included both the title noted above, as well as Kelsey Sutton's Some Quiet Place. One book appeared to be a split run, which was the previously noted Nowhere to Run by Claire Griffin.

Were there fewer paperback originals published this year? Fewer split runs? Of course, some publishers only do paperback originals (like Flux) and some publishers make it clear their "bigger" titles are hardcover. I've yet to figure out what it means when a book is published as split, if anything (this year, a few books that were published split run but weren't on the "best of" lists include Jody Casella's The Thin Space, Sarah McCarry's All Our Pretty Songs, and Hannah Moskowitz's Teeth).

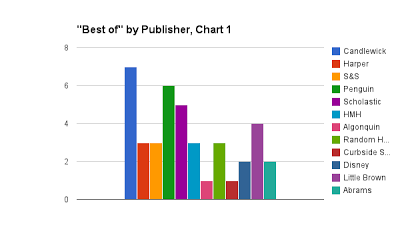

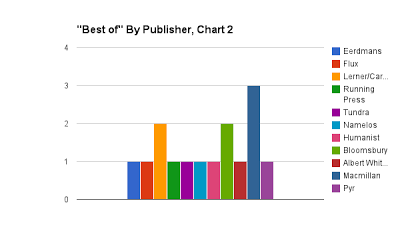

Publisher Representation on the "Best Of" Lists

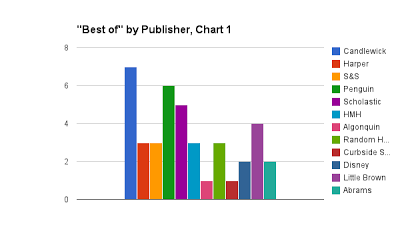

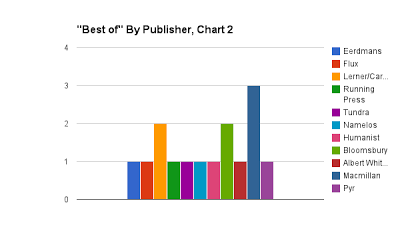

Are there publishers which tend to do better on the "best of" lists? I've always had it in my mind that some publishers work on books that are less mainstream, a little riskier, and that those books do tend to be noticed on the end-of-year lists for those things. Candlewick is perhaps the one which stands out most in my mind for this, as well as Lerner/Carolrhoda LAB.

I've flattened all of the imprints into their respective publishers for simplicity's sake (so, St. Martin's titles are under Macmillan), and because I wanted it to be readable, I broke it into two charts. Here's a look at how the various publishers did on the "best of" lists:

I purposefully didn't do it in a decline since that would mess up the scaling on the charts themselves and I wanted these to be as close to the same scale as possible. But as you can see, Candlewick led the publishers with the most books on the "best of" lists, with a total of 7 titles. Penguin had 6, with 5 titles from Scholastic, 4 from Little, Brown, and 3 each from Harper, Macmillan, Simon & Schuster, and Houghton Mifflin.

As should be clear, there are a lot of titles on the "best of" list not published by a Big 6/5 publisher (so, not a book published by Harper, Little, Brown, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, Penguin/Random House). Comparatively, mid/small/indie presses had more titles on these lists: 33 of the books on the "best of" list came from non-Big 6/5 publishers, while 22 did.

I think this is pretty impressive, especially with Candlewick's large presence. Carolrhoda LAB had two titles, which is also impressive given how small their seasonal lists are.

"Best of" Lists and Starred Reviews Earned

Since we know the "best of" books now, is it fair to assume that books which appeared more frequently on the lists tended to have more starred reviews in the six major review journals?

I pulled the starred reviews from ShelfTalker's round up of "The Stars So Far" in November. I looked at stars earned from the following publications: BCCB, Booklist, Kirkus, SLJ, PW, and Horn Book. Of course, there's a lot of leeway and error that can happen here. Not all journals will review all books. Not all journals review the books in a timely fashion, and so there's a possibility that some of these books will earn stars later.

Not a single one of the YA novels I looked at had earned stars from all six of those publications, either.

Among the "best of" books, here's how the starred reviews broke down:

Seven books earned 5 starred reviewsFour Books earned 4 starred reviewsThirteen books earned 3 starred reviewsFourteen books earned 2 starred reviewsSixteen books earned 1 starred review

The breakdown doesn't surprise me a whole lot, especially because the majority of the books on the "best of" lists came from Kirkus's list, and they tended to have earned a star from Kirkus. In other words, a lot of single-starred books were the books Kirkus selected as "best" (though certainly not all).

So what about starred review frequency against the frequency to which books appeared on "best of" lists? Here's the chart:

List Appearances vs. Star Earnings5 lists4 lists3 lists2 lists1 list6 stars000005 stars012314 stars001403 stars0012102 stars0012111 star000016

Again, no books made all five lists, and the bulk of the books fell into the category of landing on one list and earning one, two, or three stars.

Eleanor & Park, the book with the most placements on the "best of" lists this year, earned five starred reviews.

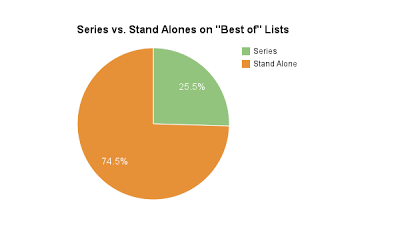

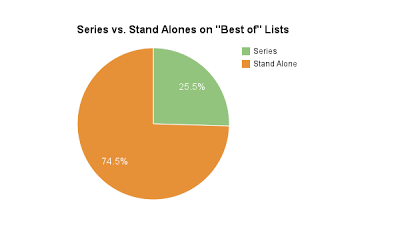

Series vs. Stand Alone Titles on the "Best of" Lists

To wrap up the data, let's look at a simple but worthwhile aspect: do series books do better or worse than stand alone titles on the "best of" lists? This is, I think, impacted pretty significantly by genre of the "best of" books this year, since realistic fiction tends to produce fewer series books than other genres.

In this data, I included companion and prequels as "series" books (so Rose Under Fire and Invasion were rolled into that data).

Roughly one quarter of the "best of" lists were series books, while three-quarters were stand alone titles. Of those books which were part of a series, there were:two prequelsone companionsix were the first in a seriesthree were the second book in a seriestwo that were third books.

Some Concluding Thoughts on the 2013 Data

While I've commented throughout on what I think the takeaways or questions are about the data and "best of" lists this year, I did have a couple of other thoughts to share, and I would love if anyone wanted to weigh in on what they've seen. I have one final post coming tomorrow that will compare this year's data with last year's, which I think will spark some interesting conversation.

First, it's worth noting that Kirkus's list is the lengthiest again this year, and it's also the most strange. I'm confused by their inclusion of a novel that has been categorized in numerous places, including the publisher's own catalog, as "middle grade." That's Fireborn by Toby Forward. Because Amazon listed the age range as 12 and older, I did include it all of the data, but since it's a book not published until after the "best of" appeared, I'll be curious what readers and other critics say is the true age range. To me, it even looks middle grade.

Likewise, Kirkus included more indie press titles (note self-published, but actual indie press) than other publications did. This led me to some of the questions above about Outcast Oracle and it makes me question who their list might be intended for. Any reader who spent time with their list likewise probably noticed it was difficult to parse out their picks from the paid-for advertising of books between their selections, too. If there are more and more titles being selected as "best of" that are difficult to acquire for, say, purchasers at institutions, it makes me wonder how much value the list itself has for users like myself, a librarian who does sometimes supplement collections with titles I may have missed. If it's a book I cannot get without jumping through hoops, though, why bother?

On the other hand, the more esoteric choices make me wonder how many gems slip through the cracks each year because they are from smaller presses. Right now, I think we might have a dark horse for YALSA awards, as well as an under-sung gem Chris L. Terry's Zero Fade.

Overall, this year's list had a much smaller range of titles than I thought. Is it because this is a weaker year for YA overall or do the lists have an unintentional (or intentional) impact on one another? Horn Book, for example, only had 5 YA titles included in their "best of," and LJ's "YA for Adults" only had three by the criteria I used.

There's nothing that can be said conclusively, of course. But what makes "best of" lists interesting to look at as data, rather than as something more subjective, is that it lets you consider the year in a snapshot. This might have been a weaker YA year. It may have been the year that male main characters were stronger than female. It may have continued a trend of featuring a small number of LGBTQ characters. It's also interesting to consider what this "best of" snapshot will indicate in the future, too. Will we have more books of a certain ilk because they're more likely to perform better?

Stick around for tomorrow's thoughts and comparisons between this year's list and last year's. Although again it won't make any hard conclusions, it can shed some insight into some of these questions.

Related Stories"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read Pile

Related Stories"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read Pile

All data is based on 55 book titles, 55 authors, and in situations where discussion turns to main characters in a book, there are 62 identified main characters. All of the data is pulled from five "best of" lists: School Library Journal, Kirkus, Horn Book, Library Journal's "YA for Adults," and Publishers Weekly.

I thought it would be interesting to break down the lists into less "big picture" stuff and into smaller picture stuff. Where yesterday looked at things like presence of books featuring POC or LGBTQ characters, as well as gender breakdowns of both authors and main characters, today I wanted to look at more granular list data. All of my raw data can be accessed here. It's not necessarily pretty, but I'm happy if people want to use it to draw additional connections between and among "best of" titles. Some of the information I included on the chart did not make my blog posts (there was too little to talk about in terms of print run, genre, and gender, especially compared to last year) and some of it will appear in tomorrow's comparison post between 2012 "best of" lists and this year's "best of" lists.

So with that, let's dig in.

Month of Publication

Were books published earlier in the year more likely than those published later in the year to make the "best of" lists? Or, because their newness and shininess wore off prior to decision-making time, were they less likely to make the lists?

When it came to books published in the first half of the year (January - June) against those which published in the second half of the year (July - December), here's the breakdown:

"Best of" books published between January and June came to 25 total titles, while those published between July and December equalled 30. There's not a major difference between representation of titles in the first half of the year and those in the second half.

What about breaking it down more? Is there a month where more "best of" books were published? The answer to this one is yes.

The leader of the pack this year is September -- thirteen of the books on this year's "best of" lists were published that month. March had the second highest number of books on the lists, with 7, followed by October and April with six each.

Worth noting in this data is something I'm trying to better understand. On Kirkus's list, one of the books listed (Nowhere to Run by Claire Griffin) appeared to have numerous publication dates, according to Amazon's various listings. It was difficult to parse out whether this book was actually published this year or was published last year, since I saw a November 2012 date, as well as a March 2013 date. Kirkus made a handful of choices this year which didn't make perfect sense to me, and I can't help wonder if maybe that 2012 publication date was accurate. Either way, I operated as though the book was published in March of this year.

What about the month of publication for those debut authors? Was there a better month to be a debut author and end up on the "best of" lists?

There were four debut novels on the "best of" list published in March, followed by two in July and September. April, June, and October had one each.

Publication Format

I'm always curious whether hardcovers or paperback originals do better on the "best of" lists. There seem to be fewer paperback originals published in YA than hardcovers, but it's a category I still like looking at. If there is data on this at all, I would love to know about it.

One thing I wanted to point out in this data was something that interested me with the Kirkus list. One of their titles, Outcast Oracle, appears not to be for sale in a non-e-book format in the general market. I checked both Amazon and Barnes and Noble and it's only available for purchase as a Kindle or Nook book. I went to the publisher's website to see if there was indeed a print run at all, and it appears you can buy a paperback copy from the publisher directly. I also hopped onto Baker & Taylor, which is where my library purchases its books (and where a large percentage of public libraries make their purchases) and the book is not available on there in any format.

Which makes me wonder a little bit about how valuable that title being on the list is, since getting access to it is such a hurdle. You either need an ereader OR you need to purchase direct from the publisher. Will having it on this list give it a bump in sales or encourage an easy way to purchase it? I'll talk a little bit more about this tomorrow, since it's fascinating to me what including this particular title might suggest.

But back to the category at hand: I looked at hardcover books, paperback originals (which is where I stuck the title above), and those books which feature a split run, where both a hardcover and a paperback are published simultaneously.

There's no question that hardcover format dominated the "best of" lists, with 52 of the titles published as hardcover. Two books were published as paperback originals, which included both the title noted above, as well as Kelsey Sutton's Some Quiet Place. One book appeared to be a split run, which was the previously noted Nowhere to Run by Claire Griffin.

Were there fewer paperback originals published this year? Fewer split runs? Of course, some publishers only do paperback originals (like Flux) and some publishers make it clear their "bigger" titles are hardcover. I've yet to figure out what it means when a book is published as split, if anything (this year, a few books that were published split run but weren't on the "best of" lists include Jody Casella's The Thin Space, Sarah McCarry's All Our Pretty Songs, and Hannah Moskowitz's Teeth).

Publisher Representation on the "Best Of" Lists

Are there publishers which tend to do better on the "best of" lists? I've always had it in my mind that some publishers work on books that are less mainstream, a little riskier, and that those books do tend to be noticed on the end-of-year lists for those things. Candlewick is perhaps the one which stands out most in my mind for this, as well as Lerner/Carolrhoda LAB.

I've flattened all of the imprints into their respective publishers for simplicity's sake (so, St. Martin's titles are under Macmillan), and because I wanted it to be readable, I broke it into two charts. Here's a look at how the various publishers did on the "best of" lists:

I purposefully didn't do it in a decline since that would mess up the scaling on the charts themselves and I wanted these to be as close to the same scale as possible. But as you can see, Candlewick led the publishers with the most books on the "best of" lists, with a total of 7 titles. Penguin had 6, with 5 titles from Scholastic, 4 from Little, Brown, and 3 each from Harper, Macmillan, Simon & Schuster, and Houghton Mifflin.

As should be clear, there are a lot of titles on the "best of" list not published by a Big 6/5 publisher (so, not a book published by Harper, Little, Brown, Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, Penguin/Random House). Comparatively, mid/small/indie presses had more titles on these lists: 33 of the books on the "best of" list came from non-Big 6/5 publishers, while 22 did.

I think this is pretty impressive, especially with Candlewick's large presence. Carolrhoda LAB had two titles, which is also impressive given how small their seasonal lists are.

"Best of" Lists and Starred Reviews Earned

Since we know the "best of" books now, is it fair to assume that books which appeared more frequently on the lists tended to have more starred reviews in the six major review journals?

I pulled the starred reviews from ShelfTalker's round up of "The Stars So Far" in November. I looked at stars earned from the following publications: BCCB, Booklist, Kirkus, SLJ, PW, and Horn Book. Of course, there's a lot of leeway and error that can happen here. Not all journals will review all books. Not all journals review the books in a timely fashion, and so there's a possibility that some of these books will earn stars later.

Not a single one of the YA novels I looked at had earned stars from all six of those publications, either.

Among the "best of" books, here's how the starred reviews broke down:

Seven books earned 5 starred reviewsFour Books earned 4 starred reviewsThirteen books earned 3 starred reviewsFourteen books earned 2 starred reviewsSixteen books earned 1 starred review

The breakdown doesn't surprise me a whole lot, especially because the majority of the books on the "best of" lists came from Kirkus's list, and they tended to have earned a star from Kirkus. In other words, a lot of single-starred books were the books Kirkus selected as "best" (though certainly not all).

So what about starred review frequency against the frequency to which books appeared on "best of" lists? Here's the chart:

List Appearances vs. Star Earnings5 lists4 lists3 lists2 lists1 list6 stars000005 stars012314 stars001403 stars0012102 stars0012111 star000016

Again, no books made all five lists, and the bulk of the books fell into the category of landing on one list and earning one, two, or three stars.

Eleanor & Park, the book with the most placements on the "best of" lists this year, earned five starred reviews.

Series vs. Stand Alone Titles on the "Best of" Lists

To wrap up the data, let's look at a simple but worthwhile aspect: do series books do better or worse than stand alone titles on the "best of" lists? This is, I think, impacted pretty significantly by genre of the "best of" books this year, since realistic fiction tends to produce fewer series books than other genres.

In this data, I included companion and prequels as "series" books (so Rose Under Fire and Invasion were rolled into that data).

Roughly one quarter of the "best of" lists were series books, while three-quarters were stand alone titles. Of those books which were part of a series, there were:two prequelsone companionsix were the first in a seriesthree were the second book in a seriestwo that were third books.

Some Concluding Thoughts on the 2013 Data

While I've commented throughout on what I think the takeaways or questions are about the data and "best of" lists this year, I did have a couple of other thoughts to share, and I would love if anyone wanted to weigh in on what they've seen. I have one final post coming tomorrow that will compare this year's data with last year's, which I think will spark some interesting conversation.

First, it's worth noting that Kirkus's list is the lengthiest again this year, and it's also the most strange. I'm confused by their inclusion of a novel that has been categorized in numerous places, including the publisher's own catalog, as "middle grade." That's Fireborn by Toby Forward. Because Amazon listed the age range as 12 and older, I did include it all of the data, but since it's a book not published until after the "best of" appeared, I'll be curious what readers and other critics say is the true age range. To me, it even looks middle grade.

Likewise, Kirkus included more indie press titles (note self-published, but actual indie press) than other publications did. This led me to some of the questions above about Outcast Oracle and it makes me question who their list might be intended for. Any reader who spent time with their list likewise probably noticed it was difficult to parse out their picks from the paid-for advertising of books between their selections, too. If there are more and more titles being selected as "best of" that are difficult to acquire for, say, purchasers at institutions, it makes me wonder how much value the list itself has for users like myself, a librarian who does sometimes supplement collections with titles I may have missed. If it's a book I cannot get without jumping through hoops, though, why bother?

On the other hand, the more esoteric choices make me wonder how many gems slip through the cracks each year because they are from smaller presses. Right now, I think we might have a dark horse for YALSA awards, as well as an under-sung gem Chris L. Terry's Zero Fade.

Overall, this year's list had a much smaller range of titles than I thought. Is it because this is a weaker year for YA overall or do the lists have an unintentional (or intentional) impact on one another? Horn Book, for example, only had 5 YA titles included in their "best of," and LJ's "YA for Adults" only had three by the criteria I used.

There's nothing that can be said conclusively, of course. But what makes "best of" lists interesting to look at as data, rather than as something more subjective, is that it lets you consider the year in a snapshot. This might have been a weaker YA year. It may have been the year that male main characters were stronger than female. It may have continued a trend of featuring a small number of LGBTQ characters. It's also interesting to consider what this "best of" snapshot will indicate in the future, too. Will we have more books of a certain ilk because they're more likely to perform better?

Stick around for tomorrow's thoughts and comparisons between this year's list and last year's. Although again it won't make any hard conclusions, it can shed some insight into some of these questions.

Related Stories"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read Pile

Related Stories"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1November and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read Pile

Published on December 10, 2013 22:00

December 9, 2013

"Best of 2013 YA" List Breakdown, Part 1

Welcome to the third annual "Best of YA" list break down. Since 2011, I've gone through the "best of" lists developed by the biggest trade review journals and pulled together some statistics about those books. Which ones have repeat appearances? Is there a gender representation difference in the books deemed the best? What do we see in terms of POC, LGBTQ representation, and lots more.

This year, I wanted to look at a number of factors like I did last year, and it requires more than one post to do so. Because I still had all of my data from last year pulled into a single space (I did not in 2011, where all of my information was posted in another forum), I've written third post as well, comparing the data from last year against this year's. They will publish today, tomorrow, and on Thursday.

The "best of" lists I looked at this year are the same ones I analyzed last year: School Library Journal, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, Horn Book, and the Library Journal list of Best YA for Adults. I like to look at that last one, the YA for Adults, because I think it's worth keeping an eye on and comparing with the lists that are geared less toward adults -- are there crossover titles? Are there different titles completely? It adds another flavor to the data.

Because they come out a little bit later, I have not looked at the best of lists from Booklist nor BCCB, though it's possible I may look at them comparatively in the new year (BCCB's list comes out in January and Booklist's should be out this week, either prior to this post or after it). I limited what I looked at to YA fiction only. This means no graphic novels (though if you're curious, the graphic novels which made this combination of lists include Boxers and Saints, on all five of the lists; Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Lieutenant on two of the lists; Will & Whit on one of the lists; Romeo & Juliet on one of the lists; and March on one of the lists) and I did not include non-fiction titles (of which there were very few).

I made my determination on whether a book was a YA book or not based on the criteria that Amazon listed it as a book for those age 12 and older. This meant some books which have been debated as being "for YA readers or not," like Tom McNeal's Far, Far Away, were indeed included in my count. I did not include illustrators for books that feature graphic or illustrative elements in my author counts or breakdowns.

Though more relevant to tomorrow's post than today's, I pulled my information about starred reviews from ShelfTalker's last updated "The Stars So Far" post; since this was last updated in mid-November, it's possible some of these titles may have earned additional stars since then. Information about LGBTQ representation in these books was pulled from Malinda Lo's tallying, along with notes I've made to myself on the books I have read.

Before diving in, some caveats: none of this data means anything. I'm not trying to draw conclusions nor suggest certain things about the books that popped up on the "best of" lists. Errors here in terms of counts, in my decision to list a book as featuring a POC, in my tallying of MCs by gender, and so forth, are all my own. I have not read all of these books, so sometimes, I had to make an educated guess based on reviews I read. Tomorrow, I'll link to all of my raw data in the introduction.

There were a total of 55 books on these lists, 55 authors, and a total of 62 main characters, as some books were told through more than one point of view.

With that, let's see what there is to see in this year's "Best of YA" lists.

Gender Representation in the "Best of" Lists

First, let's look at gender and the "best of" lists. Do we have more male authors represented or do we have more female authors?

There were a total of 55 authors represented on all of the "best of lists," with 14 being male and 41 being female. In other words, roughly three-quarters of the authors this year were female, while one-quarter were male. This is a really interesting breakdown, considering that the breakdown by author gender on the New York Times Lists (in this post and this post) showed something different.

One of the comments I received on my New York Times post breakdowns was that it would be interesting to look at the main character genders in the books listed. Since I didn't look at that element in those posts, I thought I'd give it a shot with the "best of" lists this year.

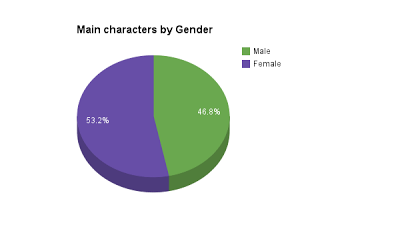

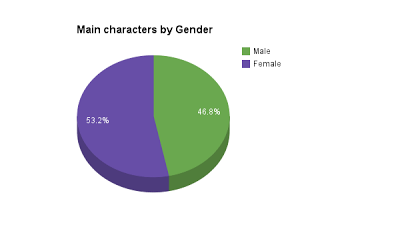

As noted, there are more main characters than there are authors, so this is out of a total of 62 characters. Again, not having read all of the books, this is based on my best guesses having read through many reviews of the titles listed. I counted main characters as those who have a voice in the story. I did not include the Marcus Sedgwick book, since it is a collection of short stories and not having read it, making a call was impossible.

This chart tells quite a bit of a different story than the one above. Of the 62 main characters, 29 were male, and 33 were female. The percentages are much closer to even when we look at main character gender rather than look at the author's gender alone.

This chart tells quite a bit of a different story than the one above. Of the 62 main characters, 29 were male, and 33 were female. The percentages are much closer to even when we look at main character gender rather than look at the author's gender alone.

There are a couple of questions to think about with this: Did we have much better male-led stories this year? Or do we tend to take male-led stories as "better" than those led by female? This is a question I've been thinking about a lot, as it's something impossible not to think about. Female-led stories tend to have more romance in them, and it's possible we have a bias against romance. Worthwhile readings on this topic are this post and this post over at Crossreferencing.

Again, I'm making no conclusions here, but I think these are questions worth thinking about. It does make me want to revisit my NYT analysis now and look at the gender of the main character, especially as some people took problem with the fact there was more male representation when it came to author appearance on the list. I have a suspicion that looking at the gender of the main characters of those books wouldn't actually change my findings very much.

Debut Authors vs. More Seasoned Authors

What kind of break down is there between new authors and those who are on their second, fifth, or twentieth book? Are there more books by authors who've done their time on the "best of" lists or more by debut authors?

I am a purist when defining "debut." These are first books. They are not first YA books. I did not hold published short stories or poems against debut status, as long as the book on the "best of" list was the author's first novel. In other words, Alaya Dawn Johnson is not a debut author, despite The Summer Prince being her first YA book.

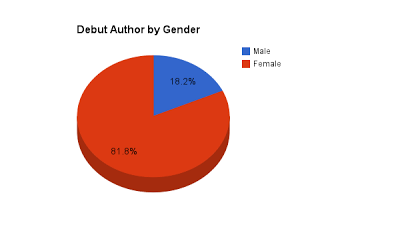

There were a total of 11 debut novels on the lists, making up 20% of the total. The other 44 novels were by authors who had previously published a novel.

There were a total of 11 debut novels on the lists, making up 20% of the total. The other 44 novels were by authors who had previously published a novel.

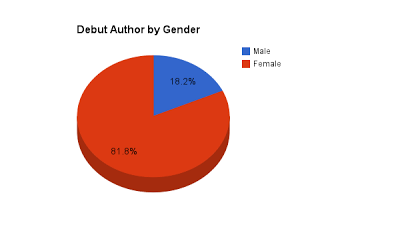

What about gender of the debut author?

Of the 11 debut authors, nine were female and two were male.

Of the 11 debut authors, nine were female and two were male.

Continuing to talk a bit about the debut novelists who made the list, how do the Morris Shortlist authors compare? Of the five books on the Morris list, three of those books saw themselves on any of the five "best of" lists: Carrie Mesrobian's Sex & Violence, which made both Kirkus and PW's "best of" list, In The Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat Winters made SLJ's list, and Evan Roskos's Dr. Bird's Advice for Sad Poets, which made the Kirkus list. That's more than half.

"Best Of" by Genre

It's tough to decide what book belongs in what genre. There are some which could go more than one way (especially when it comes to historical and fantasy, as some could go either way easily). Again, since I haven't read all of the books on this list, I had to pull some of my decisions from reviews, as well as from talking with those who have read the book. In short: decisions are subjective, but they're based on research.

I broke down my categories as broadly as possible. Thus, "realistic" is a category and not contemporary, for the sake of putting books like Eleanor & Park into what might be the best place for it to fit. I considered Far, Far Away to be fantasy, rather than paranormal, as I determined paranormal a category best suited for a story featuring a creature, rather than a spirit. I know it's a bit arbitrary.

Did one genre do better than another this year when it came to best of lists? Let's take a look.

Turns out that realistic fiction led other genres in "best of" lists this year. Out of a total of 55 books, 24 were realistic fiction. Historical had 13, with fantasy 10, science fiction 5, paranormal 2, and short stories 1.

Perhaps there's something to the suggestion there has been a growth in realistic fiction this year. This is something I may try to tackle in a series of posts next week about trends in 2014 fiction because I think it's better said there might be a rise in a certain type of realistic fiction coming up.

Books by "Best of" List Frequency

How many books saw themselves on more than one "best of" list this year? Even though the staff of the journals choose their titles by vote (usually), it's always curious to be to see what trends emerge in titles that appear more than once. Do those very early lists like School Library Journal's in November influence those which appear later? Or more realistically, do awards like the National Book Award or the Horn Book/Boston Globe Book Award put titles onto radars as possible "best of" picks? What influences what, if anything?

It's worth noting here -- and I'll repeat it again in the next posts -- that the journals each choose a different number of "best of" titles. And with my criteria listed in the beginning of this post to define "YA Fiction," the number of titles eligible shifted, too. Kirkus had 42 titles, School Library Journal had 13, LJ's "YA for Adults" had 3, Horn Book had 5, and Publishers Weekly had 16. Again, I'll come back to these totals in future posts.

Within the five lists, there were no books which appeared on all five. Only one book saw itself on four of the lists, and that was Eleanor & Park. It did not make the "Best YA for Adults" list by SLJ, though Rowell's other book, Fangirl, did make that list.

Within the five lists, there were no books which appeared on all five. Only one book saw itself on four of the lists, and that was Eleanor & Park. It did not make the "Best YA for Adults" list by SLJ, though Rowell's other book, Fangirl, did make that list.

There were five books which appeared on three lists, eleven books which appeared on two lists, and a total of thirty-eight books which appeared on one list.

The bulk of this year's "best of" titles only showed up on one list.

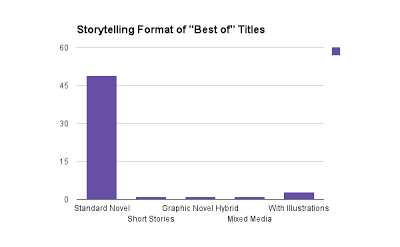

"Best of" Titles by Book Format

This year seemed to be the year of novels with a twist to their format, and I think that some of the data on the "best of" list reflects that. Though this, too, is interesting to compare to last year's list. Were there any verse novels this year? What about books told with a graphic-hybridization? What about sketches or illustrations that weren't quite at graphic novel style or what about those mixed media projects?

It's not surprising that standard novels made up the majority of format for storytelling. Forty-nine of the books on this list were your average novel (which isn't a means of degrading novels as "average," but rather suggesting they aren't doing anything noteworthy in format). There were three novels this year that included some kind of illustrative element to them that stood out, including Maggot Moon, Winger, and The War Within These Walls. There was on graphic novel hybrid with Chasing Shadows, one mixed media novel with In The Shadow of Blackbirds, and one short story collection, Midwinterblood.

There were no novels in verse represented this year.

Diversity and "Best Of" Lists

Two topics I wanted to look at within the "best of" lists included representation of LGBTQ and POC. Again, standard disclaimers that I haven't read all of these books, and I pulled data from my own research (as well as the linked-to blog post above from Malinda Lo).

First, let's talk about LGBTQ and the "best of" lists. How many stories featured characters whose sexuality was discussed or a major part of the book? I'm looking strictly at the books and stories, rather than authors, because it's challenging to make that determination and, I think, unfair to make it, too.

Five Books featured characters who identified as LGBTQ. These books were:

More Than This by Patrick NessThe Sin-Eater's Confession by Ilsa J. BickTwo Boys Kissing by David LevithanWinger by Andrew Smith (minor character)Zero Fade by Chris L. Terry

What about books written by or featuring people of color? This one is easier to make a determination of when it comes to author, so I'm breaking this town into two data sets: by author and by character in a book. Remember there are 55 authors and 62 main characters represented.

Authors who are POC on the "Best of" lists: 8. I did include Myers twice in the count, since he had two different books on the list.

Main characters who are POC on the "Best of" lists: 10, with one story featuring a secondary character who is a POC.

Those authors and books (some of which are written by a POC about a POC) are:

Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell Zero Fade by Chris L. TerryInvasion by Walter Dean Myers Golden Boy by Tara SullivanDeath, Dickinson, and the Demented Life of Frencie Garcia by Jenny Torres-SanchezDarius & Twig by Walter Dean Myers Champion by Marie LuThe Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn JohnsonThe Counterfeit Family of Vee Crawford-Wong by L Tam HowardA Moment Comes by Jennifer BradburyChasing Shadows by Swati AvasthiYaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass by Meg Medina

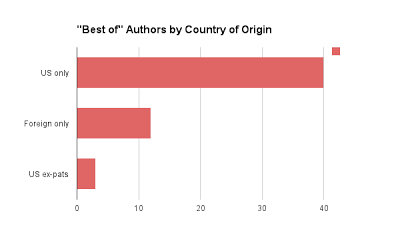

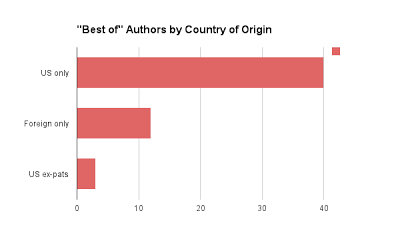

Country of Origin and "Best of" Lists

I wanted to round up today's post and data by looking at something I did not look at last year, which is the country of origin of the author. Do authors who aren't from the US fair well on our "best of" lists? Do they tend to do better than US authors?

I've got three categories for this data: US born and still living in the US; foreign born and foreign living; and I have a small number of US ex-pats. Here's the breakdown:

Of the 55 authors represented on the "best of" lists, 40 were from and still living in the US. A total of 12 were foreign born and foreign living, and three were born in the US and now living in a foreign country.

There's not anything to conclude with this information, but it's interesting to see there is a fair representation of non-US authors on the list. The bulk were located in the UK, Canada, and Australia.

***

Any thoughts on the data so far? Surprises? Non-surprises?

Tomorrow there will be another post, this time looking at a number of other factors, including date of publication for the books on the lists, the spread of publishers represented on the list, and more. I'll talk about the way this year's "best of" lists compare to last year's on Thursday, since there are some interesting trends in the books on these lists.

Even if no conclusions can be made, it is always fascinating to see what a year in books looks like and what it is we define as "the best" in a year (and it's equally or more fascinating to see what's not included).

Editing to add that Malinda Lo has some really great observation and commentary about LGBTQ as represented on this year's "Best of" lists. Go check it out.

Related StoriesNovember and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read PileGet Genrefied: Humor

Related StoriesNovember and December Debut YA NovelsThe To-Read PileGet Genrefied: Humor

This year, I wanted to look at a number of factors like I did last year, and it requires more than one post to do so. Because I still had all of my data from last year pulled into a single space (I did not in 2011, where all of my information was posted in another forum), I've written third post as well, comparing the data from last year against this year's. They will publish today, tomorrow, and on Thursday.

The "best of" lists I looked at this year are the same ones I analyzed last year: School Library Journal, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, Horn Book, and the Library Journal list of Best YA for Adults. I like to look at that last one, the YA for Adults, because I think it's worth keeping an eye on and comparing with the lists that are geared less toward adults -- are there crossover titles? Are there different titles completely? It adds another flavor to the data.

Because they come out a little bit later, I have not looked at the best of lists from Booklist nor BCCB, though it's possible I may look at them comparatively in the new year (BCCB's list comes out in January and Booklist's should be out this week, either prior to this post or after it). I limited what I looked at to YA fiction only. This means no graphic novels (though if you're curious, the graphic novels which made this combination of lists include Boxers and Saints, on all five of the lists; Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Lieutenant on two of the lists; Will & Whit on one of the lists; Romeo & Juliet on one of the lists; and March on one of the lists) and I did not include non-fiction titles (of which there were very few).

I made my determination on whether a book was a YA book or not based on the criteria that Amazon listed it as a book for those age 12 and older. This meant some books which have been debated as being "for YA readers or not," like Tom McNeal's Far, Far Away, were indeed included in my count. I did not include illustrators for books that feature graphic or illustrative elements in my author counts or breakdowns.

Though more relevant to tomorrow's post than today's, I pulled my information about starred reviews from ShelfTalker's last updated "The Stars So Far" post; since this was last updated in mid-November, it's possible some of these titles may have earned additional stars since then. Information about LGBTQ representation in these books was pulled from Malinda Lo's tallying, along with notes I've made to myself on the books I have read.

Before diving in, some caveats: none of this data means anything. I'm not trying to draw conclusions nor suggest certain things about the books that popped up on the "best of" lists. Errors here in terms of counts, in my decision to list a book as featuring a POC, in my tallying of MCs by gender, and so forth, are all my own. I have not read all of these books, so sometimes, I had to make an educated guess based on reviews I read. Tomorrow, I'll link to all of my raw data in the introduction.

There were a total of 55 books on these lists, 55 authors, and a total of 62 main characters, as some books were told through more than one point of view.

With that, let's see what there is to see in this year's "Best of YA" lists.

Gender Representation in the "Best of" Lists

First, let's look at gender and the "best of" lists. Do we have more male authors represented or do we have more female authors?

There were a total of 55 authors represented on all of the "best of lists," with 14 being male and 41 being female. In other words, roughly three-quarters of the authors this year were female, while one-quarter were male. This is a really interesting breakdown, considering that the breakdown by author gender on the New York Times Lists (in this post and this post) showed something different.

One of the comments I received on my New York Times post breakdowns was that it would be interesting to look at the main character genders in the books listed. Since I didn't look at that element in those posts, I thought I'd give it a shot with the "best of" lists this year.

As noted, there are more main characters than there are authors, so this is out of a total of 62 characters. Again, not having read all of the books, this is based on my best guesses having read through many reviews of the titles listed. I counted main characters as those who have a voice in the story. I did not include the Marcus Sedgwick book, since it is a collection of short stories and not having read it, making a call was impossible.