B.R. Sanders's Blog, page 25

June 25, 2015

A Typical Week

click image for source

I’m not a full-time writer. I don’t make my living off my books, and I don’t even wish I did.

I write fiction, but I also work full time. And I’m a parent. And I have two live in partners. And I have friends. And I have have to manage my mental health and physical disabilities*. And I have to, like, eat and sleep and exercise and stuff, too. And do errands and get groceries and feed my two cats. I also watch tv and read books and play video games, too, on occasion. And write this blog.

So. I have been asked before how all of the aforementioned things get done. The short answer is they don’t all get done all the time. Something usually gives. Maybe I get All The Things done, but I don’t get enough sleep that day. Or I manage to do the laundry, but I live out of the laundry basket for the next week.

The long answer is everything is juggled. I have juggled things so long, now, that they are routinized. Here is how it gets done (writing stuff is bolded):

A Typical Weekday:

Wake up at 5:30am

Walk to the bus stop at 6:00am; catch the 6:12am bus into Denver

Write on the bus on my morning commute. Usually I can get somewhere between 600-900 words down. I sometimes tweet about my adventures in writing on public transportation using the #BusWriting tag on twitter @B_R_Sanders if you’re interested in what that’s like.

7ish-8:30ish: work out and shower at the Downtown Denver YMCA

8:30ish-4:30ish: work at my day job

Catch a bus home (time varies) and do more #BusWriting (so another 600-900 words).

Get home, and hang out with the family. Post to any extraneous ongoing creative projects (currently, the Supernatural Haiku Project). Put the kiddo down around 8ish. Said kiddo likes to tell me absurd lies about her day (“Today I ate a tree.” “No you didn’t.” “Yes I did.”). Eventually, she falls asleep.

I turn in soon after to either watch a little TV by myself or read a book. I need a lot of sleep to function well, so usually I’m asleep by 8:30, 9:00pm.

On the Weekends:

There’s no rigid set schedule like the weekdays (man that’s regimented), but there are specific tasks I try very hard to get done every weekend–descending order of urgency:

Laundry

Grocery store run

Blog posts–I try to write the three that need to go up every week and queue them so I don’t have to worry about posting them at work the day of

Monday: Roundup of anything I did the week before that wasn’t on the blog

Tuesday: something vaguely reflective of what’s going on in other’s people’s work (book reviews, hot topics in the blogosphere, etc)

Thursday: something reflective of my own work (writing tips, why I wrote something the way I did, etc)

answer outstanding writing-related emails

editing any accepted work

update the family budget

resubmitting any rejected work

website updates as needed

So much juggling, but it works. It’s worked for the last few years, at least, and it’s evolved when it’s needed to. But this is how it all gets done (mostly).

*I have a history of depression, and I struggle daily with an anxiety disorder, such fun! It’s worse in the winter, since I have Seasonal Affective Disorder, and it’s complicated further by occasional bouts of gender dysphoria (I am trans*). All of these are related to my migraines, which are both mentally and physically debilitating and occur often multiple times a week.

June 23, 2015

Book Review: PANTOMIME

I have heard nothing but good things about Pantomime by Laura Lam, and the book earned every good word I heard about it. Pantomime tells the story of Micah Grey, who was once Iphigenia Laurus: an intersex teenager raised as a girl who runs away to the circus when her parents decide to surgically alter her to make her ‘marriageable’ against her will. Once on the run, Iphigenia takes the name Micah, passes herself off as a boy, and joins a circus. At the circus, Micah begins training as a replacement for the circus’ aging male acrobat.

Micah’s voice is beautifully written. Lam captures the confusion of adolescence, the way Micah’s gender and biological sex adds to that confusion and isolation, and the anger Micah feels when he realizes that being intersex shouldn’t isolate him from those around him but does. At the same time, Micah begins a relationship with female his acrobat partner, Aenea, while nursing a crush on the White Clown of the circus, Drystan. Micah’s burgeoning bisexuality provides another welcome thread of the book, which Lam handles with sensitivity and grace.

The circus itself is presented as a microcosm, a little world unto itself, full of history that Micah has to learn, and full of possible dangers as well as new experiences to explore. Micah endures hazing. Micah learns who in the circus to watch out for and who is safe. Meanwhile, news that Iphigenia Laurus has run away spreads through town. Some in the circus put the pieces together; some do not. Micah must learn who he can trust and who he cannot. Some learn his secrets, and he learns theirs. The theme of secrets—the power they hold, the destructive force they ultimately represent—is a present all throughout the book. That theme comes to a devastating, heart-wrenching set of climaxes at the end of the book.

Pantomime is fits squarely in the genre of fantasy. The worldbuilding is excellent and doled out in enough small doses to stay interesting without ever being overwhelming. Each chapters starts with an epigraph from some fictional work which provides some context about the Archipelago, the region in which Pantomime takes place. Micah’s past as Iphigenia gives him an education on Ellada’s (his country) history and political relationship with its outlying colonies. Slowly, Vestige is introduced—magical artifacts from some time long past which work sporadically. The circus uses them for entertainment value, but Ellada once used them as weaponry. Micah, for as yet unknown reasons, has a strange and powerful relationship with the remnants of the culture that produced the Vestige artifacts.

Honestly, if there’s anything to critique about Pantomime, perhaps, it’s that last point—by the end of the book, it’s increasingly clear that Micah is, in some mysterious way, special, and that this specialness is tied to his being intersex. This, I’m sure will get extrapolated in the book’s sequels, but I can’t help but think that the book would have been stronger, and would have made more of a positive statement about intersexuality, gender fluidity and bisexuality if Micah had just been…Micah. Not chosen, not magical, just Micah—an acrobat who is complicated and trying to grow up in a complicated world. But all that said, the book was still lovely, and I am very curious about the Penglass, so I’m already halfway through Shadowplay.

June 22, 2015

Roundup: June 15-June 21, 2015

I wrote down some thoughts about Charleston over on tumblr. And, please, donate what you can if you can to Emanuel AME Church.

A fresh round of Supernatural Haikus went up on my tumblr.

Writing Update:

The Search went from 57k words to 64k. Shayat might have a trans woman love interest, and Sorcha has a crush on a pirate captain.

June 18, 2015

Want To Have a Book Reviewed? Now You Can!

Do you have a fabulous indie book out there? Are you looking for reviewers? I’ve been there. I know how that goes. Maybe I can help! I’m officially opening up my doors and offering services as a indie book reviewer. Below is an official book review policy and a form for contacting me with review requests.

Note that requests that follow the review process and which are submitted properly through the request form have the best chance of getting a response back!

B’s Book Review Policy

I’m always open to genre fiction (science fiction and fantasy), diverse literary fiction (protagonists of color, protagonists with disabilities, etc), and queer fiction of any stripe.

I am particularly interested in reading:

queer genre fiction

trans* narratives

neuro-atypical protagonists

fabulous secondary world fantasy

feminist genre fiction

Won’t read:

Middle grade fiction or children’s books

Christian fiction

I prefer eARCs or ebooks in Kindle (mobi) or epub formats.

How Does This Work?

Request A Review

Request A Review

June 16, 2015

Book Review: DERVISHES

Dervishes by Neal Starkman seems to be equal parts beat novel, radical feminist ethnography, and discarded Woody Allen script with a dash of someones’ physics dissertation thrown in as a garnish. It had a decidedly John Barth-esque quality to it.

The book is structured as the diary of a one Carolyn Anderson: assistant physics professor in Seattle currently facing a crisis in her professional life when her research funding dries up. Carolyn, in a fit of teenage cheekiness, dubs her diary “Lady Di.” The entries are conversational; an ongoing back and forth between Carolyn and her silent foil. Lady Di is a good listener and gives Carolyn the space to dig up her old war wounds. At the time she starts diarizing, Carolyn identifies as a lesbian, but she uses much of her diary to excavate her relationship with Philip Lester, a former lover with whom she never quite got the closure she needed.

In the mode of Woody Allen, the book tries to weave together philsophizing and blase comedy. Sometimes, as with an anecdote about a wayward crab on a beach excursion that starts horrifying and ends bittersweet and funny and revealing a humanity about Philip I didn’t think would ever get revealed, it works marvelously. Sometimes it doesn’t. Always, it’s ambitious.

The philosophical questions that the book wrestles with—that Carolyn and Philip and Carolyn’s current lover, Stephanie, wrestle with—are largely questions of identity and authenticity. To what extent, Philip asks, can one be truly authentic when one pins one’s identity on the prattle of others? If you say ‘I am X’ (a lesbian, a feminist, a socialist, a professor) to define yourself, and take on the trappings of that group, then you buy yourself some comfort from thinking. You buy yourself an in-group. But what is the cost of that?

Carolyn’s current lover, Stephanie, is a radical lesbian, and she veers the other direction. For her, everything is the movement, the community. If you are not fully bought into that, Stephanie seems to feel, then what’s the point? What are you contributing?

Carolyn spends the book spinning between these two extremes. And they are extremes, each as equally misinformed as the other. Philip’s myopia about groups and affiliation leaves him more and more isolated. His insistence that he might be a man, sure, but his refusal to engage with what having been raised as a man and what living in the world as once means drives a wedge between him and his beloved Carolyn as she develops more and more of a feminist consciousness. Stephanie, on the other hand, takes things as given which should not always be taken as givens, and her reluctance to ask questions leaves Carolyn suspicious.

This is, all in all, a curious book. I love that it’s voice is Carolyn’s—a lesbian scientist, someone who is not perfect and does not pretend to be, someone who struggles and questions herself and those around her. But I wish that Carolyn herself had been more front and center. She too often faded into the background for me; though it’s her book, her story, and her diary, it often felt like she was reporting on what other people did around her. And in specific, though she was a lesbian, much of the text was devoted to the autopsy of her relationship with Philip, poor doomed misanthropic unlikable Philip, who all too slowly mansplains his way right out of her life.

Some of this can be attributed to Carolyn herself, perhaps. Maybe she perceived herself to be more passive than she really was. It’s her diary, after all, and there is room to interpret her as an unreliable narrator. But that could also be wishful thinking on my part. I wanted her to take her life by its reins. She does so at the end, but over and over we watch, as ‘Lady Di’, trapped as this brilliant woman (she has a doctorate in physics, come on) gets pushed and pulled this way and that. Her inner monologue as it’s poured out to her diary is acerbic and sharp. I wanted her actions to be as acerbic, as sharp.

But, still, there’s much in the book worth liking. The characters are well drawn—though I would’ve liked more time with Stephanie to have fleshed her character out more. Generally I am wary of men writing from women’s perspectives, but Starkman was a pleasant surprise. Carolyn felt authentic to me.

June 15, 2015

Roundup: June 8-June 14, 2015

A fresh round of Supernatural Haikus went up on my tumblr.

Writing Update:

The Search went from 53k to 57k this week. Sorcha got a plot-relevant makeover.

June 10, 2015

Advice to New Writers: First, You Have To Finish It

In my interview with Prism Book Alliance, I was asked to give new and aspiring writers a piece of advice. The advice I gave was this:

In my interview with Prism Book Alliance, I was asked to give new and aspiring writers a piece of advice. The advice I gave was this:

Finish things. When you’re starting to write, it’s really easy to get insecure and to hate your writing and to psych yourself out. It’s really easy to start things but not finish things. But you have to finish things. If you don’t finish the things you start, then you won’t learn how to craft a narrative. You won’t learn how to push through that crappy first draft and turn off that critical editor voice until the second draft. Remember, you can’t publish something that isn’t finished. You have to learn to finish things.

I thought I’d take today’s post to expand on this advice. The funny thing about the way I got into writing fiction is that I started writing to help someone else finish what they started. Basically everything set in the universe of Aerdh–from “The Other Side of Town” to Ariah–can be traced back to that. My partner, Jon, was dabbling in fiction, and I liked what he was writing, but he wasn’t finishing it. So I stepped in to help. I became the finisher. And over time, I ended up doing all the writing.

Not finishing what you start is a form of self-rejection. It’s a way of letting your fear that you’r not a good writer prevent you from doing the work that will actually make you a good writer. The truth of the matter is that when you’re just starting out it probably isn’t good. And that’s ok. The trick is to finish it anyway. You won’t ever get better unless you keep at it. It’s a matter of practice, of building skills. And one of the main skills you need to build is learning to craft a complete story: a beginning, a middle, and an end. But if you never finish anything, how will you learn to craft an ending?

Many of my friends who have dabbled in fiction but who have not really made a go of it suffer from starting-but-not-finishing syndrome. Either they start a handful of things when inspiration strikes and bail on the stories at the first sign of trouble, or they have been fastidiously tinkering with the same novel year in and year out.

In the first case, this won’t lead to growth as a writer because there’s no diligence. Writing is a craft, and should be treated as such. It’s a set of skills, and if you really want to grow as a writer, you should approach it as a set of tools you want to sharpen and hone. The myth of the muse dropping into your lap, hypnotizing you into feverishly churning out an opus is just that: a myth. This is a way of trying to avoid that there’s the actual work of writing in being a writer. Forcing yourself to finish things, even when it’s a slog, will give you the grit needed to get the work done.

In the second case, you’re not growing as a writer because you’re trying to write and edit at the same time. Do one, then the other. Stop trying to fine tune your first draft before you’ve finished writing it. But that can be hard to do when you’ve tinkered with it for years! By then, you’ve invested so much time and energy that finishing it feels huge and overwhelming. Take the finishing part in pieces. Maybe write the ending and work backwards. But finish it first, then start tweaking it again. Otherwise, you’re just stalling, which is another form of self-rejection. Better yet, finish it, send it to a beta reader, then tweak it per the beta reader’s feedback. But finishing it is key.

June 9, 2015

Snow Blindness: A Follow-Up To Nicola Griffith’s Analysis of Book Award Demographics

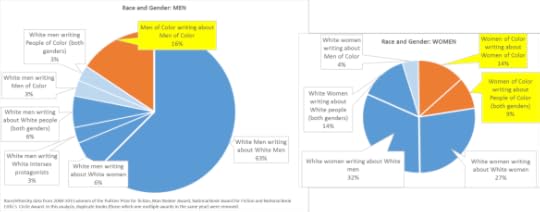

I think I’ve mentioned it here before, but by training I’m a statistician. I don’t live off my writing, and in my day job, I work as an analyst for a large urban school district crunching numbers. Back in grad school, I taught stats to undergrads who would really rather be anywhere else, bu I like stats. Always have. So I read Nicola Griffith’s post “Books About Women Don’t Win Big Awards: Some Data” with great interest. The first thing I thought of when I read is was I bet this replicates with other marginalized identities. I bet it’s not just gender; I bet it’s race and sexuality and class and everything else, too.

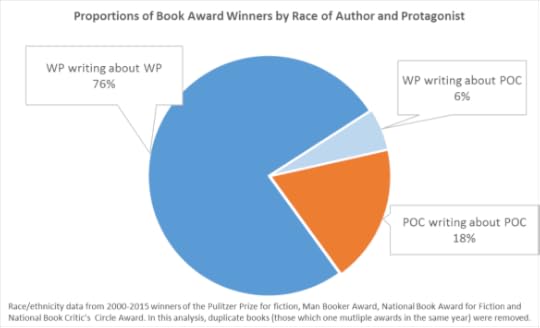

I had some time this weekend. Not much, but enough to do a little digging. I did what she did–mostly–but for race. I looked at four out of the the six prizes she looked at* for the same time span she looked at (2000-2015) and coded whether the author was White or a Person of Color. I dug up what I could on the book in question to try and figure out, if I hadn’t read it (and I hadn’t read most of them), if the protagonist(s) was White or a Person of Color**. And then I crunched some numbers. Here’s what I found:

Lit awards are exactly what you would guess: blindingly White, White as the purest arctic snow. Generally, over 80% of Pulitzer, Man Booker, National Book Award or NBCC prizes went to White writers.

Also, unsurprisingly, intersectionality matters. When you look at both race and gender, that arctic snow is full of dicks. Big, pasty dicks. Women of color and men of color made up 9% of the award winners apiece. White men were five times more likely to win an award than people of color. White women were three times more likely to win an award than people of color.

Griffith found that even when women writers do manage to win a prestigious award, they tend to do so when they’ve writer about men. Race in writing seems to be of a more peculiar character:

Writers of Color, the ones who won these awards at least, wrote exclusively about People of Color. Who knows; maybe they were bored of the absolute blinding whiteness of the narratives they see day in and day out and felt no compunction to contribute to that.

White writers mostly wrote about other white people, but a few broke the mold and wrote about People of Color and were awarded (probably by a panel of White people) for it.

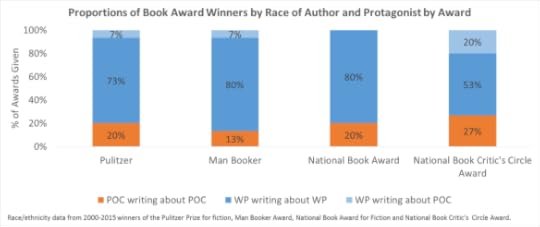

That’s the high-level TL;DR summary, there. I’m going to roll up my sleeves now and dig into the data now. Stick around if you’d like! To start, here are the four awards I looked at:

POC=People of Color

WP=White people

You can see that the trends are remarkably consistent across the awards. The NBCC is the only one coming close to bucking that trend–NBCC was more likely to give the award to POC authors and to books featuring POC protagonists written by White authors. The Man Booker Prize, on the other hand, was the most blindingly White of the bunch. This mirrors quite closely what Griffith found with regard to gender: Man Booker had the highest number of awards given to men who wrote about men, and NBCC gave a relatively wider spread of awards to men and women writing about men and women.

The pie chart above collapses all the awards I surveyed across the award giving body to get an aggregate sense of race trends. There are two main points of interest here: first, that over 80% of awards for the last 15 years of these four major awards have gone to White writers. 80%–FOUR FIFTHS.

The second point of interest is that the flexibility of writing gender that Griffith found–men writing women, women writing men–isn’t present to the same extent here. Some White people are writing People of Color, but People of Color are interested in writing their own narratives, not adding to the already bloated collection of White narratives. And yet, the preponderance of awards are still going to White narratives written by White people–or narratives of color written by White people.

note that the women author’s pie graph is smaller. That’s on purpose: men (regardless of race) won 60% of the awards in the time span looked at.

For my final trick, I overlayed Griffith’s analysis and my own. I coded my set of data for both race and gender of both the author and the book’s protagonist to see how the two pieces of demographic data interacted (because, you know, intersectionality matters).

The graphs above split out the combination of the author’s race and gender and their book’s protagonists’s race and gender. The graph on the left shows the proportions for the men winners (60% of the dataset). The graph on the right shows the proportions for the women winners (40% of the dataset). What the above data tells me is that White men write about anything and everything and get awards for it. Mostly they write about other White men, yes, but they are the ones crossing gender and race lines most in their writing and get awarded for it.

I would have liked to do more. I wanted to add sexuality into the mix, but it was very hard to determine author’s LGBTQ status with just a cursory internet search. Only two of the winning books, Middlesex and The Line of Beauty, were book that I knew dealt with LGBTQ themes. I would expect similar patterns to emerge should that data become available, though.

*Griffith also looked at the Hugo Award and the Newberry Medal. I excluded these from my analysis due to time constraints which is a fancy way of saying ‘then I had to give my kid a bath.’

**There were some cases, like The Road, where movie adaptations of an arguably non-race-identified protagonist was cast as White, which I then used as essentially canon evidence of Whiteness.

June 8, 2015

Roundup: June 1-June 7 2015

A fresh round of Supernatural Haikus went up on my tumblr.

Writing Update:

The Search crept up from 50k to 53k this week. Shayat killed a man and took his house.

June 4, 2015

Dissecting ARIAH’s Opening Paragraph

Every couple of months, a new listicle pops up on my Facebook or Twitter feed rounding up the greatest opening lines in literature. Or there’s pitchmases. Or there are improve-your-writing articles about landing an agent by sharpening your opening sentences. Obviously the start of a story is important. I think, on that, we can all agree. Today I thought I’d walk you through the evolution of some of my opening lines.

This is the opening paragraph of my second novel, Ariah, which was released last week:

There are times I still have nightmares about that first day in Rabatha. I’d come from Ardijan, which is a small place built around the river and the factories. It’s a town that is mostly inhabited by the elves who work the factories with a smattering of Qin foremen and administrators. We outnumber them there. We’re still poor and overworked, we still get hassled, but there is a comfort in numbers. It was a comfort so deeply bred in me that stepping off the train in Rabatha was a harrowing experience. The train, a loud, violent thing that cloaked half the city in steam, plowed right into the center of the city and dropped me off only three streets away from the palace. Even with all the steam, I could see its spires and domes. Even with all the commotion, I could hear the barked orders and vicious slurs of the Qin enforcement agents.

In order to craft successful opening lines, you may need to take a step back and consider what you want them to do. This is your first interaction with your reader. These sentences have to set your tone, kick off your plot, introduce your setting and your characters—any number of things. Choose wisely. In the case of Ariah, I really needed to emphasize:

The story is told in retrospect

Ariah’s deep emotional sensitivity (he still has nightmares)

Ariah is an elf, which is an oppressed class in this world (there are slurs thrown at him when he arrives)

Create a sense of urgency and chaos in the reader

Ok, compare that to the opening of the first draft of Ariah*:

I honestly had no idea what to expect that day. I suppose that’s how most feel, though, when they first meet those who are supposed to take them on as apprentices. Then again, usually it’s already someone you know – someone from your town, someone that runs in the same circles with your parents. The kind of person whose children you played with growing up. So most probably at least knew what they were getting into. I didn’t. I was shipped off to the capital, a strange bustling city I’d never been to before, and told to go see someone whose name I’d only ever seen on the spines of books in my mother’s study. All I really knew was that I was terribly nervous. What if he didn’t like me? Would it be worse if he took me on as a pupil anyway or refused my parents’ request? What if I didn’t like him?

Clearly I rewrote this, which means I don’t think it’s that strong. I think this opening lacks urgency—it’s meandering where it should be gripping. It’s thoughtful where it should have some force to it. It’s more focused on Ariah’s unnamed mentor than on Ariah himself. It’s shot through with telling instead of showing: he says he’s nervous, but we, as readers, don’t feel that nervousness. We are not immersed in a situation that makes us feel nervous with him.

Most of my openings start like this in the first draft—bland, telling without the showing. They usually drastically improve in revisions. Often, simply because in the second draft I actually know the story I’m telling. For example, one reason the first draft opening is written about the mentor is because the story was originally supposed to be about the mentor. Ariah was only supposed to be a viewpoint character reflecting on the mentor, but then Ariah took on a life of his own and took over the narrative. He went rogue, and the opening lines became an artifact of a story that was never actually written.

In my writing, the opening lines of first drafts get written first—sloppily—simply because you have to write something. You have to start somewhere. The rest of the draft comes together, the writing tightens up as it does, you find your voice somewhere in the middle and get a cadence. By the end of the first draft you finally have figured out what the story is about. Then, you start rewriting. You fiddle with the first part, and you rewrite, and you rewrite, but those opening lines are actually the last thing to get seriously tweaked and polished precisely because they are the first thing everyone will actually see. Those lines are high-stakes, which makes them intimidating as shit, so you hold them off and perfect everything else, then you perfect them.

I am generally not a critical self-editor, except when it comes to the first paragraph and the last paragraph, these make-or-break-a-book lines. These are the ones that have to be just right. These are also the ones, though, that can be killed by too much fussing. You have to let them breathe; you have to resist the urge to over-write them. You have to trust your gut that you’ve finished them and done them as well as you have it in you to do them. You have to stop yourself from fiddling with them forever to stave off the terror of putting your work out there.

*Oh, man, showing you parts of a first draft is like showing you my messy bedroom. I know everyone has one, but it doesn’t make it any less embarrassing.