B.R. Sanders's Blog, page 23

August 3, 2015

Roundup: July 27-August 1, 2015

probably what I’ll have carved on my tombstone

Wanderings on the Internet

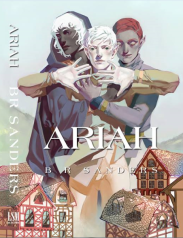

Well, definitely the highlight of my week was the very high praise Ariah garnered over on Twitter.

“The Fisher’s Son,” is still free to read over at Inkitt. And you can still vote for it in Inkitt’s Hither and Thither contest!

If you are so inclined, browse the Supernatural Haikus.

Writing Update

Another short story in the can! This one is called “The Sharpshooter” and features a genderqueer gunslinger in an Old West carnival with a magical pistol.

1,500 more words went into The Search, too, which brings us up to 83K total so far. Sorcha and Shayat have been reunited after a separation. Both have some secrets to reveal to the other.

July 31, 2015

Book Review: SHADOWSHAPER

Shadowshaper by Daniel Jose Older is a triumph. It is a seamless and engaging YA urban fantasy that feels real and immediate and urgent. Sierra Santiago, the main character, is a revelation: an Afro-Latina with agency, with consciousness, replete with unrelenting badassery. The pacing never stops. The prose never hitches. And the cover is gorgeous. I literally have nothing bad to say about this book.

Shadowshaper follows Sierra, a burgeoning muralist in Brooklyn, as she discovers that she is part of a line of spiritual artists called shadowshapers—and that the other shadowshapers are getting hunted down and murdered. With the help of Robbie, her classmate and fellow emerging muralist, she has to uncover who is hunting the shadowshapers and put a stop to it.

Everything that follows is gold, from her clever interludes with her godfather Neville, who uses the racist assumptions society holds against Black men to his advantage to help her infiltrate Columbia, to Sierra’s realization that it is, ultimately, it was her Puerto Rican grandfather’s machismo that kept her from knowing her own power for so long. This book is steeped in race and gender; Older never flinches and never shies away from portraying the ways in which these axes of oppression shape his characters’ lives. For young readers of color, especially girls of color who yearn to see their experiences acknowledged in literature, this will be powerful1. As a queer reader, I loved that Older included right at the start a pair of lesbians in Sierra’s friend group. Tee and Izzy were just there, just hanging out, treated as normal. It made me feel safe in his world.

The worldbuilding is lovely, and its supported by Older’s ability to highly visual storytelling style. His prose is extremely sensual—there is a scene which takes place in a Haitian night club that succeeds on the strength of his ability to evoke the richness of the mural in the club and the way the mural shimmers and shifts with the music played by the nightclub’s live band. It’s a strong demand of the written word to make you see that mural, to hear that music, to see the relationship between those two things, but Older pulls it off. He employs that device over and over through the course of the book, which is why Shadowshaper is so immersive and rich: it’s a five-sense experience as you read it because it’s so fascinated with so many different kinds of art.

Shadowshaper, like all my favorite spec fic books, is political, too. It has a lot to say about whiteness and white supremacy. Ultimately what Sierra is fighting against is gentrification, appropriation, white entitlement. I won’t spoil it, but I read the book and I read Sierra as a statement about the importance of communities of color banding together to preserve themselves and their culture from sublimation into the maw of Whiteness. There is a scene, fairly early in the book, where Sierra and her friends go to a coffee shop that has appeared in their neighborhood only to find that it’s overpriced and full of white hipsters. At first, they make fun of it. But then:

It looked like a late-night frat party had just let out; she was getting funny stares from all sides—as if she was the out-of-place one, she thought.

And then, sadly, she realized she was the out-of-place one.

Looking back from the end of the book, this scene is eerie in its foreshadowing of Sierra will fight against.

1I CANNOT WAIT until my partner Sam reads this book. Sam is Latina and has talked to me at length about how hard it was for her to find things to read as a kid growing up and how much she disliked the Old Dead White Dude Canon that was pushed on her in English classes. This is exactly the kind of book that she will love and that she should have been able to find as a kid in a school library, and I sincerely hope that Shadowshaper finds its way onto middle school and high school English curricula for that reason.

July 30, 2015

Publication Announcement: “The Scaper’s Muse” in Glitterwolf #9

“The Scaper’s Muse” is included in Glitterwolf #9: The Gender Issue (available for purchase here)

Through bad luck and circumstance, Gavin Camayo is very politely exiled to an alien planet. But Stahvi is a fascinating place, and his stipend keeps coming from the corporation back home, so Gavin doesn’t mind the exile so much. There’s plenty of strange wonders around to keep him amused. But what happens when a familiar wonder—the person who lands him in exile in the first place—appears on Stahvi, too?

“The Scaper’s Muse” is a science fiction short story about the interplay between identity and vanity set in an alien landscape.

July 29, 2015

Thanks for the ships, Melville!

click through for source

Despite my landlubber life, I’ve always had a fascination with books about the sea. Maybe that’s part of why I love Melville so much.

It’s not surprising, then, that one of the earliest inventions of the world of Aerdh were the pirates. I’m certainly not the first person to write about a spec fic pirate society, and I won’t be the last. The pirates of Aerdh figure heavily in the plot of The Search, the follow-up to Ariah that I’m currently writing.

For someone who loves worldbuilding, pirates are inherently fascinating. What does it mean to create a society that is inherently a society of outcasts? What sort of mores do they hold? For a society to survive, it has to last more than a generation, which means that children must be born and raised into it. What are the people indigenous to that way of life like? How do they see the world? How do they justify that their culture is, by definition, parasitic–for them to prosper, they must prey on other cultures. And what about the economies that spring up in the pirates’ wake? What are the moral grey zones there?

I’ve written about the pirates before, most notably in Cargo. One of the major secondary characters in The Search is a pirate king–defining the scope of his influence and how he wields it is enlightening. The Search is building out pirate culture above and beyond what was seen in Cargo, and I’m having a wonderful time exploring it.

Beyond the idea of the pirates themselves, with their potential for outlaw justice and redemptive arcs and sanctuary for marginalized individuals, there are the ships. Melville, in his books, used the microcosm that is life on a ship to great effect. I think I was always taken with that, with the way that ship life pens you in with a very limited number of people in a very proscribed amount of space. Ships are truly tiny little worlds of their own drifting through the maw of pure natural force.

Such a strange thing, and such a raw thing, and how could you not then forge such deep relationships with your crew? How could they not become your family? No one ever has neutral feelings about family. You only ever love them dearly or hate the sight of your family. Imagine spending all that time working a ship with someone you can’t stand, who annoys the shit out of you, but you know your life is basically in their hands. It’s maddening. The psychology of ships is insane. So, I keep coming back to them in my writing.

Want posts like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for my newsletter!

July 27, 2015

Roundup: June 20-26, 2015

Wanderings on the Internet

One of my short stories, “The Fisher’s Son,” is free to read over at Inkitt. It’s also entered in Inkitt’s Hither and Thither contest–if you like it, review it or vote for it!

If you missed the #RealDiversityMatters convo on twitter, I summed up my engagement with it in this handy Storify! The voices of marginalized people in the workplace matter, yo.

Last night I was honored and grateful to be included in the #WeNeedDiverseBlogs twitter chat that focused on reading and reviewing diverse literature. Nicole Brinkley hosted and did a lovely roundup Storify if you missed it and want to catch up! FYI: the next chat is scheduled for 8/16.

Check a fresh new batch of Supernatural Haikus.

Writing Update

I hit a major plot point in The Search last week that bears more thinking about, so it’s percolating in my subconscious for a week or so. I turned my attentions to a couple of calls for submissions I’ve been meaning to write for instead:

I wrote a 4k word short story this week called “The Adviser and the Diplomat” about to trans* political dynamos causing a lot of political upheaval as a matter of personal survival.

I planned out a sci fi story for another call that will feature redwood trees very prominently. I think it will be super cool. Stay tuned for that one! Once it’s in the bag I’ll go back to The Search.

July 24, 2015

Book Review: REDBURN

I would be lying if I didn’t admit that I am a Melville nerd. I am a big enough Melville nerd that I have the last line of “Bartleby the Scrivener” tattooed on my arm. I am a big enough nerd that reading Moby Dick wasn’t enough for me–I followed it up with Redburn.

Here’s the thing: Redburn is an early effort that’s passable in its own right, but really doesn’t prepare you for the genius gamechanger it’s laying the groundwork for. You just don’t see anything like Moby Dick coming based on Redburn. Which is not to say Redburn isn’t a good book, or an enjoyable one, or one worth reading (especially if you, like me, are struck with an incredibly geeky urge to go all completionist and read everything Melville wrote). But it does mean that reading Redburn after reading Melville’s legitimately more famous and better-regarded books is a peculiar experience.

To just take the book on its own terms, devoid of context or history or knowledge of what comes after, Redburn is at its heart a tale of a boy just coming to terms with the fact that his view of the world, and in particular his understanding of it as a fair and just place, has been shattered. It’s a pretty standard story of innocence lost and adulthood gained, told in hindsight by an older version of Wellingborough Redburn himself (and isn’t that a hell of a name?*) who seems slightly embarassed at just how naive he was way back in the day. This theme is nested throughout the book, starting with the economic collapse of his father to the inherent unfairness of life on the sea, to the inherent unfairness of poverty he’s first exposed to in Liverpool. The scope of the book gradually grows, like going from the innermost matroushka doll to the outermost one, which is a neat little trick on Melville’s part and rings very true for anyone who’s grappled with forging his or her own worldview in adolescence.

And the writing is lovely. Here, like in Moby Dick or “Bartleby,” Melville is telling you a story through someone else telling you a story. And one thing that keeps me coming back to Melville time and again is just that: that he tells you a story. The writing here is intimate and immediate, like you’re sitting in a comfortably overstuffed armchair with Redburn and he’s recounting his youthful exploits to you — just you — over a cup of tea. In fact, it’s a little bit purer here in Redburn than in anything else I’ve read by him. It’s got more scope than “Bartleby” by virtue of its length alone and unlike Moby Dick, where Ishmael himself starts to fade in and out of the narrative, Redburn is always front and center. It’s Redburn telling Redburn’s story (as opposed to the rather elderly gentleman telling you about Bartleby or Ishmael telling you about the Pequod) and Redburn, luckily, has the wit and grace as a reflective narrator to carry it.

But if I’m being honest, I think the only people who would be willing to read Redburn and enjoy it are people like me who have already signed on for the Herman Melville Experience once and don’t mind coming back for more. And since that’s the case, the truth of the matter is that Redburn is most interesting to read in the context of Melville more broadly. In Redburn, you see what is essentially the first pass at themes and archetypes Melville will use to much greater and deeper effect later on. In particular, Jackson reads like a more malicious and less conflicted version of Claggart. And Redburn himself reads as a terribly naive and less observant version of Ishmael. Perhaps Ishmael ten or fifteen years before he set foot on the Pequod. Redburn, like Ishamel, is more educated and more refined than the others on his boat, and Redburn (like Ishmael) finds himself falling into very close, very fast (and very homoerotic) friendships with foreigners as soon as he gets the chance. As in Benito Cereno, Melville’s ambivalence towards America — its grandeur built on foundations of injustice, its insularity, its conformity that can (as far as Melville seems to be aware) only be escaped by shipping out to sea — becomes a dominant theme.

And more than that, Redburn gives a great deal of insight into Melville himself. If Ishmael is more or less an idealized version of Melville, Redburn is clearly who Melville thought he once was. The parallels between Redburn and Melville are striking (so striking that my copy of Redburn has an appendix which notes chapter by chapter aspects of Melville’s own first voyage that he fictionalized for the book). Redburn is a book about a young man whose education and experiences lead him to sea totally unprepared, one who has to adapt without any clear guidance, and who in the process finds life at sea both utterly freeing and constraining, and really that young man is Herman Melville and not Wellingborough Redburn. It’s not so surprising, then, that Melville was dismissive of Redburn. He wrote it fast and wrote it for the money and frankly, you can tell. It’s an overly long, highly digressive travelogue of a book where you find yourself sifting through random chapters about churches in Liverpool and Redburn’s father’s unusable guidebook before Melville eventually gets around to anything resembling a plot again. This technique works a lot better in Moby Dick, but even there people find it annoying.

But I can’t help but wonder if he was dismissive of it because it was a little exposing to him, too. Writing it that fast perhaps meant that it’s more raw, more reflective of parts of himself he wasn’t fond of, and when all is said and done that’s what will stick with me most about this book.

* His name, despite what the back cover of my Penguin Classics edition of the book would have you believe, is actually Wellingborough Redburn and not Wellington Redburn. Shame on you, Penguin Classics, shame on you.

July 22, 2015

Advice to New Writers: Remember To Add Conflict!

click through for source

The Garden of Eden only got interesting when Eve at that apple.

The Awl recently ran an lovely piece interrogating why utopian novels are, by and large, not all that readable. Noah Berlatsky cites a number of reasons in his analysis, but really it comes down to this: narratives need conflict, and utopias, by definition, don’t have substantial enough conflicts to keep us interested as readers. There are no real problems in these worlds; there is nothing to overcome. And, therefore, there is nothing for the reader to root for or relate to. It’s purely aspirational.

Utopias also echo a common weakness in the stories of new writers. Here’s an example from my own writing: I wrote a story1 where the beats were largely as follows:

boy and best friend go to a bar

boy watches best friend make his rounds; boy winds up playing bartender

boy gets hit on and gently passes on another boy

boy goes home alone, feeling fine with his life choices

Ok, in retrospect, that’s…not actually an interesting story. It’s not even a story. There were some nice moments in it, and some good turns of phrase, but on rereading it a year or so later I kept waiting for something to happen. For anything to happen. Like, why was I writing this night of this kid’s life? It was just a night, any night, a purely unremarkable night. There was no conflict. There was nothing driving the story.

This doesn’t mean that your protagonist has to Go On A Quest for there to be conflict. Conflict can be mined from everyday interactions. Here’s another story of mine2, written around the same time, featuring the same character, which actually does have a conflict and a resolution and this is an actual story:

girl and boy start hanging out

girl likes boy, doesn’t know if boy likes her back

girl kisses this boy. He giggles like a mad man. She is embarrassed.

boy gets his shit together and writes her a poem because he does actually like her back

girl and boy are happily for now

See? It’s not a grand, sweeping, world-altering conflict, but it’s a conflict! She is unsure! She took a risk! She doesn’t know what will happen! There is uncertainty! those are all signs of a conflict.

The truth is that if your story doesn’t have a conflict driving its characters forward, no matter how pretty your language is, your reader will probably disengage. A story without a conflict is essentially a story without a plot.

Want posts like this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for my newsletter!

1This story will probably never see the light of day, and we’re all better for it, trust me.

2While this story is marginally better than The One With No Conflict, you really don’t want to read this one either.

July 20, 2015

Roundup: June 13-19, 2015

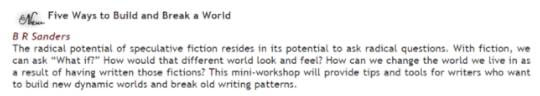

click through for full Sirens conference listing

Wanderings on the Internet

Are you going to be at Sirens Con 15? I am, and I’ll be presenting! That’s my session up there. It’s on worldbuilding.

Check a fresh new batch of Supernatural Haikus.

Writing Update

#BusWriting proved especially productive this week: The Search grew from 76k words to 82k words! Shayat and Sorcha are now entering a whole new section of the book.

July 18, 2015

Book Review: ESTRANGED

FTC disclosure: I received a free digital copy of this book in exchange for an honest and unbiased review.

Alex Fedyr’s debut novel, Estranged is a resilient and unexpected genre-bender of a book. It’s as much steeped in crime thrillers as it is paranormal horror. It’s half-zombie and half-vampire. Though Estranged suffers from a few problems that, I think, might be debut-author missteps, on the whole the book is a solid effort.

Kalei Distrad is a cop in Celan, where she works clean up on Estranged attack sites. The Estranged can kill Untouched people with a brush of skin-to-skin contact, and Kalei lost her parents to them. All she wants is to become a Warden—a member of SWORDE, the front line against the Estranged. That’s who Kalei is when we first meet her. By the end of the first chapter, Kalei is someone completely, wholly different. By the end of the book, Kalei is reincarnated one over again.

Suffice to say Fedyr keeps the plot moving. Plot and pacing are used to excellent effect; Fedyr juggles multiple plot arcs, each well-paced, each unifying at the end of the book to good effect. There was one major twist I felt was unbelievable1, but otherwise, each twist was satisfying and surprising.

The Estranged themselves are innovative, interesting horror creatures: Fedyr takes elements from both zombies and vampires, but makes them something else entirely. Like most monsters, the Estranged are posited to interrogate something about human nature, and the Estranged raise a host of questions about addiction. Anyone who has struggled with addiction or has lived with or loved someone who has dealt with addiction will engage with this book on a whole deeper level; I know I did. The complexities of addiction are on display here, most especially that addicts are still people, even in the throes of their addiction, even when it makes them do terrible things, and while that doesn’t absolve what they do it does complicate what it means to be human.

Some of that lovely nuance gets lost in spots where Fedyr’s choices as an author distract from the plot and the characters. For example, I was confused by two characters with almost exactly the same name who are allies to Kalei (hint: Mar and Marley are not the same person). A more problematic example is the use of what reads like feigned African American Vernacular English (AAVE) to code at least one White character as sketchy and low class. Later in the book, this character essentially code-switches between AAVE and Standard English. Given that this character is White, this is deeply appropriative of Black culture, and the character traits Fedyr was trying to communicate to the reader about this character using code-switching and AAVE to begin with were not necessarily positive. I am a White reader, but there is a good chance that a reader of color, especially a Black reader, could see this as a major race fail.

In sum, Estranged is an engaging and thoughtful horror novel, and a solid first effort from Fedyr albeit with some missteps. It ends with a chilling cliffhanger, and I hope Fedyr is writing a sequel so I can see what happens next!

1To my point about Estranged being a debut book, this particular plot twist would have flown better with more foreshadowing and groundwork laid earlier in the book.

July 15, 2015

Sex as Worldbuilding

A couple of days ago, I read Karin Kross’s recap of the Sex and Science Fiction panel that happened at SDCC. From Karin’s recap, it sounds like the panel was equal parts thoughtful1 and irritating2. In any case, the recap got me thinking about the role sex plays in my own writing.

Just narrowing the scope of this post to sex, the act itself, and how that has occurred in my fiction, I’ve tried to explore it in ways that mirror the way sex is used  in the real world. Which, yes, often sex is an expression of love. Or desire. But many times, sex is divorced from both of those things: it can be used as a weapon (either literallyy or figuratively). It can be used transactionally, economically. Sometimes these uses blend together, and you can’t separate one from another.

in the real world. Which, yes, often sex is an expression of love. Or desire. But many times, sex is divorced from both of those things: it can be used as a weapon (either literallyy or figuratively). It can be used transactionally, economically. Sometimes these uses blend together, and you can’t separate one from another.

Sex for love and desire happens often in my writing; my characters tend to be sexually and romantically agentic people. Yay for them! That’s why Ariah was classified as a romance, after all3. But here are some other ways sex has appeared in my fiction:

“ Matters of Scale” touches obliquely on the issue of sexual addiction. Both “Matters of Scale” and Ariah explore the intersection of sex and magic with regard to shapers, for whom sex is complicated—consent is tricky because they essentially black out4. Some shapers self-medicate with sex to escape the constant noise of their magical abilities, just like some real-life people use sex to keep anxiety or depression or other demons at bay.

Matters of Scale” touches obliquely on the issue of sexual addiction. Both “Matters of Scale” and Ariah explore the intersection of sex and magic with regard to shapers, for whom sex is complicated—consent is tricky because they essentially black out4. Some shapers self-medicate with sex to escape the constant noise of their magical abilities, just like some real-life people use sex to keep anxiety or depression or other demons at bay.

Cargo is one of the very few places I’ve written about sexual violence. It’s a topic I write about infrequently, not because it’s unimportant, but because it’s triggering and it’s often written about flippantly and inappropriately. But it does happen.

Cargo also introduced the Aerdh-pirate concept of tethers, or captain’s concubines.  My current work-in-progress, The Search, is exploring the nuance and nature of tetherdom in greater detail. This is sex as transaction, or at the very least implied sex as transaction, but it’s not coercive. The Search is going further, too: what would a brothel that is not coercive and exploitative look like? What would a sex worker-run brothel look like?

My current work-in-progress, The Search, is exploring the nuance and nature of tetherdom in greater detail. This is sex as transaction, or at the very least implied sex as transaction, but it’s not coercive. The Search is going further, too: what would a brothel that is not coercive and exploitative look like? What would a sex worker-run brothel look like?

All of these elements were as plot-driven and plot-driving as the romantic and lusty bits. All of these elements, I think, were also key to include from a worldbuilding perspective, as well. It’s false to think of sex one way. It has always been a flexible part of human nature, used and abused and traded in a hundred different ways. Hopefully one day we won’t abuse it anymore, but I think we’ll continue to trade it (hopefully ethically—because I think we can trade it ethically). At the very least, unless you’re writing in a utopia, your world needs to include all the permutations of how sex occurs.

1Wesley Chu

2Nick Cole

3Ariah was published by Love, Sex & Merlot, the Romance imprint of the Zharmae Publishing Press, not its fantasy imprint (Luthando Couer).

4I am coming to realize there is likely a whole separate post in this.